Abstract

Objectives

The arts therapies include music therapy, dance movement therapy, art therapy and dramatherapy. Preferences for art forms may play an important role in engagement with treatment. This survey was an initial exploration of who is interested in group arts therapies, what they would choose and why.

Design

An online cross-sectional survey of demographics, interest in and preferences for the arts therapies was designed in collaboration with patients. The survey took 10 min to complete, including informed consent and 14 main questions. Summary statistics, multinomial logistic regression and thematic analysis were used to analyse the data.

Setting

Thirteen National Health Service mental health trusts in the UK asked mental health patients and members of the general population to participate.

Participants

A total of 1541 participants completed the survey; 685 mental health patients and 856 members of the general population. All participants were over 18 years old, had capacity to give informed consent and sufficient understanding of English. Mental health patients had to be using secondary mental health services.

Results

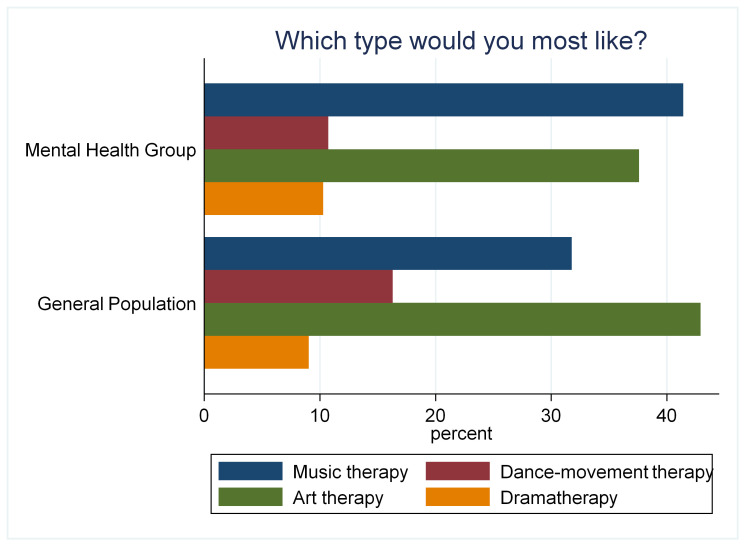

Approximately 60% of participants would be interested in taking part in group arts therapies. Music therapy was the most frequent choice among mental health patients (41%) and art therapy was the most frequent choice in the general population (43%). Past experience of arts therapies was the most important predictor of preference for that same modality. Expectations of enjoyment, helpfulness, feeling capable, impact on mood and social interaction were most often reported as reasons for preferring one form of arts therapy.

Conclusions

Large proportions of the participants expressed an interest in group arts therapies. This may justify the wide provision of arts therapies and the offer of more than one modality to interested patients. It also highlights key considerations for assessment of preferences in the arts therapies as part of shared decision-making.

Keywords: adult psychiatry, psychiatry, depression & mood disorders, schizophrenia & psychotic disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest survey of the arts therapies to date, and the only survey relating to preferences for the arts therapies.

The survey’s simple format made it accessible and recruitment was able to continue during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The sampling technique may have led to some biases in the data.

The survey results give insight into preferences when there were no consequences, future research should examine what patients choose when they are offered arts therapies as a treatment.

Introduction

The arts therapies is an umbrella term encompassing art therapy, music therapy, drama therapy and dance movement therapy. They are a group of psychotherapeutic interventions which make use of specific art forms. In the UK and several other countries, the arts therapies are delivered by qualified and regulated therapists, who draw on a number of different theoretical frameworks including psychodynamic, humanistic, attachment and person-centred approaches.1 There is a focus on the therapeutic relationship and exploration of the patient’s feelings and experiences through active engagement with the art form.2 In a session, interactions are usually spontaneous, with the therapist responding to the feelings and reflections which arise in the moment. There are many different ways to use the creative art forms, although improvisation and playfulness are usually encouraged and supported.3 The primarily non-verbal approach makes the arts therapies suitable to work with patients who find verbal interaction difficult, such as those with learning disabilities, dementia or severe mental illness.4 Arts therapists work across many different settings, including as part of an arts therapies service, a multidisciplinary team or as lone workers, and provide treatment both individually and in groups.5 In individual work, the therapeutic relationship between the therapist and the patient is key; in groups, there is also an emphasis on supporting healthy interactions between group members.6 Mental health services in the UK often offer arts therapies in a group format as the experience of being in a group is well understood to be helpful for people with severe mental illness.7 8 In groups, the art forms offer a way for group members to connect with each other and the therapist on a non-verbal level.5 6 9

Potential participants in the arts therapies will likely have had past experiences of the creative arts, whether that was at school or as hobbies.10 Therefore, their preferences and expectations may play a considerable role in their engagement and the success of therapy.11–13 Although the arts therapies share many features, including theoretical underpinning, there is a clear difference in the art form being used. In music therapy, there are usually instruments to play, and patients may be encouraged to take part in singing, song writing, listening or musical improvisation. Art therapists provide a space where patients can explore different art materials, including, but not limited to, drawing, collage, model making or painting. In drama therapy, there may be opportunities to explore storytelling or role-play using acting or puppets. In dance movement therapy, patients would be encouraged to move their bodies, often to music, making use of props like scarves or ribbons.4

