Abstract

Motor recovery after severe spinal cord injury (SCI) is limited due to the disruption of direct descending commands. Despite the absence of brain-derived descending inputs, sensory afferents below injury sites remain intact. Among them, proprioception acts as an important sensory source to modulate local spinal circuits and determine motor outputs. Yet, it remains unclear whether enhancing proprioceptive inputs promotes motor recovery after severe SCI. Here, we first established a viral system to selectively target lumbar proprioceptive neurons and then introduced the excitatory Gq-coupled Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADD) virus into proprioceptors to achieve specific activation of lumbar proprioceptive neurons upon CNO administration. We demonstrated that chronic activation of lumbar proprioceptive neurons promoted the recovery of hindlimb stepping ability in a bilateral hemisection SCI mouse model. We further revealed that chemogenetic proprioceptive stimulation led to coordinated activation of proprioception-receptive spinal interneurons and facilitated transmission of supraspinal commands to lumbar motor neurons, without affecting the regrowth of proprioceptive afferents or brain-derived descending axons. Moreover, application of 4-aminopyridine-3-methanol (4-AP-MeOH) that enhances nerve conductance further improved the transmission of supraspinal inputs and motor recovery in proprioception-stimulated mice. Our study demonstrates that proprioception-based combinatorial modality may be a promising strategy to restore the motor function after severe SCI.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, AAV/PHP.S virus, proprioception, chemogenetic stimulation, spinal circuitry, motor recovery

Graphical abstract

Gao et al. show that chemogenetics-based proprioceptive stimulation promotes motor recovery in a mouse model of severe SCI by activating proprioception-receptive interneurons and facilitating supraspinal transmission to lumbar motor neuron pools, demonstrating a promising strategy to restore motor function after severe SCI.

Introduction

Severe spinal cord injury (SCI) has a destructive impact on motor control due to the deprivation of brain-derived descending commands below injury sites. Clinically, most SCI patients exhibiting complete lower limb paralysis are incompletely injured anatomically.1,2 In these patients, although direct descending inputs from brain are interrupted, intraspinal networks are largely spared. These spared intraspinal circuits may thus act as relay pathways to transmit supraspinal commands to lumbar motor neuron pools.3 However, the failure of motor control in these patients indicates that such spared relay pathways are functionally dormant. Indeed, a recent study demonstrated that dysfunctional local spinal circuits are responsible for the dormancy of relay pathways.4 Therefore, modulation of these circuits may re-activate the relay pathways, facilitate the supraspinal input transmission, and, thus, restore the motor function after severe SCI.

In intact animals, motor output is determined by the integration of supraspinal commands and sensory inputs.5 In animals with severe SCI, despite the interruption of brain-derived descending inputs, the primary sensory afferents below the injury site remain intact and act as the main source of excitation to modulate local spinal circuits and affect motor output.6,7 Studies have shown that elimination of sensory inputs substantially impaired gait control and motor recovery in mice with SCI.8,9 Moreover, numerous clinical studies documented that rehabilitation strategies, such as treadmill training and electrical epidural stimulation, can promote locomotor recovery, likely by enhancing dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sensory feedback.6,10,11 Together, these studies suggest that sensory feedback plays a vital role in gait control and motor recovery after SCI, and manipulating sensory inputs may be a practical strategy to restore the motor function after severe SCI.

Among the diverse DRG sensory neurons that transmit tactile, nociceptive, and proprioceptive stimuli, proprioceptors, which transmit the stretch stimuli from a muscle spindle and/or Golgi tendon organ, have the most extensive projection pattern to the spinal cord.5,12 Different from tactile and nociceptive inputs, Ia proprioceptive afferents directly form synapses with motor neurons, whereas Ib and II afferents project to the intermediate part of spinal laminae V–VI and establish polysynaptic connections with motor neurons.13 With both monosynaptic and polysynaptic contacts with motor neurons, proprioceptive feedback plays an important role in sensorimotor control.5,13,14 Studies demonstrated that mice being genetically deprived of proprioception displayed a degraded locomotor pattern and failed to maintain coordinated stepping.7,15 Moreover, ablation of proprioceptive feedback circuits substantially compromised the spontaneous functional recovery after incomplete SCI, suggesting that proprioception is closely linked to motor control and its presence might be engaged in functional recovery after SCI.7,16 Notably, proprioceptive inputs are usually unaffected after severe SCI. Yet, whether and how enhanced proprioceptive inputs promote motor recovery remains to be elucidated.

Proprioceptive sensory neurons express parvalbumin (PV), a calcium-binding protein12 that is also widely expressed in various subsets of interneurons in the central nerve system (CNS).17 For studying proprioceptive neurons, selective targeting of PV+ proprioceptors in DRG has been a challenge. In the current study, we first optimized the delivery method for a newly developed AAV/PHP.S viral vector18 to achieve preferential labeling of lumbar DRGs. We then efficiently introduced AAV/PHP.S virus expressing hM3Dq,19 an excitatory Gq-coupled DREADD (Gq-Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) receptor, into the lumbar PV+ proprioceptors using a Cre-mediated strategy. With viral and chemogenetic tools, we successfully achieved highly specific activation of proprioceptive inputs in mice. We found that chronic activation of the proprioceptive pathway promotes motor recovery in a mouse model of severe SCI, by activating proprioception-receptive interneurons and facilitating supraspinal transmission to lumbar motor neuron pools. In addition, we found that the combined application of 4-aminopyridine-3-methanol (4-AP-MeOH), a voltage-gated potassium channel blocker that is able to improve nerve conduction,20,21 and proprioceptive stimulation, can further promote motor recovery after severe SCI. Our findings suggest that treatments aimed at enhancing proprioceptive inputs are a promising therapeutic approach to improve functional recovery after severe SCI.

Results

Preferential and efficient targeting of lumbar DRG neurons

To accomplish selective hindlimb proprioceptive stimulation, a fundamental technical challenge was the specific targeting of proprioceptors located in lumbar DRGs. Recently, Chan et al.18 developed a novel type of viral capsid (AAV/PHP.S) that is able to preferentially target the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and sparsely infect the CNS by tail vein injection (Figure S1A). To further improve specificity, we sought to deliver this virus via intrathecal injection, which preferentially affects the lumbar DRGs.22,23 We first performed intrathecal injections of AAV/PHP.S-GFP into PV-Cre::Rosa26-tdTomato (RTM) reporter mice (PV-RTM) (Figure 1A). Two weeks later, we found that approximately 80.95% of PV+ proprioceptors in the lumbar DRGs were labeled by the AAV/PHP.S-GFP virus, whereas only 22.30% of those were labeled in cervical DRGs (Figures 1B and 1C). By contrast, virtually no neurons were labeled in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum (Figure 1E), despite the high density of PV+ interneurons in the brain (Figure S1B). In the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord, a few neurons, which did not overlap with PV+ interneurons, were labeled by GFP (Figure 1D). Together, these data demonstrate that intrathecal injection of PHP.S virus can efficiently and preferentially label the lumbar DRGs.

Figure 1.

Intrathecal injection of AAV/PHP.S preferentially and efficiently targets lumbar DRGs

(A) Schematic drawing of intrathecal injection and timeline. (B) Representative images of transverse sections of DRG labeled by PHP.S-GFP. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Quantification of the infection efficiency of parvalbumin (PV)-positive neurons in cervical or lumbar DRGs by PHP.S-GFP intrathecal injection. (D and E) Representative images of transverse sections of cervical and lumbar spinal cord (D), cortex (E, left), hippocampus (E, middle), and cerebellum (E, right) labeled by PHP.S-GFP. Scale bar in (D), 100 μm; in (E), 500 μm. n = 6; Student’s t test (two-tailed, unpaired) (C). ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Error bars, SD. See also Figure S1.

