Abstract

Background

Data regarding vascular access device use and outcomes are limited. In part, this gap reflects the absence of guidance on what variables should be collected to assess patient outcomes. We sought to derive international consensus on a vascular access minimum dataset.

Methods

A modified Delphi study with three rounds (two electronic surveys and a face-to-face consensus panel) was conducted involving international vascular access specialists. In Rounds 1 and 2, electronic surveys were distributed to healthcare professionals specialising in vascular access. Survey respondents were asked to rate the importance of variables, feasibility of data collection and acceptability of items, definitions and response options. In Round 3, a purposive expert panel met to review Round 1 and 2 ratings and reach consensus (defined as ≥70% agreement) on the final items to be included in a minimum dataset for vascular access devices.

Results

A total of 64 of 225 interdisciplinary healthcare professionals from 11 countries responded to Round 1 and 2 surveys (response rate of 34% and 29%, respectively). From the original 52 items, 50 items across five domains emerged from the Delphi procedure.Items related to demographic and clinical characteristics (n=5; eg, age), device characteristics (n=5; eg, device type), insertion (n=16; eg, indication), management (n=9; eg, dressing and securement), and complication and removal (n=15, eg, occlusion) were identified as requirements for a minimum dataset to track and evaluate vascular access device use and outcomes.

Conclusion

We developed and internally validated a minimum dataset for vascular access device research. This study generated new knowledge to enable healthcare systems to collect relevant, useful and meaningful vascular access data. Use of this standardised approach can help benchmark clinical practice and target improvements worldwide.

Keywords: quality measurement, performance measures, patient safety, information technology, healthcare quality improvement

Introduction

International healthcare systems have made advances in promoting a safety culture with high levels of reporting. Despite this, data collected by routine sources on vascular access devices are fragmented, incomplete or non-specific, failing to capture important vascular access or patient outcomes. While other routine data sources or surveillance systems focus on incidence, prevalence and mortality data for specific health or patient groups (eg, minimum dataset (MDS) on ageing and older persons)1 standardised, routine vascular access data capture exists for relatively few countries. Therefore, aggregate data are difficult to obtain, and concerns arise regarding the paucity and quality of available data. Further, use of non-standardised item measurement and definitions make benchmarking performance, conducting risk factor analyses or cost-effectiveness investigations difficult. At present, there is no common standard name for each type of vascular access device, and this inconsistency leads to confusion and further affects data capture and performance measurement. The lack of vascular access data capture severely hinders the measurement of safety performance and establishing best practice worldwide, thus adversely impacting outcomes in hospitalised patients.

Annually, millions of vascular access devices are used across the globe, for indications ranging from intravenous medication and fluid administration to haemodynamic monitoring and the delivery of life-saving treatments such as vasopressors and chemotherapy. Despite their prevalence, 69% of peripheral2 3 and 25% of central venous catheters4–6 fail prior to treatment completion. High failure rates and associated complications have been recognised internationally for their contribution to patient harm and increased healthcare expenditure.7 Yet, how best to define failure and measure specific aspects related to device characteristics, device care and outcomes remains unclear. In fact, limited guidance exists regarding which data items related to vascular access devices are necessary to benchmark practice and evaluate improvement initiatives.

A vascular access MDS for use within healthcare organisations could help quantify and evaluate the number of vascular access devices inserted, rate of catheter complications, failure and performance gaps. This approach would mirror quality improvement efforts in other healthcare specialities and industries, including cardiac surgery,8 geriatric care,1 system level incident reporting9 and aviation.10 While several MDS have been developed for specific healthcare specialities in a range of countries, these datasets are either generic to the country or specialty, or specific to a patient device (eg, central venous catheter) or population (eg, intensive care patients).11–13 As vascular access devices are required by most hospitalised patients, existing datasets do not reflect the unique needs of clinicians, consumers and health services seeking to evaluate vascular access care delivery and outcomes. The objective of this study was to gain international consensus from healthcare professionals specialising in vascular access regarding clinically important and feasible items to include in a vascular access MDS.

Methods

Study design

We used a modified Delphi14–16 process consisting of two electronic survey rounds, followed by an in-person panel meeting, to define an international MDS for vascular access practice and outcome measurement.17 The aim of this Delphi process was to devise a final MDS and accompanying device nomenclature that (1) support evidence-based practice, (2) are pragmatic to collect and valuable to the health service and (3) facilitate benchmarking and practice evaluation and improve practice.

