Abstract

Background

Computer-based learning (CBL) is considered by many to be an effective means of education. However, features of computer-based modules purported to contribute to learning have not been studied with medical student education.

Objective

This study was designed to evaluate the effect of auditory supplements in a computer-based instructional module on learning and knowledge retention.

Design

A prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of two types of web-based instructional presentations used to teach key aspects of systems-based practice to fourth-year medical students.

Intervention

The intervention and control group each received a computer-based module comprised of the same mix of visual and written material, but the intervention group also received an auditory narration of the materials.

Main Measures

The primary outcome measures were the difference in the students’ scores between the two modules using an online 8-item knowledge test completed immediately after the first exposure to the module and again 1 to 7 months later. Students were also asked whether they considered themselves auditory learners. Learning efficiency (the amount of learning per unit time) was calculated for each student and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare scores between the two groups.

Results

One hundred thirty fourth-year medical students were randomized by a computer program to one of the two modules. All students completed the first knowledge test and 86 (66%) students completed the second test. Test scores did not differ significantly between the two groups in either the first or the second test. Learning efficiency was lower in the intervention group. Self-identification as auditory learners had no effect on performance.

Conclusions

The addition of narration to a computer-based instructional module did not improve learning or knowledge retention even in students who self-identified as auditory learners and resulted in overall lower learning efficiency.

Keywords: Computer-based learning, Systems-based practice, Education

Introduction

Computer-based learning (CBL) is an effective tool to enhance medical education. Though research has demonstrated that CBL can be effective, there is little information on which type of CBL is optimal [1–3].

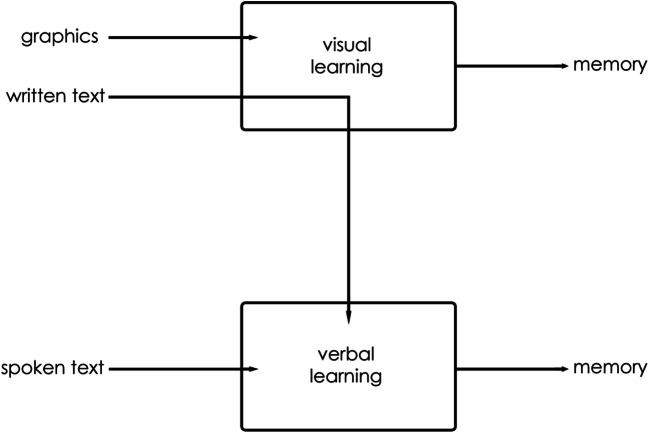

The cognitive theory of learning states that information can pass through two channels, the visual and verbal learning channels, before being committed to memory (Fig. 1). Both channels have a limited capacity. In presentations with visual graphics, learning may be more effective when content is presented verbally rather than visually because visually presented text can overload the visual learning channel [4, 5]. The design of computer-based presentations must take into account cognitive learning theory to use the correct balance of visual and verbal stimuli to maximize learning.

Fig. 1.

Mayers cognitive theory of multimedia learning

Fleming’s theory of learning suggested that people learnt in different ways, either visual, auditory, read/write, or kinesthetic learners [6]. Matching learning to the format that matches a learner’s style should enhance learning; however, studies that evaluate this have not upheld this theory [7–9]. Medical students may express a desire for content delivered in what they perceive to be their preferred method of learning but this may or may not lead to improved learning.

As medical schools increasingly replace traditional large group lectures with online learning and invest in educational technology, it would be optimal to develop an evidence-base from which to determine the most effective learning approaches. The Association of American Medical Colleges’ Institute for Improving Medical Education report recommends the use of multimedia learning principles in the design of presentations for medical students using only features that advance learning and avoiding features that may hinder learning [10]. Many computer-based modules are based on the presentation of slides comprising written and visual material [5].

