Abstract

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is a comprehensive technical tool to analyze intracellular and intercellular interaction data by whole transcriptional profile analysis. Here, we describe the application in biomedical research, focusing on the immune system during organ transplantation and rejection. Unlike conventional transcriptome analysis, this method provides a full map of multiple cell populations in one specific tissue and presents a dynamic and transient unbiased method to explore the progression of allograft dysfunction, starting from the stress response to final graft failure. This promising sequencing technology remarkably improves individualized organ rejection treatment by identifying decisive cellular subgroups and cell-specific interactions.

Keywords: Single-cell RNA sequencing, Transplant rejection, Immune cell interactions, Transcriptional profiling, 10× Genomics chromium

Background

The demand for organs due to end-stage organ failure is permanently increasing. The best solution is autologous transplantation, enabled by patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. This approach is currently envisaged for single cells and basic cellular units such as islets. Tissue engineering is being optimized as one solution for larger organs. However, this option is not realistic presently. Xenotransplantation could soon become available clinically and an alternative backup for allotransplantation. However, both will depend on matching grafts and require immune suppression. The importance of understanding immune reactions, identifying cellular subtypes involved in graft acceptance and tolerance induction and identifying early indicators for rejection mechanisms require detailed immune cell profiling.

The immune system is a complex biological network comprising multiple layers of orchestrated genes, proteins and cells. In response to the challenge of pathogens or transplants, the immune system triggers various interactions between immune cells and other cells, provoking specific responses [1]. Innate and adaptive immune cells interact to ensure tissue protection according to functional requirements. Disruption of immune system homeostasis causes transplant rejection [2, 3]. Although inhibition of acute rejection has improved significantly in the past two decades, long-term rejection and immunosuppression can lead to high morbidity and mortality, and chronic transplant rejection can cause irreversible damage to the graft [4, 5]. The most common clinical acute rejection is mainly mediated by cellular responses, while hyperacute rejection and chronic rejection are mainly mediated by humoral immunity. The transplant rejection mechanism is an immunological reaction that recognizes foreign molecules of the donor cells, triggering attack and destruction. Various immunological factors are involved in acute and chronic rejection, including human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch, donor-specific antibodies and non-immune factors (e.g., donor age, infection, and immunosuppressive drug toxicity) [6, 7].

Assessing the immune reaction

Cellular and molecular assays to measure immune cell differentiation, cellular function and antigen specificity contribute to solving important problems in immune-mediated transplant rejection. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) is used for post-transplantation immune surveillance to identify cells of the immune system by detecting surface marker expression or intracellular proteins, including cytokines. This tool has been supplemented by in situ histological tests [8, 9]. However, histological diagnosis may miss subtle alterations in individual patients, which are essential for rejective pathology [10]. Therefore, the combination of transcript sets and histological diagnosis of tissue samples is used to predict antibody-mediated or cellular rejections [11, 12]. Additionally, bulk RNA sequencing of allograft biopsies is a method to determine gene-specific single-nucleotide variants of donors and recipients [13]. Microarray technology has been used to study the pathogenesis of transplant rejection processes. For example, Roedder et al. [14] used microarray technology to determine a test set of 17 relevant genes to predict renal rejection. Each of these approaches provides valuable insights. However, they are subject to limitations due to the complex immune rejection response. Furthermore, extensive analysis cannot resolve phenotypic heterogeneity and distinguish the gene profile of donors and recipients in mixed cell populations [15]. Even with the application of Cytometry by Time of Flight (CyTOF), it remains challenging to assess a truly unbiased dataset of a single cell, a process that requires single-cell resolution [16]. Among single-cell profiling methods, scRNA-seq comprehensively measures the transcriptional expression of bulk cells [1, 17] and quantitatively analyzes all transcripts expressed in a single cell, providing an unbiased strategy to identify and characterize different cell populations [18–20].

This review discusses the development and application of scRNA-seq in organ transplantation. This cutting-edge technology will improve immunotherapies and help to predict recipient outcomes.

Sample harvest and tissue processing

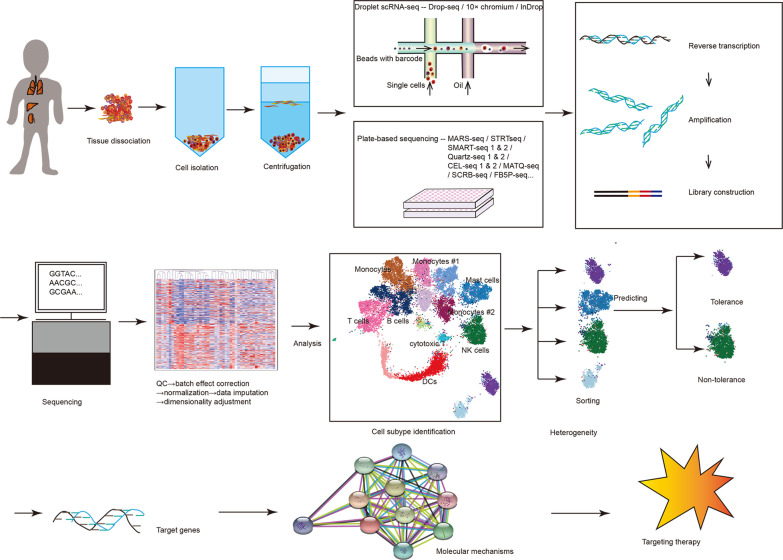

The entire process starting with sample isolation to the final evaluation of scRNA-seq data is summarized in Fig. 1. The first step of scRNA-seq analysis is the dissociation of the graft tissue, which is obtained in most cases by biopsies. The currently used protocols were developed and improved over decades, and each has its strengths and weaknesses. For transplanted organs, laser capture microdissection, digestion or enzyme-related approaches, followed by density gradient centrifugation or fluorescence-activated cell sorting are used. Tissue dissociation is more difficult to implement for frozen samples, e.g., those of the liver [21]. In particular, for liver samples, a different sensitivity to cell death caused by the dissociation step may result in bias because hepatocytes die very fast, while other cells become activated during tissue dissociation, indicating a transcriptional stress response. Macparland et al. [22] developed a milder approach to reduce the cell damage rates by maintaining the tissue at 4 °C during all steps, including collagenase perfusion. Wang et al. [23] used a hypothermic strategy for kidney preservation for up to 4 days for scRNA-seq analysis. Recently, Guillaumet-Adkins et al. [24] published an improved method for sample preservation, gradual freezing by 1 ℃ per minute to -80 ℃, that does not change the transcriptional profiles and makes cryopreserved cells and tissues applicable for scRNA-seq. However, frozen tissues cannot be processed like fresh tissues. Tissue dissociation leads to the loss of spatial and anatomical information for cells, and the precise location of each cell should not be ignored. To address this issue, RNA probes identifying cellular transcriptional organization [25] or spatial transcriptomic protocols [26] are both helpful alternative methods.