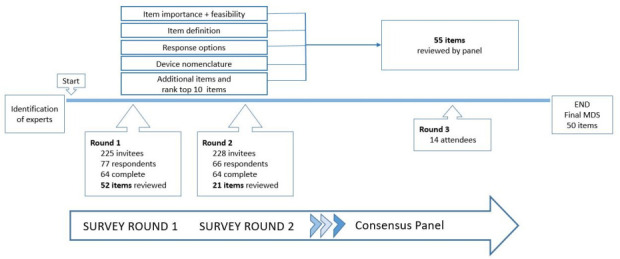

The Delphi process is a method of generating consensus among experts, while the survey gives anonymity and equal influence to all participants (figure 1).18 This method is increasingly used to attain consensus regarding core outcomes in clinical trials,19 implementation strategies20 and MDS.16 21 Written consent was waived for survey participants as participation implied consent, and written informed consent was obtained from Round 3 consensus panel participants for audio recording.

Figure 1.

Delphi rounds. MDS, minimum dataset.

Participants

Using purposive sampling, healthcare professionals specialising in vascular access were identified via global professional and investigator networks (ie, the Association for Vascular Access, the Vascular Access Management Global Initiative, World Congress of Vascular Access (WoCoVA) to participate in defining an MDS. We invited individuals via email to participate in the study, and later expanded to a general invitation via social media. We convened healthcare professionals specialising in vascular access across health disciplines (ie, medicine or nursing), clinical specialty (ie, infectious disease, critical care, emergency medicine, anaesthesiology, interventional radiology, haematology/oncology, surgery, paediatrics, neonatology, infection prevention and patient safety and quality) and geography (Oceania, Canada, Europe, Southwest Asia, North and South America) to generate consensus regarding data items.

For Round 3, leading international experts across disciplines who are respected scholars or researchers, represent professional societies, or have substantial clinical experience in the field were invited to participate.22 23 Panel representation, including specialty, is outlined in online supplemental material 1.

bmjqs-2020-011274supp002.pdf (36.7KB, pdf)

Definition of methodological terms

Participants were asked to assess all items’ importance, feasibility and acceptance over three rounds. Measurement scales were based on scales reported in studies of similar methods.9 15 16 Item importance was defined as the importance of including an item in the MDS. Item importance was assessed on a 9-point Likert scale. A score of 7–9 indicated the item was of ‘critical importance’, a score of 4–6 indicated ‘important but not critical’ and a score of 1–3 indicated ‘limited importance’.24 Item feasibility assessed the feasibility of collecting data on the item. Item feasibility was measured using a 3-point Likert scale as ‘not feasible’, ‘somewhat feasible’ or ‘feasible’. Acceptability of item definition and response options (eg, for gender, male, female, indeterminate) and device nomenclature were assessed on a 4-point Likert scale from ‘not acceptable’, ‘acceptable with major revision’, ‘acceptable with minor revision’ or ‘acceptable’. Consensus for those questions answered by a scale was prespecified as ≥70% of participants in agreement (eg, of an item’s importance).25 26

Study procedures

Dataset development

Original (Round 1) items were based on our scoping review of vascular access outcome measures and quality indicators27; interviews with healthcare professionals28; international peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC)29 and central venous access device research30; and international31 and local quality databases.32 To facilitate development and ensure appropriate domains were included, data items were categorised into five areas: patient characteristics, device characteristics, insertion characteristics, management characteristics, and complication and removal items. Device nomenclature were developed following a review of international vascular access standards and guidelines.22 33 Participant demographic data (eg, age, geography, discipline) were collected with data items. Sequential surveys were administered online via REDCap.34 35

Delphi survey rounds

Round 1: Survey participants were asked to rate item importance and feasibility of collecting item data. Participants also assessed item definitions, response options and device nomenclature acceptability. At the end of Round 1, survey respondents were invited to suggest revisions to item definitions, response options, device nomenclature and additional items for consideration in Round 2.

