Abstract

The loss of proteostasis over the life course is associated with a wide range of debilitating degenerative diseases and is a central hallmark of human aging. When left unchecked, proteins that are intrinsically disordered can pathologically aggregate into highly ordered fibrils, plaques, and tangles (termed amyloids), which are associated with countless disorders such as Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, Type II Diabetes, cancer, and even certain viral infections. However, despite significant advances in protein folding and solution biophysics techniques, determining the molecular cause of these conditions in humans has remained elusive. This has been due, in part, to recent discoveries showing that soluble protein oligomers, not insoluble fibrils or plaques, drive the majority of pathological processes. This has subsequently led researchers to focus instead on heterogeneous and often promiscuous protein oligomers. Unfortunately, significant gaps remain in how to prepare, model, experimentally corroborate, and extract amyloid oligomers relevant to human disease in a systematic manner. This review will report on each of these techniques and their successes and shortcomings in an attempt to standardize comparisons between protein oligomers across disciplines, especially in the context of neurodegeneration. By standardizing multiple techniques and identifying their common overlap, a clearer picture of the soluble neuropathological aggresome can be constructed and used as a baseline for studying human disease and aging.

Keywords: amyloids, amyloid proteins, amylome, aggresome, oligomers, aggregates, fibrils, Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, soluble oligomers, intrinsically disordered proteins, molecular dynamics simulations, protein folding, replica-exchange molecular dynamics, fluorescence spectroscopy, smFRET, FCS, DLS, NMR, size-exclusion chromatography, SDS-PAGE, solution biophysics, amyloid-beta, alpha-synuclein, immunoprecipitation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Most proteins in the human body follow a tightly regulated sequence of events that span ribosomal synthesis, acquisition of structure, interaction with environments, and degradation through proteolysis.1–2 These events can take days or even years to occur in standard proteins,3 however the trajectories of misfolded or intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) are much more complex and are often associated with a wide range of human degenerative disorders.4–5 In eukaryotic cells, for example, misfolded proteins are either ubiquitinated for disposal or digested by lysosomes,1 however they can also aggregate into insoluble complexes that resist degradation.6 Thus, when the capacity of the proteosome is overtaken by misfolded protein aggregates, the formation of an aggresome emerges, which is thought to be a general feature of cells.7 IDPs, which lack stable secondary/tertiary structures, also present regulatory complications due to their promiscuity with multiple binding partners and their ability to interconvert between disparate conformations, thereby leading to pathological aggregates known as amyloids.4–5 While the proportion of pathological aggregates within the proteosome is likely small, recent extensions to human lifespan and the shift to older populations have emphasized that the aggresome plays a key role in nearly every age-related disease,8–13 necessitating an in-depth review of the biophysics of pathological aggregates across in silico, in vitro, and ex vivo systems.

The prototypical aggresome was first described over 100 years ago by Alois Alzheimer regarding observations of “miliary bodies” and “dense bundles of fibrils” in post-mortem brain tissue,14 though it wasn’t until the 1980s that the amyloid hypothesis began gaining momentum.15 Once the constituent proteins of pathological plaques were purified and sequenced,15–16 researchers were certain that amyloid-β aggregates caused neurodegeneration, which was further supported by the identification of familial mutations linked to disease in amyloid precursor proteins and their enzymes.17–22 However, a number of high-profile clinical trials aimed at reducing amyloid-β expression famously failed to have an impact on disease severity,23 leading to a reappraisal of the aggresome and its effect on human health and aging.14, 24–29 Subsequent research in Alzheimer’s disease has largely been fragmented,30–31 with some studies suggesting that disordered tau proteins, not amyloid-β, are the dominant drivers of neurological diseases.24, 32–33 Other research directions have focused on mutations in non-amyloid proteins, such as apolipoproteins, which are linked to late-onset neurodegeneration.34–36 Despite these differences, much attention had been focused predominantly on insoluble fibrils and plaques, which were later found to be poor indicators of disease severity.37–38 Instead, soluble protein oligomers39 complexed to lipids40–44 or metals45–48 appeared to be more highly correlated with disease incidence and memory loss,49–51 indicating that environmental factors are key determinants of amyloid pathogenicity.

Despite a large body of research, it remains unclear how to compare soluble protein aggregates with kinetic diversity52 across different experiments, and whether environmental factors are adequately taken into account. Molecular models, while increasingly sophisticated, often rely on experimental fibril structures to validate if the choice of force field or simulation parameters are sufficient to recapitulate amyloid behaviors. However, the validity of intermediate oligomers is much more difficult to deduce since aggregates can form through multiple processes, many of which are not relevant to biological systems. This includes incomplete fibril formation (insufficient sampling), enhanced complexation due to finite simulation volumes (maximum entropy), or through environmental determinants that stabilize oligomers and inhibit their subsequent growth (thermodynamic equilibrium). Each of these structures, no matter how they come about, should be validated against negative (monomers) and positive (fibrils) controls to ensure that oligomers are distinct and not simply a byproduct of poor models that complex all proteins alike. Furthermore, many simulations employ single-component solvents,53–55 which omit key constituents that stabilize pathological subspecies. Simulations have, however, been extraordinarily valuable at shedding light on the biophysics of various amyloid constructs, though correlations between in silico amyloids and patient-derived structures, for example, can be vastly improved. Similarly, multiple solution biophysical protocols are routinely utilized (Table 1) to solubilize protein aggregates using a wide variety of stabilizers,43–44, 48, 56 however products are highly sensitive to protein purity,57 organic solvents,58–60 pH,61–62 salt,63–64 and the presence of lipids.40, 43, 65 Complicating matters further, many standard biophysical techniques such as gel electrophoresis or size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) fail to adequately characterize amyloid oligomers.66–68 As a result, single-molecule methods, such as single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET), have emerged as powerful new tools to overcome these challenges and distinguish the structural and dynamic heterogeneity of protein oligomers. Therefore, we include an in-depth discussion of how neuropathological amyloids from ensemble observations differ markedly from single molecule experiments. Finally, while multiple protocols are used to extract patient-derived amyloid oligomers from biopsy or post-mortem tissues,69–71 we review discrepancies in these techniques (such as the choice of detergents) that can indirectly perturb the dynamic structures one wishes to measure. Taken together, these factors provide useful variables that can be standardized when comparing the aggresome between different experiments and disciplines with the expectation of better understanding amyloid diseases and their shared molecular determinants.

Table 1.

Divergent experimental conditions for preparing soluble aβ oligomers from synthetic/recombinantly expressed peptides. Typically, this involves four steps: (1) A monomerization or disaggregation step using hydrogen bond disrupting solvents such as polyfluorinated alcohols (e.g., hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP)) or strong bases such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Temperature, time, vortexing, sonicating, and method of removal represent additional researcher degrees of freedom in this step. This step is aimed at breaking down pre-existing aggregates and erasing the structural history of monomers. (2) After these solvents are removed the resulting peptide film is reconstituted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or directly into the incubation buffer. (3) Ostensibly monomeric peptides are incubated in varying milieu and concentrations, at varying temperatures, and for varying durations. These protocols may involve one, or two distinct incubation steps. (4) Protocols may directly observe aliquots at time points along the reaction or may filter to enrich for certain species of oligomers.

| Species/Ref | Peptide | Monomerization | Reconstitution | Incubation | Filtration for oligomer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADDL314 | AB42 | 1 mM peptide HFIP | 5 mM peptide DMSO | < 100 μM peptide. F12 medium without phenol red. 5°C, 24 h. |

Centrifuge (retain supernatant) |

| AB42 globulomer44 | AB42 | 6 mg/mL (ca 1.3 mM) peptide HFIP | 5 mM peptide DMSO | 400 μM peptide. (1) PBS pH 7.4 + 0.2% SDS. 37°C, 6 h. (2) 0.25x dilution milliQ (PBS ph7.4 + 0.2% SDS). 37 °C, 18 h |

Centrifuge (retain supernatant) Ultrafiltration (30k MWCO) Dialysis (20k MWCO) |

| ABO315 | AB40, AB42 | 1 mg/mL (ca. 220 μM) peptide 2 mM NaOH pH ca. 10.5 | Same as incubation | 1 mg/mL (ca. 220 μM) peptide (1: seed) PBS pH 7.4 37°C 48 h (2) PBS pH 7.4 37°C 48 h + 5% seed |

0.22 μm spin filtration or 100 kDa MWCO filter |

| Zn2+-stabilized oligomers.48 | AB40 | 3.33 mg/mL (ca. 730 μM) peptide | 5 mM peptide DMSO | 100 μM peptide PBS pH 6.9 200 μM ZnCl2 20°C 20 h |

Centrifuge (retain pellet) |

MOLECULAR MODELS OF THE AGGRESOME

Early Amyloid Predictors and Analytical Models

Some of the earliest efforts to predict aggresomal behaviors from protein sequences alone began with statistical physical models, such as Boltzmann statistics, which could empirically describe a conformational partition function for proteins and the likelihood of adopting secondary structures over a limited number of amino acids. Using such a technique allowed protein subregions to be scanned for the likelihood that short fragments would sample compact β-sheets in a hydrophobic environment, thereby mimicking the interior of pathological amyloids. This technique proved to be successful for the ab initio prediction of protein fibrils, and a number of successful implementations, such as TANGO72 and WALTZ73, were used to analytically confirm the aggregation propensities of amyloid-beta and its many pathological mutants.72 Following these early successes, improved predictors were developed by the Vendruscolo and Dobson groups, such as Zyggregator,74 which derived a Z-score from both the protein’s sequence and folded conformations, emphasizing the inclusion of protein folding data to help predict putative aggregates. Other tools included heuristic information, such as PASTA,75 which considered pair-wise interactions in globular protein cores to inform the optimal interdigitation of protein side-chains in β-sheets. However, each of these predictors relied heavily on amino acid sequences, and often overlooked heterogeneities and subtle differences between in vitro and in vivo amyloid fibrils.76–77

In an effort to move away from predictors that relied heavily on sequence, contemporary predictors were constructed to focus instead on the likelihood that a sequence and structure can form minimal fibrillar units, such as a steric zipper,78–79 consisting of a complimentary β-sheet that forms the spine of an amyloid fibril. This approach is significantly more robust than prior methods because it can be informed from multiple homology models and can predict disparate amyloid fibrils with unique fibrillar units. To that end, the Eisenberg group developed a steric-zipper predictor termed the 3D-profile method,80 which utilizes the Rosetta81 software suite to thread six amino acids at-a-time onto an experimentally-determined hexapeptide (NNQQNY), which was deemed a minimal fibrillar unit (Figure 1). The stabilities of all potential hexapeptides were subsequently deposited in a public database of putative amyloid structures (ZipperDB), which is accessible via a web portal, and which is used to predict the likelihood that a protein subregion interconverts into a steric zipper.82 Such tools and databases have been instrumental in identifying the amylome83 or potential pharmacophores in amyloid fibrils, which can often be manipulated with small molecule inhibitors84–86 or peptides.87–88

