Abstract

Atypical dopamine uptake inhibitors (DUIs) bind to the dopamine transporter and inhibit the reuptake of dopamine but have lower abuse potential than psychostimulants. Several atypical DUIs can block abuse-related effects of cocaine and methamphetamine, thus making them potential medication candidates for psychostimulant use disorders. The aim of the current study is to establish an in-vivo assay using EEG for the rapid identification of atypical DUIs with potential for medication development. The typical DUIs cocaine and methylphenidate dose-dependently decreased the power of the alpha, beta, and gamma bands. The atypical DUI modafinil and its F-analog, JBG1-049, decreased the power of beta, but in contrast to cocaine, none of the other frequency bands, while JHW007 did not significantly alter the EEG spectrum. The mu-opioid receptor agonists heroin and morphine dose-dependently decreased the power of gamma and increased power of the other bands. The effect of morphine on EEG power bands was antagonized by naltrexone. The NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine increased the power of all frequency bands. Therefore, typical and atypical DUIs and drugs of other classes differentially affected EEG spectra, showing distinctive features in the magnitude and direction of their effects on EEG. Comparative analysis of the effects of test drugs on EEG indicates a potential atypical profile of JBG1-049 with similar potency and effectiveness to its parent compound modafinil. These data suggest that EEG can be used to rapidly screen compounds for potential activity at specific pharmacological targets and provide valuable information for guiding the early stages of drug development.

Keywords: EEG, DAT inhibitors, Cocaine, JHW007, Opioids, in vivo, Modafinil, Heroin, Morphine, Ketamine

1. Introduction

Cocaine and methylphenidate bind with high affinity to the dopamine transporter (DAT) and inhibit the reuptake of dopamine, which increases levels of dopamine in the extracellular cleft (Carroll et al., 2002). The resulting indirect agonist action at dopamine receptors in the central nervous system is considered a crucial determinant of their psychostimulant as well as abuse-related effects (Di Chiara and Imperato, 1988; Hiranita and Collins, 2015; Ritz et al., 1987). Nevertheless, despite their high (low nanomolar) to moderate (low micromolar) affinity and selectivity for the DAT, other compounds bearing structural similarity to cocaine have been shown to vary in their effectiveness as psychostimulants and have been called atypical DUIs (Reith et al., 2015; Tanda et al., 2009).

Among these atypical DUIs, the N-substituted benztropine analog JHW007 is mostly devoid of the behavioral effects commonly observed in preclinical assays after cocaine administration (Agoston et al., 1997; Tanda et al., 2009). In particular, JHW007 does not stimulate locomotor activity, shares only limited discriminative-stimulus effects with cocaine and under a wide-range of dosing conditions is not self-administered (Desai et al., 2014, 2005; Hiranita et al., 2009; Kohut et al., 2014; Li et al., 2013). Another benzhydryl-containing DUI, modafinil (Provigil®) shares some of the behavioral effects of cocaine, but still with fewer indications of risk for abuse (Mereu et al., 2017, 2013; Zolkowska et al., 2009).

Modafinil has wake-promoting effects and produced drug-lever responding in animals trained to discriminate cocaine or amphetamine from vehicle, but it is self-administered at rates comparable with those of vehicle or a weak reinforcer (e.g. l-ephedrine) (Deroche-Gamonet et al., 2002; Gold and Balster, 1996; Heal et al., 2013; Hermant et al., 1991; Loland et al., 2012; Mereu et al., 2017; Paterson et al., 2010; Quisenberry et al., 2013). In humans, modafinil is used to treat sleep disorders and while it produced positive subjective effects (i.e. rating of “like”), it is self-administered within a laboratory setting only when drug effects could facilitate specific compensated activities (Billiard et al., 1994; Jasinski, 2000; Stoops et al., 2005; Vosburg et al., 2010). These findings and early data from post-marketing surveillance of modafinil suggest low if any abuse liability as compared with other DUIs (Jasinski and Kovacevic-Ristanovic, 2000; Myrick et al., 2004; Reith et al., 2015).

The potential modulation of the abuse related effects of typical DUIs by administration of atypical DUIs has been evaluated in preclinical and clinical studies (Reith et al., 2015; Tanda et al., 2009). In rodents, pretreatment with JHW007 shifts the cocaine or methamphetamine self-administration dose-effect curve downward at doses that have minimal effects on responding reinforced by food or other drugs (Hiranita et al., 2014, 2009; Zanettini et al., 2018). Similarly, chronic modafinil treatment decreases in a reinforcer-selective fashion responding maintained by cocaine in rhesus monkeys, as well as self-administration of cocaine and its physiological effects under laboratory settings in humans (Hart et al., 2008; Newman et al., 2010). Despite these initial promising results, successive randomized clinical trials have not consistently shown effectiveness of modafinil for cocaine or methamphetamine use disorders (Anderson et al., 2012, 2009; Dackis et al., 2012; Schmitz et al., 2014). Nevertheless, an increase in measures of cocaine abstinence have been observed with modafinil treatment in patients that had limited alcohol use, supporting the use of modafinil in at least a sub-population of cocaine dependent patients (Dackis et al., 2012; Kampman et al., 2015). Therefore, preclinical and clinical findings indicate potential therapeutic utility of atypical compounds targeting DAT as medications to attenuate the effects and/or replace abused psychostimulants (Grabowski et al., 2004; Howell and Negus, 2014; Reith et al., 2015).

The development and optimization of atypical DUIs as candidate pharmacotherapies for psychostimulant use disorders could be greatly advanced by prediction and selection of compounds with atypical profiles early in the in-vivo preclinical stages of drug development. The current study evaluates the effects of DUIs and of JBG1-049, a new modafinil analog with improved solubility, on the electroencephalographic activity (EEG) of freely moving rats with the aim to establish an early rapid in-vivo assay for the identification of DUIs with a potential atypical profile. EEG records the variation of electric potential from pyramidal neurons with high temporal and spatial resolution and is extensively used at different stages of the drug development pipeline to profile new chemical entities (Fink, 1980; Krijzer and van der Molen, 1987; Dimpfel et al., 2003; Leiser et al., 2011; Ahnaou et al., 2014; Maher et al., 2016). While some of the effects of psychostimulants on the EEG of animals and humans are known, a quantitative analysis and comparison of neurosignatures of different typical and atypical DUIs has not yet been reported. The pharmacological selectivity of the obtained EEG drug profiles was also assessed by characterizing compounds with other mechanisms of action and behavioral effects. These studies further indicate the utility of this technique for determining unique signatures of different centrally active classes of compounds. It is anticipated that EEG might be useful in a broad spectrum of drug development programs. Herein, we demonstrate its utility in identifying novel atypical DUIs for development as therapeutics to treat psychostimulant use disorders.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were individually housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room with food and water ad libitum under a 12:12-h light/dark cycle. Daily food rations were adjusted to maintain body weight of animals at approximately 350g. The animal facilities are fully accredited by AAALAC International and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the NIDA Intramural Research Program.

