Abstract

Introduction

Healthcare workers (HCWs) in Saudi Arabia are a unique population who have had exposures to the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). It follows that HCWs from this country could have pre-existingMERS-CoV antibodies that may either protect from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection or cause false SARS-CoV-2 seropositive results. In this article, we report the seroprevalence of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 among high-risk healthcare workers in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study enrolling 420 high-risk HCWs who are physically in contact with COVID-19 patients in three tertiary hospitals in Riyadh city. The participants were recruited between the 1st of July to the end of December 2020. A 3 ml of the venous blood samples were collected and tested for the presence of IgG antibodies against the spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results

The overall prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in high-risk HCWs was 14.8% based on SARS-CoV-2 IgG testing while only 7.4% were positive by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for viral RNA. Most of the SARS-CoV-2 seropositive HCWs had symptoms and the most frequent symptoms were body aches, fever, cough, loss of smell and taste, and headache. The seroprevalence of MERS-CoV IgG was 1% (4 participants) and only one participant had dual seropositivity against MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Three MERS-CoV positive samples (75%) turned to be negative after using in-house ELISA and none of the MERS-CoV seropositive samples had detectable neutralization activity.

Conclusion

Our SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence results were higher than reported regional seroprevalence studies. This finding was expected and similar to other international findings that targeted high-risk HCWs. Our results provide evidence that the SARS-CoV-2- seropositivity in Saudi Arabia similar to other countries was due to exposure to SARS-CoV-2 rather than MERS-CoV antibody.

Keywords: COVID-19, Seroprevalence, SARS-CoV-2, IgG antibody, Healthcare workers

Introduction

An outbreak of pneumonia of unknown cause was first reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019 [1]. The causative pathogen was found to be a novel coronavirus that is different from other β-coronaviruses associated with the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) [2,3]. The novel virus was officially named by the world health organization (WHO) as SARS-CoV-2 and the manifested disease was termed as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [4]. The confirmed cases have been increasing tremendously and the virus has spread rapidly leading to a global pandemic [5,6]. As of February 22, 2021, a total of 110,974,862 confirmed cases have been identified worldwide, with 2,460,792 fatal cases [7].

During this pandemic, several reports showed an increased risk of developing COVID-19 infection in certain populations including healthcare workers (HCWs) who are the front liners looking after infected critically ill patients [[8], [9], [10]]. The reported risk for COVID-19 infection among HCWs, based on the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, is higher than the normal population reaching around 13% in some countries [11,12]. This risk might cause a global crisis due to the expected shortage of health professionals and ongoing community transmission, especially from asymptomatic workers. For that reason, several measures were taken to decrease the risk for COVID-19 infection among this population during this pandemic to cope with the high number of patients requiring urgent health care. These measures include proper isolation and handling of COVID-19 patients, adherence to personal protective equipment (PPE) protocols, screening HCWs after any unprotected exposure to COVID-19 patients.

Among all HCWs, there is a specific group that might have a higher risk for COVID-19 infection including physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists who are working in Emergency Rooms (ER), Intensive Care Units (ICU), and COVID-19 Admission Wards due to the unavoidable prolonged close contact with infected patients. Our study aimed to explore the risk for COVID-19 infection and the percentage of seropositivity in this unique high-risk group in the setting of potential previous exposure to MERS-CoV infected patients [13]. This study will shed light on protective host immunity in high-risk HCWs during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design and population

This is a cross-sectional seroprevalence study enrolling 420 high-risk HCWs who are working in three tertiary hospitals in Riyadh city. Those hospitals, include King Abdallah Specialist Children Hospital (KASCH), King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC), and Prince Mohammed bin Abdulaziz Hospital (PMAH), were dedicated to treat COVID-19 patients during this pandemic and MERS patients in the previous endemic. All participants signed an informed consent and completed the study questionnaire that covered demographic data, clinical symptoms, and SARS-CoV-2/MERS-CoV reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results [14].

Blood collection and serological testing

A 3 ml blood was drawn from each participant via the venipuncture technique. Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes and plasma was separated and stored at -20℃ degree for analysis. Isolated plasma were tested for the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies specific for S1 unit of the spike protein using the anti-SARS-CoV-2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) commercial kit (Euroimmun, Lubeck, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Additionally, samples were tested for the presence of MERS-CoV IgG antibodies using a MERS-CoV S1 spike ELISA (EI 2604–9601 G kit, Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). Results were semi-quantitatively calculated as the ratio of the OD values of samples over the OD values of a kit calibrator. Ratios above the cut-off-point 1.1 were considered positive as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples, calibrators, positive and negative controls were run in duplicate. The sensitivity and specificity of the Euroimmun kit for samples tested within 10–25 days of onset of symptoms were reported as 97.3% sensitivity and 92.9% specificity for anti-MERS-CoV [15], while 94.4% sensitivity and 99.6% specificity for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies [16].

