SUMMARY

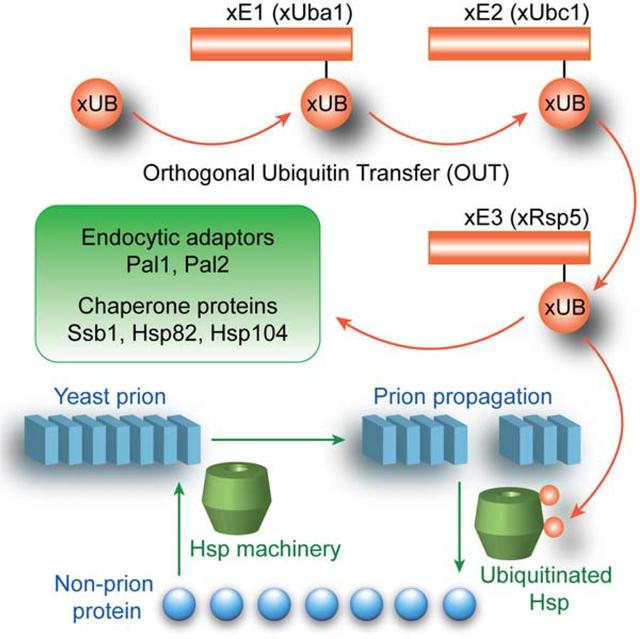

Attachment of the ubiquitin (UB) peptide to proteins via the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic machinery regulates diverse biological pathways, yet identification of the substrates of E3 UB ligases remains a challenge. We overcame this challenge by constructing an “orthogonal UB transfer (OUT) cascade with yeast E3 Rsp5 to enable the exclusive delivery of an engineered UB (xUB) to Rsp5 and its substrate proteins. The OUT screen uncovered new Rsp5 substrates in yeast, such as Pal1 and Pal2 that are partners of endocytic protein Ede1, and chaperones Hsp70-Ssb, Hsp82, and Hsp104 that counteract protein misfolding and control self-perpetuating amyloid aggregates (prions), resembling those involved in human amyloid diseases. We showed that prion formation and effect of Hsp104 on prion propagation are modulated by Rsp5. Overall, our work demonstrates the capacity of OUT to deconvolute the complex E3-substrate relationships in crucial biological processes such as endocytosis and protein assembly disorders through protein ubiquitination.

Keywords: Ubiquitin ligase, protein engineering, yeast prion, chaperone, endocytosis

In Brief

We generated a substrate profile of yeast E3 ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 by following the exclusive transfer of an engineered xUB to Rsp5 substrates through an orthogonal ubiquitin transfer (OUT) cascade. Based on ubiquitination of disaggregase Hsp104 by Rsp5, we uncovered a role for Rsp5 in regulating prion formation and propagation.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Ubiquitination is a pervasive protein posttranslational modification in eukaryotic cells and carries signals for a variety of protein fates including complex formation, degradation, endocytosis, and intracellular trafficking (Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998; Komander and Rape, 2012; Pickrell and Youle, 2015). Ubiquitin (UB) transfer in the cell is mediated by a complex enzymatic cascades, including E1 UB activating enzymes, E2 UB-conjugating enzymes and E3 UB ligases (Pickart, 2001). Difficulties in mapping UB transfer from the E3s to substrate proteins have rendered the cellular functions of various E3s and their associated UB transfer cascades inexplicable (Zhao et al., 2020). Due to development of powerful genetic tools and biochemical assays for protein ubiquitination, yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae provides an excellent model for probing the fundamental mechanisms and biological implications of UB-mediated cell signaling. In this context, yeast E3 Rsp5 has been extensively studied to reveal its roles in a plethora of cell regulatory activities including endocytosis of membrane permease or transporters (Galan et al., 1996; Gitan and Eide, 2000; Horak and Wolf, 2001; Hoshikawa et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2007; Yoshida et al., 2012), protein sorting to the vacuole in partnership with arrestin-related trafficking adaptors (ARTs) (Becuwe and Leon, 2014; Hettema et al., 2004; Li et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2008), processing of transcription factors for gene activation (Hoppe et al., 2000; Shcherbik et al., 2004; Shcherbik et al., 2003), regulation of RNA transport and the stability of ribosome and RNA polymerase II (Domanska and Kaminska, 2015; Huibregtse et al., 1997; Neumann et al., 2003; Shcherbik and Pestov, 2011; Somesh et al., 2007), and protein quality control (Chernova et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2014; Sommer et al., 2014; Tardiff et al., 2013). The multitasking of Rsp5 in diverse processes in the yeast cell prompted us to carry out a systematic screen of its substrates to unravel its connection with various cell signaling pathways.

A diverse tool kit for identifying the substrates of Rsp5 has been developed, and includes affinity screen with the E3 by pulldown or protein microarray (Hesselberth et al., 2006; Huibregtse et al., 1997; Leon et al., 2008), in vitro ubiquitination of substrate libraries immobilized on beads or arrays (Gupta et al., 2007; Kus et al., 2005), and construction of Rsp5-UB fusions as the substrate traps (O’Connor et al., 2015). These approaches have been instrumental in deciphering the function of Rsp5 by plotting its connections with the substrate proteins. Yet screens based on affinity pulldown may miss substrates with low affinity to a particular E3 enzyme, while in vitro ubiquitination reactions would exclude substrates depending on adaptor proteins for recognition by Rsp5. The permutation of Rsp5-UB fusion may change the substrate profile of the E3 since UB would recruit UB-binding proteins for ubiquitination by Rsp5 (Hurley et al., 2006).

Our goal is a comprehensive study of the Rsp5 substrates by directly following UB transfer from the E3 to its substrate proteins in the yeast cells. To achieve this, we extended the “orthogonal UB transfer (OUT)” cascades, developed for profiling the substrates of mammalian E3s E6AP (HECT), and E4B and CHIP (U-box), to Rsp5 in order to identify its substrates in yeast cells (Bhuripanyo et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2017). In OUT, UB variant (xUB) with the R42E and R72E mutations would be rejected by the wild-type (wt) E1 for activation, but instead transferred through an engineered xE1-xE2-xE3 cascade, where “x” denotes enzyme variants that are orthogonal to native enzymes for UB transfer (Zhao et al., 2020). When xUB with N-terminal 6×His tag and biotin tag (HBT-xUB), and the xE1-xE2-xE3 enzyme cascade are coexpressed, xUB could be delivered to the substrate of a designated E3 enzyme. Proteins conjugated with xUB can be tandemly purified via Ni-NTA and streptavidin resins, and identified by proteomics tools, generating a substrate profile of specific E3. We previously used phage display to engineer xUB-xUba1 (E1) and xUba1-xUbc1 (E2) pairs for the exclusive transfer of xUB to a specific xE2 enzyme in yeast cells (Zhao et al., 2012). Here, we engineered the xUbc1-xRsp5 pair by yeast cell surface display to complete the OUT cascade of Rsp5 and used the cascade to deconvolute the substrate specificity of the E3 in yeast cells.

Based on the results of the OUT screen, we uncovered Rsp5-catalyzed ubiquitination of endocytic factors Pal1 and Pal2 (YHR097C) that are partners of a known Rsp5 substrate Ede1 that organizes protein interaction networks to initiate endocytosis (Dores et al., 2010; Moorthy et al., 2019; Weinberg and Drubin, 2014). We have also shown that Rsp5 catalyzes ubiquitination of important chaperone proteins, including the yeast Hsp70 homolog Ssb, the Hsp90 homolog Hsp82, and the disaggregase Hsp104. These chaperones are involved in both antagonizing protein misfolding and modulating formation and propagation of self-perpetuating protein aggregates (yeast prions), that resemble amyloids associated with diseases such as human Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s diseases (Chernova et al., 2017b; Wickner et al., 2020). Indeed, we found that Rsp5 influences prion formation and modulates effects of Hsp104 on the propagation of the prion form of yeast Sup35 protein, [PSI+]. Application of the OUT screen to identifying Rsp5 substrates has thus mapped cellular circuits that are involved in endocytosis and response to self-perpetuating protein aggregation.

RESULTS

Engineering an xUbc1-xRsp5 Pair to Assemble the OUT Cascade of Rsp5

We previously engineered xUB bearing the R42E and R72E mutations to block its activation by the wild-type (wt) Uba1. Correspondingly, we engineered xUba1 with mutations in the adenylation domain (Q576R, S589R, and D591R) so it can activate xUB to form the xUB~xUba1 thioester conjugate. We also added mutations to the UB fold domain (UFD) of xUba1 (E1004K, D1014K and E1016K) to block its interaction with wt E2 (Zhao et al., 2012) (Table S1). To identify an E2 mutant that can pair with xUba1 for the transfer of xUB, we engineered Ubc1 by phage display and found mutations in the N-terminal helix (K5D, R6E, K9E, E10Q, Q12L) would enable the transfer of xUB from xUba1 to the mutant Ubc1 (Zhao et al., 2012). In this study, we identified a tuned-down version of the mutant Ubc1 with the K5D and K9E mutations that sufficed to restore the interaction with xE1 to form the thioester conjugate with xUB (Figure S1A). We thus used the K5D and K9E mutant of Ubc1 as xE2 to generate an OUT cascade of Rsp5 (Table S1). While wt Uba1-Ubc1 supported the self-ubiquitination of wt Rsp5 with wt UB, the xUba1-xUbc1 pair could not deliver xUB to wt Rsp5, suggesting the orthogonality between the OUT cascade and wt E3s (Figure S1B). wt Rsp5 could ubiquitinate Sna3, an endosomal adaptor protein of Rsp5 (MacDonald et al., 2012), yet the xUba1-xUbc1 pair could not transfer xUB to Sna3 through wt Rsp5 suggesting the breakdown of the UB transfer cascade at the xUbc1-wt Rap5 interface (Figure S1C). We thus needed to engineer an xRsp5 with mutations at the E2-HECT interface that could complement the mutations in the N-terminal helix of xUbc1 to set up the OUT cascade tailored for Rsp5.