The arts therapies have been around since the 1940s but until recently each arts modality has been considered distinct.14 An increased understanding of common factors in therapies has helped to conceptualise aspects that the arts therapies share, as well as differences between them.15–17 Historically, trials investigating the effectiveness of arts therapies have been small in number and poor in quality.18–26 When there is little evidence to distinguish the benefits or harms between treatment, it is recommended that treatment decisions are guided by patient preferences.27

Mental health patients’ retrospective attitudes towards the arts therapies have been investigated by some; Heaney28 surveyed the psychiatric inpatients about their experiences of treatment, focusing on arts therapies. The participants rated all of the therapies as favourable, with music therapy coming out top of being ‘pleasurable’. All of the ‘activity therapies’ (music, art and recreation) in the study were considered to be of equal importance to other aspects of care.28 Silverman29 interviewed 15 inpatients about their perceptions of music therapy after they had attended sessions. Their feedback indicated a positive perception of their experiences and that they were able to recall the features of the session.29 In a metasynthesis of 14 studies of patient experiences of music therapy, it was found that there were four main areas which patients reported to be important: ‘having a good time’, ‘being together’, ‘feeling’ and ‘being someone’.30 More recently, Haeyen and colleagues surveyed the patients with a diagnosis of personality disorder who had attended art therapy. They found five key categories of experiences: expression of emotions, improved self-image, making own choices/autonomy, insight and changing of personal patterns, and dealing with own limitations.31 This research into experiences offers understanding of patient values, and has potential to be associated with preferences and expectations for engagement with arts therapies.

No research to date has looked at who would be interested in taking part in group arts therapies, what their preferences would be and why. Given that preferences have been found to play an important role in engagement with psychosocial treatments, and the potential for the arts therapies to offer a space where patients can make choices and be autonomous, it seems pertinent to initiate a discussion about preferences in the arts therapies.

The current study was designed as an initial exploration of this topic. The research questions were:

Who is interested in participating in group arts therapies?

Which of the four arts modalities would people most like to take part in and why?

Which sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are related to preferences?

Method

This study is reported according to recommended survey guidelines.32

Participants

All participants were required to be aged 18 or over, with sufficient command of the English language and capacity to give informed consent.

National Health Service (NHS) mental health trust sites became involved via the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network. Researchers at each site approached mental health group participants in secondary mental health services, such as inpatient wards and community mental health teams, to ask if they would like to take part. Researchers could ask any other member of the public to complete the general population group survey, including family members and colleagues. Numbers of people who declined to take part were not recorded.

Patient and public involvement

The survey questions were developed in collaboration with patients and members of a multidisciplinary research team. A draft of the analysis was read and commented on by the multidisciplinary research team. Published results will be sent to the study sites to disseminate among their participants.

The survey

The survey was created by the authors; a validated survey was not available as this is the first time the topic has been researched. The questions were developed based on topics of interest in collaboration with service users and a multidisciplinary research team (see online supplemental appendices A and B for full surveys). Piloting of the survey was undertaken within the research team to ensure usability of the survey software, and with mental health patients and the general population in the main study site (n=200). No changes were required before expansion to further sites.

bmjopen-2021-051173supp001.pdf (1MB, pdf)

The survey was completed electronically, in person via an iPad, or on participants’ own devices while speaking to a researcher on the phone, and took approximately 10 min. The researchers were instructed to be present for the completion of the survey when possible, especially for mental health participants. There were 14 questions in the survey which focused on the participants’ demographic characteristics and whether they had heard of the arts therapies, whether they would be interested in taking part and which modality they would choose and why (as an open response). A short description of the arts therapies was included in the survey.

Mental health patients gave the researcher permission to access to their medical records to look for their diagnosis and length of time in services. Length of time in services was determined from the first clinical record on the patient’s profile, or from self-reported first contact with mental health services. All responses were collected via an online platform, and researchers collected identifiable information (date of birth, diagnosis and time in services) for the mental health patients on a spreadsheet. This was anonymised and emailed to EMi monthly, where the information was linked up to the online responses via a unique ID number.

Participants were given the chance to enter a £50 prize draw. They gave their personal information on a separate spreadsheet (mental health patients) or followed a link to a separate survey (general population) so that the survey responses remained anonymous.

Data analysis

All quantitative analyses were conducted in Stata V.15.33 Age groups, gender, ethnicity, level of education and time in services were collapsed into dichotomous variables. Summary statistics were used to look at the characteristics of participants. Χ2 tests were conducted to look at differences between participant groups and to find variables of interest. These were entered into a multinomial logistic regression to look for significant characteristics related to interest in participating in the arts therapies, participants’ preferred arts therapy modality and the reasons they gave for their preferences. This was done first with all data together, then separately for each group of participants (mental health patients and general population). Missing data were excluded from analysis.

A subsample of reasons for preferences were coded and grouped into themes by EMi using NVivo V.12.34 These themes were then used as a framework to group together the remaining responses (EMi, EMe and JC coded 33% each of all the open responses).

