Abstract

Understanding changes in oral flora during pregnancy, its association to maternal health, and its implications to birth outcomes is essential. We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library in May 2020 (updated search in April and June 2021), and conducted a systematic review and meta-analyses to assess the followings: (1) oral microflora changes throughout pregnancy, (2) association between oral microorganisms during pregnancy and maternal oral/systemic conditions, and (3) implications of oral microorganisms during pregnancy on birth outcomes. From 3983 records, 78 studies were included for qualitative assessment, and 13 studies were included in meta-analysis. The oral microflora remains relatively stable during pregnancy; however, pregnancy was associated with distinct composition/abundance of oral microorganisms when compared to postpartum/non-pregnant status. Oral microflora during pregnancy appears to be influenced by oral and systemic conditions (e.g. gestational diabetes mellitus, pre-eclampsia, etc.). Prenatal dental care reduced the carriage of oral pathogens (e.g. Streptococcus mutans). The Porphyromonas gingivalis in subgingival plaque was more abundant in women with preterm birth. Given the results from meta-analyses were inconclusive since limited studies reported outcomes on the same measuring scale, more future studies are needed to elucidate the association between pregnancy oral microbiota and maternal oral/systemic health and birth outcomes.

Subject terms: Dental caries, Oral microbiology, Oral diseases

Introduction

Pregnancy is a unique physiological state, accompanied by temporary changes in women’s physical structure, hormone levels, metabolism and immune systems1,2. The changes during pregnancy are vital to maintaining the stable status of mother and fetus, however, some physiological, hormonal and dietary changes associated with pregnancy, in turn, alter the risk for oral diseases, such as periodontal disease and dental caries3. The delicate and complex changes during pregnancy also affect the microbial composition of various body sites of the expectant mothers4, including the oral cavity2. The oral cavity is colonized with a complex and diverse microbiome of over 700 commensals that have been identified in the Human Oral Microbiome Database (HOMD)5 and recently expanded HOMD (eHOMD), including bacterial and fungal species6. Given a balanced microbial flora helps to maintain stable oral and general health, alterations in the oral microbial community during pregnancy might impact maternal oral health7,8, birth outcomes9, and the infant’s oral health10. Therefore, understanding changes of oral flora during pregnancy, its association to maternal health, and its implications to birth outcomes is essential.

First, despite the speculated associations between oral flora and oral diseases during pregnancy, two critical questions that remain to be answered are (1) what changes in the oral microbiota occur during pregnancy; (2) whether the changes are associated with increased risk for oral diseases during pregnancy. Studies that evaluated the stability of the oral microbiome during pregnancy revealed that the composition and diversity of oral microbiome components remained stable without significant change11,12. However, on the contrary, some studies reported that pregnant women experienced a significant increase in Streptococcus mutans, a well-known culprit for dental caries13,14. In addition, researchers also reported an increased level of periodontal pathogens, e.g., Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromona gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia, among pregnant women15–17. Nevertheless, comprehensive evaluations of available evidence are needed to provide conclusive consensus.

Second, a clear understanding of the association between oral microorganisms and adverse birth outcomes conveys significant health implications. A systematic review from Daalderop et al., reported an association between periodontal disease and various adverse pregnancy outcomes18. Women who have periodontal diseases during pregnancy are at higher risk for delivering preterm and low birth-weight infants19–21. In terms of oral microorganisms, researchers reported a higher level of P. gingivalis among women with preterm deliveries22,23. A higher risk of preterm delivery was also observed among pregnant women with detection of periodontal anaerobes in subgingival plaque24. In contrast, Costa et al. reported that the risk of preterm birth is not correlated to an increased amount of periodontopathogenic bacteria25. Therefore, a thorough review of all available evidence on the topic of prenatal oral microorganisms and adverse birth outcomes is critical.

Furthermore, maternal oral health is closely associated with children’s oral health, including maternal relatedness and vertical transmission of oral pathogens from mothers to infants26. Thus, in theory, reducing maternal oral pathogens during pregnancy is paramount, since it could potentially reduce or delay the colonization of oral pathogens in the infant’s oral cavity. Interestingly, although some studies27,28 demonstrated that expectant mothers who received atraumatic dental restorative treatment during pregnancy resulted in significant reductions of S. mutans carriage, and pregnant women who received periodontal treatment (scaling and root planning) had a lowered periodontal pathogen level, a study from Jaramillo et al., failed to indicate decreased periodontal bacteria in pregnant women following periodontal treatment29.

Therefore, this study aims to comprehensively review the literature on oral microorganisms and pregnancy. We are focusing on analyzing the evidence on the following subcategories: (1) oral microbial community changes throughout pregnancy, including changes of key oral pathogens, the abundance, and diversity of the oral fungal and bacterial community; (2) association between oral microorganisms during pregnancy and maternal oral/systemic diseases; (3) implications of oral microorganisms during pregnancy on adverse birth outcomes.

Methods

This systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines30, the protocol was registered for in the PROSPERO (CRD42021246545) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

Search methods

Database searches were conducted in May 2020 and updated in April and June 2021 to identify published studies on changes in oral microbiome during pregnancy. A medical reference librarian (DAC) developed the search strategies and retrieved citations from the following databases: Medline via PubMed, Embase via embase.com, All databases (Web of Science Core Collection, BIOSIS Citation Index, Current Contents Connect, Data Citation Index, Derwent Innovation Index, KCI-Korean Journal Database, Medline, Russian Science Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index, and Zoological Record) via Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials via Cochrane Library. A combination of text words and controlled vocabulary terms were used (oral microbiota, oral health, bacterial diversity, pregnancy, periodontal pathogens, pregnancy complication). See “ESM Appendix” for detailed search methods used.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This systematic review included case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, retrospective and prospective cohort studies, randomized or non-randomized controlled trials that examined the changes of oral microorganisms in relation to pregnancy, oral diseases during pregnancy, adverse birth outcome and the effect of prenatal oral health care on oral microorganisms’ carriage. Two trained independent reviewers completed the article selection in accordance with the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the two reviewers or by the third reviewer.

Inclusion criteria

Types of participants: women during reproductive age (pregnant and non-pregnant women).

Types of intervention(s)/phenomena of interest: pregnancy.

Types of comparisons:

oral microbiota changes throughout pregnancy;

oral microbiota profiling between pregnancy and non-pregnancy phases;

oral microbiota changes following prenatal oral health care;

association between oral microorganisms during pregnancy and adverse birth outcome;

impact of systematic or oral health conditions on oral microbiota in pregnancy.

Types of outcomes: detection and carriage of oral microorganisms, oral microbiota diversity and composition.

Types of studies: case–control study; cross-sectional study; retrospective and prospective cohort study; randomized and non-randomized controlled trials.

Types of statistical data: detection and carriage [colony forming unit (CFU)] of individual microorganisms; Confidence Intervals (CI); p values.

Exclusion criteria

In vitro studies; animal studies; papers with abstract only; literature reviews; letters to the editor; editorials; patient handouts; case report or case series, and patents.

Data extraction

Descriptive data, including clinical and methodological factors such as country of origin, study design, clinical sample source, measurement interval, age of subjects, outcome measures, and results from statistical analysis were obtained.

Qualitative assessment and quantitative analysis

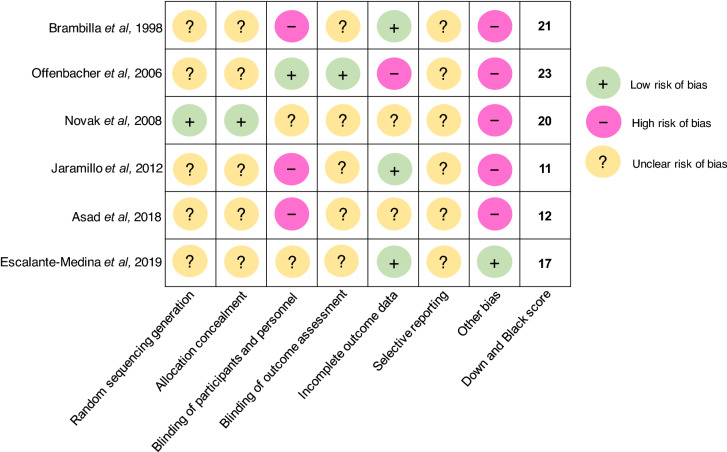

The quality of the selected articles was assessed depending on the types of studies. For randomized controlled trials, two methodological validities were used. (1) Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials31. Articles were scaled for the following bias categories: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias. (2) Adapted Downs and Black scoring that assesses the methodological quality of both randomized and non-randomized studies of health care interventions32. A total score of 26 represents the highest study quality. For cohort and cross-sectional studies, a quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies was used33. Additionally, GRADE34,35 was used to assess articles used clinical interventions during pregnancy.

For the articles selected for quantitative analysis, the OpenMeta[Analyst] was used for meta-analysis (http://cebm.brown.edu/openmeta/). The 95% CI and p values were estimated using an unconditional generalized linear mixed effects model with continuous random effects via DerSimonian–Laird method. Heterogeneity among the studies was evaluated using I2 statistics and tested using mean difference values. Forest plots were created to summarize the meta-analysis study results of mean difference of viable counts (converted to log value) of microorganisms.

