Abstract

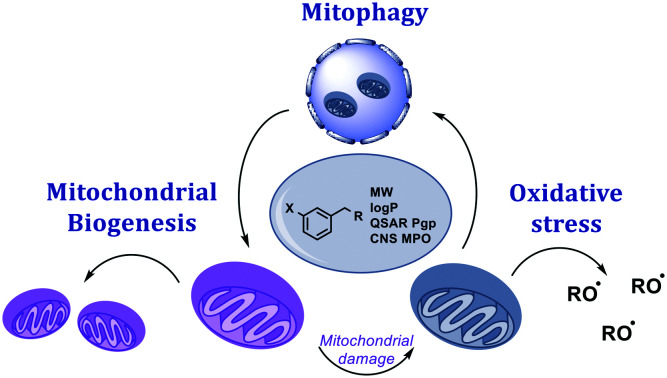

Mitochondria are subcellular organelles that perform a variety of critical biological functions, including ATP production and acting as hubs of immune and apoptotic signalling. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been extensively linked to the pathology of multiple neurodegenerative disorders, resulting in significant investment from the drug discovery community. Despite extensive efforts, there remains no disease modifying therapies for neurodegenerative disorders. This manuscript aims to review the compounds historically used to modulate the mitochondrial network through the lens of modern medicinal chemistry, and to offer a perspective on the evidence that relevant exposure was achieved in a representative model and that exposure was likely to result in target binding and engagement of pharmacology. We hope this manuscript will aid the community in identifying those targets and mechanisms which have been convincingly (in)validated with high quality chemical matter, and those for which an opportunity exists to explore in greater depth.

This manuscript reviews the compounds historically used to modulate mitochondria, and offers a perspective on which targets have been convincingly (in)validated with high quality chemical matter and those which remain untested.

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases (ND) such as Alzheimer's Disease (AD), Parkinson's Disease (PD), and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS, also called Motor Neuron Disease) each affect distinct regions of the brain.1 Despite having clearly distinct pathologies and patient prognoses, all these conditions are characterised by the progressive loss of functional neurons. The massive societal burden of these conditions has necessitated significant research into the pathological mechanisms underlying neuronal decline, which has identified a small number of common pathways that are implicated across multiple diseases.

After many decades of clinical observations and genetic associations,2 an abundance of evidence has accumulated that shows that neuronal function is highly sensitive to the health of the mitochondrial network.

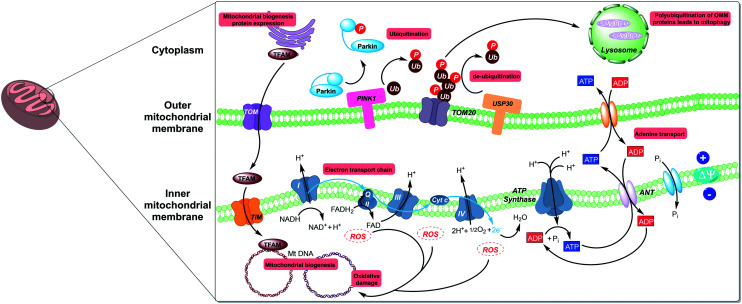

The biology of mitochondria has been extensively reviewed elsewhere,3,4 and so will not be discussed here in detail. In brief, mitochondria are small organelles that perform a variety of functions within the cell, and primary amongst them is generation of ATP by oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 1).5

Fig. 1. Mitochondrial biology is governed by both mitochondrial and nuclear genes with key regulators spread throughout the cell. The three areas detailed in this review; mitochondrial biogenesis, mitophagy, and oxidative stress have points of intervention in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM).

The factors underlying the neuronal sensitivity to mitochondrial dysfunction are still emerging, but there is a consensus that neurons are highly metabolically active (in part, the high energy demand sustains signalling across long axons),6,7 and the trafficking of mitochondria to and from the cell soma has been shown to be critical for healthy neuronal function.8 In addition, neurons have also been shown to be disproportionately reliant on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation for energy production;9,10 this is in contrast to non-neuronal CNS cell populations such as astrocytes, which display a reliance on glycolytic pathways for energy production; however, this has been debated.10 Finally, neurons are post-mitotic cells and therefore are unable to divide; this inability to ‘dilute’ cell contents means that neurons are differentially sensitive to aggregates,10,11 exemplified by Lewy bodies in PD, which are significantly composed of dead or damaged mitochondria.10

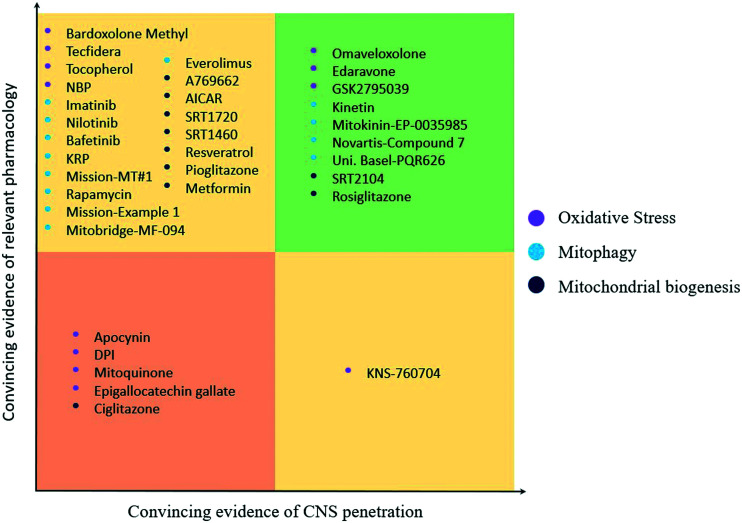

As a consequence of this association between the mitochondrial network and neuronal function, modulators of mitochondria have been extensively evaluated for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders for over 30 years.12 Indeed, multiple agents have advanced to clinical trials designed to assess this mechanism in patients. Despite the large number of trials,13 there are no approved disease-modifying drugs for ND and those approved for symptomatic treatment function via mechanisms distinct to improving mitochondrial health. The plethora of unsuccessful trials makes it tempting to conclude that mitochondrial modulators are unlikely to provide a meaningful impact to patients' lives. An alternative explanation for the unsuccessful clinical validation is that the molecules used to test the biological hypothesis in the clinic were not suitable to do so. Firstly, designing a molecule with properties such that relevant free exposures can be obtained in the CNS is not trivial. The lack of ability to sample directly from the CNS compartment in patients means that extensive pharmacokinetic modelling and/or biomarker validation is often required to demonstrate target engagement, to confirm that the mechanism has been sufficiently engaged. Secondly, in many cases the molecular mechanism of action (MoA) of the test agent was not known, or the data supporting the proposed MoA were not robust. This lack of confidence in exposure at the target site of action, target occupancy, or proof of mechanistic pharmacology makes the drawing of meaningful conclusions from proof of concept studies extremely challenging.14

The goal of this review is to assess the compounds used historically to modulate the mitochondrial network through the lens of modern medicinal chemistry practices. For the exemplified compounds, we will assess the evidence that relevant exposure was achieved in a representative model, and that exposure was likely to result in target binding and engagement of pharmacology. In 2010, Wager et al. published a Multiparameter Optimisation (MPO) scoring function that can be used to assess the probability of a compound achieving CNS exposure. This heuristic is a composite of 6 physicochemical properties (molecular weight, log D7.4, log P, pKa, polar surface area and number of hydrogen bond donors) which provides a score in the range of 0–6; the authors showed that a score of >4 correlated with increased clinical success for the Pfizer CNS portfolio.15 The ‘CNS MPO’ has proven very popular for molecular design, in part due to its intuitive nature. More recently, a Bayesian approach to the CNS MPO (probabilistic MPO, or pMPO) has been published which weights individual parameters by importance, and scores compounds from 0 to 1 (where a higher score is indicative of improved CNS properties).16 This method is more statistically robust, but lacks the intuitive nature of the original MPO score; MPO scores will be calculated for the compounds discussed herein, with the goal of adding context when experimental information is not available. Details of the models and parameters used can be found in the ESI.† Where high quality compounds are progressing through preclinical assessment that may enable a new perspective on the biological mechanism, we will aim to highlight these in this manuscript.

We would like to acknowledge that many of the compounds assessed in this review contain structure features annotated as Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINs).17 PAINs are chemical motifs which are known to frequently produce false positive results in screening experiments, often by mechanisms such as fluorescence interference, aggregation or redox cycling. The data derived from PAIN-containing compounds should be treated with caution, and confirmed with orthogonal screening methodologies. We have avoided specifically labelling compounds in this review as PAINs, in part as many of the compounds are anti-oxidants and therefore the PAIN functionality is integral to their reported pharmacological mechanism of action. As an alternative approach, we have attempted to collate and review the reported pharmacology and to provide a contextualised perspective on each compound.

We hope that this analysis will assist the community in identifying studies where the biological hypothesis was effectively tested by the molecule in question, and those in which the molecule was not fit for purpose. We will focus on the three areas which have been most extensively studied in the field of mitochondrial health: mitochondrial biogenesis, mitophagy and oxidative stress.

Mitochondrial biogenesis

Most existing therapies that aim to ameliorate mitochondrial health in degenerative diseases seek to prevent mitochondrial dysfunction or reduce oxidative stress; these strategies may be insufficient to aid recovery following mitochondrial injury. In order to fill this gap, significant research has been undertaken to therapeutically modulate mitochondrial homeostasis; through either upregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis (MB), the processes through which cells can increase their mitochondrial mass, or mitophagy, the processes by which dysfunctional mitochondria are degraded.

There is mounting evidence supporting MB as a mechanism in the treatment of ND.18–20 Multiple NDs show links to decreased mitochondrial mass. Moreover, impaired MB has been shown to be present in both AD and PD; the primary intracellular mechanism for this is believed to be the inhibition of the AMPK–SIRT-1–PGC-1α pathway by various pathogenic protein aggregates.21–25 In several AD models, both genetically and chemically induced, the MB transcriptome has been shown to be suppressed.26 MB induction and subsequent increase in mitochondrial mass, either from existing mitochondria (fission) or through the generation of new functional mitochondria, has been shown to promote repair and regeneration in cells following injury; i.e. toxin exposure, ischemic reperfusion and inflammation.27–29 Compounds that promote MB alleviate cellular dysfunction and, more promisingly, promote organ repair, represent exciting opportunities for new therapeutics.

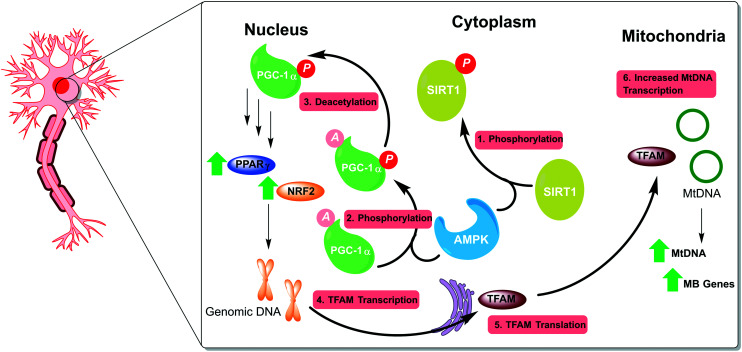

MB is governed by several genes spread across both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), providing multiple opportunities for therapeutic intervention; the AMPK–SIRT-1–PGC-1α pathway being the most commonly targeted. 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) functions as a regulator of cellular energy homeostasis, modulated by the cellular AMP/ATP ratio i.e. plentiful ATP will lead to AMPK inhibition. AMPK phosphorylates the histone/protein deacetylase SIRT1, which, in turn, deacetylates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), a master transcriptional co-activator for many of the genes responsible for MB (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The AMPK–SIRT-1–PGC-1α pathway is a well-established target for triggering MB. AMPK is stimulated by a high cytosolic AMP : ATP ratio leading to phosphorylation of both the deacetylase SIRT1 and the transcriptional co-activator PGC-1α. SIRT1 deacetylates the pPGC-1α, which allows it to stabilise and upregulate various nuclear transcription factors, including PPARγ and NRF2. Activation of nuclear MB genes by PPARγ leads to expression and translocation of TFAM to the mitochondria, where mitochondrial MB genes are activated.

AMPK

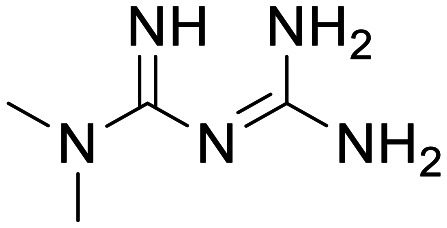

Metformin

There have been several attempts to target AMPK for activation with the goal of potentiating MB, these can be split broadly into indirect and direct interactions. Through lowering of the intracellular ATP : AMP ratio, some indirect AMPK activators exploit the protein's AMP-sensing capability to trigger the pathway. The most prominent example from this class is the biguanide metformin, an approved drug in the treatment of various conditions, including type 2 diabetes. Metformin is a known inhibitor of complex 1 and has been shown to increase intracellular AMP concentrations, which gives rise to an increase in AMPK activity.30 Metformin has been shown to lower α-synuclein phosphorylation and reduce neuronal death in rodent 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced (MPTP) PD models,31,32 and more recently underwent investigation for AD treatment in a phase 2 trial.33 The trial measured Aβ40 and pTau levels in CSF and cognitive ability using Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive sub scale (ADAS-COG); whilst a minimal change in AD biomarkers (Aβ1–42; total Tau and pTau) were observed and there was no significant effect in measures of language or motor speeds, a statistically significant improvement in one measure of executive function was observed over placebo. Moreover, the compound showed a good safety profile despite a relatively high dosing regimen necessitated by uncertain mechanism of action and short half-life. CNS exposure was achieved, yet ambiguous biology complicates the development path of metformin for treatment of ND.33

Of the compounds designed to interact with AMPK directly, two stand out as having the most well-established mechanism of action; A769662 and AICAR.

