Abstract

Leukocyte rolling adhesion, facilitated by selectin-mediated interactions, is a highly dynamic process in which cells roll along the endothelial surface of blood vessel walls to reach the site of infection. The most common approach to investigate cell-substrate adhesion is to analyze the cell rolling velocity in response to shear stress changes. It is assumed that changes in rolling velocity indicate changes in adhesion strength. In general, cell rolling velocity is studied at the population level as an average velocity corresponding to given shear stress. However, no statistical investigation has been performed on the instantaneous velocity distribution. In this study, we first developed a method to remove systematic noise and revealed the true velocity distribution to exhibit a log-normal profile. We then demonstrated that the log-normal distribution describes the instantaneous velocity at both the population and single-cell levels across the physiological flow rates. The log-normal parameters capture the cell motion more accurately than the mean and median velocities, which are prone to systematic error. Lastly, we connected the velocity distribution to the molecular adhesion force distribution and showed that the slip-bond regime of the catch-slip behavior of the P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction is responsible for the variation of cell velocity.

Significance

Quantitative analysis of the cell rolling motion is critical in understanding the biophysical mechanisms behind it. Although past studies have examined the average cell rolling velocity under different shear flow rates, the significance of the instantaneous velocity distribution has been overlooked. We developed a method to remove biases from experimental noise and revealed that the velocity distribution of cell rolling adhesion has a log-normal distribution. The parameters describing the log-normal distribution are better descriptors of the cell rolling behavior than traditionally used mean or median velocities. We recommend these parameters to quantify cell rolling behavior in future studies. The shape of the velocity distribution is also significant because it implies the underlying molecular adhesion force responsible for cell rolling is normally distributed. We developed a model to determine the underlying molecular force distribution that gives rise to the cell movement, using only parameters extracted from the cell motion.

Introduction

Rolling adhesion of leukocytes is a critical process in the acute inflammatory response, in which leukocytes roll on endothelial cells lining the blood vessel wall toward the site of inflammation (1). This highly dynamic process involves rapid adhesion bond formation at the leading edge of leukocyte-endothelial contact and breaking at the trailing edge. Many studies on this adhesion system have emerged in the past two decades, highlighting the importance of cell rolling in the inflammatory response and cancer metastasis (2, 3, 4, 5). Additionally, the rolling adhesion was shown to be a promising mechanism to sort cells based on their receptor expressions (6). Therefore, a quantitative description of the rolling behavior is critical to understand the mechanism of rolling adhesion and to provide better predictive power for modeling.

P-, E-, and L-selectins are primarily involved in the rolling adhesion of leukocytes. In particular, the primary mechanism in inflammation relies on the rolling of leukocytes expressing P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) on P- and E-selectin-decorated endothelial cells. To study this rolling behavior, parallel flow chambers with selectin-coated surfaces have been used to mimic the shear flow conditions found in the blood vessels (7). In most previous studies, researchers tracked the cells’ positions via video recording and computed averaged cell velocity in response to shear stress. In these studies, cell rolling velocity generally increased with the shear stress when the cell maintained traction with the surface (7, 8, 9, 10). The unique catch-bond characteristics of P- and E-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction were shown to be crucial for initial attachment and stabilization of the cell rolling, especially as shear stress increased (8,11). Although the mean velocity at the population level has provided insight into the overall cell rolling behavior, not much is known about the instantaneous velocity distribution at the single-cell level. In this study, we showed that the instantaneous rolling velocity distribution follows a log-normal distribution at both the population and single-cell levels. Additionally, we showed that the traditional analysis method reporting mean velocity is prone to systematic errors due to uncertainties during tracking. We developed a method to remove the noise and reveal the underlying velocity distribution. Two parameters of the log-normal distribution are a direct function of shear stress, for which we propose physical interpretations. We argued that these parameters should be used for a more accurate description of cell rolling motion instead of the commonly used mean or median velocity. Lastly, we developed a simple model to quantify molecular adhesion force distribution during cell rolling motion.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HL-60 cells were grown in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C under 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell cultures were grown in 8 mL aliquots in 25 mL tissue culture flasks (10062-868; VWR, Radnor, PA) and were passaged every 3–4 days with a cell/fresh media ratio of 1:4. On experiment days, 1–2 mL of cell culture was withdrawn from the culture flask and spun down in a centrifuge at 350 relative centrifugal force for 3 min at room temperature. The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were resuspended in a cell rolling buffer consisting of Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES for a final pH of 7.4. All media were warmed up in a water bath (37°C) before addition to cell culture, and cells used in the experiment were kept on ice before experiments.