Establishing the staggered bilateral hemisection SCI model

As reported previously,4,24,25 the staggered bilateral hemisections at the thoracic (T) 7 and T10 spinal segments sever all descending axons passing T10 and result in complete loss of hindlimb locomotion. We performed the T7 lesion at the right side of the spinal cord, which slightly went beyond the midline, and the contralateral T10 lesion that ended at the midline (Figures 2A and 2B). Immunofluorescence labeling of 5-HT, a marker for serotonergic axons (Figure S2A), detected the presence of descending serotonergic axons rostral to the T7 lesion and within the damaged spinal segments between T7 and T10 (Figure 2C) but none in the lumbar spinal cords. The data verify the complete interruption of descending axons below T10 and the maintenance of neural circuits between T7 and T10. By labeling with NeuN, a neuronal marker, we found that the distribution and number of spinal neurons were not affected by the injury model (Figure S2B). Compared to the traditional contusion model, this model shows fewer surgical variations, which benefits the interpretation of experimental data.

Figure 2.

Establishment of staggered injury model and efficient expression of excitatory DREADD in lumbar proprioceptors

(A) Schematic drawing of the staggered bilateral hemisection injury model. Arrowheads show the lesions. (B) Representative images of GFAP immunostaining of horizontal spinal sections. White dashed line delineates the midline. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Representative images of 5-HT immunostaining of longitudinal (top) and transverse (bottom) spinal cord sections at 2 weeks after injury. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Schematic drawing of AAV-hM3Dq-mCherry viral infection in DRG proprioceptors. Red dots indicate hM3Dq-mCherry mainly expressed in lumbar PV+ DRGs. (E) Representative images showing mCherry-labeled PV+ neurons in cervical, thoracic, and lumbar DRGs (left panels) and the percentage of mCherry-labeled neurons in all PV+ neurons (right) in different DRGs. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) Representative images showing mCherry-labeled proprioceptive inputs in transverse spinal sections (left) and the quantification of the relative fluorescence intensity in different spinal segments (right). Scale bar, 100 μm. All images were taken using the same optical parameters. The fluorescence intensities were normalized to that in the lumbar spinal cord. n = 6; one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post hoc test (E and F). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Error bars, SD. See also Figures S2, S3, S11, and S12.

Selective expression of excitatory DREADD in lumbar proprioceptors

To enhance the excitability of proprioceptors in lumbar DRGs, we administered the AAV/PHP.S-Flex-hM3Dq-mCherry into PV-Cre mice by intrathecal injection. Consistent with the tracing data from AAV/PHP.S-GFP (Figures 1A and 1B), the majority of lumbar, with minimal thoracic or cervical, PV+ proprioceptors in DRGs were labeled by hM3Dq-mCherry (Figures 2D and 2E). The proprioceptive inputs were robustly observed mainly at the medial part of laminae V–VI in the lumbar spinal segments, with a much lower density of fibers seen in the cervical and thoracic segments (Figure 2F). No mCherry-labeled interneurons were detected throughout the spinal cord and brain (Figure S3C). The predominant expression of hM3Dq in the lumbar proprioceptors thus allows selective activation by clozapine N-oxide (CNO)26 (Figures S3A and S3B).

Proprioceptive stimulation promotes the recovery of stepping ability in paralyzed mice

Next, PV-Cre mice injected with AAV/PHP.S-Flex-hM3Dq-mCherry (DREADD) or AAV/PHP.S-Flex-placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) underwent staggered bilateral hemisection SCI 2 weeks later. One week after the surgery, CNO (0.5 mg/kg) was given to the mice daily by intraperitoneal administration until 6 weeks post SCI. The behavioral changes of the mice were measured weekly with Basso Mouse Scale (BMS), an established open-field locomotion test,27 and kinematic characterizations (Figure 3A). These behavioral measurements were all performed after 24 h since the last CNO injection. During the 6 weeks of CNO administration, animals in the control group (SCI plus PHP.S-PLAP injection) remained hindlimb paralyzed, with a BMS score of 0.96 ± 0.43 exhibiting no stepping (Figures 3B and 3C). By contrast, the majority of animals in the DREADD group (injected with AAV/PHP.S-Flex-hM3Dq-mCherry) displayed plantar placement of the hindpaw and weight-bearing stepping (64.7% with dorsal stepping and 17.6% with plantar stepping), with an elevated BMS score of 2.64 ± 0.55 by 6 weeks after injury (Figures 3B and 3C). These observations suggest that proprioceptive stimulation promotes recovery of stepping ability. Since stepping ability is the limiting step for motor recovery in severe SCI models,4,28 such recovery after enhancing proprioception is functionally meaningful.

Figure 3.

Proprioceptive stimulation promotes motor recovery in mice with staggered injury

(A) Experimental scheme. (B) BMS scores in DREADD mice and control SCI mice. (C) Percentage of mice that regained stepping ability at 6 weeks post injury in two groups. (D–G) Quantification of ankle joint movement (D), knee joint movement (E), stride length (F), and body weight support (G) of mice at 6 weeks post injury. (H) Schematic of the stick view for mouse hindlimb. (I) Color-coded stick view decomposition of mouse right hindlimb movements during swing, stance (intact), dragging (control SCI), and stepping (DREADD). (J) Representative EMG recordings (6 weeks post injury) from right tibialis anterior (TA) and gastrocnemius soleus (GS) muscles during movements in intact mice and mice that received no or proprioceptive stimulation. n = 16 and 17 for control and DREADD groups, respectively (B–G). Two-way repeated-measure ANOVA, followed by post hoc Bonferroni correction (B). Student’s t test (two-tailed, unpaired) (D–G). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Error bars, SD. See also Figures S4 and S10.

To further confirm the recovery of stepping ability evoked by proprioceptive stimulation, we performed both kinematic and electromyogram (EMG) recordings during active stepping. Kinematically, control mice showed minimal ankle movement, knee movement, stride length, and body weight support, while mice with chemogenetic stimulation of proprioceptors exhibited increased ankle movement, knee movement, stride length, and body weight support (Figures 3D–3I). Accordingly, EMG recordings found no obvious firing in ankle extensor gastrocnemius soleus (GS) muscle and flexor tibialis anterior (TA) muscle in control animals (Figures 3J and S4). In contrast, chemogenetically stimulated mice demonstrated simultaneous, rather than alternative, firing of GS and TA during stepping (Figures 3J and S4), a sign of partial recovery of body weight support.4 Together, our results demonstrate that chronic stimulation of lumbar proprioceptors enables most paralyzed mice to regain weight-bearing stepping ability after severe SCI.

Proprioceptive stimulation does not promote proprioceptive axon sprouting, descending axon regrowth, or propriospinal neuron remodeling

Reportedly, proprioceptive axon sprouting or descending axon regrowth may facilitate functional recovery after SCI.21,29 We thus determined whether our proprioceptive-stimulation-mediated motor recovery is dependent on the sprouting of these axons. To examine whether DREADD stimulation promoted proprioceptive axon sprouting, we immunolabeled the proprioceptive inputs using PV staining. No remarkable axon sprouting in rostral, inter-lesion, or lumbar spinal segments was detected (Figure S5). Immunostaining with anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (vGlut1), a marker for excitatory axon terminals,12 also found no overt changes of axon terminal throughout the spinal segments at different time points after DREADD-mediated proprioceptive stimulation (Figures 4A–4C). Of note, the vGlut1 expression in the intermediate part of laminae V–VI largely represents innervation by proprioceptive axonal terminals.16

Figure 4.

