Abstract

Wheat stem rust, caused by Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici, is a re‐emerging disease, posing a significant threat to durum wheat production worldwide. The limited number of stem rust resistance genes in modern cultivars compels us to identify and incorporate new effective genes in durum wheat breeding programs. We evaluated 8,245 spring durum wheat accessions deposited at the USDA National Small Grains Collection (NSGC) for resistance in field stem rust nurseries in Debre Zeit, Ethiopia and St. Paul, MN (USA). A higher level of disease development was observed at the Debre Zeit nursery compared with St. Paul, and the effective alleles of Sr13 in this nursery did not display the level of resistance observed at the St. Paul nursery. Four hundred and ninety‐one (∽6%) accessions exhibited resistant to moderately susceptible responses after three field evaluations at Debre Zeit and two at St. Paul. Nearly 70% of these accessions originated from Ethiopia, Mexico, Egypt, and USA. Eight additional countries, namely Portugal, Turkey, Italy, Canada, Chile, Australia, Syria, and Tunisia contributed to 19% of the resistant to moderately susceptible entries. Among the 491 resistant to moderately susceptible accessions, 53.8% (n = 265) were landraces, and 28.4% (n = 139) and 11.4% (n = 55) were breeding lines and cultivars, respectively. Breeding lines and cultivars displayed a higher level and frequency of resistance than the landraces. We concluded that a large number of durum wheat accessions from diverse origins deposited at the NSGC can be exploited for diversifying and improving stem rust resistance in wheat.

Core Ideas

Identify new sources of stem rust resistance through field evaluations of durum wheat.

8,245 durum accessions deposited at NSGC evaluated in two field nurseries (Ethiopia and US).

Presence of large number of entries from diverse origin that can be used for rust resistance.

Abbreviations

- APR

adult plant resistance

- COI

coefficient of infection

- MR

moderately resistant

- MS

moderately susceptible

- NSGC

National Small Grains Collection

- Pgt

Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici

- R

resistant

- Ssusceptible

susceptible

- T

traces.

1. INTRODUCTION

Stem or black rust, caused by Puccinia graminis Pers.:Pers. f. sp. tritici Eriks. & E. Henn. (Pgt), is one of the most destructive diseases of durum wheat [Triticum turgidum L. sp. durum (Desf.) Huns.] and bread wheat (T. aestivum L.) worldwide. Severe devastations caused by stem rust epidemics were reported in the major wheat‐growing regions until the late 1950s (Roelfs, 1985; Saari & Prescott, 1985) when the disease was effectively controlled through the widespread use of host resistance and the eradication of the alternate host, common barberry (Berberis vulgaris L.) in Europe and the USA. Wheat stem rust is a re‐emerging disease, posing a significant threat to wheat production worldwide (Singh et al., 2015). The occurrence and spread of Sr31‐virulent races in the Ug99 race group in East Africa (Hale et al., 2013; Newcomb et al., 2016; Pretorius et al., 2000; Singh et al., 2015; Wanyera et al., 2006), coupled with other races causing severe epidemics and localized outbreaks in East Africa (Olivera et al., 2015), Europe (Bhattacharya, 2017; Lewis et al., 2018; Olivera Firpo et al., 2017), and Central Asia (Shamanin et al., 2020), indicates that the disease has reemerged as a major challenge to wheat production.

Tetraploid wheats have contributed genes for stem rust resistance, including Sr7a, Sr8b, several alleles of Sr9, Sr11, Sr12, alleles of Sr13, Sr14, Sr17, and Sr8155‐B1 (McIntosh et al., 1995; Nirmala et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). Many of these genes are widely used in common and durum wheat, contributing to the successful control of stem rust worldwide. For example, Sr13 is a major component of stem rust resistance in durum wheat worldwide (Klindworth et al., 2007; Luig, 1983; Quamar et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2015), and it is the only gene in durum wheat that is effective against all variants in the Ug99 race group (Simons et al., 2011). The occurrence of Pgt races (JRCQC and TTRTF) with combined virulence to Sr13b and Sr9e (Olivera et al., 2012b; Olivera et al., 2019), has increased the vulnerability of durum wheat. The severe stem rust epidemic on durum wheat in Sicily (Italy) in 2016 caused by race TTRTF (Bhattacharya, 2017; Patpour et al., 2018) was indicative of the threat of stem rust to durum wheat production. Virulent Pgt races, including TTRTF, were recently detected in North Africa and the Middle East, both regions where durum wheat is an important crop (Hovmøller et al., 2020; Patpour et al., 2020). The limited availability of resistance to stem rust in durum wheat, coupled with the rapid occurrence and spread of virulent Pgt races, requires the identification and deployment of new and diverse resistance genes. Genetic resources, such as those maintained in germplasm banks, offer diverse sources to expand the genetic base of stem rust resistance in durum wheat. More than 78,000 accessions of durum wheat and its close relatives (other T. turgidum spp.) are deposited in germplasm collections around the world (Skovmand et al., 2005). The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Small Grain Collection (NSGC) in Aberdeen (Idaho) maintains about 8,300 durum wheat accessions from more than 80 countries, which include landraces, obsolete cultivars, and modern breeding lines and cultivars. Breeding lines and cultivars represent the most immediate useful germplasm for breeding for disease resistance, but their contribution of new resistance genes may be limited because of the narrow genetic background of the pool of elite durum cultivars (Maccaferri et al., 2005; Singh et al., 1992). Durum landraces provide a useful source of genetic variability. These genetically diverse and locally well‐adapted materials derived from farmers’ selections provide a good source of genetic variability for crop improvement (Villa et al., 2006). However, as landraces are unimproved materials, more intensive pre‐breeding manipulations are required to transfer desired genes from them into advanced breeding lines (Skovmand & Rajaram, 1990). The objective of this work was to identify new sources of stem rust resistance through field evaluations of durum wheat accessions deposited at the NSGC germplasm bank.

Core Ideas

Identify new sources of stem rust resistance through field evaluations of durum wheat.

8,245 durum accessions deposited at NSGC evaluated in two field nurseries (Ethiopia and US).

Presence of large number of entries from diverse origin that can be used for rust resistance.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Germplasm

A total of 8,245 spring durum wheat accessions deposited at the USDA NSGC (Aberdeen, ID, USA) were evaluated for 9 yr. The collection included 574 cultivars, 1,195 breeding materials, 5,688 landraces, and 788 accessions of uncertain improvement status from 82 countries. Among the countries, 17 contributed more than 100 accessions each, 32 contributed between 10 and 99 accessions, and 33 contributed fewer than 10 accessions (Supplementary Table S1).