Surface passivation

Glass coverslips and microscope slides used to assemble the parallel flow chamber were passivated with polyethylene glycol (PEG). The 60 × 24 × 0.15 mm coverslips (12-548-5P; Fisherbrand Premium, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 75 × 25 × 1 mm microscope slides (48300-026; VWR) were cleaned with a piranha solution (3:1 concentrated H2SO4/30% H2O2) for 30 min, left at room temperature, and then thoroughly rinsed with Milli-Q water followed by methanol. They were silanized in a 1% aminosilane solution (94 mL methanol, 1 mL 3-(2-aminoethylamino)-propyltrimethoxysilane (1760-24-3; VWR), 5 mL glacial acetic acid) for 1 h at 70°C. Once the silanization was complete, the coverslips were rinsed with methanol followed by water before drying in an oven at 110°C for 20 min. Once cooled to room temperature, the coverslips and slides were passivated with NHS-functionalized PEG (mPEG-SVA, 5k; Laysan Bio, Arab, AL) and a biotinylated derivative (biotin-PEG-SVA, 5k; Laysan Bio) by sandwiching 80 μL of 250 mg/mL PEG solution between aminosilane-treated coverslips and slides. The microscope slides were passivated with only PEG, whereas the coverslips were passivated with a mixture of PEG and biotinylated PEG. Unless otherwise stated, the ratio of PEG/biotinylated PEG was 40:1 for each experiment. The passivation was left to react overnight at room temperature. Then, the PEGylated coverslips and slides were washed with Milli-Q water, dried by blowing compressed nitrogen over the PEGylated surface, and stored at −20°C under a nitrogen atmosphere.

Flow chamber assembly

Flow chambers were constructed with a coverslip, permanent double-sided tape (3M237; Scotch, St. Paul, MN), and a top microscope slide (Fig. S1). A Dremel drill was used to create holes on either end of the slide to create the chamber’s inlets and outlets. Before chamber construction, the drilled top slide and the coverslip were PEG passivated as described above. To create channels in the flow chamber, a laser engraver (Boss Laser, Sanford, FL) was used to cut channels into the double-sided tape. Once the channels were cut, the tape was sandwiched between the coverslip and the slide to create channels with dimensions 0.093 × 53.5 × 2 mm. A custom-made bracket was used to connect tubing to the inlet and outlet of the flow chamber. After chamber construction, the surface was functionalized through a series of protein incubations as described below.

Cell rolling adhesion assay

Cell rolling adhesion assays were performed similarly to previously established (12). The following protein solutions were sequentially injected into the flow chamber for incubation using a micropipette: 100 μg/mL streptavidin (CTL005-01-5MG; Cedarlane, Burlington, Canada), 100 μg/mL biotinylated protein G (ab155724; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and 10.6 μg/mL P-selectin-Fc (137-PS-050; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Each protein was added to the channel(s) at a volume of 40 μL and left to incubate for ∼20 min at room temperature. After each protein incubation, the excess protein was washed out of the chamber with cell rolling buffer. HL-60 cells were resuspended in cell rolling buffer and then pipetted into the channel after the last wash. Then, the flow of cell rolling was controlled with a syringe pump (Pump 11 Elite; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Buffer was flowed through the chamber at specified flow rates to vary the shear stress experienced by the cells rolling on the P-selectin functionalized surface. To ensure a steady flow rate, the outlet tubing was placed in a beaker full of buffer to prevent the buffer from dripping off the end of the tube. The cells were imaged on a custom-built dark-field microscope with a 10× objective, and the video was recorded with a CMOS camera (Ximea xiQ MQ022MG-CM; Ximea, Münster, Germany) at 30 frames per second.

Cell detection and tracking

Custom MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) code was written to detect and track the frame-by-frame position of each cell. The code detects the position of the cells by converting each frame into a binary image through Otsu’s method (13). Each cell is binarized to allow for easy detection of centroid and cell size. Watershed segmentation was used to separate touching cells allowing for the detection of each cell. After thresholding and segmentation, the centroid positions of individual cells were connected to create an array of positions for each cell. This was subsequently used to calculate instantaneous rolling velocities.

Simulated cell rolling videos to test detection and tracking error

Simulated cell rolling videos were created to investigate the impact of detection error on the resulting instantaneous rolling velocity. Each cell was given a log-normal velocity distribution with known parameters μLN and σLN. A random number generator with log-normal distribution was used to create a time series of true instantaneous velocities and positions of the cell. A filled circle was plotted at the true position in each frame. The circle was then subjected to image sharpening and Gaussian filtering to achieve an appearance representative of an HL-60 cell observed on a dark-field microscope. Finally, Gaussian noise was added to the image with a user-defined variance (σ2). The pixel size of the artificial cell(s) matches the experimental data. The simulated video was subjected to the same detection and tracking code used on HL-60 cells. However, in this instance, the true centroid positions and velocities were known.

