Abstract

Prostaglandin H synthase (PGHS) catalyzes the biosynthesis of PGG2 and PGH2, the precursor of all prostanoids, from arachidonic acid (AA). PGHS exhibits two enzymatic activities following a branched-chain radical mechanism: 1) a peroxidase activity (POX) that utilizes hydroperoxide through heme redox cycles to generate the critical Tyr385 tyrosyl radical for coupling both enzyme activities; 2) the cyclooxygenase (COX) activity inserting two oxygen molecules into AA to generate endoperoxide/hydroperoxide PGG2 through a series of radical intermediates. Upon the generation of Tyr385 radical, COX catalysis is initiated, with C13 pro-S hydrogen abstraction from AA by Tyr385 radical to generate arachidonyl substrate radical. Oxygen provides a large driving force for the subsequent fast steps leading to the formation of PGG2, including radical redistributions, ring formations, and rearrangements. On the other hand, if the supply of oxygen is severed, equilibrium between arachidonyl radical and tyrosyl radical(s) biases largely towards the latter. In this study, we demonstrate that such equilibrium is shifted by many factors, including temperature, chemical structures of fatty acid substrates and limited supply of oxygen. We also, for the first time, reveal that this equilibrium is significantly affected by co-substrates of POX. The presence of efficient POX co-substrates, which reduces heme to its ferric state, apparently biases the equilibrium towards arachidonyl radical. Therefore a dynamic interplay exists between the two activities of PGHS.

Keywords: Arachidonic pentadienyl radical, cyclooxygenase, peroxidase co-substrate, prostaglandin H synthase, radical dynamics, radical intermediate, tyrosyl radical

1. INTRODUCTION

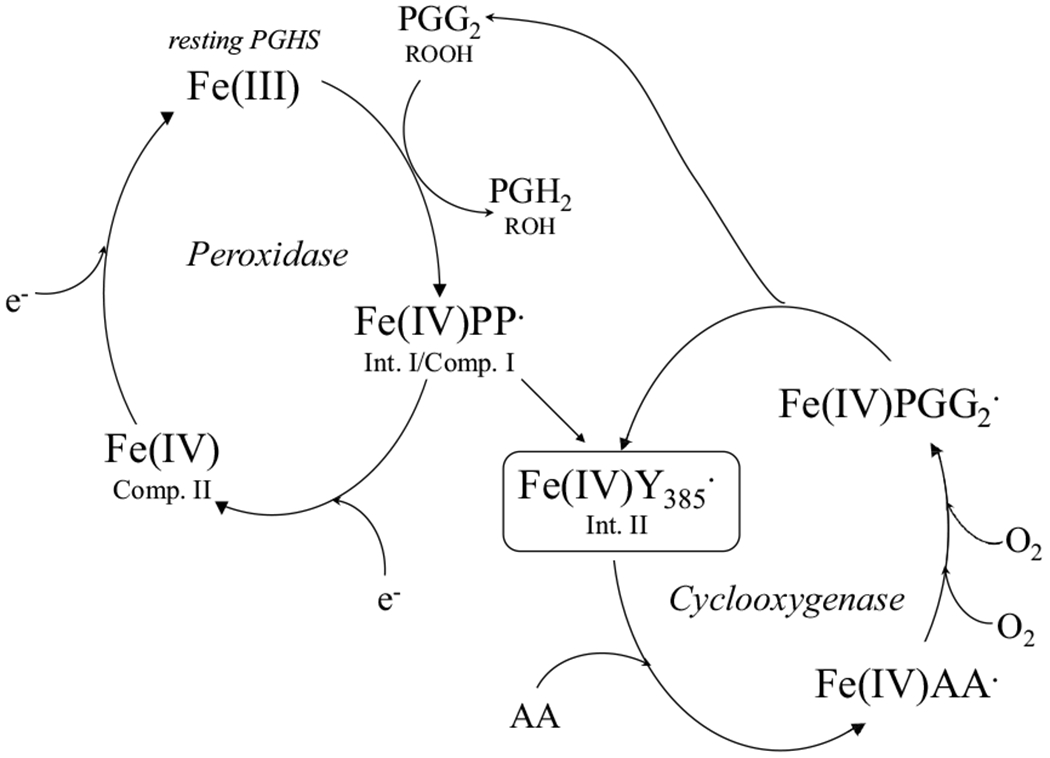

Prostaglandin H synthase (PGHS) catalyzes the biosynthesis of PGG2 and PGH2, the precursor of all prostanoids, from arachidonic acid (AA). PGHS has two isoforms, PGHS-1 and -2, which both have a heme prosthetic group and exhibit two enzymatic activities, a peroxidase activity (POX) and a cyclooxygenase activity (COX), following the same branched-chain radical mechanism, which is supported by much experimental evidence [1,2,3]. In its POX catalysis, PGHS first reacts with hydroperoxide to generate an intermediate (Intermediate I), which contains an oxyferryl heme with a porphyrin cation radical (Scheme 1). Intermediate I promptly converts to intermediate II through electron transfer from tyrosine 385 (Y385) to the porphyrin cation radical to generate a critical tyrosyl radical (Y385·) for COX catalysis. High oxidation state heme, Fe(IV)=O, is reduced back to Fe(III) by endogenous or exogenous co-substrates, ready for the reaction with another molecule of hydroperoxide (Scheme 1). The POX-generated Y385· radical initiates COX activity, which converts AA to PGG2, an endoperoxide/hydroperoxide, and regenerates Y385· radical, ready for the next COX cycle (Scheme 2). PGG2 can be reduced to PGH2 by PGHS POX activity, enabling the propagation of PGHS catalysis. Since Y385· radical is regenerated in each COX cycle, PGHS COX activity becomes independent of its POX activity after the generation of Y385· tyrosyl radical; the two activities therefore bifurcate at Intermediate II.

Scheme 1. Current branched-chain radical mechanistic model of PGHS catalysis.

“Fe(IV)PP·”: Intermediate I or Compound I containing oxyferryl iron and porphyrin cation radical. “Fe(IV)Y385·”: Intermediate II containing oxyferryl heme and oxygen-centered tyrosyl radical on tyrosine 385; “Fe(IV)”: Compound II containing oxyferryl heme; “AA·”: arachidonyl carbon centered radical; “PPG2·”: PPG2 oxygen-centered radical.

