Abstract

Th22 cells constitute a recently described CD4+ T cell subset defined by its production of interleukin (IL)-22. The action of IL-22 is mainly restricted to epithelial cells. IL-22 enhances keratinocyte proliferation but inhibits their differentiation and maturation. Dysregulated IL-22 production has been associated to some inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. How IL-22 production is regulated in human T cells is not fully known. In the present study, we identified conditions to generate Th22 cells that do not co-produce IL-17 from naïve human CD4+ T cells. We show that in addition to the transcription factors AhR and RORγt, the active form of vitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) regulates IL-22 production in these cells. By studying T cells with a mutated vitamin D receptor (VDR), we demonstrate that the 1,25(OH)2D3-induced inhibition of il22 gene transcription is dependent on the transcriptional activity of the VDR in the T cells. Finally, we identified a vitamin D response element (VDRE) in the il22 promoter and demonstrate that 1,25(OH)2D3-VDR directly inhibits IL-22 production via this repressive VDRE.

Keywords: Th22 cells, IL-22, IL-17, vitamin D, vitamin D receptor, vitamin D response element (VDRE)

Introduction

Various subsets of effector CD4+ T helper (Th) cells, classified by the lineage-specific master transcription factors they express and the cytokines they secrete, have been described (1, 2). Th22 cells constitute a recently described CD4+ T cell subset defined by their production of interleukin (IL)-22 (3, 4). The biological functions of IL-22 is mainly restricted to non-hematopoietic cells such as epithelial cells located in the skin, gut, lung, liver, pancreas and kidney (5–7). In the skin and gut epithelium, IL-22 induces secretion of several anti-microbial peptides that contribute to the defence mechanisms against microorganisms (8–10). Furthermore, IL-22 enhances proliferation of keratinocytes while inhibiting their differentiation and maturation, implying an important role of IL-22 in the homeostasis of the skin (11–13). The role of IL-22 in epithelial homeostasis is further underlined by its association to inflammatory skin and gut diseases such as atopic dermatitis (14, 15), psoriasis (16) and colorectal cancers (17). Th22 cells are closely related to Th17 cells, and Th17/Th22 cells co-producing IL-17A and IL-22 have been described (10, 18, 19). However, distinct IL-22-producing Th22 cells that do not produce IL-17 have been isolated from both humans (3, 4, 20) and mice (21).

Other types of immune cells than Th22 cells, such as innate lymphoid cells (ILC), γδ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells can produce IL-22 (22–24). It has been found that the transcription factor RORγt plays an important role in the regulation of IL-22 secretion in human and mouse ILC3 (25–28). Furthermore, IL-21 and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) play regulatory roles in IL-22 production in mouse CD4+ T cells (29). However, the transcription factors involved in IL-22 regulation in human Th22 cells are still not fully known. One study has found that both RORγt and AhR are important for Th22 differentiation and IL-22 production (20), whereas another study found that RORγt is undetectable in Th22 cells (4).

The active form of vitamin D3, 1,25(OH)2D3, modulates the expression of many genes via binding to the intracellular vitamin D receptor (VDR) (30, 31). Ligand-bound VDR form heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXR) and translocate to the nucleus (30, 31). Here, 1,25(OH)2D3-VDR : RXR heterodimers act as transcription factors by binding to vitamin D response elements (VDRE) located in the regulatory regions of vitamin D-regulated genes (30–34). Binding of 1,25(OH)2D3-VDR : RXR heterodimers to VDRE leads to either activation or repression of target gene transcription (32). Interestingly, 1,25(OH)2D3 regulates the differentiation of CD4+ T cells. Thus, 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes differentiation of Th2 cells by enhancing IL-4 production and concomitantly represses Th1 differentiation by repressing interferon (IFN) γ production. Moreover, 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes the differentiation of regulatory T (Treg) cells and inhibits Th17 cell differentiation (35–41). The effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on human Th22 cell differentiation and IL-22 secretion is not fully known. Some studies have suggested that 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes the differentiation of Th22 cells (4, 42), whereas other found that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits IL-22 production (43).

The aim of this study was to determine how 1,25(OH)2D3 controls IL-22 production in human T cells.

First, we established the conditions for in vitro differentiation of human naïve CD4+ T cells to Th22 cells. We found that activation of naïve CD4+ T cells with allogeneic dendritic cells (DC) in the presence of TNFα, IL-6, IL-23, IL-1β, the AhR agonist FICZ and the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) receptor type 1 inhibitor galunisertib led to optimal generation of Th22 cells. We confirmed that the transcription factors AhR and RORγt regulate IL-22 in these cells. Importantly, we found that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits IL-22 production in human Th22 cells. We show that 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated inhibition of IL-22 was not due to inhibition of AhR, RORγt or STAT-3. In contrast, we identified a novel VDRE in the il22 promoter by which 1,25(OH)2D3-VDR : RXR complexes directly represses IL-22 transcription.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Chemicals

TNFα (210-TA), IL-1β (201-LB), IL-6 (206-IL) and IL-23 (1290-IL) were purchased from R&D systems. Galunisertib (LY2157299) was purchased from Selleckchem. 1,25(OH)2D3 (BML-DM200-0050) were from, Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI. Stock 1,25(OH)2D3 solution of 2.4 mM were diluted in >99.5% ethanol anhydrous. AhR agonist (FICZ, 5304) and AhR antagonist (CH-223191, 3858) were from TOCRIS Inc. FICZ and CH-223191 were solubilized in DMSO to make a 25 mM and a 100 mM stock solution, respectively. RORγt antagonist (SR-2211) was from TOCRIS Inc. SR-2211 (4869) was solubilized in DMSO to make a 10 mM stock solution. Recombinant human IL-21 (200-21) was from PeproTech and anti-IL-21 (NBP1-76740) was from Novus Biologicals.

T Cell Isolation and Activation

All procedures involving the handling of human samples were in accordance with the principles described in the Declaration of Helsinki and the samples were collected and analysed according to ethically approval by the Regional Ethical Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (H-16033682). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were purified from healthy donor’s blood by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway). Subsequently, naive CD4+ T cells were isolated by negative selection using Easysep Human Naive CD4+ T cell Enrichment Kit (19155 Stemcell Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In short, PBMC were incubated with antibodies targeting undesired cells, and subsequently magnetic particles were used to bind undesired cells. Hereafter, these cells were retained using an EasySep Magnet (18000, Stemcell Technologies). The resulting cell population consisted of >95% naïve CD4+ T cells. The obtained cells were cultured at a concentration of 1 x 106 cells/ml serum-free X-VIVO 15 medium (BE02-060F, Lonza, Verviers, Belgium), and activated with allogeneic dendritic cells (DC) in a 1:10 DC:T cell ratio or activated with Dynabeads Human T-activator CD3/CD28 (111.31D, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) in a 2:5 bead:T cell ratio in flat-bottomed 24 well culture plates (142475, Nunc). T cells were activated for four days at 37°C, 5% CO2 under polarizing conditions for Th0 cells (un-supplemented X-VIVO 15 medium) and Th22 cells (X-VIVO 15 medium supplemented with TNF (10 ng/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), IL-6 (30 ng/ml), IL-23 (20 ng/ml), FICZ (0.3 µM) and galunisertib (10 µM)). In some experiments CH-223191, SR-2211, 1,25(OH)2D3, anti-IL-21 and recombinant human IL-21 were added at the indicated concentrations to the medium during the activation period. For kinetic experiments, naïve CD4+ T cells were cultured in flat-bottomed 24-well culture plates in X-VIVO 15 medium and activated with beads or with allogeneic dendritic cells as described above in the presence of Th22 polarizing conditions for 0-144 h.

