Abstract

Background

Contrast‐induced acute kidney injury (CI‐AKI) is a serious complication after percutaneous coronary intervention. The mainstay of CI‐AKI prevention is represented by intravenous hydration. Tailoring infusion rate to patient volume status has emerged as advantageous over fixed infusion‐rate hydration strategies.

Methods and Results

A systematic review and network meta‐analysis with a frequentist approach were conducted. A total of 8 randomized controlled trials comprising 2312 patients comparing fixed versus tailored hydration strategies to prevent CI‐AKI after percutaneous coronary intervention were included in the final analysis. Tailored hydration strategies included urine flow rate–guided, central venous pressure–guided, left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure–guided, and bioimpedance vector analysis–guided hydration. Primary endpoint was CI‐AKI incidence. Safety endpoint was incidence of pulmonary edema. Urine flow rate–guided and central venous pressure–guided hydration were associated with a lower incidence of CI‐AKI compared with fixed‐rate hydration (odds ratio [OR], 0.32 [95% CI, 0.19–0.54] and OR, 0.45 [95% CI, 0.21–0.97]). No significant difference in pulmonary edema incidence was observed between the different hydration strategies. P score analysis showed that urine flow rate–guided hydration is advantageous in terms of both CI‐AKI prevention and pulmonary edema incidence when compared with other approaches.

Conclusions

Currently available hydration strategies tailored on patients' volume status appear to offer an advantage over guideline‐supported fixed‐rate hydration for CI‐AKI prevention after percutaneous coronary intervention. Current evidence suggests that urine flow rate–guided hydration as the most convenient strategy in terms of effectiveness and safety.

Keywords: contrast‐induced acute kidney injury, coronary angiography, hydration, percutaneous coronary intervention

Subject Categories: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Meta Analysis, Coronary Artery Disease

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BIVA

bioimpedance vector analysis

- CI‐AKI

contrast‐induced acute kidney injury

- CVP

central venous pressure

- LVEDP

left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure

- UFR

urine flow rate

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Tailoring intravenous hydration on objective measurements of patient volume status appears to be more effective than the currently recommended one‐size‐fits‐all hydration for the prevention of contrast‐induced acute kidney injury in the setting of percutaneous coronary intervention.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

If feasible, tailored hydration strategies may be considered over standard fixed‐rate hydration for the prevention of contrast‐induced acute kidney injury.

Contrast‐induced acute kidney injury (CI‐AKI) complicates ≈7% of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs).1 The development of CI‐AKI is associated with a higher risk of dialysis, myocardial infarction, major bleeding, and death both during the hospital stay1 and up to 1 year after discharge.2 Hydration before, during, and after the procedure and limiting contrast volume administration are the most effective preventive measures against CI‐AKI.3 Traditionally, hydration regimens with fixed intravenous infusion rates of normal saline have been employed.3 However, recent evidence suggests that tailoring the infusion rate to patient volume status, that is, by adjusting infusion rate according to central venous pressure (CVP), left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure (LVEDP), bioimpedance vector analysis (BIVA), or urine flow rate (UFR), can lead to lower rates of CI‐AKI compared with fixed hydration strategies.3 Each of such tailored strategies has been directly compared with a fixed hydration regimen, but comparisons across different tailored hydration strategies are mostly lacking. We therefore performed a systematic review and network meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials of tailored versus fixed hydration strategies for CI‐AKI prevention following coronary angiography and intervention.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article.

Literature Search

A total of 3 authors (F.M., L.B., and L.A.) independently searched MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Database of Controlled Trial from inception until September 9, 2020, using a combination of key words including “contrast‐induced acute kidney injury,” “contrast‐induced nephropathy,” “hydration,” and “percutaneous coronary intervention.” No language restrictions were applied. Full queries are available in Table S1. Backward snowballing, that is, a review of references from the identified articles and relevant reviews, was also performed.4 This network meta‐analysis was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension statement for network meta‐analysis.5 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses diagram for the study selection process is shown in Figure S1, and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses checklist for the present network meta‐analysis is available in Data S1.

