Summary

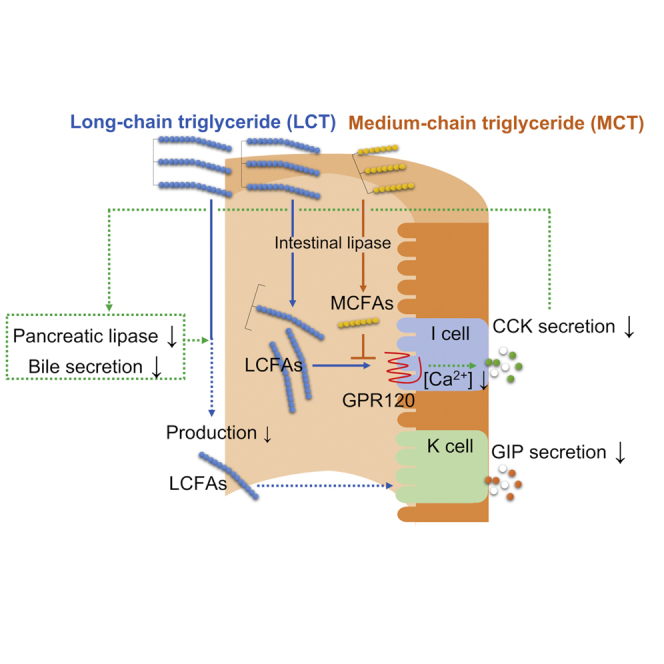

Long-chain triglycerides (LCTs) intake strongly stimulates GIP secretion from enteroendocrine K cells and induces obesity and insulin resistance partly due to GIP hypersecretion. In this study, we found that medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) inhibit GIP secretion after single LCT ingestion and clarified the mechanism underlying MCT-induced inhibition of GIP secretion. MCTs reduced the CCK effect after single LCT ingestion in wild-type (WT) mice, and a CCK agonist completely reversed MCT-induced inhibition of GIP secretion. In vitro studies showed that medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) inhibit long-chain fatty acid (LCFA)-stimulated CCK secretion and increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations through inhibition of GPR120 signaling. Long-term administration of MCTs reduced obesity and insulin resistance in high-LCT diet-fed WT mice, but not in high-LCT diet-fed GIP-knockout mice. Thus, MCT-induced inhibition of GIP hypersecretion reduces obesity and insulin resistance under high-LCT diet feeding condition.

Keywords: Biological sciences, Physiology, Endocrinology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

MCTs inhibit LCT-induced GIP secretion by reducing LCT-induced CCK action

-

•

MCFAs derived from MCTs are expected to have antagonistic properties to GPR120

-

•

Inhibition of GIP secretion alleviates obesity under high-LCT diet feeding condition

Biological sciences; Physiology; Endocrinology

Introduction

The number of obese people continues to increase worldwide (Ng et al., 2014). Obesity is the overaccumulation of fat in the body and is partly caused by high fat intake (Bray et al., 2004). Ingestible fats are predominantly long-chain triglycerides (LCTs). Ingestion of LCTs, which have higher energy values than proteins or sugars, results in overaccumulation of fat in the body (Bray and Popkin, 1998). Fat overaccumulation induces insulin resistance due to increased inflammatory cytokine levels (Xu et al., 2003) and hepatic steatosis due to increased lipogenic gene expression in the liver (Inoue et al., 2005), thus increasing the risks of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, arteriosclerotic disease, and cancer (Petrie et al., 2018). Hence, to prevent the onset and progression of lifestyle-related diseases, the significant problem of obesity increase needs to be addressed.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide/gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) are gut hormones (incretins) that are secreted in response to nutrient ingestion to promote glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells (Kieffer, 2004; Ogata et al., 2014; Preitner et al., 2004; Seino and Yabe, 2013). GLP-1, which is secreted from enteroendocrine L cells of the small and large intestine, suppresses appetite to reduce body weight (Flint et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2018). GIP is secreted from enteroendocrine K cells of the upper small intestine (Iwasaki et al., 2015). LCT ingestion strongly induces GIP secretion, and GIP hypersecretion contributes to the development of obesity and insulin resistance (Harada et al., 2008, 2011; Joo et al., 2017; Shimazu-Kuwahara et al., 2017; Yamane and Harada, 2019). In contrast, studies using GIP-overexpressing mice or GIP agonist have shown that pharmacological activation of GIP signaling is beneficial for suppression of body weight gain and insulin resistance (Kim et al., 2012; Mroz et al., 2019). These reports suggest that there is a big difference in the effect of GIP on obesity and insulin resistance between physiological GIP concentration and pharmacological GIP concentration. Studies using GIP antagonist, GIP antibody, or GIP receptor-knockout mice have shown that inhibition of GIP signaling alleviates body weight gain and insulin resistance under high-LCT diet feeding condition (Boylan et al., 2015; McClean et al., 2007; Miyawaki et al., 2002). We generated GIP-knockout (GIP KO) mice and reported that inhibition of GIP secretion results in reduced body weight gain and insulin resistance under high-LCT diet feeding condition (Nasteska et al., 2014), indicating that inhibition of not only GIP signaling but also GIP secretion is effective in reducing obesity and insulin resistance under high-LCT diet feeding condition.

Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) are orally ingestible fats and consist of medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) having 6 to 12 carbon chains and glycerol (Babayan, 1968). While MCTs and LCTs have equivalent energy, a meta-analysis in humans revealed that ingestion of MCTs induces less body weight gain than ingestion of LCTs (Mumme and Stonehouse, 2015). Known mechanisms underlying alleviation of obesity by MCT are changes in the intestinal flora (Zhou et al., 2017), increased expression of PPARγ and adiponectin genes in adipose tissues (Takeuchi et al., 2006), increased β-oxidation in the liver (Bach and Babayan, 1982), activation of brown adipocytes (Zhang et al., 2015), and increased energy expenditure (St-Onge et al., 2003). We previously showed that a single ingestion of MCT oil stimulated GLP-1 secretion, but not GIP secretion (Murata et al., 2019). It was also shown that long-term consumption of MCT diet did not induce GIP hypersecretion and induced less body weight gain and insulin resistance than that of LCT diet. In the present study, we found that MCT oil inhibited GIP secretion after a single LCT oil ingestion. We also clarified the mechanism underlying MCT-induced inhibition of LCT-stimulated GIP secretion. In addition, we demonstrated that MCTs reduce body weight gain and insulin resistance during long-term consumption of high-LCT diet by inhibition of GIP secretion.

Results

MCT oil inhibits LCT oil-induced GIP secretion

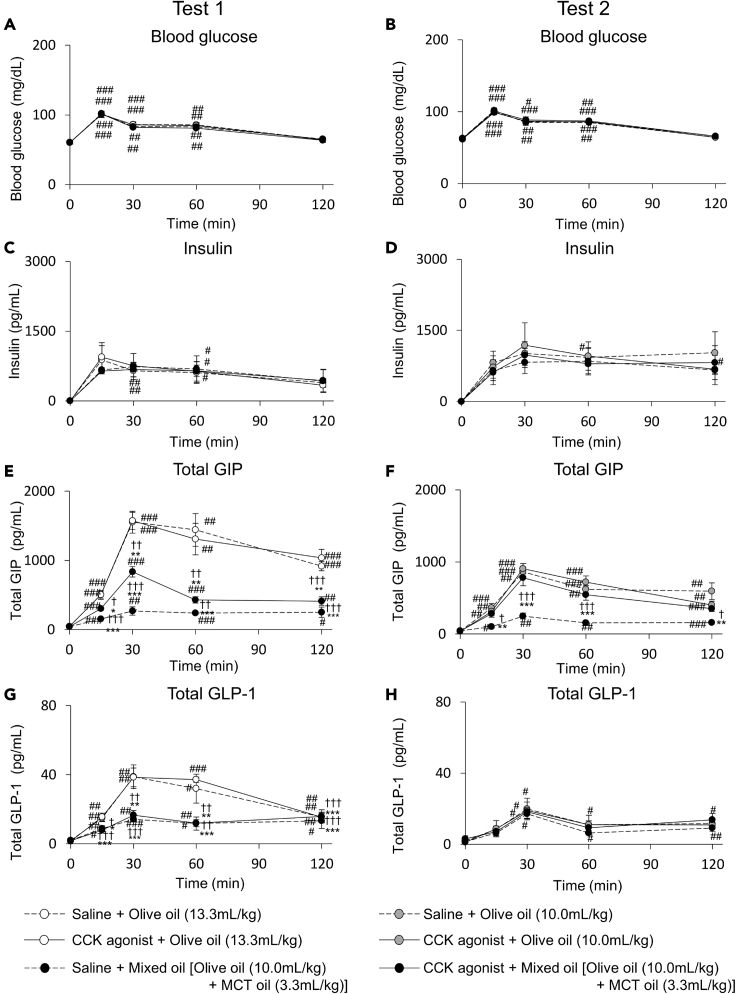

In the saline treatment group of Test 1, in which the same dose of oil was orally administered, the blood glucose and insulin concentrations were not significantly different between the olive oil group and the mixed oil group (olive oil and MCT oil) (Figures 1A and 1C). The total GIP concentration was significantly lower in the mixed oil group compared with that in the olive oil group (Figure 1E). The total GLP-1 concentration was significantly lower at 15, 30, and 60 min in the mixed oil group compared with that in the olive oil group (Figure 1G).

Figure 1.

Blood glucose, insulin, total GIP and total GLP-1 concentration during oral oil tolerance tests with saline or CCK agonist treatment

Blood glucose (A and B), insulin (C and D), total GIP (E and F), and total GLP-1 (G and H) concentration during oral oil tolerance tests 1 (A, C, E, and G) and 2 (B, D, F, and H) in 13-week-old male WT mice (n = 6 mice in each group). Test 1 is a tolerance test in which the same dose of oil is orally administered and Test 2 is a tolerance test in which the same dose of olive oil is orally administered. White circles indicate olive oil (13.3 mL/kg body weight). Gray circles indicate olive oil (10 mL/kg body weight). Black circles indicate mixed oil. Dot line and solid line indicate saline (control) and CCK agonist treatment group, respectively. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test using SPSS statistics. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. 0 min. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. Saline + Olive oil.†P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01, †††P < 0.001 vs. CCK agonist + Olive oil.