2.2. Drugs

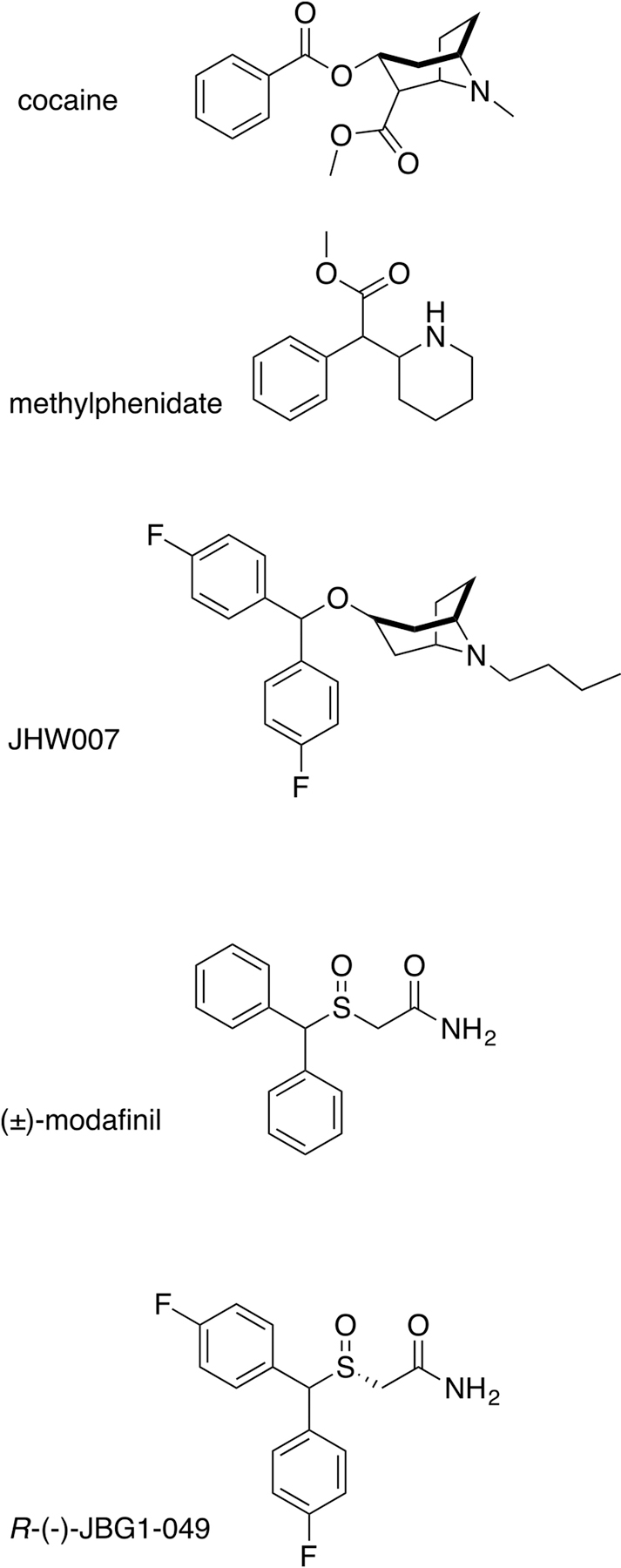

Typical dopamine uptake inhibitors, cocaine HCl (Mallinckrodt, St. Louis, MO) and methylphenidate HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), the atypical dopamine uptake inhibitor JHW007 (synthesized in the Medicinal Chemistry Section, NIDA-IRP, according to the methods described in Agoston et al. 1997), the mu-opioid agonists heroin (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC), morphine sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich), and the NMDA-receptor antagonist, ketamine HCl (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) were dissolved in saline (0.9% sodium chloride, USP; Hospira). The atypical DUI (±)-modafinil and its analog R-(−)-JBG1-049 (synthesized in the Medicinal Chemistry Section, NIDA-IRP according to methods described in Cao et al., 2010 and Keighron et al 2018 EJN submitted) were dissolved in a vehicle of 10% DMSO, 15% TWEEN 80 and saline. The structures of all the DUIs described can be seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of typical and atypical DUIs.

2.3. Intravenous catheter and EEG implant surgery

Rats were anesthetized with introperitoneal injections of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (20 mg/kg). Intravenous jugular catheters (RJV-1, SAI Infusion Technology, Lake Villa, IL) and relative back mounts (313-000BM-10-5UP, PlasticsOne Inc., Roanoke, VA) were implanted as previously described in Zanettini et al. (2018). Catheters were flushed with infusion of 0.2 ml of a gentamicin-heparin solution (0.4 mg/ml - 30 U/ml, respectively) and back mounts were kept closed with dust-cups (C313CAC, PlasticsOne Inc.).

Stainless steel screws (2AE96, Grainger, Lake Forest, IL) soldered to striped electric wire (UAA3601, MicronMeters, Saint George, UT) served as electrodes and were implanted bilaterally (coordinates in mm from bregma) on the frontal (AP: 3, ML: ±2), parietal (AP: −2, ML: ±4) and occipital (AP: −6, ML: ±4) regions of the skull; two additional electrodes worked as reference and ground (AP: −11, ML: ±2.5). Electrodes were connected through a custom-made electrode-interface board to a connector (A71314-801, OMNETICS, Minneapolis, MN) that was chronically implanted on animal’s skull and served as receptacle for the acquisition of the EEG signals. The antibiotic Baytril ® (enrofloxacin,) was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 10 mg/kg for at least 3 days post-surgery.

2.4. Experimental procedure and data collection.

During experimental sessions, animals were placed in a microdialysis bowl cage (MD-1514, Basi, West Lafayette, IN) containing clean bedding. The bowl cage was located on a Stand-Alone Raturn (Basi) inside a ventilated and illuminated holding cubicle that was equipped with metal mesh to provide electromagnetic isolation. The connector on the animal was coupled to an headstage amplifier board (RHD2132 #C3314, Intan, Los Angeles, CA) in which signal was band passed between 0.1 to 125 Hz, digitized at 2 kHz, and sent to an USB-interface board (RHD2000 #3100, Intan) through a SPI cable (RHD2000 #33206, Intan). The interface was controlled by a Windows based computer running a recording-system software (v1.5, Intan).

During sessions, a 2.5-mL syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) containing the test drug or vehicle was placed in the syringe driver (CMA/100, Carnagie Medicine, Stockholm, Sweden), which operates at a rate of 4.125 µL/min. A polyethylene tubing (BPTE-50), which was protected by a metal spring (C313CS, PlasticsOne), connected the syringe to the back mount of the animal. In-session dose-effect curves were determined for each subject administering intravenously doses of the test compound at fixed-intervals of time. For each compound, pharmacokinetic data and/or pilot time-course studies were used to guide the selection of the length of the session and of the fixed-intervals of injection such that the maximal effect of each dose of drug and of the dose-effect curve was captured. Cumulative doses of cocaine (0.1–3.2 mg/kg) or methylphenidate (0.1–5.6 mg/kg) were administered at 10 min intervals whereas cumulative doses of modafinil (1–32 mg/kg), JHW007 (1–10 mg/kg), JBG1-049 (1–32 mg/kg) or morphine (0.32–5.6 and 10–17.8 mg/kg) every 30 min. Because of their short half-life, full doses (i.e. not cumulative) of ketamine or heroin were administered every 30 min. In selected sessions, a single dose of naltrexone (0.032 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously 5 min before the determination of the morphine dose-effect curve. Animals were tested no more than once every 7 days and drugs were administered in an unsystematic order. A white noise generator located in the experimental room was kept on during the session recording.