Data Selection

All published randomized controlled trials comparing different hydration strategies for the prevention of CI‐AKI after PCI and including at least 1 tailored hydration arm (defined as adjusting hydration volume or rate to the patient volume status) were considered eligible for inclusion in the present network meta‐analysis.

Outcome Measures

The prespecified efficacy end point was the occurrence of study‐defined CI‐AKI. The prespecified safety end point was the occurrence of study‐defined pulmonary edema.

Data Identification and Extraction

A total of 2 investigators (F.M., L.B.) independently extracted data on patient characteristics, treatment strategies, and outcomes using a standardized data extraction form. Conflicts regarding inclusion and data extraction were discussed and resolved with a third senior investigator (L.A.). Data collection included authors, year of publication, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size, baseline clinical features of patients, hydration strategies, total hydration volume per treatment arm, and end point definitions. Data on complications were also collected when available.

Risk of Bias and Certainty Assessment

A total of 2 independent reviewers (F.M., L.A.) assessed the risk of bias (low, intermediate, or high) of the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration Tool for Randomized Trials 2.0 for each outcome.6 Publication bias and small study effect was assessed with outcome‐specific comparison‐adjusted funnel plots and subsequent regression analysis as previously described.7 We graded the certainty of direct and network evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation criteria for network meta‐analysis.8, 9

Statistical Analysis

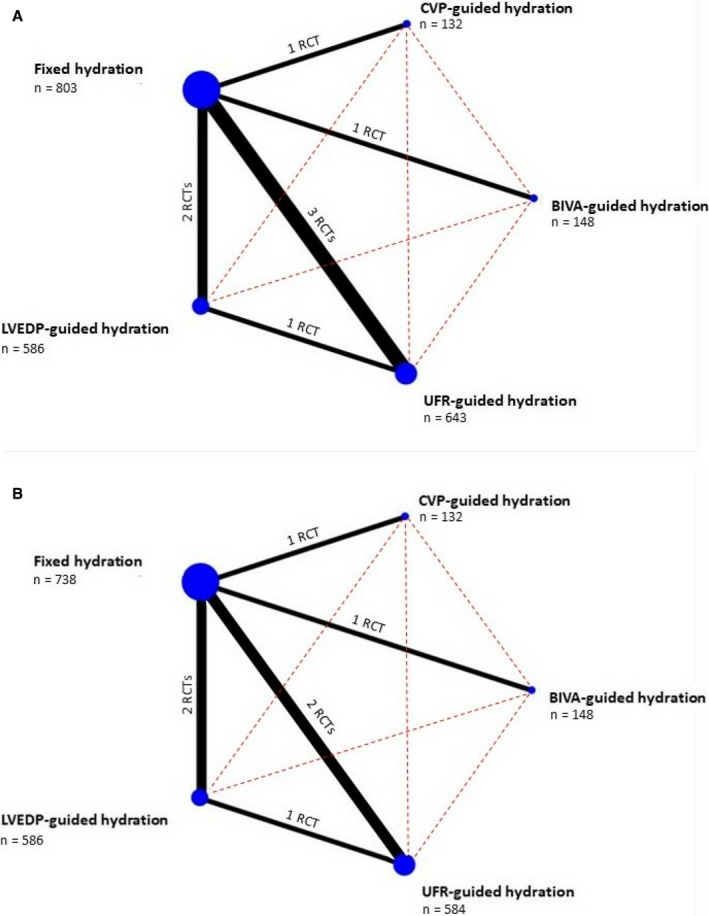

Cumulative event rates for efficacy and safety end points were obtained and reported. Network meta‐analysis was conducted based on a frequentist approach to compare treatments without direct pairwise comparisons.10 We used a random effect model to allow for apparent heterogeneity between studies in treatment comparison effects. The network map for the analysis was built with nodes, representing interventions, of a size weighted by the overall number of subjects receiving the intervention, connected by edges having a thickness proportional to the number of studies available for that specific pairwise comparison (Figure 1).11 A complete network geometry description was provided using specific network analysis statistics.12 Treatment ranking was performed by means of P scores.13 All outcomes of interest were binary and the treatment effects were reported in the odds ratio (OR) scale with 95% CI. The validity of the consistency assumption between direct and indirect sources of evidence was evaluated locally using the node‐splitting approach,14, 15 involving only 3 treatments (ie, fixed‐rate hydration, LVEDP‐guided hydration, and UFR‐guided hydration) where both the direct and indirect evidence were available. Meta‐regression of the occurrence of CI‐AKI and of pulmonary edema on mean total hydration volume per treatment arm was performed as previously described.16, 17 A network meta‐analysis using a frequentist approach was subsequently performed to evaluate the differences in terms of mean hydration volume between treatments. Statistical analyses were conducted with STATA version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) using the package “mvmeta,” R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using packages “meta” and “netmeta,” and Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis version 3 (Biostat, Engelwood, NJ).

