Key Points

Question

How did health care spending vary by race and ethnicity groups in the US from 2002 through 2016?

Findings

This exploratory study that included data from 7.3 million health system visits, admissions, or prescriptions found age-standardized per-person spending was significantly greater for White individuals than the all-population mean for ambulatory care; for Black individuals for emergency department and inpatient care; and for American Indian and Alaska Native individuals for emergency department care. Hispanic and Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander individuals had significantly less per-person spending than did the all-population mean for most types of care, and these differences persisted when controlling for underlying health.

Meaning

In the US from 2002 through 2016, there were differences in age-standardized health care spending by race and ethnicity across different types of care.

Abstract

Importance

Measuring health care spending by race and ethnicity is important for understanding patterns in utilization and treatment.

Objective

To estimate, identify, and account for differences in health care spending by race and ethnicity from 2002 through 2016 in the US.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This exploratory study included data from 7.3 million health system visits, admissions, or prescriptions captured in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (2002-2016) and the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (2002-2012), which were combined with the insured population and notified case estimates from the National Health Interview Survey (2002; 2016) and health care spending estimates from the Disease Expenditure project (1996-2016).

Exposure

Six mutually exclusive self-reported race and ethnicity groups.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Total and age-standardized health care spending per person by race and ethnicity for each year from 2002 through 2016 by type of care. Health care spending per notified case by race and ethnicity for key diseases in 2016. Differences in health care spending across race and ethnicity groups were decomposed into differences in utilization rate vs differences in price and intensity of care.

Results

In 2016, an estimated $2.4 trillion (95% uncertainty interval [UI], $2.4 trillion-$2.4 trillion) was spent on health care across the 6 types of care included in this study. The estimated age-standardized total health care spending per person in 2016 was $7649 (95% UI, $6129-$8814) for American Indian and Alaska Native (non-Hispanic) individuals; $4692 (95% UI, $4068-$5202) for Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) individuals; $7361 (95% UI, $6917-$7797) for Black (non-Hispanic) individuals; $6025 (95% UI, $5703-$6373) for Hispanic individuals; $9276 (95% UI, $8066-$10 601) for individuals categorized as multiple races (non-Hispanic); and $8141 (95% UI, $8038-$8258) for White (non-Hispanic) individuals, who accounted for an estimated 72% (95% UI, 71%-73%) of health care spending. After adjusting for population size and age, White individuals received an estimated 15% (95% UI, 13%-17%; P < .001) more spending on ambulatory care than the all-population mean. Black (non-Hispanic) individuals received an estimated 26% (95% UI, 19%-32%; P < .001) less spending than the all-population mean on ambulatory care but received 19% (95% UI, 3%-32%; P = .02) more on inpatient and 12% (95% UI, 4%-24%; P = .04) more on emergency department care. Hispanic individuals received an estimated 33% (95% UI, 26%-37%; P < .001) less spending per person on ambulatory care than the all-population mean. Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) individuals received less spending than the all-population mean on all types of care except dental (all P < .001), while American Indian and Alaska Native (non-Hispanic) individuals had more spending on emergency department care than the all-population mean (estimated 90% more; 95% UI, 11%-165%; P = .04), and multiple-race (non-Hispanic) individuals had more spending on emergency department care than the all-population mean (estimated 40% more; 95% UI, 19%-63%; P = .006). All 18 of the statistically significant race and ethnicity spending differences by type of care corresponded with differences in utilization. These differences persisted when controlling for underlying disease burden.

Conclusions and Relevance

In the US from 2002 through 2016, health care spending varied by race and ethnicity across different types of care even after adjusting for age and health conditions. Further research is needed to determine current health care spending by race and ethnicity, including spending related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study examines health care spending for 6 race and ethnicity groups across 6 types of care—ambulatory, emergency, inpatient, nursing facility, prescribed pharmaceuticals, and dental—from 2002 through 2016 in the US.

Introduction

Black and Indigenous individuals and other people of color face significant barriers to obtaining quality health care services in the US.1 Inequalities by race and ethnicity in access to care have been attributed to variation in insurance coverage2; socioeconomic and geographic inequities that affect health and access to health care3,4; and structural, institutional, and interpersonal racism within the health care system.5,6 These barriers to health care utilization and treatment reflect and perpetuate structural racism in US society more broadly.7

Prior research has documented variation in health care spending by race and ethnicity.8,9,10 On average, health care spending has been shown to be higher for White individuals than for individuals in other race and ethnicity groups. White individuals also receive more care or spending than other groups for specific conditions such as arthritis10 and the treatment of high cholesterol.11 Many relevant studies were conducted prior to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act,12,13 which may have affected patterns in insurance coverage.2,14,15 In addition, little research has adequately considered age or the type of care when comparing health care spending by race and ethnicity. Age is a known driver of spending, and adjusting for differences in the age distribution of different groups is necessary for valid comparison.

The objective of this study was to estimate health care spending for 6 race and ethnicity groups from 2002 through 2016 in the US. The study focused on differences in spending across 6 types of care (ambulatory, emergency, inpatient, nursing facility, prescribed pharmaceuticals, and dental). It assessed whether differences in utilization or differences in price and intensity accounted for differences in spending, and it also assessed whether spending differences persisted even after controlling for the number of people with specific health conditions.

Methods

Overview

This analysis followed 5 steps.

1. Data reporting health care spending; volume of care; type of care; health condition; year of service; and the age, sex, and self-reported race and ethnicity of the individual receiving care were extracted from household surveys.

2. Nonlinear regression was used to estimate the fraction of health care spending and volume of care (separately). This was done in aggregate and for specific health conditions, 19 age groups, both sexes, and 6 types of care. The nonlinear model smoothed across age and time to prevent problems associated with small sample size.

3. For each age, sex, health condition, type of care, and year, the fraction of spending and fraction of care were multiplied by previously estimated outputs from the Disease Expenditure project,16 in order to estimate health care spending and volume of care for each category.

4. For each race and ethnicity group, total and age–standardized health care spending per person were calculated, as was spending per notified case for 7 key health conditions.

