Summary

In every organism, the cell cycle requires the execution of multiple processes in a strictly defined order. However, the mechanisms used to ensure such order remain poorly understood, particularly in bacteria. Here, we show that the activation of the essential CtrA signaling pathway that triggers cell division in Caulobacter crescentus is intrinsically coupled to the initiation of DNA replication via the physical translocation of a newly-replicated chromosome, powered by the ParABS system. We demonstrate that ParA accumulation at the new cell pole during chromosome segregation recruits ChpT, an intermediate component of the CtrA signaling pathway. ChpT is normally restricted from accessing the selective PopZ polar microdomain until the new chromosome and ParA arrive. Consequently, any disruption to DNA replication initiation prevents ChpT polarization and, in turn, cell division. Collectively, our findings reveal how major cell-cycle events are coordinated in Caulobacter and, importantly, how chromosome translocation triggers an essential signaling pathway.

Keywords: Cell cycle, cell polarity, signal transduction, chromosome segregation, bacteria

eTOC

Guzzo et al. reveal a mechanism for coupling cell division to DNA replication in Caulobacter crescentus. They find that active translocation of a newly replicated chromosome activates an essential signal transduction pathway by recruiting the intermediate component of that pathway to the cell pole.

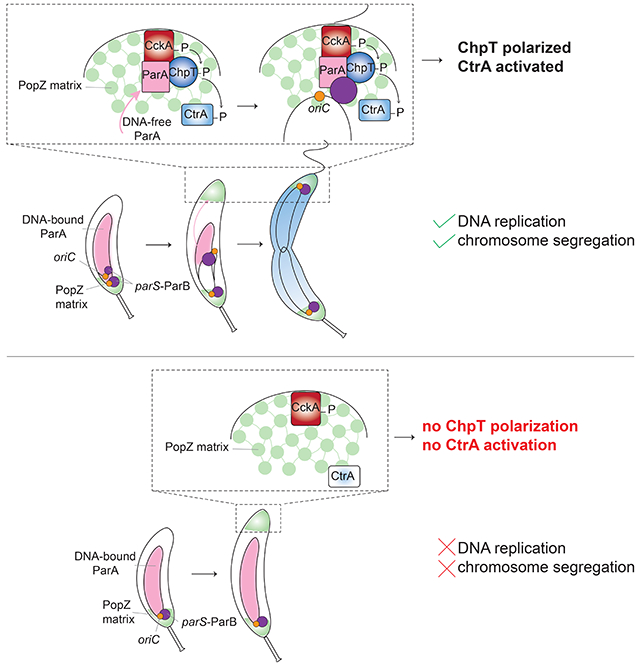

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In all domains of life, cells must ensure that DNA replication, chromosome segregation, and cell division occur in the right order. A failure to coordinate these cell-cycle processes can lead to genome instability or cell death (Storchova and Pellman, 2004). In eukaryotes, numerous checkpoint systems ensure that each step of the cell cycle has completed before proceeding to the next one (Hartwell and Weinert, 1989; Murray, 1992). Few bona fide checkpoints have been identified in bacteria (Rudner and Losick, 2001) and the mechanisms that ensure orderly progression through the bacterial cell cycle remain largely unknown.

The α-proteobacterium Caulobacter crescentus has a tightly regulated cell cycle with DNA replication occurring only once per cell cycle under all growth conditions (Marczynski, 1999). C. crescentus also features an asymmetric cell division that generates two distinct daughter cells: a sessile stalked cell that immediately initiates replication and a motile swarmer cell that cannot initiate replication until it differentiates into a stalked cell (Fig. 1A). The initiation of DNA replication requires (i) the inactivation of CtrA, a response regulator that can directly silence the origin of replication (Domian et al, 1997; Quon et al, 1998), and (ii) accumulation of ATP-bound DnaA, the conserved replication initiator protein in bacteria (Gorbatyuk and Marczynski, 2001; Fernandez-Fernandez et al., 2011; Jonas et al., 2011). CtrA must then be produced de novo and activated by phosphorylation after DNA replication has initiated. In predivisional cells, CtrA directly promotes the expression of nearly 100 target genes critical to many cellular processes, including cell division (Laub et al., 2000, 2002). If DNA replication is blocked, CtrA is not produced (Wortinger et al., 2000) and cell division does not occur (Iniesta et al., 2010b), but the mechanism responsible for coupling replication to CtrA activation has not been identified.

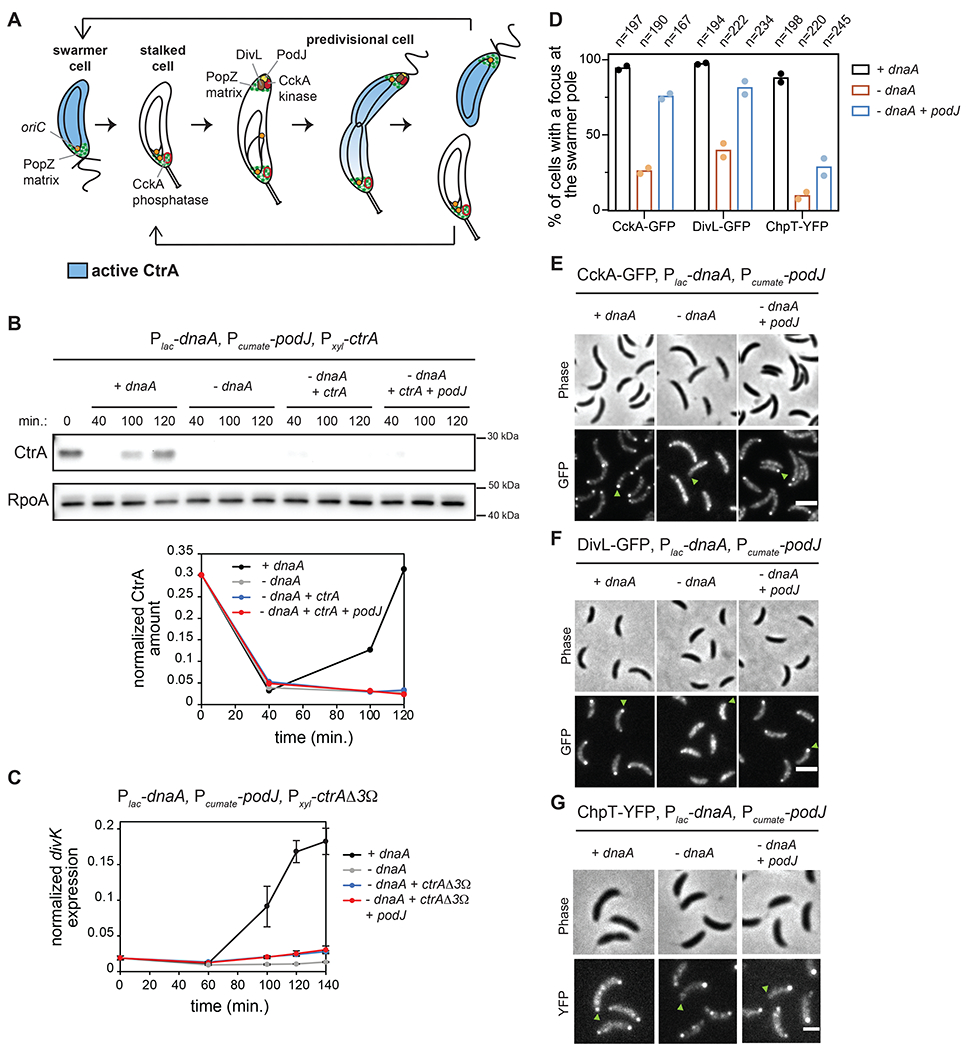

Figure 1: Polarization of CckA and DivL is not sufficient to activate CtrA if DNA replication is inhibited.

(A) Schematic of the C. crescentus cell cycle.

(B) CtrA immunoblots in synchronized cells expressing dnaA (+IPTG) or depleted of dnaA (-IPTG) with ectopic expression of ctrA (+0.075% xyl) and podJ (+cumate) when indicated. Times indicate minutes post-synchronization. Graph shows CtrA band intensity normalized to RpoA control.

(C) mRNA levels of the CtrA-activated gene divK measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to rpoA mRNA levels in cells expressing dnaA (+IPTG) or depleted of dnaA (-IPTG) with ectopic expression of the proteolytically stable mutant ctrAΔ3Ω (+0.075% xyl) and podJ (+cumate) when indicated. Data represent the mean ±SD of three biological replicates.

(D-G) Localization of CckA-GFP (E), DivL-GFP (F) and ChpT-YFP (G) in fixed cells (90 min. post-synchronization) expressing dnaA (+IPTG) or depleted of dnaA (-IPTG) with or without ectopic expression of podJ (+cumate). Green arrows: swarmer pole of one representative cell for each condition. (D) Percentage of cells with detectable foci of CckA-GFP, DivL-GFP, or ChpT-YFP at the swarmer pole in each condition. Bars indicate mean from two biological replicates shown as individual datapoints. Total number of cells from two biological replicates is indicated above. Scale bars = 2 μm.

CtrA activity is controlled by a phosphorelay from the histidine kinase CckA to the histidine phosphotransferase ChpT to CtrA (Biondi et al., 2006) (Fig. S1A). Following DNA replication, CckA is recruited to the nascent swarmer pole of predivisional cells where its kinase activity is stimulated by the atypical histidine kinase DivL (Jacobs et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2009; Angelastro et al., 2010; Iniesta et al., 2010a; Tsokos et al., 2011) (Fig. 1A, S1A). CckA and ChpT also drive phosphorylation of CpdR to prevent it from promoting CtrA degradation (Jenal and Fuchs, 1998; Biondi et al., 2006; Iniesta et al., 2006; Chien et al., 2007) (Fig. S1A). The localization of CckA and DivL to the swarmer pole and CckA kinase activity depend on DNA replication initiation (Iniesta et al., 2010b), but the underlying mechanism is not known. Additionally, whether the localization of CckA and DivL is the key means of coupling DNA replication to CtrA activation and subsequent cell division has not been established.

Here, we show that swarmer pole localization of CckA and DivL can be restored in the absence of DNA replication by ectopically producing the scaffold protein PodJ. Surprisingly though, this polarization of CckA and DivL is not sufficient to activate CtrA. Instead, we find that the activation of CtrA after DNA replication has initiated depends on the recruitment of the intermediate component of the phosphorelay, ChpT, to the swarmer pole by the chromosome segregation machinery. Replication initiation occurs near the stalked pole in Caulobacter. One of the duplicated chromosomes is then translocated to the opposite cell pole via a complex interplay between the nucleoid-bound ATPase ParA and the protein ParB bound to origin-proximal parS sites (Toro et al., 2008; Lim et al., 2014). We show that the accumulation of nucleoid-free ParA at the swarmer pole once chromosome translocation has completed drives the recruitment of ChpT, thereby completing the phosphorelay from CckA to CtrA. When DNA replication initiation is blocked or chromosome translocation is disrupted, ChpT fails to accumulate at the swarmer pole, preventing cell division. Thus, our work now reveals the molecular basis of a substrate-product relationship, rather than a checkpoint, by which replication and cell division are coupled in Caulobacter crescentus. More broadly, our results also demonstrate how a physical cue, in this case the translocation of a chromosome, can serve as the activating signal for a complex signal transduction pathway.

Results

CtrA activation in predivisional cells depends on DNA replication

Prior studies have indicated that CtrA activation in predivisional cells depends on DNA replication initiation (Wortinger et al., 2000; Iniesta et al., 2010b). To corroborate this observation and establish a genetic system for further studying it, we used a strain in which the endogenous dnaA promoter was replaced by the E. coli lac promoter and the lacI gene was integrated at the hfa locus (Badrinarayanan et al., 2015). This strain also contains plasmids to induce the expression of ctrA and podJ which we detail below. We grew cells in the absence of IPTG for 90 minutes to deplete DnaA, and then synchronized and released cells into fresh minimal medium (M2G+) with or without IPTG to induce dnaA expression or not, respectively. In the presence of DnaA, DNA replication initiated within 40 min., as judged by flow cytometry (Fig. S1B), whereas in DnaA-depleted cells, DNA replication had not initiated even by the end of the time-course (120 min.) (Gorbatyuk and Marczynski, 2001) (Fig. S1B).

