Abstract

In the early stage of Drosophila embryogenesis, DNA replication initiates at unspecified sites in the chromosome. In contrast, DNA replication initiates in specified regions in cultured cells. We investigated when and where the initiation regions are specified during embryogenesis and compared them with those observed in cultured cells by two-dimensional gel methods. In the DNA polymerase α gene (DNApolα) locus, where an initiation region, oriDα, had been identified in cultured Kc cells, repression of origin activity in the coding region was detected after formation of cellular blastoderms, and the range of the initiation region had become confined by 5 h after fertilization. During this work we identified other initiation regions between oriDα and the Drosophila E2F gene (dE2F) downstream of DNApolα. At least four initiation regions showing replication bubbles were identified in the 65-kb DNApolα-dE2F locus in 5-h embryos, but only two were observed in Kc cells. These results suggest that the specification levels of origin usage in 5-h embryos are in the intermediate state compared to those in more differentiated cells. Further, we found a spatial correlation between the active promoter regions for dE2F and the active initiation zones of replication. In 5-h embryos, two known transcripts differing in their first exons were expressed, and two regions close to the respective promoter regions for both transcripts functioned as replication origins. In Kc cells, only one transcript was expressed and functional replication origins were observed only in the region including the promoter region for this transcript.

Many observations indicate that DNA replication is not initiated at random sites but rather within specified chromosomal regions in metazoan somatic cells or cultured cells, although the DNA structures essential for initiation of DNA replication in higher eukaryotes remain to be clarified (see reference 8 for a review). In contrast, initiation sites are not specified to the same degree in early embryos of Drosophila melanogaster (36) and Xenopus laevis (23).

We previously identified an initiation zone of replication, oriDα, located downstream of the gene encoding the 180-kDa subunit of DNA polymerase α (DNApolα) in cultured Kc cells from D. melanogaster (38). We were unable to find other initiation regions within the 40-kb region from oriDα to DNApolα and its upstream region (35, 38). While cultured Kc cells duplicate in approximately 24 h and their S phase lasts for about 8 h, nuclei in early embryos of Drosophila duplicate their DNA in 10 min. Embryogenesis of Drosophila is started by fertilization that occurs at the time of oviposition. The first 2 h of embryogenesis consists of 13 cycles of rapid and almost synchronous nuclear divisions that have only M and S phases (32) (see Fig. 1). In this syncytium stage, the whole genome must be replicated within 5 to 6 min (17), but the rate of replication fork movement does not change from that in cultured cells (4). One solution to this problem is that rapidly dividing nuclei shorten their replicons by using many more replication origins than do slowly replicating cells. Replicon size in the syncytium stage of embryos was estimated to be about 8 kb, while that in Kc cells was about 40 kb (4). Our previous data, obtained by two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis, coincided with this notion (36). No specific initiation sites were detected within the 5-kb repeating unit of the histone genes, and the average spacing between replication origins in the histone gene repeats was estimated to be about 8 kb in embryos collected between 1 and 2 h after oviposition. Replication bubbles were observed in most fragments derived from a 40-kb single-copy chromosomal region. Thus, DNA replication in the early stages of embryogenesis seems to initiate at numerous sites with little local specificity.

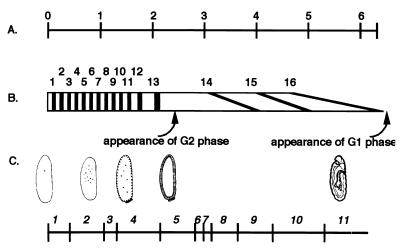

FIG. 1.

Early embryogenesis of D. melanogaster. The stages of embryos analyzed in this work are shown. (A) Time after fertilization. Eggs were staged for x h after 1-h collection at 25°C (see text). (B) Mitotic cycles at 25°C. Mitotic phases are shown by filled rectangles, and interphases are represented by open rectangles. (C) Developmental stages as defined by Foe and Alberts (17).

After syncytium formation by 13 cycles of nuclear division, cytokinesis takes place to form a cellular blastoderm. The first G2 phase appears from the 14th cell cycle. Zygotic transcription is first detectable during cycle 11 or 12 but reaches maximal activation during late cycle 14 (11). Thereafter, the cell cycle time and duration of the S phase within each cell cycle lengthen and become diverse. After the 16th mitosis, most cells stop proliferation and are arrested in G1 phase, which is about 7 h after fertilization at 25°C (17, 32).

These observations prompted us to examine when specification of the initiation regions starts and is established during Drosophila embryogenesis and whether or not the initiation regions selected in embryos are the same as those observed in cultured Kc cells. The chromosomal region initially studied in this work was the DNApolα locus, where we had identified a replication initiation region (oriDα) in Kc cells (38). During this work, we found that the Drosophila homologue of the E2F gene (dE2F) was located downstream of DNApolα. Initiation sites in the dE2F locus were also compared between embryos and cultured cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila eggs and cultured cells.

Wild-type D. melanogaster Oregon R eggs were collected and stored essentially as described previously (36). Eggs were collected for 1 h at 25°C and staged for several hours at 25°C. For convenience, eggs staged for x h after 1-h collection were called x-h embryos. According to Foe and Alberts (17), 1-h embryos are syncytia in the stages from mitotic cycles 8 to 13 and 2-h embryos are mainly cellular blastoderms in cycle 14. The 14th mitosis takes place from 3 to 4 h after fertilization, the 15th from 4 to 5 h after fertilization, and the 16th from 4.5 to 6.5 h after fertilization (Fig. 1).

D. melanogaster Kc cells were grown at 25°C in a Spinner flask settled in a 100% air incubator with M3 medium (Sigma) adjusted to pH 6.8 with Tris (base) and supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. Exponentially growing cells at a density of approximately 2 × 106 cells/ml were harvested by centrifugation at 400 × g for 10 min at 4°C, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −75°C until use.

DNA clones.

