Abstract

Aim

To better understand how oncology nurses (a) navigate graduate studies; (b) perceive the impact of their academic work on their clinical practice, and vice versa; and (c) engage with clinical settings following graduate work.

Design

Interpretive descriptive cross‐sectional survey.

Methods

A qualitative exploratory web‐based survey exploring integration of graduate studies and clinical nursing practice.

Results

About 87 participants from seven countries responded. 71% were employed in clinical settings, 53% were enrolled in/graduated from Master's programs; 47% were enrolled in/graduated from doctoral programs. Participants had diverse motivations for pursuing graduate studies and improving clinical care. Participants reported graduate preparation increased their ability to provide quality care and conduct research. Lack of time and institutional structures were challenges to integrating clinical work and academic pursuits.

Conclusions

Given the many constraints and numerous benefits of nurses engaging in graduate work, structures and strategies to support hybrid roles should be explored.

Keywords: cross‐sectional studies, employment, leadership, oncology nursing, surveys and questionnaires

1. INTRODUCTION

Historically, a gap between theory and practice has existed in the nursing profession, while, at the same time, academic institutions have actively sought to recruit nurses from practice into academic roles (Nardi & Gyurko, 2013). For nurses completing graduate education through Master's or Doctoral programs, the employment options are often situated in either a clinical or academic context, with few roles available that bridge both environments (Gibson, 2019). This often creates challenges for nurses striving to integrate clinical and academic work during and after graduate studies.

As members of the Doctoral and Post‐doctoral Network of the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology (Galica et al., 2018), we sought to better understand the experiences of oncology nurses navigating the dualities of clinical and academic worlds. We present findings from a survey of how oncology nurses navigate clinical and academic worlds. We explored how nurses decided to embark on graduate studies and how they navigated the tensions of these two worlds during and after completing their academic programmes. We offer recommendations for retaining nurses who have an interest in roles that connect these two worlds, and highlight the need for formal pathways with strong links between academic and health system environments.

1.1. Background

Graduate education is a key to the professionalization of nursing (Kim, 2009; Oldnall, 1995). Historically, nurses were trained in hospitals and steeped in clinical work. When training moved to educational institutions, the level of education increased but it also created a disconnect between clinical practice and academic work in the discipline (Nelson & Gordon, 2004). Much discussion has ensued regarding the distance between clinical and academic worlds in nursing, often labelled as the “theory‐practice” gap (Larsen et al., 2002; Rolfe, 1998). The divergence between these two worlds has been problematized by those who feel there should be a seamless connection between theory and practice, highlighting the absence of purposeful structures to enable such a reality (Hickerson et al., 2016; Huston et al., 2018).

The theory‐practice gap is often discussed in the context of new nurses entering practice (Clipper & Cherry, 2015; Duchscher, 2009) and experiencing “transition shock” (Duchscher, 2009; Duchscher & Windey, 2018). However, less has been written about the experiences of registered nurses completing graduate studies (Cathro, 2011). When discussed, graduate preparation of nurses is typically framed in the context of faculty shortages (McDermid et al., 2012; Nardi & Gyurko, 2013), and the need to encourage more nurses to become nurse educators, which further entrenches the notion that one must “leave the bedside” to engage in academic work (Hunter & Hayter, 2019). Furthermore, several authors have identified difficulties transitioning from clinician to academic, best described by Hunter and Hayter (2019) as the loss of one identity while searching for another.

Although nursing is a multifaceted discipline of practice, research, education and policy, evidence of the “theory‐practice gap” is further substantiated by inadequate integration of the core components of practice and research. Gibson (2019) illustrates disciplinary challenges related to integrating practice and research through comparison to other allied health professionals, demonstrating that there are fewer nurses than allied health professionals holding Integrated Clinical Academic Fellowships (salary support for clinicians with dual clinical/research roles) in the UK. Gibson urges the development of roles which blend clinical, research and teaching so that nurses can continually question and draw from their clinical practice to advance research and scholarship, and likewise from research and scholarship to advance clinical practice. However, the implementation of these roles poses challenges. In a qualitative study of PhD prepared nurses working in clinical settings, Orton et al. (2019) found that participants were responsible for implementing research in practice, yet experienced many barriers to working to the full scope of their ability, lacking structural conditions and support to integrate academic and clinical work. Therefore, despite the potential and actual value of nurses with research expertise and graduate preparation, greater understanding is needed of how they navigate clinical and academic settings, and the challenges and benefits they experience during and after their graduate work (Andreassen & Christensen, 2018; Hunter & Hayter, 2019).