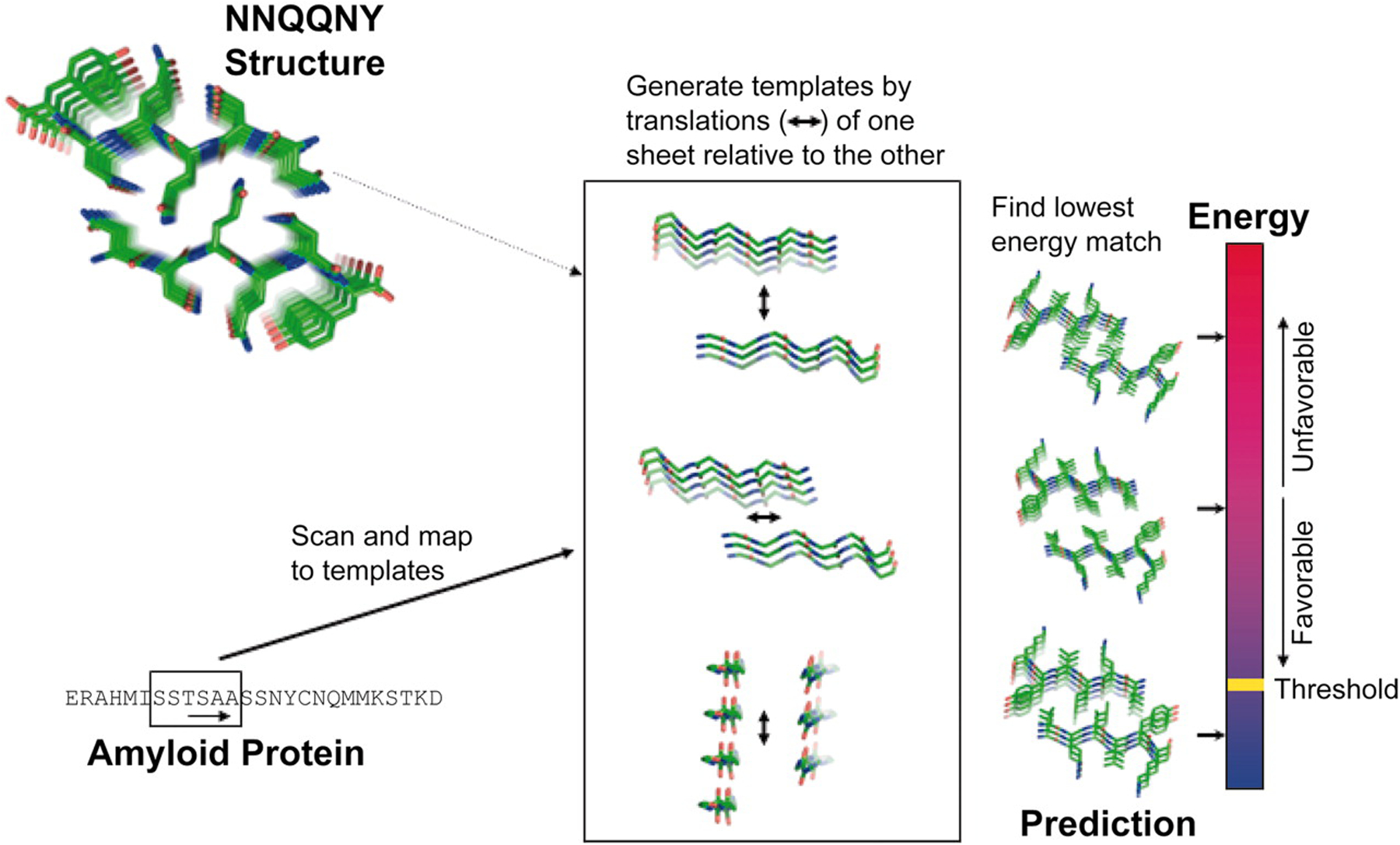

Figure 1.

A workflow depicting the 3D profile method, which (left) reads a protein sequence six residues-at-a-time and threads the amino acids onto an experimentally determined NNQQNY steric zipper backbone, (middle) adjusts XYZ in order to create a grid of relative orientations, and (right) utilizes RosettaDesign to energetically score each complex, take the minimum value, and compare this to a heuristic threshold that dictates amyloidogenicity. Reprinted with permission from Thompson et al.80 Copyright 2006 National Academy of Sciences.

Analytical models have also been used to predict protein aggregation by taking into account the entropic ability of amphiphiles to spontaneous aggregate into both fibrils and metastable oligomers. For example, models proposed by the Knowles89 and Klenerman90 labs have successfully recapitulated Monte Carlo simulations and single-molecule FRET data describing small Aβ oligomers, which is distinct from prior models that focused almost exclusively on insoluble fibrils. Additionally, Iljina et al.90 describes thresholds for analytically-derived critical aggregation concentrations (CACs), similar to critical micelle concentrations (CMCs), which provide protein concentration thresholds necessary to nucleate metastable oligomers and fibrils. While sophisticated, many of these formalisms do not consider potential protein-binding partners such as lipids and cannot easily accommodate experimental complexities. These include heat, co-solvents, or pH, which are often required in experiments to nucleate the formation of amyloid oligomers. It remains to be seen, however, whether these factors are obligates for pathological aggregation, or if their utility is to simply speed up naturally occurring reactions.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Increasingly, numerical techniques such as molecular dynamics (MD) simulations91–93 have begun to fill the gaps between analytical models of the aggresome and solution biophysics experiments containing amyloid oligomers, fibrils, and lipids.94–96 In MD, equations of motion derived from classical physical laws allows for the atomistic simulation of protein oligomers and fibrils, often beginning from dilute monomers. However, the timescales of simulations range from nanoseconds to microseconds, while the timescales of in vitro protein oligomerization and aggregation can occur over minutes to hours in solution. It remains challenging to evaluate protein oligomers and whether such structures are on-pathway to fibrilization (e.g. pre-fibrillar oligomers) or off-pathway intermediates that are metastable. These challenges are further compounded by the choice of molecular force fields, which can yield fundamentally distinct protein oligomers.97–98 Other obstacles include recapitulating experimentally consistent fibrils as a positive control, which is often unsuccessful, thereby complicating the evaluation of oligomers from other types of aggregates or condensates. Nonetheless, many important MD simulations have revealed detailed information about the aggresome such as the structures of amyloid dimers,96 the effects of pH on aggregation,99–100 how truncations in sequence affect aggregation,101 free energy landscapes of amyloid monomers and fibrils,76, 102–103 and how precursor proteins affect downstream aggregation.104 Early work in the Nussinov lab, for example, found that many Aβ fragments prefer anti-parallel β-sheet conformations,105 in addition to a number of annular intermediates106 and polymorphisms.107 Additionally, chemical reaction kinetics deduced by Linse and co-workers108 indicated that the average time for some Aβ oligomers to form is on the order of 3 us, suggesting that microsecond simulations may be capable of recapitulating the early stages of protein aggregation.

Despite difficulties in modeling the evolution of monomers to fibrils in MD, a number of enhanced-sampling techniques have overcome some of these challenges by maximizing the number of oligomeric states sampled in a single simulation, and subsequently reweighting these observations by their energetic costs.33, 109 Garcia and colleagues,110–112 for example, have modeled the aggregation of Aβ using Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) simulations, where they found a wide ensemble of partially folded structures, highlighting the rich conformational diversity of dimers and small amyloid oligomers. Other MD techniques by the Thirumalai lab have used harmonic constraints to speed up the aggregation process,113 where they found that α-helical intermediates nucleate the subsequent formation of antiparallel β-sheets. Similar observations have been observed for diabetes-related amyloids,114–117 where α-helical intermediates are stabilized by lipids and metals.118–120 Nguyen et al. emphasizes that different molecular force fields stabilize vastly different Aβ fibril morphologies in REMD, however the authors also show a general agreement that a two-to-three-stranded β-sheet “oligomer” tends to persist across multiple simulations. Transient β-barrels have also been observed in REMD simulations of β2 microglobulin oligomers,121 indicating that not all pre-fibrillar structures sample α-helical intermediates. Finally, coarse-grained MD simulations, where amino-acids are represented by a wide range of bead models that recapitulate hydrophobic, hydrophilic, zwitterionic, or charged moieties, have also been quite successful at modeling protein aggregation over longer time-scales and at larger length-scales compared to fully atomistic models.122–127 For example, Wang et al.128 utilized the PRIME20 coarse-grain model to deduce thermodynamic phase diagrams of the aggregation-prone Aβ16–22 segment, highlighting the solubilities for different Aβ oligomers and fibrils defined as the equilibrium monomer concentration where aggregates neither grow or shrink. Similarly, this model was used to derived Aβ fibrils from monomers nucleated from amyloid-prone seeds over hundreds of microseconds, which agreed with secondary nucleation kinetics.129 However, the lack of atomistic detail between protein and solvent can sometimes lead to non-physical results.122

MD simulations have also elucidated many of the interactions between amyloid proteins and lipid membranes (Figure 2), where permeabilization of the plasma membrane is frequently observed.130–131 Lemkul et al. was able to extract the insertion depth of Aβ40 in a DPPC bilayer, and the protonation of various residues embedded in the bilayer interior.132 Similarly, Berkowitz showed that the presence of either a zwitterionic or anionic membrane surface was not, by itself, sufficient to convert Aβ monomers into β-stranded structures.133 Instead, Berkowitz suggests that lipid bilayers only sequester amyloid proteins, and it is the high local concentration of amyloid proteins that nucleates fibrilization through protein-protein interactions. In this scenario, lipids are not unique in nucleating pathological oligomers, and indeed other simulations containing zinc have bolstered this hypothesis.134–135 Jang et al. has also modeled the stability of membrane-bound Aβ fibrils, where they observed trimer insertion136 and in some cases membrane permeabilization through the formation of β-amyloid ion channels.137–139 The Strodel lab also found that lipid headgroup charge and tail saturation dictate the transmembrane stability of Aβ42 β-sheets and helices.140 Mixed lipid simulations have also revealed that cytosolic Aβ binding to membrane surfaces recapitulates much of what is observed for the membrane-embedded amyloid precursor protein,141 which precedes the formation of cytosolic Aβ. Simulations of Aβ protofibrils on membranes have also revealed putative ion channels that could be constructed from intermediate oligomers,142–145 suggesting that conformational changes may also take place on the surface of membranes once a critical oligomeric structure is formed.