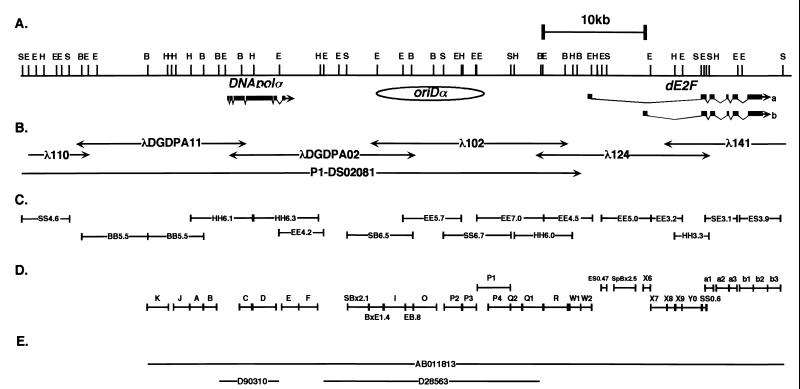

Lambda clones (λ124 and λ141) containing the region next to the oriDα region were screened from a genomic library of D. melanogaster Oregon R provided by Y. Nishida. The previously isolated λ102 (38) was used as a probe to isolate λ124, and then λ124 was used for the isolation of λ141. Subfragments were recloned into pBluescript II SK− plasmids. The locations of these clones are shown in Fig. 2B.

FIG. 2.

Maps of the chromosomal region analyzed in this study. (A) Physical and genetic maps. Direction of transcription of DNApolα (20, 28) and dE2F (9, 31, 34) is from left to right. Transcripts a and b of dE2F correspond to cDNAs reported by Ohtani and Nevins (31) and by Dynlacht et al. (9), respectively. Exons are shown by boxes, and introns are shown by narrow bent lines. The initiation region oriDα is represented by an oval. B; BamHI, E; EcoRI, H; HindIII, S; SalI. (B) Genomic clones. Lambda clones λ110, λDGDPA11, λDGDPA02, and λ102 were described before (20, 38), and λ124 and λ141 were newly isolated. The location of a P1 clone, DS02081 (15), is shown for reference to the genomic position. The approximate position of the right end of DS02081 was determined by Southern hybridization. The STS probe Dm1574 found in DS02081 was located about 10 kb to the left from the left end of this map. (C) Fragments and probes used for N/N 2D analysis. (D) Probes used for hybridization of N/A 2D gels. (E) Sequences registered in the database. The sequence registered as AB011813 was compiled from newly determined sequences and from the previously reported genomic sequences for the DNApolα region (nucleotides 1 to 5737 from D90310) (20) and the oriDα region (D28563) (38).

DNA sequencing.

DNA fragments to be sequenced were cloned into pBluescript II SK−, and their nested deletions were generated with a double-strand Nested Deletion Kit (Pharmacia) for both directions. Plasmid DNA was prepared with a QIAprep Spin Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). Double-stranded DNA was directly submitted to a dideoxy reaction with primer M3 or RV (Takara Shuzo) and an ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Perkin-Elmer). DNA sequencing was conducted with an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer), and the sequence data were assembled with the program AutoAssembler (Perkin-Elmer).

The sequence determined here was compiled from the following sequences: a new 7-kb sequence corresponding to the upstream region of DNApolα, a 5.7-kb genomic sequence of DNApolα (nucleotides 1 to 5737 from accession no. D90310), a new 4.1-kb sequence including a gap between D90310 and D28563, a 21-kb sequence which includes oriDα (accession no. D28563), and a new 27-kb sequence which includes dE2F.

2D gel electrophoresis.

DNA from 1-h embryos was prepared by protocol A, as described previously (37). Total DNA was subjected to 2D gel analysis without enrichment of replication intermediates. DNA from older embryos was prepared as follows. Embryos were suspended in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 25 mM KCl, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.35 M sucrose and homogenized by a Dounce-type homogenizer (pestle B) at 4°C to release the cells. The homogenates were filtered through two layers of Miracloth (Calbiochem), and the cells were collected by centrifugation at 700 × g for 15 min at 4°C. These cells were washed once with buffer A, consisting of 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.05 mM spermine, 0.125 mM spermidine, 0.5% β-thiodiglycol, and 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and then suspended in 50 volumes of buffer A to a cell density of about 5 × 107 cells/ml. Kc cells cultured and stored as described above were suspended in buffer A at 5 × 107 cells/ml. Cells prepared from embryos and Kc cells were encapsulated in micro-agarose beads, and DNA was prepared by protocol B, as described in a previous paper (37). DNA of Kc cells and older embryos was enriched for replication intermediates by chromatography on benzoylated naphthoylated DEAE cellulose (Sigma) columns before 2D gel analysis.

Neutral/neutral (N/N) 2D gel electrophoretic analysis of replication intermediates (5) was performed as described previously (38) by using 5 μg of total DNA from 1-h embryos or replication intermediates enriched from 50 or 200 μg of DNA from later-stage embryos or Kc cells, respectively. Neutral/alkaline (N/A) 2D gel electrophoretic analysis of replication intermediates (21) was performed as described previously (38) by using replication intermediates enriched from 50 μg of DNA from embryos or Kc cells.

Southern hybridization was carried out as described previously (38) except that probes were radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP to a specific activity of 1 × 109 to 2 × 109 dpm/μg of DNA by using a Random Primer DNA labeling kit, version 2 (Takara Shuzo), and purified through a ProbeQuant G-50 Micro Column (Pharmacia). Probes used in N/N 2D gel analysis were restriction fragments to be detected (Fig. 2C) or their subfragments. The probes used in N/A 2D gel analysis are shown in Fig. 2D, and the left, central, and right probes for the respective restriction fragments were as follows: BB5.5, K (BamHI-HindIII, 2.1 kb), J (HindIII-HindIII, 1.6 kb), and A (HindIII-BamHI, 1.2 kb); HH6.1, A, B (BamHI-BamHI, 1.3 kb), and C (BamHI-HindIII, 1.2 kb); HH6.3, D (HindIII-EcoRI, 2.3 kb), E (PstI-PstI, 1.7 kb), and F (PstI-HindIII, 1.85 kb); SB6.5, SBx2.1 (SalI-BstXI, 2.1 kb), BxE1.4 (BstXI-EcoRI, 1.4 kb), and I (EcoRI-EcoRI, 2.1 kb); EE5.7, EB0.8 (EcoRI-BamHI, 0.8 kb), O (BamHI-BamHI, 2.3 kb), and P2 (SalI-EcoRI, 1.8 kb); SS6.7, P2, P3 (EcoRI-EcoRI, 1.45 kb), and P4 (PstI-SalI, 2.2 kb); EE7.0, P1 (EcoRI-SalI, 3.4 kb), Q2 (SalI-BanIII, 2.3 kb), and Q1 (BanIII-EcoRI, 2.1 kb); HH6.0, Q2, Q1, and R (EcoRI-BamHI, 1.8 kb); EE4.5, R, W1 (BamHI-BamHI, 1.4 kb), and W2 (BamHI-EcoRI, 1.25 kb); EE5.0, ES0.47 (EcoRI-SalI, 0.47 kb), SpBx2.5 (SpeI-BstXI, 2.5 kb), and X6 (BstXI-EcoRI, 0.4 kb); EE3.2, X7 (EcoRI-EagI, 1.6 kb), X8 (EagI-HindIII, 0.9 kb), and X9 (HindIII-EcoRI, 0.7 kb); HH3.3, X9, Y0 (EcoRI-SalI, 1.9 kb), and SS0.6 (SalI-SalI, 0.6 kb); SE3.1, a1 (SalI-XbaI, 1.0 kb), a2 (XbaI-BanIII, 1.0 kb), and a3 (BanIII-EcoRI, 1.0 kb); ES3.9, b1 (EcoRI-BstXI, 1.2 kb), b2 (BstXI-SacII, 1.5 kb), and b3 (SacII-SalI, 1.2 kb).

