Abstract

Non-target analysis (NTA) employing high-resolution mass spectrometry is a commonly applied approach for the detection of novel chemicals of emerging concern in complex environmental samples. NTA typically results in large and information-rich datasets that require computer aided (ideally automated) strategies for their processing and interpretation. Such strategies do however raise the challenge of reproducibility between and within different processing workflows. An effective strategy to mitigate such problems is the implementation of inter-laboratory studies (ILS) with the aim to evaluate different workflows and agree on harmonized/standardized quality control procedures. Here we present the data generated during such an ILS. This study was organized through the Norman Network and included 21 participants from 11 countries. A set of samples based on the passive sampling of drinking water pre and post treatment was shipped to all the participating laboratories for analysis, using one pre-defined method and one locally (i.e. in-house) developed method. The data generated represents a valuable resource (i.e. benchmark) for future developments of algorithms and workflows for NTA experiments.

Subject terms: Environmental monitoring, Mass spectrometry

| Measurement(s) | chemical • drinking water |

| Technology Type(s) | high resolution mass spectrometry • non-target analysis • Interlaboratory |

| Factor Type(s) | method |

| Sample Characteristic - Environment | laboratory environment |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.15028665

Background & Summary

Non-target analysis (NTA) using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) is the most comprehensive approach for the screening and discovery of organic compounds/chemicals of emerging concern (CECs) in complex environmental samples1–7. This strategy is a bottom up approach with minimum a priori assumptions and/or knowledge regarding the samples and the CECs5,8–10. The recent surge in the number of newly identified CECs in different environmental compartments is a testimonial to the power of this technology11–13.

The main drawback of NTA is its complexity. Long and laborious processes increase the likelihood of false positive and false negative results, and the resulting data is difficult to interpret and can suffer from poor reproducibility1,7,8,14–18. Additionally, the wide variety of chemicals with different physico-chemical properties and variable concentration ranges make NTA an extremely challenging task4,19.

Several sophisticated algorithms and workflows have been developed in the past decade to tackle the complexity of NTA data3,5,20–23. Each of these approaches attempted to address one or more steps in the process, from noise removal, over peak picking to identification and finally communication of the confidence level of the identified CECs. While these algorithms have shown increasing success, there still remain some challenges with NTA and the underlying assumptions. Accordingly, recent studies have highlighted that further improvements are needed to be able to generate reproducible results8,15,24,25.

International collaborative efforts, such as raw data sharing (e.g. FAIR Principles26,27), novel CEC sharing (e.g. NormaNews28), community based spectral libraries (e.g. MassBank EU29 and MoNA), and former inter-laboratory studies (ILSs) have shown great potential in highlighting these shortfalls. Such work is crucial to steer future research and ensure success9,12,13,21,28. An example of such effort was the NTA collaborative trial organized by Norman Network9,10, which promoted a clear reporting strategy of the confidence levels in the identified CECs in complex samples within the environmental chemistry field9,10.

In this study, we present the data collected during an international collaborative ILS organized through the Norman Network. This study aimed at assessing the uncertainty in the identified compounds caused by different NTA workflows and spectral databases. We used a passive sampling (PS) strategy to sample river water at a drinking water intake, and post treatment for the production of drinking water. This will enable us to sample substances (i) present in river water at the drinking water intake, (ii) present in drinking water, as well identify those (iii) removed during treatment and (iv) generated during drinking water treatment.

PS enables to pre-concentrate chemicals from a complex matrix while leaving behind a significant proportion of unwanted matrix affecting the performance of the analysis, therefore allowing to sample chemicals often found at trace-levels in water and in the environment30,31. PS devices accumulate chemicals through diffusion over time when deployed in water (Table 1). When uptake kinetics are known and understood, it is possible to relate the amount of a chemical accumulated in a sampler to its time-averaged concentration in water for the period of deployment through a sampling rate, an equivalent volume of water extracted by the sampler per unit of time. This allows the collection of a more representative sample than when using spot sampling.

Table 1.

Overview of samples provided to participants.

| Vial number | Matrix type | Sampler Exposure time | Estimated sampled water volume | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vial 1 | PS extract – River water | 2 days | 4.8 L | S2 2 |

| Vial 2 | PS extract – River water | 4 days | 8.7 L | S2 4 |

| Vial 3 | PS extract – drinking water | 2 days | 4 L | S1 2 |

| Vial 4 | PS extract – drinking water | 4 days | 7.4 L | S1 4 |

| Vial 5 | Procedural blank (field blank) | — | B | |

| Vial 6 | RTI mixture standard | — | RTI |

All participants in this ILS were given the same “ready for injection” samples consisting of the two surface water and two drinking water PS extracts. They were requested to analyze these PS extracts using one pre-defined method for liquid chromatography (LC) and mass spectrometry (MS), Table 2. Participants were also required to analyze the samples via their “in-house” methods. The participants were allowed the freedom to use any data processing strategy for the identification of CECs in those samples (details are provided in section Experimental Design).