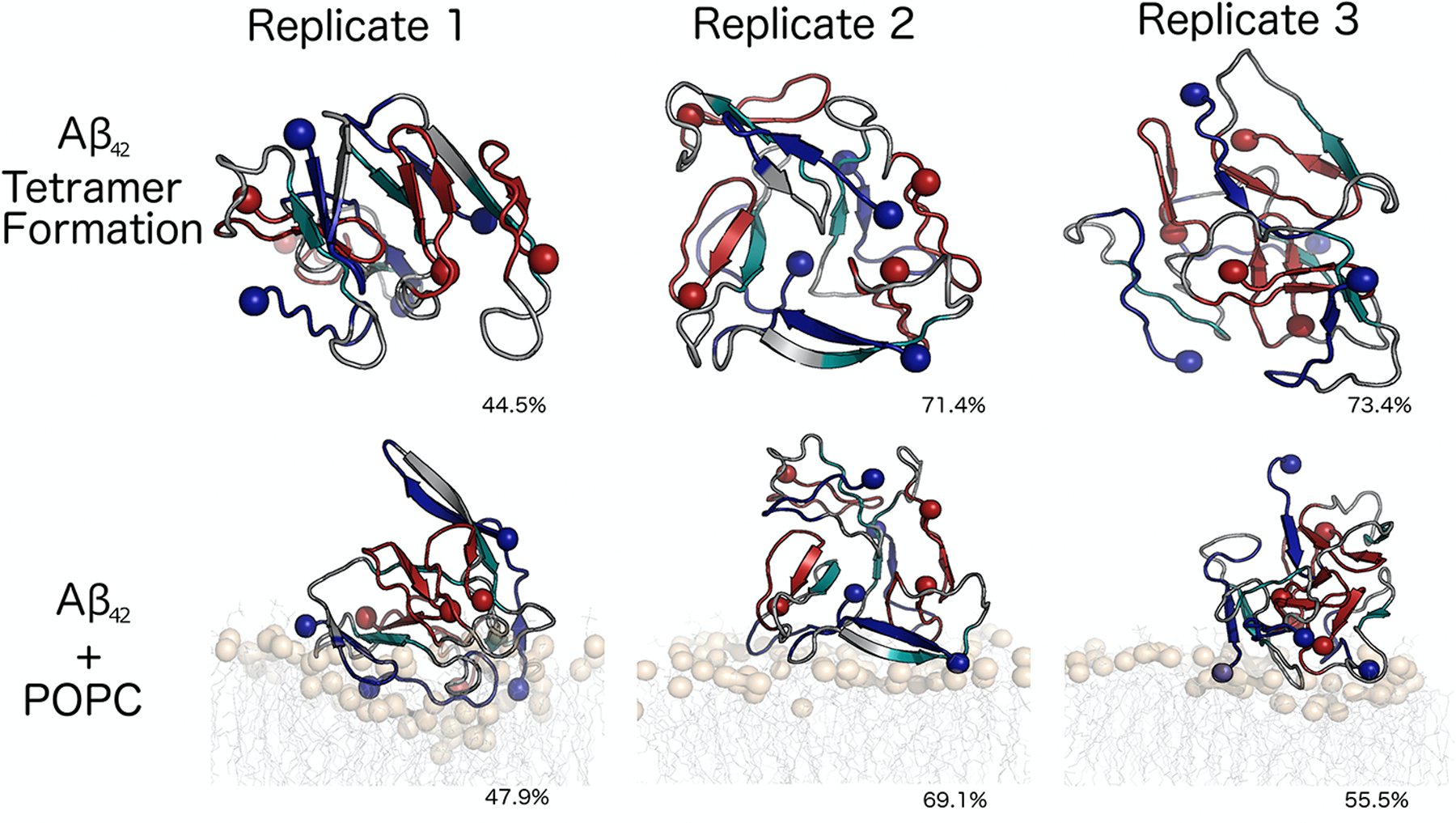

Figure 2.

Microsecond molecular dynamics simulations reveal a number of structurally distinct Aβ42 tetramers on the surface of zwitterionic lipid bilayers, indicating that amyloid oligomers remain heterogeneous on the surface of plasma membranes. Spheres represent N- and C-termini, which do not have a fixed relative-position across multiple simulation replicates. Adapted with permission from Brown and Bevan.316 Copyright 2016 Elsevier.

Kinetic Models of Amyloid Fibril Growth

Kinetic models of protein aggregation have also provided essential details about rare events that are difficult to sample in standard MD simulations.146 The Bolhuis lab has shown that transition path sampling (TPS) can account for fibril formation using a kinetic model where monomers are sequentially added to intact fibrils.147–148 This is somewhat analogous to the two-step dock-lock mechanism coined by Thirumalai and co-workers,149 and later corroborated by Schwierz et al.150–151 using experimental binding affinities. In this model, disordered monomers loosely bind to an ordered substrate (known as the ‘dock’ step), followed by slow rigidification into a fibrillar unit (known as the ‘lock’ step). Simulations have also corroborated the secondary nucleation of amyloid fibrils,152–154 where existing β-sheet surfaces stabilize amyloid monomers and lead to further fibrilization perpendicular to the fibril axis. Other kinetic models, such as forward flux sampling (FFS), use a scaling variable λ to alchemically modify a starting system of monomers (λ=0) and turn them into fibrils (λ=1). However, the choice of such reaction coordinates can be challenging to choose as single determinants of oligomerization. Bolhuis, for example, suggests using the interdigitation (or registration) of amyloid side-chains as a plausible scaling variable,155 though a single variable is unlikely to capture the heterogeneities of oligomers observed in vitro and in vivo. Carballo-Pacheco and Strodel also emphasize95 that there are differences in experimental aggregate concentrations compared to simulations, however it’s challenging to relate the average concentration of oligomers in various regions of a buffer to molecular models, especially when oligomers concentrate near lipids or other sequestering compounds. Similarly, during centrifugation, experimental oligomer concentrations can vary significantly due to loss of a sample on surfaces or filters, making comparisons to simulations challenging. Despite this, simulations have steadily provided considerable advances to our understanding of aggresomal proteins, including insights to related neuropathological proteins such as tau,33, 156 α-synuclein,157 prion protein,158 and huntingtin.159

AMYLOIDS IN A TEST TUBE: BIOPHYSICAL CHARACTERIZATIONS OF THE IN VITRO AGGRESOME:

Given the broad set of considerations presented earlier, we will first review several commonly used biophysical methods for characterizing soluble oligomers. This list of methods is not exhaustive, however, and we refer the reader to a number of excellent reviews on circular dichroism (CD),160 Fourier-Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR),161 solid-state NMR (ssNMR),162 ion-mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS),163 analytical ultracentrifugation,164 and transmission electron microscopy (TEM),165 which we have largely omitted here. Following this review, which largely covers ensemble measurements, we turn next to single-molecule techniques, which are particularly powerful tools for probing aggresomal heterogeneity. This is because protein oligomers can be observed one at a time, without the need for separation or ensemble-averaging. Specifically, we will focus on atomic force microscopy (AFM) and single-molecule fluorescence (SMF), particularly single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET). For information outside of the scope of this review, we refer the reader to a number of in-depth articles on SMF/smFRET and its broad utility in studying disordered proteins.166–170

Ensemble Biophysical/Biochemical Methods

Ensemble Characterization of Oligomeric Surfaces

Thioflavin-T (ThT) is a dye that selectively detects amyloid fibrils,171 and which upon binding to β-sheet structures experiences an orders of magnitude increase in fluorescence quantum yield. Monitoring the ThT fluorescence at time points along the aggregation reaction allows for the quantification of fibril formation. It is typically assumed that oligomers do not bind ThT and oligomers have been identified by their failure to bind the dye. However, the perceived inability of ThT to bind oligomers may actually result from a lower number of binding sites on oligomeric surfaces, rather than an inability to bind ThT.172 Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy measurements have shown that the smallest ThT-active aggregates consist of around 60 amyloid-beta (Aβ) monomers.173 Alternatively, the fluorophores ANS and Bis-ANS are also useful biophysical tools for detecting solvent exposed hydrophobic surfaces, which are distinct from the surfaces detected by ThT.174–175 These dyes are essentially nonfluorescent in water, but exhibit a much higher quantum yield in hydrophobic environments.176 In ensemble averages, sub-populations of oligomers with few fluorophore binding sites can be overwhelmed by the signals from other oligomers with a higher number of binding sites, highlighting their limited utility for deducing heterogeneous oligomer mixtures.

Prefibrillar and fibrillar oligomers can also be identified by conformation-specific antibodies, such as the anti-amyloid oligomer antibody (A11)177 and the anti-amyloid fibril antibody (OC),178 respectively. Intriguingly, these antibodies recognize generic epitopes that do not depend on a particular amino acid sequence, and this common structure among soluble oligomers has been used to argue for a common mechanism of toxicity.177 A11 is suggested to detect out-of-register antiparallel β-sheet structures in prefibrillar assemblies179–181 or α-sheet secondary structures,182 whereas OC identifies in-register parallel β-sheets packed into fibrillar assemblies.179–181 On Western blots, Aβ aggregates ranging in (apparent) size from dimers all the way up to large aggregates of >500 kDa stain with the fibril-specific antibody OC. In contrast, the prefibrillar oligomer-specific antibody A11 stains bands from approximately tetramers up to ~75 kDa.178 Importantly, A11 and OC antibodies recognize broadly overlapping size distributions of oligomers, but which display mutually exclusive epitopes, suggesting size alone cannot uniquely characterize oligomers. Work is ongoing to develop antibodies with specific oligomer-binding properties using rational design methods,183–184 however this continues to be very challenging due to the transient nature and low abundance of oligomers.

Ensemble Characterization of Oligomeric Size or Apparent Molecular Weight

Size-Exclusion Chromatography

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) separates biomolecules/assemblies according to their hydrodynamic size. Biomolecules migrate through a column which is packed with a gel matrix consisting of spherical porous particles with carefully controlled pore size. The mechanism by which separation occurs is the degree to which biomolecules of different sizes are included or excluded from this matrix. Ideally, this depends only on differences in their hydrodynamic size (filtering) rather than their chemical properties. In this case, molecules within the fractionation range of the matrix (e.g., 3 to 70 kDa for Superdex 75) can diffuse into pores and are therefore delayed relative to larger molecules outside the fractionation range, which are excluded from the pores and are eluted first, within the so-called void volume of the column. Subsequently, molecules within the fractionation range are eluted out of the column in order of decreasing size, representing their propensity for entering the pores.

The main advantage (vis-à-vis SDS-PAGE, described below) is the possibility for mild elution conditions that allow for the characterization of assemblies with minimal impact on conformation or oligomeric order. However, SEC is relatively low resolution compared to SDS-PAGE66 and several factors can hamper its interpretation. First, proteins may interact with the gel matrix through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions (Figure 3), resulting in anomalous elution times.185–186 Common approaches to reduce non-steric interactions, such as the addition of salts, arginine, or methanol/ethanol, and modifying the pH to be near the protein’s isoelectric point,186 may modify the distribution of oligomeric states. SEC calibration also assumes that the molecular weight standards and the biomolecules of interest are structurally similar (i.e., globular, spherical) and differences in shape can also have significant effects on elution times.