To test whether CtrA was activated in the absence of DNA replication, we first used Western blots to measure CtrA abundance. The accumulation of CtrA in predivisional cells depends on a positive feedback loop wherein active, phosphorylated CtrA promotes its own transcription and accumulation (Quon et al., 1998). In cells producing DnaA, CtrA accumulated in late predivisional cells, ~120 min. post-synchronization, as expected (Fig. 1B, S1C), but in cells lacking DnaA, CtrA did not accumulate (Fig. 1B, S1C) because ctrA is not transcribed in cells that lack DnaA (Holtzendorff et al., 2004). Therefore, we ectopically expressed ctrA from a xylose-inducible promoter on a plasmid in cells also depleted of DnaA, but CtrA still did not accumulate by 120 min. post-synchronization in the presence of xylose, presumably because it gets degraded (Fig. 1B, S1C).

The lack of CtrA accumulation in cells depleted of DnaA supports the notion that CtrA activation is dependent on DNA replication initiation. However, cells lacking DnaA could be competent for CtrA phosphorylation, but also be actively degrading CtrA. To rule out this possibility, we expressed a constitutively stable variant, ctrAΔ3Ω that can still be regulated by phosphorylation (Domian et al., 1997) (Fig. S1D), in cells depleted of DnaA. We now observed an accumulation of this stabilized CtrA (Fig. S1E). To assess CtrA phosphorylation, we used qRT-PCR to measure mRNA levels of the CtrA target gene divK. In cells expressing dnaA, either with or without inducing ctrAΔ3Ω, divK mRNA levels increased substantially in predivisional cells (Fig. 1C, S1F). In contrast, for cells depleted of DnaA, divK expression remained low throughout the cell cycle either with or without CtrAΔ3Ω being produced (Fig. 1C). Thus, even if abundant in cells, CtrA is not phosphorylated in the absence of DnaA and DNA replication initiation.

Known regulators cannot account for a failure to activate CtrA after inhibiting DNA replication

DnaA promotes the transcription of gcrA (Hottes et al., 2005), a key transcriptional regulator in Caulobacter (Haakonsen et al., 2015). Thus, in the absence of DnaA, either GcrA or an unknown GcrA-regulated factor that is required for CtrA activation could be missing. To test this possibility, we ectopically expressed gcrA-3xflag (Fig. S1G) and ctrA in cells depleted of DnaA. However, CtrA did not accumulate in predivisional cells of this strain (Fig. S1G), and divK was not activated even when expressing non-degradable CtrAΔ3Ω (Fig. S2A). These results indicate that a lack of GcrA in the absence of DnaA is not responsible for blocking CtrA activation.

Next, we considered whether inhibiting DNA replication initiation somehow inactivated CckA. Prior work showed that CckA can be directly inhibited by c-di-GMP (Lori et al., 2015). To test if DNA replication leads to CckA inhibition through c-di-GMP, we reduced c-di-GMP levels in cells depleted of DnaA by expressing a phosphodiesterase (PA5295) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Abel et al., 2013). In this strain, low c-di-GMP levels prevented CtrA degradation at the swarmer-to-stalk cell transition, so CtrA remained present throughout the cell cycle (Fig. S2B). However, divK expression was not upregulated in the absence of DnaA when expressing this phosphodiesterase (Fig. S2C). Thus, we infer that blocking DNA replication does not prevent CtrA activation through c-di-GMP-dependent inhibition of CckA.

Finally, we tested whether SciP, a protein that inhibits CtrA transcriptional activity in swarmer cells (Gora et al., 2010), somehow accumulated following a block to replication initiation. However, SciP was still properly degraded 30 min. after synchronization and remained low in cells depleted of dnaA (Fig. S2D), indicating that an accumulation of SciP does not explain the inhibition of CtrA if DNA replication fails to initiate.

Polar localization of DivL and CckA is not sufficient to activate CtrA following a block to DNA replication

CtrA phosphorylation in predivisional cells depends on the polar localization of the histidine kinases CckA and DivL (Jacobs et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2009; Angelastro et al., 2010; Iniesta et al., 2010a; Tsokos et al., 2011). This localization of CckA and DivL depends on DNA replication (Iniesta et al., 2010b), and we confirmed that in the absence of DnaA, CckA-GFP and DivL-GFP localization to the nascent swarmer pole of predivisional cells is reduced (Fig. 1D–F, S2E–G). We then wanted to test if this defect in CckA and DivL localization was the limiting step for CtrA activation in the absence of DnaA. Notably, DnaA directly upregulates podJ expression after replication initiation (Hottes et al., 2005) (Fig. S1D) and the polar localization of DivL and CckA both depend on PodJ (Curtis et al., 2012). Thus, to test if PodJ was the limiting factor for CckA and DivL localization (and ultimately for CtrA activation) in the absence of DnaA, we ectopically expressed podJ using a cumate-inducible promoter (Kaczmarczyk et al., 2013) in the dnaA depletion strain expressing ctrAΔ3Ω (Fig. S1D). Inducing PodJ was sufficient to restore CckA-GFP and DivL-GFP to the nascent swarmer pole in the absence of DnaA (Fig. 1D–F, S2E–G; −dnaA +podJ condition). To test if CtrA activation was restored, we took cells depleted of DnaA and ectopically expressed ctrA and podJ. CtrA levels remained low even 120 min. after synchronization (Fig. 1B, S1C) and divK expression was not upregulated, even when expressing the ctrAΔ3Ω stable variant (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that PodJ production is sufficient to polarize CckA and DivL in the absence of DNA replication, but that CtrA is still not phosphorylated.

Importantly, the phosphorylation of CtrA requires autophosphorylated CckA to transfer a phosphoryl group to the histidine phosphotransferase ChpT which then serves as the direct phosphodonor to CtrA (Biondi et al., 2006) (Fig. S1A). ChpT was not considered in previous studies of how DNA replication initiation affects CtrA. To test whether ChpT localization depends on replication initiation, we engineered the DnaA-depletion strain to produce ChpT-YFP from its native genomic locus. In the presence of DnaA, ChpT-YFP foci were seen at the nascent swarmer pole of predivisional cells (Fig. 1D,G, S2E,H). In contrast, for cells depleted of DnaA, no foci were seen at that pole, only the stalked pole (Fig. 1D,G, SE,H). Thus, like CckA and DivL, ChpT localization to the nascent swarmer pole depends on the successful initiation of DNA replication. However, in sharp contrast to our observations for CckA and DivL, the ectopic production of PodJ was not sufficient to localize ChpT-YFP (Fig. 1D,G, SE,H). Thus, ChpT localization to the swarmer pole is not determined simply by the localization of CckA. Additionally, this finding indicates that localization of ChpT may be the limiting step in coupling CtrA activation to DNA replication initiation.

Only partial replication of the chromosome is required for CtrA activation

The findings presented thus far suggest that the requirement for DnaA in localizing ChpT to the swarmer pole, and in turn activating CtrA, is not related to its role as a transcription factor. Thus, we favored the possibility that something about the act of DNA replication itself, which is triggered by DnaA, is required to activate CtrA. To further explore how replication controls CtrA activation, we examined a strain in which wild-type DnaA was depleted but ectopically produces DnaA(R357A), which is likely locked in the active, ATP-bound form (Fernandez-Fernandez et al., 2011; Jonas et al., 2011). This strain overinitiates DNA replication and the chromosome content per cell exceeds 2N, as judged by flow cytometry (Fig. S3A). Using qPCR at seven loci along the chromosome (Fig. 2A), we found that cells producing DnaA(R357A), accumulated up to 5 copies of genomic regions near the origin (Fig. 2A). In contrast, cells producing wild-type DnaA had at most 2 copies, as expected for wild-type Caulobacter (Marczynski, 1999) (Fig. 2A). Despite the high initiation rate of cells producing DnaA(R357A), the genomic copy number was less than 2 at 0.67 Mb and unreplicated beyond 1 Mb (Fig. 2A). Thus, this strain enabled us to ask whether only partial (~1/3) replication of the chromosome was sufficient to activate CtrA.

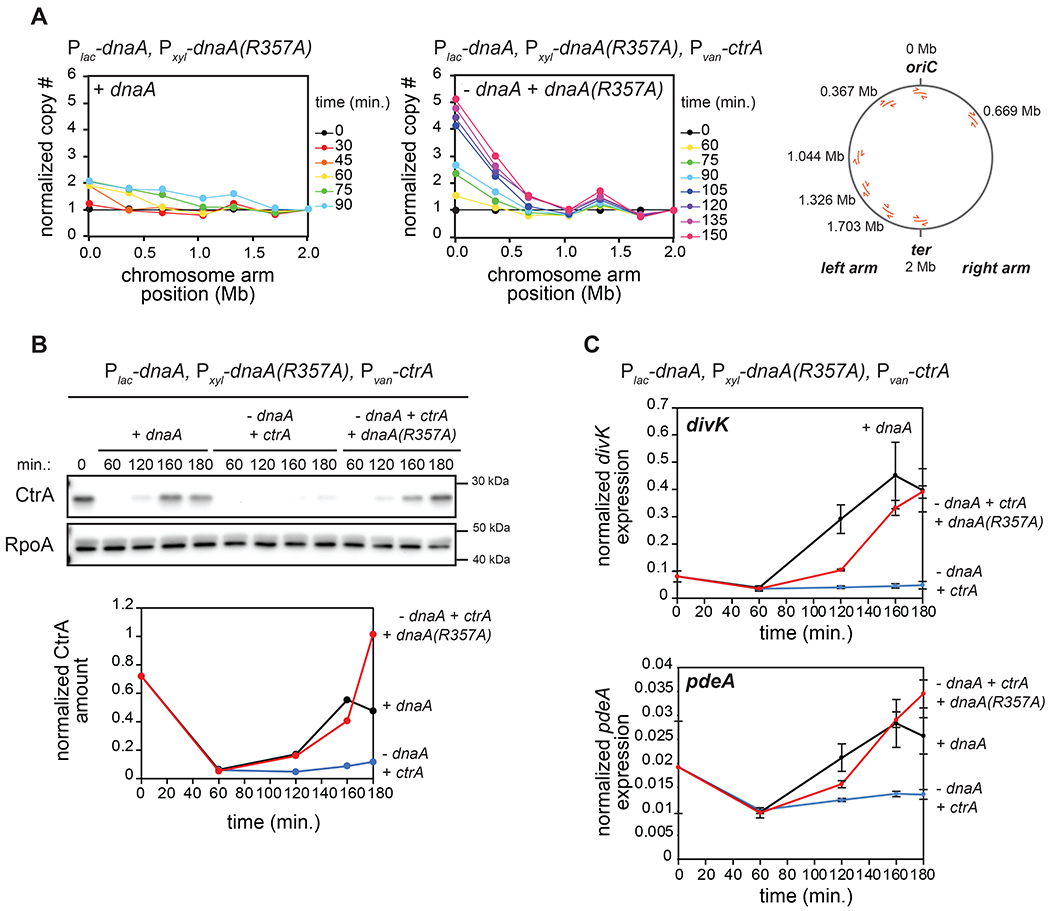

Figure 2: Replication of the full chromosome is not required for CtrA activation.

(A) qPCR on genomic DNA from cells expressing dnaA (+IPTG) or depleted of dnaA and expressing the dnaA(R357A) ATP-locked mutant (-IPTG +xyl) at different times post-synchronization. Map of C. crescentus chromosome (right) shows the localization of primers used. Samples were normalized to DNA levels close to the terminus and then normalized to t=0 min. to evaluate copy number. For the ‘+dnaA’ condition, samples after t=90 min. were excluded as DNA close to the terminus has been replicated.