LCTs, including olive oil, increase GLP-1 and GIP secretion in a dose-dependent manner (Murata et al., 2019). Therefore, an oral oil tolerance test was performed as the saline treatment group of Test 2, in which the same dose of olive oil was orally administered to each group and MCT oil was added in the mixed oil group (Figures 1B, 1D, 1F, and 1H). The blood glucose and insulin concentrations were similar between the mixed oil group and the olive oil group (Figures 1B and 1D). The total GIP concentration was significantly suppressed at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min by adding MCT oil to LCT oil (Figure 1F). The total GLP-1 concentration did not differ between the olive oil group and the mixed oil group (Figure 1H). These results indicated that oral supplementation of MCT inhibits GIP secretion but not GLP-1 secretion after ingestion of LCT.

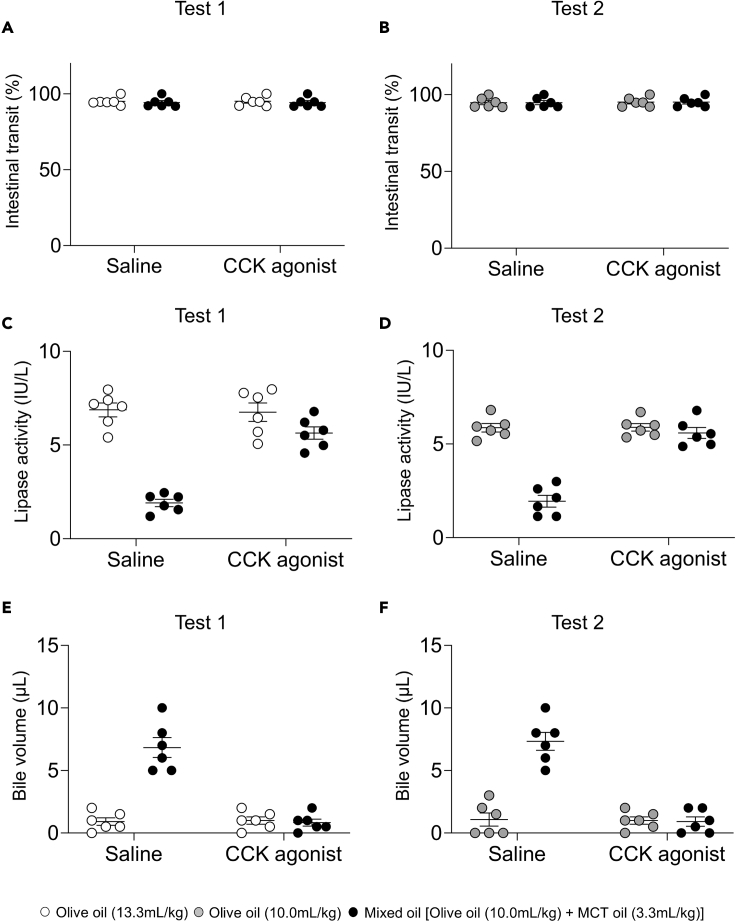

MCT oil inhibits GIP secretion by reducing LCT oil-induced effects of CCK

Pancreatic lipase and bile are essential for digestion and absorption of LCTs (Pilichiewicz et al., 2003). While inhibition of lipase results in reduced postprandial incretin secretion, GIP secretion is not induced after fat ingestion without bile secretion (Sankoda et al., 2017; Shibue et al., 2015). Since these findings show that digestion and absorption of fat affects incretin secretion, we measured intestinal transit, lipase activity in the small intestine, and gallbladder contraction after administration of olive oil or mixed oil. In the saline treatment group of tests 1 and 2, intestinal transit did not differ significantly between the mixed oil group and the olive oil group (Figures 2A and 2B). The lipase activity in the small intestine was significantly lower in the mixed oil group compared with that in the olive oil group (Figures 2C and 2D). The remaining bile volume in the gallbladder was significantly greater in the mixed oil group compared with that in the olive oil group (Figures 2E and 2F). These results showed that MCT oil inhibits olive oil-induced lipase activity and gallbladder contraction.

Figure 2.

Effects of MCT oil on CCK action in oral olive oil tolerance tests with or without CCK agonist treatment

(A–C)(A) Intestinal transit, (B) lipase activity in the intestinal contents, and (C) remaining bile volume in the gallbladder at 30 min after loading in Test 1 and Test 2 in 15- to 17-week-old male WT mice (n = 6 mice in each group).

(D and E)(D) Lipase activity in the intestinal contents, and (E) remaining bile volume in the gallbladder. White circles indicate olive oil (13.3 mL/kg body weight). Gray circles indicate olive oil (10 mL/kg body weight) (n = 6 mice in each group). Black circles indicate mixed oil. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test using SPSS statistics. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. olive oil group. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. saline treatment.

The gut hormone cholecystokinin (CCK) promotes pancreatic lipase secretion and contracts the gallbladder (Conwell et al., 2002; Liddle et al., 1985). We therefore performed an oral oil tolerance test after treatment of a CCK agonist. The CCK agonist did not affect intestinal transit after oral administration of mixed oil group or the olive oil (Figures 2A and 2B). The CCK agonist completely restored lipase activity and gallbladder contraction in the mixed oil group (Figures 2C–2F). The CCK agonist did not affect blood glucose, insulin, GIP, and GLP-1 concentration in the olive oil group and blood glucose, insulin, and GLP-1 concentration in the mixed oil group (Figure 1). In the mixed oil group, GIP concentration after CCK agonist treatment was significantly higher than that after saline treatment in test 1 and test 2 (Figures 1E and 1F). Because the amount of olive oil in the olive oil group was larger in test 1 (olive oil 13.3 mL/kg body weight [BW]) than that in test 2 (olive oil 10.0 mL/kg BW), the CCK agonist restored GIP secretion in the mixed oil group (olive oil 10.0mL/kg BW + MCT oil 3.3mL/kg BW) to the level in the olive oil group in test 2 but not in test 1.

We measured lipase activity in the small intestine, bile volume, and plasma GIP concentrations at 30 min after MCT administration treated with or without CCK agonist (Figure S1). CCK agonist increased lipase activity and reduced the remaining bile volume in gallbladder in the saline (control) and the MCT groups (Figures S1A and S1B). MCT oil and saline did not induce GIP secretion. In addition, MCT did not increase GIP secretion in the presence of CCK agonist (Figure S1C). These findings indicated that MCT does not induce GIP secretion with or without CCK agonist.

Next, we performed oral olive oil tolerance test with or without CCK antagonist administration in WT mice (Figure S2). Total GLP-1 concentration after oil administration was not different between CCK antagonist-treated mice and control mice. In contrast, total GIP concentration was lower in CCK antagonist-treated mice than that in control mice. These findings suggested that inhibition of CCK signaling by CCK antagonist reduces LCT-induced GIP secretion.

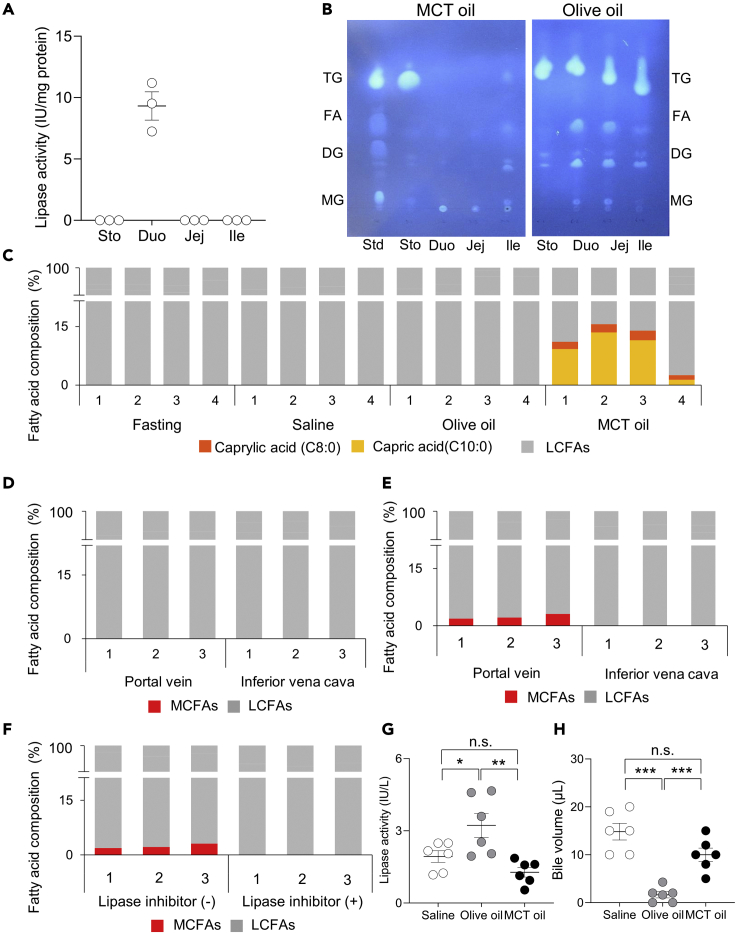

MCT oil is digested to MCFAs by lipase in the small intestine and transported to the portal vein (PV)

Digestion and absorption of MCTs in the intestine differ from those of LCTs. It is known that ingested MCTs are digested to MCFAs by gastric lipase and transported from the stomach to the PV (Cohen et al., 1971; Faber et al., 1988; Isaacs et al., 1987). However, studies in rats have shown that MCTs are digested by pancreatic lipase and bile in the small intestine and transported to the PV (Douglas et al., 1990; Greenberger et al., 1966). We assessed the process of digestion and absorption of MCTs in WT mice to clarify the mechanism underlying MCT oil-induced inhibition of GIP secretion through reduction of LCT-induced effects of CCK.