Round 2: Survey participants reviewed items excluded from Round 1 (those who failed to reach consensus for importance and feasibility) and re-rated these items as yes/no/unsure for inclusion.9 16 Survey participants were provided Round 1 median scores and range for excluded items (those who failed to reach consensus for importance and feasibility) and re-rated. We performed this re-review to ensure that items were not inadvertently selected for removal. Additional items proposed by Round 1 respondents were reviewed in Round 2 and rated for importance and feasibility of data collection. In this way, Round 2 helped to further refine Round 1 ratings. Round 2 participants were also invited to rank their top 10 priority items. Only data items that were rated as important (median score of ≥7) and feasible to collect (median score of somewhat feasible or feasible) advanced into Round 3.24 In this way, we ensured the creation of a minimum set of variables that were considered most important. All definitions that did not reach consensus for acceptable were discussed in Round 3 and amended as per panel recommendations. We did not prohibit Round 1 and 2 participants from sharing the survey link with other colleagues.

Expert consensus panel

Round 3: To generate final recommendations, an international panel of 14 healthcare professionals specialising in vascular access from 11 countries (all of whom had been participants in Rounds 1 and 2) were convened in São Paulo, Brazil, on 16 July 2019 (coinciding with the WoCoVA conference) for a 1-day face-to-face meeting. This smaller group was tasked with the role of reaching consensus on item importance and feasibility, acceptability of item definition, response options and device nomenclature for final consideration. Expert panellists were provided with a study document outlining all item definitions, response options, Round 1 and 2 responses (median scores and range) and proposed additional and excluded items (115 pages). JS and CR facilitated the consensus panel, ensuring all panellists had an equal voice to express viewpoints. If consensus was unable to be reached, this was recorded as the proportion of agreement for the relevant item and associated elements. The panel meeting was audio-recorded with panellists’ consent.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V.25. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise respondents’ characteristics and demographic details. For each item outcome, the median, mean and proportion rating were calculated. For ranking scores, the median and IQR for each item outcome was calculated to determine rank.

RESULTS

The flow of Delphi rounds and participants are presented in figure 1. Following electronic distribution to 225 clinicians, Round 1 and 2 surveys had a response rate of 34% and 29%, respectively. In total, 64 participants completed Round 1. Of these, 61 went on to complete Round 2. There were three additional respondents in Round 2 who did not participate in the first survey. Round 2 had an additional three invitees as the survey link was shared between colleagues who wanted to include feedback from a broader pool. Round 3 panellists completed all three Delphi rounds. Table 1 describes the respondent characteristics from Rounds 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Round 1 and 2 respondents

| Variable | Round 1 | Round 2 |

| N=64 | N=64 | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 27 (42) | 25 (39) |

| Female | 37 (58) | 39 (61) |

| Age, n (%) | ||

| 20–29 years | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| 30–39 years | 14 (22) | 11 (17) |

| 40–49 years | 21 (33) | 21 (33) |

| 50–59 years | 17 (27) | 18 (28) |

| ≥60 years | 11 (17) | 13 (20) |

| Country of practice, n (%) | ||

| Africa | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Asia | 6 (9) | 6 (9) |

| Europe | 13 (20) | 13 (20) |

| Middle East | 3 (5) | 3 (5) |

| North America | 12 (19) | 15 (24) |

| Oceania | 22 (34) | 20 (31) |

| South America | 6 (9) | 6 (9) |

| Discipline and specialty, n (%) | ||

| Doctor | 22 (34) | 22 (34) |

| Anaesthesia/ICU | 9 (41) | 7 (32) |

| Surgery | 4 (18) | 5 (23) |

| Paediatrics | 3 (14) | 5 (23) |

| Interventional radiology | 2 (9) | 2 (9) |

| Other | 4 (20) | 3 (15) |

| Nurse | 39 (61) | 38 (60) |

| Vascular access | 8 (21) | 9 (24) |

| Intensive care | 7 (18) | 7 (18) |

| Academia/research | 5 (13) | 5 (13) |

| Oncology/haematology | 5 (13) | 5 (13) |

| Infection prevention and control | 4 (10) | 3 (8) |

| Paediatrics | 3 (8) | 3 (8) |

| Infusion therapy* | 7 (18) | 6 (16) |

| Other | 3 (5) | 4 (6) |

| Formal vascular access qualification, n (%)† | ||

| No | 28 (43) | 25 (38) |

| Yes | 11 (17) | 13 (21) |

| Not applicable | 25 (39) | 26 (41) |

| Patient population | ||

| Adult | 30 (47) | 25 (39) |

| Mixed | 24 (38) | 26 (41) |

| Paediatric/neonate | 10 (16) | 13 (20) |

*Includes home infusion.

