Abstract

In addition to CD4+ T cells and neutralizing antibodies, CD8+ T cells contribute to protective immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), an ongoing pandemic disease. In patients with COVID-19, CD8+ T cells exhibiting activated phenotypes are commonly observed, although the absolute number of CD8+ T cells is decreased. In addition, several studies have reported an upregulation of inhibitory immune checkpoint receptors, such as PD-1, and the expression of exhaustion-associated gene signatures in CD8+ T cells from patients with COVID-19. However, whether CD8+ T cells are truly exhausted during COVID-19 has been a controversial issue. In the present review, we summarize the current understanding of CD8+ T-cell exhaustion and describe the available knowledge on the phenotypes and functions of CD8+ T cells in the context of activation and exhaustion. We also summarize recent reports regarding phenotypical and functional analyses of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells and discuss long-term SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cell memory.

Keywords: CD8+ T cell, Activation, T-cell exhaustion, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19

Subject terms: Cellular immunity, Infection

Introduction

Since the initial reports of pneumonia cases of unknown origin in Wuhan, China, in late December 2019 [1], novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been rapidly spreading worldwide. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, manifests with a broad spectrum of clinical symptoms, from asymptomatic infection to critical disease [2]. COVID-19 has threatened public health and had a devastating economic impact. Global efforts are underway to control the COVID-19 pandemic. Prophylactic COVID-19 vaccines using various platforms have been approved since December 2020, and their administration has started in populations throughout the world [3–7].

A better understanding of host immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 is crucial to the development of effective vaccines and therapeutics and ending the current pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 infection elicits the activation of both innate and adaptive immunity [8–11]. In adaptive immunity, CD8+ T cells play an essential role in controlling viral infection by killing virus-infected cells and producing effector cytokines. Since the emergence of COVID-19, remarkable progress has been made in understanding CD8+ T-cell responses against SARS-CoV-2. It is now clear that SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses are detected in the acute and convalescent phases of COVID-19 [12–17]. In addition, recent studies using animal models have reported that CD8+ T cells contribute to protection from the development of severe COVID-19 [18, 19].

In COVID-19 patients, the CD8+ T-cell population undergoes quantitative and qualitative changes. Decreased cell number and activation phenotypes are frequently observed, particularly in severe disease [16, 20–24]. Previous studies have also reported exhaustion phenotypes of CD8+ T cells in patients with severe COVID-19 based on the upregulation of inhibitory receptors (IRs) [20, 25–30], which may impair host defenses and result in poor disease outcomes. In contrast, no significant evidence of CD8+ T-cell exhaustion has been observed in several single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analyses [31, 32]. However, all of these studies have the limitation of their conclusions relying on the expression of IRs or transcripts related to T-cell exhaustion without information on the antigen specificity of CD8+ T cells and their effector functions. Our previous study using major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) multimers demonstrated that PD-1+ SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells are functionally active in terms of interferon (IFN)-γ production, implying that these cells are not truly exhausted [33].

Several reviews have already summarized and discussed different aspects of CD8+ T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 in terms of cross-reactivity, kinetics, and protective roles [34–39]. In the current review, we focus on the activation and exhaustion of CD8+ T cells in patients with COVID-19. We summarize the current understanding of CD8+ T-cell exhaustion and discuss available knowledge regarding the activation and exhaustion of CD8+ T cells in the context of COVID-19.

The characteristics of exhausted CD8+ T cells

An overview of CD8+ T-cell exhaustion

During acute viral infection, naive CD8+ T cells that recognize antigens presented on MHC-I by their T-cell receptors (TCRs) are activated and undergo clonal expansion and differentiation into effector CD8+ T cells [40, 41]. Effector CD8+ T cells produce cytokines, including IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and directly kill target cells [42]. In the subsequent contraction phase following antigen clearance, a small proportion of effector CD8+ T cells differentiate into memory CD8+ T cells [40, 41]. Memory CD8+ T cells rapidly exert effector functions upon antigen re-encounter, playing a crucial role in host protection during reinfection [41].

On the other hand, when antigens persist in chronic viral infection or cancer, the development of memory CD8+ T cells fails, and the effector functions of CD8+ T cells become impaired [43, 44]. This state of CD8+ T cells is called “exhaustion.” CD8+ T-cell exhaustion was first reported in a previous study using a mouse model of chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection [45]. LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells that are continuously stimulated by antigens exhibit impaired effector functions and limited proliferation compared to conventional memory CD8+ T cells [46]. These findings have also been observed in human patients with chronic viral infection or cancer [47, 48]. T-cell exhaustion is evidently the main mechanism underlying immune dysfunction during chronic viral infection and cancer [43, 44, 49], and virus antigen-specific and tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells exhibit features of T-cell exhaustion and dysfunction [47, 48, 50–53]. CD8+ T cell exhaustion is now considered a distinct differentiation state of CD8+ T cells, with several key features (Fig. 1).

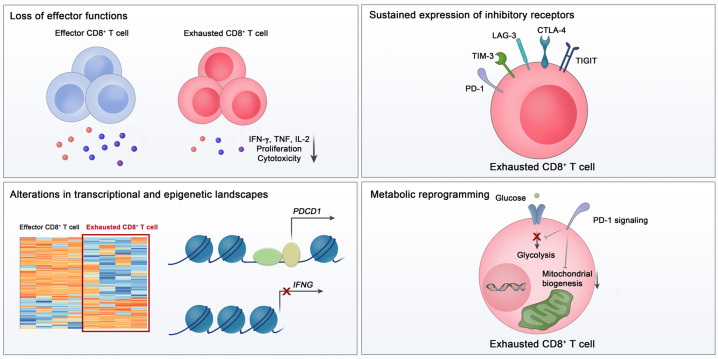

Fig. 1.

Key features of exhausted CD8+ T cells. Exhausted CD8+ T cells are characterized by a loss of effector functions, sustained expression of inhibitory receptors, altered transcriptional and epigenetic landscape, and metabolic reprogramming

The loss of effector function

CD8+ T-cell exhaustion is characterized by progressive and hierarchical impairment of effector functions. Generally, IL-2 production and proliferative capacity become compromised early, followed by defects in TNF production and cytotoxicity [54]. The loss of IFN-γ production occurs in more severely exhausted CD8+ T cells [55]. When antigen stimulation is excessive, clonal deletion or apoptosis of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells occurs, which is considered the end stage of CD8+ T-cell exhaustion [54]. Functional loss of exhausted CD8+ T cells eventually results in a failure to eliminate the virus or tumor cells. Therefore, a correlation between viral load and the severity of exhaustion in chronic viral infection can be explained by functional impairment of exhausted CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, exhausted CD8+ T cells respond poorly to homeostatic cytokines, including IL-7 and IL-15 [56], in relation to their low expression of CD127 and CD122 [57].