Results and discussion

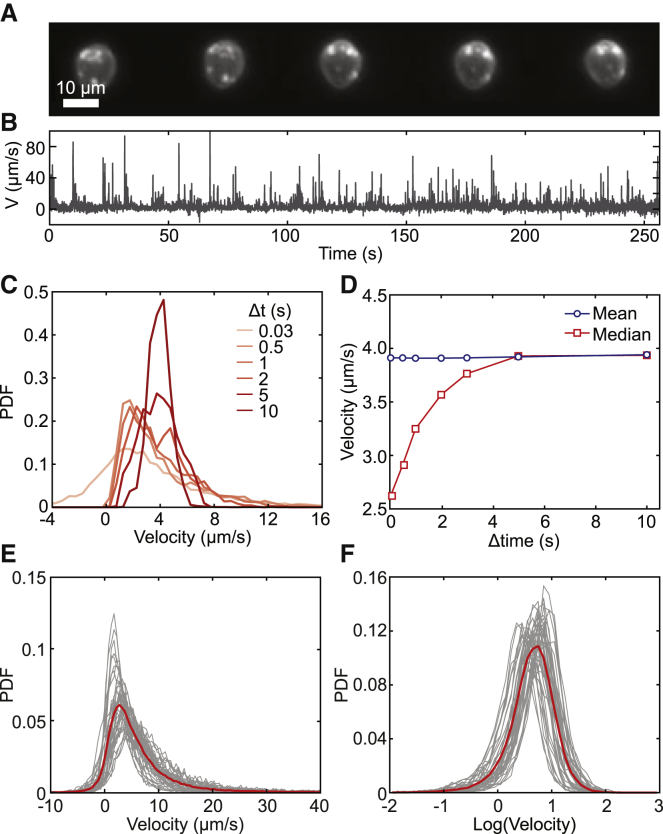

Accurate velocity distribution is critical to determine the underlying biophysical mechanisms of cell motion. Fig. 1 A shows snapshots of a rolling cell taken at 3 s intervals. Although the cell appears to be traveling near-constant velocity, examining the instantaneous velocity at a higher temporal resolution reveals large velocity fluctuations (Fig. 1 B). The instantaneous velocity of a rolling cell is typically determined by video tracking its centroid between consecutive frames and dividing the distance by the time intervals (Δt). Therefore, the detected instantaneous velocity between the two frames is the time-averaged true velocity over Δt. In many studies involving quantitative cell rolling, video tracking was performed at a low frame rate (∼1 fps) or calculated as the mean velocity across the entire field of view or over a considerable period (3,14, 15, 16). The low frame rate strongly biases the asymmetrical velocity distribution with a large spread to a narrow symmetrical distribution around the mean (Fig. 1 C). Because of this averaging, the distribution’s median velocity also converges toward the mean as Δt increases (Fig. 1 D). To reveal the true instantaneous velocity distribution of cell rolling, fast video recording is needed. However, as Δt decreases, the localization error in a cell’s centroid position becomes comparable to the cell’s true movement within the same Δt, introducing an additional source of error in the detected velocity.

Figure 1.

Cell rolling velocity distribution. (A) Dark-field images of an HL-60 cell rolling on a P-selectin-functionalized coverslip showing snapshots at 3 s intervals. (B) Instantaneous rolling velocity over time of a cell rolling under a constant flow rate. (C) The impact of the sampling rate (Δt) on the detected velocity distribution. The instantaneous velocity data were averaged at different Δt ranging from 0.03 to 10 s to show the effect on the observed velocity distribution. (D) Mean and median velocity of the distribution in (C) as a function of Δt. (E) Probability density function (PDF) of the instantaneous rolling velocities of individual cells (gray) and the population (red) (Δt = 0.03 s). (F) PDF of the natural log of instantaneous rolling velocities resembles a normal distribution, hinting at an underlying log-normal velocity distribution. To see this figure in color, go online.

Extracting true velocity distribution

To determine the underlying true velocity distribution of rolling cells, we first analyzed the observed velocity distribution at both the population and single-cell levels. We averaged the probability density function (PDF) of each cell’s velocity distribution to obtain the population-averaged velocity PDF. This method ensures a fair representation of each cell’s behavior in the population-averaged velocity distribution. A common approach in deriving the population velocity distribution is to pool velocity data from all cells with equal weight. This approach biases the population data favoring slow cells, as they stay longer in the field of view and generate more data points. Such bias can lead to up to ∼20% lower averaged detected velocity of the cell population (Fig. S2).

The velocity distribution at both the population and the single-cell levels displayed a biased distribution with tail extended toward higher velocity (Fig. 1 E) and resembles a log-normal distribution (Fig. 1 F) defined by

| (1) |

where v is velocity and μLN and σLN are parameters defining the log-normal distribution.

We noticed that the velocity distribution has a negative component that is significant compared to the mean velocity at low shear stress. Because a log-normal distribution is above 0, understanding the source of this negative velocity is crucial before testing our hypothesis of whether the underlying velocity distribution is log-normal. The apparent negative velocities indicate that cells’ detected positions move against the flow, which is counterintuitive. A similar apparent movement against flow has been observed and attributed to a negative entropy production at short timescales in an optically trapped bead system (17). However, given the adhesion strength between cell and substrate and the high flow velocity of the liquid near the surface, it is unlikely that the negative velocity is due to Brownian diffusion (orders of magnitude lower than what we observed). Consequently, we hypothesized that it is due to the localization errors from video tracking.

To understand the nature of the detection error, we simulated cell rolling videos with cell images and background noise similar to actual experiments. Gaussian white noise was added to the simulated videos with variance in the range of 0.001–0.02. This range corresponds to videos that appear nearly perfect to videos with excessive noise. Therefore, we can assume the experimental background noise is encompassed within the noise we tested. We then analyzed the simulations in the same manner as the real experimental videos (Fig. 2 A). This allowed us to directly compare the detected position against the cell’s true position at different image noise levels. Indeed, subtracting the known true positions from the detected positions revealed a Gaussian error in the detected position (Fig. 2 B). Because cell velocity is calculated by subtracting two detected positions, the cell velocity would also have an error with a Gaussian profile (Fig. 2 C). The magnitude of this error matches the negative velocity observed in cell rolling velocity (Fig. 1 E). As we increased the image noise level in the simulation, the detection error in velocity also increased (Fig. 2, D and E). Assuming a true underlying velocity distribution is log-normal, the observed velocity distribution is then convoluted with the Gaussian detection noise (Fig. 2 F), giving it a negative component observed in experiments (Fig. 1 E). Therefore, the detection error has a significant impact on the PDF of velocity distribution (hence, median velocity) but does not affect the mean velocity as the error is symmetrical around 0.