Whether the addition of an audio stimulus to the visual learning environment changes learning acquisition or retention is not known in medical education. The goal of this study is to evaluate the effect of an auditory narrative on learning and knowledge retention. In addition, we wanted to determine if students who identified themselves as auditory learners had greater learning and knowledge retention in the presentation with narration than students who identified themselves as non-auditory learners. We also measured learning efficiency to determine whether any learning benefit correlated with greater time spent in the learning activity.

Methods

Curriculum

Kerfoot demonstrated that the concepts of systems-based practice (SBP) could effectively be taught to medical students and residents through online learning modules [11]. Our study was conducted within a required fourth-year SBP curriculum.

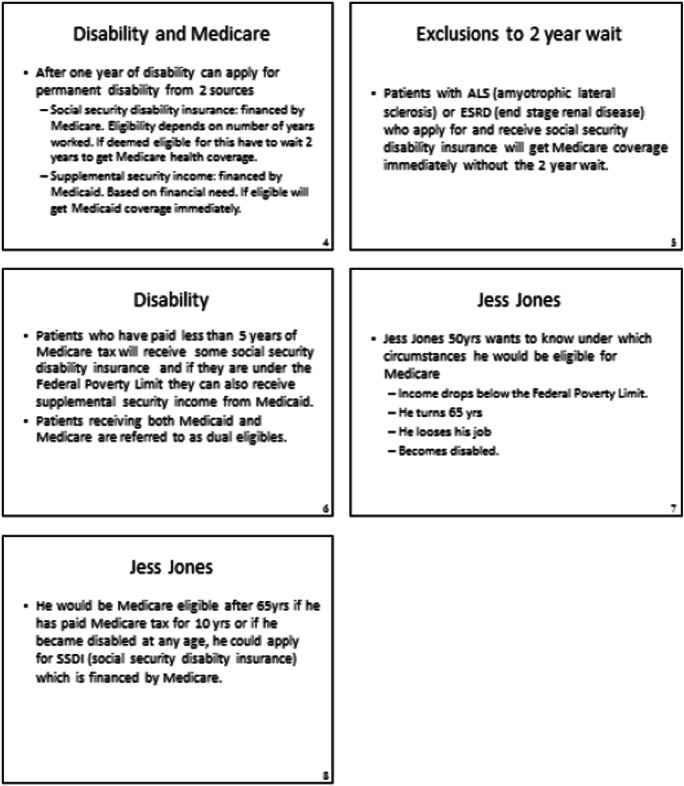

During their orientation day for the selective, students were required to take a self-paced online PowerPoint module covering key aspects of Medicare developed by the investigators. The module comprised fifty-five slides, predominantly text, of factual information and questions with answers (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Sample slides from an online PowerPoint presentation on Medicare

Population, Recruitment, and Randomization

This was a randomized controlled study of two identical online PowerPoint presentations, one with narration and one without. The subjects were all fourth-year medical students in the 2011–2012 academic year at a state university medical school completing a required 4-week selective on systems-based practice between September 2011 and March 2012. The setting for the study was in an auditorium in the Family Medicine Center.

The learning module asked students to report selected personal characteristics and then randomly allocated each student to one of two versions of the module, one with narration one without. On completion of the presentation, the module recorded the amount of time spent in the presentation and administered an eight-item multiple-choice knowledge quiz. The same knowledge quiz was administered again at the end of the academic year, approximately 1–7 months later, to test long-term knowledge retention. Students were not given the correct answers after taking the initial quiz. The randomized post-test only design was used as this is superior to the pre-test–post-test design in that it avoids testing threats such as studying for the test [12].

The students were only able to access the module and the test as determined by the study protocol. They were unaware they were in the study but were able to see that some students used head phones to complete the online module. The data was analyzed by investigators blinded to the group assignments. The study design and protocol were deemed exempt by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Development of the Test Instrument

A 15-item multiple-choice test was developed that covered the aspects of Medicare presented in the module. Content validity was established by six physicians. Reliability of the instrument was tested in 2 pilot studies with 35 medical students and residents. An index of discrimination was computed for each item as the difference between the proportion of students scoring above the median and those scoring below the median who answered the item correctly [13]. Seven items whose discrimination index was 0.10 or less were dropped, leaving 8 items.