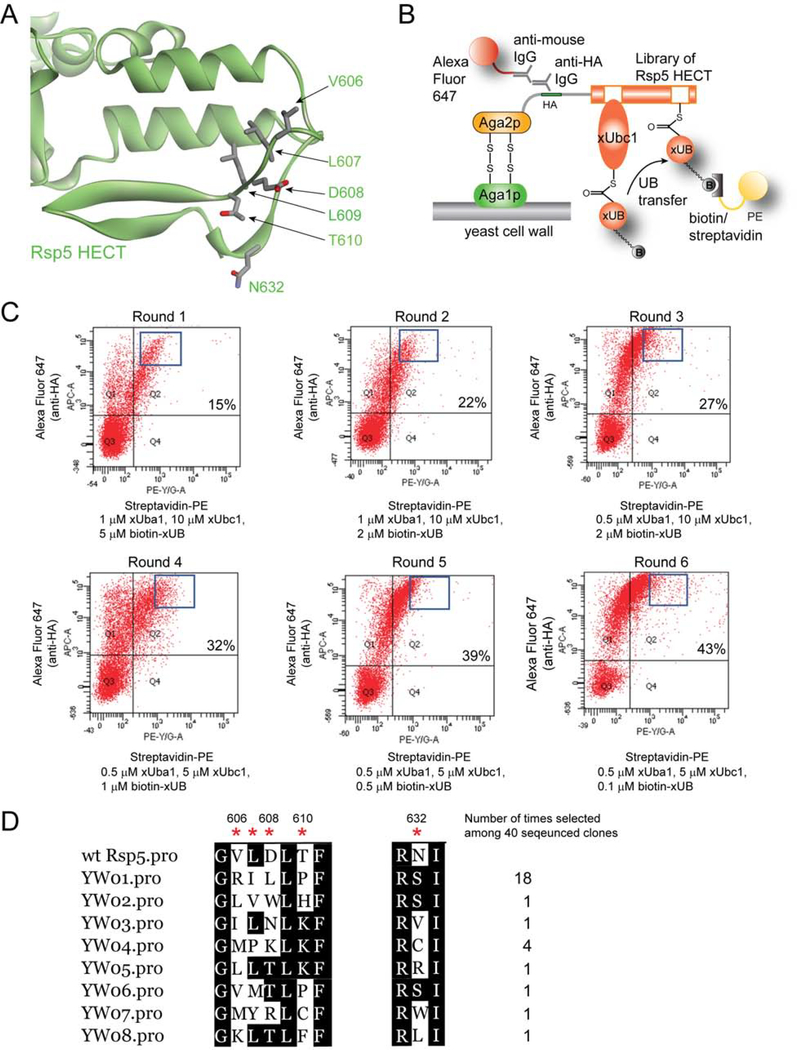

Although the crystal structure of the HECT domain of Rsp5 is available, it does not provide any information on how E2 enzymes, such as Ubc1, would interact with it (Kamadurai et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2011), so we had to rely on the crystal structure of the E6AP HECT domain in the complex with E2 enzyme UbcH7 to guide the design of E2-HECT interactions (Huang et al., 1999). This structure suggests that the loop of HECT domain consisting of 650EDDMMITF657 would bind to the N-terminal helix of UbcH7 via electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions with R5 and K9 residues of UbcH7 corresponding to the K5 and K9 of Ubc1 (Figure S1D). By an analogy, we identified a loop within the Rsp5 HECT domain (604DGVLDLTF611), as well as the residue N632 located in the proximity of this loop that would be able to interact with the N-terminal helix of Ubc1 (Figure 1A and S1E). We thus randomized residues V606, D607, D608, and T610 in the loop region, and N632 near the loop, to generate a library of the HECT domain of Rsp5 to engineer its interaction with xUbc1.

Figure 1. Yeast cell surface display to select for HECT domain mutants of Rsp5 that can pair with xUba1 to transfer xUB.

(A) Crystal structure of Rsp5 HECT domain showing the loop consisting of residues V606, L607, D608 and T610 that would interact with the N-terminal helix of Ubc1. N632 of the HECT domain may also contribute to E2 interactions. We thus randomized these residues to construct the HECT domain library. (B) Yeast cell surface display for the selection of variants of Rsp5 HECT domain that can pair with xUbc1 for the transfer of xUB. The HECT domain library of Rsp5 was displayed on yeast cell surface as fusions with the yeast protein Aga2p (Chao et al., 2006). N-terminal tagged ybbR-xUB was labeled with biotin-CoA by ybbR tag modification catalyzed by Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase (Yin et al., 2006). xUba1 would load biotin-labelled ybbR-xUB (biotin-xUB) onto xUbc1 and the generated xUB~xUbc1 thioester conjugate would react with the Rsp5 HECT domain library displayed on the yeast cell surface. Mutants of HECT domain compatible with xUbc1 in xUB transfer would be covalently conjugated to biotin-xUB and respective yeast cells would be labeled with biotin. After the reaction was done, the cells were washed to remove the free biotin-xUB, xUba1 and xUbc1 enzymes, and were labeled with streptavidin conjugated with the fluorescence protein phycoerythrin (PE). In parallel, a mouse anti-HA antibody and an anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated with Alexa Flour 647 was added to label the cells expressing the HECT domain with an N-terminal HA tag. Yeast cell library was sorted with a dual color fluorescence gate to select for cells with both abundant expression of HECT and biotin-xUB attachment to the HECT domain to enforce the selection of xHECT domains capable of pairing with xUbc1 in the transfer of xUB. (C) Round of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with increasing stringency in reaction conditions and narrower gates of cell collection to enrich clones displaying the HECT mutants conjugated with biotin-xUB. Cells were sorted along the axes of fluorescence from streptavidin-PE and anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 647 to select for catalytically active xHECT mutants. Percentages in each round of sorting designate the fraction of cells in the Q2 region that are positive in both fluorescence channels. (D) After six rounds of selection, the alignment of 30 clones sequenced shows the convergency of the library with YW01 appearing 18 times and YW04 appearing 4 times.

We previously used yeast cell surface display to select for the mutant HECT domain of E6AP that can pair with xUbcH7 to generate the OUT cascade (Wang et al., 2017) (Figure 1B). Here we also used the yeast display platform to select for xUbc1-xHECT pairs with Rsp5 based on the catalytic transfer of biotin-xUB conjugate to the Rsp5 HECT library anchored on surface of yeast cells (Figure S2A–C). We carried out six rounds of selection with increasing stringency and found the library was converged to clones with homologous sequence in the randomized region (Figure 1, C and D). Clone YW1 dominated the library with 18 clones present among the 30 sequenced clones, while YW4 also appeared 4 times. The selected clones showed a pattern of positively charged residues (R/K) replacing the native residues V606, D608 and T610. Since the mutations K5D and K9E on the N-terminal helix of xUbc1 resulted in the reversal of the charge, the selection of the positively charged residues would enable the mutant HECT to complement the negatively charged D/E residues added to the N-terminal helix of xUbc1. Besides charged substitutions, small hydrophobic residues (I/L/M) were selected to replace V606, L or polar residues N/T to replace D608, and hydrophobic P to replace T610. While the native residue L or a close homologue I is strongly preferred at L607, N632 is most accommodating to changes with the selection of small polar residues (S/C) or hydrophobic residues (I/L/V). To confirm the reactivity of the selected yeast clones, we cultured yeast cells displaying individual mutants of YW1–5 and labeled them with biotin-xUB in presence of the xUbal-xUbc1 pair. We found biotin-xUB can indeed be transferred to the individual HECT mutants on yeast cell surface dependent on the catalytic relay of xUbal and xUbc1 (Figure S2D). This suggest that yeast cell surface display was able to identify mutant xHECT with restored transfer of biotin-xUB from xUbc1.

Assembling an OUT Cascade of Rsp5

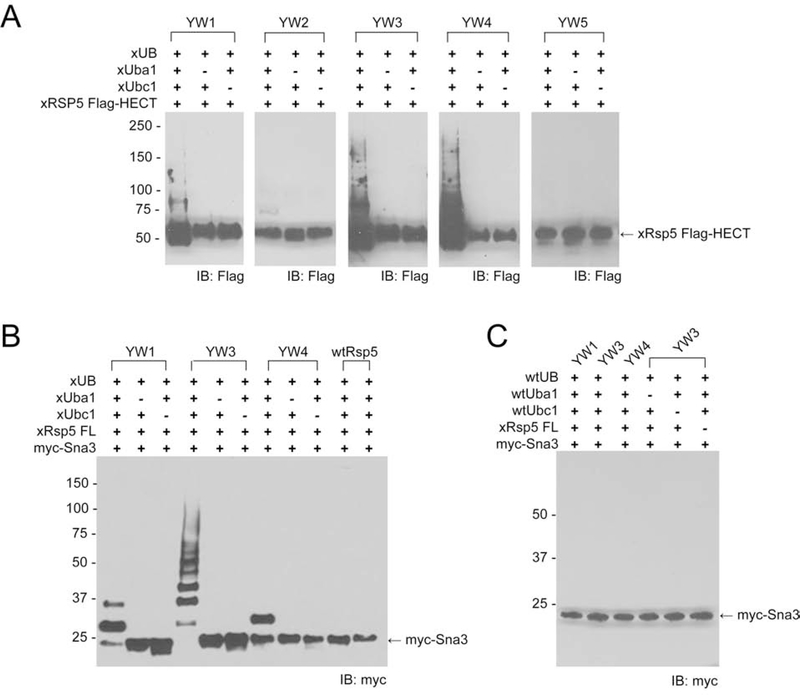

We expressed and purified the Rsp5’s HECT mutants YW1–5 from E. coli and measured their self-ubiquitination with HA tagged xUB (HA-xUB) and the xUbal-xUbc1 pair. HECT mutants YW1, YW3 and YW4 showed the highest degree of self-ubiquitination, confirming the activity of HECT mutants from yeast cell surface display with xUbc1 to mediate xUB transfer (Figure 2A). We then replaced the wt HECT domain in the full-length Rsp5 with the active HECT mutants, i.e. YW1, YW3, and YW4, expressed and purified them from E coli, and assayed their activity in transferring xUB to Sna3, a known Rsp5 substrate (MacDonald et al., 2012). The full length YW3 mutant showed the highest activity in Sna3’s ubiquitination, while YW1 and YW4 demonstrated moderate activities (Figure 2B). In contrast, wild-type Rsp5 was not able to bridge xUB transfer from xUbc1 to Sna3, and neither full length YW3 nor other mutants from yeast sorting were compatible with the wt Ubal-Ubc1 pair to transfer wt UB to Sna3 (Figures S1C, 2B and 2C). These results confirmed the orthogonality of the OUT enzymes with the enzymes of the wt UB-transfer cascade. Since the YW3 mutant of full length Rsp5 demonstrated the highest activity in substrate ubiquitination (Figure 2B), we decided to use this mutant as xRsp5 to assemble the OUT cascade (Table S1).

Figure 2. Verifying the reactivity of the Rsp5 mutants selected by yeast cell surface display in transferring xUB to the Rsp5 substrates.

(A) The mutant HECT domains from yeast selection were individually expressed from E coli with a Flag tag, and their activities in self-ubiquitination by xUB was verified by Western blot with an anti-Flag antibody. (B) The full length Rsp5 was expressed with the incorporation of the mutations in the HECT domain and their activities were compared by transferring xUB to Sna3 through the xUba1-xUbcH7-xRsp5 cascade. YW3 showed the highest activity in Sna3 ubiquitination by xUB and was used as xRps5 in the OUT cascade. (C) Full length Rsp5 mutants YW1, YW3 and YW4 could not rally with the wt Uba1-Ubc1 pair in in transferring wt UB to Sna3.