Figure 1. Network maps of study treatments: (A) contrast‐induced acute kidney injury and (B) pulmonary edema.

Nodes represent each treatment; node size is proportional to the number receiving the corresponding treatment, which is indicated below treatment name. Solid edges represent direct comparisons available in the literature. The thickness of each edge is proportional to the number of available studies, which is indicated near the edge itself. Red‐dashed edges represent indirect comparisons. BIVA indicates bioimpedance vectorial analysis; CVP, central venous pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure; RCT, randomized controlled trial; and UFR, urine flow rate.

Ethical Consideration

Considering the meta‐analytic approach of the present study, which employed only published data in aggregated form, the requirement for ethics committee evaluation and institutional review board approval was not deemed necessary.

RESULTS

Data Selection

Literature search identified 783 studies. Among these, 772 were excluded during screening based on title and abstract. Of the 11 remaining studies, 3 were excluded at a second verification phase. Finally, 8 studies, for a total of 2312 patients, were included in the present network meta‐analysis.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Details of the studies are provided in Tables S2 and S3. A total of 3 studies compared UFR‐guided hydration with fixed hydration,18, 19, 21 2 studies compared LVEDP‐guided hydration with fixed hydration,20, 24 and 1 study was available for BIVA‐guided hydration versus fixed hydration,23 CVP‐guided hydration versus fixed hydration,22 and LVEDP‐guided hydration versus UFR‐guided hydration, respectively.25 One study comparing UFR‐guided and fixed hydration did not report on in‐hospital pulmonary edema21 and was therefore excluded from the safety end point analysis. The distribution of baseline characteristics by treatment was generally balanced, except for Maioli et al,23 who mainly included subjects at lower risk of CI‐AKI (ie, very low proportion of baseline chronic kidney disease) and excluded urgent or emergent cases. Information on concomitant use of N‐acetylcysteine inconsistently reported across the included studies and therefore was not reported in the present work.

Mixed Meta‐Analysis for the Primary Outcomes

The network map involved 5 treatments. (Figure 1A shows the map for CI‐AKI, whereas Figure 1B the map for pulmonary edema.) The number of studies for each direct comparison ranged from 1 to 3 in the case of CI‐AKI and from 1 to 2 for pulmonary edema. Fixed‐rate hydration was used as common comparator for both outcomes. Figure 2A presents the league tables for CI‐AKI and pulmonary edema. Network meta‐analysis showed that UFR‐guided (OR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.19–0.54) and CVP‐guided (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.21–0.97) hydration strategies were more efficacious than fixed hydration in preventing CI‐AKI.

Figure 2. League of tables for CI‐AKI (A) and pulmonary edema (B).

Each cell contains the odds ratio and 95% CI for the comparison of treatment reported in the column vs treatment reported in the row. Gray cells contain treatment name (C and D), P score, and ranking analysis. BIVA indicates bioimpedance vectorial analysis; CI‐AKI, contrast‐induced acute kidney injury; CVP, central venous pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure; and UFR, urine flow rate.

In terms of safety profile, the overall occurrence of pulmonary edema was low (incidence ranging from 0%23, 24 to 8.8%19). Network meta‐analyses showed no differences across all possible comparisons. According to P scores, UFR‐guided hydration ranked first for the prevention of CI‐AKI and second to fixed hydration in terms of risk of pulmonary edema. Figure 2 shows P scores with respect to CI‐AKI (Figure 2B) and pulmonary edema (Figure 2C).