5. Differences in health care spending across race and ethnicity groups were decomposed into 2 factors: (1) utilization and (2) price and intensity of treatment.

All spending estimates are reported in inflation-adjusted 2016 US dollars, and collectively sum to the total health care spending for all 6 types of care. The Disease Expenditure project received review and approval from the University of Washington institutional review board, but because the data were from a deidentified database, the requirement for informed consent was waived. The present study falls under the Disease Expenditure project and its institutional review board decision. This study complies with the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER).17 The subsections below summarize our methods; additional detail is provided in the Supplement.

Data Sources

Self-reported race and ethnicity, age, sex, insurance coverage, knowledge of having key health conditions, and information about health system encounters (visits, admission, or prescriptions), diagnoses, and health care spending were extracted from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (2002-2016), the National Health Interview Survey (2002; 2016), and the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (2002-2012). Each of these surveys had at least 5 race categories and, separately, 2 Hispanic ethnicity categories that respondents self-selected. Collectively, this information was used to assign each respondent to 1 of 6 mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive race and ethnicity groups: American Indian or Alaska Native (non-Hispanic); Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic); Black (non-Hispanic; referred to as Black); Hispanic; multiple race (non-Hispanic; referred to as multiple race); or White (non-Hispanic; referred to as White). These categories align with the US Office of Management and Budget’s 1997 “Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity,” and are statistical race and ethnicity categories—meaning that they are constructed from self-reported survey questions for the purpose of guiding policy. Race and ethnicity are socially constructed concepts, and not biological. This study combined Asian (including Asian and Asian American) and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander groups in order to ensure sufficient sample sizes for each category and to align with the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, which also combined those categories. Health care spending is inclusive of spending from all payers, including private insurance, public insurance, and out-of-pocket spending.

Estimates on spending by condition came from the Disease Expenditure project.16 The Disease Expenditure project split health care spending from the 6 types of care into 154 health conditions, age and sex groups, and payer, for 1996 through 2016,16,18,19,20,21,22 though it did not split spending by race and ethnicity groups. That research drew from microdata capturing 150.4 million ambulatory, dental, or emergency department visits; 1.5 billion inpatient and nursing care facility bed-days; and 5.9 million prescribed pharmaceuticals across 198 sources of data. The Disease Expenditure project adjusted spending estimates for comorbidities and tracked spending comprehensively for the 6 types of care and total spending (across payers, age and sex groups, and health condition) and aggregated to the official spending estimates published in the National Health Expenditure Accounts.23 That research has estimated spending, rather than the cost or value of care, and is designed to align with the health condition taxonomy developed by the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD).24 Population estimates for the years of this analysis come from the GBD 2019.25

Estimating Health Care Spending by Race and Ethnicity Fractions

To address problems associated with small samples, race and ethnicity–specific spending estimates were measured as a fraction of age- and year-specific total spending, for each age, sex, year, and health condition and were regressed on penalized age and year splines, as well as a covariate that measured the fraction of the population in each race and ethnicity group (for each age group and year). This was done independently for each of the 6 race and ethnicity groups, 154 health conditions, as well as for aggregate health condition categories that capture spending on all cardiovascular diseases or all health conditions, and 6 types of care. The modeled age-, condition-, type of care-, and year–specific spending fractions, which estimate the fraction of spending on each race and ethnicity group, were multiplied by the commensurate spending from the Disease Expenditure project to generate an estimate of the race and ethnicity–specific spending (for each age, condition, type of care, and year category).16 To estimate health care utilization rates for each race and ethnicity group, this process was repeated using the number of visits (for ambulatory care, emergency department care, and dental care, separately), admissions (inpatient care), or prescriptions filled.

Age Standardization

Because the age distribution of the population in each race and ethnicity group varies, direct age-standardization was used to age-standardize per-person health care spending estimates. The all-race age profile from 2016 was the reference population.

Decomposing Differences in Health Care Spending

Health care spending per person was analyzed in relation to 2 factors: (1) health care utilization (ie, per-person visits, admissions, or prescriptions) and (2) price and intensity of care (ie, spending per visit, per admission, or per prescription). To evaluate the degree to which each of these factors accounted for differences in age-standardized spending per person across race and ethnicity groups, age-standardized spending per person was decomposed using Das Gupta decomposition.26 The decomposition analysis was not completed for nursing facility care spending because utilization estimates for this type of care were not available.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for the analysis was age-standardized health care spending for each type of care (ambulatory, emergency, inpatient, nursing facility, prescribed pharmaceuticals, and dental) and for each race and ethnicity group. Additional outcomes of interest included nonstandardized spending estimates, spending specific to health condition per notified case, and the fraction of spending differences that were attributable to differences in utilization. Notified cases are defined as individuals who reported through the National Health Interview Survey that a clinician had diagnosed them with a health condition (except for low-back and neck pain, which did not require a professional diagnosis). Spending per notified case is reported on the following health conditions: (1) cardiovascular diseases (including atherosclerotic vascular diseases, heart failure, valvular disease, infections of the heart, and arrhythmias), (2) cerebrovascular diseases, (3) diabetes, (4) low-back and neck pain, (5) asthma, (6) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and (7) hypertension. Of the 154 health conditions in the Disease Expenditure project in 2020, these 7 conditions were selected for analysis because notified case estimates were available through the National Health Interview Survey, and the conditions were prevalent enough that disaggregating by race and disease did not result in prohibitively small sample sizes.

Reporting and Uncertainty

The coefficient of variation was calculated to quantify variation in spending levels among race and ethnicity groups. Estimates could not be made past 2016 because the underlying Disease Expenditure data do not go past 2016. Reported uncertainty intervals (UIs) were from a percentile bootstrap. These were estimated by bootstrapping the underlying data 1000 times and completing each part of the analysis 1000 independent times. The survey data used to calculate the race and ethnicity–specific spending and volume of care fractions and the underlying Disease Expenditure project data were bootstrapped, using the same methods that incorporated the complex survey design associated with each data set. The estimates reported in this study are the mean of these 1000 estimates, with the 95% UIs estimated as the range from the 2.5th to the 97.5th percentiles of the 1000 estimates. A 2-sided bootstrap P value with an α of .05 was used to calculate which race and ethnicity spending and utilization estimates were different from the all-population mean.27,28 Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings of the analyses should be interpreted as exploratory.