2.2. Field stem rust evaluation

Field stem rust evaluations were conducted between 2009 and 2017 at the international durum stem rust nursery at Debre Zeit Agricultural Research Center in Ethiopia and at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul, MN (USA). At the Debre Zeit nursery, stem rust evaluations were performed in two seasons per year: the main (meher) season under rainfed conditions (June – November) and the off‐season under irrigated conditions (January – June). The Debre Zeit nursery was artificially inoculated with a local source of inoculum that consisted of races TTKSK (a variant in the Ug99 race group), JRCQC (combined virulence on Sr13b and Sr9e), and race TRTTF (appeared to be virulent to Sr9e and Sr13a) (Olivera et al., 2012b). Since 2014, race TKTTF, which was responsible for the severe stem rust epidemic in Ethiopia in 2013 (Olivera et al., 2015), was included as part of the field inoculum. In St. Paul, the nursery was artificially inoculated with a composite of six US races representing a diversity of virulence to specific resistance genes: TPMKC, RKRQC, RCRSC, QTHJC, QFCSC, and MCCFC. The virulence/avirulence profile of all the isolates used in this study is presented in Table 1. At the Debre Zeit nursery, entries were planted in double 1‐m row plots, whereas in St. Paul nursery, entries were planted as single 1‐m rows. Wheat cultivar ‘Red Bobs’ (cultivar 6255) or line LMPG‐6 was included at an interval of 50 lines as a susceptibility check. Continuous rows of stem rust spreader (i.e., mixture of susceptible lines) were planted perpendicular to all entries to facilitate inoculum buildup and uniform infection. In addition, the 20 stem rust differentials and lines carrying other relevant stem rust resistance genes were planted every season to monitor pathogen virulence in the nursery. Wheat lines and cultivars carrying Sr13a (ST464, Combination VII, and Khapstein/9*LMPG‐6) and Sr13b (Leeds and Sceptre) were also included to assess the effect of this resistance gene under field conditions in both nurseries. For details about the management of the nurseries and inoculation procedures at St. Paul and Debre Zeit, refer to Olivera et al., 2012a, 2012b. Disease assessment was done at the soft‐dough stage of plant growth. Because of differences in maturity among durum entries, three to four data points were recorded at weekly intervals, starting when the first entries reached the soft‐dough stage. Plants were evaluated for their response to infection (i.e., pustule type and size) (Roelfs et al., 1992) and terminal disease severity following the modified Cobb scale (Peterson et al., 1948). Infection response categories were: resistant (R), moderately resistant (MR), moderately susceptible (MS), and susceptible (S). Combinations of categories were recorded when two or more infection responses were observed on a single stem. Infection response categories R, R‐MR, and MR‐R were considered resistant, infection responses MR and MR‐MS were considered moderately resistant, and infection responses MS‐MR and MS with 30% or lower stem rust severity were considered moderately susceptible.

TABLE 1.

Isolate designation, origin, and virulence phenotype of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici races used to evaluate resistance in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum)

| Race | Isolate | Origin | Avirulence | Virulence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTKSKa | P14ETH02‐1 | Ethiopia | Sr24 36 Tmp | Sr5 6 7b 8a 9a 9b 9d 9e 9g 10 11 17 21 30 31 38 McN |

| TRTTF | 33Wonchi‐1 | Ethiopia | Sr8a 24 31 | Sr5 6 7b 9a 9b 9d 9e 9g 10 11 17 21 30 36 38 McN Tmp |

| JRCQC | PETH01DZ‐2 | Ethiopia | Sr5 7b 8a 9b 10 24 30 31 36 38 Tmp | Sr6 9a 9d 9e 9g 11 17 21 McN |

| TKTTF | Digalu 1/1 Assasa | Ethiopia | Sr11 24 31 | Sr5 6 7b 8a 9a 9b 9d 9e 9g 10 17 21 30 36 38 McN Tmp |

| TPMKC | 74MN1409 | USA | Sr6 9a 9b 24 30 31 38 | Sr5 7b 8a 9d 9e 9g 10 11 17 21 36 McN Tmp |

| RKRQC | 99KS76A‐1 | USA | Sr9e 10 11 24 30 31 38 Tmp | Sr5 6 7b 8a 9a 9b 9d 9g 17 21 36 McN |

| RCRSC | 77ND82A | USA | Sr6 8a 9e 11 24 30 31 38 Tmp | Sr5 7b 9a 9b 9d 9g 10 17 21 36 McN |

| QTHJC | 75ND717C | USA | Sr7b 9a 9e 24 30 31 36 38 Tmp | Sr5 6 8a 9b 9d 9g 10 11 17 McN |

| QFCSC | 06ND76C | USA | Sr6 7b 9b 9e 11 24 30 31 36 38 Tmp | Sr5 8a 9a 9d 9g 10 17 21 McN |

| MCCFC | 59KS19 | USA | Sr6 8a 9a 9b 9d 9e 11 21 24 30 31 36 38 | Sr5 7b 9g 10 17 McN Tmp |

In each evaluation year, 1,000 durum accessions from NSGC and checks were evaluated for field resistance in the main‐season nursery at Debre Zeit. Entries rated as resistant, moderately resistant, and moderately susceptible, with a maximum of 30% terminal disease severity (30 MS) in the Debre Zeit field nursery, were selected and further evaluated in the next off‐season nursery at Debre Zeit and the St. Paul nursery. Entries that remained resistant to moderately susceptible after the three field tests (two in Debre Zeit and one in St. Paul) were evaluated for one additional season in both nurseries. Mean disease severity and median infection response in both the Debre Zeit and St. Paul nursery evaluations were calculated for all the accessions that were resistant to moderately susceptible in all field tests. The median infection response for each accession was converted into a constant value and multiplied by the terminal disease severity to derive a coefficient of infection (COI; Stubbs et al., 1986). One‐way ANOVA and Duncan's Multiple Range Test were used to test the significance of the difference in the mean disease severity and the COI.

3. RESULTS

Uniform disease development across the field was observed in the Debre Zeit and St. Paul stem rust nurseries in all the seasons. Disease development was generally higher in the Debre Zeit nursery than the St. Paul nursery. In Debre Zeit, disease severity and infection response on the susceptible checks ranged between 50 and 90 S, with a mean value of 75 S, whereas in St. Paul, disease severity and infection response ranged between 50 and 80 S, with a mean value of 65 S. Infection observed on the differentials and lines carrying additional genes confirmed the virulence composition of the used inoculum in both nurseries. Unusual virulences were not detected in all the field seasons in Debre Zeit and St. Paul nurseries (data not shown). At the St. Paul nursery, lines carrying Sr13a (ST464, Combination VII, and Khapstein/9*LMPG) exhibited a moderately resistant to moderately susceptible response, whereas the two cultivars carrying Sr13b (Leeds and Sceptre) were highly resistant (0 to 10 R) (Table 2). At the Debre Zeit nursery, these five lines and cultivars, carrying Sr13a and Sr13b, exhibited high infection response and disease severity that ranged from 30 MS to 60 S (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Range of stem rust infection response and disease severity of durum wheat lines and cultivars carrying alleles of Sr13 gene in field evaluations in Debre Zeit, Ethiopia and St. Paul, MN stem rust nurseries

| Debre Zeit nursery | St. Paul nursery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line/Cultivar | Sr13 allele | Range of field reaction | Mean Severity | Median infection response | Mean COIa | Range of field reaction | Mean Severity | Median infection response | Mean COI |

| ST464 | Sr13a (R1)b | 30 S‐MS – 50 Sc | 43.0 | S‐MS | 40.0 | 40 MR – 50 MR‐MS | 37.0 | MR‐MS | 17.9 |

| Combination VII | Sr13a (R3) | 30 MS‐S – 50 S | 40.0 | S‐MS | 34.9 | 30 MR‐MS – 40 MS‐MR | 48.2 | MR‐MS | 23.9 |

| Khapstein/9*LMPG | Sr13a (R3) | 30 MS – 60 S | 45.0 | MS‐S | 39.0 | 40 MR‐MS – 60 MS | 50.0 | MS‐MR | 31.6 |

| Leeds | Sr13b (R2) | 30 MS‐S – 60 S | 44.3 | S‐MS | 42.0 | 0 – 5 R | 3.1 | R | 0.3 |

| Sceptre | Sr13b (R2) | 30 S – 50 S | 45.0 | S | 42.8 | T R – 10 R | 5.9 | R | 0.6 |

COI: coefficient of infection.