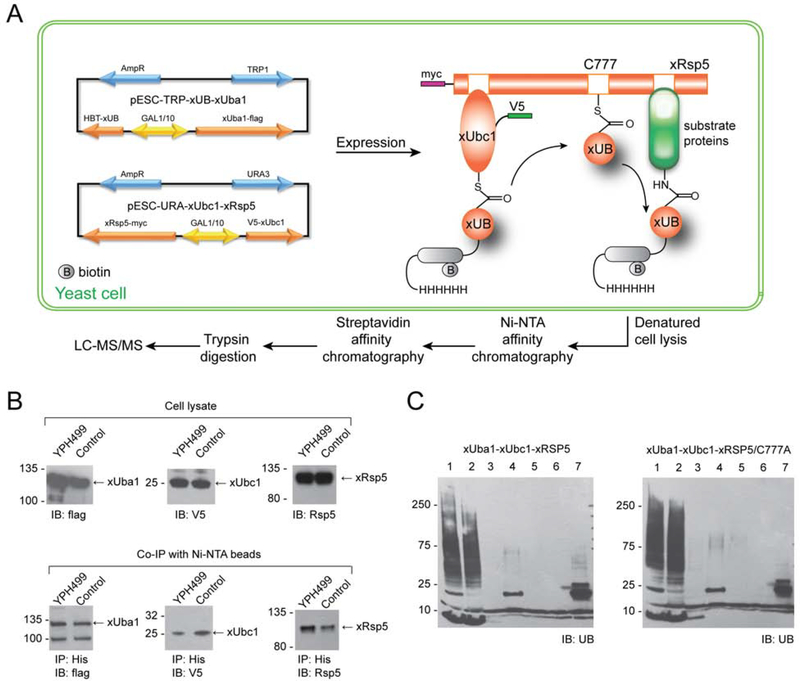

To express xUB and the xUba1-xUbc1-xRsp5 cascade in yeast cells, we cloned the genes of xUB with an N-terminal 6×His and biotin tag (HBT-xUB) and xE1 fused with the FLAG tag into a pESC-Trp vector under the control of a Gal1 and Gal10 promotor, respectively (Tagwerker et al., 2006). Similarly, we cloned the gene of V5-tagged xUbc1 and myc-tagged xRsp5 into a pESC-Ura vector under control of the Gal1 and Gl10 promotors (Figure 3A). We co-transformed the two generated plasmid constructs into the yeast strain YPH499 for expression of HBT-xUB and the Rsp5 OUT cascade. To corroborate our data further, we also mutated the catalytic Cys in the HECT domain of xRsp5 to an Ala (C777A-xRsp5) and co-expressed the mutant with HBT-xUB, xUba1 and xUbc1 cloned into the pESC vectors for comparison of the xUB-modified proteins in two different types of transformants.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the outline for the OUT cascade of Rsp5 in yeast cells to profile its substrates. (A) HBT-xUB and the OUT cascade of xUba1-xUbc1-xRsp5 were expressed from two types of pESC vectors with different selection markers. HBT-xUB would be transferred by the xUba1-xUbc1 pair to xRsp5 and then to its substrate proteins. Cells were then lysed and tandemly purified by binding to Ni-NTA and streptavidin resin for proteomic identification of Rsp5 substrates. (B) Expression of the OUT components in the yeast cells and affinity pulldown with Ni-NTA resin confirmed the formation of covalent conjugates between HBT-xUB and Flag-xUba1, V5-xUbc1 and xRsp5 enzymes. (C) Tandem purification of HBT-xUB conjugated proteins from OUT cells expressing the OUT cascade of Rsp5 (xUba1-xUbc1-xRap5) or the control cells expressing xUba1-xUbc1 pair and xRsp5 with the C777A mutation shedding the catalytic Cys residue. Lane 1, lysate of the yeast cells. 2. flow through of the lysate from the Ni-NTA resin. Lane 3, wash of the Ni-NTA resin. Lane 4, elution from the Ni-NTA resin. Lane 5, flow through from the streptavidin resin. Lane 6, wash from the streptavidin resin. Lane 7, protein bound to the streptavidin resin.

Western blot analysis of the lysates derived from the OUT cells expressing HBT-xUB and the Rsp5 OUT cascade, and from the control cells expressing the same components (except for the replacement of xRsp5 with C777A-xRsp5) confirmed expression of engineered xUB, FLAG-tagged xUba1, V5-tagged-xUbc1, and myc-tagged xRsp5 (Figure 3B, top panels). We also pulled down HBT-xUB conjugated protein with Ni-NTA beads and probed for the co-precipitation of xUba1, xUbc1 and xRsp5 from the cell lysate. We found that both xUba1 and xUbc1 are present in the pulldown fraction suggestion xUB can be loaded on theses enzymes in the cell (Figure 3B, bottom panels). Moreover, we found that xRsp5 was also pulled down with HBT-xUB from the cell lysate, while the C777A-Rsp5 mutant was also present in the pulldown fraction, however to a lower amount (Figure 3B, bottom right). These results imply that HBT-xUB can be transferred to xRsp5 in the cell. The pulldown of the C777A-xRsp5 could be explained by Rsp5’s association with xUB, as was previously demonstrated by the co-crystal structure of the Rsp5 HECT domain in a complex with the wt UB (Kim et al., 2011). Alternatively, HBT-xUB can be transferred from xUbc1 directly to a Lys residue of C777A-xRsp5 bypassing the catalytic Cys, since the engineered binding interface between xUbc1 and C777-xRsp5 would enable their interaction.

Profiling Rsp5 Substrate Specificity in a Yeast Cell by OUT

To profile the Rsp5 substrate specificity in yeast, we cultured OUT cells expressing HBT-xUB and the xUba1-xUbc1-xRsp5 cascade, in parallel with control cells expressing HBT-xUB and xUba1-xUbc1-xRps5/C777A (Figure 3A), prepared cell lysates from equal amounts of the cells and isolated xUB-conjugated proteins by dual affinity purification with Ni-NTA, followed by streptavidin columns. The purification was carried out under denaturing conditions (8 M urea) to minimize nonspecific binding of cellular proteins to the affinity matrix. Purified proteins bound to the streptavidin resin were then digested by trypsin, and peptide fragments were sequenced by LC-MS/MS to identify the proteins conjugated with HBT-xUB (Figure 3C). We compared the peptide spectrum numbers (PSMs) of the MS-identified proteins derived from OUT cell lysates with those of the control cells and catalogued proteins with 2-fold or greater PSM ratios between the OUT and control cells. Experiments were repeated three times to identify proteins showing 2-fold or higher PSM ratio between OUT and control cells in at least two of the repeats. 82 proteins that were consistently enriched in OUT cells over control cells were detected, suggesting that they could be potential substrates of Rsp5 (Data S1).

The substrate profile of Rsp5 generated by OUT contains 12 previously assigned substrate of Rsp5, including membrane transporters for nutrients such as glucose (Hxt6) and metal ions of copper (Ctr1) and zinc (Zrt1) and proton pump Pma1 (Gitan and Eide, 2000; Krampe et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2007; Smardon and Kane, 2014); Rsp5 adaptors Ldb19 (Art1) and Rod1 (Art4) regulating the endocytosis of Pma1 and Hxt6, respectively (Ho et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2008; Llopis-Torregrosa et al., 2016), another Rsp5 adaptor Aly2 (Art3) (Hatakeyama et al., 2010), components of the endocytic machinery, Ede1 and Rvs167 (Dores et al., 2010; Stamenova et al., 2004), as well as multivesicular body-sorting protein Sna3 (Oestreich et al., 2007). Cytoskeleton-associated proteins Lsb1 and Lsb2 (Pin3) previously reported as Rsp5 substrates in stress response (Chernova et al., 2011; Kaminska et al., 2011) were also confirmed by OUT screen. These paralogous proteins are implicated in both endocytosis and the regulation of maintenance of the aggregated (prion) form of Sup35 protein ([PSI+]) during stress (Chernova et al., 2011; Kaminska et al., 2011; Spiess et al., 2013); Lsb2 is also known to promote formation of the [PSI+] prion (Chernova et al., 2011; Derkatch et al., 2001), and can form a stress-induced metastable prion on its own (Chernova et al., 2017a). Presence of these previously known substrates of Rsp5 in the OUT profile agrees with the known roles of Rsp5 in regulating recycling of membrane-associated proteins, coordination of the initiation of endocytosis, and response to stress. The volcano plot showing the changes of protein abundance in affinity purified samples from OUT cells and control cells reveals the Rsp5 E3 of the OUT cascade and its substrates Rvs167, Lsb1, and Hxt6 were among the proteins manifesting the most significant changes with P < 0.05 (−log10P >1.3) (Figure S3A and Data S1).

A majority of the proteins in the substrate profile generated by OUT were not reported as the ubiquitination targets of Rsp5 previously, and many of them do not have an obvious PY motif with a consensus sequence of (L/P)PX(Y/F) for recognition by the WW domains of the E3 (Hesselberth et al., 2006; Staub et al., 1996) (Table S4). Among the potential Rsp5 substrates identified by OUT, Pal1 and its paralog Pal2/YHR097C are respectively known or hypothesized to be involved in endocytosis via interaction with a common partner protein Ede1 that is known to be ubiquitinated by Rsp5 (Dores et al., 2010; Moorthy et al., 2019; Weinberg and Drubin, 2014). The substrate profile of Rsp5 generated by OUT also contains several heat shock proteins including Hsp12, Hsp30, Ssb1 and Ssb2 (yeast homologs of Hsp70), Hsp82 (yeast homologues of Hsp90), and disaggregase Hsp104, involved in prion formation, propagation and elimination in yeast (Bailleul et al., 1999; Chacinska et al., 2001; Chernoff et al., 1995; Kravats et al., 2018; Wickner et al., 2020). Among them, Hsp104 demonstrated the most significant change in purified samples between OUT and control cells with a P value of 0.064 (−log10P = 1.19) (Figure S3A). Due to functional importance of newly identified endocytic protein and prion-related chaperones, we further investigated their ubiquitination by Rsp5 in the yeast cell and in vitro.

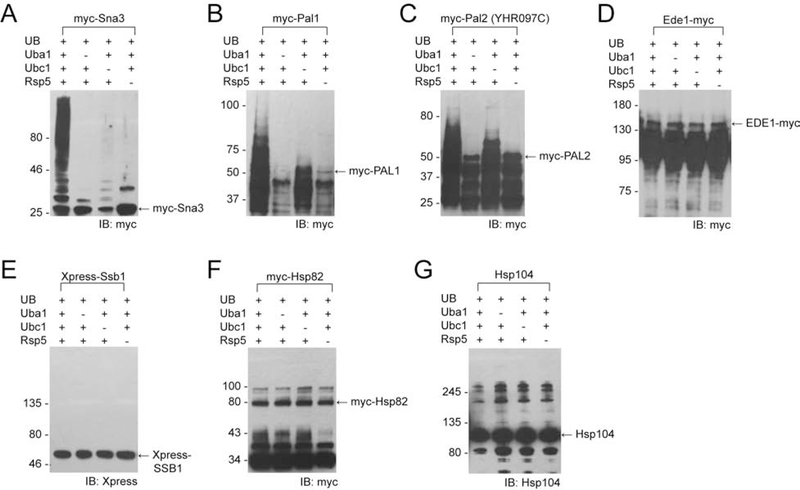

Verifying the Potential Rsp5 Substrates from the OUT Screen in Vitro and in the Cell

To validate Rsp5’s substrates identified by OUT, we used variety of molecular and biochemical techniques. As such, we expressed and purified Pal1, Pal2, Ede1, Ssb1, Hsp82, and Hsp104 from E. coli and incubated these proteins with HA-tagged wt UB (HA-UB) and the wt Uba1-Ubc1-Rsp5 cascade to assay protein ubiquitination biochemically. We found that Pall and Pal2 are ubiquitinated in vitro in Rsp5-dependent manner (Figure 4, B and C). Elimination of Ubc1 from the reaction resulted in low level of Pall and Pal2 ubiquitination, suggesting that some UB could be loaded directly by Uba1 onto Rsp5 and then transferred to the substrates. To corroborate this data further, we tested self-ubiquitination of Rsp5 and Rsp5-dependent ubiquitination of Sna3 in the absence of Ubc1. We found that elimination of Ubc1 from the ubiquitination reaction resulted in self-ubiquitination of Rsp5 and we also detected low-level ubiquitination of Sna3 (Figure 4A). Nevertheless, the results depicted in Figures 4B and 4C confirmed that Rsp5 can directly ubiquitinate Pal1 and Pal2. Alternatively, we generated [35S-Met]-labeled Pal1 in the rabbit reticulocyte in vitro transcription and translation reaction and used it as a substrate in the ubiquitination reaction with wt UB, Uba1, Ubc1 and Rsp5. Consistent with the previous data (Figure 4, B and C), we detected ubiquitination of [35S-Met]-Pal1 in the presence of Rsp5 (Figure S6). Interestingly, Pal1 contains a PPSY sequence, while Pal2 carries a LPSY sequence that likely represents a PY motif that would bind to the WW domain of Rsp5 (Data S1).