Results

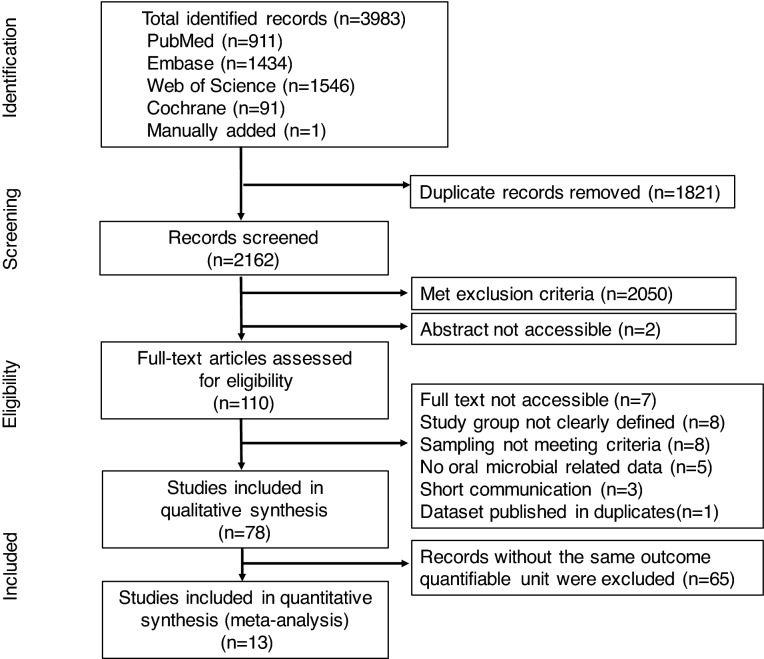

The literature analyses identified a total of 3983 records from database searches (3982) and manual additions (1). A total of 1821 duplicate references were removed. From the remaining 2162 records, 2050 were excluded after title and abstract screening. The remaining 110 studies proceeded to a full text review; 32 studies were eliminated based on the exclusion criteria and 78 articles were chosen for qualitative assessment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study identification. The 4-phase preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram was used to determine the number of studies identified, screened, eligible, and included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (http://www.prisma-statement.org).

Study characteristics

The characteristics of studies11–17,21–25,27–29,36–98 included in the qualitative review are summarized in Tables. A total of 78 studies are categorized into the following subgroups: 18 studies on oral microbial differences between pregnant and non-pregnant women in Table 114–17,36–49; 11 studies on oral microbial differences between pregnant stages in Table 211–13,50–57; 8 studies on oral microbial differences responding to prenatal dental treatment in Table 327–29,58–62; 16 studies on association between oral microorganisms during pregnancy and adverse birth outcome in Table 421–25,63–73; eight studies on impact of periodontal disease on oral microorganisms during pregnancy in Table 574–81; six studies on impact of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) on oral microorganisms during pregnancy in Table 682–87; 11 studies on impact of systemic health conditions on oral microorganisms during pregnancy in Table 788–98. Quality and risk of bias for randomized controlled trials was assessed and are shown in Fig. 2. Quality assessment for cohort and cross-sectional studies are included in the last column of all tables.

Table 1.

Oral microbial differences between pregnant and non-pregnant women.

| Author (year) | Country, study design | Groups (no. of subjects) | Sample source | Measurement interval | Microorganisms evaluated | Microbial detection methods | Study findings | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kornman and Loesche (1980)36 | USA, prospective cohort |

Pregnant (20) Non-pregnant (11) |

Subgingival plaque |

Pregnant group T1: < 13 weeks GA Follow-ups: monthly after until delivery Non-pregnant group Monthly visit for 4 consecutive months |

A. naeslundii, A. odontolyticus, A. viscosus, B. asaccharolyticus, P. intermedi), B. ochraceus, F. nucleatum, S. sanguis | Culturing |

The subgingival flora evolved to a composition that has more anaerobes as pregnancy progressed The anaerobe/aerobe ratio increased significantly at an early stage of pregnancy and remained high until the third trimester Only B. melaninogenicus ss. intermidius (currently P. intermedia) significantly increased during pregnancy compared between trimesters In the 2nd trimester, the anaerobe/aerobe ratio and the proportions of B. melaninogenicus ss. intermedius different significantly from the non-pregnant group |

Fair |

| Muramatsu and Takaesu (1994)37 | Japan, cross-sectional |

Pregnant (19) Non-pregnant (12) Postpartum (8) |

Supragingival plaque, saliva |

Pregnant group One time point during pregnancy |

P. intermedia, Black-pigmented anaerobic rods, Actinomyces streptococcus | Culturing |

Significant differences in proportions of Actinomyces were found between pregnant and non-pregnant group and between 2nd trimester pregnant and postpartum group No statistically significant changes in proportions of P. intermedia |

Fair |

| Yokoyama et al. (2008)38 | Japan, cross-sectional |

Pregnant (22) Non-pregnant (15) |

Unstimulated whole saliva |

Pregnant group 27.4 ± 5.1 weeks GA |

C. rectus, P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia | Real-time PCR |

Positive correlations between bacteria carriage and estradiol concentrations C. rectus (r = 0.443, p = 0.006) P. gingivalis (r = 0.468, p = 0.028) F. nucleatum (r = 0.452, p = 0.035) Positive correlations between C. rectus levels and sites of 4 mm-pocket depth (r = 0.568, p = 0.006) |

Fair |

| Gürsoy et al. (2009)16 | Finland, prospective cohort |

Pregnant (30) Non-pregnant (24) |

Subgingival plaque, saliva |

Pregnant group T1: 12–14 weeks GA T2: 25–27 weeks GA T3: 34–38 weeks GA T4: 4–6 weeks postpartum; T5: After lactation Non-pregnant group T1–T3 (once per subsequent month) |

P. intermedia, P. nigrescens (former Bacteroides intermedius) | 16s rDNA sequencing and culturing |

Carriage of subgingival P. intermedia doubled in the 2nd trimester, comparing to the 1st trimester; continued increasing till after the delivery (p < 0.05); and decreased to the lowest point after lactation Carriage of salivary P. intermedia remained stable during the pregnancy and decreased (p < 0.05) after lactation to the same level as the non-pregnant group P. nigrescens is likely associated with pregnancy gingivitis |

Fair |

| Carrillo-de-Albornoz et al. (2010)39 | Spain, prospective cohort |

Pregnant (48) Non-pregnant (28) |

Subgingival plaque |

Pregnant group T1: 12–14 weeks GA T2: 23–25 weeks GA T3: 33–36 weeks GA T4: 3 months postpartum Non-pregnant group 2 visits 6 months apart |

C. rectus, P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, T. forsythensis, P. micra | Culturing |

No significant changes in total bacterial counts in the pregnant group either during or after pregnancy Significant reduction in A. actinomycetemcomitans after delivery (p = 0.039) No statistically significant differences during pregnancy for any of the pathogens evaluated; however, significant changes from the third trimester to postpartum for all the pathogens Subjects who were positive for P. gingivalis had higher levels of gingival inflammation |

Fair |

| Basavaraju et al. (2012)40 | India, prospective cohort |

Pregnant (15) Non-pregnant (15) |

Subgingival plaque |

Pregnant group T1: during pregnancy T2: 3 weeks postpartum |

Veillonella, T. forsythia, P. intermedia, P. gingivalis, Peptoscreptococcus, F. nucleatum, Propionebactierum, Mobiluncus, Candida spp. | Culturing |

The organisms which were most commonly detected in both the groups were: Vielonella, T. forsythia, P. intermedia, P. gingivalis, Peptosreptococcus and F. nucleatum P. gingivalis was present in 5 patients out of 15 in the pregnant-group as compared to 1 in the non pregnant group and the count was reduced to 3 during postpartum |

Poor |

| Machado et al. (2012)41 | Brazil, cross-sectional |

Pregnant (20) Non-pregnant (20) |

Subgingival plaque |

Pregnant group 14–24 weeks GA |

A. actinomycetemcomitans, T. forsythia, C. rectus, P. gingivalus, T. denticola, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens | Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

No significant difference in mean total bacterial count between pregnant and non-pregnant group No significant differences between groups in the numbers of all bactieral species evaluated |

Fair |

| Emmatty et al. (2013)17 | India, cross-sectional |

Pregnant (30, 10 in each trimester) Non-pregnant (10) |

Subgingival plaque |

Pregnant group One time point during pregnancy |

A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, F. nucleatum, P. micra | Culturing |

P. intermedia significantly increased in pregnant women who were in their second and third trimesters as compared with first trimester and non-pregnant women Proportions of the pathogens assessed did not show any significant difference among pregnant and non-pregnant women |

Fair |

| Borgo et al. (2014)15 | Brazil, prospective cohort |

Pregnant (9) Non-pregnant (9) |

Subgingival plaque |

Pregnant group T1: Second trimester (15–26 weeks GA) T2: Third trimester (30–36 weeks GA) |

A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, F. nucleatum | Real-time PCR | The detection of A. actinomycetemcomitans in pregnant women at 2nd and 3rd trimester was significant higher than that in the non-pregnant women (p < 0.05) | Fair |

| Fujiwara et al. (2017)42 | Japan, prospective cohort |

Pregnant (132) Non-pregnant (51) |

Subgingival plaque, saliva |

Pregnant group T1: 7–16 weeks GA T2: 17–28 weeks GA T3: 29–39 weeks GA |

Subgingival A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, F. nucleatum Saliva Above 4 + Streptococci, Staphylococci, Candida spp. |