With cancer as a leading cause of death and disability globally, specialized oncology practice has developed as a distinct and dominant sub‐specialty within the nursing profession (Haylock, 2008; Miaskowski, 1990). Oncology nurses require an understanding of the acute and long‐term management of cancer, alongside compassion and empathy to assist individuals and their families to navigate the complexities of their cancer journey (Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology, 2001). The expansion of contemporary oncology nursing is best demonstrated by the growth of the Oncology Nursing Society, an American Organization representing cancer nurses in a multitude of settings. Launched in 1975 with 226 members, as of 2008, it reported more than 35,000 members globally (Haylock, 2008). Similarly, in Canada, the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology was launched with 150 nurses in 1985; at the end of July 2020, membership numbered 1,050. With the growth of this specialty, oncology nurses have sought graduate education in increasing numbers worldwide.

1.2. Aims

Our aims were to better understand how oncology nurses (a) navigate graduate studies; (b) perceive the impact of their academic work on their clinical practice, and vice versa; and (c) engage with clinical settings following graduate work.

1.3. Design

Guided by an interpretive descriptive approach to inquiry (Thorne, 2016), we sought to gain insight from oncology nurses working in a wide range of practice settings and geographical regions through an investigator‐developed web‐based survey. Qualitative survey instruments are meant to be exploratory in nature, using primarily open‐ended questions (Braun et al., 2020; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010), and are useful in collecting detailed information (Dillman et al., 2014). This approach allowed us to collect qualitative data from a large and geographically dispersed sample, while employing naturalistic methods to analyse and interpret the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

1.4. Sample

Between September 2018 and June 2019, we invited registered nurses working in oncology who were completing, or had completed, graduate education to participate in an anonymous web‐based survey. We used convenience and snowball sampling methods. Nurses were invited to participate through social media and the email distribution lists of the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology and the European Oncology Nursing Society. We also disseminated the survey to oncology nursing colleagues and asked them to distribute to their peers and networks.

1.5. Data collection

We developed a web‐based survey hosted through SurveyMonkey®, using an institutional license. This 13‐question survey included six demographic questions and seven open‐ended content questions exploring the integration of graduate studies and clinical practice (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Survey questions

| Sociodemographic questions |

|

| Content questions |

|

1.6. Data analysis

We followed the interpretive descriptive approach described by Thorne (2016), wherein an analytic framework is iteratively constructed, moving through phases of comprehending the data, synthesizing their meaning, theorizing relationships and then recontextualizing the data (Morse, 1994; Thorne et al., 2004). Specifically, we used thematic analysis methods to analyse open‐text data using a collaborative, team‐based approach. We used Microsoft Excel and NVivo 12 software to organize and manage data and integrate analyses. We prioritized the content and meaning of themes over the structure, number and content of particular codes, aiming to understand the experiences and perspectives of participants while exploring similarities and differences across survey responses (Thorne, 2020).

During the initial phase of analysis, all team members read open‐ended responses from the same group of 10 participants to develop a preliminary coding framework and discuss emerging themes. We continued this process, reading and coding survey responses line‐by‐line and discussing preliminary themes across groups of ten participants, until all of the responses from 30 participants had been coded. We met multiple times to review early coding with alternate team members leading discussion about codes generated and the developing themes.

One team member organized the coding framework in Microsoft Excel using the initial codes and themes. This framework was collaboratively discussed, revised and agreed upon by all team members. We then imported the entire data set and coding framework into NVivo, divided the data set equally among team members and coded all participant data with the agreed‐upon coding scheme. In the final step of analysis, we summarized the study results and implications to reach consensus among all team members. We analysed sociodemographic data using descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel.

1.7. Rigour

To ensure trustworthiness and credibility of the findings, we applied strategies of epistemological integrity, representative credibility, analytic logic and interpretive authority (Thorne, 2016; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Approach to rigour (based on description by Thorne, 2016)