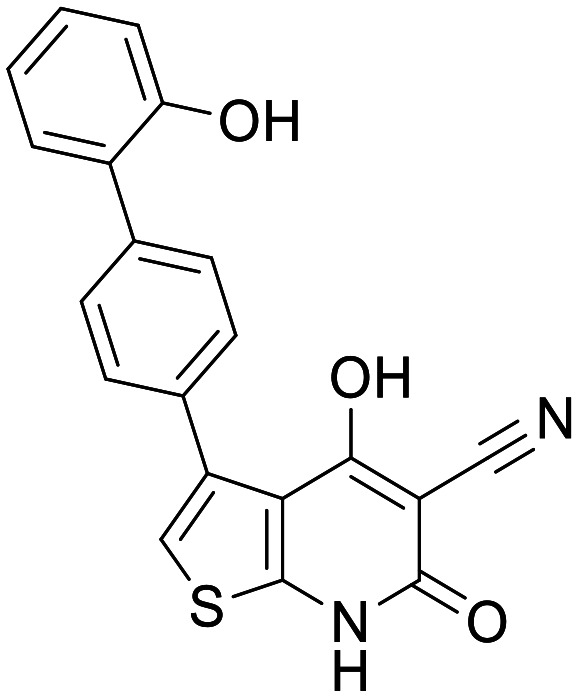

A769662

The Abbott/Novartis molecule A769662 was the lead compound developed from a thienopyridine series of AMPK activators. A769662 functions by binding reversibly in an allosteric site between the alpha and beta subunits of AMPK resulting in activation of the pathway and prevention of T172 dephosphorylation.34 Although initially developed for use in the treatment of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, its attractive properties for blood brain barrier (BBB) penetration and its ability to induce MB in several cell lines, merited its consideration in the treatment of ND.35 A769662 was also shown to promote clearance of α-synuclein aggregates through activation of AMPK, albeit as a result of increased autophagy, not MB.36 A769662 has been shown to have significant activity in several voltage gated sodium channels, while this has been investigated with a view to its use as a potential analgesic, it does raise concerns for potential selectivity and ion channel-related safety issues.37 Overall the thienopyridine-based molecule is a promising pharmacophore with potency shown against AMPK in several tissues and cell lines.34 While there is no PK data assessing its CNS penetration, there have been efforts to optimise A769662 for oral bioavailability for the treatment of diabetes. A769662 shows poor oral bioavailability, and measured permeability however, optimisation of the structure throughout the course of the study led to an improvement in bioavailability.38 It should be noted that total AUC for A769662 and several of its analogues was much higher when administered in conjunction with Pgp inhibitor GF120918, suggesting the potential for efflux by Pgp. A769662 has not yet been trialled in the clinic, however it has the potential to serve as the basis for several optimisation studies and currently functions as a useful in vitro tool compound.

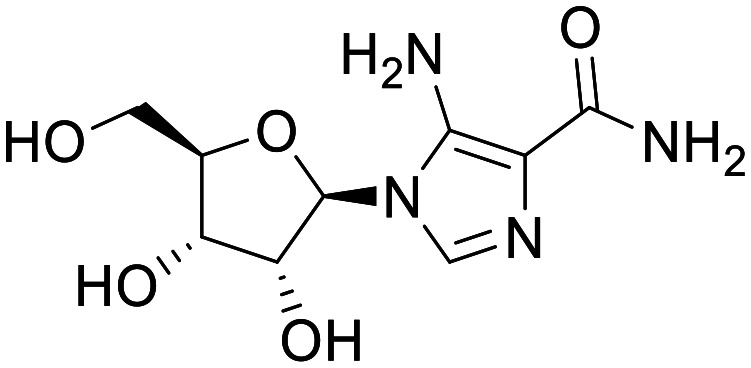

AICAR

5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside (AICAR), is interchangeably described as an indirect and direct activator of AMPK, owing to its pro-drug-like mechanism of action.39 The adenosine analogue AICAR is transported into cells and readily phosphorylated into AICAR-monophosphate (ZMP), which is itself an AMP mimetic. ZMP binds directly to the AMPKγ domain with weaker affinity than AMP, however, ZMP has been shown to accumulate up to millimolar levels within the cytosol providing a competitive environment for AMP.39 Clinical data for AICAR is limited; a pilot study was conducted for the treatment of Lesch-Nyhan disease in 1995, with inconclusive results. The study was carried out for a single patient; and while the drug was seemingly well tolerated, no efficacy was reported.40 However, there have been many studies showing the capacity of AICAR to stimulate MB and exhibit neuroprotective effects in several in vitro and in vivo models. Intracerebroventricular-streptozotocin (STZ) injected rodents that underwent ischemic injury, showed improved recovery with respect to behavioural measures, as well as a reduction in pTau.41,42 Moreover, in both palmitate- and retinoic acid-treated SH-SY5Y cells, AMPK activation with AICAR has been shown to reduce the production of Aβ and pTau.43,44 PK data on AICAR is currently limited, however, its ability to effect change in key models and its biomimetic mechanism of action warrant further study to assess its ability to trigger MB in the CNS.

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Metformin

|

AMPK | Cognitive impairment alleviation in MPTP rodent model, human ADAS-COG measured improvement in clinical trials | 95.6 ng mL−1 (741 nM) Cmax in human CSF following 500 mg QD to 1000 mg BID over 8 weeks (oral) | 5.12 | 0.17 |

A769662

|

AMPK | In vitro activation of AMPK in HEK cells and with AMPK isolated from various tissues | None | 2.88 | 0.34 |

AICAR

|

AMPK | Reduction in pTau (STZ model, rodents) and alleviated cognitive impairment (ischemic injury, rodents) | None | 4 | 0.16 |

SIRT-1

The deacetylase silent mating type information 2 homologue 1 (SIRT1) is activated by AMPK, which in turn activates PGC-1α. Like AMPK it has been targeted several times, both directly and indirectly, with the aim to treat age-related diseases. Most attempts have been aimed at ameliorating diabetes-related mitochondrial injury, however SIRT1 as a target for treatment of ND has seen more attention in recent years.

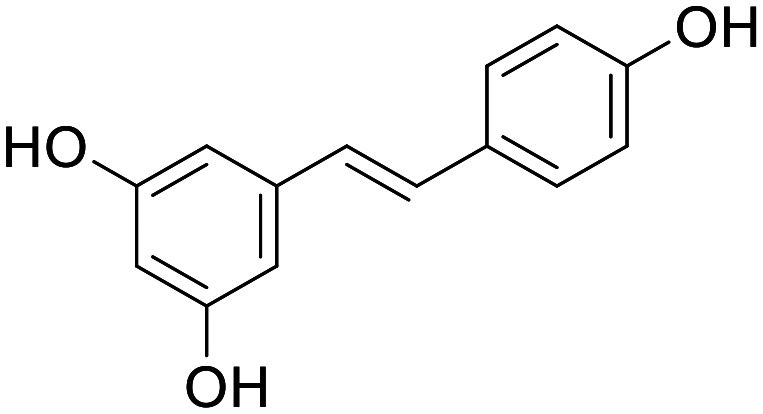

Resveratrol

The natural product resveratrol was first studied due to its presence in several foods, namely berries and grapes, broadly associated with longevity. While the evidence suggesting resveratrol-rich diets can improve lifespan is limited, there is evidence of resveratrol dosing leading to increased mitochondrial mass, believed to be as a result of increased mitochondrial biogenesis. Resveratrol is a molecule that hits multiple targets and engages multiple mechanisms.45 Although the precise mechanisms by which resveratrol drives MB are still not known, activation of SIRT1 is believed to be a contributing factor. This activation has been attributed to both direct binding to SIRT1, and indirect activation by AMPK following disruption of the electron transport chain through complex I and F1/F0 ATPase inhibition.46 It has also been suggested that resveratrol can directly activate both PPARα and PPARγ.47,48 While resveratrol efficacy is most commonly attributed to SIRT1 activation, it seems likely that the observed increase in MB is as a result of all the aforementioned interactions. Resveratrol has been shown to induce MB in many models of PD, AD, Huntington's disease (HD) and various types of neuronal injury, both in vitro and in vivo.49–53 Moreover, resveratrol has been subject to clinical trials for both PD (phase 1, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03093389) and AD (phase 2), in each case showing it is safe and well tolerated and, in the case of AD, small decreases in CSF levels of Aβ40 were recorded, however other measured parameters showed no significant change (Aβ42, Tau, pTau, ADAS-cog and hippocampal volume).54 In the same AD trial, PK analysis of resveratrol and its metabolites, 3-O-glucuronidated- (3GR), 4-O-glucuronidated- (4GR) and sulfonated-resveratrol (SR), was carried out, following 52 weeks dosing at 200 mg QD, revealing a low, yet measurable, mean CSF concentration for resveratrol and much higher CSF levels of 3GR, 4GR and SR (10×, 14× and 20× respectively). The relative levels of resveratrol to its metabolites in CSF was proportional to plasma levels albeit at much higher concentrations overall suggesting possible efflux at the BBB.54 There is clear evidence of desirable pharmacology by resveratrol, however, short half-life and possible efflux, resulting in limited CNS exposure, mean it will require further optimisation to provide a disease-altering treatment for ND.

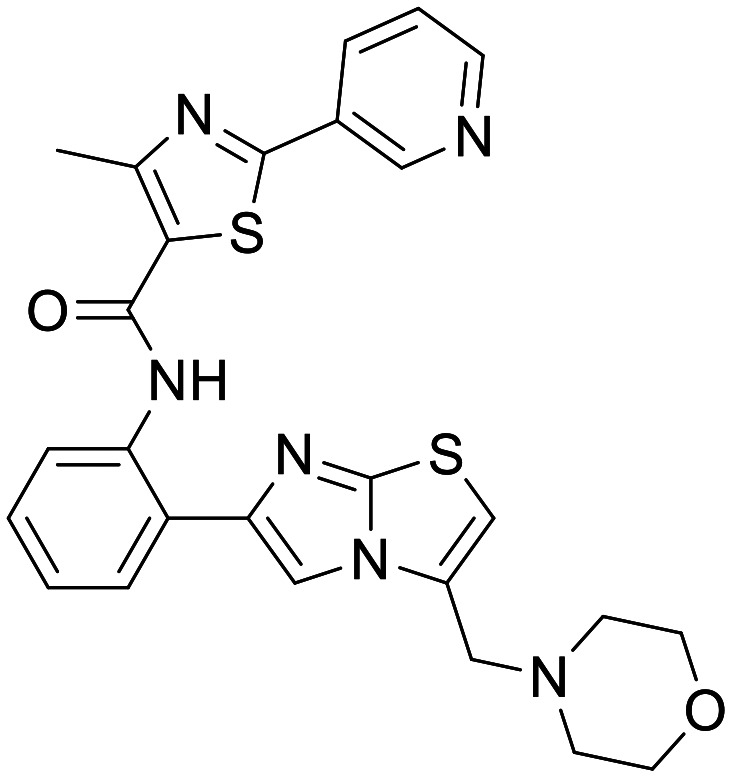

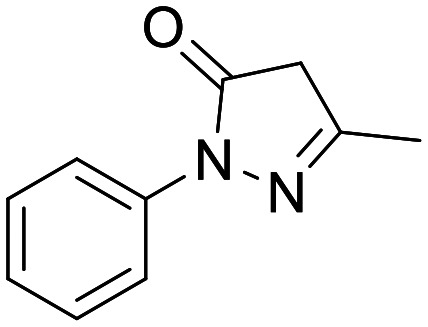

SRT series

A series of imidazothiazole-based derivatives have been the most prominent examples of direct SIRT1 activators, first identified in 2009 by Sirtris (now GSK) from a high throughput screen.55 The imidazole[1,2-b]thiazole core was optimised from an oxazolopyridine that gave an EC1.5 of 11 μM, where EC1.5 refers to the concentration at which enzyme activity is boosted by 50% over its normal activity (for comparison resveratrol has an EC1.5 of 46 μM in the same assay).55 The switch to the imidazole[1,2-b]thiazole yielded increased potency and an opportunity to further optimise the scaffold through substitution at the C2 and C3 positions. The bulk of the evidence for the resulting compounds, SRT1720 and SRT1460, was derived from a biochemical assay against a p53-derived peptide substrate tagged with a fluorophore (TAMRA). In 2010, while attempting to reproduce these results, Pfizer released surface plasmon resonance and BioNMR data suggesting that their activity was as a result of complexation between the compounds, SIRT1, the p53 peptide and the fluorophore, and that in the absence of the fluorophore, binding was minimal.56 GSK contested these results and produced data supporting the direct allosteric interaction of SRT1720 and SRT1460, and other analogues, with SIRT1.57 GSK continued to produce data in support of the series and their potential for use as SIRT1 activators; the proposed efficacy of these compounds is less controversial today.58–60 Further optimisation of the imidazole[1,2-b]thiazole-based scaffold eventually gave rise SRT2104, the most advanced molecule in the series, which has been subject to clinical trials for diabetes (and various other non-ND disorders) and has shown promising results in animal models for Huntington's.61 When SRT2104 was administered to N171-82Q HD mice, brain atrophy was attenuated and increased survival was recorded. Moreover, following a 0.5% SRT2104 containing diet for 6 months, brain tissue exposure of SRT2104 was measured, indicating CNS penetration.61 While the mechanism of action for the SRT series was unclear for much of its development, site-directed mutagenesis of E230 to lysine or alanine leads to loss of binding for several molecules in the SRT series, suggesting the residue is key to binding. This conclusion was further reinforced through hydrogen–deuterium exchange with the ligand-protein complex, showing E230 and its surrounding residues were shielded from exchange when bound to the SRT ligands.62 PK and safety data from its clinical trials, for non-ND disorders, indicate that SRT2104 is generally well tolerated and safe, and shows low oral bioavailability. However, there was significant variability in measured plasma Cmax. Due to the targeting of non-CNS disorders, none of the published SRT2104 trials provide PK data for CNS penetration.63 SRT2104 has a suboptimal MPO, which, in combination with limited oral bioavailability, make the likelihood of it achieving sufficient CNS exposure in humans low. However, further optimisation of the imidazolethiazole core could lead to a suitable molecule for triggering MB in the CNS.