In the stomach and small intestine of mice under fasting condition, lipase activity was detected only in the duodenum (Figure 3A). After olive oil ingestion, triglycerides (TGs), diglycerides (DGs), monoglycerides (MGs), and fatty acids (FAs) were detected in the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, and only TGs were detected in the stomach (Figure 3B). After MCT ingestion, on the other hand, TGs were detected in the stomach, but no lipids were detected in the duodenum, jejunum, or ileum. In the assessment of fatty acid composition in the PV in the fasted state and at 30 min after oral loading of saline, olive oil, or MCT oil, the MCFAs caprylic acid and capric acid were detected only in the MCT oil group (Figure 3C). These findings indicated that orally ingested MCTs are rapidly absorbed in the stomach or intestine and transported to the PV.

Figure 3.

Digestion and absorption of MCT oil in gastrointestinal tract

(A) Intestinal lipase activity in fasted 15-week-old male WT mice (n = 3 mice). Sto, Duo, Jej, and Ile indicate the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, respectively. Data indicate the mean ± SEM.

(B) Lipid analysis of intestinal contents by thin-layer chromatography at 30 min after loading of olive oil or MCT oil in 15-week-old male WT mice. Std indicates standard lipid. Sto, Duo, Jej, and Ile indicate the contents in the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, respectively. TG, FA, DG, and MG indicate triglyceride, fatty acid, diglyceride, and monoglyceride, respectively. The test was performed three times, and representative data from each of them are presented.

(C) Plasma fatty acid composition in portal vein (PV) in the fasted state and at 30 min after ingestion of saline, olive oil, or MCT oil (n = 4 mice). Orange bars, yellow bars, and gray bars indicate caprylic acid (C8:0), capric acid (C10:0), and LCFAs, respectively. PV plasma samples from all mice are presented, and 1 to 4 indicate the sample numbers.

(D) Plasma fatty acid composition in PV and inferior vena cava (IVC) at 30 min after infusion of MCT oil into the stomach following stomach ligation (n = 3 mice).

(E and F) Plasma fatty acid composition in PV and inferior vena cava (IVC) at 30 min after infusion of MCT oil or MCT oil + lipase inhibitor into the intestine following intestine ligation (n = 3 mice). Red bars indicate medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs), and gray bars indicate long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs). Plasma samples from all mice are presented, and 1 to 3 indicate the sample numbers.

(G and H)(G) Intestinal lipase activity and (H) remaining bile volume in the gallbladder at 30 min after ingestion of saline, olive oil, or MCT oil (n = 6 mice). White circles, gray circles, and black circles indicate saline, olive oil, and MCT oil, respectively. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test using SPSS statistics. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. n.s. no significance.

The gastrointestinal tract was ligated at the gastroesophageal junction and the pyloric ring in some mice (stomach-ligated mice), and at the pyloric ring and the distal end of the third part of the duodenum in other mice (duodenum-ligated mice) to identify the precise site of MCT oil absorption. After direct administration of MCT oil into the stomach of stomach-ligated mice, no MCFAs were detected in the PV or inferior vena cava (IVC) (Figure 3D). After direct administration of MCT oil into the duodenum of duodenum-ligated mice; on the other hand, MCFAs were detected in the PV, but no MCFAs were detected in the IVC (Figure 3E). Given lipase activity in the duodenum, as shown in Figure 3A, the PV was examined for fatty acids after coadministration of lipase inhibitor orlistat and MCTs into the duodenum of duodenum-ligated mice, revealing that MCFAs were eliminated (Figure 3F). Collectively, these findings indicated that MCTs are digested to MCFAs by lipase and absorbed in the duodenum.

Olive oil increased lipase activity in the small intestine (Figure 3G) and reduced remaining bile volume in the gallbladder (Figure 3H). Lipase activity and gallbladder volume did not differ between saline groups and MCTs groups. After oral administration of MCTs, on the other hand, lipase activity and the remaining bile volume in the gallbladder were similar to those seen with saline. These results suggested that MCTs do not induce the effects of CCK including stimulation of pancreatic exocrine secretion and gallbladder contraction.

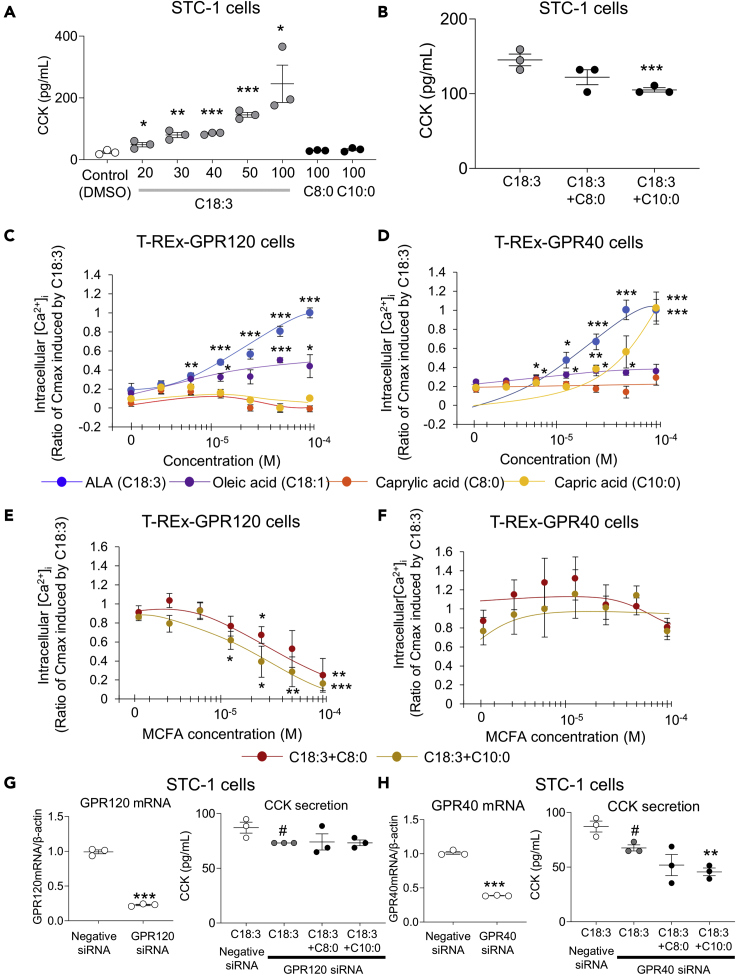

MCFAs inhibit LCFA-induced intracellular calcium ion concentrations ([Ca2+]i) and CCK secretion through GPR120

It was shown that MCTs inhibit LCT-induced GIP secretion by reducing the effects of CCK, and MCTs are digested to MCFAs by lipase in the duodenum and rapidly absorbed. These findings suggest that the digested MCFAs may inhibit CCK secretion from enteroendocrine I cells. We measured plasma CCK concentration in the PV at 30 min after oral ingestion of olive oil or mixed oil. However, as available antibody in the EIA kit for measuring CCK is cross-reactive with mouse gastrin, the CCK concentration did not differ significantly between the olive oil group and the mixed oil group of mice (data not shown). Therefore, the murine intestinal cell line STC-1 was used to assess the effect of MCFAs on CCK secretion. It has been reported that STC-1 cells do not secrete gastrin (Kuhre et al., 2016). ALA (C18:3) induced CCK secretion from STC-1 cells in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas neither caprylic acid (C8:0) nor capric acid (C10:0) at high concentrations induced CCK secretion (Figure 4A). In the presence of 50 μM ALA, 100 μM capric acid significantly inhibited CCK secretion (Figure 4B). On the other hand, 100 μM caprylic acid did not inhibit CCK secretion.

Figure 4.

Effects of medium-chain fatty acids on long-chain fatty acid-induced CCK secretion and increase in [Ca2+]i through GPR120 and GPR40

(A) CCK concentration in STC-1 cell supernatant after addition of control (DMSO, 0.1%), C18:3 (20-100μM), C8:0 (100μM) and C10:0 (100μM). White circles and gray circles indicate control and C18:3, respectively. The black circles indicate C8:0 and C10:0. The experiment was performed in triplicate twice, and representative data are presented. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test using SPSS statistics. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control.

(B) CCK concentration in STC-1 cell supernatant after addition of C18:3 (50 μM), C18:3 (50 μM) + C8:0 (100 μM), and C18:3 (50 μM) + C10:0 (100 μM). Gray circles indicate C18:3, and black circles indicate C18:3 + C8:0 and C18:3 + C10:0. The experiment was performed in triplicate twice, and representative data are presented. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test using SPSS statistics. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. C18:3.

(C and D) Relative [Ca2+]I in T-REx GPR120 cells and T-REx GPR40 cells after addition of C18:3, C18:1, C8:0, or C10:0. Blue circles, purple circles, orange circles, and yellow circles indicate C18:3, C18:1, C8:0, and C10:0, respectively. The experiment was performed in duplicate four times, and representative data are presented. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test using SPSS statistics. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. after 1.56 × 10−6 M each fatty acid loading.

(E and F) Relative [Ca2+]i in T-REx GPR120 cells and T-REx GPR40 cells after addition of C18:3 (100 μM) + C8:0 or C10:0. Red circles indicate C18:3 + C8:0, and yellow circles indicate C18:3 + C10:0. The experiment was performed in duplicate four times, and representative data are presented. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test using SPSS statistics. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. C18:3 (100 μM) alone.

(G) (Left) GPR120 mRNA expression in STC-1 cells after GPR120 knockdown. The experiment was performed in triplicate twice, and representative data are presented. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s t-test. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. negative siRNA. (Right) CCK concentration in STC-1 cell supernatant at 1 hr after each fatty acid loading following GPR120 knockdown. The experiment was performed in triplicate twice, and representative data are presented. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test using SPSS statistics. #P < 0.05 vs negative siRNA.

(H) (Left) GPR40 mRNA expression in STC-1 cells after GPR40 knockdown. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. The experiment was performed in triplicate twice, and representative data are presented. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s t-test. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control. (Right) CCK concentration in STC-1 cell supernatant at 1 hr after each fatty acid loading following GPR40 knockdown. The experiment was performed in triplicate twice, and representative data are presented. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test using SPSS statistics. #P < 0.05 vs negative siRNA. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. C18:3 GPR40 siRNA.