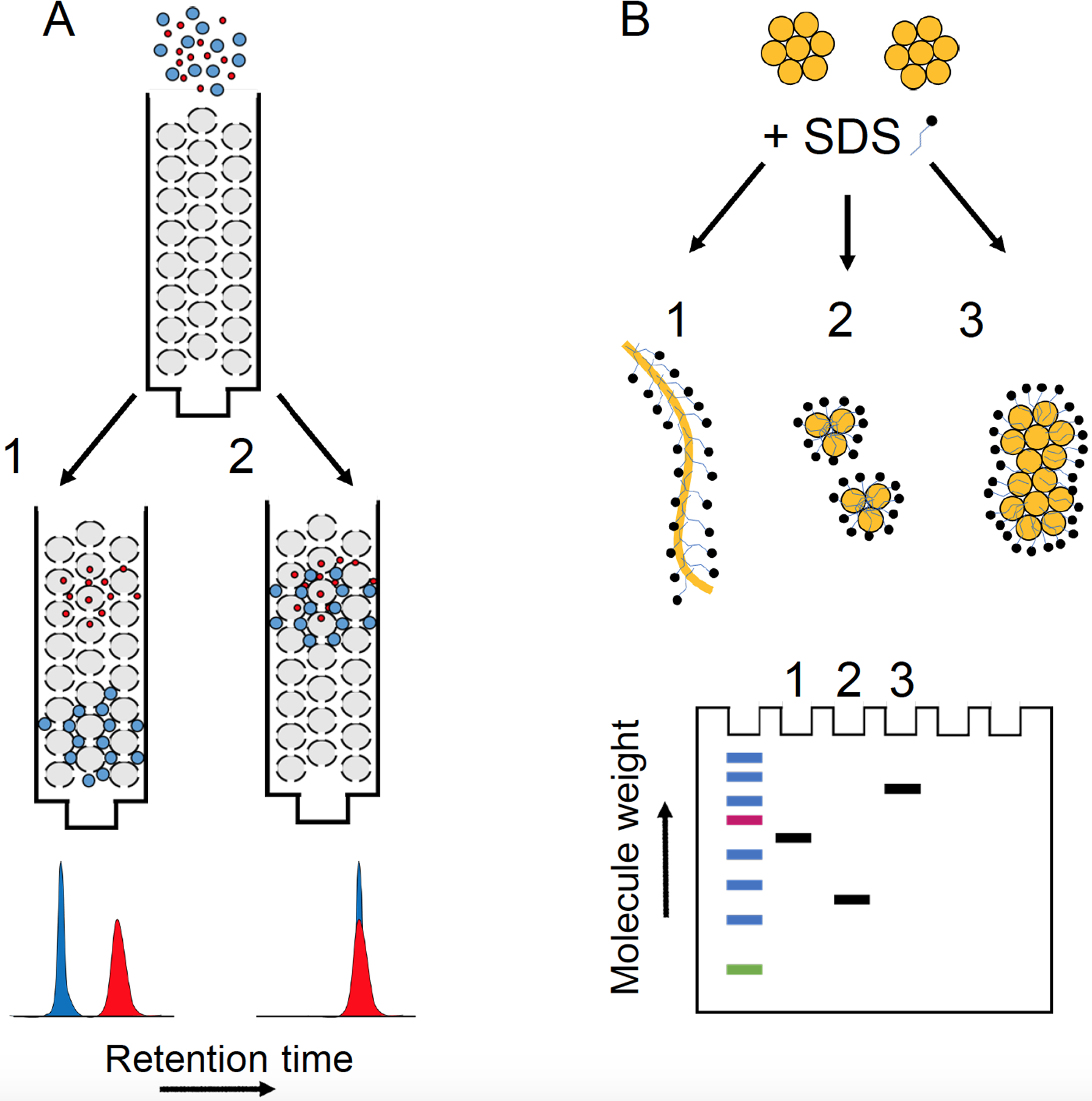

Figure 3.

Size exclusion chromatography (A) and SDS-PAGE (B) under ideal and non-ideal experimental circumstances. (A1) Ideally, retention is determined solely by steric properties such that the larger particles elute first. (A2) Under non-ideal circumstances, retention is based on their interactions with the column media, which in this illustration are similar for the differently sized particles. (B1) Ideally, molecules migrate according to their size (proportional to molecular weight), as SDS binding erases information about charge and shape. Under non-ideal circumstances, SDS binding could promote disaggregation (B2) or aggregation (B3) leading to artifactually lower and higher molecular weight aggregates, respectively.

Dynamic Light Scattering and Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy

In dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments, temporal correlations in the intensity fluctuations of scattered light by particles experiencing Brownian motion are related to their diffusive behaviors (Figure 4). Smaller, more rapidly diffusing particles give rise to rapid fluctuations in intensity, whereas larger, more slowly diffusing particles give rise to slower fluctuations. Notably, DLS measures an intensity-weighted average correlation function, where the scattered intensity is proportional to the sixth power of the particle diameter (the Rayleigh approximation).187 Thus, a 50 nm particle will be weighted 106 times more than a 5 nm particle. Consequently, in an ensemble average, the signal from smaller oligomeric species could be overwhelmed by even a few larger species.

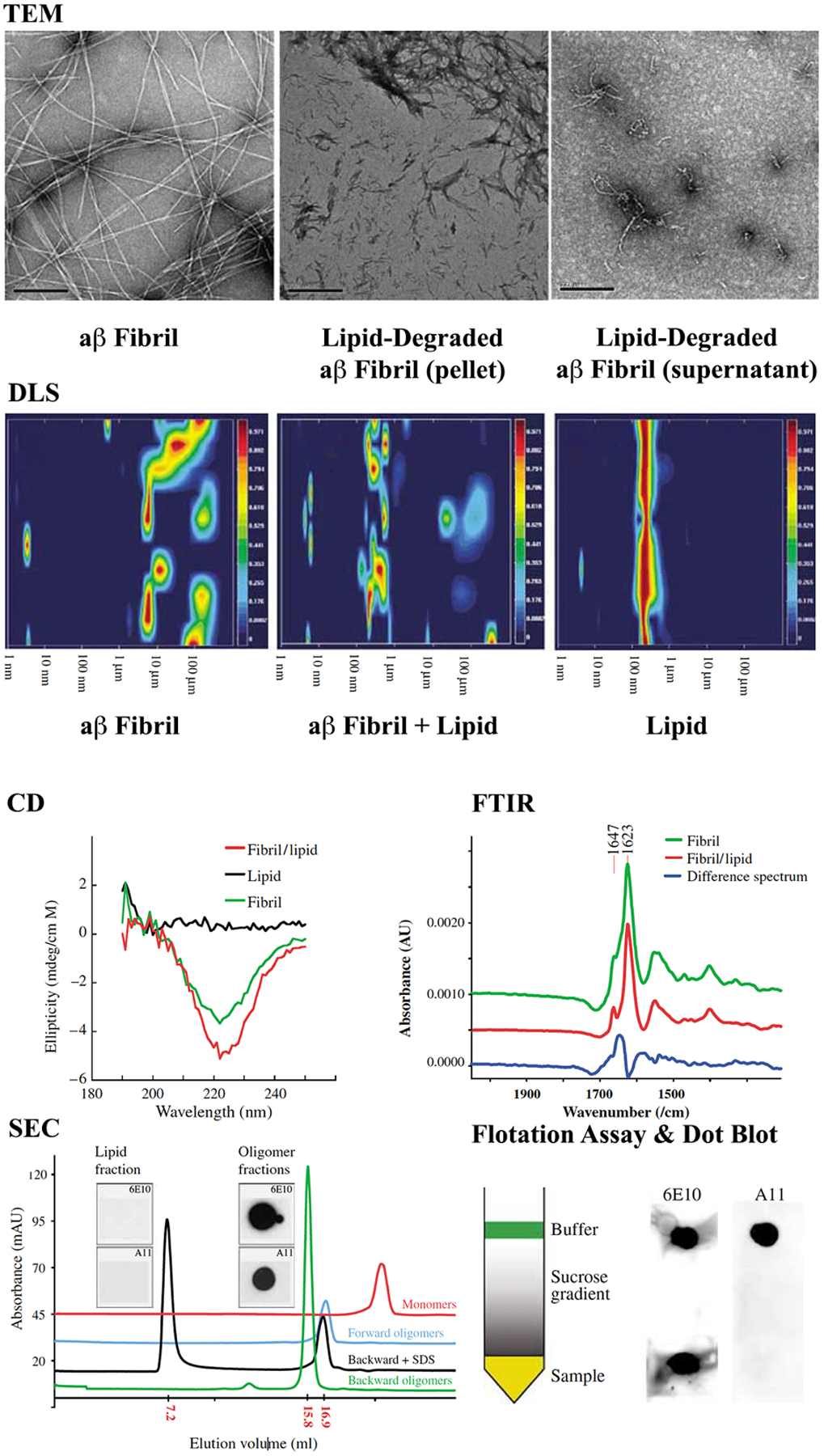

Figure 4.

Standard biophysical assays reveal structural characteristics of soluble Aβ aggregates in forward (monomer-grown) and backward (fibril-degraded) oligomers. While TEM, DLS, CD, and FTIR are useful for discerning oligomer morphology, size, and secondary structure, tools such as SEC or SDS-PAGE can report smaller structures than what is observed in TEM. Adapted with permission from Martins et al.43 Copyright 2007 John Wiley and Sons.

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), like DLS, measures temporal correlations in intensity fluctuations. However, in FCS, it is the fluorescence intensity fluctuations arising from Brownian motions of fluorescently labelled particles that is monitored using a confocal microscope. In FCS, each species contributes to the intensity-weighted correlation function by its fluorescent brightness (proportional to the number of labels). Higher-order multimers therefore contribute equally to lower-order multimers if the number of fluorescent labels is the same.

Whether two species contributing to the correlation function in DLS can be deconvolved into separate peaks with unique size distributions depends greatly on their ratio of sizes and relative fractions, though as a general rule they should differ in radius by a factor of about three or more.188 Similarly, resolving species in FCS depends on the signal to noise ratio, and the differences in size, brightness, and relative amounts. As a general rule, two species should differ in size by at least a factor of two.189 As such, FCS and DLS have limitations in characterizing the size distribution of complex mixtures. For example, the diffusion of a sphere varies inversely by its radius, and therefore for globular particles, as the cube root of its molecular weight (assuming an n1/3 scaling with the number of amino acids n). A globular oligomer would therefore need to gain approximately eight times its own mass for the aforementioned factor of two change in diffusion coefficient. Despite these limitations, FCS and DLS provide valuable information, in particular on the temporal evolution190–191 or stability of assemblies,47 and on their interaction with potential binding partners.192

SDS-PAGE

Although gels are frequently used to characterize the molecular weight of protein aggregates, from which the number of monomers can be inferred, SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) in particular, is not a reliable method to analyze oligomers. Bitan et al.66 performed size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on Aβ preparations in the absence of SDS, and with concentrations of SDS both above and below the critical micellar concentration (CMC), which are typical of SDS-PAGE loading and running buffers, respectively. The SEC results demonstrated that SDS can induce artificial oligomerization of Aβ. Perhaps most strikingly, Hepler et al.193 performed SDS-PAGE on three separate Aβ preparations containing oligomers, monomers, and fibrils, which yielded virtually identical SDS-PAGE profiles. An additional assumption inherent to the determination of molecular weight by SDS-PAGE is that electrophoretic migration is determined solely by mass (chain length), since it is assumed that: (i) proteins bind SDS at a constant SDS:protein weight ratio, masking differences in charge and (ii) SDS denatures proteins rather than inducing or stabilizing structures, masking difference in shape. For membrane proteins,194 intrinsically disordered proteins,195 and especially amphipathic or amyloidogenic proteins,66–67, 193, 196 these assumptions can break down and result in anomalous SDS-PAGE migration (Figure 3).