Real-time polymerase chain reaction assay

Detection of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 were analysed in the clinical laboratories in the different hospitals as reported previously [17,18].

Confirmatory testing

An in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used for detecting IgG against S1 spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV as confirmatory testing. This was followed by pseudotyped viral particles (pp) based neutralization assay, utilizing SARS2pp and MERSpp to evaluate the presence of neutralizing antibodies against both viruses as described in previous reports [13,19,20].

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Categorical data were presented as count and percentage. The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess the association between seroprevalence and other categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association of the main symptoms affecting the seropositive. The level of significance was set at 5%. The binomial exact confidence interval was used to obtain the 95% confidence interval for the seropositive.

Results

From the 1st of July to the end of December 2020, we enrolled 420 high-risk health care worker; including 159 (37.9%) from KASCH, 188 (44.8%) from KAMC and 73 (37.9%) from PMAH The study was recruited 210 (50%) physicians, 189 (45%) nurses, and 21 (5%) respiratory therapists who are working in the ER, ICU, and isolation wards. The demographic and characteristic profiles of the participants were summarized in Table 1 . The majority of participants 189 (45%) were in the age group between 25 to 34 years old. Females represented 57.2%. All included healthcare workers were recruited with variable percentages from departments that have very high exposure to infected patients.

Table 1.

Demographics, symptomatology, and occupational exposure, PCR, seropositive and seronegative among the study participants.

| Variable | Category | n(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <25 | 17 (4) |

| 25–34 | 189 (45) | |

| 35–44 | 122 (29) | |

| 45–54 | 64 (15.2) | |

| 55+ | 28 (6.7) | |

| Gender | Female | 237 (57.2) |

| Male | 177 (42.8) | |

| Hospital | KSASH | 159 (37.9) |

| KAMC | 188 (44.8) | |

| PMAH | 73 (17.4) | |

| Department | ER | 89 (21.2) |

| ICU | 67 (16) | |

| Infectious disease | 33 (7.9) | |

| Respiratory Services | 20 (4.8) | |

| Internal Medicine | 106 (25.2) | |

| Paediatric | 105 (25) | |

| Job | Nurse | 189 (45) |

| Physician | 210 (50) | |

| Respiratory therapist | 21 (5) | |

| IgG antibody for SARS-CoV-2 | Seronegative | 358 (85.2) |

| Seropositive | 62 (14.8) | |

| SARS2 symptoms | Asymptomatic | 293 (69.8) |

| Symptomatic | 127 (30.2) | |

| PCR SARS-CoV-2 | Negative | 285 (67.9) |

| Positive | 31 (7.4) | |

| Not done | 104 (24.8) | |

| IgG antibody for MERS | Seronegative | 416 (99) |

| Seropositive | 4 (1) | |

| MERS PCR | Negative | 61 (14.5) |

| Positive | 0 (0) | |

| Not done | 359 (85.5) |

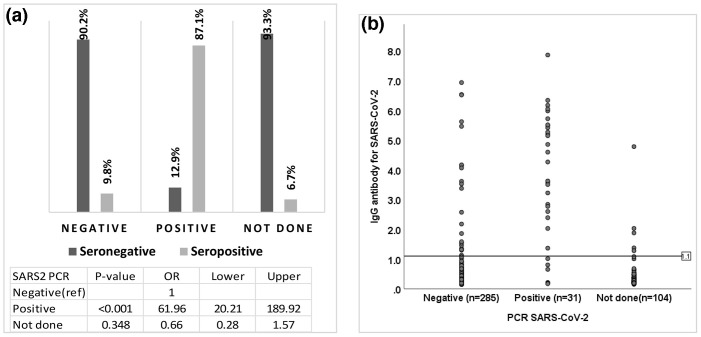

The overall prevalence of COVID-19 infection among the high-risk group was [14.8%; 95%CI = (11.5 %–18.5 %)] based on positive SARS-CoV-2 IgG testing while only [9.8%; 95%CI = (6.8 %–13.6 %)] were positive by PCR. The majority of participants with positive SARS-CoV-2 PCRs were seropositive by SARS-CoV-2 IgG testing while most of the individuals with negative PCR results or no PCR tests had negative IgG testing (Fig. 1 A, B). Subsequently, our targeted population was stratified according to multiple variables including job, department, hospital, gender, and age to determine the significant variances among the individuals with seropositive results. There were no consistent differences observed between participants with from different jobs description, departments, and hospitals with a P-value of 0.69, 0.40, and 0.29, respectively. Furthermore, no observed significant difference was observed for the seropositive IgG among different genders and ages with a P-value of 0.88 and 0.80 (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

