Abstract

PURPOSE:

Immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy is now standard treatment for most patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer (mNSCLC), yet patient supportive care needs (SCNs) on immunotherapy are not well defined. This study characterized the SCNs and financial hardship of patients with mNSCLC treated with immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy and examined the relationship between patient and caregiver cancer-related employment reductions and patient financial hardship.

METHODS:

Patients with mNSCLC on immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy from a single academic medical center completed the SCNs Survey-34, items indexing material, psychological, and behavioral financial hardship, and the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity. Univariate and bivariate analyses examined care needs, financial hardship, and impact of cancer-related employment reductions on patient financial hardship.

RESULTS:

Sixty patients (40% male; 75% White, mean age = 62.5 years, 57% on immunotherapy alone) participated. Fifty-five percent reported unmet needs in physical or daily living and psychological domains. Financial hardship was common (33% material, 63% psychological, and 57% behavioral). Fifty-two percent reported hardship in at least two domains. Forty percent reported a caregiver cancer-related employment reduction. Caregiver employment reduction was related to patient financial hardship (68% of those reporting caregiver employment reduction reported at least two domains of hardship v 40% of those without reduction, P = .03) and patient financial distress (mean Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity = 19.6 among those with caregiver employment reduction v 26.8 without, P = .01).

CONCLUSION:

Patients with mNSCLC treated with immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy report multiple unmet care needs and financial hardship. Psychological, functional, financial, and caregiver concerns merit assessment and intervention in this population.

INTRODUCTION

Immunotherapy with or without chemotherapy is now the standard of care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer (mNSCLC) without sensitizing mutations.1 Compared to cytotoxic chemotherapy, patients treated with immunotherapy may experience improved prognosis, a more tolerable treatment side-effect profile, and better health-related quality of life.2-6 However, immunotherapy is not without challenges, and the supportive care needs (SCNs) (eg, information, psychological support, and symptom management) of these patients are not well defined. At present, it is difficult to predict which patients will have a durable response, leaving many patients and their caregivers with greater uncertainty about what it means to live with metastatic disease.7 Immunotherapy is also expensive, and a prolonged disease course may increase costs to patients and their caregivers.8 Although not well characterized in patients with mNSCLC, data from other long-term survivors suggest patients and caregivers often reduce employment (eg, reduce hours and take leave) during cancer treatment, which can further strain financial resources.9,10 Given associations between financial hardship and poor survival and quality of life outcomes,11,12 it is critical to better understand financial hardship experienced by patients and caregivers during immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.13

The overall goal of this study was to gather patient-reported data to direct priorities for supportive care research and service development for the growing number of patients with mNSCLC treated with immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy in clinical practice. The primary aim was to characterize unmet SCNs and financial hardship. A secondary aim was to estimate the prevalence of patient and caregiver employment reduction because of cancer and their relation to patient financial hardship. Based on prior work showing a relation between patient employment reduction and increased financial hardship,14 we hypothesized both patient and caregiver employment reductions would be associated with increased patient financial hardship. This is among the first inquiries of this kind in patients with mNSCLC.

METHODS

Study Design

The methods of this cross-sectional study are described in detail elsewhere.15 Briefly, from October 2017 to July 2018, we recruited patients with mNSCLC undergoing routine immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy in an academic medical center to complete a one-time survey.

Participants

Eligibility criteria included (1) histologically or cytologically documented non–small-cell lung cancer stage IV (de novo or recurrent metastatic per AJCC 7th edition staging16); (2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0-3 or Karnofsky performance status 60-100; (3) receipt of immunotherapy with or without chemotherapy; and (4) ability to provide informed consent in English. This study was approved by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (#46256), Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center (#01517), and University of Kentucky Medical Institutional Review Board (#56408).

Measures

The protocol has previously been described.15 Patients reported demographic information. Clinical data (eg, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, lung cancer diagnosis, and treatment information) were obtained from the medical record. Self-reported health insurance options included health insurance marketplace, Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance (employer-provided), private insurance (purchased directly), Veterans/Military, “I don't have any health insurance,” and other. Patients who reported Medicare and private insurance were coded as privately insured; Medicaid plus another insurance type were coded as Medicaid. Patients were asked to report their employment status both at the time their cancer was diagnosed and currently. Patients reported on the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: Experiences with Cancer Survivorship Supplement (MEPS-ECSS)17 item, “Since the time you were first diagnosed with cancer, has any friend or family member provided care to you during or after your cancer treatment?” (yes or no)9 to determine whether they had a caregiver.