Culturing and real-time PCR |

A significant difference in total cultivable microbial number between non-pregnant and each stage of pregnancy More total bacteria counts at early stage of pregnancy (T1), comparing to the non-pregnant group (p < 0.05) Significant higher prevalence of Candida spp. in the middle (T2) and late (T3) pregnancy, comparing to the non-pregnant group (p < 0.05) The number of periodontal species was significantly lower in late pregnancy (T3), comparing to the early (T1) and middle (T2) pregnancy (p < 0.05) The prevalence of P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans was significantly higher in the early (T1) and middle (T2) stage of pregnancy, comparing to the nonpregnant women (p < 0.05) |

Fair |

| Kamate et al. (2017)14 | India, prospective cohort |

Pregnant (50) Non-pregnant (50) |

Saliva |

Pregnant group T1: 6 weeks GA T2: 18 weeks GA T3: 30 weeks GA T4: 6 weeks postpartum |

S. mutans | Culturing | A significant increase in S. mutans during the 2nd and 3rd trimester and postpartum period of pregnancy compared to the non-pregnant group (p < 0.01) | Fair |

| Rio et al. (2017)43 | Portugal, prospective cohort |

Pregnant (30) Non-pregnant (30) |

Unstimulated saliva |

Pregnant group T1: 1st trimester T2: 3rd trimester |

Yeast | Culturing |

No difference in oral yeast detection within pregnancy stages and between pregnant and non-pregnant stages (p < 0.05) More oral yeast were found in the 3rd trimester than the 1st trimmest, but no difference comparing to the non-pregnant stage (p < 0.05) Saliva flow rate did not change in both groups |

Fair |

| Lin et al. (2018)44 | China, prospective cohort |

Pregnant (11) Non-pregnant (7) |

Supragingival plaque, saliva |

Pregnant group T1: 11–14 weeks GA T2: 20–25 weeks GA T3: 33–37 weeks GA T4: 6 weeks postpartum Non-pregnant group 4 visits (same intervals of the pregnant group) |

Quantity of OUT and microbiota diversity | 16s rDNA sequencing |

Significant higher bacterial diversity of the supragingival microbiota in third trimester compared to the non-pregnant group Neisseriaceae and Porphyromonadaceae and Spirochaetaceae were significantly enriched in pregnant group |

Fair |

| Xiao et al. (2019)45 | USA, cross-sectional |

Low SES pregnant (48) Low SES Non-pregnant (34) |

Whole non-stimulated saliva, supragingival plaque, mucosal swabs |

Pregnant group 3rd trimester (> 28 weeks GA) |

C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. dubliniensis, S. mutans | Culturing and Colony PCR |

Salivary S. mutans carriage was higher in pregnant than non-pregnant women (p < 0.05) No difference between pregnant and non-pregnant salivary C. albicans carriage (p > 0.05) Tonsil (57%) was the most prevalent site for C. albicans detection among pregnant women Untreated decayed teeth is associated with higher carriage of salivary S. mutans and C. albicans detection in both pregnant and non-pregnant groups (p < 0.05) |

Fair |

| Aikulola et al. (2020)46 | Nigeria, cross-sectional |

Pregnant (26) Non-pregnant (32) |

Oral swab |

Pregnant group 20–28 weeks GA |

S. aureus, N. catarrhalis, K. pneumonia, E. coli, P. melaninogenicus, P. propionicum, V. pervula, S. viridans, Coagulase negative Staphylococcus | Culturing | E. coli was the most common species in non-pregnant group while N. catarrhalis was the most common in the pregnant group | Poor |

| Huang et al. (2020)47 | China, cross-sectional |

Pregnant (84) Postpartum (33) |

Unstimulated saliva |

Pregnant group One time point |

P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, P. nigrscens | 16s rRNA PCR |

P. nigrescens had higher prevalence in the pregnant group (p < 0.01) P. nigrescens exhibited more frequently in late pregnancy than early and middle pregnancy (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01) P. gingivalis in the postpartum group exceeds all of the pregnant stages (p < 0.01) P. intermedia did not show any significant differences among groups |

Fair |

| Sparvoli et al. (2020)48 | Brazil, cross-sectional |

Pregnant (42) Non-pregnant (18) |

Oral swab |

Pregnant group 28–36 weeks GA |

Quantity of OUT and microbiota diversity | 16s rRNA sequencing |

Significant differences in the relative abundance of oral microbiome in pregnant women A significant dominance of Streptococcus and Gemella in pregnant women (p < 0.01 and 0 = 0.03) Shannon diversity index were higher in the non-pregnant group, while the Simpson diversity index was higher in the pregnant group |

Fair |

| Wagle et al. (2020)49 | Norway, cross-sectional |

Pregnant (38) Non-pregnanr (50) |

Saliva |

Pregnant group 18–20 weeks GA |

S. mutans, Lactobacillus | Culturing |

S. mutans were more abundant in pregnant women (p = 0.03) Lactobaciilus did not have the significant difference between the groups |

Fair |

Table 2.

Oral microbial differences between pregnancy stages.

| Author (year) | Country, study design | Groups (no. of subjects) | Sample source | Measurement interval | Microorganisms evaluated | Microbial detection methods | Study findings | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dasanayake et al. (2005)50 | USA, prospective cohort | First time pregnant women (297) | Stimulated saliva |

T1: 3rd trimester T2: Delivery |

S. mutans, S. sobrinus, S. sanguinus, L. acidophilus, L. casei, A. naeslundii, Total Streptococci, Total cultivable organisms | Culturing |

A. naeslundii gsp 2 level decreased with increased GA (p = 0.05) L. casei carriage increased with increased GA (p = 0.04) L. casei levels at the third trimester were positively associated with birth weight (β = 34.1 g; SE = 16.4; p = 0.04) Total Streptococci and total cultivable organism levels at delivery were negatively associated with birth weight After multivariate analysis with average bacterial levels, A. naeslundii gsp 2, L. casei, pregnancy age, and infant gender remained significantly associated with birth weight |

Fair |

| Adriaens et al. (2009)51 | Switzerland, prospective cohort | Healthy pregnant women (20) | Subgingival plaque |

T1: 12 weeks GA T2: 28 weeks GA T3: 36 weeks GA T4: 4–6 weeks postpartum |

37 species including S. mutans, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans |

DNA–DNA hybridization |

N. mucosa increased throughout the pregnancy (p < 0.001) Total bacterial counts No significant differences between T1 and T2 Significant reduction from T1 to T3 (p < 0.05), and further reduction to T4 (p < 0.01) Between T1 and T4, significant differences were found for 8 of 37 species, including S. mutans, S. aureus, polymorphum, P. micra Between measurement intervals, no statistical differences identified for the levels of four periodontal pathogens |

Fair |

| Molnar-Varlam et al. (2011)13 | Romania, prospective cohort | Healthy pregnant women (35) | Stimulated saliva |

T1: 1st trimester (11–12 weeks GA) T2: 2nd trimester (20–22 weeks GA) T3: 3rd trimester (34–35 weeks GA) |

S. mutans, Lactobacillus | Culturing |

Increase of S. mutans during the 2nd and 3rd trimester among women 25–35 years old Increase of Lactobacilli in the 2nd trimester among women 20–24 years old and 30–35 years old The salivary pH increased as the pregnancy progresses |

Fair |

| Martinez-Pabon et al. (2014)52 | Colombia, prospective cohort | Pregnant women (35) | Stimulated saliva |

T1: Between 2nd and 3rd trimester T2: 7 months postpartum |

S. mutans, Lactobacillus spp. | Culturing |

No statistically significant changes in counts of S. mutans and Lactobacillus spp., but a tendency of higher numbers during pregnancy A statistically significant difference in the pH and the buffering capacity of saliva; both lower during pregnancy (p < 0.05) |

Fair |

| DiGiulio et al. (2015)11 | USA, case–control |

Pregnant women (49) Full term (34) Preterm (15) |

Saliva, vaginal, stool, oral swab from molar tooth surface & gum lines | Weekly from early pregnancy until delivery and monthly until 12 postpartum | Not specified; | 16 s rDNA sequencing | The progression of pregnancy is not associated with a dramatic remodeling of the diversity and composition of a woman’s microbiota | Fair |

| Okoje-Adesomoju et al. (2015)53 | Nigeria, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (395) 1st trimester (3) 2nd trimester (100) 3rd trimester (292) |

Mucosal swab | One time point | Klebsiella spp., E. coli, S. albus, Proteus spp., S. aureus, Streptococcus spp., Pseudomonas spp. | Culturing, API 20A identification kits |

Klebsiella species was the predominant isolate from 101 (25.6%) of the women The pattern of microbial culture whether normal for the oral cavity or not did not vary significantly with parity (p = 0.98), trimester of pregnancy (p = 0.94) or oral hygiene status (p = 0.94) |

Poor |

| Machado et al. (2016)54 | Brazil, prospective cohort | Healthy pregnant women (31) | Supragingival & subgingival plaque |