Figure 2.

Cell detection error masks the real velocity distribution. (A) Centroid detection on a simulated rolling cell showing the detected outline (yellow) and the centroid of the cell (red cross). (B) Centroid detection results (gray) and the true position (red cross) for n = 2365 frames. (C) Gaussian fit to the detected velocity error (vdet − vtrue) from the detected positions in (B). (D) Greater image noise results in a more significant detection error. This effect was observed by changing the variance (σ2) of the added Gaussian noise and then detecting the centroid of the cell. (E) Width (σ) of vdet − vtrue as a function of image noise σ2, showing that detection error increases with increasing image noise. (F) The effect of image noise on cell rolling velocity distribution in comparison to the ground truth. To see this figure in color, go online.

Knowing the noise’s distribution function, we evaluated several methods to correct for this noise to uncover the underlying distribution and statistical parameters (mean, median, μLN, and σLN). We tested methods commonly used by other researchers, including removing negative data points (16) and smoothing the data using a moving average filter (14), against three optimization methods, i.e., genetic algorithm (GA) fit, least-squares (LSQ) fit, and maximal likelihood estimation (MLE). Each method assumes that the detected instantaneous velocity data are log-normal with Gaussian noise centered around 0. The goal of these techniques is to extract the true log-normal parameters from the noisy data. We created a log-normal distribution with Gaussian noise (σ = 1.25, similar to experiments) (Fig. 3 A) to test the method’s effectiveness. As expected, adding symmetrical noise on the asymmetrical distribution skews the median, but not the mean (Fig. 3 B), leading to an ∼9% error in the median using the raw instantaneous velocity. Past studies sampled at a low frame rate or used smoothed velocities to remove the detection noise (14). However, this process introduces large errors in the recovered median velocity (∼35% error), as smoothing converges the data toward the mean (Fig. 3 B) by reshaping the distribution (Fig. 1 C). Other reports have also filtered out negative data points because they were believed to arise from detection errors (16). This leads to an overestimation of both the mean and the median velocities by ∼10 and 20%, respectively (Fig. 3 B). Because the recovery of the median velocity depends on recovering the distribution, the fitting and optimization methods (GA, LSQ, and MLE) are more suitable. After evaluation of these three methods, MLE performed the best, and GA was the least accurate. LSQ performed similarly to MLE in recovering the median but slightly worse in the mean (Fig. 3 B). The greater accuracy in recovering the underlying distribution using the MLE comes at a significantly higher computational cost (∼100× slower than LSQ and ∼2× slower than GA; see Supporting materials and methods for details).

Figure 3.

Extracting parameters from noisy log-normal data. (A) The distribution of log-normal velocity (ground truth) with varying levels of added Gaussian noise. The level of noise is controlled by the SD (σ) of the Gaussian noise. (B) Percentage error in the recovered mean and median velocities by different methods using the same data set and noise level (σ = 1.25). Statistical significance of each processing method was compared to raw (unprocessed) and was assessed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (ns = not significant (p > 0.05), ∗p < 0.05, and ∗∗p < 0.001). (C) Percentage error in the recovered log-normal parameters (μLN and σLN) and the mean and median velocities against the truth, at different levels of noise (σ = 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 3.0) for GA, LSQ, and MLE. Error bars for (B) and (C) represent the SD of replicates (n = 10). The data points for each method were slightly shifted horizontally for clarity, so they do not overlap. To see this figure in color, go online.

To further evaluate the effectiveness of these three methods, we tested how well they recover the underlying distribution (e.g., log-normal parameters μLN and σLN) against varying levels of added noise (with standard deviation (SD) σ) (Fig. 3 A). The data set was created with parameters similar to those found in our cell rolling experiments. As expected, the median velocity calculated directly from the raw data deviates significantly with increasing noise (up to 40% at σ = 3; Fig. 3 C). The MLE remains the best performer (within 10% error; Fig. 3 C) even at the highest noise level tested (σ = 3) that severely distorts the observed velocity distribution (Fig. 3 A). LSQ is comparable to MLE at lower noise levels (σ ≤ 2) but fails at higher noise levels (Fig. 3 C). GA showed the lowest accuracy and precision. Accordingly, the MLE method was used in all subsequent studies.

Tracking noise can be reduced in experiments using higher magnification objectives and high signal/noise imaging methods. A higher magnification reduces tracking noise by projecting a larger cell image over more pixels to achieve better subpixel centroid determination. However, the reduced noise is at the cost of reduced field of view and limited tracking distance of individual cells, limiting single-cell velocity sample size. The dark-field microscopy used in our study offers excellent contrast that enables us to identify cell boundaries with a higher signal/noise ratio and frame rate than fluorescence microscopy using membrane dyes. Although optimization of imaging conditions can reduce tracking noise, it does not eliminate it. This highlights our method’s advantage in that it can recover the underlying velocity distribution regardless of the imaging system’s noise level. Therefore, our ground-truth recovery method can be adapted to process cell rolling data obtained through different imaging conditions, as long as they have sufficient temporal resolution.