The functions of exhausted CD8+ T cells may vary across diseases, possibly related to antigens and the immune microenvironment. The absence of CD4+ cells has been shown to contribute to CD8+ T-cell exhaustion [58, 59]. In addition, a recent study reported that hypoxia, which is frequently observed in cancer, promotes functional impairment of T cells in the presence of continuous TCR stimulation [60].

Sustained expression of inhibitory receptors

Another key feature of exhausted CD8+ T cells is sustained expression of IRs [43, 44]. IRs counteract T-cell activation to avoid exaggerated immune activation. In particular, in antigen-persisting conditions, IRs mediate T-cell exhaustion by negatively regulating the activation of antigen-specific T cells.

Among the various IRs, PD-1 is a key molecule responsible for T-cell exhaustion [43, 44]. PD-1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein receptor belonging to the CD28 family [61]. An immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif and an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif are located in the intracellular region of PD-1 [44]. PD-1 has two ligands: PD-L1 (CD274 or B7-H1) and PD-L2 (B7-DC) [62]. PD-L1 is expressed not only by immune cells but also by nonimmune cells, including tumor cells, whereas PD-L2 is mainly expressed by antigen-presenting cells [63]. In the case of T cells, PD-1 expression is mainly induced and sustained by TCR-mediated stimulation, but PD-1 expression can also be induced by cytokines and other stimuli [62]. PD-1/PD-L1 engagement inhibits T-cell activation via the recruitment of SHP-2 and subsequent dephosphorylation of signaling molecules [43, 64, 65]. PD-1 blockade has been demonstrated to reinvigorate exhausted CD8+ T cells and reduce viral load during chronic LCMV infection [66, 67]. In tumor models, the blockade of PD-1 signaling also enhances the functions of CD8+ T cells, with robust antitumor effects [68, 69]. On the basis of these results, cancer immunotherapy targeting PD-1 has been developed and shown to have clinical benefits in multiple types of cancer [70–74].

In addition to PD-1, exhausted T cells express a battery of IRs, including TIM-3, LAG-3, TIGIT, and CTLA-4 [75, 76]. Although individual expression of PD-1 or other IRs is not sufficient to indicate CD8+ T-cell exhaustion, the coexpression of multiple IRs is considered a main characteristic of exhaustion. In exhausted CD8+ T cells, several IRs are coexpressed with PD-1 and provide a synergistic inhibitory effect [53, 77, 78]. Exhausted CD8+ T cells with a higher number of coexpressed IRs have more severe exhaustion [77]. Simultaneous blockade of multiple IRs leads to robust reinvigoration of exhausted T cells in cancers and chronic viral infections [70, 76].

Changes in the epigenetic and transcriptional landscape

In exhausted virus-specific CD8+ T cells from chronically LCMV-infected mice, the expression of multiple genes is altered, including genes related to TCR and cytokine signaling pathways, costimulatory pathways, and energy metabolism, as well as genes encoding IRs and transcription factors [79]. Several studies using a mouse model of chronic LCMV infection have also shown that various transcription factors, including T-bet, Eomes, Blimp1, NFAT, TCF1, IRF4, and TOX, are involved in CD8+ T-cell exhaustion [80–86]. In addition, BATF, which is commonly upregulated in both HIV-specific CD8+ T cells from HIV progressors and Jurkat cells following PD-1 ligation, mediates PD-1-induced suppression of T cells in vivo [87]. Although a master transcription factor specific to exhaustion has not yet been identified, multiple transcription factors are associated with exhaustion-specific gene expression and function [80, 81, 87, 88].

Epigenetic regulation at the chromatin level also plays an important role in controlling the differentiation and fate of CD8+ T cells. Recent technological advances in epigenetics have enabled us to investigate the epigenetic characteristics of exhausted CD8+ T cells. Previous studies using an assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq) have shown that the epigenetic landscape of exhausted CD8+ T cells is distinct from that of effector and memory CD8+ T cells [89, 90]. Remarkable differences in the accessible chromatin regions were observed between exhausted CD8+ T cells and effector/memory CD8+ T cells [89, 90]. For example, several open chromatin regions in the Ifng locus are present in effector and memory CD8+ T cells but not in exhausted CD8+ T cells [90]. In contrast, open chromatin regions related to IRs, such as PD-1, are specific to exhausted CD8+ T cells [89, 90].

Metabolic reprogramming

The activation and clonal expansion of CD8+ T cells are accompanied by alterations in cellular metabolism. During acute infection, a transition from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis is required for differentiation into effector CD8+ T cells [91–93]. Memory precursor T cells alter their cellular metabolism to oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid oxidation [94]. In transcriptomic analysis, substantial alterations have been observed in genes involved in metabolism and bioenergetic pathways in exhausted CD8+ T cells, suggesting that CD8+ T-cell exhaustion is accompanied by metabolic alterations [79]. Exhausted CD8+ T cells are known to undergo metabolic reprogramming, including decreased glycolysis and dysregulated mitochondrial energetics [95]. Moreover, PD-1 signaling suppresses glycolysis and promotes fatty acid oxidation in CD8+ T cells by inhibiting PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK signaling [96]. Furthermore, PD-1 blockade restores glycolysis in exhausted CD8+ T cells [97].

Uncoupling T-cell exhaustion from activation

Considering that CD8+ T-cell exhaustion results from persistent stimulation of T cells, it is challenging to distinguish T-cell exhaustion from activation. The surface markers and transcriptional signatures of exhausted CD8+ T cells closely overlap with those of activated CD8+ T cells [88, 98–100]. In addition, most characteristics of CD8+ T-cell exhaustion are individually insufficient to identify exhausted CD8+ T cells. In particular, because the majority of IRs are also transiently expressed in effector CD8+ T cells during activation, IR expression is not a unique feature of exhausted CD8+ T cells [44, 101]. A previous study also showed no impairment of cytokine production in CD8+ T cells expressing a diverse array of IRs, indicating that IR expression may not be directly linked to dysfunction [102]. In transcriptomic analyses of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from tumor-bearing mice, many IRs are present in the activation/dysfunction gene module but not in the dysfunctional gene module [103]. Furthermore, genes related to the cell cycle pathway, migration, cytotoxic molecules, and costimulatory receptors are commonly upregulated in both exhausted and activated CD8+ T cells [79].