†Nurse only, n=39.

ICU, intensive care unit.

The majority of respondents were females (Round 1; 37 of 64, 58%), aged between 30 and 50 years (Round 1; 35 of 64, 55%). Approximately 34% of respondents were physicians from diverse fields including anaesthesia and intensive care (Round 1; 9 of 22, 41%), surgery (4 of 22, 18%) and paediatrics (3 of 22, 14%). The remaining respondents were nurses (~60% Rounds 1 and 2) mainly practising in vascular access (Round 1; 8 of 39, 21%) or other intensive care providers (7 of 39, 18%). Round 3 involved 14 experts from 11 countries with specialities spanning infectious disease, oncology, surgery, paediatrics, neonates, hospitalists and intensive care.

Data items

Table 2 summarises the flow of data items through the Delphi study.

Table 2.

Flow of data items through Delphi rounds

| Initial dataset | Demographic items | Device characteristic items | Insertion items | Management items | Complication/removal items |

| Round 1 | Considered 5 | Considered 5 | Considered 16 | Considered 9 | Considered 17 |

| Included 4 | Included 4 | Included 15 | Included 9 | Included 17 | |

| Excluded 1 | Excluded 1 | Excluded 1 | Added* 4 | Added* 3 | |

| Added* 1 | Added* 1 | Added* 9 | |||

| Round 2 | Considered 5 | Considered 5 | Considered 23 | Considered 13 | Considered 20 |

| Excluded 1 | Excluded 1 | Excluded 8 | Excluded 4 | Excluded 1 | |

| Added 1 | Added 1 | Added 2 | |||

| Round 3 | Considered 5 | Considered 5 | Considered 17 | Considered 9 | Considered 19 |

| Included 5 | Included 5 | Included 16† | Included 9‡ | Included 15† | |

| Dataset | 5 items | 5 items | 16 items | 9 items | 15 items |

Consensus = ≥70% of survey respondents or panellists.

*Additional variables proposed by participants in Round 1.

†Items merged.

‡Flushing variable relabelled to locking solution only.

Round 1 survey results

From the initial 52 items considered, there were high levels of agreement for inclusion of 49 data items, with medians indicating strong agreement (7–9 on the 9-point Likert scale). Three items were excluded based on median importance ratings: patient skin colour (median importance 5, IQR 2–7; range 1–9); catheter lot number (5, IQR 3–7; range 1–9) and level of sedation during device insertion (6, IQR 4–8; range 3–9). Of the remaining 49 items, 36 were rated as feasible to collect and 13 as somewhat feasible to collect (eg, number of attempts or replacement insertion required). There was agreement for minor revisions of 10 item definitions; for example, catheter length was revised to include options for external length measurement, internal length or intravascular length. Response options for 33 items were rated as acceptable, and 20 items achieved consensus for ‘minor revision’. For example, site of insertion was broken into two categories for peripheral intravenous catheters (body site) and central venous catheters (vein). Round 1 respondents proposed 18 additional items for inclusion, including ‘insertion by another facility’.

Round 2 survey results

Of the additional items (n=18) proposed in Round 1, four achieved high levels of agreement for inclusion (patient comorbidities, catheter materials, organism identified and catheter-to-vein ratio). Consistent with Round 1, the three excluded items achieved consensus for exclusion (yes to exclude; 57 respondents, 89%). A top 10 priority list was also achieved and included items such as date and time of insertion, indication, number of attempts and catheter tip position (online supplemental material 2).

bmjqs-2020-011274supp003.pdf (44.3KB, pdf)

Round 3 consensus panel results

In Round 3, 55 items were considered by the expert panel with associated item definitions and response options. Following expert review, the number of items were reduced to 50, with the merging of items, including the complication ‘bloodstream infection’. Round 3 panellists agreed that data on bloodstream infections would be captured under the item ‘primary bloodstream infection’, with response options to capture severity and level of microbiological confirmation. Panellists discussed the addition of branching logic to include data capture of the micro-organism isolated in the blood or catheter tip, however, recognised this may not be feasible for all healthcare facilities.