Proprioceptive stimulation does not promote proprioceptive or supraspinal descending axon sprouting

(A) Schematic (left) and representative images (right) showing proprioceptive axon terminals by vGlut1 immunostaining in different spinal segments at 2 or 8 weeks after injury in mice that received no or proprioceptive stimulation. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B and C) Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of vGlut1 immunostaining at acute and chronic stages in mice without proprioceptive stimulation (B) and that in mice that received no or proprioceptive stimulation at the chronic stage (C). (D) Left: schematic of anterograde tracing of the corticospinal tract axons. Green arrowhead: injection of AAV2/8-ChR2-eYFP. Green line: axons descending from right cortex. Right: representative images of GFP immunostaining in different spinal segments at acute and chronic stages after SCI. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E and F) Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of GFP immunostaining at acute and chronic stages in mice without proprioceptive stimulation (E) and that in mice that received no or proprioceptive stimulation at the chronic stage (F). (G) Left: schematic of anterograde tracing of the reticulospinal tract axons. Green arrowhead: injection of AAV2/8-ChR2-eYFP. Green line: axons descending from the right reticular formation. Right: representative images of GFP immunostaining in different spinal segments at acute and chronic stages after SCI. Scale bar, 100 μm. (H and I) Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of GFP immunostaining at the acute and chronic stages in mice without proprioceptive stimulation (H) and that in mice that received no or proprioceptive stimulation at the chronic stage (I). All images were taken using the same optical parameters. The fluorescence intensities were normalized to rostral spinal levels at 2 weeks post injury. n = 5 for each group. Two-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Bonferroni correction (B, C, E, F, H, and I). ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ns, not significant. Error bars, SD. L, left side; R, right side. See also Figures S5–S8.

To assess whether proprioceptive stimulation promoted the sprouting or regeneration of descending axons (e.g., corticospinal tract [CST] projections), we unilaterally injected AAV2/8-ChR2-expressing yellow fluorescent protein (AAV2/8-ChR2-eYFP) into the right sensorimotor cortex of the mice to anterogradely trace axons in the spinal cord at different time points (1 day or 6 weeks post-SCI) (Figure S6A). Two weeks later, we detected no significant axon sprouting or regeneration in the rostral, inter-lesion, or lumbar spinal segments (Figures 4D–4F). Similarly, anterograde tracing of reticulospinal axons by injecting the AAV2/8-ChR2-eYFP to the right reticular formation in the brainstem (Figure S6B) showed that there was no significant sprouting of these axons in the DREADD-injected mice (Figures 4G–4I). Additionally, 5-HT immunohistochemistry also demonstrated no serotonergic axon sprouting in the lumbar spinal cord (Figure S7).

To assess whether proprioceptive stimulation promoted the reorganization of propriospinal neurons or the remodeling of synaptic contacts between descending axons and propriospinal neurons, we stereotaxically injected AAV9-syn-Synaptophysin-mCherry to reticular formation, and retro-GFP to lumbar segments (L2–4) after 6 weeks of CNO administration (Figure S8A). As shown in Figures S8B and S8C, proprioceptive stimulation did not promote the reorganization of inter-lesion propriospinal neurons. Next, we used Synaptophysin-mCherry to label the synaptic contacts. As shown in Figures S8D and S8E, the number of synaptic contacts between reticulospinal fibers and propriospinal neurons did not show significant differences between the two groups. These results revealed that proprioceptive stimulation did not affect the density of synaptic contacts between reticulospinal fibers and propriospinal neurons. Together, DREADD-mediated proprioceptive stimulation does not promote the sprouting of lumbar proprioceptive axons or supraspinal axons into the relay zone between the injury sites or the remodeling of propriospinal neurons to induce functional recovery.

Proprioceptive stimulation alters locomotion evoked activation pattern of lumbar interneurons

Previous studies showed that epidural stimulation, combined with rehabilitation training, can modulate the excitability of lumbar interneurons and activate locomotion-related circuitry.11,30 We hypothesized that stimulation of lumbar proprioceptors may also transform local spinal circuits toward a more physiological pattern of neuronal activity, which is more responsive to the supraspinal commands relayed via propriospinal neurons. We examined the expression of c-Fos, a neuronal activity marker previously described,24 in the lumbar spinal cord after 1 h walking on a treadmill at 6 weeks post SCI (Figure 5A). In each group, almost all c-Fos-positive cells in the spinal sections were positively co-stained with NeuN (Figures 5B and S9A), confirming the neuronal specificity of the c-Fos signal. Consistent with previous studies,30,31 c-Fos-positive neurons (c-Fos and NeuN double positive) were widely distributed in the control SCI mice, including nociception/touch-related superficial dorsal horn (laminae I–IV), proprioception-related deep dorsal horn and intermediate spinal cord (laminae V–VI), and motor-related ventral spinal cord (laminae VII–X) (Figures 5C, 5D, and 5F). In contrast, proprioceptive stimulation significantly reduced the number of c-Fos-positive neurons in the dorsal/intermediate and ventral spinal cord (Figures 5C, 5D, 5F, and S9B) but robustly increased the number of c-Fos-positive neurons in the proprioceptive projection area (proprio-area, located in medial part of laminae V–VI) of the lumbar spinal cord (Figures 5E, 5F, and S9B).

Figure 5.

Proprioceptive stimulation alters lumbar interneuron activation pattern

(A) Experimental scheme. (B) Representative images showing the co-localization of the c-Fos and NeuN immunostaining. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C and D) Schematic (C) and representative images (D) of lumbar spinal sections with c-Fos immunostaining in injured mice with no or proprioceptive stimulation and intact mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) The zoom-in images of c-Fos immunostaining in lumbar sections of DREADD mice (d) and lumbar sections of PV-Cre::Rosa26-tdTomato (PV-RTM) mice (right). Note that the c-Fos expression (d) mainly concentrated in the region targeted by proprioceptive axon terminals (white dashed circle) (right). Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) Quantification of the number of c-Fos+ NeuN+ neurons per section in the dorsal/intermediate zones (laminae I–VI), the ventral spinal cord (laminae VII–X), and the proprio-area (medial part of laminae V–VI) in all groups. (G) Representative confocal images showing the proprioceptive axon terminal formed synapses on the c-Fos+ interneurons in injured mice with (top) or without stimulation (bottom). Scale bar, 10 μm. (H) Top: the percentage of c-Fos+ neurons that form synapses with proprioceptive terminals in DREADD and control group. Bottom: the average number of boutons on each vGlut1+ c-Fos+ NeuN+ interneuron in the two groups. The arrowheads indicate the boutons. n = 6 for each group. Two-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Bonferroni correction (F). Student’s t test (two-tailed, unpaired) (H). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, and ns, not significant. Error bars, SD. See also Figure S9.

To further investigate the synaptic connections between proprioceptive axons and activated interneurons, we stained spinal sections with anti-vGlut1, which is enriched at proprioceptive axon terminals. We found that a substantial portion of activated interneurons in the proprio-area were directly contacted by proprioceptive axonal terminals, with more boutons on the soma of c-Fos+ interneurons, in mice with proprioceptive stimulation compared to that in the control SCI mice (Figures 5G and 5H). These data indicate that chronic proprioceptive stimulation specifically activates proprioception-receptive interneurons, which may further activate and/or remodel local spinal circuits to improve locomotion recovery after SCI.