All data management, analyses, and visualizations were completed using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp), Python version 3.8.5 (Python Software Foundation), and R version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Health Care Spending by Race and Ethnicity Across Time and Age

This study included $29.9 trillion in health care spending from 2002 through 2016 across 6 types of care (Figure 1). Data informing disaggregation of this spending were drawn from surveys reporting on 7.3 million visits, admissions, or prescriptions, as well as on previous estimates of total health care spending for the same years.

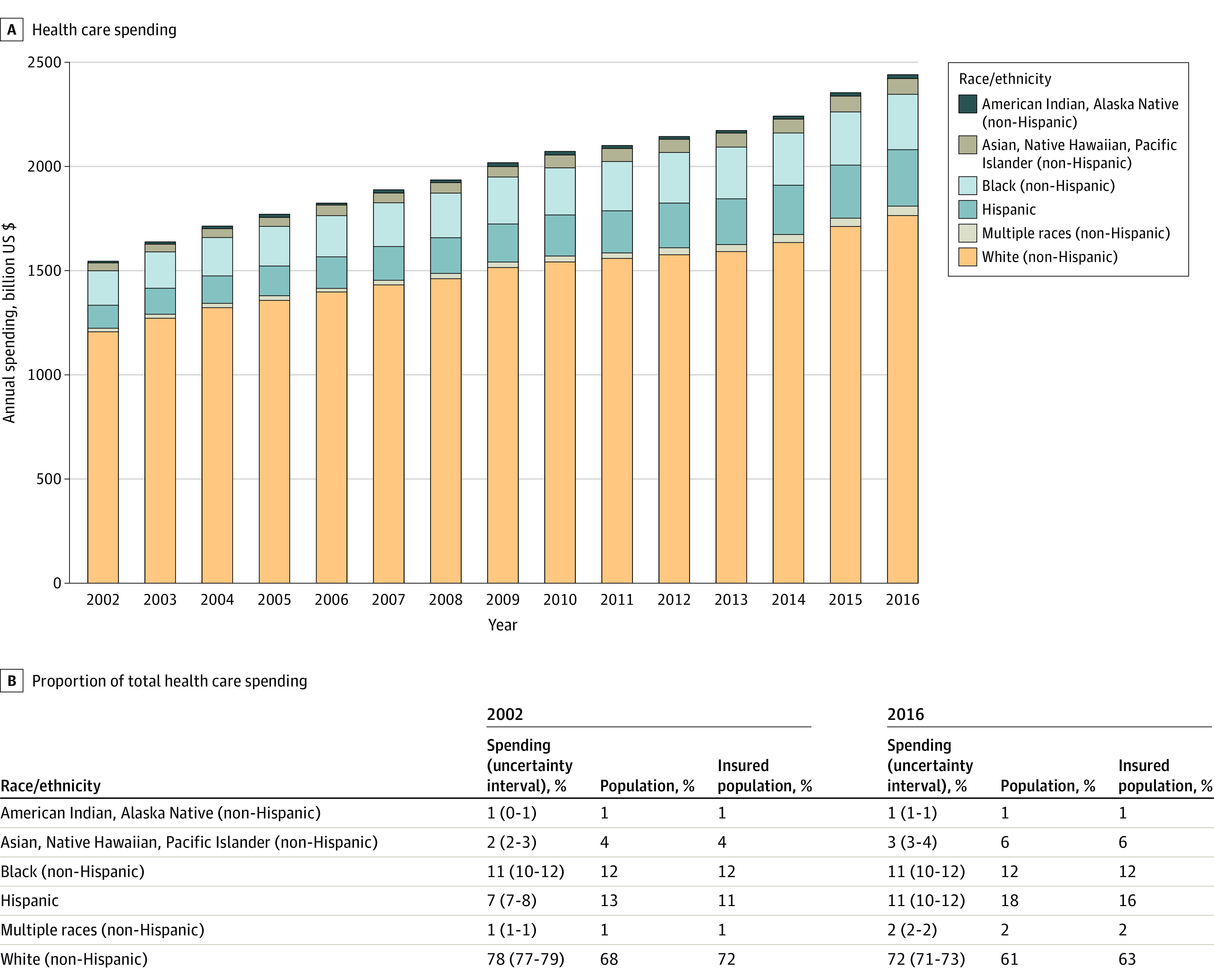

Figure 1. Estimated Health Care Spending by Race and Ethnicity From 2002 Through 2016.

A, Total health care spending for 6 mutually exclusive race and ethnicity groups in the US from 2002 and 2016. B, The proportion of total spending, the total US population, and the total US insured population in each race and ethnicity group. Uncertainty intervals were based on completing the analysis on 1000 independently bootstrapped samples of the underlying data.

In 2016, an estimated $2.4 trillion (95% UI, $2.4 trillion-$2.4 trillion) was spent on health care across the 6 types of care that were included in this study. In 2016, 61% of the US population was White (Figure 1) and an estimated 72% (95% UI, 71%-73%) of total health care spending was on White individuals. Meanwhile, 18% of the population was Hispanic and received an estimated 11% (95% UI, 10%-12%) of included health care spending. Black individuals were 12% of the population and received an estimated 11% (95% UI, 10%-12%) of health care spending. Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander individuals were 6% of the population and received an estimated 3% (95% UI, 3%-4%) of health care spending. Multiple-race individuals were 2% of the population and received an estimated 2% (95% UI, 2%-2%) of health care spending. The smallest category of health care spending was on American Indian or Alaska Native individuals, with an estimated 1% (95% UI, 1%-1%) of total spending. This group made up 1% of the population in 2016. Figure 1 also shows that the disproportionally large amount of spending on White individuals existed in 2002 as well. These differences could not be explained simply by rates of insurance coverage.