2.5. Data analysis

Initial analysis was performed with python (Python Software Foundation, https://www.python.org/). Data were imported and power was estimated for epochs of 10 sec at 0.5 Hz interval steps using the scipy function scipy.signal.spectrogram with windows of 10 sec and a step of 2 s (Jones et al., 2001). R (The R core team, http://www.R-project.org) and the relative reticulate and tidyverse packages were used to calculate for each animal the average power of delta (0–4 Hz], theta (4– 8Hz], alpha (8–13], beta (13–30], gamma (30–50 Hz] bands using 1 min bins for heroin and ketamine and 5 min bins for all the other drugs. For each animal and electrode, the power of the frequency band was then normalized to the pre-infusion interval (baseline) and expressed as % of baseline values ± Standard Error of the Mean (S.E.M) (Allaire et al., 2018; Wickham, 2017). Group data were obtained by averaging the power of bands recorded in the same region and then across subjects. Cumulative dose-effect curves plotted the % of baseline value of the last bin of each injection interval against the corresponding bin after dose administration (i.e. 5 min after injection of cocaine and methylphenidate and 25 min after injection of the other test compounds). Because full doses of heroin and ketamine were administered (i.e. not cumulative), the 3th and 4th bin of each injection intervals (i.e. 3 and 4 min after injection) were used in dose-effect curves, respectively. Dose-effect curves of each compound were analyzed by one-way repeated measure ANOVA with dose as independent factor. Low (0.1–5.6 mg/kg) and high doses of morphine (10–17.8 mg/kg) were tested in different sessions (to limit the duration of the session) and analyzed in separate ANOVAs. Power at each dose was then compared with the one obtained during the baseline period by Dunnet’s post-hoc test. The nlme and multcomp packages were used to perform statistical analysis (Hothorn et al., 2008; Pinheiro et al., 2018). Radar plots were modified from graphs created in R using the package fmsb (Nakazawa, 2018).