G protein-coupled receptor 120 (GPR120)/free fatty acid receptor 4 (FFAR4) and G protein-coupled receptor 40 (GPR40)/free fatty acid receptor 1 (FFAR1) are identified as receptors whose ligands are fatty acids (Briscoe et al., 2003; Hirasawa et al., 2005). Both receptors are coupled with Gq proteins (Hara et al., 2011; Hauge et al., 2015). In vitro studies using GPR120-expressing HEK293 cells and GPR40-expressing CHO cells showed that LCFAs, but not MCFAs, activated the two receptors (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Itoh et al., 2003). However, there are no reports of studies assessing the effects of both LCFAs and MCFAs on the receptor activity in the same cell line expressing GPR120 and GPR40. Therefore, we assessed intracellular calcium ion concentration ([Ca2+]i) in T-REx GPR120 cells and T-REx GPR40 cells after fatty acid loading. After ALA or oleic acid loading,[Ca2+]i were increased in a concentration-dependent manner in T-REx GPR120 and T-REx GPR40 cells (Figures 4C and 4D). The response was greater with ALA than that with oleic acid. Caprylic acid did not increase [Ca2+]i in T-REx GPR120 or T-REx GPR40 cells. Capric acid did not increase [Ca2+]i in T-REx GPR120 cells, but it did in T-REx GPR40 cells at a concentration of 100 μM. Subsequently, the effects of MCFAs on [Ca2+]i were assessed in the presence of 100 μM ALA. In T-REx GPR120 cells, capric acid and caprylic acid significantly suppressed ALA-induced increase in [Ca2+]i (Figure 4E). The EC50 values of caprylic acid and capric acid were 3.3 × 10−5 M and 2.0 × 10−5 M, respectively. In T-REx GPR40 cells, on the other hand, neither caprylic acid nor capric acid suppressed ALA-induced increase in [Ca2+]i (Figure 4F). These findings indicated that MCFAs have no effect on GPR40-mediated, LCFA-induced [Ca2+]i, but significantly decrease GPR120-mediated, LCFA-induced [Ca2+]i.

To determine the involvement of GPR120 or GPR40 in MCFA-induced reduction in CCK secretion, GPR120-knockdown STC-1 cells (78% reduction in GPR120 expression compared with control cells) and GPR40-knockdown STC-1 cells (60% reduction in GPR40 expression compared with control cells) were used (Figures 4G and 4H). In GPR120-knockdown cells, 50 μM ALA-induced CCK secretion was significantly reduced compared with control cells (Figure 4G). In GPR120-knockdown cells, 100 μM MCFA-induced reduction in CCK secretion was not observed. In GPR40-knockdown cells, 50 μM ALA-induced CCK secretion was significantly reduced compared with control cells (Figure 4H). In GPR40-knockdown cells, 100 μM MCFA-induced reduction in CCK secretion was observed. These results indicated that MCFAs inhibit LCFA-induced CCK secretion through inhibition of GPR120 signaling.

A docking simulation of fatty acids was carried out together with NCG21, known as a selective agonist for GPR120, and AH-7614, known as a selective antagonist for GPR120. In docking simulation analyses of target receptor, hydrogen bonding energies of active form and inactive form in response to ligands are measured. Hydrogen bonding energies of these compounds docked into the GPR120 models are shown in Table 1. Agonistic or antagonistic effect of the ligand on target receptor is evaluated by comparing hydrogen bonding energy between the two forms. When the energy of active form is lower than that of inactive form, the ligand is considered an agonist for the receptor. On the other hand, the ligand is considered an antagonist when the energy of inactive form is lower than that of in active form. In the results of docking simulation, NCG21 showed a lower hydrogen bonding energy (−5.75) in the active form of GPR120 model than that in the inactive form (−1.25). Conversely, AH-7614 showed lower hydrogen bonding energy in inactive form (−2.63) than that in active form (−1.90). These results suggested that our docking simulation is able to predict whether a compound is an agonist or an antagonist. The LCFAs share common properties in that the hydrogen bonding energy in the active form is lower than that in inactive form, which is in good agreement with previous experimental results. In contrast, MCFA caprylic acid and capric acid are expected to have antagonistic properties to GPR120 because the hydrogen bonding energy in inactive form is lower than that in active form.

Table 1.

Hydrogen bonding energy between fatty acids and GPR120 homology models

| Ligands | Hydrogen bonding energy (arbitrary unit) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Active form | Inactive form | ||

| NCG21 | GPR120 agonist | −5.75 | −1.25 |

| AH-7614 | GPR120 antagonist | −1.90 | −2.63 |

| C8:0 | Caprylic acid | −4.88 | −5.69 |

| C10:0 | Capric acid | −4.28 | −4.96 |

| C18:1 | Oleic acid | −4.96 | −5.03 |

| C18:2 | Linoleic acid | −4.92 | −2.60 |

| C18:3 | Linolenic acid (ALA) | −4.84 | −4.51 |

| C20:5 | Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) | −4.99 | −3.37 |

| C22:6 | Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) | −4.94 | −3.05 |

MCT oil suppresses high-LCT diet-induced body weight gain and insulin resistance by inhibiting GIP secretion

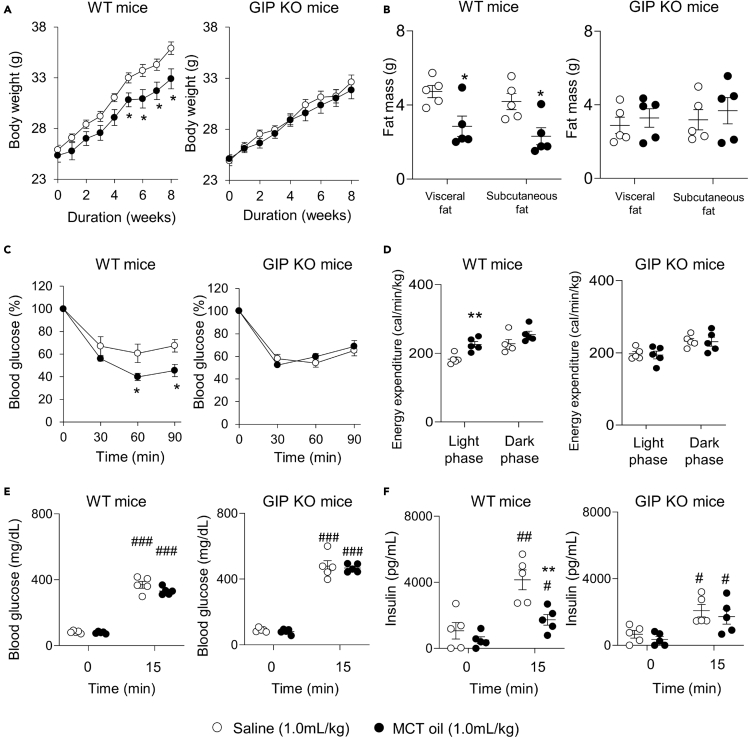

Since MCTs inhibit GIP secretion after a single LCT ingestion by inhibiting the effects of CCK, we then evaluated the effects of MCT-induced inhibition of GIP secretion on obesity and development of insulin resistance during long-term consumption of high-LCT diet. We assessed body weight, body fat mass, and insulin sensitivity in WT and GIP KO mice after administration of MCT oil under high-LCT diet feeding condition (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of MCT oil ingestion on high-LCT diet-induced obesity

(A and B)(A) Body weight and (B) body fat mass in high-LCT diet-fed male WT and GIP KO mice (n = 5 mice).

(C and D)(C) Data of 0.5 U/kg body weight insulin tolerance test (ITT) and (D) energy expenditure in high-LCT diet-fed WT and GIP KO mice (n = 5 mice).

(E and F)(E) Blood glucose and (F) insulin concentration at 0 min and 15 min after 2 g/kg body weight oral glucose loading in high-LCT diet-fed WT and GIP KO mice (n = 5 mice). White circles and black circles indicate saline and MCT oil, respectively. Data indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s t-test. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. 0 min. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. saline group.

In WT mice, body weight, subcutaneous fat mass, and visceral fat mass were significantly less in the MCT oil group compared with those in control group (Figures 5A and 5B). In the GIP KO mice, no significant differences were observed between the two groups. In the ITT, insulin sensitivity was higher in the MCT oil group than that in control group in WT mice (Figure 5C). In GIP KO mice, on the other hand, insulin sensitivity did not differ significantly between the two groups. Energy expenditure in the light phase was significantly higher in the MCT oil group compared with that in control group in WT mice, while no significant differences were observed in GIP KO mice (Figure 5D). The blood glucose concentration at 0 min and 15 min after oral glucose loading did not differ significantly between the MCT oil group and the control group in WT and GIP KO mice (Figure 5E). The insulin concentration at 15 min after oral glucose loading was significantly lower in the MCT oil group compared with that in the control group in WT mice, but did not differ significantly between the two groups in GIP KO mice (Figure 5F). In WT mice, the non-fasting total GIP concentration at Week 8 of high-LCT diet loading were 230.1 ± 25.7 and 505.1 ± 115.7 pg/mL in the MCT oil and control groups, respectively (p < 0.05), showing that MCT oil suppresses an increase in total GIP concentrations under high-LCT diet feeding condition. In GIP KO mice, the non-fasting total GIP concentration was not detected. Food consumption did not differ between the two groups in WT and GIP KO mice (data not shown). We also performed long-term high-LCT diet tolerance tests with or without CCK antagonist in WT and GIP KO mice (Figure S3). CCK antagonist increased body weight (Figure S3A) and fat mass (Figure S3B) not only in WT mice but also in GIP KO mice due to an increase in food intake (Figure S3C). CCK antagonist-treated mice showed reduced insulin sensitivity in WT and GIP KO mice (Figure S3D). In WT and GIP KO mice, energy expenditure and blood glucose concentration during OGTT did not differ significantly between control group and CCK antagonist-treated group (Figures S3E and S3F). Insulin concentration at 15 min after oral glucose loading was significantly higher in CCK antagonist group compared with that in the control group (Figure S3G).