Images were taken by exposing membranes to phosphorimaging plates (Fuji Photo Film) for 5 to 50 h and analyzed with a BAS2000 Bio Image Analyzer (Fuji Photo Film).

Northern blotting.

Total RNA was isolated from embryos or Kc cells with Trizol reagent (GIBCO) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Twenty micrograms of total RNA was run in a 0.8% agarose gel containing formaldehyde. After electrophoresis, RNA was blotted onto Duralon UV membranes (Stratagene) and mRNAs were detected by hybridization with probes labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using a Random Primer DNA labeling kit, version 2 (Takara Shuzo). Probes specific for the first exon of each dE2F transcript were 264- and 260-bp fragments prepared by PCR amplification of Drosophila total genomic DNA with the following primer pairs, respectively; 5′-TTGTTCAAAATTGTTCTGCAAC-3′ and 5′-GAAGCCTTGATGAACAATTTTC-3′ for Ohtani’s transcript (31) (dE2F-a) and 5′-GACTGCCTCTGCAAGTAAAAGA-3′ and 5′-TTGACTCAGTCTGTGTGTGTGC-3′ for Dynlacht’s transcript (9) (dE2F-b). The probe specific for DNApolα was a mixture of probes C and D, as used for N/A 2D gel analysis.

Image processing.

Images were processed with Photoshop (Adobe) and Canvas (Deneba) and printed with Pictrography 3000 (Fuji Photo Film).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data determined in this study have been deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank databases under accession no. AB011813.

RESULTS

Unspecified distribution of replication origins in syncytial embryos.

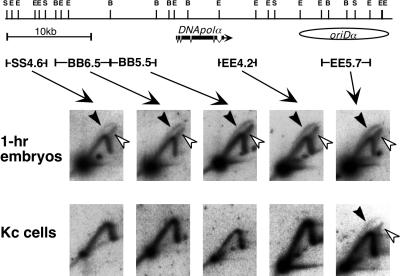

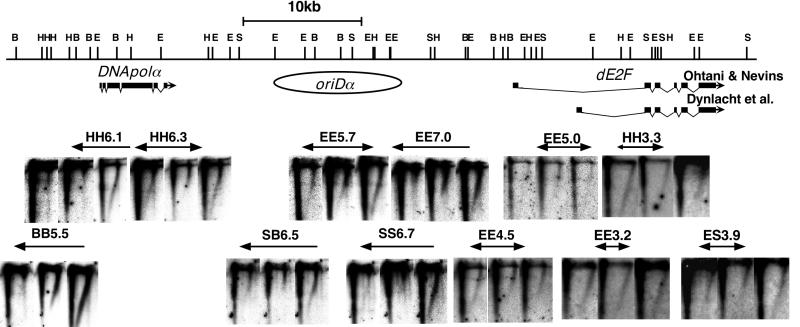

One of our previous studies showed that DNA replication initiates at numerous sites with little site specificity in the histone gene repeats and in a single-copy chromosomal region on chromosome II in 1-h embryos (36). In order to confirm that the origins are distributed broadly also in the DNApolα locus, N/N 2D gel analysis of the 40-kb region surrounding DNApolα was performed (Fig. 3). The N/N 2D gel method permits distinction between fragments containing internal origins (bubbles) and fragments passively replicated by forks moving through one end to the other (simple Y) by their different electrophoretic mobilities in the second-dimension electrophoresis (5). If replication forks enter a given fragment from both ends and meet within this fragment, the replication intermediates are detected as double Ys. In contrast to the results from Kc cells, for which no bubble arcs were detected in fragments other than EE5.7, bubble arcs were detected in all fragments in 1-h embryos. Double Y arcs were also observed in all fragments in the 1-h embryos, consistent with the presence of numerous initiation sites. Thus, we conclude that DNA replication initiates at numerous unspecified sites also in the DNApolα locus in the syncytium stage of embryos collected from 1 to 2 h after fertilization.

FIG. 3.

Distribution of replication origins tested by N/N 2D gel analysis in 1-h embryos and Kc cells. Five micrograms of total DNA from 1-h embryos was digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and subjected to N/N 2D gel analysis. Data for Kc cells are depicted from a previous report (38). First-dimension electrophoresis is from right to left, and second-dimension electrophoresis is from top to bottom. The locations of the fragments are shown in the above map. Bubble arcs are indicated by closed arrowheads, and double Y arcs are indicated by open arrowheads. Abbreviations for restriction enzymes are as for Fig. 2.

Specification of origin usage during embryogenesis.