Based on Zhang et al. (2017).

Stem rust severity following the modified Cobb scale (Peterson, Campbell, & Hannah, 1948) and pustule type and size according to Roelfs, Singh, & Saari (1992). R, resistant; R‐MR, resistant to moderately resistant; MR‐R, moderately resistant to resistant; MR, moderately resistant; MR‐MS, moderately resistant to moderately susceptible; MS‐MR, moderately susceptible to moderately resistant; MS, moderately susceptible; S, susceptible.

From the 8,245 spring durum wheat accessions evaluated in the main season at Debre Zeit, 1,787 (21.7%) exhibited a resistant to moderately susceptible response. These accessions were evaluated again at the Debre Zeit off‐season and St. Paul nurseries, and 657 (8.0% of total accessions) remained resistant to moderately susceptible after all three field tests. An additional evaluation of these accessions in both locations resulted in 491 accessions (6.0%) exhibiting a consistent reaction from resistant to moderately susceptible in the five field tests. Results of infection response and disease severity in each field evaluation, and mean severity, median infection response, and COI of the 491 accessions are presented in Supplementary Table S2. The mean coefficients of infection at Debre Zeit and St. Paul nurseries were 9.46 and 7.23, respectively (p < .001). The distribution of the 491 durum accessions according to infection response categories and COI in both nurseries showed a higher level of resistance in St. Paul than Debre Zeit (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Number of entries in each stem rust response (A) and coefficient of infection (COI) (B) categories for 491 durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) accessions exhibiting a resistant to moderately susceptible response in three field evaluations in Debre Zeit nursery (black) and two evaluations in St. Paul nursery (grey)

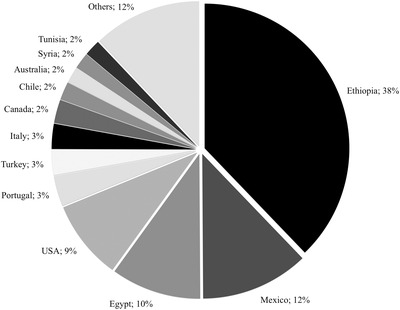

Resistant to moderately susceptible accessions were identified from 37 countries, and nearly 70% of these accessions originated from four countries: Ethiopia (38%), Mexico (12%), Egypt (10%), and USA (9%) (Figure 2). Eight additional countries, Portugal, Turkey, Italy, Canada, Chile, Australia, Syria, and Tunisia, contributed to 19% of the resistant to moderately susceptible accessions (Figure 2). The majority of resistant accessions from Ethiopia (98%), Egypt (68%), Portugal (82%), and Turkey (86%) were landraces (Table 3). All the resistant accessions from Mexico, USA, and Canada were improved materials. Breeding lines and cultivars also constituted the majority of the resistant to moderately susceptible accessions from Chile, Australia, Italy, Syria, and Tunisia (Table 3). The frequencies of resistance differed between the countries of origin. Of the countries from where we tested more than 50 accessions, Egypt (n = 183) and Mexico (n = 237) exhibited a frequency of resistance of >20%, whereas accessions from Ethiopia (n = 1,529), Canada (n = 97), Chile (n = 57), Australia (n = 52), and Syria (n = 52) had a frequency of resistance between 10 and 20% (Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

Origin and percentage distribution of the 491 durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) accessions rated as resistant to moderately susceptible after five field evaluations in Debre Zeit (Ethiopia) and St. Paul, MN (USA)

TABLE 3.

Total number of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) accessions evaluated for stem rust resistance, and number and percentage of resistant to moderately susceptible breeding materials, cultivars, landraces, and entries of unknown origin according to country of origin

| Breeding materiala | Cultivar | Landrace | Uncertain | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Total number of entries | Number of resistant entries | % of resistant to moderately susceptible entries | Total | Resistant to moderately susceptible | Total | Resistant to moderately susceptible | Total | Resistant to moderately susceptible | Total | Resistant to moderately susceptible |

| Ethiopia | 1,529 | 187 | 12.2 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 1,511 | 183 | 9 | 0 |

| Mexico | 237 | 60 | 25.3 | 189 | 50 | 34 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 9 | 3 |

| Egypt | 183 | 50 | 27.3 | 7 | 1 | 15 | 6 | 138 | 34 | 23 | 9 |

| United States | 557 | 44 | 7.9 | 484 | 37 | 63 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Portugal | 430 | 17 | 4.0 | 15 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 310 | 14 | 101 | 1 |

| Turkey | 1,188 | 14 | 1.2 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 1,117 | 12 | 54 | 0 |

| Italy | 302 | 14 | 4.6 | 105 | 4 | 107 | 7 | 62 | 2 | 28 | 1 |

| Canada | 97 | 12 | 12.4 | 61 | 9 | 35 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Chile | 57 | 10 | 17.5 | 32 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 12 | 2 |

| Tunisia | 310 | 8 | 2.6 | 21 | 5 | 24 | 2 | 250 | 1 | 15 | 0 |

| Australia | 52 | 8 | 15.4 | 28 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 3 |

| Syria | 52 | 8 | 15.4 | 22 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| France | 93 | 7 | 7.5 | 34 | 2 | 28 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 27 | 1 |

| Morocco | 197 | 4 | 2.0 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 111 | 4 | 73 | 0 |

| India | 101 | 4 | 4.0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 61 | 1 | 16 | 1 |

| Argentina | 26 | 4 | 15.4 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| Yemen | 20 | 4 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 4 |

| Algeria | 240 | 3 | 1.3 | 7 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 206 | 1 | 11 | 0 |

| Spain | 148 | 3 | 2.0 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 107 | 1 | 24 | 1 |

| Greece | 92 | 3 | 3.3 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 75 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Israel | 38 | 3 | 7.9 | 8 | 1 | 18 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| South Africa | 23 | 3 | 13.0 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Kenya | 8 | 3 | 37.5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Jordan | 77 | 2 | 2.6 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 44 | 1 | 18 | 0 |

| Serbia | 22 | 2 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 13 | 2 | 15.4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 |

| Brazil | 2 | 2 | 100.0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Iran | 929 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 929 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Russian Federation | 220 | 1 | 0.5 | 11 | 0 | 74 | 1 | 115 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| Afghanistan | 68 | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Hungary | 52 | 1 | 1.9 | 23 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 21 | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 14 | 1 |

| Georgia | 18 | 1 | 5.6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Oman | 11 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Croatia | 10 | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Switzerland | 9 | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Tajikistan | 8 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 805 | 0 | 0.0 | 62 | 0 | 58 | 0 | 454 | 0 | 231 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 8,245 | 491 | 6.0 | 1,195 | 139 | 574 | 55 | 5,688 | 265 | 788 | 32 |

Improvement status according to the USDA‐ARS National Small Grains Collection (Aberdeen, ID).

Based on the median infection response from the five field evaluations, 28.3% of the 491 accessions were classified as resistant (i.e., infection responses R, R‐MR, and MR‐R), 62.5% as moderately resistant (i.e., infection responses MR and MR‐MS), and 9.2% as moderately susceptible (i.e., infection responses MS‐MR and MS) (Table 4). The mean terminal disease severities were 12.6, 20.9, and 26.1% in resistant, moderately resistant, and moderately susceptible categories, respectively (Table 4). The mean COI were also significantly different between the respective categories (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Mean disease severity and coefficient of infection (COI) of 491 durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) entries categorized as resistant, moderately resistant, and moderately susceptible in five field evaluations at the Debre Zeit and St. Paul stem rust field nurseries

| Category | Mean disease severity | Mean COI | Number (%) of accessions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant | 12.6 ca | 3.5 c | 139 (28.3%) |

| Moderately resistant | 20.9 b | 9.5 b | 307 (62.5%) |

| Moderately susceptible | 26.1 a | 15.9 a | 45 (9.2%) |

| TOTAL | 19.1 | 8.4 | 491 (100%) |

‘a’ ‘b’ and ‘c’ indicate statistically significant differences among resistant categories (P < .05).

