Abstract

Nickel (Ni) is carcinogenic to humans, and causes cancers of the lung, nasal cavity, and paranasal sinuses. The primary mechanisms of Ni-mediated carcinogenesis involve the epigenetic reprogramming of cells and the ability for Ni to mimic hypoxia. However, the exact mechanisms of carcinogenesis related to Ni are obscure. Nuclear protein 1 (NUPR1) is a stress-response gene overexpressed in cancers, and is capable of conferring chemotherapeutic resistance. Likewise, activator protein 1 (AP-1) is highly responsive to environmental signals, and has been associated with cancer development. In this study, NUPR1 was found to be rapidly and highly induced in human bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells exposed to Ni, and was overexpressed in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells. Similarly, AP-1 subunits, JUN and FOS, were induced in BEAS-2B cells following Ni exposure. Knockdown of JUN or FOS was found to significantly suppress NUPR1 induction following Ni exposure, demonstrating their importance in NUPR1 transactivation. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are known to induce AP-1, and Ni has been shown to produce ROS. Treatment of BEAS-2B cells with antioxidants was unable to prevent NUPR1 induction by Ni, suggesting that NUPR1 induction by Ni relies on mechanisms other than oxidative stress. To determine how NUPR1 is transcriptionally regulated following Ni exposure, the NUPR1 promoter was cloned and inserted into a luciferase gene reporter vector. Multiple JUN binding sites reside within the NUPR1 promoter, and upon deleting a JUN binding site in the upstream most region within the NUPR1 promoter using site-directed mutagenesis, NUPR1 promoter activity was significantly reduced. This suggests that AP-1 transcriptionally regulates NUPR1. Moreover, knockdown of NUPR1 significantly reduced colony formation and anchorage-independent growth in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells. Therefore, these results collectively demonstrate a novel mechanism of NUPR1 induction following Ni exposure, and provide a molecular basis by which NUPR1 may contribute to lung carcinogenesis.

Keywords: NUPR1, nuclear protein 1, P8, COM1, nickel, carcinogenesis, metals

Introduction

Nuclear protein 1 (NUPR1) is a multifunctional protein that primarily acts as a transcriptional regulator. It has also been shown to take part in cell cycle regulation (1), apoptosis (2), DNA damage response (3), and autophagy (4). NUPR1 is a highly sensitive stress-inducible gene that responds to a number of biological and chemical stressors including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (5), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (6), serum starvation (7), amino acid deprivation (8), carbon tetrachloride (9), and hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] (10). Moreover, NUPR1 is overexpressed in lung, breast, colorectal, pancreatic, and many other cancers, and plays a role in cell transformation, tumorigenesis, metastasis, and chemotherapeutic resistance (11). In lung cancer cell lines and lung tumor tissues of different histopathological subtype, NUPR1 expression was found to be elevated (4,12). Recently, NUPR1 was implicated in Cr(VI)-induced lung cell transformation, which raises the question of whether NUPR1 may also be involved in the carcinogenic process elicited by other cancer-causing metals (10).

Nickel (Ni) is a naturally occurring element present in rocks and sediment, and is released into the surrounding environment through forest fires, volcanic emissions, and erosion processes (13). Ni also occurs due to anthropogenic activity largely attributable to stainless and alloy steel, nonferrous alloy and superalloy, electroplating, catalyst and chemical production and use (14). The vast majority of Ni is used to produce stainless steel, followed by superalloys and nonferrous alloys, which are predominately used in the aerospace industry (14). Moreover, Ni is found in dietary sources, and to a lesser degree, in drinking water (15). Humans, therefore, may be both occupationally and environmentally exposed to Ni. Exposure to Ni occurs primarily via inhalation, and there are many health risks associated with exposure to Ni, the majority of which impact the respiratory system. Epidemiological evidence supporting a casual role of Ni in respiratory cancers dates back to 1949, and since then, has been well documented (13,15). Based on epidemiological, mechanistic, and in vivo studies, Ni compounds are carcinogenic to humans as classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (15). Exposure to Ni can also cause deleterious health effects other than cancer such as asthma, cardiovascular disease, dermatitis, and lung fibrosis (13). The mechanisms of Ni-mediated carcinogenesis, however, have yet to be fully elucidated.

The role that NUPR1 plays in Ni-induced carcinogenesis and the involvement of activator protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factor in these processes were investigated in this study. NUPR1 and AP-1 were both induced by Ni, and NUPR1 was determined to be upregulated in Ni-transformed human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells. Furthermore, knockdown of AP-1 suppressed NUPR1 induction by Ni. This suggests that AP-1 is a key factor for NUPR1 induction by Ni and in the stress-response directed by NUPR1. Since AP-1 is known to be induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS), the possibility that ROS contributes to NUPR1 induction following Ni exposure was investigated. ROS were determined not to be a primary mechanism by which AP-1 regulates NUPR1 induction following Ni exposure. Furthermore, NUPR1 transactivation was determined to be enhanced by AP-1 component, JUN. To conclude, stable knockdown of NUPR1 in Ni-transformed cells reduced cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth. In summary, NUPR1 induction via AP-1 in response to Ni represents a mechanism capable of conferring carcinogenic potential to human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to Ni.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and cell culture

Nickel chloride was purchased from Sigma Aldrich/Merck KGaA (catalog no. N6136). Antioxidant treatments were performed with (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) (Sigma Aldrich/Merck KGaA; catalog no. E4143), L-ascorbic acid (Asc; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; catalog no. A-61), and a-tocopherol/vitamin E (vit. E; Sigma Aldrich/Merck KGaA; catalog no. T3251). Hydrogen peroxide was purchased from Sigma Aldrich/Merck KGaA (catalog no. 216763). Immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) were obtained from ATCC (ATCC® CRL-9609), adapted to serum growth immediately after purchase, carefully maintained at below confluent density, and were authenticated by short tandem repeats (STR) analysis. Experiments were performed within approximately six passages (e.g. two weeks) from the time of thawing, and replicates were performed simultaneously. Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells were previously generated and characterized (16). In brief, BEAS-2B cells were exposed to soluble Ni for 30 days, after which transformed clonal populations were selected based upon anchorage-independent growth of single cells in soft agar accompanied by a corresponding footprint of cancer-related gene expression changes (16). The 293 cell line was obtained from ATCC (ATCC® CRL-1573) and authenticated by STR analysis. BEAS-2B, Ni-transformed BEAS-2B, and 293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; catalog no. 15140-122). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% carbon dioxide.

Cell transfection

Stable transfections in BEAS-2B cells were performed using Lipofectamine LTX reagent with PLUS reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; catalog no. 15338030). Control shRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; catalog no. sc-108060) and NUPR1 shRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; catalog no. sc-40792-SH) were used for stable knockdown. Transient transfections in BEAS-2B cells were performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; catalog no. 13778030). Control siRNA (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; catalog no. 12935112), siRNA against JUN (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and siRNA against FOS (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were used for transient knockdowns.

Cell lysate preparation and western blot analysis

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS 2X, lysed using RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitors; Roche Diagnostics; catalog no. 11 836 170 001) or boiling buffer (1% SDS, 4 mM Na3VO4, and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Cells lysed with RIPA buffer were collected and incubated at 4°C for 30 min with constant agitation. Lysates were then centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C, 20,000 × g, transferred, and frozen at −80°C until use. Cells lysed with boiling buffer were collected, denatured at 100°C for 5–10 min, sonicated for 10 min, centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min, transferred, and stored at −80°C until use. Protein was quantified using Pierce™ BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; catalog no. 23225) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Approximately 30–70 µg of total protein was separated on 10–18% SDS-PAGE gels by electrophoresis, and proteins were transferred to a 0.2 µM nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) for 2 h at 100 V or overnight at 20 V. Membranes were blocked for non-specific binding sites in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% non-fat dry milk at room temperature. The membranes were immunoblotted with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C (JUN, 1:400, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-1694; FOS, 1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., catalog no. 2250; β-tubulin, 1:20,000, Proteintech, catalog no. 66240-1-Ig; β-actin, 1:15,000, Proteintech catalog no. 66009-1-Ig; and NUPR1, 1:200, Sigma Aldrich/Merck KGaA, catalog no. SAB1104559). Membranes were then incubated with HRP- or AP-conjugated secondary antibodies (HRP, goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1:5,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., catalog no. 7074; HRP, goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:5,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-2005; AP, goat anti-rabbit, 1:5,000, Promega Corp., catalog no. S3731). Protein detection was performed using chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., catalog no. 32106) or chemifluorescence (Cytiva, catalog no. RPN5785) and developed using autoradiography or imaged using a Typhoon imager (GE Healthcare, model no. FLA 7000).