Results

The total number of participants was 1541. Online supplemental appendix C details the sample characteristics as broken down for analysis. There were some differences between the two groups, with a larger sample in the general population group (n=856) than in the mental health group (n=685). A significantly larger proportion of the general population were female (68%) and under 45 years old (62%) than in the mental health sample (49% female, 51% under 45). A significantly higher number of people in the general population were university educated (71%) than in the mental health sample (30%). A greater proportion of people in the mental health group had received talking therapies (74% vs 45%). Higher numbers of people in the mental health group (42%) had attended arts therapies in the past than in the general population (12%). Levels of missing data were low for variables of interest (between 1% and 2%).

Overall, 61.4% and 59.5%, respectively, of participants in the mental health group and the general population were interested in taking part in group arts therapies (see table 1). The first regression model (see online supplemental appendix D) showed significant associations between interest in participating in the arts therapies and gender (p<0.001), and previous attendance of arts therapies (p<0.001): females were more likely than males to say they were interested in attending, as were those who had attended arts therapies before. Participants who had attended before were also less likely to say they were not sure.

Table 1.

Attendance and interest

| Question | Response | Mental health patients (n=685) |

General population sample (n=856) |

Total (n=1541) |

| Have you attended music therapy?* | Yes | 117 (17.08%) | 44 (5.14%) | 161 (10.45%) |

| Have you attended dance movement therapy?* | Yes | 59 (8.61%) | 24 (2.8%) | 83 (5.39%) |

| Have you attended art therapy?* | Yes | 230 (33.58%) | 57 (6.66%) | 287 (18.62%) |

| Have you attended drama therapy?* | Yes | 54 (7.88%) | 25 (2.92%) | 79 (5.13%) |

| Attended none* | Yes | 398 (58.1%) | 755 (88.2%) | 1153 (74.82%) |

| Would you be interested in taking part in group arts therapies? | Yes | 420 (61.4%) | 509 (59.53%) | 929 (60.36%) |

| No | 165 (24.12%) | 179 (20.94%) | 344 (22.35%) | |

| Not sure | 99 (14.47%) | 167 (19.53%) | 266 (17.28%) |

*Significant differences between groups—χ2 at 5%.

For the mental health patients, gender (p=0.05), education level (p=0.01), diagnosis (p=0.02) and previous attendance of an arts therapy (p<0.001) were significant variables: females and people who had attended before were more likely to say that they were interested, those with a diagnosis of F2 or who were not university educated were more likely to say they were not interested in participating.

In the general population sample, gender (p=0.01), having heard of the arts therapies (p=0.03) and attended the arts therapies (p=0.02) were significant variables. Females and people who had heard of the arts therapies and attended arts therapies were more likely to say that they were interested. Those who had not attended were more likely to say they were not sure.

Participants were asked to choose one of the four modalities that they would most like to attend.

Table 2 shows a summary of the responses, and figure 1 gives a graphical representation of the differences between groups.

Table 2.

Most preferred modality of arts therapies

| Question | Mental health patients (n=685) |

General population sample (n=856) |

Total (n=1541) |

|

| Which type would you most like? | Music therapy | 282 (41.41%) | 271 (31.77%) | 553 (36.05%) |

| Dance movement therapy | 73 (10.72%) | 139 (16.3%) | 212 (13.82%) | |

| Art therapy | 256 (37.59%) | 366 (42.91%) | 622 (40.55%) | |

| Drama therapy | 70 (10.28%) | 77 (9.03%) | 147 (9.58%) |

Figure 1.

Most preferred modality of arts therapies divided by participant group.

When both groups were combined in the regression model (online supplemental appendix E), participant group (p=0.02), gender (p<0.001), previous attendance of music therapy (p<0.001), dance movement therapy (p=0.002), art therapy (p<0.001) and drama therapy (p=0.002) were all significantly associated with the most preferred arts therapy modality. Significant variables for the mental health patients were gender (p<0.001), whether someone was White British, or black, Asian and minority ethnic (p=0.05) and previous attendance of music therapy (p<0.001), dance movement therapy (p=0.02), art therapy (p<0.001) and drama therapy (p=0.01). Significant variables for the general population sample were gender (p<0.001) and previous attendance of music therapy (p=0.01), dance movement therapy (p=0.02), art therapy (p=0.01) and drama therapy (p=0.02). Significant characteristics for each modality are summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Significant characteristics for preferences

| Most preferred type | Most likely characteristics—both groups combined | Most likely characteristics—mental health patients | Most likely characteristics—general population sample |

| Music therapy |

|

|

|

| Dance movement therapy |

|

|

|

| Art therapy |

|

|

|

| Drama therapy |

|

|

|

BAME, black, Asian and minority ethnic.