T1: 19 ± 3.3 weeks GA; T2: 48 h postpartum; T3: 8 weeks postpartum |

T. forsythia, C. rectus, P. gingivalis, T. denticola, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens A. actinomycetemcomitans | Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

Changes in the percentage of P. intermedia, F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis, T. denticola, C. rectus and an increase in A. actinomycetemcomitans was noted, but differences were not statistically significant - A significant reduction was seen for P. nigrescens when all three time points were compared (p = 0.01, Friedman test), with a reduction from T1 to T3 (p = 0.002), and T2 to T3 (p = 0.037) |

Fair |

| Balan et al. (2018)12 | Singapore, prospective cohort |

Pregnant women (30) 1st trimester (10) 2nd trimester (10) 3rd trimester (10) |

Subgingival plaque, unstimulated saliva |

T1: 1st trimester (< 12 weeks GA) T2: 2nd trimester (21–24 weeks GA) T3: 3rd trimester (32–36 weeks GA) T4: 6 weeks postpartum |

12 Phyla, 65 genera, 131 species | 16s rDNA sequencing |

Species richness and diversity of the subgingival plaque and saliva samples were relatively stable across the pregnancy The abundance of Prevotella, Streptococcus and Veillonella in both subgingival plaque and saliva samples were more during pregnancy A significant decline in the abundance of pathogenic species, e.g., Veillonella parvula, Prevotella species and Actinobaculum species, was observed from pregnancy to postpartum period |

Fair |

| Goltsman et al. (2018)55 | USA, retrospective cohort |

Pregnant (10) Term delivery (6) Preterm (4) |

Saliva, vaginal, stool, rectal swabs | Every 3 weeks over the course of gestation | 1553 taxa | 16 s rDNA sequencing | Alpha diversity, both inter-individual and intra-individual, remained stable across the pregnancy and postpartum | Fair |

| de Souza Massoni et al. (2019)56 | Brazil, cross-sectional |

Pregnant (52) 1st trimester (16) 2nd trimester (21) 3rd trimester (15) Non-pregnant (15) |

Subgingival plaque | One time point | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, S. oralis, Universal | qPCR |

No significant differences in total amount of bacteria between the groups T. forsythia showed significant differences in quantification between 1st trimester and 3rd trimester, and 1st trimester and non-pregnant (p = 0.048 and p = 0.014) Amount of T. forsythia positively correlated with the diagnosis of gingivitis in pregnant women (p = 0.031) |

Fair |

| Dunlop et al. (2019)57 | USA, retrospective cohort |

African American Pregnant women (122) Oral samples (97) |

Vaginal, oral (tongue, hard palate, gum line) and rectal swabs |

T1: 8–14 weeks GA T2: 24–30 weeks GA |

Not specified | 16S rDNA sequencing |

No difference in Chao1 and Shannon diversity for the vaginal, oral, or gut microbiome across pregnancy for the group overall For the oral microbiota, having a low level of education and receipt of antibiotics between study visits were associated with greater Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, with some attenuation of the effect of education when additionally controlling for prenatal antibiotics |

Fair |

Table 3.

Oral microbial differences responding to prenatal dental treatment.

| Author (year) | Country, study design | Groups (no. of subjects) | Sample source | Measurement interval | Microorganisms evaluated | Microbial detection methods | Study findings | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brambillia et al. (1998) | Italy, RCT |

Treatment group (33) Dietary counseling + Dental Prophy + systematic fluoride (1 mg per day from the last week of 6th month GA) + daily fluoride and CHX mouth rinse Control group (32) Dietary counseling + Dental Prophy + systematic fluoride (1 mg per day from the last week of 6th month GA) |

Unstimulated saliva |

T1: 3rd month GA T2: 6th month GA T3: 9th month GA T4: 6 months postpartum T5-T7: 12, 18, 24 months postpartum, respectively |

S. mutans | Culturing |

A reduction in salivary S. mutans levels in treatment group became significant (p < 0.01) six months after the study began (at T3); S. mutans reduction remained significant (p < 0.001) at the end of the study Children of mothers in treatment group had significantly lower salivary S. mutans levels than those of control-group mothers at 18 months old (p < 0.05) and 24 months old (p < 0.01) |

See Fig. 2 |

| Mitchell-Lewis et al. (2001)59 | USA, prospective cohort |

Treatment group (74) Prenatal Periodontal intervention (Hygiene instruction + full mouth debridement) Control group (90) Postpartum periodontal intervention |

Subgingival plaque |

Treatment group T1: During pregnancy Control group T1: After delivery |

P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, B. forsythus, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, T. denticola, P. micros, C. rectus, E. corrodens, E. nodatum, S. intermedius | DNA-DNA hybridization checkerboard method | Mothers who had pre‐term low birth weight had significantly higher levels of B. forsythus and C. rectus, and elevated counts for the other species examined | Fair |

| Offenbacher et al. (2006)60 | USA, RCT |

Treatment group (40) SRP + polishing + OHI + sonic power toothbrush during 2nd trimester Control group (34) (Supragingival debridement + manual toothbrush during pregnancy) + (SRP 6 weeks postpartum) |

Gingival cervical fluid, subgingival plaque |

T1: < 22 weeks GA T2: Postpartum |

Red cluster P. gingivalis, T. forsythensis, T. denticola Orange cluster F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, C. rectus, A. actinomycetemcomitans |

DNA-DNA hybridization checkerboard method |

No significant changes from baseline to postpartum in the levels of any single bacterial species or cluster among control mothers P. intermedia and P. nigrescens reduction detected in the treatment group (p < 0.05) A composite score of orange-cluster organisms decreased in treatment group (p = 0.03) |

See Fig. 2 |

| Novak et al. (2008)61 | USA, RCT |

Treatment group (413): SRP before 21 weeks GA Control group (410): SRP after delivery |

Subgingival plaque |

T1: 13–16 weeks GA T2: 29–32 weeks GA |

P. gingivalis, T. denticola, T. forsythia, P. intermedia, C. rectus, F. nucleatum, A. actinomycetemcomitans | Realtime PCR | Women in treatment group had significantly greater reductions (p < 0.01) in counts of P. gingivalis, T. denticola, T. forsythia, P. intermedia, and C. rectus than untreated women | See Fig. 2 |

| Volpato et al. (2011)27 | Brazil, prospective cohort |

Treatment group (30) Oral Environment Stabilization (atraumatic caries excavation and fillings + extraction of retained roots) |

Saliva |

T1: Before treatment (70% in 2nd trimester) T2: 1 week after treatment |

S. mutans | Culturing | A statistically significant decrease (p < 0.0001) in S. mutans counts between saliva samples before and after oral environment stabilization | Fair |

| Jaramillo et al. (2012)29 | Colombia RCT |

Pregnant women with preeclampsia (57) Treatment group (26): SRP Control group (31): Supragingival prophy |

Subgingival fluid |

T1: Before treatment T2: Postpartum |

P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, T. forsythia, C. rectus, E. Corrodens, D. pneumosintes, A. actinomycetemcomitans | PCR | The detection of assessed microorganisms did not decrease following periodontal treatment in control group and intervention group | See Fig. 2 |

| Asad et al. (2018)28 | Pakistan, RCT |

Pregnant women with a minimal of 3 decayed teeth Treatment group (32): atraumatic restorative treatment Control group (32): no treatment |

Stimulated saliva |

T1: Before treatment T2: 1 week after treatment |

S. mutans | Realtime PCR |

Salivary S. mutans was reduced after the atraumatic restorative treatment (p < 0.001) Salivary S. mutans remained the same level between the two study time point in the control group (p = 0.29) |

See Fig. 2 |

| Escalante-Medina et al. (2019)62 | Peru, RCT |

Treatment group (23): toothpaste with 10% xylitol Control group (22): toothpaste without xylitol |

Saliva |

T1: Before the use of xylitol toothpaste T2: 14 days after the use of the toothpaste |

S. mutans | Culturing |

No difference in S. mutans among the pregnant women who used xylitol toothpaste compared to those who used toothpaste without xylitol (p = 0.062) Both toothpastes, with and without xylitol, were effective to decrease the count of S. mutans in the saliva of pregnant women (p = 0.001 and p = 0.005, respectively) |

See Fig. 2 |

Table 4.

