Abstract

Objective

To identify systematic reviews on interventions for glaucoma conditions and assess their reliability, thereby generating a list of potentially reliable reviews for updating the glaucoma practice guidelines.

Design

Cross sectional study

Participants

Systematic reviews of interventions for glaucoma conditions.

Methods

We used a database of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in vision research and eye care maintained by the Cochrane Eyes and Vision United State Satellite as a source of reviews. We examined all Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions for glaucoma conditions published before August 7th, 2019 and all non-Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions for glaucoma conditions published between January 1st, 2014 and August 7th, 2019.

Main Outcome Measures

We assessed eligible reviews for reliability, extracted characteristics, and summarized key findings from reviews classified as reliable.

Results

Of the 4,451 systematic reviews in eyes and vision identified, 129 met our eligibility criteria and were assessed for reliability. Of these, we classified 49 (38%) as reliable. We found open-angle glaucoma (22/49) to be the condition with the most reviews and medical management (17/49) and intraocular pressure (43/49) to be the most common interventions and outcomes studied. Most reviews found a high degree of uncertainty in the evidence, which hinder the possibility of making strong recommendations in guidelines. These reviews found high-certainty evidence about a few topics: reducing IOP helps prevent glaucoma and its progression; prostaglandin analogues are the most effective medical treatment for lowering IOP; laser trabeculoplasty is as effective as medical treatment as a first-line therapy in controlling IOP; the use of IOP lowering medications peri- or post-operatively to accompany laser (e.g., trabeculoplasty) reduces the risk of post-operative IOP spikes; conventional surgery (i.e., trabeculectomy) are more efficacious than medications in reducing IOP; antimetabolites and beta-radiation improve IOP control after trabeculectomy. There is weak evidence regarding the effectiveness of minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries.

Conclusions

The majority of systematic reviews evaluating interventions for glaucoma are of poor reliability. Even among those that may be considered reliable, there are important limitations in the value of information due to the uncertainty of the evidence as well as small and sometimes unimportant clinical differences between interventions.

Keywords: Systematic Reviews, Glaucoma, Evidence-Based Medicine, Guideline Development

PRECIS

We found 49 reliable systematic reviews for a variety of glaucoma conditions and interventions. Most reviews found a high degree of uncertainty in the evidence presented and the usefulness for forming recommendations for clinical practice.

The purposes of clinical practice guidelines are to support decision making, improve health outcomes, optimize resource utilization, and reduce clinical practice variation.1,2 Current recommendations for guideline development include a systematic process to identify relevant questions, synthesize the best available evidence in systematic reviews, ideally from high quality randomized controlled trials for effects of interventions, and provide clinically relevant recommendations.3–5

The process of developing evidence based guidelines is challenging.6–8 There may be a lack of primary studies to answer some questions or uncertainty in the evidence because the estimates are not precise, the primary study populations are not directly relevant to the target population, the risk of bias is high, there may be too much heterogeneity in the estimates, or there may be a potential for publication bias.9–11 Approaches have been developed to assessing the certainty of evidence and guiding the strength of recommendations when developing guidelines. GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) is one such approach that is widely accepted and utilized due to its transparent approach, although the complexity of the evidence and the experience of the reviewers can impact the resulting judgements of evidence.6,12,13 Furthermore, the applicability of research findings and proposal of recommendations can be challenging because of the inconsistency of outcomes studied and lack of consensus on the effect sizes that are clinically meaningful.14–18

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine in the United States (now called the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine) released standards for developing trustworthy clinical practice guidelines. The standards include a recommendation that guideline developers use evidence from high quality systematic reviews (defined in Box 1) to inform recommendations.19,20 Accordingly, since 2014, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) has partnered with the Cochrane Eyes and Vision United States Satellite (CEV@US) to obtain systematic reviews relevant to their updates of the Preferred Practice Patterns (PPPs) guidelines. Specifically, CEV@US identifies potentially reliable systematic reviews that can be used to inform guideline recommendations on the effectiveness of various interventions. The 2016 cataract, 2017 refractive error, 2018 cornea, and 2019 retina PPPs demonstrate the success of this partnership.21–24 In 2019, the alliance continued for the development of the upcoming 2020 glaucoma PPPs.25–27 Following the framework for collaboration between the AAO and CEV@US, the European Glaucoma Society (EGS) partnered with CEV@US in 2019 to collect evidence to inform EGS guideline development.

Box 1. Definition of systematic review.

| Systematic reviews are scientific investigations which seek to answer a specific research question through the collection and critical assessment of all evidence meeting pre-specified criteria.15 When conducting a systematic review, it is imperative that investigators use explicit and pre-specified methods to identify, select, appraise, and summarize all available evidence.15 A systematic review should synthesize evidence qualitatively and may also include a “meta-analysis”: the quantitative combination of results from independent studies. |

For both partnerships, we sought to (1) identify systematic reviews on interventions for glaucoma conditions and assess their reliability, (2) generate a list of potentially reliable systematic reviews which can be used for updating the glaucoma practice guidelines, and (3) summarize the body of evidence contained therein.

METHODS

Search for studies and eligibility criteria

CEV@US maintains a database of Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews and meta-analyses in vision research and eye care. The initial search for systematic reviews was conducted in 2007 and the search has been updated seven times since, most recently on August 7, 2019.20,28 The search is conducted in PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane library and utilizes a mixture of keywords and controlled vocabulary, designed by the information specialists at Welch Medical Library. The full search strategy can be found in Appendix 1. We defined a systematic review as a full-text report which either labeled itself as a systematic review or meta-analyses anywhere in the text; or met the definition of a systematic review or a meta-analysis, when these terms were not used, as defined by the Institute of Medicine.19 Systematic reviews are included in the database after two reviewers independently perform title/abstract and full-text screening, resolving any discrepancies through discussion.

Initially, two independent research assistants classified each included record by condition. In early 2019, EGS members verified and re-classified all database records by condition. When the database was updated in August 2019, all new records were screened and selected by CEV@US researchers and EGS members; and the conditions were classified by EGS members of the team (AAB, MM, GV).

For inclusion in this report, systematic reviews must have assessed one or more interventions for glaucoma conditions, including open angle glaucoma (OAG) (primary, including normal tension glaucoma; or secondary, such as pigmentary and pseudoexfoliative glaucoma), ocular hypertension, primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG), or any other types of glaucoma (e.g., refractory, non-refractory, neovascular, primary congenital, pseudoexfoliative, pigmentary). We included relevant glaucoma reviews that were published between January 1st, 2014 to August 7th, 2019 because prior experience with guideline creation indicates that older reviews are often not used, reviews that are new should include studies found in previous reviews, and systematic reviews published more than 5 years ago are unlikely to be up to date.29 Additionally, glaucoma reviews pre-2010 are covered in previous work by an author.30 We only considered reviews that were published before January 1st, 2014 if the review was a Cochrane review with no restriction on dates. For eligible systematic reviews with more than one publication, we included the most recent or complete version for this report.

Assessment of reliability of systematic reviews and data extraction

We used the Systematic Review Data Repository (SRDR) for data extraction and reliability assessment of included reviews. To assess reliability, we adapted a data extraction form used by our team in previous studies.20–24,30–33 We extracted the methods used for systematic reviews (which form the basis for assessing the potential reliability of these reviews), including specifying the eligibility criteria, the search strategy, the number of people involved in completing each step of the systematic review, whether the risk of bias in the included studies had been assessed, and, if performed, how meta-analysis was conducted. Data items on assessing the methodological rigor for systematic reviews came from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP),34 the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR),35 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).36

We classified a systematic review as potentially “reliable” if it met the following methodological criteria: (1) defined eligibility criteria for selection of individual studies, (2) conducted a comprehensive literature search for eligible studies, (3) assessed the risk of bias of the individual included studies using any method, (4) used appropriate methods for meta-analyses (criterion only assessed if meta-analysis was performed), and (5) we observed concordance between the review’s findings and conclusions. We considered a systematic review “unreliable” when one or more of these criteria were not met. Definitions of the reliability assessment criteria are given in Box 2. We acknowledged that these criteria are “minimal” in the sense a review considered potentially “reliable” could still have some methodological deficiencies. We performed further data extraction on each review that we classified as potentially reliable, including: the population, interventions compared, outcomes examined (“PICO”), the number of studies and participants (or eyes) included, and key findings. We assigned a primary intervention type to each review based on their included interventions and comparators. The identified reliable reviews and their characteristics were subsequently presented to the AAO and the EGS to help guide the development of their glaucoma PPP and guidelines. Our ensuing results regarding the evidence to support interventions for glaucoma are derived entirely from reliable reviews, not what may be found if one were to perform an original systematic review.