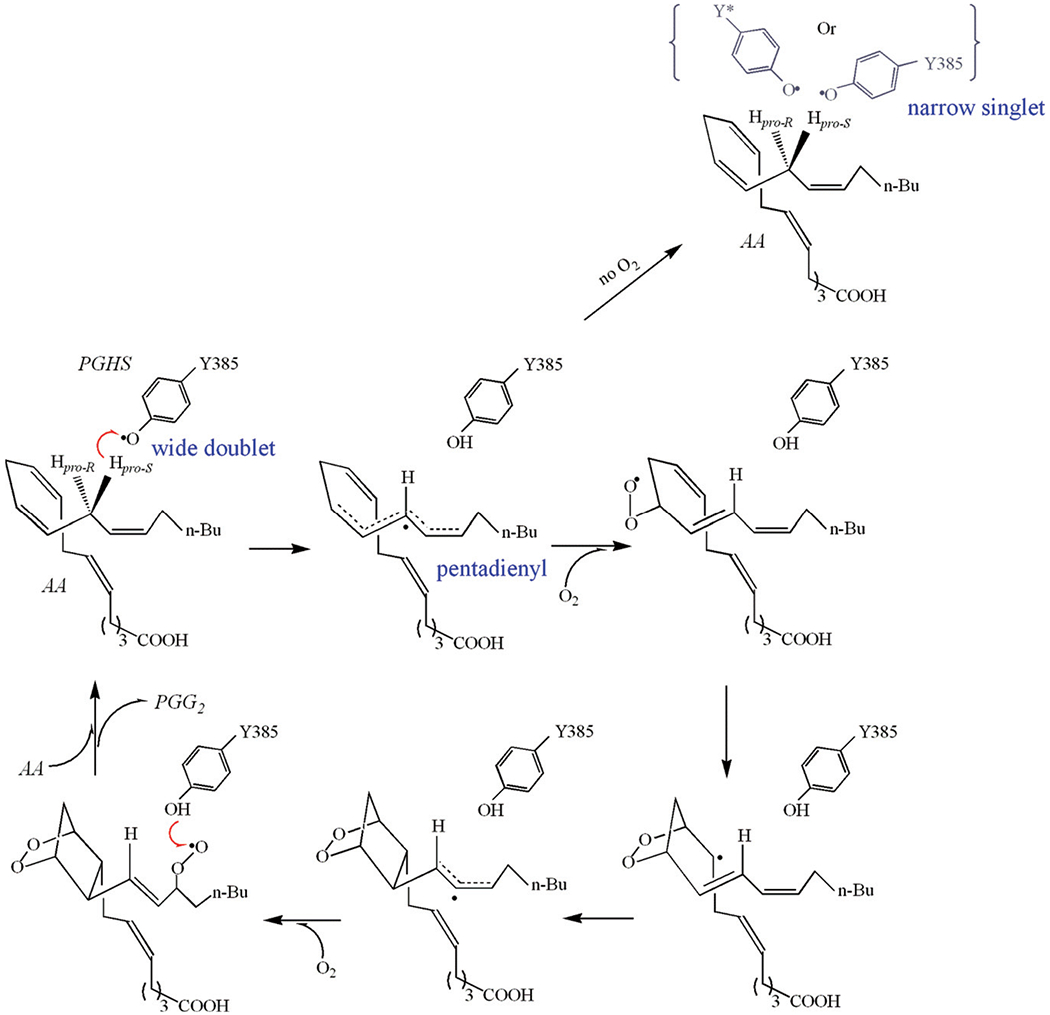

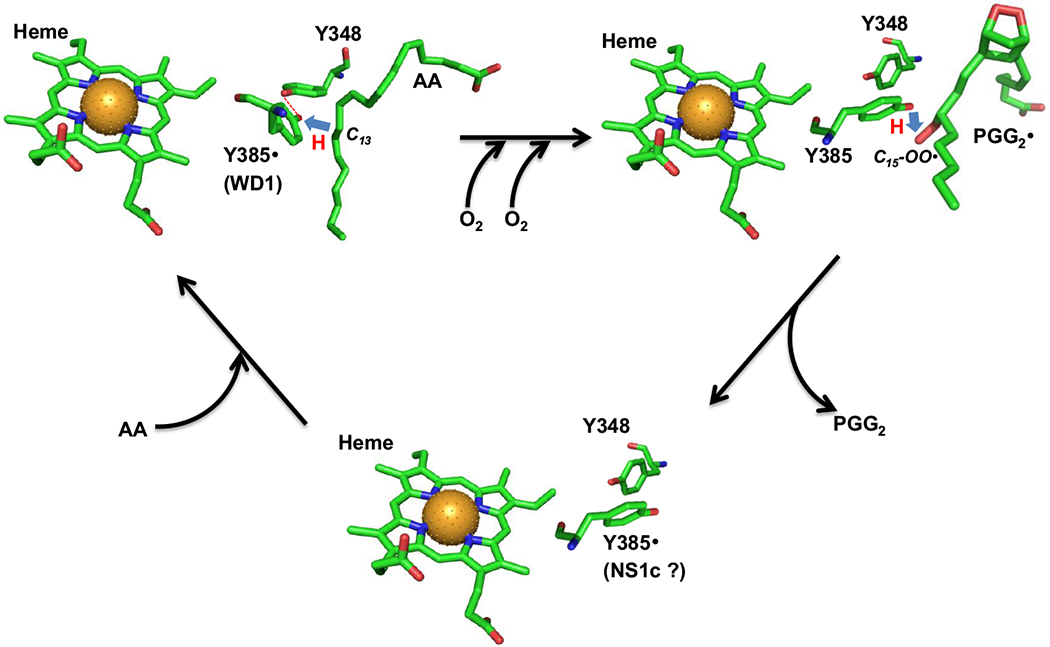

Scheme 2. Radical mechanism of COX reactions.

The hydrogen abstractions are represented with red arrows: 1) pro-S hydrogen abstraction from AA by tyrosyl radical Y385·; 2) hydrogen abstraction from Y385 by PPG2· radical. EPR lineshapes of the radical intermediates which have been freeze-trapped and characterized are marked in blue. The location of the alternative tyrosyl radical, with narrow singlet EPR lineshape, is not clear and represented in grey color. This alternative radical is likely either located on a surrogate tyrosine or on Y385 with a different rotational conformation. The delocalization of the spin is marked with dashed line.

The current mechanistic model of COX activity outlines perfectly the pathway converting AA to PGG2 [1]. According to this mechanism, COX catalysis starts with C-13 pro-S hydrogen abstraction from AA by Y385· radical, generating an arachidonyl carbon-centered radical, and in the subsequent reactions, two oxygen molecules are inserted into AA and by cyclization, isomerization, and radical migration the PGG2· radical is formed. The last step of COX catalysis is a hydrogen transfer from Y385 to PGG2·, producing PGG2 and regenerating the Y385· radical for the next COX cycle (Scheme 2). The salient feature of the COX mechanism is that COX catalysis proceeds through a series of radical intermediates. Since this COX mechanism was proposed about 50 years ago [4,5], great efforts have been made to capture and characterize the proposed radical intermediates. However, quite limited success has been achieved in these efforts and only the first two radical intermediates in COX cycle, namely the oxygen-centered Y385· radical and arachidonyl carbon-centered radical, have been successfully trapped and characterized. Oxygen provides such strong driving forces for the subsequent steps of COX reactions that no other radical intermediate before the regenerated Y385· radical has been captured for characterization.

Tyrosyl radical Y385· has been freeze-trapped in both PGHS-1 and -2 under various experimental conditions [6,7,8]. EPR characterization of Y385· radical shows a lineshape of 34 – 35 G wide doublet (WD1) in PGHS-1 or 30 G wide doublet (WD2) in PGHS-2 [8] (Table S1). After its generation, rotation of Y385 phenyl ring or spin migration to adjacent tyrosine residue(s) results in the change of EPR signatures with slightly narrower linewidth and diminished hyperfine splitting, so called wide singlet (WS1, and WS2 in PGHS-2) (Table S1). Tyrosyl radicals observed in PGHS-1 and -2 treated with COX inhibitors are believed to locate on Y504 and exhibit narrow singlet EPR lineshapes but with clear hyperfine structures (NS1a and NS2a) [9] (Table S1). EPR singlet of even narrower linewidth and without any defined hyperfine structure is observed in PGHS at high [AA] (NS1b) (Table S1). These different EPR lineshapes exhibited by the tyrosyl radical intermediates in PGHS highlight its dynamic nature in COX catalysis. Among the different tyrosyl radicals, WD1 or WD2 are kinetically competent in hydrogen abstraction from AA and other fatty acid substrates [6,7,10,11].

The next radical intermediate in the COX serial reactions, AA-derived carbon-centered radical has been successfully freeze-trapped and characterized using EPR in anaerobic reactions of PGHS Intermediate II with AA [12]. Carbon-centered arachidonyl radical exhibits EPR signatures typical of a pentadienyl radical, with 80 – 83 G linewidth and hyperfine splitting due to the interacting hydrogens [12] (Table S1). The hyperfine structures were clearly defined using AA analogs with deuterium labeled on different carbons from C10 to C16 [11,13]. Interestingly, PGHS-1 and -2 exhibit some discrepancy in the freeze-trapped radical intermediates under the same experimental conditions. In the reactions of anaerobic PGHS-2 reaction with AA/ethyl hydroperoxide (EtOOH), either a pentadienyl arachidonyl radical or a mixture of pentadienyl AA radical and WS tyrosyl radical was captured. On the other hand, in PGHS-1, in addition to the EPR signatures similar to those for PGHS-2, radical(s) with EPR signatures of a narrow singlet EPR lineshape or a mixture of pentadienyl radical and narrow singlet is more often freeze-trapped [10]. In fact, in the anaerobic PGHS-1 reaction with regular AA, EPR signatures observed are predominately narrow singlet. Two types of narrow singlet have been observed, one is similar to the tyrosyl radical freeze-trapped in the inhibitor-treated PGHS-1, NS1a, and may be due to binding of AA in PGHS-1 in a reverse orientation, acting as an inhibitor. The other type of narrow singlet EPR signal exhibits a linewidth of 23 – 25 G without any discrete hyperfine structure and has been named NS1c (Table S1). NS1c was later shown to be majorly a tyrosyl radical [14] which exists in an equilibrium with AA pentadienyl radical. The equilibrium largely biases towards the tyrosyl radical in the absence of oxygen; oxygen or nitric oxide (NO) can react with AA radical and therefore shift the equilibrium towards AA radical irreversibly (Scheme 2) [10,15,16]. Location of the NS1c tyrosyl radical still remains unidentified, although likely residing on tyrosine(s) adjacent to Y385, such as Y348, or on Y385 but with a conformation different from that in WD1 (Scheme 2).