Rates of Complications for Specific Hydration Strategies

To establish UFR‐guided and CVP‐guided hydration, the following additional invasive procedures are required: urinary catheter and a central venous line placement, respectively. Because these procedures inherently carry additional risks, such excess risk should be taken into account to inform appropriate decision making. Failure to place a central venous line was reported in 4/269 patients in the study by Qian and colleagues.22 No major complications related to central vein catheterization were reported. The total number of complications reported for Foley catheter insertion was 8/648, for a pooled event rate of 0.8% (95% CI, 0.0–1.7%).18, 19, 21, 25 In detail, 5 patients complained of pain or discomfort during micturition and 1 patient suffered hematuria, and in 2 cases a failure to place the catheter was reported. No major complication was reported. On top of the aforementioned complications, overall, 7 patients withdrew informed consent to participate in the studies because of concerns connected to urinary catheter positioning, for a pooled event rate of 0.6% (95% CI, 0.0–1.4%). The administration of furosemide during UFR‐guided hydration raises the concern for the potential development of electrolyte imbalances. A total of 3 studies comparing UFR‐guided hydration to a hydration strategy not requiring loop diuretic administration reported on the development of hypokalemia.18, 19, 25 Hypokalemia occurred in 37/570 patients in the UFR‐guided hydration group and in 20/568 controls, for a pooled OR of 1.62 (95% CI, 0.53–5.01; P=0.40). No cases of severe hypokalemia or arrhythmias were reported. A total of 2 studies reported on the development of hypernatremia.18, 25 Hypernatremia occurred in 4/483 patients undergoing UFR‐guided hydration and in 4/483 controls, for a pooled OR of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.50–4.03; P=1.00). A single study reported an incidence of hypomagnesemia of 16/132 patients in the UFR‐guided hydration group, whereas no cases were described among controls.18 All patients with hypomagnesemia were asymptomatic, and no intervention was required.

Sensitivity Analysis

Although trial design was somewhat homogeneous across most included studies, the work by Maioli et al,23 who compared BIVA‐guided versus a fixed hydration strategy, differed significantly. Specifically, patient volume status was evaluated before randomization, and only subjects with low total body water (as assessed noninvasively with BIVA) were considered eligible to take part in the study and subsequently randomly assigned to receive a standard or a high‐volume hydration regimen. Consequently, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding this study. Effect estimates and surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) values did not substantially change compared with the primary analysis: UFR‐guided and CVP‐guided hydration were still more efficacious in CI‐AKI prevention than fixed hydration (OR, 0.32 [95% CI, 0.19–0.54] and OR, 0.45 [95% CI, 0.21–0.97], respectively). Similarly, no differences were found across any comparison in terms of pulmonary edema. Sensitivity analyses league tables are shown in Table S4.

Risk of Bias and Certainty of Evidence

Bias analysis is presented in Figures S2 and S3. We judged 1 study23 to have a high risk of bias arising from the randomization process and selection of reported results. Of the trials, 418, 19, 21, 24 had some concerns about the randomization process and deviation from the intended treatment, outcome measurement, and selective reporting of outcomes. Overall, a low risk of bias was detected. When we evaluated the consistency assumption, we found evidence of inconsistency for the comparison of 3 treatments (namely, fixed‐rate hydration, UFR‐guided hydration, and LVEDP‐guided hydration) in both CI‐AKI and pulmonary edema (Table S5 and Figure S4). CVP‐guided and BIVA‐guided hydration were excluded in the assessment of inconsistency because of the lack of direct evidence. Comparison‐adjusted funnel plot analysis was consistent with a low risk of publication bias for both CI‐AKI and pulmonary edema (Figure S5). The certainty of evidence of network estimates for the outcomes of interest are presented in Figures 3 and 4, which report certainty of evidence of treatment effect estimates according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation criteria. Certainty was moderate or low/very low for most comparisons, mainly because of publication bias, risk of bias, indirectness, imprecision, inconsistency, and the possibility of intransitivity.

Figure 3. Summary of findings of the network meta‐analysis: CI‐AKI (efficacy outcome).