Cell rolling velocity distribution is log-normal at both population and single-cell levels

Next, we examined the population-averaged experimental cell rolling velocity distribution at a range of shear stresses in the physiological range (0.04–0.86 Pa). At higher shear stress, the velocity distribution shifts higher, and its spread widens (Fig. 4 A). We applied the MLE method to find the log-normal parameters (μLN and σLN) describing the underlying distribution. The fit to the velocity distribution and its residual values are shown in Fig. 4 A, showing that a log-normal distribution with Gaussian noise best describes the cell rolling velocity distribution. Goodness of fit was evaluated by graphical comparison (Fig. S3) and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (Table S1). Hence, the behavior of cell rolling can be more accurately described by the log-normal parameters μLN and σLN than the mean or median velocities, which are prone to errors because of both data averaging and tracking errors. Fig. 4 B shows that although μLN increases nonlinearly with shear stress, σLN decreases. For a log-normal distribution, the median and mean velocities can be explicitly expressed as exp(μLN) and exp(μLN+σLN/2), respectively. As shear stress increases, the increase of both median and mean velocity tapers off, which was previously described as the shear-induced stabilization of cell rolling (18).

Figure 4.

Cell rolling velocity at the population level. (A) MLE fit to instantaneous velocity distribution of HL-60 cell population rolling at different shear stresses. The top plot shows all the velocity PDFs at shear stresses between 0.04 and 0.86 Pa. The plots below are the PDF of velocity and the corresponding residual (R) of fits from selected shear stress. (B) Log-normal parameters (μLN and σLN) extracted from the fit at each shear stress. Error bars are the 95% confidence intervals of the fit. (C) Extracted mean and median rolling velocity at each shear stress calculated with the log-normal parameters. To see this figure in color, go online.

We next applied the MLE algorithm to single-cell experiments in which increasing shear stresses were applied in steps (Fig. 5 A). This allows us to track individual cells and understand how the velocity distribution evolves at the single-cell level, removing potential bias from the average of a heterogeneous population. Indeed, for each cell, the velocity distributions over a wide range of shear stresses (0.09–1.38 Pa) remain log-normal (Fig. 5 B). This indicates a common underlying biophysical mechanism that generates such distributions over the entire shear stress range. The fact that the single-cell velocity distribution is log-normal is the underlying reason behind the population level log-normal distribution. This is because the sum of log-normal distributions (single-cell data) limits toward log-normal (population) (19). Similar to the population-averaged result, μLN increases with shear stress, whereas σLN decreases (Fig. 5 C). For every cell that we tracked, both μLN and σLN followed the same shear-stress-dependent trend (Fig. 5 C). To identify the source of the variation in μLN and σLN among single cells, we investigated the effect of cell size and receptor density. Fig. 5 D shows a scatter plot of σLN against μLN for each cell at different shear stresses with cell size indicated by the marker size, which shows no clear indication that cell size systematically affects σLN and μLN. Although larger cells experience greater force from shear flow than smaller cells, they also have a larger surface contact area and more adhesion molecules. If cell-surface receptor density remains relatively constant for cells of different sizes, then the number of adhesion tethers will also scale with the surface contact area. Because both shear force and the contact area scale to the square of cell size, the contribution of shear force per adhesion tether remains the same regardless of cell size. This is likely what contributes to the fact that we did not observe any significant velocity dependencies on cell size (Fig. 5 D; Fig. S4). However, when we decreased the surface density of receptors on the substrate by a factor of 2, μLN shifted up, indicating a higher rolling velocity across the entire shear stress range (Fig. 5 E). Hence, the velocity variation among single cells is due to the heterogeneity in receptor density rather than cell size. Therefore, σLN and μLN from single-cell rolling could be useful parameters in cell-screening applications to decouple behavior due to receptor density from cell sizes.

Figure 5.

Single-cell rolling velocities. (A) Single cells were rolled at different shear stresses by applying a flow-series step function. The top figure shows the shear stress (τ) steps applied to the rolling cells over time. The bottom figure shows the instantaneous rolling velocity (v) of an individual cell over time and the average rolling velocity (red) at each shear stress. (B) MLE fit to a single cell’s velocity distribution corresponding to the applied shear stress shown in (A). (C) The extracted log-normal parameters from 24 cells (gray) and the average (blue or red) of the parameters at each shear stress. Error bars represent SD. (D) The relationship between σLN and μLN for single cells (n = 24) at different shear stresses and cell diameters (Ø). (E) μLN extracted with MLE from HL-60 cell rolling population velocity distributions at different shear stresses and different surface densities. The density of P-selectin on the coverslip surface was controlled by the ratio of polyethylene glycol (PEG)/biotinylated polyethylene glycol (PEG-biotin), as the biotin anchors P-selectin to the surface through a streptavidin-biotin interaction. Cells were rolled on the surface with a PEG/PEG-biotin ratio of either 20:1 or 40:1. To see this figure in color, go online.