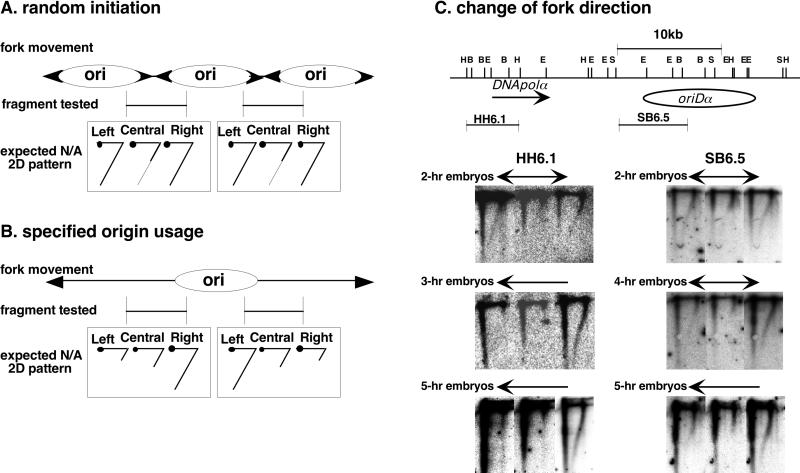

Next we studied when the initiation region and the noninitiation region of DNA replication were specified during embryogenesis. We approached this problem by attempting to determine at what stage of embryogenesis the direction of the replication forks changes in the fragments near oriDα, based on the data analyzed by the N/A 2D gel method. The rationale for this approach is illustrated in Fig. 4A and B. If multiple replication origins located both inside and outside of a given fragment contribute to replicate the fragment as in early embryos described above, replication forks traveling this fragment are a mixture of those entering the fragment from its left and right and those emanating from the inside origins. In this case, the lengths of the shortest nascent strands detected by the probes located in the right, center, or left portions of the fragment do not change unidirectionally (Fig. 4A). After origin specification, the directions of the replication fork movement become biased in the fragment located outside of the specified initiation region, and the lengths of the shortest nascent strands detected by short probes will become different depending on the distance between the probes and replication origins (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Change in direction of replication forks examined during embryogenesis. (A) Expected N/A 2D gel patterns when replication initiates at random sites. When multiple replication origins spaced closely contribute to replicating a given fragment, replication forks move in both directions in the fragment, and thus the length of the shortest nascent strands detected by probes located in the right, central, or left portion of the fragment does not change unidirectionally. (B) Expected N/A 2D gel patterns when replication initiates at a specified origin. When the initiation region is confined to a certain region, replication forks moving in a fragment located outside of the initiation region are unidirectional or predominantly unidirectional, and the length of the shortest nascent strands detected by short probes changes depending on their position in the fragment: the closer to the origin, the shorter the strand. (C) N/A 2D gel patterns for fragments HH6.1 and SB6.5 in embryos. DNA prepared from variously staged embryos was subjected to the N/A 2D gel analysis. First-dimension electrophoresis is from right to left, and second-dimension electrophoresis is from top to bottom. Blots were sequentially hybridized with the left, central, and right probes of the 6.1-kb HindIII fragment (HH6.1) or the 6.5-kb SalI-BamHI fragment (SB6.5), and their hybridization patterns are aligned in that order in each panel. The inferred direction of replication fork movement is shown above each panel. The bar with arrows at both ends indicates that replication forks move in both directions in the fragment, and bars with an arrow at one end mean that replication forks move predominantly, if not exclusively, in a single direction toward the end with the arrow. Abbreviations for restriction enzymes are as for Fig. 2.

Figure 4C shows the results for two typical fragments in which the direction of replication fork progression changes during embryogenesis. Fragment HH6.1 contains the coding region for DNApolα and represents the noninitiation region in Kc cells. Fragment SB6.5 contains the left half of the initiation region, oriDα (38).

In 2-h embryos, replication forks moving in both directions were detected both in HH6.1 and SB6.5 and in all other fragments tested. These results suggest that origin usage has not yet become specified in 2-h embryos, which mainly consist of blastoderms in cycle 14. In 3-h embryos, however, the replication forks in HH6.1 had become unidirectional. This means that replication origins active in the earlier embryos become repressed in 3-h embryos. In SB6.5, replication forks moving in both directions were still observed even in 4-h embryos but became predominantly unidirectional in 5-h embryos. The predominant direction of replication fork progression in SB6.5 in 5-h embryos was from right to left, consistent with the expectation that the region was mainly replicated by origins in oriDα or to its right.

These results suggest that replication origins in the coding region of DNApolα become repressed after cellularization of the blastoderm, which occurs from 2 to 3 h after fertilization, and that the range of the initiation region oriDα becomes confined by 5 h after fertilization.

N/A 2D gel analysis of initiation regions in 5-h embryos.

To determine if the initiation regions established in 5-h embryos are the same as those observed in cultured cells, replication patterns in 5-h embryos were further analyzed by N/A and N/N 2D gel methods. The N/A 2D gel patterns are shown in Fig. 5.

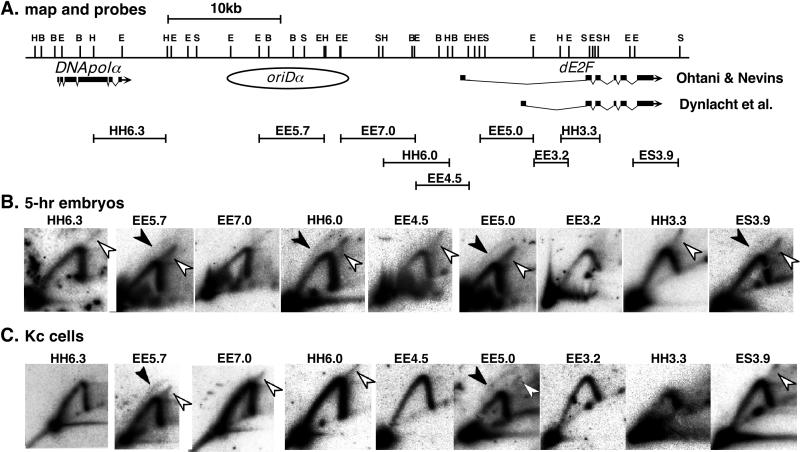

FIG. 5.

Directions of replication forks in 5-h embryos determined by N/A 2D gel analysis. DNA prepared from 5-h embryos was subjected to N/A 2D gel analysis for various restriction fragments from the DNApolα-dE2F locus. Physical and genetic maps of the region tested are shown at the top. Arrows attached to the bars showing the range and location of the restriction fragments tested indicate the directions of replication fork movement within each fragment inferred from the N/A 2D gel patterns. The meanings of the arrows are the same as for Fig. 4C. The data for HH6.1 and SB6.5 are from those for 5-h embryos in Fig. 4C. The pattern for HH5.0 (the 5-kb HindIII fragment overlapping EE7.0 and SS6.7) is not shown, but the direction of replication fork movement was the same as that for EE7.0 and SS6.7. First-dimension electrophoresis is from right to left, and second-dimension electrophoresis is from top to bottom. Blots were sequentially hybridized with the left, central, and right parts of the fragments tested. Abbreviations for restriction enzymes are as for Fig. 2.