Table 2.

Gradient programme for the pre-defined method using a 150 mm × 2.1 mm column with 1.8 μm particles, with a flowrate of 0.4 ml/min.

| Time | % A | % B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 87 | 13 |

| 0.5 | 87 | 13 |

| 10.0 | 50 | 50 |

| 10.75 | 5 | 95 |

| 12.25 | 5 | 95 |

| 12.5 | 87 | 13 |

| 15.0 | 87 | 13 |

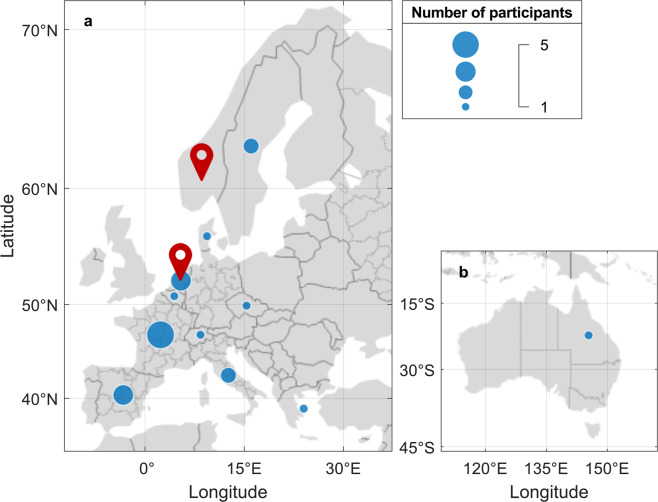

This dataset includes the raw data from 21 different laboratories (Fig. 1), using different reversed-phase LC (RPLC) columns and instrumentations (Tables 3 and 4, respectively), chromatographic gradients, and MS acquisitions. This dataset provides the means to assess the impact of method transfer, chromatographic conditions, and data processing workflows on the results of NTA approaches. Additionally, this dataset may, potentially, be used as a benchmark for future development of algorithms for NTA workflows.

Fig. 1.

Map depicting the distribution of participating laboratories in the international ILS. The size of the bubble represents the number of participating labs in each country and the two organizing institutes of the ILS are represented by the red location markers. All laboratories providing data are located in Europe (a) except for one which is located in Australia (b).

Table 3.

Columns used for the pre-defined method and the in-house method, as indicated by the participant; the number of participants using the same column is indicated in brackets.

| Manufacturer | Model pre-defined method | Model “In-house” method |

|---|---|---|

| Waters | Acquity (UPLC) BEH C18 (4) | Acquity (UPLC) BEH C18 (4) |

| Acquity UPLC HSS C18 (2) | ||

| Acquity HSS-T3 C18 | Acquity HSS-T3 C18 | |

| Xselect HSS C18 | Xselect HSS C18 | |

| Xbridge C18 | Xbridge C18 | |

| Cortecs C18 | Cortecs C18 | |

| HSS T3 C18 | HSS T3 C18 | |

| Atlantis C18 | ||

| Agilent | Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 | Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 |

| Zorbax SB AQ | Zorbax SB AQ | |

| Zorbax Eclipse XDB C18 | Zorbax Eclipse XDB C18 | |

| ThermoScientific | Hypersil BDS C18 | |

| Acclaim RSLC 120 C18 (2) | ||

| Acclaim PepMap RSLC 100 C18 | ||

| Phenomenex | Kinetex XB-C18 | |

| Luna C18 (3) | Luna C18 | |

| Kinetex Biphenyl | ||

| Kinetex EVO C18 | ||

| Restek | Raptor C18 | |

| ACE | UltraCore 2.5 SuperPhenylHexyl |

Table 4.

Manufacturers and models of MS instruments used by the participants.

| Manufacturer | Model |

|---|---|

| Thermo Fisher Scientific | QExactive HF (2) |

| QExactive Focus (2) | |

| QExactive (2) | |

| Orbitrap Lumos Fusion | |

| Orbitrap Velos | |

| Waters | Xevo G2-S QTOF (3) |

| Xevo G2 QTOF | |

| Xevo G2-XS QTOF | |

| Vion IMS Q-TOF | |

| Bruker | Maxis Impact |

| Maxis Plus | |

| Compact | |

| Sciex | TripleTOF 5600+ |

| TripleTOF 6600 | |

| X500R | |

| Agilent | QTOF 6550 |

The number of participants using the same model of MS instruments is indicated in brackets.