In per-person terms, estimated health care spending was largest for White individuals, and for each race and ethnicity group, mean per-person spending increased with age (Table). After adjusting for the fraction of each race and ethnicity group living in each 5-year age group, per–person health care spending levels by race and ethnicity had smaller differences across the 6 groups. The most spending per person in 2016 were an estimate of $9276 (95% UI, $8066-$10 601) for multiple race individuals, $8141 (95% UI, $8038-$8258) for White individuals, $7649 (95% UI, $6129-$8814) for American Indian and Alaska Native individuals, and $7361 (95% UI, $6917-$7797) for Black individuals. Hispanic individuals accounted for the next largest amount of spending, with an estimated $6025 (95% UI, $5703-$6373). Spending on Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander individuals was estimated at $4692 (95% UI, $4068-$5202) per person in 2016. The coefficient of variation in the Table shows that the variation in per-person spending was greatest for adults aged 45 through 64 years and least for individuals younger than 20 years, and was smaller when adjusting for age.

Table. Estimated Age-Specific, All-Age, and Age-Standardized Health Care Spending per Person by Race and Ethnicity in 2016a.

| Race and Ethnicity (non-Hispanic) | Spending per person, $ US (95% UI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-19 y | 20-44 y | 45-64 y | ≥65 y | All ages | Age standardized | |

| American Indian, Alaska Native | 2677 (1856-3441) | 5150 (3963-6691) | 10 746 (8415-12 616) | 15 518 (11 166-20 936) | 6919 (5641-8069) | 7649 (6129-8814) |

| Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander | 2488 (1565-3474) | 3496 (3031-4229) | 5381 (4510-6252) | 9602 (8074-11 324) | 4444 (3886-4895) | 4692 (4068-5202) |

| Black | 2791 (2023-3432) | 4287 (3776-4779) | 9168 (8322-9908) | 17 905 (16 521-19 224) | 6546 (6112-6991) | 7361 (6917-7797) |

| Hispanic | 2803 (2348-3241) | 3522 (3276-3787) | 7000 (6327-7624) | 14 403 (13 051-15 776) | 4682 (4413-4971) | 6025 (5703-6373) |

| Multiple races | 3816 (2925-5427) | 5750 (4238-6663) | 12 566 (9406-16 292) | 19 249 (14 765-22 823) | 6423 (5494-7313) | 9276 (8066-10 601) |

| White | 3423 (3155-3680) | 5425 (5224-5616) | 10 419 (10 187-10 643) | 18 532 (18 126-18 901) | 8941 (8827-9059) | 8141 (8038-8258) |

| Coefficient of variation, % | 21 (9-40) | 23 (17-29) | 29 (23-39) | 24 (18-29) | 27 (24-29) | 23 (18-29) |

Uncertainty intervals (UIs) were based on completing the analysis on 1000 independently bootstrapped samples of the underlying data. Spending is reported in 2016 US dollars per person. The coefficient of variation indicates dispersion relative to the mean. A larger coefficient of variation means a relatively larger amount of variation.

Age-Standardized Health Care Spending by Race and Ethnicity by Type of Care, 2016

In 2016, estimated age-standardized health care spending per person also varied by race and ethnicity across all 6 types of care assessed (Figure 2). The most relative variation in spending were for nursing facility care (coefficient of variation, 54% [95% UI, 38%-69%]), emergency department care (coefficient of variation, 40% [95% UI, 25%-59%]), and dental care (33% [95% UI, 23%-44%]) .