Outcome and Indicator Variables

The primary outcome measures were the number of correct responses on the 8-item knowledge test completed immediately after the module and again at the end of the academic year. A secondary outcome was learning efficiency (the amount of learning per unit of time), calculated as the number of correct responses divided by the number of minutes spent in the online module [14]. Other variables included students’ gender, age, ethnicity, and degree program (MD only or combined MD-MPH or MD-PhD); self-reported auditory learner status (yes, no, unsure); years of post-graduate training prior to medical school (0; 1; 2–4; > 4); and prior experience with computer-based learning (none; 1–3 courses; > 3 courses).

Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess variables’ normality of distribution. Based on those results, the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare means between the two groups; Chi-square was used to compare proportions. Based on scores of participating students, a total sample of 60 (30 in each group) would be sufficient to detect a one-item difference in scores at the 0.05 significance level with power of 80%.

Results

Over the course of the 2011–2012 academic year, 130 medical students were randomized to receive one of two online information modules on Medicare. Students were allocated as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Allocation of study participants

The study sample of 130 had a mean age of 28 years and was evenly divided by gender (49% female). One-third of students were in a dual-degree program (16% MD-MPH; 11% MD-PhD); 31% reported two or more years of post-graduate education prior to medical school. Two-thirds of students reported prior experience with web-based learning. Twenty-three percent self-identified as auditory learners; 28% were unsure. There were more students in the module with narration who had experience with online learning courses; otherwise, the groups were evenly balanced (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participating students by intervention group

| Demographics | Module without narration | Module with narration | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| N = 130 | 65 | 55% | 65 | 55% | |

| Mean age (S.D.) | 28.6 | 3.13 | 27.7 | 2.29 | 0.131 |

| Gender: Female | 29 | 45% | 37 | 57% | 0.160 |

| Male | 36 | 55% | 28 | 43% | |

| Degree Program: MD | 46 | 71% | 47 | 72% | 0.350 |

| MD-MPH | 9 | 14% | 12 | 18% | |

| MD-PhD | 10 | 15% | 5 | 8% | |

| Self-identified auditory learner: Yes | 15 | 23% | 15 | 23% | 0.114 |

| No | 37 | 57% | 27 | 42% | |

| Unsure | 13 | 20% | 23 | 35% | |

| Prior experience with online courses: None | 17 | 26% | 30 | 46% | 0.048 |

| 1–3 courses | 25 | 38% | 19 | 29% | |

| > 3 courses | 23 | 35% | 15 | 23% | |

| Years of prior post-graduate training: 0 | 36 | 55% | 43 | 66% | 0.265 |

| 1 | 4 | 6% | 7 | 11% | |

| 2–4 | 16 | 25% | 10 | 15% | |

| > 4 | 9 | 14% | 5 | 8% | |

*Tests of differences between intervention groups (Mann-Whitney U test for age, χ2 test of independence for other variables)

Table 2 shows the scores for the knowledge quiz given immediately following the module, for the groups with and without narration. There was no significant difference between the scores of the students in the two groups. Overall study time ranged from 2 to 46 min, averaging 20 min. Students doing the module without narration spent on average 4 min less in study time. The correct responses per minute of study for the group with and without narration were 1.24 versus 1.8, respectively (p = 0.0002), yielding significantly greater learning efficiency in the group without narration.

Table 2.