The first finding which suggested a difference in the replication patterns between embryos and cultured cells was the replication forks moving in both directions that were detected in HH6.3 located between HH6.1 and SB6.5. As reported in an earlier study, replication forks emanating from replication origins in oriDα proceed unidirectionally through DNApolα in cultured Kc cells, and replication in HH6.3 is unidirectional (38). Because the direction of replication fork movement in 5-h embryos is predominantly from right to left in both HH6.1 and SB6.5 (Fig. 4C), the bidirectional replication fork movement in HH6.3 can be explained by assuming the presence of initiation sites within and/or around the HH6.3 region.

The major difference in the replication patterns between 5-h embryos and Kc cells was found in the downstream region to the right of oriDα. As described above, replication forks move predominantly from right to left in SB6.5 in 5-h embryos, supporting the observation that this fragment is mainly replicated by the replication origins located in its right-end portion and/or the external origins located on its right. In fact, replication forks moving in both directions were detected in EE5.7, which is located in the center of oriDα (Fig. 5). This result is consistent with the notion that EE5.7 is included in the broad initiation region corresponding to oriDα in 5-h embryos, as in Kc cells (38). However, the replication patterns in the region on the right of EE5.7 were different from those observed in cultured cells. In Kc cells, replication forks move bidirectionally from oriDα, and then replication fork movement in the fragments located on the right of EE5.7 is predominantly from left to right, opposite to the direction in SB6.5 (38). However, in 5-h embryos, the replication forks proceeded toward EE5.7 in fragments EE7.0, SS6.7, and HH5.0, which were located on the right of EE5.7 (Fig. 5). Taken together, these results suggest that replication origins in the oriDα region are actually active in 5-h embryos but that there are other initiation sites in the genomic region downstream of, although not far from, oriDα.

To search for the putative initiation sites located on the right of oriDα, the 27-kb genomic region adjacent to the oriDα locus was cloned and its nucleotide sequence was determined. The newly isolated region included the gene encoding the Drosophila homologue of transcription factor E2F (dE2F). Two kinds of cDNAs differing only in the 5′ nontranslated regions have been reported (9, 31). Comparison of the genomic sequence of the dE2F locus with those of the cDNAs revealed two genomic sequences corresponding to the diverged sequences of two dE2F cDNAs. Thus, there are at least two kinds of transcripts of dE2F that differ in the nontranslated first exon but share the other exons, as shown in the map in Fig. 5.

The N/A 2D gel patterns of fragments in the dE2F locus observed in 5-h embryos are also shown in Fig. 5. Replication forks moving in both directions were observed in most fragments except HH3.3. In HH3.3, the direction of replication fork movement was primarily from left to right. Thus, the replication patterns in the dE2F locus seem to be rather complex, and the results suggest that the putative initiation sites adjacent to oriDα are located in the region between EE7.0 and HH3.3. This region includes the promoter regions for both transcripts of dE2F. The finding that the direction of replication fork movement is bidirectional in ES3.9 suggests that still other replication origins are present in the 3′ portion or 3′ downstream region of dE2F.

N/N 2D gel analysis of initiation regions in 5-h embryos and Kc cells.

The above N/A 2D gel analysis suggested the existence of initiation sites in the following regions in 5-h embryos: the 3′ downstream region of DNApolα, the oriDα region, the 5′ upstream region of dE2F, and the 3′ downstream region of dE2F. To confirm the regions that definitely contain replication origins in 5-h embryos, N/N 2D gel analysis was performed and the results were compared with those observed in Kc cells (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Initiation regions detected by N/N 2D gel analysis. DNA prepared from 5-h embryos and Kc cells was subjected to N/N 2D gel analysis for various restriction fragments from the DNApolα-dE2F locus. (A) Physical and genetic maps of the region tested. The range and location of the restriction fragments tested are shown by bars. Abbreviations for restriction enzymes are as for Fig. 2. (B) N/N 2D gel patterns observed in 5-h embryos. (C) N/N 2D gel patterns observed in Kc cells. The data for HH6.3, EE5.7 and EE7.0 are from one of our previous reports (38). (B and C) First-dimension electrophoresis is from right to left, and second-dimension electrophoresis is from top to bottom. The probes were the restriction fragments themselves or their subfragments. Closed arrowheads represent bubble arcs, and open arrowheads represent double Y arcs.

As shown in Fig. 6, fragments EE5.7, HH6.0, EE5.0, and ES3.9 showed bubble arcs in 5-h embryos. Thus, the existence of replication origins in the oriDα region (EE5.7), the 5′ upstream regions of dE2F (HH6.0 and EE5.0), and the 3′ downstream region of dE2F(ES3.9) was confirmed. Replication bubbles, however, were not detected in HH6.3. Bubble arcs also were not detected in other fragments overlapping HH6.3 (data not shown). If replication origins are present in the HH6.3 region, as suggested from the N/A 2D pattern of HH6.3, the frequency of their firing may be too low or the replication bubbles formed may be too short lived to be detected as bubble arcs.

Among the fragments that showed bubble arcs in 5-h embryos, only EE5.7 and EE5.0 exhibited bubble arcs in Kc cells as well (Fig. 6). These results suggest that origin usage in 5-h embryos is in the intermediate state between earlier embryos and Kc cells. Interestingly, while the two fragments (HH6.0 and EE5.0) corresponding to the respective 5′ upstream regions for two transcripts of dE2F showed bubble arcs in 5-h embryos, bubble arcs were detected only in EE5.0 in Kc cells.

Double Y arcs were observed in most fragments from the dE2F locus in 5-h embryos. These results might account for the observation in the N/A 2D gel analysis (Fig. 5) of replication forks moving in both directions in most fragments. Bidirectional replication fork movement and the formation of double Y replication intermediates in the initiation regions might be due to a broad distribution of replication origins, as in oriDα (38). We were unable to discriminate between the following two possible explanations for the complex situations in the regions where replication bubbles were not detected. Replication origins belonging to different initiation regions may fire in different cells, resulting in a mixture of the direction of replication fork movement and termination at diverse sites. Alternatively, complex replication patterns may also be caused by the presence of minor initiation sites throughout the regions where bubble arcs were not detected by N/N 2D gel analysis.