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Resveratrol

|

SIRT1 | Several in vivo and in vitro models and reduction in Aβ in human PD patients | 0.45 ng mL−1 (1.97 nM) mean CSF (200 mg QD) | 4.6 | 0.55 |

SRT2104

|

SIRT1 | Several in vivo and in vitro models and animal HD models – namely N171-82Q HD mice | In mice following SRT2104 enriched diet terminal brain concentration of 2.23 ± 0.61 μM measured | 3.83 | 0.51 |

SRT1720

|

SIRT1 | Debated in vitro HD models, no clinical | None | 4.1 | 0.44 |

SRT1460

|

SIRT1 | Evidence of induced MB in vitro none in ND models, no clinical | None | 3.82 | 0.41 |

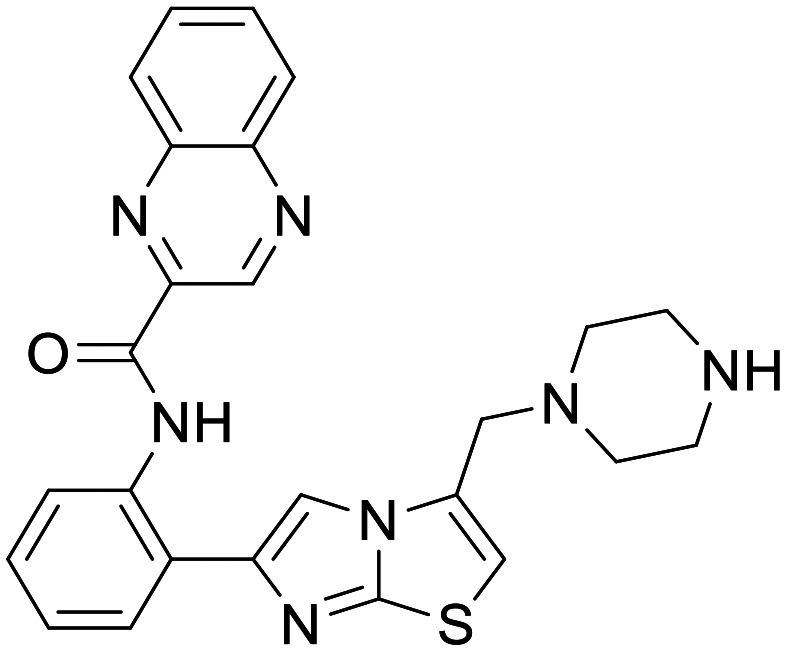

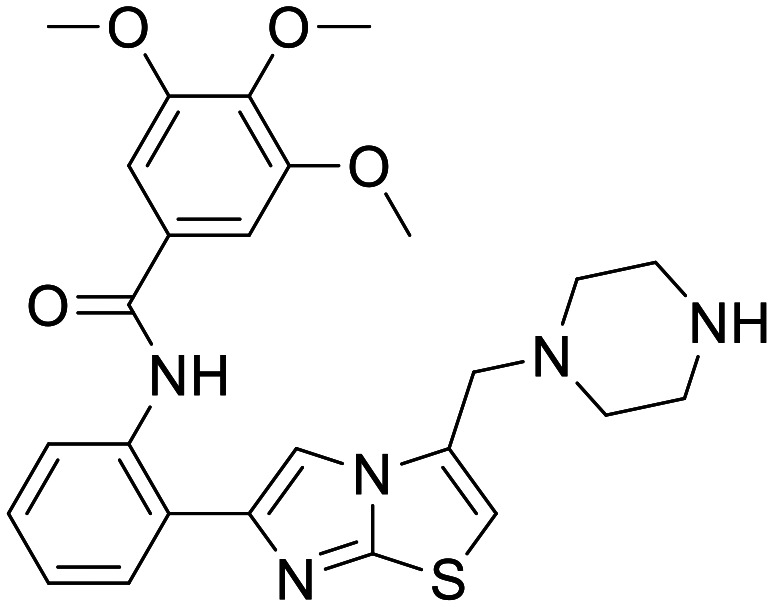

PGC-1α/PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator-1 alpha (PGC-1α) and its transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors-γ (PPARγ) are responsible for the downstream regulation of several genes involved in regulating MB; NRF2, UCP2, and PON2 amongst others. As such they represent another target along the AMPK–SIRT1–PGC-1α-dependent MB pathway for activation.

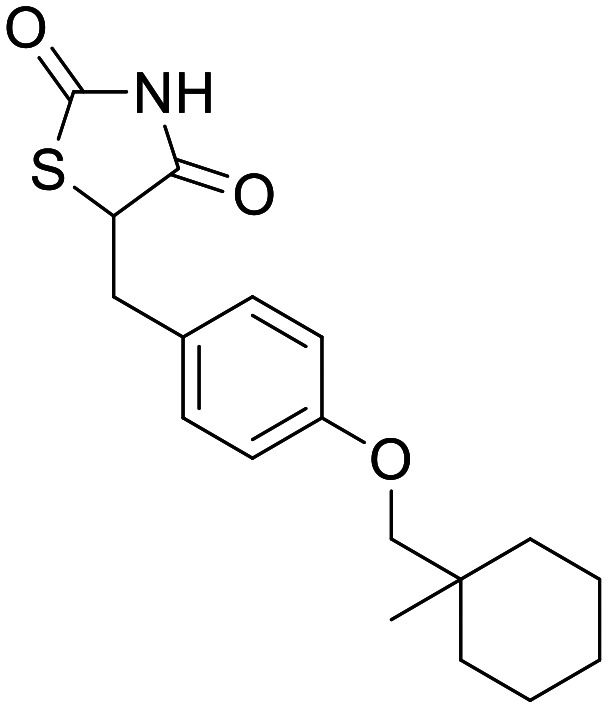

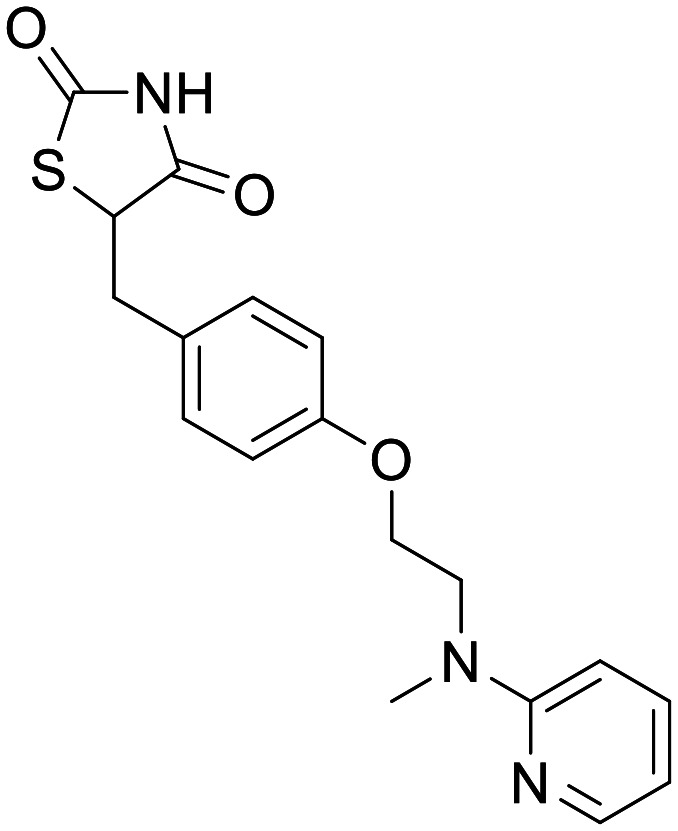

Thiazolidinediones

Chemical space used to design compounds to target PPARγ has been dominated by a class of benzyl-thiazolidinediones since the creation of the ciglitazone.64 Once again, the series was designed with diabetes as a primary indication to function as an insulin sensitiser. Since the initial creation of the series, rosiglitazone has emerged as the most potent analogue, bearing the same thiazolidinedione headgroup with an alkoxy linked amino pyridyl.65 Ciglitazone, and its more potent analogues, have been shown to rescue neuron function in several in vitro models of AD, HD and ischemic injury recovery.66–69 Moreover, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone have both shown improvement in preclinical cognitive impairment models.70–72 However, despite these drugs having been approved for use as insulin sensitisers in diabetics, their ability to treat ND remains uncertain. Pioglitazone has entered phase III trials for AD twice, yet in both instances the studies were terminated due to a lack of efficacy.25 Rosiglitazone has also entered phase III trials in several formulations, with mixed results where the primary outcomes have been measuring improvement of cognitive function. Given the proven efficacy of these compounds as insulin sensitisers and their ability to induce MB in various models, their lack of efficacy in patients is potentially attributable to poor CNS exposure. Despite numerous clinical trials for ND, the available data for rosiglitazone and pioglitazone CNS exposure in humans is limited. However, some evidence of CNS exposure by Rosiglitazone has been shown in gerbils who had undergone ischemic injury.73 It should be noted that CNS exposure for Rosiglitazone has not been recorded in naïve rodents, and exposure in this case could be due to compromise of the BBB following ischemic injury.

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ciglitazone

|

PPARγ | None in ND models – shown to induce MB in non-ND models | None | 4 | 0.82 |

Pioglitazone

|

PPARγ | In vitro and in vivo models, none in humans – recovery of neuronal function. Clinical trials show minimal efficacy | None | 5.57 | 0.87 |

Rosiglitazone

|

PPARγ | In vitro and in vivo models, none in humans – recovery of neuronal function. Clinical trials show minimal efficacy | In rodents only – Cmax 1.06 ± 0.28 μg mL−1 (2.96 μM) following 3 mg kg−1 IV dose | 5.82 | 0.87 |

Mitophagy, a potential therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases

Autophagy is a lysosome-dependent mechanism of intracellular degradation for maintaining cellular homeostasis by degrading damaged proteins. The process is characterised by the initial formation of a double-membrane vesicle, the autophagosome, which isolates components targeted for degradation. Following formation, fusion with the lysosome results in hydrolytic degradation of the target, the products of which are released for reuse.74

Mitophagy is a mitochondrial-specific autophagic clearance process and acts, at basal levels, to regulate the levels of mitochondria to address the metabolic requirements of the cell.75 This is achieved through a fine balance between MB and mitophagy of superfluous mitochondria.76 Under stress conditions, mitophagy targets dysfunctional or damaged mitochondria for degradation to address the manifestation of aberrant amounts of ATP and ROS which can prevent cellular degeneration and activation of cell death pathways.77

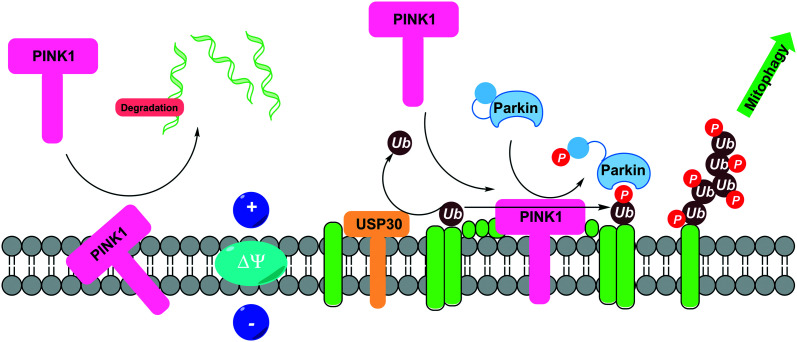

Regulating mitophagy is a relatively recent emerging mechanism for therapeutic interventions against diseases associated with aging, in particular ND.78 As such, the availability of highly advanced and validated small molecule modulators is limited. The following section aims to highlight the most recent and effective small molecule developments in this field (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy and its regulation through USP30 deubiquitination. Under basal conditions in healthy mitochondria, PINK1 is recruited to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) from the cytosol. PINK1 is cleaved by PARL and MPP and processed PINK1 is targeted for degradation. In damaged mitochondria, PINK1 is stabilised to the OMM where it phosphorylates parkin and ubiquitin. Phospho-ubiquitin recruits autophagy receptors to initiate autophagosome formation inducing mitophagy. USP30 negatively regulates PINK1/Parkin mediated mitophagy through reduction of ubiquitylation on OMM substrates.

PINK1 activators

To date, several pathways have been identified in mitophagy, but by far the most investigated and understood is the PINK1/Parkin pathway. PTEN-induced kinase 1, PINK1, is a mitochondrial serine/threonine protein kinase which becomes stabilised on the outer mitochondrial membrane following mitochondrial membrane depolarisation.79 PINK1 phosphorylates and recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin,80 at a conserved serine at amino acid 65 (pS65) in ubiquitin,81 leading to the ubiquitination of outer mitochondrial membrane proteins, signalling the defective mitochondria for degradation. The activation of PINK1 has been identified as a promising mitophagy target for neurodegenerative diseases.