Therefore, simultaneous consideration of diverse features, including dysfunction, sustained IR expression, transcriptional and epigenetic alterations, and metabolic derangement, is needed to identify bona fide exhausted CD8+ T cells and uncouple them from activated CD8+ T cells.

An overview of CD8+ T-cell responses against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, we have gained much information about CD8+ T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2. Early studies reported that SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses are successfully elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection [12, 13, 17]. SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses have been identified in ~70% of convalescent individuals after recovery from COVID-19 [12]. These responses are specific to a wide range of SARS-CoV-2 antigens, including spike, nucleocapsid, and membranous proteins, as well as other nonstructural proteins [12, 13, 17].

A series of studies suggest a critical role of CD8+ T cells in protecting against the development of severe COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses correlate with low disease severity during the acute phase [104]. Memory T-cell responses have been detected in COVID-19 convalescent individuals even in the absence of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies [105]. In addition, CD8+ T cells from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with severe/critical COVID-19 exhibit a lack of dominant clones compared to those from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with mild disease [106].

Recently, studies using animal models revealed the importance of CD8+ T cells in controlling SARS-CoV-2 infection. Limited viral clearance in the respiratory tract was observed in CD8+-depleted convalescent rhesus macaques upon SARS-CoV-2 rechallenge, implying that memory CD8+ T cells are required for the clearance of SARS-CoV-2 [18]. Furthermore, T-cell vaccination that does not elicit neutralizing antibodies partially protects SARS-CoV-2-infected mice from severe disease [19].

The CD8+ T-cell population in patients with COVID-19

The upregulation of activation markers and inhibitory receptors

There is a growing body of evidence that circulating CD8+ T cells from patients with severe COVID-19 exhibit an activated phenotype characterized by increased expression of CD38, HLA-DR, and Ki-67 [16, 20–22, 107]. In addition, a recent study analyzing airway immune cells revealed that CD8+ T cells from the airways of patients with COVID-19 were predominantly tissue-resident memory T cells and that these cells have an elevated proportion of activated cells [108].

An exhausted CD8+ T-cell phenotype with an upregulation of IRs, such as PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3, CTLA-4, NKG2A, and CD39, has been described in patients with COVID-19, particularly in those with severe disease [20, 25–29]. In addition, an scRNA-seq analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) showed that the exhaustion score in the CD8+ effector cluster was significantly higher in patients with severe COVID-19 than in healthy donors and patients with moderate disease [109]. Moreover, increased PD-L1 expression has been reported in basophils and eosinophils from patients with severe COVID-19 [110].

In contrast, a number of studies have reported no evidence of CD8+ T-cell exhaustion in patients with COVID-19, even in those with severe cases. An early study performing scRNA-seq analysis of PBMCs found that the T-cell exhaustion module score was not significantly changed in CD8+ T cells from patients with COVID-19, even in patients with severe cases with acute respiratory distress syndrome, compared to healthy donors [31]. In addition, a recent study using single-cell cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) and TCR sequencing described that a cluster of exhausted CD8+ T cells was not associated with COVID-19 [32]. In that study, the exhaustion of clonally expanded CD8+ T cells, as evaluated by IR expression, was not associated with disease severity [32].

Discrepancies in the results may be derived from several factors. First, there were differences in the criteria for disease severity among studies. Second, the exhaustion gene sets used in the analysis or the detailed method of analysis for the transcriptomic data were different. Third, the demographics of the study cohorts need to be considered.

The functions of CD8+ T cells in patients with COVID-19

Several studies have reported that CD8+ T cells from patients with COVID-19 exhibit a decreased cytokine-producing capacity upon stimulation with PMA/ionomycin [23, 27]. In contrast, another study reported that CD8+ T cells from patients with COVID-19 exert higher effector functions, including the production of IL-2 and IL-17A and the expression of the degranulation marker CD107a, upon anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation compared to cells from healthy donors [25]. However, these studies examined the functions of the CD8+ T-cell population following ex vivo stimulation with pan-T cell stimulants, not SARS-CoV-2 antigens; thus, they lack information on the antigen specificity of CD8+ T cells.

SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with COVID-19

The phenotype of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells

Considering that only a proportion of the CD8+ T-cell population is specific to the infecting virus, it is important to examine the phenotype and functions of viral-antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, not the total CD8+ T cell population, during viral infection. SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells from COVID-19 patients have been investigated by many researchers (Fig. 2). Early studies examined SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses using ex vivo stimulation-based functional assays, such as intracellular cytokine staining and activation-induced marker assays [12, 13, 15, 17]. In addition, scRNA-seq analysis following antigen-reactive T-cell enrichment (ARTE) allowed us to investigate SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8+ T cells at the transcriptome level [111, 112]. However, all of these assays have inherent limitations in that ex vivo stimulation may change the phenotype of CD8+ T cells. Moreover, stimulation-based functional assays detect functioning T cells, not virus-specific nonfunctioning cells. In contrast, MHC multimer techniques, which directly detect antigen-specific T cells, do not have these caveats [113]. Several studies using MHC-I multimers have examined the phenotypes of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells [16, 17, 33, 114, 115].

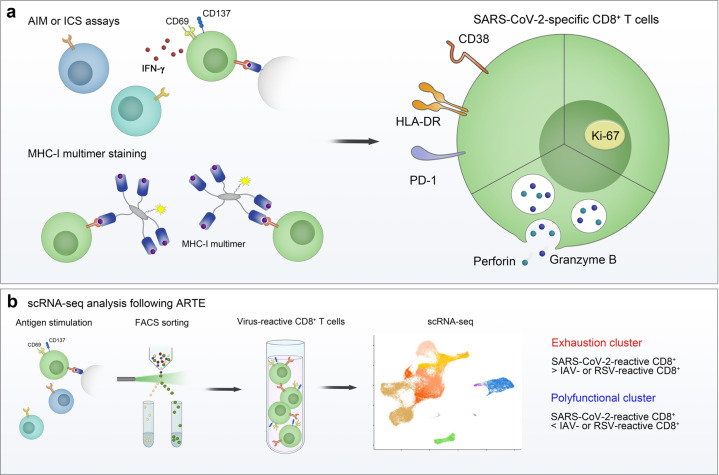

Fig. 2.