Determining molecular force distribution from rolling velocity distribution

Our analysis of the instantaneous velocity yields two descriptive parameters of the underlying log-normal distribution, μLN and σLN, for each cell at given shear stress. μLN is directly related to the median velocity and increases with shear stress, as expected. σLN describes the skewness and kurtosis of the velocity distribution, both of which decrease with shear stress. This may look counterintuitive from the raw velocity distribution (Figs 4A and 5B), as the apparent distribution is more symmetrical at low shear stress. However, as discussed above, the seemingly symmetrical distribution at low shear stress is primarily due to the localization noise. The underlying distribution is indeed more skewed at lower shear stress. This is likely because as shear stress increases, cells traveling at higher velocity cover a greater distance, hence more P-selectin/PSGL-1 interactions over the same sampling period (Δt) defined by the video frame rate. In addition, cells flatten under increased shear, leading to even more adhesive interaction (20). The ensemble average of more adhesion interactions within Δt leads to a convergence toward a more symmetrical distribution, decreasing σLN. Although the variation in a cell’s rolling velocity in vivo can be attributed to the variation of P-selectin expression levels on the endothelium (21), our in vitro system has a uniform surface density. Hence, a single cell’s velocity variation can be attributed to the stochastic dissociation of adhesion bonds and the random receptor-ligand distribution on the cell and substrate surface.

Another consideration in our system is the tether used to immobilize P-selectin on the surface. P-selectin is bound to the surface through a series of interactions involving ProtG-Fc and streptavidin-biotin interactions. Although this tether contains noncovalent bonds, the rupturable components have unbinding forces much larger than the P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction and is unlikely to affect the rolling adhesion behavior. It has been shown that the streptavidin-biotin and ProtG-Fc interactions have unbinding forces in the range of 300–400 pN (22) and >80 pN (23), respectively. This is significantly larger than the reported unbinding forces of P-selectin/PSGL-1, which are in the <60 pN range (Fig. 6 A; (8,24)). Therefore, the P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction in each tether will be the first to rupture. Hence, rolling cells predominantly experience the adhesion characteristics of the P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction.

Figure 6.

Inferring molecular force distribution. (A). The force-dependent bond lifetime of P-selectin/PSGL-1, according to (24). (B) The natural log of the off rate of P-selectin/PSGL-1 as a function of force, according to Eq. 4. The curve is approximately linear between 0 and 10 pN and >15 pN; a Gaussian distribution of ln(koff) (centered around μLN +ln(ρ) with a width of σLN) within either of these regions maps to a molecular force distribution that is normally distributed (centered around Fmean with a spread of Fstdev). (C and D) μLN and σLN as functions of Fmean and Fstdev. (E) Overlay of contour lines from (C) (dashed lines) and (D) (solid lines) at μLN- and σLN-values corresponding to single-cell rolling velocity distribution from Fig. 5C at various shear stresses (0.09–1.38 Pa, color-coded). The intersections of the μLN and σLN contour lines (hollow circles) correspond to the parameters (Fmean and Fstdev) describing a normally distributed P-selectin/PSGL-1 adhesion force. (F) Reconstructed molecular adhesion force distribution according to the intersections in (E). (G) Fmean as a function of shear stress; error bars are Fstdev. To see this figure in color, go online.

To understand the nature of the log-normal distribution and how it evolves with shear stress, we consider a simple relation that relates the cell velocity (v) to the dynamic breaking of cell-surface receptors:

| (2) |

where koff is the off rate of the adhesion interaction and davg is the average distance between adjacent adhesion receptors in the direction of movement, which is inversely proportional to the linear receptor surface density ρ (μm−1) projected along the flow direction. Here, we do not consider velocity changes due to hydrodynamic acceleration of the cell between tether-breaking events. Rather, the cell maintains a steady velocity distribution within each Δt under a quasi-steady-state condition. Given that v has a log-normal distribution, the natural log of v

| (3) |

so that ln(v) is a normal distribution centered around μLN with an SD of σLN.

Equation 3 allows us to directly relate the distribution of ln(v) to koff and ρ. First, we consider the distribution of ρ. Assuming a random distribution of receptors and microvilli on the cell surface, the density distribution within the cell-surface contact area should follow a Poisson distribution. Based on previous studies (9,25), the average number of adhesion bonds on the cell surface ranges between 1000 and 5000 with a contact area ∼10–20% of the total cell-surface area, which considers the elastic deformation of cells under shear stress. The value of ln(ρ) ranges from 3.5 to 4.7, and the SD (σρ) of ln(ρ) ranges from 0.029 to 0.096. Given that the SD (σLN) of ln(v) is in the 0.6–2 range (for the shear stress we used), the majority of contribution (>99%) to the SD of ln(v) would come from the SD (σkoff) of ln(koff), as σLN2 = σρ2 + σkoff2. Therefore, koff is the major contributor to the shape of the ln(v) distribution.

Next, we determined the distribution of molecular adhesion force based on its relationship with koff. We have previously demonstrated that our surface passivation and functionalization enable specific interaction between the P-selectin on the substrate and PSGL-1 on leukocytes. This adhesion bond exhibits a catch-slip behavior, as has been well documented in the past (8,18,26,27). The force-dependent dissociation rate koff(F) has been previously characterized (24) by

| (4) |

where kc0 and ks0 are the zero-force rate constant for the catch and slip regimes, respectively; β = 1/kBT; and xc and xs are the distances to energy barriers corresponding to the catch and slip regimes, with xc < 0. The values from Pereverzov et al. (24) were used for each parameter, resulting in a force-dependent bond lifetime (τ = 1/koff) characteristic of a catch-slip bond (Fig. 6 A).