3. Results

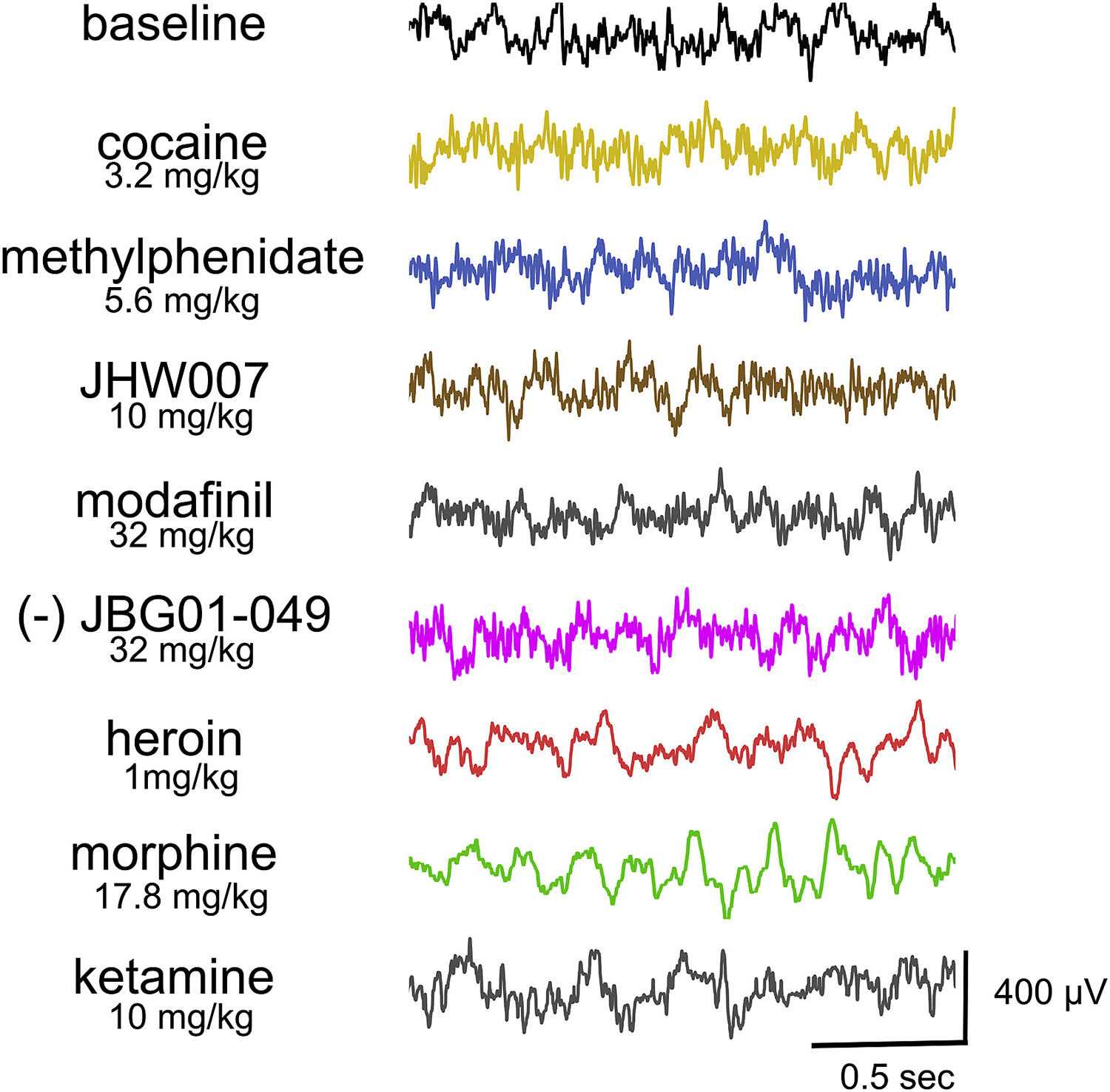

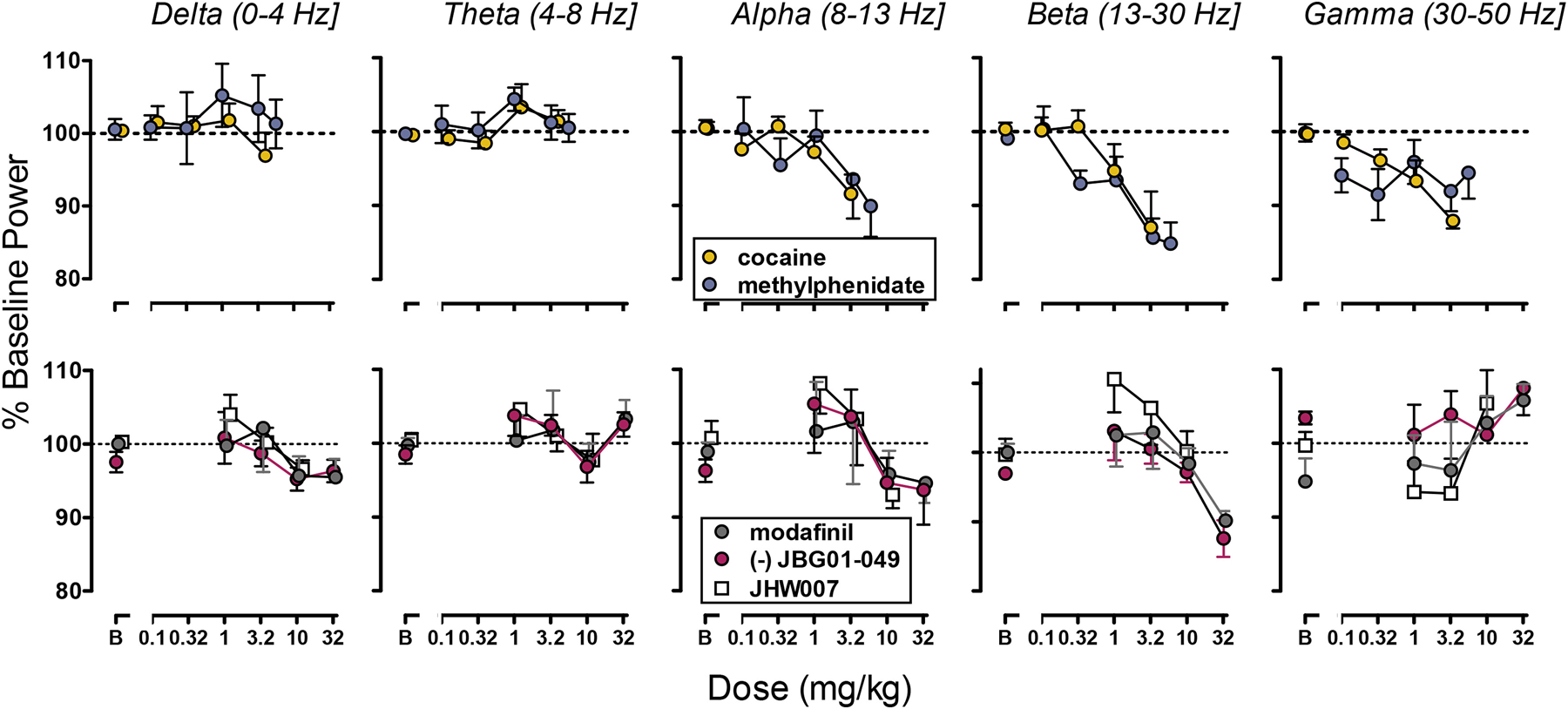

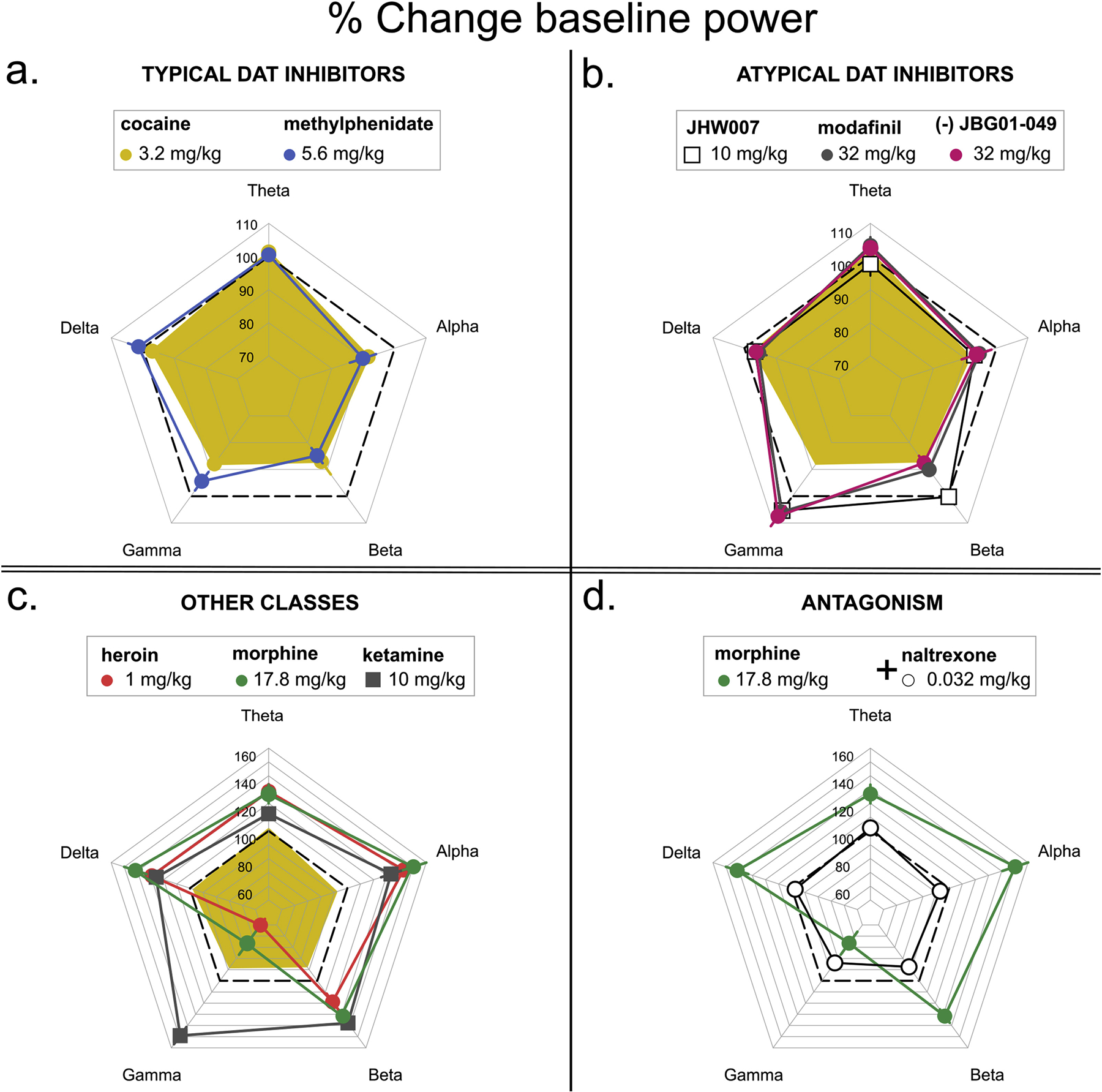

Administration of the typical DUIs, cocaine and methylphenidate, altered baseline EEG signal (Fig. 2). Spectral analysis revealed that the typical DUIs decreased power of high but not low frequencies bands with similar potency and minima. In particular, cocaine dose-dependently decreased the power of alpha (F4,16=3.723, p<0.05), beta (F4,16=8.533, p<0.01) and gamma bands (F4,16=15.217, p<0.01). Methylphenidate dose-dependently decreased power of the beta band (F5,25=9.556, p<0.05) and post-hoc analysis revealed that the doses of 0.32 and 3.2 mg/kg decreased the power of the gamma-band power (Fig. 3, Fig. 5a).

Fig. 2.

Representative EEG signals from frontal electrodes of rats during baseline and after administration of test compounds. Ordinates: µVolts. Abscissa: Time in seconds.

Fig. 3.

Top panels: Effects of the typical DUIs cocaine (N=6) and methylphenidate (N=6, top panels), on the power of frontal frequencies bands. Bottom panels: Effect of atypical DUIs modafinil (N=7) and JHW007 (N=5) and of JBG1-049 (N=6) on frontal frequencies bands. Ordinate: Percentage of Baseline Power (mean ± S.E.M). Abscissa: Dose expressed in mg/kg.

The atypical DUIs, modafinil and its analog JBG1-049, dose-dependently reduced power of the beta-band power (F4,14=3.121, p<0.01; F4,19=5.792, p<0.01, respectively) but in contrast with cocaine, they did not significantly alter the power of either alpha or gamma bands. No significant change from baseline power was obtained after administration of the benztropine analog, JHW007 (1–10 mg/kg) (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 5b).

