Abstract

Ectotherms are exposed to a range of environmental temperatures and may face extremes beyond their upper thermal limits. Such temperature extremes can stimulate aerobic metabolism toward its maximum, a decline in aerobic substrate oxidation, and a parallel increase of anaerobic metabolism, combined with ROS generation and oxidative stress. Under these stressful conditions, marine organisms recruit several defensive strategies for their maintenance and survival. However, thermal tolerance of ectothermic organisms may be increased after a brief exposure to sub-lethal temperatures, a process known as "hardening". In our study, we examined the ability of M. galloprovincialis to increase its thermal tolerance under the effect of elevated temperatures (24, 26 and 28 °C) through the "hardening" process. Our results demonstrate that this process can increase the heat tolerance and antioxidant defense of heat hardened mussels through more efficient ETS activity when exposed to temperatures beyond 24 °C, compared to non-hardened individuals. Enhanced cell protection is reflected in better adaptive strategies of heat hardened mussels, and thus decreased mortality. Although hardening seems a promising process for the maintenance of aquacultured populations under increased seasonal temperatures, further investigation of the molecular and cellular mechanisms regulating mussels’ heat resistance is required.

Subject terms: Animal physiology, Climate change

Introduction

Climate change, leading to an increase in sea surface temperatures, affects marine organisms at all levels of biological organization, including molecular, biochemical, and physiological1–3. Ectotherms are particularly sensitive to these changes due to the direct effect of ambient temperature on the body temperature, and thus on the rates of all biochemical and physiological reactions. According to the OCLTT hypothesis, temperature increase beyond organism’s optimum limits (at pejus temperatures, Tp) leads to a mismatch between energy demand and energy supply from aerobic pathways, a compensatory shift to partial anaerobiosis, and energy deficiency3–6. Furthermore, the deviation of temperature from optimum conditions negatively affects the cellular redox balance because supraoptimal (pejus) temperatures lead to elevated electron leak from the ETS in ectotherms’ mitochondria7,8, further enhanced by temperature-induced oxygen deficiency (hypoxemia)3,4,8,9. Oxidative stress caused by excessive ROS production can lead to cellular damage and eventually cell death, so that mitigation of the oxidative stress via adjustment of mitochondrial ETS activity and/or upregulation of antioxidants plays a key role in the survival and contributes to the costs of cellular homeostasis under heat stress8,10–14.

Thermal tolerance of organisms is a plastic trait and can be modified by acclimation to different thermal regimes, as well as by brief exposures to sub-lethal temperatures which are known as heat hardening15. Heat hardening is defined as a transient response that confers improved heat tolerance immediately after the initial heat-stress bout for up to 32 h, while longer-lasting improvements in heat tolerance are termed as heat acclimation15,16. This adaptive response was firstly described by Precht17, who defined “hardening” as a rapid beneficial response occurring within a few hours in contrast to acclimation that may take days. Heat hardening might be considered as a special case of a broader phenomenon of stress hormesis (also termed stress priming, preconditioning or acquired stress response), where a mild stress confers enhanced resistance toward higher levels of the same stress or to a stressor of a different nature18. The mechanisms of heat hardening are not yet fully understood but involve co-activation of multiple stress signaling pathways (including reactive oxygen, nitrogen and carbonyl species, unfolded protein response and transcription factors) that lead to phenotypes with increased resistance19–22. Mitochondria play a key role in hormetic responses such as heat hardening by releasing ROS and other signaling molecules that induce the cellular stress response8,23. Activation of stress signaling pathways leads to a concerted cellular response at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels that restore metabolic, proteome, and redox homeostasis, and can protect the organism against subsequent stress impacts24–27.

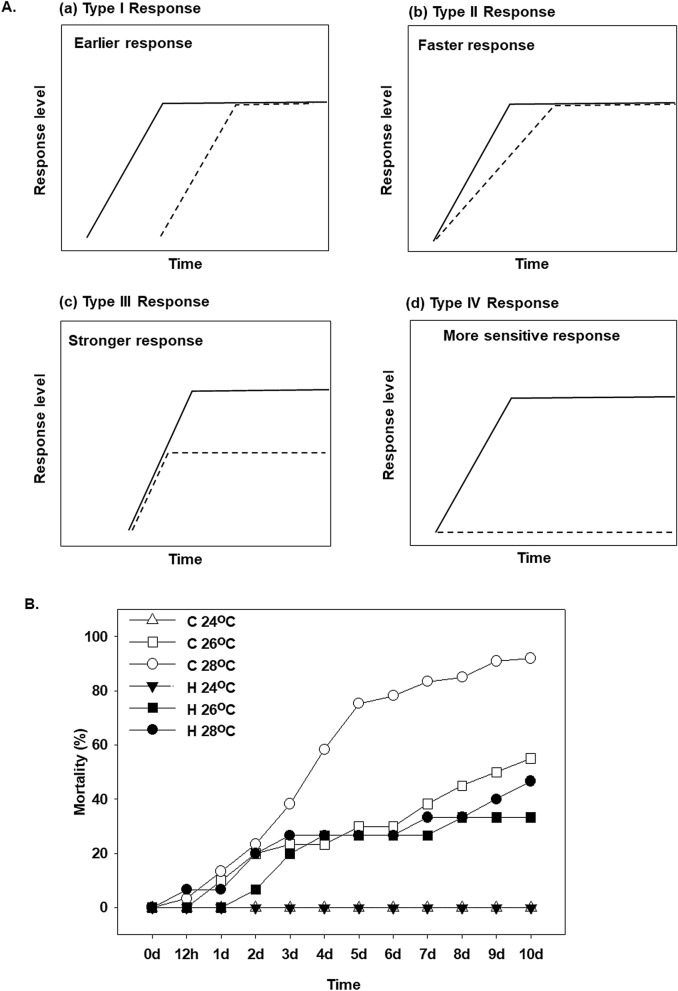

Depending on the amplitude and the time course, four main types of stress responses involved in hardening have been described18,28 (Fig. 1A). An earlier-onset (type I response) hardened stress response exhibits the same kinetics of stress pathway activation as in a naïve organism exposed to stress, but with a shorter lag phase until the stress response starts to build up in a preconditioned organism. Consequently, the final defense level is reached earlier in hardened than in the naïve state. In a faster hardening stress response (type II response), an hyperactivation and a faster signaling cascade is observed, leading to a more rapid buildup of the stress defense in a preconditioned organism. The stronger stress response (type III response) in a hardened organism initially resembles the naïve response, but activation of stress response mechanisms reaches a higher final level than in the naïve organism. Under these conditions, hyperactivation and an enhanced gene expression could be responsible, resulting in a higher response amplitude. Higher sensitivity hardening stress response (type IV response), indicating a triggering response in lower stress intensity in contrast with naïve organism. These changes in the expression pattern and thresholds of the transcriptional induction of stress response genes during heat hardening play an important role in development of the heat-tolerant phenotypes of animals29–33. Such phenotypic plasticity in response to heat hardening have been proposed as an adaptive strategy under the extreme heat events predicted with climate change for marine mussels including Mytilus californianus (Conrad, 1837)34. However, the physiological and molecular mechanisms of heat hardening are not well understood in marine ectotherms, including mussels, and require further investigation to assess the potential mechanisms underlying the organism’ ability to cope with extreme weather events such as marine heat waves.

Figure 1.

(A) Four main types of stress responses depending on the amplitude and the time course, involved in hardening have been described in Conrath et al. 28 and Hilker et al. 18: (a) an earlier stress response (type I response), (b) a faster stress response (type II response), (c) a stronger stress response (type III response) and (d) a higher sensitivity hardening stress response (type IV response). Continuous lines indicate primed response to stress while dashed lines indicate non-primed response to stress. (B) Effect of water temperature (24, 26 and 28 °C) on the mortality of heat hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) Mytilus galloprovincialis compared to control at 18 °C.

The Mediterranean mussel M. galloprovincialis (Lamarck, 1819) is an ecologically and economically important species of marine bivalves and is used in research on stress responses to warming. Previous studies showed that M. galloprovincialis is thermally stressed when exposed to 26 °C–27 °C which results in gradually increased mortality35,36. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether heat hardening enhances thermal tolerance of M. galloprovincialis, and whether transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional regulation of the pathways involved in mitochondrial energy metabolism, antioxidant defense, and protein quality control are implicated in this phenomenon. To assess the impact of acute heat stress and heat hardening on mitochondrial bioenergetics, we examined mRNA expression of mitochondrial encoded subunits of complex I and IV of ETS (ND2 and COX1, respectively) and determined the ETS activity in the mantle of control, heat stressed and heat-hardened mussels. ETS activity is an indicator of the maximal velocity (Vmax) of the ETS multi-enzyme complexes and is considered a biochemical measure of the metabolic potential of organisms13. To assess the cellular energy status, levels of phosphorylated AMPK (a key energy sensor activated in response to low cellular ATP levels) were measured. To determine the potential involvement of oxidative stress and redox signaling in heat hardening, we determined mRNA expression of enzymatic CuSOD, MnSOD, GST, CAT, and non-enzymatic (mt10) antioxidants, and measured activities of the antioxidant enzymes SOD, GR, and CAT. Furthermore, mRNA and protein expression of a key molecular chaperone (Hsp70) involved in refolding of heat-damaged proteins was assessed to determine the potential relationship between antioxidant defense and protein quality control mechanisms during heat hardening in M. galloprovincialis.

Results

Mortality

At 24 °C, both hardened and non-hardened mussels exhibited no mortality (Fig. 1B). Temperature increase to 26 °C elevated mortality to 25–30% in the first 6 days of exposure. While non-hardened mussels exhibited 55% mortality after 10 days of exposure to 26 °C, the cumulative mortality of hardened mussels was lower, reaching 40% by day 15. At the highest tested temperature (28 °C), mortality of non-hardened mussels was 85% in the first week and 100% by day 10. The mortality of hardened mussels at 28 °C was 30% in the first 7 days and reached 60% by day 10 (Fig. 1B).