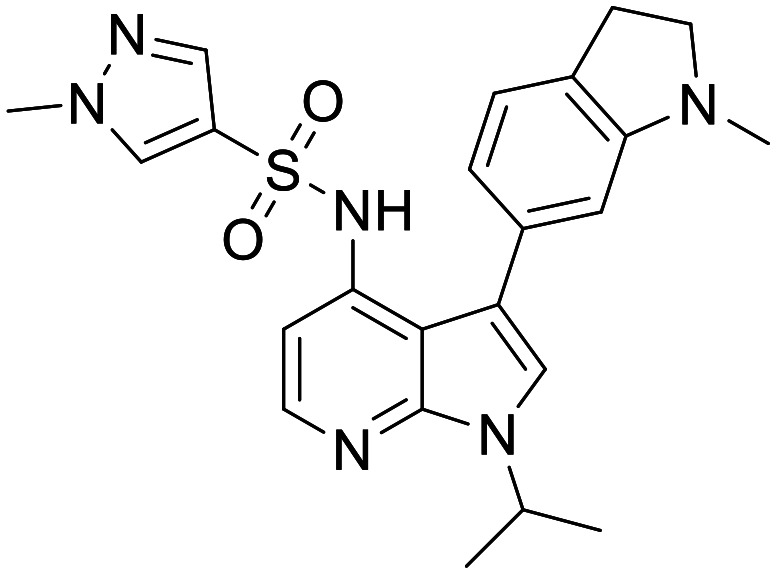

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kinetin

|

PINK1 activator | Restores deficient PINK1G309D catalytic activity to near-WT levels in vitro | Total brain concentrations of 639–3350 pg mg−1 (2.97–15.6 uM) in IKBKAP transgenic mouse lines, 400 mg kg−1 QD PO | 5.5 | 0.57 |

Kinetin riboside Protide (KRP)

|

PINK1 activator | Exhibits PINK1 activation in HEK293 cells stably expressing wild-type PINK1 | None | 3 | 0.03 |

Mitokinin-EP-0035985

|

PINK1 activator | Efficacy in α-syn amyloid fibril (PFF) mouse model | Mouse PK (10 and 50 mg kg−1 PO) shows total [brain] > [plasma] | 3.71 | 0.7 |

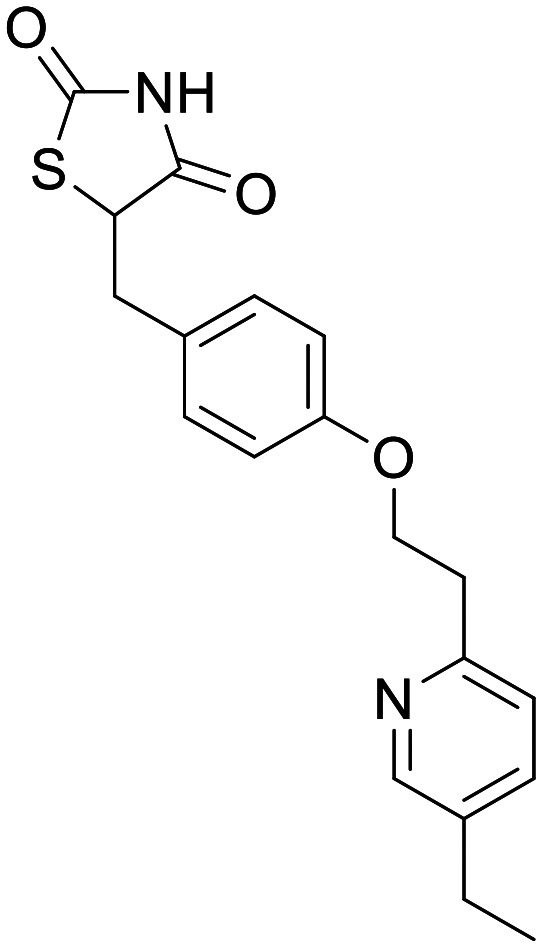

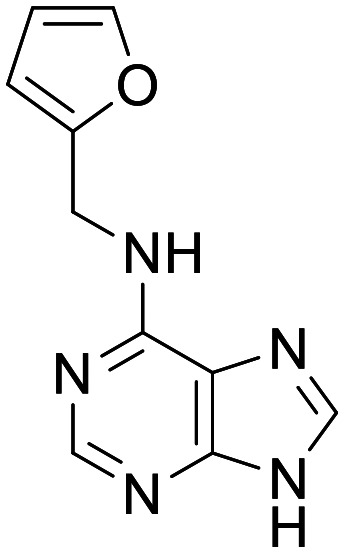

Kinetin

N6-Furfuryladenine, termed kinetin, has completed phase 1 clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02274051) for the treatment of familial dysautonomia (FD). Studies into the mechanism by which PINK1 is activated by kinetin revealed that kinetin was converted intracellularly in four consecutive metabolic steps to the active metabolite kinetin riboside triphosphate (KTP), which consequently acts as a PINK1 neosubstrate. PINK1G309D is one of the most common catalytic mutants of PINK1 and is associated with familial PD. This mutant shows a ∼70% decrease in kinase activity and abrogates the neuroprotective effect of PINK1. KTP showed enhancement of both PINK1WT and mutant PINK1G309D activity in vitro, and kinetin or KTP was capable of restoring deficient PINK1G309D catalytic activity to near-WT levels. Kinetin has shown to be safe and well tolerated by oral administration in both mouse models and in human clinical testing.82 FD and WT humanized IKBKAP transgenic mice dosed with kinetin showed average serum levels well above the effective concentration of kinetin in cell culture, and total brain concentrations suggesting moderate CNS penetration. It should be noted that kinetin is a plant hormone, and that although the evidence of kinetin acting on PINK1 is convincing, it is likely this compound induces multiple effects in a cellular context.83

Kinetin riboside protide (KRP)

Attempts to design Kinetin derived small molecule activators of PINK1 to avoid numerous bioactivation steps have resulted in the development of kinetin riboside protide prodrugs.84 It is proposed that cellular bioactivation of kinetin through glycosylation and phosphorylation are rate limiting steps. Protide technology has been employed to deliver a potent PINK1 activator, KRP, whilst simultaneously addressing issues around poor in vivo stability and cellular permeability associated with monophosphate compounds.

Pronounced activation of PINK1 by kinetin is only observed following co-incubation with the mitochondria depolarizing agent CCCP, KRP (50 μM) exhibits PINK1 activation in HEK293 cells stably expressing wild-type PINK1, co-transfected with untagged wild type Parkin in the absence of CCCP, where Parkin Ser65 phosphorylation was used as a readout for activity. Further studies show time-dependent activation of PINK1 with KRP, but this was observed to be less significant than treatment with CCCP alone. Further profiling of KRP is limited except for stability profiling in human and mouse serum showing good stability of parent molecule after 11 hours incubation. CNS MPO scores suggest that KRP exhibits physiochemical properties which are not conducive to a CNS drug-like molecule. As such it is likely that KRP would not be a suitable tool compound for a CNS indication.

Mitokinin-EP-0035985 (ref. 85)

Second generation Kinetin analogues have recently been reported by Mitokinin Inc. Mitokinin-EP-0035985 shows good in vitro potency in cellular assays of mitophagy (EC50 = 440 nM, HeLa mtKeima assay) with minimal cellular toxicity. In vivo mouse PK studies suggest that EP-0035985 has moderate oral bioavailability, however a Cmax sufficiently above the EC50 was only achieved at the highest dose. Tissue distribution studies at 10 and 50 mg kg−1 show that Mitokinin-EP-0035985 effectively distributes into the brain with total concentrations exceeding that of the plasma. Mitokinin-EP-0035985 has been progressed through a number of preclinical disease models. In the preformed α-syn amyloid Fibril (PFF) mouse model, EP-0035985 drives a decrease in α-synuclein at 50 mg kg−1 QD oral dose. The cisplatin mouse model of mitochondrial dysfunction showed oral dosing of Mitokinin-EP-0035985 at 20 to 50 mg kg−1 significantly reduces the expression of GDF15 as quantified by qPCR.

Deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) inhibitors

Deubiquitinating enzymes, DUBs, are a family of proteases that regulate ubiquitination through processing of ubiquitin adducts and cleavage of ubiquitin from proteins. Their function as a negative regulator of autophagy and mitophagy has identified small molecule inhibitors of these proteins as promising areas for drug development. Across all 99 mammalian DUBs, several targets in the subfamily of ubiquitin-specific peptidases (USPs) have been found to regulate mitophagy by antagonising parkin activity86 and have been identified as areas of interest for ND, the most promising and advanced being USP30.

USP30

USP30 is an outer mitochondrial membrane-localised cysteine protease, which has been identified as an antagonist of PINK1-parkin mediated mitophagy87 by regulating mitochondrial protein ubiquitination through cleavage of Lys6-linked polyubiquitin. Genetic studies have shown depletion of USP30 accelerates mitophagy and decreases ROS production, which supports the hypothesis that inhibition of USP30 leads to increased mitophagy.88

USP30 employs a Cys-His-Ser catalytic triad in its function of cleaving Lys-6 linked polyubiquitin.89 The most commonly employed approach towards the development of USP30 inhibitors focusses on targeting the catalytic Cys77 with a cyanamide covalent warhead. In recent years, there have been a number of notable reports that outline the development of covalent inhibitors, including Amgen Inc., Forma Therapeutics and Mission Therapeutics. Interestingly, these small molecules follow a generalised structure of a cyanamide warhead linked to a functionalised biaryl unit via an amide bond. The two most highly characterised USP30 covalent inhibitors, both from Mission therapeutics, are reported below.

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mission-MT#1

|

USP30 inhibitor | In vitro inhibition of USP30. Efficacy in non-CNS related preclinical models | None | 5.15 | 0.55 |

Mission-example 1

|

USP30 inhibitor | In vitro inhibition of USP30. Efficacy in non-CNS related preclinical models | In vivo target engagement studies in mouse brain (2 mg kg−1 IV at 15/60 min) | 5.3 | 0.6 |

Mitobridge-MF-094

|

USP30 inhibitor | In vitro inhibition of USP30. Induction of mitophagy in C2C12 myotubes | None | 1.69 | 0.11 |

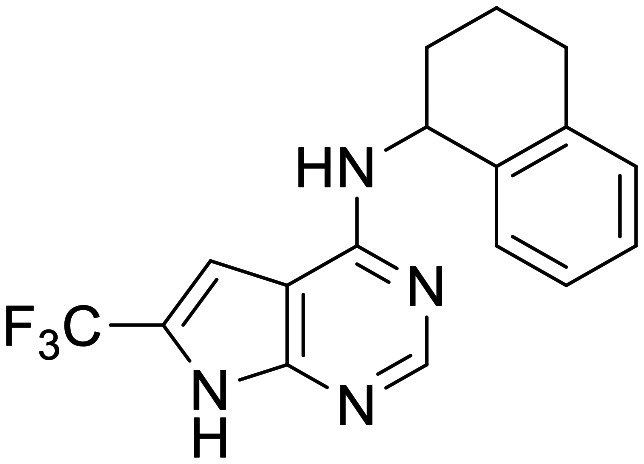

Mission-MT#1 (ref. 90)

In 2019 Mission therapeutics reported Mission-MT#1 as a highly potent USP30 inhibitor (IC50 = <0.01 μM, biochemical assay). Whilst there is no reported data on Mission-MT#1 to interrogate the in vitro or in vivo PK parameters, Mission-MT#1 has been progressed into several preclinical disease models. In the Bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis model, treatment with Mission-MT#1 resulted in a dose dependent reduction in fibrosis, with a statistically significant effect observed at 50 mg kg−1 BID. In the Unilateral ureteral obstructive kidney disease model (ULIO) treatment with Mission-MT#1 a statistically significant decrease in collagen deposition as measured by picrosirius red staining was observed at 15 and 50 mg kg−1 BID. However, in the diet-induced model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Mission-MT#1 did not significantly improve fibrotic stage scores in treated animals. Progression of Mission-MT#1 in to models of ND is noticeably absent. Whilst MT#1 has shown in vivo efficacy in disease models of mitochondrial dysfunction, its suitability for CNS indications is unclear. The physiochemical properties of Mission-MT#1 are consistent with desired CNS drug-like chemical space.

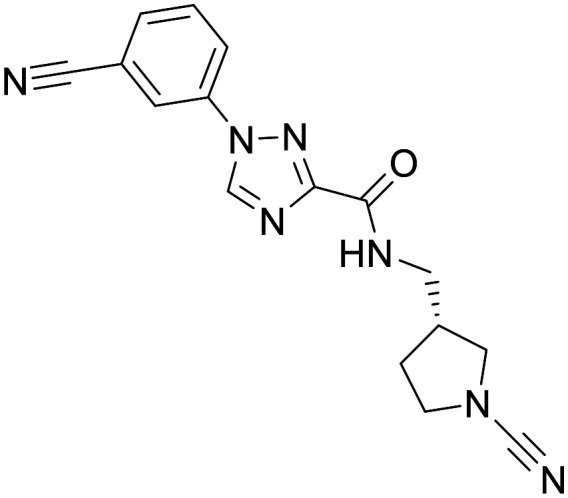

Mission-Example 1 (ref. 91)

In 2020 Mission Therapeutics followed up MT#1 with Mission-Example 1, exhibiting good potency in an in vitro biochemical assay of USP30 inhibition, and high endogenous cellular target engagement. Mission-Example 1 has been extensively profiled in in vitro ADME studies, the properties of which indicate Mission-Example 1 as being a suitable tool compound for USP30 target validation in vivo. A limiting property of example 1 for CNS indications might be its poor permeability and high Pgp efflux ratio in the MDCK-MDR1 flux assay (Pgp ER = 23, Papp = 4 × 10−6 cm s−1), however in vivo target engagement studies in mouse brain showed excellent target engagement in the CNS. A concern with targeting the catalytic Cys77 on USP30 is poor selectivity across other cysteine proteases. Mission-Example 1 was profiled in a DUB selectivity panel against 35 DUBS and showed greater than 600-fold selectivity. Mission-Example 1 was also profiled and shown to be selective against a panel of 39 kinases and 8 cathepsins. Safety pharmacology showed weak activity against hERG (30.2% inhib @ 30 uM) and negative results in both Ames and in vitro micronucleus assays. Further profiling has also been performed in preclinical disease models. Diet induced model of NAFLD and glucose homeostasis indicated a positive trend when dosed with Mission-Example 1 (50 mg kg−1, SC, QD). Unilateral ureteral obstructive kidney disease model (UUO) (15 mg kg−1, PO, QD or BID) showed a statically significant reduction in collagen deposition, and a non-statistical reduction in a-SMA levels, and in the Ischemia-induced acute kidney model (AKI) (15 mg kg−1, PO). Mission-Example 1 showed a significant benefit towards attenuated tubular atrophy and reduced cortical fibrosis. Profiling of Mission-Example 1 in neurodegenerative models is absent from the literature despite promising CNS target engagement.