Phenotype of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells. The phenotype of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells was examined using a ex vivo stimulation-based functional assays, MHC-I multimer staining, and b single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) following antigen-reactive T-cell enrichment (ARTE). In the acute phase, SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells express activation markers (CD38 and HLA-DR), PD-1, Ki-67, and cytotoxic proteins (perforin and granzyme B). In scRNA-seq analysis of virus-reactive CD8+ T cells, the proportion of the “exhaustion” cluster, characterized by increased expression of exhaustion-associated genes, was higher in SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8+ T cells than in influenza A virus (IAV)- or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-reactive CD8+ T cells. In addition, the proportion of the “polyfunctional” cluster expressing high levels of genes encoding cytokines was lower in SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8+ T cells than in IAV- or RSV-reactive CD8+ T cells. AIM activation-induced marker, ICS intracellular cytokine staining

In the acute phase of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2-specific MHC-I multimer+CD8+ T cells express activation markers (CD38 and HLA-DR), Ki-67, IRs (PD-1, TIM-3, and LAG-3), and cytotoxic proteins (perforin and granzyme B), indicating that these cells are activated and proliferate with a high cytotoxic capacity [16]. This finding is in line with the result that SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8+ T cells detected by stimulation-based assays express CD38, HLA-DR, Ki-67, and PD-1 [16]. Similar results were observed in our analysis with MHC-I multimer staining. In a longitudinal analysis, we found that the expression of PD-1 and CD38 in MHC-I multimer+ cells decreases during the course of COVID-19 [33]. We also observed an inverse correlation between the expression of PD-1 and CD38 in MHC-I multimer+ cells and the number of days since symptom onset. These kinetics suggest that PD-1 expression in SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells is transient, not persistent, in patients with COVID-19. Thus far, relatively few studies have examined the expression of IRs other than PD-1 in SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells. In the acute phase of severe COVID-19, a considerable proportion of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells express TIM-3, LAG-3, TIGIT, and CTLA-4 [16]. The expression of TIM-3 and TIGIT in SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells tended to be lower among patients who recovered from mild COVID-19 than among patients with acute severe COVID-19 [16].

A recent scRNA-seq analysis of virus-reactive CD8+ T cells obtained using ARTE demonstrated that the proportion of the “exhaustion” CD8+ T-cell cluster characterized by increased expression of exhaustion-associated genes, including HAVCR2 (TIM-3) and LAG3, was higher in SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8+ T cells from COVID-19 patients than in influenza A virus (IAV)- and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-reactive CD8+ T cells from healthy donors [111]. Intriguingly, the exhaustion cluster showed significant enrichment of cytotoxicity-related genes, such as GZMB, GZMA, GZMH, PRF1, and TBX21, indicating that this cluster is not associated with dysfunction. On the other hand, the proportion of the cluster expressing high levels of genes encoding cytokines, including IFNG, TNF, CCL3, CCL4, XCL1, and XCL2, was lower in SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8+ T cells from COVID-19 patients than in IAV- and RSV-reactive CD8+ T cells from healthy donors [111], suggesting that SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8+ T cells have a reduced capacity to secrete effector cytokines.

The functions of PD-1-expressing SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells

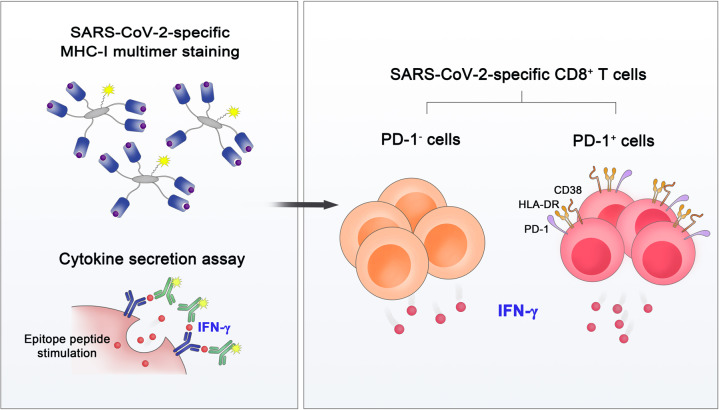

To investigate the effector functions of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells, our group performed MHC-I multimer staining, followed by proliferation assays and cytokine secretion assays (Fig. 3) [33]. SARS-CoV-2-specific MHC-I multimer+ T cells from individuals who recovered from COVID-19 showed robust proliferation upon ex vivo antigen challenge. In addition, despite the lower frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells in SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells than IAV-specific CD8+ T cells, IFN-γ was produced by SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells regardless of their PD-1 expression. The same results were observed when we analyzed SARS-CoV-2-specific MHC-I multimer+ cells from acute COVID-19 patients. These findings indicate that PD-1+ cells among SARS-CoV-2-specific MHC-I multimer+ cells are not exhausted but functionally active in the acute and early convalescent phases of COVID-19 and that PD-1 needs to be considered an activation marker rather than an exhaustion marker in patients with COVID-19. In addition, there was no significant difference between patients with severe and nonsevere COVID-19 in regard to IFN-γ production by SARS-CoV-2-specific MHC-I multimer+CD8+ T cells. However, our study relied on MHC-I multimers specific to HLA-A*02-restricted epitopes from the spike protein. CD8+ T cells specific to other SARS-CoV-2 epitopes restricted by other HLA-I allotypes may differ in phenotype and function. In addition, given that the impairment of IFN-γ production occurs in the later stage of T-cell exhaustion [55], the production capacities of other cytokines, such as IL-2 and TNF, and cytotoxicity need to be examined further in SARS-CoV-2-specific MHC-I multimer+CD8+ T cells.

Fig. 3.

Functional analysis of SARS-CoV-2-specific MHC-I multimer+CD8+ T cells. MHC-I multimer staining in combination with cytokine secretion assays revealed that both PD-1+ and PD-1– cells among SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells are functional in terms of IFN-γ production

Thus far, the phenotype and functions of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells have been analyzed primarily in peripheral blood [16, 17, 33, 114, 115]. However, previous studies in animal models of respiratory viral infections have shown that tissue-resident memory T cells in the respiratory tract critically contribute to protection from viral infection [116, 117]. In patients with COVID-19, the expression of tissue-residency markers (CD69 and CD103) and activation markers (PD-1 and HLA-DR) is higher in airway CD8+ T cells than in their peripheral blood counterparts [108], indicating that tissue-resident CD8+ T cells with an activated phenotype are enriched in the airways. Therefore, additional studies are needed to investigate whether SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells in the respiratory tract are exhausted or functional in patients with COVID-19.