Association between oral microorganisms during pregnancy and adverse birth outcome—preterm delivery.

| Author (year) | Country, study design | Groups (no. of subjects) | Sample source | Measurement interval | Microorganisms evaluated | Microbial detection methods | Study findings | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hasegawa et al. (2003)63 | Japan, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (88) Threatened premature labor Full term (22) Preterm (18) Healthy (48) |

Subgingival plaque | Not specified | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, T. forsythia | PCR | -Detection of T. forsythia was significantly higher among Threatened premature labor preterm delivery group than the full-term group (p < 0.05) | Fair |

| Dörtbudak et al. (2005)21 | Austria, cross-sectional |

Women at risk for miscarriage or preterm delivery (36) Preterm delivery (6) Full-term delivery (30) |

Amniotic fluid, vaginal smears and dental plaque | 15–20 weeks GA |

Red cluster P. gingivalis, T. forsythensis, T. denticola Orange cluster: F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, C. rectus |

Culturing, PCR |

Detection of pathogens in orange and red clusters of subgingival plaque samples was lower in full-term group (16.7%) compared to preterm group (83.3%) (p < 0.01) Carriage of pathogens orange and red clusters of subgingival plaque samples was higher in preterm group (p < 0.01) The levels of Amniotic IL-6 and PGE2 were significantly higher in women delivering pre-term (p < 0.001); Amniotic IL-6 (r = 0.56, p < 0.01) and PGE2 (r = 0.50, p < 0.01) cytokine levels were correlated with subgingival bacterial counts |

Poor |

| Lin et al. (2007)64 | USA, nested case–control |

Women with periodontal disease (31) Preterm delivery (14) Full-term delivery (17) |

Subgingival plaque |

T1: 22 weeks GA T2: Postpartum |

P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, T. forsythensis, T. denticola, C. rectus,F. nucleatum, A. actinomycetemcomitans | Checkerboard DNA–DNA hybridization |

Postpartum bacterial carriage difference between preterm and full-term groups P. gingivalis, T. forsythensis, P. intermedia, and P. nigrescens (p < 0.05) T. denticola and C. rectus (p < 0.065) Patients with a high level of C. rectus at T1 showed a non-significant tendency to have a higher risk for preterm births (odds ratio [OR] = 4.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.99–21.1) |

Fair |

| Durand et al. (2009)65 | USA, case–control |

Pregnant women (107) Preterm delivery (34) Full-term delivery (73) |

Saliva | One time point at recruitment (from 1st trimester to 8 weeks postpartum) | S. mutans, Lactobacilli spp. | Culturing using commercially kit (CRT bacteria®) |

Preterm group had lower level of Lactobacilli (p = 0.009) No difference in S. mutans carriage between preterm and full-term groups (p = 0.053) |

Fair |

| Hasegawa et al. (2011)66 | Japan, cross-sectional |

High risk (hospitalized) Pregnant women (23) Normal birth weight (8) Low birth weight (15) |

Saliva and Subgingival plaque | 2nd trimester | P. gingivalis | PCR |

P. gingivalis was detected in saliva among 7 out the 15 low birth weight group, and 3 of the 8 normal delivery group P. gingivalis was detected in plaque among 8 out the 15 low birth weight group, and 4 of the 8 normal delivery group No report on statistical data regarding oral P. gingivalis and birth weight |

Fair |

| Sadeghi et al. (2011)67 | Iran. prospective cohort |

Pregnant women (243) Premature delivery (10) Full-term delivery (233) |

Saliva | 20–30 weeks GA | Gram-positive and negative cocci, Gram-positive and negative bacilli, Spirilla, Spirochetes, Fusiform bacteria, Actinomycetes, Yeasts | Culturing, Bacteria gram staining |

A significant statistical difference between the mean of gram-negative cocci and intrauterine fetal death cases (p = 0.04) A significant relationship in the presence of spirochetes in saliva between premature and normal delivery (p < 0.05) No significant relationship for other bacteria |

Fair |

| Cassini et al. (2013)22 | Italy, prospective cohort |

Pregnant women (80) Preterm delivery (8) Full-term delivery (72) |

Subgingival plaque, vaginal samples | 14–30 weeks GA (One time point for microbial analysis) |

A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, T. denticola, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia |

Realtime PCR |

The amount of subgingival P. gingivalis of preterm women was higher than that of term women None of assessed periodontopathogen resulted as correlated to preterm low birthweight |

Fair |

| Ye et al. (2013)23 | Japan, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (95) Threatened premature labor (TPL) Preterm delivery (13) Full-term delivery (34) Healthy women Preterm delivery (1) Full-term delivery (47) |

Subgingival plaque, unstimulated saliva and peripheral blood | 26–28 weeks GA | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. denticola | ELISA |

P. gingivalis detection was more frequently detected among preterm group than full-term group among TPL women No significant difference in detection frequency of A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis and T. denticola between TPL and healthy groups |

Good |

| Andonova et al. (2015)24 | Croatia, case–control |

Pregnant women (70) Preterm delivery (30) Full-term delivery (40) |

Subgingival plaque | 28–36 + 6 weeks GA | P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, F. nucleatum, Bacteroides sp., Veillonela sp., P. micros, S. intermedius, A. actinomycetemcomitans E. lentum | Culturing |

A sevenfold higher risk of development of preterm delivery in women with periodontal anaerobes in subgingival plaque than women without Levels of P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, A. actinomycetemcomitans were statistically significantly higher in preterm births compared to full-term deliveries |

Fair |

| Hassan et al. (2016)68 | Saudi Arabia, Prospective cohort |

Pregnant women (94) Preterm delivery (22) Full-term delivery (72) |

Subgingival plaque | 2nd trimester | P. oralis, V. parvula, P. melanionogenica, P. anaerobius, P. asaccharolticus, C. subterminate, C. perfringens, C. clostridioforme, C. bifermentans, E. lenta, A. meyeri | Culturing | A. meyeri and C. bifermentans were significantly associated with higher odds of preterm birth (11.2 and 5.1), with the estimate of C. bifermentans showing greater precision (95% confidence interval = 1.5, 17.5) (p < 0.05) | Fair |

| Usin et al. (2016)69 | Argentina, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (134) Preterm low birth weight delivery (18) Full-term normal birth weight delivery (116) |

Subgingival plaque | 3rd trimester | P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, T. forsythia, T. denticola, A. actinomycetemcomitans | PCR | P. gingivalis and T. denticola were significantly more prevalent in Full-term normal birth weight delivery group | Fair |

| Costa et al. (2019)25 | Brazil, case–control |

Pregnant women (330) Preterm delivery (110) Full-term delivery (220) |

Gingival crevicular fluid, blood |

T1: During pregnancy T2: at the time of delivery |

P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, F. nucleatum, A. actinomycetemcomitans | DNA-DNA hybridization | Higher periodontopathogenic bacteria burden (PBB) did not increase the risk of preterm birth | Fair |

| Gomez et al. (2020)70 | Colombia, case–control |

Pregnant women (94) Adverse birth outcome (23) Non-adverse birth outcome (17) |

Subgingival plaque, placental samples | During pregnancy | P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, T. denticola, E. nodatum, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum | PCR | P. gingivalis-related placenta infection with adverse pregnancy outcome group reflects high levels of IFN-γ with a significative decreasing of NK-related cytokines (p < 0.05) | Good |

| Ye et al. (2020)71 | Japan, prospective cohort |

Pregnant women (64) Threatened preterm labor (TPL) (Low birth weight) (9) Threatened preterm labor (Normal weight delivery) (19) Control (36) |

Saliva, Subgingival plaque, placental samples | During pregnancy | P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, T. forsythia, T. denticola, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum | qPCR, ELISA | Quantity of P. gingivalis and T. forsythia in plaque samples and detection frequency of P. intermedia in saliva were higher in TPL- Low birthweight delivery than those in TPL-Healthy delivery group and/or in control-healthy delivery group | Good |

| Ye et al. (2020)72 | Japan, prospective cohort |

Pregnant women (95) Threatened preterm labor (TPL) (Low birthweight) (14) Threatened preterm labor (Healthy delivery) (33) Control (48) |

Saliva, Subgingival plaque, placental samples | 26–28 weeks GA | P. gingivalis | qPCR | The detection frequency of P. gingivalis in plaque and placenta were significantly correlated with low birthweight delivery in TPL group. In the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, an amount of P. gingivalis in plaque ≥ 86.45 copies showed a sensitivity of 0.786 and a specificity of 0.727 (AUC 0.792) for predicting low birthweight delivery in TPL | Good |

| Ye et al. (2020)73 | China, prospective cohort |

Pregnant women (90) Preterm low birth weight (PLBW) (22) Healthy delivery (68) |

Saliva | 2nd trimester |

P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, T. forsythia, T. denticola, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, E. saphenum, Fretibacterium sp., R. dentocariosa Human oral taxon (HOT) 360, TM7 sp. HOT 356 |

Culturing, qPCR, ELISA |

There was no significant difference in periodontal parameters and serum IgG levels for periodontal pathogens between PLBW and healthy delivery (HD) groups The amount of E. saphenum in saliva and serum IgG against A. actinomycetemcomitans were negatively correlated with PLBW |

Good |

Table 5.