Methods

Experimental design

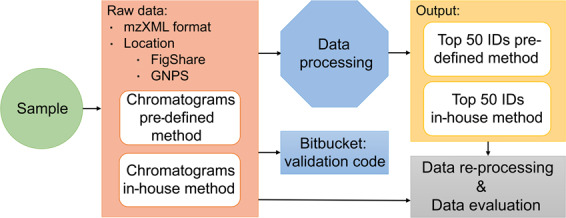

The participants were given a set of samples and were asked to perform a complete NTA/extended suspect screening workflow (i.e. RPLC coupled with HRMS) using two different experimental approaches. A harmonized approach, hereafter referred to as pre-defined method (details are provided in the section “pre-defined method”) and an individually developed in-house method. Finally, the participants were requested to provide: the raw data (i.e. vendor format), the converted files (mzMXL format), the raw feature list associated with each sample, the top 50 identified features including the level of confidence in the identifications, based on the Schymanski scale9.

The experimental design (Fig. 2) allows the systematic assessment of the impact of the method transfer, chromatography approach, and data acquisition on the explored chemical space. Furthermore, it enables the evaluation of the impact of different data processing strategies on the identified features and the level of confidence associated to the identifications according to the tiered levels proposed by Schymanski et al.9,10.

Fig. 2.

The experimental design of the ILS.

Sample set

A sample set including six vials was shipped to all 21 participants of this ILS. The vials consisted of four extracts from passive samplers (PS), one procedural blank, and a mixture of internal standards (IS) for the retention time modeling developed by the University of Athens (Table 1)32.

To generate the samples, integrative sampling at both the input and the output of a drinking water treatment plant (i.e. the source river water and drinking water, respectively) was carried out in June 2019 using Horizon Atlantic® HLB-L disks (47 mm diameter) with exposure times of 2 and 4 days. A detailed description of the sampling and sample preparation is given in supporting information (SI).

HLB disks were chosen as the receiving phase as the HLB sorbent has been shown to be suitable for the sampling of a variety of substances with different physicochemical properties, including compounds with low logD/Kow or ionized at river/drinking water pH33,34. However, limitations exist, particularly in the very low logD range.

In order to increase the sampling rate of the chemicals into the PS, the samplers were placed in a “dynamic” PS device (DPS), consisting of an electrically driven large volume water pumping device coupled to a PS exposure cell35. A total of 26 discs were exposed to treated drinking water and the same number to source water.

The exposed HLB disks, once in the lab, were kept in the freezer at −20 °C until extraction. The frozen disks were then freeze-dried for 48 hours to remove any water residues. The dried disks were spiked with six isotope-labeled ISs (i.e. Caffeine-13C3, Nicotine-D4, Cotinine-D3, Simazine-D10, Carbamazepine-D10, and Diuron-D6) prior to extraction. The spiking level was set at 50 ng/mL of each IS in the final extract, assuming a 100% recovery.

For the extraction, we used a previously tested wide-scope approach, which consisted of three consecutive extractions of the PS with 200 mL of acetone for 24 hr. The final extracts, then, were solvent exchange to methanol, following the US EPA method 357036. The extracts of 13 different PS were pooled together to obtain homogeneous samples/extracts that were shipped to the participants. We also included a procedural blank, which consisted of the pooled extracts of seven PS brought to the field without being exposed to water.

In order to estimate the approximate volume of water sampled by the HLB disk PS, 0.5 mm thick silicone sheets made of AlteSil™ (Altec, UK) with the exposed surface area of 200 cm2 were co-deployed in the DPS next to the HLB disks. Prior to exposure, the silicone sheets were spiked with 14 performance reference compounds (PRCs)35. The loss of PRCs from silicone during exposure was applied to calculate the mass transfer coefficient (MTC) of PRCs through the water boundary layer (WBL). The estimated volumes of water extracted by HLB disks are based on the assumption of the same WBL-controlled MTC in silicone and HLB disks, by the approach shown by Vrana et al.35 and were 190 and 346 L for the river exposures for 2 and 4 days, 160 and 295 L for the drinking water exposures.

Considering the 40 times dilution used to prepare individual vials for distribution to participating laboratories, vials 1 to 4 contained equivalent volumes of water sampled by the HLB discs of 4.8, 8.7, 4.0 ad 7.4 L, respectively (Table 1). This can be applied to substances accumulated linearly over the exposure time by the HLB discs under boundary-layer controlled uptake. This is not necessarily applicable to all substances and samples.