Dendritic Cell Differentiation

Dendritic cells (DC) were differentiated from isolated human monocytes. Human monocytes were purified from PBMC using Easysep Human Monocyte Enrichment Kit (19059, Stemcell Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 1.5 x 106 monocytes were cultured in flat-bottomed 6-well culture plates (140675, Nunc) for six days in 3 ml DC medium (RPMI-1640 medium (R5886, Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 1% L-Glutamine and 10% heat-inactivated and endotoxin-free fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10082-147, Gibco)) in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 (both 50 ng/ml, AF-HDC, Peprotech). After three days, fresh DC medium was added. On day five, differentiated DC were supplemented with GM-CSF (50 ng/ml) and treated with heat-killed mycobacterium Tuberculosis (HKMT) (10 ng/ml) (tlrl-hkmt, InvivoGen) for 24 h. Activated DC were washed with PBS and resuspended in X-VIVO 15 for mono- and co-cultures. For mono-culture, 5 x 105 DC/ml were cultured in flat-bottomed, 24-well plates and activated for 0-120 h with the indicated concentration of HKMT under Th22 polarizing conditions. For co-culture experiments, 1 x 106 naïve human CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with 1 x 105 allogeneic DC per ml in flat-bottomed, 24-well culture plates in X-VIVO 15 medium under Th22 polarizing conditions.

Cell Lines

The malignant T cell line MyLa 2059 was previously established from a plaque biopsy specimen of a patient with cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) (44). 5 x 105 cells/ml were cultured in flat-bottomed, 24-well plates in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 1% L-Glutamin and 10% heat-inactivated and endotoxin-free FBS in the absence or presence of Th22 polarizing conditions and the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 for 48 h.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry

Anti-CD4 BV711 (SK3), anti-CD80 BV605 (L307), anti-CD25 PE-Cy7 (M-A251), anti-CD38 BV421 (HIT2) were purchased from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Fixable viability dye (efluor 780) was purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Anti-IL-17 APC (EBIO64DEC17) and anti-IL-22 PE (22URTI) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Life Technologies Europe BV, Roskilde, DK). Anti-IgG1k APC (QA16A12) was purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA) and anti-IgG1k PE (MOPC-21) was purchased from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). For analyses of intracellular cytokines, cells were re-stimulated with PMA (1 µg/ml) (P8139, Sigma), ionomycin (1 µg/ml) (I0634, Sigma) in the presence of monensin (2 µg/ml) (M5273, Sigma) for 4 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. The cells were stained for surface markers, fixed and permeabilized with the Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (BD Bioscience) and subsequently stained cytokine-specific antibodies. The cells were analysed on a Fortessa 5 laser flow cytometer using FACSDiva software and further analysed using FlowJo software. Neutralizing anti-IL-21 antibodies (NBP1-76740) were from Novus Biologicals.

RT-qPCR

mRNA levels for various targets were measured by RT-qPCR. Following cell isolation, cells were lysed in TRI reagent (T9424, Sigma Aldrich) and mixed with phase separation reagent 1-bromo-3-chloropropane (B9673, Sigma Aldrich). The RNA phase was isolated and mixed with isopropanol supplemented with glycogen for RNA precipitation (10814-010, Invitrogen). The RNA pellet was then washed in RNase free 75% ethanol 3 times. cDNA was synthesized from quantified RNA using High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA™ Kit (4387406, Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For RT-qPCR, 12.5 ng of cDNA was mixed with TaqMan® Universal Master Mix II with UNG (4440038, Applied the target primer and RNase and DNase free water for normalization. The following target primers were used: IL-22 (Hs01574154_m1), STAT-3 (Hs01047580_m1), AhR (Hs00907314_m1), RORc (Hs01076122_m1), IL-21 (Hs00222327_m1), GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1). The plate-based detection instrument LightCycler ® 480 II from Roche was used for real-time PCR amplification.

Cytokine Measurements

IL-17A and IL-22 in the supernatant were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer´s instruction (InVitroGen, IL-17A 88-7176-22 and IL-22 88-7522-88).

Western Blotting Analysis

For Western blotting analysis, cells were lysed with lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-base, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2 supplemented with 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1 x Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (5872S, Cell Signalling Technology) and 5 mM EDTA. The lysates were vortexed for 5 seconds every 5 minutes for 25 minutes at room temperature and subsequently centrifuged at 10.000 G for 10 minutes at 4°C. Loading buffer containing lithium dodecyl sulphate (LDS) (NP0007, Life Technologies) along with reducing agent (NP0009, Life Technologies) was added and the lysates separated by electrophoresis through NuPAGE™ 10% BisTris gels (NP0302BOX or NP0301BOX, Life Technologies). The proteins were transferred to nitrocelulose membranes (LC2001, Life Technologies). The membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline with 0,1% tween (TBST), washed 3 times in TBST for 3 minutes and incubated overnight at 4°C with target-specific primary antibodies (anti-STAT-3 (D1B2J) and anti-phospho-STAT3 (9145) from Cell Signaling Technology, anti-VDR (D-6), anti-AhR (sc-5579), anti-RORγt (sc-293150) and anti-GAPDH (sc-365062) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted in TBST supplemented with 5% BSA. The membranes were subsequently washed and incubated with a secondary antibody (swine anti-rabbit Ig or rabbit anti-mouse Ig (P0399 and P0260 from Dako, Glostrup, Denmark S/A), conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and diluted in 5% skim milk. Finally, membranes were washed and exposed to ECL luminescence reagent (RPN2232, Sigma Aldrich). The corresponding signals were detected using a ChemiDocTM MP Imaging System (Bio Rad) and the software ImageLab.

Plasmids

To investigate the presence of VDRE in the il22 promoter, bioinformatics analysis of the il22 gene (HGNC : HGNC:14900) was performed using JASPAR, an open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles, where several combinations of the VDR-RXR complex binding profile on several genes are described (45). The cloning of the il22 promoter into the pMCS Tluc16 Hygro Vector expressing luciferase (88255 from ThermoFisher Scientific) was performed by using the restriction enzymes KpnI and Hind III via Invitrogen GeneArt Gene Synthesis. The generated plasmid construct contained the il22 promoter, including the putative VDRE located 2159-2173 bases upstream from the start codon, driving the expression of Tluc16 luciferase gene (IL-22-Tluc VDRE-WT) and having the antibiotic resistance genes ampicillin (AmpR) and hygromycin (HygroR).