Because koff is modeled by the sum of two exponential functions (Eq. 4) at forces outside of the catch-to-slip transition region (∼10–15 pN), ln(koff) scales linearly to force (Fig. 6 B). In the low-force region (0–10 pN), a negative slope is characteristic of a catch-bond behavior. In contrast, at the high-force region (>15 pN), the positive slope indicates a slip-bond behavior (Fig. 6 B). Following from our discussion above that ln(koff) is the major contributor to the shape of ln(v), it should also have a normal distribution. This implies that if the molecular adhesion force during cell rolling falls within either the catch-only or slip-only regimes, it should also have a normal distribution (Fig. 6 B). Therefore, combining Eqs. 3 and 4, the molecular force distribution (Fmean and Fstdev) can be numerically evaluated at any given μLN or σLN (Fig. 6, B–D). The surfaces (Fig. 6, C and D) are not a monotonic function of Fmean and Fstdev because of the adhesion interaction’s catch-slip characteristic.

The unique pair of Fmean and Fstdev that gives rise to a given pair of μLN and σLN was determined by the intersection of contour lines (Fig. 6 E) corresponding to the specific μLN and σLN. Taking the values of μLN and σLN from single-cell data (Fig. 5 C), we were able to determine the Fmean and Fstdev at different shear stresses (Fig. 6 E; Table S3) and reconstruct their molecular force distribution (Fig. 6 F). We observed that the molecular force plateaus as shear stress increases (Fig. 6 G), suggesting that biomechanical mechanisms stabilize molecular adhesion, hence rolling adhesion at high shear stress. Although the shear-induced stabilization of cell rolling is most likely due to the catch-slip characteristics of P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction at lower shear stress, the elastic deformation (flattening) of cells and viscoelastic stretching of the microvilli (28) further stabilize the rolling of cells at high shear stress. Using our model, the estimated mean molecular forces reside within the slip-bond regime, suggesting that the slip-bond characteristics are responsible for the observed distribution of instantaneous velocity fluctuations.

The findings presented in this study are specific to a widely used in vitro rolling adhesion model system using a parallel-plate flow chamber. The system explores leukocytes’ rolling motion on a homogeneous, rigid, and flat surface, coated only by adhesion molecules (such as P-selectin). This idealized model system has been used to understand how specific molecular interactions lead to the observed cell movement and applications such as cell sorting (3,6). The methodology developed here is applicable to study cell rolling on other adhesion molecules and their combined effect in a controlled environment. A number of factors complicate the velocity distribution in vivo. First, the distribution of adhesion molecules is not uniform. Studies have shown that selectin expression is heterogeneous and appears punctate on the surface of endothelial cells (21). Second, the interactions in vivo are complex and involve different types of adhesion molecules throughout the rolling adhesion cascade (1). This makes it difficult to isolate any segment of the cell trajectory purely because of the adhesion of one type of adhesion molecule. The endothelial monolayer surface is also compliant and not flat, changing both the geometry and contact area as leukocytes roll across them. Lastly, blood flow is pulsatile in vivo instead of the constant flow we used in the model system. Hence, it is challenging to relate velocity distribution measured in vitro to in vivo directly. However, this does not diminish the value for this type of analysis for in vitro models, as they are used extensively to allow us to understand biological and disease processes in a controlled manner.

Conclusion

This article showed that the velocity distribution of cell rolling adhesion could be strongly influenced by the frame rate and detection noise of video recordings. Using a maximal likelihood estimation method, we demonstrated that the experimental noise can be removed to reveal the underlying true velocity distribution of cell rolling. This distribution is well fitted by a log-normal function and is characterized by two parameters: μLN and σLN. The log-normal distribution of cell velocity was verified across the entire physiological range of shear stress at both the population and single-cell levels. In particular, the receptor surface density has a significantly larger effect on μLN and σLN than cell size, providing a potential parameter for cell-screening applications. The observed log-normal distribution in velocity indicates a normally distributed molecular adhesion force between P-selectin and PSGL-1 under a steady-state assumption. Through a simple model, we can determine the distribution of the molecular adhesion force from any rolling velocity distribution. We showed that the molecular force responsible for the fluctuation of cell rolling velocity in the physiological range is mostly due to the dissociation characteristics of the slip-bond region of the P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction. Through our model, the log-normally distributed velocity suggested a normally distributed molecular force as the origin of the cell rolling velocity profile in vitro. At the moment, we do not have direct experimental measurements of the molecular force distribution to validate our model. Although direct measurement of molecular force has been demonstrated using molecular force probes, applying them in the rolling adhesion system still presents significant challenges. This includes the limited force dynamic range of existing probes and high sensitivity detection because of each bond’s short adhesion time (29). A recent study measuring the molecular force of bead rolling might potentially offer a solution to this (30). Although not measuring native P-selectin/PSGL-1 interactions, similar direct in vivo measurements of molecular force could help validate existing models and provide new insights into mechanisms regulating their behavior.