ETS activity

At 24 °C, there was a time-dependent decrease in ETS activity in both hardened and non-hardened mussels during 10 days of exposure (Fig. 2Aa). ETS activity levels were similar in hardened and non-hardened mussels at 24 °C, and did not significantly differ from the control levels in the mussels kept at 18 °C (Fig. 2Aa). Exposure to 26 °C resulted in a decrease of ETS activity on day 1 compared to the control (Fig. 2Ab). Thereafter, ETS activity levels increased in both experimental groups on day 3 but this increase was transient in the non-hardened mussels followed by a decrease on days 5–10, whereas in the hardened mussels the ETS activity continued to increase reaching significantly higher levels than in the non-hardened and control mussels on days 5 and 10 (Fig. 2Ab). At 28 °C, ETS activity of non-hardened mussels showed a transient increase after 12 h of exposure followed by a continual decrease throughout the exposure, so that after 1–10 days of exposure the ETS activity of non-hardened heat-stressed mussels were significantly below the baseline (control) levels (Fig. 2Ac). The hardened mussels exhibited increased ETS activity after 12 h and 1 day of 28 °C exposure followed by a decrease back to the baseline (control) levels (Fig. 2Ac). As a result, the ETS levels after 1–10 days of exposure at 28 °C were higher in the hardened compared with the non-hardened mussels.

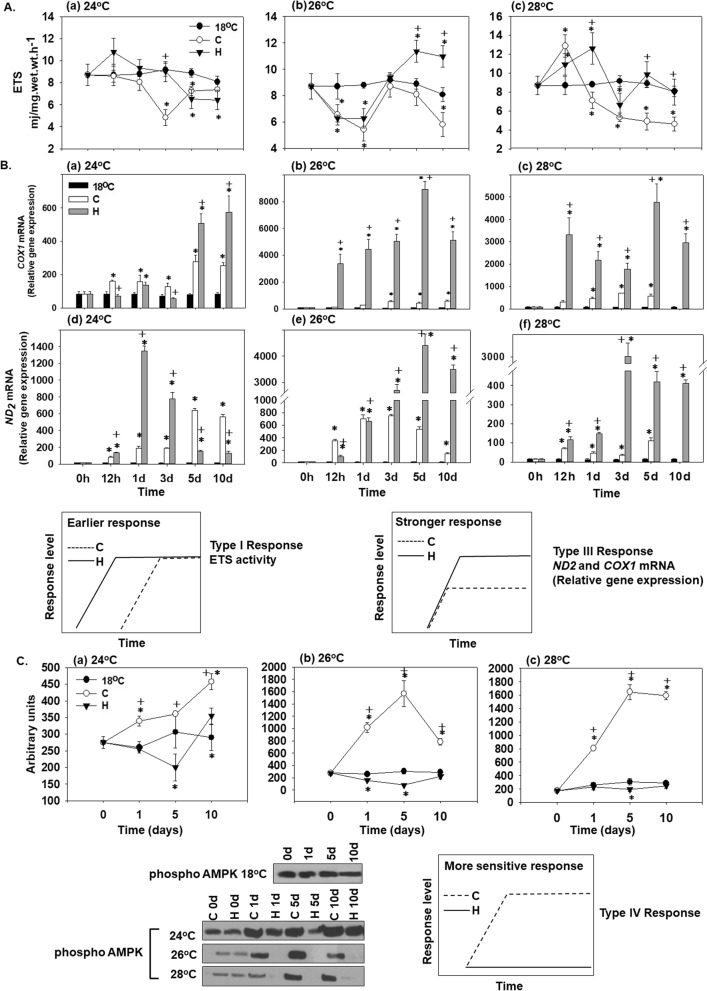

Figure 2.

Changes in (A) the ETS activity [Type I (earlier) response], (B) the relative COX1 and ND-2 mRNA levels [Type III (stronger) response] and (C) AMPK phosphorylation levels [Type IV (more sensitive) response] in the mantle of heat hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) Mytilus galloprovincialis when exposed to 24 °C (a,d), 26 °C (b,e) and 28 °C (c,f) compared to control at 18 °C. Representative blots are shown. Blots were quantified using scanning densitometry. Full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Values are means ± SD, n = 8 preparations from different animals. *p < 0.05 compared to day 0, +p < 0.05 compared to non-hardened (C) mussels.

Statistically significant differences were observed between hardened and non-hardened specimens. Main effects of treatment and exposure time, as well as factor interactions, were significant (p < 0.0001).

COX1 and ND2 gene expression

Elevated temperatures (24, 26 and 28 °C) caused increased COX1 and ND2 mRNA expression in hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) mussels from the 1st day of exposure compared to the baseline levels observed in the control mussels maintained at 18 °C (Fig. 2B). During early exposure (12 h–3 days) to 24 °C, COX1 mRNA expression was slightly but significantly higher in non-hardened mussels compared to their heat-hardened counterparts (Fig. 2Ba). On days 5 and 10 of exposure to 24 °C, COX1 mRNA levels were considerably higher in the hardened than in the non-hardened mussels (Fig. 2Ba). The mRNA levels of ND2 peaked at day 1 of exposure to 24 °C in the hardened mussels reaching significantly higher levels than in their non-hardened counterparts (Fig. 2Bd). Later during exposure to 24 °C, the levels of ND2 decreased in the hardened mussels whereas they continued to rise in non-hardened mussels so that on days 5 and 10 of exposure to 24 °C the ND2 transcript levels were higher in the non-hardened than hardened mussel. It is worth noting that in both hardened and non-hardened groups the COX1 and ND2 transcript levels were significantly higher than baseline (control) levels at all studied time points. At 26 °C and 28 °C, COX1 and ND2 mRNA expression levels were consistently and significantly higher in hardened (H) compared to non-hardened (C) mussels at all studied time points (Fig. 2Bb,c,e,f).

Statistically significant differences were observed between hardened and non-hardened specimens. Main effects of treatment and exposure time, as well as factor interactions, were significant (p < 0.0001).

AMPK phosphorylation

Protein expression levels of phosphorylated AMPK were statistically increased in non-hardened (C) mussels from the 1st day of exposure to elevated temperatures (24, 26 and 28 °C) compared to the baseline levels in the mussels kept at 18 °C. The hardened mussels (H) showed low expression levels of phosphorylated AMPK at elevated temperatures (24, 26 and 28 °C) that were consistently lower than in the non-hardened mussels, and often below the baseline levels found in the mussels kept at 18 °C (Fig. 2C).

Statistically significant differences were observed between hardened and non-hardened specimens. Main effects of treatment and exposure time, as well as factor interactions, were significant (p < 0.0001).

SOD mRNA expression and activity

CuSOD mRNA expression increased in hardened (H) mussels exposed to all three elevated temperatures (24, 26 and 28 °C) starting from 12 h of exposure (Fig. 3a–c). The expression levels of CuSOD mRNA dropped later on (during days 1–10) of heat exposure in the hardened mussels but remained statistically higher compared to non-hardened (C) mussels and those kept at 18 °C. A similar time course with an early (12 h) increase and subsequent decline in CuSOD mRNA was observed in the non-hardened (C) mussels albeit the transcript levels remained considerably lower than in the hardened mussels (except for 10 days at 28 °C) (Fig. 3a–c).

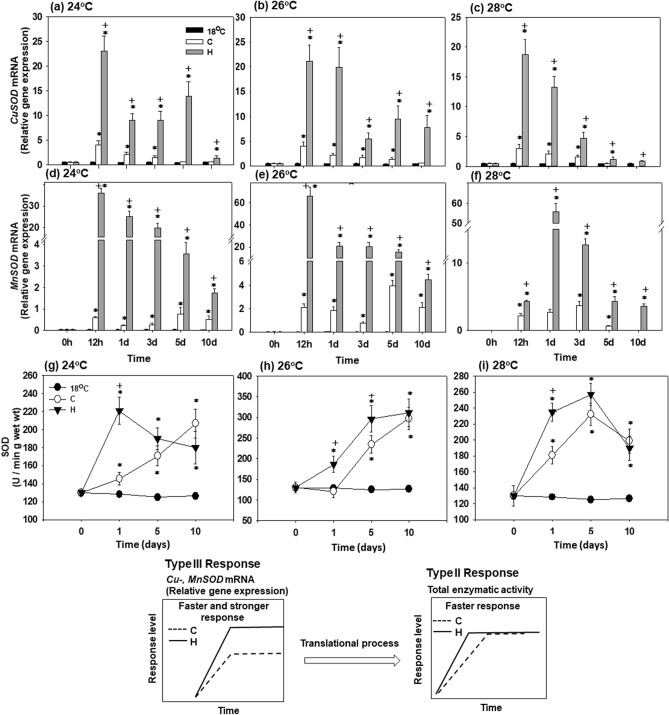

Figure 3.

Changes in the relative CuSOD and MnSOD mRNA levels [Type III (stronger) response], and SOD enzymatic activity [Type II (faster) response] in the mantle of heat hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) Mytilus galloprovincialis when exposed to 24 °C (a,d,g), 26 °C (b,e,h) and 28 °C (c,f,i) compared to control at 18 °C. Values are means ± SD, n = 8 preparations from different animals. *p < 0.05 compared to day 0, +p < 0.05 compared to non-hardened (C) mussels.