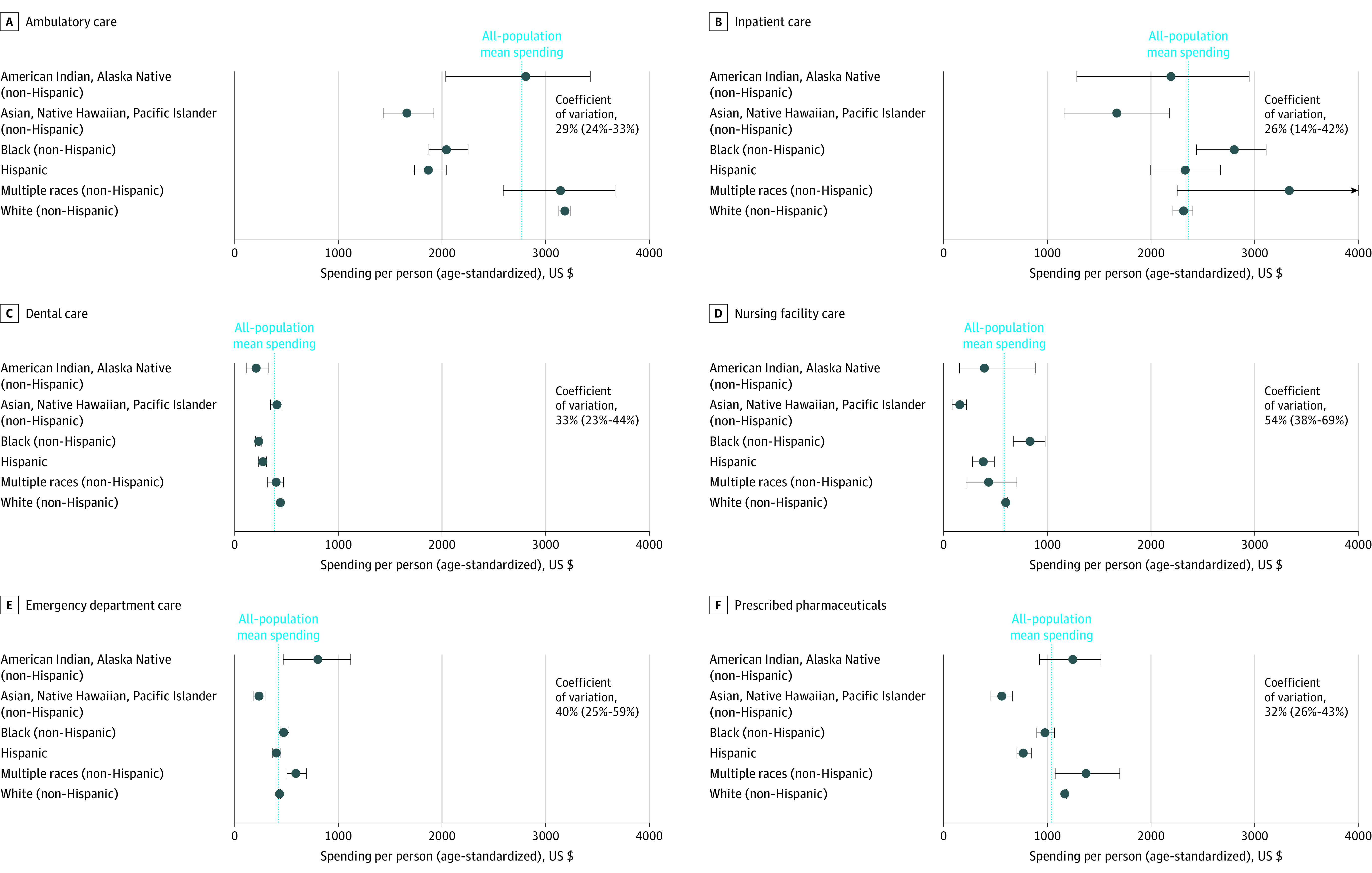

Figure 2. Estimated Age-Standardized Health Care Spending per Person by Race and Ethnicity and Type of Care in 2016.

Error bars indicate 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs). UIs were based on completing the analysis on 1000 independently bootstrapped samples of the underlying data. The coefficient of variation indicates dispersion relative to the mean. A larger coefficient of variation means a relatively larger amount of variation. Values in parentheses represent uncertainty intervals for each coefficient of variation. Types of care are mutually exclusive.

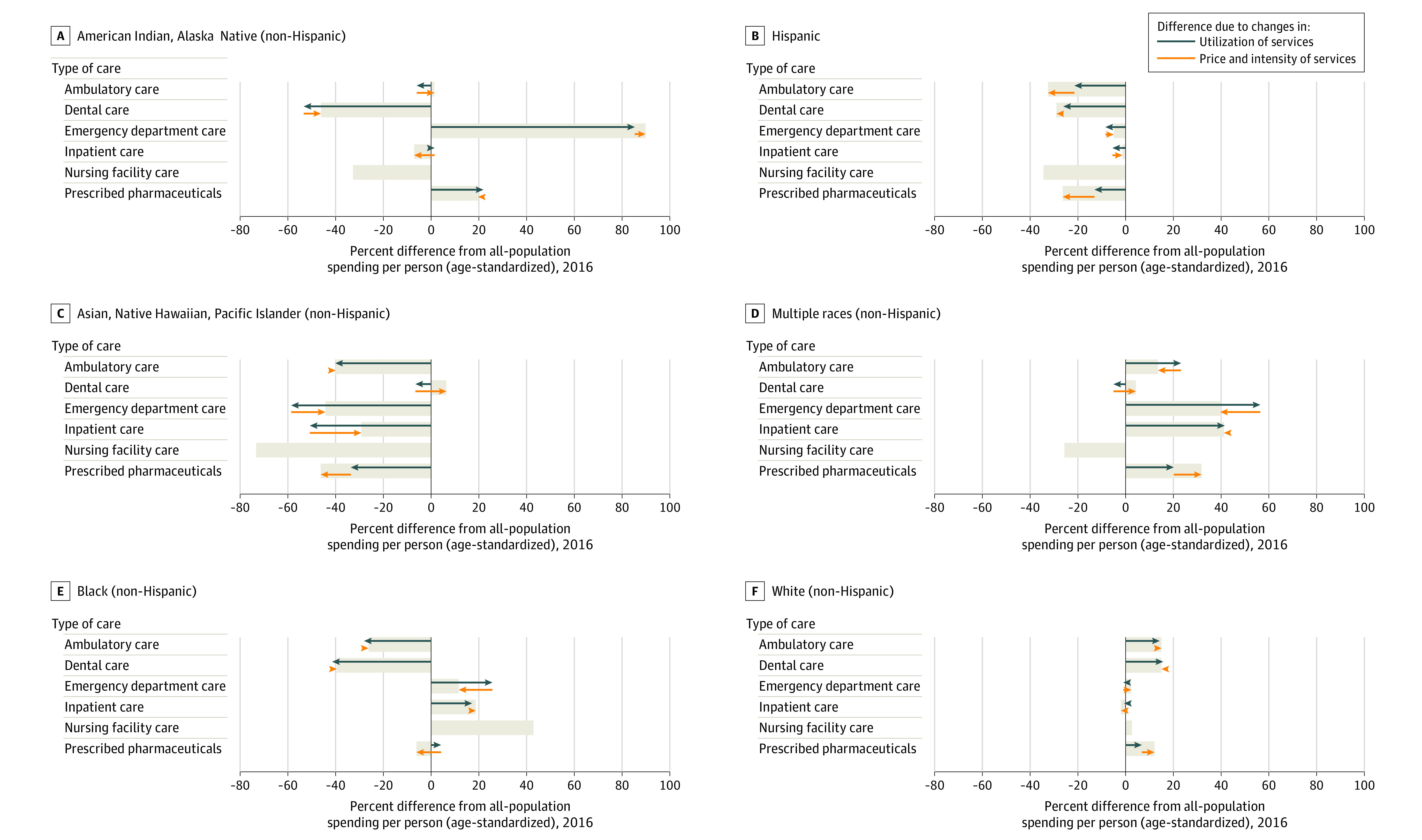

Figure 3 provides information about factors that account for differences in age-standardized health care spending for each type of care. Emergency department spending on American Indian or Alaska Native individuals was an estimated 90% (95% UI, 11%-165%; P = .04) more per person (age-standardized) than the all-population mean. This additional spending was accounted for primarily by additional utilization of emergency department care, while mean spending per visit was similar to the all-population mean. American Indian or Alaska Native individuals had an estimated 46% (95% UI, 16%-71%; P < .001) less spending per person on dental care than the all-population mean, which was accounted for primarily by less utilization.