Reasons for preferences

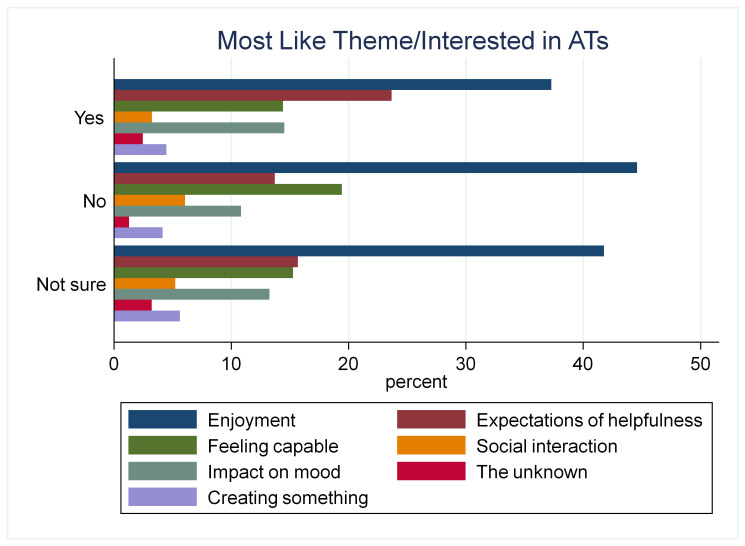

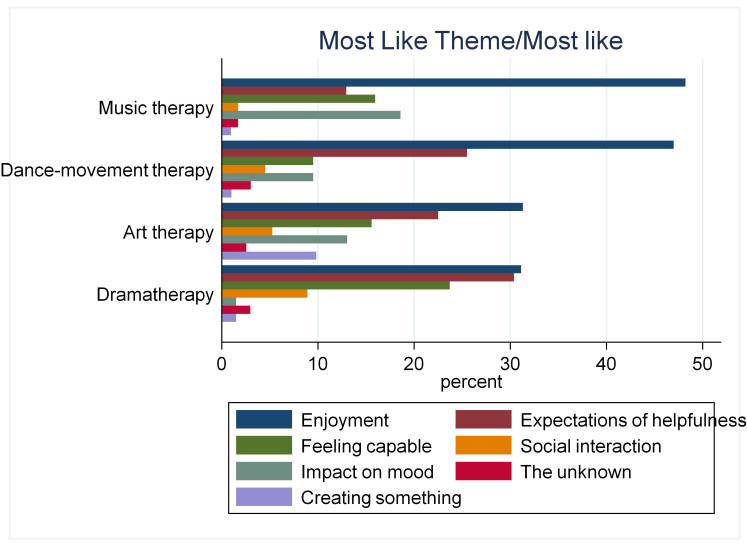

Participants were asked why they had chosen their most preferred arts modality with an open response box. These answers were grouped into seven main themes: enjoyment, expectations of helpfulness, feeling capable, impact on mood, creating something, social interaction and the unknown (see table 4 for counts).

Table 4.

Counts of themes

| Theme | Most like | |

| n | % | |

| Enjoyment | 578 | 38.05 |

| Expectations of helpfulness | 294 | 19.35 |

| Feeling capable | 228 | 15.01 |

| Impact on mood | 197 | 12.97 |

| Creating something | 67 | 4.41 |

| Social interaction | 61 | 4.02 |

| The unknown | 34 | 2.24 |

These themes were also entered into a regression model to look for associations between the reasons participants gave for their preferences and their characteristics. The regression model with all categories was not a good fit because of low numbers in some of the categories. In order to create a good fit, the four categories which had the fewest responses were grouped together and named ‘other’. In the bar charts, the results were kept in their original, wider categories.