MnSOD mRNA expression in hardened (H) mussels peaked at 12 h at 24 °C and 26 °C, and at 1 day at 28 °C (Fig. 3d–f). The transcript levels of MnSOD decreased later during heat exposure in the hardened mussels (starting on day 1 at 24 °C and 26 °C, and day 3 at 28 °C) but remained statistically higher compared to non-hardened (C) mussels and those kept at 18 °C (Fig. 3d–f). In the non-hardened mussels, MnSOD mRNA levels increased later and to a lesser degree than in the hardened counterparts. Thus, at 24 °C and 26 °C, MnSOD transcript levels of non-hardened mussels increased significantly above the baseline on days 5 and 10 only (Fig. 3d,e). At 28 °C, the expression levels of MnSOD mRNA increased above the baseline already at 12 h of exposure, but the degree of stimulation was considerably lower than in the hardened mussels (Fig. 3f).

SOD enzymatic activity in the mantle of the hardened (H) mussels was elevated above the baseline starting on day 1 and remained elevated at days 5 and 10 of exposure to 24 °C (Fig. 3g). In non-hardened mussels the increase in the SOD enzymatic activity was slower with a mild (but statistically significant) increase above the baseline on day 1 and continual rise throughout the rest of the experimental exposure. As a result, SOD activities of both hardened and non-hardened groups reached similar levels at days 5 and 10 of exposure to 24 °C. At 26 °C and 28 °C (Fig. 3h,i), the dynamics of SOD activity changes were similar in the hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) mussels, except in non-hardened mussels at day 1 to 26 °C. An increase throughout the exposure period (at 26 °C) or an increase after days 1–5 was followed by a decrease at day 10 (at 28 °C). However, the amplitude of the increase in the SOD activity was higher in the hardened (H) compared to the non-hardened (C) mussels at 26 and 28 °C except for day 10 of the respective exposures (Fig. 3h,i).

Statistically significant differences were observed between hardened and non-hardened specimens. Main effects of treatment and exposure time, as well as factor interactions, were significant (p < 0.0001).

CAT mRNA expression and activity

In the hardened (H) mussels, CAT mRNA expression increased significantly above the baseline levels after 12 h of exposure at all tested temperatures (24, 26 and 28 °C) and remained strongly elevated until day 10 (Fig. 4a–c). In the non-hardened (C) mussels, transcriptional upregulation of CAT occurred later (at 28 °C) and/or to a lesser degree (at all three studied temperatures) than in their hardened counterparts. Transcript levels of CAT in heat-exposed hardened and non-hardened mussels were significantly above the baseline levels (measured in the mussels maintained at 18 °C) at all experimental temperatures and time points (Fig. 4a–c). Generally, transcriptional upregulation of CAT was higher in the hardened than in the non-hardened mussels except for 12 h, and 10 days at 26 °C where similar levels were attained in these two groups (Fig. 4b).

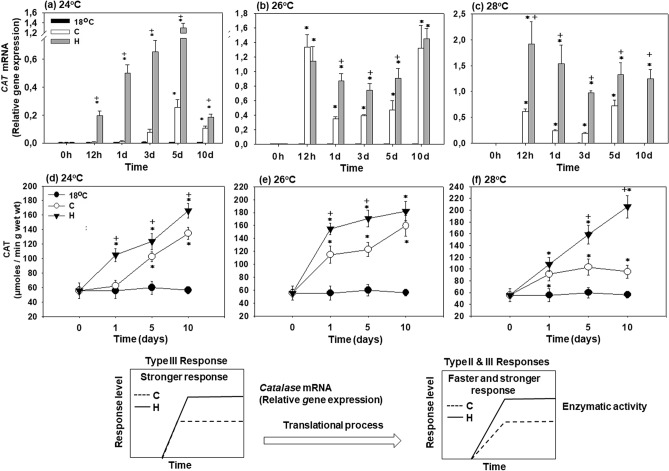

Figure 4.

Changes in the relative CAT mRNA levels [Type III (stronger) response] and CAT enzymatic activity [Type II & III (faster and stronger) responses] in the mantle of heat hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) Mytilus galloprovincialis when exposed to 24 °C (a,d), 26 °C (b,e) and 28 °C (c,f) compared to control at 18 °C. Values are means ± SD, n = 8 preparations from different animals. *p < 0.05 compared to day 0, +p < 0.05 compared to non-hardened (C) mussels.

In parallel with the mRNA expression, CAT enzymatic activity increased at all elevated temperatures (Fig. 4d–f). In the hardened (H) mussels, CAT activity continuously increased throughout the 10 days of exposures at 24, 26 and 28 °C. In the non-hardened (C) mussels, CAT activity increased during 10 days of heat exposure at 24 °C and 26 °C, whereas at 28 °C, a modest increase at days 1–5 of exposure was followed by a decrease at day 10 (Fig. 4f). In both hardened and non-hardened mussels, CAT activity during heat exposure was higher than the baseline measured in the mussels at 18 °C, and CAT activity was higher in the hardened compared to the non-hardened mussels (Fig. 4d–f).

Statistically significant differences were observed between hardened and non-hardened specimens. Main effects of treatment and exposure time, as well as factor interactions, were significant (p < 0.0001).

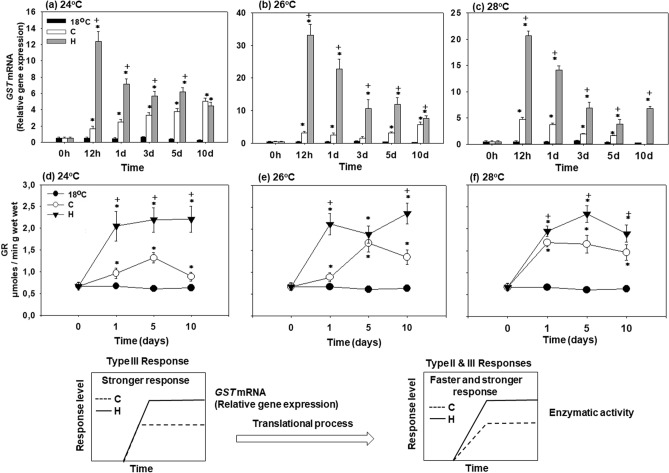

GST mRNA expression

GST mRNA expression of hardened (H) mussels strongly increased after 12 h of exposure to elevated temperatures (24, 26 or 28 °C), and decreased afterwards while remaining significantly above the baseline levels (measured in the non-exposed mussels at 18 °C) at all experimental time points (Fig. 5a–c). In the non-hardened mussels, a significant transcriptional upregulation of GST above the baseline levels was observed at day 1 (24 °C), day 5 (26 °C) and 12 h (28 °C) (Fig. 5a–c). At 24 °C and 26 °C, GST mRNA expression increased continuously in non-hardened (C) mussels throughout 10 days of experimental exposure (Fig. 5a,b). At 28 °C, GST mRNA expression peaked after 12 h and decreased afterwards reaching basal levels after 10 days of exposure (Fig. 5c). At all test temperatures, GST mRNA expression in hardened (H) mussels was significantly higher compared to the non-hardened (C) ones throughout the experimental exposure (Fig. 5a–c).

Figure 5.

Changes in the relative GST mRNA levels [Type III (stronger) response] and GR enzymatic activity [Type II & III (faster and stronger) responses] in the mantle of heat hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) Mytilus galloprovincialis when exposed to 24 °C (a,d), 26 °C (b,e) and 28 °C (c,f) compared to control at 18 °C. Values are means ± SD, n = 8 preparations from different animals. *p < 0.05 compared to day 0, +p < 0.05 compared to non-hardened (C) mussels.

Statistically significant differences were observed between hardened and non-hardened specimens. Main effects of treatment and exposure time, as well as factor interactions, were significant (p < 0.0001).

GR enzymatic activity

GR activity increased in hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) mussels during exposure to elevated temperatures compared with baseline levels found in mussels kept at 18 °C (Fig. 5d–f). In the hardened mussels, the GR activity increased on day 1 and remained elevated during 10 days of experimental exposure (Fig. 5d–f). In the non-hardened mussels, an initial increase of GR activity (on day 5 at 24 °C and 26 °C, and on day 1 at 28 °C) was followed by a decrease later during exposures (Fig. 5d–f). At all experimental time points, GR activity in the hardened mussels was higher than in their non-hardened counterparts (Fig. 5d–f).

Statistically significant differences were observed between hardened and non-hardened specimens. Main effects of treatment and exposure time, as well as factor interactions, were significant (p < 0.0001).

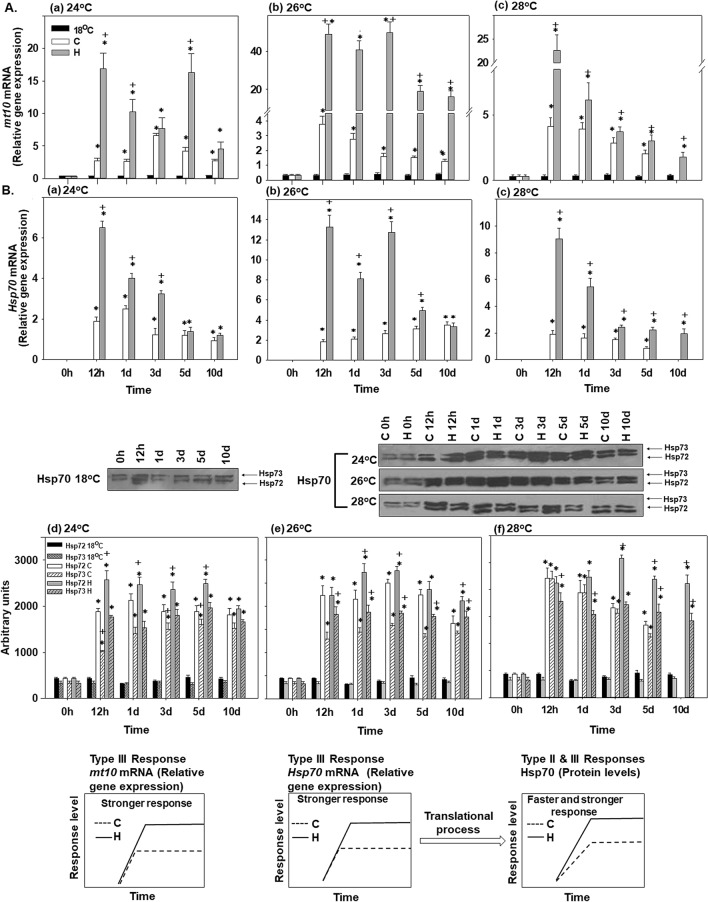

Metallothionein-10 (mt-10) gene expression

Transcript levels of mt-10 increased above the control (18 °C) baseline at all experimental temperatures in the hardened and non-hardened mussels (Fig. 6Aa–c). The amplitude of this increase was consistently higher in the hardened mussels compared with their non-hardened counterparts at all experimental time points. At 28 °C, mt-10 expression levels decreased gradually during the prolonged exposures; this tendency was not observed at 24 °C or 26 °C (Fig. 6Aa–c).