Of the 491 selected accessions, 53.8% (n = 265) were landraces, and 28.4% (n = 139) and 11.4% (n = 55) were breeding lines and cultivars, respectively (Table 5). Only 4.7% of the landraces evaluated (n = 5,688) were classified as resistant to moderately susceptible, whereas 11.7 and 9.8% of the total evaluated breeding lines and cultivars, respectively, were classified into these resistant categories (Table 5). In addition to having a higher proportion of moderately resistant accessions, the mean disease severity and COI were significantly higher for the landraces (21.4 and 9.6, respectively) compared with the breeding lines (15.4 and 6.4) and cultivars (17.0 and 7.3) (Table 6). Twenty‐five accessions that exhibited the lowest COI are listed in Table 7. The elite resistant group of accessions consistently exhibited moderately resistant to resistant responses and low disease severity throughout five seasons of field evaluation. The group consisted of breeding lines, cultivars, and landraces from different countries.

TABLE 5.

Improvement status of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) accessions classified as resistant to moderately susceptible to wheat stem rust in five field evaluations at the Debre Zeit and St. Paul stem rust nurseries

| Improvement statusa | Resistant to moderately susceptible accessions | Total number of accessions evaluated |

|---|---|---|

| Breeding material | 139 (11.7%) | 1,195 |

| Cultivar | 55 (9.8%) | 574 |

| Landrace | 265 (4.7%) | 5,688 |

| Uncertain | 32 (4.1%) | 788 |

| TOTAL | 491 | 8,245 |

According to the USDA‐ARS National Small Grains Collection (Aberdeen, ID).

TABLE 6.

Percentage of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) accessions belonging to each resistant category, and mean disease severity and coefficient of infection (COI) according to improvement status

| Category | Breeding materialsa | Cultivars | Landraces | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant | 41.6 | 38.2 | 19.8 | 39.4 |

| Moderately resistant | 51.4 | 49.1 | 71.1 | 54.6 |

| Moderately susceptible | 7.0 | 12.7 | 9.1 | 6.0 |

| Mean disease severity | 15.4 bb | 17.0 b | 21.4 a | 18.8 b |

| Mean COI | 6.4 bc | 7.3 b | 9.6 a | 7.9 b |

Improvement status according to the USDA‐ARS National Small Grains Collection (Aberdeen, ID).

‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate statistically significant differences for mean disease severity among improvement status groups (P < .05).

‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate statistically significant differences for mean COI among improvement status groups (P < .05).

TABLE 7.

Stem rust infection response, disease severity, and coefficient of infection (COI) of the 25 most resistant durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) accessions after five field evaluations in Debre Zeit and St. Paul stem rust nurseries

| Debre Zeit nursery | St. Paul nursery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Country | Improvement status | 1st Eval. | 2nd Eval. | 3rd Eval. | 1st Eval. | 2nd Eval | Mean severity | Median infection response | COIa |

| PI 428549 | France | Cultivar | T Rb | T R | 5 R | T R | 5 R | 2.6 | R | 0.3 |

| PI 519716 | India | Uncertain | 5 R | 5 R | T R | T R | 5 R | 3.4 | R | 0.3 |

| PI 520518 | USA | Breeding line | 5 R‐MR | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | T R | T R | 3.4 | R | 0.3 |

| PI 520348 | Ethiopia | Cultivar | 5 R | 5 R | T R | 5 R | 5 R | 4.2 | R | 0.4 |

| CItr 15710 | USA | Breeding line | 5 R | 5 R | 5 R | 5 R | 5 R | 5.0 | R | 0.5 |

| PI 377886 | Australia | Uncertain | 5 R | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | 5.0 | R | 0.5 |

| PI 506469 | USA | Cultivar | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | 5 R | 5.0 | R | 0.5 |

| PI 519777 | USA | Breeding line | 0 | T MR | T R | T R | 10 R | 2.6 | R‐MR | 0.5 |

| PI 519380 | Tunisia | Breeding line | T R | 10 R | 10 R‐MR | 5 R | 5 R | 6.2 | R | 0.6 |

| PI 435060 | Croatia | Landrace | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | 10 R‐MR | 5 R | 10 R | 7.0 | R | 0.7 |

| CItr 12920 | Canada | Breeding line | 5 R‐MR | 10 R‐MR | T R | 10 R | 10 R | 7.2 | R | 0.7 |

| PI 520117 | USA | Breeding line | 5 R | 10 R | 10 R | 5 R | 5 R | 7.5 | R | 0.8 |

| PI 519445 | USA | Breeding line | T R | T MR | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | 10 R | 4.4 | R‐MR | 0.8 |

| PI 428454 | Mexico | Breeding line | 5 MR | 5 MR | T R | 5 R‐MR | 5 R‐MR | 4.2 | MR‐R | 1.3 |

| PI 639888 | USA | Breeding line | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | 10 R‐MR | 5 R | 10 MR‐R | 7.0 | R‐MR | 1.4 |

| PI 519933 | Tunisia | Breeding line | 10 R‐MR | 10 R‐MR | T R | 10 MR | 5 R | 7.2 | R‐MR | 1.4 |

| PI 367238 | Italy | Cultivar | 10 MR | 20 MR | 0 | 5 R | 5 R | 8.0 | R‐MR | 1.6 |

| PI 278505 | Spain | Uncertain | 5 MR | 5 R‐MR | 5 MR | 5 R‐MR | 10 R‐MR | 6.0 | MR‐R | 1.8 |

| PI 470793 | Ethiopia | Landrace | 10 R‐MR | 5 MR‐R | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | 20 MR | 9.0 | R‐MR | 1.8 |

| PI 519469 | Syria | Landrace | 5 R‐MR | 5 R | 5 R‐MR | 15 R‐MR | 15 R‐MR | 9.0 | R‐MR | 1.8 |

| PI 639886 | USA | Breeding line | 10 R‐MR | 5 R | 10 MR | 15 MR‐R | 5 R‐MR | 9.0 | R‐MR | 1.8 |

| PI 520393 | Tunisia | Breeding line | 30 MR‐MS | T MR | 5 R | 5 R | 5 R | 9.2 | R‐MR | 1.8 |

| CItr 15277 | Italy | Uncertain | 5 R‐MR | 10 MR‐R | 10 R | 10 R | 15 MR | 10.0 | R‐MR | 2.0 |

| CItr 15769 | USA | Breeding line | 15 MR‐MS | 5 R | 10 R‐MR | 10 R | 10 R | 10.0 | R‐MR | 2.0 |

| PI 324928 | Argentina | Breeding line | 15 MR | 5 MR | 5 R | 20 R | 5 R | 10.0 | R‐MR | 2.0 |

| Susceptible checks (Red Bobs / LMPG‐6) | 70 S | 80 S | 70 S | 70 S | 65 S | 71.0 | S | 71.0 | ||

COI (Stubbs, Prescott, Saari, & Dubin, 1986) calculated as the product of terminal disease severity and media infection response converted into a constant value. R = 0.1, R‐MR = 0.2, MR‐R = 0.3, MR = 0.4, MR‐MS = 0.5, MS‐MR = 0.6, MS = 0.7, MS‐S = 0.8, S‐MS = 0.9, S = 1.0.