Proprioceptive stimulation facilitates the transmission of supraspinal inputs

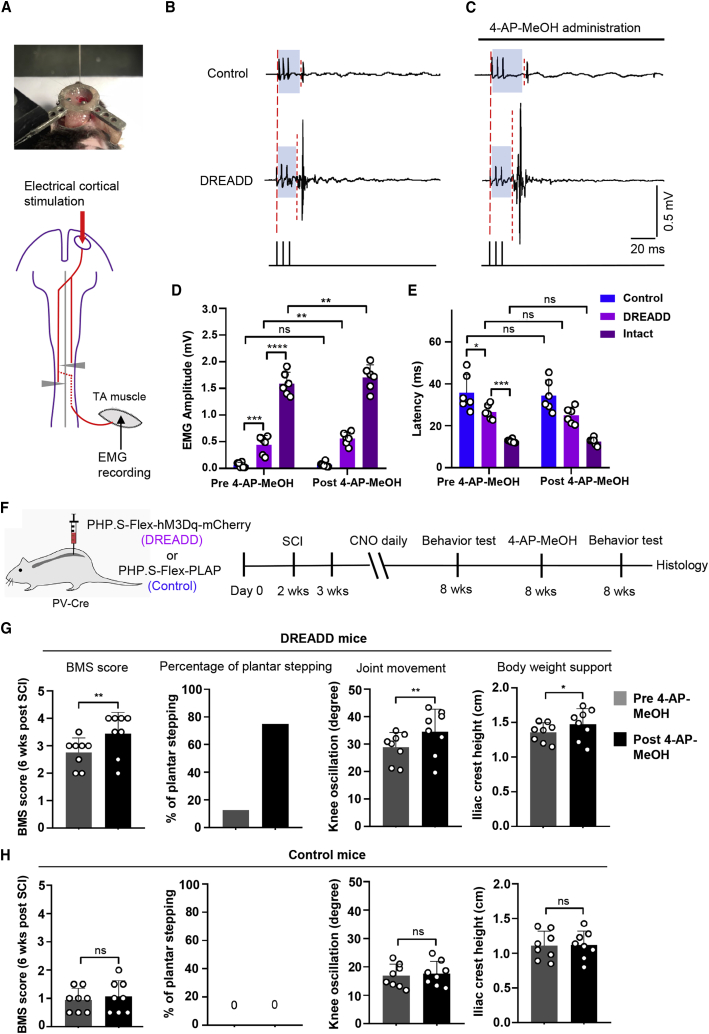

The bilaterally hemisected mice remained completely paralyzed even with partially relayed supraspinal commands. This may be attributed to dysfunctional lumbar spinal circuits after SCI. Therefore, we examined whether proprioceptive-stimulation-elicited activation of spinal interneuron circuits may facilitate the transmission of relayed descending inputs toward the lumbar motor neuron pools. Using electrical stimulation of the motor cortex and EMG recording in the ipsilateral TA muscle (Figure 6A), we found that chronic proprioceptive activation significantly increased the amplitude of the EMG responses and reduced the EMG latency after cortical stimulation (Figures 6B, 6D, 6E, and S9C). These results indicated that proprioceptive stimulation increases the transmission efficiency of supraspinal inputs to the lumbar motor neurons.

Figure 6.

4-AP-MeOH further improves supraspinal input transmission and motor recovery in mice with proprioceptive stimulation

(A) Image and schematic of electrical cortical stimulation and EMG recording experiments. (B) Representative EMG responses recorded in TA muscle evoked by a train of cortical stimulations in injured mice with no or proprioceptive stimulation. (C) Representative EMG responses in the two groups after 4-AP-MeOH administration. (D and E) Quantification of the amplitude (D) and latency (E) of the EMG signals in intact mice or injured mice with no or proprioceptive stimulation before and after 4-AP-MeOH treatment. (F) Experimental scheme for (G) and (H), re-measurement of behavioral tests immediately after the 4-AP-MeOH treatment. (G) Quantification of BMS score, percentage of plantar stepping, knee joint movement, and body weight support of mice with proprioceptive stimulation at 6 weeks post injury before and after the 4-AP-MeOH treatment. (H) Quantification of BMS score, percentage of plantar stepping, knee joint movement, and body weight support of mice without proprioceptive stimulation at 6 weeks post injury before and after the 4-AP-MeOH treatment. n = 6 mice for each group. Two-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Bonferroni correction (D and E). n = 8 mice for each group. Student’s t test (two-tailed, paired) (G and H). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Error bars, SD. See also Figure S9.

Proprioceptive stimulation combined with nerve conduction enhancement further improves supraspinal input transmission and motor recovery after SCI

Previous studies showed 4-AP-MeOH, a voltage-gated potassium channel blocker, can facilitate nerve conduction and improve behavioral performance in the optic nerve injury model and incomplete SCI model.20,21 To investigate whether a combinatorial strategy of nerve conduction enhancement with proprioceptive stimulation could further promote the transmission of supraspinal inputs, and thus facilitate motor control, we applied 4-AP-MeOH to SCI mice with or without chronic proprioceptive stimulation. We found that 4-AP-MeOH treatment alone had no significant effects on EMG responses in the SCI mice with no proprioceptive stimulation (Figures 6B–6E). However, it robustly increased the amplitudes of the EMG in the proprioception-stimulated SCI mice (Figures 6B–6E), which is similar to that in intact mice (Figures 6D, 6E, S9C, and S9D). These results indicated that 4-AP-MeOH treatment further improves the transmission of descending commands to lumbar motor pools through proprioceptive-stimulation-modulated lumbar interneuron circuits.

To examine whether 4-AP-MeOH application enhances the recovery of stepping ability, we performed BMS and kinematic observation before and after 4-AP-MeOH administration at 6 weeks post injury (Figure 6F). While 12.5% of the SCI mice achieved the plantar stepping after proprioceptive stimulation (Figure 6G; Video S1), with additional application of 4-AP-MeOH, 75% of the mice achieved plantar stepping, with the BMS score increased from 2.75 ± 0.53 to 3.44 ± 0.78 (Figure 6G; Video S2). Moreover, mice also showed significantly improved knee joint movement and body weight support (Figure 6G). In contrast, the control SCI mice remained paralyzed and showed no significant behavioral improvements after 4-AP-MeOH treatment alone (Figure 6H; Video S3). Together, these results demonstrate that combinatorial proprioception stimulation and nerve conduction facilitation have synergistic effects on motor recovery after severe SCI.

Discussion

Although severe spinal cord injuries eliminate the descending axons, the sensory afferents below injury sites, such as the proprioceptive feedback circuits, usually remain intact.3,4 By developing synaptic contacts with various spinal interneurons and motor neurons, proprioceptors engage in sensorimotor control and may serve as a trigger to modulate local spinal circuits and facilitate the restoration of motor control after SCI. Using a bilateral hemisection SCI model and chemogenetic tools, we demonstrated that selective proprioceptive sensory stimulation facilitates the transmission of supraspinal commands to the lumbar motor neuron pools, thereby promoting the recovery of hindlimb stepping ability through activation of proprioception-receiving spinal interneurons. Moreover, the application of 4-AP-MeOH for enhancing nerve conductance can further improve the transmission of supraspinal inputs and motor recovery in these proprioception-stimulated mice. Such a combinatorial approach to achieve synergistic effects may be used as a promising strategy to treat SCI.

Clinically, epidural stimulation has been shown to improve the motor function recovery after SCI.11,32,33 Studies have suggested that large myelinated fibers, including proprioceptive and cutaneous afferents, may be engaged upon epidural stimulation.34, 35, 36, 37 Yet, precise information regarding the roles of proprioceptive and cutaneous sensory inputs in functional recovery after SCI is scarce, partly due to the technical challenges in efficient and selective manipulation of the lumbar sensory pathways.23,38 Recent advances in viral engineering allow for selective targeting of different subsets of DRG neurons in Cre-expressing transgenic mouse lines. Using the newly developed AAV-PHP.S capsid, which has high infection efficiency (~82%) in DRG neurons,18 along with the PV-Cre mouse line and intrathecal injection, we achieved efficient and preferential labeling of lumbar proprioceptors. By introducing CNO-responsive DREADD viruses, we were able to selectively stimulate the lumbar DRG proprioceptive pathway. By achieving highly specific and efficient targeting of the lumbar DRG neurons, intrathecal injection of AAV2/PHP.S virus provides a powerful tool for the functional dissection of sensorimotor circuits involved in pain, itch, or proprioception and genetic therapies for sensory neuropathies.