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Cells were collected in Tri reagent (Molecular Research Center, catalog no. RT 111), and either stored at −80°C or processed immediately for RNA isolation. The quantity and purity of RNA extracted from each sample were determined by UV absorbance spectroscopy on a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer system. Reverse transcription was performed using either LunaScript RT SuperMix (New England BioLabs, catalog no. E3010) or ProtoScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis (New England BioLabs, catalog no. E6300) with 500 ng of RNA in a final volume of 10 µl. Following denaturation of the first-strand cDNA product for 5 min, quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., catalog no. 4367659) on an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 6 Flex system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Relative gene expression levels were normalized to an endogenous control and calculated using the DDCq method (17). The following primers were used: NUPR1: 5′-CTGGCCCATTCCTACCTCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCTCTTGGTGCGACCTTTC-3′ (reverse); JUN: 5′-GAGCTGGAGCGCCTGATAAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCCTCCTGCTCATCTGTCAC-3′ (reverse); FOS: 5′-GAATCCGAAGGGAAAGGAATAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCCGCTTGGAGTGTATCAGTCA-3′ (reverse); ATF2: 5′-CATGGCCCACCAGCTAGAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTATTGCCTGGCAGAATTCACA-3′ (reverse); FOSL1: 5′-CCTTGTGAACGAATCAGCCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCGGTCAGTTCCTTCCTCC-3′ (reverse); TUBULIN: 5′-GCAAGGTATCCTAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTCGTCCTGGTTGGGAAACA-3′ (reverse); and ACTIN: 5′-TGACGTGGACATCCGCAAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGAGG-3′ (reverse), and GAPDH: 5′-TCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGCGTCAAAGGTGGAGGAGTG-3′ (reverse).

NUPR1 promoter cloning and NUPR1-luciferase vector construction

Two degenerate primers, 915NUPR1FD and 2394NUPR1RD (Table SI) were used initially to amplify BEAS-2B genomic DNA. A 1,480-base pair DNA fragment was restricted with BamHI (present in the primer sequences), and cloned into the BamHI site of pUC19 (pNUPR264). The presence of NUPR1 promoter fragment nucleotide 925 to nucleotide 2384 of NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) submission AF069074 was confirmed by sequencing. In order to include more NUPR1 promoter DNA sequences in this clone, the BamHI site was destroyed using Bal 31 on both ends to generate two separate clones (pNUPR287 for 3′ and pNUPR288 for 5′ deletion) (18). A 1.6-kb PCR product was amplified from BEAS-2B genomic DNA with primers 72NUPR1FD and 1724NUPR1NR, restricted with BamHI (present in 72NUPR1FD) and EcoNI (present in the 3′ end of the PCR product) and inserted into corresponding sites of pNUPR287. This new recombinant (pNUPR289) included an additional 842 base pairs of promoter sequences at the 5′ end of the initial clone (pNUPR264). Similarly, 1,125 base pairs of DNA were amplified with primers 2099NUPR1NF and 3223NUPR1NRD, restricted with EcoRV (present in the 5′ end of the PCR product) and BamHI (present in the primer 3223NUPR1NRD) and inserted into corresponding sites of pNUPR288. This new recombinant (pNUPR290) contained an additional 699 base pairs of promoter sequence at the 3′end.

For NUPR1-luciferase vector construction, a 2,054 base pair KpnI-EcoRV 5′ promoter fragment from pNUPR289 and 1,074-base pair EcoRV-HindIII 3′ fragment from pNUPR290 was inserted into a pGL4.17 vector (Promega Corp.) into their KpnI-HindIII sites to generate the full length NUPR1 promoter construct, pNUPR308 (Fig. S1A). The recombinant construct was sequenced in both directions and is identical to the published sequence, except for an additional 19 base pairs (CAAGTATCCTGTCTTCACT) after nucleotide 957 of GenBank submission of AF069074. To further investigate promoter activity in the cloned sequence using promoter bashing technique, the 5′ end of this sequence was deleted sequentially using Bal 31 as previously described (18). Six recombinants (NUPR309-314) with increasing amount of deletions at the 5′ end of the NUPR1 promoter were selected and sequenced to determine the extent of deletion (Table SII).

Luciferase gene reporter assay

Cells were stably transfected with pGL4-basic reporter vector containing the full length NUPR1 promoter or the NUPR1 promoter with deletions varying in length and position located upstream of the luciferase gene (Fig. S1A). Approximately 13,500 cells were seeded overnight into each well of a 48-well plate. After seeding, the medium was refreshed, and the cells were unexposed or exposed to Ni for 24 h. Luciferase reporter system (Promega Corp., catalog. no. E1500) was used to detect the luminescence intensity, and cell lysate preparation and luminescence measurements were conducted according to the manufacturer's protocol. All measurements were adjusted for total protein, normalized to pGL4 control, and performed in triplicate.

Site-directed mutagenesis assay

ALGGEN PROMO software V 3.0.2, a virtual laboratory for the identification of putative transcription factor binding sites in DNA sequences, was used to determine the transcription factor binding sites within the NUPR1 promoter region (19). Cells were stably transfected with a pGL4 vector containing the full length NUPR1 promoter (pNUPR308) or NUPR1 full length promoter with JUN transcription factor binding site deleted (−2339 to −2333) in the NUPR1 promoter positioned upstream of the luciferase gene (Fig. S1A). Deletions were made using the Q5® site-directed mutagenesis assay kit (New England BioLabs), and the resulting plasmid was sequenced (Genewiz, http://www.genewiz.com/) to confirm the deletion of the JUN binding site in question (Fig. S1B). The luciferase gene reporter assay was conducted as described herein. All luciferase measurements were adjusted for total protein, normalized to pGL4 vector control, and performed in triplicate.

Anchorage-independent growth assay

Anchorage-independent growth was determined by the ability of cells to grow in soft agar. A bottom layer of 0.5% 2-hydroxyethylagarose (Sigma Aldrich/Merck KGaA, catalog no. A4018), and top layer containing 5,000 cells in 0.35% 2-hydroxyethylagarose was place in a 6-well plate. After two weeks, the wells were stained with 500 µl INT/BCIP (Roche Diagnostics, catalog no. 11 681 460 001), and prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. Images of each stained well were acquired using a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager Gel-Doc XR+ system and Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Colony numbers were calculated using ImageJ (NIH, V 1.52q). When seeding cells in soft agar, 200 cells were simultaneously seeded into a 100-mm dish in order to determine the plating efficiency in monolayer culture, which is defined as the ratio of the number of colonies (those formed in a cell culture dish) vs. the number of cells seeded. After a 12-day incubation, the plates were fixed and stained overnight with 5% Giemsa in a 5:6 methanol:glycerol solution. After destaining, all cell colony numbers were counted using ImageJ (NIH) and plating efficiencies were determined. All soft-agar assays were adjusted for plating efficiency and performed in triplicate.

Colony formation assay

The cells were rinsed with PBS, briefly trypsinized, and neutralized with complete medium. Following neutralization, the cell suspension was then passed through a 40-µm cell strainer (Celltreat, catalog no. 229482) to eliminate cell clumps. Two hundred cells were then reseeded into each of three 100-mm dishes, and grown for 3 weeks. Surviving colonies were stained with Giemsa and counted using ImageJ (NIH, V 1.52q). All colony formation assays were conducted in triplicate.