A: The association between the PCR result and seroprevalence of IgG SARS-CoV-2 antibody. Odds ratios of seropositive for SARS2 PCR positive compared to negative. B: A dot-plot of individual seroprevalence of IgG to SARS-CoV-2 antibodies distributed by PCR results. Dots represent the value of the participants’ IgG antibody SARS-Cov-2. The horizontal line at 1.1 represents the reference line (cut-off) of seropositive IgG antibodies.

Fig. 2.

The association between seroprevalence and participants’ occupational exposure, departments, hospitals, gender, and age. P-values were calculated using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Lines represent the 95% confidence intervals for the seroprevalence using the Binomial “exact” CI.

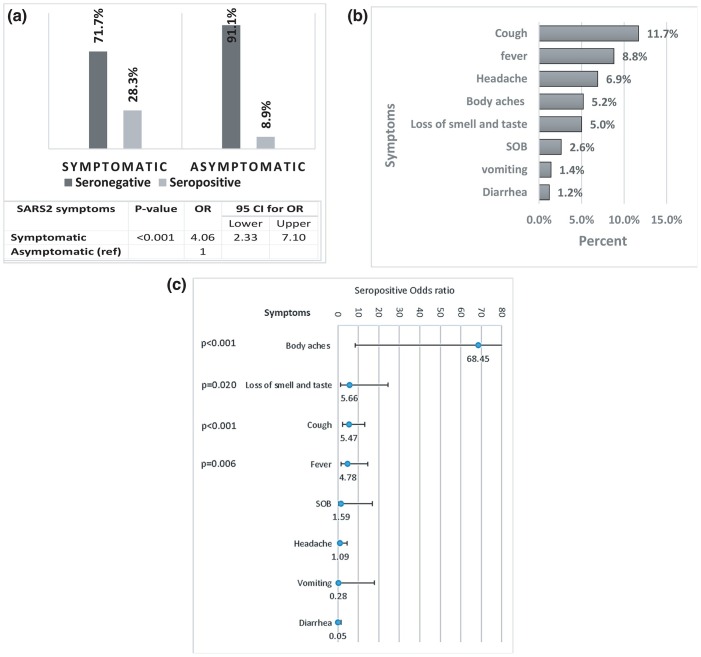

The current results show that asymptomatic HCWs were found to be higher in the seronegative group. When compared to the seropositive group; most of the individuals had symptoms concerning for COVID-19 infection with a significant P-value(<0.001) (Fig. 3 A). The most frequent symptoms that were found to be significant among the seropositive individuals include cough (11.7%, OR 5.47), fever (8.8%, OR 4.78), body aches (5.2%, OR 68.5) and loss of smell and taste (5.0%, OR 5.66) (Fig. 3B, C).

Fig. 3.

A: The association between Symptomatology and seropositive IgG SARS-CoV-2 antibody. The odds ratio of seropositive for symptomatic compared to asymptomatic individuals. B: Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 symptoms among the study participants. C: The association between seropositive IgG SARS-CoV-2 antibody and SARS-CoV-2 symptoms. The lines represent the odds ratios (OR) of seropositive and their associated 95% confidence interval. P-values were generated using multivariable logistics regression with the chi-square test based on the Wald statistics.

MERS-CoV serology was also studied to rule out any possible false-positive SARS-CoV-2 IgG results due to previous MERS infection and the MERS-CoV seroprevalence was found to be less than1% while none of the positive participants reported positive PCR for MERS-CoV in the past (Table 1). Interestingly, one of the four participants had seropositivity against both MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Given this information and due to the variability in sensitivity and specificity among different ELISA kits, we repeated MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 serology for those four MERS-CoV positive samples in comparison to four controls (1 positive control for MERS-CoV, 1 positive control for SARS-CoV-2, and 2 negatives for both) after utilizing an in-house ELISA and we found that 3 samples turned to be negative for MERS-CoV while only one sample continued to be positive for MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 4 A). Subsequently, MERSpp and SAS2pp neutralization assays were performed for 3 random seropositive SARS-CoV-2 and all seropositive MERS-CoV samples. All the selected seropositive SARS-CoV-2 showed a detectable neutralizing activity while none of the MERS-CoV seropositive samples showed any neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

A: In-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). B: Assessment of neutralizing antibody titers among HCWs by pseudotyped viral particles based neutralization assay.