Fig. 1.

Steps of scRNA-seq to analyzing organ rejection. After biopsies of graft tissues, cells are isolated and can be used for droplet- or plate-based sequencing approaches. After batch effect correction, normalization, data imputation and dimensionality adjustments, specific cellular subtypes can be identified. Analysis of heterogeneity and prediction of tolerance is used to identify target genes and molecular interactions that are the basis for gene therapy approaches and long-term graft acceptance. QC quality control; DCs dendritic cells

Single-cell methods

The next steps after tissue dissociation include RNA capture, reverse transcription, RNA sequencing, and library construction. Selection of a suitable sequencing method is challenging because several methods exist, such as CEL-seq2, Drop-seq, MARS-seq, MATQ-seq, Quartz-seq, SCRB-seq, Smart-seq, Smart-seq2, Drop-seq, FB5P-seq, SPLIT-seq, and DNBelab C4 [27–30]. We summarize the most commonly used scRNA-seq methods in Table 1 according to their capturing format, cDNA amplification, sequencing method, transcript coverage advantages and limitations. Microfluidic technologies for scRNA-seq involve droplet-based and plate-based technologies. Amplification is performed by PCR for Smart-seq [31, 32] and Quartz-seq [33, 34] and in vitro transcription, generating RNA in vitro, e.g., by InDrop [35] and CEL-seq [36, 37]. Drop-seq [38], InDrop [35], and CEL-seq [36, 37] incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) into cDNA. A UMI is a short sequence barcode to detect and quantify transcripts. These molecular barcodes uniquely tag each molecule in a sample library and reduce quantitative and error biases introduced by amplification. Smart-seq2, Quartz-seq, and MATQ-seq produce almost full-length sequencing data, while others (e.g., CEL-seq and Drop-seq) only capture the 3'-end sequence or 5'-sequence (e.g., FB5P-seq and STRT-seq) [10, 30, 39, 40]. Each platform provides multiple and specific but not completely comprehensive advantages in data capture. The reduction of mRNA amplification noise by CEL-seq2, InDrop, Drop-seq, MARS-seq, and SCRB-seq is a favorable feature that makes these platforms preferable. However, MARS-seq, SCRB-seq, and particularly Smart-seq2 platforms capture more genes using the same number of cells, making them preferable for relatively low quantities [41]. Drop-seq analyzes thousands of individual cells simultaneously without losing the original transcript [38]. Compared with other widely used single-cell RNA sequencing platforms (such as Smart-seq2), 10× Genomics Chromium is a more cost-effective and time-efficient system. This platform generates droplets and forms a single-cell suspension. Additionally, it can process many cells and detect even rare cell types or transcripts [42] by combining one of the following methods: InDrop for rare cell populations [38] or CEL-seq for complex tissues containing multiple cell populations [36, 37]. Smart-seq increases the thermal stability of DNA base pairs [31, 32]. MATQ-seq is implemented on low-abundance genes and noncoding and non-polyadenylated RNA [43]. Quartz-seq is applied to detect the different cell cycle phases and transcriptome heterogeneity. SCRB-seq is used for heterogeneous populations [33, 34]. FB5P-seq [30] and T-cell receptor repertoire sequencing (TCR-seq) [44] are used to identify the repertoire and diversity of BCRs and TCRs. STRT-seq tracks the cell origin efficiency without quantitative bias against long transcripts. One of the common disadvantages is the limited throughput and read coverage, e.g., by Smart-seq 1 and 2 [31, 32]. Another is the requirement for skilled technicians, e.g., for Quartz-seq 1 and 2 [33, 34]. Because each method has weaknesses (Table 1), investigators must choose a platform according to their specific interests.

Table 1.

Comparison of scRNA methods

| Method | Capture format | cDNA amplification | Transcript coverage | Molecule identifier | Strength | Weakness | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drop-seq | Droplets | PCR | 3′ end | UMI | For individual cells; simultaneous analysis without losing the original transcript; high throughput, lower costs and reduction of the mRNA amplification noise | Only 3′ end is enabled for specific the amplification | [38] |

| 10× Genomics Chromium | Droplets | PCR | 3′ end | UMI | Increased throughput, cost effective and time efficient | Only 3′ end is enabled for specific amplification, efficiency losses | [45] |

| InDrop | Droplets | IVT | 3′ end | UMI | Detects rare cell populations; high throughput, low noise profile | Low cell capture efficiency | [35] |

| CEL-seq 1 & 2 | Plate | IVT | 3′ end | UMI | For complex tissues containing multiple cell populations; improved accuracy and higher sensitivity; reduces mRNA amplification noise | Low cell capture efficiency | [36, 37] |

| Smart-seq 1 & 2 | Plate | PCR | Full length | UMI | Increases thermal stability of DNA base pairs | Lower detection efficiency, limited throughput and read coverage | [31, 32] |

| MATQ-seq | Plate | PCR | Full length | NA | For low-abundance genes and noncoding and non-polyadenylated RNA; highly sensitive with quantitative detection efficiency | Low throughput | [43] |

| Quartz-seq 1 & 2 | Plate | PCR | Full length | NA (Quartz-seq), UMI (Quartz-seq 2) | For different cell cycle phases and transcriptome heterogeneity detection; high quantity and efficiency in limited sequence reads | Requires skilled technician | [33, 34] |

| SCRB-seq | Plate | PCR | 3′ end | UMI | For heterogeneous population identification; high throughput, low cost, simple steps, fewer potential biases, reduced mRNA amplification noise | Requires skilled technician | [46] |

| FB5P-seq | Plate | PCR | 5′ end | UMI | For BCR and TCR repertoire identification; cost and time effective; integrative analysis of transcriptome | 3′ end scRNA-seq protocols are not suitable | [30] |

| STRT-seq | Plate | PCR | 5′ end | UMI | Improves efficiency and tracking of cell origin; no quantitative bias against long transcripts | Technical variation | [47] |

| TCR-seq | Plate | PCR | 3′ end | NA | For T-cell diversity identification | No standardized thresholds, disparities between different studies | [44] |

| MARS-seq 1 & 2 | Plate | IVT | 3′ end | UMI | For in vivo transcriptional states in thousands of single cells; minimizes amplification bias | Requires skilled technician | [48] |

IVT In vitro transcription, UMI Unique molecular identifiers

Data analysis

Data analysis after sequencing generally comprises quality control (QC), batch effect correction, normalization, data imputation, dimensionality adjustment, subsequent expression analysis and cell subpopulation identification [39]. QC is required for high technical noise and low-quality data, which are often generated because of dead cells. Batch effects are caused by large-scale scRNA-seq datasets, samples prepared in different laboratories, even those based on the same protocol, and large data generated from separate technicians or different time points [49, 50]. They can cause systematic errors and differences among multiple transcriptional profiles. Thus, batch effect correction is vital to avoid this misinterpretation, and removing unwanted variation (RUV) is a good normalization strategy to adjust confounding technical effects [51]. Data normalization is necessary to adjust technical biases. Two types of normalization are used: sample normalization, which adjusts within-sample differences, and gene profile normalization, which eliminates gene expression biases. Data imputation is an effective strategy to insert substituted values into dropouts, eliminating the influence of missing data. Because of technological developments in scRNA-seq and bulk data generation with high dimensionalities, computational bioinformatics analysis is essential to process raw data. Automatic annotation methods such as the "SingleR" package [52], online databases [53] and gene expression markers [54] can be used for cell marker identification. The commonly used "SingleR" labels new cells from the scRNA-seq dataset based on similarity to the reference dataset of samples with known labels.