Impact of periodontal disease on oral microorganisms during pregnancy.

| Author (year) | Country, study design | Groups (no. of subjects) | Sample source | Measurement interval | Microorganisms evaluated | Microbial detection methods | Study findings | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| León et al. (2007)74 | Chile, cross-sectional |

Women with threatened premature labor (26) Gingivitis (8) Periodontitis (12) No-periodontal disease (6) |

Amniotic fluid and subgingival plaque | 24–34 weeks GA | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, E. corrodens, F. nucleatum, Capnocytophaga species, C. rectus, M. micros | Culturing, PCR |

Subgingival plaque samples including P. gingivalis were found in 50.0% (13/26) of patients No difference for P. gingivalis detection between groups with or without periodontal diseases |

Fair |

| Santa Cruz et al. (2013)75 | Spain, prospective cohort |

Pregnant women (170) Periodontitis (54) Non-periodontitis (116) |

Subgingival plaque | 8–26 weeks GA | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, T. forsythia, P. micra, C. rectus, F. nucleatum, E. corrodens, Capnocytophaga spp. | Culturing | Periodontitis was associated with higher detection of F. nucleatum (97.4%), P. intermedia & P. nigrescens (94.9%), P. gingivalis (76.9%) and P. micra (56.4%) with high proportions of microbiota for P. gingivalis (18.9%), P. intermedia & P. nigrescens (3.9%) or F. nucleatum (5.5%) | Fair |

| Tellapragada et al., (2014)76 | India, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (390) Gingivitis (147) Periodontitis (40) No-periodontal disease (203) |

Subgingival plaque | 8–24 weeks GA | P. gingivalis, P. intermedius, P. nigrescens, T. forsythia, A. actinomycetemcomitans, C. rectus, C. ochracea, C. sputigens, E. corrodens, T. denticola | PCR | Women with periodontitis had a higher detection of P. gingivalis, P. intermedius, P. nigrescens, T. denticola (p < 0.05) | Fair |

| Lima et al. (2015)77 | Brazil, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (86) Periodontitis (9) Gingivitis (27) Non-periodontitis (50) |

Gingival crevice sample | During pregnancy | P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, T. denticola, P. intermedia | PCR |

Socransky Red Complex (P. gingivalis, T. forsythia and T. denticola) was not present in pregnant women with healthy periodontium Socransky Red Complex was present in pregnant women with gingivitis (3.7%) and in a higher percentage of pregnant women with periodontitis (33.3%) |

Fair |

| Lu et al. (2016)78 | China, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (72) Periodontitis (36) Non-periodontitis (36) |

Saliva | During pregnancy | P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, T. forsythia, T. denticola, Epstein–Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus | PCR |

The detection rates of included periodontopathic microorganisms were not significantly different between the two groups (p > 0.05) The coinfection rate of EBV and P. gingivalis was significantly higher in the case group than in the control group (p = 0.028) |

Good |

| Yang et al. (2019)79 | USA, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (34) Gingivitis (12) Non-gingivitis (22) |

Saliva and subgingival plaque | 3rd trimester | Multiple taxa | 16S rDNA sequencing and qPCR |

No significant differences in alpha diversity (Chao1 or Shannon index) between groups (p > 0.05) Prevotella and Leptotrichia were more prevalent in healthy participants, whereas Mogibacteriaceae, Veionella and Prevotella were more prevalent in participants in the gingivitis group (p < 0.01) |

Fair |

| Balan et al. (2020)80 | China, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (20) Gingivitis (10) Non gingivitis (10) Non-pregnant women (10) |

Subgingival plaque | 21–24 weeks GA | Multiple taxa | 16S rDNA sequencing and qPCR |

In term of alpha and beta diversity, minimal differences were observed between pregnant women with and without gingivitis Oral bacterial community showed higher abundance of pathogenic taxa during healthy pregnancy as compared with nonpregnant women despite similar gingival and plaque index scores |

Fair |

| Tanneeru et al. (2020)81 | India, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women with preeclampsia (200) With periodontal disease (100) Without periodontal disease (100) |

Subgingival plaque, placental samples | During pregnancy | P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, T. forsythia, T. denticola, Epstein–Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus | PCR | T. forsythia, T. denticola, F. nucleatum, and EBV were detected more in the groups with periodontal diseases in their subgingival samples | Poor |

Table 6.

Impact of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) on oral microorganisms during pregnancy.

| Author (year) | Country, study design | Groups (no. of subjects) | Sample source | Measurement interval | Microorganisms evaluated | Microbial detection methods | Study findings | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dasanayake et al. (2008)82 | USA, Nested case–control |

Predominately Hispanic Pregnant women (262) With GDM (22) Without GDM (240) |

Subgingival plaque, blood, cervico-vaginal samples | 18.2–3.4 weeks GA | C. rectus, F. nucleatum ssp., Nucleatum, T. forsythia, P. gingivalis, T. denticola | PCR | The level of evaluated microorganisms from subgingival plaque had no difference between GDM and non-GDM groups (p > 0.05) | Fair |

| Ganiger et al. (2019)83 | India, case–control |

Pregnant women (60) With GDM (124) Without GDM (325) |

Subgingival plaque | During pregnancy | P. gingivalis, P. intermedia | PCR | P. gingivalis were more frequently detected among women with GDM group (80%) than those ones without GDM (40%) (p < 0.05) | Fair |

| Yao et al. (2019)84 | China, case–control |

Pregnant women (449) With GDM (124) Without GDM (325) |

Supragingival and subgingival plaque | 14–28 weeks GA | Streptococci, Lactobacilli, Tuberculosis bacilli, black-pigmented bacteria, Capnocytophagia, Actinomycetes, E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa K. pneumoniae, A. actinomycetemcomitans, C. albicans | Culturing |

No detection difference between GDM and non-GND groups: streptococci, lactobacilli, actinomycetes, E. coli, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa (p > 0.05) Higher detection in GDM group: Tuberculosis bacilli (p = 0.000), Black-pigmented bacteria (p = 0.026), and Capnocytophaga (p = 0.030) The total number of oral anaerobic bacteria (p = 0.000), tuberculosis bacilli (p = 0.000), Black-pigmented bacteria (p = 0.007), Capnocytophaga (p = 0.000), and Actinomycetes (p = 0.000) was more among GDM group |

Fair |

| Crusell et al. (2020)85 | Denmark, prospective cohort |

Pregnant women (211) With GDM (50) Without GDM (161) |

Unstimulated saliva |

T1: 27–33 weeks GA T2: 9 months postpartum |

Multiple taxa | 16S rDNA sequencing |

Shannon’s diversity and Pielou’s evenness decreased from pregnancy to postpartum, regardless of GDM status (p = 0.0008, p = 0.001, p = 0.007 respectively) During pregnancy (T1), no difference in richness, overall diversity or evenness between GDM and non-GDM women |

Fair |

| Xu et al. (2020)96 | China, Case–control |

Pregnant women (60) With GDM (30) Without GDM (30) |

Saliva and fecal sample | 3rd trimester | Multiple taxa | 16S rDNA sequencing | The GDM cases showed lower α-diversity, increased Selenomonas and Bifidobacterium, an decreased Fusobacteria and Leptotrichia in oral microbiota | Fair |

| Li et al. (2021)87 | China, case–control |

Pregnant women (111) With GDM (42) Without GDM (69) |

Saliva and plaque | 3rd trimester | Multiple taxa | 16S rDNA sequencing | Certain bacteria (e.g. combination of Lautropia and Neisseria in dental plaque and Streptococcus in saliva) in either saliva or dental plaque can effectively distinguish women with GDM from healthy pregnant women | Good |

Table 7.

Impact of systemic health conditions on oral microorganisms during pregnancy.

| Author (year) | Country, study design | Groups (no. of subjects) |

Sample source | Measurement interval | Microorganisms evaluated | Microbial detection methods | Study findings | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contreras et al. (2006)88 | Colombia, case–control |

Pregnant women (373) Pre-eclampsia (130) Non-pre-eclampsia (243) |

Subgingival plaque | 26–36 weeks GA | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, T. forsythia, Campylobacter spp., Eubacterium spp., Fusobacterium spp., P. micros, E. corrodens, D. pneumosintes, b-hemolyticstreptococci, Staphylococci spp., yeast | Culturing |

The prevalence of P. gingivalis, T. forsythensis, and E. corrodens was higher in the preeclampsia group (61.5%, 28.5%, and 49.2%, respectively) than the non-preeclampsia group (p < 0.01) Periodontal disease and chronic periodontitis were more prevalent in the pre-eclampsia group (p < 0.001) |

Fair |

| Herrera et al. (2007)89 | Columbia, case–control |

Pregnant women (398) Pre-eclampsia (145) Non-pre-eclampsia (253) |

Subgingival plaque | 28–36 weeks GA | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, T. forsythia, Campylobacter spp., Eubacterium spp., Fusobacterium spp., P. micros, E. corrodens, D. pneumosintes, b-hemolyticstreptococci, Staphylococci spp., yeasts | Culturing |

P. gingivalis and E. corrodens were more prevalent in the pre-eclamptic women than in healthy group (p < 0.001) All other species studied had non-statistically significant differences between pre-eclamptic group and healthy controls |

Fair |

| Ávila et al. (2011)90 | Brazil, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (140) Rheumatic valve disease (70) Healthy (70) |

Saliva | 2nd–3rd trimester | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. forsythia | PCR | The proportion of P. gingivalis was significantly higher in the saliva of healthy pregnant women (p = 0.004), but not in other species | Fair |

| Merglova et al. (2012)91 | Czech Republic, Case–control |

Pregnant women (142) High risk pregnancy (81) Healthy (61) |

Stimulated saliva | 3rd trimester | S. mutans | Culturing | High levels of S. mutans in the saliva in over 70% of subjects in high-risk pregnancy group | Poor |

| Stadelmann et al. (2015)92 | Switzerland, prospective case–control |

Pregnant women (56) Premature Rupture of Membranes (PPROM) (32) Healthy (24) |

Gingival crevicular fluid, subgingival plaque and vaginal samples |

T1: 20–35 weeks GA T2: 48 h postpartum T3: 4–6 weeks postpartum |

A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, T. denticola, P. intermedia, P. micra, F. nucleatum, F. necrophorum, C. rectus, E. nodatum, E. corrodens, Capnocytophaga species | MicroIDent®plus11 test (PCR, reverse hybridization) |