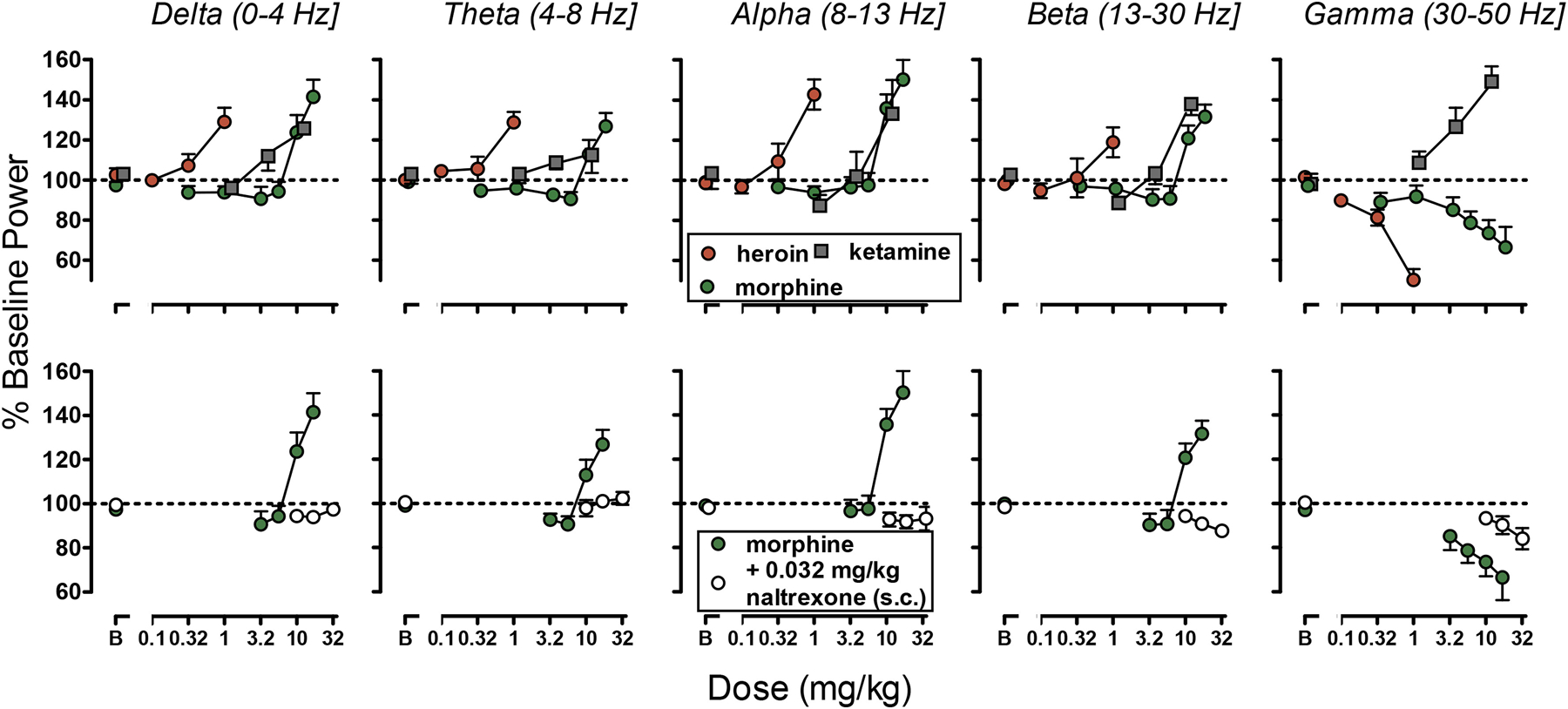

The mu-opioid agonists heroin and morphine produced a synchronization and increase in the amplitude of the signal (Fig. 2). The power of delta, theta, alpha and beta bands were increased while the power of gamma was decreased by administration of the mu-opioid agonists morphine (F2,8=17.34; F2,8=8.406; F2,8=24.875; F2,8=14.589; F2,8=10.418, p <0.01) or heroin (F3,15=9.656; F3,15=12.167; F3,15=17.232; F3,15=3.489; F3,15=31.505, p<0.01). Low doses of morphine produced a modest decrease in theta (F4, 20=2.823, p = 0.05) and the dose of 5.6 mg/kg of the beta power (t=−3.034, p<0.01). The two opioids showed comparable maximal effects on EEG spectra with heroin approximately 10-fold more potent than morphine (Fig. 3, Fig. 5c). The NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine increased slow wave signal and the power of delta (F3,12 = 8.928, p<0.01), theta (F3,12=3.287, p=0.05), alpha (F3,12=17.567, p<0.01) and beta (F3,12=39.586, p<0.01) bands to similar maxima observed after mu-opioid agonists administration. However, in contrast with opioids, ketamine increased power of the gamma band (F3,12=14.067, p<0.01; Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 5c).

The effects of morphine on the EEG signal and power were prevented by administration of 0.032 mg/kg naltrexone. While no significant effect of morphine on theta or alpha bands was observed, a small yet significant reduction in the power of delta (F3,12=5.732, p=0.01), beta (F3,12=7.063, p<0.01) and gamma (F3,12=5.181, p<0.05) was observed in animals pretreated with naltrexone (Fig. 4, Fig. 5d).

Fig. 4.

Top panels: Effects of the µ-opioid receptor agonists heroin (N=6) and morphine (N=6) and the NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine (N=5) on the power of frontal frequencies bands. Bottom panels: Effect of pretreatment with naltrexone (N=5) on morphine induced modulation of the power of frontal frequencies bands. Ordinate: Percentage of Baseline Power (mean ± S.E.M). Abscissa: Dose expressed in mg/kg.

Fig. 5.

Maximal effects of typical (a.), atypical DUIs (b.), opioids and NMDA antagonist ketamine (c.), and morphine + naltrexone (d.) on frequency power. For comparison purposes, the effects of 3.2 mg/kg cocaine (yellow) are also reported in panel b and c. Ordinate: Percentage of Baseline Power (mean ± S.E.M).

4. Discussion

Atypical dopamine uptake inhibitors (DUIs) have preferential selectivity for DAT with affinity in the low nanomolar to low micromolar range. Nevertheless, atypical DUIs have distinct behavioral effects from cocaine and predicted low abuse potential. Preclinical and clinical evidence suggest that this class of compounds might have therapeutic utility for treating psychostimulant use disorders. The current study explored the effects of several typical and atypical DUIs as well as other classes of centrally active drugs, on EEG of freely moving rats to identify a potential neurosignature of atypical DUIs that could be used to guide drug development and optimization of pharmacotherapies.

The typical DUIs cocaine and methylphenidate produced a desynchronization of the EEG signal with a specific decrease in the power of the high frequencies alpha, beta and gamma.