Unmet SCNs

The SCNs Survey Short Form 34 consists of 34 items asking about level of help needed in the past month.18 Responses are provided on a divided 5-point Likert scale (no unmet need indicated by 1 = not applicable or 2 = satisfied; unmet need indicated by 3 = low need, 4 = moderate need, or 5 = high need). The measure contains five domains: health system and information, patient care and support, physical and daily living, psychological, and sexual. Items were dichotomized (1 or 2 = no unmet need; 3-5 = unmet need). We evaluated the proportion of patients endorsing at least one unmet need in each domain and reported the frequency and proportion of each unmet need.

Financial Hardship

We administered multiple instruments and items related to financial hardship and conceptualized them into three domains of material, psychological, and behavioral-related financial hardship.19

Primary financial hardship outcomes.

We were primarily interested in MEPS-ECSS17 items used in prior research to describe material, psychological, and behavioral aspects of financial hardship.20-24 Material hardship was indicated by loss of savings or borrowing money or going into debt (ie, by answering yes to either of these MEPS-ECSS items17: “Have you or anyone in your family had to borrow money or go into debt because of your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment?” and “Have you or your family had to make any other kinds of financial sacrifices because of your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment: used savings set aside for other purposes such as retirement, education, etc?”). Psychological hardship was indicated by worry about financial stability (ie, by answering yes to this item17: “Have you ever worried about your family's financial stability because of your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effect of that treatment?”). Behavioral hardship was indicated by answering yes to any of the following coping behaviors from this item17: “Have you or your family had to make any other kinds of financial sacrifices because of your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment: delayed large purchases, reduced spending on the basics, reduced spending on vacation or leisure activities, made a change to a living situation such as sold, refinanced, or moved?” (check all that apply).

Additional financial hardship measures.

In addition to these primary indicators of financial hardship, we administered further items and instruments relevant to financial hardship. To aid comparison with other research,20-24 these items were not included as indicators of financial hardship domains. We assessed out-of-pocket costs, financial distress, and health insurance worry. Out-of-pocket costs were assessed with MEPS-ECSS item17: “Because of your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment, did you have any costs you had to pay out of your own pocket in the following categories: medications, medical equipment, etc; transportation; lodging; child care; home or respite care?” (check all that apply). Financial distress was assessed with the 11-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness—Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (FACIT-COST).25 Items such as “I worry about the financial problems I will have in the future as a result of my illness or treatment” were responded to on a scale of 0 = not at all to 4 = very much. Scores were calculated following the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness scoring procedures such that a higher score represents less financial distress. Internal consistency in this sample was good (α = .84). Worry about health insurance was assessed with the MEPS-ECSS item17: “Have you ever been concerned about losing your health insurance because of your cancer?” (yes or no).

Patient and Caregiver Employment Reductions Because of Cancer

We compared patient-reported employment status at the time of cancer diagnosis to survey time to derive employment reduction. Patients who went from working either full time or part time at the time of cancer diagnosis to any of the following categories—temporary or long-term disability; homemaker; unemployed; permanently unable to work; or retired—or who went from full time at diagnosis to part time at the time of the survey were considered to have reduced employment.

We assessed caregiver employment reduction with an item from the MEPS-ECSS17: “Because of your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment, did any of your caregivers ever take extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or make a change in their hours, duties, or employment status?” (yes or no).

Analysis

We computed means, medians, and standard deviations (SDs) (for continuous or interval variables) and percentages (for categorical variables). Bivariate tests compared patients within strata of caregiver cancer-related employment change on financial hardship and financial distress. Chi-square tests (or Fisher's exact test when indicated by small cell size) were used for statistical comparisons of categorical variables and two-sample t-tests were used for comparisons of continuous or interval variables. We used a two-tailed α of .05. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