Discussion

Both GPR120 and GPR40 are Gq protein-coupled receptors that are activated by LCFAs. Expressed in various organs (Oh et al., 2010; Yamashima, 2015), GPR120 and GPR40 have been reported to have many physiological effects as an LCFA sensor (Dragano et al., 2017; Nakamoto et al., 2012; Talukdar et al., 2011). Mouse studies visualizing enteroendocrine cells have shown that both receptors are expressed in incretin-producing L cells and K cells, as well as CCK-producing I cells (Edfalk et al., 2008; Hirasawa et al., 2005; Iwasaki et al., 2015; Kato et al., 2020). Studies in intestinal cell lines GLUTag and STC-1 have shown that both receptors are involved in LCFA-induced GLP-1 or CCK secretion (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2012; Tanaka et al., 2008). These findings suggest that in vivo inhibition of GPR120 or GPR40 reduces gut hormone secretion after fat ingestion. We previously generated GPR120/GPR40 double-knockout [double KO (DKO)] mice to measure the secretion of the incretins GLP-1 and GIP after oral corn oil loading (Sankoda et al., 2019), and found no induction of GLP-1 or GIP secretion after fat ingestion in DKO mice, demonstrating that both GPR120 and GPR40 are essential for incretin secretion after fat ingestion. We also performed oral corn oil tests in GPR120-knockout and GPR40-knockout mice to measure the secretion of GLP-1 and GIP (Sankoda et al., 2017). In both single KO (SKO) mice, GIP secretion, but not GLP-1 secretion, was significantly reduced compared with that in WT mice. These reports in DKO and SKO mice suggest the existence of a compensatory mechanism between GPR120 and GPR40 for in vivo GLP-1 secretion. In the present study, we demonstrated that MCTs inhibit LCT-induced GIP secretion by blocking the CCK effect through GPR120 but not GPR40. Taken together, these results may explain why the effect of MCTs on LCT-induced GLP-1 secretion is much less than that on LCT-induced GIP secretion, as shown in Test 2 of Figure 1. We also reported that GIP secretion, CCK secretion, and CCK action such as gallbladder contraction after oral LCT ingestion are impaired in GPR120-knockout mice (Sankoda et al., 2017). CCK agonist recovered GIP secretion after LCT ingestion in GPR120-knockout mice. It remains unclear why GPR120 expressed in K cells is not directly involved in LCT-induced GIP secretion in vivo, but these results suggested that GPR120 is involved in LCT-induced GIP secretion through CCK in vivo.

Our present study showed that MCT oil suppresses body weight gain by blocking the CCK effect through GPR120 under long-term consumption of high-LCT diet. In a previous study, however, decreased energy expenditure and increased body weight were reported in high-LCT diet-fed GPR120-knockout mice compared with that in high-LCT diet-fed WT mice (Ichimura et al., 2012). It is also reported that a GPR120 agonist reduces inflammatory cytokine production by activating GPR120 expressed in adipose tissues and macrophages, and improves insulin sensitivity under high-LCT diet feeding condition (Oh et al., 2010). Overall, these findings indicate that in vivo inhibition of GPR120 signaling may exacerbate obesity and insulin resistance. The apparent disagreement between our results and previous reports may be due to metabolism of MCFAs in the body. After intestinal absorption, MCTs, unlike LCTs, are transported to PV, not to the lymphatic vessels (You et al., 2008). While LCFAs cannot be translocated into the mitochondria matrix in the liver unless acyl CoA binds to carnitine palmitoyltransferase I, MCFAs, which do not require such binding, are much more rapidly metabolized by β-oxidation (Knottnerus et al., 2018; Longo et al., 2016). In the MCT absorption experiment in the present study, caprylic acid and capric acid were detected in PV after oral MCT ingestion, but no MCFAs were detected in IVC, suggesting that MCFAs are mostly metabolized in the liver after transport via PV, with only a fraction being released into the circulation. Therefore, MCFAs might well inhibit GPR120 exclusively in the intestine, not in adipose tissues or macrophages in the whole body. Consequently, MCFA-induced inhibition of GPR120 signaling may result in inhibition of CCK and GIP secretion, reducing body weight.

In in vitro experiments using STC-1 cells in the present study, high dose capric acid reduced ALA-induced CCK secretion. In in vivo experiments using WT mice, on the other hand, low dose MCTs inhibited the CCK effect after a single administration of LCT oil. This difference between in vitro and in vivo results may be due to the difference in digestion and absorption of LCTs versus MCTs in the small intestine. In the present study, thin-layer chromatography showed that all fat components–that is, TGs, DGs, MGs, and FAs–were found in the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum after LCT ingestion, but not in the intestine after MCT ingestion. These results show that while LCTs are slowly digested and absorbed in the intestine, MCTs are very rapidly digested in the small intestine, indicating that the MCFA concentration may be higher than the LCFA concentration in CCK-secreting I cells, which are abundant in the duodenum. These findings suggest that low dose MCTs can inhibit LCT-induced GIP secretion in vivo by inhibiting the CCK effect though GPR120 signaling in the mouse intestine. Therefore, it will be important to determine whether this pathway is also relevant to human GIP secretion.

CCK antagonist induced body weight gain under high-LCT diet feeding, although CCK antagonist inhibited GIP secretion after a single administration of LCT. CCK-producing cells and the CCK-1 receptor (CCK-1R) are expressed in the central nervous system (Beinfeld, 2001), and CCK inhibits food intake (D’Agostino et al., 2016). The CCK-1R-knockout rat is reported to have hyperphagia and obesity (Moran and Bi, 2006). These reports indicated that inhibition of CCK signaling in the central nervous system increases food intake and induces obesity. The CCK antagonist proglumide binds CCK receptors expressed in whole body such as gut and central nervous system (Chiodo and Bunney, 1983). Inhibition of CCK signaling by proglumide in the central nervous system induces hyperphagia, excessive fat mass, and obesity (Shillabeer and Davison, 1984). CCK induces secretion of pancreatic lipase and bile, which are essential for digestion and absorption of LCTs. MCFA derived from MCT inhibits CCK and GIP secretion. However, pharmacological or genetic inhibition of CCK signaling in the whole body might increase body weight gain through the central nervous system.

Hormone regulates secretion of other hormones. Amino acids-induced CCK secretion through luminal CCK-releasing factor (Wang et al., 2002), inhibition of GLP-1 secretion by somatostatin (Hansen et al., 2000), fat-induced stimulation of GLP-1 through GIP (Rocca and Brubaker, 1999), and fatty acid-induced stimulation of peptide YY through CCK (Degen et al., 2007) have been reported. As our present study showed that MCT inhibits LCT-induced GIP secretion through inhibition of CCK secretion, there are many complex pathways participating in the regulation of gut hormone secretion.

In conclusion, MCTs inhibit LCT-induced GIP secretion through GPR120-dependent inhibition of CCK. In addition, MCT-induced inhibition of GIP secretion reduces high-LCT diet-associated obesity and insulin resistance. From our study, identification of molecules that suppress GIP hypersecretion by LCT, such as MCT, might prevent the onset and progression of obesity under high-LCT diet feeding condition.

Limitations of the study

GIP is an incretin hormone that promotes glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells. In previous reports, the blood glucose concentration after a single glucose ingestion was higher in GIP antagonist-treated mice, GIP KO mice, and GIP receptor-knockout mice than that in control mice and WT mice (McClean et al., 2007; Miyawaki et al., 2002; Nasteska et al., 2014). These results indicated that inhibition of GIP signaling or GIP secretion induces impaired glucose tolerance under lean body condition. Although MCT-induced inhibition of GIP secretion alleviated body weight gain and insulin resistance under high-LCT diet-fed obese condition in the present study, the possibility that supplementation of MCT would reduce GIP secretion and have negative effects on glycemic control after meal ingestion under lean body condition cannot be excluded.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Olive oil | Nisshin OilliO Group | N/A |

| MCT oil | Nisshin OilliO Group | N/A |

| [Thr28, Nle31]-Cholecystokinin (25-33) | AnaSpec | Cat# AS-22944 |

| Proglumide | Toronto Research Chemicals | Cat# P755955 |

| Proglumide sodium salt solid | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# M006 |

| Orlistat | Tocris Bioscience | Cat# 3540/50 |

| Linolenic acid | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# L2376 |

| Oleic acid | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# O1008 |

| Octanoic acid (Caplyric acid) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# O3907 |

| Decanoic acid (Capric acid) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# C1875 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| LBIS Mouse Insulin ELISA kit | FUJIFILM Wako Shibayagi Corporation | Cat# AKRIN-011T; RRID: AB_2810836 |

| Rat/Mouse GIP (total) ELISA | Merck | Cat# EZRMGIP-55K; RRID: AB_2801384 |

| VPLEX GLP-1 Total Kit | Meso Scale Discovery | Cat# K1503PD-1 |

| Lipase kit S | SB Bioscience | Cat# 4987-116-88021-3 |

| Bio-Ras Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate | Bio-Rad | Cat# 5000006JA |

| FLIPR Calcium 4 Assay Kit | Molecular Devices | Cat# R8141; RRID: AB_11195743 |

| RNeasy Mini Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 74004 |

| PrimeScript RT reagent kit | Takara Bio | Cat# RR037B |

| SYBR Green PCR Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat# 4334973 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Mouse: STC-1 cell line | Laboratory of Akira Hirasawa Tanaka et al. (2008) |

RRID:CVCL_J405 |

| Human: T-REx GPR40 cell line | Laboratory of Akira Hirasawa Hara et al. (2009) |

N/A |

| Human: T-REx GPR120 cell line | Laboratory of Akira Hirasawa Ichimura et al. (2012) |