Directed Mutagenesis

The generation of the construct IL-22-Tluc with deletion of the VDRE (IL-22-Tluc VDRE-KO) was performed using the GeneArt™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis System (A13282, ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol for long plasmids ~10 Kb. The following primers were designed and used to remove the VDRE:

Forward primer: 5’-ATTCCTTCTAATTGTATCGTACCTCTCCCCATCCTCCT-3’

Reverse primer: 5’-AGGAGGATGGGGAGAGGTACGATACAATTAGAAGGAAT -3’

Luciferase Assay

Nucleofection of 5 x 105 Myla 2059 cells/well with 200 ng of the constructs IL-22-Tluc VDRE-WT and IL-22 VDRE-KO were performed using the P3 Primary Cell 96-well Nucleofector™ Kit (V4SP-3096) and program EH-140 on the Lonza Nucleofector 96-well Shuttle (LZ-AAM-1001S). Subsequently, 5 x 105 electroporated cells/ml were cultured in flat-bottomed 24-well plates in RPMI-1640 with 1% L-glutamine and 10% heat-inactivated and endotoxin-free fetal bovine serum in the presence of the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 48 h of incubation, luciferase activity was measured as counts per second (CPS) using the TurboLuc™ Luciferase One-Step Glow Assay Kit (88263) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical Analysis

Two-tailed, paired Student’s t-tests were used to compare responses in the same group of cells treated in two different ways. Significance levels are indicated as follows: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.005; **** p < 0.001. Data are presented as mean values with one standard error of the mean (SEM). The number of donors as well as the number of independent experiments are indicated in the figure legends.

Results

Differentiation of Human Th22 Cells In Vitro

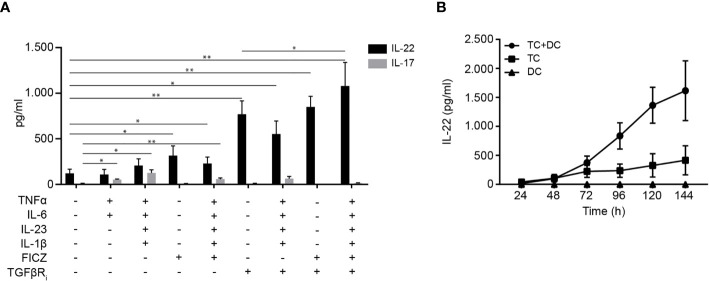

Presently, there is no consensus on the conditions required for in vitro generation of human Th22 cells. One study has identified IL-1β and IL-23 as the optimal cytokine cocktail to generate Th22 cells that do not produce IL-17 (20), whereas another study found that tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-6 were required for optimal Th22 cell generation (4). To establish conditions for efficient differentiation of human CD4+ T cells to Th22 cells in a physiological-like setting, we activated naïve CD4+ T cells with allogeneic DC and investigated the combinatory effect of several factors believed to induce IL-22 transcription. After 96 h of culture, we measured IL-22 and IL-17 in the supernatant. In our hands, neither the IL-1β/IL-23 nor the TNF/IL-6 combination significantly increased IL-22 production compared to untreated cells (Figure 1A). The combination of TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 induced both IL-22 and IL-17 secretion (Figure 1A). The AhR agonist FICZ and the TGF-βR inhibitor galunisertib markedly increased IL-22 secretion without stimulating IL-17 secretion. Although modestly, addition of FICZ and the cytokines to galunisertib significantly increased the secretion of IL-22 without increasing the secretion of IL-17. Thus, in our hands medium supplemented with TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23, FICZ and galunisertib (from here on termed Th22 medium) resulted in optimal differentiation of human naïve CD4+ T cells towards Th22 cells that secreted high levels of IL-22 and no IL-17 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Differentiation of human Th22 cells in vitro. (A) IL-22 and IL-17 in the supernatant of naïve CD4+ T cells co-cultured with allogeneic DC for 96 h in the absence or presence of TNFα (10 ng/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), IL-6 (30 ng/ml) IL-23 (20 ng/ml), FICZ (0.3 µM) and TGFβR inhibitor (galunisertib,10 µM), (mean + SEM, two independent experiments with 5 donors). (B) IL-22 in the supernatant of DC-T cell co-cultures, T cell mono-cultures activated with CD3/CD28 beads and DC mono-cultures after 24-144 h of culture in Th22 medium (mean ± SEM, two independent experiments with 4 donors).

Next, we wanted to characterize differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells in mono-cultures versus in co-cultures with allogeneic DC and furthermore to determine the time required for efficient differentiation to Th22 cells and secretion of IL-22. To do this, we measured the IL-22 concentration at day 1-6 in the supernatants of allogeneic DC-T cell co-cultures, of mono-cultures of CD4+ T cells activated with CD3/CD28 beads and of mono-cultures of activated DC all in Th22 medium. We found that the allogeneic DC-T cell co-cultures produced significantly more IL-22 than T cells activated with CD3/CD28 beads in mono-culture (Figure 1B). Moreover, we observed that DC in mono-culture did not secrete IL-22, underlining that IL-22 is produced by T cells. Furthermore, we found that IL-22 production reached maximum and plateaued out at 96 h in the DC-T cell co-cultures (Figure 1B). Consequently, we chose DC-T cell co-cultures incubated for 96 h for the following Th22 differentiation experiments.

AhR and RORγt Regulate IL-22 Production in Human Th22 Cells

Conflicting data on the role of AhR and RORγt in IL-22 production in human Th22 cells have been presented (4, 20). To determine the role of these transcription factors, we stimulated naïve CD4+ T cells with allogeneic DC in Th22 medium and increasing concentrations of the AhR antagonist CH-223191 or the RORγt antagonist SR-2211. After 96 h of culture, we measured IL-22 in the supernatant. We observed that both the AhR and the RORγt antagonist down-regulated IL-22 production (Figures 2A, B). The AhR and RORγt antagonists did not affect T cell activation or viability in the concentrations used in the present study (Supplementary Figure 2). To further explore the regulatory role of AhR on IL-22 production, we activated naïve CD4+ T cells in Th22 medium in the absence or presence of the AhR agonist FICZ and the AhR antagonist CH-223191. We found that the AhR agonist up-regulated and the AhR antagonist down-regulated IL-22 mRNA and IL-22 secretion (Figures 2C, D). Taken together, these data indicate that AhR and RORγt play key roles in the regulation of IL-22 in human Th22 cells.

Figure 2.

AhR and RORγt regulate IL-22 production in human Th22 cells. IL-22 in the supernatant of naïve CD4+ T cells co-cultured with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium and the presence of (A) the AhR antagonist CH-223191 or (B) the RORγt antagonist SR-2211 in the indicated concentrations. (mean + SEM, n = 4). (C) Relative mRNA expression and (D) IL-22 production in DC-T cell co-cultures in Th22 medium in the absence or presence of FICZ (0.3 µM) or CH-223191 (3 µM). For mRNA expression, the data are normalized to the values obtained from DC-TC co-cultures in Th22 medium in the absence of FICZ and CH-223191 (mean + SEM, one experiment with 4 donors).