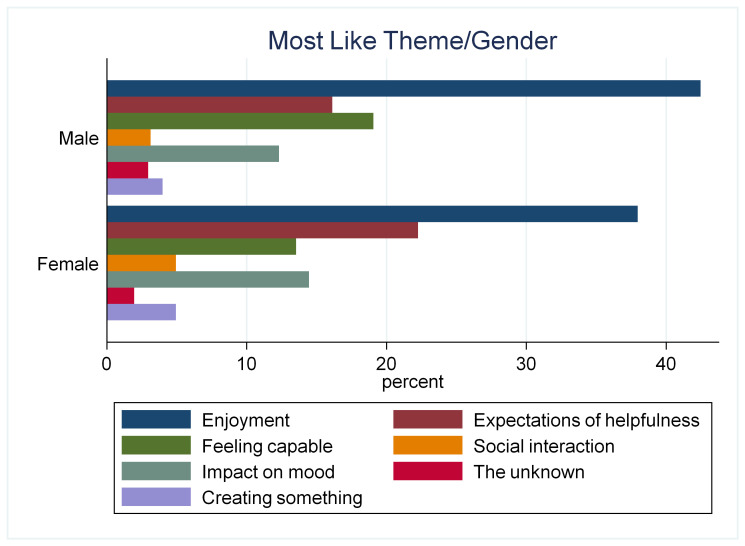

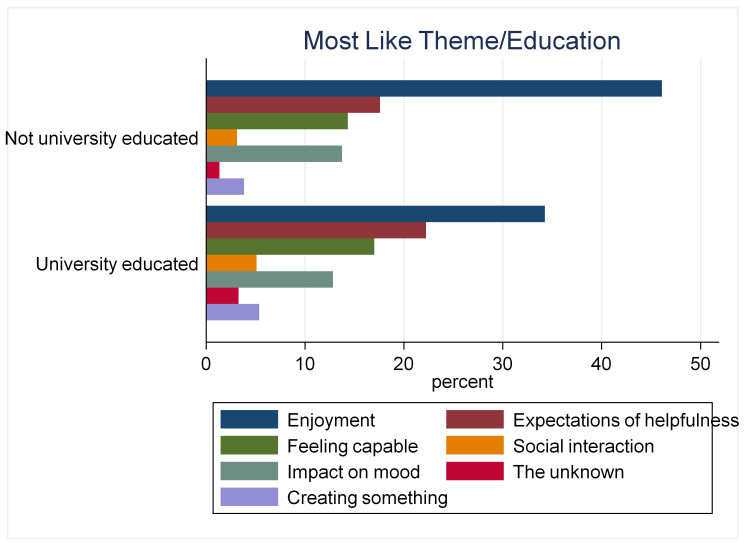

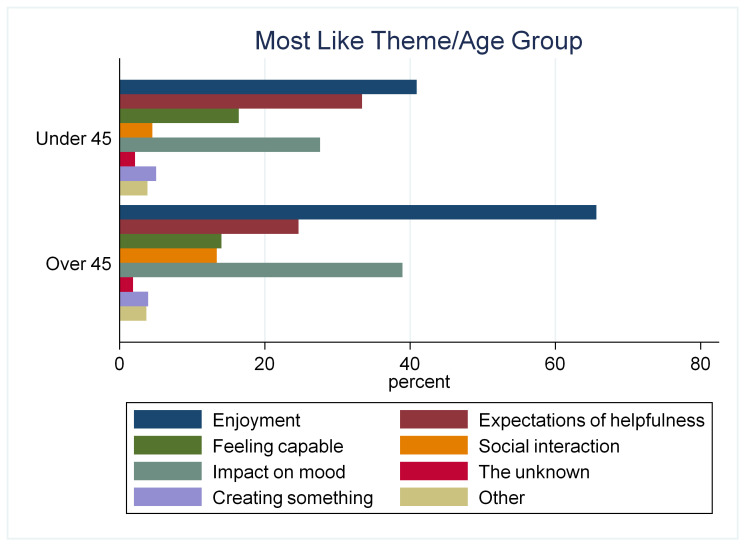

The regression model (online supplemental appendix F) for the reasons given by the full sample showed that gender (p=0.05) (figure 2), level of education (p<0.001) (figure 3), age group (p=0.004) (figure 4), interest in taking part (p=0.01) (figure 5) and most preferred modality (p<0.001) (figure 6) were significant factors. When the mental health group and the general population were analysed separately, their most preferred modality (p<0.001) was the only variable significantly associated with the reason given for this.

Figure 2.

Bar chart of association between reason given and gender.

Figure 3.

Bar chart of association between reason given and level of education.

Figure 4.

Bar chart of association between reason given and age group.

Figure 5.

Bar chart of association between reason given and interest in participating in group arts therapies (ATs).

Figure 6.

Bar chart of association between reason given and most preferred modality.

Themes

Enjoyment

Enjoyment and pleasure were mentioned often. Participants sometimes related their enjoyment of the art form to previous experiences such as at school or using the art forms as hobbies. Many people said they had a personal interest in an art form and that is why they would choose it. They expected that using the art form would be fun.

I like to make music and have a studio at home. (Ppt0045: Music therapy)

Done it before and enjoyed it, benefited from it. (Ppt0303: Art therapy)

Expectations of helpfulness

Participants often gave a reason related to how helpful they expected that art modality to be for them. This was sometimes due to the therapeutic benefit they thought they may gain from using that art form, as well as being able to use the art form to express themselves.

Exercise and movement help with my depression. (Ppt0270: Dance movement therapy)

Because I know that when you draw/paint, you are in touch with a childlike part of yourself. Therefore I think it could be useful, particularly in conjunction with talking about the problem. Art taps into unconscious processes. (Ppt0767: Art therapy)

Feeling capable

Some people preferred an art modality because they felt that they were good at it, possibly because of past experience or a natural talent. Others said they would feel more comfortable using an art form because they believed there was no need to be good at it.

I think I’d make a good actor. (Ppt0224: Drama therapy)

Because it’s something anyone can do with any skill level. No judgement, it’s what you feel and what drives you to put down on paper. For me it settles my head and evens me out. (Ppt0620: Art therapy)

Impact on mood

Participants spoke about how an art form may be relaxing for them or that it cheers them up. This was expected to be through different methods of engaging with the art form, including listening to calming music, the benefits of doing exercise or just the joy of being creative.

Because of the interaction, when you listen to music your mood improves as well. You get better. When you listen to different types of music your moods gets better all the time too. (Ppt0295: Music therapy)

Dance would relax me and help to maintain fitness. (Ppt1300: Dance movement therapy)

Creating something

The theme of creating something encapsulated when participants said that the creativity, or producing something, would draw them to a modality. This was most often mentioned in relation to art therapy.

I enjoy the quite methodical work that goes into producing a piece of artwork and having a visual representation to have and keep. (Ppt1330: Art therapy)

I like the thought of being creative and making things. (Ppt1410: Art therapy)

Social interaction

Some participants said that they would choose their preferred modality because it would give them a chance to be with others and socialise. It seemed that art therapy was considered a less ‘sociable’ modality, as each person works on their own piece of art; this was a positive thing for many people.

I believe it would involve the greatest amount of independent working without interaction with others. (Ppt0788: Art therapy)

I think because I’m expressive, I’m comfortable in front of other people and being able to be silly boosts your self-esteem and is good for my mental health. (Ppt1206: Drama therapy)

The unknown

Participants gave ‘not knowing’ about a modality as a reason for why they might like to take part. For example, some said they would like to try it as it was something new, or that they would like to learn a new skill.