Pre-defined method

The pre-defined method consisted of two components, namely: 1) LC separation and 2) mass spectrometric data acquisition. The participants were given detailed instructions on how to set up the exact conditions on their instruments. Additionally, the participants were given access to a set of tools (e.g. method transfer and column chemistry assessment - https://find.waters.com/ColumnCoach/existingcolumn/column) to find the closest conditions to the instructions in the pre-defined method37.

Separation: the mobile phase consisted of 5 mM aqueous ammonium formate adjusted to pH 3 (A) and acetonitrile (ACN) containing 0.1% formic acid (B) used in a 15 min gradient elution (Table 2). The flow was given at 0.4 ml/min for a 150 mm × 2.1 mm × 1.8 μm C18 (Acquity UPLC BEH C18). The injection volume for this method was set to 5 µL. The pre-defined method was a wide scope generic method for analysis of pharmaceuticals and pesticides in environmental samples16,38.

Data acquisition: the participants were requested to run their samples in a data-independent acquisition mode. The mass range was set between 50 and 900 Da. For the quadrupole-time-of-flight (QTOF) instruments the sampling rate was limited to 2 Hz while for Orbitrap instruments the participants were advised to run their samples with maximum of 60,000 resolution. For the SWATH experiments, the number of windows was limited to 10. The method required acquisition in positive-polarity mode using an electrospray-ionization source. For the pseudo MS2 spectra, the participants were asked to perform their experiments either using a collision energy of 10–45 eV as a ramp or an average collision energy of 30–40 eV.

It should be noted that the observed diversity in the pre-defined method may or may not translate into the same level of diversity in the explored chemical space. In fact this can only be assessed by systematic re-processing of the data using open source/access workflows, which will be the subject of future studies by the consortium.

Variations in the pre-defined method

Twenty out of the 21 participants, depending on the availability of instrumentations in their labs, implemented some changes in the pre-defined method, employing the provided tools by the organizers.

Four out of 21 participants opted for reconstitution of the extracts into ACN/water 50/50, ACN/water 14/86, methanol/water 10/90 or methanol, prior to the separation. One participant mixed the sample with mobile phase A (see above) at a 1:1 volume ratio.

As for the injection volumes, 16 participants followed the instructions in the pre-defined method (i.e. 5 µL) while three participants opted for 10 µL injection volume. One of the participants performed a large volume injection of 200 µL.

All participants used C18 columns for both the pre-defined and in-house methods. 14 out of 21 participants used the 0.4 mL/min flow rate suggested by the pre-defined method while six participants used different flow rates between 0.21 and 0.3 mL/min and one of 1 mL/min. Additionally, it should be noted that not all the participants employed the same column for both pre-defined and in-house methods (Table 3).

In terms of mass spectrometers, 8 Thermo Fisher Scientific, 6 Waters, 3 Bruker, 3 Sciex and 1 Agilent instruments were used for the data acquisition. All eight Thermo Fisher Scientific instruments were Orbitraps, while all other instruments relied on the time-of-flight (TOF) principle (Table 4). All the participants were asked to perform the analysis via data independent acquision (DIA). This acquisition mode of accurate-mass full-scan spectra under different collision induced dissociation conditions within a single injection is known under different names depending on the manufacturer: MSE in the case of Waters, broadband collision-induced dissociation (bbCID) in the case of Bruker, or all-ions MS/MS in the case of Agilent. Likewise for Q-Orbitrap instruments from Thermo, this type of acquisition is also possible, and known as All Ion Fragmentation (AIF) or variable Data-Independent Analysis (vDIA). An alternative DIA was Sequential Window Acquisition of All Theoretical Mass Spectra (SWATH-MS), which maily performed via AB Sciex instruments.

For the acquisition mode and collision energies, all participants followed the instructions provided. As for the mass range, 17 used the range defined in the pre-defined method whereas four participants used 75–950, 100–900, or 77–1000 Da.

In-house method

The participants were also asked to analyze the extracts using an in-house method. Six out of 21 participants decided to reconstitute the sample in new solvent, five of which in methanol/water (4.8%, 10%, 20%, 50% and 100% methanol) and one in ACN/water 1/99. Injection volumes, in this case, ranged from 2 μL to 1000 μL, with 16 institutes using 5 μL, similar to the pre-defined method, and two using 10 μL.

Commonly applied flow rates ranged from 0.2 mL/min to 0.5 ml/min with the median at 0.375 mL/min while there were two cases with 1 mL/min and 0.0002 mL/min (nano LC). Two participants used flow gradients (0.2–0.48 ml/min and 0.3–0.4 ml/min).