Box 2. Criteria for assessing the reliability of systematic reviews.

| Criterion | Definition applied to systematic review reports |

|---|---|

| Defined eligibility criteria | Described inclusion and/or exclusion criteria for eligible studies. |

| Conducted comprehensive literature search | Review authors (1) described an electronic search of two or more bibliographic databases; (2) used a search strategy comprising a mixture of controlled vocabulary and keywords; (3) reported using at least one other method of searching such as searching of conference abstracts; identified ongoing trials; complemented electronic searching by hand search methods (e.g., checking reference lists); and contacted included study authors or experts. |

| Assessed risk of bias of included studies | Used any method (e.g., scales, checklists, or domain-based evaluation) designed to assess methodological rigor of included studies. |

| Used appropriate methods for meta-analysis | Used quantitative methods that (1) were appropriate for the study design analyzed (e.g., maintained the randomized nature of trials; used adjusted estimates from observational studies); (2) correctly computed the weight for included studies. |

| Observed concordance between review findings and conclusions | Authors’ reported conclusions were consistent with findings, provided a balanced consideration of benefits and harms, and did not favor a specific intervention if there was lack of evidence. |

A single EGS or CEV member conducted the reliability assessment and data extraction, followed by a complete verification of the reliability assessment and subsequent extraction for all reliable reviews by a senior member of the team (AAB, TL, RQ, GV). The senior member made the decision regarding any identified discrepancies. We used this single extraction with verification approach as it has been demonstrated to be as accurate as double independent data abstraction.37

Our observations on the certainty of evidence for interventions are based upon the GRADE, Risk of Bias, or quality assessments within included systematic reviews. In general, “no evidence” means no RCTs – or whatever eligible study design was specified by the review(s) – have made the comparison, whereas “uncertainty” means there might be eligible studies, but the certainty in evidence has been downgraded due to one or more reasons including imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, high risk of bias, or publication bias.

This study is non-human subject research, comprising entirely secondary data from systematic reviews, and thus no institutional review board application was required and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki do not apply.

RESULTS

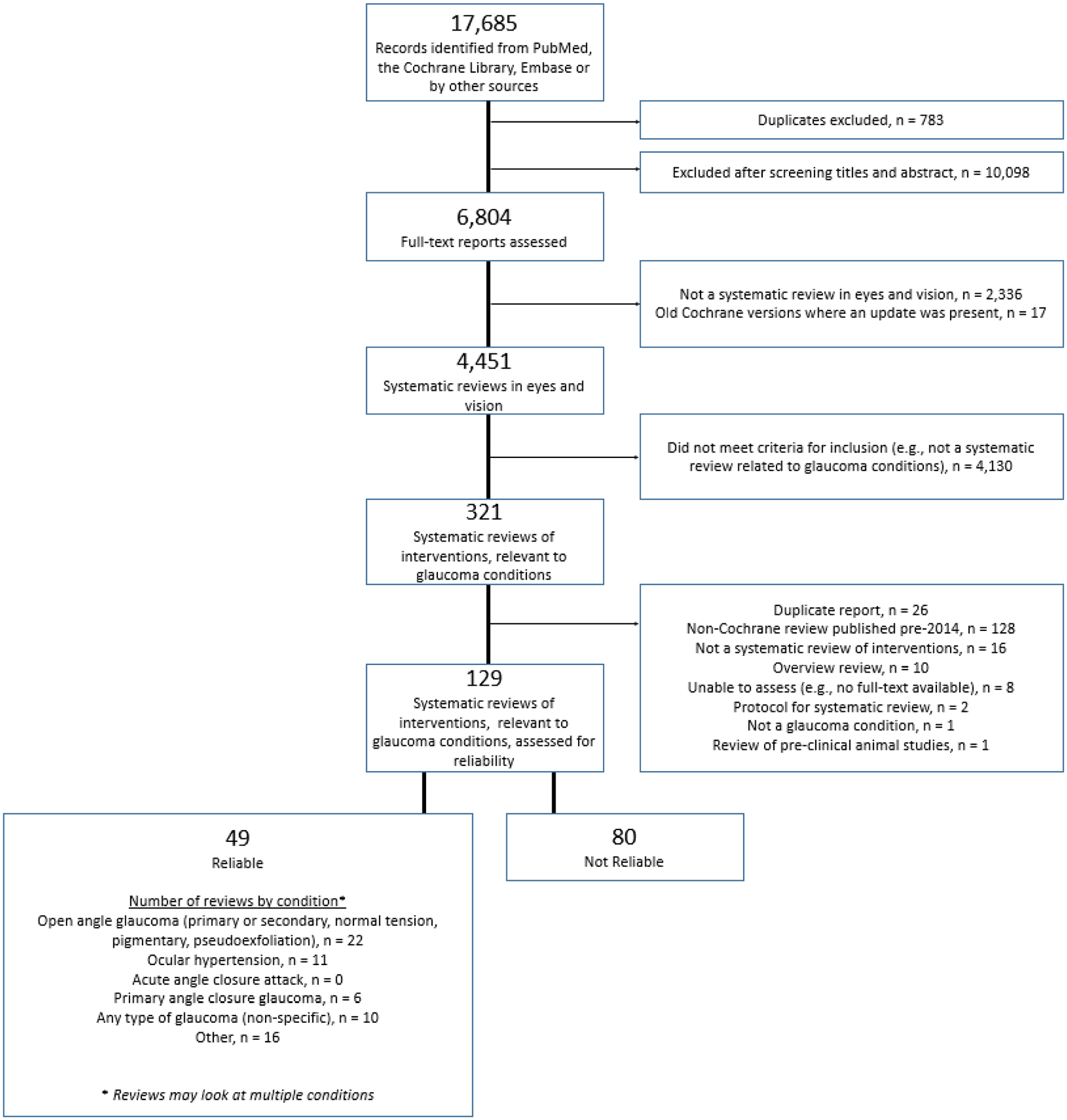

Of the 4,451 systematic reviews in eyes and vision that we identified as of August 2019, 321 examined the effectiveness and/or safety of an intervention relating to one or more glaucoma conditions (Figure). Of these 321, we excluded 192 due to various reasons, including being a non-Cochrane review published before January 1st, 2014 (n = 129) (Figure).

Figure.

Study flow chart

Study characteristics

We assessed the reliability of 129 systematic reviews. We classified 49/129 (38%) reports as “reliable” and 80/129 (62%) as “unreliable”. Appendix 2 contains a listing of the 80 unreliable reviews as well as their reasons for being considered unreliable. Four reviews did not identify any primary studies (i.e., empty reviews).

Reviews could examine multiple conditions, interventions, and outcomes. We found open angle glaucoma to be the condition with the most reviews (22/49), followed by ocular hypertension (11/49) and any type of glaucoma (10/49) (Table 1). We did not find any reviews that assessed interventions for acute angle closure attack. Most of the reviews focused on medical (17/49) interventions, followed by surgical (14/49) and laser (10/49) interventions (Table 1). We found intraocular pressure (IOP) (43/49) and safety (38/49) to be the two most commonly assessed outcomes. Visual field (19/49), treatment burden (18/49), treatment success/failure (17/49), and visual acuity (16/49) were the next most commonly assessed outcomes. Cost effectiveness (1/49), visual function (e.g., reading small print or driving) (2/49), and quality of life (6/49) were rarely assessed in reviews (Table 1).

Table 1.