Graphical depictions and statistical analyses

ImageJ (NIH) was used to quantify western blots, and to determine cell colony numbers. Western blot images were converted into 8-bit JPEG images, and the intensity of protein bands were normalized to the loading control. For colony formation assays, images were captured using a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager Gel-Doc XR+ system and Image Lab software (V 2.0.1., Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Images were converted into 8-bit JPEG images, and the background was reduced using a median filter to eliminate non-colonies. Graphical depictions and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Differences between groups were compared using either a Student's t-test or ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc multiple comparisons test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, as shown in the figures.

Results

Nickel is an inducer of NUPR1

Cr(VI), an IARC group I human lung carcinogen, induces NUPR1 mRNA and protein levels in human bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells (10). Ni is also a group I human lung carcinogen; however, the mechanisms of carcinogenesis between Cr(VI) and Ni differ in many respects. Cr(VI) is a classical carcinogen in the sense that it strongly binds DNA and proteins, creating protein and/or DNA adducts and subsequently, mutations; however, it also produces a high degree of oxidative stress through intracellular reduction to Cr(III) and acts carcinogenically through epigenetic mechanisms (20,21). Ni, on the other hand, is often thought of as a nonclassical carcinogen, and acts carcinogenically by mimicking hypoxia, which is common in tumors, as well as by dysregulating the epigenetic program of cells (13). Both Ni and Cr have been shown to induce AP-1, and multiple AP-1 sites reside in the promoter region of NUPR1 [reviewed in ref. (21)] (22–24). Therefore, the possibility of whether Ni is capable of inducing NUPR1 expression in BEAS-2B cells was investigated.

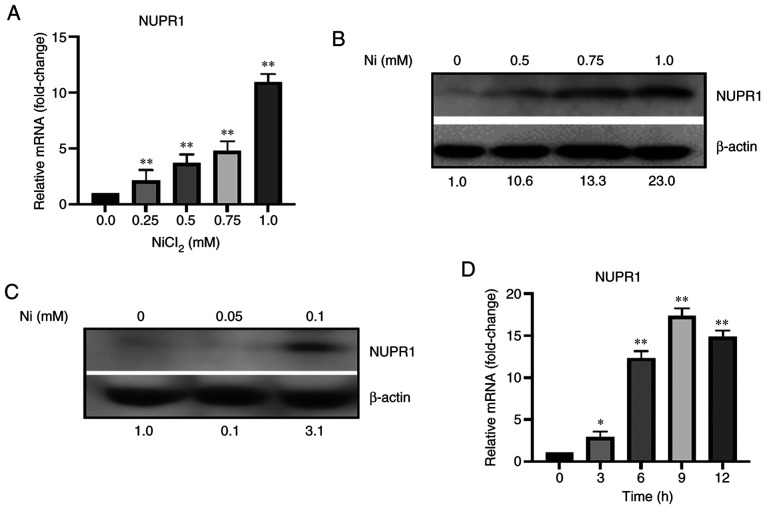

BEAS-2B cells were acutely exposed to 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0 mM Ni for 12 h, and the mRNA levels of NUPR1 were measured by real-time PCR and protein expression was determined by western blot analysis. The levels of NUPR1 mRNA were dose-dependently increased following exposure of BEAS-2B cells to Ni (Fig. 1A) as were the protein levels of NUPR1 (Fig. 1B). Dose-dependent induction of NUPR1 protein and mRNA was also evident in BEAS-2B cells after 6 h of Ni exposure (data not shown). BEAS-2B cells were then exposed to 0, 0.05, and 0.1 mM Ni to explore whether extended exposure to Ni can induce NUPR1 expression. As shown in Fig. 1C, extended exposure to 0.1 mM Ni was capable of inducing NUPR1 protein levels by 3.1-fold after 7 days. NUPR1 mRNA levels were unchanged, however (data not shown). In order to determine if Ni induces NUPR1 in a time-dependent manner, BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for various time points up to 12 h. After 3 h there was only a 2.9-fold increase in NUPR1 mRNA expression (Fig. 1D). Surprisingly, however, NUPR1 mRNA was highly induced at 9 h (17.3-fold), and decreased through 12 h, after having peaked at 9 h. There was no significant time-dependent difference in NUPR1 mRNA expression in unexposed BEAS-2B cells over 12 h (data not shown). Collectively, these results show that NUPR1 is induced at both the protein and mRNA levels following dose- and time-dependent exposure to Ni. Furthermore, this suggests that NUPR1 is quickly and transiently induced by Ni, which is characteristic of early stress-response genes (25).

Figure 1.

NUPR1 mRNA and protein expression is induced by nickel (Ni). (A) Acute Ni exposure induced NUPR1 mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner. Total RNA was extracted from BEAS-2B cells after 12 h of exposure to 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0 mM Ni. (B) Acute Ni exposure induced NUPR1 protein expression in a dose-dependent manner. BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 0, 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0 mM Ni for 12 h. (C) Extended Ni exposure induced NUPR1 protein expression. BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 0, 0.05, and 0.1 mM Ni for 7 days. (D) Acute Ni exposure induced NUPR1 mRNA in a time-dependent manner. Total RNA was extracted from BEAS-2B cells following exposure to 1.0 mM Ni after 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h. NUPR1 mRNA expression was assessed using RT-qPCR. Gene expression levels were normalized to actin, and are presented as fold change relative to the control group. NUPR1 protein expression was analyzed by western blot analysis using antibodies against NUPR1. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software, and are presented as fold change relative to the control group after normalizing for β-actin. All data shown are the mean ± SD from qPCRs performed in triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. NUPR1, nuclear protein 1.

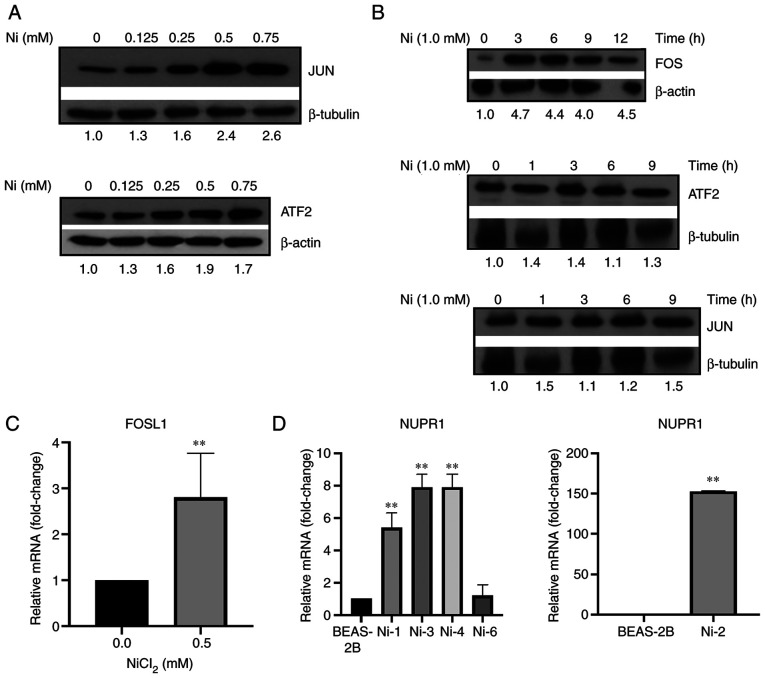

Nickel induces transcription factor AP-1

BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 mM Ni for 24 h, and the protein expression of AP-1 subunits, JUN, FOS, and ATF2, was investigated. Both JUN and ATF2 protein expression were found to be dose-dependently increased following Ni exposure (Fig. 2A). However, unlike JUN and ATF2, FOS protein expression was undetected after 24 h of exposure to Ni at increasing doses. Instead, FOS protein expression was found to be quickly and transiently induced by 1.0 mM Ni after only 1 h, and its expression proceeded to increase until approximately 6 h when its expression then started to decrease (Fig. 2B). This was not determined to be the case for both JUN and ATF2, as their protein expression was unaltered over the course of 9 h in response to 1.0 mM Ni (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