(B) CtrA levels at the times indicated post-synchronization in cells expressing dnaA (+IPTG) or depleted of dnaA (-IPTG) with ectopic expression of wild-type ctrA (+van) and with (+xyl) or without ectopic expression of dnaA(R357A). Graph shows CtrA band intensity normalized to RpoA.

(C) mRNA levels of the CtrA-activated genes divK and pdeA measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to rpoA mRNA levels for cells treated as in (B). Data represent the mean ±SD of three biological replicates.

We first examined ctrA transcription, finding that it remained relatively low in cells producing DnaA(R357A) (Fig. S3B) despite the accumulation of GcrA (Fig. S3C), possibly because the ctrA locus at 0.764 Mb remains fully methylated, which reduces its transcription (Holtzendorff et al., 2004). We therefore placed ctrA under the control of a vanillate-inducible promoter in cells also engineered to deplete wild-type DnaA and produce DnaA(R357A). We depleted DnaA for 90 minutes, synchronized cells, and released them into a medium that enables repression of wild-type DnaA and induction of DnaA(R357A) and ctrA (Fig. S3D). CtrA now strongly accumulated in late predivisional cells despite the absence of full chromosome replication (Fig. 2B, S3E). Additionally, the CtrA-regulated genes divK and pdeA were strongly upregulated in cells expressing both dnaA(R357A) and ctrA compared to cells depleted of DnaA (Fig. 2C). We conclude that replication of the entire chromosome is not required for CtrA activation. Either the act of replication initiation itself or an event coupled to the earliest stages of replication is required.

Disrupting chromosome segregation prevents CtrA activation

Our experiments with the overinitiating dnaA(R357A) strain suggested that replication of the first third of the chromosome is sufficient to trigger CtrA activation in predivisional cells (Fig. 2). Notably, chromosome segregation is initiated upon replication of the parS site, which is located just 8 kb-away from oriC, the chromosomal origin of replication (Toro et al., 2008). After the parS locus is duplicated, one of the copies separates away from the stalked pole, and then ParA and ParB drive its rapid translocation across the cell to the nascent swarmer pole (Ptacin et al., 2010; Schofield et al., 2010; Shebelut et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2014) (Fig. 3A). Thus, we decided to investigate whether segregation of the chromosome is a critical step in CtrA activation. Such a role for chromosome segregation was previously dismissed (Iniesta et al., 2010b) because synthesizing ParA(K20R), a variant of ParA that blocks chromosome segregation without altering replication (Toro et al., 2008) (Fig. S4A), did not affect CckA-GFP localization. However, the impact of ParA(K20R) on CtrA activation and ChpT localization was not tested.

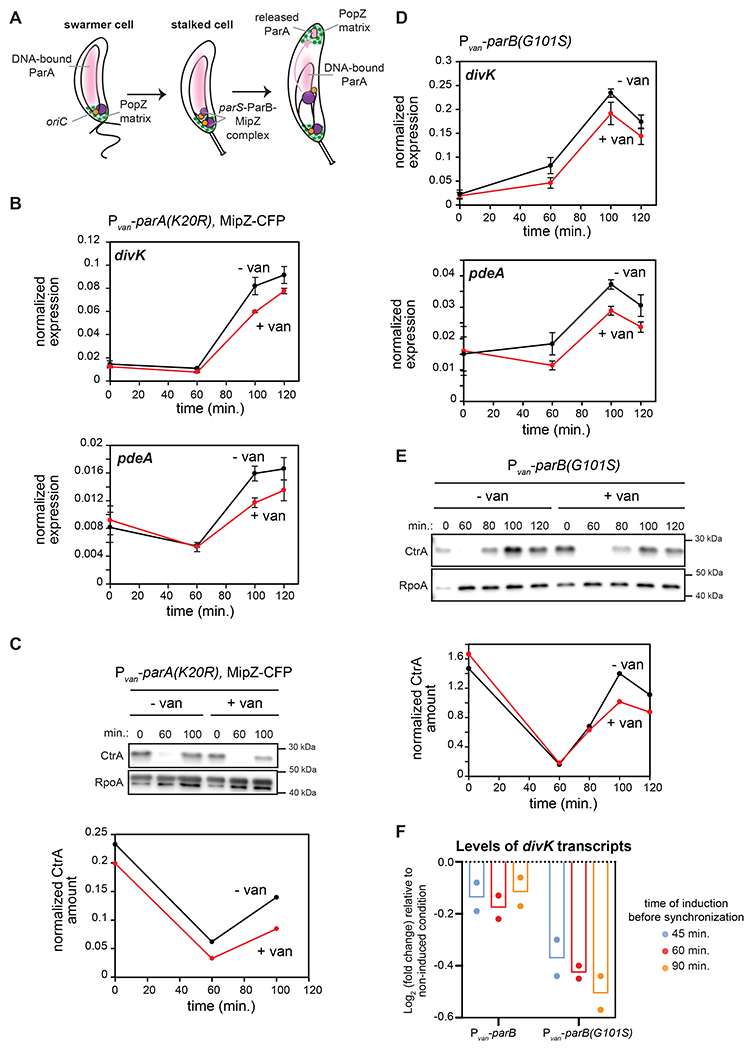

Figure 3: CtrA activation in predivisional cells is reduced when chromosome segregation is perturbed.

(A) Schematic of chromosome segregation during the C. crescentus cell cycle.

(B) mRNA levels of divK and pdeA measured as in Fig. 2C at the times indicated post-synchronization in cells expressing (+van) or not (-van) parA(K20R). parA(K20R) was induced 60 min. pre- and post-synchronization with 500 μM van. Data represent the mean ±SD of three biological replicates.

(C) CtrA levels at the times indicated post-synchronization in cells treated as in (B). Graph shows CtrA band intensity normalized to RpoA.

(D) mRNA levels of divK and pdeA measured as in Fig. 2C at the times indicated post-synchronization in cells expressing (+van) or not (-van) the spreading-deficient parB(G101S) mutant. parB(G101S) was induced 60 min. pre- and post-synchronization with 500 μM van. Data represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

(E) CtrA levels at the times indicated post-synchronization in cells from the same conditions as in (D). Graph shows CtrA band intensity normalized to RpoA.

(F) Relative fold-change in mRNA levels of divK measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to rpoA mRNA levels 100 min. post-synchronization, when inducing parB or parB(G101S) 45, 60, or 90 min. pre-synchronization compared to the uninduced condition. Bars indicate mean from two biological replicates shown as individual datapoints.

We first tested if disrupting chromosome segregation by ectopically expressing parA(K20R) would affect CtrA activation. To try and maximize the disruption of chromosome segregation but retain synchronizability of cells, we induced parA(K20R) 60 minutes before synchronizing cells (Fig. 3B–C, S4B). We found that the expression levels of two CtrA-activated genes, divK and pdeA, and CtrA protein levels were both modestly, but significantly reduced in predivisional cells (100 min. post-synchronization) expressing parA(K20R) compared to the non-induced condition (Fig. 3B–C, S4B). These results indicated that improper segregation of the chromosome impacts CtrA activation. ParA(K20R) did not completely eliminate CtrA activation, likely due to the heterogeneity of ParA(K20R) accumulation and an incomplete disruption of chromosome segregation, which we return to later.

To corroborate the results with ParA(K20R), we sought to perturb chromosome segregation, again without disrupting DNA replication, in an alternative way. To do this, we overexpressed the spreading-deficient mutant parB(G101S) (Tran et al., 2018), which contains a point mutation in the arginine-rich patch important for CTP binding (Jalal et al., 2020). Inducing parB(G101S) does not affect DNA replication (Fig. S4C), but prevents chromosome segregation, as indicated by a failure to segregate the ParB-associated protein MipZ to the nascent swarmer pole (Fig. S4D). As with parA(K20R), inducing the expression of parB(G101S) 60 minutes before synchronization also modestly, but significantly, reduced the expression levels of two CtrA-regulated genes, divK and pdeA, and CtrA protein levels (Fig. 3D–E, S4B). Additionally, we observed that inducing parB(G101S) for increasingly longer times prior to synchronization (45 min., 60 min. or 90 min.) enhanced the effect on CtrA activation (Fig. 3F), suggesting that the reduction in CtrA activation is proportional to the accumulation of parB(G101S). Notably, we did not observe this dose-response effect when expressing wild-type parB instead of parB(G101S) (Fig. 3F). Taken together, our results suggest that chromosome segregation is critical in triggering the proper accumulation of phosphorylated, active CtrA following DNA replication initiation.

Disrupting chromosome segregation affects the localization of ChpT, but not CckA and DivL

To investigate the connection between chromosome translocation and the polarization of DivL, CckA, and ChpT, we induced parA(K20R) from a vanillate-inducible promoter in cells also expressing MipZ-CFP, CckA-GFP, DivL-GFP, or ChpT-sfGFP at their native genomic loci. When inducing parA(K20R) for 30 min. before synchronization, some cells can divide while some cannot and instead become elongated. The percentage of elongated cells when expressing parA(K20R) was 38% for MipZ-CFP (n=309), 50% for CckA-GFP (n=335), 36% for DivL-GFP (n=207) and 35% for ChpT-sfGFP (n=310). This heterogeneity likely reflects heterogeneity in ParA(K20R) accumulation, with elongated, undivided cells representing those with enough ParA(K20R) to disrupt chromosome segregation. We therefore focused on elongated cells that had not divided by 270 min. after synchronization in the following time-lapse experiments; for reference, non-induced cells handled identically divide after ~150 min. (Fig. 4A, top). In the elongated cells, MipZ-CFP (which binds and labels ParB-parS complexes (Thanbichler and Shapiro, 2006)) localization to the new pole was strongly reduced, as expected if chromosome segregation is disrupted (Toro et al., 2008) (Fig. 4B–C). For both dividing and elongating cells, CckA-GFP and DivL-GFP accumulated at the new swarmer pole in almost all cells of the population (Fig. 4B, D, S5A–B) (Iniesta et al., 2010b), consistent with our findings that CckA and DivL localization depends primarily on PodJ accumulation at the pole (Fig. 1D–F), not DNA replication or subsequent chromosome segregation.

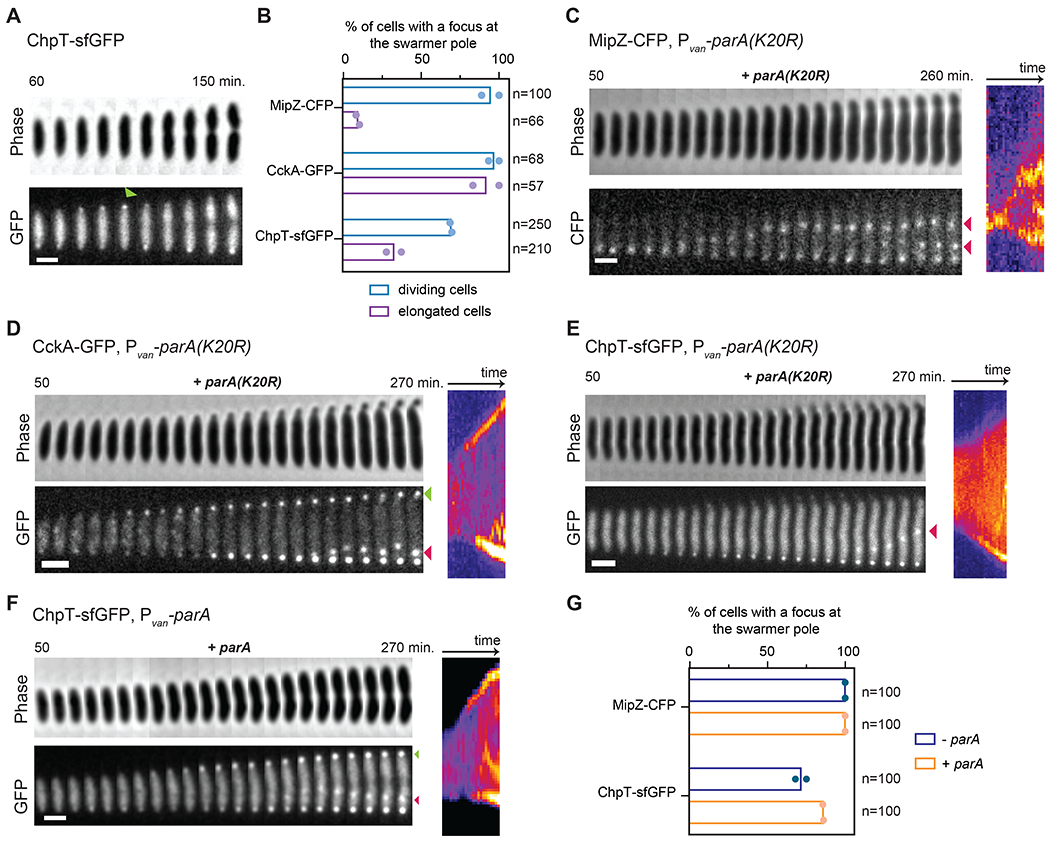

Figure 4: ChpT access to the new swarmer pole is blocked when chromosome segregation is disrupted.