In PPROM group, there was a statistically significant decrease from T1 to T2 for the microbiological group of major periodontopathogens (A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. denticola, T. forsythia; p = 0.0313) and also for the group of all analyzed bacteria (p = 0.0039) There were no statistically significant differences between groups at any timepoint (p > 0.05) The prevalence of grouped subgingival periodontopathogenic bacteria did not change overtime in the control group (p > 0.05) |

Fair |

| Paropkari et al. (2016)93 | USA, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (22) Smoker (11) Non-smoker (11) Non-pregnant women (22) Smoker (11) Non-smoker (11) |

Subgingival plaque | 21–24 weeks GA | Multiple taxa | 16S-pyrotag sequencing |

Alpha diversity (Shannon index) was not significantly different between all groups (p > 0.05) Pregnant smokers demonstrated clusters that were not seen in either pregnant women or in smokers, e.g., Bradyrhizobium spp., Herbaspirillum, E. coli, Prevotella melalinogenica, Prevotella spp., Corynebacterium spp., Dialister spp. Tannerella spp. Species belonging to the genera Pseudomonas, Acidovorax, Enterobacter, Enterococcus, Diaphorobacterium, Methylobacterium demonstrated significantly greater abundances in pregnant women (both smokers and nonsmokers) |

Fair |

| Jaiman et al. (2018)94 | India case–control |

Pregnant women (30) Pre-eclampsia (15) Non-pre-eclampsia (15) |

Subgingival plaque and placental blood | During pregnancy | P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum | Culturing | No statistically significant association between microorganism in plaque and placental blood between normotensive control and preeclamptic pregnant women | Poor |

| Parthiban et al. (2018)95 | India case–control |

Pregnant women (50) Pre-eclampsia (25) Non-pre-eclampsia (25) |

Subgingival plaque and placental samples | During pregnancy | A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, P. intermedia | qPCR | The subgingival plaque samples of pre-eclamptic women showed significantly higher frequencies of P. intermedia | Fair |

| Tuominen et al. (2018)96 | Finland, case–control |

Pregnant women (40) HPV positive (20) HPV negative (20) |

Mucosal scrapings of oral cavity, and cervix, placenta | 3rd trimester | Multiple taxa | PCR and 16S rDNA sequencing |

Species with increased relative abundance in HPV positive oral samples: Selenomonas spp. (p = 0.0032), Megasphaera spp. (p = 0.026) and TM73 (p = 0.018) Species with decreased relative abundance in HPV positive oral samples: Haemophilus spp. (p = 0.019) HPV positive oral samples displayed higher richness (Chao1 index) (p = 0.0319), but no difference in diversity (Shannon index), comparing to HPV negative samples |

Fair |

| Tanneeru et al. (2020)97 | India, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (200) Pre-eclampsia with periodontitis (100) Pre-eclampsia without periodontitis (100) |

Subgingival plaque and placental samples | During pregnancy | P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, T. forsythia, T. denticola | PCR | Association between periodontal bacteria (P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, T. forsythia) and preeclampsia (detailed data not shown in the article) | Poor |

| Wang et al. (2020)98 | China, cross-sectional |

Pregnant women (61) Hypothyroidism (30) Healthy (31) |

Saliva and fecal samples | During pregnancy | Multiple taxa | 16S rDNA sequencing | The oral cavity of pregnant women in the hypothyroidism group had higher relative abundances of Gammaproteobacteria, Prevotella, Neisseria, and Pasteurellaceae, whereas that of women in the control group had higher relative abundances of Firmicutes, Leptotrichiace, and Actinobacteria | Fair |

GA gestational age, SES social economic status, RCT randomized controlled trial, SRP scaling and root planning.

Figure 2.

Summary of quality and risk of bias assessment using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials and the adapted Downs and Black scoring tool.

The quality of the selected articles was assessed using two methodological validities: (1) Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials31. (2) Adapted Down and Black scoring32 that assess the methodological quality of both randomized and non-randomized studies of health care interventions. A total score of 26 represents the highest study quality.

Oral microbial differences between pregnant and non-pregnant women

Evident changes of oral microbiota were seen among pregnant women, comparing to those of non-pregnant women. A significantly higher amount of total cultivable microorganisms were found in pregnant women comparing to the non-pregnant at each stage of pregnancy42. The plaque bacterial community was more diverse in 3rd trimester pregnant women compared to non-pregnant women44.

Regarding oral pathogens, the prevalence of A. actinomycetemcomitans was significantly higher in pregnant women in each stage compared to non-pregnant women (p < 0.05)15,42. Two studies14,45 assessed S. mutans carriage in saliva, and found that S. mutans carriage increased significantly throughout the pregnancy; particularly, significant differences were seen between women in their first trimester and non-pregnant women (p < 0.0114 and p < 0.0545). The detection of P. gingivalis and P. intermedia increased significantly in pregnant women compared to non-pregnant women17,42. Although no difference was found in terms of C. albicans carriage between pregnant and non-pregnant women45, two studies revealed a higher detection of Candida spp. among women in their late pregnancy stage, comparing to the non-pregnant group42,43.

Oral microbial differences throughout pregnancy stages

Interestingly, seven studies11,12,51,52,54,55,57 revealed a stable oral microbial community during pregnancy. All four studies11,12,55,57 that performed sequencing analysis revealed that microbiota species richness, diversity and composition were relatively stable across the pregnancy stages. The level of S. mutans and Lactobacillus spp. were assessed in two studies13,52. The levels of S. mutans and Lactobacilli increased in both studies, but without statistical signficance52.

Some studies12,39,51 indicated significant differences from pregnancy to the postpartum period. A total bacterial count reduced significantly after delivery (p < 0.01)51. Several species, like S. mutans and Parvimonas micra, showed significant differences in postpartum compared to the early stages of pregnancy51. This finding was also noticed in another study where A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, P. micra showed an abrupt decline after delivery39. A. actonomycetemcomitans, especially, dropped significantly in its amount after delivery (p = 0.039)39. A significant decline in the abundance of pathogenic species from pregnancy to postpartum period was observed as well12.

Impact of prenatal dental treatment on maternal oral flora

Four studies27,28,58,62 revealed lower S. mutans carriage in the group with oral health care intervention during pregnancy compared to the control group. Fluoride and chlorhexidine treatment as a caries-preventive regimen during pregnancy showed a statistical difference in the salivary S. mutans levels between the study and control groups by the end of the 3-month treatment period58. At the end of the pregnancy, the reduction in S. mutans level was still significant in the study group (p < 0.01)58.

Two studies27,28 which conducted oral environmental stabilization, including atraumatic restorative treatment, revealed statistically significant decrease in S. mutans (p < 0.000127 and p < 0.00128) before and after the intervention. Comparatively, there was no significant reduction in salivary S. mutans count in the group who did not get the treatment (p = 0.29)28. Interestingly, children of treated group mothers had significantly lower salivary S. mutans levels than those of untreated group mothers (p < 0.05)58.

Periodontal pathogenic microbiomes did not reveal consistent results. Three studies29,60,61 performed SRP as treatment. Some microbiomes had significantly greater reductions where counts of P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, T. denticola, T. forsythia, and C. rectus was significantly lower in treated women (p < 0.01)61. A similar result was also found with detection of P. intermedia and P. nigrescens reduced significantly in the treatment group (p < 0.05)60. Yet, the study by Jaramillo et al.29 did not detect a significant decrease in the levels of bacterial species between treated and untreated groups. Quality of evidence and strength of recommendation by GRADE assessment is described in ESM Appendix 4. Quality of evidence was assessed with the study design and factors to either increase or reduce the quality for clinical interventional studies. Strength of recommendation was evaluated based on whether all individuals will be best served by the recommended course of action. Depending on whether the course is conditional or discretionary, the recommendation was given either strong or weak.

Impact of periodontal disease on oral microorganisms during pregnancy

Three studies75,79,80 did not identify any significant findings that the clinical periodontal condition and the levels of subgingival microbiome during pregnancy are related to pregnancy complications.

However, when subgingival plaque in women with threatened premature labor was assessed, P. gingivalis was found in the half of patients with periodontal disease74. The presence of Eikenella corrodens and Capnocytophaga spp. were significantly related to preterm birth and low birth weight respectively (p = 0.022 and p = 0.008)75. No statistical significance was found in overall microbiome diversity in comparison of healthy gingiva and gingivitis groups. However, bacterial taxa like Mogibacteriaceae and genera Veillonella and Prevotella were more prevalent in the gingivitis group79.

Association between oral microorganism during pregnancy and adverse birth outcome

Five studies22–24,71,72 showed that the amount of P. gingivalis in subgingival plaque was significantly higher in women with preterm birth than women with term birth. Also, CFU counts of red and orange complex pathogens, in which P. gingivalis belongs, from dental plaque in women with preterm delivery was significantly higher (p < 0.01)21. The levels of Fusobacterium nucleatum, T. forsythia, Treponema denticola, and A. actinomycetemcomitans were highly related to the preterm births compared to term deliveries22,24.