2. FINDINGS

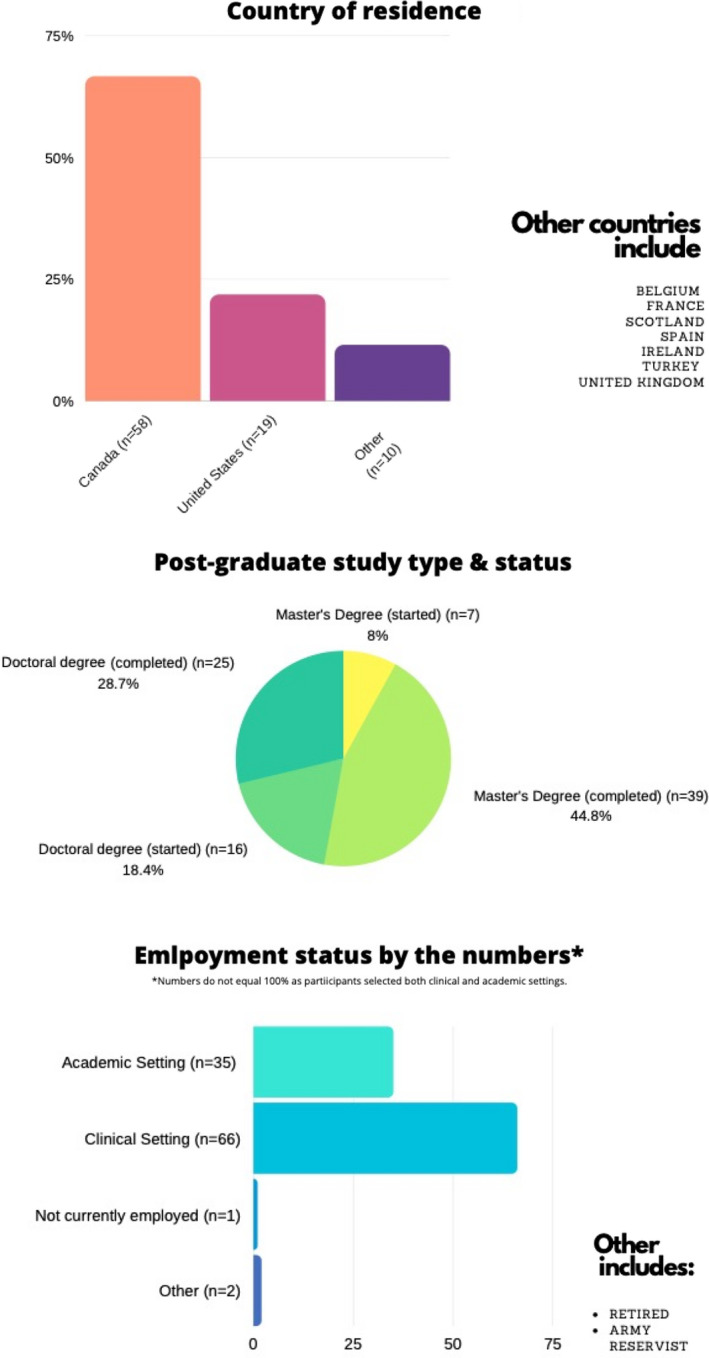

2.1. Description of participants

A total of 87 participants from seven countries responded to the survey (Figure 2). The majority of participants were identified as female (N = 84, 97%) and were employed in clinical settings (N = 62). Most respondents had graduated from a Master's program (N = 39, 45%) or doctoral program (N = 25, 29%); the remainder were enrolled in a Master's (N = 7, 8%) or doctoral programs (N = 16, 18%).

FIGURE 2.

Participant characteristics

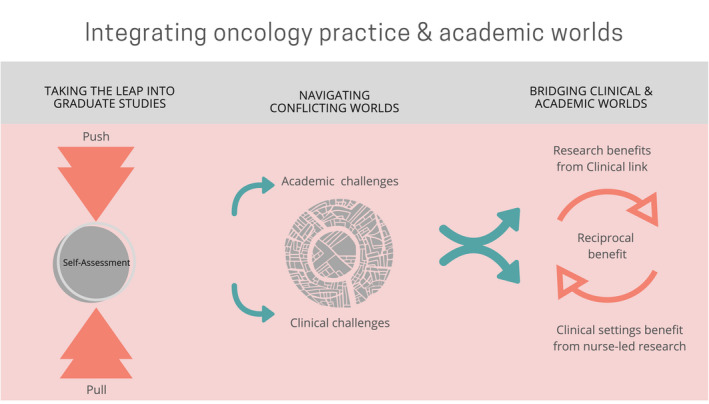

2.2. Overarching themes

Through analysis of open‐text survey data, we explored how participants integrated clinical and academic work, which we summarized with three themes: (a) taking the leap into graduate studies, (b) navigating conflicting worlds, and (c) bridging clinical and academic worlds (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Themes

2.2.1. Taking the leap

Participants described the reasons they chose to enter graduate studies, often listing a number of cumulative factors leading them to pursue graduate education. They expressed this choice as a jump, a dramatic change or a distinct decision point, which carried with it an element of risk and uncertainty. They expressed concern about leaving the safety and security of clinical practice and moving into another world. We categorized the personal and contextual elements that led participants to pursue graduate education in terms of push factors, pull factors and participants’ process of self‐assessment.

Push factors

Push factors refer to aspects of participants’ workplaces or clinical roles that motivated them to return to graduate studies. The factors pushing participants towards graduate studies included frustrations with system‐related care issues; lack of challenge or responsibility; an inability to affect change, provide the desired level of care or work to full scope of practice within an RN role; and a lack of time, funding and support to engage in research. One participant stated: “It did not seem like I could get traction as a front‐line staff nurse.” Another shared, “I felt like my RN designation was holding me back to provide the type of holistic care and autonomous care I would like to be providing to patients.” These push factors prompted participants to step away from clinical practice with the aim of acquiring the skill set and credibility to more fully realize their clinical potential.