Populations, interventions, and outcomes of 49 reliable glaucoma intervention reviews

| Review characteristic | Reviews n |

|---|---|

| Condition a | |

| Open angle glaucoma (primary or secondary, pigmentary, pseudoexfoliative, normal tension) | 22 |

| Ocular hypertension | 11 |

| Acute angle closure attack | 0 |

| Primary angle closure glaucoma | 6 |

| Any type of glaucoma | 10 |

| Otherb | 16 |

| Intervention type c | |

| Medical interventions | 17 |

| Laser interventions | 10 |

| Surgical interventions | 14 |

| Devices | 5 |

| Post operative (Surgical interventions) | 2 |

| Perioperative (Laser interventions) | 1 |

| Outcomes a | |

| Intraocular pressure (IOP) | 43 |

| Visual function (e.g., reading small print, driving) | 2 |

| Visual field | 19 |

| Visual acuity | 16 |

| Treatment success or treatment failure | 17 |

| Need for reoperation | 9 |

| Treatment burden (e.g., reduction in number of drops) | 18 |

| Morphologic measures (e.g., optic disc damage, nerve fiber layer loss) | 9 |

| Safety (e.g., adverse events) | 38 |

| Quality of life (general or vision-related) | 6 |

| Cost, or cost-effectiveness | 1 |

| Otherd | 10 |

Reviews could examine multiple conditions and outcomes

Examples of “Other” types of glaucoma: refractory, non-refractory, neovascular, primary congenital, pseudoexfoliative, pigmentary

Reviews were assigned a primary intervention type based on their designated interventions and comparators

Examples of “Other” outcomes: mean ocular perfusion pressure, pain control, electrophysiology, postoperative hypertensive phase, optic atrophy, adherence/persistence, patients’ knowledge of glaucoma, glaucoma/optic neuropathy progression, ocular problems (e.g., late hypotony, maculoathy, cataract, epitheliopathy, Tenon’s cyst, hyphaema, endophthalmitis)

Clinical findings of 49 reliable reviews

Table 2 presents the 49 included reviews and their characteristics including objective, participants, interventions and comparators, number of studies and participants included, main conclusions. This table is sorted by intervention type – medical interventions, surgical interventions, laser interventions, or devices – and in anti-chronological order (most recent publications first).

Table 2 – Characteristics of 49 reliable systematic reviews on interventions for glaucoma conditions -.

sorted by intervention type and in reverse chronological order of publication.

| Study ID [PMID] Title | Objective(s) | Participants | Intervention Comparisons | # of Studies; Participants (or eyes) [Study Types] | Conclusion(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Interventions | |||||

| Rennie 2019 [30880485] Topical medical therapy and ocular perfusion pressure in open angle glaucoma | “[To compare] the benefits and harms of topical interventions for ocular perfusion pressure in open angle glaucoma.” | Open angle glaucoma | Latanoprost; timolol; brimonidine; bimatoprost; dorzolamide; timogel; tafluprost; travaprost | 10; 416 [RCT, CCT] | “We identified low to moderate quality evidence describing post-intervention mean ocular perfusion pressure in open angle glaucoma. Bimatoprost increases mean ocular perfusion pressure when compared to timolol. As a class, prostaglandins increase mean ocular perfusion pressure. Prostaglandins may provide beneficial ocular perfusion pressure profiles compared to alternative agents.” |

| Loskutova 2018 [30296451] Nutritional supplementation in the treatment of glaucoma | “To determine whether nutritional interventions intended to prevent or delay the progression of glaucoma could prove to be a valuable addition to the mainstay of glaucoma therapy.” | Non-specific glaucoma | Nutritional supplementation; placebo | 21; 1935 [RCT, CCT, Cohort, Uncontrolled trial] | “Flavinoids [are suggested to] exert a beneficial effect in glaucoma, particularly in terms of improving ocular blood flow and potentially slowing progression of visual field loss. In addition, supplements containing forskolin have consistently demonstrated the capacity to reduce intraocular pressure beyond the levels achieved with traditional therapy alone; however, despite the strong theoretical rationale and initial clinical evidence for the beneficial effect of dietary supplementation as an adjunct therapy for glaucoma, the evidence is not conclusive.” “…the data from RCTs attempting to investigate the link between nutrition and glaucoma in humans are scarce, lacking in quality, and mostly inconclusive.” |

| Li 2018 [29144028] Efficacy and safety of different regimens for primary open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension | “To assess the efficacy and safety of different treatment regimes for glaucoma.” | Open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension | Latanoprost; timolol; brimonidine; brinzolamide; travoprost; dorzolamide; bimaprost; pilocarpine; tafluprost; betaxolol; cartelol; unoprostone; | 72; 19916 [RCT] | “Our network meta-analysis showed that prostaglandin analogues (PGAs) provide best intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering effect among all the monotherapy regimen.” |

| Huang 2018 [30142821] Safety of antivascular endothelial growth factor administration in the ocular anterior segment in pterygium and neovascular glaucoma treatment | “To compare anti-VEGF treatment in the ocular anterior segment in pterygium and neovascular glaucoma treatment with placebo/sham treatment for eye diseases.” | Neovascular glaucoma | Anti-VEGF; placebo | 18 (5 for glaucoma); 955 eyes (266 for glaucoma) [RCT] | “The administration of anti-VEGF agents in the ocular anterior segment for patients with pterygium and glaucoma was tolerable in tolerance and cornea, but was the risk factor of conjunctival disorders. The healing of corneal epithelium may be delayed in patients with primary corneal epithelial defects after anti-VEGF application.” “However, due to the limited evidence, further research should be performed on the safety of anti-VEGF administration in patients with different corneal disorders” |

| Diaconita 2018 [30363694] Washout duration of prostaglandin analogues | “To investigate the long term effects on intraocular pressure (IOP) after discontinuation of topical prostaglandin analogues (PGAs) primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) and ocular hypertension (OHT) patients.” | Open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension | Discontinuation of PGAs (latanoprost, unoprostone, travoprost, bimatoprost); continuing PGAs | 8; 307 [RCT, CCT, Case series/report] | “A significant IOP-lowering effect of latanoprost was not observed beyond 4 weeks, suggesting this may be an appropriate washout period for latanoprost. We could not identify appropriate washout periods for either travoprost or bimatoprost, although a majority of articles had 4-week washout durations for the two drugs.” |

| Xu 2017 [28218404] Topical medication instillation techniques for glaucoma | “To investigate the effectiveness of topical medication instillation techniques compared with usual care or another method of instillation of topical medication in the management of glaucoma or ocular hypertension.” | Primary angle closure glaucoma, secondary glaucoma | Topical medication instillation; other methods of instillation of topical medication; usual care | 2; 61 [RCT] | “Evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of topical medication instillation techniques for treatment of glaucoma is lacking. It is unclear what, if any, effects instillation techniques have on topical medical therapy for glaucoma.” |

| Sena 2017 [28122126] Neuroprotection for treatment of glaucoma in adults | “To systematically examine the evidence regarding the effectiveness of neuroprotective agents for slowing the progression of open-angle glaucoma in adults compared with no neuroprotective agent, placebo, or other glaucoma treatment.” | Open angle glaucoma | Brimonidine; timolol | 1; 190 [RCT] | “Although the only trial we included in this review found less visual field loss in the brimonidine-treated group, the evidence was of such low certainty that we can draw no conclusions from this finding. Further clinical research is needed to determine whether neuroprotective agents may be beneficial for individuals with OAG.” |

| Li 2016 [26526633] Comparative effectiveness of first-line medications for primary open angle glaucoma | “To assess the comparative effectiveness of first line medical treatments in patients with Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG) or ocular hypertension (OHT) through a systematic review and network meta-analysis, and to provide relative rankings of these treatments.” | Open angle glaucoma | Brimonidine; betaxolol; levobunolol; timolol; levobetaxolol; brinzolamide; dorzolamide; bimatoprost; unoprostone; latanoprost; travoprost; tafluprost; apraclonidine; carteolol; placebo | 114; 20275 [RCT] | “All active first-line drugs are effective compared to placebo in reducing intraocular pressure (IOP) at 3 months. Bimatoprost, latanoprost, and travoprost are among the most efficacious drugs, although the within class differences were small and may not be clinically meaningful. All factors, including adverse effects, patient preferences, and cost should be considered in selecting a drug for a given patient.” |

| Liu 2016 [27275435] Long-term assessment of prostaglandin analogs and timolol fixed combinations prostaglandin analogs monotherapy | “To draw a Meta-analysis over the comparison of the intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering efficacy and safety between the commonly used fixed-combinations of prostaglandin analogs and 0.5% timolol with prostaglandin analogs (PGAs) monotherapy.” | Open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension, primary angle closure glaucoma | Fixed combination latanoprost and timolol (morning); fixed combination latanoprost (morning); latanoprost (morning); bimatroprost (evening); fixed combination tafluprost and timolol (morning); tafluprost (morning) | 5; 1981 [RCT] | “The long-term efficacy of the fixed combination of PGAs/timolol therapy (FCs) overweighed the PGAs monotherapy in lowering IOP, but in the incidence of hyperemia and eye irritation syndromes, the differences are not statically significant. More RCTs with detailed and authentic data over the assessments of visual functions and morphology of optic nerve heads are hoped to be conducted.” |