Minimum dataset

The 3-Round Delphi process resulted in a 50-item MDS which can be grouped into the broad categories of: patient demographics, device characteristics, insertion characteristics, management, complication and removal items (table 3). Demographic items included patient and clinical characteristics such as age, weight and diagnostic group. Device characteristics captured catheter details such as lumen number and catheter material. Insertion characteristics, the largest category with 16 items, included items such as technology used, insertion-related adverse events, and dressing and securement. Items concerning device management included site assessment, complication identified and device use. For complication and removal items, there was agreement that items including thrombosis, catheter-associated skin injury and dislodgement be included; these items comprised 15 of the final 50 included in the MDS.

Table 3.

Vascular access minimum dataset

Patient demographics (n=5)

|

Insertion items (n=16)

|

Management items (n=9)

|

Complication and removal items (n=15)

|

Device characteristics (n=5)

|

Vascular access device nomenclature

Vascular access device nomenclature were developed and consensus achieved for the following devices: PIVC (round 3; 14 of 14, 100%); midline catheter (14 of 14 participants, 100%); peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) (14 of 14 participants, 100%); non-tunnelled central venous catheter (13 of 14 participants, 93%; 1 abstain); tunnelled central venous catheter (14 of 14 participants, 100%); totally implanted venous access device (14 of 14 participants, 100%) and haemodialysis catheter (11 of 12 participants, 92%; 2 abstain). We based the definition of peripheral or central venous catheter on the location of the catheter tip termination. Device nomenclature were intentionally broad as they were developed for global data capture (1).

bmjqs-2020-011274supp001.pdf (47.3KB, pdf)

DISCUSSION

The Delphi study resulted in a 50-item MDS, specifically designed to support the current and ongoing evaluation of vascular access practice and outcomes. Until now, clinicians, researchers and executives have had little-to-no guidance on the clinically relevant and consistent reporting of vascular access-related data.27 28 36 This has consequences when devices fail or complications occur, with healthcare systems having limited opportunity to explore, intervene or set in place remedies to prevent future events. Lack of a standard data capture methodology is a core aspect of this problem. This study achieved its aim to develop an MDS for a vascular access data capture, with accompanying item definitions and response options. To our knowledge, this is the first consensus-based vascular access dataset in development. This fills a gap in the current evidence, providing an initial, pragmatic and specific dataset for international application.

The premise of standardised vascular access data collection is that it enables standardisation of what data elements to capture, process and report for vascular access device use and outcomes across healthcare facilities.37 This study reached some key conclusions regarding what is ‘important vascular access data’ to collect. Data were categorised within the following domains of patient characteristics, device characteristics, insertion characteristics, management characteristics, and complication and removal processes. Following a crowd-sourcing exercise through structured rounds of data collection, accessing the collective wisdom of a panel of international vascular access experts enabled us to develop a vascular access dataset that can be codified and applied by small groups or large health systems. In doing so, we have provided standardised data capture for patient, provider and system level monitoring. Experts in this study agreed the standardisation of a vascular access dataset is important, as it enables the uniform collection, processing and reporting of outcomes across healthcare institutions.38 39 However, panellists agreed that the implementation of standardised vascular access data capture will be challenging, with local hospitals and health services having to take responsibility for the associated costs and supporting infrastructure.