AP-1 is induced by nickel (Ni). (A) Acute Ni exposure induced JUN and ATF2 protein expression. BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 mM Ni for 24 h. (B) Acute Ni exposure induced FOS protein expression in a time-dependent manner. BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for 12 h. JUN, ATF2, and FOS protein expression were analyzed by western blot analysis using antibodies against JUN, ATF2, and FOS. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software, and are presented as fold change relative to the control group after normalizing for b-actin or b-tubulin. (C) Acute Ni exposure induced FOSL1 mRNA expression. BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 0 and 0.5 mM Ni for 24 h. (D) NUPR1 is overexpressed in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells. Total RNA was extracted from BEAS-2B cells following exposure to Ni. NUPR1 and FOSL1 mRNA levels were assessed using RT-qPCR. Gene expression levels were normalized to actin, and are presented as fold change relative to the control group. All data shown are the mean ± SD from qPCRs performed in triplicate. **P<0.01. AP-1, activator protein 1; NUPR1, nuclear protein 1.

Transcription factor AP-1 is a heterodimer complex consisting of subunits from numerous protein subfamilies [reviewed in ref. (26)]. In lieu of this, the expression of additional AP-1 subunits was investigated following exposure to Ni. BEAS-2B cells were exposed to a single dose of 0.5 mM Ni for 24 h. FOSL1, a FOS-related member of the AP-1 complex, was found to be transcriptionally induced by Ni (Fig. 2C). However, no other AP-1 subunits investigated (i.e. JUNB, JUND, FOSL2, FOSB, and JDP2) were found to be highly elevated (data not shown). Collectively, these results showed that following Ni exposure, AP-1 subunits, JUN and ATF2, were dose-dependently induced and remained induced through 24 h in response to Ni exposure and likely contribute to NUPR1 induction over this time period. FOS, however, was quickly and transiently induced in response to Ni exposure, which indicates that FOS may be an early-response gene responsible for increased NUPR1 expression during the first 12 h of exposure.

NUPR1 is induced in nickel-transformed BEAS-2B cells

NUPR1 was previously demonstrated to be important in Cr(VI)-induced cell transformation (10). Therefore, NUPR1 expression was measured in Ni-transformed cells. Real-time PCR was used to measure the mRNA expression of NUPR1 in Ni-transformed clones, and we observed increased expressions of NUPR1 mRNA in 4 out of 5 Ni-transformed clones, with extremely high levels in Ni-2 clones (Fig. 2D). Overall, the ability for Ni to induce NUPR1 in BEAS-2B cells and elevated expression of NUPR1 in BEAS-2B cells transformed by Ni suggests that NUPR1 likely plays a role in Ni-mediated carcinogenesis.

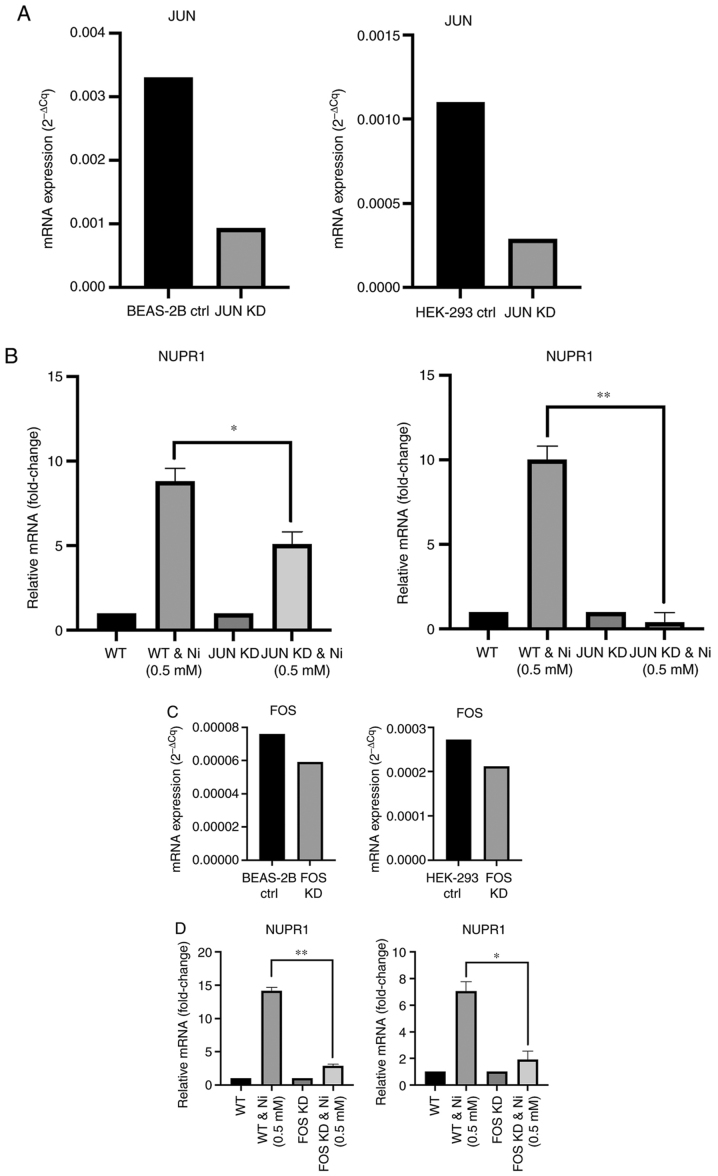

Knockdown of AP-1 suppresses NUPR1 induction by nickel

Since both AP-1 and NUPR1 were determined to be induced by Ni (Figs. 1 and 2) and AP-1 binding sites are present in the NUPR1 promoter, transcriptional induction of NUPR1 by AP-1 was investigated. Both JUN and FOS were transiently knocked down in BEAS-2B and 293 cells, and were exposed to 0.5 mM Ni for 24 h. JUN mRNA expression was reduced by at least 70% in both BEAS-2B and 293 cells (Fig. 3A). In both BEAS-2B and 293 cells silencing of JUN attenuated NUPR1 induction by Ni from 8.8 to 5.1-fold and 10 to 0.4-fold, respectively (Fig. 3B). FOS silencing was found to be highly lethal in both BEAS-2B and 293 cells, and knockdown efficiencies of only approximately 20% were achievable (Fig. 3C). Despite the low knockdown efficiency, FOS knockdown in both BEAS-2B and 293 cells also reduced NUPR1 induction from 14.1 to 2.8-fold and from 7.0 to 1.9-fold, respectively (Fig. 3D). These data support the notion that AP-1 is important in NUPR1 mRNA induction in response to Ni exposure in both BEAS-2B and 293 cells.

Figure 3.

Transient knockdown of JUN or FOS suppresses NUPR1 induction by nickel (Ni). (A) JUN mRNA expression and knockdown efficiency in BEAS-2B (left) and 293 (right) cells. (B) BEAS-2B (left) or 293 (right) cells were transfected with JUN siRNA (JUN KD), and either unexposed or exposed to 0.5 mM Ni for 24 h. NUPR1 mRNA was then assessed. (C) FOS mRNA expression and knockdown efficiency in BEAS-2B (left) and 293 (right) cells. (D) BEAS-2B (left) or 293 (right) cells were transfected with FOS siRNA (FOS KD), and either unexposed or exposed to 0.5 mM Ni for 24 h. NUPR1 mRNA was then assessed. Knockdown efficiencies of JUN or FOS were determined by measuring JUN or FOS expression in control siRNA (ctrl) cells compared to JUN or FOS expression in knockdown cells. Total RNA was extracted from transfected BEAS-2B and 293 cells or non-transfected BEAS-2B or 293 cells exposed to Ni. NUPR1 mRNA levels were measured by RT-qPCR. Gene expression levels were normalized to actin, and are presented as fold change relative to the control group. All data shown are the mean ± SD from qPCRs performed in triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. NUPR1, nuclear protein 1.