As for column chemistries, we observed a greater diversity in the used columns when compared to the pre-defined method. More specialized columns were used for the in-house method. However, some participants used the same column for both methods (Table 3). The used mobile phases, varied mostly in the concentration of additives: water with ammonium acetate or formate (up to 10 mM) and formic acid (up to 0.1%) for mobile phase A and methanol or ACN, pure or with the same additives, for mobile phase B. All participants used gradients for elution, mostly running between 20 and 30 minutes.

The starting masses for the scan range ranged from 30 Da to 100 Da with a median of 60 Da, while the end of the scan range was between 800 and 1300 Da with the median at 925 Da. Collision energies were the same as the ones used for the pre-defined method except for slight changes (experimental details are provided in Record 3).

Data conversion

The participants were asked to convert the datasets to mzXML39 format prior to submission using either the vendor provided tools or MSConvert implemented via ProteoWizard40. All the users employed the MSConvert 32− or 64-bit. Additionally, a minimum absolute intensity of 50 counts was applied to all mzXML files as the intensity threshold, in order to reduce the size of the converted data.

Data Records

This ILS resulted in three different data records – i.e. mzXML files related to the pre-defined method, mzXML files related to the in-house method, and the experimental conditions in XLSX format.

Record 1

includes the mzXML files for both the samples related to the river water and drinking water with exposure times of 2 and 4 days analyzed via the pre-defined method. This record includes 157 mzXML files41,42.

Record 2

includes the mzXML files for both the samples related to the river water and drinking water with exposure times of 2 and 4 days analyzed via the own method. This record includes 134 mzXML files42,43.

Record 3

consists of an excel file that includes the details of participants and the experimental conditions associated with each mzXML file, including the software packages used for the data acquisition and pre-processing44.

Record GNPS

additionally, all the mzXML files from records 1 and 2 are also available for download or analysis via GNPS42.

Technical Validation

We used the detection of IS, their mass accuracy, retention factor (i.e. run-time normalized retention time), and their intensity to assess the quality of the generated data by the participants. The extracted ion chromatograms (XIC) of the IS were generated using a mass window of ±0.01 Da. The peak of each IS was identified as the maximum signal in the selected XIC. Cases where we were not able to identify the IS signal as the most prominent signal, were considered as not detected. The measured mass (i.e. the median mass of three scans around apex), retention time, and intensity of apex were recorded for quality assurance of the data.

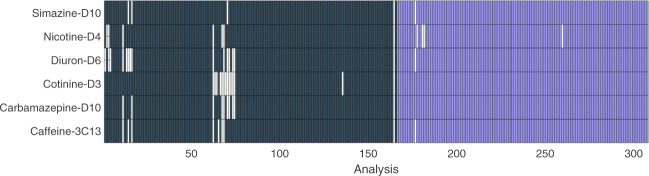

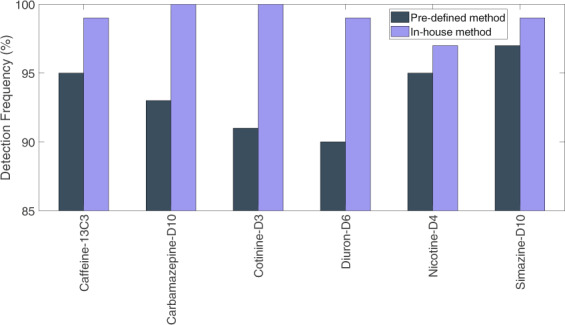

For 98% of datasets, the participants were able to detect all six IS, independently from the method used (i.e. pre-defined versus in-house). For two cases analyzed via the pre-defined method only three out of six ISs were detected while this was the case only for one chromatogram via own method, respectively. Higher detection frequencies were obtained for the in-house method than for the pre-defined method for all IS (Fig. 3). Diuron-D6 had the lowest detection frequency of 92% for pre-defined method whereas nicotine-D4 was the IS with the lowest detection frequency of 96% via the in-house method (Fig. 4). Diuron-D6 was the latest eluting IS with pre-defined method whereas nicotine-D4 was the IS with the smallest retention time for both methods (Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 3.

The detection overview for all six ISs for both pre-defined (dark gray) and in-house (light purple) methods. The white boxes are non-detected ISs.

Fig. 4.

The detection frequency of each IS in pre-defined and in-house method.

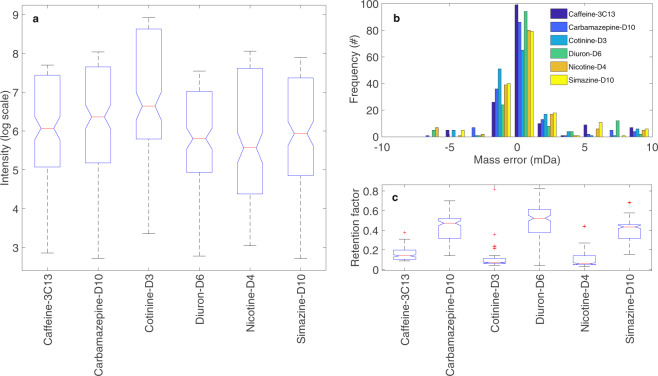

Fig. 5.