Stem rust severity following the modified Cobb scale (Peterson, Campbell, & Hannah, 1948) and pustule type and size according to Roelfs, Singh, & Saari (1992). R, resistant; R‐MR, resistant to moderately resistant; MR‐R, moderately resistant to resistant; MR, moderately resistant; MR‐MS, moderately resistant to moderately susceptible; MS‐MR, moderately susceptible to moderately resistant; MS, moderately susceptible; S, susceptible; T, traces (less than 5% severity). .

4. DISCUSSION

Wheat stem rust is a re‐emerging disease, and recent epidemics and outbreaks indicate that it can pose a threat again to durum and bread wheat production. In particular, the occurrence of Pgt races with virulence to Sr13b and Sr9e (JRCQC and TTRTF) has increased the vulnerability of durum wheat to stem rust. The limited presence of effective stem rust resistance genes in improved materials underscore the need for identifying and incorporating new genes in durum breeding programs. To identify new sources of stem rust resistance in durum wheat, we evaluated 8,245 accessions of spring durum deposited at the NSGC for field resistance at two locations: the international durum stem rust nursery in Debre Zeit, Ethiopia and the US wheat stem rust nursery in St. Paul, MN. After five field evaluations at both locations, 491 (6%) accessions from 37 countries exhibited a resistant to moderately susceptible response. These 491 accessions were of diverse origins and can be exploited in wheat breeding programs for stem rust resistance.

To identify new effective stem rust resistance genes in durum wheat, it is crucial to evaluate the entries against Pgt races that are virulent to the most widely used resistance genes. The inoculum composition at the international stem rust durum nursery at Debre Zeit contains two important races with virulence to resistance genes common in durum: JRCQC with virulence against Sr13b and Sr9e (Olivera et al., 2012b) and TTKSK, which is virulent to Sr8155B1 (Nirmala et al., 2017) and Sr7a (Jin et al., 2007). Olivera et al. (2012b) also reported an Ethiopian isolate, typed as race TRTTF, virulent on Sr9e and Sr13a at the seedling stage. Virulence on Sr13a by race TRTTF was not supported in the study done by Zhang et al. (2017). When TTKSK‐resistant durum wheats from North American breeding programs selected from field trials in Kenya in 2005 were evaluated at the Debre Zeit nursery, a large proportion became susceptible (Singh et al., 2015), suggesting that TTKSK resistance detected in Kenya, such as Sr13 alleles common in durum, became ineffective to the race(s) in the Debre Zeit inoculum (Olivera et al., 2012b). High frequencies of resistant accessions have also been reported when durum germplasm was evaluated in field nurseries, where the inoculum composition lacks Sr13 virulence (Meidaner et al., 2019; Pozniak et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2015). After nine years of field evaluations, our results indicated that, under field conditions in the Debre Zeit nursery, none of the alleles of Sr13 conferred a sufficient level of resistance. The three alleles (haplotypes R1, R2, and R3) performed in a similar fashion, with a field reaction that ranged from 30 MS to 60 S. In the St. Paul nursery, Sr13a (R1 and R3) conferred a moderate level of resistance (MR‐MS to MS‐MR), which was comparable to the resistance to races in the Ug99 group in the Njoro, Kenya field nursery (Jin et al., 2007). Cultivars carrying Sr13b (Leeds and Sceptre) exhibited a much higher level of stem rust resistance (0 to 10 R). However, this high level of resistance may not be attributed to Sr13b alone, as these two durum wheat cultivars may carry additional resistance gene/s that are highly effective against the races used as inoculum at the St. Paul nursery. Sr13 is a temperature‐sensitive gene that is more effective at temperatures ≥25°C (Zhang et al., 2017). However, the difference in the inoculum composition and overall disease pressure rather than temperature should explain the reduced effect of Sr13 alleles at the Debre Zeit nursery, as temperature during disease development at Debre Zeit, in particular in the off‐season, was higher than at St. Paul. The lack of protection conferred by Sr13 in the Debre Zeit nursery is also a strong indication of the need to broaden the base of stem rust resistance in durum wheat.

After the first evaluation at the Debre Zeit nursery, 21% of the entries exhibited resistant to moderately resistant infection responses. However, after completing five field evaluations in both locations, only 491 entries (6%) remained resistant to moderately susceptible. This difference is explained by 1) accessions resistant to Ethiopian Pgt races became susceptible when evaluated with US races, and 2) accessions that exhibited moderately resistant to moderately susceptible responses in the first evaluation in the Debre Zeit main season nursery, but, when exposed to an environment of higher disease pressure (off‐season nursery), they became moderately to fully susceptible. A higher temperature and availability of moisture through irrigation favored stem rust development in the off‐season nursery at Debre Zeit, resulting in a higher disease pressure. These results confirm the value of multiple field evaluations to adequately assess the level and stability of resistance in the evaluated germplasm. In a field evaluation at the Debre Zeit nursery in the main (rainfed) season, Chao et al. (2017) reported a higher frequency of resistant accessions at the Debre Zeit nursery in 429 durum accessions deposited at NSGC. As discussed by the authors, additional evaluations in the off‐season (irrigated) nursery could result in a reduction in the frequency of resistant accessions, as shown in this study. The similar environmental effect was evident when disease development at both locations was compared. We observed that disease severity and COI were consistently higher at the Debre Zeit nursery in the 491 accessions evaluated in all five seasons. At this nursery, there was a longer period of favorable weather conditions for disease development compared with St. Paul. The longer period of disease exposure and higher disease pressure resulted in an increased disease development at the Debre Zeit nursery.

The 491 resistant to moderately susceptible accessions can be divided into two main groups: cultivars and breeding lines mainly from North American (i.e., Mexico, USA, Canada) breeding programs and landraces from Ethiopia, Portugal, Egypt, and Turkey. About 10% of the cultivars and breeding lines evaluated in this study exhibited a resistant to moderately resistant response. Letta et al. (2013) reported 24% of 183 elite durum wheat cultivars and breeding lines from Italy, Morocco, Spain, Syria, Tunisia, southwestern USA, and Mexico to be resistant to moderately resistant when evaluated at the Debre Zeit nursery. This difference can be explained not only by the different origins of these elite materials but also because our study established a more stringent selection criteria that resulted in a lower percentage of resistant accessions.