N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J mice | Japan SLC | N/A |

| GIP KO mice | Nasteska et al. (2014) | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Silencer®Select Ffar4 Mouse | Invitrogen | Cat# s200889 |

| Silencer®Select Ffar1 Mouse | Invitrogen | Cat# s107454 |

| Silencer™Select Negative Control No. 1 siRNA | Invitrogen | Cat# 4390844 |

| Primers for quantitative real-time PCR | Sankoda et al. (2017) | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Igor Pro | WaveMetrics | RRID:SCR_000325 http://www.wavemetrics.com/products/igorpro/igorpro.htm |

| Molegro Virtual Docker software | Molegro ApS | RRID:SCR_000190 http://molegro-virtual-docker.software.informer.com/ |

| La Theta (LCT-100M) | Hitachi Aloka Medical | N/A |

| SPSS Statistics | IBM | RRID:SCR_019096 https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics |

| Other | ||

| TLC Silica gel 60 F254 25 Aluminium sheets 20 x 20 cm | Merck | Cat# 105554 |

| Rodent Diet With 45 kcal% Fat | Reserch Diet Inc. | Cat# D12451 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Nobuya Inagaki (inagaki@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Animals

Male C57BL/6J (wild-type; WT) mice were purchased from SLC Japan, Inc. (Hamamatsu, Japan). We purchased 10-week-old male WT mice. Oral mixed oil tolerance tests for measurement of blood glucose, insulin, total GIP, and total GLP-1 were performed in 13-week-old mice. Oral mixed oil tolerance tests for measurement of lipase activity and remaining bile volume were performed in 15-week-old mice. Oral mixed oil tolerance tests for measurement of intestinal transit were performed in 17-week-old mice. Intestinal lipase activity under fasting state was measured in 15-week-old mice. Oral saline, olive oil, or MCT oil tolerance tests for measurement of lipase activity, remaining bile volume, and lipid and fatty acid compositions were performed in 15-week-old mice. Oral MCT oil or saline administration tests using a CCK agonist were performed in 15-week-old mice. Oral olive oil tolerance tests using CCK antagonist were performed in 13-week-old mice. In all oral oil tolerance tests, there was no significant difference in body weight in WT mice.

We generated GIP KO mice previously (Nasteska et al., 2014). In our previous study, there was no significant difference in body weight (from 4-week old to 8-week old) and fat mass (8-week old) between WT mice and GIP KO mice under normal diet condition, whereas GIP KO mice had lower body weight and fata mass and higher insulin sensitivity then WT mice under high-LCT diet feeding condition (Nasteska et al., 2014). At 6-week-old, male littermate WT mice and GIP KO mice fed high-LCT diet for 10 weeks. Insulin tolerance test (ITT) was performed in 16-week-old mice after 10 weeks of high-LCT diet feeding. Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed in 18-week-old mice after 12 weeks of high-LCT diet feeding. Fat mass and energy expenditure were measured in 20-week-old mice after 14 weeks of high-LCT diet feeding. All mice were fed ad libitum under a 14 hr/10 hr light-dark cycle. Experiments on animals were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (MedKyo16584) and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of the Animal Research Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine.

Male mice were used for all in vivo experiments in this study, because menstruation could affect metabolic factors such as glucose and insulin concentration.

Cell lines

STC-1(CA 94143), T-REx GPR40 and T-REx GPR120 cell line are cultured as described previously (Tanaka et al., 2008; Hara et al., 2009; Ichimura et al., 2012).

STC-1 cells are maintained Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Cat# D5796, Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Cat# 10,270-106, Gibco) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Cat# 15,140-122, Gibco). T-REx GPR40 and T-REx GPR120 cells are maintained DMEM (Cat# D6429, Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Cat# 10,437-028, Gibco) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2, respectively.

Method details

Oral mixed oil tolerance tests

Oral mixed oil tolerance tests were performed in the 13-week-old WT mice after intravenous injection of saline (Control) or CCK agonist [Thr28, Nle31]-CCK (Cat# AS-22944; AnaSpec, Inc., Fremont, CA, US) (200 ng/kg body weight) (Sankoda et al., 2017). The MCT oil (The Nisshin OilliO Group, Tokyo, Japan) contained octanoic acid (C8:0) and decanoic acid (C10:0) at a ratio of 75:25 (%). On the other hand, the LCT oil was olive oil (The Nisshin OilliO Group, Tokyo, Japan). In Test 1, olive oil (13.3 mL/kg body weight) or mixed oil (10.0 mL/kg olive oil + 3.3 mL/kg MCT oil; 13.3 mL/kg body weight) was orally administered to 16-h fasted mice by oral gavage so that the same dose of oil was administered. In Test 2, olive oil (10.0 mL/kg body weight) or mixed oil (10.0 mL/kg olive oil + 3.3 mL/kg MCT oil; total of 13.3 mL/kg body weight) was orally administered to mice so that the same dose of olive oil was administered.

In each test, two groups of mice were used to reduce the burden of animal testing on the mice and collect samples at many time points. Blood samples (60 μL) were collected at 0, 15, and 60 min post-dose in one group, and at 0, 30, and 120 min post-dose in the other group using heparinized calibrated glass capillary tubes (Cat# 2-000-044-H; Drummond Scientific Company, Broomall, PA, USA).

Blood glucose levels were measured using Glutest Neo Sensor (Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan). Plasma samples were prepared by centrifugation of the blood samples at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, and were subjected to measure insulin, total GIP and total GLP-1. Oral olive oil tolerance tests using a CCK antagonist were performed in 13-week-old mice.

Oral MCT oil or saline administration tests using a CCK agonist

Oral MCT or saline administration tests were performed in the 15-week-old WT mice after intravenous injection of saline (5 mL/kg body weight) or CCK agonist (200 ng/5mL/kg). MCT oil or saline (10.0 mL/kg, respectively) was orally administered to 16-h fasted mice by oral gavage. Blood samples (30 μL) were collected at 0 and 30 min post-dose. Plasma samples were prepared by centrifugation of the blood samples at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, and were subjected to measure total GIP.

Oral olive oil tolerance tests using a CCK antagonist

Oral olive oil tolerance tests were performed in the 13-week-old WT mice. Olive oil (10.0 mL/kg) or olive oil (10.0 mL/kg) + CCK antagonist proglumide (Cat# P755955, Toronto Research Chemicals Inc., North York, ON, Canada) (500mg/kg body weight) was orally administered to 16-h fasted mice by oral gavage. Same as the oral mixed oil tolerance tests, two groups of mice were used and blood samples were collected at 0, 15, and 60 min post-dose in one group, and at 0, 30, and 120 min post-dose in the other group. Blood samples were subjected to measure blood glucose, and plasma samples were subjected to measure insulin, total GIP and total GLP-1.

Oral saline, olive oil or MCT oil tolerance tests

Oral saline, olive oil or MCT oil tolerance tests were performed in the 15-week-old WT mice. Saline (10.0 mL/kg), olive oil (10.0 mL/kg) or MCT oil (10.0 mL/kg) was orally administered to 16-h fasted mice by oral gavage. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and subjected to abdominal laparotomy at 30 min after administration of saline, olive oil, or MCT oil. Blood samples were collected through the portal vein (PV) and inferior vena cava (IVC).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Concentrations of insulin, total GIP, and total GLP-1 were measured using ELISA kits for insulin (Cat# AKRIN-011T, FUJIFILM Wako Shibayagi Corporation, Gunma, Japan), total GIP (Cat# EZRMGIP-55K, Merck, Billerica, MA, US), and total GLP-1 (Cat# K1503PD-1, Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD, US), respectively.

Measurement of intestinal transit after oral mixed oil tolerance tests

The small intestine was removed at 30 min after oral administration of Oil Red-stained (0.5% v/v) oil to 17-week-old male WT mice, and intestinal transit was calculated as the proportion (%) of the small intestine stained by Oil Red relative to the entire small intestine.

Measurement of lipase activity and gallbladder contraction after oral tolerance tests

The jejunum and gallbladder were removed at 30 min after oral administration. The small intestinal contents were collected from jejunum and are centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Water layer was used for the measurement of lipase activity. Lipase activity was measured using the BALB-DTNB method (SB Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan) (Furukawa et al., 1982). The bile in the gallbladder was collected using a 29G syringe (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) and the bile volume was measured. Gallbladder contraction was assessed from the volume of bile remaining in the gallbladder.

Measurement of lipase activity in the fasting state

15-week-old and 16-h fasted male WT mice were sacrificed. The gastrointestinal mucosa of stomach, duodenum (0-5 cm from pyloric sphincter), jejunum (20-25 cm from pyloric sphincter), ileum (0-5 cm from cecum) was collected and homogenized up to 100mg of gastrointestinal mucosa in 1 mL saline. Following homogenization, insoluble material from the homogenate was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C; the supernatant was used for the experiments. Lipase activity was measured using the BALB-DTNB method. Separately, the protein content in the sample was measured using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) to correct the lipase activity.

Ligation of pylorus and jejunum

15-week-old and 16-h fasted male WT mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and subjected to abdominal laparotomy. We ligated only pylorus or both pylorus and duodenojejunal transition with nylon string; subsequently, MCT oil or MCT oil + lipase inhibitor orlistat (Cat# 3540/50) (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) (100mg/kg body weight) was injected into the stomach or duodenum. Blood samples were collected through PV and IVC at 30 min after administration of MCT oil.

Lipid and fatty acid compositions using chromatography analysis

Lipids were extracted from blood and intestinal content samples using chloroform/methanol/1.5% KCl (2:2:1, by volume) according to the Bligh–Dyer method, and the solvent was removed using N2 gas.

Thin-layer chromatography was performed to detect the following lipids in the stomach and small intestinal contents: triglycerides (TGs), diglycerides (DGs), monoglycerides (MGs), and fatty acids (FAs). For thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis, 0.2 mg of each sample and standard was spotted onto a silica gel TLC plate (Kieselgel 60 F254; Merck, MA, USA), and developed with a solvent system containing hexane/diethylester/acetic acid (60/40/1, v/v/v). Lipids were visualized by spraying the plates with 0.01% primuline in 80% acetone and detected qualitatively by UV absorbance with a wavelength at 365 nm.

Gas chromatography was performed to assess the plasma fatty acid composition, and data were expressed as the proportion (%) of MCFAs in all fatty acids. For gas-chromatography (GC) analysis, 1 mg was methylated by incubation with 1.3% methanolic HCl at 100°C for 1 hour. After methylation, the fatty acids methyl esters were extracted with n-hexane. The resulting fatty acid methyl esters were quantitively determined by Shimadzu GC-1700 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector, and fitted with a capillary column (TC-70; 60 m length × 0.25 mm i.d.; GL Sciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The initial column temperature of 165°C was maintained for 2 min, increased to 180°C at a rate of 5°C/min and maintained for 5 min, and increased to 260°C at a rate of 5°C/min and finally maintained at that temperature for 5 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 0.97 mL/min. Data were expressed as the proportion (%) of MCFAs in all fatty acids.