Sedimentation Velocity/Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation velocity centrifugation (SV) is one of the major applications of analytical ultracentrifugation, with several attractive properties as a hydrodynamic method orthogonal to the techniques mentioned above.197 In SV experiments, assemblies are fractionated at high centrifugal force based on differences in their mass, density and shape.198 In contrast to FCS, SV experiments require no extrinsic tag, and unlike SDS-PAGE, can proceed under native conditions. In contrast to SEC, fractionation occurs free in solution, in the absence of a solid phase, and with minimal surface interactions and negligible sample dilution.199 Monitoring peptide concentrations by absorbance throughout the experiment allows for the monitoring of possible sample adsorption. As large particles sediment before small particles, the method is also resistant to large particles such as unresolved protein aggregates or dust particles that plague DLS and FCS. Additionally, reversibly formed complexes are always in a bath of their components. SV has therefore been used to discern pentamers/hexamers as the smallest detectable Aβ42 oligomers formed in solution,200–201 and that putative toxic oligomers coexisting with amyloid fibrils of human islet amyloid polypeptide must contain more than 100 monomers.202 SV is particularly powerful in combination with other tools such as NMR,203 cryoEM,204 SANS,200 and with MD simulations.200

Single-Molecule Methods

Atomic Force Microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) provides nanoscale morphological information about a sample deposited on an atomically flat surface by monitoring the vertical deflection of a raster-scanned cantilever tip with sub-angstrom precision.205–206 In contrast to the above techniques, size and shape are directly interrogated one at a time. Generally, the vertical resolution can be considered to be on the order of 0.1 nm, while the lateral resolution ranges from 1 to 10 nm.206 Broadly, AFM can be used to distinguish oligomeric species from protofibrils and fibrils by their respective morphologies.206–207

Analyzing morphological properties at different time points allows for the possibility of obtaining information on mechanisms and pathways of aggregation/self-assembly. Ruggeri et al.207 used high-resolution AFM imaging to monitor early stages of α-synuclein oligomerization with single monomer resolution. The authors identify for the first time a single-stranded elongated species they term protofibrils, which, based on height and cross-sectional area, was deduced to have formed directly from unfolded monomers. These protofilaments assembled into double-stranded and higher-order assemblies, leading to the formation of mature amyloid fibrils. Directly observing assembly events is hampered by the relatively slow imaging speed of high-resolution AFM, prompting the development of high-speed AFM (HS-AFM). AFM performed in solution and with acquisition times on the order of 102 milliseconds (vs > 30 s for conventional AFM) allowed for the structural assembly of α-synuclein208 and Aβ209 oligomers to be observed, albeit with lower resolution.

A potential challenge is that AFM measurements must be made at either a substrate-air or substrate-liquid interface. In both cases, an underlying assumption is that the assemblies formed in solution resemble those formed at interfaces, or deposit onto the substrate in fractions resembling those found in the bulk solvent. Recent studies indicate that assembly kinetics and morphologies at interfaces can differ from that in the bulk.210–215 Variations in physicochemical surface properties (e.g., hydrophobicity, charge, surface chemistry, roughness, crystal structure) can influence the conformation and mobility of adsorbed monomers, and thus promote or inhibit certain forms of assembly.215 Commonly used AFM surfaces such as mica and highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) have contrasting surface properties. Mica is highly negatively charged and hydrophilic in aqueous solution, while HOPG is hydrophobic. Reaction of mica with aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) places amines at the surface, leading to an overall positive charge.216 Comparing results on different surfaces can be used to check for surface-mediated effects. Like self-assembly and reorganization of the sample at the surface, differential adsorption of species can bias populations in heterogeneous solutions.193, 214, 217 Methods such as microfluidic spray deposition217 and carefully chosen spin-coating procedures214 have been developed to combat these potential artifacts.

Single-Molecule Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Single-molecule fluorescence (SMF) avoids ensemble averaging by observing single molecules (or in the case of protein aggregates, single oligomers) either diffusing through a confocal detection volume or immobilized on the surface of a coverslip for total-internal reflection (TIR) based SMF. When biomolecules of interest are labelled with two dyes (a donor and acceptor), Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) can be monitored between them to provide information on nanometer-scale intramolecular distances and dynamics. If the donor and acceptor dyes are placed on separate biomolecules, intermolecular distances and dynamics can be observed, so long as their distances are within the useful range for FRET (2–10 nm). The simultaneous acquisition of multiple experimental observables for each single molecule preserves correlations in these observables and provides additional tools to resolve subpopulations of pathogenic oligomers.218 Table 2 provides an overview of single-molecule and quasi-single-molecule (FCS and diluted FRET) fluorescence measurements on protein oligomers and aggregates. Depending on how monomers are labelled, these measurements can provide varied readouts of assembly products and their biophysical properties.

Table 2:

Single-molecule and quasi-single-molecule (FCS and diluted FRET) measurements on oligomers and aggregates. Measurements can be broadly classified as either single-color or multi-color; focused on either intermolecular or intramolecular measures of oligomer compactness; focused on relative or absolute differences in oligomer compactness; and focused on intramolecular dynamics, intermolecular dynamics, or the kinetics of oligomer assembly/disassembly. FRET primarily interrogates the interactions between a single donor-acceptor pair and no exact analytical expressions exist for general distributions of multiple donor and acceptors. As a result, measurements with multiple FRET pairs per oligomer focus on relative compactness. A single FRET pair per oligomer allows for more facile absolute distance inferences. However, for large oligomers, a single donor and acceptor may be at distances outside of the useful range for FRET (>10 nm), preventing structural characterization.

| Measurement | Labels Per Monomer | Average Number of FRET pairs Per oligomer | Physical Observables | Examples/References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCS | 1 | n/a |

|

47, 190–192 |

| FRET | 2 | ~1 |

|

232–233 |

| TCCD/FRET | 1 | >>1 |

|

220–221, 227–228 |

| Diluted-FRET | 1 | ~1 |

|

237 |

To this end, Klenerman and coworkers have used a combination of two-color coincidence detection (TCCD) and single-molecule FRET (smFRET) measurements to characterize soluble oligomers of α-synuclein,219–225 Aβ,226–227 the SH3 domain of PI3 kinase,228 tau,229 and Ure2.230 In these experiments, equimolar mixtures of monomers labelled with either a donor dye (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594) or an acceptor dye (e.g., Alexa Fluor 647) were incubated under varying conditions to form fibrils. Aliquots were taken at a series of time points and diluted rapidly to concentrations (ca. 20–100 pM), which ensured that only a single monomer or oligomer was present in the confocal detection volume at a time. Monomers, in which only a donor or acceptor fluorophore was present, could be distinguished from oligomers where fluorescence was detected from both fluorophores (i.e., two-color coincidence); allowing the relative quantification of monomeric and oligomeric species (Figure 5). The apparent size of oligomers could also be inferred from their fluorescence intensity (the number of fluorophores is proportional to the number of monomers) and their residence time in the detection volume (larger oligomers diffuse slower). Differences in the proximity of the donor and acceptor fluorophores within oligomers give rise to different FRET signals, from which differences in oligomer structure could be inferred.

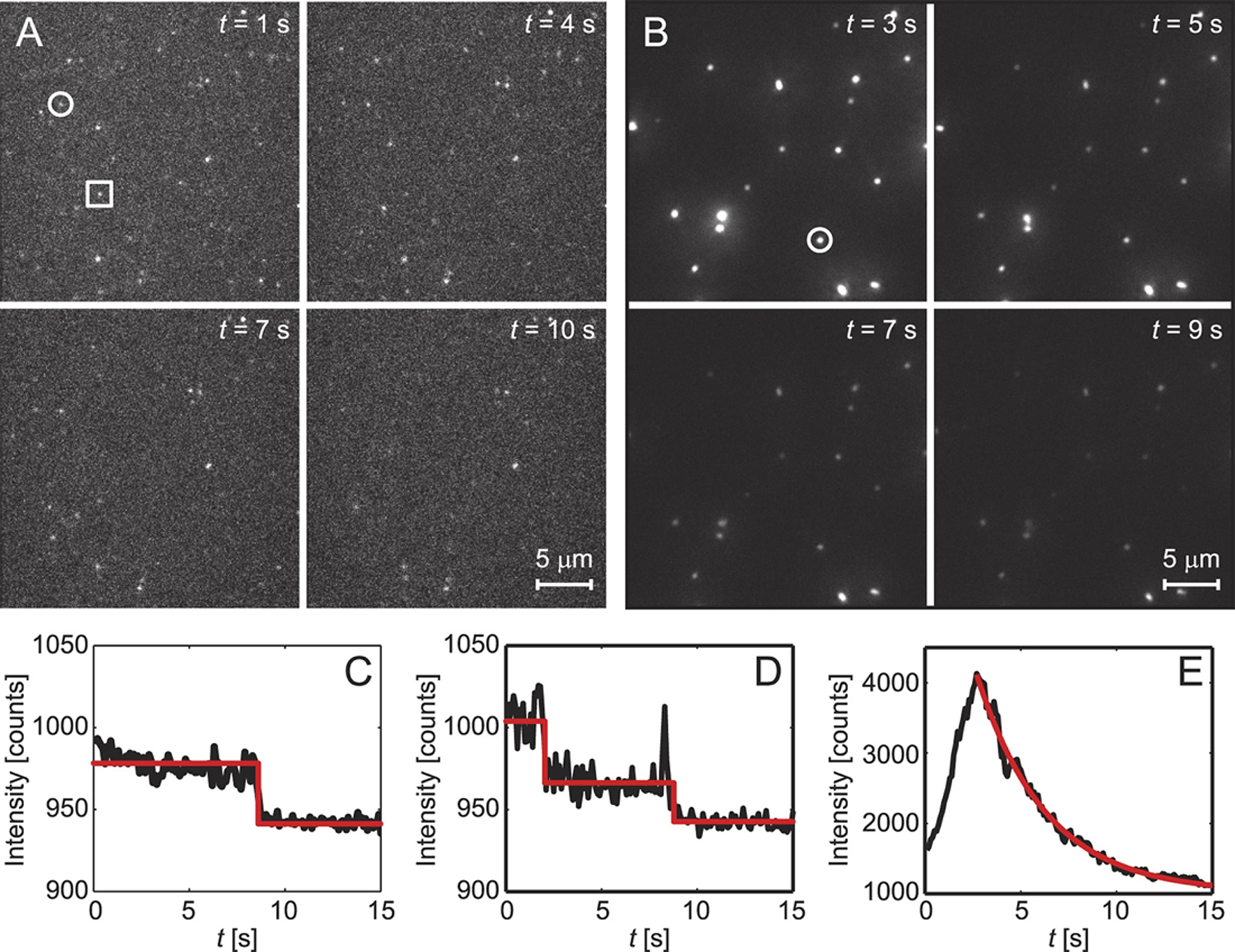

Figure 5.

Fluorescence microscopy data for Aβ42 monomers and oligomers (tagged with Alexa 647) over four timepoints on (A) glass or (B) lipid (POPC) surfaces. Single (C) and double (D) photobleaching events correspond to Aβ monomers (circle in A) and dimers (square in A), while exponential fluorescence decays (E) correspond to Aβ oligomers, which form preferentially on lipid surfaces. Reprinted with permission from Drews et al.317 Copyright 2016 Springer Nature.

This technique was used to structurally characterize α-synuclein oligomers, along with their kinetics and cytotoxicities.219 This was extended to compare wild-type α-synuclein with pathological missense mutations,220 the stability of oligomer sub-species in different ionic strength buffers,221 the dependence of α-synuclein aggregation kinetics on incubation concentration,223 the interaction of oligomers with extracellular chaperones225 or therapeutic nanobodies,224 and to determine whether purified oligomeric structures for cryo-electron microscopy are of similar compactness and overall quaternary structure as one of the species of oligomers revealed in their previous smFRET/TCCD experiments.222 From these studies, Klenerman and coworkers have identified an initially formed species of oligomer (type-A oligomers), which are characterized by low FRET efficiency values (low compactness), high sensitivities to proteinase K degradation, low stability in low ionic strength buffers, and low or no toxicity (e.g., rate of production of cytosolic ROS in neuronal primary cultures). These oligomers underwent slow conversions to a more compact oligomer (type-B oligomers), which displayed higher FRET efficiencies, higher resistance to proteolysis, higher stability to changes in solution conditions, the presence of a β-sheet core, and importantly, higher cytotoxicities.