Healthcare professionals specialising in vascular access and quality improvement experts seeking to prevent device complications are generally practising in data poor environments, lacking access to database or registry software and using local, purpose-built data collection tools. This environment impedes clinicians and healthcare facilities’ ability to benchmark performance and identify practice variations over time and limits the reporting ability due to data quality or heterogeneity of items or definitions.27 Our dataset, when implemented with registry or database software, will aid quality monitoring, facilitate benchmarking with national uptake and support national, mandatory reporting requirements (eg, bloodstream infection or deep vein thrombosis (DVT)). Innovations in electronic medical records and clinical quality registries have seen a shift in organisations’ abilities to monitor safety and quality of care. Should the elements recommended by the panel be deployed within health systems, evaluation of the impact of interventions using routine healthcare data40 is possible. In fact, organisations are doing just that, with standardised datasets using registry software currently used for specific devices,41 specialties42 or with a specific focus (eg, infection).12 43 In the USA, the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) Consortium established the HMS PICC Registry to facilitate better data sharing, with an overall aim of improving patient safety and healthcare quality. Since its inception, the HMS PICC Registry has been used extensively to identify practice variation and reduce patient harm.22 44 The registry now routinely tracks BSI and DVT incidence rates, reporting practice variation across 52 sites.31 In the southern hemisphere, the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society CORE registry abstracts data from 202 intensive care units (ICUs) capturing over 90% of national ICU admissions.11 A mature registry, the CORE group provides contributing ICUs with comparative benchmarking reports (risk adjusted) for government reporting purposes and supports researchers and quality and education programmes across Australia and New Zealand. A recent economic evaluation showed the ANZICS CORE registry to have a 4:1 benefit to cost ratio, with 80% national coverage and an estimated AUD 26 million cost benefit, measured through reduction in ICU mortality and average length of stay (over 14 years).45

We have defined a consensus recommendation for a vascular access MDS and associated elements; this could be operationalised using clinical registry software that could, in time, provide similar gains in terms of value-based healthcare through the provision of higher quality data capture to guide clinical practice, improve patient-centred outcomes and cost-effective healthcare delivery. The benefits of a vascular access dataset employed as a registry may be vast for both patients and healthcare systems. However, registries need substantial time to mature, and the first step in registry conceptualisation is the development of an MDS.46

This study did not address the scope or infrastructure considerations of progressing a dataset to a registry system; however, expert panellists agreed this was a valuable next step. As such, it is important to note the limitations of the study. Broad device nomenclature was developed for the purpose of the registry; further work is needed to guide clinical practice and guideline development. While Round 1 response rates were low, this is comparable with other Delphi studies9 and reflects our aim to contact as many multidisciplinary experts as possible. Survey response rates may have increased by shortening the first survey and sending email notifications prior to survey distribution of the upcoming survey release date. Further, consumer voices were not included in this study, but a separate survey is being undertaken to evaluate consumer-rated item importance. The dataset, currently only available in the English language, has not been validated, and the resource and capital costs to implement and sustain the dataset remain unknown. Infrastructure to support this dataset will vary across sites and settings. Despite these limitations, our study has numerous strengths including the geographical breadth and multidisciplinary diversity of study participants and the 3-Round Delphi methods, which aimed to provide equal voice to all respondents.

Conclusion

This study has produced international expert consensus-based recommendations for a vascular access MDS. This is the first time this has been conducted. The vascular access dataset can now be used by healthcare facilities and clinicians to monitor performance, benchmark outcomes, and further develop vascular access practices. More research is required to maximise the learning from data capture through a standardised vascular access dataset.

Footnotes

Twitter: @a_ullman

Correction notice: The article has been corrected since it was published online first. The co-author Carole Hallam's last name was mispelled as Hallum which has been amended.