(A) Time-lapse of ChpT-sfGFP in a wild-type cell, imaged at 10 min. intervals from 60 to 150 min. post-synchronization, with consecutive frames straightened and pasted side-by-side to generate the concatenated figure. Green arrow indicates transient ChpT-sfGFP localization at the new pole. Scale bar=1 μm.

(B) Percentage of cells with detectable foci at the swarmer pole at any time during time-lapse imaging of MipZ-CFP, CckA-GFP and ChpT-sfGFP without parA(K20R) induction (dividing cells;-van) and with parA(K20R) induction (elongated cells only; +van). parA(K20R) was induced 30 min. pre- and post-synchronization with 500 μM vanillate. Bars indicate mean from two biological replicates shown as individual datapoints. Total # of cells examined from two biological replicates indicated in each case.

(C-E) Examples from time-lapse imaging of cells quantified in (B). Consecutive time-points are straightened and pasted side-by-side to generate the concatenated figure (left), with a corresponding kymograph (right). In (C), red arrows indicate MipZ-CFP internal clusters next to the newly replicated chromosomal origins. In (D), green arrow shows CckA-GFP localization at the new swarmer pole and red arrow shows CckA-GFP accumulation in a single internal cluster. In (E), red arrow shows ChpT-sfGFP accumulation in a single internal cluster. Scale bars = 1 μm.

(F) Time-lapse of ChpT-sfGFP within a single cell ectopically expressing wild-type parA. parA was induced 30 min. pre-synchronization and during imaging post-synchronization in the agarose pad with 500 μM vanillate. Green arrow shows ChpT-sfGFP localization at the new swarmer pole. Red arrow shows ChpT-sfGFP accumulation in a single internal cluster. Scale bar = 1 μm.

(G) Percentage of cells with detectable foci at the swarmer pole at any time during time-lapse imaging of ChpT-sfGFP (Fig. 4F) and MipZ-CFP (Fig. S5F) (n=100 cells for each condition) without (-van condition) or with parA induction (+van). Bars indicate mean from two biological replicates shown as individual datapoints.

In sharp contrast to CckA and DivL, only 30% of elongated cells producing ParA(K20R) had detectable ChpT-sfGFP foci at the nascent swarmer pole (Fig. 4B, E), compared to 60% of dividing cells. Although not all dividing cells had detectable foci of ChpT-sfGFP at the swarmer pole, we noted that ChpT-sfGFP also was only detectable at this pole in 66% of wild-type cells (Fig. 4A, S5C–D, Movie S1). In general, we found that ChpT localization was difficult to detect, in part due to its transient localization at the new pole (Fig. S5E). This behavior may reflect the cytosolic nature of ChpT compared to membrane-bound DivL and CckA or the inability of ChpT alone to access the swarmer pole compartment (see below). Whatever the case, our results suggest that, unlike CckA and DivL, ChpT localization to the swarmer pole depends on proper chromosome segregation.

We also examined ChpT-sfGFP localization in cells overexpressing a wild-type copy of parA (Fig. 4F–G), which does not prevent chromosome translocation as with parA(K20R) (Fig. S5F). In these cells, ChpT-sfGFP now accumulated at the nascent swarmer pole (Fig. 4F–G). In fact, whereas ChpT-sfGFP localization to that pole is typically transient in WT cells (Fig. 4A, S5C–D, Movie S1) and not always easily detectable (detected in 66% of n=100 cells), overexpression of wild-type parA increased the persistence of ChpT-sfGFP at the new pole in most of the cells in the population (compare Fig. 4F to 4A and S5C), and resembled MipZ-CFP localization under the same conditions (compare Fig. 4F and S5F). Collectively, our results support the conclusion that localization of ChpT to the swarmer pole, and subsequent activation of CtrA, depends on successful chromosome translocation, which occurs shortly after replication initiation.

ChpT localization to the new pole and access to the PopZ microdomain depends on ParA

For ChpT-sfGFP to localize to the swarmer pole, it must access the microdomain formed by the polar organizer protein PopZ, which excludes most cytoplasmic proteins (Ebersbach et al., 2008; Bowman et al., 2010) unless they bind a component of the microdomain (Lasker et al., 2020). The formation of the PopZ microdomain was not affected by the overexpression of parA(K20R) (Laloux and Jacobs-Wagner, 2013) (Fig. S5G), and ChpT-sfGFP appeared confined to the rest of the cell (Fig. 4E) suggesting that ChpT is excluded from the PopZ microdomain in the absence of chromosome translocation. Overexpressing popZ can expand the PopZ microdomain, especially at the old cell pole (Ebersbach et al., 2008; Bowman et al., 2010; Lasker et al., 2020). We induced the expression of popZ after synchronization (of cells also producing ParA(K20R) to disrupt chromosome segregation) and asked how this affected CckA and ChpT localization within 270 min. post-synchronization. CckA-GFP remained bipolar (Fig. 5A, S6A), suggesting that an excess of PopZ does not disrupt recruitment or retention of CckA in these conditions. In contrast, ChpT-sfGFP completely failed to accumulate at the swarmer pole following popZ overexpression, with a significant drop in the ChpT-sfGFP cytoplasmic signal and concomitantly stronger signal at the old, stalked pole (Fig. 5B, S6B). These results indicated that ChpT is indeed excluded from the swarmer pole microdomain and that an additional component is necessary for ChpT to access that pole. Additionally, overexpressing popZ has recently been shown to reduce CtrA activation (Lasker et al., 2020), consistent with a reduction of ChpT access to the new pole where phosphotransfer from CckA to ChpT to CtrA can occur.

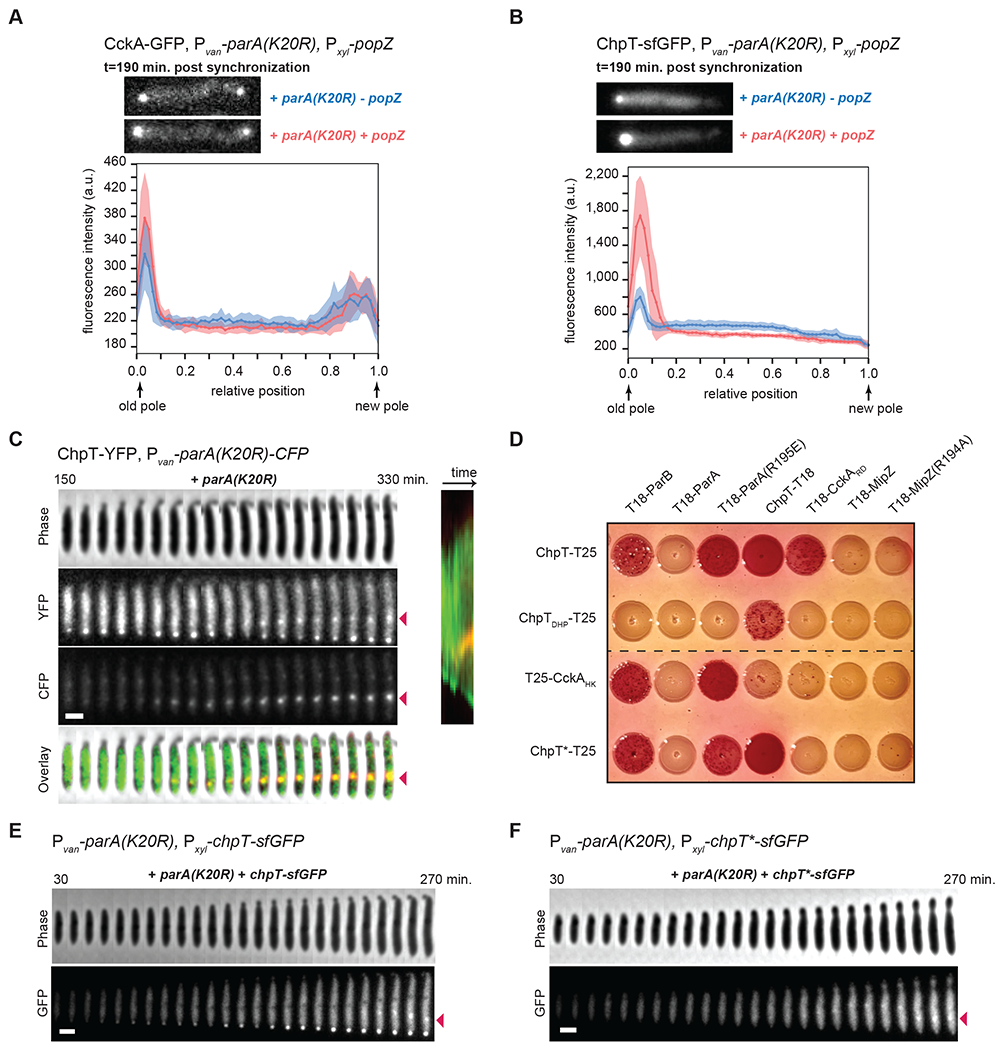

Figure 5: ParA not bound to DNA recruits ChpT to the swarmer pole.

(A-B) Fluorescence micrographs (top) of CckA-GFP (A) or ChpT-sfGFP (B) in cells expressing parA(K20R) (+van) with (+xyl) or without (−xyl) induction of popZ post-synchronization (also see Fig. S6A–B). Graphs (bottom) show the average fluorescence intensities (solid line) from the old pole to the new pole from 15 cells for each condition. Shading around the solid line represents the SD. Scale bars = 1 μm.

(C) Time-lapse of ChpT-YFP and ParA(K20R)-CFP in a single cell when inducing parA(K20R)-cfp (+van). parA(K20R)-cfp was induced 30 min. pre-synchronization and during imaging in the agarose pad with 500 μM vanillate. In the overlay, ChpT-YFP is in green and ParA(K20R)-CFP in red. Red arrows show the ChpT-YFP and ParA(K20R)-CFP internal cluster. Scale bar = 1 μm.

(D) Bacterial two-hybrid assay. BTH101 reporter cells producing the indicated proteins or domains fused to the T18 or T25 domain of Bordetella adenylate cyclase were spotted on MacConkey agar plates supplemented with IPTG and maltose. Interaction between two fusion proteins results in a red colony color. ChpTDHP: ChpT Dimerization and Histidine phosphotransfer domain; CckAHK: CckA Histidine Kinase domain; CckARD: CckA receiver domain; ChpT*: ChpT(R167E, R169E, R171E).