Long-term food tolerance test

Saline (1.0 mL/kg body weight), MCT oil (1.0 mL/kg body weight) was administered to high-LCT diet (45% fat by energy, 4.73 kcal/g, Cat# D12451) (Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, US)-fed, 6-week-old male WT mice and GIP KO mice once daily at 8:00 p.m. by oral gavage. In long-term high-LCT diet tolerance test using a CCK antagonist, drinking water or drinking water supplemented with the CCK antagonist proglumide (0.1 mg/mL, approximately 30 mg/kg/day) (Sigma- Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was administered. Body weights were measured once a week. Insulin tolerance test (ITT) and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) were performed at weeks 10 and 12 of loading. Fat mass and energy expenditure were measured using computed tomography (CT) and an indirect calorimeter, respectively, at week 14 of loading.

Measurement of insulin sensitivity and blood glucose and insulin concentration after oral glucose loading

Human insulin (Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, US) was intraperitoneally administered to 4-hr fasted mice (0.5 U/kg body weight). Blood glucose levels were measured at 0, 30, 60, and 90 min after insulin loading. Results were calculated with blood glucose level at 0 min considered as 100%. Glucose (2 g/kg body weight) was orally administered to 16-hr fasted mice. Blood samples were collected through the tail vein at 0 and 15 min after glucose loading. Blood glucose and insulin levels were measured.

Measurement of energy expenditure and body fat mass

The energy expenditure was measured using an ARCO 2000 (ARCO System Inc., Chiba, Japan). The fat mass was measured using a La Theta (LCT-100M) experimental animal CT system (Hitachi Aloka Medical, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Fatty acid-induced CCK secretion from STC-1 cells

The murine intestinal cell line STC-1 was used (Tanaka et al., 2008). The fatty acid tolerance test was performed 48 hr after seeding STC-1 cells (4 × 105 cells) in 12-well plates. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times and then cultured in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing fatty acids at 37°C for 60 min (Kawasaki et al., 2010). The culture broth was centrifuged at 800 ×g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. CCK concentrations in the supernatant were measured using the CCK (26-33) non-sulfated - Fluorescent EIA Kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Belmont, CA, US). The antibody to CCK in this kit is cross-reactive with gastrin.

Fatty acid-induced [Ca2+]i in GPR40- and GPR120-expressing cells

Previously established HEK293 cells stably expressing GPR120 and GPR40 (T-REx GPR120 and T-REx GPR40, respectively) were used (Hara et al., 2009; Ichimura et al., 2012). T-REx GPR120 cells or T-REx GPR40 cells (2.0 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in collagen-coated 96-well plates and cultured in an incubator at 37°C for 2 hr. After the addition of 1 μg/mL doxycycline and, 24 hr later, the addition of Component A in HBSS from a FLIPR Calcium 4 Assay Kit (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, US), the cells were further cultured at room temperature for 30 min. Fatty acids in HBSS + 20 mM HEPES buffer were added to other 96-well plates.[Ca2+]i were monitored in all plates by an FDSS/μCELL imaging plate reader (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Shizuoka, Japan). Data were analyzed using Igor Pro (WaveMetrics, Inc, Lake Oswego, OR, US), and the change in [Ca2+]i was calculated, with [Ca2+]i after addition of 100 μM α-linolenic acid (ALA) considered as 1.0.

Small interfering RNA(siRNA) transfection into STC-1 cells

STC-1 cells (4.5 × 105 cells/well) were mixed with Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, US) containing murine GPR120 or GPR40 Silencer Select siRNA (siRNA ID: s200889 and s107454, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, US), Silencer™ Negative Control No. 1 siRNA (Invitrogen), and Lipofectamine 2000 were seeded in 12-well plates and cultured at 37°C. After 48 hr of culture, the cells were analyzed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for GPR120 mRNA or GPR40 mRNA expression. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). RT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, US), and expression levels were determined using the ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The signals of the products were standardized using β-actin as reference. The primer sequences for β-actin, GPR120, and GPR40 have already been reported (Sankoda et al., 2017).

Docking simulation

The previously reported homology models of the active and inactive form of GPR120 based on bovine rhodopsin structure were used (Sun et al., 2010; Takeuchi et al., 2013). The molecular docking of compounds against the GPR120 model was performed by the molecular docking algorithm MolDock using Molegro Virtual Docker software (Molegro ApS, Aarhus, Denmark) (Thomsen and Christensen, 2006). The hydrogen bonding energy, which is considered to be one of the important parameters in characterizing the interaction between GPCRs and their ligands (Shim et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2010; Xhaard et al., 2006), was estimated in arbitrary units using the Molegro program. Binding of MCFAs (octanoic acid [C8:0] and decanoic acid [C10:0]) or long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) (oleic acid [C18:1], linoleic acid [C18:2], α-linolenic acid [C18:3], eicosapentaenoic acid [C20:5], and docosapentaenoic acid [C22:6]) to GPR120 was simulated. NCG21 and AH-7614 have been reported to be a GPR120 agonist and a GPR120 antagonist, respectively (Sun et al., 2010).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical analyses were performed with the Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s test using SPSS Statistics 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, US). The level of statistical significance was P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shoichi Asano for technical support regarding the study.

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) [Grant No. 19K09022], Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Japan Diabetes Foundation, Japan Association for Diabetes Education and Care, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) Life Science Foundation, Public Interest Incorporated Foundation, Japan Diabetes Foundation, and Suzuken Memorial Foundation.

Author contributions

Y.M. and N.H. planned the study, analyzed the data, contributed to the discussion, wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. S.K. planned the study, analyzed the data, contributed to the discussion, reviewed and edited the manuscript. S.Y. and K.I. planned the study and contributed to the discussion. E.I-O., T.K., Y.K., A.S., T.H., and S.K. contributed to the discussion. J.O. contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript. A.H. planned the study, analyzed data, contributed to the discussion, reviewed and edited the manuscript. N.I. planned the study, contributed to the discussion, and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