Figure 4. Assaying substrate ubiquitination by Rsp5 in vitro with known Rsp5 substrate Sna3 (A) and OUT identified substrates Pal1 (B), Pal2 (YHR097C) (C), Ede1 (D), Ssb1 (E), Hsp82 (F), and Hsp104 (G).

The substrate proteins were expressed from E coli and incubated with wt UB and the Ubal-Ubc1-Rsp5 cascade for the UB transfer reaction. The reactions products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. We used antibodies against the myc or Xpress tag fused to the proteins or antibodies that recognize internal protein epitope, as indicated in the Figure.

Unlike for Pal1 and Pal2, we were unable to detect Rsp5-dependent ubiquitination of Ede1, Ssb1, Hsp82, and Hsp104 in the in vitro system, neither when they were purified from E.coli (Figure 4D–G) nor when they were generated in rabbit reticulocyte (Figure S3B). These proteins do not have a sequence matching the canonical Rsp5-binding PY motif, suggesting that these proteins could be ubiquitinated by Rsp5 in indirect fashion, i. e. in the presence of adaptor protein(s) that mediate recognition of these substrates by the E3. Thus, we tested whether aforementioned putative Rsp5 substrates are ubiquitinated in the yeast cells.

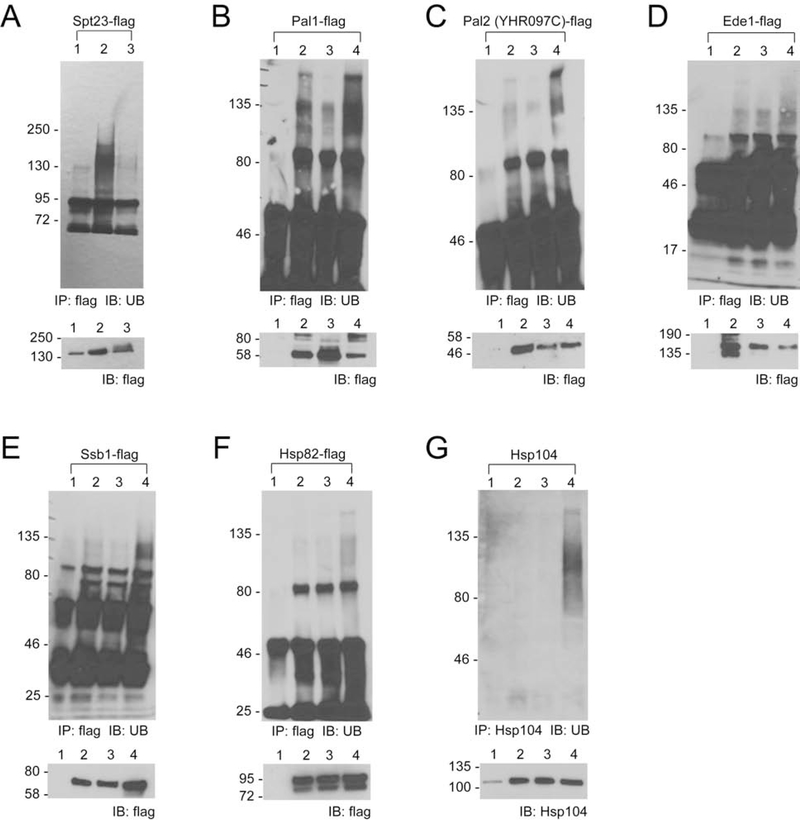

Given that the ubiquitination is a dynamic process that often leads to modified protein degradation via the proteasome, we used the cim3–1 yeast strain, bearing a mutation in the Cim3 subunit of the proteasome that makes a proteasome function temperature-sensitive, ts (Ghislain et al., 1993; Torres et al., 2009), leading to stabilization and accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins at elevated temperature. We expressed the putative Rsp5 substrates in cim3–1 cells together with a dominant negative form of Rsp5 (Rsp5-DN) or wt Rsp5 control (Rsp5-WT) and measured the ubiquitination level of the tested proteins after temperature shift to 37°C (Figure 5). Overexpression of dominant-negative form of the ligase suppresses the active form of the endogenous Rsp5, and indeed we found Spt23, a known Rsp5 substrate, had a decreased level of ubiquitination in cim3–1 cells with co-expression of Rsp5-DN (Figure 5A) (Shcherbik et al., 2002). To accomplish the assay of newly identified substrates, we first immunoprecipitated FLAG-fused Ssb1, Hsp82 and Ede1 via anti-FLAG antibodies, while Hsp104 was immobilized on solid matrix using antibodies that recognize an internal epitope. We also used FLAG-fused Pal1 and Pal2 as an internal control. Captured proteins were eluted from solid support and analyzed via Western blotting using anti-UB antibody to reveal their ubiquitination status/level. Consistent with our in vitro data, Pal1 and Pal2 showed higher levels of ubiquitinated derivatives when wt but not dominant-negative Rsp5 was present in the culture (Figure 5, B and C). Ede1, Ssb1, Hsp82 and Hsp104 showed a similar Rsp5-dependent ubiquitination pattern as Pal1 and Pal2, whereby the higher ubiquitination level of the substrate was detected when wt Rsp5 was expressed (Figure 5D–G). These assays demonstrated that proteins Ede1, Ssb1, Hsp82 and Hsp104 identified by the OUT screen are authentic ubiquitination targets of Rsp5, that likely require additional co-factors for successful and efficient modification by this ligase.

Figure 5.

Assaying the Rsp5-catalyzed substrate ubiquitination in cim3–1 cells shifted to 37°C. Cell cultures were lysed and substrate proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibodies or anti-Hsp104 antibodies (as indicated in the Figure) from cim3–1 cells transformed with empty vector controls (lane 1), cim3–1 cells transformed with the plasmid expressing the substrate protein and an empty vector control (lane 2), cim3–1 cells transformed with the plasmid expressing the substrate protein and the plasmid expressing dominant-negative (DN) Rsp5 (lane 3), and cim3–1 cells transformed with the plasmid expressing the substrate protein and wild-type Rsp5. The precipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting (IB) with an anti-UB antibody. The ubiquitination levels of the known substrate Spt23 (A) and OUT-identified substrates Pal1 (B), Pal 2 (YHR097C) (C), Ede1 (D), Ssb1 (E), Hsp82 (F), Hsp104 (G) are shown.

We further assayed if Rsp5 ubiquitination would affect the stability of the identified substrates in the yeast cells. We expressed the substrate proteins in wt and rsp5–1 cells under the regulation of a TET-Off promoter. Rsp5–1 is a ts allele with a mutation in the HECT domain of Rsp5, that cripples its UB-transferring activity (Dunn and Hicke, 2001) (Figure S4). After inducing substrate expression, we cultured the cell at 37°C and added doxycycline to inhibit the synthesis of substrate proteins following a developed protocol (Li et al., 2015). We then harvested the cell at various time points and measured protein levels by Western blotting. We did not observe significant changes in stability of any substrate protein, suggesting that ubiquitination of Rsp5 would not signal protein degradation by the proteasome (Figure S4B). Likewise, overproduction of neither wt (Rsp5-WT) nor dominant negative mutant (Rsp5-DN) derivative of Rsp5 from galactose-inducible promoter influenced levels of Hsp104 (Figure S5A) and Ssb (Figure S5B) chaperones in yeast cells. Indeed, Rsp5 might install UB chain assembled via K63-linkage signaling for non-degradative function, such as bridging protein interactions (Kee et al., 2005; Kim and Huibregtse, 2009).

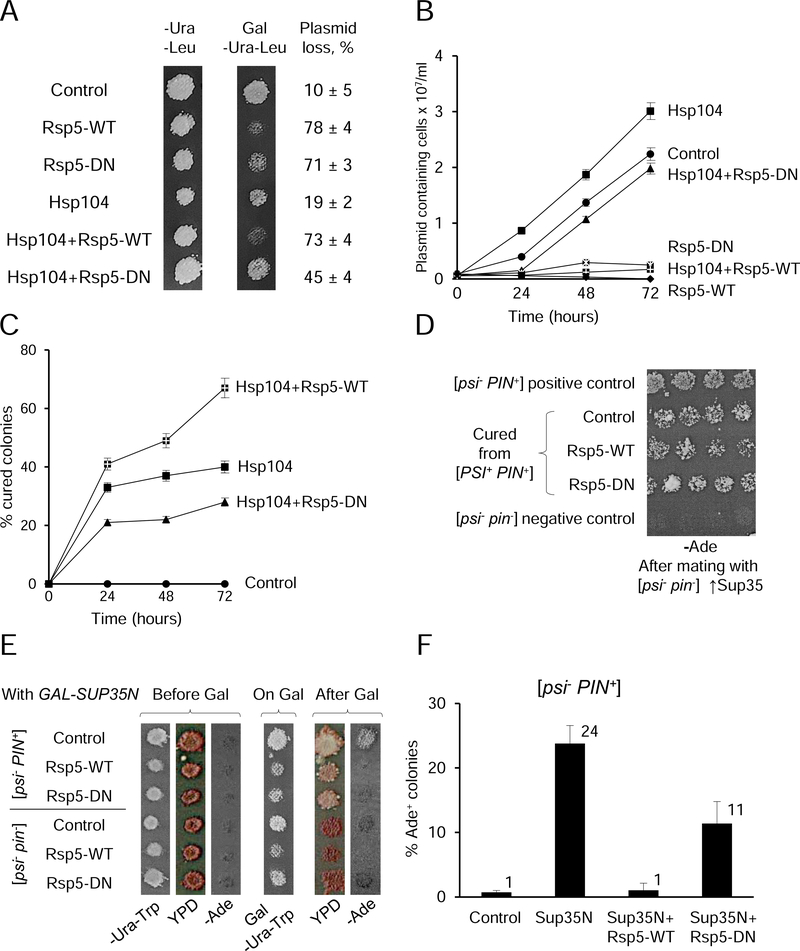

Effects of Overproduction and Inactivation of Rsp5 on Cell Growth and Yeast Prions

Since chaperones identified in our screens as Rsp5 substrates are involved in protein folding and protection from proteotoxic stress (Verghese et al., 2012), we checked if overproduction or inactivation of Rsp5 influences growth of yeast cells, and whether this impact could be modulated by a chaperone. Indeed, high expression of either Rsp5-WT or its dominant negative derivative, Rsp5-DN from galactose-inducible promoter inhibited growth of yeast cultures on solid galactose medium (Figure 6A). While plasmids bearing Rsp5-WT and Rsp5-DN were maintained in more than 90% of cells grown on glucose medium (data not shown), they were lost in 70–90% of cells grown on galactose medium, in contrast to control plasmids lost only in 10–20% of cells (Figure 6A and Table S2). Likewise, proliferation of cells with Rsp5-WT or Rsp5-DN was inhibited in liquid galactose medium selective for plasmids (Figures 6B and S5C, and Table S3). These data are consistent with the notion that galactose-induced expression of Rsp5-WT or Rsp5-DN constructs is detrimental for growth. Notably, simultaneous overexpression of Hsp104 partly rescued growth and plasmid retention in case of Rsp5-DN, but not Rsp5-WT (Figures 6, A and B, and S5C, and Table S2 and S3).