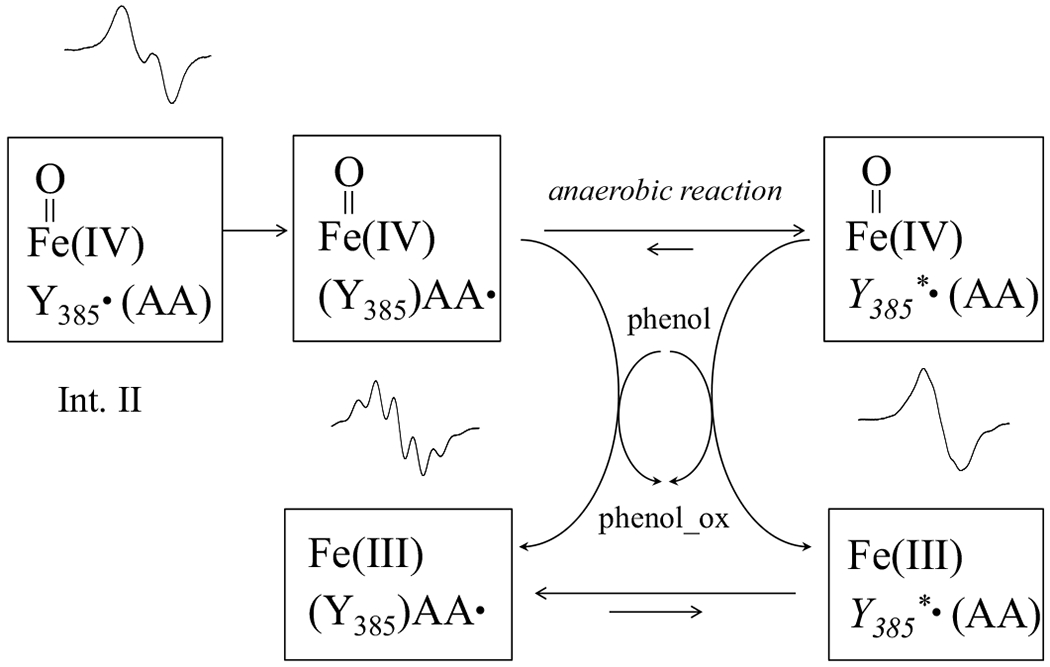

In this study, we demonstrated that the equilibrium in PGHS-1 between AA pentadienyl radical and NS1c tyrosyl radical is affected by many factors, including temperature, chemical structures of fatty acid substrates, amounts of AA and/or oxygen. This study also, for the first time, reveals that this equilibrium is significantly shifted towards AA pentadienyl radical by efficient POX co-substrates (Table S2), suggesting dynamic interplays between POX and COX after Intermediate II formation (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Hypothetical mechanism of the modulation on the dynamics between AA and NS1c tyrosyl radicals by peroxidase co-substrates in PGHS-1.

In the absence of oxygen, the dynamics between AA pentadienyl and NS1c tyrosyl radicals is affected by POX cosubstrates, which reduce heme from its high oxidation state, oxyferryl heme, back to ferric state. Ferric heme appears to favor AA pentadienyl radical.

2. EXPERIMENTAL

2.1. Chemicals

Hemin was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) or Porphyrin Products (Logan, UT, USA). Tween 20 was from Anatrace (Maumee, OH, USA). Arachidonic acid, 11, 14-eicosadienoic acid, 8, 11, 14-eicosatrienoic acid and 5, 8, 11, 14, 17-eicosapentaenoic acid were purchased from Nu-Chek Prep, Inc. (Elysian, MN, USA). 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15-d8-arachidonic acid was from Sigma.

2.2. Preparation of PGHS-1

Ovine PGHS-1 was purified as apoenzyme from ram seminal vesicles following the published procedures and the PGHS-1 holoenzyme was reconstituted as previously described [17]. Unbound heme was removed with DE52 resin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 10DG size exclusion column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). COX activity was assayed polaro-graphically at 30 °C with an oxygen electrode (YSI Model 5331, Yellow Springs, OH) and a YSI Model 53 monitor [17]. The buffer used was 0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.2 containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 10% glycerol. The kcat of PGHS-1 COX activity for AA consumption was typically 65 – 100 s−1 (assuming 2 mol O2/mol AA). The concentration of PGHS-1 was determined using an extinction coefficient of 165 mM−1 cm−1 for heme [17].

2.3. Preparation of EPR samples

Several methods were used in previous studies to freeze-trap AA derived radical intermediate in PGHS-1. One method had PGHS-1 reacted anaerobically with EtOOH to generate significant amount of Y385· radical, which was then reacted with AA for a few seconds [15]. Alternatively, anaerobic PGHS-1 was reacted with a mixture of EtOOH/AA; or anaerobic PGHS-1 was first bound with AA and then reacted with EtOOH [16]. However, the radical intermediates freeze-trapped in PGHS-1 using these methods gave complicated EPR, ranging from a mixture of majorly a tyrosyl radical plus some features of an AA radical to nearly pure alternative tyrosyl radicals, NS1a or NS1c [8,10]. The fact that alternative tyrosyl radical NS1c was captured most frequently in PGHS-1 indicates that the equilibrium between AA and the alternative tyrosyl radical biases towards the latter under these experimental conditions [10,15]. On the other hand, more AA pentadienyl radical was freeze-trapped by reacting high concentration of PGHS-1 directly with excess AA aerobically [12], in this case, O2 in the system was exhausted quickly in the first several COX cycles. A modified version of the latter reaction was conducted. O2 in PGHS-1 solution first replaced with N2 and the reaction of PGHS-1 with AA was initiated by the injection of AA together with low level of oxygen. The small amount of O2 was quickly exhausted through COX reactions, and PGG2 thus generated reacted with PGHS-1 to efficiently generate more Y385· radical and propagate the PGHS-1 reaction. The major part of the PGHS-1 reaction with AA was thus anaerobic. One drawback of this method was the lower yield of radical since only low level of peroxide, mostly PGG2, reacted with PGHS-1 and therefore Y385· radical remained low. Typical amount of radical freeze-trapped in this study was ~ 5 - 10% of the total PGHS-1.

EPR samples were prepared by injecting the desired volume of AA or other fatty acids stocks in ethanol into and mixed with 250 μl PGHS-1 solutions placed in EPR tubes. The fatty acid stocks were prepared so that the injected volume containing desired amount of oxygen. PGHS-1 solution was rendered anaerobic by blowing purified N2 over the surface of the solution for ≥ 30 min. Injection and mixing of the substrates were also conducted under continuous flow of N2. The reactants were mixed with a nichrome wire loop and the reaction temperature was controlled in a Fisher water bath. The reaction temperature was 281 K except for the temperature dependence study, where it varied from 273 to 305 K. EPR samples were frozen in Dry Ice/Ethanol mixture after 4 – 10 s reactions. The EPR samples were kept in liquid N2 before EPR measurements.

2.4. EPR Spectrometry

EPR spectra were recorded with a Bruker EMX spectrometer (Billerica, MA) using the following setting: microwave frequency, 9.2 - 9.3 GHz; modulation amplitude, 2.0 G; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; time constant, 328 ms; microwave power, 1.0 mW, and temperature, 118 – 125 K. Radical concentrations were determined by double integration of the EPR signals with reference to a 1 mM copper sulfate standard. EPR simulation was conducted with SimFonia programs furnished with the EMX system.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Radical intermediate freeze-trapped in the reaction of PGHS-1 with varying levels of AA