Discussion

COVID-19 is a new disease that has spread to almost all countries leading to a global pandemic. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is one of the countries that was affected by this emerging pathogen in the setting of the previous painful experience during the MERS-CoV endemic. In early March 2020, the first patient with SARS-CoV-2 in Saudi Arabia was reported by the Saudi Authorities and then the number of confirmed cases started to rise and the peak of disease was observed in the period from May to August 2020. As of March 16, 2021, a total of 382,752 confirmed cases have been identified in Saudi Arabia, with 6573 deaths [21]. HCWs in this country have a high-risk of getting COVID-19 infection similar to HCWs from other countries especially those who are working in ER, ICU, or COVID-19 admission wards due to frequent exposures to infected patients. Previous reports showed that the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among HCWs was variable ranging from 2 to 16% [12,[22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]]. These seroprevalence studies are necessitating the protection of HCWs from the emerging high-threat pathogens to limit secondary transmission in healthcare facilities especially from asymptomatic workers and to prevent any unexpected shortage of healthcare professionals.

Our study showed the estimated prevalence of SARS-CoV-2, among high-risk HCWs working in three tertiary hospitals in Riyadh city, was 14.8%. This result is higher than the reported recent study from Saudi Arabia that demonstrated the seroprevalence of COVID-19 among HCWs to be 2.36% [19,30]. The higher seroprevalence estimates in our report might be explained by our population as we targeted only high-risk HCWs and our recruitment was during the peak of COVID-19 infection in Saudi Arabia. Our findings are in agreement with other reports from Ticino, Switzerland that showed high seropositivity (14.07%) among HCWs who are working in high-risk wards where COVID-19 patients were managed [22]. In a study from New York City, the overall calculated COVID-19 seroprevalence in HCWs was 13.7% with observed higher seropositivity in HCWs taking care of patients in the emergency department (17.3%) and hospital units (17.1%) [31]. Our result showed a huge discrepancy in COVID-19 prevalence based on the used test for screening (14.8% based on SARS-CoV-2 IgG testing while only 7.4% based on PCR results). The overall prevalence of COVID-19 infection based on antibody testing might be better than the calculated seroprevalence based on PCR testing for many reasons. Firstly, COVID-19 PCRs were only collected from high-risk individuals including symptomatic persons and close contacts with COVID-19 patients. Secondly, PCR results are affected by the swab technique and the result will be positive only if the viral RNA presents in the upper respiratory tract during the time of the swab. Interestingly, our result revealed that the majority of individuals with positive SARS-CoV-2 PCRs have positive SARS-CoV-2 IgG testing which supports utilizing SARS-CoV-2 IgG for seroprevalence studies.

Our result suggested that there was no significant difference in the risk of COVID-19 infections among high-risk HCWs from different departments or even different hospitals. Additionally, there was no difference in risk between jobs (physician, nurses, respiratory therapist), genders, and ages which indicates the presence of similar exposure and susceptibility to infection between these groups. This could be attributable to the standardization of Saudi’s national guidelines for personal protective equipment (PPE) that were adopted from the WHO guidelines [32]. In agreement with our results, a recent study from Denmark showed no statistically significant difference in the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection among HCWs from different jobs [27].

The clinical spectrum of COVID-19 infection is wide and the majority of HCWs, who had SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, reported symptoms during this epidemic. The most frequent symptoms were cough, followed by other symptoms including fever, headache, body aches, loss of smell and taste, shortness of breath, vomiting, and diarrhea. In concordance with another study from Sweden [24], our results demonstrated a strong association between higher levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and certain symptoms including body aches, cough, fever, and loss of smell and taste. A good proportion of the HCWs in our study reported being free of symptoms despite seropositivity for SRAS-CoV2. The prevalence study in England reported that around 30% were asymptomatic [33] and similar findings were provided by the group from Spain [25]. This high percentage of asymptomatic HCWs means that those individuals will not be identified and isolated which will lead to secondary transmissions in healthcare facilities.