Similarly, the technique has been applied to characterize soluble Aβ oligomers. De et al.227 combined TCCD/smFRET with gradient ultracentrifugation to characterize the structure of soluble aggregates, revealing that they mediate cellular toxicity through distinct mechanisms. Soluble aggregates aliquoted from different stages of the aggregation process were found to induce either disruption of membrane bilayers or an inflammatory response to different extents. Smaller aggregates, as separated by ultracentrifugation, showed lower FRET efficiencies (indicating that their labelled N-termini were further apart) and were effectively inhibited by antibodies that bound the C-terminal region of Aβ. These oligomers were found to be more potent at inducing membrane permeability. In contrast, larger oligomers showed higher FRET efficiencies and were more effectively inhibited by antibodies which targeted the N-terminal region of Aβ. These oligomers more effectively caused an inflammatory response in microglia cells. Narayan et al.226 used TCCD to characterize the species and stability of Aβ in the presence and absence of the extracellular chaperone clusterin, which is present in cerebrospinal fluid and is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. The authors confirmed that oligomeric species of Aβ could form at concentrations (30 nM) similar to physiological concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid,231 but at which fibril formation is very slow. Oligomers, although they represented only approximately 1% of the species present in this experiment, could be readily distinguished from monomers. Clusterin was found to strongly bind and sequester oligomeric species, inhibiting further growth or dissociation of these oligomers. Clusterin-Aβ complexes were stable at pM concentrations for over 200 hours, suggesting that toxic species could be sequestered until they are processed and degraded. This provides a molecular basis for previously observed associations between clusterin and Alzheimer’s disease.

In work from the Schuler lab, Hillger et al.232 used a large number of experimental observables (e.g., FRET, fluorescence lifetime, fluorescence anisotropy, etc.,) simultaneously acquired using multiparameter single-molecule fluorescence detection to separate and characterize subpopulations in the aggregation of the protein rhodanese. Rhodanese aggregation was initiated by either rapid dilution from denaturants or generated from folded proteins at high temperatures. While the FRET efficiency of the re-folded population did not depend on the mechanism of aggregate formation, the FRET efficiency of the aggregate population did, indicating differences in the conformations of monomers within the aggregate. A possible explanation for these discrepancies is differences in folding/unfolding intermediates. These differences in aggregate structure would usually remain undetected in ensemble methods, highlighting the power of this method to characterize heterogenous aggregation mechanisms.

In work from the same lab, smFRET was used to observe transiently misfolded conformations in immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains.233 These domains form deposits or inclusions with amyloid-like characteristics. These misfolded conformations have been proposed to act as seeds for the aggregation of Ig-like repeat domains. Importantly, these transient misfolding events are unsynchronized, and could thus not be directly observed in ensemble measurements.

While not explicitly associated with neurodegeneration, the Chung lab has used two- and three-color smFRET with multiparameter fluorescence detection to characterize the structure and kinetics of oligomers of the tetramerization domain (TD) of the tumor suppressor protein p53.234 Ensemble methods failed to characterize the oligomeric species because the dissociation constants of the dimer and tetramer are very close. An advantage of three-color FRET experiments is the determination of inter- and intramolecular distances simultaneously, preserving correlations. The different timescales with which FRET efficiencies and fluorescence lifetimes average over conformational dynamics allowed the authors determine the degree of conformational flexibility in the dimer and tetramer states. These experiments showed that the structure of the monomer is similar to the dimeric and tetrameric states, but contains more C-terminus flexibility compared to the dimer, in line with NMR results on a destabilized mutant dimer and molecular dynamics simulations.

In work from the same group, single molecule spectroscopy was used to characterize the heterogeneity of Aβ oligomers.235 The authors observed very weak interactions between Aβ monomers, and FRET efficiencies of dimers were found to vary widely, indicating that dimeric structures were heterogeneous. Based on their observations, the authors proposed a new model of heterogenous oligomerization and aggregation involving kinetic backtracking.236

The Miranker and Rhoades labs have recently introduced a method they term “diluted-FRET”, which they used to distinguish the structure/dynamics of toxic (membrane permeating) from non-toxic islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) oligomers.237 While these observations do not directly inform neuropathological aggregates, the similarities between IAPP and Aβ suggest that similar techniques can be used to expediently differentiate neurodegenerative oligomers. In particular, IAPP oligomers were prepared with a high ratio of unlabeled-to-donor or unlabeled-to-acceptor peptides (e.g., donor:acceptor:unlabeled, 1:1:500). Because of the high proportion of unlabeled peptides, oligomers with fewer monomers than the dilution ratio (e.g., 500) were unlikely to have both a donor and acceptor present. This focuses the data collection on large oligomers. For intermolecular dynamics that are slow relative to the integration time of measurement (here, 0.5 s/pixel), a broad distribution of FRET efficiencies is expected. This was observed for canonical IAPP fibrils, in which constituent peptides were not expected to be mobile. In contrast, rapid averaging of intermolecular distances resulted in narrow FRET peaks, as was observed for IAPP oligomers.

The method was applied to biologically relevant membrane systems, namely, giant plasma membrane vesicles (GPMVs) and depolarized mitochondrial membranes in live cells. Given the high proportions of unlabeled proteins, the fact that a FRET signal is observed is already indicative of internal dynamics. By following the time-evolution of the FRET distribution the authors monitored changes in oligomer structure (number, position, and area of FRET peaks) and dynamics (breadth of FRET peaks) to test mechanisms of oligomer growth. FRET histograms in the presence and absence of a small inhibitor of IAPP-induced cellular toxicity revealed that the small-molecule could constrain the protein in a specific conformation. This conformation inhibited the ability of oligomeric IAPP to form large pores on the membrane, revealing a mechanism by which toxicity is inhibited.

The most notable limitation of SMF approaches is the presence of the two extrinsic fluorescent dyes, which are relatively large compared to the average volume of an amino acid, contain rigid ring systems, and which are often charged (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594 have an overall charge of −2e, while Alexa Fluor 647 has an overall charge of −3e). In principle, the dyes can interact with one another or with the protein itself, altering the conformations of the monomer, the structure/dynamics of the aggregate, or the pathways and kinetics of assembly. As such, rigorous characterization of the effects of labeling, labeling positions, and fluorophores is necessary. Measurements with a variety of different donor and acceptor pairs should be performed to ensure consistency.221, 237 Aggregation kinetics and morphologies for labeled and unlabeled samples should also be compared to ensure consistency.219, 221, 238 Ensemble measurements such as intrinsic fluorescence239–240 or the use of BODIPY dyes241 have also been used to characterize amyloid fibrils and oligomers, however reduced quantum yields and extinction coefficients render these observations largely incompatible with single-molecule experiments. Finally, multiparameter fluorescence detection is valuable for differentiating real differences in distances and dynamics from apparent differences caused by the complex photophysics of fluorophores.167, 234, 242

THE PATHOLOGICAL AGGRESOME EX VIVO

Differences Between In Vitro and In Vivo Environments

While the ultimate goal of many aggresomal simulations and in vitro experiments is to better understand human disease, the discrepancies between these systems and patient-derived observations remain significant.243–244 A comprehensive review by Owen et al.244 highlights many of these differences in a wide variety of amyloid proteins, which aggregate readily in crowded environments that are difficult to recapitulate in a test tube. Cellular interiors, for example, contain up to 300 mg/mL of macromolecular complexes,245 making up nearly 40% of their volumes. These conditions favor compact structures, and can shift the equilibrium of monomers into dimers and other low molecular-weight oligomers if the resulting complex is more compact than the initial state.246 Studies have attempted to recreate these conditions in-vitro using dextran or Ficoll, which significantly speeds up aggregation,247 however the increase in steric repulsion alone does not account for the profound differences between in vitro and ex vivo experimental results.248–249 In order to resolve these discrepancies and adequately link benchtop aggregation experiments to real human diseases, comparisons must be made between lab-derived and patient-derived protein aggregates. Similarly, various (and often interacting) environmental factors must also be considered in the broad context of protein aggregation.

In the case of Alzheimer’s Disease, patient-derived protein plaques almost entirely consist of Aβ proteins, although another major hallmark is the presence of tau neurofibrillary tangles.250 While it is not clear if Aβ or tau aggresomes co-opt one another,251–252 mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and its associated enzymes (γ- and β-secretase) appear to dramatically increase the risk of AD,17, 19, 21 suggesting that Aβ-associated pathways are integral to regulating neurodegeneration. Interestingly, mutations to apolipoproteins (e.g. ApoE), which are the primary transporters of brain cholesterol, can also substantially enhance the risk of developing AD.253–254 However, given the reported associations between cholesterol and enhanced Aβ aggregation,255–256 it is perhaps not surprising that changes to fat transport over the life course can modulate neuropathological aggresomes.

Differential mutations to membrane-bound APP, which is cleaved to form cytosolic Aβ, can also result in a wide variety of aggresomal phenotypes, including enhanced fibrilization, highly cytotoxic oligomers, and heterogeneous amyloid fibrils.257 Despite the variety of phenotypes, the most cytotoxic aggregates appear to be soluble protein oligomers that sometimes precede fibrilization.42, 51, 56, 61, 66, 258–259 A plausible explanation might be that endogenous stabilizers (e.g., lipids or metals) shift oligomers into water-soluble or ‘off-pathway’ states, where fibrilization cannot occur. Lipids can also degrade inert fibrils back into pathological oligomers,43 but not back into monomers, suggesting that aggresomal proteins at least pass through a critical and perhaps irreversible threshold, resulting in macromolecular complexes that are difficult to degrade in vivo.

Other environmental factors that have been reported to affect the endogenous aggresome include the presence of metals260–261 and molecular detergents.262–264 In particular, transition metal ions such as iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu) have been reported to significantly modulate AD severity,260, 265 which form the basis of the AD metals hypothesis.266 While an excellent review of these interactions can be found in Maynard et al,261 recent observations suggest that metals upregulate reactive oxygen species (ROS), which indirectly affects protein aggregation through lipid peroxidation.267–268 Nonetheless, metals such as Fe, Zn, and Cu are routinely found in high micromolar concentrations in the interior of amyloid plaques,269 and have been shown to stabilize cytotoxic Aβ oligomers.48 In post-mortem brain samples, however, AD brain Cu levels were lower than controls, while Zn appeared in normal amounts.270 Thus, it is not clear how dominant the metals hypothesis is in modulating the aggresome in-vivo, or if such observations are confounded by the high prevalence of metals in the extra-cellular matrix (ECM). With regards to detergents and lipids, recent evidence suggests that soluble amyloid oligomers may convert to transmembrane pores on the surface of vesicles and liposomes.40 It’s unclear, however, if homogeneous protein oligomers induce membrane poration directly versus heterogenous lipoproteins that sequester lipids, leading to membrane permeability. Moreover, the ability of lipids to solubilize and stabilize pathological aggregates44 is likely a key regulator in human disease, and age-related changes to lipid membranes (peroxidation, cholesterol-induced changes in fluidity, etc.) could drive changes to protein aggregation in older individuals.271 Conversely, Aβ oligomers themselves do not appear to modulate membrane fluidity.272 Cholesterol transport, as mentioned earlier, has also been suggested as an age-related link to enhanced protein aggregation due to its role in maintaining liquid-ordered membranes,273 however cholesterol could also inhibit protein-lipid binding.274 Recent evidence suggests that cholesterol is capable of catalyzing Aβ42 primary nucleation by a factor of 20 through non-canonical pathways,275 significantly bolstering the hypothesis that lipids are a primary driver of in vivo Aβ aggregation.