Figure 6. Effects of Rsp5 overproduction or inactivation on yeast growth and prions.

(A) and (B) Inhibition of growth of the yeast strain OT56, bearing the [PIN+] and strong [PSI+] prions, by overproduction (Rsp5-WT) or inactivation (Rsp5-DN) of Rsp5, and impact of excess Hsp104 on growth inhibition. Each culture contained either a combination of two empty vectors (control), or indicated construct with an empty vector, or a combination of two constructs, as shown. Cultures bearing respective constructs under the galactose-inducible promoter were grown either on solid (A), or in the liquid (B) galactose (Gal) medium selective for plasmids, -Ura-Leu; glucose medium (A) is shown as a control. % of cells loosing any or both plasmids, with standard deviations (SDs), as shown on panel A was determined by streaking out for single colonies from Gal medium onto YPD and checking growth on -Ura-Leu. For numbers, see Table S2. For liquid medium (B), aliquots taken at various time points as indicated were diluted as appropriate and plated onto solid -Ura-Leu. Average concentrations of colony-forming plasmid-containing cells in each culture are shown, with error bars depicting SDs. For numbers, see Table S3. Designations are as follows:  Control,

Control,  Rsp5-WT,

Rsp5-WT,  Rsp5-DN,

Rsp5-DN,  Hspl04,

Hspl04,  Hspl04+Rsp5-WT,

Hspl04+Rsp5-WT,  Hspl04+Rsp5-DN. (C) [PSI+] loss in the strain OT56, containing the [PIN+] and strong [PSI+] prions following overproduction of Hsp104 (individually or in combination with Rsp5-WT or Rsp5-DN, as indicated) in the liquid Gal-Ura-Leu medium. Aliquots were taken at specified periods of time, diluted appropriately, and plated onto solid -Ura-Leu, followed by velveteen replica plating onto the YPD and -Ade media for the detection of [PSI+] prion. Average percentages of colonies that have lost [PSI+] prion are shown. Error bars depict SDs. For numbers, see Table S5. Designations are the same as on panel B. Data for the loss of strong and weak [PSI+] variants on solid medium are shown on Figure S5, D and E, and in Table S4. (D) The [PIN+] prion is not lost in the cells of the strain OT56, cured of [PSI+] by excess Hsp104, independently on the presence of Rsp5-WT or Rsp5-DN. Respective [psi−] colonies were mated to the [psi−

pin−] strain GT197, bearing the multicopy plasmid with SUP35 gene. Growth of diploids on the -Ade medium indicates the presence of [PIN+], required for induction of [PSI+] by multicopy SUP35. (E) and (F) Overproduction or inactivation of Rsp5 antagonizes de novo induction of [PSI+] prion by overexpression of PGAL-SUP35N in the [psi−

PIN+] strain, as detected by more reddish color on YPD and less growth on -Ade medium in the plate assay for the strain OT60 (E), and by lesser percentage of Ade+ among colonies grown on -Ura-Trp medium after streaking out from galactose medium for the strain GT159 (F), compared to the culture that overproduced Sup35N alone. Media designated as -Ura-Trp and Gal-Ura-Trp show growth of plasmid-containing cells, while the isogenic [psi−

pin−] strain is shown as a negative control for [PSI+] induction on panel E. Error bars on panel F indicate SDs. For numbers, see Table S6.

Hspl04+Rsp5-DN. (C) [PSI+] loss in the strain OT56, containing the [PIN+] and strong [PSI+] prions following overproduction of Hsp104 (individually or in combination with Rsp5-WT or Rsp5-DN, as indicated) in the liquid Gal-Ura-Leu medium. Aliquots were taken at specified periods of time, diluted appropriately, and plated onto solid -Ura-Leu, followed by velveteen replica plating onto the YPD and -Ade media for the detection of [PSI+] prion. Average percentages of colonies that have lost [PSI+] prion are shown. Error bars depict SDs. For numbers, see Table S5. Designations are the same as on panel B. Data for the loss of strong and weak [PSI+] variants on solid medium are shown on Figure S5, D and E, and in Table S4. (D) The [PIN+] prion is not lost in the cells of the strain OT56, cured of [PSI+] by excess Hsp104, independently on the presence of Rsp5-WT or Rsp5-DN. Respective [psi−] colonies were mated to the [psi−

pin−] strain GT197, bearing the multicopy plasmid with SUP35 gene. Growth of diploids on the -Ade medium indicates the presence of [PIN+], required for induction of [PSI+] by multicopy SUP35. (E) and (F) Overproduction or inactivation of Rsp5 antagonizes de novo induction of [PSI+] prion by overexpression of PGAL-SUP35N in the [psi−

PIN+] strain, as detected by more reddish color on YPD and less growth on -Ade medium in the plate assay for the strain OT60 (E), and by lesser percentage of Ade+ among colonies grown on -Ura-Trp medium after streaking out from galactose medium for the strain GT159 (F), compared to the culture that overproduced Sup35N alone. Media designated as -Ura-Trp and Gal-Ura-Trp show growth of plasmid-containing cells, while the isogenic [psi−

pin−] strain is shown as a negative control for [PSI+] induction on panel E. Error bars on panel F indicate SDs. For numbers, see Table S6.

The Hsp104 chaperone is crucial for the fragmentation and propagation of the endogenous heritable fibrous cross-β polymers, termed yeast prions (Chernoff et al., 1995; Chernova et al., 2017b). Overproduction or inactivation of Hsp104 results in a loss (“curing”) of [PSI+], a prion form of Sup35 protein. Therefore, we checked if overproduction or inactivation of Rsp5 can influence the effect of excess Hsp104 on [PSI+]. Two isogenic strains used in our work contained two different (“strong” and “weak”) variants of the [PSI+] prion, known to differ from each other in their sensitivity to excess Hsp104, and employed the ade1–14 (UGA) reporter for [PSI+] detection. The [PSI+]-containing colonies were visualized by growth on the medium lacking adenine (-Ade), and by whitish (as opposed to red) color on YPD medium, as described previously (Liebman and Chernoff, 2012) and in Method Details. High expression of neither Rsp5-WT nor Rsp5-DN individually from PGAL promoter influenced prion propagation on solid or in liquid galactose medium. In contrast, overproduction of Hsp104 induced significant loss of both strong (less efficiently) and weak (more efficiently) [PSI+] prions, as expected. Co-overexpression of Rsp5-WT together with Hsp104 significantly increased loss of both strong and weak variants of [PSI+], while co-expression of Rsp5-DN with Hsp104 somewhat decreased loss of strong [PSI+] and had no impact on curing of weak [PSI+] (for data, see Figures 6C and S5, D and E, and Tables S4 and S5).

In addition to [PSI+], the strains used in our work also contained the prion form of Rnq1 protein, [PIN+], that is curable by Hsp104 inactivation but not by Hsp104 overproduction (Chernova et al., 2017b; Derkatch et al., 1997). We have checked if colonies grown from cells, that have lost [PSI+] after overproduction of Hsp104 alone or after co-overproduction of Hsp104 with either Rsp5-WT or Rsp5-DN, retained the [PIN+] prion. For this purpose, respective colonies were mated to a [psi− pin−] strain of the opposite mating type containing the multicopy plasmid carrying the SUP35 gene. Overproduction of Sup35 protein or its prion domain, Sup35N, can induce de novo [PSI+] formation efficiently only in the cells containing another prion such as [PIN+] (Derkatch et al., 2001; Derkatch et al., 1997). [PSI+] induction was detected in all colonies cured of pre-existing [PSI+] (Figure 6D), showing that the [PIN+] prion was retained and thus confirming that [PSI+] loss occurred due to an increase in Hsp104 activity, rather than due to dominant inactivation of Hsp104.

Next we checked if Rsp5 modulates de novo induction of the [PSI+] prion. For this purpose, we transiently overproduced the Sup35N construct (bearing the prion domain of Sup35) from the PGAL promoter, either individually or simultaneously with Rsp5-WT or Rsp5-DN, in the [psi− PIN+] strain, followed by detection of [PSI+] appearance on glucose medium, either by growth (-Ade) or color (YPD). As shown previously (Derkatch et al., 1997; Liebman and Chernoff, 2012), transient overproduction of Sup35N induced de novo [PSI+] formation in the strain containing the [PIN+] prion, but not in the control [pin−] strain (Figure 6E). Notably, simultaneous transient co-overproduction Rsp5-WT almost completely eliminated, while simultaneous transient expression of Rsp5-DN slightly decreased the [PSI+]-inducing effect of Sup35N (Figure 6, E and F, and Table S6).

DISCUSSION

Engineering OUT Cascade of Rsp5 to Reveal its Substrates in the Endocytic Pathway

In this study, we used yeast cell surface display to engineer xRsp5 so it can be assembled with the xUba1-xUbc1 pair to generate an OUT cascade for the exclusive transfer of xUB to Rsp5 substrates to enable their identification. The OUT screen of the Rsp5 substrates in yeast identified twelve known substrates, such as membrane transporters and proton pumps as cargos for endocytosis (Hxt6, Ctr1, Zrt1, and Pma1), adaptors for membrane proteins (Ldb19/Art1, Aly2/Art3, and Rod1/Art4), components of endocytic and protein sorting pathways (Ede1, Rvs167, and Sna3), and stress-regulated cytoskeleton associated proteins (Lsb1 and Lsb2). Among the previously unknown substrates of Rsp5 revealed by the OUT screen, we verified Rsp5-catalyzed ubiquitination of Pal1 and Pal2 that interact with endocytic protein Ede1 in vitro and in the cell. We also verified Rsp5-dependent ubiquitination of heat shock proteins Ssb1, Hsp82 and Hsp104 in the cell, although Rsp5 could not ubiquitinate them in a reconstituted reaction in the absence of potential adaptor proteins. Our results demonstrated the effectiveness of the Rsp5-based OUT cascade in identifying its ubiquitination targets.

To engineer Rsp5 for its incorporation into the OUT cascade, we optimized interactions between a E2-binding loop in the HECT domain of Rsp5 and the N-terminal helix of the xUbc1 with K5D and K9E mutations (Figures 1A and S2, and Table S1). We randomized the loop residues and used fluorescence-based yeast cell sorting to select for xHECT mutants that can be paired with xUbc1 to enable the conjugation of biotin-xUB with the catalytically active xHECT displayed on yeast cell surface (Figure 1B). We followed a protocol that is similar to one used for the construction of the OUT cascade for E6AP, a HECT E3 ligase of mammalian cells (Wang et al., 2017). Thus, we envision that the yeast selection platform would be useful for the engineering of other types of HECT E3s that play important roles in cell regulation and disease development (Rotin and Kumar, 2009). The E2-binding loop identified for the Rsp5 HECT domain is a common structural motif in various HECT E3s of mammalian origin, such as E6AP, Smurf1/2 and Nedd1/2, and of yeast origin, such as Toml and Ufd4 (Marin, 2018). By randomizing the E2-binding loop on other HECT E3s and using the high throughput yeast sorting for catalysis-based selection, we can expand the reach of the OUT cascades to other HECT E3s to probe their biological functions.