These results are consistent with other reports of effects of those DUIs and amphetamines on the brain electrical activity of rats under resting conditions and are indicative of increases in levels of arousal (Devilbiss and Berridge, 2008; Ferger et al., 1994; Glatt et al., 1983; Luoh et al., 1994). In particular, the decrease in the power of those high bands produced by cocaine correlates with both an increase in dopamine dialyzed from the prefrontal cortex of rats and behavioral measures of motor stimulation and these effects can be prevented by antagonism of D1-D2 dopamine receptors (Ferger et al., 1994; Luoh et al., 1994). Similarly, in early clinical studies employing frequency and amplitude analysis amphetamines and DUIs were categorized as a class of drugs producing EEG desynchronization (Fink, 1969). While more recent clinical studies have reported increased EEG activity after administration of cocaine (Lukas et al., 1989), this effect was characterized by an increase of the frontal power of low/high frequencies, in contrast with animal studies (Herning et al., 1994; Reid et al., 2006). This discrepancy between clinical and preclinical studies might be the result of species-specific brain differences and/or the particular experimental conditions of testing. A possible important determinant of these effects is the drug history of the subjects that in clinical, but not preclinical, studies had exposure/dependence to psychostimulants and therefore expected persistent baseline changes in electric brain activity (Alper et al., 1998; Newton et al., 2003). Repeated treatment with stimulants has also been shown to produce effects on the power of EEG bands in rats that can markedly differ in its direction when compared with that of acute drug administration (Ferger et al., 1996; Stahl et al., 1997).

The atypical DUIs JHW007 and modafinil had an EEG profile distinct from that of the typical DUIs cocaine and methylphenidate. The absence of significant alteration of the EEG spectrum by the atypical DUI JHW007 parallels previous findings obtained in preclinical behavioral assays of locomotor activity, drug self-administration, and cocaine discrimination (Reith et al., 2015). Conversely, modafinil produced a desynchronization of the EEG signal characterized by a decrease in the power of beta frequencies also reported by another laboratory (Sebban et al., 1999). Therefore, modafinil shared some of the effects of cocaine and methylphenidate on EEG (i.e. decrease in beta power) but not others (decrease in alpha and gamma). These findings are consistent with reports that modafinil, but not JHW007, produces some of the stimulating effects (i.e. wake promotion) of abused DUIs in humans and animals, but still has low abuse potential.

The compound JBG1-049, a modafinil analog with improved solubility, but similar affinity for DAT (Ki=4830 nM vs. Ki=5480 nM for modafinil; (Keighron et al., 2018 EJN submitted), had EEG effects that overlapped with those of modafinil, suggesting a potential atypical profile. This hypothesis is supported by a recent comparison of the behavioral and neurochemical effects of JBG1-049 and R-modafinil (Keighron et., al 2018 Eur. J. Neurosci, in press). Moreover, the equivalent potency and effectiveness of JBG1-049 and its parent compound exclude possible solubility factors as a determinant of the differential effects on EEG by modafinil and typical DUIs (Lazenka and Negus, 2017).

A series of other compounds with effects and mechanisms of action different than DUIs were assessed to evaluate the pharmacological selectivity of the current assay. Mu opioids and the NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine had effects on EEG that were qualitatively and quantitatively different than those of typical and atypical DUIs. Heroin and morphine produced a synchronization of the EEG signal with increases in slow and medium frequency bands, whereas ketamine administration lead to a generalized elevation of the power of all bands including gamma (Ferger and Kuschinsky, 1995; Jones et al., 2012; Lukas et al., 1982; Young et al., 1987; Zuo et al., 2007). Increases in frequency power and synchronization of the signal have been previously reported with opioids (Zuo et al., 2007) and are associated with a corresponding rise in measures of stupor, sedation and catalepsy (Lukas et al., 1980). Similarly, an elevation of gamma oscillations has been observed after administration of another NMDA receptor antagonist, MK801 (Hakami et al., 2009; Pinault, 2008), and the ketamine-induced change in gamma was normalized by administration of the antipsychotic haloperidol (Jones et al., 2012). Taken together, these data indicate that drugs from the same pharmacological class (i.e., opioids, typical and atypical DUIs and NMDA antagonists) have similar EEG profiles, which are distinct from those of other classes. In addition, the pharmacological nature of the effects observed in the current study was further supported by the blockade of the mu opioid antagonist naltrexone on the opioid EEG signature. This experiment also exemplifies the additional value of EEG for exploring drug-drug interactions and identifying compounds that attenuate the effects of drugs of abuse.

In summary, quantitative analysis of EEG spectra revealed different neurosignatures of typical and atypical DUIs and of other central nervous system active drugs. These data suggest that evaluation of the EEG signal can be used to identify new DUIs, such as JBG 1-049, with potential atypical profiles in the early preclinical phase of drug development and can accelerate the discovery of possible treatments for psychostimulant use disorders. Similar strategies have been used in the past in clinical and preclinical research to predict therapeutic effectiveness of candidate pharmacotherapies for anxiety and depression (Krijzer and van der Molen, 1987) and have been successful in the early recognition of the antidepressant potential of the tricyclics doxepin and mianserin (Itil et al., 1972; Simeon et al., 1969; for an historical account Fink, 2010). Moreover, the current study supports the use of EEG as a functional assay to study drug-drug interactions and to facilitate the discovery of new chemical entities that can attenuate the effects of drugs of abuse.

Highlights.

Atypical dopamine uptake inhibitors are candidate pharmacotherapies for psychostimulant use disorders.

Typical and atypical dopamine uptake inhibitors, as well as centrally active drugs from other classes, produce distinct EEG neurosignatures.

EEG can be used for the early identification of dopamine uptake inhibitors with an atypical profile.

7. Acknowledgments

We thank Brenna Swider and Mark Coggiano for administrative assistance.

6. Funding and Disclosure

The current studies were supported by funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Intramural Research Program (IRP) ZIA DA000389 and ZIA DA000611. The authors are all employees of the NIH and have no disclosures. Care of the animals was in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program Animal Care and Use Program, which is fully accredited by AAALAC International.

5 References

- Agoston GE, Wu JH, Izenwasser S, George C, Katz J, Kline RH, Newman AH, 1997. Novel N-substituted 3 alpha-[bis(4’-fluorophenyl)methoxy]tropane analogues: selective ligands for the dopamine transporter. J. Med. Chem 40, 4329–4339. 10.1021/jm970525a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahnaou A, Huysmans H, Jacobs T, Drinkenburg WH, 2014. Cortical EEG oscillations and network connectivity as efficacy indices for assessing drugs with cognition enhancing potential. Neuropsychopharmacology 86, 362–77. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaire JJ, Ushey K, Tang Y, 2018. reticulate: Interface to “Python.” https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=reticulate