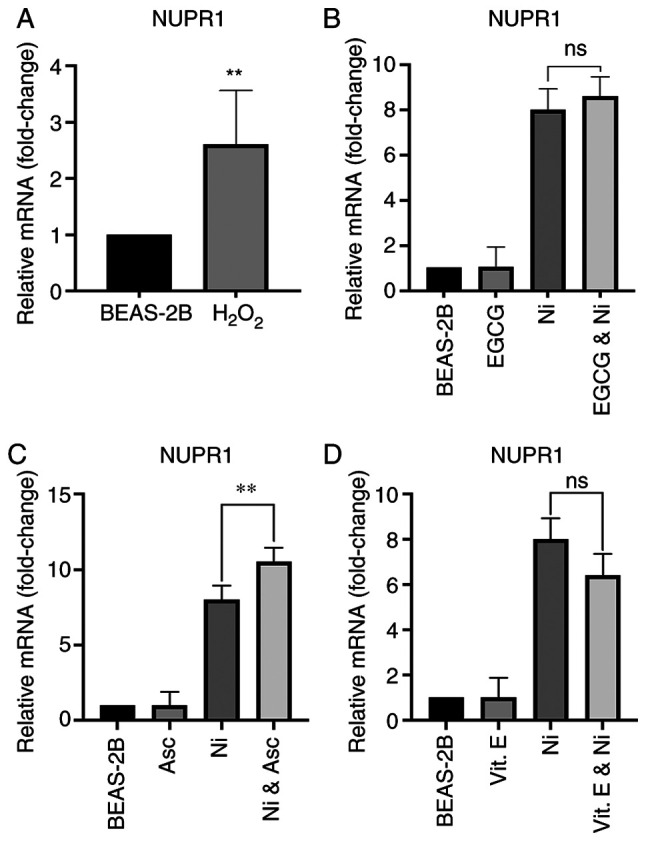

Reactive oxygen species induce NUPR1 and antioxidants do not prevent NUPR1 induction by nickel

ROS upregulates AP-1, specifically JUN and FOS at the transcriptional level [reviewed in ref. (26)]. In addition, Ni exposure produces time- and dose-dependent increases in ROS (26). Albeit, ROS generation by Ni is relatively low compared to that generated by other metals such as cobalt or chromate, and is generally not considered a major mechanism of Ni-mediated carcinogenesis (20,26). Therefore, due to the connection between ROS and AP-1 induction and the capacity for Ni to generate some degree of ROS, the possibility that ROS induces NUPR1 was investigated. BEAS-2B cells were treated with 0.1 mM of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 6 h, and NUPR1 mRNA expression was measured. As shown in Fig. 4A, H2O2 was capable of inducing NUPR1 in BEAS-2B cells; however, compared to 8-fold increase on NUPR1 mRNA by 6 h Ni exposure, NUPR1 induction by H2O2 (2.5-fold) was considerably lower. In order to further investigate a possible connection between ROS production by Ni and NUPR1 induction, BEAS-2B cells were co-treated with antioxidant and ROS scavenger, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG; 0.025 mM), and Ni (1.0 mM) for 6 h. Co-treatment with EGCG was not able to significantly prevent NUPR1 induction by Ni (Fig. 4B). In addition, BEAS-2B cells were pre-treated for 2 h with 0.1 mM (Asc) or 0.1 mM vitamin E (vit. E) and then exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for 6 h. Pre-treatment with either antioxidant was also unable to prevent NUPR1 induction by Ni (Fig. 4C and D). On the contrary, pre-treatment with ascorbate followed by Ni exposure actually significantly increased NUPR1 expression compared to Ni alone (Fig. 4C). This may be due to the fact that tissue culture media lacks the amount of ascorbate found in vivo, and usually only contains approximately 0.05 mM ascorbate, which is the amount in 10% fetal bovine serum. High levels of ascorbate can be toxic to tissue culture cells because ascorbate can also be a pro-oxidant. Collectively, these results suggest that NUPR1 induction by Ni primarily occurs through a mechanism other than ROS generation.

Figure 4.

ROS induces NUPR1 and antioxidants do not prevent NUPR1 induction by nickel (Ni). (A) Acute exposure to H2O2 induced NUPR1 expression. Total RNA was extracted from unexposed BEAS-2B cells and BEAS-2B cells exposed to 0.1 mM H2O2 for 6 h. (B) EGCG does not prevent NUPR1 induction by Ni. Total RNA was extracted from unexposed BEAS-2B cells, BEAS-2B cells exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for 6 h, BEAS-2B cells exposed to 0.025 mM EGCG for 6 h, and BEAS-2B cells co-treated with 0.025 mM EGCG and 1.0 mM Ni for 6 h. (C) Ascorbate (Asc) does not prevent NUPR1 induction by Ni. Total RNA was extracted from unexposed BEAS-2B cells, BEAS-2B cells exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for 6 h, BEAS-2B cells exposed to 100 µM ascorbate for 6 h, and BEAS-2B cells pre-treated with 100 µM ascorbate for 2 h and then exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for 6 h. (D) Vitamin E (Vit. E) was unable to significantly reduce NUPR1 induction by Ni. Total RNA was extracted from unexposed BEAS-2B cells, BEAS-2B cells exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for 6 h, BEAS-2B cells exposed to 100 µM vit. E for 6 h, and BEAS-2B cells pre-treated with 100 µM vit. E for 2 h and then exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for 6 h. NUPR1 mRNA levels were measured by RT-qPCR. Gene expression levels were normalized to actin, and are presented as fold change relative to the control group. All data shown are the mean ± SD from qPCRs performed in triplicate. **P<0.01; ns, not significant. ROS, reactive oxygen species; NUPR1, nuclear protein 1; EGCG, (−)-epigallocatechin gallate.

Transcriptional regulation of NUPR1

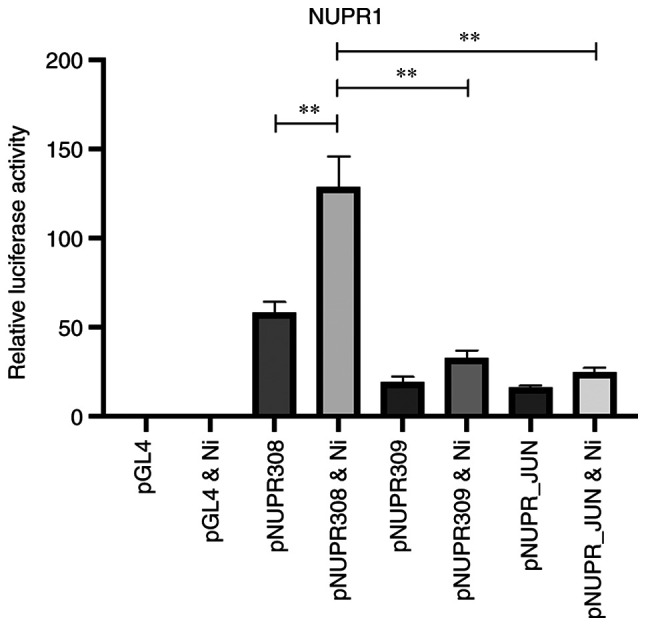

The NUPR1 promoter contains binding sites for numerous transcription factors involved in cellular stress including xenobiotic response elements, antioxidant response elements, and binding sites for x-box-binding protein 1, which classically functions in the unfolded protein response. In order to fully elucidate the mechanism for NUPR1 transcriptional activation and induction following exposure to Ni, deleted segments of varying length of the NUPR1 promoter were made and BEAS-2B cells were stably transfected with luciferase gene reporter constructs containing either the full-length NUPR1 promoter (construct pNUPR308), or a series of luciferase gene reporter constructs containing the NUPR1 promoter with deleted segments, which ranged in size from 299–2074 base pairs in length (Fig. S1A). Stable transfectants were treated with 1.0 mM Ni for 24 h to determine the regions responsible for NUPR1 transactivation. Fig. 5 shows NUPR1 promoter activity of the full-length NUPR1 promoter (pNUPR308) with and without Ni exposure. Luciferase activity in Ni-treated transfectants with the full-length promoter (pNUPR308) was significantly higher than unexposed full-length promoter transfectants (128-fold vs. 58-fold, respectively), which demonstrates that the NUPR1 promoter is highly active following exposure to Ni and is consistent with increased NUPR1 expression.