Author contributions

A.B.Y., Y.M., V.K., and I.T.S.L. conceptualized the study. A.B.Y. and Y.M. performed the experiments. A.B.Y., Y.M., V.K., and I.T.S.L. analyzed the data. V.K. developed the MLE method. I.T.S.L. developed the LSQ method and modeling. A.B.Y. developed the simulation and performed comparative studies. Y.M. and V.K. performed statistical tests. A.B.Y. and I.T.S.L. prepared the figures. All authors participated in drafting the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Canada Foundation of Innovation (CFI 35492), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2017-04407), New Frontiers in Research Fund (NFRFE-2018-00969), Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (SCH-2020-0559), and the University of British Columbia Eminence Fund.

Editor: Philip LeDuc.

Footnotes

Adam B. Yasunaga and Yousif Murad contributed equally to this work.

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.04.021.

Supporting material

References

- 1.McEver R.P., Zhu C. Rolling cell adhesion. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;26:363–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geng Y., Marshall J.R., King M.R. Glycomechanics of the metastatic cascade: tumor cell-endothelial cell interactions in the circulation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012;40:790–805. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards E.E., Oh J., Thomas S.N. P-, but not E- or L-, selectin-mediated rolling adhesion persistence in hemodynamic flow diverges between metastatic and leukocytic cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:83585–83601. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blankenberg S., Barbaux S., Tiret L. Adhesion molecules and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H.B., Wang J.T., Geng J.G. P-selectin primes leukocyte integrin activation during inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:882–892. doi: 10.1038/ni1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi S., Karp J.M., Karnik R. Cell sorting by deterministic cell rolling. Lab Chip. 2012;12:1427–1430. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21225k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li I.T.S., Ha T., Chemla Y.R. Mapping cell surface adhesion by rotation tracking and adhesion footprinting. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44502. doi: 10.1038/srep44502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall B.T., Long M., Zhu C. Direct observation of catch bonds involving cell-adhesion molecules. Nature. 2003;423:190–193. doi: 10.1038/nature01605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korn C.B., Schwarz U.S. Dynamic states of cells adhering in shear flow: from slipping to rolling. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2008;77:041904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.77.041904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang K.C., Tees D.F., Hammer D.A. The state diagram for cell adhesion under flow: leukocyte rolling and firm adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:11262–11267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200240897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas W. Catch bonds in adhesion. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2008;10:39–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X., Rahil Z., Ha T. Constructing modular and universal single molecule tension sensor using protein G to study mechano-sensitive receptors. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21584. doi: 10.1038/srep21584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1979;9:62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mondal N., Stolfa G., Neelamegham S. Glycosphingolipids on human myeloid cells stabilize E-selectin-dependent rolling in the multistep leukocyte adhesion cascade. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016;36:718–727. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yasmin-Karim S., King M.R., Lee Y.F. E-selectin ligand-1 controls circulating prostate cancer cell rolling/adhesion and metastasis. Oncotarget. 2014;5:12097–12110. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh J., Edwards E.E., Thomas S.N. Analytical cell adhesion chromatography reveals impaired persistence of metastatic cell rolling adhesion to P-selectin. J. Cell Sci. 2015;128:3731–3743. doi: 10.1242/jcs.166439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang G.M., Sevick E.M., Evans D.J. Experimental demonstration of violations of the second law of thermodynamics for small systems and short time scales. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:050601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beste M.T., Hammer D.A. Selectin catch-slip kinetics encode shear threshold adhesive behavior of rolling leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20716–20721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808213105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell R.L. Permanence of the log-normal distribution. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1968;58:1267–1272. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundd P., Pospieszalska M.K., Ley K. Neutrophil rolling at high shear: flattening, catch bond behavior, tethers and slings. Mol. Immunol. 2013;55:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim M.B., Sarelius I.H. Role of shear forces and adhesion molecule distribution on P-selectin-mediated leukocyte rolling in postcapillary venules. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;287:H2705–H2711. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00448.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sedlak S.M., Schendel L.C., Bernardi R.C. Streptavidin/biotin: tethering geometry defines unbinding mechanics. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaay5999. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgos-Bravo F., Figueroa N.L., Leyton L. Single-molecule measurements of the effect of force on Thy-1/αvβ3-integrin interaction using nonpurified proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2018;29:326–338. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-03-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereverzev Y.V., Prezhdo O.V., Thomas W.E. The two-pathway model for the catch-slip transition in biological adhesion. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1446–1454. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pappu V., Bagchi P. 3D computational modeling and simulation of leukocyte rolling adhesion and deformation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2008;38:738–753. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snook J.H., Guilford W.H. The effects of load on E-selectin bond rupture and bond formation. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2010;3:128–138. doi: 10.1007/s12195-010-0110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yago T., Wu J., McEver R.P. Catch bonds govern adhesion through L-selectin at threshold shear. J. Cell Biol. 2004;166:913–923. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pospieszalska M.K., Lasiecka I., Ley K. Cell protrusions and tethers: a unified approach. Biophys. J. 2011;100:1697–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasunaga A., Murad Y., Li I.T.S. Quantifying molecular tension-classifications, interpretations and limitations of force sensors. Phys. Biol. 2019;17:011001. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/ab38ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yasunaga A.B., Li I.T.S. Quantification of fast molecular adhesion by fluorescence footprinting. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.01.05.425475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.