Push factors also included participants’ expressed desire to pursue graduate studies to increase their skills and abilities to address clinical concerns. As one participant described, “While I am caring for my cancer patients, I think that my skills were not enough to support them psychosocially. So, I finished my master[s] and now I am nearly finished my PhD.” Other participants felt that education was a means to more effectively solve problems observed in clinical practice: “I was motivated to complete a doctorate to conduct research that would promote equity and address some of the problems I observed in practice.” In this way, participants viewed graduate education as a way to gain the skills to create change within their work environments and provide quality clinical care.

Pull factors

We characterized pull factors as the aspects of graduate education and research that drew participants to pursue graduate studies. Participants spoke about a general sense of curiosity and ambition, while also highlighting a desire to step into specific roles, including advanced practice, nurse practitioner or principal investigator. They also considered how engagement in graduate studies might help develop nursing as a profession and promote the role of nurse‐led research: “I was working in clinical research and therefore was learning research skills and was identifying gaps that could be filled by nursing research.” In this way, pull factors often reflected the appeal of integrating clinical and academic worlds.

Participants also described experiences of “shoulder tapping” or being encouraged to pursue graduate studies by mentors and peers, as a pull to start graduate studies: “Changes in the work‐place got me thinking about it and a couple of colleagues and a friend in the program encouraged me.” The encouragement came from both clinical and academic mentors, including nursing or medical program directors. Participants also wrote about being pulled towards graduate studies by opportunities for funding or specific programs.

Self‐assessment

Prior to taking the leap, participants described a process of self‐assessment, which included considering one's personal skills, interests and life circumstances. Participants assessed themselves as having curiosity, a desire to learn or an interest in research, which fit their interest in graduate studies. As one participant wrote: “I felt I had the skills and interest to contribute to nursing in a broader way.” Timing in the context of personal life circumstances played an important role for some participants as they considered stage of life, family and other commitments. Participants commented on how children, or not having children or having older children, played an important role in deciding when to start graduate studies. As one participant simply stated: “Long time goal – waited until children [were in their] late teens to complete.” In this way, taking the leap into graduate studies was shaped by a combination of professional push and pull factors coupled with an alignment with personal characteristics and circumstances.

2.2.2. Navigating conflicting worlds

Study participants included those working in clinical or academic settings. Regardless of context, participants described challenges associated with negotiating tensions between clinical and academic worlds, including challenges for clinicians while completing graduate studies, and challenges for participants working in either clinical or academic roles following completion of a graduate degree.

Challenges for clinicians during graduate education

Many participants highlighted the challenges of completing a graduate degree when working in a clinical role. These included a lack of support from leadership, time pressures, and roadblocks that hindered their contributions to research. Participants often went to extensive personal lengths to pursue graduate work, as one participant wrote: “Working full time. Doing school work during mat leave. Night shifts. Shift work”. Thus, participants’ ability to engage in graduate studies incurred a personal cost, due to the scarcity of available institutional supports.

Challenges after studies: clinical roles

For clinicians navigating the academic and research worlds, there were numerous challenges that extended after graduation from graduate degrees. These challenges often centred on resource limitations, the most critical being limited designated time for research, with clinical work described as “all‐encompassing.” This was accompanied by lack of access to supports to enable engagement in research, including library access, research funding and grant management staff. As one participant wrote, “Due to cost constraints, my clinical colleagues have lost access to the university library and librarians… This has huge impact on ease of access to rigorous literature and expert knowledge brokers.” These were cited as critical resource limitations that made it more difficult for clinically based nurses to participate in research.

Participants working as clinicians noted that when they made the extra effort to engage in research, there was little recognition from peers, managerial staff and other health professionals. They described a lack of respect for the distinct value of nursing research and lack of understanding about advanced practice nursing roles. One participant described that her challenge was, “to gain respect from health care colleagues about the importance of oncology nursing research”. Another noted that she encountered a, “lack of understanding by health care professionals, including some staff nurses, of the role of the clinical nurse specialist.” Due to this lack of support, participants confronted delays and barriers when trying to implement practice changes and educational initiatives.

As a result of the lack of resources and support, participants described an overall sense of disconnect from the academic world. As one participant noted: “I felt removed from academic progress and [it was] hard to keep updated about recent advancements, clinical colleagues [were] not appreciating the importance of research and it's advancement of clinical care.” Thus, participants situated in clinical settings illustrated an important paradox: gaining enhanced knowledge and skills in their academic studies to strengthen clinical practice, then encountering barriers when bringing this knowledge into their clinical setting. These experiences contributed to participants’ frustration, when the desire to improve care was what drew them to pursue graduate studies.