Moreover, comprehensive investigations on the transcriptional and epigenetic dynamics of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells would provide new insights into the differentiation trajectories of CD8+ T cells and clarify whether CD8+ T cells are truly exhausted during the course of COVID-19.

The development of SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell memory

Accumulating evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell responses are maintained in convalescent individuals up to 10 months post infection, indicating that SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell memory develops successfully and is long lasting [118–124]. As CD8+ T cells that fail to become functional memory T cells differentiate into exhausted T cells, these findings suggest that CD8+ T-cell exhaustion may be limited in the majority of patients with COVID-19.

Among subsets of memory T cells, stem cell-like memory T (TSCM) cells are characterized by a high self-renewal capacity and a multipotent ability to generate diverse memory subsets [125, 126]. Stem-like CD8+ memory T-cell progenitors have been described as being composed of two distinct subsets based on PD-1 and TIGIT expression [127]. Our group recently showed that the majority of SARS-CoV-2-specific TSCM cells from convalescent COVID-19 patients are PD-1–TIGIT– cells, suggesting that these cells are not exhausted-like progenitors [124]. These findings also support SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells being rarely exhausted in patients with COVID-19. Limited exhaustion of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells and successful development of TSCM cells lead to host protection upon re-exposure to SARS-CoV-2 among COVID-19 convalescent individuals.

CD8+ T-cell exhaustion and vaccine-induced memory T-cell responses

Currently available vaccines using diverse platforms have been shown to elicit protective T-cell immunity [4, 7, 128–130]. Currently, COVID-19 vaccines are administered not only to unexposed individuals but also to COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Given that exhausted CD8+ T cells lose their potential to differentiate into memory T cells, the potential CD8+ T-cell exhaustion in individuals who have had COVID-19 can impede vaccine-induced development of T-cell memory. However, because CD8+ T-cell exhaustion is not evident in patients with COVID-19, it is assumed that COVID-19-experienced individuals successfully develop functional CD8+ T-cell memory following vaccination. Recent studies have reported that a single dose of mRNA vaccine robustly induces spike-specific T-cell responses in COVID-19 convalescent individuals [131].

The exhausted-like phenotypes of CD8+ T cells in respiratory viral infections

An exhausted-like phenotype of CD8+ T cells has been reported in several studies of respiratory viral infections using mouse models. PD-1 upregulation on virus-specific CD8+ T cells and an impairment of their effector functions have been observed during infection with respiratory viruses, such as human metapneumovirus or influenza virus [132–134]. Similar to T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infections, the PD-1 pathway primarily mediates functional impairment of CD8+ T cells in acute respiratory virus infection [132, 134]. However, this functional alteration occurs more rapidly than T-cell exhaustion [132]. Furthermore, whether the differentiation state and transcriptional profiles of functionally impaired CD8+ T cells in respiratory viral infections are similar to those of exhausted T cells is not clear. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, little was known about the functional impairment or exhaustion of CD8+ T cells during respiratory viral infections in humans. Further investigations with functional, transcriptomic, epigenetic, and metabolic profiling are needed to clarify T-cell exhaustion in acute respiratory viral infections.

Concluding remarks and perspectives

Since the emergence of COVID-19, global efforts have rapidly increased our knowledge of the immune responses to SARS-CoV-2, including CD8+ T-cell responses. However, information regarding the role of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells in protective immunity is still limited. In addition, the differentiation dynamics of CD8+ T cells during the course of COVID-19, particularly whether SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells become exhausted, remain enigmatic. Further comprehensive studies on the functional, transcriptional, epigenetic, and metabolic landscapes of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells would help answer this question. Moreover, considering that virus-specific effector T cells are recruited to the site of inflammation, SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells in the respiratory tract should be investigated. Deeper investigation of CD8+ T cells will help not only control the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic but also prepare for any upcoming pandemics.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the 2020 Joint Research Project of the Institutes of Science and Technology.