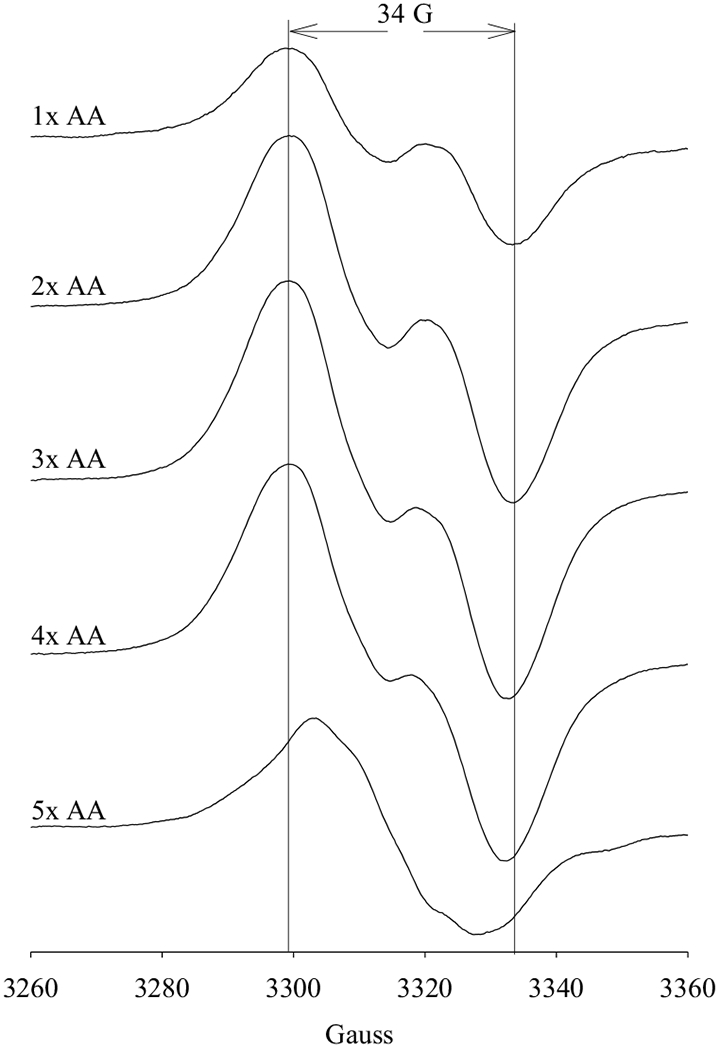

PGHS-1 was reacted with different concentrations of AA in the presence of low level of O2 (0.2 eq.) (Figure 1). All the freeze-trapped samples exhibited EPR signatures typical of tyrosyl radicals (Figure 1 and Table S1) [8]. However, the EPR lineshape exhibited clear dependence on the [AA]/[PGHS-1] ratio. In the reaction of PGHS-1 with stoichiometric AA, a wide doublet (WD) was observed with a linewidth of 34 G (Figure 1). In the reactions of PGHS-1 with AA increasing from 2 to 4 eq., the EPR lineshape was still a WD, but the overall linewidth narrowed slightly down to 32 G (Figure 1), concomitant with decreasing central doublet splitting (Figure 1). At a higher [AA]/[PGHS-1] ratio (≥ 5), the EPR signature of the freeze-trapped radical intermediate exhibited significant changes, narrowing down from a WD to a 25 G singlet with no defined hyperfine structure (Figure 1). The narrow linewidth and lack of hyperfine structure are consistent with the NS1c alternative tyrosyl radical observed previously in the anaerobic reaction of PGHS-1 with EtOOH/AA [8,18]. Therefore the equilibrium between Y385· tyrosyl radical and AA-derived carbon-centered radical appeared to bias toward the former at low [AA]/[PGHS-1] ratio, on the other hand, at higher [AA]/[PGHS-1], with an apparent threshold of 5, radical either migrated onto a surrogate tyrosine or still resided on Y385 but adopting a different conformation, probably a ring rotamer with a more relaxed conformation due to breaking the hydrogen bond between Y385· and Y348 [19]. Results of this experiment clearly indicate the modulation of [AA] on the freeze-trapped radical intermediates; on the other hand, they also show that similar radical intermediate(s) were trapped regardless whether exogenous hydroperoxide was included in the reaction system or not.

Figure 1. EPR of the radical intermediates freeze-trapped in the PGHS-1 reactions with different equivalents of AA.

Anaerobic PGHS-1 (17.5 μM) was reacted with varied equivalents of AA (as marked) for 10 s at 281 K before being freeze-trapped in Dry Ice/Ethanol. Low level of O2, 0.2 eq., was included in the reaction systems and the small amount of PGG2 generated helped to propagate the PGHS-1 reactions. The two vertical lines provide the visual guide for linewidth of 34 G, which is the typical EPR linewidth of a WD1 tyrosyl radical.

3.2. Radical intermediate freeze-trapped in the reaction of PGHS-1 in the presence of varying levels of O2

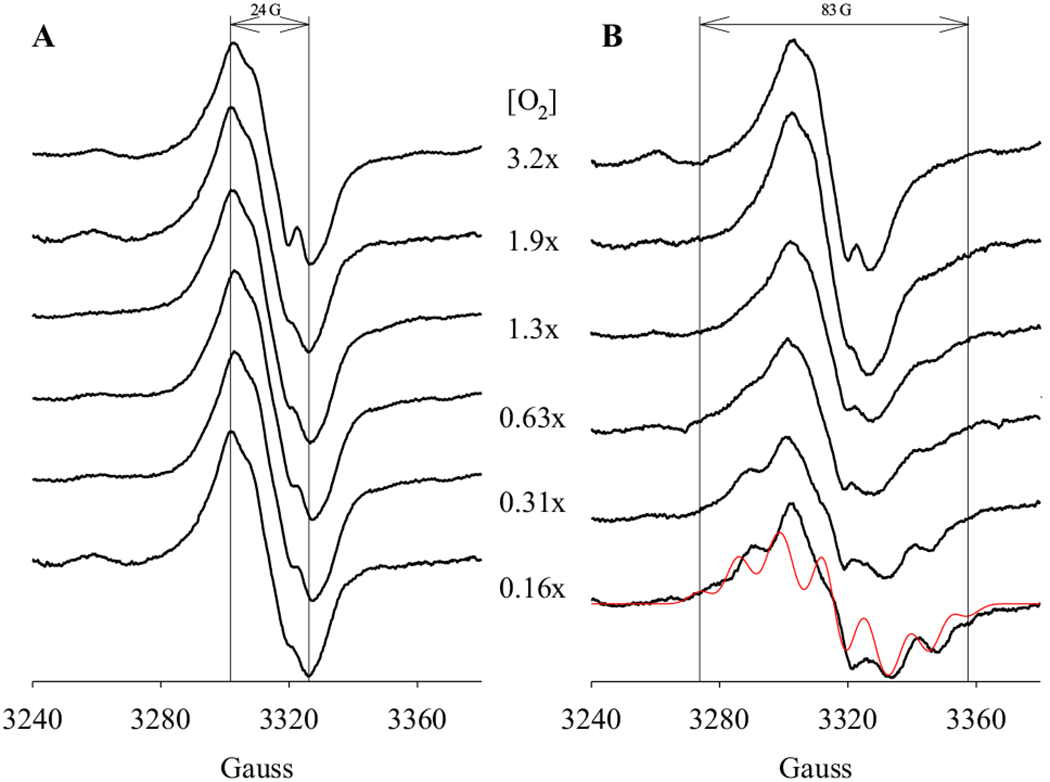

It was then examined whether different radical intermediates were freeze-trapped in the presence of various levels of O2, by reacting PGHS-1 with abundant (25 eq.) AA, in the presence of limited (0.16 to 3.2 eq.) amount of O2 (Figure 2A). At each level of O2, the EPR signatures of the freeze-trapped radical intermediate(s) were the same as the narrow singlet freeze-trapped at [AA]/[PGHS-1] = 5 described in 3.1, i.e., an NS1c (Figure 2A). These results show that at high [AA]/[PGHS-1] ratio, the radical located dominantly on a tyrosine residue (Y385 with certain ring rotamer or a surrogate tyrosine residue) and the same radical intermediate(s) was freeze-trapped independent of [O2] (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. EPR of radical intermediates freeze-trapped in PGHS-1 cyclooxygenase reactions in the presence of different levels of O2.

Anaerobic PGHS-1 (15 μM) was reacted with excess AA (25 eq.) in the presence of various levels of O2 (as marked) for 4 s at 281 K before being freeze-trapped in Dry Ice/Ethanol. The reaction system either contained no POX co-substrate (A) or 50 μM phenol (B). A simulation of AA pentadienyl radical is presented as a comparison (red). The parameters used in the simulation are [10,11]: g = 2.002; A(H11/H15), 10.4 G; A(H12/H14), 3.3 G; A(H13), 11.5 G; A(H10a/H10b), 16 G; A(H16a), 9.8 G; A(H16b), 3.9 G; linewidth, 6 G. The two vertical lines provide the visual guide for the EPR linewidths.

When the same reaction was conducted in the presence of a POX co-substrate, 50 μM phenol, EPR signatures of the freeze-trapped radical intermediate(s) exhibited a dependence on [O2] (Figure 2B). While NS1c tyrosyl radical was still observed at higher level of [O2] (> 1.3 eq.), at lower level of [O2], mixed EPR features of a NS1c tyrosyl radical and an AA pentadienyl radical were observed. The percentage of the freeze-trapped AA pentadienyl radical increased with decreasing [O2] from 0.6 to 0.2 eq. [PGHS-1] (Figure 2B). At the lowest level of O2 (0.2 eq.), significant amount of AA pentadienyl radical was freeze-trapped (Figure 2B). The EPR spectrum of the captured AA pentadienyl radical exhibited 83 G linewidth and seven-line hyperfine structure simulated properly by a g = 2.002 spin delocalized from C11 to C15 (Scheme 2), with nuclear hyperfine from C11 – C15 hydrogens and hyperconjugations from both C10 and C16 hydrogens as published previously [10,11,12]. The spin hyperconjugates with the two C10 hydrogen atoms equally, but significantly stronger with one C16 hydrogen atom than the other due to the gauche conformation at C16. The results of this experiment demonstrate that the POX co-substrates modulate the equilibrium between AA pentadienyl radical and NS1c tyrosyl radical in the anaerobic PGHS-1 reaction with AA.