This was also likely connected to the feeling expressed among participants that, when researchers asked them to contribute to research projects, their potential contributions were underutilized. For instance, graduate prepared nurses were often asked to collect data and help with recruitment, without being involved in study design, data analysis, or interpretation. They felt limited in their ability to contribute to the growth of disciplinary knowledge. One participant concisely summarized the challenges of post‐graduate clinical practice: “There needs to be a better partnership for postgraduate nurses where we are not only working in a clinical setting but also teaching or engaging in academic work…We need to learn from our physician colleagues. It is time to advance nursing once again.”

Challenges after studies: academic roles

Similar to their clinical‐based counterparts, participants working in research also experienced gaps between clinical and academic worlds, particularly when attempting to maintain clinical work or engage in clinical research. A PhD‐prepared participant shared the challenges of stepping away from their clinical role: “As a clinician, I found it very difficult to step back from patient contact to complete my PhD. I missed the contact horribly! So, I created ways to make contact in the community by volunteering.” The desire and ability to maintain clinical practice can be difficult due to an absence of appropriate positions and devaluing of clinical work within academic systems of advancement and funding. Participants often identified a dissonance in the requirements of each: “The demands of clinical work are often at odds with the demands of academia‐ you cannot attend every meeting or quickly answer every email while working clinically.” Researchers trying to maintain clinical practice also described a feeling of having to explain their practice as a PhD‐prepared nurse to other nurses and health professionals, to get buy‐in from clinical colleagues. Without such support and buy‐in, it was very difficult to enact change.

Participants working in research roles experienced challenges developing research collaborations and gaining access to clinical sites, due to a lack of support from leadership, difficulty gaining access to time‐constrained staff, or lack of interest in research. A participant wrote, “the focus is direct patient care, and our clinical nurses don't have time away from the bedside to… [conduct]research or even use the bathroom.” Participants working in research also noted challenges associated with the lack of support and priority placed on research within clinical nursing. As a result, it became difficult for researchers to find clinical collaborators, at times resulting in “the demise of an otherwise great study,” poignantly highlighting the gap between clinical and research worlds.

Productivity requirements within academic funding and promotion systems often penalized those involved in clinical practice or research: “Ethic[s] review board delays, delays related to clinical practice changes and study roll out conflicts, recruitment delays based on lack of clinical prioritization of research all impact timelines, grant fund access and productivity requirements.” In the same way that clinicians desired dedicated time for research, researchers desired time and support to do the additional work of engaging with clinical settings: “We need academics to be able to have enough protected time to do research and to build strong relationships to clinical sites.”

The lack of research roles within clinical contexts was widely acknowledged and often required researchers to either relinquish their interest in these roles or be creative and forceful to remain engaged in both academic and clinical areas: “I primarily hold an academic position, but my areas of research are primarily clinically‐focused, and I am seconded part‐time to a tertiary centre to mentor/support/lead clinical research, including at present oncology‐related studies.” Thus, navigating these conflicting worlds and attempting to bring them together was challenging for those desiring both research and clinical roles.

2.2.3. Bridging clinical and academic worlds

Despite many challenges, participants articulated important benefits of bridging clinical and academic worlds; benefits were multi‐faceted and outweighed the challenges. Whereas challenges often referred to system factors, the benefits were broad and far‐reaching in scope. Benefits related to the impact of academic work on clinical practice; the impact of engagement in clinical practice on academic research; and the reciprocal benefit when clinical and academic worlds align.

Impact of academic on clinical practice

Participants articulated how the benefits of completing graduate studies enhanced their capacity as an oncology nurse in clinical practice. Benefits were related to nurses’ potential to shape and improve the health system, improve patient care and patient outcomes, and to improve and grow knowledge in the discipline. As one respondent described: “I am more aware of the big picture and the limitations that exist within a large, provincial organization. I have a greater appreciation for research and the impact it may have on current practices. I am also more aware of why evidence‐based practice changes can be such a long and arduous process.” This understanding shaped participants’ own practice and the ways they were able to educate and shape the practice of others.

Participants also described their ability to have a greater impact on patients and grow as professionals through new skills, enhanced confidence and greater knowledge. As one respondent stated: “I have become more independent with my learning, not relying on medical experts to provide me with answers.” Participants also described the potential for moving forward and identifying opportunities for integrating research and clinical practice: “I think academia re‐excites me about my nursing practice and reminds me why I love direct patient care.”

Bringing the academic world into practice presented many benefits for participants, including an enhanced focus on reflexivity around unquestioned practices and approaches to clinical care. Integrating an inquisitive approach to clinical practice was illustrated by having an understanding of how to use research to solve problems: “When a potential research question arises, I find it incredibly helpful to know how to go about answering the question. Having research experience has been invaluable to me.” Finally, participants felt that uniting academic and clinical worlds inspired passion for patient care and greater interest in research to enhance patient care.