As Saudi Arabia was considered to be an endemic area for MERS-CoV in the last few years, HCWs in this country were exposed to MERS patients during those crises [34]. Some of the HCWs might have protective antibodies against MERS-CoV that may impact any COVID-19 serological study due to the possibility of the presence of protective antibodies against MERS-CoV that might lead to either protection from COVID-19 infection or false SARS-CoV-2 seropositive result. This study showed that the estimated SARS-CoV-2 IgG seropositive antibodies among high-risk HCWs was 14.8% while the seroprevalence of MERS-CoV IgG was less than 1%. This report showed an evidence that the COVID-19 seropositivity in Saudi Arabia, like other countries, was most probably due to previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 rather than MERS-CoV.

Notably, we recorded a significant variability in sensitivity and specificity among different ELISA kits as 3 from a total of 4 participants with seropositive MERS-CoV turned out to be negative after utilizing an in-hose ELISA kit. Interestingly, one participant who had a previous COVID-19 infection that was documented by positive

PCR continued to have positive MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies. This result could be attributable to the presence of an anti-spike SARS-CoV-2 antibody that cross-reacted with other coronaviruses including MERS-CoV. A neutralization assay was performed for all MERS-CoV seropositive samples and few SARS-CoV-2 IgG positive samples as another confirmatory test. Our results demonstrated that all SARS-CoV-2 positively tested samples showed good neutralization activity while none of the MERS-CoV seropositive samples showed any neutralizing antibodies.

The strength of our study is that we recruited only high-risk HCWs from different hospitals including two adult hospitals and one pediatric hospital. All of these HCWs from selected hospitals had previous exposures to patients with MERS-CoV and patients with SRAS-CoV-2. By recruiting those participants, our results provide proof of concept for exploring the possibility of cross-reactive immune responses between the two corona viruses. We acknowledge limitations including the small sample size and the self-reporting bias. Although the limitation due to self-reporting bias is unavoidable in any study requiring the voluntary provision of information.

Conclusion

Herein, we reported a high seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG among high-risk HCWs in Saudi Arabia. This high prevelance was not related to cross-reactivity with MERS-CoV infection. The majority of COVID-19 seropositive HCWs were symptomatic and the most frequent symptoms were cough, fever, headache, body aches, and loss of smell and taste. Obtaining serological screening is useful for the identification of asymptomatic HCWs who might cause unintended ongoing community transmission. All HCWs are encouraged to optimize the use of personal protective equipment to protect them from avoidable infections and to prevent the spread of infections in healthcare facilities.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, No RC20/245/R.

Funding

This project (No RC20/245/R) is funded by King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, No RC20/245/R.

Informed consent

All legal guardians signed an informed consent form to participate in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participated staffs at KASCH, KAMC and PMAH, for their valuable contributions. The authors are also thankful to Mrs Maha Bokhamseen, Mrs Maumonah Hakami and Ms Myaad Saud for providing logistic help and support to conduct this research. This work was supported by King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, No RC20/245/R.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Eng J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Souza J.B., Williamson K.H., Otani T. Playfair JH Early gamma interferon responses in lethal and nonlethal murine blood-stage malaria. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1593–1598. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1593-1598.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vijay R., Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;16:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 209: Data as received by WHO from national authorities by 10:00 CEST, 16 August 2020. 2020, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200816-covid-19-sitrep-209.pdf?sfvrsn=5dde1ca2_2.

- 5.World Health Organization Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 1. 2020, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=20a99c10_4.

- 6.World Health Organization WHO EMRO Biweekly Situation Update on COVID-19- Report #29 2021, emro.who.int/images/stories/coronavirus/documents/covid-19_sitrep_29.pdf?ua=1.

- 7.World Health Organization Weekly epidemiological update - 22 February 2021. 2021, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---16-february-2021.