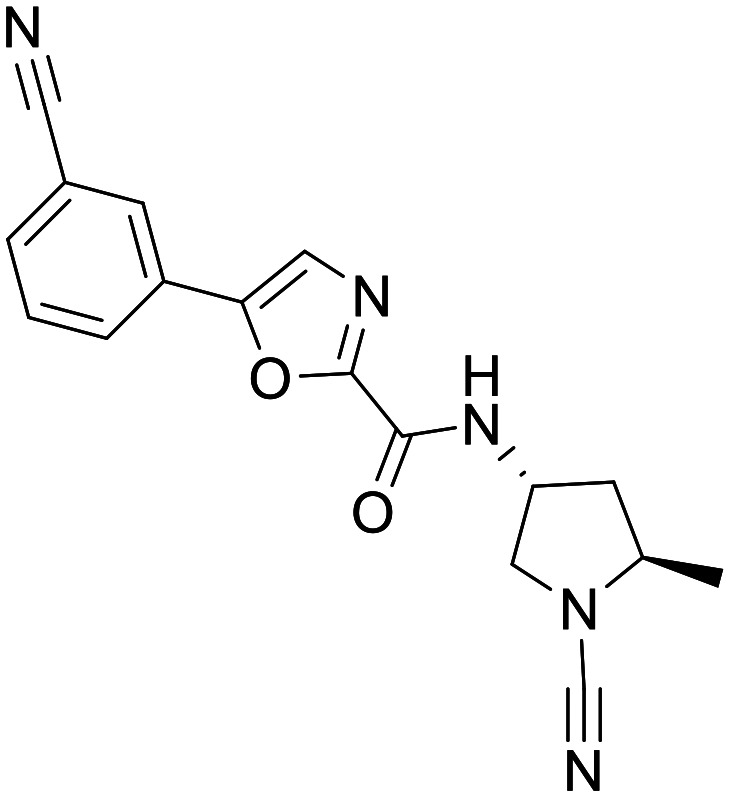

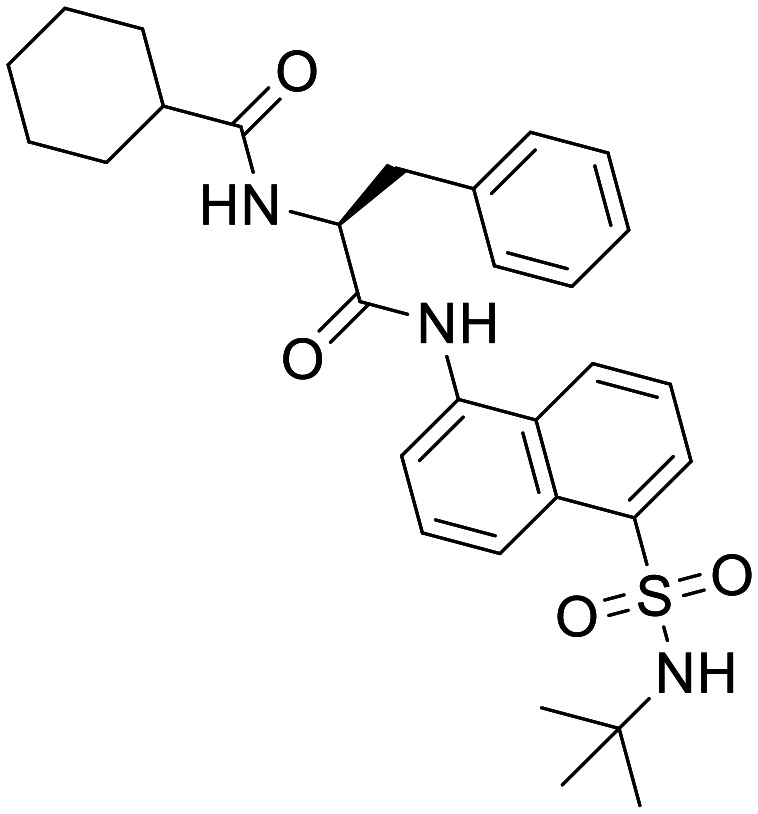

Mitobridge-MF-094 (ref. 92)

The development of non-covalent inhibitors of USP30 have been reported by Mitobridge Inc., describing naphthylsulfonamide diamide structures as moderately potent inhibitors of USP30 as reported in in vitro biochemical assays. Mitobridge-MF-094 shows exceptional selectivity against a panel of 22 ubiquitin specific proteases, in fact all compounds of this structural class with IC50 < 1 μM showed no inhibition in a triaged selectivity screen against USP1, USP8 and USP9. Mitobridge-MF-094 was shown to protect the active site of endogenous USP30 from modification by biotin-UbVME, an activity-based probe, at concentrations of 0.2–5 μM. Mitobridge-MF-094 was also shown to induce mitophagy when incubated with C2C12 myotubes, resulting in the loss of measured bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labelled mitochondrial DNA. Limited profiling and unfavourable physiochemical properties of these naphthylsulfonamides suggest their utility is likely to be confined to use as an in vitro tool compound. MF-094 ranks poorly in CNS MPO scoring, predominantly driven by its high PSA, number of hydrogen bond donors and molecular weight. We believe Mitobridge-MF-094 is unlikely to be a suitable in vivo tool for CNS targets.

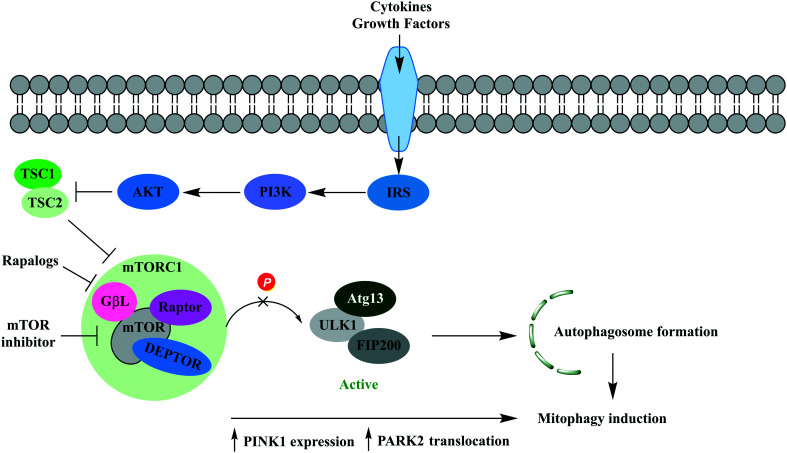

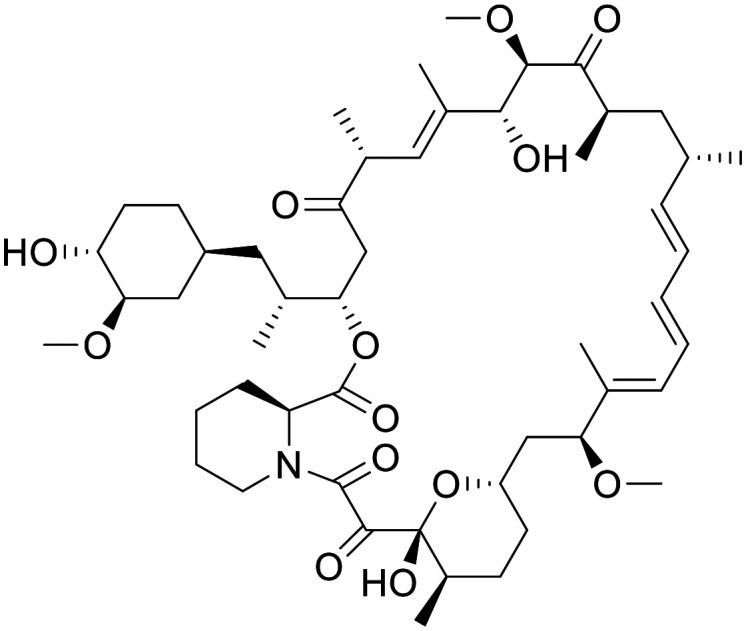

mTOR

Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a serine/threonine kinase in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/mTOR pathway, a pathway known to regulate key cellular processes. mTOR is a component of two functionally distinct multiprotein complexes, mammalian target of rapamycin 1 (mTORC1) and mammalian target of rapamycin 2 (mTORC2). Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) is a negative regulator of autophagy but has also been implicated in mitophagy through general autophagy initiation and PINK1-parkin mediated selective targeting of uncoupled mitochondria to the autophagic machinery.93 Hyperactivation of mTOR is well documented in cancer, and human genetic data also implicates mTOR hyperactivation in CNS dysfunction, particularly seizure disorders (Fig. 4).94

Fig. 4. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mTOR (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) signalling pathway. Growth factors and cytokines activate AKT signalling, resulting in inhibition of TSC1/2 complex activity and activation of mTOR. mTORC1 deactivates the ULK1/mATG13/FIP200 protein kinase complex preventing autophagosome formation. Rapalogs and mTOR inhibitors prevent deactivation of the ULK1/mATG13/FIP200 protein kinase complex leading to autophagy initiation. It has been shown MTORC1 inhibition also enhances PARK2 translocation and PINK1 expression, enabling recognition by the autophagic machinery and mitophagy induction.

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rapamycin

|

Allosteric inhibitor of TORC1 | Preclinical models of epilepsy limited evidence in phase 1 clinical trials for PTEN-deficient glioblastoma | Mass spectrometry of human glioblastoma tumour tissue shows concentrations of 0.3–36.3 nM in patients dosed 2 mg, 5 mg, or 10 mg | 1.4 | 0.11 |

Everolimus

|

Allosteric inhibitor of TORC1 | Approved therapy approved for the adjunctive treatment of adults and pediatric patients with TSC-associated partial-onset seizures | Female BALB/c athymic nude mice (5 mg kg−1, po) total [brain]:[blood] = 0.015 | 1.49 | 0.11 |

Novartis-compound 7

|

ATP competitive mTOR inhibitor | Neuronal cell-based models of mTOR hyperactivity. Mice with neuronal-specific ablation of the Tsc1 gene | Mouse total [brain]:[plasma] IV 1 mg kg−1 @1 h = 1.0, rat total [brain]:[plasma] PO 3 mg kg−1 @1 h = 4.0 | 5.38 | 0.59 |

Uni. Basel-PQR626

|

ATP competitive mTOR inhibitor | Loss of Tsc1-induced mortality at 50 mg kg−1 PO BID | Mouse total [brain]:[plasma] 10 mg kg−1 PO = 1.6 | 4.44 | 0.44 |

Allosteric mTOR inhibitors

Rapamycin

Rapamycin is an FDA approved therapy for the prevention of organ rejection in liver patients, a preventative treatment for restenosis after coronary angioplasty, and is being investigated in clinical trials as an antitumor agent.95 Rapamycin (Sirolimus) and its derivatives (Rapalogs) are allosteric inhibitors of TORC1 and form via the FKBP-rapamycin binding domain (FRB domain) of TORC1.96 It has been shown in preclinical models of disease that early treatment with rapamycin (3 mg kg−1, IV) prevents the development of epilepsy and premature death in Tsc1GFAPCKO mice. Late treatment also showed suppressed seizures and prolonged survival in the same model. Additionally, treatment with rapamycin showed inhibition of neuronal disorganization, and increased brain size in Tsc1GFAPCKO mice.97

In a phase 1 clinical trial of anti-tumour activity of rapamycin for recurrent PTEN-Deficient glioblastoma, rapamycin was determined to have distributed through the BBB and concentrations relevant to its pharmacology.98 Whilst tumour cell proliferation was reduced in 7 out of 14 patients, the necessary intratumoral rapamycin concentration required to inhibit mTOR in vitro were achieved in all patients; however, the magnitude of mTOR inhibition in tumour cells varied substantially.

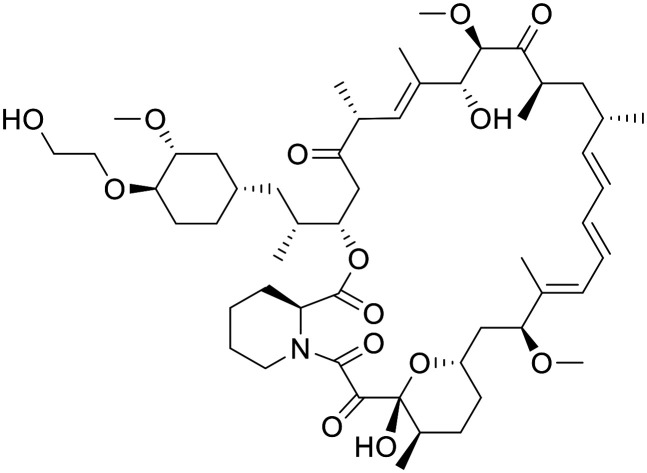

Everolimus

Everolimus is a rapalog that has recently been approved for the adjunctive treatment of adults and pediatric patients with TSC-associated partial-onset seizures.99 Everolimus treatment was shown to significantly reduce seizure frequency in both low and high exposure groups relative to placebo. A tolerable safety profile was observed, with low and high exposure groups experiencing grade 3 adverse event and serious adverse events relative to placebo. The ability of Everolimus to penetrate the BBB has been reported in non-tumour bearing female BALB/c athymic nude mice (5 mg kg−1, PO).100 Everolimus uptake in the brain was shown to be low (total [brain]:[blood] = 1.5%) but with accumulation over time. A more favourable PK profile however was observed in rats, where it was also shown that improved total [brain]:[blood] was observed at higher concentration, most likely due to saturation of efflux transporters.