Impact of clinical on academic research

Those with a research or academic appointment described numerous benefits to integrating clinical worlds into their work and felt that research informed by practice was more clinically relevant. Participants also felt that maintaining links to clinical practice ensured that research was appropriately and feasibly designed and rigorously conducted in a manner reflective of clinical realities. One participant wrote, “my clinical work through my studies added richness and another dimension of understanding to my academic work.”

Finally, maintaining links to clinical practice was thought to enhance future dissemination and uptake of research findings in clinical practice. One respondent summarized these benefits: “[clinical] partnerships ensure that the right questions are pursued, that the best most feasible study designs are developed, that findings are interpreted appropriately, and that the dissemination of findings is both local and broad, and clinically relevant, with a quicker uptake at study completion as key stakeholders are part of the team. It is a win‐win and great fun too.”

Reciprocity of interaction between academic and clinical

Participants wrote about the important interdependent relationship between academic and clinical worlds as central to nursing practice: “I think this is the crux of nursing science. We are responsible for identifying problems from our clinical expertise and using science to address them.” Participants described the impact of clinical on academic work, and of academic work on clinical as reciprocal and cyclical, describing that “both inexorably impact each other.” Ultimately, participants viewed this collaboration as essential for healthcare improvement: “There needs to be stronger connections between academia and practice to improve the health care system, we must work in collaboration more effectively.” In this way, participants described the integration and bridging of these worlds as both the privilege and responsibility of engaging in graduate studies.

3. DISCUSSION

In this paper, we describe the complex tensions navigated by oncology nurses as they traverse clinical and academic worlds when entering and journeying through graduate studies. Participants contemplated both push and pull factors as they started graduate studies and weighed personal and life circumstances in making their decision about the “right time” to start graduate education. Participants faced numerous challenges during and after completing their graduate degrees, regardless of whether they remained in clinical roles or stepped into academic roles. Ultimately, each person's interest in negotiating these challenges was driven by their vision of the specific and global benefits associated with bridging clinical and academic worlds. Our findings add new insight into the literature on registered nurses’ experiences in navigating academic and professional roles related to graduate education.

Clinicians with graduate training described the challenge of incorporating new knowledge into their clinical roles, specifically related to research. Prior research has described master's prepared nurses as those who deliver, rather than lead, research (Kim, 2009). In this study, the absence of supports for graduate‐prepared clinically located nurses to engage in research was a barrier. For those in academic roles, establishing clinical connections was equally challenging. Participants identified an absence of formal structures to support their contribution to clinical practice and collaboration with clinical partners. Time was cited as a major contributor to this barrier; however, participants also described a systematic devaluing of the integration of clinical and academic roles and a lack of institutional support. Although other health professions have demonstrated that clinical and academic roles can be successfully integrated (Gibson, 2019), participants in this study indicated that they were forced to choose academic or clinical practice. This highlights an unfortunate and ironic loss for our profession: the integration of clinical and academic worlds is understood as the crux of nursing practice, yet numerous systemic barriers impede such integration.

The described incentives for nurses to enter graduate studies included the desire to level up, affect change and optimize their skills. Other researchers have described the self‐reported benefits of graduate education as including increased job satisfaction and career mobility (Pelletier et al., 1994), enhanced leadership capabilities and qualities (Clark et al., 2015), and a sense of empowerment (Graue et al., 2015). Participants felt unable to optimize their career in these ways within clinical roles without graduate training and thus left clinical positions to pursue further education. This presents an opportunity for collaboration between health and educational institutions, to create the infrastructure needed to better support nurses, with and without graduate education, to advance their careers and pursue leadership opportunities. For example, further opportunities need to be created for nurses to be involved in research and graduate training programs while maintaining their clinical roles, thereby maximizing and sustaining valuable nursing expertise. This is critical given the need for more, not less, nurses with graduate training, not only due to retirements in the academic sector, but to foster leadership, quality care and growth in the profession (Rishel, 2013). Further research is needed to identify strategies for supporting stronger links between academic and health system environments to advance embedded research within clinically based nursing roles and clinical practice within academically based nursing roles.

One important consideration and finding from this study was the prevalence of shoulder‐tapping. The notion that certain nurses may be identified as having leadership potential by individual leaders seems harmless, but may in fact reinforce inequities and have negative consequences for the accessibility of nursing education. Nursing has been described as overwhelmingly white, and ‘whiteness’ in nursing is a concept that has gained more awareness in professional discourse (Allen, 2006; Hall & Fields, 2013; Nielsen et al., 2014; Puzan, 2003). Efforts to create formal structures to support nurses from diverse backgrounds in pursuing graduate studies should be a priority for decision‐makers. Similar programs targeted at undergraduate and pre‐licensure students have shown success and could be used as exemplars for models in graduate education (Loftin et al., 2013; Melillo et al., 2013). This finding reiterates the need for structural, rather than individual, change within the profession, and the need to incorporate decolonizing approaches to broaden the spectrum of benefit in graduate nursing education (McGibbon et al., 2014).