Variance observed in (a) the intensity in log scale, (b) the mass error (mDa), and (c) the retention factor of each IS recorded via pre-defined method. The retention factor was obtained by dividing the retention time for each detected IS by the total analysis time.

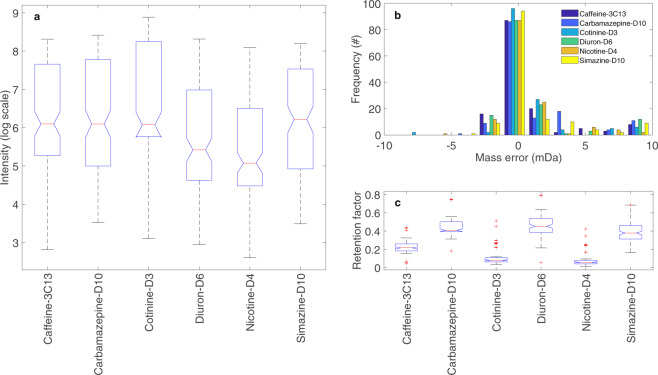

Fig. 6.

Variance observed in (a) the intensity in log scale, (b) the mass error (mDa), and (c) the retention factor of each IS recorded via in-house method. The retention factor was obtained by dividing the retention time for each detected IS by the total analysis time.

When looking at the mass error of IS, for both methods, a median of ±12 ppm was observed (Figs. 5 and 6). Overall, the mass errors were distributed between −7 mDa and +10 mDa, for both methods. We did not observe a statistically significant correlation between the retention time, m/z value and the measured mass error.

As for the intensities of the IS a median intensity of 106 was measured across the datasets and the methods. The variance in the intensities of around five orders of magnitude appeared to be independent from the method used for the analysis.

Usage Notes

Often, when developing new tools for NTA, they are restricted to a limited number of datasets usually generated in one laboratory. These datasets rarely represent the actual diversity in potential future datasets that should be processed using these tools. In this data descriptor, we present a dataset which covers a wide range of instruments and instrumental/analysis conditions. Additionally, the dataset in this study provides three different levels of chemical complexity (i.e. the number of potential chemical constituents) in blank, drinking water, and river water, respectively. Such a dataset can be used for the assessment of the impact of method transfer on the explored chemical space of the samples as well as the quality of the generated spectra. The records made available with this data descriptor constitute a valuable resource for the future development of NTA algorithms and workflows, for example by providing a collection of successfully identified compounds and retention time indices obtained over a wide range of instruments and analytical conditions. Altogether, these can be used by individual laboratories for evaluation of their own practices.

When using this data, the records 1 and 2 have the following name structure: InstituteID_(nr)_pd.mzXML for the pre-defined method and InstituteID_(nr)_own.mzXML for the in-house method. These files can be opened with almost any open source software for MS data.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NORMAN network. MH acknowledge funding from the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (MST-667-00207) and The Aarhus University Research Foundation (AUFF-T-2017-FLS-7-4). The authors are also thankful to Biotage for providing the passive samplers and Helena Švecová for contribution during the sampling.

Author contributions

The core group of authors included Bastian Schulze, Denice van Herwerden, Ian Allan, Lubertus Bijlsma, Nestor Etxebarria, Martin Hansen and Sylvain Merel, the project was conceptualized by Ian Allen, Pavla Fialová, Roman Grabic, Juliane Hollender, Christelle Margoum, Cécile Miège, Malcolm Reid, Saer Samanipour and Branislav Vrana. The report was written by Bastian Schulze, Denice van Herwerden and Saer Samanipour and reviewed by all involved authors. Data was contributed by Bastian Schulze, Lubertus Bijlsma, Bernard Bajema, Nestor Etxebarria, Martin Hansen, Sylvain Merel, Reza Aalizadeh, Florian Dubocq, Gianluca Coppola, Aurélie Fildier, Emil Frøkjær, Roman Grabic, Pablo Gago-Ferrero, Thorsten Gravert, Juliane Hollender, Nina Huynh, Tim Jonkers, Sarit Kaserzon, Marja Lamoree, Julien Le Roux, Teresa Mairinger, Christelle Margoum, Giuseppe Mascolo, Emmanuelle Mebold, Frank Menger, Cécile Miège, Jeroen Meijer, Régis Moilleron, Sapia Murgolo, Griet Jacobs, Massimo Peruzzo, Martijn Pijnappels, Claudio Roscioli, Coralie Soulier, Sara Valsecchi, Nikolaos Thomaidis, Emmanuelle Vulliet and Robert Young.