Author contributions

M-SR and E-CS conceived and designed the work; collected and analyzed the relevant reports; and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–3. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramasamy MN, Minassian AM, Ewer KJ, Flaxman AL, Folegatti PM, Owens DR, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2021;396:1979–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephenson KE, Le Gars M, Sadoff J, de Groot AM, Heerwegh D, Truyers C, et al. Immunogenicity of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325:1535–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keech C, Albert G, Cho I, Robertson A, Reed P, Neal S, et al. Phase 1-2 trial of a SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein nanoparticle vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2320–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:355–62. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0331-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JS, Park S, Jeong HW, Ahn JY, Choi SJ, Lee H, et al. Immunophenotyping of COVID-19 and influenza highlights the role of type I interferons in development of severe COVID-19. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabd1554. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Netea MG, Rovina N, Akinosoglou K, Antoniadou A, Antonakos N, et al. Complex immune dysregulation in COVID-19 patients with severe respiratory failure. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:992–1000.e1003. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sette A, Crotty S. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell. 2021;184:861–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Ramirez SI, Mateus J, Dan JM, Moderbacher CR, et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181:1489–501.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Bert N, Tan AT, Kunasegaran K, Tham C, Hafezi M, Chia A, et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature. 2020;584:457–62. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2550-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelde A, Bilich T, Heitmann JS, Maringer Y, Salih HR, Roerden M, et al. SARS-CoV-2-derived peptides define heterologous and COVID-19-induced T cell recognition. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:74–85. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-00808-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiskopf D, Schmitz KS, Raadsen MP, Grifoni A, Okba N, Endeman H, et al. Phenotype and kinetics of SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabd2071. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekine T, Perez-Potti A, Rivera-Ballesteros O, Strålin K, Gorin JB, Olsson A, et al. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183:158–68.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng Y, Mentzer AJ, Liu G, Yao X, Yin Z, Dong D, et al. Broad and strong memory CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells induced by SARS-CoV-2 in UK convalescent individuals following COVID-19. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1336–45. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0782-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMahan K, Yu J, Mercado NB, Loos C, Tostanoski LH, Chandrashekar A, et al. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2021;590:630–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhuang Z, Lai X, Sun J, Chen Z, Zhang Z, Dai J, et al. Mapping and role of T cell response in SARS-CoV-2-infected mice. J Exp Med. 2021;218:e20202187. doi: 10.1084/jem.20202187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song JW, Zhang C, Fan X, Meng FP, Xu Z, Xia P, et al. Immunological and inflammatory profiles in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3410. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17240-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathew D, Giles JR, Baxter AE, Oldridge DA, Greenplate AR, Wu JE, et al. Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science. 2020;369:eabc8511. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuri-Cervantes L, Pampena MB, Meng W, Rosenfeld AM, Ittner C, Weisman AR, et al. Comprehensive mapping of immune perturbations associated with severe COVID-19. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabd7114. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazzoni A, Salvati L, Maggi L, Capone M, Vanni A, Spinicci M, et al. Impaired immune cell cytotoxicity in severe COVID-19 is IL-6 dependent. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:4694–703. doi: 10.1172/JCI138554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varchetta S, Mele D, Oliviero B, Mantovani S, Ludovisi S, Cerino A, et al. Unique immunological profile in patients with COVID-19. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:604–12. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00557-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Biasi S, Meschiari M, Gibellini L, Bellinazzi C, Borella R, Fidanza L, et al. Marked T cell activation, senescence, exhaustion and skewing towards TH17 in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3434. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17292-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng HY, Zhang M, Yang CX, Zhang N, Wang XC, Yang XP, et al. Elevated exhaustion levels and reduced functional diversity of T cells in peripheral blood may predict severe progression in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:541–3. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0401-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng M, Gao Y, Wang G, Song G, Liu S, Sun D, et al. Functional exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:533–5. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0402-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diao B, Wang C, Tan Y, Chen X, Liu Y, Ning L, et al. Reduction and functional exhaustion of T cells in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Front Immunol. 2020;11:827. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laing AG, Lorenc A, Del Molino Del Barrio I, Das A, Fish M, Monin L, et al. A dynamic COVID-19 immune signature includes associations with poor prognosis. Nat Med. 2020;26:1623–35. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schultheiß C, Paschold L, Simnica D, Mohme M, Willscher E, von Wenserski L, et al. Next-generation sequencing of T and B cell receptor repertoires from COVID-19 patients showed signatures associated with severity of disease. Immunity. 2020;53:442–455.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilk AJ, Rustagi A, Zhao NQ, Roque J, Martínez-Colón GJ, McKechnie JL, et al. A single-cell atlas of the peripheral immune response in patients with severe COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1070–6. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0944-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu C, Martins AJ, Lau WW, Rachmaninoff N, Chen J, Imberti L, et al. Time-resolved systems immunology reveals a late juncture linked to fatal COVID-19. Cell. 2021;184:1836–57.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rha MS, Jeong HW, Ko JH, Choi SJ, Seo IH, Lee JS, et al. PD-1-expressing SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8(+) T cells are not exhausted, but functional in patients with COVID-19. Immunity. 2021;54:44–52.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rha MS, Kim AR, Shin EC. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses in patients with COVID-19 and unexposed individuals. Immune Netw. 2021;21:e2. doi: 10.4110/in.2021.21.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipsitch M, Grad YH, Sette A, Crotty S. Cross-reactive memory T cells and herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:709–13. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Z, John Wherry E. T cell responses in patients with COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:529–36. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0402-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altmann DM, Boyton RJ. SARS-CoV-2 T cell immunity: specificity, function, durability, and role in protection. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabd6160. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd6160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karlsson AC, Humbert M, Buggert M. The known unknowns of T cell immunity to COVID-19. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabe8063. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe8063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Candia P, Prattichizzo F, Garavelli S, Matarese G. T Cells: warriors of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Trends Immunol. 2021;42:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cui WG, Kaech SM. Generation of effector CD8+ T cells and their conversion to memory T cells. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:151–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaech SM, Cui W. Transcriptional control of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:749–61. doi: 10.1038/nri3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ. Heterogeneity and cell-fate decisions in effector and memory CD8(+) T cell differentiation during viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hashimoto M, Kamphorst AO, Im SJ, Kissick HT, Pillai RN, Ramalingam SS, et al. CD8 T cell exhaustion in chronic infection and cancer: opportunities for interventions. Annu Rev Med. 2018;69:301–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-012017-043208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McLane LM, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Wherry EJ. CD8 T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection and cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019;37:457–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moskophidis D, Lechner F, Pircher H, Zinkernagel RM. Virus persistence in acutely infected immunocompetent mice by exhaustion of antiviral cytotoxic effector T cells. Nature. 1993;362:758–61. doi: 10.1038/362758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallimore A, Glithero A, Godkin A, Tissot AC, Plückthun A, Elliott T, et al. Induction and exhaustion of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes visualized using soluble tetrameric major histocompatibility complex class I-peptide complexes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1383–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, Brown JA, Moodley ES, Reddy S, et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature. 