Figure 6.

Changes in (A) the relative metallothionein-10 mRNA levels [Type III (stronger) response] and in (B) the relative Hsp70 mRNA levels [Type III (stronger) response], and Hsp72 and 73 levels [Type II & III (faster and stronger) responses] in the mantle of heat hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) Mytilus galloprovincialis when exposed to 24 °C (a,d), 26 °C (b,e) and 28 °C (c,f) compared to control at 18 °C. Representative blots are shown. Blots were quantified using scanning densitometry. Full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. Values are means ± SD, n = 8 preparations from different animals. *p < 0.05 compared to day 0, +p < 0.05 compared to non-hardened (C) mussels.

Statistically significant differences were observed between hardened and non-hardened specimens. Main effects of treatment and exposure time, as well as factor interactions, were significant (p < 0.0001).

Hsp70 mRNA and protein expression

Hsp70 mRNA was upregulated to above control (18 °C) baseline levels at all experimental temperatures in the hardened and non-hardened mussels (Fig. 6Ba, b, c). The amplitude of this increase was higher in the hardened mussels than in the non-hardened mussels during the earlier stages of response to heat stress at 24 °C (days 1–3) and 26 °C (days 1–5) (Fig. 6Ba,b) and at all experimental time points at 28 °C (Fig. 6Bc). There was a decrease in Hsp70 mRNA during the later stage of experimental exposures (5–10 days at 24 °C, 10 days at 26 °C and 3–10 days at 28 °C) in the hardened mussels but not in their non-hardened counterparts (Fig. 6Ba–c).

Protein levels of the two detected Hsp70 isoforms (Hsp73 and Hsp72) increased during the first 12 h of experimental exposures and remained elevated throughout 10 days at 24, 26 and 28 °C (Fig. 6Bd–f). This pattern was found in both hardened (H) and non-hardened (C) mussels. In general, the hardened (H) mussels showed higher levels of Hsp73 and Hsp72 compared to non-hardened (C) mussels at all exposure temperatures.

Statistically significant differences were observed between hardened and non-hardened specimens. Main effects of treatment and exposure time, as well as factor interactions, were significant (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

Bioenergetics

Our present work demonstrates enhanced thermotolerance in heat hardened M. galloprovincialis as shown by their improved survival during heat exposure (particularly at the lethal temperature of 28 °C) compared to the non-hardened mussels. The enhanced thermotolerance of heat hardened mussels could in part be attributed to improved mitochondrial respiration as indicated by increased ETS activity, and elevated levels of the transcripts encoding mitochondrial ETS subunits ND2 and COX1 at the higher tested temperatures (26 °C and 28 °C). Notably, the dynamics of the heat-induced changes in the transcript levels and the ETS activity appear synchronized in the hardened mussels. Thus, the ETS activity, as well as ND2 and COX1 expression, peaked at day 5 of exposure at 26 °C in the hardened mussels. At 28 °C, an initial increase in ETS activity at 12–24 h was followed by a decline by day 3, and the second peak at day 5 was mirrored in the COX1 transcript levels in the hardened mussels. In the non-hardened mussels, ND2 and COX1 mRNA levels, and ETS activity remained considerably lower than in the hardened mussels at 26 °C and 28 °C, and the dynamics of the enzymatic activity and transcriptional response was de-synchronized. Enhanced mitochondrial activity in the hardened mussels might help with ATP provision to cover high energy demand due to the rate-enhancing (Q10) effects of warming on the cellular ATP consumers, thereby mitigating the heat-induced energy stress and supporting energy homeostasis9. Other changes to mitochondrial characteristics remain to be investigated.

Despite a strong upregulation of ND2 and COX1 mRNA expression at 24 °C in hardened, as well as non-hardened mussels, the ETS activity decreased below baseline (18 °C) levels in both studied groups at this temperature. This implies predominant involvement of post-transcriptional mechanisms in regulation of ETS activity at 24 °C such as post-translational modifications of mitochondrial proteins37. Alternatively, the observed decrease in ETS activity at 24 °C might reflect damage to the mitochondria due to the elevated temperature. This explanation appears less likely because such decrease is not observed at higher temperatures (26 °C and 28 °C), at least not in the hardened mussels. Overall, moderate heat stress (24 °C) has a weak impact on the ETS activity in both experimental groups with no apparent beneficial effects of heat hardening. In contrast, warm acclimation may occur, removing excess mitochondrial capacity, as observed earlier across many ectotherms38. Furthermore, exposure to 24 °C does not induce elevated mortality in the hardened or non-hardened mussels. These findings indicate that 24 °C falls within the pejus (rather than the pessimum) temperature range for the studied population of M. galloprovincialis3,8,9.

On the other hand, an increase in ETS activity beyond the control levels of non-hardened mussels after the third day of exposure at sublethal temperatures is strong evidence for enhanced oxygen delivery, resulting in elevated aerobic capacity and ATP synthesis, indicating an upward shift of thermal limits and accordingly, oxygen supply during heat acclimation. The importance of ATP homeostasis in marine bivalves for defense against thermal stress has been extensively discussed by Sokolova8,9. Conversely, it has been pointed out that anaerobiosis is linked with lower thermotolerance capacity, which is correlated to internal hypoxia within heat stressed animals, i.e. OCLTT hypothesis4,6. Accordingly, thermally induced mortality in Mytilus edulis (Linnaeus, 1758) was related to a sharp increase in mantle succinate indicating insufficient oxygen reaching mitochondria39. Dunphy et al.40 reported that succinic acid levels were significantly higher in naïve compared to heat-hardened mussels, indicating mitochondrial perturbations. We did not determine the ATP levels in the present work, while the patterns of intermediate metabolism in hardened M. galloprovincialis are under investigation. However, the phosphorylation of AMPK, and hence activation, indicates lower heat sensitivity in hardened compared to non-hardened mussels. AMPK is considered a sensor of cellular energy status and its phosphorylation is stimulated by several factors including hypoxia which causes elevation in AMP/ATP ratio, indicating disturbance in ATP homeostasis41. The absence of AMPK phosphorylation in the hardened mussels when exposed to sublethal temperatures is additional strong evidence for the maintenance of energetic potential and probably enhanced aerobic capacity supporting heat hardening.

From integrating the increase in ETS activity and the shifted level and timing of antioxidant stress responses, we also suggest that such an adaptive response benefits mussel thermotolerance and acclimation to heat. In accordance with the above adaptive cellular responses, Hsp70 mRNA expression and Hsp73 and Hsp72 levels are significantly increased during hardening near sub-lethal temperatures, thus further contributing to the protein stabilization needed for increased thermal tolerance. The induced Hsp72 isoform may act as a regulator against subsequent thermal stress and supports thermal protection42. These results are in line with the sharp increase in the relative Hsp70 and Hsp90 mRNA expression levels of mussels exposed to 22 °C, indicating their ability to sense thermal stress, even before the respective cellular processes are initiated36. In both groups of mussels, an increased capacity of ATP synthesis at 26 °C is prerequisite for the observed elevation of Hsp synthesis as a highly energy demanded process. Furthermore, according to the OCLTT hypothesis, the HSR is most commonly observed at the organism’s critical temperatures (where survival rates are still high)4,6 and at which the released Hsp70, binds to the increased denatured and erroneously ordered proteins, while HSF is free to activate the Hsp genes43,44.

Oxidative stress

Mitochondrial thermal stress commonly suppresses OXPHOS and ETS activity and elevates electron leak resulting in ROS production. These changes can result in energy deficiency due to the mismatch between cellular ATP demand and mitochondrial ATP generation, and lead to oxidative injury if the antioxidant system cannot cope with the increased ROS production7,13. The existing protective mechanisms sufficiently deal with moderate stress (24 °C). Even though hardening increases the expression and activity of some antioxidants and Hsps at 24 °C, this does not appear to provide benefits in terms of aerobic capacity and organismal survival but may reflect thermal acclimation. In molluscs, including M. galloprovincialis, valve closure can serve as a behavioral mechanism that regulates the metabolic response by suppressing both aerobic respiration (and ROS production) and energy expenditure under unfavorable conditions35,45,46. Thus, thermally stressed M. galloprovincialis mussels keep their valves closed for a longer period, resulting in reduced oxygen consumption, hypometabolism, and activation of anaerobic metabolism35,46. In a recent investigation, we have discussed the relationship between ROS production and metabolic patterns in M. galloprovincialis in a hypometabolic state when exposed to 24 °C, 26 °C and 28 °C36. In line with other studies47–50, the correlation between succinate accumulation, changes in complex II in the respiratory chain, and in ROS production in mitochondria has been underlined. It has been proposed that this complex pattern switches the catalytic activity from succinate dehydrogenase to fumarate reductase at diminished oxygen levels. This transition is also the main step towards succinate accumulation in mussels under hypoxia/anoxia51. Importantly, Gracey and Connor52 showed that valve closure caused bradycardia in M. californianus, accompanied by accumulation of succinate, induction of several transcription factors, broadly classified as early genes (activated and transcribed within minutes of various stimuli), and isoforms of carbonic anhydrase, consistent with the association between anaerobic metabolism and tissue acidosis. During prolonged thermally induced hypoxic exposure, however, anaerobic degradation of glycogen to alternative anaerobic end products, such as acetate and propionate, could be considered another major adaptive mechanism that contributes to longer survival during sustained environmental hypoxia53–57.