1,25(OH)2D3 Inhibits IL-22 Production in Human Th22 Cells

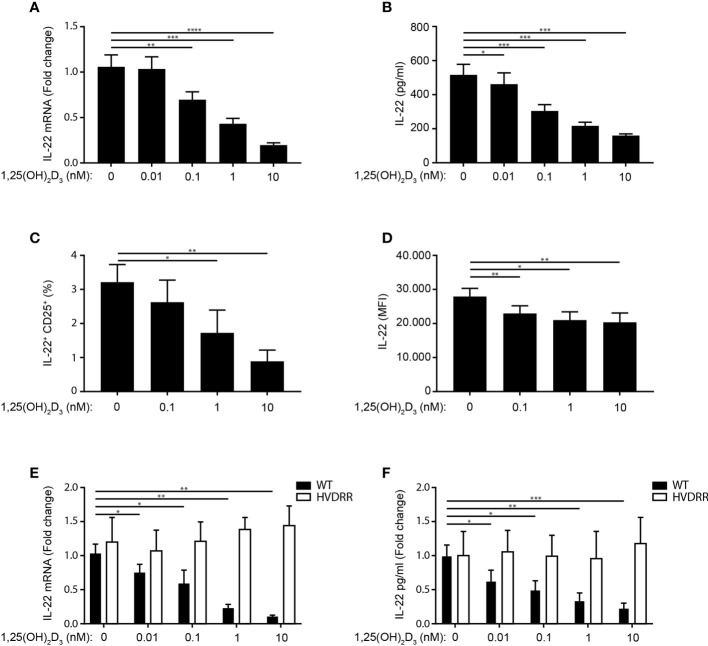

Contradictory data on the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on IL-22 production in human Th22 cells have been published (4, 42, 43). To determine the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 in Th22 cells, we activated naïve CD4+ T cells with allogeneic DC in Th22 medium in the absence or presence of 1,25(OH)2D3. After 96 h of culture, we subsequently measured IL-22 mRNA expression levels in the cells and IL-22 in the supernatant. We found that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited IL-22 mRNA expression and IL-22 secretion (Figures 3A, B). In accordance, the frequency of IL-22+ activated CD4+ T cells and their IL-22 mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) were down-regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figures 3C, D, for gating strategy please see Supplementary Figure 1A). We found that Th22 express the VDR and that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits IL-22 production in Th22 mono-cultures, supporting a direct inhibitory effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the Th22 cells (Supplementary Figure 3). Furthermore, we found that 1,25(OH)2D3 did not affect T cell activation or viability in the concentrations used in the present study (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 3.

1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits IL-22 production in human Th22 cells. (A) Relative mRNA expression (B) and production of IL-22 in naïve CD4+ T cells co-cultured with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium and the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. The data in (A) are normalized to the values obtained from DC-TC co-cultures incubated in Th22 medium in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 (mean + SEM, six independent experiments with 10 donors). (C) Frequency of IL-22+ CD25+CD4+ T cells after activation of naïve CD4+ T cells with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium and the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 (mean percentage of positive cells + SEM, three independent experiments with 5 donors). (D) Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of IL-22 in the IL22+CD25+ T cells described above (mean expression of IL-22 + SEM, three independent experiments with 5 donors). (E) Relative mRNA expression and (F) IL-22 production in naïve CD4+ T cells from healthy individuals (black) and from the HVDRR patient (white) activated with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium and the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. The data are normalized to the values obtained from CD4+ T cells activated in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 (mean + SEM, two independent experiments with 4 donors).

To establish that the inhibitory effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on IL-22 expression and production was mediated via the VDR, we determined the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on IL-22 in parallel in CD4+ T cells from controls and from a patient with hereditary vitamin D resistant rickets. This patient has a mutation in the DNA-binding domain of the VDR that abolishes the transcriptional activity of the VDR (46). Whereas 1,25(OH)2D3 clearly down-regulated IL-22 expression and production in control T cells, it had no effect on IL-22 in T cells from the patient (Figures 3E, F). Taken together, these data demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits IL-22 expression and secretion in human Th22 cells and that the 1,25(OH)2D3-induced inhibition of IL-22 is dependent on the transcriptional activity of the VDR.

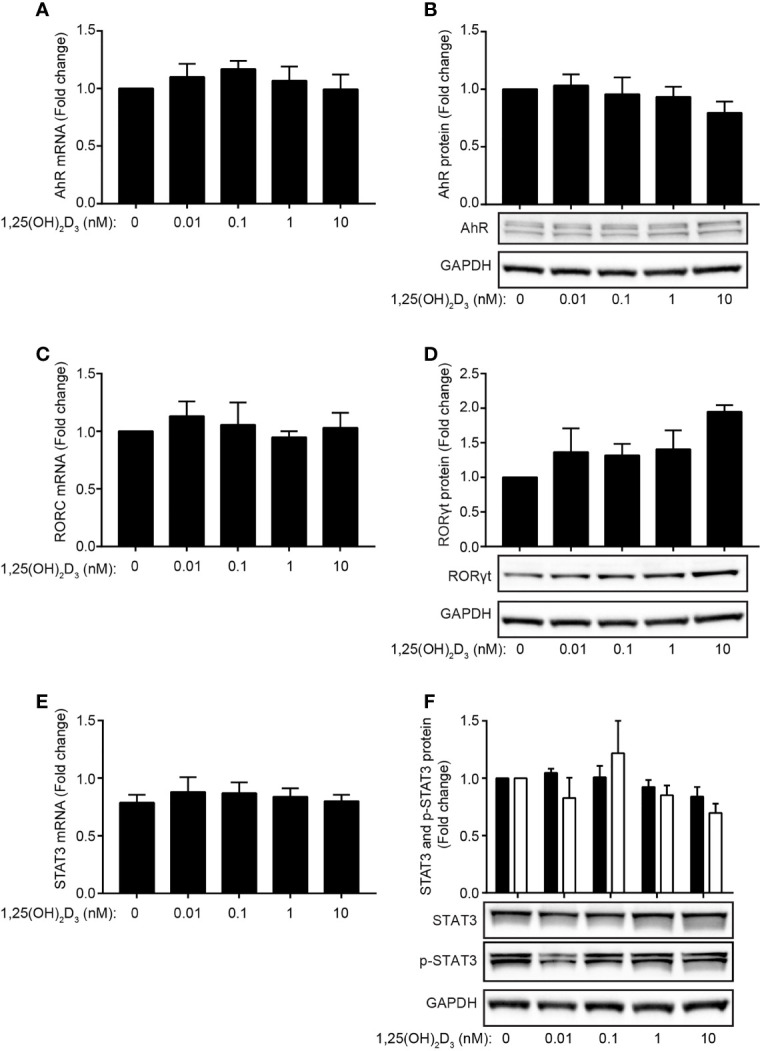

1,25(OH)2D3 Does Not Inhibit IL-22 by Affecting AhR, RORγt or STAT-3 Expression

Recently, it has been reported that the transcription factors AhR, RORγt and STAT-3 play critical roles in IL-21-mediated induction of IL-22 in mouse T cells (29). In the present study, we found that the transcription factors AhR and RORγt regulate IL-22 secretion in human Th22 cells. To investigate whether 1,25(OH)2D3 indirectly inhibits IL-22 production in human Th22 cells through down-regulation of AhR, RORγt or STAT-3, we activated naïve CD4+ T cells with allogeneic DC in Th22 medium in the absence or presence of 1,25(OH)2D3. After 96 h of culture, we determined the mRNA and protein expression levels of AhR, RORγt and STAT-3. We found that the mRNA and protein expression levels of AhR (Figures 4A, B), RORγt (Figures 4C, D) and STAT-3 (Figures 4E, F) were not significantly affected by 1,25(OH)2D3. Furthermore, 1,25(OH)2D3 did not significantly affect the phosphorylation of STAT-3 (Figure 4F). Thus, 1,25(OH)2D3 did not inhibit IL-22 expression and production by inhibition of AhR, RORγt or STAT-3 expression or STAT-3 phosphorylation in human Th22 cells.