Figure 5.

The upstream region within the NUPR1 promoter is partially responsible for induction of NUPR1. Constructs pNUPR308 containing the full-length NUPR1 promoter, pNUPR309 containing the NUPR1 promoter with the upstream most 299 base pairs deleted, and pNUPR_JUN with the JUN binding site deleted driving the luciferase gene. Following transfection, cells were exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for 24 h, and luciferase activity was then determined. All data shown are the mean ± SEM from experiments performed in triplicate. **P<0.01. NUPR1, nuclear protein 1.

Luciferase activity in stable transfectants containing the NUPR1 promoter with various deletions following exposure to 1.0 mM Ni for 24 h was subsequently evaluated. A striking reduction in luciferase activity for both unexposed and Ni-exposed stable transfectants containing the NUPR1 promoter with the upstream most 299 base pairs deleted (pNUPR309; NUPR1 promoter −2135 to +713) was found (Fig. 5). From these results, it was inferred that this region must be important for high levels of NUPR1 transactivation. However, to determine which transcription factor(s) is critical to NUPR1 transactivation following Ni exposure, the NUPR1 promoter requires extensive examination by deleting specific transcription factor binding sites.

AP-1 subunits, JUN and FOS, were determined to be induced following Ni exposure in BEAS-2B cells. Additionally, knockdown of JUN and FOS significantly suppressed NUPR1 induction by Ni. Both JUN and FOS (i.e. AP-1) have broad transcriptional repertoires, and are involved in many aspects of tumor biology including tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis and survival of tumor cells, and invasive growth and angiogenesis (reviewed in (25). Moreover, a putative JUN binding site is located in this upstream most region of the NUPR1 promoter (−2339 to −2333). Consequently, the role that JUN plays in the transcriptional upregulation of NUPR1 was investigated. An NUPR1 promoter construct without the JUN binding site corresponding to position (−2339 to −2333) was generated (pNUPR_JUN; Fig. S1B). BEAS-2B cells were then stably transfected with the construct, and exposed to 1.0 mM Ni for 24 h or were unexposed. Fig. 5 shows that upon deleting the JUN binding site at (−2339 to −2333), a significant reduction in promoter activity in both the Ni exposed and unexposed cells was detected. This decrease in promoter activity mimics that which was generated using the NUPR1 promoter construct deletion corresponding to pNUPR309; NUPR1 promoter (−2135 to +713). Therefore, we conclude that the JUN binding site at position (−2339 to −2333) in the NUPR1 promoter is important for NUPR1 transactivation and that JUN acts by enhancing NUPR1 transactivation.

NUPR1 knockdown suppresses proliferation and colony formation in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells

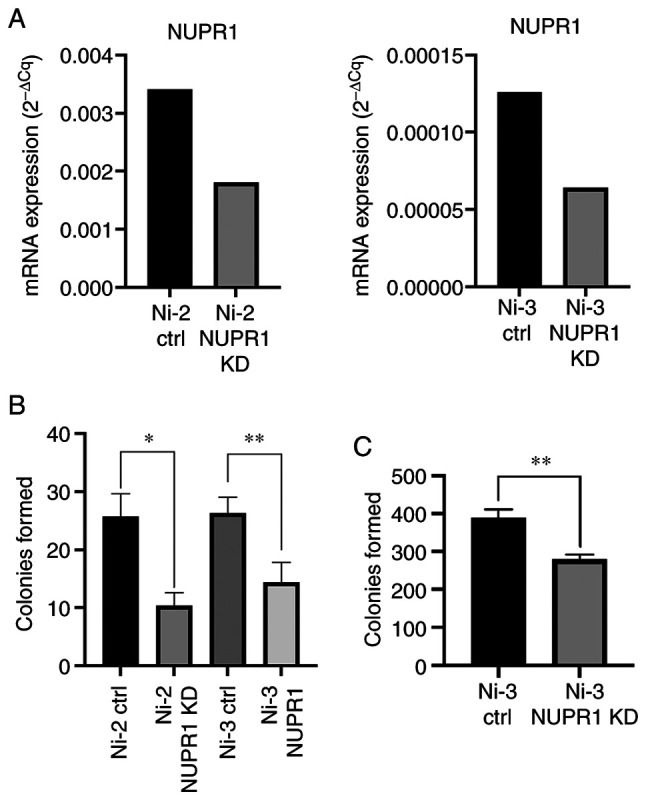

It has been reported on several occasions that NUPR1 expression is associated with tumorigenesis in vivo, and in non-small cell lung cancer cells, NUPR1 knockdown has been reported to reduce cell proliferation and colony formation ability (4,12). Therefore, the role that NUPR1 plays in cell proliferation in Ni-transformed cells was investigated. Ni-transformed cells were originally generated by treating BEAS-2B cells with Ni for 30 days and selecting single colonies that developed the ability to grow anchorage-independently in soft agar over a 4 week period (16). Ni-transformed cells were stably transfected with either control shRNA (ctrl) or NUPR1 shRNA (NUPR1 KD). Knockdown efficiencies in two Ni-transformed cell lines were determined to be approximately 50% (Fig. 6A). A colony formation assay was performed with NUPR1 knockdown Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells to determine if NUPR1 knockdown suppresses colony formation and cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 6B, colony formation was significantly suppressed in both Ni-transformed cell lines upon NUPR1 knockdown. Representative images are shown in Fig. S2A. Therefore, NUPR1 likely played an important role in cell proliferation in both Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells.

Figure 6.

Stable knockdown of NUPR1 reduces colony formation and anchorage-independent growth in nickel (Ni)-transformed cells. (A) NUPR1 mRNA expression in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells. NUPR1 knockdown efficiencies were determined by measuring NUPR1 expression in control shRNA (ctrl) cells compared to NUPR1 expression in knockdown cells (NUPR1 KD). (B) Colony formation in NUPR1 knockdown Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells. Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells stably transfected with NUPR1 shRNA (NUPR1 KD) or control shRNA (ctrl), seeded at 200 cells/100 mm dish, and cultured for 3 weeks. (C) Anchorage-independent growth in NUPR1 knockdown Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells. Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells stably transfected with NUPR1 shRNA (NUPR1 KD) or control shRNA (ctrl), seeded at 5,000 cells/well, and cultured for 2 weeks. All data shown are the mean ± SEM from experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. NUPR1, nuclear protein 1.

In normal epithelial cells the occurrence of anoikis, or programmed cell death by disruption of the interactions with the extracellular matrix in suspension culture, renders cells anchorage-dependent (27–29). In most squamous epithelial cells and their transformed counterparts, growth in single-cell suspension is prevented, as cells undergo differentiation and ultimately anoikis (29). Anchorage-independent growth is considered a hallmark of cancer cell growth, particularly with respect to metastatic potential, and therefore, was assessed as an indicator of cell transformation and chemical carcinogenesis (30,31). NUPR1 overexpression was previously shown to induce cell transformation and knockdown of NUPR1 prevented Cr(VI)-induced cell transformation (10). Since Ni-transformed cells showed reduced cell proliferation when NUPR1 was stably knocked down, we sought to determine if Ni-transformed-NUPR1 knockdown cells would forfeit their ability to grow anchorage-independently. Results from the anchorage-independent growth assay showed reduced colony formation in soft agar in NUPR1 knockdown Ni-transformed cells compared to Ni-transformed shRNA control cells (Fig. 6C). Representative images of soft agar colonies are also depicted in Fig. S2B. From this it can be concluded that NUPR1 likely plays an important role in anchorage-independent growth in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells.