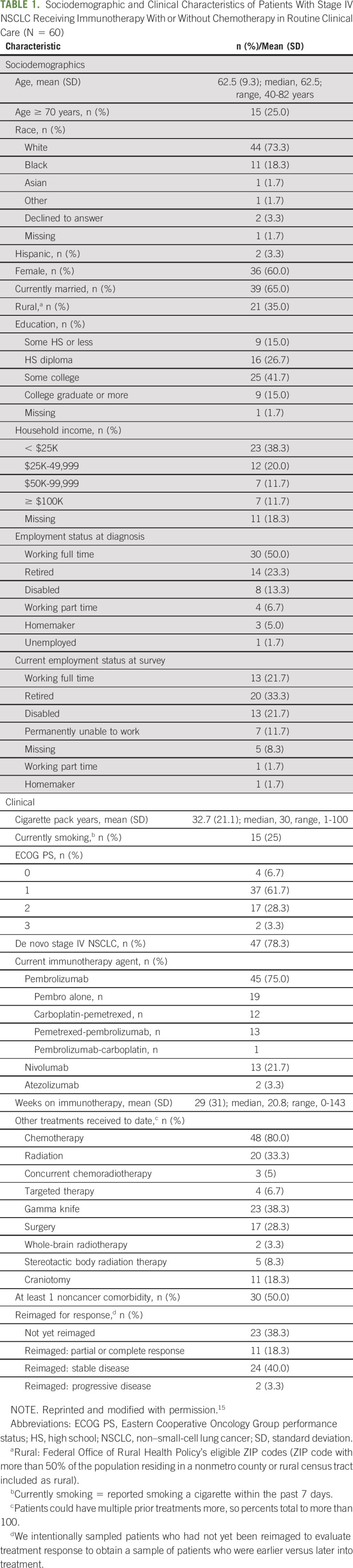

Sixty of the 67 eligible and approached patients consented (90%). Reasons for refusal and detailed sociodemographic and clinical information for the study sample have been previously described.15 See Table 115 for study sample details.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Stage IV NSCLC Receiving Immunotherapy With or Without Chemotherapy in Routine Clinical Care (N = 60)

Unmet SCNs

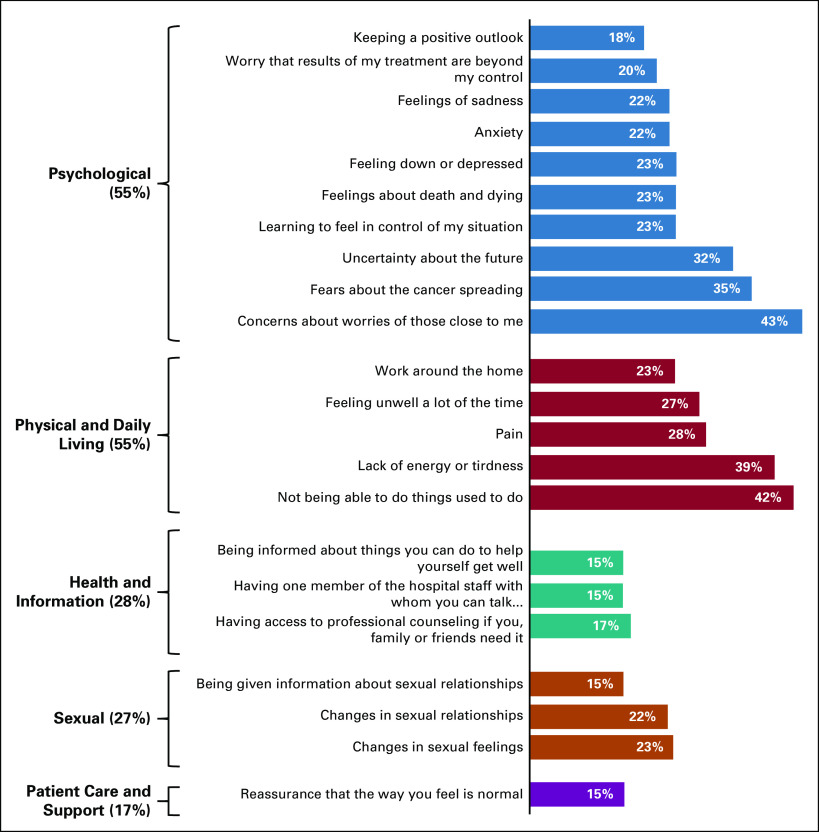

On average, patients reported 6.5 (SD = 8.4) unmet SCNs, with a range of 0 (n = 18) to 30 (n = 1; median = 3). See Figure 1 for domains of unmet needs and the frequency of needs within each domain unmet for at least 15% of our sample. The most common domains with at least one unmet need were psychological (55%) and physical or daily living (55%). Considering all items within all domains, the most common unmet SCNs were concern about the worries of people close to them (43%) and concern about not being able to do things they used to do (42%). More than 25% reported the following unmet needs: lack of energy or tiredness (39%), fears about cancer spreading (35%), uncertainty about the future (32%), pain (28%), and feeling unwell a lot of the time (27%). Concerns about work around the home, learning to feel in control, feelings about death and dying, and feeling down or depressed, anxious, or sad were also common (22%-23%).