- 8.Lee H., Goh C. Occupational dermatoses from Personal Protective Equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic in the tropics—a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;35(3):589–596. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livingston E., Desai A., Berkwits M. Sourcing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1912–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng K., Poon B.H., Kiat Puar T.H., Shan Quah J.L., Loh W.J., Wong Y.J., et al. COVID-19 and the risk to health care workers: a case report. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):766–767. doi: 10.7326/L20-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venugopal U., Jilani N., Rabah S., Shariff M.A., Jawed M., Batres A.M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among health care workers in a New York City hospital: a cross-sectional analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldblatt D., Johnson M., Falup-Pecurariu O., Ivaskeviciene I., Spoulou V., Tamm E., et al. Cross sectional prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in health care workers in paediatric facilities in eight countries. J Hosp Infect. 2021;110:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alserehi H.A., Alqunaibet A.M., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Alharbi N.K., Alshukairi A.N., Alanazi K.H., et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia: comparing case and control hospitals. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;99 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection based on CT scan vs RT-PCR: reflecting on experience from MERS-CoV. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:154–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ko J.-H., Müller M., Seok H., Park G., Lee J., Cho S., et al. Suggested new breakpoints of anti-MERS-CoV antibody ELISA titers: performance analysis of serologic tests. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:2179–2186. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3043-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Elslande J., Houben E., Depypere M., Brackenier A., Desmet S., André E., et al. Diagnostic performance of seven rapid IgG/IgM antibody tests and the Euroimmun IgA/IgG ELISA in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1082–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Organization Wh Protocol: real-time RT-PCR assays for the detection of SARS-CoV-2, Institut Pasteur, Paris. World Health Organization, Geneva. Available via https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/real-time-rt-pcr-assays-for-the-detection-of-sars-cov-2-institut-pasteur-paris.pdf. 2020.

- 18.Lu X., Whitaker B., Sakthivel S.K.K., Kamili S., Rose L.E., Lowe L., et al. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay panel for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:67–75. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02533-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alharbi N.K., Alghnam S., Alqaisi A., Albalawi H., Alenazi M.W., Albargawi A.M., et al. 2021. Nationwide seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Saudi Arabia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almasaud A., Alharbi N.K., Hashem A.M. MERS coronavirus. Springer; 2020. Generation of MERS-CoV pseudotyped viral particles for the evaluation of neutralizing antibodies in mammalian sera; pp. 117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saudi Ministry of Health Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): Daily situation report, 16th of March 2021. 2021, https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2021-03-15-007.aspx.

- 22.Piccoli L., Ferrari P., Piumatti G., Jovic S., Rodriguez B.F., Mele F., et al. Risk assessment and seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare workers of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 hospitals in Southern Switzerland. Lancet Regional Health-Europe. 2021;1 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shakiba M., Nazari S.S.H., Mehrabian F., Rezvani S.M., Ghasempour Z. Heidarzadeh A Seroprevalence of COVID-19 virus infection in Guilan province, Iran. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.3201/eid2702.201960. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.26.20079244v1.full.pdf+html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudberg A.-S., Havervall S., Månberg A., Falk A.J., Aguilera K., Ng H., et al. SARS-CoV-2 exposure, symptoms and seroprevalence in healthcare workers in Sweden. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18848-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollán M., Pérez-Gómez B., Pastor-Barriuso R., Oteo J., Hernán M.A., Pérez-Olmeda M., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. Lancet. 2020;396:535–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31483-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pagani G., Conti F., Giacomelli A., Bernacchia D., Rondanin R., Prina A., et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 significantly varies with age: preliminary results from a mass population screening. J Infect. 2020;81:e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iversen K., Bundgaard H., Hasselbalch R.B., Kristensen J.H., Nielsen P.B., Pries-Heje M., et al. Risk of COVID-19 in health-care workers in Denmark: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1401–1408. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30589-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Basteiro A.L., Moncunill G., Tortajada M., Vidal M., Guinovart C., Jimenez A., et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers in a large Spanish reference hospital. Nature communications. 2020;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17318-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferioli M., Cisternino C., Leo V., Pisani L., Palange P., Nava S. Protecting healthcare workers from SARS-CoV-2 infection: practical indications. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29 doi: 10.1183/16000617.0068-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed W.A., Dada A., Alshukairi A.N., Sohrab S.S., Faizo A.A., Tolah A.M., et al. Seroprevalence of neutralizing antibodies to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) among healthcare workers in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2021;33 doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moscola J., Sembajwe G., Jarrett M., Farber B., Chang T., McGinn T., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in health care personnel in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;324:893–895. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization (2020) Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations: scientific brief, 27 March 2020. World Health Organization.

- 33.Clarke C., Prendecki M., Dhutia A., Ali M.A., Sajjad H., Shivakumar O., et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection in hemodialysis patients detected using serologic screening. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1969–1975. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020060827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Alfaraj S.H., Altuwaijri T.A., Memish Z.A. 2017. A cohort-study of patients suspected for MERS-CoV in a referral hospital in Saudi Arabia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]