(E-F) Time-lapse imaging of ChpT-sfGFP (E) or ChpT*-sfGFP (F) when produced (+xyl) in cells expressing parA(K20R) (+van). parA(K20R) was induced 30 min. pre-synchronization and during imaging in the agarose pad with 500 μM vanillate. chpT-sfGFP or chpT*-sfGFP was induced at t=0 min. post-synchronization and in agarose pads with 0.3% xylose. Red arrows show the internal cluster of ChpT-sfGFP or ChpT*-sfGFP internal cluster. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Our single-cell observations showed that (i) overexpression of wild-type parA led to prolonged localization of ChpT-sfGFP at the swarmer pole compared to wild-type cells (compare Fig. 4A and 4F) and (ii) overexpression of parA(K20R), which was previously demonstrated to reduce ParA accumulation at the swarmer pole (Laloux and Jacobs-Wagner, 2013), also reduces localization of ChpT-sfGFP to the new pole (Fig. 4E). Given these observations, we hypothesized that ParA may normally promote ChpT localization to the new pole in predivisional cells and provide it access to the PopZ microdomain.

Consistent with a role for ParA in recruiting ChpT, we found that cells expressing an ectopic copy of parA(K20R) also developed a single dynamic and non-polar internal cluster of CckA-GFP, DivL-GFP, and ChpT-sfGFP (Fig. 4D–E, S5B). This internal cluster was seen in a majority of elongated cells for each fusion protein (70% for CckA-GFP, 96% for DivL-GFP and 86% for ChpT-sfGFP with n=50 elongated cells in each case). These internal clusters arose relatively late in our time-lapse experiments, likely after additional rounds of DNA replication had initiated at the stalked pole, as evidenced by the fact that MipZ-CFP also formed internal clusters in elongated cells overexpressing parA(K20R) (Fig. 4C). However, whereas MipZ-CFP often accumulated in multiple internal clusters (Fig. 4C), we only ever saw the formation of a single internal cluster of CckA-GFP, DivL-GFP, and ChpT-sfGFP (Fig. 4D–E, S5B). We hypothesized that ParA(K20R) was accumulating at one of the newly formed parS/ParB/MipZ complexes (next to a newly replicated origin) and was recruiting CckA-GFP, DivL-GFP, and ChpT-sfGFP to this cytoplasmic position within the cell. To test this hypothesis, we expressed ParA(K20R) fused to CFP in cells also expressing YFP-MipZ or ChpT-YFP. We found that ParA(K20R)-CFP accumulated in a single internal cluster that colocalized with one of the YFP-MipZ internal clusters (Fig. S6C) and with the single ChpT-YFP internal cluster (Fig. 5C) in a majority of the cells (85% for MipZ-YFP and 95% for ChpT-YFP with n=20 elongated cells in each case).

Previous work found that ChpT, CckA, and ParA all interact with PopZ (Schofield et al., 2010; Holmes et al., 2016). We therefore tested if PopZ was accumulating at these internal clusters and recruiting CckA and ChpT. In elongated cells expressing parA(K20R), we found that while PopZ-YFP accumulated strongly at the swarmer pole, very little PopZ-YFP signal was found in internal clusters (Fig. S5G), suggesting that ChpT and CckA accumulation in the internal clusters does not depend on PopZ.

ParA not bound to DNA recruits ChpT to the swarmer pole

Our results suggest that ChpT-sfGFP gets recruited to internal parS/ParB/MipZ complexes only when an excess of ParA molecules accumulates at that complex (Fig. 4E–F, 5C). In wild-type stalked cells undergoing chromosome translocation, dimers of ParA-ATP decorate the nucleoid and the newly formed parS/ParB/MipZ complex moves toward the swarmer pole through ParB-mediated hydrolysis of ParA-ATP into ParA-ADP (Ptacin et al., 2010; Schofield et al., 2010; Shebelut et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2014). ParA-ADP molecules released from the DNA are thought to relocate to the swarmer pole where they bind PopZ (Ptacin et al., 2014) (Fig. 3A). We hypothesized that ChpT is normally targeted to the swarmer pole or to internal clusters by binding ParA molecules not bound to DNA. Consistent with this hypothesis, we did not observe ChpT moving across cells with the translocating chromosome in wild-type cells when ParA is mostly nucleoid-associated (Fig. 4A, S5C). To further test this hypothesis and to examine whether ParA and ChpT interact, we used a bacterial two-hybrid system in which two proteins of interest are fused to the T18 and T25 portions of adenylate cyclase. If the two proteins interact, they reconstitute adenylate cyclase activity, leading to production of a red pigment. We did not detect any interaction between ChpT and wild-type ParA (Fig. 5D). However, when testing ChpT and ParA(R195E), a DNA-binding deficient mutant of ParA (Ptacin et al., 2010; Schofield et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2014), we now observed colonies with intense red staining, indicative of an interaction (Fig. 5D), and supporting a model in which ChpT can bind ParA that is not bound to DNA.

ParA can dimerize and cycle through both ATP and ADP bound states. To test how these features of ParA impact interaction with ChpT, we tested different point mutants of ParA using our two-hybrid assay: ParA(G16V), a dimerization-deficient mutant that can presumably bind ATP or ADP but not DNA; ParA(K20R), an ATP-binding deficient mutant described above; and ParA(D44A), an ATP-locked mutant (Ptacin et al., 2010). For G16V, we still observed some red staining, suggesting that this variant still binds ChpT (Fig. S6D), likely because disrupting dimerization prevents or diminishes DNA binding by ParA. For K20R and D44A, these mutants of ParA did not interact with ChpT (Fig. S6D). However, combining each with the R195E mutation that disrupts DNA-binding produced red colonies indicative of an interaction (Fig. S6D). We conclude that the DNA-binding status of ParA, and not its ATP/ADP state, is most critical for an interaction with ChpT.

We also detected an interaction between the histidine kinase domain of CckA (CckAHK) and ParA(R195E), but not with wild-type ParA (Fig. 5D). Further, we found that ChpT and CckAHK can each interact to some extent with ParB in our bacterial two-hybrid assay (Fig. 5D), but did not observe any interaction with either MipZ or the DNA-binding deficient mutant MipZ(R194A) (Corrales-Guerrero et al., 2020) (Fig. 5D). Finally, we found that the C-terminal domain of ChpT, which weakly resembles the ATP-binding domain of a histidine kinase (Fioravanti et al., 2012; Blair et al., 2013), was required for its interaction with ParA and ParB (Fig. 5D). The N-terminal domain of ChpT, which resembles the DHp domain found in histidine kinases, is critical for mediating phosphotransfer from CckA and to CtrA. The function of ChpT’s C-terminal domain had been unclear, although required for CckA binding (Fig. 5D), but our results now suggest it mediates binding to ParA that is not bound to the nucleoid.

Based on our bacterial two-hybrid assay, we infer that ChpT and CckA are recruited to internal clusters by excess levels of ParA that are unbound to DNA and associated with a ParBIparS complex. However, while ChpT recruitment to the new pole is disrupted when chromosome segregation is incomplete, CckA polarization is not (Iniesta et al., 2010b), likely because it depends on PodJ (Fig. 1D–E) rather than ParA (Fig. 4B, D). To confirm that ChpT was being recruited to internal clusters independent of CckA, we constructed a ChpT variant that we call ChpT* containing the substitutions R167E, R169E, and R171E, which were predicted by the available ChpT structures to bind CckA (Fioravanti et al., 2012; Blair et al., 2013). Indeed, ChpT* could not bind CckA in our two-hybrid system, but retained interaction with ParA(R195E) and ParB (Fig. 5D). We then ectopically expressed either ChpT or ChpT* fused to sfGFP in cells with a vanillate-inducible copy of parA(K20R). In the absence of vanillate, ChpT-sfGFP localized to the swarmer pole in 70% of cells (n=50) (Fig. S6E), whereas ChpT*-sfGFP did not localize at either cell pole at any stage of the cell cycle (n=50) (Fig. S6F). These results support the notion that ChpT interaction with CckA is necessary but not sufficient for ChpT to accumulate at the poles. In the presence of vanillate to induce parA(K20R), ChpT-sfGFP accumulated at the old, stalked pole and in an internal cluster in 80% of the cells (n=50) (Fig. 5E). By contrast, ChpT*-sfGFP accumulated only in an internal cluster in 64% of the cells (n=50) (Fig. 5F). These results demonstrate that ChpT recruitment to internal clusters occurs in a CckA-independent manner and likely reflects its direct interaction with the chromosome segregation machinery. Taken all together, our results support a model in which chromosome translocation normally leads to an accumulation of ParA unbound to DNA at the nascent swarmer pole, which recruits ChpT to enable phosphotransfer from CckA to CtrA and, ultimately, successful completion of the cell cycle.

Discussion

A substrate-product relationship that couples cell division to DNA replication

How organisms ensure the correct order of events during the cell cycle is critical to their survival. Hartwell and Weinert outlined two general mechanisms for enforcing order (Hartwell and Weinert, 1989). One involves dedicated checkpoints, which they envisioned as surveillance systems that are not involved in executing either of two events but are involved only in monitoring and promoting their relative order of execution. The second involves substrate-product relationships in which the product of one event is the substrate for the next, thereby intrinsically ensuring they occur only in succession. Here, we uncovered a substrate-product relationship that couples cell division in Caulobacter to the successful initiation of DNA replication (Fig. 6). The late stages of the Caulobacter cell cycle include flagellar and pili biogenesis, as well as cell division. These events all depend on the phosphorylation of CtrA, which is driven by CckA and ChpT. The localization of these latter two factors to the swarmer cell pole is necessary for CtrA activation and dependent on the initiation of DNA replication (Fig. 1D–G, 6) (Iniesta et al., 2010b). DnaA, likely in the ATP-bound form, is a transcription factor that promotes the synthesis of PodJ (Hottes et al., 2005), which then recruits CckA and DivL to the swarmer pole. However, even in cells ectopically producing PodJ (and, consequently, with CckA and DivL at the pole), CtrA is not activated (Fig. 1B–C, 6). We found that ChpT is not localized unless the ori-proximal region of a newly replicated chromosome is properly translocated across the cell to the swarmer pole (Fig. 4E, 6). Our findings suggest that ParA, which is nucleoid-associated when promoting the directional movement of the parS/ParB complex, eventually accumulates at the pole and is not bound to DNA, enabling it to recruit ChpT and complete the CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay (Fig. 6). Consistent with this model, in cells producing ParA(K20R), CckA still localizes to the pole (Fig. 4D), and still autophosphorylates (Iniesta et al., 2010b), but it cannot robustly drive CtrA phosphorylation without ChpT. Thus, the translocating chromosome is a physical cue that ultimately triggers CtrA activation, thereby ensuring that cell division, and other CtrA-dependent processes, do not occur until after DNA replication has successfully initiated.