FIG 1.

The proportion of patients endorsing at least one unmet need in each domain from the Supportive Care Needs Survey and items within each domain endorsed by at least 15% of patients.

Financial Hardship

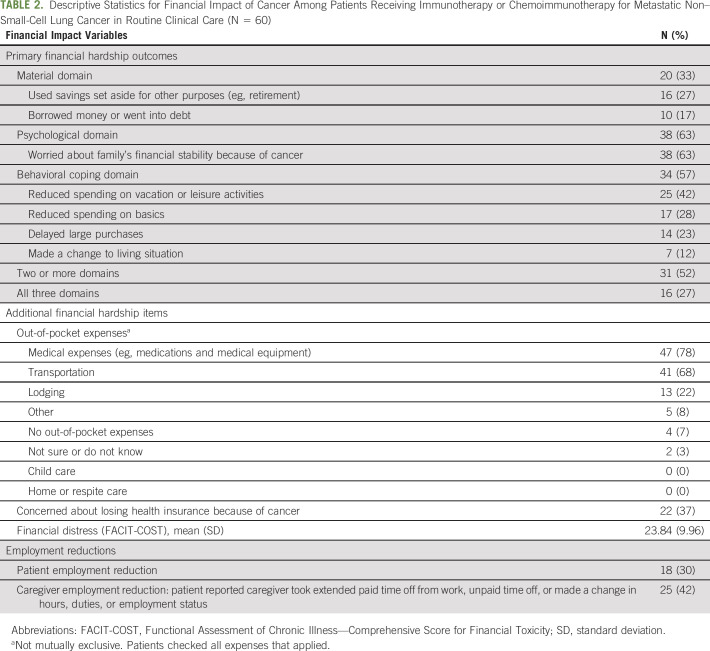

Primary financial hardship outcomes.

Table 2 shows the proportion of patients reporting financial hardship in each domain of the MEPS-ECSS indicators (material, psychological, and behavioral), individual hardship items reported (eg, going into debt and refinancing), and the proportion reporting hardship in multiple domains. Sixty-three percent reported psychological hardship, 57% reported behavioral hardship, and 33% reported material hardship (Table 2). More than half (52%) reported hardship in at least two of the three domains; 27% reported hardship in all three domains (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Financial Impact of Cancer Among Patients Receiving Immunotherapy or Chemoimmunotherapy for Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer in Routine Clinical Care (N = 60)

Additional financial hardship items.

Only 7% of patients reported no out-of-pocket expenses. The most common out-of-pocket expenses were medical (78%), followed by transportation (68%), and lodging (22%; Table 2; outcomes not mutually exclusive). More than a third of patients were worried about losing their health insurance because of cancer (37%). Regarding financial distress, the average FACIT-COST score was 23.84 (SD = 9.96; median = 26), with a range of 0 (n = 3) to 42 (n = 1).

Patient and Caregiver Employment Reductions and Relation to Financial Hardship

Patient employment reduction.

See Table 1 for patient employment status at cancer diagnosis and at survey.

Of the 30 patients employed full time at cancer diagnosis, 13 (43%) were still employed full time at survey time, three (10%) did not report employment status at survey time, and the remaining 14 of the 30 (47%) reported a change indicating fewer hours worked (10 disabled; one part time; and three retired). Of the four patients employed part time at diagnosis, all four reported reduced employment at survey time—one disabled and three retired. Thus, 18 patients (30% of sample) reduced employment after diagnosis.

The proportion of patients who reported at least two domains of financial hardship did not differ between patients who did and did not reduce employment (56% v 46% respectively, P = .50). The proportion who reported all three domains of financial hardship was also not significantly different between patients who did and did not reduce employment after diagnosis (33% v 24% respectively, P = .53). Patients who reduced employment did not report significantly more financial distress measured by the FACIT-COST (mean, SD for those who reduced employment = 21.6, SD = 11.8 v mean = 25.3, SD = 9.3 for those without; P = .21).