Tissue-Specific Dyes and Techniques

Multiple techniques have also been used to successfully study aggresomes in patient-derived tissues, including fluorescence microscopy276 and NMR,70, 277 which have revealed a wealth of information about endogenous oligomers and fibrils. These techniques are often distinct from in vitro experiments and utilize unique fluorescent dyes or sample preparation protocols to evaluate post-mortem tissues. For example, Thioflavin S (ThS) and Congo Red stains have been utilized for over 50 years to identify amyloid deposits in tissue,278 however they are poor quantitative indicators of fibrilization due to their high background fluorescence.279 Congo Red has also fallen into disuse because it is highly carcinogenic,280 though a number of safer derivatives have been developed such as methoxy-XO4281–282 and BD-oligo283, which are capable of staining amyloid plaques and oligomers in live cells and tissue. Genetic tags such as GFPs are also heavily utilized for visualizing ex vivo aggregates, however drawbacks remain regarding their photophysical properties.284 For spectroscopic analysis of patient-derived tissue, Robert Tycko has used solid-state NMR to show that Aβ40 fibrils can be seeded from patient-derived amyloid seeds,70 where a number of polymorphic fibrils form and exhibit striking differences compared to in vitro fibrils. Many of these structures contain 3-fold symmetric subunits around a hollow-core, which was subsequently correlated with disease severity. Taken together, these tools and observations highlight the need for structure-specific protocols to image and extract ex vivo aggresomes that are distinct from those generated by standard biophysical assays.

Early Observations in the AD Brain

Despite the use of widespread fluorescent markers or antibodies in identifying endogenous aggresomal proteins, there are a number of important variables in the tissue extraction and purification process that must be carefully considered if direct comparisons are to be made with in vitro aggregates. For example, Tabaton et al.285 studied the presence of soluble Aβ monomers in AD and healthy brain parenchyma, and compared their concentrations to those found in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). While they found that CSF in diseased and healthy individuals both contain water-soluble Aβ monomers (perhaps suggesting that CSF actively sequesters brain Aβ), only AD brains contained large amounts of fractionated monomers. Despite these early observations, the extraction protocols of patient-derived aggresomal proteins from frozen samples is mostly unchanged today, and involves tissue homogenization (in a pH 7 buffer containing protease-inhibitors to preserve protein structure), ultracentrifugation, extraction of supernatants for soluble species and pellets for insoluble aggregates, immunoprecipitation, and final analysis using gel electrophoresis (western, dot blot, SDS-PAGE, or Native-PAGE).285–286 In the case of Aβ, antibodies reveal a heterogeneous mixture of truncated, isomerized, and racemized monomers in AD and Down’s syndrome brains.286 However, the extraction of Aβ from tissue involves the addition of 0.1% SDS to soluble fractions and 10% SDS to insoluble fractions, which effectively equals or far exceeds the amount of SDS (0.2%) required to nucleate the aggregation of pathological Aβ oligomers in vitro.44 As a result, the tissue extraction process itself may shift the relative populations of aggresomal monomers, oligomers, and fibrils. This is further complicated by SDS-PAGE, as described earlier, where denaturing amounts of SDS are added and boiled, questioning how lipid-aggregated oligomers degrade during tissue homogenization.

Early analysis of patient-derived brain samples also reported a number of Aβ dimers bound to neighboring proteins such as ApoE,287 however there are a number of confounding variables to consider. In particular, ApoE strongly binds lipoproteins containing cholesterol and/or triglycerides and is therefore flanked by fatty acids. As a result, Aβ-ApoE complexes likely contain a sizeable amount of lipid that nucleates pathological oligomerization.44 The presence of lipids can also degrade intact Aβ fibrils into smaller soluble oligomers,43 however as highlighted earlier, fat-containing oligomers can erroneously appear as dimers in SDS-PAGE and in size-exclusion chromatography,43 in stark contrast to electron micrographs that reveal large macromolecular assemblies. This is likely the case when dimers are observed to bind ApoE,287 indicating that pathological oligomers may have evaded early analyses of diseased brain parenchyma. These observations also bolster the association between pathological ApoE mutations288 (e.g. ApoE4289) and enhanced risk factors for AD,290 which may indirectly be linked to the presence of oligomer-solubilizing lipids.291 More contemporary work has shown that soluble Aβ seeds, but not monomers, extracted from human AD brains can cause pathological plaques and defects in APP-transgenic mice in as little as pico- or atto-molar concentrations.292 Such observations highlight the fact that pathogenic Aβ seeds are likely larger than monomers or dimers and are incredibly cytotoxic, with long-lasting pathological consequences.

Brain-Derived Aβ Extraction Protocols

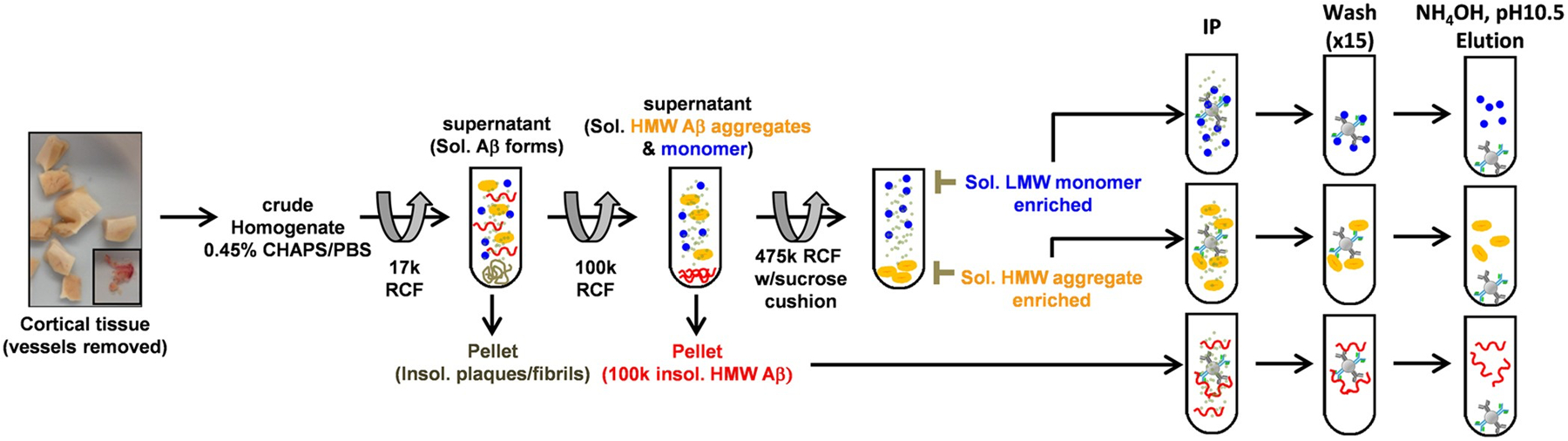

In an effort to systematically improve the extraction protocols of soluble aggregates in patient-derived tissues, the Brody lab published an outstanding study that addresses a multitude of prior deficiencies.293 Multiple improvements are suggested, such as the substitution of the detergent CHAPS for SDS, which reduces artificial protein aggregation ex vivo. Other changes include the use of differential ultracentrifugation with sucrose buffers to make a flotation assay that yields >6000 fold purification of soluble Aβ oligomers through dual immunoprecipitation (Figure 6). The authors also make a number of other pertinent observations, including that over 90% of soluble extracts may be lost on tube surfaces and in standard centrifugal filters. They suggest coating the interior of each tube with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), which dramatically reduces sample loss on surfaces and does not affect size-exclusion data of soluble Aβ. However, the introduction of a large protein, such as albumin, may also complicate the Aβ oligomerization process, and care should be taken. The authors also tested the ability of Tween-20 and other surfactant-containing substances to nucleate aggregation ex vivo, in order to minimize perturbations to soluble aggregates during the extraction process.

Figure 6.

An improved technique for isolating and purifying soluble aβ aggregates from human AD brain segments. Most notable is the substitution of CHAPS for SDS (which may nucleate protein oligomerization) and the use of a flotation assay (addition of a sucrose cushion) during ultracentrifugation. Reprinted with permission from Esparza et al.293 Copyright 2016 Springer Nature.