N. I. received joint research grants from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.,Terumo Co., Ltd., and Drawbridge, Inc.; received speaker honoraria from Kowa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; MSD, Astellas Pharma Inc.,Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd.,Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd.,Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Ltd.; received scholarship grant from Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.,Sanofi, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.,Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Ltd.,Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Japan Tobacco Inc.,Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd.,Astellas Pharma Inc.,MSD, Eli Lilly Japan, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co. Ltd., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd.,Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd.,Novartis Pharma K.K.,Teijin Pharma Ltd., and Life Scan Japan Inc.. N. H. received scholarship grant from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Ltd.,Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd. All other authors have nothing to disclose. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Published: September 24, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102963.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data. These accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Babayan E.A. The organization of psychiatric services in the USSR and the role of the nurse. J. Psychiatr. Nurs.Ment. Health Serv. 1968;6:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach A.C., Babayan V.K. Medium-chain triglycerides: an update. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982;36:950–962. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinfeld M.C. An introduction to neuronal cholecystokinin. Peptides. 2001;22:1197–1200. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan M.O., Glazebrook P.A., Tatalovic M., Wolfe M.M. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide immunoneutralization attenuates development of obesity in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;309:E1008–E1018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00345.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray G.A., Paeratakul S., Popkin B.M. Dietary fat and obesity: a review of animal, clinical and epidemiological studies. Physiol. Behav. 2004;83:549–555. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray G.A., Popkin B.M. Dietary fat intake does affect obesity! Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998;68:1157–1173. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe C.P., Tadayyon M., Andrews J.L., Benson W.G., Chambers J.K., Eilert M.M., Ellis C., Elshourbagy N.A., Goetz A.S., Minnick D.T. The orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR40 is activated by medium and long chain fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11303–11311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211495200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo L.A., Bunney B.S. Proglumide: selective antagonism of excitatory effects of cholecystokinin in central nervous system. Science. 1983;219:1449–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.6828873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M., Morgan R.G., Hofmann A.F. Lipolytic activity of human gastric and duodenal juice against medium and long chain triglycerides. Gastroenterology. 1971;60:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell D.L., Zuccaro G., Morrow J.B., Van Lente F., Obuchowski N., Vargo J.J., Dumot J.A., Trolli P., Shay S.S. Cholecystokinin-stimulated peak lipase concentration in duodenal drainage fluid: a new pancreatic function test. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1392–1397. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino G., Lyons D.J., Cristiano C., Burke L.K., Madara J.C., Campbell J.N., Garcia A.P., Land B.B., Lowell B.B., Dileone R.J. Appetite controlled by a cholecystokinin nucleus of the solitary tract to hypothalamus neurocircuit. Elife. 2016;5:e12225. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degen L., Drewe J., Piccoli F., Grani K., Oesch S., Bunea R., D'Amato M., Beglinger C. Effect of CCK-1 receptor blockade on ghrelin and PYY secretion in men. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr.Comp. Physiol. 2007;292:R1391–R1399. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00734.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas B.R., Jansen J.B.M.J., Dejong A.J.L., Lamers C.B.H.W. Effect of various triglycerides on plasma cholecystokinin levels in rats. J. Nutr. 1990;120:686–690. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.7.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragano N.R.V., Solon C., Ramalho A.F., de Moura R.F., Razolli D.S., Christiansen E., Azevedo C., Ulven T., Velloso L.A. Polyunsaturated fatty acid receptors, GPR40 and GPR120, are expressed in the hypothalamus and control energy homeostasis and inflammation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017;14:91. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0869-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edfalk S., Steneberg P., Edlund H. Gpr40 is expressed in enteroendocrine cells and mediates free fatty acid stimulation of incretin secretion. Diabetes. 2008;57:2280–2287. doi: 10.2337/db08-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber J., Goldstein R., Blondheim O., Stankiewicz H., Darwashi A., Bar-Maor J.A., Gorenstein A., Eidelman A.I., Freier S. Absorption of medium chain triglycerides in the stomach of the human infant. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol.Nutr. 1988;7:189–195. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198803000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint A., Raben A., Astrup A., Holst J.J. Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:515–520. doi: 10.1172/JCI990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa I., Kurooka S., Arisue K., Kohda K., Hayashi C. Assays of serum lipase by the "BALB-DTNB method" mechanized for use with discrete and continuous-flow analyzers. Clin. Chem. 1982;28:110–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger N.J., Rodgers J.B., Isselbacher K.J. Absorption of medium and long chain triglycerides: factors influencing their hydrolysis and transport. J. Clin. Invest. 1966;45:217–227. doi: 10.1172/JCI105334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen L., Hartmann B., Bisgaard T., Mineo H., Jorgensen P.N., Holst J.J. Somatostatin restrains the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 and -2 from isolated perfused porcine ileum. Am. J. Physiol.Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;278:E1010–E1018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.6.E1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T., Hirasawa A., Ichimura A., Kimura I., Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acid receptors FFAR1 and GPR120 as novel therapeutic targets for metabolic disorders. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011;100:3594–3601. doi: 10.1002/jps.22639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T., Hirasawa A., Sun Q., Sadakane K., Itsubo C., Iga T., Adachi T., Koshimizu T.A., Hashimoto T., Asakawa Y. Novel selective ligands for free fatty acid receptors GPR120 and GPR40. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2009;380:247–255. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N., Hamasaki A., Yamane S., Muraoka A., Joo E., Fujita K., Inagaki N. Plasma gastric inhibitory polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 levels after glucose loading are associated with different factors in Japanese subjects. J. Diabetes Invest. 2011;2:193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N., Yamada Y., Tsukiyama K., Yamada C., Nakamura Y., Mukai E., Hamasaki A., Liu X., Toyoda K., Seino Y. A novel GIP receptor splice variant influences GIP sensitivity of pancreatic beta-cells in obese mice. Am. J. Physiol.Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;294:E61–E68. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00358.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauge M., Vestmar M.A., Husted A.S., Ekberg J.P., Wright M.J., Di Salvo J., Weinglass A.B., Engelstoft M.S., Madsen A.N., Luckmann M. GPR40 (FFAR1) - combined Gs and Gq signaling in vitro is associated with robust incretin secretagogue action ex vivo and in vivo. Mol. Metab. 2015;4:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa A., Tsumaya K., Awaji T., Katsuma S., Adachi T., Yamada M., Sugimoto Y., Miyazaki S., Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat. Med. 2005;11:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nm1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura A., Hirasawa A., Poulain-Godefroy O., Bonnefond A., Hara T., Yengo L., Kimura I., Leloire A., Liu N., Iida K. Dysfunction of lipid sensor GPR120 leads to obesity in both mouse and human. Nature. 2012;483:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature10798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M., Ohtake T., Motomura W., Takahashi N., Hosoki Y., Miyoshi S., Suzuki Y., Saito H., Kohgo Y., Okumura T. Increased expression of PPARgamma in high fat diet-induced liver steatosis in mice. Biochem.Biophys.Res. Commun. 2005;336:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs P.E., Ladas S., Forgacs I.C., Dowling R.H., Ellam S.V., Adrian T.E., Bloom S.R. Comparison of effects of ingested medium- and long-chain triglyceride on gallbladder volume and release of cholecystokinin and other gut peptides. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1987;32:481–486. doi: 10.1007/BF01296030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y., Kawamata Y., Harada M., Kobayashi M., Fujii R., Fukusumi S., Ogi K., Hosoya M., Tanaka Y., Uejima H. Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40. Nature. 2003;422:173–176. doi: 10.1038/nature01478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K., Harada N., Sasaki K., Yamane S., Iida K., Suzuki K., Hamasaki A., Nasteska D., Shibue K., Joo E. Free fatty acid receptor GPR120 is highly expressed in enteroendocrine K cells of the upper small intestine and has a critical role in GIP secretion after fat ingestion. Endocrinology. 2015;156:837–846. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo E., Harada N., Yamane S., Fukushima T., Taura D., Iwasaki K., Sankoda A., Shibue K., Harada T., Suzuki K. Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor signaling in adipose tissue reduces insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet-fed mice. Diabetes. 2017;66:868–879. doi: 10.2337/db16-0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T., Harada N., Ikeguchi E., Sankoda A., Hatoko T., Lu X., Yasuda T., Yamane S., Inagaki N. Gene expression of nutrient-sensing molecules in I cells of CCK reporter male mice. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2020;66:11–22. doi: 10.1530/JME-20-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y., Harashima S., Sasaki M., Mukai E., Nakamura Y., Harada N., Toyoda K., Hamasaki A., Yamane S., Yamada C. Exendin-4 protects pancreatic beta cells from the cytotoxic effect of rapamycin by inhibiting JNK and p38 phosphorylation. Horm.Metab. Res. 2010;42:311–317. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer T.J. Gastro-intestinal hormones GIP and GLP-1. Ann. Endocrinol.(Paris) 2004;65:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4266(04)95625-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.J., Nian C., Karunakaran S., Clee S.M., Isales C.M., McIntosh C.H. GIP-overexpressing mice demonstrate reduced diet-induced obesity and steatosis, and improved glucose homeostasis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knottnerus S.J.G., Bleeker J.C., Wust R.C.I., Ferdinandusse S., IJlst L., Wijburg F.A., Wanders R.J.A., Visser G., Houtkooper R.H. Disorders of mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid oxidation and the carnitine shuttle. Rev. Endocr. Metab.Disord. 2018;19:93–106. doi: 10.1007/s11154-018-9448-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhre R.E., Wewer Albrechtsen N.J., Deacon C.F., Balk-Moller E., Rehfeld J.F., Reimann F., Gribble F.M., Holst J.J. Peptide production and secretion in GLUTag, NCI-H716, and STC-1 cells: a comparison to native L-cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2016;56:201–211. doi: 10.1530/JME-15-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle R.A., Goldfine I.D., Rosen M.S., Taplitz R.A., Williams J.A. Cholecystokinin bioactivity in human plasma. Molecular forms, responses to feeding, and relationship to gallbladder contraction. J. Clin. Invest. 1985;75:1144–1152. doi: 10.1172/JCI111809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo N., Frigeni M., Pasquali M. Carnitine transport and fatty acid oxidation. Biochim.Biophys. Acta. 2016;1863:2422–2435. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Swaminath G., Brown S.P., Zhang J., Guo Q., Chen M., Nguyen K., Tran T., Miao L., Dransfield P.J. A potent class of GPR40 full agonists engages the enteroinsular axis to promote glucose control in rodents. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean P.L., Irwin N., Cassidy R.S., Holst J.J., Gault V.A., Flatt P.R. GIP receptor antagonism reverses obesity, insulin resistance, and associated metabolic disturbances induced in mice by prolonged consumption of high-fat diet. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;293:E1746–E1755. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00460.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki K., Yamada Y., Ban N., Ihara Y., Tsukiyama K., Zhou H., Fujimoto S., Oku A., Tsuda K., Toyokuni S. Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide signaling prevents obesity. Nat. Med. 2002;8:738–742. doi: 10.1038/nm727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran T.H., Bi S. Hyperphagia and obesity in OLETF rats lacking CCK-1 receptors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2006;361:1211–1218. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroz P.A., Finan B., Gelfanov V., Yang B., Tschop M.H., DiMarchi R.D., Perez-Tilve D. Optimized GIP analogs promote body weight lowering in mice through GIPR agonism not antagonism. Mol. Metab. 2019;20:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumme K., Stonehouse W. Effects of medium-chain triglycerides on weight loss and body composition: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015;115:249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y., Harada N., Yamane S., Iwasaki K., Ikeguchi E., Kanemaru Y., Harada T., Sankoda A., Shimazu-Kuwahara S., Joo E. Medium-chain triglyceride diet stimulates less GIP secretion and suppresses body weight and fat mass gain compared with long-chain triglyceride diet. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019;317:E53–E64. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00200.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto K., Nishinaka T., Matsumoto K., Kasuya F., Mankura M., Koyama Y., Tokuyama S. Involvement of the long-chain fatty acid receptor GPR40 as a novel pain regulatory system. Brain Res. 2012;1432:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasteska D., Harada N., Suzuki K., Yamane S., Hamasaki A., Joo E., Iwasaki K., Shibue K., Harada T., Inagaki N. Chronic reduction of GIP secretion alleviates obesity and insulin resistance under high-fat diet conditions. Diabetes. 2014;63:2332–2343. doi: 10.2337/db13-1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M., Fleming T., Robinson M., Thomson B., Graetz N., Margono C., Mullany E.C., Biryukov S., Abbafati C., Abera S.F. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata H., Seino Y., Harada N., Iida A., Suzuki K., Izumoto T., Ishikawa K., Uenishi E., Ozaki N., Hayashi Y. KATP channel as well as SGLT1 participates in GIP secretion in the diabetic state. J. Endocrinol. 2014;222:191–200. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh D.Y., Talukdar S., Bae E.J., Imamura T., Morinaga H., Fan W., Li P., Lu W.J., Watkins S.M., Olefsky J.M. GPR120 is an omega-3 fatty acid receptor mediating potent anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Cell. 2010;142:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie J.R., Guzik T.J., Touyz R.M. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: clinical insights and vascular mechanisms. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018;34:575–584. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilichiewicz A., O'Donovan D., Feinle C., Lei Y., Wishart J.M., Bryant L., Meyer J.H., Horowitz M., Jones K.L. Effect of lipase inhibition on gastric emptying of, and the glycemic and incretin responses to, an oil/aqueous drink in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol.Metab. 2003;88:3829–3834. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preitner F., Ibberson M., Franklin I., Binnert C., Pende M., Gjinovci A., Hansotia T., Drucker D.J., Wollheim C., Burcelin R. Gluco-incretins control insulin secretion at multiple levels as revealed in mice lacking GLP-1 and GIP receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:635–645. doi: 10.1172/JCI20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca A.S., Brubaker P.L. Role of the vagus nerve in mediating proximal nutrient-induced glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1687–1694. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.4.6643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]