Caregiver employment reduction (eg, time off, change in hours, duties, or employment status).

Forty-two percent of patients reported their caregiver had reduced employment because of cancer (Table 2). Patients whose caregivers had reduced employment were more likely to endorse at least two domains of financial hardship compared with patients whose caregivers had not (68% v 40% respectively, P = .03). Similarly, patients whose caregivers had reduced employment were more likely to report all three domains of financial hardship compared with those whose caregivers had not (52% v 8%, respectively, P < .001). Patients reporting caregiver employment reduction also reported more financial distress measured by the FACIT-COST (mean, SD for those with a caregiver employment change = 19.64, SD = 11.95 v mean = 26.81, SD = 7.05 for those without; P = .01).

Patient and caregiver employment reductions were related. Seventy-two percent of patients who reduced employment after cancer diagnosis reported caregiver employment reduction, whereas 32% of patients who did not reduce employment reported a caregiver employment reduction (P = .005).

DISCUSSION

Immunotherapy with or without chemotherapy is now standard of care for mNSCLCs without sensitizing mutations. This is among the first studies to describe unmet needs and financial hardship among patients with mNSCLC on these new regimens. Results indicate that supportive care interventions for patients with mNSCLC are needed to address concerns about the impact of cancer on loved ones, daily activities and roles, worry and uncertainty about the future, and financial hardship.

Consistent with research prior to immunotherapy,26-29 unmet needs were most prevalent in the psychological (55% our sample v 66%-78% prior research26,27) and physical and daily living domains (55% v 58%-80%26,27). Common concerns were similar to previous lung cancer studies and included worry about loved ones (43% v 38%-42%27,29), fear about cancer spreading (35% v 52%-67%27,29), uncertainty about the future (32% v 44%-64%27,29), activity restrictions (42% v 37%-62%26,27,29), and fatigue (39% v 48%-75%26,27,29). Many patients reported need for access to counseling (17% v 14%-25%27,29). Our study design and the clinical heterogeneity (ie, stage and treatment status) of previous studies26,27,29 limit our ability to directly compare SCNs in patients treated with immunotherapy versus chemotherapy. However, the prevalence and types of unmet care needs reported suggest a role for several supportive care services for patients and caregivers during immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy for mNSCLC, including navigation and social work to identify resources and services, rehabilitation to address functional concerns, and palliative and mental health providers to address psychological and physical concerns.

To date, most data on patient experiences of financial hardship in cancer have come from the MEPS or the LIVESTRONG foundation surveys in samples with limited lung cancer patient representation. Compared to estimates from these surveys,14,22,30 more patients in our sample reported material, psychological, and behavioral hardship (eg, in our sample, 17% had gone into debt or borrowed money v 6%-7%22; 27% had used savings v 19%14). Despite these findings, the mean Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) score in our sample was higher than in the COST validation study,25 suggesting our sample was experiencing less financial hardship. Importantly, the COST validation study—while including patients with advanced-stage cancer—required patients to have been on treatment for at least 2 months. By contrast, many patients in this study started treatment within the past 2 months. Several patients in who were just starting treatment (ie, cycle 1) commented on the survey that the FACIT-COST was difficult to complete because they did not yet know the financial impact. This heightens concern regarding the prevalence of patients' worry about family financial stability, use of savings, debt, and fear of losing insurance. It also raises the importance of assessing financial hardship throughout cancer treatment.

Our results suggest that caregiver employment changes should be a part of screening and intervention for financial hardship. In this sample, caregiver employment reduction was associated with patient-reported financial hardship and financial distress. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report this association. Health insurance worry was also common. Ensuring adequate insurance coverage, including during patient or caregiver employment changes, is critical to mitigate financial hardship and its effects.31,32 Financial navigation may be a promising12,33-35 and essential intervention to incorporate into mNSCLC patient care, although policy changes, including financial support policies for caregivers (eg, compensating caregivers for providing care, income tax credits, and partially paid leave of absence from work) may also be needed.36

Study findings have implications for future research. First, the prevalence of patients' worry about their loved ones, coupled with the association between caregiver employment change and patient-reported financial hardship, underscores the need to assess both patient-reported and caregiver-reported outcomes. Second, conceptual frameworks of financial hardship should note caregiver employment changes as an additional pathway to patient-reported financial hardship.37 Caregivers are often the primary wage earners during cancer treatment38; loss of their income may be a significant risk factor for financial hardship. Finally, longitudinal studies characterizing the trajectory of patient-reported and caregiver-reported SCNs throughout treatment are a critical next step. Most studies of SCNs in lung cancer are cross-sectional,28 yet needs could shift in response to treatment and disease events (eg, disease progression).