Heterogeneous Amyloid Extracts

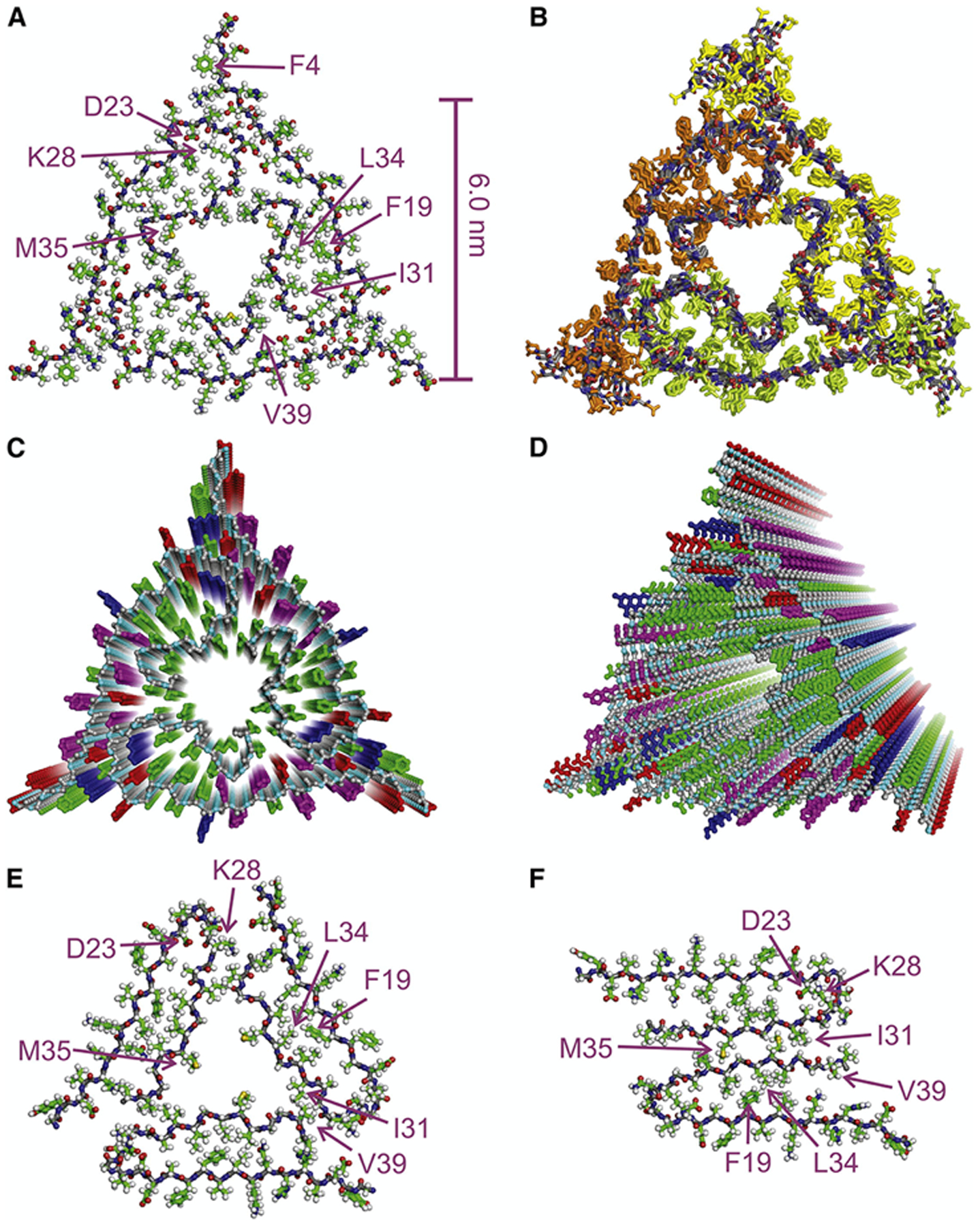

These techniques have been used to purify amyloid fibrils for structural determination purposes, which utilize the pelleted homogenates instead of the supernatants described above. As previously described, Robert Tycko employed solid-state NMR and electron microscopy to show a number of distinct Aβ40 fibrils that substantially differed from published in vitro fibrils (Figure 7).70 However, given that they find multiple C-terminal amino acids in interior-facing positions, Tycko suggests that certain antibodies may not bind to Aβ40 fibrils as efficiently as Aβ42 fibrils, thereby underrepresenting the pathogenic contributions of Aβ40. This is consistent with the roughly five-fold increase in Aβ40 levels in vivo compared to Aβ42. Cryo-EM structures from formaldehyde-fixed brain meninges also reveal highly polymorphic Aβ40 (and smaller) fibrillar structures that differ from in vitro data,71 many of which exhibit right-handed twists. Interestingly, collagenases and other enzymes can be safely used in protocols to extract patient-derived fibrils because the fibrils resist enzymatic degradation.71 These broad polymorphisms observed in endogenous fibrils suggest a rich thermodynamic ensemble that aggresomal proteins populate,76 perhaps highlighting that amyloid proteins interconvert between multiple pathological conformations.43 Similarly, other neurological fibrils containing α-synuclein243 or tau294 have also been characterized ex vivo, and show considerable differences from their in vitro counterparts. These observations further motivate the need to bridge in silico models with in vitro biophysical tools and ex vivo patient extracts.

Figure 7.

Solid-State NMR structures of ex vivo Aβ40 fibrils (A-D) reveal key differences from in vitro fibrils (F). These include a hollow triangular core with three-fold symmetry (E) compared to two-fold symmetric fibrils observed in vitro (F). Reprinted with permission from Lu et al.70 Copyright 2013 Cell Press.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STANDARDIZING STUDIES OF PATHOLOGICAL PROTEIN OLIGOMERS

We propose the following as a guide to design future studies in order to better standardize the data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of pathological protein oligomers across experiments.

First, the preparation protocol used to obtain synthetic assemblies is a key element in obtaining reproducible results. Thus, we only recommend comparing oligomers with the same preparation protocols and molecular constituents.

Second, oligomers should always be biophysically characterized after their synthesis or extraction using multiple independent techniques that can distinguish one oligomer from another, even if following an existing protocol. For example, in conflicting reports regarding cellular prion protein (PrP)-mediated ABo neurotoxicity, Laurén et al.,295 Kessels et al.,296 and Balducci et al.297 all refer to their preparations as ADDLs (amyloid-derived diffusible ligands), despite prominent differences in the application of the original ADDL protocol.298–299 Moreover, the limited characterization of these preparations prevents their direct comparison. The final preparations contained monomer, oligomer, and protofibril species, and likely also contain PrP-dependent, -independent, and benign subspecies in unspecified abundances. Such details can easily confound in vivo observations of neurotoxicity. Cognizant of these inconsistencies, many contemporary studies rigorously control preparation conditions300 to yield highly homogenous and reproducible assemblies. Moreover, they routinely characterize the resulting products using a wide variety of quantitative and complementary techniques.301–303

Third, additional tools for better distinguishing oligomeric forms of proteins from one another should be developed and/or routinely employed. We envision single-molecule fluorescence techniques as being especially useful in this regard due to its high sensitivity to small conformational/structural differences and the absence of ensemble-averaging. Furthermore, single-molecule techniques can simultaneously monitor internal oligomer dynamics and oligomer assembly kinetics, offering additional axes upon which to resolve sub-populations through.

Fourth, using these tools, environmental variables that produce distinguishable assemblies should be identified and controlled for to ensure reproducibility within individual preparations. For example, are ADDLs produced through incubation in F12 with304 or without302 L-glutamine distinguishable? Are globulomers prepared with fatty acids distinguishable from those prepared using non-physiological mimics (e.g. SDS)?44

Fifth, other single-molecule tools such as molecular simulations should be increasingly used to validate or inform observations from disparate biophysical experiments. Simulations are meaningful in so far as they reflect the assemblies under study and adequately consider the environmental variables identified as determinants. This is only possible with well-defined assemblies whose molecular context is known. While simulations have long been successful at deriving oligomers ab-initio, they are often not controlled for in a way that allows oligomers to be compared to one another, or to other stable complexes such as fibrils or liquid phase-separated condensates. Meaningful simulations of oligomers should include null hypotheses (where oligomers will not form), positive controls (fibrils versus oligomers), and sufficient buffers to modulate one type of oligomer from another. These considerations will greatly enhance the formation and interpretation of hypotheses regarding the mechanisms of oligomer toxicity.

Sixth, a multivariate “signature” of toxicity can then be attributed to a well-defined entry in a library of assemblies. In vitro, one might ask if an assembly binds to specific receptors or non-specifically to membrane surfaces? In vivo, one might consider if the binding of oligomers to neurons depends on the presence of a specific receptor, or if membrane permeabilization occurs? As a result, oligomers could be considered neurotoxic (e.g. affecting neuritic integrity) or synaptotoxic (e.g. inhibiting long term potentiation), but should not be considered broadly cytotoxic. This point is similar to the structure:function relationship in protein folding. While IDPs do not adopt stable secondary structures, their resulting oligomers may, in fact, exhibit distinct structure:function relationships that are important for understanding human diseases over the life course.

Patient-derived assemblies are exceptionally precious, and the pool of oligomers generated in vivo or derived ex vivo is likely more complex than any synthetic preparation. These two facts suggest that it is reasonable, if not essential, to begin collecting data on a library of “synthetic calibrants” followed by deducing their biological relevance. The structural and dynamic signatures of protein oligomers, and the toxicities of in vivo or ex vivo assemblies should be compared to these synthetic calibrants whenever possible. Synthetic assemblies that most closely resemble in vivo and ex vivo assemblies can then be consistently prepared and utilized as a pathological mimetic. Tools for maximally distinguishing various assemblies can also aid in the identification of excipients and processes that inadvertently modify ex vivo assemblies during their isolation.

CONCLUSIONS

In this summary we have reviewed a number of major complicating factors that must be taken into account when establishing links between molecular models of disease, biophysical characterization of in vitro amyloid oligomers, and patient-derived observations of disease. Significant discrepancies remain between common molecular models of the aggresome and the phenomena they seek to describe. Similarly, in vitro characterization of oligomers is highly variable, owing to variance in oligomer preparation protocols and the conditions under which characterization takes place. Finally, both data from aggresomal models and in vitro studies fail to fully recapitulate patient-derived observations. In vitro biophysical tools, however, offer the potential to bridge molecular models of protein aggregates with patient-derived observations in order to better understand the molecular determinants of neurodegeneration and perhaps intervene.

Specifically, we have highlighted single-molecule fluorescence and smFRET as powerful tools for overcoming the challenges of low abundance and heterogeneities in oligomer structure and dynamics. Traditionally, the complexity of the milieu in smFRET measurements on protein monomers is increased in incremental amounts, for example by adding denaturants,305 osmolytes,306 polyphosphates,307 heparin,308 SDS,309 and crowding agents.310 This bottom-up approach, when applied to oligomers, could lead to a milieu that increasingly resemble conditions in vivo. Alternatively, smFRET measurements in vivo311–313, although not commonplace, are expected to become powerful tools to reveal structure-toxicity relationships, as suggested already by the (ensemble) diluted-FRET approach.237

Establishing the pathological roles of soluble oligomers and their contributions to human disease requires standardization across disparate disciplines. By improving comparisons between oligomers studied in silico, in vitro, or ex vivo, we will be better enabled to make correlations between computational/experimental observables and mechanisms which mediate disease (neurological or otherwise). Identifying molecular mechanisms of disease-relevant oligomers, in turn, allows for the possibility of interfering therapeutically with these mechanisms, which could help alleviate the causes of neurodegeneration, or even slow down the aging process by neutralizing senescence-inducing oligomers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Z.A.L. is supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AG068285 and K01AG062752. Z.A.L. is also a Pepper Scholar with support from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at the Yale School of Medicine (P30AG021342).

Biographies

Dr. Gregory-Neal Gomes received a B.Eng. in Engineering Physics from McMaster University (Canada) and his PhD in Physics from the University of Toronto (Canada) under the supervision of Claudiu Gradinaru. After his PhD, Greg joined the Levine lab at Yale University where he currently works as a postdoc studying protein aggregation diseases from a biophysical perspective. His research interests are single-molecule fluorescence (SMF) techniques, integrative structural biology, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Prof. Zachary A. Levine is an assistant professor of Pathology at the Yale School of Medicine and of Molecular Biophysics & Biochemistry (MB&B) at Yale University. He received a BS in physics from San Francisco State University followed by an MS in Computer Science and a PhD in physics from the University of Southern California. He subsequently conducted postdoctoral research at the University of California Santa Barbara in the Departments of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Physics, and Materials. Following this, he became an associate research scientist at Yale University in the Department of Pathology, which preceded his appointment as an assistant professor in Pathology and MB&B. Established in 2019, his lab seeks to integrate molecular models of soluble amyloid-β oligomers with single-molecule fluorescence measurements of lab-derived and patient-derived aggregates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper G; Hausman R, The cell: a molecular approach. Sinauer Associates. Sunderland, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips R; Kondev J; Theriot J; Garcia H, Physical biology of the cell. Garland Science: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toyama BH; Hetzer MW, Protein homeostasis: live long, won’t prosper. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013, 14 (1), 55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babu MM; van der Lee R; de Groot NS; Gsponer J, Intrinsically disordered proteins: regulation and disease. Current opinion in structural biology 2011, 21 (3), 432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uversky VN; Oldfield CJ; Dunker AK, Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: introducing the D2 concept. Annu. Rev. Biophys 2008, 37, 215–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhoef LG; Lindsten K; Masucci MG; Dantuma NP, Aggregate formation inhibits proteasomal degradation of polyglutamine proteins. Human molecular genetics 2002, 11 (22), 2689–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]