Sounds relaxing and something that I have never done before and the other three are my hobbies already. Would like to get better at art. (Ppt1124: Art therapy)

Never learnt an instrument and would want to muck around within one. (Ppt1130: Music therapy)

In summary of the bar charts, it seems that males are more likely to place value on enjoyment and feeling capable than females, whereas females are more likely to speak about expectations of helpfulness than males when giving reasons for their preferences. Those who were not university educated, and people over the age of 45 put more emphasis on enjoyment than others. Enjoyment and impact on mood were more commonly mentioned for music therapy than for the other modalities, whereas expectations of helpfulness seemed more relevant for people who chose dance movement or drama therapy. Feeling capable was a key consideration for people who chose drama therapy as their preferred modality, and creating something was more important for those who chose art therapy than the other modalities.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest survey of the arts therapies ever undertaken. The results show who would be interested in group arts therapies, what they would want and why. A relatively high proportion of people both in mental health services and in the general population would be interested in participating (around 60%). However, when looking at the proportion of those using mental health services who had accessed arts therapies, this number was much lower (42%). Receiving a preferred psychosocial treatment is associated with lower dropout rates,11 and the results of this survey suggest that there is the potential for arts therapies to be more widely offered, to increase engagement with treatment. It is unknown how many trusts in the UK provide an arts therapies service, but of the sites in this survey the number was 4 out of 13 (31%). This may not be representative of provision of arts therapies across the UK. We would recommend that research is conducted to ascertain this information.

The results indicate that preferences in the survey were heavily informed by past experiences of using that art form. The most consistent and clinically relevant predictors of preferences were previous experiences of the same type of arts therapy. A conceptual review of resource-oriented therapeutic models in psychiatry highlighted how using the experiences and knowledge of the patient, in particular to identify what has helped them in the past, is a key component of solution-focused therapy.35 This suggests that an understanding of patients’ past experiences of the arts should form an integral part of the shared decision-making process.11

Art and music therapies were the most preferred modalities overall. There are a number of potential explanations for this, other than them being truly more popular. Although we do not know the actual provision of arts therapies in mental health services, far more people in the survey had heard of and attended art therapy and music therapy than the other two modalities. As demonstrated by the regression model, those who have attended a modality before are more likely to choose it as their preference; this held true for every modality and both participant groups. Therefore, the lower numbers of people choosing dance movement and drama therapies could be due to the lower availability of these modalities. It could also be argued that music and art are more ‘mainstream’ art forms, which most people use in their day-to-day lives and therefore feel more comfortable with.

Another potential reason for this split is a misunderstanding of the implications of taking part in dance movement and drama therapies. Zajonc suggests that people are able to express preferences based on very limited information, by adhering to their past experiences and set of values,36 and many participants spoke about their past experiences of the arts, such as at school or as hobbies. Participants in this questionnaire were not informed about what the arts therapies involve, and the open responses highlighted some misconceptions. This underlines the need for clinicians to address concerns during informed decision-making processes.

In line with the proposed common active factors, this survey found that pleasure and enjoyment are important for preferences for arts therapies.37 It has been suggested that people making non-consequential decisions will do so on the basis of mental pleasure, or to minimise mental displeasure.38 In the arts therapies, pleasure and playfulness may be more important than in other forms of therapy,2 as there is an emphasis on using creativity to explore different cognitive or emotional experiences.15 31 Fun and enjoyment are also mentioned as factors in qualitative studies of patient experiences of arts therapies.39 40

It was important to participants to consider how the art form might be helpful for them, such as being inherently therapeutic, or a way to express themselves. This is in line with literature on the construction of preferences; people consider the pros and cons of the options and how they may benefit from them.41 Expectations of how a therapy might be helpful also play a crucial role in engagement and process.12 Patients and therapists must believe that the therapy will help them in order to make positive change.16

Other reasons for preferences revolved around an impact on mood. In previous studies, changes in mood have been highlighted as key outcomes for people who attend the arts therapies19 42–44 and this seemed particularly important for people who chose music therapy as their preference. Social interaction was also an important consideration for participants in the survey.15 Being together in a group has been found to be a key mechanism of change for patients attending music therapy,30 39 therefore consideration of the group dynamics is pertinent.

It is essential to remember that any decisions about engagement with the arts therapies should be made in collaboration with a healthcare professional, within the context of a shared decision-making approach.45 46 The reasons which participants gave in this study point towards the aspects of arts therapies treatment which could influence their preferences. Although past experiences are a key consideration, it may be appropriate to encourage a patient to try something new, depending on their situation. The healthcare professional should be prepared to state the aims and goals of the arts therapies so that patients have more information than only their own past experiences. Decision aids, including taster sessions, for the arts therapies could be helpful in supporting patients to make an informed choice.10

Strengths and limitations

The simplicity of the survey meant it was popular with NHS sites and online access meant recruitment was able to continue during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the study was the first of its kind, the approach was exploratory and a sample size calculation was not deemed appropriate. The sampling technique may have led to some bias, and there were some significant differences between participant groups (mental health patients and general population). Researchers asked people in their own networks for the general population sample. This is likely to be the cause of the high levels of education seen in the general population sample and potentially higher numbers of female participants, as many were employed by the mental health service involved in the study (27% of general population participants). It was necessary to recruit participants in this way for pragmatic reasons, however, ideally the general population sample would be more representative. We also did not ask the general population sample whether they were mental health patients, so the groups may not have been mutually exclusive, which is a limitation of the study. In multivariable analysis, it is recommended that the sample size should be at least 10 times the number of variables considered47; this was the case with our sample, suggesting that the associations are reliable.