TORC1 inhibition by rapalogs have reported adverse side effects largely attributed to their immune-suppressive activity. Whilst most toxicities are mild, few can be severe and require monitoring, with rash and mucositis being the most common. In the context of acute application such as chemotherapies, rapamycin analogues show an acceptable safety profile, however in the context of chronic conditions these properties may be limiting.101 Side effects may be more pronounced for CNS indications due to the limited ability of these compound to penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB), a contributing factor for this may be due reports of Pgp substrate activity.102

Efforts to ameliorate the metabolic and immunological side effects of rapalogs, as a result of off target mTORC2 inhibition, are currently being investigated through improved mTORC1 selectivity. Initial results prove promising however it is likely that both selectivity and improved CNS penetration will be required for an effective treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.103

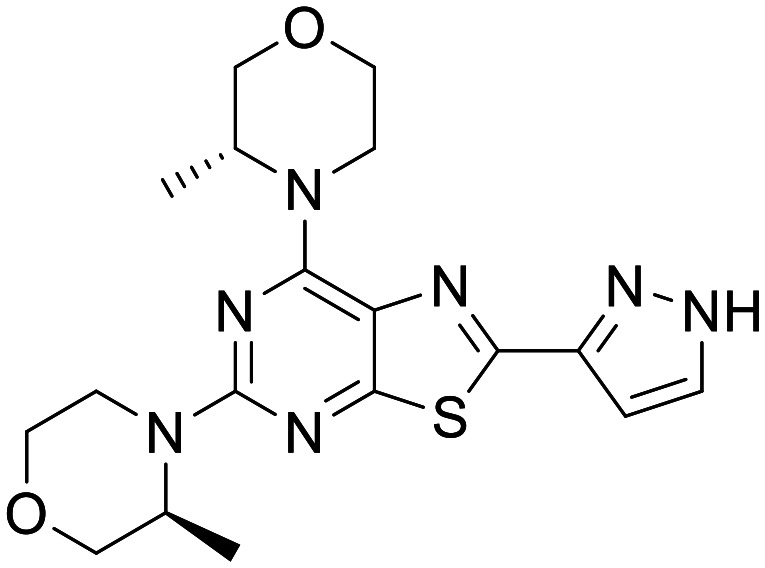

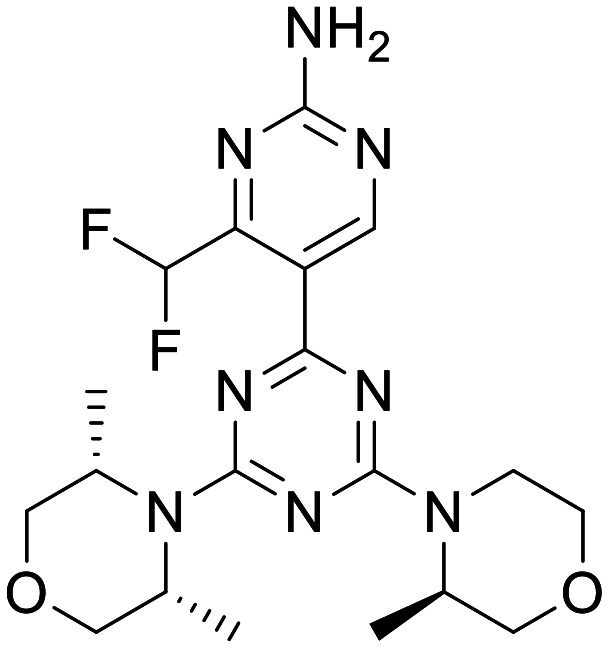

ATP competitive mTOR inhibitors

Following the successful completion of phase 3 clinical trials for Everolimus, significant investment in ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors has been made on the assumption full antagonism of all mTOR functions in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and related disorders would prove more effective, and inhibitors optimised for CNS penetration may help limit associated on-target toxicities.103

Novartis-Compound 7 (ref. 94)

Recently Novartis reported the development of thiazolopyrimidine ATP competitive inhibitors of mTOR specifically designed for CNS disorders. Novartis-Compound 7 showed high potency in a Phospho-S6 (Ser240/244) cellular assay, exhibiting good selectivity over other PI3Ks and against a panel of 468 kinases at a fixed concentration of 10 μM. Further selectivity profiling showed moderate potency against ATR, DNA-PK (DNA-dependent protein kinase) and PDE4D. In vitro PK characterisation of Novartis-Compound 7 showed low to moderate microsomal clearance across species and good permeability and low efflux ratio in an MDCK-MDR1 flux assay. Mouse and rat in vivo PK (5 mg mg−1, 3 mg kg−1 PO) confirmed good oral bioavailability, exposure and CNS penetration. In neuronal cell-based models of mTOR hyperactivity, Novartis-Compound 7 corrected the mTOR pathway activity and the resulting neuronal overgrowth phenotype. Novartis-Compound 7 also showed a significant improvement in survival rate of mice with neuronal-specific ablation of the Tsc1 gene.

Uni. Basel-PQR626 (ref. 104)

A structurally related class of mTOR inhibitors were also reported at a similar time by the University of Basel. Their lead compound Uni. Basel-PQR626 showed moderate potency in a Phospho-S6 (Ser235/236) cellular assay, with >164 fold selectivity against class I PI3K isoforms. In vitro PK characterisation showed high hepatocyte stability across species and good permeability and low efflux ratio in an MDCK-MDR1 flux assay. Mouse in vivo PK confirmed good CNS penetration. In mice with a conditionally inactivated Tsc1 gene in glia, PQR626 significantly reduced the loss of Tsc1-induced mortality at 50 mg kg−1 PO BID.

Based on the available information, it would appear that both ATP competitive mTOR inhibitors, Novartis-Compound 7 and Uni. Basel-PQR626, exhibit favourable profiles to effectively test mTOR inhibition in preclinical models of ND. Unlike allosteric mTORC inhibitors, ATP competitive inhibitors effectively diffuse across the BBB resulting in pharmacologically relevant CNS concentrations and good B/P ratios. Further advancement of these classes of compounds will be monitored with great interest.

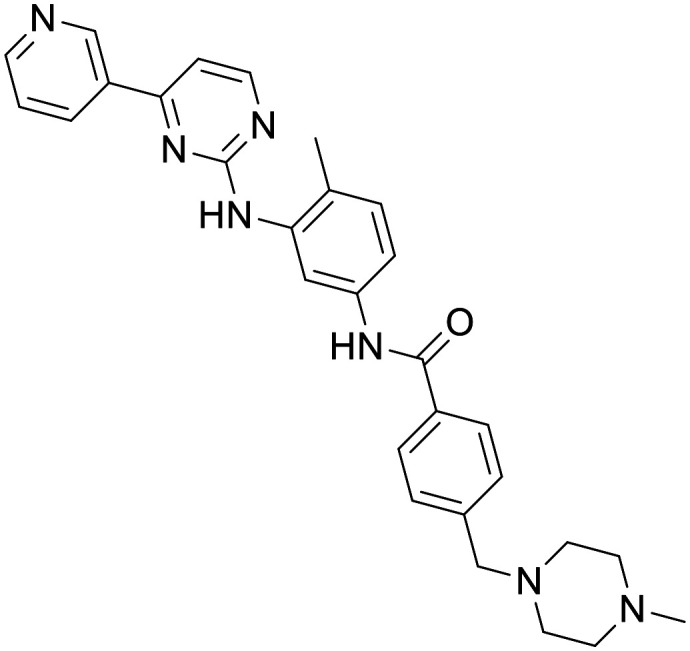

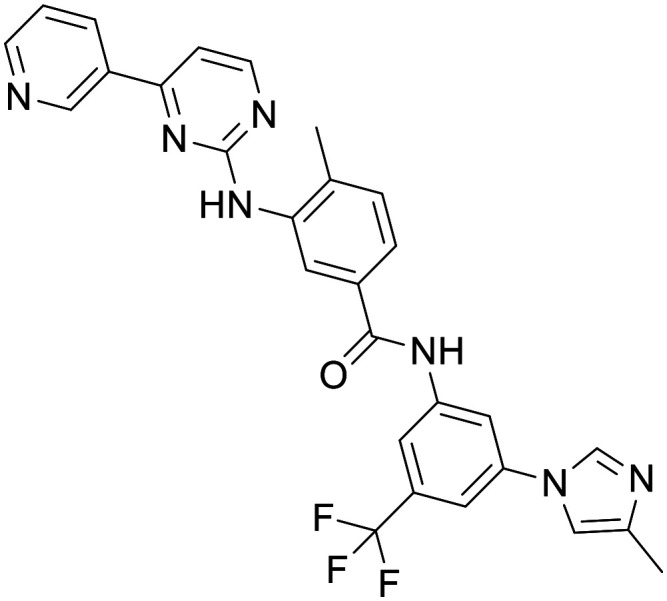

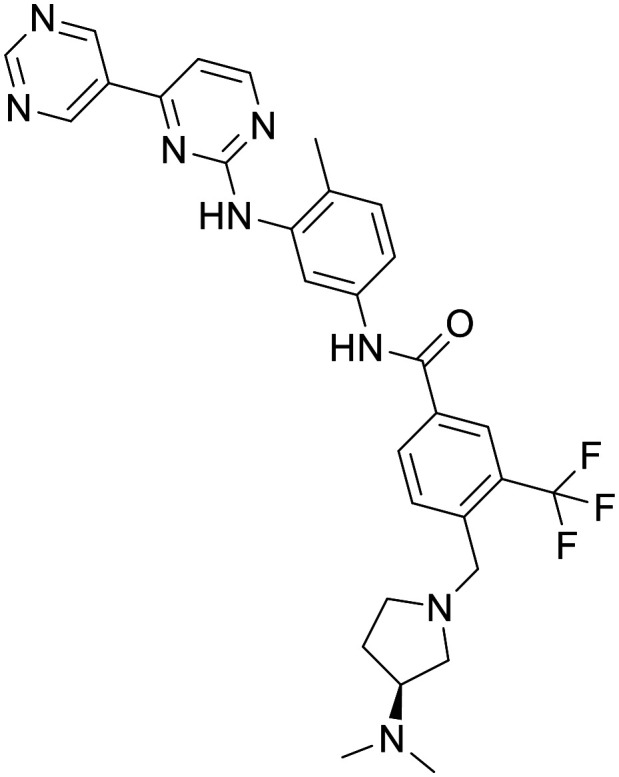

c-ABL

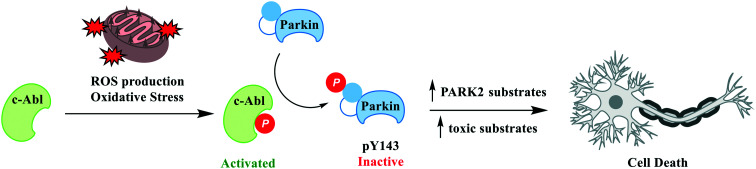

c-Abl (ABL1; Abelson tyrosine kinase) is a member of Abl family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases and is highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed in many subcellular compartments including in the nucleus, cytoplasm, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and cell cortex. c-Abl has been shown to interact with a variety of cellular proteins and has been implicated to function in a range of cellular processes, including regulation of cell growth and survival.105 c-Abl activation has been proposed as having a role in neurodegeneration in both sporadic and familial forms of PD, where c-Abl activation has been shown to deactivate Parkin, contribute to accumulation of toxic alpha synuclein species in preclinical animal models of PD and where increased c-Abl activity is observed in PD post-mortem brains (Fig. 5).106

Fig. 5. c-Abl activation in disease. c-Abl activation acts as a sensor of oxidative stress which in turn triggers multiple pathogenic signals. ROS/oxidative stress activated c-Abl phosphorylates Parkin Y143 leading to loss of ubiquitin ligase activity. Parkin inactivation leads to an increase in PARK2 substrates and an accumulation of toxic substrates ultimately resulting in cell death.

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Imatinib

|

c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Preclinical CNS disease models | Mouse PK indicated limited CNS penetration | 3.74 | 0.55 |

Nilotinib

|

c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Preclinical CNS disease models. Conflicting phase II trials in PD | Human PK show limited CSF exposure, [CSF]:[plasma] = <1% | 2.25 | 0.33 |

Bafetinib

|

c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Preclinical CNS disease models | C57 mice (10 mg kg−1) = total brain Cmax = 139 μM. Human ECF (240/360 mg PO BID, < 0.5 ng mL−1, 0.87 pM) | 3.09 | 0.46 |

Imatinib

A number of early studies explored the potential of Imatinib, a first-line drug for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), as a treatment for AD and PD. It was shown that neuronal cell death induced by Aβ fibrils was prevented by the inhibition of c-Abl with imatinib mesylate.107 Subsequent in vivo studies indicated that Imatinib prevents c-Abl-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation of parkin following MPTP treatment in vivo.108 Despite this promising result, it appears Imatinib is a poor candidate for neurodegenerative disorders due to poor blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration observed in mouse as a result of high substrate recognition by efflux transporters.109 Consequently, it is questionable if sufficient CNS exposure could be achieved at a safe dose.

Nilotinib

Nilotinib is a second-generation c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved in 2007 for a specific type of CML.110 It has been demonstrated in preclinical disease models that nilotinib reverses loss of dopamine neurons and improves motor behaviour via autophagic degradation of α-synuclein111 and increases endogenous parkin level and ubiquitination, leading to amyloid clearance.112 In a small, 12-patient pilot study, motor and cognitive outcomes suggested a possible beneficial effect on clinical outcomes in patients with PD when given nilotinib.113 Human PK studies however have shown the ratio of unbound [CSF]:[plasma] to be 0.5–1%, 1–4 hours after dose, suggesting achieving pharmacologically significant levels of nilotinib may be limiting. Recent phase 2 clinical trials have reported conflicting conclusions. A randomized trial in 75 moderately severe PD patients reported nilotinib to be safe and well tolerated, with increases in dopamine metabolites in the plasma and CSF, and a decrease in CSF hyper-phosphorylated tau and oligomeric α-synuclein. However, this was observed only in the lower dose.114 A conflicting study of 76 moderate PD patients showed with the same dosing regime there was no clinically or biologically meaningful effect, with cerebrospinal fluid/serum ratio of nilotinib concentration reported as 0.2% to 0.3%.115In vitro studies have further confirmed nilotinib's CNS penetration is likely to be limited in part due to efflux transport ABCG2 and ABCB1.116

Bafetinib

Bafetinib is a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor in development for treating Bcr-Abl+ leukemias. In an MPTP mouse model, treatment with bafetinib (10 mg kg−1) decreased the loss of dopamine in the striatum and the loss of TH+ neurons in substantia nigra pars compacts. In non-MPTP treated C57 mice pharmacologically significant concentrations were observed in the brain.117 However, a 7-participant phase 1 clinical trial in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma or brain metastases showed treatment with bafetinib resulted in moderate plasma exposure, but concentrations in the brain extracellular fluid (ECF) were below the limit of detection.118 It was recommended that bafetinib does not sufficiently cross an intact or disrupted BBB, and therefore, systemic administration of bafetinib is not recommended when investigating treatments for brain tumours.