3.1. Limitations

In this study, our focus was on oncology nurses with the understanding that their experiences reflect the shared experiences of nurses seeking graduate studies and navigating the clinical and academic worlds; however, we recognize that differences among specialties may exist. Therefore, this study offers insight into the experiences of graduate prepared oncology nurses and may or may not be generalizable to nurses in other specialties.

The nurses who responded to this study may be those most interested and engaged in integrating clinical practice and research, thus the perspectives of nurses who do not view this as an important aspect of nursing practice may be under‐represented; further research might explore alternate perspectives. This limitation requires additional consideration given that participants were contacted through international oncology nursing organizations and social media, and this may represent a selected group of clinician respondents. Future research may benefit from studying two groups of clinicians where one group is inclined towards integrating the clinical and research practice with those who are not.

While a web‐based survey limited the depth and richness of the data, this approach allowed us to draw from a large sample across varied practice settings and geographical regions. Analysing textual qualitative data also represents a potential challenge regarding the researchers’ interpretation, inability to clarify responses, and potentially loss of nuance around participants experiences. In future studies, other forms of qualitative data collection (e.g. interviews, focus groups) may garner broader and more detailed insights, with an opportunity to probe differences across perspectives.

4. CONCLUSION

In this study, oncology nurses described the factors that shaped their choice to engage in graduate studies and the importance of integrating clinical and academic worlds in nursing practice. Participants described the active work they had to do to bridge the gaps caused by a lack of collaboration between clinical and academic settings, which created important challenges in both nursing clinical practice and nursing research. The main factor informing participants’ decision to pursue graduate education was largely attributed to a desire to use academic skills and knowledge to improve clinical care and contribute to the profession. Thus, the forced choice between clinical and academic practice after graduation is strikingly problematic. Furthermore, our findings suggest that engaging clinical nurses in projects and roles that optimize their knowledge and skills may lead to greater job satisfaction, improve the ability of organizations to recruit and retain a highly skilled nursing workforce, promote quality care and strengthen the structure of nursing. Therefore, it is critical that clinical and academic leaders must actively work to create collaborations and links to bridge the divide between clinical and academic settings within the nursing discipline.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study conception: All authors; Data collection: All authors; Data analysis: All authors; Manuscript writing: All authors; Manuscript revisions: KH. All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria [recommended by the ICMJE (https://www.icmje.org/recommendations/)]: substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

We received ethics approval from the University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board (BEH 18‐320). All participants were required to read and agree to a statement of informed consent prior to completing survey. All responses were anonymous.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our gratitude to the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology and the European Oncology Nursing Society for their assistance with disseminating the survey. This study was supported by a recruitment and retention fund grant from the University of Saskatchewan (Haase).

Haase KR, Strohschein FJ, Horill TC, Lambert LK, Powell TL. A survey of nurses' experience integrating oncology clinical and academic worlds. Nurs Open. 2021;8:2840–2849. 10.1002/nop2.868

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available. Please contact the authors for any inquiries.