In mitochondria, ROS are produced by Complex I and the NADH dehydrogenase component of the mitochondrial matrix side, and are detoxified by the antioxidant defense in the matrix35. The hypometabolic state (e.g. induced by valve closure) is characterized by reduced Krebs cycle rate and limits the supply of NADH to mitochondrial Complex I. The limited oxidation of NADH via Complex I may suppress the electron transfer through the ETS under thermal stress and contribute to the metabolic depression and low ROS production in the hardened and non-hardened mussels. Tomanek and Zuzow58 have shown that metabolic patterns during thermal stress are involved in the putative switch from NADH- to NADPH producing pathways in mussels. Changes in NADP+-dependent mitochondrial IDH and pentose–phosphate pathway suggest that there is a NADPH up-regulation in response to heat stress, while other changes in the Krebs cycle and the ETS suggest that the production of NADH is decreasing at the highest temperature. In line with the above hypothesis, Ramnanan and Storey59 reported that estivation-induced phosphorylation by G6PDH may enhance NADPH production for use in antioxidant defense. Also, Lama et al.60 showed that G6PDH is enhanced during anoxia in Littorina littorea (Linnaeus, 1758), possibly in an effort to produce NADPH reducing equivalents for use in the antioxidant defense.

The voluntary switch to anaerobiosis in bivalves may serve as a mechanism which reduces ROS formation, thus resulting in longer survival8,45,52. The latter in conjunction with the early gene expression of antioxidant enzymes36 may contribute to the dynamic equilibrium between ROS production and detoxification. The expression of both CuSOD and MnSOD genes indicates that both forms are involved in the mitochondrial reduction of superoxide (O2.−) to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is then detoxified by CAT, while GR detoxifies endogenous compounds, including peroxidized lipids. Under hypoxic conditions, expression of GST mRNA is increased in M. galloprovincialis due to oxidative stress61. The mechanisms modulating gene expression for the antioxidant enzymes in molluscs as a response to ROS accumulation during temperature-induced hypometabolism, seem to involve several transcription factors targeted by members of MAPKs including ERKs, JNKs, and p38 MAPK14,49. Nevertheless, the physiological role of ND2 and COX1 genes expression remains unclear after the third day of non-hardened mussel exposure to 24 °C. Since such a response is not followed by a concomitant increase in ETS activity, we could suggest that this response is a component of the "preparatory strategy" enabling mussels to strengthen their defense against higher intensities of subsequent thermal episodes62.

The above mentioned molecular and metabolic processes are reversed when mussels are exposed at temperatures beyond 26 °C which causes a more active metabolic response. Specifically, relative mRNA levels did not differ between non-hardened and hardened mussels during the first day of exposure to 26 °C, while further exposure, caused stronger gene expression in the hardened mussels compared to non-hardened ones, maintaining high mRNA levels by the 10th day. A similar pattern was observed when mussels were exposed to 28 °C. The above data clearly indicate a phenotypic change in the transcription in the ND2 and COX1 genes, which probably enhances the potential for mitochondria respiration compared to control (18 °C) and non-hardened mussels especially when exposed to 26 °C. In line with the above gene responses is the longer thermal acclimation and delayed mortality of mussels. However, such a molecular response cannot by itself explain longer survival after heat-shock and hardening, unless it is related to an enhanced oxidative defense or decreased proton leak and hence reduced ROS production. Furthermore, we should point out that the beneficial effects of hardening seem to take place after the third day of exposure to sublethal temperatures, a fact coinciding well with the deceleration in the mortality rate of mussels. Consequently, the question raised is which cellular mechanisms are involved in the increase of thermal tolerance in the hardened mussels when exposed to subthelal temperatures beyond 26 °C. First, the more efficient (faster and higher) antioxidant defense against increased ROS production in heat hardened compared to non-hardened mussels could be partly the answer to the above question. In both cases (non-hardened and hardened mussels), all genes for antioxidant enzymes indicate a strong response. However, the enzymatic activities seem to exhibit different kinds of responses. Specifically, SOD total enzymatic activity exhibited a faster but not stronger response. On the contrary, CAT and GR exhibited faster and stronger responses, indicating a higher capacity in hardened mussels for scavenging redundant ROS compared to non-hardened. The latter may be of crucial importance in oxidative defense which is enhanced during hardening thus enabling mussels to develop higher thermotolerance and lower mortality. In line with the GST and CAT mRNA expression, the stronger mt-10 gene transcription in hardened M. galloprovincialis further supports the increased defense and tolerance of heat hardened mussels against thermal stress. Giannetto et al.11 reported a cytoprotective role in the physiological oxidative stress response of mt-10 and mt-20 in M. galloprovincialis. The family of mt genes demonstrates enhanced expression in many organisms after heat shock treatment63–65, suggesting a relationship between HSR and mt gene expression66.

Acquired stress memory

Overall, the acquired thermal stress resistance or as it is sometimes called "acquired stress memory", is a phenomenon in which cells exposed to a mild dose of one stress can subsequently survive an otherwise lethal dose of the same or a second stress. There are several reports on the beneficial effects of this adaptive response on the thermal tolerance of several mollusc species, including the Asian green mussel Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758)67, blue mussel M. edulis68 and New Zealand green-lipped mussel Perna canaliculus (Gmelin, 1791)40. Moreover, warm preconditioning seems to protect against acute heat-induced respiratory dysfunction and delays bleaching in a symbiotic sea anemone69. Also, Wesener and Tietjen70 showed that independently of stress type and priming costs, the stronger primed response is most beneficial for longer stress phases of several microbial species, while the faster and earlier responses increase population performance and survival probability under short stresses. On the other hand, Pereira et al.71 reported that early exposure of oyster species to heat shock had little effect on the amelioration of increased temperature’s negative effects, although the survival of heat-shocked oysters was greater than non-heat shocked ones. The cellular mechanisms involved in acquired stress resistance are not known. Krebs and Loeschcke72 reported for Drosophila melanogaster (Meigen, 1830) that the acclimation to heat stress may be owed in part to the presence of large numbers of mRNA transcripts for heat-shock proteins or to the presence of the specific stress proteins. In yeast, this acquired stress resistance depends on protein synthesis during mild-stress treatment and requires the “general-stress” transcription factors that regulate induction of many environmental stress response genes73. In line with the above assumption, Horowitz30,31 reported that cells respond to extra- and intra- cellular signals by changing gene expression patterns which seem to play important roles in acclimation and that the long-term physiological responses to acclimation are determined by the molecular programs that induce the acclimated transcriptome. However, some investigations focused on the importance of the initial temperature stress which dictates the recovery time (through activation of CSR), along with the duration of the changes (i.e. a highly activated CSR may have led to more permanent changes within the cells that led to a longer-lasting heat tolerance)62,74. Also, the number of heat-shock bouts that an organism experiences at sublethal temperatures may determine largely how long this organism can tolerate extreme temperatures74,75. In this prism, Connor and Gracey75 reported that M. californianus exhibits phenotypic plasticity with respect to transcriptomic expression during cycles of aerial exposure and that it may produce a type of “heat hardening”, thus promoting homeostasis in the intertidal environment and enhanced tolerance to low-tide heating events. Moyen et al.34 recently reported that this adaptive strategy via phenotypic plasticity will likely prove beneficial for M. californianus and other mussel species under the extreme heat events projected with progressing climate change.

Materials and methods

Animals

The mussels M. galloprovincialis with a total mass of 25.82 ± 4.62 g (mean ± SD), shell length 6.42 ± 0.47 cm and shell width 3.2 ± 0.15 cm, were collected from a mussel farm located in Thermaikos Gulf, Greece (Dramouslis LTD) in late April, when the ambient sea water temperature was approximately 18 °C. Mussels were transferred to the Laboratory of Animal Physiology, Department of Zoology, School of Biology of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and kept in 1000 l tanks with recirculating aerated natural seawater for 1 week. Water temperature was controlled at 18 °C ± 0.5, while salinity was kept at 34‰ ± 2.85 and pH at 8.12 ± 0.05, respectively. Mussels were kept under 14/10 h light–dark photoperiod, in order to mimic the field conditions when the mussels were collected. Mussels were fed daily with 0.5% dry weight cultured microalgae Tisochrysis lutea (CCAP 927/14)/gr total weight of mussels. 60% of water was replaced every 2 days with filtered seawater.

Experimental procedures

The experimental exposures were conducted in two phases (heat hardening and acclimation phases) as described below. During hardening and acclimation phases, mussels were not fed.