Figure 3. Age-Standardized Spending per Person Attributable to Utilization and Price and Intensity of Services in 2016.

Each bar represents the relative difference in spending for each group, relative to all-population spending for each type of care. Types of care are mutually exclusive. Green arrows indicate the relative differences attributed to differences in utilization, while the orange arrows indicate the relative difference attributed to differences in price and intensity of treatment. Decomposition was not performed for nursing facility care due to the lack of utilization data for this type of care. The corresponding dollar amounts by race and type of care can be found in Figure 2.

Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander individuals had the least amount of estimated spending per person on each type of care relative to the other race and ethnicity groups, except for dental care. Spending on this group for nursing facility care was an estimated 73% (95% UI, 62%-86%; P < .001) lower than the all-population mean; moreover, the estimated spending was lower than the all-population spending levels for emergency department care (44% [95% UI, 31%-58%]; P < .001), ambulatory care (40% [95% UI, 31%-48%]; P < .001), prescribed pharmaceuticals (46% [95% UI, 36%-56%]; P < .001), and inpatient care (29% [95% UI, 8%-51%]; P < .001). For all types of care in which decomposition was completed except dental care, the mean use of services for Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander individuals was significantly less than the all-population means (all with P < .001).

For Black individuals, there was an estimated 26% (95% UI, 19%-32%, P < .001) less spending on ambulatory care and 40% (95% UI, 32%-47%, P < .001) less on dental care than the all-population mean. Black individuals had an estimated 19% (95% UI, 3%-32%; P = .02) more spending per person on inpatient care, 12% (95% UI, 4%-24%; P = .04) more on emergency department care, and 43% (95% UI, 15%-68%; P = .02) more on nursing facility care than the all-population mean spending levels. These differences were primarily accounted for by different rates of utilization of each type of care.

Hispanic individuals had significantly less estimated spending per person (relative to the all-population mean) for ambulatory care, 33% (95% UI, 26%-37%; P < .001); dental care, 29% (95% UI, 20%-39%; P < .001); nursing facility care, 34% (95% UI, 16%-52%; P < .001); and prescribed pharmaceuticals, 26% (95% UI, 19%-32%; P < .001). For all types of care, the differences from the all-population means were accounted for primarily by less use of services.

The multiple-race group had more estimated spending on all types of care except for nursing facility care, after adjusting for age, relative to the all-population means. These differences were statistically significant for prescribed pharmaceutical spending (32% higher; 95% UI, 3%-63%; P = .04) and emergency department care (40% higher; 95% UI, 19%-63%; P = .006). As for other race and ethnicity groups, additional utilization of each type of care accounted for most of this variation.

White individuals’ spending had estimates higher than the all-population mean for ambulatory care, 15% (95% UI, 13%-17%; P < .001); dental care, 15% (95% UI, 11%-19%; P < .001); and prescribed pharmaceuticals, 12% (95% UI, 10%-14%; P < .001). Higher utilization accounted for these differences.