REFERENCES

- Allen, D. G. (2006). Whiteness and difference in nursing. Nursing Philosophy, 7(2), 65–78. 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2006.00255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, P., & Christensen, M. K. (2018). “We're at a watershed”: The positioning of PhD nurses in clinical practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(8), 1908–1918. 10.1111/jan.13581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Boulton, E., Davey, L., & McEvoy, C. (2020). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cathro, H. (2011). Pursuing graduate studies in nursing education: Driving and restraining forces. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 16(3), 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L., Casey, D., & Morris, S. (2015). The value of Master's degrees for registered nurses. British Journal of Nursing, 24(6), 328–334. 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.6.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clipper, B., & Cherry, B. (2015). From transition shock to competent practice: Developing preceptors to support new nurse transition. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 46(10), 448–454. 10.3928/00220124-20150918-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed‐mode surveys: The tailored design method. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Duchscher, J. E. B. (2009). Transition shock: The initial stage of role adaptation for newly graduated registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(5), 1103–1113. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchscher, J. B., & Windey, M. (2018). Stages of transition and transition shock. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 34(4), 228–232. 10.1097/NND.0000000000000461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galica, J., Bilodeau, K., Strohschein, F., Powell, T. L., Lambert, L. K., & Truant, T. L. (2018). Building and sustaining a postgraduate student network: The experience of oncology nurses in Canada. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 28(4), 288–293. 10.5737/23688076284288293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. (2019). Shouldn't we all be clinical academics? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(9), 1817–1818. 10.1111/jan.14026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graue, M., Rasmussen, B., Iversen, A. S., & Dunning, T. (2015). Learning transitions–a descriptive study of nurses’ experiences during advanced level nursing education. BMC Nursing, 14(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s12912-015-0080-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. M., & Fields, B. (2013). Continuing the conversation in nursing on race and racism. Nursing Outlook, 61(3), 164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haylock, P. J. (2008). Cancer nursing: Past, present, and future. Nursing Clinics of North America, 43(2), 179–203. 10.1016/j.cnur.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickerson, K. A., Taylor, L. A., & Terhaar, M. F. (2016). The preparation–practice gap: An integrative literature review. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 47(1), 17–23. 10.3928/00220124-20151230-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J., & Hayter, M. (2019). A neglected transition in nursing: The need to support the move from clinician to academic properly. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(9), 1820–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston, C., Phillips, B., Jeffries, P., Todero, C., Rich, J., Knecht, P., Sommer, S., & Lewis, M. (2018). The academic‐practice gap: Strategies for an enduring problem. Nursing Forum, 53(1), 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. J. (2009). Clinical academic research careers in nursing: Towards global nursing. Journal of Research in Nursing, 14(2), 125–132. 10.1177/1744987108101953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, K., Adamsen, L., Bjerregaard, L., & Madsen, J. K. (2002). There is no gap ‘per se’ between theory and practice: Research knowledge and clinical knowledge are developed in different contexts and follow their own logic. Nursing Outlook, 50(5), 204–212. 10.1067/mno.2002.127724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry (vol. 75). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Loftin, C., Newman, S. D., Gilden, G., Bond, M. L., & Dumas, B. P. (2013). Moving toward greater diversity: A review of interventions to increase diversity in nursing education. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 24(4), 387–396. 10.1177/1043659613481677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermid, F., Peters, K., Jackson, D., & Daly, J. (2012). Factors contributing to the shortage of nurse faculty: A review of the literature. Nurse Education Today, 32(5), 565–569. 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGibbon, E., Mulaudzi, F. M., Didham, P., Barton, S., & Sochan, A. (2014). Toward decolonizing nursing: The colonization of nursing and strategies for increasing the counter‐narrative. Nursing Inquiry, 21(3), 179–191. 10.1111/nin.12042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melillo, K. D., Jacqueline Dowling, P., Lisa Abdallah, P., & Mary Findeisen, P. (2013). Bring diversity to nursing: Recruitment, retention, and graduation of nursing students. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 20(2), 100. [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski, C. (1990). The future of oncology nursing. A historical perspective. The Nursing Clinics of North America, 25(2), 461–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J. M. (1994). Emerging from the data: The cognitive processes of analysis in qualitative inquiry. Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods, 346, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi, D. A., & Gyurko, C. C. (2013). The global nursing faculty shortage: Status and solutions for change. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 45(3), 317–326. 10.1111/jnu.12030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, S., & Gordon, S. (2004). The rhetoric of rupture: Nursing as a practice with a history? Nursing Outlook, 52(5), 255–261. 10.1016/j.outlook.2004.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, A. M., Alice Stuart, L., & Gorman, D. (2014). Confronting the cultural challenge of the whiteness of nursing: Aboriginal registered nurses’ perspectives. Contemporary Nurse, 48(2), 190–196. 10.1080/10376178.2014.11081940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldnall, A. S. (1995). Nursing as an emerging academic discipline. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 21(3), 605–612. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1995.tb02746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orton, M. L., Andersson, Å., Wallin, L., Forsman, H., & Eldh, A. C. (2019). Nursing management matters for registered nurses with a PhD working in clinical practice. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(5), 955–962. 10.1111/jonm.12750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, D., Duffield, C., Gallagher, R., Soars, L., Donoghue, J., & Adams, A. (1994). The effects of graduate nurse education on clinical practice and career paths: A pilot study. Nurse Education Today, 14(4), 314–321. 10.1016/0260-6917(94)90143-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzan, E. (2003). The unbearable whiteness of being (in nursing). Nursing Inquiry, 10(3), 193–200. 10.1046/j.1440-1800.2003.00180.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rishel, C. J. (2013). Succession planning in oncology nursing: A professional must‐have. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40(2), 114–115. 10.1188/13.ONF.114-115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe, G. (1998). The theory‐practice gap in nursing: From research‐based practice to practitioner‐based research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(3), 672–679. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2010). Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S. (2016). Interpretive description. Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S. (2020). Beyond theming: Making qualitative studies matter. Nursing Inquiry, 27(1), e12343. 10.1111/nin.12343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S., Reimer Kirkham, S., & O'Flynn‐Magee, K. (2004). The analytic challenge of interpretive description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available. Please contact the authors for any inquiries.