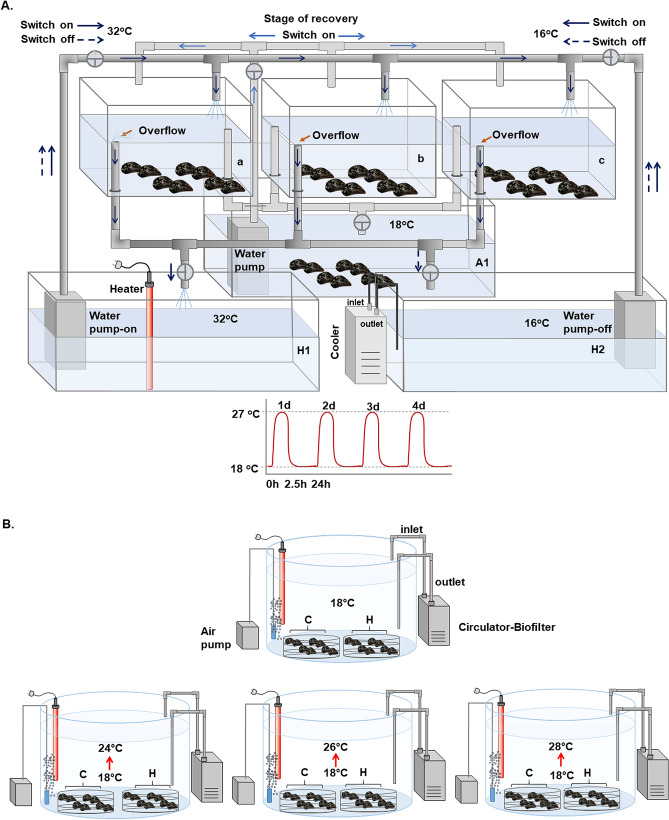

Heat-hardening phase

Experimental design for heat hardening exposures was based on Hutchison's 76 "Repeated—CTM" method, with minor modifications (Fig. 7A). Specifically, ~ 300 randomly selected mussels were divided and conditioned in three aquaria each containing 100 l aerated sea water at 18 °C (a, b and c). The sea water was recirculated via pipes connected to a 500 l tank (A1) maintained at 18 °C. Mussels were kept at 18 °C for 1 week. To determine whether a single sublethal heat-stress bout would confer improved heat tolerance during a subsequent more extreme (potentially lethal) heat-stress exposure, mussels were given a sublethal heat-stress bout of 2.5 h at 27 °C. We have shown in previous works that mortality of M. galloprovincialis increases significantly after exposure to 27 °C35,36. The studied populations of mussels currently experience similarly high temperatures (27–28 °C) in the field during summer. It has been reported that during the last decades, there has been a continuous temperature increase in the Mediterranean Sea, which is expected to rise further in the near future77,78. These climate projections for Mediterranean and Aegean seas include also an increased intensity in the frequency of the heat waves with temperatures exceeding 27 °C. Consequently, the experimental design aimed to simulate the projected changes in sea water temperature in the area under study. To increase the sea water temperature in exposure tanks (a, b, and c on Fig. 7A), water flow was switched to a heater tank containing sea water at 32 °C (H1). As reported elsewhere, this treatment permits organismal temperature to rise without time lag79. Once temperature reached 27 °C, the water flow from tank H1 was stopped and the mussels were exposed to 27 °C for 2.5 h. Thereafter, the water flow was switched to tank H2 containing sea water at 16 °C that permitted a quick drop of the water temperature in exposure tanks (a, b and c) to 18 °C. Afterwards, water flow stopped, and mussels were left to recover at 18 °C for 24 h. This heat-stress bout (including the thermal shock and recovery phase) was repeated four times. The mussels exposed to this treatment are later called heat-hardened mussels. Control mussels were maintained in three aquaria (each containing 100 l aerated sea water) at 18 °C during this time.

Figure 7.

(A) Mussels’ hardening phase: tanks with fully aerated water at 18 °C were connected with switches with two other tanks, one with increased (32 °C) and the other with decreased (16 °C) water temperature in order to regulate the water temperature to increased (27 °C) or decreased (18 °C—control) temperatures. (B) Mussels’ acclimation phase: transfer of all (hardened and non-hardened) individuals in tanks with recirculating aerated natural seawater at 18 °C and consequent increase at 24 °C, 26 °C and 28 °C.

Acclimation phase

After the completion of heat-hardening treatments, both control (non-hardened) mussels (group C) and hardened mussels (group H) were transferred to four 500 l tanks (50–60 individuals from each group per tank) with recirculating aerated natural seawater at 18 °C and left to recover for four days. Group C and group H mussels were placed respectively in different baskets within each tank. Thereafter, water temperature of the three tanks was increased (1 °C/h) to 24, 26 and 28 °C, respectively. As reported elsewhere, this treatment permits organismal temperature to simultaneously rise with the test temperature without time lag79. Mussels maintained in the fourth tank were kept at 18 °C and used as controls (Fig. 7B). All different tanks were run in triplicates.

Tissue sampling and water quality monitoring

Individuals (n = 8 at each time point) from hardened and non-hardened groups were collected from each tank at 12 h, 1, 3, 5 and 10 days after the target temperature (24, 26 or 28 °C) was reached. As we have reported elsewhere36, mantle exhibited higher aerobic capacity and more intense physiological stress response compared to PAM. Therefore, the mantle was removed, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for later analysis.

Physicochemical water parameters (Table 1) were measured daily as follows: salinity (g l−1), O2 (mg l−1) and pH by using Consort C535, Multiparameter Analysis Systems (Consort, bvba, Turnhout, Belgium) while NH3 (μg l−1), NO2− (μg l−1) and NO3− (μg l−1) were analyzed by using commercial kits by Tetra (Tetra Werke, Melle, Germany).

Table 1.

Mean values of sea water parameters.

| Temperature (oC) | Salinity (g l−1) | pH | O2 (mg l−1) | NH3 (mg l−1) | NO2− (mg l−1) | NO3− (μg l−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 °C | 18 ± 0.1 | 33.2 ± 0.03 | 8.04 ± 0.02 | 7.9 ± 0.06 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | < 12.5 |

| 24 °C | 24 ± 0.3 | 33.4 ± 0.03 | 8.03 ± 0.02 | 7.8 ± 0.07 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 14 ± 0.6 |

| 26 °C | 26 ± 0.4 | 33.3 ± 0.01 | 8.02 ± 0.01 | 7.8 ± 0.05 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 14 ± 0.3 |

| 28 °C | 28 ± 0.3 | 33.2 ± 0.04 | 8.02 ± 0.01 | 7.8 ± 0.07 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 13 ± 0.5 |

Sea water parameters as measured in all experimental conditions. Values are presented as means ± SD (n = 10).

Analytical procedures

SDS/PAGE and immunoblot analysis

The preparation of tissue samples for SDS-PAGE and the immunoblot analysis are based on well-established protocols (e.g.35). In the present study, equivalent amounts of proteins (50 μg per sample) were separated on 10% and 0.275% (w/v) acrylamide and bisacrylamide slab gels and transferred electrophoretically onto nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 μm, Schleicher and Schuell, Keene N. H. 03431, New Hampshire USA). The nitrocellulose membranes were stained with Ponceau dye to assure good transfer quality and equal protein loading. Antibodies used were monoclonal anti-phospho AMPK (2535, Cell Signaling, MA Beverly, USA) and monoclonal Anti-Heat Shock Protein 70 (H5147, Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany).

Determination of activities of antioxidant enzymes in the tissue homogenates

Crude extracts for determination of the activities of antioxidant enzymes were obtained as described in Salach80. Briefly, the frozen mantle tissues were homogenized in ice-cold phosphate buffer (50 mM), adjusted to pH 7.4, using an Omni international homogenizer (Thane, USA) at 22,000 rpm for 20 s. The homogenates were centrifuged at 2000g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatants were freeze-thawed thrice to fully disrupt the organelle membranes and centrifuged at 6000g at 4 °C for 15 min. The resulting supernatants were used for assaying the activities of antioxidant enzymes. SOD (total activity of mitochondrial Mn- and cytosolic Cu/Zn-SOD, SOD EC 1.15.1.1) was assayed by monitoring the inhibition of NADH oxidation using β-mercaptoethanol in the presence of EDTA and Mn as a substrateas described in Paoletti and Mocali81. The changes in the absorbance of NADH at 340 nm per min were determined (ε = 6.22 mM−1 cm−1). CAT Vmax (CAT, EC 1.11.1.6) was determined following the changes in the absorbance of H2O2 at 240 nm (extinction coefficient ε = 0.0394 mM−1 cm−1) according to Cohen et al.82. GR Vmax (GR, EC 1.8.1.7) was determined by a NADPH-coupled assay according to Carlberg and Mannervik83, following the changes in the absorbance of NADPH (ε = 6.22 mM−1 cm−1). All enzymatic activities were determined at 18 °C using a Hitachi 150–20 recording spectrophotometer with water-jacketed cell. The Vmax of the enzymes was expressed as units per gram of wet tissue mass.

Determination of ETS activity

ETS activity was determined according to Haider et al.84. Briefly, 10 mg powdered tissue was added to 500 µl homogenizing buffer (Tris–HCl 0.1 M, poly vinyl pyrrolidone 0.15% (w/v), MgSO4 153 µM, Triton X-100 0.2% (w/v); adjusted to pH 8.5). After centrifugation (3000g, 4 °C, 10 min), 28.5 µL from each extract was added to 85.5 µL buffered substrate solution (Tris–HCl 0.13 M and Triton X-100 0.3% (w/v); adjusted to pH 8.5) and 29 µL NAD(P)H solution (NADH 1.7 mM and NADPH 250 µM). For blank readings, NAD(P)H solution was replaced with 27 µL of 5 M KCN and 2 µL of 1 mM rotenone. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 57 µL of 8 mM iodonitrotetrazolium (INT). Absorbance was measured at 18 °C for 10 min at 490 nm. The ETS activity was calculated from the rate of the formazan formation using ɛ490 nm = 15,900 M−1 cm−1 and a stoichiometry of 1 µmol of O2 to 2 µmol of formazan.