- Alper KR, Prichep LS, Kowalik S, Rosenthal MS, John ER, 1998. Persistent QEEG abnormality in crack cocaine users at 6 months of drug abstinence. Neuropsychopharmacology 19, 1–9. 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00211-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, Li S-H, Biswas K, McSherry F, Holmes T, Iturriaga E, Kahn R, Chiang N, Beresford T, Campbell J, Haning W, Mawhinney J, McCann M, Rawson R, Stock C, Weis D, Yu E, Elkashef AM, 2012. Modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 120, 135–141. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, Reid MS, Li S-H, Holmes T, Shemanski L, Slee A, Smith EV, Kahn R, Chiang N, Vocci F, Ciraulo D, Dackis C, Roache JD, Salloum IM, Somoza E, Urschel I, Elkashef AM, 2009. Modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 104, 133–139. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billiard M, Besset A, Montplaisir J, Laffont F, Goldenberg F, Weill JS, Lubin S, 1994. Modafinil: a double-blind multicentric study. Sleep 17, S107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Prisinzano TE, Okunola OM, Kopajtic T, Shook M, Katz JL, Newman AH, 2010. Structure-Activity Relationships at the Monoamine Transporters for a Novel Series of Modafinil (2-[(diphenylmethyl)sulfinyl]acetamide) Analogues. ACS Med Chem Lett 2, 48–52. 10.1021/ml1002025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FI, Lewin AH, Mascarella SW, 2002. Dopamine-Transporter Uptake Blockers, in: Neurotransmitter Transporters, Contemporary Neuroscience Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 381–432. 10.1007/978-1-59259-158-9_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Plebani JG, Pettinati HM, Sparkman T, O’Brien CP, 2012. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat 43, 303–312. 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche-Gamonet V, Darnaudéry M, Bruins-Slot L, Piat F, Moal ML, Piazza P, 2002. Study of the addictive potential of modafinil in naive and cocaine-experienced rats. Psychopharmacology 161, 387–395. 10.1007/s00213-002-1080-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RI, Grandy DK, Lupica CR, Katz JL, 2014. Pharmacological characterization of a dopamine transporter ligand that functions as a cocaine antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 348, 106–115. 10.1124/jpet.113.208538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RI, Kopajtic TA, Koffarnus M, Newman AH, Katz JL, 2005. Identification of a dopamine transporter ligand that blocks the stimulant effects of cocaine. J. Neurosci 25, 1889–1893. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4778-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilbiss DM, Berridge CW, 2008. Cognition-Enhancing Doses of Methylphenidate Preferentially Increase Prefrontal Cortex Neuronal Responsiveness. Biological Psychiatry, Endophenotypes for Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder 64, 626–635. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A, 1988. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 85, 5274–5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimpfel W, 2003. Preclinical data base of pharmaco-specific rat EEG fingerprints (tele-stereo-EEG). Eur J Med Res. 2003 May 30;8(5):199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferger B, Kropf W, Kuschinsky K, 1994. Studies on electroencephalogram (EEG) in rats suggest that moderate doses of cocaine ord-amphetamine activate D1 rather than D2 receptors. Psychopharmacology 114, 297–308. 10.1007/BF02244852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferger B, Kuschinsky K, 1995. Effects of morphine on EEG in rats and their possible relations to hypo- and hyperkinesia. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 117, 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferger B, Stahl D, Kuschinsky K, 1996. Effects of cocaine on the EEG power spectrum of rats are significantly altered after its repeated administration: do they reflect sensitization phenomena? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol 353, 545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, 2010. Remembering the lost neuroscience of pharmaco-EEG. Acta Psychiatr Scand 121, 161–173. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, 1980. An objective classification of psychoactive drugs. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology 4, 495–502. 10.1016/0364-7722(80)90019-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, 1969. EEG and human psychopharmacology. Annu Rev Pharmacol 9, 241–258. 10.1146/annurev.pa.09.040169.001325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatt A, Duerst T, Mueller B, Demieville H, 1983. EEG evaluation of drug effects in the rat. Neuropsychobiology 9, 163–166. 10.1159/000117957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LH, Balster RL, 1996. Evaluation of the cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects and reinforcing effects of modafinil. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 126, 286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Shearer J, Merrill J, Negus SS, 2004. Agonist-like, replacement pharmacotherapy for stimulant abuse and dependence. Addict Behav 29, 1439–1464. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakami T, Jones NC, Tolmacheva EA, Gaudias J, Chaumont J, Salzberg M, O’Brien TJ, Pinault D, 2009. NMDA receptor hypofunction leads to generalized and persistent aberrant gamma oscillations independent of hyperlocomotion and the state of consciousness. PLoS ONE 4, e6755. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Vosburg SK, Rubin E, Foltin RW, 2008. Smoked cocaine self-administration is decreased by modafinil. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 761–768. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heal DJ, Buckley NW, Gosden J, Slater N, France CP, Hackett D, 2013. A preclinical evaluation of the discriminative and reinforcing properties of lisdexamfetamine in comparison to d-amfetamine, methylphenidate and modafinil. Neuropharmacology 73, 348–358. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermant JF, Rambert FA, Duteil J, 1991. Awakening properties of modafinil: effect on nocturnal activity in monkeys (Macaca mulatta) after acute and repeated administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 103, 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herning RI, Glover BJ, Koeppl B, Phillips RL, London ED, 1994. Cocaine-induced increases in EEG alpha and beta activity: evidence for reduced cortical processing. Neuropsychopharmacology 11, 1–9. 10.1038/npp.1994.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiranita T, Collins GT, 2015. Differential Roles for Dopamine D1-Like and D2-Like Receptors in Mediating the Reinforcing Effects of Cocaine: Convergent Evidence from Pharmacological and Genetic Studies. J Alcohol Drug Depend 3. 10.4172/2329-6488.1000e124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiranita T, Kohut SJ, Soto PL, Tanda G, Kopajtic TA, Katz JL, 2014. Preclinical efficacy of N-substituted benztropine analogs as antagonists of methamphetamine self-administration in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 348, 174–191. 10.1124/jpet.113.208264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiranita T, Soto PL, Newman AH, Katz JL, 2009. Assessment of reinforcing effects of benztropine analogs and their effects on cocaine self-administration in rats: comparisons with monoamine uptake inhibitors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 329, 677–686. 10.1124/jpet.108.145813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P, 2008. Simultaneous Inference in General Parametric Models. Biometrical Journal 50, 346–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Negus SS, 2014. Monoamine transporter inhibitors and substrates as treatments for stimulant abuse. Adv. Pharmacol 69, 129–176. 10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00004-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itil TM, Polvan N, Hsu W, 1972. Clinical and EEG effects of GB-94, a “tetracyclic” antidepressant (EEG model in discovery of a new psychotropic drug). Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 14, 395–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski DR, 2000. An evaluation of the abuse potential of modafinil using methylphenidate as a reference. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 14, 53–60. 10.1177/026988110001400107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski DR, Kovacevic-Ristanovic R, 2000. Evaluation of the Abuse Liability of Modafinil and Other Drugs for Excessive Daytime Sleepiness Associated with Narcolepsy. Clinical Neuropharmacology 23, 149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E, Oliphant T, Peterson P, others, 2001. SciPy: Open source scientific tools for Python