Code availability

The script for the extraction of the IS signal and the plots in this data descriptor is available in this repository: https://bitbucket.org/Denice_van_Herwerden/ils-validation/src/main/.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-021-01002-w.

References

- 1.Schulze, B. et al. An assessment of Quality Assurance/Quality Control Efforts in High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Non-Target Workflows for Analysis of Environmental Samples. Trends Anal. Chem. 133, 116063 (2020).

- 2.Bletsou AA, Jeon J, Hollender J, Archontaki E, Thomaidis NS. Targeted and non-targeted liquid chromatography-mass spectrometric workflows for identification of transformation products of emerging pollutants in the aquatic environment. Trends Anal. Chem. 2015;66:32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2014.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martínez-Bueno MJ, Gómez Ramos MJ, Bauer A, Fernández-Alba AR. An overview of non-targeted screening strategies based on high resolution accurate mass spectrometry for the identification of migrants coming from plastic food packaging materials. Trends Anal. Chem. 2019;110:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2018.10.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milman BL, Zhurkovich IK. The chemical space for non-target analysis. Trends Anal. Chem. 2017;97:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2017.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oberacher H, Arnhard K. Current status of non-targeted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry in forensic toxicology. Trends Anal. Chem. 2016;84, Part B:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2015.12.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albergamo V, et al. Nontarget Screening Reveals Time Trends of Polar Micropollutants in a Riverbank Filtration System. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:7584–7594. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b01750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samanipour S, Martin JW, Lamoree MH, Reid MJ, Thomas KV. Letter to the Editor: Optimism for Nontarget Analysis in Environmental Chemistry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:5529–5530. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b01476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hohrenk LL, et al. Comparison of Software Tools for Liquid Chromatography–High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Data Processing in Nontarget Screening of Environmental Samples. Anal. Chem. 2020;92:1898–1907. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schymanski EL, et al. Identifying Small Molecules via High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Communicating Confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:2097–2098. doi: 10.1021/es5002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schymanski EL, et al. Non-target screening with high-resolution mass spectrometry: critical review using a collaborative trial on water analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015;407:6237–55. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-8681-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian Z, et al. A ubiquitous tire rubber–derived chemical induces acute mortality in coho salmon. Science. 2021;37:185–189. doi: 10.1126/science.abd6951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulrich EM, et al. EPA’s non-targeted analysis collaborative trial (ENTACT): genesis, design, and initial findings. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019;411:853–866. doi: 10.1007/s00216-018-1435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rostkowski P, et al. The strength in numbers: comprehensive characterization of house dust using complementary mass spectrometric techniques. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019;411:1957–1977. doi: 10.1007/s00216-019-01615-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollender J, Schymanski EL, Singer HP, Ferguson PL. Nontarget Screening with High Resolution Mass Spectrometry in the Environment: Ready to Go? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:11505–11512. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hites RA, Jobst KJ. Response to “Letter to the Editor: Optimism for Nontarget Analysis in Environmental Chemistry”. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:5531–5533. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b02473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samanipour, S., Reid, M. J. & Thomas, K. V. Statistical Variable Selection: An Alternative Prioritization Strategy during the Nontarget Analysis of LC-HR-MS Data. Anal. Chem. 89, 10, 5585–5591 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Samanipour S, Reid MJ, Bæk K, Thomas KV. Combining a Deconvolution and a Universal Library Search Algorithm for the Nontarget Analysis of Data-Independent Acquisition Mode Liquid Chromatography−High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Results. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:4694–4701. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b00259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samanipour S, et al. Machine learning combined with non-targeted LC-HRMS analysis for a risk warning system of chemical hazards in drinking water: A proof of concept. Talanta. 2019;195:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escher BI, Stapleton HM, Schymanski EL. Tracking complex mixtures of chemicals in our changing environment. Science. 2020;367:388–392. doi: 10.1126/science.aay6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gosetti F, Mazzucco E, Gennaro MC, Marengo E. Contaminants in water: non-target UHPLC/MS analysis. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2016;14:51–65. doi: 10.1007/s10311-015-0527-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alygizakis NA, et al. NORMAN digital sample freezing platform: A European virtual platform to exchange liquid chromatography high resolution-mass spectrometry data and screen suspects in “digitally frozen” environmental samples. Trends Anal. Chem. 2019;115:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2019.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaženović I, Kind T, Ji J, Fiehn O. Software Tools and Approaches for Compound Identification of LC-MS/MS Data in Metabolomics. Metabolites. 2018;8:31. doi: 10.3390/metabo8020031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow CWK, et al. Development of smart data analytics tools to support wastewater treatment plant operation. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2018;177:140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.chemolab.2018.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brodsky L, Moussaieff A, Shahaf N, Aharoni A, Rogachev I. Evaluation of Peak Picking Quality in LC−MS Metabolomics Data. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:9177–9187. doi: 10.1021/ac101216e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samanipour S, O’Brien JW, Reid MJ, Thomas KV. Self Adjusting Algorithm for the Nontargeted Feature Detection of High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Coupled with Liquid Chromatography Profile Data. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:10800–10807. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkinson MD, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data. 2016;3:160018. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.FAIR Principles. GO FAIRhttps://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/.