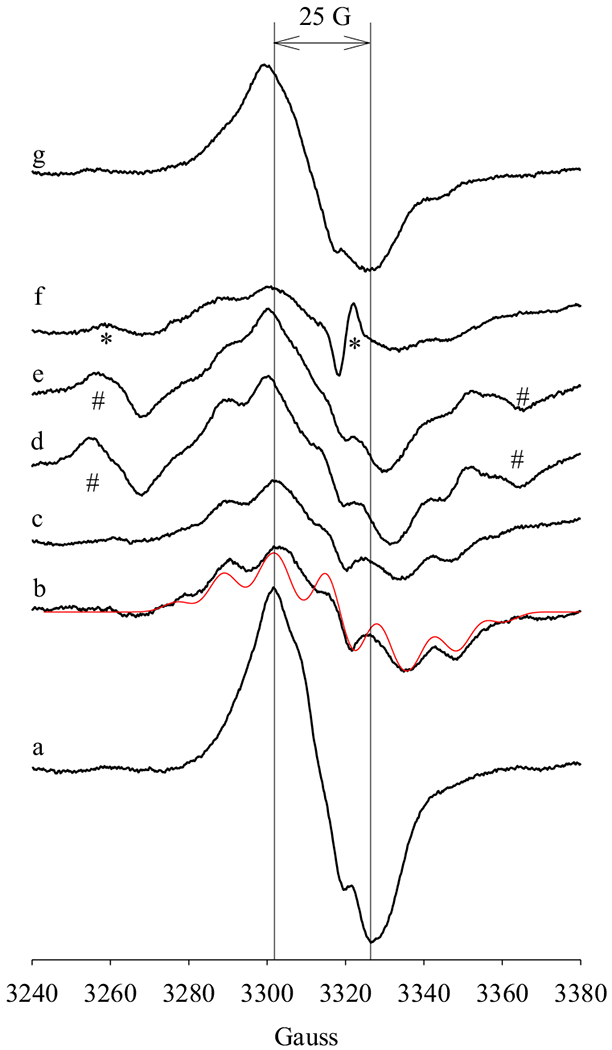

3.3. Radical intermediates freeze-trapped in PGHS-1 reaction in the presence of various POX co-substrates

Different POX co-substrates were next tested to examine whether a correlation exists between the efficiency of POX co-substrate(s) and the radical intermediates freeze-trapped in the anaerobic reaction of PGHS-1 with AA as in 3.2. For a panel of tested POX co-substrates [20], EPR features of the radical intermediates freeze-trapped in the anaerobic COX reaction exhibited a clear dependence on the type of POX co-substrates (Figure 3). As observed above (Figure 2A), in the absence of peroxidase co-substrate, only an NS1c tyrosyl radical was freeze-trapped (Figure 3a) and inclusion of exogenous POX co-substrates led to the observation of EPR features of an AA pentadienyl radical (Figure 3b–f). However, the percentage of freeze-trapped AA pentadienyl radical depended on the type of POX co-substrate. In the presence of hydroquinone or guaiacol, significant amount of AA pentadienyl radical was freeze-trapped (Fig. 3b & c) while the EPR signatures due to AA pentadienyl radical became less pronounced in the COX reactions with phenol, uric acid or ascorbate (Figure 3d–f). In the presence of tryptophan, EPR signatures of AA pentadienyl radical were only slightly observable (Figure 3g). The amount of freeze-trapped AA pentadienyl radical intermediate decreased in the following sequence: hydroquinone > guaiacol > phenol ≈ uric acid ≥ ascorbate > tryptophan. Such a sequence approximately matches the measured efficiency of these POX co-substrates in reducing high valence oxyferryl heme back to resting ferric heme (Table S2) [20], indicating more AA pentadienyl radical was trapped in the presence of POX more efficient co-substrates.

Figure 3. Effects of POX co-substrates on the radical dynamics in PGHS-1 reactions with AA.

Anaerobic PGHS-1 (15 μM) was reacted with excess AA (25 eq.) in the presence of O2 (0.4 eq.) for 4 s at 281 K before being freeze-trapped. The reaction systems contained 50 μM POX co-substrates: (a) no co-substrate; (b) hydroquinone; (c) guaiacol; (d) phenol; (e) uric acid; (f) ascorbate; (g) tryptophan. The two vertical lines provide the visual guide for linewidth of 25 G, which is the typical linewidth of NS1c. Red line: simulated EPR spectrum of AA pentadienyl radical with the same parameters as in Fig. 2. “*” and “#”: EPR signals from unidentified source(s), while “*” has g values of 2.04 and 2.00, which may belong to an unidentified peroxyl radical [31,32,33,34].

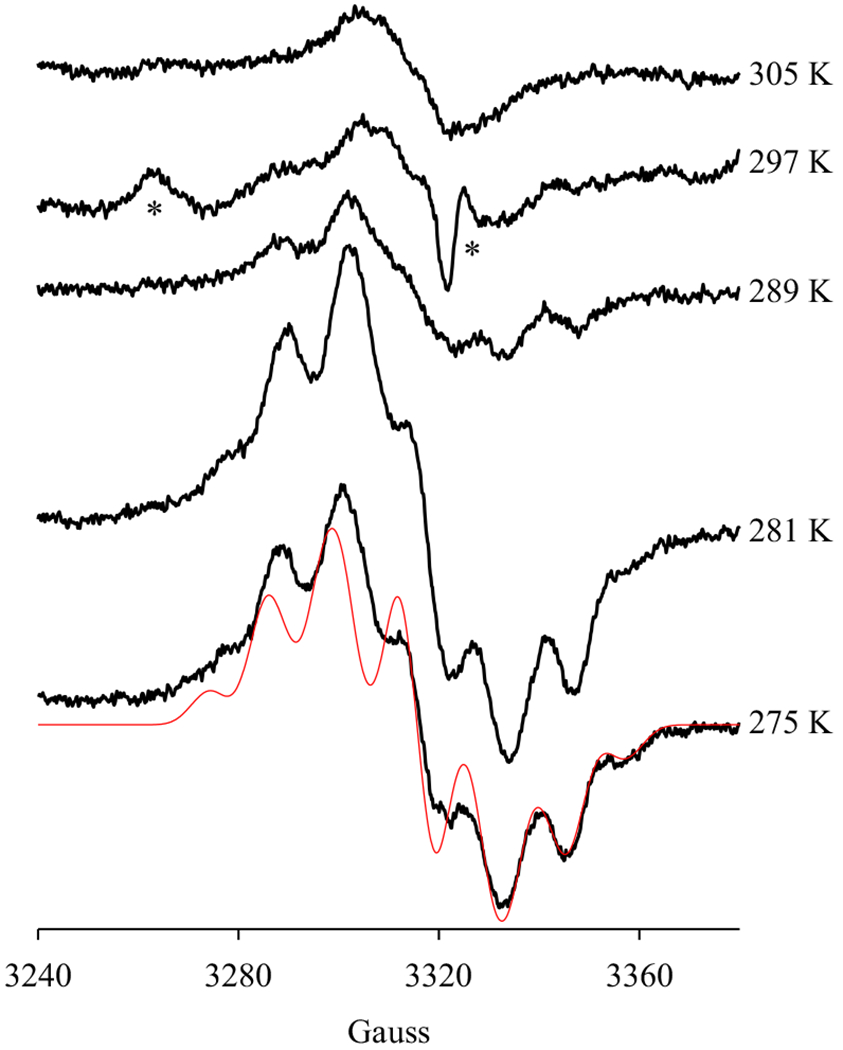

3.4. Temperature dependence of radical intermediates freeze-trapped in PGHS-1 reactions

In the previous study, a mixture of a pentadienyl radical and a narrow singlet was observed when anaerobic PGHS-1 pre-incubated with 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15-d8-arachidonic acid (d8-AA) was reacted with EtOOH from 263 K to 278 K, however, at 295 K, only NS1c tyrosyl radical was freeze-trapped [15]. On the other hand, only the NS1c tyrosyl radical was freeze-trapped in the reaction of PGHS-1 with AA, independent of reaction temperatures from 263 K to 295 K [15]. The effect of temperature on the radical(s) freeze-trapped in anaerobic PGHS-1 reaction with AA was examined in the presence of exogenous POX co-substrate. In this experiment, in the presence of 50 μM phenol, the radical intermediate(s) freeze-trapped in the anaerobic reaction of PGHS-1 with AA at 275 K and 281 K exhibited majorly EPR signatures of an AA pentadienyl radical (Figure 4). When the reaction temperature was increased to 289 K and 297 K, significantly less radical intermediate(s) was freeze-trapped, as indicated by the decreased intensity of the EPR signals (Figure 4). Nonetheless, the EPR signatures of AA pentadienyl radical were still clearly visible although together with a more significant background narrow singlet (Figure 4). At 305 K, only a narrow singlet with the line-shape typical of NS1c was observable (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Temperature dependence of radical intermediates freeze-trapped in PGHS-1 reactions with AA.

Anaerobic PGHS-1 (13.6 μM) was reacted with excess AA (5 eq.) for 10 s at different temperatures (as marked), in the presence of 1 eq. O2 and 50 μM phenol, before being freeze-trapped. Red line: simulated EPR spectrum of AA pentadienyl radical with the same parameters as in Fig. 2. “*”: EPR signals which may belong to an unidentified peroxyl radical [31,32,33,34], with g values of 2.04 and 2.00, as in Fig. 3.