Challenges during data analysis involve multiple biases in the entire procedure and high dimensional datasets [55]. The possibility of low-quality data or dropouts in the scRNA-seq results, caused by low viability or dead cells, can lead to misinterpretation [56]. An optimal method can avoid false results to enable correct transcriptional interpretation (Table 2). "Seurat" is an R package designed for QC, analysis and exploration of scRNA-seq data to reduce some biases [54, 57]. To distinguish technical biases from biological signals, Bayesian Inference for Single-cell ClUstering and ImpuTing (BISCUIT) provides a discernible advantage for graphical algorithms. BISCUIT imputes dropouts and improves both clustering and normalization [58]. Using these tools, the data are clustered to reduce technical variations (amplification bias, sequencing depth, GC content, capture inefficiency, and RNA content variations [59]). Because scRNA-seq data contain many genes and cells in high dimensions, large-scale computational resources are required. T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) is an approach for high-dimensional data because of the computation time and potentially manifold embeddings for the same datasets from run to run [60]. PhenoGraph is also an algorithmic method used for partitions of high-dimensional data into distinct subgroups within complex tissues [61]. Dimensional reduction and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) are alternative methods for data analysis developed to project the data into lower dimensions and visualize cell clusters with high reproducibility without losing the properties of the original data [62]. Xu et al. described a new clustering algorithm of graph-based shared nearest neighbor (SNN)-Cliq implemented in Python and MATLAB software, considering the surrounding data points, including low-density region data and detecting more cell subtypes with high accuracy [63]. For zero-inflated data comprising an excessive number of zeros, zero inflated factor analysis (ZIFA) is a novel approach to reduce dataset dimensions [64]. "Harmony" is another R package with an efficient batch algorithm method to integrate multiple datasets and requires fewer computational resources. Korsunsky et al. [65] developed this method (https://github.com/immunogenomics/harmony) and applied it to large datasets integrated with spatial transcriptomics data.

Table 2.

Tools for scRNA-seq data analysis

| Challenge | Method | References |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple biases | "Seurat" is an R package designed for quality control, analysis, and exploration of scRNA-seq data | [54, 57] |

| BISCUIT provides the graphical algorithm and imputes dropouts, improving both clustering and normalization and reducing the technical biases from biological signals | [58] | |

| Dimension | tSNE, PhenoGraph and ZIFA are used for high dimensional data. UMAP and SNN project the data into lower dimensions | [59–64] |

| "Harmony" is an efficient batch algorithm method to integrate multiple datasets and requires fewer computational resources | [65] |

However, these algorithms are most commonly used for static analysis. Another promising means, considering a continuous transition between different cellular states, are the machine learning approaches listed in Table 3, Monocle [66], Monocle2 [67], TSCAN [68], Wishbone [69], Slingshot [70], Diffusion pseudotime software [71] and Wanderlust [72] allow the construction of trajectories of cells in dynamic gene regulation and explain normal physiological and pathophysiologic alterations of cellular subgroups in specific locations of the human body. Saelens et al. [73] concluded that Slingshot, TSCAN and Monocle2 exhibited better trajectory identification. Therefore, the combination of personalized medicine and artificial intelligence will become applicable in the near future [41]. This combination will provide a map of cells, considering temporal dynamics and spatial positioning by evaluating the pathological microenvironment, phase of the cell cycle and responses to clinical medication. For transplanted organs, selecting an optimized process for accurate subsequent analysis is highly recommended.

Table 3.

Tools for scRNA-seq trajectory inference

| Method | URL | References |

|---|---|---|

| Monocle | http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/monocle-release/ | [66] |

| Monocle2 | http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/monocle-release/ | [67] |

| TSCAN | https://github.com/zji90/TSCAN | [68] |

| Wishbone | https://github.com/ManuSetty/wishbone | [69] |

| Slingshot | https://github.com/kstreet13/slingshot | [70] |

| Diffusion Pseudotime Software | https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1038%2Fnmeth.3971/MediaObjects/41592_2016_BFnmeth3971_MOESM375_ESM.zip | [71] |

| Wanderlust | https://github.com/wanderlust/wanderlust | [72] |

Applications of scRNA-seq for transplantation

Currently, the main difficulties for successful transplantation comprise, among others, best-matched donor selection and a reduction in lifelong immunosuppression [74]. For transplant rejection, the latest advances in scRNA-seq provide an opportunity to fully reveal new cell types and states without result bias and RNA degradation [75]. Snapshots of the single-cell transcriptome exhibit various stages of immune differentiation and activation, while these stages are rarely synchronized among cells [76]. At single-cell resolution, it can describe immune cells, stromal cells and new cell subtypes that undergo immune rejection and further compare the unique characteristics of the signaling pathways between different cellular subgroups [57]. Here, we describe the advantages of scRNA-seq in the fields of kidney, liver, lung and hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation and for immunological applications.