The frequency and level of resistance exhibited by the breeding lines and cultivars were significantly higher compared with the landraces. Selection for stem rust resistance and the incorporation of effective resistance genes in modern breeding programs may have resulted in the higher resistance level in the breeding materials and cultivars. Most of the entries that exhibited the highest levels of resistance were breeding materials and cultivars. These advanced materials are good candidates for improving stem rust resistance in durum breeding programs. However, the contribution of new and diverse resistance genes from these improved materials may be limited because of the narrow genetic background of the pool of elite durum cultivars (Maccaferri et al., 2005; Quamar et al., 2009). On the contrary, landraces are a good source of genetic diversity and a potential source of new resistance genes. More than one third of the resistant accessions identified in this study were Ethiopian landraces, indicating their high potential as a source of stem rust resistance. Ethiopia is considered a secondary center of origin for tetraploid wheats (Kabbaj et al., 2017), and Ethiopian landraces have been regarded as a separate subspecies (sp. abyssinicum) of T. turgidum (Mengistu et al., 2015). Ethiopian durum landraces are morphologically distinct (Pecetti et al., 1992), and a high level of both phenotypic (Mengistu et al., 2015) and genotypic (Alemu et al., 2020) diversity has been reported. The level of resistance in Ethiopian durum landraces may be a result of thousands of years of co‐evolution with the stem rust pathogen in the central highlands of Ethiopia (Amogne et al., 2000) and an exposure to a diverse stem rust pathogen population (Admassu et al., 2009; Olivera et al., 2015). A broader and diverse basis of stem rust resistance may be needed to provide protection from the current pathogen races, such as JRCQC, that appear to have broader virulence against durum wheat (Hundie et al., 2019; Olivera et al., 2012b). Previous studies (Ataullah, 1963; Beteselassie et al., 2007; Bonman et al., 2007; Kenaschuk et al., 1959) have also identified Ethiopian landraces as a source of stem rust resistance genes. In particular, the Ethiopian landrace ST464 is the donor of Sr13a, an effective allele of Sr13, which is one of the most important stem rust resistance genes in durum wheat (Klindworth et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2017). Seedling evaluations with multiple races to further characterize these resistant selections are in progress and will be useful to select landraces with unique resistance to broaden the stem rust resistance in wheat breeding programs. This study also identified resistant landraces from Egypt, Portugal, and Turkey. Durum landraces from these countries are also highly diverse (Akond & Watanabe, 2005; Altıntaş et al., 2008; Soriano et al., 2016), but only landraces of Egyptian origin exhibited a high frequency of stem rust resistance. Only a limited number of resistant accessions was observed from Turkey (i.e., 14 out of 1,188), which disagrees with the results reported by Bonman et al. (2007). Although accessions evaluated by Bonman et al. (2007) were also a part of the NSGC, that study was based only on resistance to US races.

Stem rust resistance in durum wheat relies on a limited number of major genes and adult plant resistance (APR) genes that have not been reported to be widely used in modern cultivars. Very few studies have described the presence of adult plant or slow rusting resistance in durum wheat (Hare, 1997; Hei et al., 2015; Toor et al., 2009), indicating the potential for identifying new APR resistance genes that will help improve durability of stem rust resistance. For example, Sr2, the most important APR gene in common wheat was transferred from Yaroslav emmer (McFadden, 1930), the tetraploid wheat progenitor of cultivated durum. To identify accessions with potential new APR genes, we are in the process of characterizing these resistant to moderately susceptible accessions using a wide range of Pgt races, including those used in both nurseries. Resistant accessions that exhibit susceptible reaction in all seedling evaluations can be investigated for the presence of APR. As the phenotypic effect of APR genes is relatively minor, it is expected that accessions carrying an APR gene would not exhibit a strong resistant response. For this reason, accessions consistently exhibiting a moderately susceptible response, with a relatively low disease severity (≤30% stem rust terminal disease severity), were included in our selection group for further studies on APR.

Seedling evaluations with multiple stem rust races, in combination with marker analysis, are needed to allow a relatively accurate postulation of the known major resistance genes deployed in durum wheat. Genotyping of the 491 resistant to moderately susceptible accessions with a 90K SNP platform is planned to identify and map new quantitative trait loci associated with stem rust resistance.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The results from this study demonstrated that durum wheat accessions deposited at the USDA National Small Grains Collection provided a good and diverse source of stem rust resistance. Four hundred and ninety‐one accessions were found to exhibit a resistant to moderately susceptible response after five field evaluations in Debre Zeit (Ethiopia) and St. Paul, Minnesota (USA). These accessions could be exploited for improvement of stem rust resistance in both durum and common wheat. A higher level and frequency of resistance was observed in cultivars and breeding lines compared with landraces. The landraces from different geographic origins have the potential to contribute a diverse source of new genes. Seedling evaluations and genotyping of these resistant germplasms will facilitate the characterization and mapping of effective stem rust resistance genes that can be incorporated into adapted backgrounds.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Pablo D. Olivera: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing‐original draft, Writing‐review & editing; Worku D. Bulbula: Investigation, Writing‐review & editing; Ayele Badebo: Investigation, Writing‐review & editing; Harold E. Bockelman: Resources, Writing‐review & editing; Erena A. Edae: Formal analysis,Software,Visualization; Yue Jin: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing‐review & editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table S1: Origin and improvement status of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) accessions evaluated for stem rust field resistance.

Supplementary Table S2. Disease severity, infection response, and COI of 491 durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) evaluated stem rust field nurseries at Debre Zeit (Ethoipia) and St. Paul, MN (USA)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by USDA‐ARS, and the Durable Rust Resistance in Wheat (DRRW‐OPPGD1389) and Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat (DGGW‐OPP1133199) projects administrated by Cornell University and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Kingdom Department for International Development. The authors acknowledge Samuel Gale, Melissa Prenevost, GebreHiwot Abraha, and Ashenafi Gemechu for their technical assistance.

Olivera PD, Bulbula WD, Badebo A, Bockelman HE, Edae EA, Jin Y. Field resistance to wheat stem rust in durum wheat accessions deposited at the USDA National Small Grains Collection. Crop Science. 2021;61:2565–2578. 10.1002/csc2.20466

Assigned to Associate Editor Sivakumar Sukumaran.

Contributor Information

Pablo D. Olivera, Email: oliv0132@umn.edu.

Yue Jin, Email: yue.jin@usda.gov.

REFERENCES

- Admassu, B., Lind, V., Friedt, W., & Ordon, F. (2009). Virulence analysis of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici populations in Ethiopia with special consideration to Ug99. Plant Pathology, 58, 362–369. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2008.01976.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akond, A. S. M. G. M., & Watanabe, N. (2005). Genetic variation among Portuguese landraces of ‘Arrancada’ wheat and Triticum petropavlovskyi by AFLP‐based assessment. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 52, 619–628. 10.1007/s10722-005-6843-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alemu, A., Feyissa, T., Letta, T., & Abeyo, B. (2020). Genetic diversity and population structure analysis based on the high‐density SNP markers in Ethiopian durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum). BMC Genetics, 21, 18. 10.1186/s12863-020-0825-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altıntaş, S., Toklu, F., Kafkas, S., Kilian, B., Brandolini, A., & Özkan, H. (2008). Estimating genetic diversity in durum and bread wheat cultivars from Turkey using AFLP and SAMPL markers. Plant Breeding, 127, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Amogne, S., Dawit, W., & Andenow, Y. (2000). Stability of stem rust resistance in some Ethiopian durum wheat varieties. In CIMMYT. 2000. The eleventh regional wheat workshop for Eastern, Central, and Southern Africa. (pp. 164–168). International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center. [Google Scholar]