Differential expression of the dE2F gene.

Recently it has been shown that among two kinds of transcripts of dE2F, the transcript corresponding to the cDNA reported by Dynlacht et al. (9) was expressed throughout embryogenesis and in other stages of development, while the transcript reported by Ohtani and Nevins (31) was expressed in a specific stage of embryos, highest in 4- to 8-h embryos (33). As for the initiation region of DNA replication, the upstream regions of both transcripts were active in 5-h embryos (HH6.0 and EE5.0) while only one (EE5.0) was active in Kc cells (Fig. 6). These observations led us to examine whether the two transcripts are expressed differently between 5-h embryos and Kc cells. By Northern blotting analysis with specific probes for each of the first exons, both transcripts (dE2F-a and -b) were detected in 5-h embryos but only one (dE2F-b), ubiquitously expressed throughout development, was detected in Kc cells (Fig. 7). Thus, there seems to be a spatial correlation between active initiation regions of DNA replication and active promoter regions for transcription of dE2F.

FIG. 7.

Detection of dE2F transcripts by Northern blotting. Total RNA prepared from 5-h embryos and Kc cells was subjected to Northern analysis of transcripts of dE2F. Blots of total RNA were sequentially hybridized to probes specific for the first exon of each transcript. The probe dE2F-a was specific to cDNA reported by Ohtani and Nevins (31), and the probe dE2F-b was specific to cDNA reported by Dynlacht et al. (9). As a reference, mRNA coding DNApolα (polα) was detected with the mixture of probes C and D, as shown in Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

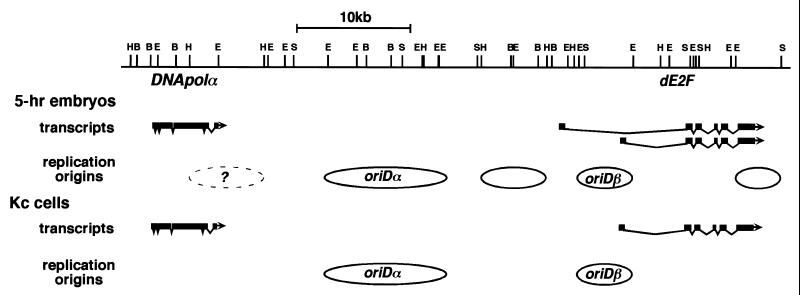

DNA replication initiated at unspecified chromosomal sites in preblastoderm embryos, but the initiation regions in the oriDα locus were specified by 5 h after fertilization during Drosophila embryogenesis. Replication origins in the coding region of DNApolα were already repressed in 3-h embryos after completion of cellularization of the blastoderms, but confinement of the range of oriDα was clear in 5-h embryos. A comparison of the replication patterns in the DNApolα-dE2F locus between 5-h embryos and Kc cells (Fig. 8) suggested that specification of origin usage in 5-h embryos was still in the intermediate state between the younger embryos and the more differentiated cells. We also noticed a spatial correlation between the active initiation regions of DNA replication and the active promoter regions for transcription in the upstream region of dE2F.

FIG. 8.

Comparison of initiation regions and transcripts in the DNApolα-dE2F locus between 5-h embryos and Kc cells. The initiation regions of DNA replication where replication bubbles were detected by N/N 2D gel analysis (Fig. 6) are shown as solid ovals. The potential initiation sites suggested by the N/A 2D pattern (Fig. 5) are shown as a dashed oval. The range of oriDα in Kc cells is shown according to previously reported data (38), while those of the other initiation regions are arbitrary. Transcripts for DNApolα and dE2F detected by Northern blotting analysis (Fig. 7) are shown by exon-intron structures.

As observed in Drosophila embryos, replication initiation occurs at unspecified sites in ribosomal DNA of Xenopus early embryos (23) but becomes confined to the intergenic spacers at the late blastula and early gastrula stage (22). What restricts the initiation region during embryogenesis? One apparent factor that changes during Drosophila embryogenesis is the concentration of nuclei in syncytial cytoplasm (10). In a Xenopus cell-free replication system, it was reported that the nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio affects both S-phase length and replicon size (40). The concentration of nuclei at which the S phase lengthens in vitro is similar to the concentration of nuclei in Xenopus embryos at the midblastula transition, and the changes in replicon size are very similar in vitro and in vivo. This indicates that a quantitative change in some factor(s) causes a preference in origin usage. Origin recognition complex (ORC) proteins and minichromosome maintenance (MCM) proteins are believed to play important roles in DNA replication and are the likeliest candidates for such limiting factors. In the Xenopus cell-free system, however, they are abundant and thus are not thought to be a limiting factor of origin usage (40). In Drosophila embryos, ORC and MCM proteins are maternally supplied, and the maternal supply is sufficient for embryonic mitoses because homozygous mutants of some of their genes survive until late larval or pupal stage (14, 24, 39). In wild-type embryos, the amounts of the transcript of the dpa gene encoding a homologue of the MCM4 protein were maximum in 6- to 9-h embryos and reduced remarkably in 9- to 12-h embryos (14). Thus, the MCM proteins (and also ORC proteins) may not be the limiting factor for specification of origin usage in Drosophila embryos either. It is possible, however, that factors to modify and regulate the activities of ORC and MCM proteins or factors to recruit them to the replication origins are limiting factors that specify replication origins.

In addition to the quantitative factors, there are factors whose qualitative change during embryogenesis influences origin usage. Chromatin structures change in various aspects during embryogenesis. For example, chromatin of the blastoderm stage of embryos (0 to 2 h) differs significantly from that of older embryos (6 to 8 h), and histone H1 is absent in the blastoderm chromatin (12). Lack of histone H1 contributes to the decrease in nucleosome spacing in chromatin reconstituted in vitro from cell extract prepared from preblastoderms of Drosophila embryos (3). Recently it was reported that the addition of histone H1 reduces the frequency of replication initiation in Xenopus egg extract, most likely by limiting the assembly of prereplication complexes on sperm chromatin, even when sufficient amounts of proteins necessary for formation of prereplication complexes, such as ORC and MCM, are present in extract (26).