The substrate profile of Rsp5 generated by OUT in this study shows that paralogous proteins Pal1 and Pal2 are directly ubiquitinated by Rsp5, and identifies Ede1, their common binding partner, as an Rsp5 substrate (Figures 4 and 5). Ede1 is a UB-binding protein functioning as an adaptor in membrane protein endocytosis and sorting through multivesicular bodies (Dores et al., 2010; Lauwers et al., 2010). We verified a previous report on the dependence of Ede1 ubiquitination on Rsp5 in the yeast cell (Dores et al., 2010). However, we could not detect the ability of Rsp5 to transfer UB to recombinant Ede1 from E. coli cells in an in vitro protein ubiquitination assay, suggesting that either some yeast specific Ede1 modifications or an adaptor protein is needed for either Ede1 recognition by Rsp5 or for UB transfer to Ede1 (Figures 4D and 5D). Since Pal1 and Pal2 can bind to Rsp5 directly as suggested by their ubiquitination by Rsp5 in the reconstituted reaction (Figure 4, B and C), and they have been reported to interact with Ede1 by binding to its EPS15 homology (EH) domains (Moorthy et al., 2019), it would be interesting to assay if Pal1 and/or Pal2 could function as an adaptor to mediate Ede1 ubiquitination by Rsp5.

Effect of Rsp5 on Yeast Chaperones and Prions

Our data confirmed that Rsp5 ubiquitinates Lsb proteins, and uncovered chaperones Hsp104 and Hsp70-Ssb as in vivo substrates of Rsp5 (Data S1). All these proteins are implicated in modulating formation and/or propagation of heritable self-perpetuating protein aggregates, termed yeast prions (for review, see Chernova et al., 2017b). Most yeast prions, including prion forms of Sup35 and Rnq1 proteins (respectively [PSI+] and [PIN+]), studied in this work, are fibrillar cross-β polymers of amyloid type, resembling protein aggregates involved in mammalian and human amyloid and prion diseases. Working in complex with Hsp70-Ssa and Hsp40 (e. g., Sis1 or Ydjl), Hsp104 promotes fragmentation of prion polymers into smaller oligomers initiating new rounds of prion multiplication, that is required for the propagation of most yeast amyloid-based prions, including [PSI+] and [PIN+]. When Hsp104 is overproduced in an excess to Hsp70-Ssa/Hsp40, it can bind prion polymers on its own and antagonize propagation of prions such as [PSI+]. Other prions, including [PIN+] are not sensitive to Hsp104 overproduction. Notably, one and the same protein can form multiple prion variants or “strains” that differ from each other by sensitivity to chaperones. In case of [PSI+], “strong” variants are characterized by shorter amyloid core, larger proportion of polymers versus monomers, and more severe impairment of the Sup35 function in termination of translation, as reviewed in (Liebman and Chernoff, 2012). Ubiquitination has previously been shown to modulate formation and propagation of the [PSI+] prion (Allen et al., 2007; Chernova et al., 2003; Tyedmers et al., 2008), however no evidence of direct Sup35 ubiquitination has been reported to date. Ability of Rsp5 to ubiquitinate prion-related chaperones prompted us to check effects of Rsp5 on prion formation and propagation in yeast.

Neither overproduction nor inactivation of Rsp5 influences propagation of [PSI+] on its own, however we have shown that overproduction of Rsp5 promotes curing of both strong and weak [PSI+] variants, while inactivation of Rsp5 impairs curing of the strong and does not impact curing of the weak [PSI+] variant by excess Hsp104 (Figures 6C and S5, D and E). As levels of Hsp104 are not affected by Rsp5 (Figures S4B and S5A), and no effect of Rsp5 on the [PIN+] prion was detected (Figure 6D), the most plausible explanation is that the Rsp5-mediated ubiquitination either hyperactivates Hsp104 or modulates interactions of Hsp104 with other proteins involved in the process of prion propagation. Among other proteins known to influence the [PSI+] prion, Ssb and Lsb2 are ubiquitinated by Rsp5, see (Chernova et al., 2011) and above. Further studies are needed to see if these proteins can modulate effects of Rsp5 on [PSI+].

Transient overproduction of Sup35 protein or its fragments containing prion domain (Sup35N) promotes de novo formation of [PSI+], most efficiently in the cells containing another prion, such as [PIN+], reviewed in (Liebman and Chernoff, 2012). This process is modulated by cytoskeleton-associated proteins, including Lsb2 that is capable of nucleating prion aggregation by Sup35 (Chernova et al., 2017a; Chernova et al., 2011), and by some chaperones, including Ssb that antagonizes de novo prion formation via promoting normal folding of the newly synthesized Sup35 polypeptide (Bailleul et al., 1999; Kiktev et al., 2015). Our data show that the de novo [PSI+] induction by excess Sup35N is drastically impaired by simultaneous Rsp5-WT overproduction, and to a lesser extent, by transient Rsp5 inactivation (Figure 6, E and F). It is possible that the Rsp5-mediated ubiquitination influences prion formation via modulating activity and/or intracellular localization of auxillary proteins, among them Ssb and/or Lsb2.

Our data confirm that that Rsp5 inactivation inhibits growth of yeast cells, and show the inhibitory effect of Rsp5 overproduction (Figures 6, A and B, and S5C). Notably, the concentration of cells containing the Rsp5-WT overproducing plasmid is decreased during the incubation in inducing conditions (see Figures 6B and S5C), indicating that Rsp5 overproduction is not simply inhibitory for growth, but is eventually resulting in cell death. The growth inhibition resulting from Rsp5 inactivation is partly rescued by the excess of the chaperone Hsp104. It is likely that the defect in Rsp5-mediated ubiquitination increases accumulation of toxic misfolded aggregated proteins, that is counteracted by excess Hsp104 (Glover et al., 1997). Interestingly, growth inhibition by Rsp5-DN is more pronounced in the presence of the strong rather that the weak [PSI+] variant (compare Figures 6B and S5C), suggesting that the presence of more efficiently proliferating prion aggregates increases an aggregation burden to yeast cells in the conditions of ubiquitination impairment.

Overall, our data show that Rsp5 modulates formation, propagation and possibly physiological effects of self-perpetuating protein aggregates in a chaperone-dependent manner, that is consistent with our findings demonstrating Rsp5-dependent ubiquitination of the components of prion chaperoning machinery. As both chaperone levels and/or intracellular localization, and Rsp5-dependent protein ubiquitination are mediated by environmental stresses, our results uncover important mechanisms, potentially modulating impact of protein misfolding in natural conditions and likely relevant to human amyloid diseases.

SIGNIFICANCE

The E3 UB ligase Rsp5 regulates key processes in the yeast biology including protein endocytosis, gene activation, and protein quality control. The multifaceted roles of Rsp5 are underpinned by its diverse substrate specificity, yet it has been a challenge to profile E3 substrates due to the transient interactions of the E3-substrate pairs. In this study, we developed a method to enable the direct tracking of UB transfer from Rsp5 to its substrate proteins through an engineered orthogonal UB transfer cascade (OUT). The OUT cascade of Rsp5 is constituted by an engineered set of xE1 (xUba1), xE2 (xUbc1) and xE3 (xRps5) that would enable the exclusive transfer of an engineered xUB to the substrates of Rsp5. xUB shares no cross reactivities with the native UB transferring enzymes, so its labeling of the Rsp5 substrates through the OUT cascade would enable the unambiguous identification of Rsp5 substrates. Using this approach, we generated a comprehensive profile of Rsp5 substrates, and among them, we verified Rsp5-catalyzed ubiquitination of endocytic adaptor proteins Pal1 and Pal2 and chaperon proteins Ssb1, Hsp82 and Hsp104 in the yeast cells. Hsp104 is a disaggregase involved in the propagation of self-perpetuating protein aggregates known as prions, and we further showed that overproduction or inactivation of Rsp5 influences prion formation and propagation in yeast. Overall, our data have provided insights into the cellular roles of Rsp5 and its potential connection to protein misfolding diseases, and established OUT as an empowering proteomics platform for deconvoluting E3-substrate relationships and deciphering the role of E3 in cell biology.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for most resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Jun Yin (junyin@gsu.edu). Requests for yeast prion-containing strains should be directed to Yury O. Chernoff (yury.chernoff@biology.gatech.edu).

Materials Availability

Plasmids generated in this study are available upon request. MTA might be needed.

Data and Code Availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (Perez-Riverol et al., 2019) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD023688.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain EBY100 of the genotype MATa Poali-AGA1::URA3 ura3–52 trpl leu2-Δ200 his3-Δ200 pep4::HIS3 prb1-Δ1,6R can1, used for yeast surface display was provided by K. Dane Wittrup of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Chao et al., 2006). The temperature-sensitive proteasome deficient cim3–1 strain (MATα ura3–52 leu2Δ his3-Δ200 cim3–1) used for the in vivo ubiquitination assay was a kind gift from Charles Mann, Service de Biochimie et de Genetique Moleculaire, Gif-sur-Yvette, France (Ghislain et al., 1993). The YXY705 (rsp5–1) strain originated from strain SEY6210.1 (MATa Ieu2–3,112 ura3–52 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2–801 suc2-Δ9) (Li et al., 2015) bears the mutant rsp5–1 allele that carries the L733S substitution in its HECT domain, with the adjacent TRP1 marker. The yeast host strain YPH499 (Agilent Technologies) of the genotype MATa ura3–52 lys2–801 ade2–101 trpl-Δ63 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 was used to express the OUT cascades for identification of Rsp5 substrates by proteomic approaches. The S. cerevisiae strains used for studying the impact of Rsp5 on yeast growth and prions were isogenic derivatives of the strain 74-D694 (Chernoff et al., 1995), with the following genotype: MATa adel-14 his3-Δ200 leu2–3,112 trpl-289 ura3–52). Derivatives of 74-D694 contain either “weak”, Ψ+7 (strain OT55), or “strong”, Ψ+1 (strain OT56) variant of the Sup35 prion ([PSI+], see (Derkatch et al., 1997; Newnam et al., 1999), or no [PSI+] prion (strain OT60); all these strains also contain the Rnq1 prion ([PIN+]), while the strain GT17 contains neither Sup35 nor Rnq1 prions ([psi− pin−]). Some experiments were repeated, with the same results, in the strains of different genotype, namely [PSI+ PIN+], [psi− PIN+] and [psi− pin+] derivatives of the strain GT81–1C (genotype MATa ade1–14 his3-Δ200 or 11,15 leu2–3,112 lys2 trp1 ura3–52). The [psi− pin−] MATα strain GT197, used as a mating partner in the experiment for [PIN+] detection, originated from GT81–1D, MATα strain isogenic to GT81–1C. Both GT81–1C and GT81–1D originated as haploid spore clones of the homozygous diploid GT81 (Chernoff et al., 2000).