Figure 4.

1,25(OH)2D3 does not inhibit IL-22 by affecting AhR, RORγt or STAT-3 expression. (A) Relative AhR mRNA expression and (B) representative Western Blot (lower panel) and quantification (upper panel) of AhR with GAPDH as loading control from naïve CD4+ T cells co-cultured with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium and the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. (C) Relative RORC mRNA expression and (D) representative Western Blot (lower panel) and quantification (upper panel) of RORγt with GAPDH as loading control from naïve CD4+ T cells co-cultured with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium and the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. (E) Relative STAT-3 mRNA expression and (F) representative Western Blot (lower panel) and quantification (upper panel) of STAT-3 and phosphorylated STAT-3 (p-STAT3) with GAPDH as loading control from naïve CD4+ T cells co-cultured with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium and the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. The data are normalized to the values obtained from DC-T cell co-cultures incubated in Th22 medium in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D3. (mean + SEM, two experiment with 4 donors).

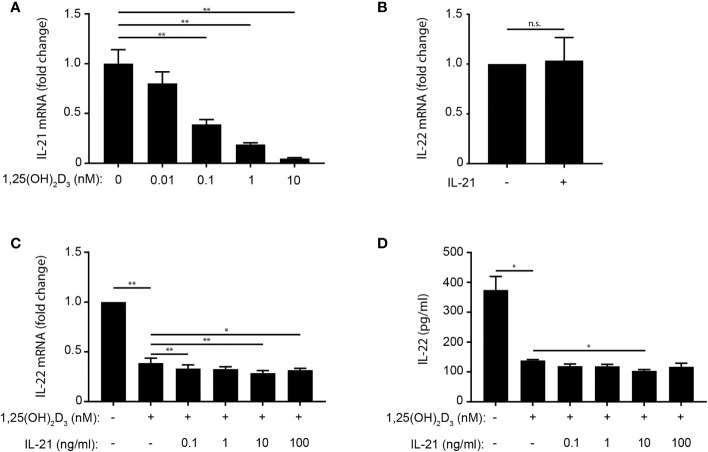

IL-21 Does Not Rescue IL-22 Production in 1,25(OH)2D3-Treated Th22 Cells

In mice, IL-21 promotes IL-22 production in CD4+ T cells (29). To investigated whether 1,25(OH)2D3 regulate IL-21 in human Th22 cells, we activated naïve CD4+ T cells in Th22 medium in the absence or presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and measured IL-21 concentration in the supernatant at day 4. We found that 1,25(OH)2D3 down-regulated IL-21 mRNA and protein expression in human Th22 cells (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 4A). Even though we did not find IL-21 to up-regulate IL-22 in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 5B), the possibility existed that 1,25(OH)2D3 indirectly inhibited IL-22 production by inhibition of IL-21. If this was the case exogenous IL-21 should rescue 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated IL-22 inhibition. Consequently, we activated naïve CD4+ T cells with allogeneic DC in Th22 medium in the absence or presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and increasing concentrations of exogenous IL-21. After 96 h of culture, we determined IL-22 mRNA expression and IL-22 secretion. We found that IL-21 did neither rescue IL-22 mRNA expression nor IL-22 secretion in Th22 cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figures 5C, D). Likewise, we found that anti-IL-21 antibodies did not inhibit IL-22 production although it strongly neutralised IL-21 in the culture supernatants (Supplementary Figures 4A, B).

Figure 5.

IL-21 does not rescue IL-22 production in 1,25(OH)2D3-treated Th22 cells. (A) Relative IL-21 mRNA expression in naïve CD4+ T cells co-cultured with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium and the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. Data are normalized to the values obtained from to DC-T cell co-cultures incubated in Th22 medium in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D3. (B) IL-22 in the supernatant of naïve CD4+ T cells activated with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium in the absence or presence of IL-21 (10 ng/ml). Data are normalized to the values obtained from to DC-T cell co-cultures incubated in Th22 medium in the absence of IL-21. (C) Relative IL-22 mRNA expression and (D) IL-22 production in naïve CD4+ T cells activated with allogeneic DC for 96 h in Th22 medium in the absence or presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 (10 nM) and the indicated concentrations of IL-21. The data in (C) are normalized to the values obtained from to DC-T cell co-cultures incubated in Th22 medium in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and IL-21. (A–D) Mean + SEM from one experiment with 4 donors. n.s., not significant.

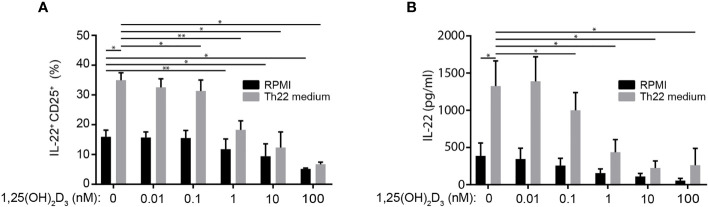

1,25(OH)2D3 Inhibits IL-22 Production in the CTCL Cell Line Myla 2059

IL-22 is highly expressed and involved in the establishment of the pro-tumorigenic environment in the skin of patients with CTCL (47). To investigate the effect of Th22 medium and 1,25(OH)2D3 on IL-22 expression in CTCL cells, we cultured the CTCL cell line Myla 2059 in the absence or presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 in RPMI in the absence or presence of the Th22 promoting factors as defined in the Th22 medium. After 48 h of culture, we measured the frequency of IL-22+ Myla 2059 cells and the IL-22 concentration in the supernatants. We found that the Th22 promoting factors significantly increased the proportion of IL-22+ Myla 2059 cells and IL-22 production (Figures 6A, B, for gating strategy please see Supplementary Figure 1B). Furthermore, we found that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited the frequency of IL-22+ Myla 2059 cells (Figures 6A and S1B). Likewise, 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited the production of IL-22 from Myla 2059 cells both in the absence and presence of Th22 promoting factors (Figure 6B). Taken together, these data showed that Th22 promoting factors increased IL-22 production in Myla 2059 cells and that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited IL-22 production in Myla 2059 cells as seen in Th22 cells.

Figure 6.

1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits IL-22 production in the CTCL cell line Myla 2059. (A) Frequency of IL-22+ Myla 2059 cell and (B) IL-22 in the supernatant of Myla 2059 cells incubation for 48 h in the absence (black columns) or presence of Th22 medium (white columns) and in the presence of the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 (mean + SEM, two independent experiments with 4 donors).