Quiz scores immediately following exposure to the learning module

| Knowledge quiz, time 1 | Module without narration | Module with narration | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (S.D.) | n | (S.D.) | ||

| N = 130 (%) | 65 | 55% | 65 | 55% | |

| Mean number correct responses (S.D.) | 6.8 | 1.03 | 6.4 | 1.28 | 0.052 |

| Mean minutes of study (S.D.) | 16.8 | 8.49 | 20.1 | 8.80 | 0.001 |

| Mean learning efficiency† (S.D.) | 1.24 | 5.20 | 1.77 | 7.79 | 0.0002 |

*Mann-Whitney U test of differences between intervention groups

†Calculated as the number of correct responses per minute of study

In the students who took the module with narration, there was no significant difference between the scores of students who self-identified as auditory learners and the scores of students who did not identify as auditory learners. Students unsure of their learning style were excluded from this analysis. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Quiz scores of auditory learners versus non-auditory learners (excludes “unsure”) for students allocated to the module with narration

| Knowledge quiz, time 1 | Non-auditory learners | Auditory learners | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (S.D.) | n | (S.D.) | ||

| N = 42 (%) | 27 | 68% | 15 | 38% | |

| Mean number correct responses (S.D.) | 6.6 | 1.19 | 6.4 | 1.30 | 0.646 |

| Mean minutes of study (S.D.) | 18.5 | 7.26 | 23.0 | 5.13 | 0.081 |

| Mean learning efficiency† (S.D.) | 2.77 | 11.50 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.051 |

*Mann-Whitney U test of differences between intervention groups

†Calculated as the number of correct responses per minute of study

On the second knowledge quiz at the end of the year, most students responded correctly on less than half the questions, with no significant difference between the two groups (Table 4). The difference in learning efficiency as measured by correct responses per minute spent in the module between the two groups had disappeared.

Table 4.

Quiz scores between groups at the end of the academic year

| Knowledge quiz, time 2 | Module without narration | Module with narration | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (S.D.) | n | (S.D.) | ||

| N = 86 (66%) | 38 | 44% | 48 | 56% | |

| Mean number correct responses | 3.0 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 0.200 |

| Mean minutes of study | 17.5 | 8.2 | 18.4 | 8.2 | 0.080 |

| Mean learning efficiency† | 0.6 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 9.1 | 0.025 |

| Mean months between exposure and quiz | 4.7 | 2.0 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 0.280 |

*Mann-Whitney U test of differences between intervention groups

†Calculated as the number of correct responses per minute of study

Discussion

Learning was not improved by the addition of narration to a PowerPoint presentation. These results support the dual channel theory of learning which hypothesizes that information is processed through two channels, one for verbal (which can be written or auditory) and a second visual or non-verbal channel (Fig. 1) [5]. Each channel has a limited capacity to manage information and overloading that capacity, as was possible in the group that had the slides with narration does not increase learning and can decrease information retention. Mayer calls this the principle of redundancy: presenting text visually and by narration is redundant as both are processed by the same cognitive channel, in this case, the verbal channel.

Learning could be improved if other information such as graphics were presented which would be processed through the visual learning channel and so reinforce learning. In a multimedia presentation, learning is improved when words are spoken leaving the visual learning channel free for graphics because written text has to be processed through the visual learning channel prior to passing into the verbal channel. Mayer supported this dual channel processing theory with 17 studies comparing presentations with graphics and narration versus graphics and on screen text. In all 17 studies, students learned better from graphics combined with narration, whereby both learning channels were engaged [5].

The learning preferences hypothesis suggests that adapting educational strategies to students learning style should improve learning. Our study, like previous studies, does not support this hypothesis because students who self-identified as auditory learners and were randomized to the presentation with narration did no better on the knowledge quiz than the students who identified themselves as auditory learners and had the presentation without narration. This outcome is consistent with the above principle of redundancy, whereby presenting the same information in 2 formats is redundant.

A previous smaller study completed at 2 different sites evaluated the effect of narration versus no narration in an online lecture and found conflicting outcomes with improved learning at one site (n = 33) and equivalent learning at the second site (n = 26) [15]. The composite result found a trend to improved learning with narration, but the module with narration took significantly longer and it is unclear whether the narration elaborated on the slide content.