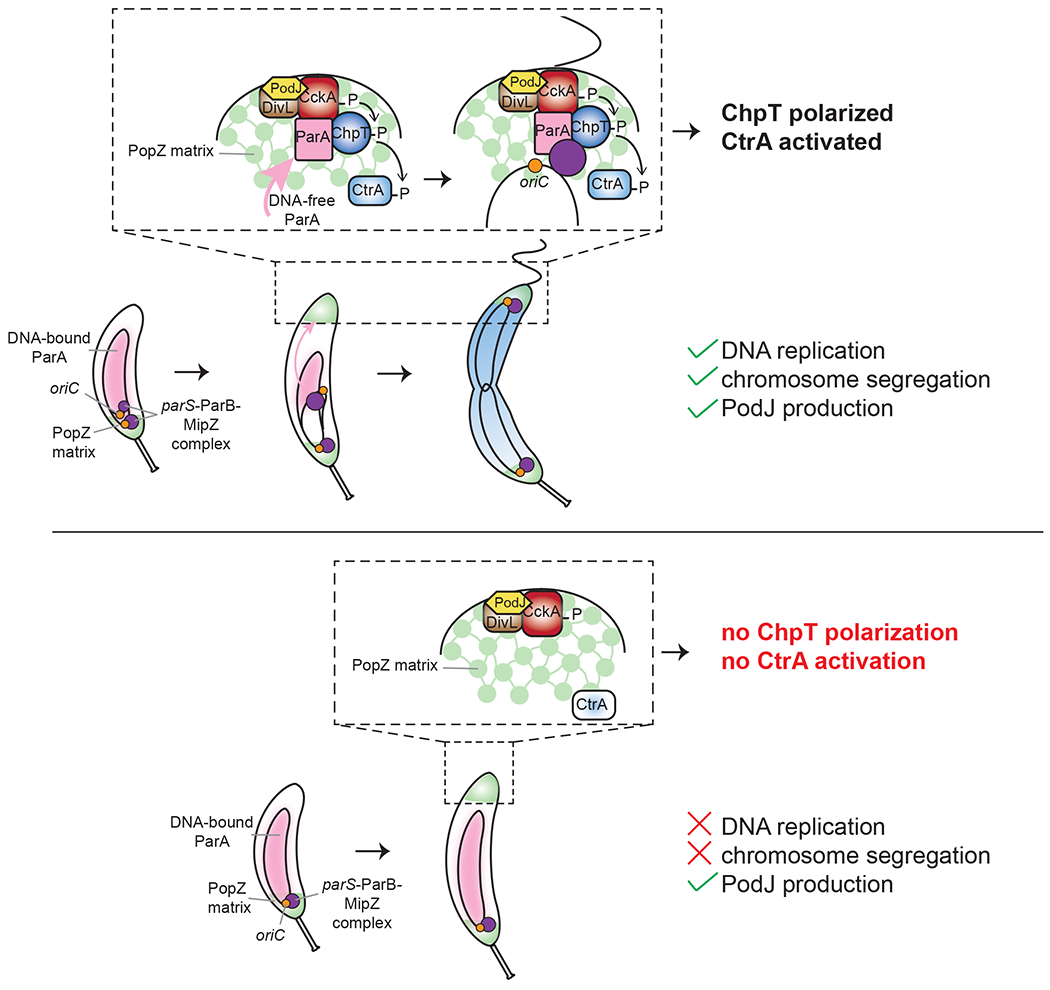

Figure 6: Model for coupling DNA replication initiation and proper chromosome translocation to activation of the CckA-ChpT signaling pathway.

Schematic of the localization of CtrA regulators to the new pole. In wild-type cells (top panel), the initiation of DNA replication and proper accumulation of ParA at the new pole within the PopZ matrix enables accumulation of ChpT to complete the CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay. In cells that do not initiate DNA replication (bottom panel), production of the scaffold protein PodJ can restore the polarization of CckA and DivL, but does not allow ChpT accumulation within the PopZ matrix, leading to an incomplete phosphorelay and failure to activate CtrA.

The use of chromosome position to couple cell-cycle processes also arises in many species to tie the final stages of chromosome segregation to the onset of cytokinesis. For instance, in E. coli, unsegregated chromosomes at mid-cell accumulate the cell division inhibitor SlmA such that cytokinesis cannot occur until after chromosomes are properly separated away from mid-cell (Bernhardt and De Boer, 2005). Noc in B. subtilis (Wu and Errington, 2004) and MipZ in C. crescentus (Thanbichler and Shapiro, 2006) play analogous roles. Notably, these systems for coupling chromosome segregation to cell division and the mechanism identified here for coupling replication to cell division feature substrate-product relationships, rather than checkpoint mechanisms involving regulatory feedback systems, as is commonly found in eukaryotes. Understanding why bacteria may rely more heavily on substrate-product relationships to order their cell cycles remains a fascinating question for the future.

Activation of a signaling pathway by the physical translocation of a chromosome

For most two-component signaling pathways, the signals that activate them remain unknown. For cases in which a signal has been identified, most feature small molecules or low molecular weight proteins that bind to a periplasmic or transmembrane domain of a top-level histidine kinase. Although CckA and its activator DivL both reside in the inner membrane, no periplasmic or extracellular signals have been identified that regulate their activities. DivL is directly regulated by the cytoplasmic response regulator DivK (Tsokos et al., 2011) and CckA by cytoplasmic c-di-GMP (Lori et al., 2015). Our work here now indicates that a major cue for the CtrA phosphorelay involves the initially duplicated region of the chromosome, which serves to recruit ChpT via the ParA and ParB segregation complex. There is some precedent for signal sensing by intermediate components of complex phosphorelays, with Rap phosphatases in B. subtilis known to regulate the response regulator Spo0B, which shuttles phosphoryl groups from KinA/B/C/D/E to the histidine phosphotransferase Spo0F (Solomon et al., 1996; Perego, 2013). However, in that system, the Rap phosphatases respond to small Phr peptides, not a physical cue like chromosome translocation.

Notably, our work indicates that CckA alone is not sufficient to recruit ChpT to the swarmer pole, despite being sufficient to bind and phosphorylate ChpT in vitro (Biondi et al., 2006). This difference likely reflects a constraint, or barrier, imposed by the PopZ matrix that is established at the swarmer cell pole. PopZ forms a dense, interconnected matrix with possible phase-separated properties that enable the compartmentalization of the cytoplasm (Bowman et al., 2010; Schofield et al., 2010). We found that ChpT cannot access this polar microdomain unless translocation of the parS/ParB complex has occurred, likely because the movement of this complex across the cell is required to produce a pool of ParA at the pole that is not nucleoid bound. Although CckA is not sufficient to recruit ChpT inside the PopZ matrix, ChpT interaction with CckA is required for its accumulation at the nascent swarmer pole.

We found that in a bacterial two-hybrid system, ChpT and CckA could interact with ParA, but only if ParA was not DNA bound suggesting that DNA binding occludes the ChpT and CckA binding site(s). Additionally, we found that in Caulobacter cells in which chromosome translocation was disrupted, ChpT and CckA were recruited to internal sites within the cytoplasm harboring the parS/ParB/ParA machinery. However, only ChpT access to the swarmer pole was dependent on a successful segregation of the chromosome; CckA accumulation at the swarmer pole was not. Importantly, ChpT co-localization with the Par machinery at internal clusters occurred even for a ChpT variant engineered to ablate binding to CckA, supporting the notion that ChpT recruitment by ParA and ParB is independent of CckA.

Limitations of the Study

Although we favor a model in which ParA recruits ChpT after accumulating at the pole when it is no longer nucleoid bound, we cannot rule out a role for ParB, which also binds ChpT (Fig. 5D). In either case, it also remains unclear whether ChpT binds simultaneously to both ParA/ParB and CckA/CtrA at the swarmer pole. Further work is needed to explore the biochemical and biophysical details of ChpT’s multiple protein-protein interactions. Finally, we note that there was a relatively modest reduction in CtrA activity in cells in which chromosome segregation was disrupted (Fig. 3). This may stem in part from the heterogeneity in the timing and extent of chromosome segregation inhibition in cells producing ParA(K20R) or ParB(G101S) (Fig. 4), but could also indicate that alternative mechanisms for regulating CtrA exist.

Concluding Remarks

Our results indicate that the PopZ microdomain may serve multiple functions in Caulobacter. As suggested previously, it may increase the effective concentration of various signaling proteins at the pole to promote or increase their activities (Bowman et al., 2010; Holmes et al., 2016; Lasker et al., 2020). In addition, we propose that it also serves as a gatekeeper that selectively excludes some proteins like ChpT until others have arrived, thereby providing regulatory capabilities to cells. In a similar way, phase-separated granules and bodies in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells are emerging as powerful regulators and organizers of many cellular processes (Banani et al., 2017; Gomes and Shorter, 2019).

The mechanism identified here in which chromosome translocation serves as a physical cue to trigger a signaling pathway is likely conserved. Homologs of ChpT, PopZ, and the parS/ParB/ParA system are found throughout the α-proteobacteria and could work in similar ways. The Par system is found even more broadly and it has become increasingly clear that ParB and ParA can interact with a wide variety of proteins other than each other (Thanbichler and Shapiro, 2006; Gruber and Errington, 2009; Schofield et al., 2010; Mercy et al., 2019; Kawalek et al., 2020; Pioro and Jakimowicz, 2020), and so could participate in the regulated recruitment of proteins in other contexts and for other purposes.

In sum, our work reveals a mechanism by which bacterial cells coordinate two cell-cycle events, ensuring that cell division does not inadvertently occur before DNA replication in C. crescentus. Although the timing and execution of each individual process – DNA replication initiation and cell division – has been extremely well-studied, how cells sense whether the former has occurred and relay this information to the latter has remained unclear. We found a connection linking the physical translocation of the origin-proximal region of a chromosome to the activation of a signaling pathway that controls cell-cycle progression. Chromosome movement and positioning is a common signal in eukaryotes; for instance, the failure to properly segregate chromosomes activates the spindle checkpoint pathway (Gorbsky, 2015). Our work suggests that bacteria may similarly use chromosome dynamics as an important cue for regulating cell-cycle progression.

STAR Methods

Resource availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Michael T. Laub (laub@mit.edu).

Materials Availability

All materials generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact without restriction.

Data and Code Availability

This study did not generate any dataset or code.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Growth conditions

Caulobacter crescentus strains were grown in PYE (2 g/L bactopeptone, 1g/L yeast extract, 0.3 g/L MgSO4, 0.5 mM 0.5M CaCl2) or in fresh M2G+ (0.87 g/L Na2HPO4, 0.53 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L NH4Cl, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 10 μM FeSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1% PYE, 0.2% glucose) at 30°C. Expression from the Plac promoter was induced with 1 mM IPTG. Expression from the Pxyl promoter was repressed with glucose (0.2%) and induced with xylose (0.3%) unless noted. Expression from the Pcumate promoter was induced with 0.2 μM cumate. Expression from the Pvan promoter was induced with vanillate (500 μM) unless noted. To maintain plasmids, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations (liquid/plate): kanamycin (5 μg mL−1 / 25 μg mL−1), oxytetracycline (1 μg mL−1 / 2 μg mL−1), gentamycin (2.5 μg mL−1 / 5 μg mL−1), chloramphenicol (2 μg mL−1/1 μg mL−1).

E. coli strains were grown in LB (10 g/L NaCl, 10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract) and supplemented with antibiotics at the following concentrations unless noted (liquid/plate): kanamycin (30 μg mL−1 / 50 μg mL−1), oxytetracycline (12 μg mL−1 / 12 μg mL−1), gentamycin (15 μg mL−1 / 20 μg mL−1), chloramphenicol (20 μg mL−1 / 30 μg mL−1), carbenicillin (50 μg mL−1 / 100 μg mL−1).

Strain construction

All Caulobacter strains were derivative of the wild-type isolate ML76 from the CB15N/NA1000 strain.

Strains ML3364 and ML3365 were constructed using ΦCr30 phage transduction (Ely, 1991) to move pMT585-gcrA-3xFLAG integrated at the xyl locus from ML2297 into ML2000 and selecting on kanamycin + glucose + IPTG. This intermediate strain was then electroporated with pRVMCS-5-ctrA or pRVMCS-5-ctrAΔ3Ω respectively selecting on tetracycline + kanamycin + glucose + IPTG.

To construct ML3361 and ML3362, ML2000 was first transduced using ΦCr30 phage transduction (Ely, 1991) with ML1681 or ML1756 respectively and selected on gentamycin + IPTG plates. These intermediate strains were then electroporated with pQF-podJ and selected on oxytetracycline + gentamycin + IPTG. Strain ML3378 was constructed by electroporating pBXMCS-2-dnaA(R357A) into the same intermediate strain as above from ML2000’s transduction with ML1681 and selecting on kanamycin + IPTG + glucose plates. Strain ML3379 was constructed by electroporating pRVMCS-5-ctrA into ML3378 and selecting on oxytetracycline + kanamycin + IPTG + glucose plates.

ML1071 is a lab collection strain. Although the details of this construction are unknown, the linker between ChpT and the C-terminal YFP was sequenced and contains the following sequence; CGGGGCTCGGGCGCCACCATG.