- Jones NC, Reddy M, Anderson P, Salzberg MR, O’Brien TJ, Pinault D, 2012. Acute administration of typical and atypical antipsychotics reduces EEG γ power, but only the preclinical compound LY379268 reduces the ketamine-induced rise in γ power. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 15, 657–668. 10.1017/S1461145711000848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, Spratt K, Wierzbicki MR, Dackis C, O’Brien CP, 2015. A double blind, placebo controlled trial of modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence without co-morbid alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 155, 105–110. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohut SJ, Hiranita T, Hong S-K, Ebbs AL, Tronci V, Green J, Garcés-Ramírez L, Chun LE, Mereu M, Newman AH, Katz JL, Tanda G, 2014. Preference for distinct functional conformations of the dopamine transporter alters the relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and stimulation of mesolimbic dopamine. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 802–809. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijzer FN, van der Molen R, 1987. Classification of psychotropic drugs by rat EEG analysis: the anxiolytic profile in comparison to the antidepressant and neuroleptic profile. Neuropsychobiology 18, 51–56. 10.1159/000118392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazenka MF, Negus SS, 2017. Oral modafinil facilitates intracranial self-stimulation in rats: comparison with methylphenidate. Behav Pharmacol 28, 318–322. 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiser SC, Dunlop J, Bowlby MR, Devilbiss DM, 2011. Aligning strategies for using EEG as a surrogate biomarker: A review of preclinical and clinical research. Biochemical Pharmacology, Translational Medicine 81, 1408–1421. 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Hiranita T, Hayashi S, Newman AH, Katz JL, 2013. The stereotypy-inducing effects of N-substituted benztropine analogs alone and in combination with cocaine do not account for their blockade of cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 225, 733–742. 10.1007/s00213-012-2862-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loland CJ, Mereu M, Okunola OM, Cao J, Prisinzano TE, Mazier S, Kopajtic T, Shi L, Katz JL, Tanda G, Newman AH, 2012. R-modafinil (armodafinil): a unique dopamine uptake inhibitor and potential medication for psychostimulant abuse. Biol. Psychiatry 72, 405–413. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas SE, Mendelson JH, Amass L, Benedikt R, 1989. Behavioral and EEG studies of acute cocaine administration: comparisons with morphine, amphetamine, pentobarbital, nicotine, ethanol and marijuana. NIDA Res. Monogr 95, 146–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas SE, Moreton JE, Khazan N, 1982. Differential electroencephalographic and behavioral cross tolerance to morphine and methadone in the l-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM)-maintained rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 220, 561–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas SE, Moreton JE, Khazan N, 1980. Comparative study of the electroencephalographic and behavioral effects of l-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM), two of its metabolites and morphine and methadone in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 215, 382–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoh H-F, Kuo TBJ, Chan SHH, Pan WHT, 1994. Power spectral analysis of electroencephalographic desynchronization induced by cocaine in rats: Correlation with microdialysis evaluation of dopaminergic neurotransmission at the medial prefrontal cortex. Synapse 16, 29–35. 10.1002/syn.890160104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher MP, Wu N, Ravula S, Ameriks MK, Savall BM, Liu C, Lord B, Wyatt RM, Matta JA, Dugovic C, Yun S, Ver Donck L, Steckler T, Wickenden AD, Carruthers NI, Lovenberg TW, 2016. Discovery and Characterization of AMPA Receptor Modulators Selective for TARP-γ8. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 357, 394–414. 10.1124/jpet.115.231712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereu M, Bonci A, Newman AH, Tanda G, 2013. The neurobiology of modafinil as an enhancer of cognitive performance and a potential treatment for substance use disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 229, 415–434. 10.1007/s00213-013-3232-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereu M, Chun LE, Prisinzano TE, Newman AH, Katz JL, Tanda G, 2017. The unique psychostimulant profile of (±)-modafinil: investigation of behavioral and neurochemical effects in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci 45, 167–174. 10.1111/ejn.13376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick H, Malcolm R, Taylor B, LaRowe S, 2004. Modafinil: preclinical, clinical, and post-marketing surveillance--a review of abuse liability issues. Ann Clin Psychiatry 16, 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa M, 2018. fmsb: Functions for Medical Statistics Book with some Demographic Data https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=fmsb

- Newman JL, Negus SS, Lozama A, Prisinzano TE, Mello NK, 2010. Behavioral Evaluation of Modafinil and The Abuse-related Effects of Cocaine in Rhesus Monkeys. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 18, 395–408. 10.1037/a0021042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton TF, Cook IA, Kalechstein AD, Duran S, Monroy F, Ling W, Leuchter AF, 2003. Quantitative EEG abnormalities in recently abstinent methamphetamine dependent individuals. Clin Neurophysiol 114, 410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson NE, Fedolak A, Olivier B, Hanania T, Ghavami A, Caldarone B, 2010. Psychostimulant-like discriminative stimulus and locomotor sensitization properties of the wake-promoting agent modafinil in rodents. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 95, 449–456. 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinault D, 2008. N-methyl d-aspartate receptor antagonists ketamine and MK-801 induce wake-related aberrant gamma oscillations in the rat neocortex. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 730–735. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team, 2018. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

- Quisenberry AJ, Prisinzano T, Baker LE, 2013. Combined effects of modafinil and d-amphetamine in male Sprague-Dawley rats trained to discriminate d-amphetamine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 110, 208–215. 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MS, Flammino F, Howard B, Nilsen D, Prichep LS, 2006. Topographic Imaging of Quantitative EEG in Response to Smoked Cocaine Self-Administration in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 31, 872–884. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith MEA, Blough BE, Hong WC, Jones KT, Schmitt KC, Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Rothman RB, Katz JL, 2015. Behavioral, biological, and chemical perspectives on atypical agents targeting the dopamine transporter. Drug Alcohol Depend 147, 1–19. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ, 1987. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science 237, 1219–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Green CE, Stotts AL, Lindsay JA, Rathnayaka NS, Grabowski J, Moeller FG, 2014. A two-phased screening paradigm for evaluating candidate medications for cocaine cessation or relapse prevention: modafinil, levodopa-carbidopa, naltrexone. Drug Alcohol Depend 136, 100–107. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebban C, Zhang XQ, Tesolin-Decros B, Millan MJ, Spedding M, 1999. Changes in EEG spectral power in the prefrontal cortex of conscious rats elicited by drugs interacting with dopaminergic and noradrenergic transmission. British Journal of Pharmacology 128, 1045–1054. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeon J, Spero M, Fink M, 1969. Clinical and EEG studies of doxepin. An interim report. Psychosomatics 10, 14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl D, Ferger B, Kuschinsky K, 1997. Sensitization to d-amphetamine after its repeated administration: evidence in EEG and behaviour. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol 356, 335–340. 10.1007/PL00005059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Lile JA, Fillmore MT, Glaser PEA, Rush CR, 2005. Reinforcing effects of modafinil: influence of dose and behavioral demands following drug administration. Psychopharmacology 182, 186–193. 10.1007/s00213-005-0044-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Newman AH, Katz JL, 2009. Discovery of drugs to treat cocaine dependence: behavioral and neurochemical effects of atypical dopamine transport inhibitors. Adv. Pharmacol 57, 253–289. 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)57007-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosburg SK, Hart CL, Haney M, Rubin E, Foltin RW, 2010. Modafinil does not serve as a reinforcer in cocaine abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend 106, 233–236. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, 2017. tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the “Tidyverse.” https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyverse

- Young GA, Hong O, Khazan N, 1987. EEG, EEG Power Spectra, and Behavioral Correlates of Opioids and Other Psychoactive Agents, in: Williams M, Malick JB (Eds.), Drug Discovery and Development Humana Press, pp. 199–226. 10.1007/978-1-4612-4828-6_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanettini C, Wilkinson DS, Katz JL, 2018. Behavioral economic analysis of the effects of N-substituted benztropine analogs on cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 235, 47–58. 10.1007/s00213-017-4739-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkowska D, Jain R, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Setola V, Prisinzano TE, Baumann MH, 2009. Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant effects of modafinil. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 329, 738–746. 10.1124/jpet.108.146142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y-F, Wang J-Y, Chen J-H, Qiao Z-M, Han J-S, Cui C-L, Luo F, 2007. A comparison between spontaneous electroencephalographic activities induced by morphine and morphine-related environment in rats. Brain Research 1136, 88–101. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]