Kidney transplantation

T cells play a crucial role in graft rejection. Most studies have focused on bulk methods based on biopsy samples without providing information about αβ chain pairing of T-cell receptors (TCRs) [77]. This lack can underestimate actual library differences and fails to reflect that T cells with the same TCR can exert opposite biological functions. ScRNA-seq technology overcomes the abovementioned limitations and brings library analysis a higher diversity [78]. ScRNA-seq detects T-cell subclones [79]. For example, Morris et al. [80] monitored donor-reactive T cells in patients with tolerant and non-tolerant kidney transplantation. Donor reactivity has been detected in patients with tolerance. The decrease in T-cell clones in non-tolerant patients did not show a reduced number of donor-reactive T cells. Contrary to data from tolerant patients undergoing standard immunosuppression, an expansion of donor-reactive T-cell clones was observed in peripheral blood [81–83]. Antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) in the kidney is not easily identified by histological diagnoses. However, a transcriptional expression profile can strengthen the diagnosis. AMR injury is the most common driver of late allograft loss [12, 84]. Several groups have performed scRNA-seq of kidney allograft undergoing AMR, where monocytes, B cells, plasma cells and T cells invade into the tissue [85] and donor endothelial cells (ECs) are the primary targets of the recipients’ humoral immune response [86, 87]. Thus, scRNA-seq provides a comprehensive understanding of subtle mechanisms in conceptualizing heterogeneous kidney rejection. Macrophages and T cells, activated in the recipient, significantly differ from the original populations in either the donor or recipient. Some of these immune cells exist for only a few days after transplantation, but macrophages can persist for several years [88]. Furthermore, immune cell populations residing in donor-derived tissues can be replaced by recipient cells, particularly during rejection [89]. Liu et al. [57] presented a novel heterogeneous profile of immune cells based on allograft biopsies and matching healthy kidneys by scRNA-seq, integrating the key alterations of molecular functions, establishing therapeutic surveillance for kidney allograft rejection and improving allograft survival [90]. They identified subclusters of cytotoxic T lymphocytes that exhibit a more proinflammatory role in renal allograft rejection, while activated B cells interacted with surrounding stromal cells, mostly emerging in allograft kidneys, leading to immune cell recruitment and an activated inflammatory response. Non-invasive urine or blood biomarkers are applicable for a limited group of pathologies [91], whereas invasive biopsies are used to profile non-circulating immune cells in transplant rejection, providing more diagnostic accuracy and prognostic biomarkers amenable to therapeutic tools [10, 85].

Liver transplantation

The interaction of immune cells and liver cells in a transplant setting is a key mechanism for liver tolerance induction [92]. ScRNA-seq can improve the hepatic immune cellular map in interpreting the specific CD4+ T-cell subgroup from other T cells in liver transplant rejection and tolerance [93]. Immune cells such as dendritic cells (DCs), T cells, and probably NK cells interact with liver sinusoidal ECs and hepatocytes, adding specific signaling molecules to generate a tolerogenic state. Apoptosis of infiltrating T cells may be critical for allograft tolerance [93, 94]. Despite possible tolerance induction after liver transplantation, human liver allografts are likely to be rejected without applying immunosuppressive drugs [95]. Approximately 10%-30% of allograft recipients are diagnosed with acute cellular rejection [96], likely due to T-cell-related immune responses [97]. Applying scRNA-seq may better elucidate the cellular immune responses in the liver allograft.

Lung transplantation

Using scRNA-seq to test single cells isolated from lung transplantation donors and lung fibrosis has revealed transcriptionally distinct populations of alveolar macrophages that express profibrotic genes in patients with pulmonary fibrosis [98, 99]. Some mesenchymal cell markers that play a role in Wnt/β-catenin signaling during lung regeneration and some previously described rare cell populations have been identified. These technologies can improve the diagnosis of patients with fibrosis after lung transplantation and can be used to identify patients most likely to benefit from targeted therapy and monitor their response during disease progression [100]. Mould et al. [101] assessed the cell populations between healthy samples and found highly conserved cellular heterogeneity in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells. By dynamically comparing the lungs of donors and recipients, persistent donor resident memory T cells are correlated with better clinical outcomes [102], providing a potential therapeutic tool for extended allograft survival.

HSC transplantation

To study the rejection of transplanted HSCs, Dong et al. [103] used scRNA-seq to obtain a transcriptome-based classification of 28 hematopoietic cell types. According to this classification, most transplanted HSCs are dedicated to transcriptional immunophenotypical multipotent progenitors (tMPP1). Transcriptional analysis and functional evaluation showed that the proliferation of transplanted cells is accompanied by a gradually decreased percentage of HSCs [104]. However, a balance between proliferation, differentiation and stem cell maintenance likely exists. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is the main complication of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) [105]. Acute GVHD is mediated by donor T cells [106]. TCR-seq, as a type of scRNA-seq, can clarify how acute GVHD occurs. Although donor T-cell pools have highly similar TCRs, the TCR repertoire after HCT is very specific to recipients. TCR recombination is highly stochastic and may not depend on evaluating the most expanded TCR clones in any single recipient but on the complex polyclonal architecture. These results can be used to guide clinical decisions to prevent or treat acute GVHD [78]. By analyzing skin and peripheral blood T cells using TCR-seq, host skin-resident T cells were found to have an unanticipatedly pathogenic impact on GVHD [107].

Immunological applications of scRNA-seq

ScRNA-seq identifies gene profiles of various cell populations. This technical tool avoids the weakness of bulk analysis, which is likely to miss cell-specific signatures [85]. It also improves the understanding of immune cell ontogeny and interaction with stromal cells in a given organ. The advantages of scRNA are maximized by its combination with databases or improvements by other techniques [such as single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq)] [108]. The Immune Cell Atlas (ICA) is an essential part of the international Human Cell Atlas initiative (https://www.humancellatlas.org/), which collects samples from patients who have undergone rejection response and evaluates different reaction stages using scRNA-seq technology. By visualizing the dynamic observation of cell processes, the subtle transcriptional differences among cell types can be qualitative. The rejection response, caused by specific gene regulation, provides robust target genes and molecular mechanisms to diagnose and treat transplant rejection and identify potential diagnostic markers [109, 110]. The limitations of scRNA-seq due to fresh tissue requirements, artifactual transcriptional biases and loss of fragile or low viability cells can be overcome by snRNA-seq, enabling the storage of frozen samples and analysis using a quality comparable to scRNA-seq [108, 111–113]. The latest developments in snRNA-seq, imaging technologies [such as single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)], proteomics (MIBI-TOF), and genomics all together provide benefits to further investigate cellular functions [114].