A Drosophila homologue of the HMG 1 protein, HMG-D, is associated with condensed chromatin structures in the nuclear cleavage cycles of Drosophila embryos (29). It is thought that HMG-D, either by itself or in conjunction with other chromosomal proteins, induces a condensed state of chromatin that is distinct from and less compact than chromatin with histone H1. Histone H1 is absent in the chromatin in early embryos and is first detected in cycle 7, and its level dramatically increases after stage 7 (cycle 14) due to activation of zygotic transcription. Because HMG-D is present at a constant level at all stages of development, HMG-D/H1 ratios decrease as embryogenesis progresses and there is a temporal correlation between the switch in HMG-D/H1 ratios and the changes that occur during the midblastula transition. The data shown in Fig. 4 suggest that replication origins in the coding regions of DNApolα (fragment HH6.1) are active in 2-h embryos (mainly cycle 14) but become inactive in 3-h embryos. Thus, the stage at which the repression of origin activities is first detected corresponds to the stage just after a dramatic increase in the histone H1 level.

The nucleosome structure without histone H1 in earlier embryos itself may be sufficiently loose to permit access of the initiation factors to random sequences without a high specificity of origin selection. Further, the importance of the higher structure of chromatin in DNA replication has been demonstrated in a system with CHO nuclei reconstituted in Xenopus extract (25). The chromatin structure without histone H1 would cause a difference in the higher-order structure of chromatin, including chromosome condensation in mitosis, which may permit the selection of origins which are different from those of chromatin associated with histone H1. Thus, the linker histone may play an important role in specifying origin usage in early embryogenesis both in Drosophila and Xenopus.

Another factor which may affect the origin activity is the activation of transcription. In Drosophila embryos, the activation of zygotic transcription is first detectable during cycle 11 or 12 and reaches maximal activation during late cycle 14 (11). Replication is initiated outside of the transcription units after activation of zygotic transcription in the DNApolα and dE2F loci. Changes occurring at midblastula transition, like the change in chromatin structure discussed above, will affect both activation of transcription and origin usage, but transcription itself and/or factors controlling transcription may influence origin activity.

Though initiation and noninitiation regions become separated 5 h after fertilization, the initiation regions observed in 5-h embryos still appear to be less specified than those observed in Kc cells. The potential initiation regions in the DNApolα-dE2F locus observed in 5-h embryos and Kc cells are schematically presented in Fig. 8. In Kc cells, an initiation region (oriDβ) was newly identified about 20 kb away (a center-to-center distance between fragments EE5.7 and EE5.0) from the previously identified oriDα. In addition to these initiation regions, two initiation sites, one between oriDα and oriDβ and another around the 3′ portion of dE2F, were observed in 5-h embryos. The N/A 2D gel data suggested the presence of some initiation sites also around the 3′ portion of DNApolα. Thus, the replication origins in 5-h embryos consist of those in Kc cells plus some other regions, and the average center-to-center distance of the initiation regions in 5-h embryos is about 10 kb. The complex N/A and N/N gel patterns observed in 5-h embryos (Fig. 5 and 6) must result from such short spacing of the initiation regions and/or incomplete repression of origin activity in the regions where replication bubbles were not detected. These results suggest that the initiation regions in 5-h embryos are in the intermediate state of origin specification between preblastoderm embryos and cells in the later stages of development. During embryogenesis in Drosophila, most cells stop proliferation after the 16th cell cycle; later, in the larval stage, cells resume proliferation. Though the cell line Kc was originally established from embryonic cells (2), cells established as a cell line are thought to have chromatin structures corresponding to those of more differentiated cells. The possibility that usage of different initiation regions depending on cell type, e.g., mitotic domains (16), resulted in an apparent shortening of spacing between initiation regions cannot be excluded.

The results suggest that initiation of DNA replication and activation of transcription are correlated in the 5′ upstream region of dE2F in both embryos and Kc cells. It was recently demonstrated (33) that the two transcripts of dE2F have separate promoter regions and that their expression is differentially regulated. One transcript was ubiquitously detected at all stages of development and in cultured cells, while the other was detected only in embryos, maximally in 4- to 8-h embryos. In accordance with these expression patterns of dE2F, origin activities were observed in the 5′ upstream region of the ubiquitously expressed transcript in both 5-h embryos and Kc cells, but those in the 5′ upstream region of the transcript expressed only in embryos were detected only in 5-h embryos. The influence of transcription and/or transcription factors on replication in viral systems (reviewed in reference 7), bacterial systems (1), ARS1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (27), and an in vitro transcription-replication model system (30) has been extensively discussed. Confocal microscopic observation indicated that replication sites and transcription sites colocalize in nuclei (18). A well-known example of the effect of transcription on DNA replication in higher eukaryotes is that activation of transcription of tissue-specific genes frequently accompanies activation of nearby replication origins. For example, replication of the murine immunoglobulin H (IgH) locus is related to the transcriptional activity of the locus; replication origins that are inactive in non-B cells are active in B cells and pre-B cells in which the IgH genes are expressed (6). Similarly, the activity of the replication origin at the promoter region of the β-globin gene seems to be correlated with the transcriptional activity of the β-globin gene (13, 19). The dE2F gene, however, is expressed in any proliferating cell because the E2F protein is an important transcriptional regulator necessary for expression of many proliferation-related genes. It would be the first example suggesting a correlation between active promoter regions and active replication origins in a gene transcribed from promoters which are different depending on the cell type, although the relationship between the replication origins and promoters must be clarified at higher resolution.