ML2000 was transformed with pQF-podJ by electroporation followed by selection on oxytetracycline + IPTG. This intermediate strain was used to construct: ML3363 using ΦCr30 phage transduction (Ely, 1991) to move ChpT-YFP from ML1071; ML3359 and ML3360 by electroporating pJS14 PxylX::ctrA or pJS14 PxylX::ctrAΔ3Ω, respectively and selecting on oxytetracycline + chloramphenicol + glucose + IPTG plates; ML3367 by electroporating pBVMCS-4-PA5295 and selecting on oxytetracycline + gentamycin + IPTG plates.

To construct ML3370, ML3372 and ML3379, strains ML2395, ML1756 and ML1900 were electroporated with pRVMCS-6-parA(K20R). To construct ML3371, ML3382 and ML3383, ML76 was electroporated with pRVMCS-6-parA(K20R) selecting on chloramphenicol plates, and this intermediate strain was then transduced with CckA-eGFP from ML1681 for ML3371, or electroporated with pXGFPC-2-chpT-sfgfp or pXGFPC-2-chpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-sfgfp and selected on chloramphenicol + kanamycin + glucose plates, to construct ML3382 and ML3383 respectively.

Strain ML3373 was constructed by electroporating pYFPC-2-chpT-sfgfp into ML76 and selecting on kanamycin plates. Strains ML3374 and ML3375 were constructed by electroporating pRVMCS-6-parA(K20R) or pRVMCS-6-parA, respectively, into ML3373.

Strain ML3376 was constructed by electroporating pRVMCS-6-parA into ML2395 and selecting on chloramphenicol + gentamycin plates.

Strains ML3377 and ML3378 were constructed by electroporating pRVMCS-6-parA(K20R)-cfp into ML3415 and ML1071 respectively.

Strains ML3380 and ML3381 were constructed by electroporating pBXMCS-4-popZ and pBXMCS-2-popZ into ML3374 and ML3371 respectively and selecting on chloramphenicol + gentamycin + kanamycin plates.

To construct ML3384, TLS1629 was transduced with ML2397 (MipZ-CFP, kanR) and selected on kanamycin + chloramphenicol plates.

Method details

Time courses and synchronization

Cells were grown overnight in PYE with appropriate antibiotics and inducers (1 mM IPTG for Plac-dnaA strains) or repressors (0.2% glucose for xylose inducible constructions). Cells were diluted in M2G+ supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and inducers when necessary and grown to OD600 ~ 0.1 to 0.4. For synchronization, cells were first centrifuged for 10 min. at 10,000 g. G1/swarmer cells were isolated using Percoll (GE Healthcare) density gradient centrifugation. Briefly, pellets were resuspended in equal amounts of M2 buffer (0.87 g/liter Na2HPO4, 0.53 g/liter KH2PO4, 0.5 g/liter NH4Cl) and Percoll and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min. The upper ring was aspirated, and the lower ring, corresponding to swarmer cells, was transferred into a new 15-ml Falcon tube. Swarmer cells were washed in 13 ml of M2 buffer and centrifuged for 5 min. at 10,000 g. The pellet was resuspended in 2 ml M2 buffer and centrifuged for 1 min. at 21,000 g. Cells were released into M2G+ supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (and adjusted to OD600 ~ 0.05 to 0.2 when necessary) and the culture was split into different flasks with different inducers. At the indicated time points, samples were harvested from each flask for flow cytometry (0.15 ml), immunoblotting (1 ml), and RNA extraction followed by qRT-PCR (2 ml). For flow cytometry, samples were stored in 30% ethanol at 4°C. For immunoblotting and RNA extraction, cells were centrifuged for 1 min. at 15,000 rpm, aspirated, and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

For the DnaA depletion strains, prior to synchronization, at OD600 ~ 0.1 to 0.25, cells were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min, washed 2 times with M2G+, released into M2G+ with appropriate antibiotics without IPTG for 1.5 hours. Cells were then synchronized as described above.

For cells induced presynchronization, the culture was split into two flasks and one was induced with 500 μM vanillate for the indicated time. OD600 before induction were adjusted to be less than 0.4 at the end of the induction time. Cells were then synchronized as described above.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as described previously (Guzzo et al., 2020). A fraction of fixed cells from the time course sampling (corresponding to an OD600 of ~ 0.005) were centrifuged at 6,0 rpm for 4 min. Pelleted cells were resuspended in 1 ml of Na2CO3 buffer containing 3 μg/ml RNase A (Qiagen) and incubated at 50°C for at least 4 h. Cells were supplemented with 0.5 μl/ml SYTOX Green nucleic acid stain (Invitrogen) in Na2CO3 buffer and analyzed on a MACSQuant VYB flow cytometer.

Reverse transcription coupled to quantitative PCR

Reverse transcription coupled to quantitative PCR was performed as described previously (Guzzo et al., 2020). RNA was extracted using hot TRIzol lysis and the Direct-zol RNA miniprep kit (Zymo). 2.5-μl of RNA at 50-100 ng/μl was mixed with 0.5 μl of 100-ng/μl random hexamer primers (Invitrogen), 0.5 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and 3 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) water; incubated at 65°C for 5 min; and then placed on ice for 1 min. Two microliters of first-strand synthesis buffer, 0.5 μl of 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 μl of SUPERase-In (ThermoFisher), and 0.5 μl of Superscript III (ThermoFisher) were added to each tube, and the following thermocycler program was used: 10 min. at 25°C, 1 h at 50°C, and 15 min. at 70°C. One microliter of RNase H (NEB) was added to each tube, and each reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 20 min.

cDNA solutions were diluted 10 times in nuclease-free water for quantitative PCR (qPCR). One microliter of diluted cDNA or serially diluted genomic DNA (gDNA) used as a standard curve was mixed with an appropriate pair of primers, i.e., either rpoA_qPCR_1 and rpoA_qPCR_2 as a control, ctrA_qPCR_1 and ctrA_qPCR_5, divK_qPCR_1 and divK_qPCR_2, pdeA_qPCR_3 and pdeA_qPCR_5 or podJ_qPCR_1 and podJ_qPCR_2, and 2X qPCR Master Mix. All experimental samples were loaded as duplicates and with standard curves on a 384-well plate for qPCR. qPCR was conducted in a LightCycler 480 system (Roche) using the following thermocycler program: 95°C for 10 min, 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s with 40 cycles of steps 2 to 4.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (Guzzo et al., 2020). Frozen pellets from the time course sampling were normalized by OD600 for resuspension in 1x blue loading buffer (NEB) supplemented with 1x reducing agent (DTT), boiled at 95°C for 10 min, and loaded on 12% gels (Bio-Rad) for electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred from the gel into polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes and immunoblotted. Antibodies were used at the concentrations shown in parentheses: anti-RpoA (1:5,000, BioLegend), anti-CtrA (1:5,000), anti-SciP (1:2000) and anti-GcrA (1:5,000). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (ThermoFisher) were used at the concentrations shown in parentheses: anti-mouse (1:10,000) and anti-rabbit (1:5,000). The membranes were developed with SuperSignal West Femto maximum-sensitivity substrate (ThermoFisher) and visualized with a FluorChem R Imager (ProteinSimple). Original unprocessed immunoblots are available on Mendeley Data (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/9d9n7pccfp/1).

Microscopy

Cells were grown overnight in PYE with appropriate antibiotics and inducer (1 mM IPTG for Plac-dnaA constructions) or repressor (0.2% glucose for xylose inducible constructions) when appropriate . Cells were diluted in M2G+ supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and inducer/repressor and grown to OD600 ~ 0.1 to 0.3. When appropriate, DnaA was depleted as described above (see Time courses and synchronization section). For cells induced presynchronization, the culture was split into two flasks and one was induced with 500 μM vanillate for 30 minutes before synchronization. Cells were synchronized as described above (see Time courses and synchronization section).

Fixed cells: Cells were released into M2G+ supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (and adjusted to OD600 ~ 0.05 to 0.2 when necessary) and the culture was split into different flasks with different inducers. At t=90 min, 1 mL of culture for each condition was harvested and 25 μl of 16% Paraformaldehyde Aqueous Solution (Fisher Scientific) was added to the cells and gently mixed by inversion. After 1 min. of fixation at room temperature, cells were centrifuged for 1 min. at 10,000 g. Pelleted cells were washed once in 1 x PBS and then resuspended in 1 x PBS. One microliter of cells was spotted onto PBS-1.5% agarose pads and imaged. Phase-contrast and epifluorescence images were taken on a Zeiss Observer Z1 microscope using a 100x/1.4 oil immersion objective and an LED-based Colibri illumination system using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, PA).

Texas-Red-X Succinimidyl-Ester (Thermo Fisher; TRSE) labeling: Cells were released into M2G+ supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (and adjusted to OD600 ~ 0.05 to 0.2 when necessary) and the culture was split into different flasks with different inducers. At t=90 min, 1 mL of culture for each condition was harvested, centrifuged for 1 min. at 10,000 g, resuspended in 1 ml of bicarbonate buffer containing 1 μg/ml TRSE and incubated for 5 min. at room temperature. Cells were then centrifuged for 1 min. at 10,000 g and fixed as described above. The cells were washed twice in 1 x PBS after fixation and observed under the microscope as described above for fixed cells.

Live imaging: After synchronization, cells were released in M2G+ with or without inducer (note that xylose when indicated is added at t=0 and not prior to synchronization). Cells were grown in flask for 10 min. and then one microliter of cells was spotted onto M2G+-1.5% agarose pads containing or not appropriate inducers in a 35 mm Glass bottom dish. Phase-contrast and epifluorescence images were taken on a Zeiss Observer Z1 microscope using a 100x/1.4 oil immersion objective and an LED-based Colibri illumination system using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, PA). Images were taken every 10 minutes for up to 250 minutes starting 20 minutes or 30 minutes after synchronization in a 30°C incubation chamber.

Bacterial two-hybrid

Protein interactions were assayed using the bacterial adenylate cyclase two-hybrid system (Karimova et al., 1998). Genes of interest were fused to the 3’ or 5’ end of the T18 or T25 fragments of Bordetella adenylate cyclase using the pUT18C, pUT18, pKT25, or pKNT25 vectors. Different combinations of T18-/T25-fusion plasmids were co-transformed into the BTH101 E. coli strain. Co-transformants were grown in LB supplemented with kanamycin and carbenicillin overnight. Saturated cultures were spotted onto MacConkey agar (40 g/L) plates supplemented with maltose (1%), IPTG (1 mM), kanamycin (25 μg mL−1) and carbenicillin (50 μg mL−1). Plates were incubated at 30°C and pictures taken after two days.

qPCR analysis of origin-terminus ratio

Cells were grown overnight in PYE with appropriate antibiotics, 1 mM IPTG and 0.2% glucose. Cells were diluted in M2G+ supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and 1 mM IPTG and grown to OD600 ~ 0.4. To deplete DnaA, cells were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min, washed 3 times in M2 and diluted into M2G+ with appropriate antibiotics without IPTG for 2 hours. After the 2-hour depletion, the cultures (OD600 ~ 0.4) were synchronized as described above. After synchronization, cells were released into M2G+ and split in different flasks with the indicated inducers. Samples were harvested at the indicated timepoints for genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction. gDNA was extracted by resuspending pellets in 600 μL Cell Lysis Solution (QIAGEN) and incubating at 80°C for 5 min. to lyse cells. RNAs were removed by treatment with 50 μg RNase A (QIAGEN) at 37°C for 30 min. 200 μL Protein Precipitation Solution (QIAGEN) was added, the sample vortexed, and left on ice for 30 min. to precipitate proteins. After spinning at 14,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was transferred to a tube containing 600 μL isopropanol and mixed by inversion. DNA was harvested by spinning at 14,000 rpm for 1 min. followed by a wash with 600 μL of 70% ethanol. The DNA pellet was resuspended in 50-100 μL H2O. For qPCR, DNAs were diluted 1:500 and mixed with either Cori_2 (chromosomal position: 0 Mb), CCNA_03518 (chr. pos.: 3.676 Mb), CCNA_00623 (chr. pos.: 0.669 Mb), CCNA_02846 (chr. pos.: 2.999 Mb), CCNA_02567 (chr. pos.: 2.717 Mb), CCNA_02189 (2.340 Mb) or CCNA_01869 (chr. pos.: 2.008 Mb) forward/reverse primer mix and 2X qPCR Master Mix. All experimental samples and standard curves were loaded onto a 384-well plate in duplicate for qPCR. qPCR was conducted in a LightCycler 480 system (Roche) using the following thermocycler program: 95°C for 10 min, 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s with 40 cycles of steps 2 to 4.