Contributors: JS, CR, TK, AJU, NM and GR-B shared study conceptualisation and design. All authors contributed to data collection and analysis. JS, TK and RP drafted the initial manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by an unrestricted education grant from Becton, Dickinson and Company (Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) and Menzies Health Institute, Queensland (Griffith University). The funders have had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: JS has received grant funding from Griffith University, Children’s Hospital Foundation and investigator-initiated research and educational grants provided to Griffith University by vascular access product manufacturers (Becton Dickinson), unrelated to this project. TK has received grant funding from Children’s Hospital Foundation, Griffith University, National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Emergency Medicine Foundation and investigator-initiated research grants and speaker fees provided to Griffith University from vascular access product manufacturers 3M Medical, Access Scientific, Angiodynamics, BD-Bard, Baxter, Cardinal Health, Medical Specialties Australia, Vygon. VC has received grants from the National Institute of Health, Agency for Healthcare Research Quality, Centers for Disease Control, American Heart Association and Blue Cross/Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan. VC has also received royalties from Oxford University Press and Wolters Kluwers related to book titles. MC has received grant funding from Griffith University, Children’s Hospital Foundation, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Foundation, Cancer Council Queensland, Australasian College for Infection Prevention and Control, and investigator-initiated research and educational grants and speaker fees provided to Griffith University by vascular access product manufacturers (Baxter, Becton Dickinson, Entrotech Life Sciences), unrelated to this project. AJU reports fellowships and grants by the NHMRC, employment by Griffith University, grants by the Children’s Hospital Foundation, the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Foundation, Emergency Medicine Foundation and the Australian College of Critical Care Nursing, and investigator-initiated research grants and speaker fees provided to Griffith University from 3M, Cardinal Health and Becton Dickinson. NM’s employer has received the following on her behalf from manufacturers investigator-initiated research grants and unrestricted educational grants from 3M, Adhezion, BD, Centurion, Medical Products, Cook Medical, Entrotech and Teleflex. GR-B has received research grant funding from Griffith University and the Australian College of Infection Prevention and Control. Griffith University has received on her behalf: unrestricted research grants from 3M, B-Braun and Becton Dickinson; and consultancy payments from Ausmed, 3M, Becton Dickinson, ResQDevices, Medline and Wolters Kluwer unrelated to this project. ID has received an educational grant from Pfizer unrelated to this project. MLGP has received research grant funding from National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq, Brazil. SB reports consultancy agreement with BD, B-Braun, BMR Brazil and speaker fees from Baxter unrelated to this project. OM reports receiving research grant funding from 3M and Becton Dickinson; and consultancy payments from 3M and Becton Dickinson unrelated to this project. MD is part of the Speaker’s Bureau with Access Scientific, Becton Dickinson, Eloquest, Ethicon and Teleflex. She has received grant funding for her organisation from Johnson and Johnson unrelated to this project. CR reports investigator-initiated research grants and speaker fees provided to Griffith University from vascular access product manufacturers (3M, Angiodynamics; Baxter; B-Braun; BD-Bard; Medtronic; ResQDevices; Smiths Medical), unrelated to this project.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. The MDS is published with the manuscript. For additional information, please contact the primary investigator at j.schults@griffith.edu.au.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from Griffith University, Australia (2019/275).

References

- 1.Rahman AN, Applebaum RA. The nursing home Minimum Data Set assessment instrument: manifest functions and unintended consequences--past, present, and future. Gerontologist 2009;49:727–35. 10.1093/geront/gnp066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolton D. Improving peripheral cannulation practice at an NHS trust. Br J Nurs 2010;19:1346–50. 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.21.79998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsh N, Webster J, Larson E, et al. Observational study of peripheral intravenous catheter outcomes in adult hospitalized patients: a multivariable analysis of peripheral intravenous catheter failure. J Hosp Med 2018;13:83–9. 10.12788/jhm.2867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ullman AJ, Marsh N, Mihala G, et al. Complications of central venous access devices: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2015;136:e1331–44. 10.1542/peds.2015-1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takashima M, Schults J, Mihala G, et al. Complication and failures of central vascular access device in adult critical care settings. Crit Care Med 2018;46:1998–2009. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan RJ, Northfield S, Larsen E, et al. Central venous access device SeCurement and dressing effectiveness for peripherally inserted central catheters in adult acute hospital patients (cascade): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:458. 10.1186/s13063-017-2207-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuffaha HW, Marsh N, Byrnes J, et al. Cost of vascular access devices in public hospitals in Queensland. Aust Health Rev 2018. 10.1071/AH18102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grover FL, Shahian DM, Clark RE, et al. The STS national database. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:S48–54. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell A-M, Burns EM, Hull L, et al. International recommendations for national patient safety incident reporting systems: an expert Delphi consensus-building process. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:150–63. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is human: building a safer health system. Washington (DC: Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care, National Academies Press, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ANZICS CORE . Centre for outcome and resource evaluation 2018 report. Victoria, Australia: Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society, Centre for Outcome and Resource Evaluation, 2018: p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.ANZICS . ANZICS core CLABSI registry: ANZICS core, 2019. Available: https://www.anzics.com.au/clabsi/ [Accessed 23 Sep 2019].