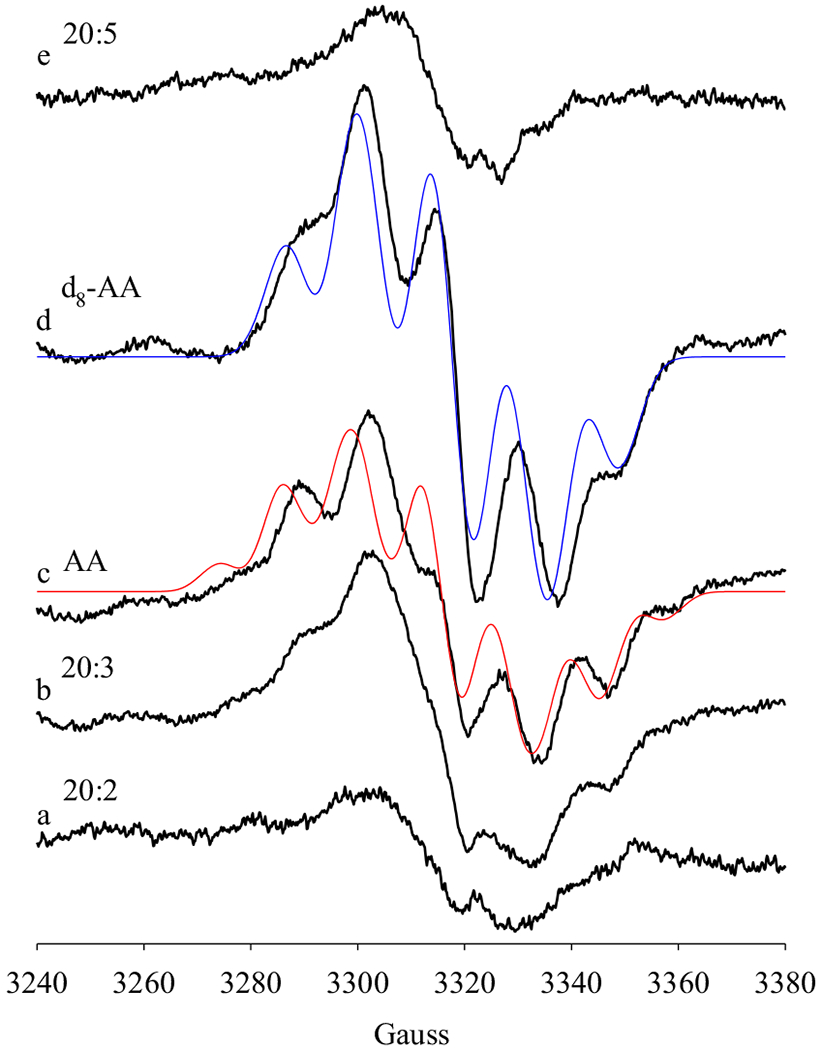

3.5. EPR of the Freeze-Trapped Radical Intermediates in PGHS-1 Reactions with Different Fatty Acid Substrates

PGHS catalyzes oxygenation of a variety of fatty acid substrates, presumably following the similar radical mechanism with AA substrate, starting with hydrogen abstraction by Y385· from a methlyene group between a pair of unconjugated double bonds. In the presence of POX co-substrate, 50 μM phenol, different radical species were freeze-trapped by reacting PGHS-1 with 20-carbon straight chain fatty acid substrates with different numbers of double bond (Figure 5). As observed in 3.2 – 3.4 (Figures 2–4), significant amount of AA pentadienyl radical was freeze-trapped in the anaerobic reaction of PGHS-1 with AA in the presence of 50 μM phenol (Figure 5c). The d8-AA pentadienyl radical was also freeze-trapped in significant amount when PGHS-1 was reacted with d8-AA (Figure 5d). The EPR spectrum of d8-AA pentadienyl radical was well fit using parameters published before [10,11], taking into account the deuterium labels on C11, C12, C14 and C15. When 8, 11, 14-eicosatrienoic acid (20:3, dihomo-γ-linolenic acid, DHLA) was the substrate, EPR features similar to a pentadienyl radical intermediate was still observable, although with a narrow NS1c radical of significant intensity (Figure 5b). In the anaerobic reactions of PGHS-1 with 11, 14-eicosadienoic acid (20:2) or 5, 8, 11, 14, 17-eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5 or eicosapentaenoic acid, EPA), only NS1c EPR signals were observed (Figure 5a & e). Moreover, significantly lower EPR intensities indicated that much lower amounts of radical intermediate(s) were captured in the PGHS-1 reactions with 20:2 or 20:5 (Figure 5a & e).

Figure 5. EPR of radical intermediates freeze-trapped in PGHS-1 reactions with different fatty acid substrates.

Anaerobic PGHS-1 (14 μM) was reacted with excess fatty acid substrates (5 eq.) in the presence of 1 eq. O2 for 10 s at 281 K before freeze-trapping. The reaction systems contained 50 μM phenol and different fatty acid substrates: (a) 11, 14-eicosadienoic acid (20:2); (b) 8, 11, 14-eicosatrienoic acid (20:3); (c) arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4); (d) 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15-d8-arachidonic acid (d8-AA); (e) 5, 8, 11, 14, 17-eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5). Red line: simulated EPR spectrum of AA pentadienyl radical with the same parameters as in Fig. 2. Blue line: simulated EPR spectrum of d8-AA pentadienyl radical with the parameters [12]: g = 2.002; A(D11/D15), 1.2 G; A(D12/D14), 0.4 G; A(H13), 11.5 G; A(H10a/H10b), 16 G; A(H16a), 9.8 G; A(H16b), 3.9 G; linewidth, 8 G

4. DISCUSSIONS

In this study, three types of radical intermediates were freeze-trapped in the anaerobic reactions of PGHS-1 with AA, including WD1 and NS1c tyrosyl radicals and AA pentadienyl radical. WD1 tyrosyl radical is located on Y385 and H-bonded to Y348 [14], on the other hand, the identity of the NS1c tyrosyl radical still remains unclear. However, the fact that it is in equilibrium with AA pentadienyl radical [15] indicates that Y348 and Y385 are the two possible locations for the NS1c tyrosyl radical since other tyrosine residues, such as Y504, are significantly further away from arachidonyl radical [21] and unlikely for radical migration (Figure S1A). Moreover, previous study on Y348F/Y504F PGHS-2 double mutant [19] suggests that the location of NS1c tyrosyl radical in PGHS-1 is likely on Y385 but with a different conformation from that of Y385· WD1 radical. In the reaction of Y348F/Y504F PGHS-2 with EtOOH, a time-dependent conversion from WD2 tyrosyl radical to a narrow singlet EPR similar to NS1c is observed, due to the disruption of the Y348→385 H-bond. Compared to wild type PGHS-2, Y385· radical in Y348F/Y504F PGHS-2 has greater conformational flexibility and greater rotational freedom in the COX active site [19]. EPR of the narrow singlet tyrosyl radical can be simulated with hyperfine splitting typical of a relaxed ring rotamer, with different dihedral angles between C1 p orbital and the two Cβ-H bonds from those in Y385· WD2 radical [19]. The WD2 to NS1c conversion indicates that the relaxed conformation is favored in the absence of the Y348→385 H-bond and this H-bond is not critical for COX catalysis since Y348F/Y504F PGHS-2 is fully functional [19]. On the other hand, slower formation of Y385· WD2 in Y348F/Y504F PGHS-2 and lower activity of the mutant compared to those of wild type PGHS-2 indicate that the Y348→385 H-bond does help the generation of Y385· WD2 radical [19]. The Y348→385 H-bond therefore tends to break after the formation of Y385· WD radical, leading to EPR lineshape conversion to an NS; in wild type PGHS-1 and −2, such a conversion is also observable albeit slower, exhibiting as a WD → WS change. WS tyrosyl radical is considered as the mixture of WD and an NS tyrosyl radical.

Although it is still unclear whether the disruption of Y348→385 H-bond after the generation of arachidonyl radical, leading to the NS1c tyrosyl radical, plays a role in COX catalysis, a novel functional role for Y385· NS1c radical in COX catalysis may be brought up. In COX reactions, the disruption of Y348→385 H-bond after the generation of arachidonyl radical is likely due to that later radical intermediates, particularly PGG2· radical, interact with COX active site very differently from AA for their different molecular shapes (Scheme 3). The relaxed conformation of Y385 may be optimal for the hydrogen transfer from Y385 to PGG2· radical to produce PGG2 and regenerate Y385· radical, which still adopts the relaxed conformation with the NS1c EPR lineshape (Scheme 3). Release of PGG2 and rebinding of AA resume the Y348→385 H-bond and the strained Y385 conformation specific for Y385· WD radical, custom for H-abstraction of the next AA molecule (Scheme 3). In PGHS-1, NS1c tyrosyl radical is only captured in the reactions of AA-bound PGHS-1 [10], in line with its possible role in hydrogen transfer to PGG2· radical in the last step of COX cycle (Scheme 3). Previous studies show that Y385· WD1 radical was captured when the NS1c tyrosyl radical was thawed and mixed with air before re-freezing [10,15], again in line with the suggested kinetic competence of the NS1c tyrosyl radical.

Scheme 3. Hypothetical location and function of Y385 NS1c tyrosyl radical.