| Whiting 2015 [26103030] Cannabinoids for medical use | “To conduct a systematic review of the benefits and adverse events (AEs) of cannabinoids.” | Ocular pressure glaucoma | Medical cannabinoids; placebo | 1; 6 [RCT] | “There was moderate-quality evidence to support the use of cannabinoids for the treatment of chronic pain and spasticity. There was low-quality evidence suggesting that cannabinoids were associated with improvements in nausea and vomiting due to chemotherapy, weight gain in HIV infection, sleep disorders, and Tourette syndrome. Cannabinoids were associated with an increased risk of short-term AEs.” |

| Xing 2014 [25349811] Fixed combination of latanoprost and timolol the individual components for primary open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension | “To assess the effects of the fixed combination of 0.005% latanoprost and 0.5% timolol (FCLT) their individual components for primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) and ocular hypertension (OHT).” | Open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension | Fixed combination (latanoprost and timolol); timolol; latanoprost; unfixed combination (latanoprost and timolol) | 14; 4135 [RCT, CCT] | “A better intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering effect has been demonstrated for FCLT compared to the monotherapy of components. The IOP lowering effect was worse for FCLT morning dose and almost same for FCLT evening dose compared to the unfixed combination of 0.005% latanoprost and 0.5% timolol (UFCLT). We need more long-term high quality RCTs to demonstrate the outcomes of visual field defect and optic atrophy.” |

| Lin 2014 [25184309] Comparative efficacy and tolerability of topical prostaglandin analogues for primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension | “To systematically review the efficacy and tolerability of 4 prostaglandin analogues (PGAs) as first-line monotherapies for intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering in adult patients with primary open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension.” | Open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension | Bimatoprost; latanoprost; tafluprost; travoprost | 32; 6565 [RCT] | “Bimatoprost achieved the highest efficacy in terms of IOP reduction, whereas latanoprost had the most favorable tolerability profile. This review serves to guide selection of the optimal PGA agent for individual patient care in clinical practice.” |

| Waterman 2013 [23633333] Interventions for improving adherence to ocular hypotensive therapy. | “To summarise the effects of interventions for improving adherence to ocular hypotensive therapy in people with ocular hypertension (OHT) or glaucoma.” | Ocular hypertension, non-specific glaucoma | Education; education with behavioural change; any intervention to improve adherence; brimonidine; dorzolamide; latanoprost; timolol; pilocarpine; usual care | 16; 1565 [RCT, CCT] | “Although complex interventions consisting of patient education combined with personalised behavioural change interventions, including tailoring daily routines to promote adherence to eye drops, may improve adherence to glaucoma medication, overall there is insufficient evidence to recommend a particular intervention.” |

| Simha 2013 [24089293] Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular glaucoma. | “To compare the intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering effects of intraocular anti-VEGF agents to no anti-VEGF treatment, as an adjunct to existing modalities for the treatment of Neovascular Glaucoma (NVG).” | Neovascular glaucoma | Anti-VEGF agents alone; anti-VEGF agents combined with any type of conventional therapy | 0; 0 [NA] | “Currently available evidence is insufficient to evaluate the effectiveness of anti-VEGF treatments, such as intravitreal ranibizumab or bevacizumab, as an adjunct to conventional treatment in lowering IOP in NVG.” |

| Law 2013 [23728656] Acupuncture for glaucoma. | “To assess the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture in people with glaucoma.” | Non-specific glaucoma | Acupuncture; sham acupuncture | 1; 33 [RCT, CCT] | “At this time, it is impossible to draw reliable conclusions from available data to support the use of acupuncture for the treatment of glaucoma. Because of ethical considerations, RCTs comparing acupuncture alone with standard glaucoma treatment or placebo are unlikely to be justified in countries where the standard of care has already been established. Because most glaucoma patients currently cared for by ophthalmologists do not use nontraditional therapy, clinical practice decisions will have to be based on physician judgments and patient preferences, given this lack of data in the literature.” |

| Burr 2012 [22972069] Medical versus surgical interventions for open angle glaucoma. | “To assess the effects of medication compared with initial surgery in adults with Open Angle Glaucoma (OAG).” | Open angle glaucoma | Medical treatment; trabeculectomy | 4; 888 [RCT, CCT] | “Primary surgery lowers intraocular pressure more than primary medication but is associated with more eye discomfort. One trial suggests that visual field restriction at five years is not significantly different whether initial treatment is medication or trabeculectomy. There is some evidence from two small trials in more severe OAG, that initial medication (pilocarpine, now rarely used as first line medication) is associated with more glaucoma progression than surgery. Beyond five years, there is no evidence of a difference in the need for cataract surgery according to initial treatment. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of contemporary medication (prostaglandin analogues, alpha2-agonists and topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors) compared with primary surgery is not known.” |

| Vass 2007 [17943780] Medical interventions for primary open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. | “To assess and compare the effectiveness of topical pharmacological treatment for Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG) or ocular hypertension (OHT) to prevent progression or onset of glaucomatous optic neuropathy.” | Primary open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension | Topical antiglaucomatous drugs (timolol, levobunolol, betaxolol, dorzolamide, carteolol, brimonidine, pilocarpine, epinephrine); unspecified topical antiglaucomatous drug; placebo; no treatment | 26; 4979 [RCT] | “The results of this review support the current practice of intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering treatment of OHT. A visual field protective effect has been clearly demonstrated for medical IOP lowering treatment. Positive but weak evidence for a beneficial effect of the class of beta-blockers has been shown. Direct comparisons of prostaglandins or brimonidine to placebo are not available and the comparison of dorzolamide to placebo failed to demonstrate a protective effect. However, absence of data or failure to prove effectiveness should not be interpreted as proof of absence of any effect. The decision to treat a patient or not, as well as the decision regarding the drug with which to start treatment, should remain individualised, taking in to account the amount of damage, the level of IOP, age and other patient characteristics.” |

| Surgical interventions | |||||

| Altmatlouh 2019 [30242968] Steroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the postoperative regime after trabeculectomy - which provides the better outcome? | “To compare the effectiveness of different formulations of steroids (topical, systemic and depot) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in achieving long-term pressure control with fewer antiglaucomatous medications, preserving visual acuity and visual fields while considering surgical and postoperative complications.” | Non-specific glaucoma patients undergoing trabeculectomy | Topical steroid; combined topical and oral steroid; combined topical and depot steroid; combined topical steroid and topical NSAID; topical NSAID; placebo | 7; 437 (mix of participants and eyes in studies) [RCT] | “There is a low level of evidence to support the clinician in deciding which postoperative regime provides a more favourable outcome because of inconsistency in the reported outcomes between studies and a low number of patients for each comparable intervention and outcome. It does seem that topical steroids are better than no anti-inflammatory treatment after glaucoma surgery, but further research is recommended.” |

| Chen 2018 [29533959] Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab combined with mitomycin C or 5-fluorouracil in primary trabeculectomy | “To evaluate the efficacy and safety of bevacizumab combined with antimetabolite as an adjunctive therapy in primary trabeculectomy for glaucoma.” | Non-specific glaucoma patients undergoing primary trabeculectomy, excluding pediatric glaucoma | Trabeculectomy with mitomycin C (MMC) + bevacizumab; trabeculectomy with 5-Flourouracil (FU)+ bevacizumab; trabeculectomy with MMC; trabeculectomy with 5-FU | 3; 141 [RCT] | “The systematic review demonstrated that the combination of bevacizumab (1.25 mg/mL) with a regular concentration of antimetabolite did not show more benefit or harm compared with using anti-metabolite alone.” |

| Cheng 2016 [26769010] Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for control of wound healing in glaucoma surgery | “To assess the effectiveness of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapies administered by subconjunctival injection for the outcome of trabeculectomy at 12 months follow-up and to examine the balance of benefit and harms when compared to any other anti-scarring agents or no additional anti-scarring agents.” | Non-specific glaucoma patients undergoing trabeculectomy | Trabeculectomy with subconjunctival anti-VEGF; trabeculectomy with anti-scarring agents; trabeculectomy with no additional anti-scarring agents | 5; 175 [RCT] | “The evidence is currently of low quality which is insufficient to refute or support anti-VEGF subconjunctival injection for control of wound healing in glaucoma surgery. The effect on intraocular pressure (IOP) control of anti-VEGF agents in glaucoma patients undergoing trabeculectomy is still uncertain, compared to mitomycin C (MMC).” |