Oxidative stress

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) is the term used to describe a family of oxygen-containing compounds (predominantly, but not exclusively, radicals) which have high oxidative potential in the cell.119 The downstream consequence of ROS production is a highly studied and complex area. ROS are produced in a variety of cell types, most notably by the family of NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes, and serve important signalling roles, including as key mediators in innate immune signalling.120 Conversely, an excess of ROS has been shown to lead to extensive oxidation of biomolecules. Proteins, lipids and nucleic acids have all been shown to oxidise as a consequence of ROS.121 This extensive ROS damage can lead to oxidative stress, where oxidised molecules aggregate to form damaging oligomers or present neoantigens that trigger an immune response and ultimately led to apoptosis/ferroptosis.122

The relevance of oxidative stress to the scope of this article is twofold. Firstly, the high metabolic demand means that despite that only encompassing 2% of the mass of a typical adult, the brain consumes ∼20% of the oxygen in the body. It has been shown that an imbalance in ROS levels leads to biomolecule oxidation in AD, PD and ALS patient samples,123,124 and is even observable in the CSF of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).125

Secondly, studies have revealed that defective mitochondria are a primary source of intracellular ROS.126 ROS are produced during oxidative phosphorylation as a consequence of the electron transport chain – in the context of a functioning cell there is minimal bleed of these species into the cellular milieu due to control by redox proteins such as superoxide dismutase (SOD).127 Damaged or aged mitochondria can leech these reactive species into the cytosol causing pathogenic oxidation of lipids, proteins and nucleic acids.121 This damage is reinforced by the loss of ATP-producing mitochondria, which can exacerbate cell damage in a cyclical nature. Aged mitochondria produce excess ROS, which leads to formation of toxic aggregates, which, in turn, damages additional mitochondria and leads to an increase in ROS production.

This connection between oxidative stress and ND has led to multiple attempts at therapeutic interventions. Broadly, these fall into two classes – those which modulate the biochemical pathways implicated in oxidative stress, and stoichiometric antioxidants. Some small molecule inhibitors of ROS production have been recently reviewed: we hope the perspective below provides some complementary context.128

Modulators of oxidative stress pathways

Nrf2 activators

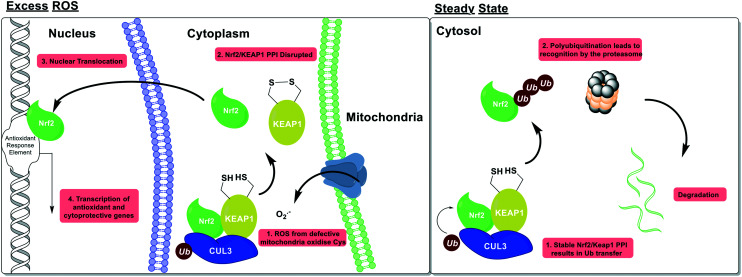

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a transcription factor which acts as the primary cellular response element to oxidative stress. Nrf2 is kept under homeostatic post-translational control by its cognate E3 ligase, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1). Under basal conditions Nrf2 is constitutively expressed, associated with KEAP1 then is degraded via the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS). Under conditions of oxidative stress, cysteine residues on the surface of KEAP1 become oxidised, which disrupts the KEAP1/Nrf2 interface and enables Nrf2 to translocate to the nucleus, where it induces the expression of multiple antioxidant and cytoprotective enzymes (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Nrf2 activation as a mechanism of ROS homeostasis. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is post-translationally repressed by its cognate E3 ligase KEAP1, and the ubiquitin proteasome. Under conditions of oxidative stress, sensor cysteines in KEAP1 are oxidised; this disrupts the complex with Nrf2, enables Nrf2 to traffic to the nucleus, and initiate production of multiple antioxidant proteins.

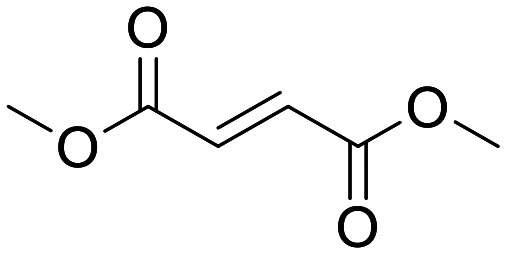

Dimethyl fumarate

The discovery of Nrf2 as a central node for antioxidant response has led to a flurry of interest in discovery small molecule Nrf2 activators. Indeed, this target is one of the few discussed in this review for which an approved drug exists – dimethyl fumarate (DMF, Tecfidera®), originally used for psoriasis, is currently marketed by Biogen for the treatment of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis, and has been reported to be an Nrf2 activator.129 Despite a simple chemical structure, the biological mechanism of action of DMF is extremely complex. DMF itself is a prodrug and is immediately hydrolysed to monomethylfumarate (MMF) in vivo to such an extent that DMF is not quantified in the plasma of patients.130 MMF is a small organic acid which has highly variable PK in humans and there are conflicting reports in the literature concerning the ability of MMF to cross the BBB. We could only find one report of the brain exposure of MMF, showing low but measurable exposure in rat brain following 3 mg kg−1 oral administration of DMF.131

The chemical structure of DMF as a low molecular weight, activated electrophile might indicate the potential for binding to multiple nucleophiles in the cell. Indeed, proteomic studies have shown that both DMF and MMF modify multiple protein targets at clinically relevant concentrations, including those with a neuroprotective phenotype.132–134 In addition, the ability of DMF/MMF to activate Nrf2 in CNS cell populations has been disputed.135

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®)

|

Nrf2 activator (KEAP1 inhibitor) | Marketed for the treatment of MS at a dose of 240 mg bid. Evidence of Nrf2 gene expression at 15 mg kg−1 in mice | Low but measurable exposure of MMF in rat brain following 3 mg kg−1 oral dose of DMF | 6.0 | 0.62 |

Omaveloxolone

|

Nrf2 activator (KEAP1 inhibitor) | Efficacy in a small patient population with Friedreichs ataxia (n = 51, 150 mg qd) | Excellent brain distribution has been demonstrated in cymologous monkey | 2.83 | 0.54 |

Bardoxolone

|

Nrf2 activator (KEAP1 inhibitor) | Bardoxolone methyl induces Nrf2 genes in monkey kidney at 30 mg kg−1 | Little evidence for bardoxolone methyl, although convincing evidence for amide analogues | 3.0 | 0.33 |

GSK/Astex-example 1

|

Nrf2 activator (KEAP1 inhibitor) | Activity in a battery of cellular and cell-free assay systems | None reported | 3.34 | 0.6 |

Although the benefits of Tecfidera treatment to MS patients have been clearly and convincingly demonstrated,136 the precise mechanism of action of this molecule and the ability of DMF to drive pharmacology in the CNS have not been convincingly deconvoluted.137

Owing to an increased interest in Nrf2 activators and the limitations with Tecfidera, multiple other chemical series have been disclosed in the literature. The majority of these approaches are designed to interact with the sensor cysteines via an electrophilic component; this has led to many poorly optimised compounds with undesirable properties.138

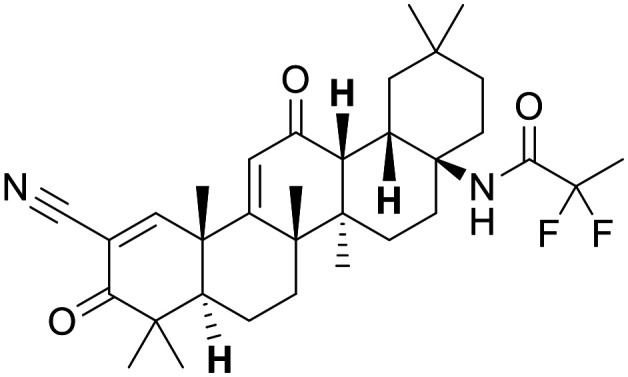

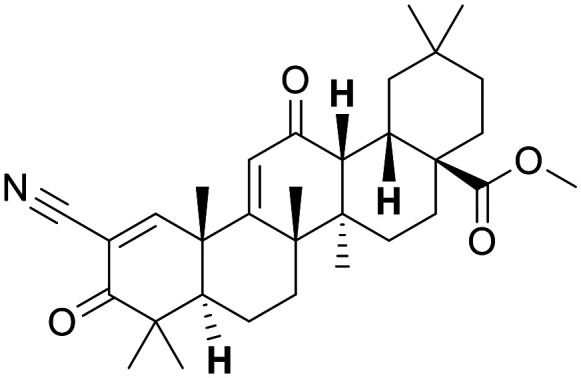

Other Nrf2 activators

Nonetheless, high fidelity molecules have been discovered and disclosed. Of particular note, omaveloxolone has advanced to clinical trials for oncology and Friedreichs ataxia.139,140 This synthetic triterpenoid shows excellent brain distribution in cymologous monkey.141 Furthermore, a non-covalent series was identified by GSK and Astex,142 which possesses an improved MPO score when compared to omaveloxolone and bardoxolone. The presence of an acid group and the CNS exposure risk identified by the MPO scores may highlight a PK risk with this series compared to the covalent molecules.

Nox2 inhibitors

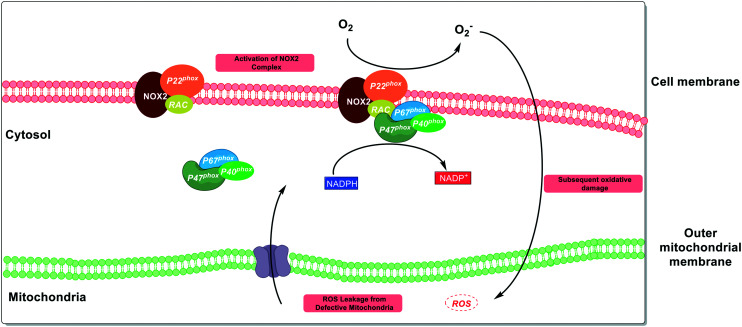

After leakage from mitochondria, the next most abundant source of ROS is generation by NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes.143 Although often viewed as distinct from mitochondrial ROS leakage,144 there is significant evidence of crosstalk between NOX and mitochondria.145,146

NOX enzymes catalyse the formation of superoxide from NADPH and molecular oxygen, and are the only protein family where ROS are their sole product. The function of these proteins is primarily in innate immune signalling leading to an antimicrobial immune response.147 Seven NOX family members have been discovered so far,148 with cell-type149 and tissue-specific expression.150 The biochemistry of these proteins is highly complex, with multiple subunits and bindings partners required to coordinate to form competent enzymatic complexes (Fig. 7).151

Fig. 7. Interplay between NOX2 ROS production and defective mitochondria. In the CNS, NOX2 provides a distinct source of ROS to mitochondria and acts as a key mediator of innate immune signalling. Despite the orthogonal nature of the pathway, there is evidence that NOX2 can be activated by mitochondrial ROS, leading to a feed-forward cycle of oxidative stress.

Of the 7 NOX family members, NOX2 has the strongest connection to ND.152 NOX2 has the highest expression level in the CNS, specifically in microglia150 and has been shown to be upregulated in ALS patient spinal cord.153 As with the example of Nrf2, this translational potential has led to significant interest in this target from the community but with considerable variance in the quality of compounds used to interrogate these targets.

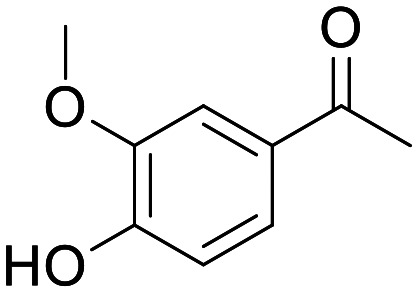

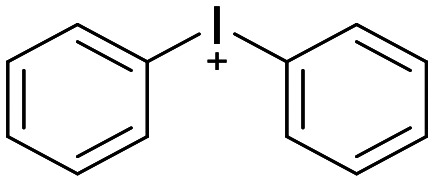

Apocynin/DPI

The majority of the biological elucidation of NOX2 has been done using two tool compounds: apocynin and diphenylene iodonium (DPI). Apocynin is a small, moderately polar and weakly basic phenol,154 which has been in early clinical trials for non-central inflammatory disorders.155 As early as 1994, Apocynin was reported to be a NOX inhibitor through inhibition of the migration of the p47phox to the membrane at a concentration of 300 μM.156 The use of this molecule has persisted in the literature despite subsequent reports showing that this compound is unstable and will dimerise,157 and is an oxidative scavenger which can interfere with many common ROS assays.154 These observations make apocynin wholly unsuitable for use in evaluating NOX pharmacology. Despite reasonable CNS MPO scores, the reported PK in rat is poor and will make sufficient exposure in vivo a challenge.158,159

Similarly, the hypervalent iodonium compound DPI is a non-selective flavoprotein inhibitor, which has been shown to have pleiotropic effects on cells.160,161 Some SAR studies have been conducted, however no studies have been able to demonstrate improving specificity.162

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Apocynin

|

NOX inhibitor | Inhibitor of the migration of the p47phox at 300 μM | None, low peripheral exposure in rodents | 5.83 | 0.77 |

Diphenylene iodonium (DPI)

|

NOX inhibitor | Non-selective flavoprotein inhibitor | Non reported | 5.36 | 0.62 |

GSK2795039

|

NOX inhibitor (NOX2 selective) | Moderately potent NOX2 inhibitor with an IC50 of ∼500 nM in multiple cellular and cell free assays | Rat total brain : blood ratio of 0.82 after 1 mg kg−1 iv infusion | 4.05 | 0.63 |

The evidence that either DPI or apocynin act on NOX pharmacology is not strong, and the evidence of effects on multiple other targets preclude these molecules from being useful tools for assessing this pathway in the treatment of ND.

GSK2795039

Other approaches exist with more promise and notably a group from GSK have disclosed GSK2795039 as a moderately potent NOX2 inhibitor, which critically shows selectivity over other NOX family members and related proteins.163 Despite containing some functional groups considered to be deleterious to CNS exposure, such as a bisarylsulfonamide, the authors report significant brain to plasma ratios in mouse and rat. GSK2795039 appears promising for further elucidation of NOX2 biology. Briefly, other groups are starting to publish on more modern hit-finding approaches to selective NOX2 inhibitors and it will be interesting to see if these approaches can produce more diverse chemical matter to modulate this target.164

Stoichiometric antioxidants

The approaches above highlight strategies that tackle the biochemical pathways involved in the production and cellular responses to ROS at the mitochondria. Notwithstanding these advances, an alternative approach is the use of stoichiometric antioxidants to quench cellular ROS before oxidative damage can occur.165,166 Indeed, there have been claims of the potential of antioxidants in the fields of oncology,167 cardiovascular disease,168 inflammation,169 metabolic diseases170 and ND.171

The strategy of ROS quenching has shown efficacy in a vast variety of preclinical disease models and is intuitively attractive. It has the appeal that many agents used for antioxidant therapy are vitamins and other secondary metabolites that have been used in traditional medicine for centuries172 – the idea of treating AD with vitamin C is certainly appealing.173 Despite this, a plethora of clinical trials and associated meta analyses have failed to demonstrate profound effects in patients.174

Several reasons have been proposed to account for the lack of clinical success in neurodegenerative disorders. One of the most apposite is exposure in the relevant compartment; these antioxidants will need to achieve sufficient exposure in the CNS to quench the (often short-lived)175 ROS species at their site of production. A related issue is the high concentrations needed – in contrast to full occupancy of an enzyme, the concentrations needed to stoichiometrically quench ROS species in a disease system could be many orders of magnitude higher,176 significantly increasing the barrier to achieve therapeutically relevant exposure.