Classical immune cell characterization in different organs has limitations due to technologies such as microscopy and high-affinity antibody labeling. Additionally, conventional transcriptome studies may miss some essential immune cell subtypes [85]. ScRNA-seq is currently widely used in immunology to unravel the differentiation process of HSCs, resolve previously under recognized immune cellular heterogeneity, decipher the immune cellular repertoire and predict disease-related phenotypes [39, 115, 116]. ScRNA-seq can help identify HSC fate branch points during differentiation; for example, conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) rely on the abundance of Siglec‑H and Ly6C to determine the direction of cDC type 1 (cDC1) or cDC type 2 (cDC2) [117]. The myeloid progenitor cells that produce mast cells and eosinophils or monocytes and macrophages depend on the presence of GATA1 [118]. Jaitin et al. [119] performed scRNA-seq on DCs and found different states of bone marrow-derived and other immune tissue-derived cells. Using scRNA-seq, progenitor immune cells can be identified by analyzing transcriptional variations in immature bone marrow and mature resident immune cells of specific organs [22]. Many new types of immune cells were identified using scRNA-seq, which can analyze cell differentiation and cell lineages, including innate lymphocytes and lung interstitial macrophages [57]. Recent studies have shown the heterogeneity of hematopoietic progenitor cells with a mixed lymphoid phenotype using scRNA-seq. This technology can also be used to identify novel cell types in several diseases, for example, cancer diagnosis and efficacy evaluation. By analyzing circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from prostate cancer patients, Miyamoto et al. [120] found that CTCs are highly heterogeneous in gene expression. The special feature of CTCs is that they activate Wnt signaling, which increases resistance to drug therapy. By analyzing brain cells in Alzheimer’s disease, scRNA-seq also enables the identification of microglia and perivascular macrophages related to neurodegenerative diseases [121]. ScRNA-seq also improves the diagnosis of disease heterogeneity, such as identifying specific B-cell receptor signaling pathways and gene expression patterns in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Most adult B-cell lymphomas exhibit a B-cell phenotype at the germinal center (GC). By combining scRNA-seq, the mixed characteristics of B cells derived from GC and follicular lymphoma (FL) revealed unique transcription characteristics [122, 123]. In the future, organ transplantation single-cell sequencing will likely help further elucidate the pathogenesis of transplant rejection and initiate the development of clinical trials and the emergence of more effective drugs to reduce the immune response associated with transplant rejection, thereby improving the quality of life of patients and extending patient survival.

Conclusion

Taken together, scRNA-seq can accurately interpret gene expression data, recognize cell heterogeneity, including new cell types or subtypes, and take snapshots of gene expression during the transition of cells from one state to another. All data can be integrated to define the critical process of cell development and differentiation, reveal the key signaling pathways and understand the gene regulatory network that predicts immune function [124–127].

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Seq Health Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) for providing guidance on sequencing technologies.

Abbreviations

- AMR

Antibody-mediated rejection

- BISCUIT

Bayesian Inference for Single-cell ClUstering and ImpuTing

- cDC

Conventional dendritic cell

- CTC

Circulating tumor cell

- CyTOF

Cytometry by Time of Flight

- ECs

Endothelial cells

- FACS

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting

- FL

Follicular lymphoma

- GC

Germinal center

- GVHD

Graft-versus-host disease

- HCT

Hematopoietic cell transplantation

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- HSCs

Hematopoietic stem cells

- ICA

Immune Cell Atlas

- IVT

In vitro transcription

- QC

Quality control

- RUV

Remove unwanted variation

- scRNA-seq

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- SNN

Shared nearest neighbor

- SnRNA-seq

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing

- TCR-seq

T-cell receptor repertoire sequencing

- tMPP1

Transcriptional immunophenotypical multipotent progenitors

- tSNE

T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

- UMAP

Uniform manifold approximation and projection

- UMI

Unique molecular identifiers

- ZIFA

Zero inflated factor analysis

Authors' contributions

YW and JYW drafted the manuscript. KF and AS reviewed and supervised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ying Wang and Jian-Ye Wang have contributed equally to this review.

Contributor Information

Ying Wang, Email: ying.wang@wzw.tum.de.

Jian-Ye Wang, Email: jianye.wang@tum.de.

Angelika Schnieke, Email: angelika.schnieke@wzw.tum.de.

Konrad Fischer, Email: konrad.fischer@wzw.tum.de.