2006;443:350–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baitsch L, Baumgaertner P, Devêvre E, Raghav SK, Legat A, Barba L, et al. Exhaustion of tumor-specific CD8(+) T cells in metastases from melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2350–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI46102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pauken KE, Wherry EJ. Overcoming T cell exhaustion in infection and cancer. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:265–76. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fourcade J, Sun Z, Benallaoua M, Guillaume P, Luescher IF, Sander C, et al. Upregulation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression is associated with tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cell dysfunction in melanoma patients. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2175–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsuzaki J, Gnjatic S, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Beck A, Miller A, Tsuji T, et al. Tumor-infiltrating NY-ESO-1-specific CD8+ T cells are negatively regulated by LAG-3 and PD-1 in human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7875–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003345107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riches JC, Davies JK, McClanahan F, Fatah R, Iqbal S, Agrawal S, et al. T cells from CLL patients exhibit features of T-cell exhaustion but retain capacity for cytokine production. Blood. 2013;121:1612–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jin HT, Anderson AC, Tan WG, West EE, Ha SJ, Araki K, et al. Cooperation of Tim-3 and PD-1 in CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14733–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009731107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, Ahmed R. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J Virol. 2003;77:4911–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4911-4927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mackerness KJ, Cox MA, Lilly LM, Weaver CT, Harrington LE, Zajac AJ. Pronounced virus-dependent activation drives exhaustion but sustains IFN-gamma transcript levels. J Immunol. 2010;185:3643–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wherry EJ, Barber DL, Kaech SM, Blattman JN, Ahmed R. Antigen-independent memory CD8 T cells do not develop during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16004–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407192101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shin H, Blackburn SD, Blattman JN, Wherry EJ. Viral antigen and extensive division maintain virus-specific CD8 T cells during chronic infection. J Exp Med. 2007;204:941–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matloubian M, Concepcion RJ, Ahmed R. CD4+ T cells are required to sustain CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses during chronic viral infection. J Virol. 1994;68:8056–63. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8056-8063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aubert RD, Kamphorst AO, Sarkar S, Vezys V, Ha SJ, Barber DL, et al. Antigen-specific CD4 T-cell help rescues exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:21182–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118450109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scharping NE, Rivadeneira DB, Menk AV, Vignali P, Ford BR, Rittenhouse NL, et al. Mitochondrial stress induced by continuous stimulation under hypoxia rapidly drives T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:205–15. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-00834-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yokosuka T, Takamatsu M, Kobayashi-Imanishi W, Hashimoto-Tane A, Azuma M, Saito T. Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1201–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schildberg FA, Klein SR, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. Coinhibitory pathways in the B7-CD28 ligand-receptor family. Immunity. 2016;44:955–72. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hui E, Cheung J, Zhu J, Su X, Taylor MJ, Wallweber HA, et al. T cell costimulatory receptor CD28 is a primary target for PD-1-mediated inhibition. Science. 2017;355:1428–33. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1027–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439:682–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shin EC, Rehermann B. Taking the brake off T cells in chronic viral infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:276–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0306-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hirano F, Kaneko K, Tamura H, Dong H, Wang S, Ichikawa M, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 and PD-1 by monoclonal antibodies potentiates cancer therapeutic immunity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1089–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Curiel TJ, Wei S, Dong H, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 improves myeloid dendritic cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2003;9:562–7. doi: 10.1038/nm863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359:1350–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Kefford R, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–13. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, Halwani A, Scott EC, Gutierrez M, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anderson AC, Joller N, Kuchroo VK. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: co-inhibitory receptors with specialized functions in immune regulation. Immunity. 2016;44:989–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Attanasio J, Wherry EJ. Costimulatory and coinhibitory receptor pathways in infectious disease. Immunity. 2016;44:1052–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Blackburn SD, Shin H, Haining WN, Zou T, Workman CJ, Polley A, et al. Coregulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion by multiple inhibitory receptors during chronic viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:29–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gros A, Robbins PF, Yao X, Li YF, Turcotte S, Tran E, et al. PD-1 identifies the patient-specific CD8(+) tumor-reactive repertoire infiltrating human tumors. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2246–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI73639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wherry EJ, Ha SJ, Kaech SM, Haining WN, Sarkar S, Kalia V, et al. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:670–84. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kao C, Oestreich KJ, Paley MA, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Ali MA, et al. Transcription factor T-bet represses expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 and sustains virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses during chronic infection. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:663–71. doi: 10.1038/ni.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Paley MA, Kroy DC, Odorizzi PM, Johnnidis JB, Dolfi DV, Barnett BE, et al. Progenitor and terminal subsets of CD8+ T cells cooperate to contain chronic viral infection. Science. 2012;338:1220–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1229620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Man K, Gabriel SS, Liao Y, Gloury R, Preston S, Henstridge DC, et al. Transcription factor IRF4 promotes CD8(+) T cell exhaustion and limits the development of memory-like T cells during chronic infection. Immunity. 2017;47:1129–41.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khan O, Giles JR, McDonald S, Manne S, Ngiow SF, Patel KP, et al. TOX transcriptionally and epigenetically programs CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Nature. 2019;571:211–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1325-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beltra JC, Manne S, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Kurachi M, Giles JR, Chen Z, et al. Developmental relationships of four exhausted CD8(+) T cell subsets reveals underlying transcriptional and epigenetic landscape control mechanisms. Immunity. 2020;52:825–41.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Martinez GJ, Pereira RM, Äijö T, Kim EY, Marangoni F, Pipkin ME, et al. The transcription factor NFAT promotes exhaustion of activated CD8(+) T cells. Immunity. 2015;42:265–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shin H, Blackburn SD, Intlekofer AM, Kao C, Angelosanto JM, Reiner SL, et al. A role for the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 in CD8(+) T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2009;31:309–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Quigley M, Pereyra F, Nilsson B, Porichis F, Fonseca C, Eichbaum Q, et al. Transcriptional analysis of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells shows that PD-1 inhibits T cell function by upregulating BATF. Nat Med. 2010;16:1147–51. doi: 10.1038/nm.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Doering TA, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Paley MA, Ziegler CG, Wherry EJ. Network analysis reveals centrally connected genes and pathways involved in CD8+ T cell exhaustion versus memory. Immunity. 2012;37:1130–44. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sen DR, Kaminski J, Barnitz RA, Kurachi M, Gerdemann U, Yates KB, et al. The epigenetic landscape of T cell exhaustion. Science. 2016;354:1165–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aae0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pauken KE, Sammons MA, Odorizzi PM, Manne S, Godec J, Khan O, et al. Epigenetic stability of exhausted T cells limits durability of reinvigoration by PD-1 blockade. Science. 2016;354:1160–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Pearce EL. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1345–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.O’Sullivan D, Pearce EL. Targeting T cell metabolism for therapy. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chang CH, Pearce EL. Emerging concepts of T cell metabolism as a target of immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:364–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van der Windt GJ, Pearce EL. Metabolic switching and fuel choice during T-cell differentiation and memory development. Immunol Rev. 2012;249:27–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bengsch B, Johnson AL, Kurachi M, Odorizzi PM, Pauken KE, Attanasio J, et al. Bioenergetic insufficiencies due to metabolic alterations regulated by the inhibitory receptor PD-1 are an early driver of CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Immunity. 