Discussion

Nuclear protein 1 (NUPR1) is a highly-sensitive stress response protein that can be induced by a myriad of chemical and biological stressors, and is upregulated in many cancers including those originating in the lungs, breast, pancreas, and colon, among others (11). However, the mechanisms and stressors capable of inducing NUPR1 remain largely understood. NUPR1 upregulation is significant because NUPR1 can permit cells to cope with high degrees of cellular stress and damage, and inadvertently confer a growth advantage under such conditions. In tumor cells, NUPR1 upregulation may facilitate an adaptive response to unfavorable conditions, paving the way for cancer progression. As described herein, Ni is a well-known human carcinogen that induces NUPR1, yet the mechanisms of Ni-mediated carcinogenesis have not yet been fully described. This is the first study showing that Ni can induce NUPR1 and that explores the mechanism of NUPR1 induction by Ni.

NUPR1 mRNA and protein expression levels were highly induced in BEAS-2B cells following acute exposure to Ni, which indicates that Ni is a potent inducer of NUPR1. Notably, no significant time-dependent difference in NUPR1 mRNA expression in unexposed BEAS-2B cells over 12 h was detected (data not shown). This contrasts a previous report whereby NUPR1 mRNA expression was shown to be induced following cell culture medium change in murine embryonic fibroblast (NIH 3T3) cells (32). Induction of NUPR1 by routine medium change was determined to be due to the presence of thermolabile factors in conditioned medium that block activation of stress-sensitive protein kinases and NUPR1 expression (32). Due to the fact that NUPR1 is overexpressed in lung cancers (11), NUPR1 expression was evaluated in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells. NUPR1 was determined to be upregulated in 4 out of 5 Ni-transformed clones. Since NUPR1 was induced following Ni exposure in BEAS-2B cells and was upregulated in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells, it is likely that NUPR1 plays a role in Ni-mediated carcinogenesis.

Multiple AP-1 binding sites are located in the NUPR1 promoter, and Ni was previously shown to induce AP-1 (22–24). In addition, carcinogenic metal Cr(VI) was previously shown to open chromatin around AP-1 sites in the NUPR1 promoter (33). ChIP-seq data (ENCODE) also show the binding of AP-1 around the promoter region of NUPR1. Therefore, the possibility that Ni induces AP-1, namely JUN, FOS, and ATF2, was investigated. Protein and mRNA expression analysis confirmed that AP-1 subunits (i.e. JUN, FOS, and ATF2) were also induced following Ni exposure. FOS was quickly and transiently induced after only 1 h, and JUN and ATF2 proteins were found to be induced after 12 h of Ni exposure. These observations suggest that FOS is one of the AP-1 subunits involved in the initial response to Ni, and that additional AP-1 subunits respond over time to Ni exposure. Therefore, it is suspected that AP-1 subunits (i.e. JUN, FOS, and ATF2) may be responsible for NUPR1 transactivation.

To confirm that AP-1 transcriptionally regulates NUPR1 in response to Ni, both JUN and FOS were silenced in BEAS-2B cells and cells were then exposed to Ni. NUPR1 expression was significantly suppressed after silencing either JUN or FOS in BEAS-2B cells and exposed to Ni for 24 h. The involvement of JUN in NUPR1 transcription was further demonstrated by cloning the NUPR1 promoter, and creating a series of deletions in the promoter region. By subsequently deleting a JUN binding site in the NUPR1 promoter region corresponding to position (−2339 to −2333), it was determined that JUN enhanced NUPR1 transactivation.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are capable of inducing AP-1, particularly JUN and FOS at the transcriptional level, and although Ni only generates a relatively small amount of oxidative stress compared to other carcinogenic metals, such as Cr(VI) and cobalt, this relationship was investigated (34). BEAS-2B cells were treated with H2O2 (100 µM for 6 h), and NUPR1 mRNA levels were increased, albeit to a much lesser magnitude than observed following Ni exposure. BEAS-2B cells were then either co-treated or pre-treated with ROS scavenger EGCG, ascorbate, or vitamin E, and exposed to Ni. NUPR1 induction by Ni was unable to be prevented by any of the antioxidants tested. NUPR1 expression remained highly elevated in BEAS-2B cells co- or pre-treated with antioxidants and EGCG. Therefore, NUPR1 was capable of being induced by ROS, but oxidative stress is likely not responsible for NUPR1 induction by Ni.

Silencing of NUPR1 in human lung cancer cells was previously shown to reduce cell proliferation (12). It has also been shown that NUPR1 acts as an oncogene, in part, by enhancing cell proliferation in cells overexpressing NUPR1 (35). Therefore, the colony formation ability of NUPR1 knockdown Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells was assessed, and reduced colony formation was observed. This suggests that NUPR1 may aid in cell proliferation ability in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells, thereby conferring carcinogenic potential. In Cr(VI)-treated BEAS-2B cells, NUPR1 knockdown was previously shown to reduce anchorage-independent growth, which is considered a hallmark of carcinogenesis (10). In Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells, NUPR1 knockdown also was able to significantly reduce anchorage-independent growth. Overall, the data presented demonstrate that AP-1 is partly responsible for NUPR1 transactivation following Ni exposure, and that NUPR1 plays an important role in Ni-mediated carcinogenesis. However, the precise mechanism that lies upstream of AP-1 which governs NUPR1 induction following Ni exposure remains unclear.

AP-1 is regulated by the activation of mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK), which are classically thought of as first responders to environmental signals (36). Activation of the MAPK pathway comprises phosphorylation and activation of key proteins in MAPK signaling: ERK1/2, JNK1/2/3, and p38 MAPK (36). Ni has, on several occasions, been shown to influence MAPK signaling, which may therefore be responsible for NUPR1 induction (24,37–39). Likewise, Ni has also been shown to potentiate NF-κB signaling, which cross talks with AP-1 and is therefore another potential candidate that may mediate NUPR1 induction by Ni (22,24,38,40). Furthermore, both HIF1-α and AP-1 are induced by hypoxia signaling, which is mimicked by Ni, and both HIF1-α and AP-1 have been shown to cooperate in the transcription of various genes associated with cancer development and progression (13,41,42). Therefore, it is plausible that Ni induces the AP-1/NUPR1 signaling axis by activating of one of these upstream mediators. Further research is needed in order to unveil the specific mechanism responsible for induction of the AP-1 and subsequently, NUPR1, by Ni. In conclusion, Ni induces NUPR1 through AP-1 (i.e. JUN and FOS), and the activation of this pathway has the potential to contribute to carcinogenesis brought on by Ni and the progression of cancers associated with Ni exposure. Given that NUPR1 is also induced by Cr(VI), NUPR1 induction may be a shared phenomenon among carcinogenic metals that contributes to their carcinogenic potential. This possibility requires additional research, but if discovered, would be a significant finding because it would help bridge the knowledge gap in how exposure to various metals causes cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (ES000260, ES022935, ES023174, and ES026138 to MC; ES029359, ES026138, and ES030583 to CJ).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (ES000260, ES022935, ES023174, and ES026138 to MC; ES029359, ES026138, and ES030583 to CJ).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