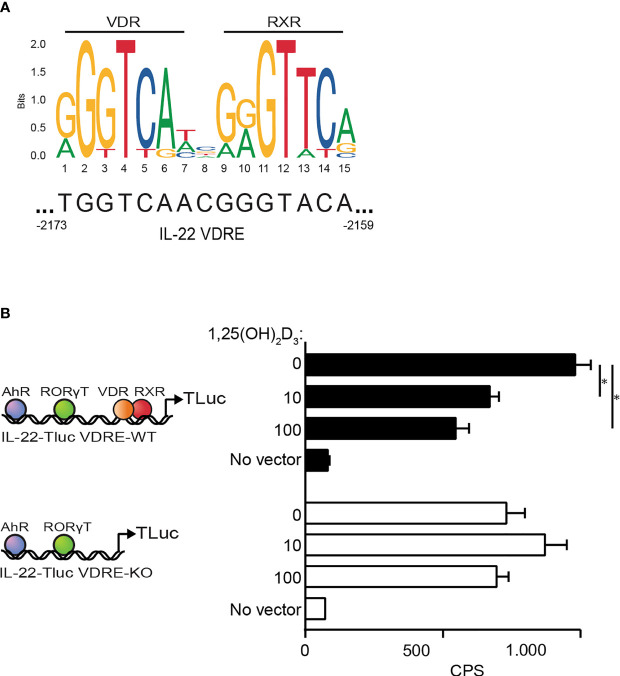

1,25(OH)2D3 Inhibits IL-22 Production via a Repressive VDRE in the il22 Promoter

The observations described above suggested that the 1,25(OH)2D3-induced repression of IL-22 transcription was not indirectly mediated by inhibition of transcription factors but was a direct effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the il22 gene. Consequently, we searched for potential VDRE in the il22 promoter using the JASPAR database of transcription factor binding profiles (48). We found a potential VDRE sequence in the il22 promoter located 2159-2173 base pairs upstream from the start codon of the il22 gene (Figure 7A). To determine whether this sequence actually represented a repressive VDRE, we constructed two reporter vectors where luciferase expression was dependent on the il22 promoter. One of the vectors contained the wild-type il22 promoter sequence including the putative VDRE (IL22-TLuc VDRE-WT) and the other vector contained the il22 promoter sequence where the putative VDRE was deleted (IL22-TLuc VDRE-KO) (Figure 7B). We transfected Myla 2059 cells with the vectors and compared luciferase light emission in untreated cells and in cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3. We found that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited luciferase light emission in Myla 2059 cells transfected with the IL22-TLuc VDRE-WT vector but not in Myla 2059 cells transfected with the IL22-TLuc VDRE-KO vector (Figure 7B). These data indicated that the il22 promoter contains a repressive VDRE located 2159-2173 base pairs upstream from the start codon of the il22 gene.

Figure 7.

1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits IL-22 production via a repressive VDRE in the il22 promoter (A) Schematic representation of the transcription factor VDR : RXR and the DNA binding consensus motif as position frequency matrices for VDR : RXR in homo sapiens found in the open-access database JASPAR (48, 49). (B) (Left) Schematic representation of the plasmid construct IL-22-Tluc with the VDRE (IL-22-TLuc VDRE-WT) located at 2159-2173 base pairs upstream the start site of the il22 gene and the plasmid construct IL-22-Tluc with the VDRE deletion (IL-22-TLuc VDRE-KO). (Right) Luciferase light emission in counts per second (CPS) in Myla 2059 cells nucleofected either with IL-22-TLuc VDRE-WT (black) or IL-22-TLuc VDRE-KO (white) plasmids and cultured for 48 h in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3 at the indicated concentrations in nM (mean + SEM, three independent experiments).

Discussion

In this study, we show that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits IL-22 expression and production in human Th22 cells through a repressive VDRE in the il22 promoter. 1,25(OH)2D3 is well-known by its immunomodulatory properties and it can influence the differentiation of T helper cells by regulating the production of their signature cytokine (35–41). Some studies have investigated the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on IL-22 in human and mice CD4+ T cells (4, 42, 43). However, conflicting results were obtained. One study found that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited IL-22 production in human Th17 cells (43), whereas others found that 1,25(OH)2D3 promoted Th22 cell differentiation and IL-22 production (4, 42). Thus, the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on IL-22 in human Th22 cells remained to be fully elucidated. In the present study we demonstrate that 1,25(OH)2D3 strongly inhibited IL-22 production in Th22 cells. This was not caused by 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated inhibition of the expression of the transcription factors AhR, RORγt and STAT-3 or by the inhibition of IL-21 production. Although we did not formally rule out that 1,25(OH)2D3 might affect the binding of those transcription factors to target genes, we show that 1,25(OH)2D3 directly inhibits IL-22 production through a repressive VDRE located in the il22 promoter. This is in line with previous studies that identified repressive VDRE in the ifng (50) and il12B (51) promoters.

In the present study, we describe a novel way to differentiate human Th22 cells in vitro. In our system, where we activate naïve CD4+ T cells with allogeneic dendritic cells, the sole presence of IL-6 and TNFα did not increase IL-22 production. However, we found that IL-6, TNFα, IL-1β and IL-23 lead to an increase in both IL-22 and IL-17 production. This is in accordance to previous studies that found that these factors increase IL-17 production in CD4+ T cells (52–54). As the AhR agonist FICZ has been found to induce IL-22 and inhibit IL-17, we included FICZ in the Th22 panel. We observed that FICZ lead to increased IL-22 production while down-regulating IL-17. However, IL-17 was still produced to some extent in the presence of FICZ. A key cytokine in the differentiation of Th17 cells is TGFβ (55–57). Thus, we included an inhibitor of TGFβR signalling (galunisertib) in an attempt to repress the generation of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells in the presence of factors that induce IL-22 production. Interestingly, we found that galunisertib augmented the production of IL-22 while inhibiting IL-17 production. Taken together, we found that the combination of IL-6, TNFα, IL-1β, IL-23, FICZ and galunisertib constituted optimal conditions for in vitro generation of human Th22 cells.

We found that AhR and RORγt are important transcription factors that regulate IL-22 in human Th22 cells. In accordance, AhR and RORγt regulate IL-22 expression and production in ILC3 that represent a major IL-22 source in the gut (58, 59). In contrast to a recent study that identified IL-21 as an inducer of IL-22 production in mouse CD4+ T cells (29), we found that IL-21 do not affect IL-22 production in human Th22 cells. Thus, our data suggest that regulation of IL-22 may differ between mice and human CD4+ T cells.

Interestingly, ectopic IL-22 expression is a characteristic feature of lesional skin in CTCL, and IL-22 is believed to play a role in the establishment of the pro-tumorigenic microenvironment and the deficient antimicrobial defence in these patients (47, 60). Of notice, CTCL lesions are often localized to body areas, which are not exposed to sunlight i.e. the “bathing suit area” and in general, CTCL patients display deficient vitamin D serum levels (49). Given the present findings that vitamin D inhibit IL-22 expression in malignant T cells, we hypothesize that vitamin D supplementation could have a beneficial effect as adjuvant therapy inhibiting ectopic IL-22 expression and skin inflammation in CTCL.