Wiebe et al. compared two PowerPoint presentations in use by elementary school science teachers: one with narration that elaborated on the text and the second without narration [16]. He found that although the post-test scores favored the PowerPoint with narration, the difference was not statistically significant [16]. He analyzed eye tracking to measure eye contact with the slide and found that once the group had read the slide content, they lost interest in the narration providing an additional explanation to support the redundancy theory as to why learning was not enhanced by narration of the text. To avoid the confounding effect of elaboration of the text, in our study, the voice-over narration simply replicated, in a conversational tone, the text on the slide with no elaboration.

A less popular theory of learning is the information delivery theory which hypothesizes that the amount of learning correlates with the volume of information delivered to the learner, so information delivered in as many modalities as possible will improve learning [5]. The results of this study conflict with this theory as additional information via narration did not improve learning.

The advantage of an audio-free presentation allows students to progress through the material at their own rate, spending more or less time as needed. The learning efficiency for the PowerPoint without narration was greatest as students went through the presentation more quickly but not at the expense of worse outcomes on the knowledge quiz. Although we did not assess students’ preferences, Marchevsky found that medical students doing a web-based pathology course did not like using the headsets preferring to read than listen to the narrative [16]. Reading also allows the students to assimilate information at their own pace rather than at the pace of the presenter [17].

Limitations to this study include the lack of blinding in the students who could see who were wearing headsets and had a narrative presentation. However, the students were unaware that this was an educational study so it is unlikely that this affected their performances on the knowledge quiz. The follow-up rate for the second test at the end of the academic year was only 76% (90/119) as completion of this second test was purely voluntary.

Conclusions

This study found that addition of narration to a PowerPoint module was not associated with increased learning, a finding in keeping with Mayer’s principle of redundancy. As educators continue to produce online web modules, it is important that they apply the science of education to their instructional design in order to maximize learning capacity and not waste resources.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

IRB exempt.

Informed Consent

No.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chumley-Jones HS, Dobbie A, Alford CL. Web-based learning: sound educational method or hype? A review of the evaluation literature. Acad Med. 2002;77(10 Suppl):S86–S93. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210001-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Internet-based learning in the health professions: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1181–1196. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook DA. The research we still are not doing: an agenda for the study of computer-based learning. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):541–548. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200506000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer RE, Moreno R. A split-attention effect in multimedia learning: evidence for dual processing systems in working memory. J Educ Psychol. 1998;90:312–320. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer RE. Multimedia learning. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming N. Learning styles. http://www.vark-learn.com/english/index.asp. Accessed on March 13th 2013.

- 7.Rohrer D, Pashler H. Learning styles: where’s the evidence? Med Educ. 2012;46:634–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pashler H, McDaniel M, Rohrer D, Bjork R. Learning styles: concepts and evidence. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2008;9:105–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newton PM, Miah M. (2017) Evidence-based higher education – is the learning styles ‘myth’ important? Front Psychol 8;444, doi: 103389/psyg.2017.00444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Association of American Medical Colleges . Effective use of educational technology in medical education. Washington, DC AAMC: AAMC Institute for Improving Medical Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerfoot BP, Conlin PR, Travison T, McMahon GT. Web-based education in systems-based practice: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):361–366. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraenkel JR, Wallen NE. How to design and evaluate research in education. McGraw-Hill, editor. New York: 2003.

- 13.Brennan R. A generalized upper-lower item discrimination index. Educ Psychol Meas. 1972;32(2):289–303. doi: 10.1177/001316447203200206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell DS, Fonarow GC, Hays RD, Mangione CM. Self-study from web-based and printed guideline materials. A randomized, controlled trial among resident physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(12):938–946. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-12-200006200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spickard A, Smithers J, Cordray D, Gigante J, Wofford JL. A randomised trial of an online lecture with and without audio. Med Educ. 2004;38:787–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiebe EN, Slykhuis D, Leonard AA. Evaluating the effectiveness of scientific visualization in two PowerPoint delivery strategies on science learning for preservice science teachers. Int J Sci Math Educ. 2007;5:329–348. doi: 10.1007/s10763-006-9041-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn R. Learning style: state of the science. Theory Pract. 1984;23(1):10–19. doi: 10.1080/00405848409543084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]