Plasmid construction

Integration plasmids

pYFPC-2-chpTsfGFP: the pYFPC-2 plasmid (Thanbichler et al., 2007) was amplified using primers pYFPC2_chpT_up_R and sfGFP_dwn_pYFPC_2_F and the chpT gene was amplified using primers pYFPC2_chpT_up_F and chpT_dwn_sfGFP_up_R. The chpT PCR product, a sfGFP gblock codon optimized for Caulobacter from IDT, and the PCR fragment of the plasmid were assembled together using the Hifi DNA assembly mix (NEB). The construction was verified by sequencing.

pXGFPC-2-chpT-sfGFP: The chpT-sfGFP insert was amplified from pYPPC-2-chpT-sfgfp using primers pBX_chpT_up_F and sfGFP_pXGFPC_down_R2. The pXGFPC-2 plasmid (Thanbichler et al., 2007) was amplified using primers sfGFP_pXGFPC_down_F2 and pBX_chpT_up_R. The two PCR products were assembled together using the Hifi DNA assembly mix (NEB). The construction was verified by sequencing.

pXGFPC-2-chpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-sfGFP: same cloning protocol as pXGFPC-2-chpT-sfGFP but using pKNT25-ChpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-T25 as a template. The construction was verified by sequencing.

Replicative plasmids

Pcumate-podJ: The podJ insert was amplified from a Pvan-podJ containing plasmid using primers podJ_4pQF_1..24 and podJ_4pQF_last24 and. The pQF plasmid (Kaczmarczyk et al., 2013) was amplified using primers pQF_CPEC_up and pQF_CPEC_noFLAG_down. The two PCR products were assembled together using circular polymerase extension cloning (CPEC). The construction was verified by sequencing.

pRVMCS-5-ctrA : This plasmid was cloned by first amplifying ctrA from genomic DNA using primers ctrA-Ndel-F and ctrA-extrastop-Nhel-R. The PCR product was digested with Ndel and Nhel-HF and ligated into similarly digested pRVMCS-5 plasmid (Thanbichler et al., 2007) using T4 DNA ligase. The construction was verified by sequencing.

pRVMCS-5-ctrAΔ3Ω: This plasmid was cloned using the same protocol as for pRVMCS-5-ctrA but by amplifying ctrA from ML46 using primers ctrA-Ndel-F and ctrAD3W-Nhel-R. The construction was verified by sequencing.

pBXMCS-2-dnaA(R357A): This plasmid was cloned by first using around-the-horn PCR to introduce the R357A mutation into dnaA (from a Pvan-dnaA containing plasmid) using primers dnaA 1068..1048 and dnaA 1069..1095 R357A. The dnaA(R357A) allele was then amplified using primers DnaA_rev_3xTAA_EcoRI and Ndel_DnaA_1..23 and cloned into pBXMCS-2 (Thanbichler et al., 2007) using EcoRI/Ndel. The construction was verified by sequencing.

pRVMCS-6-parA(K20R): genomic DNA from ML2414 (Badrinarayanan et al., 2015) was used as a template to amplify parA(K20R) using primers pXYFP_ParA_Ndel_up_F and ParA_TAATAA_Sacl_R. The PCR product was digested with Ndel and Sacl restriction enzymes and ligated into similarly digested pRVMCS-6 plasmid (Thanbichler et al., 2007) using T4 DNA ligase. The construction was verified by sequencing.

pRVMCS-6-parA: the parA gene was amplified from pKT25-parA using primers pRVMCS6_parA_up_F and pRVMCS-6_parA_dwn_R and the pRVMCS-6-parA(K20R) plasmid template was amplified in two separate fragments using primers pRVMCS6_parA_dwn_F and pRVMCS6_upcat_R, and pRVMCS6_parA_up_R and pRMCS_mid_F. The parA fragment and the two plasmid fragments were assembled using the Hifi DNA assembly mix (NEB). The construction was verified by sequencing.

pRVMCS-6-parA(K20R)-CFP: the parA(K20R) fragment was amplified from pRVMCS-6-parA(K20R) using primers pRVMCS-6-parA_up_F and parA_CFP_R. The cfp fragment was amplified from pXCFPC-6 (Thanbichler et al., 2007) using primers parA_CFP_F and CFP_pRVMCS-6_dwn_R. The pRVMCS-6-parA(K20R) plasmid template was amplified in two separate fragments using primers and CFP_pRVMCS-6_dwn_F and pRVMCS6_upcat_R, and pRVMCS6_parA_up_R and pRMCS_mid_F. The parA(K20R) fragment, the cfp insert and the two plasmid fragments were assembled using the Hifi DNA assembly mix (NEB). The construction was verified by sequencing.

pBXMCS-2-popZ and pBXMCS-4-popZ: The popZ insert was amplified from genomic DNA using pBX_popZ_up_F and pB_popZ_down_R and the pBXMCS-2 or pBXMCS-4 (Thanbichler et al., 2007) plasmids were amplified using primers pB_popZ_down_F and pBX_popZ_up_R. The popZ insert and the plasmid PCR product were assembled together using the Hifi DNA assembly mix (NEB). The construction was verified by sequencing.

Bacterial two-hybrid plasmids

All bacterial two-hybrid plasmids were constructed using the Gibson assembly mix (NEB) or the Hifi DNA assembly mix (NEB). All constructions (gene of interest and T18- or T25-fragments) were verified by sequencing.

pKNT25-ChpT : The chpT fragment was amplified using primers pKNT25_chpT_up_F and pKNT25_chpT_down_R. The pKNT25 plasmid was amplified using primers pKNT25_chpT_up_R and pKNT25_chpT_down_F.

pKNT25-ChpTDHP : The chpTDHP fragment was amplified using primers pKNT25_chpT_up_F and pKNT25_chpTDHP_down_R. The pKNT25 plasmid was amplified using primers pKNT25_chpT_up_R and pKNT25_chpTDHP_down_F.

pKT25-CckAHK: The cckAHK fragment was amplified using primers pKT25_cckA_HK_up_F and pKT25_cckA_HK_down_R. The pKT25 plasmid was amplified using primers pKT25_up_R and pKT25_down_F.

pKNT25-ChpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-T25 : Using pKNT25-ChpT as a template, the plasmid was amplified using primers R167E169E171E_short2_F and R167E169E171E_short2_R. The two R167E169E171E ultramers (forward and reverse) were mixed together in equal molar amounts and duplexed using the following thermocycler program: 94°C for 3 minutes, cool down to 25°C over 45 minutes at a pace of 1.5°C per minute. The duplexed ultramers were diluted 100-fold before addition to the Gibson reaction with the plasmid fragment.

pUT18C-ParB : The parB fragment was amplified using primers pUT18C_parB_up_F and pUT18C_parB_down_R. The pUT18C plasmid was amplified using primers pUT18C_parB_up_R and pUT18C_parB_down_F.

pUT18C-ParA and pUT18C-ParA(K20R): The parA or parA(K20R) fragment were amplified using primers pUT18C_parA_up_F and pUT18C_parA_down_R. The pUT18C plasmid was amplified using primers pUT18C_parA_up_R and pUT18C_parA_down_F.

pUT18C-ParA(R195E): Using pUT18C-ParA as a template, the plasmid was amplified using primers ParAR195E_F and ParAR195E_R. The two ParA(R195E) ultramers (forward and reverse) were duplexed and used as described for pKNT25-ChpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-T25.

pUT18C-ParA(K20R)(R195E): Using pUT18C-ParA(K20R) as a template, the plasmid was amplified using primers ParAR195E_F and ParAR195E_R. The two ParA(R195E) ultramers (forward and reverse) were duplexed and used as described for pKNT25-ChpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-T25.

pUT18C-ParA(D44A): Using pUT18C-ParA as a template, the plasmid was amplified using primers ParAD44A_F and ParAD44A_R. The two ParA(D44A) ultramers (forward and reverse) were duplexed and used as described for pKNT25-ChpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-T25.

pUT18C-ParA(D44A)(R195E): Using pUT18C-ParA(R195E) as a template, the plasmid was amplified using primers ParAD44A_F and ParAD44A_R. The two ParA(D44A) ultramers (forward and reverse) were duplexed and used as described for pKNT25-ChpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-T25.

pUT18C-ParA(G16V): Using pUT18C-ParA as a template, the plasmid was amplified using primers ParAG16V_F and ParAG16V_R. The two ParA(G16V) ultramers (forward and reverse) were duplexed and used as described for pKNT25-ChpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-T25.

pUT18-ChpT: The chpT fragment was amplified using primers pUT18_chpT_up_F and pUT18_chpT_down_R. The pUT18 plasmid was amplified using primers pUT18_chpT_up_R and pUT18_chpT_down_F.

pUT18C-CckARD: The cckARD fragment was amplified using primers pUT18C_cckA_RD_up_F and pUT18C_cckA_RD_down_R. The pUT18C plasmid was amplified using primers pUT18C_cckA_RD_up_R and pUT18C_cckA_RD_down_F.

pUT18C-MipZ: The mipZ fragment was amplified using primers pUT18C_mipZ_up_F and pUT18C_mipZ_down_R. The pUT18C plasmid was amplified using primers pUT18C_mipZ_up_R and pUT18C_mipZ_down_F.

pUT18C-MipZ(R194A): this plasmid was first constructed by inserting the R194A mutation into mipZ in the pKNT25-mipZ plasmid using primers mipZR194A_F and mipZR194A_R. The two MipZ(R194A) ultramers (forward and reverse) were duplexed and used as described for pKNT25-ChpT(R167E)(R169E)(R171E)-T25. The pUT18C-MipZ(R194A) plasmid was then constructed by amplifying the mipZ(R194A) fragment from pKNT25-mipZ(R194A) using primers pUT18C_mipZ_up_F and pUT18C_mipZ_down_R and the pUT18C plasmid was amplified using primers pUT18C_mipZ_up_R and pUT18C_mipZ_down_F.

Quantification and statistical analysis

qRT-PCR

Crossing point (Cp) values were calculated from LightCycler 480 software at the second derivative maximum. Technical replicates were averaged to yield a final Cp value for each sample and relative quantities of cDNA were calculated based on a 3-fold dilution standard curve. Each time point value for each gene of interest was normalized to the rpoA measured value, as rpoA expression remains constant in exponential phase.

Dose response fold-differences at timepoint 100 minutes are the ratios between the normalized cDNA relative quantity of the induce condition and the non-induced condition. Independent biological replicates individual datapoints are shown as well as the average ratio.

qPCR/origin-ter ratio

Cp values were calculated from LightCycler 480 software at the second derivative maximum. Technical replicates were averaged to yield a final Cp value for each sample and standard curve point. Relative quantities of cDNA were calculated based on a 3-fold dilution standard curve. Chromosome copy numbers were normalized internally to CCNA_01869 (terminus region) as a loading control and then normalized to the origin abundance after synchrony (0 min) to evaluate fold-change from 1N.

Quantification of protein levels by immunoblotting

Image quantification and analysis was done with Fiji/ImageJ. Band intensities were measured for each protein. RpoA band intensities were used as a loading control for each sample, meaning that each protein band intensity in a specific lane were normalized to RpoA band intensity in that same lane.

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry was analyzed with FlowJo from 50,000 total SYTOX positive events for each experiment. For each experiment, 1N was determined based on the distribution of G1 cells and 2N based on the control condition.

Microscopy