Determination of mRNA expression

For estimation of mRNA expression profiles, a quantitative real-time PCR was performed. Total RNA was isolated from homogenized mantle tissue using Tri-Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 100–150 ng RNA was utilized for first strand cDNA synthesis using the PrimeScript kit (Takara, Gunma, Japan) and the oligodT primers. With the use of the Sensi-FAST SYBR No-ROX mixture (Bioline, London, UK) in a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR thermocycler, the mRNA levels of the target genes were determined including COX1, NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND-2), hsp70, mt-10, GST, Mn superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase(Cu/Zn-SOD), and CAT (cat). Primers used for amplification of the aforementioned genes were as described in Feidantsis et al.36 except for COX1 and ND-2 which were described in Woo et al.61. The actin gene, used as reference, was amplified using the primers actin-F and actin-R (Accession No: AF157491). The sequences of used primers are shown in Table 2. Relative quantification was achieved by comparing the cycle threshold values (CT) of the target genes with the CT values of the actin using the ΔΔCT quantification algorithm.

Table 2.

Primers used for the estimation of gene expression profiles.

| Gene | Sequence | Amplicon size | Accession number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COX1 F | 5′-GTGTCTTCTTATGGGTCTG-3′ | 211 | FJ890849 | Woo et al. 61 |

| COX1 R | 5′-GCTATAAACATGCTTTCTCC-3′ | |||

| ND2 F | 5′-TGGTGTTTTCCTCTACACTC-3′ | 210 | FJ549901 | Woo et al. 61 |

| ND2 R | 5′-AGGGTCTTATTACCCGCACT-3′ | |||

| Actin F | 5′-CGACTCTGGAGATGGTGTCA-3′ | 153 | AF157491 | Moreira et al. 85 |

| Actin R | 5′-GCGGTGGTTGTGAATGAGTA-3′ |

Statistics

Changes in Hsp70 levels, ETS activity, antioxidant enzymes activities and relative mRNA expressions were tested for significance at the 5% level (p < 0.05) by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (GraphPad Instat 3.0) for statistically significant differences between examined groups and two-way (GraphPad Prism 5.0) analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the significance of factors tested each time, with sampling days and treatment as fixed factors. Post-hoc comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni test. Values are presented as means ± S.D.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- AMPK

AMP activated protein kinase

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- CAT

Catalase

- G6PDH

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- CSR

Cellular stress response

- CTM

Critical thermal maxima

- CuSOD

Cu superoxide dismutase

- COX1

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1

- ETS

Electron transport system

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GR

Glutathione reductase

- GST

Glutathione S-transferase

- HSF

Heat shock factor

- Hsp70

Heat shock protein

- HSR

Heat shock response

- IDH

Isocitrate dehydrogenase

- NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- ND2

NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2

- NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- mt10

Metallothionein 10

- MnSOD

Mn superoxide dismutase

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation

- OCLTT

Oxygen and capacity limited thermal tolerance

- PAM

Posterior adductor muscle

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- Mn

Manganese

Author contributions

I.G. and B.M. designed the study; I.G., K.F. and I.A.G. collected the animals; I.G., K.F. and A.K. performed the experiments. I.G., K.F., I.A.G. and A.K. carried out the application of biochemical and molecular biomarkers and statistically analyzed the results. I.G., K.F. and I.S. wrote the manuscript. I.A.G. and B.M. provided the funding. C.B, H.O.P. and B.M. revised the manuscript and supervised the study.

Funding

This research has been co-financed by the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call Special Actions AQUACULTURE–INDUSTRIAL MATERIALS–OPEN INNOVATION IN CULTURE (project code: T6YBΠ-00388; Project acronym: SmartMussel).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-96617-9.

References

- 1.Hochachka PW, Somero GN. Biochemical Adaptation: Mechanism and Process in Physiological Evolution. Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pörtner, H. O. et al. Ocean systems. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 411–484 (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- 3.Pörtner HO. Climate impacts on organisms, ecosystems and human societies: Integrating OCLTT into a wider context. J. Exp. Biol. 2021;224:jeb238360. doi: 10.1242/jeb.238360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pörtner HO. Oxygen- and capacity-limitation of thermal tolerance: A matrix for integrating climate-related stressor effects in marine ecosystems. J. Exp. Biol. 2010;213:881–893. doi: 10.1242/jeb.037523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pörtner HO, Farrell AP. Ecology: Physiology and climate change. Science. 2008;322:690–692. doi: 10.1126/science.1163156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pörtner HO, Peck LS, Somero GN. Mechanisms defining thermal limits and adaptation in marine ectotherms: an integrative view. In: Rogers AD, Johnston NM, Murphy EJ, Clarke A, editors. Antarctic Ecosystems: An Extreme Environment in A Changing World. 1. Blackwell Publishing; 2012. pp. 360–396. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abele D, Heise K, Pörtner HO, Puntarulo S. Temperature-dependence of mitochondrial function and production of reactive oxygen species in the intertidal mud clam Mya arenaria. J. Exp. Biol. 2002;205(13):1831–1841. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.13.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sokolova I. Bioenergetics in environmental adaptation and stress tolerance of aquatic ectotherms: Linking physiology and ecology in a multi-stressor landscape. J. Exp. Biol. 2021;224(1):jeb236802. doi: 10.1242/jeb.236802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokolova IM. Energy-limited tolerance to stress as a conceptual framework to integrate the effects of multiple stressors. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2013;53(4):597–608. doi: 10.1093/icb/ict028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abele D, Vazquez-Medina JP, Zenteno-Savin T, editors. Oxidative Stress in Aquatic Ecosystems. Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giannetto A, et al. Effects of oxygen availability on oxidative stress biomarkers in the Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Mar. Biotechnol. 2017;19:614–626. doi: 10.1007/s10126-017-9780-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heise K, Puntarulo S, Nikinmaa M, Abele D, Pörtner HO. Oxidative stress during stressful heat exposure and recovery in the North Sea eelpout Zoarces viviparus L. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209(2):353–363. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sokolova IM. Mitochondrial adaptations to variable environments and their role in animals’ stress tolerance. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2018;58(3):519–531. doi: 10.1093/icb/icy017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Ren RM, Yao CL. Oxidative stress responses of Mytilus galloprovincialis to acute cold and heat during air exposure. J. Molluscan. Stud. 2018;84:285–292. doi: 10.1093/mollus/eyy027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilyk KT, Clive WE, DeVries AL. Heat hardening in Antarctic notothenioid fishes. Polar Biol. 2012;35:1447–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00300-012-1189-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowler K. Acclimation, heat shock and hardening. J. Therm. Biol. 2005;30:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2004.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Precht, H. In Temperature and Life (eds Precht, H. et al.) 302–348 (1973).