BIVA indicates bioimpedance vector analysis; CI‐AKI, contrast‐induced acute kidney injury; CVP, central venous pressure; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; LVEDP, left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure; NNT, number needed to treat; OR, odds ratio; RCT, randomized controlled trial; and UFR, urine flow‐rate.

Figure 4. Summary of findings of the network meta‐analysis: Pulmonary Edema (safety outcome).

BIVA indicates bioimpedance vector analysis; CI‐AKI, contrast‐induced acute kidney injury; CVP, central venous pressure; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; LVEDP, left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure; NNT, number needed to treat; OR, odds ratio; RCT, randomized controlled trial; and UFR, urine flow‐rate.

Hydration Volume and Study Outcomes

Five studies, for a total of 1610 patients, reported mean hydration volume per treatment arm and were subsequently included in this subanalysis.19, 20, 21, 22, 25 A total of 2 studies compared UFR‐guided hydration and fixed hydration,19, 21 1 study compared CVP‐guided hydration and fixed hydration,22 1 study compared LVEDP‐guided hydration with fixed hydration,20 and 1 study compared LVEDP‐guided hydration with UFR‐guided hydration.25 Post hoc meta‐regression shows evidence of an association between total hydration volume and treatment effect for the occurrence of CI‐AKI, with larger volumes being associated with lower rates of CI‐AKI, albeit with a small effect size (coefficient=−0.0005; 95% CI, −0.0009 to −0.0002; P=0.001; R 2=0.56; Figure 5A). On the other hand, no significant influence of hydration volume on pulmonary edema occurrence could be detected (coefficient=0.0001; 95% CI, −0.0007 to 0.0009; P=0.720; R 2<0.0001; Figure 5B). The network meta‐analysis showed that UFR‐guided hydration and LVEDP‐guided hydration provided the highest infused volumes when compared with fixed hydration (LVEDP‐guided hydration versus fixed hydration mean difference 1313 mL [95% CI, 1797–2284 mL] and UFR‐guided hydration versus fixed hydration mean difference 2606 mL [95% CI, 1797–3415 mL]), with UFR‐guided hydration providing the highest overall mean hydration volumes (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Hydration volume meta‐analysis.

A, The bubble plot for the meta‐regression of the logit event rate for CI‐AKI over mean hydration volume for each treatment arm of the studies included (efficacy outcome). B, The bubble plot for the meta‐regression of the logit event rate of pulmonary edema (safety outcome) over mean hydration volume. Bubbles represent each treatment arm, and bubble size is proportional to relative weight in the analysis. C, The league table for hydration volume differences. Each cell contains the effect size estimate for mean difference and 95% CI in hydration volume between the treatment reported in the column vs treatment reported in the row. All values are expressed in mL. A positive value means that mean hydration provided by the treatment indicated in the column is larger than the mean hydration provided by the treatment indicated in the row. Gray cells contain treatment name. CI‐AKI indicates contrast‐induced acute kidney injury; CVP, central venous pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure; and UFR, urine flow rate.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of the present systematic review and network meta‐analysis are the following:

UFR‐guided hydration is superior to guideline‐supported fixed‐rate hydration with respect to CI‐AKI prevention with a moderate certainty of evidence.

UFR‐guided hydration outperformed all other hydration strategies in terms of both CI‐AKI prevention and risk of pulmonary edema.

Higher total hydration volumes were associated with lower rates of CI‐AKI, whereas no impact of total hydration volume on pulmonary edema was detected. UFR‐guided hydration was found to provide the highest total hydration volumes across different hydration strategies.