Proprioceptive feedback plays a critical role in modulating the normal locomotion and maintaining the spontaneous functional recovery after incomplete SCI.7,15,39,40 Our study showed that direct stimulation of proprioceptive inputs can promote motor recovery in severe SCI, indicating the significance of proprioception in motor recovery in both incomplete and severe SCI. Among various DRG sensory neurons, proprioceptors only account for approximately 25%.16 Therefore, why proprioceptive stimulation has such a profound impact on motor recovery after SCI is an important question to address. We speculate that this may be related to the specific, yet dense, distribution of proprioceptive axon fibers within the spinal cord. Unlike the superficial projection of nociceptive and tactile inputs, proprioceptive inputs project more ventrally and are closer to motor neuron pools.13,41 Such differential projective features may provide advantages for proprioceptive inputs in connecting with ventral spinal neurons and motor neurons after SCI. Moreover, proprioceptive afferents may further engage spinal neurons to recruit motor circuits. Studies suggest that interactions between motor neurons and ventral spinal interneurons play important roles in modulating extensor-flexor coordination and locomotor rhythm generation.42,43 Since proprioceptive afferents make direct synaptic contacts with those neurons, enhancing proprioceptive inputs may act to strengthen these motor circuits and promote motor restoration after SCI. In line with this theory, our study found that chronic proprioceptive stimulation specifically activated proprioception-receptive spinal interneurons, which can relay the proprioceptive information to motor neurons and are involved in the motor circuits.

We also demonstrated that proprioceptive stimulation promotes motor recovery by facilitating the supraspinal input transmission. Previous studies have shown that severe SCI leads to global activation of lumbar spinal neurons after extensive treadmill walking,30,31 which was likely attributable to the spinal “disinhibition” induced by the elimination of descending brain inputs.44,45 Such non-specific and global activation of spinal neurons leads to dysfunction of local spinal circuits and loss of responsiveness to the spared descending commands. Notably, chronic proprioceptive stimulation appears to suppress such global activation but selectively activate proprioception-receptive spinal neurons, suggesting that enhancing proprioceptive afferents can reinforce the proprioception-related local interneuron circuits to facilitate motor recovery. Such functionally specific activation of proprioception-receptive spinal interneurons may be critical to facilitate the transmission of descending inputs toward the lumbar motor neuron pool. In line with our observations, Chen et al.4 discovered that modifying the inhibitory spinal interneuron excitability improved the brain-derived descending motor control and recovery of stepping ability in severe SCI mice. Our study suggests that modulating peripheral proprioception to fine-tune the excitability of spinal interneurons is a promising strategy to reestablish the responsiveness of local spinal circuits, which can relay brain-derived descending inputs to facilitate motor recovery.

In our study, the SCI mice with proprioceptive stimulation achieved partial weight-bearing stepping. A recent study applied CLP290 to the same mouse SCI model and found that the paralyzed mice regained dorsal stepping and plantar stepping.4 Such findings are consistent with our results. In details, improvements in the iliac crest height and the stride length in our proprioception-stimulated mice are not as significant as those described in Chen et al.4 However, with additional administration of 4-AP-MeOH, the iliac crest height significantly improved in our study when compared to CLP290-treated animals in Chen et al.4 In addition, a substantial number of previous studies applied combinatory treatments, including epidural electrical stimulation, administration of serotonin receptor agonists (5HT1A/7 and 5HT2A/C) and dopamine (D1) receptor agonists, and overground training, to various rat SCI models,24,46 which allow animals to regain a stepping pattern similar to the intact condition. These studies indicated that combinatory approaches are encouraged to maximize functional recovery after SCI.

The current study first established a highly specific and efficient viral approach to target the lumbar DRG neurons and demonstrated that chronic activation of proprioceptive inputs is beneficial to motor recovery after severe SCI, by activating proprioception-receptive interneurons and facilitating the transmission of brain-derived inputs toward motor neuron pools. Additional application of 4-AP-MeOH for enhancing nerve conduction further improved motor recovery after proprioceptive stimulation in SCI mice. These findings suggest that a combinatorial use of proprioceptive stimulation and nerve conduction enhancement can serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for treating SCI. While various rehabilitation treatments have beneficial effects on functional recovery after SCI,24,30,47 whether proprioceptive stimulation can further enhance the functional restoration mediated by rehabilitation training after severe SCI warrants further investigation. In summary, our current findings demonstrate a promising strategy to restore motor function after SCI.

Materials and methods

Mice strains

All experimental procedures were ethically approved by the ethical board of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University. Mice used in this study included: C57BL/6 wild-type (Charles River, strain code #027), PV-Cre (Jax #017320), and Rosa26-tdTomato (Jax #007909) mouse strains, which were maintained on C57BL/6 genetic background. All the experimental and control animals used in behavioral measurements were littermates.

Viral preparation

For neural tracing, AAV2/PHP.S-Syn-GFP, AAV2/8-ChR2-eYFP, AAV2/retro-CAG-GFP, and AAV2/9-Syn-Synaptophysin-mCherry were used. For the manipulation of proprioceptors, AAV2/PHP.S-Syn-FLEX-PLAP, AAV2/PHP.S-Syn-FLEX-hM3Dq-mCherry, and AAV2/PHP.S-Syn-FLEX-HA-hM3Dq were applied. All the viruses were purchased from BrainVTA (Wuhan, China). To test the infection efficiency and specificity of AAV/PHP.S, AAV2/PHP.S-Syn-GFP was delivered into the intradural space of adult PV-Cre::Rosa26-tdTomato mice by intrathecal injection, followed by epifluorescence visualization of spinal cord slices under a microscope. Similarly, AAV2/PHP.S-Syn-FLEX-hM3Dq-mCherry was intrathecally injected to adult PV-Cre mice to determine the infection rate of DREADD. For spinal cord injury experiments, AAV2/PHP.S-Syn-FLEX-hM3Dq-mCherry or AAV2/PHP.S-Syn-FLEX-HA-hM3Dq, and AAV2/PHP.S-Syn-FLEX-PLAP were intrathecally injected to the mice in the DREADD (proprioception-stimulation) group and control SCI group, respectively. For corticospinal tract tracing and reticulospinal anterograde tracing, AAV2/8-ChR2-eYFP was stereotaxically injected to cortex and brainstem, respectively. To label synaptic inputs from the reticulospinal tract, AAV2/9-Syn-Synaptophysin-mCherry was stereotaxically injected to reticular formation. For lumbar retrograde tracing, AAV2/retro-CAG-GFP was stereotaxically injected to lumbar segments (L2–4).

Experimental design

Animals were randomly assigned into different groups (Figure S10). Briefly, 6 adult PV-Cre::Rosa26-tdTomato mice were used to assess the infection efficiency of intrathecally injected AAV2/PHP.S-GFP viruses. Six adult PV-Cre mice were used to assess the infection rate of AAV2/PHP.S-FLEX-hM3Dq-mCherry by intrathecal injection. Forty-one adult female PV-Cre mice were assigned to the DREADD group, and 51 female PV-Cre mice were assigned to the control group. Then, 18 mice were randomly selected from each group for behavior assessment. At the endpoint, 6 mice were used for EMG recording and 6 for cortical stimulation and c-Fos immunostaining from individual groups. In the corticospinal tract tracing experiment and PV and vGlut1 immunohistochemistry analyses, 5 mice in the control group were used to assess the corticospinal axon or local proprioceptive axon distribution at 2 weeks post injury and 5 were used to assess axon sprouting at 8 weeks post injury from each group. For the reticulospinal anterograde tracing experiment and 5-HT immunohistochemistry, 5 mice in the control group were included to assess the reticulospinal axon or serotonergic axon distribution at 2 weeks post injury, and 5 mice in each group were included to assess the axon sprouting at 8 weeks post injury. For propriospinal neuron labeling experiments, each group included 5 mice. For 4-AP-MeOH behavioral experiments, each group included 8 mice. In the EMG recording, cortical stimulation, and c-Fos staining experiments, 18 adult female wild-type littermates were included as the intact group (n = 6 in each experiment).