| Zhang 2015 [26171900] Combined surgery versus cataract surgery alone for eyes with cataract and glaucoma | “To assess the relative effectiveness and safety of combined surgery versus cataract surgery (phacoemulsification) alone for co-existing cataract and glaucoma. The secondary objectives include cost analyses for different surgical techniques for co-existing cataract and glaucoma.” | Open angle glaucoma, pseudoexfoliative glaucoma, pigmentary glaucoma | Phacoemulsification; phacoemulsification and trabeculectomy; phacoemulsification and iStent; phacoemulsification and 2 iStents; phacoemulsification and trabecular aspiration; phacoemulsification and ab externo trabeculotomy | 9; 655 [RCT] | “There is low quality evidence that combined cataract and glaucoma surgery may result in better intraocular pressure (IOP) control at one year compared with cataract surgery alone. The evidence was uncertain in terms of complications from the surgeries. Furthermore, this Cochrane review has highlighted the lack of data regarding important measures of the patient experience, such as visual field tests, quality of life measurements, and economic outcomes after surgery, and long-term outcomes (five years or more). Additional high-quality RCTs measuring clinically meaningful and patient-important outcomes are required to provide evidence to support treatment recommendations.” |

| Wang 2015 [26625212] Device-modified trabeculectomy for glaucoma | “To assess the relative effectiveness, primarily with respect to intraocular pressure (IOP) control and safety, of the use of different devices as adjuncts to trabeculectomy compared with standard trabeculectomy in eyes with glaucoma.” | Non-specific glaucoma | Trabeculectomy + MMC; trabeculectomy + MMC + ExPRESS; trabeculectomy + express under sclera; trabeculectomy + ExPRESS under conjunctiva; trabeculectomy + ExPPRESS; trabeculectomy + Ologen implant; trabeculectomy + amniotic membrane; trabeculectomy + MMC + amniotic membrane; trabeculectomy + EPTFE; trabeculectomy + MMC + EPTFE; trabeculectomy + Gelfilm; trabeculectomy + MMC + Gelfilm | 33; 1542 [RCT] | “The use of devices with standard trabeculectomy may help with greater IOP reduction at one-year follow-up than trabeculectomy alone; however, due to potential biases and imprecision in effect estimates, the quality of evidence is low. When we examined outcomes within subgroups based on the type of device used, our findings suggested that the use of an Ex-PRESS device or an amniotic membrane as an adjunct to trabeculectomy may be slightly more effective in reducing IOP at one year after surgery compared with trabeculectomy alone. The evidence that these devices are as safe as trabeculectomy alone is unclear. Due to various limitations in the design and conduct of the included studies, the applicability of this evidence synthesis to other populations or settings is uncertain. Further research is needed to determine the effectiveness and safety of other devices and in subgroup populations, such as people with different types of glaucoma, of various races and ethnicity, and with different lens types (e.g. phakic, pseudophakic).” |

| Ghate 2015 [25636153] Surgical interventions for primary congenital glaucoma | “To compare the effectiveness and safety of different surgical techniques for primary congenital glaucoma.” | Primary congenital glaucoma | Trabeculotomy-trabeculectomy; trabeculectomy; viscocanalostomy; one goniotomy; two goniotomies; surgical goniotomy under general anesthesia; neodymium-YAG laser goniotomy under oral chloral hydrate sedation; combined trabeculectomy-trabeculotomy with MMC (CTTM); CTTM with deep sclerotomy | 6; 61 [RCT] | “No conclusions could be drawn from the trials included in this review due to paucity of data. More research is needed to determine which of the many surgeries performed for primary congenital glaucoma are effective.” |

| Cabourne 2015 [26545176] Mitomycin C versus 5-fluorouracil for wound healing in glaucoma surgery | “To assess the effects of mitomycin compared to 5-Fluorouracil as an antimetabolite adjunct in trabeculectomy surgery.” | Non-specific glaucoma | Trabeculectomy with intraoperative MMC; trabeculectomy with intraoperative 5-FU; trabeculectomy with postoperative 5-FU; trabeculectomy with intraoperative and postoperative 5-FU; trabeculectomy with intraoperative and postoperative MMC | 11; 679 [RCT] | “Low-quality evidence exists that mitomycin may be more effective in achieving long-term lower intraocular pressure than 5-Fluorouracil.” |

| Al-Haddad 2015 [26599668] Fornix-based versus limbal-based conjunctival trabeculectomy flaps for glaucoma | “To assess the comparative effectiveness of fornix-versus limbal-based conjunctival flaps in trabeculectomy for adult glaucoma, with a specific focus on intraocular pressure (IOP) control and complications (adverse effects).” | Non-specific glaucoma | Fornix-based trabeculectomy; limbal-based trabeculectomy | 6; 361 [RCT] | “The main result of this review was that there was uncertainty as to the difference between fornix- and limbal-based trabeculectomy surgeries due to the small number of events and confidence intervals that cross the null. This also applied to postoperative complications, but without any impact on long-term failure rate between the two surgical techniques.” |

| Thomas 2014 [25066789] Antimetabolites in cataract surgery to prevent failure of a previous trabeculectomy | “To assess the effects of antimetabolites with cataract surgery on functioning of a previous trabeculectomy.” | Non-specific glaucoma | Lens extraction with antimetabolites (5-FU or MMC); lens extraction with no antimetabolites | 0; 0 [NA] | “There are no RCTs of antimetabolites with cataract surgery in people with a functioning trabeculectomy. Appropriately powered RCTs are needed of antimetabolites during cataract surgery in patients with a functioning trabeculectomy.” |

| Green 2014 [24554410] 5-Fluorouracil for glaucoma surgery | “To assess the effects of both intraoperative application and postoperative injections of 5-Flouracil (FU) in eyes of people undergoing surgery for glaucoma at one year.” | Non-specific glaucoma | Glaucoma surgery with mitomycin C; glaucoma surgery with 5-Fluorouracil | 12; 1319 [RCT] | “We concluded that the main benefit is for people at high risk of problems. There may be a smaller benefit for people at low risk of problems if 5-FU is given either as injections after surgery or during the operation. However, 5-FU was found to increase the risk of serious complications and so may not be worthwhile for the small benefit gained.” “The small but statistically significant reduction in surgical failures and intraocular pressure at one year in the primary trabeculectomy group and high-risk group must be weighed against the increased risk of complications and patient preference.” |

| Eldaly 2014 [24532137] Non-penetrating filtration surgery versus trabeculectomy for open-angle glaucoma | “To compare the effectiveness of non-penetrating trabecular surgery compared with conventional trabeculectomy in people with glaucoma.” | Open angle glaucoma | Trabeculectomy; viscocanalostomy; deep sclerotomy | 5; 311 eyes [RCT, CCT] | “This review provides some limited evidence that control of intraocular pressure (IOP) is better with trabeculectomy than viscocanalostomy. For deep sclerectomy, we cannot draw any useful conclusions.” |

| Kirwan 2012 [22696336] Beta radiation for glaucoma surgery. | “To assess the effectiveness of beta radiation during glaucoma surgery (trabeculectomy).” | Non-specific glaucoma patients undergoing trabeculectomy | Trabeculectomy with beta radiation; trabeculectomy | 4; 551 [RCT] | “Trabeculectomy with beta irradiation has a lower risk of surgical failure compared to trabeculectomy alone.” |

| Waboso 2012 [22895936] Needling for encapsulated trabeculectomy filtering blebs. | “The objective of this review was to assess the effects of needling encapsulated blebs on intraocular pressure.” | People with encapsulated trabeculectomy blebs | Bleb needling; digital massage and non-specific betablockers, with or without systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitor | 1; 25 [RCT, CCT] | “Evidence from one small trial suggests that needling of encapsulated trabeculectomy blebs is not better than medical treatment in reducing intraocular pressure.” |

| Bochmann 2012 [22972097] Interventions for late trabeculectomy bleb leak. | “To assess the effects of interventions for late trabeculectomy bleb leak.” | Patients with a late-onset (i.e. more than three months after glaucoma surgery) bleb leak after trabeculectomy, patients with a history of blebitis or endophthalmitis in whom the infection has been controlled | Amniotic membrane transplant; conjunctival advancement; any intervention to close a bleb leak | 1; 30 [RCT, CCT] | “Although a variety of treatments have been proposed for bleb leaks, there is no evidence of their comparative effectiveness. The evidence in this review was provided by a single trial that compared two surgical procedures (conjunctival advancement and amniotic membrane transplant). The trial did show a superiority of conjunctival advancement, which was regarded as standard treatment, to amniotic membrane transplantation.” |