The incidence of CI‐AKI following PCI greatly varies across published studies, and as such its incidence ranges between 3.3% and 14.5%.26, 27 Although in most cases CI‐AKI is a self‐limited event, with renal function returning to baseline within 3 weeks,28 it has not uncommonly been associated with severe adverse outcomes, irreversible kidney injury, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, or death as well as increased hospital stay and costs.29 The pathophysiology of CI‐AKI after PCI is complex. On one hand, contrast media alters kidney hemodynamics by inducing vasoconstriction and subsequent hypoperfusion. On the other hand, contrast media has a direct toxic effect on tubular cells and promotes the release of reactive oxygen species within the nephron.3 Moreover, other procedural‐related factors may contribute to the development of CI‐AKI, such as embolization of atheromatous debris into the renal arteries induced by catheter manipulation and renal hypoperfusion secondary to periprocedural hypotension.3 Because no effective treatment exists once CI‐AKI has established, prevention is critical. Hydration before, during, and after the procedure is the cornerstone of CI‐AKI prevention.30 Current guidelines support a strategy of fixed‐rate isotonic saline infusion to reduce the incidence of CI‐AKI.31 Hydration guarantees adequate intravascular volume (hence renal perfusion) and may reduce kidney exposure to contrast media by diluting contrast and favoring its rapid excretion.3, 32 Prophylactic intravenous hydration carries risks, the most severe of which is pulmonary edema secondary to volume overload (reported in up to 5.5% of cases), raising questions on the risk‐to‐benefit balance of hydration.33 In our analysis, we observed an impact of total hydration volume on CI‐AKI occurrence, with higher infused volumes being associated with lower CI‐AKI rates. Of note, we did not detect an association between pulmonary edema and total volume infused. Indeed, tailoring hydration to patient volume status can optimize volume expansion while still identifying patients at risk for volume overload. Larger volumes are infused selectively in patients with lower volume status. Conversely, aggressive infusion therapy is selectively avoided in those patients with higher preloads and left ventricular filling pressures who are at higher risk of pulmonary edema. Indeed, it should be noted that in the face of higher mean total infused volumes, tailored hydration strategies have higher crude measures of dispersion, reflecting the wide range of volumes infused.

Our analyses confirmed the advantage of all tailored strategies compared with fixed hydration albeit in some cases with large confidence (BIVA‐guided and LVEDP‐guided regimens) intervals marginally crossing the neutrality line. This was achieved in the face of similar rates of pulmonary edema. The low number of studies available on this topic, as well as differences in terms of study populations, could have decreased the power of the present analysis to detect a significant effect. It should also be noted that some minor heterogeneity in the definition of CI‐AKI adopted by different studies could have influenced our analysis.

A large reduction in term of CI‐AKI was, however, detected for both UFR‐guided and CVP‐guided hydration strategies. Multiple measurements of the patient volume/hemodynamic conditions and subsequent dynamic adjustment of hydration inherent to these approaches (based on replenishment of urine output and optimization of CVP, respectively) may ensure an optimal venous filling. Venous congestion (as reflected by a high CVP) is a strong predictor of AKI, whereas low CVP is generally associated with volume depletion and kidney hypoperfusion.32, 34, 35 Classical physiology experiments have demonstrated that raising renal vein pressure fosters renal sodium retention and reduces glomerular filtration rate, initiating a vicious cycle that eventually leads to volume overload and worsening of renal function.36, 37 This underlines how overzealous volume replacement may actually increase the incidence of CI‐AKI before causing overt manifestations such as pulmonary edema. On the other hand, BIVA‐guided and LVEDP‐guided hydration regimens feature an initial single measurement of patient body water or hemodynamic conditions, respectively, which may not allow for the fine‐tuning of hydration and dynamic volume optimization during and after the procedure, thus failing to take advantage of the full potential of a tailored hydration approach.

The use of furosemide in UFR‐guided hydration represents 1 of the major differences that sets this approach apart from the others. Inhibition of active ionic transport in the loop of Henle by loop diuretics was shown to reduce kidney energy expenditure, which could exert a protective cellular effect.38 The renoprotective effect of furosemide could be undermined by volume depletion induced by forced diuresis, reinforcing the fundamental role of urine output replenishment provided in UFR‐guided hydration.39

Despite the advantage in terms of efficacy and safety, some factors preventing the wider adoption of tailored hydration strategies have to be acknowledged. UFR‐guided and BIVA‐guided hydration require dedicated equipment, increasing procedural costs. UFR‐guided hydration requires placement of urinary catheter, which could carry risks related to local traumatic or infectious complications and may negatively impact patient satisfaction and perception of received care quality. CVP‐guided hydration requires placement of a central venous line, which has classically been associated with hematoma, arterial puncture, and pneumothorax (up to 13% in some series)40 as well as catheter‐related bloodstream infections.41 Furosemide administration for UFR‐guided hydration can induce electrolyte disturbances. UFR‐guided hydration requires time to achieve an adequate urine flow (up to 55 minutes in 1 study25), which could adversely impact the workflow of a busy modern catheterization laboratory and makes it unsuitable for emergency situations. Table S6 summarizes the limitations of each strategy. These limitations and considerations notwithstanding, our data indicate that the UFR‐guided approach, followed by the CVP‐guided regimen, are the most effective strategies to provide tailored hydration and decrease the risk of CI‐AKI in patients undergoing coronary angiography and intervention. A direct randomized comparison of these 2 strategies is eagerly awaited.