In contrast to the replication origins observed upstream of dE2F, origin activity of oriDα does not seem to be correlated with transcriptional activity. Our preliminary Northern analysis (data not shown) suggested the presence of mRNAs detectable by probes in the adjacent regions of oriDα but not by a probe encompassing its 10-kb initiation region. These mRNAs were detected in early embryos until 2 h, but neither in later embryos nor in Kc cells. These mRNAs may correspond to expressed sequence tag (EST) sequences recently registered in the databases (GenBank accession no. LD33721, etc.). Because these EST sequences have a part of the second exon of the known two transcripts of dE2F, they may be the third transcript of dE2F. Their 5′ portion, corresponding to the first exon of the known transcripts, is composed of two exons, and oriDα is located within the 15-kb intron between these exons. Even if the mRNAs described above were the transcript corresponding to these EST clones, this transcript was expressed neither in Kc cells nor in later embryos, where oriDα was active. Therefore, the origin activity of oriDα seems to be independent of activation of this transcript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research on priority areas from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asai T, Takanami M, Imai M. The AT richness and gid transcription determine the left border of the replication origin of the E. coli chromosome. EMBO J. 1990;9:4065–4072. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashburner M. Drosophila: a laboratory handbook. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker P B, Wu C. Cell-free system for assembly of transcriptionally repressed chromatin from Drosophila embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2241–2249. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenthal A B, Kriegstein H J, Hogness D S. The units of DNA replication in Drosophila melanogaster chromosomes. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1974;38:205–223. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1974.038.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewer B J, Fangman W L. The localization of replication origins on ARS plasmids in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1987;51:463–471. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown E H, Iqbal M A, Stuart S, Hatton K S, Valinsky J, Schildkraut C L. Rate of replication of the murine immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus: evidence that the region is part of a single replicon. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:450–457. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DePamphilis M L. Eukaryotic DNA replication: anatomy of an origin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:29–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DePamphilis M L. Origins of DNA replication. In: DePamphilis M L, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Vol. 31. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 45–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dynlacht B D, Brook A, Dembski M, Yenush L, Dyson N. DNA-binding and trans-activation properties of Drosophila E2F and DP proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6359–6363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edgar B A, Kiehle C P, Schubiger G. Cell cycle control by the nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio in early Drosophila development. Cell. 1986;44:365–372. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90771-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edgar B A, Schubiger G. Parameters controlling transcriptional activation during early Drosophila development. Cell. 1986;44:871–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elgin S C R, Hood L E. Chromosomal proteins of Drosophila embryos. Biochemistry. 1973;12:4984–4991. doi: 10.1021/bi00748a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epner E, Forrester W C, Groudine M. Asynchronous DNA replication within the human beta-globin gene locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8081–8085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feger G, Vaessin H, Su T T, Wolff E, Jan L Y, Jan Y N. dpa, a member of the MCM family, is required for mitotic DNA replication but not endoreplication in Drosophila. EMBO J. 1995;14:5387–5398. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.FlyBase: a database of the Drosophila genome. [Online.] Genetics Society of America; 1997. http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu/ [1 July 1998, last date accessed.] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foe V E. Mitotic domains reveal early commitment of cells in Drosophila embryos. Development. 1989;107:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foe V E, Alberts B M. Studies of nuclear and cytoplasmic behaviour during the five mitotic cycles that precede gastrulation in Drosophila embryogenesis. J Cell Sci. 1983;61:31–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.61.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassan A B, Errington R J, White N S, Jackson D A, Cook P R. Replication and transcription sites are colocalized in human cells. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:425–434. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatton K S, Dhar V, Brown E H, Iqbal M A, Stuart S, Didamo V T, Schildkraut C L. Replication program of active and inactive multigene families in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2149–2158. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.5.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirose F, Yamaguchi M, Nishida Y, Masutani M, Miyazawa H, Hanaoka F, Matsukage A. Structure and expression during development of Drosophila melanogaster gene for DNA polymerase α. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4991–4998. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.18.4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huberman J A, Spotila L D, Nawotka K A, El-Assouli S M, Davis L R. The in vivo replication origin of the yeast 2μm plasmid. Cell. 1987;51:473–481. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyrien O, Maric C, Méchali M. Transition in specification of embryonic metazoan DNA replication origins. Science. 1995;270:994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyrien O, Méchali M. Chromosomal replication initiates and terminates at random sequences but at regular intervals in the ribosomal DNA of Xenopus early embryos. EMBO J. 1993;12:4511–4520. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis G, Kelley R, Spradling A, Tower J. The k-43 gene, required for chorion gene amplification and diploid cell chromosome replication, encodes the Drosophila homolog of yeast origin recognition complex subunit 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3888–3892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawlis S J, Keezer S M, Wu J R, Gilbert D M. Chromosome architecture can dictate site-specific initiation of DNA replication in Xenopus egg extracts. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1207–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Z H, Sittman D B, Romanowski P, Leno G H. Histone H1 reduces the frequency of initiation in Xenopus egg extract by limiting the assembly of prereplication complexes on sperm chromatin. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1163–1176. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.5.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marahrens Y, Stillman B. A yeast chromosomal origin of DNA replication defined by multiple functional elements. Science. 1992;255:817–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1536007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melov S, Vaughan H, Cotterill S. Molecular characterisation of the gene for the 180 kDa subunit of the DNA polymerase-primase of Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Sci. 1992;102:847–856. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.4.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ner S S, Travers A A. HMG-D, the Drosophila melanogaster homologue of HMG 1 protein, is associated with early embryonic chromatin in the absence of histone H1. EMBO J. 1994;13:1817–1822. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06450.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohba R, Matsumoto K, Ishimi Y. Induction of DNA replication by transcription in the region upstream of the human c-myc gene in a model replication system. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5754–5763. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohtani K, Nevins J R. Functional properties of a Drosophila homolog of the E2F1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1603–1612. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orr-Weaver T L. Developmental modification of the Drosophila cell cycle. Trends Genet. 1994;10:321–327. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sawado T, Hirose F, Takahashi Y, Sasaki T, Shinomiya T, Sakaguchi K, Matsukage A, Yamaguchi M. The DNA replication-related element (DRE)/DRE-binding factor system is a transcriptional regulator of the Drosophila E2F gene. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26042–26051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.26042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seum C, Spierer A, Pauli D, Szidonya J, Reuter G, Spierer P. Position-effect variegation in Drosophila depends on dose of the gene encoding the E2F transcriptional activator and cell cycle regulator. Development. 1996;122:1949–1956. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.6.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shinomiya, T. Unpublished data.

- 36.Shinomiya T, Ina S. Analysis of chromosomal replicons in early embryos of Drosophila melanogaster by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3935–3941. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shinomiya T, Ina S. DNA replication of histone gene repeats in Drosophila melanogaster tissue culture cells: multiple initiation sites and replication pause sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4098–4106. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shinomiya T, Ina S. Mapping an initiation region of DNA replication at a single-copy chromosomal locus in Drosophila melanogaster cells by two-dimensional gel methods and PCR-mediated nascent-strand analysis: multiple replication origins in a broad zone. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7394–7403. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Treisman J E, Follette P J, O’Farrell P H, Rubin G M. Cell proliferation and DNA replication defects in a Drosophila MCM2 mutant. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1709–1715. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter J, Newport J W. Regulation of replicon size in Xenopus egg extracts. Science. 1997;275:993–995. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]