- 28.Alygizakis NA, et al. Exploring the Potential of a Global Emerging Contaminant Early Warning Network through the Use of Retrospective Suspect Screening with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:5135–5144. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b00365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.2020. MassBank consortium and its contributors. MassBank/MassBank-data: Release version 2020.06. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 30.Vrana B, et al. Passive sampling techniques for monitoring pollutants in water. Trends Anal. Chem. 2005;24:845–868. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2005.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miège, C. et al. Position paper on passive sampling techniques for the monitoring of contaminants in the aquatic environment – Achievements to date and perspectives. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 8, 20–26 (2015).

- 32.Aalizadeh R, Nika M-C, Thomaidis NS. Development and application of retention time prediction models in the suspect and non-target screening of emerging contaminants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019;363:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samanipour S, et al. Assessing sample extraction efficiencies for the analysis of complex unresolved mixtures of organic pollutants: A comprehensive non-target approach. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2018;1025:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samanipour S, et al. The effect of extraction methodology on the recovery and distribution of naphthenic acids of oilfield produced water. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;652:1416–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vrana B, et al. Mobile dynamic passive sampling of trace organic compounds: Evaluation of sampler performance in the Danube River. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;636:1597–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US EPA, O. EPA Method 3570 (SW-846): Microscale Solvent Extraction (MSE). US EPAhttps://www.epa.gov/esam/epa-method-3570-sw-846-microscale-solvent-extraction-mse (2019).

- 37.Samanipour S. 2021. NORMAN Collaborative Trial on Passive Sampling and Non-target Screening (NTS) Instruction file. University of Amsterdam. [DOI]

- 38.Samanipour, S. et al. Two stage algorithm vs commonly used approaches for the suspect screening of complex environmental samples analyzed via liquid chromatography high resolution time of flight mass spectroscopy: A test study. J. Chromatogr. A1501, 68–78 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Deutsch EW. File Formats Commonly Used in Mass Spectrometry. Proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP. 2012;11:1612–1621. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R112.019695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chambers MC, et al. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:918–920. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samanipour S. 2021. NORMAN Collaborative Trial on Passive Sampling and Non-target Screening (NTS) - Pre-defined method (individual files) figshare. [DOI]

- 42.Samanipour S. 2021. Inter-laboratory dataset from a collaborative trial for future use in the development of non-target analysis. MassIVE. [DOI]

- 43.Samanipour S. 2021. NORMAN Collaborative Trial on Passive Sampling and Non-target Screening (NTS) - Own method (individual files) figshare. [DOI]

- 44.Samanipour S. 2021. NORMAN Collaborative Trial on Passive Sampling and Non-target Screening (NTS) - Metadata. figshare. [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2020. MassBank consortium and its contributors. MassBank/MassBank-data: Release version 2020.06. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Samanipour S. 2021. NORMAN Collaborative Trial on Passive Sampling and Non-target Screening (NTS) Instruction file. University of Amsterdam. [DOI]

- Samanipour S. 2021. NORMAN Collaborative Trial on Passive Sampling and Non-target Screening (NTS) - Pre-defined method (individual files) figshare. [DOI]

- Samanipour S. 2021. Inter-laboratory dataset from a collaborative trial for future use in the development of non-target analysis. MassIVE. [DOI]

- Samanipour S. 2021. NORMAN Collaborative Trial on Passive Sampling and Non-target Screening (NTS) - Own method (individual files) figshare. [DOI]

- Samanipour S. 2021. NORMAN Collaborative Trial on Passive Sampling and Non-target Screening (NTS) - Metadata. figshare. [DOI]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The script for the extraction of the IS signal and the plots in this data descriptor is available in this repository: https://bitbucket.org/Denice_van_Herwerden/ils-validation/src/main/.