Animals with spared serotonergic axons detected at lumbar segments, which indicates incomplete staggered lesions, were excluded from the experiments (one mouse in the DREADD group and two mice in the control group) (Figures S11 and S12).

Intrathecal injection

Intrathecal injection was performed as previously described.48 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane, and a nose cone was placed to maintain the isoflurane administration during the procedure. A 50 μL Hamilton syringe attached with a 30-gauge (G) needle was used to extract 10 μL virus (titers were adjusted to 1–2 × 1013 copies/mL for injection) for each mouse. The spinous process of the L6 was held by the left hand, the needle was punctured between the groove of the L5 and L6 vertebrae, then the virus was slowly injected. After the procedure, the mouse was removed from the nose cone. The intrathecal injection was repeated after 24 h for each mouse to ensure sufficient viral delivery.

Surgical procedures for spinal cord injury

After the anesthesia by inhalation of 1.5% isoflurane, staggered bilateral hemisection spinal cord injury was performed in mice at the T7 and T10 levels as previously described.4,24,25 A midline incision was performed to the skin over the thoracic spine. Thoracic vertebrae were exposed, followed by T710 laminectomy. For T7 over-hemisection, a scalpel and micro-scissors were employed to hemisect the spinal cord on the right side, and then slightly cross the midline to interrupt the contralateral dorsal column and ventral pathways. For T10 hemisection, only the spinal cord on the left side was interrupted until the midline. Then the muscles and skin were carefully sutured. After the surgery, 1 mL of saline was subcutaneously injected for each mouse, and a heating pad was used to keep the mice warm until wakefulness. Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was subcutaneously administrated every 12 h for 3 days post injury to reduce the pain. The mice bladders were manually emptied twice daily. The body weight was monitored every week, and the mice were sacrificed after experiencing more than 15% body weight loss. All SCI models were performed by a professional surgeon.

Compound treatment for SCI mice

To induce the activation of the DREADD Gq receptors, CNO (Enzo Life Sciences [BML-NS105-0005], 0.5 mg/kg, dissolved in 0.9% NaCl) was intraperitoneally delivered to mice in the control group and DREADD group daily for 6 weeks from 1 week post injury. To improve the supraspinal input conduction, 6 weeks post injury, 4-AP-MeOH (Santa Cruz [sc-267247], 1 mg/kg, suspended in 0.9% NaCl) was intraperitoneally delivered to the mice in the control group and the DREADD group at 6 weeks post injury.

Behavioral experiments

The BMS, a locomotor open field rating scale,27 was applied to assess motor function weekly. In this test, movement of the ankle joint less than half of the joint excursion is defined as slight ankle movement (scored as BMS 1.0), and if the ankle moves more than half of the excursion, it is defined as extensive ankle movement (scored as BMS 2.0). When the dorsal paw provides weight support in some stepping cycles, the stepping is defined as dorsal stepping (scored as BMS 3.0). If the plantar paw provides weight support throughout the stance phase, this stepping is defined as plantar stepping (scored as BMS 4.0). All BMS behavior tests were performed by one investigator, who was blind to the animal groups. The behavioral tests were performed 24 h after the systematic administration (intraperitoneal injection) of CNO. Similar to a previously described study,49 the hindlimb kinematic analysis was performed using a transparent plexiglass runway (length: 100 cm; width: 4 cm; height: 15 cm). Briefly, mice were placed in the plexiglass runway to assess ground-walking locomotion. The iliac crest, hip joint, knee joint, ankle, and toe were highlighted by a marker pencil to simplify the data processing. 12–15 gait cycles were recorded for each mouse by a GoPro camera (60 frames/s). The highlighted anatomical landmarks were utilized to assess the knee oscillation, iliac crest height, and stride length for each gait cycle for control and experimental groups. The knee oscillation represents the knee joint movement, and the iliac crest height represents the body weight support. All data analysis was performed blindly by an investigator. The endpoint trajectory of hindlimb movement was extracted using MATLAB blindly by a technician.

EMG recording

EMG recordings of intact, control SCI, and DREADD mice were performed as previously described.50 Briefly, mice were randomly selected from each group, and the customized intramuscular EMG electrodes were implanted into TA muscle and GS muscle to record EMG activity. The electrode (793200, A-M Systems) was introduced into the mid-belly of the selected muscle of the right hindlimb using a 30-gauge needle, and a ground wire was fixed subcutaneously in the mid-back area. All electrode wires were delivered subcutaneously through the back and connected to a customized percutaneous connector cemented to the skull. After 1–2 weeks’ recovery from the surgery, EMG signals were obtained by a differential AC amplifier (1700, A-M Systems, Sequim, WA, USA), filtrated at 10–1,000 Hz, sampled at 4 kHz by a digitizer (PowerLab 16/35, ADInstruments), and analyzed by LabChart 8 (ADInstruments) by an investigator who was blind to the group assignment.

Cortical stimulation

Cortical stimulation and EMG response recording of intact, control SCI, and DREADD mice were performed according to previous studies.4,24 Briefly, mice were randomly selected from each group, and head plates were attached to the skull. Buprenorphine was administrated by subcutaneous injection every 12 h for 2 days after surgery. After 1 week of recovery from the surgery, the head plate was secured in a clamp to ensure that the heads did not move, and monopolar electrodes were placed epidurally on the hindlimb area of right motor cortex (0~1.5 mm caudal to bregma, 0.5~1.5 mm lateral to bregma). The EMG electrode (793200, A-M Systems) was introduced into the mid-belly of the TA muscle of the right hindlimb using a 30-gauge needle, and a ground wire was fixed subcutaneously in the mid-back area. The pulse generator and isolator (Master 9 and Iso-Flex, A.M.P.I.) were utilized to generate a train of low-intensity electrical stimuli (0.2 ms biphasic pulse, 100 ms pulse train, 20 Hz, 0.5–1.5 mA), which was delivered to the cortex when the animal was fully awake and quadrupedal standing. Following the cortical stimulation, the EMG activities of right TA muscle were recorded. The amplitude and latency of evoked EMG responses were calculated from the EMG activities. During the stimulation, if we found any signs of increased respiration rate, severe scratching, hunched posture, or stiff movements, we would abort the procedure and apply pain killer. EMG recordings and calculation were performed by an investigator who was blind to the group assignment.

Anterograde and retrograde tracing experiments

After anesthesia by inhalation of 1.5% isoflurane, mice were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus with a bite bar and ear bars. For the corticospinal tract tracing experiment,21 a rectangular burr hole was drilled above the right sensorimotor cortex, the glass micropipettes were attached to the injection pump, and AAV2/8-ChR2-eYFP (titers were adjusted to 1–2 × 1013 copies/mL) was injected to the following coordinates: 1, 0.5, 0, −0.5, −1, and −1.5 mm caudal to bregma, 1.3 mm lateral to bregma, and 0.6 mm ventral to the brain surface (100 nL per injection site). For the reticulospinal anterograde tracing experiment,51 the glass micropipettes were guided through the burr hole above the cerebellum, and AAV2/8-ChR2-eYFP or AAV2/9-syn-Synaptophysin-mCherry was delivered to the right reticular formation in the brainstem. The injection coordinates were −1.5, −2.0, and −2.5 mm caudal to lambda, 0.4 mm lateral to lambda, and −4.5 mm ventral to the cerebellum surface (100 nL per injection site). After the brain injection, the burr holes were covered by Gelfoam, and the skin incision was sutured.