This study is limited by a small sample from one academic medical center. The cross-sectional design and inclusion of clinically heterogeneous patients (eg, time on treatment and prior treatment) prohibits attributing unmet needs and financial hardship to immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy. We did not assess caregiver outcomes directly, caregiver relation to patient, or intensity of caregiving role. Furthermore, the wording of the caregiver cancer-related employment question precluded conclusions regarding the exact nature of caregiver employment reduction (paid time off v reducing hours v changing jobs). Study strengths include a focus on a new treatment regimen in an understudied cancer population; use of an established typology of financial hardship19 to guide assessment; as well as a clinically well-described sample with respect to stage, histology, prior treatments, current oncologic agent, comorbidities, and time on treatment.15 This will aid comparison with future mNSCLC samples.

In conclusion, the potential for prolonged survival with metastatic disease, coupled with multiple unmet care needs and prevalent financial hardship, highlights the need for systematic, routine assessment and delivery of appropriate resources (eg, nonhospice palliative care, rehabilitation, social work, and financial navigation) to address mNSCLC patient and caregiver care needs.

Thomas W. Lycan

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Incyte

Jimmy Ruiz

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca, Genentech

Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Roche, BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, ER Squib

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche

Stefan C. Grant

Employment: TheraBionic

Leadership: TheraBionic

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: TheraBionic

Research Funding: Genentech Mypath, Loxo, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Rafael Pharmaceuticals, Guardant Health

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Florence Healthcare

W. Jeffrey Petty

Consulting or Advisory Role: Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbvie

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Dava Oncology

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

SUPPORT

Supported by the Lung Cancer Initiative of North Carolina Research Fellow Grant (Dr Steffen [L.E.M.]) and the Wake Forest CTSA Grant UL1TR001420. L.E.M. was supported by NCI R25CA122061 (PI: Avis) and R03CA235171. J.L.B. was supported by K07 CA181351. This study was also supported by the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest University (CCCWFU; P30 CA012197) and University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center (P30 CA177558). C.L.N.'s work on this manuscript was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through KL2TR001421.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Laurie E. McLouth, Chandylen L. Nightingale, Jean A. McDougall, Jennifer Gabbard, Jimmy Ruiz, Arthur W. Blackstock, W. Jeffrey Petty, Kathryn E. Weaver

Financial support: Laurie E. McLouth

Provision of study materials or patients: Jimmy Ruiz, Arthur W. Blackstock, Stefan C. Grant, W. Jeffrey Petty

Collection and assembly of data: Laurie E. McLouth

Data analysis and interpretation: Laurie E. McLouth, Beverly J. Levine, Jessica L. Burris, Jean A. McDougall, Thomas W. Lycan, Michael Farris, Stefan C. Grant, Kathryn E. Weaver

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Unmet Care Needs and Financial Hardship in Patients With Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer on Immunotherapy or Chemoimmunotherapy in Clinical Practice

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Thomas W. Lycan

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Incyte

Jimmy Ruiz

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca, Genentech

Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Roche, BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, ER Squib

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche

Stefan C. Grant

Employment: TheraBionic

Leadership: TheraBionic

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: TheraBionic

Research Funding: Genentech Mypath, Loxo, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Rafael Pharmaceuticals, Guardant Health

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Florence Healthcare

W. Jeffrey Petty

Consulting or Advisory Role: Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbvie

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Dava Oncology

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.David SE, Douglas EW, Charu A, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: Non–small cell lung cancer, version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 17:1464–14722019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlesi F, Garon EB, Kim DW, et al. Health-related quality of life in KEYNOTE-010: A phase II/III study of pembrolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated advanced, programmed death ligand 1-expressing NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 14:793–8012019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahmer JR, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Health-related quality-of-life results for pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced, PD-L1-positive NSCLC (KEYNOTE-024): A multicentre, international, randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18:1600–16092017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bordoni R, Ciardiello F, von Pawel J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in OAK: A phase III study of atezolizumab versus docetaxel in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 19:441–449.e42018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reck M, Taylor F, Penrod JR, et al. Impact of nivolumab versus docetaxel on health-related quality of life and symptoms in patients with advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer: Results from the CheckMate 017 study. J Thorac Oncol. 13:194–2042018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garassino MC, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following pembrolizumab or placebo plus pemetrexed and platinum in patients with previously untreated, metastatic, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-189): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21:387–3972020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy D, Dhillon HM, Lomax A, et al. Certainty within uncertainty: A qualitative study of the experience of metastatic melanoma patients undergoing pembrolizumab immunotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 27:1845–18522019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotter J, Spencer JC, Wheeler SB.Financial toxicity in advanced and metastatic cancer: Overburdened and underprepared. J Oncol Pract. 15:e300–e3072019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Moor JS, Dowling EC, Ekwueme DU, et al. Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Surviv. 11:48–572017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan Y, Gao X, Mehta S, et al. Indirect costs associated with metastatic breast cancer. J Med Econ. 16:1169–11782013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith GL, Lopez-Olivo MA, Advani PG, et al. Financial burdens of cancer treatment: A systematic review of risk factors and outcomes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 17:1184–11922019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lentz R, Benson AB, III, Kircher SJ.Financial toxicity in cancer care: Prevalence, causes, consequences, and reduction strategies. J Surg Oncol. 120:85–922019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yousuf Zafar SJ.Financial toxicity of cancer care: It's time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 108:djv370.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han X, Zhao J, Zheng Z, et al. Medical financial hardship intensity and financial sacrifice associated with cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 29:308–3172020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steffen McLouth LE, Lycan TW, Levine BJ, et al. Patient-reported outcomes from patients receiving immunotherapy or chemo-immunotherapy for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in clinical practice. Clin Lung Cancer. 31:255–2632020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Carducci MA, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yabroff KR, Dowling E, Rodriguez J, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) experiences with cancer survivorship supplement. J Cancer Surviv. 6:407–4192012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C.Brief assessment of adult cancer patients' perceived needs: Development and validation of the 34-item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34). J Eval Clin Pract. 15:602–6062009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, et al. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 109:djw205.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 34:1732–17402016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odahowski CL, Zahnd WE, Zgodic A, et al. Financial hardship among rural cancer survivors: An analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Prev Med. 129:105881.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Jr, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: Findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 34:259–2672016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer. 125:1737–17472019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhiyuan Z, Ahmedin J, Reginald T-S, et al. Worry about daily financial needs and food insecurity among cancer survivors in the United States. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 18:315–3272020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient‐reported outcome: The validation of the Comprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer. 123:476–4842017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders SL, Bantum EO, Owen JE, et al. Supportive care needs in patients with lung cancer. Psychooncology. 19:480–4892010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giuliani M, Milne R, Puts M, et al. The prevalence and nature of supportive care needs in lung cancer patients. Curr Oncol. 23:258.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maguire R, Papadopoulou C, Kotronoulas G, et al. A systematic review of supportive care needs of people living with lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 17:449–4642013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitch MI, Steele R.Supportive care needs of individuals with lung cancer. Can Oncol Nurs J. 20:15–222010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekwueme DU, Zhao J, Rim SH, et al. Annual out-of-pocket expenditures and financial hardship among cancer survivors aged 18-64 years—United States, 2011-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 68:494–4992019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yabroff KR, Reeder-Hayes K, Zhao J, et al. Health insurance coverage disruptions and cancer care and outcomes: Systematic review of published research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 112:671–6872020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao J, Han X, Nogueira L, et al. Health insurance coverage disruptions and access to care and affordability among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 29:2134–21402020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadigh G, Gallagher K, Obenchain J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program in brain cancer patients. J Am Coll Radiol. 16:1420–14242019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wheeler S, Rodriguez-O'Donnell J, Rogers C, et al. Reducing cancer-related financial toxicity through financial navigation: Results from a pilot intervention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 29:694.2020 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kircher SM, Yarber J, Rutsohn J, et al. Piloting a financial counseling intervention for patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract. 15:e202–e2102019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Alliance for Caregiving . Cancer Caregiving in the US: An Intense, Episodic, and Challenging Care Experience. Bethesda, MD: National Alliance for Caregiving; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board PDQ financial toxicity and cancer treatment https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/managing-care/track-care-costs/financial-toxicity-pdq, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradley CJ.Economic burden associated with cancer caregiving. Semin Oncol Nurs. 35:333–3362019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]