2016;45:358–73. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Patsoukis N, Bardhan K, Chatterjee P, Sari D, Liu B, Bell LN, et al. PD-1 alters T-cell metabolic reprogramming by inhibiting glycolysis and promoting lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6692. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chang CH, Qiu J, O'Sullivan D, Buck MD, Noguchi T, Curtis JD, et al. Metabolic competition in the tumor microenvironment is a driver of cancer progression. Cell. 2015;162:1229–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Marraco SAF, Neubert NJ, Verdeil G, Speiser DE. Inhibitory receptors beyond T cell exhaustion. Front Immunol. 2015;6:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Singer M, Wang C, Cong L, Marjanovic ND, Kowalczyk MS, Zhang H, et al. A distinct gene module for dysfunction uncoupled from activation in tumor-infiltrating T cells (vol 166, pg 1500, 2016) Cell. 2017;171:1221–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fuertes Marraco SA, Neubert NJ, Verdeil G, Speiser DE. Inhibitory receptors beyond T cell exhaustion. Front Immunol. 2015;6:310. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:486–99. doi: 10.1038/nri3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Legat A, Speiser DE, Pircher H, Zehn D, Fuertes Marraco SA. Inhibitory receptor expression depends more dominantly on differentiation and activation than “exhaustion” of human CD8 T cells. Front Immunol. 2013;4:455. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Singer M, Wang C, Cong L, Marjanovic ND, Kowalczyk MS, Zhang H, et al. A distinct gene module for dysfunction uncoupled from activation in tumor-infiltrating T cells. Cell. 2016;166:1500–11.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rydyznski Moderbacher C, Ramirez SI, Dan JM, Grifoni A, Hastie KM, Weiskopf D, et al. Antigen-specific adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in acute COVID-19 and associations with age and disease severity. Cell. 2020;183:996–1012.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schwarzkopf S, Krawczyk A, Knop D, Klump H, Heinold A, Heinemann FM, et al. Cellular immunity in COVID-19 convalescents with PCR-confirmed infection but with undetectable SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:122–9. doi: 10.3201/eid2701.203772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liao M, Liu Y, Yuan J, Wen Y, Xu G, Zhao J, et al. Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:842–4. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Adamo S, Chevrier S, Cervia C, Zurbuchen Y, Raeber ME, Yang L, et al. Profound dysregulation of T cell homeostasis and function in patients with severe COVID-19. Allergy. 2021. 10.1111/all.14866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Szabo PA, Dogra P, Gray JI, Wells SB, Connors TJ, Weisberg SP, et al. Longitudinal profiling of respiratory and systemic immune responses reveals myeloid cell-driven lung inflammation in severe COVID-19. Immunity. 2021;54:797–814.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang JY, Wang XM, Xing X, Xu Z, Zhang C, Song JW, et al. Single-cell landscape of immunological responses in patients with COVID-19. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1107–18. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0762-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vitte J, Diallo AB, Boumaza A, Lopez A, Michel M, Allardet-Servent J, et al. A granulocytic signature identifies COVID-19 and its severity. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:1985–96. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kusnadi A, Ramírez-Suástegui C, Fajardo V, Chee SJ, Meckiff BJ, Simon H, et al. Severely ill COVID-19 patients display impaired exhaustion features in SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8(+) T cells. Sci Immunol. 2021;6:eabe4782. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Koh JY, Shin EC. Landscapes of SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD8(+) T cells: heterogeneity of host immune responses against SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:146. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00589-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Altman JD, Moss PA, Goulder PJ, Barouch DH, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Bell JI, et al. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–96. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schulien I, Kemming J, Oberhardt V, Wild K, Seidel LM, Killmer S, et al. Characterization of pre-existing and induced SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8(+) T cells. Nat Med. 2021;27:78–85. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Habel JR, Nguyen T, van de Sandt CE, Juno JA, Chaurasia P, Wragg K, et al. Suboptimal SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8(+) T cell response associated with the prominent HLA-A*02:01 phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:24384–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015486117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.McMaster SR, Wilson JJ, Wang H, Kohlmeier JE. Airway-resident memory CD8 T cells provide antigen-specific protection against respiratory virus challenge through rapid IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 2015;195:203–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pizzolla A, Nguyen T, Smith JM, Brooks AG, Kedzieska K, Heath WR, et al. Resident memory CD8(+) T cells in the upper respiratory tract prevent pulmonary influenza virus infection. Sci Immunol. 2017;2:eaam6970. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aam6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bilich T, Nelde A, Heitmann JS, Maringer Y, Roerden M, Bauer J, et al. T cell and antibody kinetics delineate SARS-CoV-2 peptides mediating long-term immune responses in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabf7517. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf7517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, Hastie KM, Yu ED, Faliti CE, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371:eabf4063. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zuo J, Dowell AC, Pearce H, Verma K, Long HM, Begum J, et al. Robust SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity is maintained at 6 months following primary infection. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:620–6. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-00902-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jiang XL, Wang GL, Zhao XN, Yan FH, Yao L, Kou ZQ, et al. Lasting antibody and T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients three months after infection. Nat Commun. 2021;12:897. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21155-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Breton G, Mendoza P, Hägglöf T, Oliveira TY, Schaefer-Babajew D, Gaebler C, et al. Persistent cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Exp Med. 2021;218:e20202515. doi: 10.1084/jem.20202515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sherina N, et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2-specific B and T cell responses in convalescent COVID-19 patients 6-8 months after the infection. Med (N Y) 2021;2:281–95.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Jung JH, Rha MS, Sa M, Choi HK, Jeon JH, Seok H, et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell memory is sustained in COVID-19 convalescent patients for 10 months with successful development of stem cell-like memory T cells. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4043. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24377-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gattinoni L, Lugli E, Ji Y, Pos Z, Paulos CM, Quigley MF, et al. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med. 2011;17:1290–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gattinoni L, Speiser DE, Lichterfeld M, Bonini C. T memory stem cells in health and disease. Nat Med. 2017;23:18–27. doi: 10.1038/nm.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Galletti G, De Simone G, Mazza E, Puccio S, Mezzanotte C, Bi TM, et al. Two subsets of stem-like CD8(+) memory T cell progenitors with distinct fate commitments in humans. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1552–62. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0791-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, Jackson LA, Roberts PC, Makhene M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2427–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ewer KJ, Barrett JR, Belij-Rammerstorfer S, Sharpe H, Makinson R, Morter R, et al. T cell and antibody responses induced by a single dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine in a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:270–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sadoff J, Le Gars M, Shukarev G, Heerwegh D, Truyers C, de Groot AM, et al. Interim results of a phase 1-2a trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1824–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Reynolds CJ, Pade C, Gibbons JM, Butler DK, Otter AD, Menacho K, et al. Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection rescues B and T cell responses to variants after first vaccine dose. Science. 2021. 10.1126/science.abh1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 132.Erickson JJ, Gilchuk P, Hastings AK, Tollefson SJ, Johnson M, Downing MB, et al. Viral acute lower respiratory infections impair CD8+ T cells through PD-1. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2967–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI62860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rutigliano JA, Sharma S, Morris MY, Oguin TH, McClaren JL, Doherty PC, et al. Highly pathological influenza A virus infection is associated with augmented expression of PD-1 by functionally compromised virus-specific CD8+ T cells. J Virol. 2014;88:1636–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02851-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Erickson JJ, Lu P, Wen S, Hastings AK, Gilchuk P, Joyce S, et al. Acute viral respiratory infection rapidly induces a CD8+ T cell exhaustion-like phenotype. J Immunol. 2015;195:4319–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]