References

- 1.Hao S, Yan KK, Ding L, Qian C, Chi H, Yu J. Network approaches for dissecting the immune system. iScience. 2020;23(8):101354. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stubbington MJT, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Regev A, Teichmann SA. Single-cell transcriptomics to explore the immune system in health and disease. Science. 2017;358(6359):58–63. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingulli E. Mechanism of cellular rejection in transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(1):61–74. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-1020-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menon MC, Keung KL, Murphy B, O’connell PJ. The use of genomics and pathway analysis in our understanding and prediction of clinical renal transplant injury. Transplantation. 2016;100(7):1405–1414. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claeys E, Vermeire K. Immunosuppressive drugs in organ transplantation to prevent allograft rejection: mode of action and side effects. J Immunol Sci. 2019;3(4):14–21. doi: 10.29245/2578-3009/2019/4.1178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CLS, O’connell PJ, Allen RDM, Chapman JR. The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(24):2326–2333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Zoghby ZM, Stegall MD, Lager DJ, Kremers WK, Amer H, Gloor JM, et al. Identifying specific causes of kidney allograft loss. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(3):527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maguire O, Tario JD, Jr, Shanahan TC, Wallace PK, Minderman H. Flow cytometry and solid organ transplantation: a perfect match. Immunol Invest. 2014;43(8):756–774. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2014.910022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colvin RB. Antibody-mediated renal allograft rejection: diagnosis and pathogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(4):1046–1056. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malone AF, Wu H, Humphreys BD. Bringing renal biopsy interpretation into the molecular age with single-cell RNA sequencing. Semin Nephrol. 2018;38(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sellares J, Reeve J, Loupy A, Mengel M, Sis B, Skene A, et al. Molecular diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection in human kidney transplants. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(4):971–983. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halloran PF, Pereira AB, Chang J, Matas A, Picton M, De Freitas D, et al. Microarray diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplant biopsies: an international prospective study (INTERCOM) Am J Transplant. 2013;13(11):2865–2874. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thareja G, Yang H, Hayat S, Mueller FB, Lee JR, Lubetzky M, et al. Single nucleotide variant counts computed from RNA sequencing and cellular traffic into human kidney allografts. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(10):2429–2442. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roedder S, Sigdel T, Salomonis N, Hsieh S, Dai H, Bestard O, et al. The kSORT assay to detect renal transplant patients at high risk for acute rejection: results of the multicenter AART study. PLoS Med. 2014;11(11):e1001759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higdon LE, Schaffert S, Khatri P, Maltzman JS. Single cell immune profiling in transplantation research. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(5):1278–1287. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy AL. Transcriptional regulation in the immune system: one cell at a time. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1355. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giladi A, Amit I. Single-cell genomics: a stepping stone for future immunology discoveries. Cell. 2018;172(1–2):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neu KE, Tang Q, Wilson PC, Khan AA. Single-cell genomics: approaches and utility in immunology. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(2):140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen HI, Jin Y, Huang Y, Chen Y. Detection of high variability in gene expression from single-cell RNA-seq profiling. BMC Genom. 2016;17(Suppl 7):508. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2897-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clatworthy MR. How to find a resident kidney macrophage: the single-cell sequencing solution. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(5):715–716. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019030245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malone AF, Humphreys BD. Single-cell transcriptomics and solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2019;103(9):1776–1782. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macparland SA, Liu JC, Ma XZ, Innes BT, Bartczak AM, Gage BK, et al. Single cell RNA sequencing of human liver reveals distinct intrahepatic macrophage populations. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4383. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, Penland L, Gokce O, Croote D, Quake SR. High fidelity hypothermic preservation of primary tissues in organ transplant preservative for single cell transcriptome analysis. BMC Genom. 2018;19(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4512-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guillaumet-Adkins A, Rodriguez-Esteban G, Mereu E, Mendez-Lago M, Jaitin DA, Villanueva A, et al. Single-cell transcriptome conservation in cryopreserved cells and tissues. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1171-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Codeluppi S, Borm LE, Zeisel A, La Manno G, Van Lunteren JA, Svensson CI, et al. Spatial organization of the somatosensory cortex revealed by osmFISH. Nat Methods. 2018;15(11):932–935. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0175-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ståhl PL, Salmén F, Vickovic S, Lundmark A, Navarro JF, Magnusson J, et al. Visualization and analysis of gene expression in tissue sections by spatial transcriptomics. Science. 2016;353:78–82. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziegenhain C, Vieth B, Parekh S, Reinius B, Guillaumet-Adkins A, Smets M, et al. Comparative analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing methods. Mol Cell. 2017;65(4):631–43.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lafzi A, Moutinho C, Picelli S, Heyn H. Tutorial: guidelines for the experimental design of single-cell RNA sequencing studies. Nat Protoc. 2018;13(12):2742–2757. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0073-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munoz-Manchado AB, Bengtsson Gonzales C, Zeisel A, Munguba H, Bekkouche B, Skene NG, et al. Diversity of interneurons in the dorsal striatum revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing and PatchSeq. Cell Rep. 2018;24(8):2179–90.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attaf N, Cervera-Marzal I, Dong C, Gil L, Renand A, Spinelli L, et al. FB5P-seq: FACS-based 5-prime end single-cell RNA-seq for integrative analysis of transcriptome and antigen receptor repertoire in B and T cells. Front Immunol. 2020;11:216. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picelli S, Faridani OR, Björklund ÅK, Winberg G, Sagasser S, Sandberg R. Full-length RNA-seq from single cells using Smart-seq2. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(1):171–181. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picelli S, Björklund ÅK, Faridani OR, Sagasser S, Winberg G, Sandberg R. Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nat Methods. 2013;10(11):1096–1098. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasagawa Y, Nikaido I, Hayashi T, Danno H, Uno KD, Imai T, et al. Quartz-Seq: a highly reproducible and sensitive single-cell RNA sequencing method, reveals non-genetic gene-expression heterogeneity. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R31. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sasagawa Y, Danno H, Takada H, Ebisawa M, Tanaka K, Hayashi T, et al. Quartz-Seq2: a high-throughput single-cell RNA-sequencing method that effectively uses limited sequence reads. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1407-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein AM, Mazutis L, Akartuna I, Tallapragada N, Veres A, Li V, et al. Droplet barcoding for single-cell transcriptomics applied to embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2015;161(5):1187–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimshony T, Senderovich N, Avital G, Klochendler A, De Leeuw Y, Anavy L, et al. CEL-Seq2: sensitive highly-multiplexed single-cell RNA-Seq. Genome Biol. 2016;17:77. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0938-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashimshony T, Wagner F, Sher N, Yanai I. CEL-Seq: Single-cell RNA-Seq by multiplexed linear amplification. Cell Rep. 2012;2(3):666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, et al. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell. 2015;161(5):1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen G, Ning B, Shi T. Single-cell RNA-seq technologies and related computational data analysis. Front Genet. 2019;10:317. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kolodziejczyk AA, Kim JK, Svensson V, Marioni JC, Teichmann SA. The technology and biology of single-cell RNA sequencing. Mol Cell. 2015;58(4):610–620. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta RK, Kuznicki J. Biological and medical importance of cellular heterogeneity deciphered by single-cell RNA sequencing. Cells. 2020;9(8):E1751. doi: 10.3390/cells9081751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou A, Ramanathan S, Dale RC, Brilot F. Single-cell approaches to investigate B cells and antibodies in autoimmune neurological disorders. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(2):294–306. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0510-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheng K, Cao W, Niu Y, Deng Q, Zong C. Effective detection of variation in single-cell transcriptomes using MATQ-seq. Nat Methods. 2017;14(3):267–270. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woodsworth DJ, Castellarin M, Holt RA. Sequence analysis of T-cell repertoires in health and disease. Genome Med. 2013;5(10):98. doi: 10.1186/gm502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salomon R, Kaczorowski D, Valdes-Mora F, Nordon RE, Neild A, Farbehi N, et al. Droplet-based single cell RNAseq tools: a practical guide. Lab Chip. 2019;19(10):1706–1727. doi: 10.1039/C8LC01239C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni J, Hu C, Li H, Li X, Fu Q, Czajkowsky DM, et al. Significant improvement in data quality with simplified SCRB-seq. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2020;52(4):457–459. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmaa007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Islam S, Kjallquist U, Moliner A, Zajac P, Fan JB, Lonnerberg P, et al. Characterization of the single-cell transcriptional landscape by highly multiplex RNA-seq. Genome Res. 2011;21(7):1160–1167. doi: 10.1101/gr.110882.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keren-Shaul H, Kenigsberg E, Jaitin DA, David E, Paul F, Tanay A, et al. MARS-seq2.0: an experimental and analytical pipeline for indexed sorting combined with single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2019;14(6):1841–1862. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hicks SC, Townes FW, Teng M, Irizarry RA. Missing data and technical variability in single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments. Biostatistics. 2018;19(4):562–578. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxx053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leek JT, Scharpf RB, Bravo HC, Simcha D, Langmead B, Johnson WE, et al. Tackling the widespread and critical impact of batch effects in high-throughput data. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(10):733–739. doi: 10.1038/nrg2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Risso D, Ngai J, Speed TP, Dudoit S. Normalization of RNA-seq data using factor analysis of control genes or samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(9):896–902. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aran D, Looney AP, Liu L, Wu E, Fong V, Hsu A, et al. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(2):163–172. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0276-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang X, Lan Y, Xu J, Quan F, Zhao E, Deng C, et al. Cell Marker: a manually curated resource of cell markers in human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D721–D728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liao J, Yu Z, Chen Y, Bao M, Zou C, Zhang H, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing of human kidney. Sci Data. 2020;7(1):4. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0351-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kharchenko PV, Silberstein L, Scadden DT. Bayesian approach to single-cell differential expression analysis. Nat Methods. 2014;11(7):740–742. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ilicic T, Kim JK, Kolodziejczyk AA, Bagger FO, Mccarthy DJ, Marioni JC, et al. Classification of low quality cells from single-cell RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2016;17:29. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0888-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y, Hu J, Liu D, Zhou S, Liao J, Liao G, et al. Single-cell analysis reveals immune landscape in kidneys of patients with chronic transplant rejection. Theranostics. 2020;10(19):8851–8862. doi: 10.7150/thno.48201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prabhakaran S, Azizi E, Carr A, Pe’er D. Dirichlet process mixture model for correcting technical variation in single-cell gene expression data. JMLR Workshop Conf Proc. 2016;48:1070–1079. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bacher R, Kendziorski C. Design and computational analysis of single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments. Genome Biol. 2016;17:63. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0927-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Maaten L, Hinton G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J Mach Learn Res. 2008;9:2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levine JH, Simonds EF, Bendall SC, Davis KL, El Amir AD, Tadmor MD, et al. Data-driven phenotypic dissection of AML reveals progenitor-like cells that correlate with prognosis. Cell. 2015;162(1):184–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Becht E, Mcinnes L, Healy J, Dutertre CA, Kwok IWH, Ng LG, et al. Dimensionality reduction for visualizing single-cell data using UMAP. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;37:38–44. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu C, Su Z. Identification of cell types from single-cell transcriptomes using a novel clustering method. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(12):1974–1980. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pierson E, Yau C. ZIFA: Dimensionality reduction for zero-inflated single-cell gene expression analysis. Genome Biol. 2015;16:241. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0805-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Korsunsky I, Millard N, Fan J, Slowikowski K, Zhang F, Wei K, et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat Methods. 2019;16(12):1289–1296. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0619-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trapnell C, Cacchiarelli D, Grimsby J, Pokharel P, Li S, Morse M, et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(4):381–386. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qiu X, Hill A, Packer J, Lin D, Ma YA, Trapnell C. Single-cell mRNA quantification and differential analysis with Census. Nat Methods. 2017;14(3):309–315. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ji Z, Ji H. TSCAN: pseudo-time reconstruction and evaluation in single-cell RNA-seq analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(13):e117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Setty M, Tadmor MD, Reich-Zeliger S, Angel O, Salame TM, Kathail P, et al. Wishbone identifies bifurcating developmental trajectories from single-cell data. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(6):637–645. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Street K, Risso D, Fletcher RB, Das D, Ngai J, Yosef N, et al. Slingshot: cell lineage and pseudotime inference for single-cell transcriptomics. BMC Genom. 2018;19(1):477. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4772-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haghverdi L, Büttner M, Wolf FA, Buettner F, Theis FJ. Diffusion pseudotime robustly reconstructs lineage branching. Nat Methods. 2016;13(10):845–848. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bendall SC, Davis KL, Amir EAD, Tadmor MD, Simonds EF, Chen TJ, et al. Single-cell trajectory detection uncovers progression and regulatory coordination in human B cell development. Cell. 2014;157(3):714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saelens W, Cannoodt R, Todorov H, Saeys Y. A comparison of single-cell trajectory inference methods. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(5):547–554. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dangi A, Yu S, Luo X. Emerging approaches and technologies in transplantation: the potential game changers. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16(4):334–342. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0207-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Noé A, Cargill TN, Nielsen CM, Russell AJC, Barnes E. The application of single-cell RNA sequencing in vaccinology. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:8624963. doi: 10.1155/2020/8624963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.See P, Lum J, Chen J, Ginhoux F. A single-cell sequencing guide for immunologists. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2425. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Simone M, Rossetti G, Pagani M. Single cell T cell receptor sequencing: techniques and future challenges. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1638. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zheng P, Tamaresis J, Thangavelu G, Xu L, You X, Blazar BR, et al. Recipient-specific T-cell repertoire reconstitution in the gut following murine hematopoietic cell transplant. Blood Adv. 2020;4(17):4232–4243. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stubbington MJT, Lönnberg T, Proserpio V, Clare S, Speak AO, Dougan G, et al. T cell fate and clonality inference from single-cell transcriptomes. Nat Methods. 2016;13(4):329–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morris H, Dewolf S, Robins H, Sprangers B, Locascio SA, Shonts BA, et al. Tracking donor-reactive T cells: evidence for clonal deletion in tolerant kidney transplant patients. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(272):272ra10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.DeWolf S, Sykes M. Alloimmune T cells in transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(7):2473–2481. doi: 10.1172/JCI90595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alachkar H, Mutonga M, Kato T, Kalluri S, Kakuta Y, Uemura M, et al. Quantitative characterization of T-cell repertoire and biomarkers in kidney transplant rejection. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):181. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0395-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yew PY, Alachkar H, Yamaguchi R, Kiyotani K, Fang H, Yap KL, et al. Quantitative characterization of T-cell repertoire in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(9):1227–1234. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Halloran PF, Pereira AB, Chang J, Matas A, Picton M, De Freitas D, et al. Potential impact of microarray diagnosis of T cell-mediated rejection in kidney transplants: the INTERCOM study. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(9):2352–2363. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stewart BJ, Ferdinand JR, Clatworthy MR. Using single-cell technologies to map the human immune system: implications for nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(2):112–128. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reinders ME, Rabelink TJ, Briscoe DM. Angiogenesis and endothelial cell repair in renal disease and allograft rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4):932–942. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sis B, Jhangri GS, Bunnag S, Allanach K, Kaplan B, Halloran PF. Endothelial gene expression in kidney transplants with alloantibody indicates antibody-mediated damage despite lack of C4d staining. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(10):2312–2323. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Malone AF, Wu H, Fronick C, Fulton R, Gaut JP, Humphreys BD. Harnessing expressed single nucleotide variation and single cell rna sequencing to define immune cell chimerism in the rejecting kidney transplant. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(9):1977–1986. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bellan C, Amato T, Carmellini M, Onorati M, D’amuri A, Leoncini L, et al. Analysis of the IgVH genes in T cell-mediated and antibody-mediated rejection of the kidney graft. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(1):47–53. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.082024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dangi A, Natesh NR, Husain I, Ji Z, Barisoni L, Kwun J, et al. Single cell transcriptomics of mouse kidney transplants reveals a myeloid cell pathway for transplant rejection. JCI Insight. 2020;5(20):e141321. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.141321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Varma E, Luo X, Muthukumar T. Dissecting the human kidney allograft transcriptome: single-cell RNA sequencing. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2021;26(1):43–51. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lei H, Reinke P, Volk HD, Lv Y, Wu R. Mechanisms of immune tolerance in liver transplantation-crosstalk between alloreactive T cells and liver cells with therapeutic prospects. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2667. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dai H, Zheng Y, Thomson AW, Rogers NM. Transplant tolerance induction: insights from the liver. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1044. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Feng S, Bucuvalas J. Tolerance after liver transplantation: Where are we? Liver Transpl. 2017;23(12):1601–1614. doi: 10.1002/lt.24845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thomson AW, Vionnet J, Sanchez-Fueyo A. Understanding, predicting and achieving liver transplant tolerance: from bench to bedside. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(12):719–739. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Choudhary NS, Saigal S, Bansal RK, Saraf N, Gautam D, Soin AS. Acute and chronic rejection after liver transplantation: what a clinician needs to know. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;7(4):358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Feng S, Bucuvalas JC, Demetris AJ, Burrell BE, Spain KM, Kanaparthi S, et al. Evidence of chronic allograft injury in liver biopsies from long-term pediatric recipients of liver transplants. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1838–51.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Misharin AV, Morales-Nebreda L, Reyfman PA, Cuda CM, Walter JM, Mcquattie-Pimentel AC, et al. Monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages drive lung fibrosis and persist in the lung over the life span. J Exp Med. 2017;214(8):2387–2404. doi: 10.1084/jem.20162152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mccubbrey AL, Barthel L, Mohning MP, Redente EF, Mould KJ, Thomas SM, et al. Deletion of c-FLIP from CD11bhi macrophages prevents development of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58(1):66–78. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0154OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Reyfman PA, Walter JM, Joshi N, Anekalla KR, Mcquattie-Pimentel AC, Chiu S, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of human lung provides insights into the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;199(12):1517–1536. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2410OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mould KJ, Moore CM, Mcmanus SA, Mccubbrey AL, Mcclendon JD, Griesmer CL, et al. Airspace macrophages and monocytes exist in transcriptionally distinct subsets in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(8):946–956. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1989OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Snyder ME, Finlayson MO, Connors TJ, Dogra P, Senda T, Bush E, et al. Generation and persistence of human tissue-resident memory T cells in lung transplantation. Sci Immunol. 2019;4(33):eaav5581. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aav5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dong F, Hao S, Zhang S, Zhu C, Cheng H, Yang Z, et al. Differentiation of transplanted haematopoietic stem cells tracked by single-cell transcriptomic analysis. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22(6):630–639. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-0512-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fujisaki J, Wu J, Carlson AL, Silberstein L, Putheti P, Larocca R, et al. In vivo imaging of Treg cells providing immune privilege to the haematopoietic stem-cell niche. Nature. 2011;474(7350):216–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Beilhack A, Schulz S, Baker J, Beilhack GF, Wieland CB, Herman EI, et al. In vivo analyses of early events in acute graft-versus-host disease reveal sequential infiltration of T-cell subsets. Blood. 2005;106(3):1113–1122. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.DiRienzo CG, Murphy GF, Jones SC, Korngold R, Friedman TM. T-cell receptor Valpha spectratype analysis of a CD4-mediated T-cell response against minor histocompatibility antigens involved in severe graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(8):818–827. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Divito SJ, Aasebo AT, Matos TR, Hsieh PC, Collin M, Elco CP, et al. Peripheral host T cells survive hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and promote graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(9):4624–4636. doi: 10.1172/JCI129965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Habib N, Avraham-Davidi I, Basu A, Burks T, Shekhar K, Hofree M, et al. Massively parallel single-nucleus RNA-seq with DroNc-seq. Nat Methods. 2017;14(10):955–958. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Babel N, Stervbo U, Reinke P, Volk HD. The identity card of T cells-clinical utility of T-cell receptor repertoire analysis in transplantation. Transplantation. 2019;103(8):1544–1555. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen H, Ye F, Guo G. Revolutionizing immunology with single-cell RNA sequencing. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16(3):242–249. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0214-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Denisenko E, Guo BB, Jones M, Hou R, De Kock L, Lassmann T, et al. Systematic assessment of tissue dissociation and storage biases in single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-seq workflows. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02048-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wu H, Kirita Y, Donnelly EL, Humphreys BD. Advantages of single-nucleus over single-cell RNA sequencing of adult kidney: rare cell types and novel cell states revealed in fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(1):23–32. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018090912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Slyper M, Porter CBM, Ashenberg O, Waldman J, Drokhlyansky E, Wakiro I, et al. A single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-Seq toolbox for fresh and frozen human tumors. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):792–802. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0844-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Roy AL, Conroy RS. Toward mapping the human body at a cellular resolution. Mol Biol Cell. 2018;29(15):1779–1785. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E18-04-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vegh P, Haniffa M. The impact of single-cell RNA sequencing on understanding the functional organization of the immune system. Brief Funct Genom. 2018;17(4):265–272. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/ely003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zeng T, Dai H. Single-cell rna sequencing-based computational analysis to describe disease heterogeneity. Front Genet. 2019;10:629. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schlitzer A, Sivakamasundari V, Chen J, Sumatoh HR, Schreuder J, Lum J, et al. Identification of cDC1- and cDC2-committed DC progenitors reveals early lineage priming at the common DC progenitor stage in the bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(7):718–728. doi: 10.1038/ni.3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pang WW, Price EA, Sahoo D, Beerman I, Maloney WJ, Rossi DJ, et al. Human bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells are increased in frequency and myeloid-biased with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(50):20012–20017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116110108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jaitin DA, Kenigsberg E, Keren-Shaul H, Elefant N, Paul F, Zaretsky I, et al. Massively parallel single-cell RNA-seq for marker-free decomposition of tissues into cell types. Science. 2014;343(6172):776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.1247651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Miyamoto DT, Zheng Y, Wittner BS, Lee RJ, Zhu H, Broderick KT, et al. RNA-Seq of single prostate CTCs implicates noncanonical Wnt signaling in antiandrogen resistance. Science. 2015;349(6254):1351–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, Matcovitch-Natan O, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Ulland TK, et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer's disease. Cell. 2017;169(7):1276–90.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Myklebust JH, Brody J, Kohrt HE, Kolstad A, Czerwinski DK, Walchli S, et al. Distinct patterns of B-cell receptor signaling in non-Hodgkin lymphomas identified by single-cell profiling. Blood. 2017;129(6):759–770. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-718494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Young RM, Staudt LM. Targeting pathological B cell receptor signalling in lymphoid malignancies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(3):229–243. doi: 10.1038/nrd3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zheng GX, Terry JM, Belgrader P, Ryvkin P, Bent ZW, Wilson R, et al. Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14049. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bjorklund AK, Forkel M, Picelli S, Konya V, Theorell J, Friberg D, et al. The heterogeneity of human CD127(+) innate lymphoid cells revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(4):451–460. doi: 10.1038/ni.3368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Paul F, Arkin Y, Giladi A, Jaitin DA, Kenigsberg E, Keren-Shaul H, et al. Transcriptional heterogeneity and lineage commitment in myeloid progenitors. Cell. 2016;164(1–2):325. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ye Y, Song H, Zhang J, Shi S. Understanding the biology and pathogenesis of the kidney by single-cell transcriptomic analysis. Kidney Dis (Basel) 2018;4(4):214–225. doi: 10.1159/000492470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.