Reasons for liking something can be difficult to verbalise36 and participants in the current study sometimes gave limited responses to the open questions. This could have been influenced by the short nature of the survey and the environment in which it was being answered, for example, in a waiting room or shopping centre, or over the phone. A more in-depth understanding of the choices that participants made could be ascertained through individual interviews. If this research were to be conducted, the themes drawn out from the open questions in this study could provide a framework for topic guides. This survey focused on group arts therapies, whereas the results may have been different for individual therapy. There could be scope for linking these reasons for preferences to personality characteristics such as openness and extraversion48; however, this was not within the remit of this study. In hindsight, it would have been interesting to know whether participants’ past experiences of the arts therapies were in groups or individually; however, this question was not included in the survey because it did not seem relevant to the research question at the time.

Given the large number of tests conducted in this study, it would be expected that 5% of the significant results were due to chance, as they were not corrected for multiple testing. It is also important to consider the difference between statistical significance and clinical relevance. Many of the associations found in this study will not highlight clinically relevant findings. To account for this, significant associations have not been given undue weight and the most relevant to clinical contexts have been explored further.

Zaller and Feldman suggested that survey responses seem to be random and not necessarily linked to participants’ preferences.49 In the current study, participants were ‘forced’ to choose one modality as their preference. There was no option to say ‘none’ or ‘all’. This may have created an unrealistic representation of true preferences. Participants were aware that there were no consequences to their preferences; they would not have to participate in the groups. They were also not given any information about the arts therapies, other than one sentence embedded in the survey. If someone was expressing a preference as part of their treatment pathway, they would be given more information.10 They would also be given more time to think about their decision and discuss with a mental health professional as part of a shared decision-making process.50 Therefore, the responses in this survey may not translate into actual behaviour. Future research should focus on ‘real life’ preferences of those who are taking part in the arts therapies and whether preferences and expectations are associated with engagement.

Conclusion

This is the first study to investigate who would be interested in taking part in group arts therapies and what their preferences would be. Two-thirds of participants said they would be interested in participating. Relevant characteristics for interest and preferences were varied, but previous experience of the arts therapies was consistently associated with a preference for the same modality. The findings may justify the wide provision of arts therapies and the offer of more than one modality to interested patients. They also highlight key topics to consider when supporting people to make informed decisions about engaging with the arts therapies as part of a shared decision-making process.

We would recommend that further research is undertaken to ascertain the current provision of arts therapies in mental health services in the UK, as well as a more in-depth understanding of the impact of preferences on engagement with arts therapies in both research and clinical settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

With thanks to the ERA Study Lived Experience Advisory Panel for their advice, and all NHS trusts involved: Barnet, Enfield and Haringey, Camden and Islington, Cornwall Partnership, Devon Partnership, ELFT, Lancashire Care, Mersey Care, NELFT, North West Boroughs, Oxford Health, Somerset Partnership, Southern Health and West London.

Footnotes

Twitter: @EmmaM1llard, @catherinecarrMT

Contributors: The study was planned and designed by EMi, CC and SP. Data collection was conducted by EMi and researchers at each NHS site. Data preparation and analysis was undertaken by EMi, EMe and JC. Write-up and editing was undertaken by all authors, with EMi taking the lead.

Funding: This work was funded by East London NHS Foundation Trust as part of a PhD studentship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Unpublished, anonymised data would be made available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was given ethical approval by the South Central Oxford C Research Ethics Committee (18/SC/0701).