- Ataullah, M. (1963). Genetics of rust resistance in tetraploid wheats. II. New sources of stem rust resistance. Crop Science, 3, 484–486. 10.2135/cropsci1963.0011183X000300060008x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beteselassie, N., Finisa, C., & Badebo, A. (2007). Sources of stem rust resistance in Ethiopian tetraploid wheat accessions. African Crop Science Journal 15, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S. (2017). Deadly new wheat disease threatens Europe's crops. Nature, 542, 145–146. 10.1038/nature.2017.21424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonman, M. J., Bockleman, H. E., Jin, Y., Hijmans, R. J., & Gironella, A. I. N. (2007). Geographic distribution of stem rust resistance in wheat landraces. Crop Science, 47, 1955–1963. 10.2135/cropsci2007.01.0028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chao, S., Rouse, M. N., Acevedo, M., Szabo‐Hever, A., Bockelman, H., Bonman, J. M., Elias, E., Klindworth, D., & Xu, S. (2017). Evaluation of genetic diversity and host resistance to stem rust in USDA NSGC durum wheat accessions. Plant Genome, 10(2). 10.3835/plantgenome2016.07.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale, I. L., Mamuya, I., & Singh, D. (2013). Sr31‐virulent races (TTKSK, TTKST, and TTTSK) of the wheat stem rust pathogen Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici are present in Tanzania. Plant Disease, 97, 557. 10.1094/PDIS-06-12-0604-PDN [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare, R. A. (1997). Characterization and inheritance of adult plant stem rust resistance in durum wheat. Crop Science, 37, 1094–1098. 10.2135/cropsci1997.0011183X003700040010x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hei, N., Shimelis, H. A., Laing, M., & Admassu, B. (2015). Assessment of Ethiopian wheat lines for slow rusting resistance to stem rust of wheat caused by Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici . Journal of Phytopathology, 163, 353–363. 10.1111/jph.12329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hovmøller, M. S., Patpour, M., Rodriguez‐Algaba, J., Thach, T., Justesen, A. F., & Hansen, J. G. (2020). GRRC Annual Report 2019: Stem‐ and yellow rust genotyping and race analyses. www.wheatrust.org

- Hundie, B., Girma, B., Tadesse, Z., Edae, E., Firpo Olivera, P. D. , Abera, E. H., Bulbula, W. D., Abeyo, B., Badebo, A., Cisar, G., Brown‐Guedira, G., Gale, S., Jin, Y., & Rouse, M. N. (2019). Characterization of Ethiopian wheat germplasm for resistance to four Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici races facilitated by single race nurseries. Plant Disease, 103, 2359–2366. 10.1094/PDIS-07-18-1243-RE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y., Singh, R. P., Ward, R. W., Wanyera, R., Kinyua, M., Njau, P., Fetch, T., Pretorius, Z. A., & Yahyaoui, A. (2007). Characterization of seedling infection types and adult plant infection responses of monogenic Sr gene lines to race TTKS of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici . Plant Disease, 91, 1096–1099. 10.1094/PDIS-91-9-1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y., Szabo, L. J., Pretorius, Z. A., Singh, R. P., Ward, R., & Fetch T., Jr. (2008). Detection of virulence to resistance gene Sr24 within race TTKS of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici . Plant Disease, 92, 923–926. 10.1094/PDIS-92-6-0923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbaj, H., Sall, A. T., Al‐Abdallat, A., Geleta, M., Amri, A., Filali‐Maltouf, A., Belkadi, B., Ortiz, R., & Bassi, F. M. 2017.. Genetic diversity within a global panel of durum wheat (Triticum durum) landraces and modern germplasm reveals the history of alleles exchange. Frontiers in Plant Science, 8, 1277. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenaschuk, E. O., Anderson, R. G., & Knott, D. R. (1959). The inheritance of rust resistance V. The inheritance of resistance to race 15B of stem rust in ten varieties of durum wheat. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 39, 316–328. 10.4141/cjps59-044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klindworth, D. L., Miller, J. D., Jin, Y., & Xu, S. S. (2007). Chromosomal locations of genes for stem rust resistance in monogenic lines derived from tetraploid wheat accession ST464. Crop Science, 47, 1441–1450. 10.2135/cropsci2006.05.0345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Letta, T., Maccaferri, M., Badebo, A., Ammar, K., Ricci, A., Crossa, J., & Tuberosa, R. (2013). Searching for novel sources of field resistance to Ug99 and Ethiopian stem rust races in durum wheat via association mapping. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 126, 1237–1256. 10.1007/s00122-013-2050-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C. M., Persoons, A., Bebber, D. P., Kigathi, R. N., Maintz, J., Findlay, K., Corredor‐Moreno, P., Harrington, S. A., Kangara, N., Berlin, A., Garcia, R., German, S. E., Hanzalova, A., Hodson, D., Hovmøller, M. S., Huerta‐Espino, J., Imitaz, M., Iqbal Mirza, J., Justesen, A. F., … Saunders, D. G. O. (2018). Potential for re‐emergence of wheat stem rust in the United Kingdom. Communications Biology, 1, 13. 10.1038/s42003-018-0013-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luig, N. H. (1983). A survey of virulence genes in wheat stem rust Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici . Advances in Plant Breeding, 11, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri, M., Sanguineti, M. C., Donini, P., Porcedu, E., & Tuberosa, R. (2005). A retrospective analysis of genetic diversity in durum wheat elite germplasm based on microsatellite analysis: A case study. In Royo C., Nachit M. N., Di Fonzo N., Araus J. L., Pfeiffer W. H., & Slafer G. A. (Eds.), Durum wheat breeding: Current approaches and future strategies (pp. 99–142). Food Products Press. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, E. S. (1930). A successful transfer of emmer characters to vulgare wheat. Journal of the American Society of Agronomy, 22, 1020–1034. 10.2134/agronj1930.00021962002200120005x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, R. A., Wellings, C. R., & Park, R. F. (1995) Wheat rusts: An atlas of resistance genes. Kluwer Academy Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mengistu, D. K., Kiros, A. Y., & Pe, M. E. (2015). Phenotypic diversity in Ethiopian durum wheat (Triticum turgidum var. durum) landraces. The Crop Journal, 3, 190–199. 10.1016/j.cj.2015.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miedaner, T., Rapp, M., Flath, K., Longin, C. F. H., & Wurschum, T. (2019). Genetic architecture of yellow and stem rust resistance in a durum wheat diversity panel. Euphytica, 215, 71. 10.1007/s10681-019-2394-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb, M., Olivera, P. D., Rouse, M. N., Szabo, L. J., Johnson, J., Gale, S., Luster, D. G., Wanyera, R., Macharia, R., Bhavani, S., Hodson, D., Patpour, M., Hovmøller, M. S., Fetch T. G., Jr., & Jin, Y. (2016). Characterization of Kenyan isolates of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici from 2008 to 2014 reveals virulence to SrTmp in the Ug99 race group. Phytopathology, 100, 986–996. 10.1094/PHYTO-12-09-0349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirmala, J., Saini, J., Newcomb, M., Olivera, P., Gale, S., Klindworth, D., Elias, E., Talbert, L., Chao, S., Faris, J., Xu, S., Jin, Y., & Rouse, M. N. (2017). Discovery of a novel stem rust resistance allele in durum wheat that exhibits differential reactions to Ug99 isolates. G3, 7(10), 3481–3490. 10.1534/g3.117.300209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera, P. D., Badebo, A., Xu, S. S., Klindworth, D. L., & Jin, Y. (2012a). Resistance to race TTKSK of Puccinina graminis f. sp. tritici in emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. dicoccum). Crop Science, 52, 2234–2242. 10.2135/cropsci2011.12.0645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera, P. D., Jin, Y., Rouse, M., Badebo, A., Fetch, T.,Jr., Singh, R. P., & Yahyaoui, A. (2012b). Races of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici with combined virulence to Sr13 and Sr9e in a field stem rust screening nursery in Ethiopia. Plant Disease, 96, 623–628. 10.1094/PDIS-09-11-0793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera, P. D., Newcomb, M., Szabo, L. J., Rouse, M. N., Johnson, J., Gale, S., Luster, D. G., Hodson, D., Cox, J. A., Burgin, L., Hort, M., Gilligan, C. A., Patpour, M., Justesen, A. F., Hovmøller, M. S., Woldeab, G., Hailu, E., Hundie, B., Tadesse, K., … Jin, Y. (2015). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of race TKTTF of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici that caused a wheat stem rust epidemic in southern Ethiopia in 2013/14. Phytopathology, 105, 917–928. 10.1094/PHYTO-11-14-0302-FI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera, P. D., Sikharulidze, Z., Dumbadze, R., Szabo, L. J., Newcomb, M., Natsarishvili, K., Rouse, M. N., Luster, D. G., & Jin, Y. (2019). Presence of a sexual population of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici in Georgia provides a hotspot for genotypic and phenotypic diversity. Phytopathology, 119, 2152–2160. 10.1094/PHYTO-06-19-0186-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera Firpo, P. D., Newcomb, M., Flath, K., Szabo, L. J., Carter, M., Luster, D. G., & Jin, Y. (2017). Characterization of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici isolates derived from an unusual wheat stem rust outbreak in Germany in 2013. Plant Pathology, 66, 1258–1266. 10.1111/ppa.12674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quamar, Z., Bansal, U. K., & Bariana, H. (2009). Genetics of stem rust resistance in three durum wheat cultivars. International Journal of Plant Breeding, 3, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Patpour, M., Hovmøller, M. S., Hansen, J. G., Justesen, A. F., Thach, T., Rodriguez‐Algaba, J., Hodson, D., & Randazo, B. (2018). Epidemics of yellow rust and stem rust in southern Italy 2016–2017: BGRI 2018 Technical Workshop. https://www.globalrust.org/content/epidemics‐yellow‐and‐stem‐rust‐southern‐italy‐2016‐2017.