In AA-bound Intermediate II, Y385· is H-bonded to Y348 (red dashed line) and exhibits a wide doublet EPR lineshape (WD1 radical). Y385· abstracts hydrogen from AA C13 atom (blue arrow) to generate arachidonyl carbon-centered radical. The arachidonyl radical is then converted to PGG2· radical through a series of COX reactions including insertion of two oxygen molecules, ring formations and radical shifts (horizontal black arrow). After generation of the arachidonyl radical, the H-bond between Y348 and Y385 is disrupted and Y385 adopts a new conformation ready for hydrogen transfer back from Y385 to C15-OO· of PGG2· radical (blue arrow) to generate PGG2 and regenerate Y385· radical. After the release of PGG2 and binding of the next AA molecule (tilted black arrows), H-bond between Y348 and Y385· radical is re-established. The AA-bound PGHS-1 structure is based on crystal structure 1DIY (PDB code) for AA-bound PGHS-1 with Co protoporphyrin IV. The different conformers of Y385 and Y348 in the other two structures are arbitrarily plotted and the chemical structure of PGG2 is based on the calculated structure 1DD0 (PDB code). All the structures are plotted using PyMOL. Green: carbon; red: oxygen; blue: nitrogen and brown ball: cobalt atom. (The color version of the figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

In aerobic COX reactions, oxygen provides strong driving force after hydrogen transfer from AA to Y385· WD1 radical, which is the rate-limiting step as demonstrated by deuterium kinetic isotope effect (KIE) study [16] and only Y385· WD1 radical is captured. On the other hand, in anaerobic reaction of PGHS-1 Intermediate II with AA, lacking the strong driving forces of oxygen, the following two equilibriums are established [10,15],

| (1) |

| (2) |

where (1) is the hydrogen abstraction from AA by Y385· WD1 radical and reaction (2) represents the equilibrium between AA pentadienyl radical and Y385 with a relaxed conformation, Y385*, due to disruption of the Y348→385 H-bond [10,15]. The co-existence of equilibriums (1) and (2) highlights the spin dynamics shifting between tyrosine residue(s) and AA. Previous experimental data show that the equilibriums are largely biased towards Y385*· radical, resulting in the freeze-trapping of NS1c tyrosyl radical in most cases [10]. This study demonstrates that this dynamics of tyrosyl/AA radical intermediates is affected by multiple factors.

It is not clear why the types of captured tyrosyl radicals is influenced by the [AA]/[PGHS-1] ratio (Figure 1). Perceivably at low [AA]/[PGHS-1] ratio, equilibrium (1) biases towards Y385· and therefore the freeze-trapping of Y385· WD1 radical (Figure 1). On other hand, at high [AA]/[PGHS-1] ratio (Figures 1 & 2A), equilibrium (1) is pushed towards the side of Y385 and AA·, and the accumulation of the latter favors the forward reaction of (2), leading to the freeze-trapping of the Y385*·’ NS1c radical (Figures 1 & 2A).

In the presence of efficient POX co-substrate, significant amount of AA pentadienyl radical was freeze-trapped during the anaerobic PGHS-1 reaction with AA (Figures 2B & 3). The correlation between the efficiency of POX co-substrates [20] and the amount of AA pentadienyl radical freeze-trapped underscores the modulating effect of the oxidation state of heme on the equilibrium (2) between arachidonyl radical and Y385*· NS1c radical in PGHS-1. In the absence of exogenous POX co-substrate, heme stayed longer in high oxidation state as oxyferryl heme {Fe(IV)=O}, and the freeze-trapping of only NS1c tyrosyl radical intermediate (Figure 2A) indicates that heme in high oxidation state favors the forward reaction of (2). On the other hand, in the presence of exogenous efficient POX co-substrate, heme was promptly reduced back to its ferric state and significant amount of AA pentadienyl radical was freeze-trapped, indicating that low oxidation state heme favors the reverse reaction of (2). The anaerobic reaction of PGHS-1 with POX co-substrate, together with the coupled equilibrium between tyrosyl radical and arachidonyl radical, can be expressed in the following reaction and summarized in Scheme 4,

| (3) |

It is plausible that the oxyferryl heme {Fe(IV)=O} is more oxidizing than ferric heme and (Em(Fe(IV)/Fe(III) ≥ 1V and Em(Fe(III)/Fe(II)) ≈ −100 mV) [22,23,24] thus has more driving to maintain the tyrosyl radical level than the ferric heme. Nonetheless, this correlation between the heme oxidation state and the equilibrium between COX radical intermediates shows the dynamic interplay of the heme oxidation state and COX activities in PGHS-1. According to the branched-chain mechanic model, POX and COX activities of PGHS diverge from Intermediate II, {Fe(IV)=O}(Y385·), and cycle independently (Scheme 1). This study provides evidence showing that the COX reactions are not completely independent of the oxidation state of the heme. Although the effect of POX co-substrates on the dynamics of COX radical intermediates becomes significant only under anaerobic conditions, in aerobic COX reactions, POX co-substrate, nonetheless, is in favor of arachidonyl radical and helpful for the process of COX catalysis. Redox cycling of heme back to its ferric form after generation of Intermediate II therefore facilitates COX catalysis.

NS1c tyrosyl radical has been freeze-trapped only in PGHS-1, not in PGHS-2 under anaerobic experimental conditions [10]. The difference between the two PGHS isoforms has been interpreted based on the relatively spacious AA binding site in PGHS-2 which is proposed to be more accommodative for AA pentadienyl radical [10]. On the other hand, data from this study provides another possible interpretation for the difference between PGHS-1 and −2 given that disruption of the Y348→385 H-bond leading to a relaxed conformation of Y385 in both isoforms. Exogenous peroxidase co-substrate(s), such as 50 – 100 μM phenol, is always included in PGHS-2 purifications to prevent quick activity loss [6], and the purification of PGHS-1 usually does not include exogenous POX co-substrate since PGHS-1 appears to contain significantly more endogenous co-substrate to help maintaining its activity [25]. The exogenous POX co-substrate(s) in the preparations of PGHS-2 likely favor AA pentadienyl radical in equilibrium (2) as in PGHS-1, leading to capturing more AA pentadienyl radical in PGHS-2.

Another interesting observation is that the dynamics of radical intermediate is temperature-dependent, significant amount of AA pentadienyl radical was only freeze-trapped at low temperature while at high temperature, only NS1c tyrosyl radical was freeze-trapped, even in the presence of exogenous POX co-substrate (Figure 4). One of the interpretations for this temperature-dependence suggests that the forward reaction of (2) is endothermal and favored at higher temperature. Similar temperature dependence was observed in the anaerobic PGHS-1 reaction with d8-AA/EtOOH, where an Δ(ΔG) of 0.23 kcal/mol was estimated based on the different equilibrium constants at different temperatures [15]. Another interpretation for the observed temperature-dependence may be due to looser interplay between the heme oxidation state and COX activities at higher temperature. The decaying EPR intensities with increasing temperature may be due to increasing quenching of radical(s) at higher temperature. This phenomenon was not observed in the previous studies of the anaerobic PGHS-1 reaction with AA/EtOOH or d8-AA/EtOOH [15], suggesting that POX co-substrates is capable of quenching tyrosyl and AA radicals at elevated temperature.

In addition to AA, PGHS is capable of using other polyunsaturated fatty acids as substrates to generate different products. However, the catalytic reactions are all believed to start from hydrogen abstraction by Y385· at C13, a bis-allylic position. In the absence of POX co-substrate, only NS1c radical intermediates were freeze-trapped in the anaerobic reaction between PGHS-1 and fatty acid substrates 20:2, 20:3 and 20:5 (data not shown). Therefore the Y348→385 H-bond is also disrupted after hydrogen transfer from fatty acid substrate(s) to Y385· WD radical, and reaction (2) biases greatly towards the Y385*· NS1c radical. Moreover, that NS1c was captured in PGHS-1 reactions with different fatty acid substrates is in line with its proposed role in COX catalysis. In the presence of exogenous POX co-substrate, significant amount of 20:3 pentadienyl radical was freeze-trapped, indicating the oxidation state of heme also affect the radical dynamics between 20:3 radical and tryosyl radicals. The similarity between AA and 20:3 is likely due to the similar binding of 20:3 at COX site compared to that of AA [21,26]. The crystal structure shows that 20:3 binds to COX site in the same overall L-shaped conformation as AA and its C1 carboxylate and C11 through C20 are in the same positions as AA [26] (Figure S1B). The dynamic interplay between the heme oxidation state and COX activity diminishes when 20:2 or 20:5 is the substrate, likely due to very different binding conformations of these two fatty acids in COX active site from those of AA and 20:3 [26,27]. The crystal structure shows that although 20:5 binds in the COX site with orientations similar to those with AA and 20:3, the presence of an additional double bond (C17=C18) in 20:5 causes it to bind in a “strained” conformation with misalignment of C13 with Y385 [27] (Figure S1C). Such a “strained” conformation of 20:5 likely favors disruption of the Y348→385 H-bond and thus the relaxed conformation of Y385. When PGHS-1 was anaerobically reacted with d8-AA, d4-pentadienyl radical was freeze-trapped (Figure 5). However, this d4-pentadienyl radical was successfully freeze-trapped in previous studies in the absence of POX co-substrate [10,12], although the amount of the freeze-trapped d4-pentadienyl radical is less compared to that observed in this study in the presence of exogenous POX co-substrate (Figure 5). The dynamic interplay between the heme oxidation state and COX activity appears to be weaker when d8-AA is the substrate.