- 13.Stewart JM. Abstraction techniques for the STS national database. J Extra Corpor Technol 2016;48:201–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor RM, Feltbower RG, Aslam N, et al. Modified international e-Delphi survey to define healthcare professional competencies for working with teenagers and young adults with cancer. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011361. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone E, Rankin N, Phillips J, et al. Consensus minimum data set for lung cancer multidisciplinary teams: results of a Delphi process. Respirology 2018;23:927–34. 10.1111/resp.13307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donohoe H, Stellefson M, Tennant B. Advantages and limitations of the e-Delphi technique. Am J Health Educ 2012;43:38–46. 10.1080/19325037.2012.10599216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, et al. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health 1984;74:979–83. 10.2105/AJPH.74.9.979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evangelidis N, Tong A, Manns B, et al. Developing a set of core outcomes for trials in hemodialysis: an international Delphi survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2017;70:464–75. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci 2015;10:21. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davey CJ, Slade SV, Shickle D. A proposed minimum data set for international primary care optometry: a modified Delphi study. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2017;37:428–39. 10.1111/opo.12372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan appropriateness guide for intravenous catheters (magic): results from a Multispecialty panel using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:S1–40. 10.7326/M15-0744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user's manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. Grade Handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Standardised outcomes in nephrology - Haemodialysis (SONG-HD): study protocol for establishing a core outcome set in haemodialysis. Trials 2015;16:364. 10.1186/s13063-015-0895-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone E, Rankin N, Phillips J, et al. Consensus minimum data set for lung cancer multidisciplinary teams: results of a Delphi process. Respirology 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schults JA, Rickard CM, Kleidon T, et al. Building a global, pediatric vascular access registry: a scoping review of trial outcomes and quality indicators to inform evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2019;16:51–9. 10.1111/wvn.12339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schults JA, Woods C, Cooke M, et al. Healthcare practitioner perspectives and experiences regarding vascular access device data: an exploratory study. Int J Healthc Manag 2020;18:1–8. 10.1080/20479700.2020.1721750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexandrou E, Ray-Barruel G, Carr PJ, et al. Use of short peripheral intravenous catheters: characteristics, management, and outcomes worldwide. J Hosp Med 2018;13. 10.12788/jhm.3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takashima M, Ray-Barruel G, Ullman A, et al. Randomized controlled trials in central vascular access devices: a scoping review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michigan Hospital Meidicine Safety Consortium . Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) use initiative. HMS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleidon TM, Rickard CM, Schults JA, et al. Development of a paediatric central venous access device database: a retrospective cohort study of practice evolution and risk factors for device failure. J Paediatr Child Health 2020;56:289–97. 10.1111/jpc.14600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Infusion Nurses Society . Infusion therapy standards of practice. J Infus Nurs 2016;39. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap Consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baskin KM, Durack JC, Abu-Elmagd K, et al. Chronic central venous access: from research consensus panel to national Multistakeholder initiative. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018;29:461–9. 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lippeveld T, Saurerborn R, Bodart C. Design and implementation of health information systems. Geneva: United Nations, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Girgenti C, Moureau NL. The need for comparative data in vascular access: the rationale and design of the PICC registry. Journal of the Association for Vascular Access 2013;18:219–24. 10.1016/j.java.2013.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed TL, Drozda JP, Baskin KM, et al. Advancing medical device innovation through collaboration and coordination of structured data capture pilots: report from the medical device epidemiology network (MDEpiNet) specific, measurable, achievable, Results-Oriented, time bound (smart) think tank. Healthc 2017;5:158–64. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke GM, Conti S, Wolters AT, et al. Evaluating the impact of healthcare interventions using routine data. BMJ 2019;365:l2239. 10.1136/bmj.l2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherline C. CVAD registry Chicago: CVAD registry, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jemcov T, Dimkovic N. Vascular access registry of Serbia: a 4-year experience. Int Urol Nephrol 2017;49:319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.INICC . International nosocomial infection control Consortium INICC, 2013. Available: http://www.inicc.org/ [Accessed 23 Sep 2019].

- 44.Chopra V, Kaatz S, Conlon A, et al. The Michigan risk score to predict peripherally inserted central catheter-associated thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 2017;15:1951–62. 10.1111/jth.13794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . Economic evaluation of clinical quality registries: final report. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . Operating principles and technical standards for Australian clinical quality registries. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjqs-2020-011274supp002.pdf (36.7KB, pdf)

bmjqs-2020-011274supp003.pdf (44.3KB, pdf)

bmjqs-2020-011274supp001.pdf (47.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. The MDS is published with the manuscript. For additional information, please contact the primary investigator at j.schults@griffith.edu.au.