Standard yeast organic YPD (Yeast extract, Peptone and Dextrose) and synthetic media were used (Sherman, 2002). Synthetic medium lacking specific nutritional supplements are denoted by the name of the lacking supplement. (e.g. medium lacking adenine, leucine, tryptophan or uracil are denoted as -Ade, -Leu, -Trp, and -Ura, respectively). Typically, 2% glucose (dextrose) was used as a carbon source. However, 2% galactose (Ga1) for the solid medium, or 2% galactose and 2% raffinose for the liquid medium were added instead of glucose in cases when genes expressed under a galactose-inducible promoter (PGAl) had to be induced. Organic YPG medium containing 2% glycerol instead of glucose was used for identifying respiratory-incompetent (Pet−) colonies that were excluded from analysis. Solid media contained 1.5% agar (US Biologicals). Yeast cultures were incubated at 30°C unless stated otherwise.

Escherichia coli strain XL1-Blue was from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, California, USA), while E. coli strains DH5α and BL21 (DE3) were from Invitrogen (now part of ThermoFisher Scientific, USA).

METHOD DETAILS

Plasmids

pET-15b and pET-28a plasmids (Novagen) were used for expressing UB-transferring enzymes and substrate proteins in E. coli. The yeast expression vector pCTCON2 used for library construction was provided by K. Dane Wittrup of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Chao et al., 2006); this vector bears the galactose-inducible promoter (PGAL) and TRP1 as the selectable marker (Chao et al., 2006). Mutant HECT domains of Rsp5 with an N-terminal Flag tag were expressed from the pET-28a plasmid. Rsp5 HECT genes were amplified by PCR and the amplified fragment was digested with restriction enzymes SacII and NotI for cloning into the pET-28a plasmid for protein expression from E. coli. After selection of the Rsp5 HECT domain library in yeast, the DNA sequences encoding HECT YW1–5 were amplified by PCR from the corresponding pCTCON2 vector. The purified PCR products were digested by SacII and NotI and cloned into pET-28a for expressing the HECT domain mutants from E. coli. Full length Rsp5 was constructed by amplifying the pGEX4-wt RSP5 gene by PCR and the PCR fragment was cloned into pET-28a-Flag vector after double digestion with the SacII and Notl restriction enzymes. Full length xRSP5 fragments were sub-cloned into the pET vector between PstI and NotI sites. pET plasmids for the expression of xUba1 and xUbc1 were from previous studies (Wang et al., 2017).

The genes of the Rsp5 substrates were PCR amplified from the plasmids purchased from Addgene or from yeast genomic DNA and cloned into pET28a vector for their expressing from E. coli. PAL1 and PAL2 were cloned into pET28a by SacII and XhoI digestion, EDE1 by NdeI and XhoI digestion, and Hsp82 NdeI and NotI digestion. Genes of the substrates were cloned into the pESC-LEU2 vector for expression in the yeast cell for in vivo ubiquitination assay. The pESC-based vectors (pESC-LEU2, pESC-URA3 and pESC-TRP1) were purchased from Agilent (catalog #217455). Restriction digestion by NotI and SpeI were used for Pal1 cloning, digestion by NotI and SacI was used for Hsp82 cloning, and digestion by PstI and BssHII was used for Ede1 and Pal2 cloning. Vector pMC189 with a tetracycline-repressible (TET-off) promoter was used for protein expression in yeast for stability assay (Gari et al., 1997). Restriction digestion by BamHI and PstI were used for cloning the HSP82, HSP104 and SSB1 genes into pMC189, digestion by PmeI and NotI was used for cloning of EDE1 and PAL1, and digestion by BamHI and PmeI was used for cloning of PAL2. Plasmids based on pGEX (Stratagene) and encoding GST-Ubc1 and GST-Rsp5 were provided by J. Huibregtse (University of T exas at Austin, TX, U SA).

We used previously generated plasmid constructs for expression of wild-type (WT) and dominant negative (DN) Rsp5 ligase. The Rsp5-DN derivative contains a stop codon right upstream of catalytically-active Cys777 (Shcherbik et al., 2002). Both RSP5 alleles (RSP5-WT and RSP5-DN) were cloned into 2mc pYES2-URA3 (Invitrogen) under the control of a galactose-inducible promoter (PGAL) as described in (Shcherbik et al., 2002), thus generating pYES2-URA3-Rsp5-WT and pYES2-URA3-Rsp5-DN constructs. The original pYES2 plasmid (Invitrogen) was used as URA3 control. The LEU2 shuttle vector pRS315GAL-HSP104 bearing the HSP104 gene under the control of PGAL promoter (Kiktev et al., 2012) was used to overproduce Hsp104. Single copy (centromeric) TRP1 plasmid pFL39GAL-SUP35N (Bailleul et al., 1999) containing the yeast SUP35N-coding fragment under the control of PGAL promoter was used to for the induction of the de novo formation of the [PSI+] prion in the [psi−] strains. Multicopy (2μ) plasmid pSTR7 (Telckov et al., 1986) bearing the SUP35 gene, and control vector and pRS315GAL (LEU2) (Kiktev et al., 2012) have been described earlier.

Protein Expression and Purification

The pET expression plasmids were transformed into BL21(DE3) pLysS chemical competent cells (lnvitrogen) and plated on the LB-agar plates with appropriate antibiotics. Protein expression and purification followed the protocol provided by the vendor of the pET expression system (Novagen) and the Ni-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen).

For protein isolation from yeast and analysis of protein levels, yeast cells grown in liquid medium selective for plasmids were collected by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4 °C, washed by water and resuspended in 2X (relative to cell volume) amount of ice-cold standard lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 0.1 M NaCl; 10 mM EDTA; 4 mM PMSF; 200 μg/ml cycloheximide; 2 mM benzamidine; 20 μg/ml leupeptin; 4 μg/ml pepstatin A; 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM); and 1 complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail from Roche Diagnostics). Cells were then disrupted by agitation with 0.25X (relative to the volume of solution) acid washed glass beads for 8 min at 4°C, followed by removal of glass beads and cell debris by centrifugation at 3000 g for 4 min. Approximate protein concentrations in the samples were determined by the Bradford protein assay (Bio Rad). Protein extracts were normalized using standard lysis buffer, incubated with one-third volume of 4X loading buffer (240 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 8% SDS, 40% glycerol, 12% 2-mercaptoethanol and 0.002% bromophenol blue) for 10 min, and boiled for 10 min prior to loading onto a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel with 4% stacking gel. Electrophoresis was performed in Tris-glycine-SDS buffer (25 mM tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3) for 2 hours at 80V (200 mA) followed by electro-transfer to Trans-Blot® Turbo™ RTA Mini PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad) and blocking with 5% nonfat milk prior to probing with specific primary antibodies overnight and secondary HRP (horseradish peroxidase) conjugate antibodies for 1 hour prior to detection. Visualization of protein signal was detected by using the SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher). Reaction to the Ade2-specific antibody was employed as a loading control. Experiments were repeated with at least three independent cultures with similar results. Densitometry data were obtained using the program ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov ) and averaged from six (Hsp104) or three (Ssb) independent experiments.

Cloning of RSP5 into pCTCON2 Vector and Construction of the Rsp5 Library

The HECT domain gene of Rsp5 was PCR-amplified from pET-Rsp5 by PCR, double-digested with NheI and XhoI, and ligated with pCTCON2 plasmid digested with the same restriction enzymes. Overlapping extension PCR was used to construct a library of Rsp5 HECT domain genes with randomized mutations replacing residues Val606, Leu607, Asp608, Thr610 and Asn632. PCR primers WY7 and WY8 were designed to have NNK codons substituting the codons for the residues to be randomized in the library. These primers paired with WY 5 and WY 6 respectively to amplify fragments of HECT domain gene with randomized codons at residue positions 606, 607, 608, 610 and 632. The two PCR fragments were then assembled by an overlapping extension PCR with primers WY5 and WY6. The amplified PCR fragment was digested with NheI and XhoI, and ligated with the pCTCON2 vector. Transformation of the plasmid library into XL1 Blue competent cells afforded a library of 2.0 × 108 in size, large enough to cover all the mutants with five randomized residues. Transformed XL1 Blue cells were plated on LB-ampicillin plates (LB agar supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin) and allowed to grow at 37°C overnight. Colonies appeared on the plate were scraped and the library DNA was extracted from the scraped cells with the Plasmid Maxiprep Kit (Qiagen).

Yeast Display of the Rsp5 Library

The Rsp5 library in pCTCON2 was chemically transformed into YB100 yeast cells following published protocols with some modifications (Gietz and Schiestl, 1991; Gietz and Woods, 2002). Briefly, yeast cells were first cultured in 200 ml YPD (20 g dextrose, 20 g peptone, and 10 g yeast extract in 1 liter deionized H2O, sterilized by filtration) to an optical density 600 (OD600) around 0.5 at 30°C. The cells were then pelleted at 3,500 rpm for 5 min. Cells were subsequently washed by 20 mL TE (100 mM Tris base, 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and 20 mL LiOAc-TE (100mM LiOAc in TE), before resuspension in approximately 800 mL LiOAc-TE. A typical transformation reaction contained a mixture of 1 mg pCTCON2 plasmid DNA, 2 mL denatured single-stranded carrier DNA from salmon testes (Sigma Aldrich), 25 mL resuspended yeast competent cells, and 300 mL polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution (40% [w/v] PEG 3350 in LiOAc-TE). In order to achieve a library size of 106, 30 transformations were set up in parallel. A control was also prepared in which the pCTCON2 plasmid was excluded. Both the transformation reactions and the control were incubated at 30°C for 1 hour and then at 42°C for 20 min. Cells in each transformation were pelleted by centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 30 s and resuspended in 20 ml SDCAA medium (2% [w/v] dextrose, 6.7 g Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 5 g Bacto casamino acids, 50 mM sodium citrate, and 20 mM citric acid monohydrate in 1 L deionized H2O, sterilized by filtration). Yeast cells were resuspended, pooled together into 1 L SDCAA medium and allowed to grow at 30°C over a 2-day period to an OD600 above 5. For long-term storage of the yeast library, 20 ml of the yeast culture was aliquoted in 15% glycerol stock and stored at −80°C. To titer transformation efficiency, 10 ml of the resuspended yeast transformants from either the library mix or control was serially diluted in SDCAA medium and plated on Trp-plates. The plates were prepared by dissolving 20 g agar, 20 g dextrose, 5 g (NH4)2SO4, 1.7 g Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, and 1.3 g drop-out mix excluding Trp in 1L deionized H2O, autoclaving the media, and pouring the media in petri dishes after cooling down the temperature. Yeast cells transformed with pCTCON2 plasmids were expected to appear within 2 days of incubation at 30°C.