This study demonstrates that the radical dynamics in the anaerobic COX reactions is shifted by many factors. In fact, the kinetics of aerobic COX reactions is also dependent upon many factors, exhibiting varying kinetic features under different experimental conditions. As shown in our previous study, hydrogen abstraction from AA by Y385· is the rate-limiting step in COX catalysis based on both steady-state and single-turnover deuterium KIE [16]. However, O16/ O18 KIE data on PGHS-2 with AA and linolenic acid (LA) indicate additional rate-limiting step(s) occurs in the subsequent COX reactions and POX co-substrate phenol may play an important role in shifting the rate-limiting step(s) [28,29,30]. The discrepancy observed in COX kinetics based on these KIE studies may be due to very subtle experimental differences as we observed in this study.

CONCLUSION

The dynamics between PGHS-1 tyrosyl radical and substrate radical is affected by multiple factors including the substrate-to-enzyme ratio, oxygen concentration, reaction temperature, structures of fatty acid substrates and peroxidase co-substrate. The latter indicates a dynamic interplay between the peroxidase and cyclooxygenase activities of PGHS-1.

Supplementary Material

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This work is supported by NIH grants HL095820 and NS094535 (A.L. Tsai).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AA

arachidonic acid

- d8-AA

5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15-d8-arachidonic acid

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- PGG2

prostaglandin G2

- KIE

kinetic isotope effect

- PGH2

prostaglandin H2

- PGHS

prostaglandin H synthase

- PGHS-1

PGHS, isozyme type 1

- PGHS-2

PGHS, isozyme type 2

- COX

cyclooxygenase activity of PGHS

- POX

peroxidase activity of PGHS

- 20:2

11, 14-eicosadienoic acid

- 20:3

8, 11, 14-eicosatrienoic acid

- 20:5

5, 8, 11, 14, 17-eicosapentaenoic acid

Biography

Gang Wu

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available on the publishers web site along with the published article.

REFERENCES

- [1].van der Donk WA; Tsai AL; Kulmacz RJ, The cyclooxygenase reaction mechanism. Biochemistry, 2002, 41, 15451–15458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dietz R; Nastainczyk W; Ruf HH, Higher oxidation states of prostaglandin H synthase. Rapid electronic spectroscopy detected two spectral intermediates during the peroxidase reaction with prostaglandin G2. Eur. J. Biochem, 1988, 171, 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Karthein R; Dietz R; Nastainczyk W; Ruf HH, Higher oxidation states of prostaglandin H synthase. EPR study of a transient tyrosyl radical in the enzyme during the peroxidase reaction. Eur. J. Biochem, 1988, 171, 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hamberg M; Samuelsson B, On the mechanism of the biosynthesis of prostaglandins E-1 and F-1-alpha. J. Biol. Chem, 1967, 242, 5336–5343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hamberg M; Samuelsson B, On the specificity of the oxygenation of unsaturated fatty acids catalyzed by soybean lipoxidase. J. Biol. Chem, 1967, 242, 5329–5335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tsai AL; Wu G; Palmer G; Bambai B; Koehn JA; Marshall PJ; Kulmacz RJ, Rapid kinetics of tyrosyl radical formation and heme redox state changes in prostaglandin H synthase-1 and −2. J. Biol. Chem, 1999, 274, 21695–21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tsai AL; Kulmacz RJ, Tyrosyl radicals in prostaglandin H synthase-1 and-2. Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediat, 2000, 62, 231–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tsai AL; Kulmacz RJ, Prostaglandin H synthase: resolved and unresolved mechanistic issues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys, 2010, 493, 103–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kulmacz RJ; Palmer G; Tsai AL, Prostaglandin H synthase: perturbation of the tyrosyl radical as a probe of anticyclooxygenase agents. Mol. Pharmacol, 1991, 40, 833–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tsai AL; Wu G; Rogge CE; Lu JM; Peng S; van der Donk WA; Palmer G; Gerfen GJ; Kulmacz RJ, Structural comparisons of arachidonic acid-induced radicals formed by prostaglandin H synthase-1 and -2. J. Inorg. Biochem, 2011, 105, 366–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Peng S; Okeley NM; Tsai AL; Wu G; Kulmacz RJ; van der Donk WA, Synthesis of isotopically labeled arachidonic acids to probe the reaction mechanism of prostaglandin H synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2002, 124, 10785–10796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tsai AL; Palmer G; Xiao G; Swinney DC; Kulmacz RJ, Structural characterization of arachidonyl radicals formed by prostaglandin H synthase-2 and prostaglandin H synthase-1 reconstituted with mangano protoporphyrin IX. J. Biol. Chem, 1998, 273, 3888–3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Peng S; Okeley NM; Tsai AL; Wu G; Kulmacz RJ; van der Donk WA, Structural characterization of a pentadienyl radical intermediate formed during catalysis by prostaglandin H synthase-2. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2001, 123, 3609–3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wilson JC; Wu G; Tsai AL; Gerfen GJ, Determination of the structural environment of the tyrosyl radical in prostaglandin H2 synthase-1: a high frequency ENDOR/EPR study. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2005, 127, 1618–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lu JM; Rogge CE; Wu G; Kulmacz RJ; van der Donk WA; Tsai AL, Cyclooxygenase reaction mechanism of PGHS--evidence for a reversible transition between a pentadienyl radical and a new tyrosyl radical by nitric oxide trapping. J. Inorg. Biochem, 2011, 105, 356–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wu G; Lu JM; van der Donk WA; Kulmacz RJ; Tsai AL, Cyclooxygenase reaction mechanism of prostaglandin H synthase from deuterium kinetic isotope effects. J. Inorg. Biochem, 2011, 105, 382–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wu G; Wei C; Kulmacz RJ; Osawa Y; Tsai AL, A mechanistic study of self-inactivation of the peroxidase activity in prostaglandin H synthase-1. J. Biol. Chem, 1999, 274, 9231–9237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tsai AL; Kulmacz RJ; Palmer G, Spectroscopic evidence for reaction of prostaglandin H synthase-1 tyrosyl radical with arachidonic acid. J. Biol. Chem, 1995, 270, 10503–10508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rogge CE; Ho B; Liu W; Kulmacz RJ; Tsai AL, Role of Tyr348 in Tyr385 radical dynamics and cyclooxygenase inhibitor interactions in prostaglandin H synthase-2. Biochemistry, 200645, 523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Markey CM; Alward A; Weller PE; Marnett LJ, Quantitative studies of hydroperoxide reduction by prostaglandin H synthase. Reducing substrate specificity and the relationship of peroxidase to cyclooxygenase activities. J. Biol. Chem, 1987, 262, 6266–6279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Malkowski MG; Ginell SL; Smith WL; Garavito RM, The productive conformation of arachidonic acid bound to prostaglandin synthase. Science, 2000, 289, 1933–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tsai AL; Kulmacz RJ; Wang JS; Wang Y; van Wart HE; Palmer G, Heme coordination of prostaglandin H synthase. J. Biol. Chem, 1993, 268, 8554–8563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Goodwin DC; Rowlinson SW; Marnett LJ, Substitution of tyrosine for the proximal histidine ligand to the heme of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2: implications for the mechanism of cyclooxygenase activation and catalysis. Biochemistry, 2000, 39, 5422–5432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lee WA; Calderwood TS; Bruice TC, Stabilization of higher-valent states of iron porphyrin by hydroxide and methoxide ligands: electrochemical generation of iron(IV)-oxo porphyrins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 1985, 82, 4301–4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tsai AL; Wu G; Kulmacz RJ, Stoichiometry of the interaction of prostaglandin H synthase with substrates. Biochemistry, 1997, 36, 13085–13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Thuresson ED; Malkowski MG; Lakkides KM; Rieke CJ; Mulichak AM; Ginell SL; Garavito RM; Smith WL, Mutational and X-ray crystallographic analysis of the interaction of dihomo-gamma -linolenic acid with prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases. J. Biol. Chem, 2001, 276, 10358–10365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Malkowski MG; Thuresson ED; Lakkides KM; Rieke CJ; Micielli R; Smith WL; Garavito RM, Structure of eicosapentaenoic and linoleic acids in the cyclooxygenase site of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-1. J. Biol. Chem, 2001, 276, 37547–37555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mukherjee A; Brinkley DW; Chang KM; Roth JP, Molecular oxygen dependent steps in fatty acid oxidation by cyclooxygenase-1. Biochemistry, 2007, 46, 3975–3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mukherjee A; Angeles-Boza AM; Huff GS; Roth JP, Catalytic mechanism of a heme and tyrosyl radical-containing fatty acid alpha-(di)oxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2011, 133, 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Liu Y; Roth JP, A Revised Mechanism for Human Cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem, 2016, 291, 948–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Svistunenko DA, Reaction of haem containing proteins and enzymes with hydroperoxides: the radical view. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2005, 1707, 127–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chamulitrat W; Mason RP, Lipid peroxyl radical intermediates in the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenase. Direct electron spin resonance investigations. J. Biol. Chem, 1989, 264, 20968–20973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chamulitrat W; Takahashi N; Mason RP, Peroxyl, alkoxyl, and carbon-centered radical formation from organic hydroperoxides by chloroperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem, 1989, 264, 7889–7899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nelson MJ; Cowling RA; Seitz SP, Structural characterization of alkyl and peroxyl radicals in solutions of purple lipoxygenase. Biochemistry, 1994, 33, 4966–4973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.