For retrograde tracing at the lumbar spinal cord, AAV2/retro-CAG-GFP (titers were adjusted to 1–2 × 1013 copies/mL) was injected into bilateral lumbar 2–4 segments, as described previously.4 Injection coordinates were 0.5 mm lateral to the midline, and 3 injection sites were separated by 1 mm. Each site was injected 3 times at −0.4 mm, −0.8 mm, and −1.2 mm ventral to the surface (18 injections, 100 nL per injection).

Immunohistochemistry and imaging

The animals were sacrificed as previously described.52 Briefly, the mice were perfused transcardially with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) diluted in PBS followed by post-fixation overnight in 4% PFA. Then the brain, spinal cord, and DRG were harvested. The tissues were cryo-protected with 30% sucrose diluted in PBS overnight and sliced using cryostat (section thickness: 14 μm for DRG, 40 μm for spinal cord, and 50 μm for brain). Sections were blocked with 10% normal donkey serum with 0.2% Triton-100 for 2 h before staining. The primary antibodies (room temperature, overnight) used were: chicken anti-GFP (Abcam [ab13970], 1:1,000), rabbit anti-RFP (Abcam [ab34771], 1:1,000), goat anti-tdTomato (Mybiosourse [MBS448092], 1:300), goat anti-5-HT (Immunostar [20079], 1:800), rabbit anti-GFAP (DAKO [Z0334], 1:800), rabbit anti-c-Fos (Cell Signaling [2250s], 1:800), rat anti-HA (Sigma [11867423001], 1:200), mouse anti-NeuN (Millipore [MAB377], 1:800), rabbit anti-parvalbumin (Swant [PV27], 1:800) and guinea pig anti-vGlut1 (synaptic systems [135304], 1:1,000). Secondary antibodies (room temperature, 3 h), including Alexa Fluor 405-conjugated donkey anti-guinea pig; Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-chicken, rabbit, goat, and mouse; Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit and goat; Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated donkey anti-mouse, rabbit, and rat, were purchased from Invitrogen.

c-Fos expression in spinal neurons was induced as previously described.30 Briefly, the animals received 1-h continuous free walking (intact mice), stepping (DREADD mice), or dragging (control SCI mice) on a treadmill. The animals were returned to their cages and were then perfused with 4% PFA about 2 h later.

The confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss 700 or Zeiss 710) was used to image the brain, spinal cord, and DRG sections. To determine the descending or local proprioceptive axonal sprouting, we compared the relative fluorescence intensity of corticospinal tract projections, reticulospinal tract projections, 5-HT axonal staining, parvalbumin axonal staining, and vGlut1 staining as previous studies.4,21 All images were taken using a low magnification lens (10×) under the same optical settings. After sub-threshold processing of the background and normalization by area, densitometry measurements were conducted using FIJI software. The analysis was performed blindly by a separate investigator.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 software. Two-tailed Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA, and two-way ANOVA were used according to the experimental design. Bonferroni’s correction was used to adjust the p value of multiple comparisons. Data in all figures were described as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significance level is defined as follows: ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, and ns, no statistical significance (p ≥ 0. 05).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFE0114200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571209, 81771349, and 81901264), and the Foundation from the Health Bureau of Zhejiang Province (2021KY159).

Author contributions

Z.G. designed and performed most of the experiments, analyzed all data, prepared figures, and wrote the manuscript; Y.Y. performed the tracing experiments; Z.F., X.L., C.M., and H.S. performed the behavior measurement and immunohistochemistry; Z.Z. contributed to statistical analysis; and Y.H., Y.W., and X.H. contributed to experimental design, data interpretation, and paper revision.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.023.

Contributor Information

Yihe Hu, Email: xy_huyh@163.com.

Yue Wang, Email: wangyuespine@zju.edu.cn.