However, higher periodontopathogenic bacteria burden did not increase the risk of preterm birth, despite the increase in periodontal disease activity25. The levels of microorganisms like P. gingivalis, T. forsythensis, T. denticola, P. intermedia, and F. nucleatum were not significantly higher in the preterm group than in the term group64.

Impact of systemic diseases on oral microorganism during pregnancy

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

Two studies82,85 did not find significant differences in either clinical periodontal disease nor in the diversity and richness between women with GDM and non-GDM. The detection rate and the number of oral bacteria in women with GDM were higher than in non-GDM women, especially in the second trimester of pregnancy84. Oral bacterial detection rate and total number in several species, such as black-pigmented bacteria, were significantly higher in pregnant women with GDM than those in non-diabetic pregnant women84. Conversely, oral bacterial detection of oral streptococci and lactobacilli did not show any significant differences84.

Pre-eclampsia

Two studies88,89 performed in Colombia and three studies81,94,95 performed in India revealed the influence of pre-eclampsia on the levels of the oral microbiome. Specifically, the birth weight of newborns were significantly lower in women with pre-eclampsia (p < 0.001)88. P. gingivalis and E. corrodens were more prevalent in the pre-eclampsia group than in the control group88,89. Further, the women with pre-eclampsia had a higher frequency of periodontal disease and chronic periodontitis (p < 0.001)88.

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM)

No statistically significant differences in the oral microbiome were observed in women with PPROM and those without at any time of measurement. However, in the PPROM group, significant decreases in the level of major periodontopathogens were noted from 20 to 35 weeks of gestation to within 48 h after parturition92.

Rheumatic valvular disease, smoking, and HPV

The frequency of periodontal disease in women with rheumatic valvular disease was not significantly different compared to women without the disease90. Smoking was associated with lower levels of gram negative facultative and higher levels of gram-negative anaerobes93. The presence of HPV infection and potential pathogens in oral microbiota composition were positively associated96.

Meta-analysis

A limited number of studies were included for meta-analysis due to the requirement of the same comparisons and outcome measures. Meta-analyses were performed to assess differences of total bacteria carriage, periodontal or cariogenic pathogens between pregnant and non-pregnant women, or between pregnancy stages, and following prenatal dental treatment.

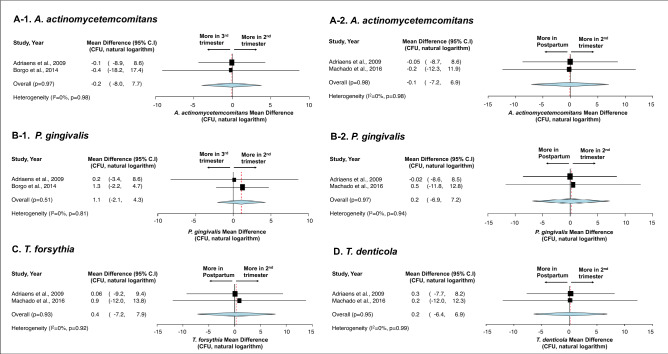

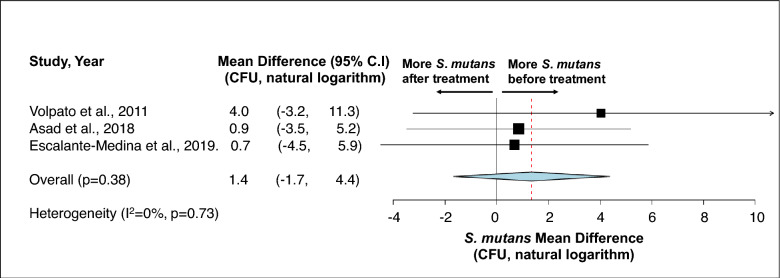

First, no statistical difference was detected in terms of total bacteria carriage in subgingival plaque (Fig. 3)36,39,51 and saliva (Fig. 4)38,42 between different stages of pregnancy and between pregnant and non-pregnancy groups. Second, although more subgingival periodontal pathogens (P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, and T. denticola) were seen among pregnant women in their early stage of pregnancy, and more A. actinomyctemcomitans was seen in the later stage of pregnancy and in postpartum, no statistical significance was detected between groups (Fig. 5)15,51,54. Third, regarding oral Candida, no statistical difference was seen throughout the pregnancy and between non-pregnant and pregnant women (Fig. 6)42,43,45. Lastly, the effects of prenatal dental treatment on salivary S. mutans carriage were evaluated in three studies (Fig. 7)27,28,62. Although no significant difference was found, the reduction of salivary S. mutans was reported upon receiving prenatal dental treatment.

Figure 3.

Impact of pregnancy status on subgingival plaque total bacterial carriage. (A) Mean difference of total bacterial carriage in subgingival plaque between different trimesters of pregnancy. (B) Mean difference of total bacterial carriage in subgingival plaque between pregnancy and postpartum. (C) Mean difference of total bacterial carriage in subgingival plaque between pregnant women and non-pregnant women. Study heterogeneity (I2) and the related p value were calculated using the continuous random effect methods. The Mean Difference, 95% CI of each study included in the meta-analyses and forest plots of comparisons shown in A-1 through C-3 indicate that, regarding total bacterial carriage in subgingival plaque, there is no statistically difference between each stage of pregnancy (p > 0.05), between postpartum and pregnancy (p > 0.05), and between non-pregnant and pregnant women (p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Impact of pregnancy status on salivary total bacterial carriage. Mean Difference of salivary total bacterial carriage in non-pregnant and 2nd trimester pregnant women. Study heterogeneity (I2) and the related p value were calculated using the continuous random effect methods. The Mean Difference, 95% CI of each study included in the meta-analysis and forest plot of comparisons indicate that, regarding salivary total bacterial carriage, there is no statistically significant difference between non-pregnant and 2nd trimester pregnant women (p > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Impact of pregnancy status on the carriage of periodontal pathogens in subgingival plaques. (A) Carriage of A. actinomycetemcomitans during pregnancy trimesters (A-1) and between pregnancy and postpartum (A-2). (B) Carriage of P. gingivalis during pregnancy trimesters (B-1) and between pregnancy and postpartum (B-2). (C) Carriage of T. forsythia between postpartum and 2nd trimester. (D) Carriage of T. denticola between postpartum and 2nd trimester. Study heterogeneity (I2) and the related p value were calculated using the continuous random effect methods. The Mean Difference, 95% CI of each study included in the meta-analyses and forest plots of comparisons shown in (A–D) indicate that, regarding the carriage [measured by colony forming unit (CFU)] of four different periodontal pathogens in subgingival plaque, there is no statistically significant difference between stages of pregnancy and between postpartum and pregnancy (p > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Impact of pregnancy status on salivary Candida carriage. The Mean differences of Candida carriage between 1st and 3rd trimester (A), between non-pregnancy and 1st trimester (B), and between non-pregnancy and 3rd trimester (C) indicated that oral Candida remain stable during the pregnancy and no differences (p > 0.05) are detected between pregnant and non-pregnant women. Study heterogeneity (I2) and the related p value were calculated using the continuous random effect methods.

Figure 7.

Effect of prenatal dental treatment on salivary S. mutans reduction. A meta-analysis was performed on two studies that assessed salivary S. mutans carriage before and after receiving prenatal dental treatment. Study heterogeneity (I2) and the related p value were calculated using the continuous random effect methods. The Mean Difference, 95% CI of each study included in the meta-analysis and forest plot of comparison indicate that, regarding salivary S. mutans carriage, there is no statistically significant difference before and after prenatal dental treatment (p = 0.38).

Discussion

Are pregnant women at more risk for oral disease due to oral microbial changes?

Our study examined the currently available literature that reported oral microbial changes in relation to pregnancy. A fair number of studies reported an increased carriage of total oral bacteria and some disease-specific oral pathogens among pregnant women compared to the non-pregnant or postpartum group. However, meta-analyses only confirmed an increased total bacterium in saliva among pregnant women. Undetected statistical differences of subgingival total bacteria counts and specific oral pathogens between comparing groups could be due to a limited data set. Future studies are warranted to obtain conclusive findings of the association between pregnancy and oral microbial changes.

The oral cavity represents a substantial and diversified microbiota as a result of various ecologic determinants9. The cluster of oral microorganisms harmonizes to maintain oral microbial balance through a symbiotic relationship with their host in a state of health9,99. This balance has a crucial role in maintaining functions and fighting against infections in the oral cavity99. An imbalanced oral microbial community environment could lead to overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria or opportunistic pathogens, causing oral diseases, such as dental caries and periodontal diseases7,8. Previous studies suggested that during pregnancy, women are at higher risk for oral diseases14, due to the hormonal changes, such as estrogen, progesterone, relaxin, and gonadotropin100, and the increased pH in oral cavity from vomiting and craving snacks with high sugar28. It is speculated that pregnancy presents as a special physiological state for women, which could induce changes of the normal flora in the oral cavity1,2. For instance, the significantly higher detection of P. gingivalis and P. intermedia during pregnancy explains the tendency of more significant gingival inflammation in pregnant women15,44. Furthermore, the elevation of A. actonomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis during the early stage of pregnancy predispose pregnant women to be at higher risk for periodontal diseases42.

Are oral microorganisms harbinger for adverse birth outcome?