| Friedman 2006 [16856103] Lens extraction for chronic angle-closure glaucoma. | “To assess the effectiveness of lens extraction for chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma compared with other interventions for the condition in people without past history of acute-angle closure attacks.” | Primary angle closure glaucoma | Extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) with posterior chamber intraocular lens (PCIOL) implantation; limbal-based trabeculectomy; extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) with posterior chamber intraocular lens (PCIOL) implantation and additional goniosynechialysis | 2; 49 [RCT, CCT, Cohort] | “There is no evidence from good quality randomized trials or non-randomized studies of the effectiveness of lens extraction for chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma.” |

| Wilkans 2005 [16235305] Intra-operative mitomycin C for glaucoma surgery. | “To assess the effects of intraoperative mitomycin C (MMC) compared to placebo or no adjunct in trabeculectomy.” | Neovascular glaucoma; congenital glaucoma; glaucoma secondary to intraocular inflammation; people with previous glaucoma drainage surgery, previous surgery involving anything more than trivial conjunctival incision, undergoing trabeculectomy with extra-capsular cataract extraction and intraocular lens implant, or undergoing primary trabeculectomy | Trabeculectomy with intraoperative MMC; trabeculectomy with no antimetabolite; trabeculectomy with placebo | 11; 698 [RCT] | “Intraoperative MMC reduces the risk of surgical failure in eyes that have undergone no previous surgery and in eyes at high risk of failure. Compared to placebo it reduces mean intraocular pressure at 12 months in all groups of participants in this review. Apart from an increase in cataract formation following MMC, there was insufficient power to detect any increase in other serious side effects such as endophthalmitis.” |

| Laser interventions | |||||

| Toth 2019 [30801132] Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP) for open angle glaucoma and primary angle closure | “To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ECP in people with open angle glaucoma (OAG) and primary angle closure whose condition is inadequately controlled with drops.” | Open angle glaucoma, primary angle closure glaucoma | Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP) | 0; 0 [NA] | “There is currently no high-quality evidence for the effects of ECP for OAG and primary angle closure. Properly designed RCTs are needed to assess the medium and long-term efficacy and safety of this technique.” |

| Chen 2019 [30852841] Cyclodestructive procedures for refractory glaucoma | “To assess the relative effectiveness and safety of cyclodestructive procedures compared with other procedures in people with refractory glaucoma of any type and to assess the relative effectiveness and safety of individual cyclodestructive procedures compared with each other.” | Refractory glaucoma | Cyclodestructive procedures; aqueous shunts; any laser treatments | 5; 326 [RCT, CCT] | “Evidence from five studies included in this review was inconclusive as to whether cyclodestructive procedures for refractory glaucoma result in better outcomes and fewer complications than other glaucoma treatments, and whether one type of cyclodestructive procedure is better than another. The most commonly reported adverse events across all five studies were hypotony and phthisis bulbi.” |

| Michelessi 2018 [29694684] Cyclodestructive procedures for non-refractory glaucoma | “To assess the effectiveness and safety of cyclodestructive procedures for the management of non-refractory glaucoma (i.e., glaucoma in an eye that has not undergone incisional glaucoma surgery). We also aimed to compare the effect of different routes of administration, laser delivery instruments, and parameters of cyclophotocoagulation with respect to intraocular pressure (IOP) control, visual acuity, pain control, and adverse events.” | Non-refractory glaucoma (eye that has not undergone incisional glaucoma surgery) | High energy cyclophotocoagulation (CPC); low energy CPC | 1; 92 [RCT] | “There is insufficient evidence to evaluate the relative effectiveness and safety of cyclodestructive procedures for the primary procedural management of non-refractory glaucoma. Results from the one included trial did not compare cyclophotocoagulation to other procedural interventions and yielded uncertainty about any different in outcomes when comparing low-energy versus high-energy diode transscleral cyclophotocoagulation (TSCPC). Overall, the effect of laser treatment on IOP control was modest and the number of eyes experiencing vision loss was limited. More research is needed specific to the management of non-refractory glaucoma.” |

| Le 2018 [29897635] Iridotomy to slow progression of visual field loss in angle closure glaucoma | “To assess the effects of iridotomy compared with no iridotomy for primary angle-closure glaucoma, primary angle closure, and primary angle-closure suspects.” | Primary angle closure glaucoma | Laser peripheral iridotomy; no laser peripheral iridotomy | 2; 1251 [RCT, CCT] | “The available studies that directly compared iridotomy to no iridotomy have not yet published full trial reports. At present, we cannot draw reliable conclusions based on randomized controlled trials as to whether iridotomy slows progression of visual field loss at one year compared to no iridotomy. Full publication of the results from the studies may clarify the benefits of iridotomy.” |

| Zhang 2017 [28231380] Perioperative medications for preventing temporarily increased intraocular pressure after laser trabeculoplasty | “To assess the effectiveness of medications administered perioperatively to prevent temporarily increased intraocular pressure (IOP) after laser trabeculoplasty (LTP) in people with open-angle glaucoma (OAG).” | Open angle glaucoma | Brimonidine; apraclonidine; acetazolamide; pilocarpine; latanoprost; apraclonidine or brimonidine given before laser trabeculoplasty; apraclonidine or brimonidine given after laser trabeculoplasty; placebo | 22; 2112 [RCT] | “Perioperative medications are superior to no medication or placebo to prevent IOP spikes during the first two hours and up to 24 hours after LTP, but some medications can cause temporary conjunctival blanching, a short-term cosmetic effect. Overall, perioperative treatment was well tolerated and safe. Alpha-2 agonists are useful in helping to prevent IOP increases after LTP, but it is unclear whether one medication in this class of drugs is better than another. There was no notable difference between apraclonidine and pilocarpine in the outcomes we were able to assess.” |

| Michelessi 2016 [26871761] Peripheral iridotomy for pigmentary glaucoma | “To assess the effects of peripheral laser iridotomy compared with other interventions, including medication, trabeculoplasty, and trabeculectomy, or no treatment, for pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma.” | Open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension | Iridotomy with laser; combination antihypertensive medication; placebo | 5; 210 [RCT] | “We found insufficient evidence of high quality on the effectiveness of peripheral iridotomy for pigmentary glaucoma or pigment dispersion syndrome. Although adverse events associated with peripheral iridotomy may be minimal, the long-term effects on visual function and other patient-important outcomes have not been established. Future research on this topic should focus on outcomes that are important to patients and the optimal timing of treatment in the disease process (eg, pigment dispersion syndrome with normal IOP, pigment dispersion syndrome with established ocular hypertension, pigmentary glaucoma).” |

| Li 2015 [26286384] Meta-analysis of selective laser trabeculoplasty versus topical medication in the treatment of open-angle glaucoma | “[To perform] meta-analysis of selective laser trabeculoplasty versus topical medication in the treatment of open-angle glaucoma.” | Open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension | Selective laser trabeculoplasty; medical treatment | 5; 366 [RCT, CCT] | “Both selective laser trabeculoplasty and topical medication demonstrate similar success rates and effectiveness in lowering intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma.” |

| Wong 2015 [25113610] Systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of selective laser trabeculoplasty in open-angle glaucoma | “[To] summarize available evidence for considering selective laser trabeculoplasty as an alternative treatment in open-angle glaucoma through systematic review and meta-analysis.” | Open angle glaucoma | Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT); argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) | 10; NR [RCT] | “Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials shows that selective laser trabeculoplasty is non-inferior to argon laser trabeculoplasty and medication in intraocular pressure reduction and also in achieving treatment success. Number of medications reduction is similar between selective laser trabeculoplasty and argon laser trabeculoplasty. More robust evidence is needed to determine its efficacy as a repeated procedure.” |

| McAlinden 2014 [24310236] Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) vs other treatment modalities for glaucoma | “To compare selective laser trabeculoplasty to other glaucoma treatment options in terms of their intraocular pressure lowering effect.” | Non-specific glaucoma | 90º selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT); 180º SLT; 360º SLT; 90º argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT); 180º ALT; 360º ALT; excimer laser trabeculotomy (ELT); medical therapy | 17; NR [RCT] | “In terms of the intraocular pressure lowering effect, there is no difference between selective laser trabeculoplasty and argon laser trabeculoplasty.” |