- Patpour, M., Justesen, J., Tecle, A. W., Yazdani, M., Yasaie, M., & Hovmøller, M. S. (2020). First report of race TTRTF of wheat stem rust (Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici) in Eritrea. Plant Disease, 104, 973. 10.1094/PDIS-10-19-2133-PDN [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pecetti, L., Annicchiarico, P., & Damania, A. B. (1992). Biodiversity in a germplasm collection of durum wheat. Euphytica 60, 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R. F., Campbell, A. B., & Hannah, A. E. (1948). A diagrammatic scale for estimating rust intensity of leaves and stem of cereals. Canadian Journal of Research, 26, 496–500. 10.1139/cjr48c-033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pozniak, C. J., Reimer, S., Fetch, T., Clarke, J. M., Clarke, F. R., Somers, D., Knox, R. E., & Singh, A. K. (2008). Association mapping of Ug99 resistance in a diverse durum wheat population. In Appels R., Eastwood R., Lagudah E., Langridge P., Mackay M., McIntyre L., & Sharp P. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th International Wheat Genetics Symposium (pp. 485–487). Sydney University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius, Z. A., Singh, R. P., Wagoire, W. W., & Payne, T. S. (2000). Detection of virulence to wheat stem rust resistance genes Sr31 in Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici in Uganda. Plant Disease, 84, 2003. 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.2.203B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfs, A. P. (1985). Wheat and rye stem rust. In Roelfs A. P., & Bushnell W. R. (Eds.), The cereal rusts Vol. II: Diseases, distribution, epidemiology and control (pp. 4–37). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roelfs, A. P., & Martens, J. W. (1988). An international system of nomenclature for Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici . Phytopathology, 78, 526–533. 10.1094/Phyto-78-526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfs, A. P., Singh, R. P., & Saari, E. E. (1992). Rust diseases of wheat, concepts and methods of disease management. International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center. [Google Scholar]

- Saari, E. E., & Prescott, J. M. (1985). World distribution in relation to economic losses. Wheat and rye stem rust. In Roelfs A. P., & Bushnell W. R. (Eds.), The cereal rusts Vol. II: Diseases, distribution, epidemiology and control (pp. 259–298). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shamanin, V. P., Pototskaya, I. V., Shepelev, S. S., Pozherukova, V. E., Salina, Е. А., Skolotneva, Е. S., Hodson, D., Hovmøller, M., Patpour, M., & Morgounov, A. I. (2020). Stem rust in western Siberia – race composition and effective resistance genes. Vavilov Journal of Genetics and Breeding, 24, 131–138. 10.18699/VJ20.608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons, K., Abate, Z., Chao, S., Zhang, W., Rouse, M. N., Jin, Y., Elias, E., & Dubcovsky, J. (2011). Genetic mapping of stem rust resistance gene Sr13 in tetraploid wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum L). Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 122, 649–658. 10.1007/s00122-010-1444-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R. P., Bechere, E., & Abdalla, O. (1992). Genetic analysis of resistance to stem rust in durum wheats. Phytopathology, 82, 919–922. 10.1094/Phyto-82-919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R. P., Hodson, D. P., Jin, Y., Lagudah, E. S., Ayliffe, M. A., Bhavani, S., Rouse, M. N., Pretorius, Z. A., Szabo, L. J., Huerta‐Espino, J., Basnet, B. R., Lan, C., & Hovmøller, M. S. (2015). Emergence and spread of new races of wheat stem rust fungus: Continued threat to food security and prospects of genetic control. Phytopathology, 105, 872–884. 10.1094/PHYTO-01-15-0030-FI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovmand, B., & Rajaram, S. (1990). Utilization of genetic resources in the improvement of hexaploid wheat. In Srivastava J. P., & Damania A. B. (Eds.), Wheat genetic resources: Meeting diverse needs (pp 259–268). J. Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Skovmand, B., Warburton, M. L., Sullivan, S. N., & Lage, J. (2005). Managing and collecting genetic resources. In Royo C., Nachit M., Di Fonzo N., Araus J. L., Pfeiffer W. H., & Slafer G. A. (Eds.), Durum wheat breeding: Current approaches and future strategies. (pp. 143–163). Food Products Press. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, J. M., Villegas, D., Aranzana, M. J., Garcia del Moral, L. F., & Royo, C. (2016). Genetic structure of modern durum wheat cultivars and Mediterranean landraces matches with their agronomic performance. PLOS ONE, 11(8), e0160983. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, R. W., Prescott, J. M., Saari, E. E., & Dubin, H. U. (1986). Cereal disease methodology manual. International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center. [Google Scholar]

- Toor, A. K., Bansal, U. K., & Bariana, H. S. (2009). Identification of new sources of adult plant stem rust resistance in durum wheat. In 14th Australasian Plant Breeding & 11th SABRAO Conference (p. 6).

- Villa, T. C. C., Maxted, N., Scholten, M., & Ford‐Lloyd, B. (2006). Defining and identifying crop landraces. Plant Genetic Resources, 3, 373–384. 10.1079/PGR200591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanyera, R., Kinyua, M. G., Jin, Y., & Singh, R. (2006). The spread of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici with virulence on Sr31 in eastern Africa. Plant Disease, 90, 113. 10.1094/PD-90-0113A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W., Chen, S., Abate, Z., Nirmala, J., Rouse, M. N., & Dubcovsky, J. (2017). Identification and characterization of Sr13, a tetraploid wheat gene that confers resistance to the Ug99 stem rust race group. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 114, E9483–E9492. 10.1073/pnas.1706277114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: Origin and improvement status of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) accessions evaluated for stem rust field resistance.

Supplementary Table S2. Disease severity, infection response, and COI of 491 durum wheat (Triticum turgidum sp. durum) evaluated stem rust field nurseries at Debre Zeit (Ethoipia) and St. Paul, MN (USA)