- 18.Hilker M, et al. Priming and memory of stress responses in organisms lacking a nervous system. Biol. Rev. 2016;91(4):1118–1133. doi: 10.1111/brv.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldwin IT, Schmelz EA. Immunological" memory" in the induced accumulation of nicotine in wild tobacco. Ecology. 1996;77(1):236–246. doi: 10.2307/2265673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruce TJ, Matthes MC, Napier JA, Pickett JA. Stressful, “memories” of plants: Evidence and possible mechanisms. Plant. Sci. 2007;173(6):603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaskiewicz M, Conrath U, Peterhänsel C. Chromatin modification acts as a memory for systemic acquired resistance in the plant stress response. EMBO. Rep. 2011;12(1):50–55. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yakovlev IA, Asante DK, Fossdal CG, Junttila O, Johnsen Ø. Differential gene expression related to an epigenetic memory affecting climatic adaptation in Norway spruce. Plant. Sci. 2011;180(1):132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yun J, Finkel T. Mitohormesis. Cell Metab. 2014;19:757–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hossain MA, et al. Heat or cold priming-induced cross-tolerance to abiotic stresses in plants: Key regulators and possible mechanisms. Protoplasma. 2018;255:399–412. doi: 10.1007/s00709-017-1150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kouda K, Iki M. Beneficial effects of mild stress (hormetic effects): Dietary restriction and health. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2010;29:127–132. doi: 10.2114/jpa2.29.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malmendal A, et al. Metabolomic profiling of heat stress: Hardening and recovery of homeostasis in Drosophila. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. 2006;291(1):R205–212. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00867.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarup P., Petersen S.M.M., Nielsen N.C., Loeschcke V., Malmendal A. Mild heat treatments induce long-term changes in metabolites associated with energy metabolism in Drosophila melanogaster. Biogerontology. 2016;17(5):873–882. doi: 10.1007/s10522-016-9657-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conrath U, et al. Priming: Getting ready for battle. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 2006;19(10):1062–1071. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farahani S, Bandani AR, Alizadeh H, Goldansaz SH, Whyard S. Differential expression of heat shock proteins and antioxidant enzymes in response to temperature, starvation, and parasitism in the Carob moth larvae, Ectomyeloi sceratoniae (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0228104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horowitz M. From molecular and cellular to integrative heat defense during exposure to chronic heat. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 2002;131:475–483. doi: 10.1016/S1095-6433(01)00500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horowitz M. Epigenetics and cytoprotection with heat acclimation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016;120:702–710. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00552.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang L-H, Chen B, Kang L. Impact of mild temperature hardening on thermotolerance, fecundity, and Hsp gene expression in Liriomyza huidobrensis. J. Insect Physiol. 2007;53:1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willot Q, Gueydan C, Aron S. Proteome stability, heat hardening and heat-shock protein expression profiles in Cataglyphis desert ants. J. Exp. Biol. 2017;220:1721–1728. doi: 10.1242/jeb.154161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moyen NE, Crane RL, Somero GN, Denny MW. A singleheat-stress bout induces rapid and prolonged heat acclimation in the California mussel, Mytilus californianus. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2020;287(1940):20202561. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anestis A, Lazou A, Portner HO, Michaelidis B. Behavioral and metabolic, and molecular stress responses of marine bivalve Mytilus galloprovincialis during long-term acclimation at increasing ambient temperature. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007;293:R911–R921. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00124.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feidantsis K, et al. Correlation between intermediary metabolism, Hsp gene expression, and oxidative stress-related proteins in long-term thermal-stressed Mytilus galloprovincialis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2020;319:R264–R281. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00066.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falfushynska HI, Sokolov E, Piontkivska H, Sokolova IM. The role of reversible protein phosphorylation in regulation of the mitochondrial electron transport system during hypoxia and reoxygenation stress in marine bivalves. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020;7:467. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pörtner H.O., Lucassen M., Storch D. Metabolic biochemistry: its role in thermal tolerance and in the capacities of physiological and ecological function. Fish physiology. 2005;22:79–154. doi: 10.1016/S1546-5098(04)22003-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zittier ZM, Bock C, Lannig G, Pörtner HO. Impact of ocean acidification on thermal tolerance and acid–base regulation of Mytilus edulis (L.) from the North Sea. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2015;473:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2015.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunphy BJ, Ruggiero K, Zamora LN, Ragg NLC. Metabolomic analysis of heat-hardening in adult green-lipped mussel (Perna canaliculus): A key role for succinic acid and the GABAergic synapse pathway. J. Therm. Biol. 2018;74:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase—An energy sensor that regulates all aspects of cell function. Genes Dev. 2011;25(18):1895–1908. doi: 10.1101/gad.17420111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buckley BA, Owen ME, Hofmann GE. Adjusting the thermostat: The threshold induction temperature for the heat shock response in intertidal mussels (genus Mytilus) changes as a function of thermal history. J. Exp. Biol. 2001;204:3571–3579. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.20.3571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hofmann GE, Somero GN. Interspecific variation in thermal denaturation of proteins in the congeneric mussels Mytilus trossulus and M. galloprovincialis: Evidence from the heat-shock response and protein ubiquitination. Mar. Biol. 1996;126:65–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00571378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morimoto RI. Cells in stress: Transcriptional activation of heat shock genes. Science. 1993;259:1409–1410. doi: 10.1126/science.8451637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abele D, Brey T, Philipp E. Bivalve models of aging and the determination of molluscan lifespans. Exp, Gerontol. 2009;44(5):307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anestis A, et al. Response of Mytilus galloprovincialis (L.) to increasing seawater temperature and to marteliosis: Metabolic and physiological parameters. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 2010;156:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solaini G, Baracca A, Lenaz G, Sgarbi G. Hypoxia and mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797(1–6):1171–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quinlan CL, Orr AL, Perevoshchikova IV, Treberg JR, Ackrell BA, Brand MD. Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(32):27255–27264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zorov D, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol. Rev. 2014;94(3):909–950. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hermes-Lima M, et al. Preparation for oxidative stress under hypoxia and metabolic depression: Revisiting the proposal two decades later. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;89:1122–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.07.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holwerda DA, de Zwaan A. On the role of fumarate reductase in anaerobic carbohydrate catabolism of Mytilus edulis L. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 1980;67:447–453. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(80)90332-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gracey AY, Connor K. Transcriptional and metabolomic characterization of spontaneous metabolic cycles in Mytilus californianus under subtidal conditions. Mar. Genom. 2016;30:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Michaelidis B, Haas D, Grieshaber MK. Extracellular and intracellular acid-base status with regard to the energy metabolism in the oyster Crassostrea gigas during exposure to air. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2005;78(3):373–383. doi: 10.1086/430223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michaelidis B, Ouzounis C, Paleras A, Pörtner HO. Effects of long-term moderate hypercapnia on acid-base balance and growth rate in marine mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005;293:109–118. doi: 10.3354/meps293109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pörtner HO. Contributions of anaerobic metabolism to pH regulation in animal tissues: Theory. J. Exp. Biol. 1987;131:69–87. doi: 10.1242/jeb.131.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pörtner HO. Climate change and temperature-dependent biogeography: Oxygen limitation of thermal tolerance in animals. Sci. Nat. 2001;88:137–146. doi: 10.1007/s001140100216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Götze S, et al. Single and combined effects of the “Deadly trio” hypoxia, hypercapnia and warming on the cellular metabolism of the great scallop Pecten maximus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 2020;243–244:110438. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2020.110438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tomanek L, Zuzow MJ. The proteomic response of the mussel congeners Mytilus galloprovincialis and M. trossulus to acute heat stress: Implications for thermal tolerance limits and metabolic costs of thermal stress. J. Exp. Biol. 2010;213(20):3559–3574. doi: 10.1242/jeb.041228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramnanan CJ, Storey KB. Suppression of Na+/K+-ATPase activity during estivation in the land snail Otala lactea. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209:677–688. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lama JL, Bell RA, Storey KB. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase regulation in the hepatopancreas of the anoxia-tolerant marine mollusc, Littorina littorea. PeerJ. 2013;1:e21. doi: 10.7717/peerj.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woo S, et al. Expressions of oxidative stress-related genes and antioxidant enzyme activities in Mytilus galloprovincialis (Bivalvia, Mollusca) exposed to hypoxia. Zool. Stud. 2013;52:15. doi: 10.1186/1810-522X-52-15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Somero G.N. The cellular stress response and temperature: Function, regulation, and evolution. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological and Integrative Physiology. 2020;333(6):379–397. doi: 10.1002/jez.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bonneton F, Theodore L, Silar P, Maroni G, Wegnez M. Response of Drosophila metallothionein promoters to metallic, heat shock and oxidative stress. FEBS. Lett. 1996;380:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Niederwanger Μ, et al. Challenging the Metallothionein (MT) gene of Biomphalaria glabrata: Unexpected response patterns due to cadmium exposure and temperature stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1747. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santoro N, Johansson N, Thiele DJ. Heat shock architecture is an important determinant in the temperature and transactivation domain requirements for heat shock transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:6340–6352. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.11.6340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bauman JW, Liu J, Klaassen CD. Production of metallothionein and heat-shock proteins in response to metals. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1993;21:15–22. doi: 10.1006/faat.1993.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aleng NA, Sung YY, MacRae TH, Wahid MEA. Non-lethal heat shock of the Asian green mussel, Perna viridis, promotes Hsp70 synthesis, induces thermotolerance and protects against Vibrio Infection. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0135603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huppert HW, Laudien H. Influence of pretreatment with constant and changing temperatures on heat and freezing resistance in gill-epithelium of the mussel Mytilus edulis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1980;3:113–120. doi: 10.3354/meps003113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hawkins TD, Warner ME. Warm preconditioning protects against acute heat-induced respiratory dysfunction and delays bleaching in a symbiotic sea anemone. J. Exp. Biol. 2017;220(6):969–983. doi: 10.1242/jeb.150391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wesener F, Tietjen B. Primed to be strong, primed to be fast: Modeling benefits of microbial stress responses. FEMS. Microbiol. Ecol. 2019;95:fiz114. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiz114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pereira RRC, Scanes E, Gibbs M, Byrne M, Ross PM. Can prior exposure to stress enhance resilience to ocean warming in two oyster species? PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0228527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krebs RA, Loeschcke V. Costs and benefits of activation of the heat-shock response in Drosophila melanogaster. Funct. Ecol. 1994;8:730–737. doi: 10.2307/2390232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Berry DB, Gasch AP. Stress-activated genomic expression changes serve a preparative role for impending stress in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:4580–4587. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-07-0680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kültz D, Somero GN. Introduction to the special issue: Comparative biology of cellular stress responses in animals. J. Exp. Zool. 2020;333:345–349. doi: 10.1002/jez.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Connor K, Gracey AY. Cycles of heat and aerial-exposure induce changes in the transcriptome related to cell regulation and metabolism in Mytilus californianus. Mar. Biol. 2020;167(9):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00227-020-03750-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hutchison VH. Critical thermal maxima in salamanders. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 1961;34:92–125. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Darmaraki S, et al. Future evolution of marine heatwaves in the Mediterranean Sea. Clim. Dyn. 2019;53(3):1371–1392. doi: 10.1007/s00382-019-04661-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim GU, Seo KH, Chen D. Climate change over the Mediterranean and current destruction of marine ecosystem. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55303-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Paladino FV, Spotila JR, Schubauer JP, Kowalski KT. The critical thermal maximum: A technique used to elucidate physiological stress and adaption in fishes. Rev. Can. Biol. 1980;39:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Salach JI. Preparation of monoamine oxidase from beef liver mitochondria. Methods Enzymol. 1978;53:495–501. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(78)53052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Paoletti F, Mocali A. Determination of Superoxide dismutase activity by purely chemical system based on NAD(P)H oxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:209–220. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86110-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cohen G, Dembiec D, Marcus J. Measurement of CAT activity in tissue extracts. Anal. Biochem. 1970;34(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carlberg I, Mannervik B. Glutathione reductase. Methods Enzymol. 1985;113:484–490. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(85)13062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Haider F, Sokolov EP, Sokolova IM. Effects of mechanical disturbance and salinity stress on bioenergetics and burrowing behavior of the soft-shell clam Mya arenaria. J. Exp. Biol. 2018;221:jeb172643. doi: 10.1242/jeb.172643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moreira R, Pereiro P, Costa MM, Figueras A, Novoa B. Evaluation of reference genes of Mytilus galloprovincialis and Ruditapes philippinarum infected with three bacteria strains for gene expression analysis. Aquat. Living Resour. 2014;27:147–152. doi: 10.1051/alr/2014015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.