| Ng 2012 [22336823] Laser peripheral iridoplasty for angle-closure. | “To assess the effectiveness of laser peripheral iridoplasty in the treatment of narrow angles (i.e. primary angle-closure suspect), primary angle-closure (PAC) or primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) in non-acute situations when compared with any other intervention.” | Primary angle closure glaucoma, narrow angles (primary angle-closure suspect), primary angle-closure | Laser peripheral iridotomy with adjunctive laser peripheral iridoplasty; laser peripheral iridotomy alone; laser peripheral iridoplasty; any intervention to treat angle closure | 1; 158 [RCT] | “There is currently no strong evidence for laser peripheral iridoplasty’s use in treating angle-closure.” |

| Rolim 2007 [17943806] Laser trabeculoplasty for open angle glaucoma. | “To study the effects of laser trabeculoplasty for Open Angle Glaucoma (OAG).” | Open angle glaucoma | Laser trabeculoplasty and topical beta-blocker; laser trabeculoplasty (diode laser, Nd:Yag laser); argon laser trabeculoplasty (argon laser at different power levels, argon laser at 0.1 seconds, argon laser at 0.2 seconds); trabeculoplasty (monochrome wavelength, bichromatic wavelength, two stage, one stage, superior, inferior); medication in newly diagnosed patients; medication in participants on maximal medical therapy | 19; 2137 [RCT] | “Evidence suggests that, in people with newly diagnosed OAG, the risk of uncontrolled intraocular pressure (IOP) is higher in people treated with medication used before the 1990s when compared to laser trabeculoplasty at two years follow up. Trabeculoplasty is less effective than trabeculectomy in controlling IOP at six months and two years follow up. Different laser technology and protocol modalities were compared to the traditional laser trabeculoplasty and more evidence is necessary to determine if they are equivalent or not.” |

| Devices | |||||

| Le 2019 [30919929] Ab interno trabecular bypass surgery with iStent for open angle glaucoma | “To assess the effectiveness and safety of ab interno trabecular bypass surgery with iStent (or iStent inject) for open-angle glaucoma in comparison to conventional medical, laser, or surgical treatment.” | Open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension | Lens extraction with iStent; lens extraction alone; iStent; medical therapy | 7; 764 [RCT] | “To assess the effectiveness and safety of ab interno trabecular bypass surgery with iStent (or iStent inject) for open-angle glaucoma in comparison to conventional medical, laser, or surgical treatment.” “There is very low-quality evidence that treatment with iStent may result in higher proportions of participants who are drop-free or achieving better IOP control, in the short, medium, or long-term.” |

| Foo 2019 [30999387] Aqueous shunts with mitomycin C versus aqueous shunts alone for glaucoma | “To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of mitomycin C (MMC) versus no MMC used during aqueous shunt surgery for reducing intraocular pressure (IOP) in primary and secondary glaucoma.” | Non-specific glaucoma patients undergoing surgery | Aqueous shunt with mitomycin C; aqueous shunt alone | 5; 333 eyes [RCT] | “We found insufficient evidence in this review to suggest MMC provides any postoperative benefit for glaucoma patients who undergo aqueous shunt surgery.” |

| King 2018 [30554418] Subconjunctival draining minimally-invasive glaucoma devices for medically uncontrolled glaucoma | “To evaluate the efficacy and safety of subconjunctival draining minimally-invasive glaucoma devices in treating people with open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension whose condition is inadequately controlled with drops.” | Open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension | Xen gelatin ab interno implant; InnFocus Microshunt ab externo implant | 0; 0 [NA] | “There is currently no high-quality evidence for the effects of subconjunctival draining minimally-invasive glaucoma devices for medically uncontrolled open angle glaucoma. Properly designed RCTs are needed to assess the medium- and long-term efficacy and safety of this technique.” |

| Tseng 2017 [28750481] Aqueous shunts for glaucoma | “To assess the effectiveness and safety of aqueous shunts for reducing intraocular pressure (IOP) in glaucoma compared with standard surgery, another type of aqueous shunt, or modification to the aqueous shunt procedure.” | Non-specific glaucoma | Aqueous shunts with modification; aqueous shunts without modification; trabeculectomy | 27; 2099 [RCT] | “Information was insufficient to conclude whether there are differences between aqueous shunts and trabeculectomy for glaucoma treatment. While the Baerveldt implant may lower IOP more than the Ahmed implant, the evidence was of moderate-certainty and it is unclear whether the difference in IOP reduction is clinically significant. Overall, methodology and data quality among existing randomized controlled trials of aqueous shunts was heterogeneous across studies, and there are no well-justified or widely accepted generalizations about the superiority of one surgical procedure or device over another.” |

| Chow 2017 [28740733] A systematic review and meta-analysis of the trabectome as a solo procedure in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma | “To examine the availability of evidence for one of the earliest available minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) procedures, the Trabectome.” | Open angle glaucoma | Trabectome; combination anti-hypotensive medication | 4; NR [Cohort] | “Although, the Trabectome as a solo procedure appears to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) and reduces the number of glaucoma medications, more high-quality studies are required to make definitive conclusions.” |

We determined 17 reviews of medical interventions for glaucoma to be reliable. There is high-certainty evidence from the trials included in these reviews that lowering IOP decreases conversion from ocular hypertension to glaucoma and also reduces disease progression in people with glaucoma. With regard to topical treatments, prostaglandin analogues (PGAs) are the most effective initial treatment for reducing IOP among patients with OAG and PACG. However, it is unclear if the differences between PGAs and other options are clinically important. Further, there are no data in our systematic reviews about the comparative effectiveness of PGAs and other treatment options on patient-centered outcomes, such as disease progression or quality of life. In terms of tolerance, PGAs lead to more problems with hyperaemia than any other monotherapy regimen but have a safe systemic profile. Evidence shows that combining PGAs with drugs of other classes (e.g., 0.5% timolol) can lead to better IOP decrease.

There is no evidence from systematic reviews to support neuroprotection, nutritional supplementation, or alternative therapies for managing glaucoma. Additionally, there is uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of behavioural and educational interventions to improve adherence to glaucoma medication.

For surgical and post-operative interventions for glaucoma, we identified 16 reliable reviews. Most of the reviews investigated trabeculectomy in patients with OAG. Surgical (i.e., trabeculectomy) interventions are more effective than medications in reducing IOP. Anti-fibrotic agents, such as mitomycin-C and 5-Fluorouracil, and beta-irradiation improve control of IOP, but it is unclear if any of these agents is superior to the others or if their use increases the risk of uncommon severe complications after trabeculectomy. There is no evidence to support many other modifications to the trabeculectomy technique over another, including the use of a non-penetrating technique or viscocanalostomy, the use of devices (ExPRESS shunt, ologen implants, amniotic membrane), the use of intraoperative or post-operative anti-vascular endothelial growth factor, different types of conjunctival flaps, or the use of releasable sutures. Additionally, topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatories after trabeculectomy are no better than topical steroids for post-operative IOP control. There is uncertainty regarding the comparative effectiveness and safety of combined glaucoma and cataract surgery in people with cataract and glaucoma. Similarly, the effectiveness and safety of surgical interventions for congenital glaucoma is uncertain. There is no evidence regarding interventions to manage encapsulated blebs or late bleb leaks.

Of the reviews of laser and perioperative interventions for glaucoma, we assessed 11 as reliable. Laser trabeculoplasty is as effective as medical treatment as a first-line therapy in controlling IOP in open-angle glaucoma. Of these methods, selective and argon laser trabeculoplasty have similar IOP lowering efficacy. Perioperative medications reduce the risk of early IOP spikes after laser trabeculoplasty, but it is uncertain which of the available medications are most effective. There is no evidence to support laser peripheral iridotomy for pigmentary glaucoma. There is also uncertainty about the comparative effectiveness of different laser interventions for prevention or treatment of PACG. With regard to cyclodestructive procedures, including external and endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation, their comparative effectiveness and safety is also uncertain.

We identified five reliable reviews of surgical devices for glaucoma. Overall, there is uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) devices for glaucoma, including when used in combination with cataract surgery compared with cataract surgery alone. There is also uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of glaucoma drainage devices or aqueous shunts compared with trabeculectomy. There is some weak evidence that that Baerveldt shunts may lower IOP more than Ahmed shunts, however the difference may not be clinically important. It is also uncertain whether the concurrent use of mitomycin-C improves surgical outcomes of aqueous shunts.