Health Care Spending by Race and Ethnicity per Notified Case, 2016

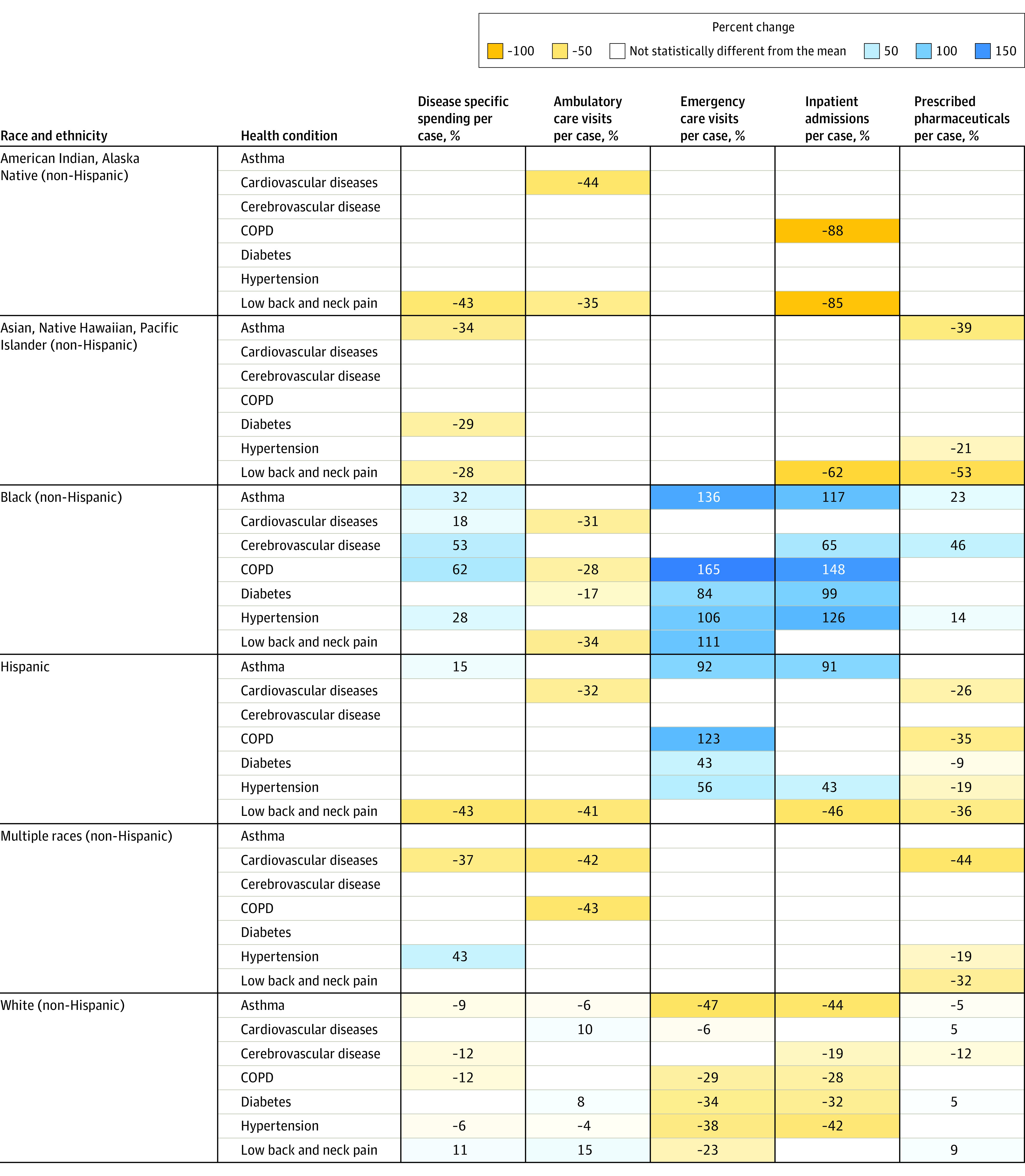

While Figure 3 shows that health care spending differences were attributable to different levels of utilization across race and ethnicity groups, Figure 4 reports where and how spending and utilization differed significantly per notified case. Patterns highlighted in Figure 3 remained when considering estimated spending per notified case for specific health conditions. The race and ethnicity groups with the most statistically significant differences from the all-population mean were Black and White individuals (partially because of large sample sizes in the underlying data, relative to the other race and ethnicity groups, and therefore more certain estimates; see Figure 4 for point estimates for statistically significant differences). For asthma, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and COPD, Black individuals had statistically significantly more spending per notified case. All statistically significant differences for Black individuals showed they had less utilization per notified case for ambulatory care, and more utilization per notified case for prescribed pharmaceuticals and especially inpatient care and emergency department care. White individuals had statistically less spending per notified case for asthma, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, and hypertension and statistically significantly more spending per notified case on low back and neck pain. For all health conditions with statistically significant differences, White individuals had lower utilization per notified case in inpatient and emergency department care, and generally more utilization per notified case for ambulatory care and prescribed pharmaceuticals.

Figure 4. Statistically Significant Differences in Estimated Health Care Spending and Utilization in 2016.

Each cell reports the relative difference of spending or utilization rates per notified case, comparing that specific race or ethnicity group and the condition-specific all-population mean for the population aged 20 years or older. Cells without values reported indicate where estimates were repressed because the differences from the all-population mean were not statistically significant (α = .05). Dental care was omitted because these conditions are not treated as part of dental care. Nursing facility care was omitted due to a lack of utilization data. The corresponding estimates of relative differences in spending per utilization by type of care can be found in eTable 6B in the Supplement. In addition, eTable 6A presents these estimates as absolute differences in dollars and utilization counts rather than percent differences. COPD indicates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

This study found statistically significant differences in estimated health care spending across 6 race and ethnicity groups, with differences present for total spending, age-standardized spending, spending by type of care, and health-condition-specific spending per notified case. After adjusting for age, per-person health care spending was highest in 2016 for multiple race, White, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Black individuals. Estimated spending for White individuals was higher for ambulatory care, while spending for Black individuals was higher on emergency, inpatient, and nursing facility care. These differences were primarily accounted for by differences in utilization. Estimated per-person spending relative to the all-population mean was less for Hispanic individuals than for Black individuals and White individuals across all service types except dental care. Spending per person was lowest for Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander individuals.

In this study, spending differences could not be explained by accounting for the number of individuals in each race and ethnicity group who had been diagnosed with a health condition. When health-condition-specific spending per notified case was assessed, the general spending patterns described persisted. White individuals had more utilization of ambulatory care and prescribed pharmaceuticals per notified case, while Black individuals generally had higher utilization per notified case of inpatient and emergency department care. This finding calls for further examination of the role of delayed health care-seeking, potentially due to lack of access.

One contribution of this study was to adjust for differences in the age structure of each race and ethnicity group. This adjustment was done to ensure that differences in spending were not due to the fraction of the population in each group that was older. Age-standardization is essential for comparisons across race and ethnicity groups. Still, there is also value in the non–age-standardized spending levels presented in Figure 1. For example, health care spending per person was highest for White individuals, a group that also on average lives longer than individuals in some other groups. Nonstandardized spending estimates per person show that for Black individuals and American Indian and Alaska Native individuals, the groups with some of the shortest life expectancies,29,30 health care spending is significantly less. More investment in prevention and health promotion for these groups may lead to more equitable spending levels and could improve health outcomes.

Differences in utilization accounted for most of the differences in spending per person. Lower utilization rates of ambulatory care and higher rates of inpatient, emergency department, and nursing care for Black individuals suggest that Black individuals may lack access to the ambulatory care that can play a critical role in prevention. This finding reinforces previous research showing unequal access to primary care.13,31 The US is consistently the wealthiest country in the world with subpar levels of coverage for a core set of health services32; these findings provide additional evidence of the need to reduce disparities.

This study provides evidence of spending and utilization differences across race and ethnicity groups that cannot be explained by differences in the age or notified health status of the individual. Thus, it provides evidence that supports a broad literature that has identified factors that perpetuate health care inequalities by race and ethnicity, from how physicians respond to patients to bias that exists in the algorithms that assess health needs and determine appropriate interventions.5,33 In addition, differences in access have also been explained in part by residential segregation that precludes easy access to health care services.4 Differences in quality of care by race and ethnicity, in part driven by the underrepresentation of some groups in the health care workforce, including Black and Hispanic or Latino physicians, may also contribute to hesitation in accessing care.34 Furthermore, even though price differences were not large across groups, the larger proportion of those who are uninsured among Black and Hispanic individuals means that these individuals have faced a greater financial burden to pay for these services.35 Lower-income households, which are disproportionately composed of people of color, may not have the resources to obtain preventive care even when they have health insurance due to time constraints (job does not allow for time off) and out-of-pocket costs for travel or co-pay.