In conclusion, we have identified a novel way of differentiating naïve CD4+ T cells towards the Th22 lineage and demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D3 directly inhibits IL-22 through VDR targeting a repressive VDRE located in the il22 gene. We showed that AhR and RORγt regulate IL-22 in human Th22 cells, whereas IL-21 does not affect IL-22 production in human Th22 cells. This study add to the understanding on IL-22 regulation in human Th22 cells and suggests that vitamin D may be considered a potential therapeutics to regulate IL-22-mediated diseases.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Regional Ethical Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CG, MK-W and DL conceived the study and designed the experiments. DL, FA-J, ND, UP and ST performed the laboratory experiments. CB, BW, AW and NØ assisted with the experimental design and data interpretation. CG, MK-W and DL analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the LEO Foundation (LF17058).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.715059/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of Effector CD4 T Cell Populations. Annu Rev Immunol (2010) 28:445–89. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu J. T Helper Cell Differentiation, Heterogeneity, and Plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2018) 10:a030338. 10.1101/cshperspect.a030338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Pennino D, Carbone T, Nasorri F, Pallotta S, et al. Th22 Cells Represent a Distinct Human T Cell Subset Involved in Epidermal Immunity and Remodeling. J Clin Invest (2009) 119:3573–85. 10.1172/JCI40202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duhen T, Geiger R, Jarrossay D, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Production of Interleukin 22 But Not Interleukin 17 by a Subset of Human Skin-Homing Memory T Cells. Nat Immunol (2009) 10:857–63. 10.1038/ni.1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolk K, Witte E, Witte K, Warszawska K, Sabat R. Biology of Interleukin-22. Semin Immunopathol (2010) 32:17–31. 10.1007/s00281-009-0188-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolk K, Sabat R. Interleukin-22: A Novel T- and NK-Cell Derived Cytokine That Regulates the Biology of Tissue Cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2006) 17:367–80. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolk K, Kunz S, Witte E, Friedrich M, Asadullah K, Sabat R. IL-22 Increases the Innate Immunity of Tissues. Immunity (2004) 21:241–54. 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolk K, Witte E, Wallace E, Döcke WD, Kunz S, Asadullah K, et al. IL-22 Regulates the Expression of Genes Responsible for Antimicrobial Defense, Celular Differentiation and Mobility in Keratinocytes: A Potential Role in Psoriasis. Eur J Immunol (2006) 36:1309. 10.1002/eji.200535503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pham TA, Clare S, Goulding D, Arasteh JM, Stares MD, Browne HP, et al. Epithelial IL-22RA1-Mediated Fucosylation Promotes Intestinal Colonization Resistance to an Opportunistic Pathogen. Cell Host Microbe (2014) 16:504–16. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang SC, Tan XY, Luxenberg DP, Karim R, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Collins M, et al. Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 Are Coexpressed by Th17 Cells and Cooperatively Enhance Expression of Antimicrobial Peptides. J Exp Med (2006) 203:2271–9. 10.1084/jem.20061308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindemans CA, Calafiore M, Mertelsmann AM, O'Connor MH, Dudakov JA, Jenq RR, et al. Interleukin-22 Promotes Intestinal Stem Cell-Mediated Epithelial Re-Generation. Nature (2016) 528:560–4. 10.1038/nature16460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boniface K, Bernard FX, Garcia M, Gurney AL, Lecron JC, Morel F. IL-22 Inhibits Epidermal Differentiation and Induces Proinflammatory Gene Expression and Migration of Human Keratinocytes. J Immunol (2005) 174:3695–702. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nograles KE, Zaba LC, Guttman-Yassky E, Fuentes-Duculan J, Suárez-Fariñas M, Cardinale I, et al. Th17 Cytokines Interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-22 Modulate Distinct Inflammatory and Keratinocyte-Response Pathways. Br J Dermatol (2008) 159(5):1092–102. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08769.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn K, Kim BE, Kim J, Leung DY. Recent Advances in Atopic Dermatitis. Curr Opin Immunol (2020) 66:14–21. 10.1016/j.coi.2020.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin M, Yoon J. From Bench to Clinic: The Potential of Therapeutic Targeting of the IL-22 Signaling Pathway in Atopic Dermatitis. Immune Netw (2018) 18:e42. 10.4110/in.2018.18.e42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eberle FC, Bruck J, Holstein J, Hirahara K, Ghoreschi K. Recent Advances in Understanding Psoriasis. F1000Res (2016) 5:F1000. 10.12688/f1000research.7927.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui G. TH9, TH17, and TH22 Cell Subsets and Their Main Cytokine Products in the Pathogenesis of Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol (2019) 9:1002. 10.3389/fonc.2019.01002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doulabi H, Rastin M, Shabahangh H, Maddah G, Abdollahi A, Nosratabadi R, et al. Analysis of Th22, Th17 and CD4+cells Co-Producing IL-17/IL-22 at Different Stages of Human Colon Cancer. BioMed Pharmacother (2018) 103:1101–6. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen E, Wang M, Xie H, Zou R, Lin Q, Lai L, et al. Existence of Th22 in Children and Evaluation of IL-22 + CD4 + T, Th17, and Other T Cell Effector Subsets From Healthy Children Compared to Adults. BMC Immunol (2016) 17:20. 10.1186/s12865-016-0158-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trifari S, Kaplan CD, Tran EH, Crellin NK, Spits H. Identification of a Human Helper T Cell Population That Has Abundant Production of Interleukin 22 and Is Distinct From TH-17, TH1 and TH2 Cells. Nat Immunol (2009) 10:864–71. 10.1038/ni.1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plank MW, Kaiko GE, Maltby S, Weaver J, Tay HL, Shen W, et al. Th22 Cells Form a Distinct Th Lineage From Th17 Cells In Vitro With Unique Transcriptional Properties and Tbet-Dependent Th1 Plasticity. J Immunol (2017) 198:2182–90. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kara EE, Comerford I, Fenix KA, Bastow CR, Gregor CE, McKenzie DR, et al. Tailored Immune Responses: Novel Effector Helper T Cell Subsets in Protective Immunity. PloS Pathog (2014) 10:e1003905. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolk K, Kunz S, Asadullah K, Sabat R. Cutting Edge: Immune Cells as Sources and Targets of the IL-10 Family Members? J Immunol (2002) 168:5397–402. 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witte E, Witte K, Warszawska K, Sabat R, Wolk K. Interleukin-22: A Cytokine Produced by T, NK and NKT Cell Subsets, With Importance in the Innate Immune Defense and Tissue Protection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2010) 21:365–79. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu J, Heller JJ, Guo X, Chen ZM, Fish K, Fu YX, et al. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Regulates Gut Immunity Through Modulation of Innate Lymphoid Cells. Immunity (2012) 36:92–104. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cording S, Medvedovic J, Cherrier M, Eberl G. Development and Regulation of RORγt+ Innate Lymphoid Cells. FEBS Lett (2014) 588:4176–81. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hazenberg MD, Spits H. Human Innate Lymphoid Cells. Blood (2014) 124:700–9. 10.1182/blood-2013-11-427781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanos SL, Bui VL, Mortha A, Oberle K, Heners C, Johner C, et al. RORgammat and Commensal Microflora Are Required for the Differentiation of Mucosal Interleukin 22-Producing NKp46+ Cells. Nat Immunol (2009) 10:83–91. 10.1038/ni.1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeste A, Mascanfroni ID, Nadeau M, Burns EJ, Tukpah AM, Santiago A, et al. IL-21 Induces IL-22 Production in CD4+ T Cells. Nat Commun (2014) 5:3753. 10.1038/ncomms4753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pike JW, Meyer MB, Bishop KA. Regulation of Target Gene Expression by the Vitamin D Receptor - an Update on Mechanisms. Rev Endocr Metab Disord (2012) 13:45–55. 10.1007/s11154-011-9198-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Kaneko I, Haussler CA, Hsieh D, Hsieh JC, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Vitamin D Action. Calcif Tissue Int (2013) 92:77–98. 10.1007/s00223-012-9619-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Haussler CA, Hsieh JC, Thompson PD, Selznick SH, et al. The Nuclear Vitamin D Receptor: Biological and Molecular Regulatory Properties Revealed. In: Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. The Official Journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; (1998) 13(3):325–49. 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.3.325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jurutka PW, Hsieh J-C, Remus LS, Whitfield GK, Thompson PD, Haussler CA, et al. Mutations in the 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Receptor Identifying C-Terminal Amino Acids Required for Transcriptional Activation That Are Functionally Dissociated From Hormone Binding, Heterodimeric DNA Binding and Interaction With Basal Transcription Factor IIB, In Vitro. J Biol Chem (1997) 272:14592–9. 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson PD, Remus LS, Hsieh J-C, Jurutka PW, Whitfield GK, Galligan MA, et al. Distinct Retinoid X Receptor Activation Function-2 Residues Mediate Transactivation in Homodimeric and Vitamin D Receptor Heterodimeric Contexts. J Mol Endocrinol (2001) 27:211–27. 10.1677/jme.0.0270211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams JS, Rafison B, Witzel S, Reyes RE, Shieh A, Chun R, et al. Regulation of the Extrarenal CYP27B1-Hydroxylase. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (2014) 144:22–7. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagpal S, Na S, Rathnachalam R. Noncalcemic Actions of Vitamin D Receptor Ligands. Endocr Rev (2005) 26:662–87. 10.1210/er.2004-0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kongsbak M, von Essen MR, Boding L, Levring TB, Schjerling P, Lauritsen JP, et al. Vitamin D Up-Regulates the Vitamin D Receptor by Protecting it From Proteasomal Degradation in Human CD4+ T Cells. PloS One (2014) 9:e96695. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rigby WF, Yirinec B, Oldershaw RL, Fanger MW. Comparison of the Effects of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 on T Lymphocyte Subpopulations. Eur J Immunol (1987) 17:563–6. 10.1002/eji.1830170420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeffery LE, Burke F, Mura M, Zheng Y, Qureshi OS, Hewison M, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and IL-2 Combine to Inhibit T Cell Production of Inflammatory Cytokines and Promote Development of Regulatory T Cells Expressing CTLA-4 and FoxP3. J Immunol (2009) 183:5458–67. 10.4049/jimmunol.0803217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Etten E, Mathieu C. Immunoregulation by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3: Basic Concepts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (2005) 97:93–101. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer MT, Lee YK, Maynard CL, Oliver JR, Bikle DD, Jetten AM, et al. Lineage-Specific Effects of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) on the Development of Effector CD4 T Cells. J Biol Chem (2011) 286:997–1004. 10.1074/jbc.M110.163790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sommer A, Fabri M. Vitamin D Regulates Cytokine Patterns Secreted by Dendritic Cells to Promote Differentiation of IL-22-Producing T Cells. PloS One (2015) 10:e0130395. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lovato P, Norsgaard H, Tokura Y, Røpke MA. Calcipotriol and Betamethasone Dipropionate Exert Additive Inhibitory Effects on the Cytokine Expression of Inflammatory Dendritic Cell-Th17 Cell Axis in Psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci (2017) 85:147. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woetmann A, Lovato P, Eriksen KW, Krejsgaard T, Labuda T, Zhang Q, et al. Nonmalignant T Cells Stimulate Growth of T-Cell Lymphoma Cells in the Presence of Bacterial Toxins. Blood (2007) 109:3325–32. 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Available at: http://jaspar.genereg.net/matrix/MA0074.1/.