DISCUSSION

In a report to the National Leadership Commission on Health Care in the late 1980s, Eddy and Billings concluded that no high-level evidence existed demonstrating the effectiveness of treatment for glaucoma.38 Although generally dismissed by practitioners, this report prompted the glaucoma community to launch several landmark randomized controlled trials that confirmed the benefit of IOP reduction in patients with glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Subsequent trials investigated the safety and efficacy of various therapeutic approaches for lowering IOP including new medical treatments, surgical techniques, and devices. Both ophthalmologists and patients expect clinical practice guidelines to be based on best available evidence gathered through evidence synthesis. Overall, there is high-certainty evidence supporting the current practice of reducing IOP as it reduces the risk of glaucoma in people with ocular hypertension and also the risk of disease progression in people with established glaucoma. However, we found evidence directly comparing the effectiveness of different treatments was limited.

We found a large number of unreliable systematic reviews of interventions for glaucoma and its conditions and only 38% reviews were considered reliable. Nearly all these reliable reviews covered important aspects of treatment and maintenance of glaucoma through medical management, surgical and postoperative procedures, laser and perioperative interventions, and devices. When the certainty of evidence was rated or discussed, most of the reviews found a high degree of uncertainty in the data that they presented. Consequently, based on systematic reviews, we have high certainty about only a few topics: PGAs alone or in combination with other medications are the most effective medical treatment for lowering IOP, although ocular redness is a common side effect; laser trabeculoplasty is as effective as medical treatment as a first-line therapy to control IOP; the benefits of using medications peri- or post-operatively to accompany laser interventions; trabeculectomy is more effective than medications to lower IOP; use of antimetabolites or beta-irradiation improves IOP control after trabeculectomy. We found that the largest number of reviews concern medical treatment, and this is commensurate with the fact that medical management of glaucoma is also the area that has the greatest number of trials. Recent systematic reviews evaluating novel surgical interventions such as MIGS did not find strong evidence regarding their effectiveness; however, the recency of MIGS approvals and applications, as well as many yet in the approval process, limits substantially the conclusiveness of systematic reviews regarding MIGS efficacy and safety.

Despite having a selection of systematic reviews that we considered to be reliably conducted, we encountered challenges in the use of these data to inform clinical guidelines. This was mainly due to lack of primary research or low certainty evidence from or randomized trials or non-randomized studies with high risk of bias. Publication bias among primary studies is another threat to the systematic reviews we identified, which in turn may have an effect on our own conclusions in presenting the available evidence. As such, reliability of reviews defined by our five criteria should not be confused with an assessment of certainty of the body of evidence; and as a matter of fact, many reliable reviews concluded that the evidence is uncertain. Systematic reviews are not infallible and we have explored the reasons for unreliable reviews and ways in which reviews could be improved – both at the review level and that of the journal and the publishing process – in previous works.21–24

Similarly, we often found that the conclusions made in the systematic reviews were not presented in a workable form that can be used to draw up clinical guidelines (e.g., no GRADE Summary of Findings Tables). Often no attempt was made to indicate whether differences in efficacy data or side effects were clinically important.

Another obstacle is that systematic reviews take time to conduct and thus results may be out of date shortly after being completed, especially in fast-moving fields where new interventions are approved in quick succession and old standards may fall out of practice. For example, the LIGHT trial, EAGLE trial, and ZAP trial were not yet included in any of the systematic reviews we examined.39–41 The longer it has been since publication, the more likely a systematic review is missing new important evidence or even asking an outdated question.

One further challenge that affects the applicability of evidence to guidelines is inconsistency in the outcomes studied. When primary studies assess different outcomes, it becomes challenging to synthesize these in systematic reviews. For example, the reliable systematic review on various first line medications for OAG could not meta-analyze any visual field data because they were either not reported, not measured comparably, or reported in a manner that disallowed meta-analysis.42 The development and use of core outcome sets is one way to mitigate this challenge because a standardized set of outcomes for primary studies in a given condition, and subsequent reviews of interventions for the condition, would allow evidence to be directly comparable between studies, improve the value of review articles, and permit guideline developers to draw stronger conclusions regarding the potential effects of interventions.43,44 Examples of core outcome sets for glaucoma have already been developed.43,44

Our study has both strengths and limitations. The greatest strength is the use of a well-defined protocol, which has been refined through multiple iterations and led to successful previous partnerships between the AAO and CEV@US. Limitations of the study arise primarily from the characteristics of the included reviews. Our classification of reliability focused solely on five criteria applied to the systematic review report. We did not further assess the strength of the evidence where it was not already assessed in the reviews. Interpretation and drawing conclusions from uncertain evidence is complex and subjective, and thus we would recommend extreme caution when interpreting the quoted “conclusions” of the included reviews. Finally, even with our decision to include only reviews published within the last five years, it is possible that a reliable systematic review may not be updated, especially in rapidly evolving fields.

CONCLUSION

Many systematic reviews compared a range of interventions for glaucoma conditions, however we found that most are unreliable with regard to the methods used. Even among those which may be considered reliable, there are issues with the certainty in the evidence presented and the usefulness of evidence for forming recommendations in clinical practice guideline. Our findings demonstrate the need for improved quality and cohesion in future research, both primary and secondary, on interventions for glaucoma conditions.

Supplementary Material

Additional contributions/Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to Lori Rosman and Claire Twose for conducting our search. We are also grateful to Carlo Traverso, Anja Tuulonen, Cedric Schweitzer, Luis Pinto, Francesco Oddone, Andrew Tatham, Panayiota Founti, and other EGS members on the study team for their help in classifying conditions in the CEV database.

Funding statement and role of sponsor:

This project was supported by the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health (UG1EY020522, PI: Tianjing Li). The contribution of the IRCCS Fondazione G.B. Bietti in this paper was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health and by Fondazione Roma. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations:

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- AAO

American Academy of Ophthalmology

- CEV@US

Cochrane Eyes and Vision United States Satellite

- EGS

European Glaucoma Society

- OAG

Open Angle Glaucoma

- PACG

Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma

- SRDR

Systematic Review Data Repository

- CASP

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

- AMSTAR

Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PICO

Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome

- IOP

Intraocular Pressure

- PGA

Prostaglandin Analogue

- MIGS

Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest disclosures: No conflicting relationship exists for any author

Access to data: The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributor Information

Riaz Qureshi, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA.

Augusto Azuara-Blanco, Centre for Public Health, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Manuele Michelessi, IRCCS - Fondazione Bietti, Rome, Italy.

Gianni Virgili, Department of Neurosciences, Psychology Drug Research and Child Health (NEUROFARBA), University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

Joao Barbosa Breda, Cardiovascular R&D Center, Faculty of Medicine of the University of Porto, Porto, Portugal, KULeuven, Research Group Ophthalmology, Department of Neurosciences, Leuven, Belgium.

Carlo Alberto Cutolo, University of Genoa and IRCCS San Martino Policlinic Hospital, Genova, Italy.

Marta Pazos, Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Clínic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Andreas Katsanos, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece.

Gerhard Garhofer, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Miriam Kolko, Department of Ophthalmology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet-Glostrup, Glostrup, Denmark, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Verena Prokosch, Department of Ophthalmology, Mainz University, Mainz, Germany.

Ali Ahmed Al Rajhi, American Academy of Ophthalmology, San Francisco, USA.

Flora Lum, American Academy of Ophthalmology, San Francisco, USA.

David Musch, Departments of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences & Epidemiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA.

Steven Gedde, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, USA.

Tianjing Li, Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver, Aurora, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Audet AM, Greenfield S & Field M Medical practice guidelines: Current activities and future directions. Ann. Intern. Med 113, 709–714 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearson SD, Goulart-Fisher D & Lee TH Critical pathways as a strategy for improving care: Problems and potential. Ann. Intern. Med 123, 941–948 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook DJ, Greengold NL, Ellrodt AG & Weingarten SR The relation between systematic reviews and practice guidelines. Ann. Intern. Med 127, 210–216 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Field MJ & Lohr KN Clinical practice guidelines: Directions for a new program National Academy Press; (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handley MR, Stuart ME & Kirz HL An evidence-based approach to evaluating and improving clinical practice: implementing practice guidelines. HMO Pract 8, 75–83 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 328, 1490 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyatt GH et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336, 924–926 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guyatt GH et al. GRADE: What is ‘Quality of evidence’ and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ 336, 995–998 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsyth SR, Odierna DH, Krauth D & Bero LA Conflicts of interest and critiques of the use of systematic reviews in policymaking: An analysis of opinion articles. Syst. Rev 3, 122 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavis JN How can we support the use of systematic reviews in policymaking? PLoS Med 6, e1000141. (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenzer J, Hoffman J, Furberg C & Ioannidis JP Ensuring the integrity of clinical practice guidelines: A tool for protecting patients. BMJ 347, f5535 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]