Ultimately, there are many mechanisms that have already been identified that explain how structural racism shapes health and health care.6,7,36 Quantifying differences in health care spending and utilization can help to shed light on the scope of some disparities by race and ethnicity. Further research is needed to assess these disparities and the drivers and structural forces that produce them. Efforts to improve health care should be accompanied by attention to the range of factors that perpetuate longstanding disparities in health and health outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, data limitations restricted some aspects of this analysis. Prevalence or notified case rates of most health conditions by race and ethnicity were not available. Data also did not distinguish whether care was initiated by patients or recommended by physicians or other types of clinicians. For some types of care- or health condition–specific analyses, sample size may have been too small to establish statistical significance. Second, the landscape of race and ethnicity in the US is dynamic, and the 6 race and ethnicity categories used in this study do not fully reflect this dynamism. Furthermore, the categories bundle distinct groups, likely with distinct health care utilization and spending patterns.37 Third, this study did not disaggregate spending by race and ethnicity and payer, which would have made it possible to better understand the role of insurance coverage and out-of-pocket expenditure. Access to private insurance is not equitable across key race and ethnicity groups, and insurance coverage is known to drive differences in utilization.31 Fourth, because disease expenditure inputs did not include estimates beyond 2016, this study did not generate estimates for a more recent period. Additional research is needed to assess health care spending by race and ethnicity in more recent years. Research on patterns in health care spending by race and ethnicity in 2020-2021 will be important for understanding utilization and treatment in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has already been shown to exacerbate already existing health inequalities.38 Fifth, this study was not able to measure the value of care provided. It is possible that the value of care could vary in ways different from health care spending.

Conclusions

In the US from 2002 through 2016, health care spending varied by race and ethnicity across different types of care even after adjusting for age and health conditions. Further research is needed to determine current health care spending by race and ethnicity, including spending related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary Methods and Results

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. The National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipton BJ, Decker SL, Sommers BD. The Affordable Care Act appears to have narrowed racial and ethnic disparities in insurance coverage and access to care among young adults. Med Care Res Rev. 2019;76(1):32-55. doi: 10.1177/1077558717706575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):325-334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White K, Haas JS, Williams DR. Elucidating the role of place in health care disparities: the example of racial/ethnic residential segregation. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 pt 2):1278-1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01410.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, Johnson TJ. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:219-229. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and US health care. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:7-14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook BL, Manning WG. Measuring racial/ethnic disparities across the distribution of health care expenditures. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(5 pt 1):1603-1621. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01004.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lê Cook B, McGuire TG, Zuvekas SH. Measuring trends in racial/ ethnic health care disparities. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(1):23-48. doi: 10.1177/1077558708323607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spector AL, Nagavally S, Dawson AZ, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Examining racial and ethnic trends and differences in annual healthcare expenditures among a nationally representative sample of adults with arthritis from 2008 to 2016. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):531. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05395-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salami JA, Warraich H, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. National trends in statin use and expenditures in the US adult population from 2002 to 2013: insights from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(1):56-65. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Escarce JJ, Kapur K. Racial and ethnic differences in public and private medical care expenditures among aged Medicare beneficiaries. Milbank Q. 2003;81(2):249-275, 172. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Cohen JW. Racial and ethnic differences in access to and use of health care services, 1977 to 1996. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(suppl 1):36-54. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchmueller TC, Levinson ZM, Levy HG, Wolfe BL. Effect of the Affordable Care Act on racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1416-1421. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Mortensen K, Ortega AN. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care access and utilization under the Affordable Care Act. Med Care. 2016;54(2):140-146. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, et al. US health care spending by payer and health condition, 1996-2016. JAMA. 2020;323(9):863-884. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. ; The GATHER Working Group . Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet. 2016;388(10062):e19-e23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dieleman JL, Baral R, Birger M, et al. US spending on personal health care and public health, 1996-2013. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2627-2646. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieleman JL, Squires E, Bui AL, et al. Factors associated with increases in US health care spending, 1996-2013. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1668-1678. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.15927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolnick HJ, Bui AL, Bulchis A, et al. Health-care spending attributable to modifiable risk factors in the USA: an economic attribution analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(10):e525-e535. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30203-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamavid H, Birger M, Bulchis AG, et al. Assessing the complex and evolving relationship between charges and payments in US hospitals: 1996–2012. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0157912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dieleman JL, Baral R, Johnson E, et al. Adjusting health spending for the presence of comorbidities: an application to United States national inpatient data. Health Econ Rev. 2017;7(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13561-017-0166-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . National health expenditure data. Modified December 17, 2019. Accessed March 14, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData

- 24.Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, et al. ; GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators . Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204-1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H, Abbas KM, Abbasifard M, et al. ; GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators . Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950-2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1160-1203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30977-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das Gupta P. Standardization and Decomposition of Rates: A User’s Manual. US Bureau of the Census; 1993:23-186. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; 1994. doi: 10.1201/9780429246593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boos DD. Introduction to the bootstrap world. Statistical Science. 2003;18(2):168-174. doi: 10.1214/ss/1063994971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Center for Health Statistics . Health, United States, 2019—data finder: Figure 001. Reviewed March 2, 2021. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2019.htm

- 30.Dankovchik J, Hoopes MJ, Warren-Mears V, Knaster E. Disparities in life expectancy of Pacific Northwest American Indians and Alaska natives: analysis of linkage-corrected life tables. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(1):71-80. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuvekas SH, Taliaferro GS. Pathways to access: health insurance, the health care delivery system, and racial/ethnic disparities, 1996-1999. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(2):139-153. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development . Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. Revised May 2020. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2019_4dd50c09-en

- 33.Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447-453. doi: 10.1126/science.aax2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A, Jones KE. The association of doctor-patient race concordance with health services utilization. J Public Health Policy. 2003;24(3-4):312-323. doi: 10.2307/3343378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Health Interview Survey . Persons files from NHIS, 2002-2016. Published December 2, 2020. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm

- 36.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):105-125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponce NA. Centering health equity in population health surveys. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(12):e201429. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrasfay T, Goldman N. Reductions in 2020 US life expectancy due to COVID-19 and the disproportionate impact on the Black and Latino populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(5):e2014746118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014746118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Methods and Results