Model Selection of Yeast Cells Displaying Wild-Type Rsp5

Yeast cell EYB100 was transformed with PCTCON2-wt RSP5 HECT and streaked on a Trp- plate. Yeast colonies grew up after two days of incubation at 30°C. Cells were scraped from the Trp- plate to inoculate a 5 ml SDCAA culture that was allowed to shake at 30°C to reach an initial OD600 of 0.5. Cells were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min and induced for HECT domain expression by resuspension in 5 ml SGCAA (2% [w/v] galactose, 6.7 g Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 5 g Bacto casamino acids, 38 mM Na2HPO4 and 62 mM NaH2PO4 dissolved in 1 L deionized H2O, sterilized by filtration). The yeast culture was shaken at 20°C for 16–24 hours. For analysis of Rsp5 HECT display on the surface of yeast cells, 106 cells were resuspended in 0.1 ml Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Mouse anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7392) was used as primary antibodies, and it was added to the cell suspension at a concentration of 10 ng/ml. The cells were incubated with antibodies for overnight at 4°C. The cells were then washed twice with 0.1% BSA in TBS and stained with 5 ng/ml goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen A-21235) in 0.1 ml 0.1% BSA in TBS. The cell suspension was shielded from light and incubated at 4°C for 60 min. After washing twice with 0.1% BSA in TBS, cells were analyzed on a flow cytometer (LSRII, BD Biosciences) to count the number of cells that were labeled with fluorophore. Cells were also analyzed from control labeling reactions in which primary antibody was excluded from the reaction. Typically, 100 μL labeling reaction was set up with 0.5 μM wt Ubal, 5 μM wt UbcH7, 0.1μM biotin-wt UB in a buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2 in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 2 hours at 30°C, and then mixed with 100 μL 3% BSA. During the labeling with primary reagents, 10 ng/ml mouse anti-HA antibody was used. In the following step, 5 ng/ml streptavidin conjugated with PE (Invitrogen, S-32350) and 5 ng/ml goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen A-21235) were used as secondary reagents for the detection of wt HECT domain of Rsp5 on the cell surface and the attachment of biotin-wt UB to the HECT domain.

Selection Procedures for the Rsp5 Library Displayed on the Yeast Cell Surface

The first round of selection for the yeast library was carried out with magnetic-assisted cell sorting (MACS). For subsequent rounds of selection, fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) was used to identify yeast clones displaying Rsp5 mutants that were loaded with biotin-xUB. For MACS selection, reactions of approximately 5X107 yeast cells displaying the HECT domain library of Rsp5 were set up with 5 μM xUba1, 20 μM cUbch7 and 5 μM biotin-xUB in a buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2 in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) in a total volume of 500 μL 0.1% BSA in TBS. After 2 hours at 30°C, cells were pelleted by centrifugation. Cells were then resuspended in fresh 0.1% BSA in TBS and pelleted again. This procedure was repeated twice to remove biotin-xUB probe that was not bound to the yeast cells. After washing, cells were mixed with 100 μL of streptavidin-coated microbeads provided by the mMACS Streptavidin Starting Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, 130–091-287) in a total volume of 1 mL of 0.1% BSA in TBS. Cell suspension was shielded from light and incubated at 4°C for 60 min. After the labeling reaction was finished, the cells and magnetic beads were added to 30 mL of 0.1% BSA in TBS. The cell suspension was pelleted by centrifugation at 500 g for 10 min. The supernatant was aspirated, and the cell pellet including the magnetic beads was resuspended in 500 ul 0.1% BSA-TBS. Yeast cells bound to magnetic beads by biotin-streptavidin interaction were then captured by a magnet according to manufacturer’s instructions, and the beads were washed with 0.1% BSA in TBS. Cells bound to the magnetic beads were eluted into 5 ml SDCAA medium supplemented with 100 mg/ml ampicillin and 50 mg/ml kanamycin and were cultured at 30°C overnight. In parallel, library cells were bound to primary and secondary antibodies to evaluate the display of Rsp5 HECT mutants on the yeast cell surface.

In subsequent rounds of yeast selection, the library cells amplified from the first round of selection were labeled with biotin-xUB and then with 10 ng/ml mouse anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7392). After washing the cells, secondary antibodies of goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen, A-21235) and 5 ng/ml streptavidin-PE (Invitrogen, S-32350) were added to the cells. The labeling reaction was incubated at 4°C for 60 min; then cells were pelleted, washed twice, and resuspended in TBS with 0.1% BSA for sorting. The concentrations of xUba11-xUbcH7, and biotin-xUB were decreased from 1–10-5 μM in the second round of selection to 0.5–5-0.1 μM in the sixth round of selection. The sorting gate also became more stringent with the top 0.5% of doubly labeled cells collected in the sixth round of selection. After the sixth round of cell sorting, the collected cells were grown in an SDCCA medium to an OD600 around 0.5. Zymoprep II Yeast Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, D2004) was then used to extract pCTCON2 plasmid DNA from the yeast cells. The plasmids were transformed into XL1-Blue E. coli competent cells. Individual colonies were miniprepped, and the plasmid DNA was sequenced with Jun304 and Jun305 sequencing primers to reveal the selected mutations in the RSP5 clones. The DNA sequences of the mutant Rsp5 clones were aligned by the ClustalW algorithm in the Lasergene MegAlign software (DNAStar) to confirm the convergency of the library.

Expression of the OUT cascade in yeast

Genes encoding HBT-xUB and Flag-xUba1 were cloned into the pESC-TRP1 vector, and the gens for V5-xUbc1 and myc-xRsp5 were cloned into the pESC-URA3 vector. The resulting plasmids, pESC-Trp-Flag-xUba1/HBT-xUB and pESC-Ura-V5-xUbc1/myc-xRSP5 were co-transformed into yeast stains 499 from Agilent to generate cells for expressing the OUT cascade of Rsp5 (OUT cells). Alternatively, pESC-Trp-Flag-xUba1/HBT-xUB and pESC-Ura-V5-xUbc1/myc-C777A-Rsp5 were co-transformed into yeast strain 499 to generate cells for expression of the OUT cascade with a catalytically inactive xRsp5 (control cells). Yeast cells contain the plasmids were grown in synthetic complete glucose medium lacking uracil and tryptophan supplemented with 4 μM biotin at 30 °C overnight (OD600 is about 1.2). Then cells were grown up in the SC medium contain 2% raffinose for 2 hours at 30 °C and protein expression were induced by 1% galactose at 30°C overnight.

Pull Down Assay and Tandem Purification for Mass Spectrometry

Collected cells were resuspend in urea buffer (8 M urea, 300 mM NaCl, 1% trion-100, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitors cocktail) and then equal volume of glass beads was added. The mixture was agitated on Mini-Beadbeater-16 (BioSpec product) with a 4×60s cycle and the lysate was centrifugated for 10 min at 20,000 g. The supernatant was incubated with Ni-NTA Sepharose resin (Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. The resin washed sequentially with 10 bed volumes of urea buffer, pH 8; 10 bed volumes of urea buffer, pH 6.3; and urea buffer, pH 6.3, supplemented with 20 mM imidazole. After wash steps, proteins were eluted by elution buffer (8 M urea, 200 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 2% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 100 mM Tris, pH 4.3). Eluted proteins were adjusted to pH 8 and incubated with ImmunoPure immobilized streptavidin-agarose (Pierce) overnight at 4°C. The streptavidin resin was washed sequentially with 25 bed volumes of each of the following: wash buffer 1 (8 M urea, 200 mM NaCl, 2% SDS, 100 mM Tris, pH 8), wash buffer 2 (8 M urea, 1.2 M NaCl, 0.2% SDS, 100 mM Tris, 10% ethanol, 10% isopropanol, pH 8), wash buffer 3 (8 M urea, 200 mM NaCl, 0.2% SDS, 100 mM Tris, 10% ethanol, 10% isopropanol, pH 5 and 9), and wash buffer 4 (8 M urea, 100 mM Tris, pH 8). Then the proteins boud to the streptavidin beads were digested by Lys-C/trypsin and analyzed by MS.

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

All in vitro ubiquitination were set up in 50 μL PBS supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP and 2 mM DTT. In each UB transfer reaction, 10 μM of potential substrates (Ede1, Pal1, Pal2, Hsp82, Hsp104 and Ssb1) were incubated with 1 μM wt Ubal, 10 μM wt Ubc1, 2 μM Rsp5, and 20 μM wt UB for variable time at 37°C. The reactions were quenched by boiling in SDS-containing loading buffer, and analyzed by Western blotting probed with c-Myc antibody or substrate-specific antibodies.

Generation of Recombinant Ubc1 and Rsp5 Proteins

Plasmids encoding GST-Ubc1 and GST-Rsp5 were were transformed into E.coli strain BL-21 (Stratagene), and proteins expression was induced with 100 μM IPTG for 4 hrs at 37°C. Cells were pelleted and lysed in lysozyme (1 mg/ml) containing NPN buffer (40 mM Na phosphate pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 1% NP-40, 0.1% triton X-100, 5% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor cocktail 2 μg/ml of leupeptin, 1 μg/μl of pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml of aprotinin and 1μg/ml of soy trypsin inhibitor) for 30 minutes on ice. Bacterial lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 rpms for 30 min, and proteins were bound on glutathione sepharose beads for 4 hrs. The resins were washed 3 times with NPN buffer and the GST tag was removed by treatment of glutathione sepharose bead-captured proteins with GST-fused Precision Protease at 4°C overnight.

[35S-Met] Substrate Labeling and in Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

To generate a [35S-Met]-labeled substrate, we used TNT-coupled rabbit reticulocyte kit from Promega according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As a template, we used PCR products (~1 μg) generated with gene-specific primers. In each set of primers, the forward primer contained T7-polymerase promoter sequence (TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGCCACC). To verify production of a protein in the TNT-reactions reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE, gels were fixed, dried and radioactive signal was visualized by fluorography. Equal amounts of [35S-Met]-labeled protein substrate were taken into in vitro ubiquitination reaction, containing 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl, 125 μM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, 50 μg/ml UB (Sigma), 20 ng of El Ubal (Boston Biochem, cat # E-305), and/or 10 ng of purified yeast Ubc1p. Purified Rsp5p (50 ng) or buffer control was added to initiate the reactions, and the reactions were incubated for 40 min at room temperature. To assess ubiquitination status of substrate protein, reaction products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and radioactive signal was visualized by fluorography.

Verifying Substrate Ubiquitination in cim3–1 Cells

The temperature-sensitive mutant cim3–1 was used to suppress the proteasome by shifting yeast cultures to 37°C. This strain was transformed with various combination of plasmids including: 1) pYES-URA3 + pESC-LEU2 as empty vector control; 2) pYES-URA + pESC-LEU2-Substrate-Flag for expression of the substrate protein; 3) pYES-URA-Rsp5-DN + pESC-LEU2-Substrate-Flag for co-expression of Rsp5-DN with the substrate protein; 4) pYES-URA-Rsp5-WT + pESC-LEU2-Substrate-Flag for co-expression of wt Rsp5 with the substrate proteins. The transformation mixtures were plated onto glucose -Ura-Leu plates and grown in 25°C incubator for 3–4 days until the colonies appear. Single colonies were pick up and grown in 35 mL of -Ura-Leu medium at 25°C to stationary phase. The cells were spun down and resuspend in 35 mL of Gal-Ura-Leu medium for culturing at 25°C for overnight. The cell cultures were then shift to 37°C and incubate for another 7–8 hours. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended with one cell pellet volume of RIPA buffer and add glass beads. The cells were lysed with 12 cycles of 30-second vortexing and 30-seconds on ice. The concentration of the cell lysates were measured and same amounts of total protein (around 1 mg) were used to for co-immunoprecipitation with 25 μL M2-agarose resin for each sample. The lysates were incubated with the M2 beads at 4°C for 5–6 hours, and after that the beads were washed and heated at 98°C for 5 min with 25 μL of 1xSDS-PAGE loading dye to elute precipitated proteins. 10 μL of each sample was loaded onto 8% SDS-PAGE gels and transfer onto nitrocellulose membranes for Western blot analysis. The blot was probed with an anti-UB primary antibody for Co-IP assay and with an anti-Flag primary antibody to verify substrate expression in cell lysate.

Assaying Substrate Stability in Yeast Cells