We have attempted to summarise a non-exhaustive list of some of the many antioxidants investigated in ND. We have tried to capture as much chemical diversity as possible, aiming to assess if the data are supportive of sufficient exposure being achieved at the site of action, and hence whether the mechanism was effectively tested. We have used the same criteria for assessment as used in the rest of the review for consistency, although we note that as these structures are often derived from primary or secondary metabolites which means there is a possibility of significant transport-mediated disposition of these compounds, which will be poorly captured by medicinal chemistry heuristics. The full list of compound properties is detailed below – all have promising preclinical efficacy data which are not discussed herein, this analysis shall focus on clinical data when possible.

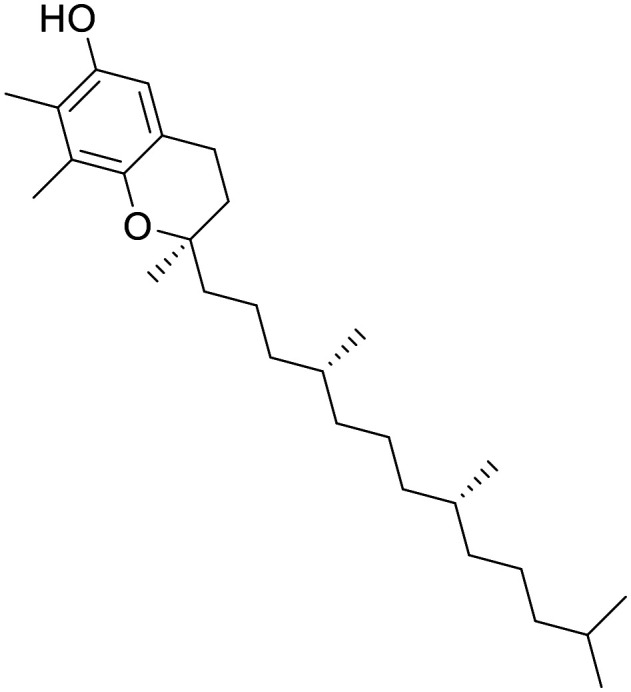

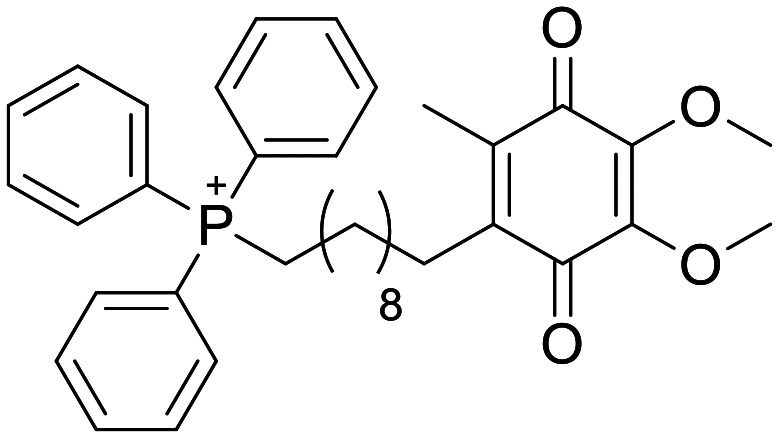

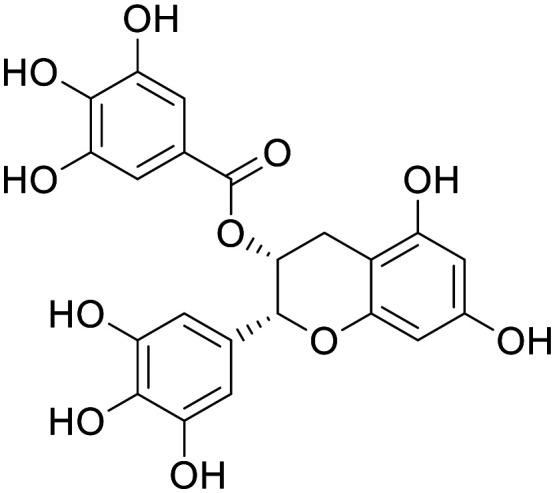

| Compound | Putative target | Evidence of efficacy | Evidence of exposure in CNS | CNS MPO | CNS pMPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tocopherol (vitamin E)

|

NA | Some hints of efficacy in certain outcomes in AD trials, but also many example of failure to demonstrate efficacy at doses of up to 5 g per day | C max of 50 nM is detected in CSF following 400 IU (268 mg) oral dosing | 2.8 | 0.58 |

Mitoquinone

|

NA | Delay in cognitive decline in 3xTg AD mice, following 100 μM supplementation of drinking water. Failure to demonstrate efficacy in PD trial | Not reported | 3.0 | 0.48 |

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCg)

|

NA | A plethora of positive preclinical studies, and negative clinical studies have been published | No exposure in CSF following oral dosing in human | 3.3 | 0.17 |

KNS-760704 (R-(+)-pramipexole)

|

NA | Prolonged survival in SOD1 G93A ALS mouse model at 100 mg kg−1 | Exposure in the CSF of AD patients | 4.76 | 0.73 |

3-n-Butylphthalide (NBP)

|

NA | Protected neurons in mitochondrial insult models of PD at ∼1 μM in vitro and 80 mg kg−1in vivo, and in vascular dementia models at 60 mg kg−1 | Hard to say – the ability of NBP metabolites to cross the BBB in rats is highly variable. Human plasma Cmax of 514 ng mL−1 (2.7 μM) | 4.78 | 0.55 |

Edaravone (Radicava)

|

NA | Approved for the treatment of ALS | Not found in peer reviewed literature. Good CNS exposure reported in regulator document | 5.63 | 0.58 |

Vitamin E (tocopherol)

Vitamin E has been investigated as an antioxidant for over 50 years (ref. 177) with strong genetic associations of vitamin E deficiency to neurological disorders.178 Vitamin E has the additional benefit of reasonable human PK,179 and a safety profile that allows multi-gram oral doses.180 The mechanisms of compound disposition for vitamin E are not well understood,181 but it is clear that oral supplements lead to increased vitamin E levels in the CSF.182

Nonetheless, despite some promising early results183 researchers have not been able to consistently demonstrate efficacy in ND trials for vitamin E.184,185 It is tempting to view this inconsistency as evidence against antioxidant therapy for the treatment of ND, but important pieces of the puzzle are missing. For instance, timing is important, as treatment late in disease (when symptoms are most quantifiable) might be too late in disease course for antioxidant rescue.186 Even more notably, although oral vitamin E supplementation does increase CSF levels, CNS exposure is not binary and it is unclear what absolute brain levels are achieved. One report suggests that although plasma concentrations can reach levels of approximately 30 μM, only 50 nM is detected in CSF following 400 IU (268 mg) oral daily dosing.187 This may be insufficient to provide a meaningful reduction in acute ROS levels. The longitudinal data on lifetime risk reduction is more promising, perhaps indicating that increasing chronic levels of vitamin E is a more promising strategy.188

Mitoquinone mesylate

A very interesting and unusual molecule is the phosphonium cation mitoquinone mesylate (MitoQ). This compound is bifunctional – the quinone portion acts as an antioxidant, whereas the triphenylphosphonium cation portion acts as a targeting moiety by exploiting the intrinsic negative potential of the mitochondria.189 The proposed advantage of this molecule is concentrating the antioxidant effects to the relevant cellular compartment, and thereby driving efficacy from lower systemic concentrations – however, it should be noted that there are reports of the triphenylphosphonium carrier causing mitochondrial toxicity.190 As with many antioxidants, this compound has been used to demonstrate rescue phenotypes in rodent models of Alzheimers191 which has resulted in the compound being tested in clinical trials for AD although interestingly, in the context of modulation the vasculature.192 Disappointingly, this compound failed to show efficacy in a phase 2 PD trial.193

As stated above, exposure at the site of action is likely to be key. Peripheral human PK has shown that following a large oral dose, Mito-Q achieve a modest Cmax of in plasma;189 however, we could find no measurement of human CNS exposure. Rodent PK experiments with radiolabelled Mito-Q have shown some tissue (including brain) accumulation upon chronic dosing, although <2% of the residual compound was in the brain (with the vast majority in the liver).194 Whilst it is impossible to ascertain the cause of this discrepancy without more data, we propose the pharmacokinetics of Mito-Q are insufficient to assess if antioxidants are a suitable therapeutic strategy for patients with neurodegenerative disorders. Work ongoing in the further optimisation of novel mitochondrial targeting motifs shows the potential of this strategy for future development.195

Epigallo-catechin gallate (EGCg)

EGCg is a complex polyphenol natural product, and the primary bioactive compound found in green tea. This compound has successfully shown efficacy in multiple preclinical cellular and in vivo models.196–198 There have been numerous clinical trials on EGCg and various other green tea components for neurodegenerative disorders and various other cognitive endpoints, so far failing to show efficacy.199 EGCg has a highly unorthodox structure for a CNS drug; however, reports indicate total brain : plasma ratios of 0.1 in the CNS of rats200 – despite this promising study, a small human trial showed no exposure in the CSF following oral administration.201

The next selection of antioxidant compounds have properties much more consistent with medicinal chemistry heuristics for CNS penetrant molecules; i.e. generally smaller compounds with balanced polarity and fewer hydrogen bond donors.

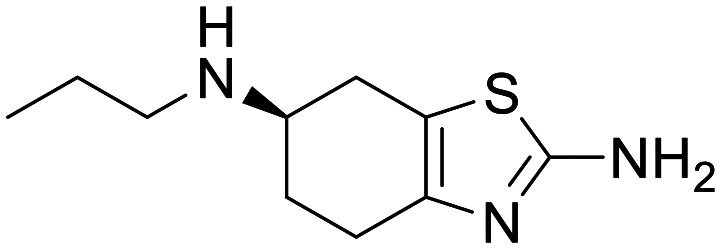

KNS-760704, (R-(+)-pramipexole)

R-(+)-Pramipexole is the distomer of the marketed dopamine agonist pramipexole (Mirapex), which despite having multiple orders of magnitude lower affinity at the dopamine receptor, is equipotent to the eutomer in many ND preclinical models.202R-(+)-Pramipexole has entered into a Ph1/2 study for ALS,203,204 and has demonstrated good peripheral PK, with excellent exposure in the CSF of AD patients.205 Unfortunately, this compound has not progressed through clinical development for ALS or AD, and data has been published showing that the eutomer Mirapex does not display efficacy in PD.206 It is difficult to draw conclusions on this molecule from the published literature, it is important to note that the published potency of this compound in preclinical models is very low, with IC50 in the range of 15–100 μM and high doses required in vivo. Additionally, whilst the PK of this molecule would indicate good exposure at the site of action, there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate modulation of the desired pharmacology.

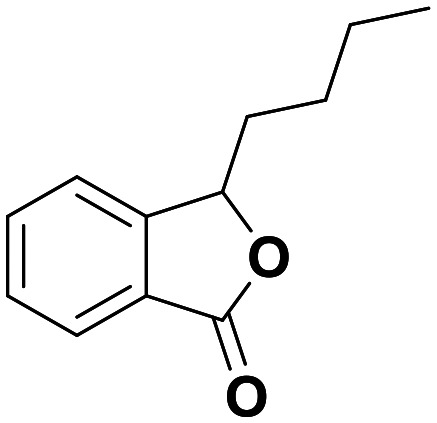

3-n-Butylphthalide (NBP)

3-n-Butylphthalide(NBP) is the racemic mixture of a lactone natural product, in which the (L-) isomer is one of the main components responsible for the smell of celery207 and is approved in China for the treatment of ischemic stroke.208 The simple structure of NBP disguises extremely complex pharmacology; the compound is extensively metabolised in humans to at least 23 metabolites, the four most abundant of which have exposures that vastly exceed that of NBP.209–211 Preclinically, NBP has been reported to effect pathways as diverse as oxidative stress, platelet activation, mitochondrial health, glial activation, apoptosis and neurogenesis.208 In terms of disease models, it has been shown to positively modulate glial activation in a mouse model of ALS,212 protected neurons in mitochondrial insult models of PD in vitro and in vivo,213 and in vascular dementia models.214

NBP is currently in a 92 patient trial for AD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02711683). Human plasma PK has shown moderate exposure with extensive formation of metabolites.210 A detailed study of the ability of NBP metabolites to cross the BBB in rats has shown differential exposure,215 and this coupled to highly complex pharmacology highlights that any meaningful PK/PD relationship will be extremely complex for this compound.

Edaravone (Radicava)

Finally, edaravone (Radicava) is an antioxidant approved in Japan and the USA for the treatment of ALS. Originally determined to scavenge superoxide,216 it was directed towards ischemia. In 2008 a team from Japan showed a delay in motor decline in a mouse model of ALS following edaravone treatment at 15 mg kg−1.217 As a consequence there has been a significant amount of clinical investigation into the efficacy of edaravone treatment for ALS – this included small studies, which showed some interesting hints of pharmacology that were not powered to significance,218 larger trials which have shown no benefit over placebo219 and other phase 3 trials which have demonstrated small but significant delays in functional decline,220 although no extension of life is observed.

Although approved by the regulators, the limited efficacy of edaravone make its continued use controversial.221 This limited efficacy should be viewed in the context of the therapeutic landscape of ALS; there is no cure for this disease, which has a median survival of under three years.222 It is likely to be extremely challenging to have a profound impact on the course of this disease, following the onset of symptoms.