AM designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. NR cloned the NUPR1 promoter. MC and CJ conceptualized the study. MC, CJ, and HS contributed to the interpretation of the results, and assisted in troubleshooting. All authors discussed the results, and contributed to the writing and revision of the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors state that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Malicet C, Hoffmeister A, Moreno S, Closa D, Dagorn JC, Vasseur S, Iovanna JL. Interaction of the stress protein p8 with Jab1 is required for Jab1-dependent p27 nuclear-to-cytoplasm translocation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malicet C, Giroux V, Vasseur S, Dagorn JC, Neira JL, Iovanna JL. Regulation of apoptosis by the p8/prothymosin alpha complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2671–2676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508955103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguado-Llera D, Hamidi T, Doménech R, Pantoja-Uceda D, Gironella M, Santoro J, Velázquez-Campoy A, Neira JL, Iovanna JL. Deciphering the binding between Nupr1 and MSL1 and their DNA-repairing activity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mu Y, Yan X, Li D, Zhao D, Wang L, Wang X, Gao D, Yang J, Zhang H, Li Y, et al. NUPR1 maintains autolysosomal efflux by activating SNAP25 transcription in cancer cells. Autophagy. 2018;14:654–670. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1338556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goruppi S, Patten RD, Force T, Kyriakis JM. Helix-loop-helix protein p8, a transcriptional regulator required for cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibroblast matrix metalloprotease induction. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:993–1006. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00996-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Montero AC, Vasseur S, Giono LE, Canepa E, Moreno S, Dagorn JC, Iovanna JL. Transforming growth factor beta-1 enhances Smad transcriptional activity through activation of p8 gene expression. Biochem J. 2001;357:249–23. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallo GV, Fiedler F, Calvo EL, Ortiz EM, Vasseur S, Keim V, Morisset J, Iovanna JL. Cloning and expression of the rat p8 cDNA, a new gene activated in pancreas during the acute phase of pancreatitis, pancreatic development, and regeneration, and which promotes cellular growth. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32360–32369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Averous J, Lambert-Langlais S, Cherasse Y, Carraro V, Parry L, B'chir W, Jousse C, Maurin AC, Bruhat A, Fafournoux P. Amino acid deprivation regulates the stress-inducible gene p8 via the GCN2/ATF4 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;413:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taïeb D, Malicet C, Garcia S, Rocchi P, Arnaud C, Dagorn JC, Iovanna JL, Vasseur S. Inactivation of stress protein p8 increases murine carbon tetrachloride hepatotoxicity via preserved CYP2E1 activity. Hepatology. 2005;42:176–182. doi: 10.1002/hep.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen D, Kluz T, Fang L, Zhang X, Sun H, Jin C, Costa M. Hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) down-regulates acetylation of histone H4 at lysine 16 through induction of stressor protein Nupr1. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy A, Costa M. Nuclear protein 1 imparts oncogenic potential and chemotherapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020;494:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo X, Wang W, Hu J, Feng K, Pan Y, Zhang L, Feng Y. Lentivirus-mediated RNAi knockdown of NUPR1 inhibits human nonsmall cell lung cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2012;295:2114–2121. doi: 10.1002/ar.22571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen QY, DesMarais T, Costa M. Metals and mechanisms of carcinogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;59:537–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McRae ME. Reston, VA: 2020. Mineral commodity summaries 2020: Nickel, in Mineral Commodity Summaries; p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- 15.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, corp-author. Arsenic, metals, fibres, and dusts. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100:11–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clancy HA, Sun H, Passantino L, Kluz T, Muñoz A, Zavadil J, Costa M. Gene expression changes in human lung cells exposed to arsenic, chromium, nickel or vanadium indicate the first steps in cancer. Metallomics. 2012;4:784–793. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20074k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slatko B, Heinrich P, Nixon BT, Voytas D. Constructing nested deletions for use in DNA sequencing. Curr Protoc Mol Biol Chapter. 2001;7 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0702s16. Unit7.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messeguer X, Escudero R, Farré D, Núñez O, Martínez J, Albà MM. PROMO: Detection of known transcription regulatory elements using species-tailored searches. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:333–334. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen QY, Murphy A, Sun H, Costa M. Molecular and epigenetic mechanisms of Cr(VI)-induced carcinogenesis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019;377:114636. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2019.114636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa M, Murphy A. Chapter 11-overview of chromium(III) toxicology. In: Vincent JB, editor. The Nutritional Biochemistry of Chromium (III) 2nd edition. Elsevier; 2019. pp. 341–359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz MT, Gonçalo M, Figueiredo A, Carvalho AP, Duarte CB, Lopes MC. Contact sensitizer nickel sulfate activates the transcription factors NF-kB and AP-1 and increases the expression of nitric oxide synthase in a skin dendritic cell line. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2004.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrew AS, Klei LR, Barchowsky A. AP-1-dependent induction of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 by nickel does not require reactive oxygen. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L616–L623. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.3.L616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding J, Huang Y, Ning B, Gong W, Li J, Wang H, Chen CY, Huang C. TNF-alpha induction by nickel compounds is specific through ERKs/AP-1-dependent pathway in human bronchial epithelial cells. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:81–90. doi: 10.2174/156800909787313995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eferl R, Wagner EF. AP-1: A double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nrc1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salnikow K, Su W, Blagosklonny MV, Costa M. Carcinogenic metals induce hypoxia-inducible factor-stimulated transcription by reactive oxygen species-independent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3375–3378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maeno K, Masuda A, Yanagisawa K, Konishi H, Osada H, Saito T, Ueda R, Takahashi T. Altered regulation of c-jun and its involvement in anchorage-independent growth of human lung cancers. Oncogene. 2006;25:271–277. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frisch SM, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:619–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kantak SS, Kramer RH. E-cadherin regulates anchorage-independent growth and survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16953–16961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mori S, Chang JT, Andrechek ER, Matsumura N, Baba T, Yao G, Kim JW, Gatza M, Murphy S, Nevins JR. Anchorage-independent cell growth signature identifies tumors with metastatic potential. Oncogene. 2009;28:2796–2805. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guadamillas MC, Cerezo A, Del Pozo MA. Overcoming anoikis-pathways to anchorage-independent growth in cancer. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3189–1397. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Montero A, Vasseur S, Mallo GV, Soubeyran P, Dagorn JC, Iovanna JL. Expression of the stress-induced p8 mRNA is transiently activated after culture medium change. Eur J Cell Biol. 2001;80:720–725. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ovesen JL, Fan Y, Zhang X, Chen J, Medvedovic M, Xia Y, Puga A. Formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE) analysis uncovers broad changes in chromatin structure resulting from hexavalent chromium exposure. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marinho HS, Real C, Cyrne L, Soares H, Antunes F. Hydrogen peroxide sensing, signaling and regulation of transcription factors. Redox Biol. 2014;2:535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Jiang F, Xia X, Zhang B. LncRNA FAL1 promotes carcinogenesis by regulation of miR-637/NUPR1 pathway in colorectal cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;106:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atsaves V, Leventaki V, Rassidakis GZ, Claret FX. AP-1 transcription factors as regulators of immune responses in cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1037. doi: 10.3390/cancers11071037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu Y, Wang Y, Zhou Q, Bowman L, Mao G, Zou B, Xu J, Liu Y, Liu K, Zhao J, Ding M. Inhibition of nickel nanoparticles-induced toxicity by epigallocatechin-3-gallate in JB6 cells may be through down-regulation of the MAPK signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magaye R, Zhou Q, Bowman L, Zou B, Mao G, Xu J, Castranova V, Zhao J, Ding M. Metallic nickel nanoparticles may exhibit higher carcinogenic potential than fine particles in JB6 cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang D, Li J, Wu K, Ouyang W, Ding J, Liu ZG, Costa M, Huang C. JNK1, but not JNK2, is required for COX-2 induction by nickel compounds. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:883–891. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujioka S, Niu J, Schmidt C, Sclabas GM, Peng B, Uwagawa T, Li Z, Evans DB, Abbruzzese JL, Chiao PJ. NF-kappaB and AP-1 connection: Mechanism of NF-kappaB-dependent regulation of AP-1 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7806–7819. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7806-7819.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michiels C, Minet E, Michel G, Mottet D, Piret JP, Raes M. HIF-1 and AP-1 cooperate to increase gene expression in hypoxia: Role of MAP kinases. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:49–53. doi: 10.1080/15216540252774766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Damert A, Ikeda E, Risau W. Activator-protein-1 binding potentiates the hypoxia-induciblefactor-1-mediated hypoxia-induced transcriptional activation of vascular-endothelial growth factor expression in C6 glioma cells. Biochem J. 1997;327:419–423. doi: 10.1042/bj3270419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.