References

- 1.Karkou V, Sanderson P. Arts therapies: a research-based map of the field. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cattanach A. Process in the arts therapies. London: Jessica Kingsley, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones P. The arts therapies: a revolution in healthcare. 2nd ed. Oxon: Routledge, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odell-Miller H, Hughes P, Westacott M. An investigation into the effectiveness of the arts therapies for adults with continuing mental health problems. Psychotherapy Research 2006;16:122–39. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones P. The arts therapies: a revolution in healthcare. 2nd edn. Oxon: Routledge, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies A, Richards E, Barwick N. Group music therapy: a group analytic approach. London: Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foulkes SH, Pines M. Selected papers: psychoanalysis and group analysis. London: H. Karnac (Books) Ltd, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bion WR. Experiences in groups. Hum Relat 1948;1:314–20. 10.1177/001872674800100303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr C, Feldtkeller B, French J. What makes us the same? What makes us different? Development of a shared model and manual of group therapy practiceacross art therapy, dance movement therapy and music therapy within community mentalhealth care. The Arts in Psychotherapy 2020;101747. 10.1016/j.aip.2020.101747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millard E, Hounsell L, Fernandes J, et al. How do you know what you want? service user views on decision aids for the arts therapies. Arts Psychother 2021;73:101757. 10.1016/j.aip.2021.101757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Windle E, Tee H, Sabitova A, et al. Association of patient treatment preference with dropout and clinical outcomes in adult psychosocial mental health interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77:1–9. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnkoff DB, Glass CR, Shapiro SJ. Expectations and preferences. In: Norcross JC, ed. Psychotherapy: theory, research, practice, training. Oxford University Press, 2002: 335–56. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swift JK, Callahan JL, Cooper M, et al. The impact of accommodating client preference in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 2018;74:1924–37http://doi.wiley.com/ 10.1002/jclp.22680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogan S. Healing arts: the history of art therapy. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr C, Feldtkeller B, French J. What makes us the same? what makes us different? development of a shared model and manual of group therapy practice across art therapy, dance movement therapy and music therapy within community mental health care. The Arts in Psychotherapy 2020. 10.1016/j.aip.2020.101747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wampold B, Imel ZE. The great psychotherapy debate. 2nd edn. New York: Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priebe S, Conneely M, McCabe R. What can clinicians do to improve outcomes across psychiatric treatments: a conceptual review of non-specific components. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 2019:1–8. 10.1017/s2045796019000428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker FA, Metcalf O, Varker T, et al. A systematic review of the efficacy of creative arts therapies in the treatment of adults with PTSD. Psychol Trauma 2018;10:643–51. 10.1037/tra0000353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aalbers S, Fusar-Poli L, Freeman RE, et al. Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;11:CD004517. 10.1002/14651858.CD004517.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geretsegger M, Mössler KA, Bieleninik Łucja, Ka M, Xj C, et al. Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;5:CD004025. 10.1002/14651858.CD004025.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deshmukh SR, Holmes J, Cardno A, et al. Art therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;2018. 10.1002/14651858.CD011073.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruddy R, Milnes D, Cochrane Schizophrenia Group . Art therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;23:4–6. 10.1002/14651858.CD003728.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meekums B, Karkou V, Ea N. Dance movement therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016. 10.1002/14651858.CD009895.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren J, Xia J, Cochrane Schizophrenia Group . Dance therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;36:10–12. 10.1002/14651858.CD006868.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karkou V, Meekums B, Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group . Dance movement therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;36. 10.1002/14651858.CD011022.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruddy R, Dent-Brown K, Cochrane Schizophrenia Group . Drama therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;40. 10.1002/14651858.CD005378.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ 2007;335:24–7. 10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heaney CJ. Evaluation of music therapy and other treatment modalities by adult psychiatric inpatients. J Music Ther 1992;29:70–86. 10.1093/jmt/29.2.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverman MJ. Perceptions of music therapy interventions from inpatients with severe mental illness: a mixed-methods approach. Arts in Psychotherapy 2010;37:264–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solli HP, Rolvsjord R, Borg M. Toward understanding music therapy as a recovery-oriented practice within mental health care: a meta-synthesis of service users' experiences. J Music Ther 2013;50:244–73. 10.1093/jmt/50.4.244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haeyen S, Chakhssi F, van Hooren S. Benefits of art therapy in people diagnosed with personality disorders: a quantitative survey. Frontiers in Psychology 2020;11:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, et al. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care 2003;15:261–6. 10.1093/intqhc/mzg031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.StataCorp . Stata statistical software. College Station. TX: StataCorp LLC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.QSR International Pty Ltd . NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Version 12. 2018.

- 35.Priebe S, Omer S, Giacco D, et al. Resource-oriented therapeutic models in psychiatry: conceptual review. Br J Psychiatry 2014;204:256–61. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.135038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zajonc R. Feeling and thinking preferences need no inference. American Psychologist 1980;35:151–75. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koch SC. Arts and health: active factors and a theory framework of embodied aesthetics. Arts Psychother 2017;54:85–91. 10.1016/j.aip.2017.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cabanac M, Guillaume J, Balasko M, et al. Pleasure in decision-making situations. BMC Psychiatry 2002;2:1–15. 10.1186/1471-244X-2-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Windle E, Hickling LM, Jayacodi S. The experiences of patients in the synchrony group music therapy trial for long-term depression. The Arts in Psychotherapy 2019;67. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brady C, Moss H, Kelly BD. A fuller picture: evaluating an art therapy programme in a multidisciplinary mental health service 2017:30–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Slovic P. The construction of preference. American Psychologist 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Petrillo L, Winner E. Does art improve mood? A test of a key assumption underlying art therapy. Art Therapy 2005;22:205–12. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKinney CH, Honig TJ. Health outcomes of a series of bonny method of guided imagery and music sessions: A systematic review. J Music Ther 2017;54:1–34. 10.1093/jmt/thw016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bell CE, Robbins SJ. Effect of art production on negative mood: a randomized, controlled trial. Art Therapy 2007;24:71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edwards A, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2009. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.qmul.ac.uk/lib/gmul-ebooks/reader.action?docID=975640# [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slade M. Implementing shared decision making in routine mental health care. World Psychiatry 2017;16:146–53. 10.1002/wps.20412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sekaran U, Bougie R. Research methods for business. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaplan SC, Levinson CA, Rodebaugh TL, et al. Social anxiety and the big five personality traits: the interactive relationship of trust and openness. Cogn Behav Ther 2015;44:212–22. 10.1080/16506073.2015.1008032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zaller J, Feldman S. A simple theory of the survey response: answering questions versus revealing preferences. Am J Pol Sci 1992;36:579–616. 10.2307/2111583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duncan E, Best C, Hagen S, et al. Shared decision making interventions for people with mental health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;68. 10.1002/14651858.CD007297.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-051173supp001.pdf (1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Unpublished, anonymised data would be made available upon reasonable request.