- 46.Al-Jaberi FAH, Kongsbak-Wismann M, Aguayo-Orozco A, Krogh N, Buss T, Lopez DV, et al. Impaired Vitamin D Signaling in T Cells From a Family With Hereditary Vitamin D Resistant Rickets. Front Immunol (2021) 12:684015. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.684015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyagaki T, Sugaya M, Suga H, Kamata M, Ohmatsu H, Fujita H, et al. IL-22, But Not IL-17, Dominant Environment in Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res (2011) 17:7529–38. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fornes O, Castro-Mondragon JA, Khan A, van der Lee R, Zhang X, Richmond PA, et al. JASPAR 2020: Update of the Open-Access Database of Transcription Factor Binding Profiles. Nucleic Acids Res (2020) 48:D87–92. 10.1093/nar/gkz1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Talpur R, Cox KM, Hu M, Geddes ER, Parker MK, Yang BY, et al. Vitamin D Deficiency in Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome Patients Is Similar to Other Cancer Patients. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk (2014) 14(6):518–24. 10.1016/j.clml.2014.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cippitelli M, Santoni A. Vitamin D3: A Transcriptional Modulator of the Interferon-Gamma Gene. Eur J Immunol (1998) 28:3017–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gynther P, Toropainen S, Matilainen JH, Seuter S, Carlberg C, Väisänen S, et al. Mechanism of 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-Dependent Repression of Interleu-Kin-12B. Biochim Biophys Acta (2011) 1813:810–8. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chung Y, Chang SH, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Nurieva R, Kang HS, et al. Critical Regulation of Early Th17 Cell Differentiation by Interleukin-1 Signaling. Immunity (2009) 30:576–87. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sutton C, Brereton C, Keogh B, Mills KH, Lavelle EC. A Crucial Role for Interleukin (IL)-1 in the Induction of IL-17-Producing T Cells That Mediate Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med (2006) 203:1685–91. 10.1084/jem.20060285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, et al. The Orphan Nuclear Receptor RORgammat Directs the Differentiation Program of Proinflammatory IL-17+ T Helper Cells. Cell (2006) 126:1121–33. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O’Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO, et al. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Induces Development of the T(H)17 Lineage. Nature (2006) 441:231–4. 10.1038/nature04754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the Context of an Inflammatory Cytokine Milieu Supports De Novo Differentiation of IL-17-Producing T Cells. Immunity (2006) 24:179–89. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morishima N, Mizoguchi I, Takeda K, Mizuguchi J, Yoshimoto T. TGF-Beta Is Necessary for Induction of IL-23R and Th17 Differentiation by IL-6 and IL-23. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2009) 386:105–10. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee JS, Cella M, McDonald KG, Garlanda C, Kennedy GD, Nukaya M, et al. AHR Drives the Development of Gut ILC22 Cells and Postnatal Lymphoid Tissues Via Pathways Dependent on and Independent of Notch. Nat Immunol (2011) 13:144–51. 10.1038/ni.2187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tripathi D, Radhakrishnan RK, Sivangala Thandi R, Paidipally P, Devalraju KP, Neela VSK, et al. IL-22 Produced by Type 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILC3s) Reduces the Mortality of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) Mice Infected With Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. PloS Pathog (2019) 15:e1008140. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Papathemeli D, Patsatsi A, Papanastassiou D, Koletsa T, Papathemelis T, Avgeros C, et al. Protein and mRNA Expression Levels of Interleukin-17A, -17F and -22 in Blood and Skin Samples of Patients With Mycosis Fungoides. Acta Derm Venereol (2020) 100(18):adv00326. 10.2340/00015555-3688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.