Xijing He, Email: he_xijing123@126.com.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Kakulas B.A. A review of the neuropathology of human spinal cord injury with emphasis on special features. J. Spinal Cord Med. 1999;22:119–124. doi: 10.1080/10790268.1999.11719557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fawcett J.W., Curt A., Steeves J.D., Coleman W.P., Tuszynski M.H., Lammertse D., Bartlett P.F., Blight A.R., Dietz V., Ditunno J. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:190–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Shea T.M., Burda J.E., Sofroniew M.V. Cell biology of spinal cord injury and repair. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:3259–3270. doi: 10.1172/JCI90608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen B., Li Y., Yu B., Zhang Z., Brommer B., Williams P.R., Liu Y., Hegarty S.V., Zhou S., Zhu J. Reactivation of Dormant Relay Pathways in Injured Spinal Cord by KCC2 Manipulations. Cell. 2018;174:521–535.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossignol S., Dubuc R., Gossard J.P. Dynamic sensorimotor interactions in locomotion. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:89–154. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietz V., Fouad K. Restoration of sensorimotor functions after spinal cord injury. Brain. 2014;137:654–667. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeoka A., Vollenweider I., Courtine G., Arber S. Muscle spindle feedback directs locomotor recovery and circuit reorganization after spinal cord injury. Cell. 2014;159:1626–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouyer L.J., Rossignol S. Contribution of cutaneous inputs from the hindpaw to the control of locomotion. II. Spinal cats. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;90:3640–3653. doi: 10.1152/jn.00497.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavrov I., Courtine G., Dy C.J., van den Brand R., Fong A.J., Gerasimenko Y., Zhong H., Roy R.R., Edgerton V.R. Facilitation of stepping with epidural stimulation in spinal rats: role of sensory input. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7774–7780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1069-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morawietz C., Moffat F. Effects of locomotor training after incomplete spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013;94:2297–2308. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angeli C.A., Edgerton V.R., Gerasimenko Y.P., Harkema S.J. Altering spinal cord excitability enables voluntary movements after chronic complete paralysis in humans. Brain. 2014;137:1394–1409. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bui T.V., Akay T., Loubani O., Hnasko T.S., Jessell T.M., Brownstone R.M. Circuits for grasping: spinal dI3 interneurons mediate cutaneous control of motor behavior. Neuron. 2013;78:191–204. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Windhorst U. Muscle proprioceptive feedback and spinal networks. Brain Res. Bull. 2007;73:155–202. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hantman A.W., Jessell T.M. Clarke’s column neurons as the focus of a corticospinal corollary circuit. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:1233–1239. doi: 10.1038/nn.2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akay T., Tourtellotte W.G., Arber S., Jessell T.M. Degradation of mouse locomotor pattern in the absence of proprioceptive sensory feedback. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:16877–16882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419045111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeoka A., Arber S. Functional Local Proprioceptive Feedback Circuits Initiate and Maintain Locomotor Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Rep. 2019;27:71–85.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miao C., Cao Q., Moser M.B., Moser E.I. Parvalbumin and Somatostatin Interneurons Control Different Space-Coding Networks in the Medial Entorhinal Cortex. Cell. 2017;171:507–521.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan K.Y., Jang M.J., Yoo B.B., Greenbaum A., Ravi N., Wu W.L., Sánchez-Guardado L., Lois C., Mazmanian S.K., Deverman B.E., Gradinaru V. Engineered AAVs for efficient noninvasive gene delivery to the central and peripheral nervous systems. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:1172–1179. doi: 10.1038/nn.4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armbruster B.N., Li X., Pausch M.H., Herlitze S., Roth B.L. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:5163–5168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bei F., Lee H.H.C., Liu X., Gunner G., Jin H., Ma L., Wang C., Hou L., Hensch T.K., Frank E. Restoration of Visual Function by Enhancing Conduction in Regenerated Axons. Cell. 2016;164:219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y., Wang X., Li W., Zhang Q., Li Y., Zhang Z., Zhu J., Chen B., Williams P.R., Zhang Y. A Sensitized IGF1 Treatment Restores Corticospinal Axon-Dependent Functions. Neuron. 2017;95:817–833.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirai T., Enomoto M., Kaburagi H., Sotome S., Yoshida-Tanaka K., Ukegawa M., Kuwahara H., Yamamoto M., Tajiri M., Miyata H. Intrathecal AAV serotype 9-mediated delivery of shRNA against TRPV1 attenuates thermal hyperalgesia in a mouse model of peripheral nerve injury. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:409–419. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bey K., Ciron C., Dubreil L., Deniaud J., Ledevin M., Cristini J., Blouin V., Aubourg P., Colle M.A. Efficient CNS targeting in adult mice by intrathecal infusion of single-stranded AAV9-GFP for gene therapy of neurological disorders. Gene Ther. 2017;24:325–332. doi: 10.1038/gt.2017.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Brand R., Heutschi J., Barraud Q., DiGiovanna J., Bartholdi K., Huerlimann M., Friedli L., Vollenweider I., Moraud E.M., Duis S. Restoring voluntary control of locomotion after paralyzing spinal cord injury. Science. 2012;336:1182–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.1217416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courtine G., Song B., Roy R.R., Zhong H., Herrmann J.E., Ao Y., Qi J., Edgerton V.R., Sofroniew M.V. Recovery of supraspinal control of stepping via indirect propriospinal relay connections after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 2008;14:69–74. doi: 10.1038/nm1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson S.M., Eskenazi D., Ishikawa M., Wanat M.J., Phillips P.E., Dong Y., Roth B.L., Neumaier J.F. Transient neuronal inhibition reveals opposing roles of indirect and direct pathways in sensitization. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:22–24. doi: 10.1038/nn.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basso D.M., Fisher L.C., Anderson A.J., Jakeman L.B., McTigue D.M., Popovich P.G. Basso Mouse Scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J. Neurotrauma. 2006;23:635–659. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schucht P., Raineteau O., Schwab M.E., Fouad K. Anatomical correlates of locomotor recovery following dorsal and ventral lesions of the rat spinal cord. Exp. Neurol. 2002;176:143–153. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cantoria M.J., See P.A., Singh H., de Leon R.D. Adaptations in glutamate and glycine content within the lumbar spinal cord are associated with the generation of novel gait patterns in rats following neonatal spinal cord transection. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:18598–18605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3499-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Courtine G., Gerasimenko Y., van den Brand R., Yew A., Musienko P., Zhong H., Song B., Ao Y., Ichiyama R.M., Lavrov I. Transformation of nonfunctional spinal circuits into functional states after the loss of brain input. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:1333–1342. doi: 10.1038/nn.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichiyama R.M., Courtine G., Gerasimenko Y.P., Yang G.J., van den Brand R., Lavrov I.A., Zhong H., Roy R.R., Edgerton V.R. Step training reinforces specific spinal locomotor circuitry in adult spinal rats. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7370–7375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1881-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner F.B., Mignardot J.B., Le Goff-Mignardot C.G., Demesmaeker R., Komi S., Capogrosso M., Rowald A., Seáñez I., Caban M., Pirondini E. Targeted neurotechnology restores walking in humans with spinal cord injury. Nature. 2018;563:65–71. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wenger N., Moraud E.M., Gandar J., Musienko P., Capogrosso M., Baud L., Le Goff C.G., Barraud Q., Pavlova N., Dominici N. Spatiotemporal neuromodulation therapies engaging muscle synergies improve motor control after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 2016;22:138–145. doi: 10.1038/nm.4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerasimenko Y.P., Lavrov I.A., Courtine G., Ichiyama R.M., Dy C.J., Zhong H., Roy R.R., Edgerton V.R. Spinal cord reflexes induced by epidural spinal cord stimulation in normal awake rats. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2006;157:253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hofstoetter U.S., Danner S.M., Freundl B., Binder H., Mayr W., Rattay F., Minassian K. Periodic modulation of repetitively elicited monosynaptic reflexes of the human lumbosacral spinal cord. J. Neurophysiol. 2015;114:400–410. doi: 10.1152/jn.00136.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Capogrosso M., Wenger N., Raspopovic S., Musienko P., Beauparlant J., Bassi Luciani L., Courtine G., Micera S. A computational model for epidural electrical stimulation of spinal sensorimotor circuits. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:19326–19340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1688-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ladenbauer J., Minassian K., Hofstoetter U.S., Dimitrijevic M.R., Rattay F. Stimulation of the human lumbar spinal cord with implanted and surface electrodes: a computer simulation study. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2010;18:637–645. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2010.2054112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayers J.I., Fromholt S., Sinyavskaya O., Siemienski Z., Rosario A.M., Li A., Crosby K.W., Cruz P.E., DiNunno N.M., Janus C. Widespread and efficient transduction of spinal cord and brain following neonatal AAV injection and potential disease modifying effect in ALS mice. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:53–62. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dietz V. Proprioception and locomotor disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:781–790. doi: 10.1038/nrn939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roden-Reynolds D.C., Walker M.H., Wasserman C.R., Dean J.C. Hip proprioceptive feedback influences the control of mediolateral stability during human walking. J. Neurophysiol. 2015;114:2220–2229. doi: 10.1152/jn.00551.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeoka A. Proprioception: Bottom-up directive for motor recovery after spinal cord injury. Neurosci. Res. 2020;154:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J., Lanuza G.M., Britz O., Wang Z., Siembab V.C., Zhang Y., Velasquez T., Alvarez F.J., Frank E., Goulding M. V1 and v2b interneurons secure the alternating flexor-extensor motor activity mice require for limbed locomotion. Neuron. 2014;82:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dougherty K.J., Zagoraiou L., Satoh D., Rozani I., Doobar S., Arber S., Jessell T.M., Kiehn O. Locomotor rhythm generation linked to the output of spinal shox2 excitatory interneurons. Neuron. 2013;80:920–933. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torsney C., MacDermott A.B. Disinhibition opens the gate to pathological pain signaling in superficial neurokinin 1 receptor-expressing neurons in rat spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1833–1843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4584-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Todd A.J. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:823–836. doi: 10.1038/nrn2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asboth L., Friedli L., Beauparlant J., Martinez-Gonzalez C., Anil S., Rey E., Baud L., Pidpruzhnykova G., Anderson M.A., Shkorbatova P. Cortico-reticulo-spinal circuit reorganization enables functional recovery after severe spinal cord contusion. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:576–588. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang H.Y., Sharma H.S., Chen L., Otom A., Al Zoubi Z.M., Saberi H., Muresanu D.F., He X.J. Review of clinical neurorestorative strategies for spinal cord injury: Exploring history and latest progresses. Journal of Neurorestoratology. 2018;6:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Njoo C., Heinl C., Kuner R. In vivo SiRNA transfection and gene knockdown in spinal cord via rapid noninvasive lumbar intrathecal injections in mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2014;85:51229. doi: 10.3791/51229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zörner B., Filli L., Starkey M.L., Gonzenbach R., Kasper H., Röthlisberger M., Bolliger M., Schwab M.E. Profiling locomotor recovery: comprehensive quantification of impairments after CNS damage in rodents. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:701–708. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearson K.G., Acharya H., Fouad K. A new electrode configuration for recording electromyographic activity in behaving mice. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2005;148:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Esposito M.S., Capelli P., Arber S. Brainstem nucleus MdV mediates skilled forelimb motor tasks. Nature. 2014;508:351–356. doi: 10.1038/nature13023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao Z., Min C., Xie H., Qin J., He X., Zhou S. TNFR2 knockdown triggers apoptosis-induced proliferation in primarily cultured Schwann cells. Neurosci. Res. 2020;150:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.