Limitations

Our study also presents several limitations. First, the quality of our analyses is limited by the inherent limitations of the individual included randomized controlled trials, which were overall small studies including a relatively exiguous number of patients. Second, individual patient data were not available, precluding sophisticated statistical adjustments. Third, although we showed full assessment of the risk of bias of all included trials (Figures S2 and S3), some studies did not report adequate information about allocation sequence concealment and blinding and provided incomplete data on outcomes, which weakens the present network meta‐analysis. Fourth, it was not possible to estimate the effect of treatment duration for all hydration strategies because of multicollinearity and missing linkage. Moreover, the results of our meta‐regression are weakened by the lack of individual patient data. In addition, a legacy treatment effect could not be explored because of the lack of long‐term follow‐up. Minor differences in fixed hydration strategies employed in control groups may have introduced minor bias; however, all different hydration strategies employed are considered clinically equivalent, hence transitivity assumptions are not violated in the analysis.42, 43 Finally, it has to be acknowledged that our work did not take into consideration other currently available prevention strategies, which were not the focus of the present meta‐analysis. Indeed, hydration, despite being readily available and readily implementable, is not the sole strategy to reduce the risk of CI‐AKI. The amount of contrast plays a major role as well as the type of contrast employed, with contrast osmolarity possibly playing a role.44 In addition, adjunct treatment including periprocedural high‐intensity statin therapy as well as vasodilator treatment were shown to be safe and effective in abating CI‐AKI incidence.42

CONCLUSIONS

The present network meta‐analysis of 8 randomized controlled trials represents an updated synthesis of currently available evidence on hydration strategies for the prevention of CI‐AKI. Based on moderate certainty evidence, UFR‐guided hydration was found to provide the greatest efficacy for CI‐AKI prevention in patients undergoing coronary angiography and intervention. It was also found, albeit with very low certainty of evidence and modest effect size, to have a favorable safety profile with regard to pulmonary edema. On the other hand, standard‐of‐care fixed hydration regimens were shown to be the least effective in terms of CI‐AKI prevention. Further studies directly comparing different tailored hydration strategies are awaited to establish the most effective, safe, and convenient approach to minimize the incidence of this important complication.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

Dr Brilakis reports consulting/speaker honoraria from Abbott Vascular, American Heart Association (Circulation associate editor), Amgen, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Innovations Foundation (Board of Directors), Cardiovascular Systems, Inc (CSI), Elsevier, GE Healthcare, InfraRedx, Medtronic, Siemens, and Teleflex and research support from Regeneron and Siemens and is a shareholder of Minneapolis Heart Institute (MHI) Ventures. Dr Gurm reports consulting honoraria from Osprey Medical and research funding from the National Institutes of Health Center for Accelerated Innovation and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. Dr Azzalini received honoraria from Teleflex, Abiomed, Asahi Intecc, Abbott Vascular, Philips and Cardiovascular Systems Inc.

Supporting information

Data S1

Tables S1–S6

Figures S1–S5

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e021342. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.121.021342.)

Supplementary Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.021342

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsai TT, Patel UD, Chang TI, Kennedy KF, Masoudi FA, Matheny ME, Kosiborod M, Amin AP, Messenger JC, Rumsfeld JS, et al. Contemporary incidence, predictors, and outcomes of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: insights from the NCDR Cath‐PCI registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valle JA, McCoy LA, Maddox TM, Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM, Casserly IP, Nallamothu BK, Roe MT, Tsai TT, Messenger JC. Longitudinal risk of adverse events in patients with acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:e004439. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.116.004439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almendarez M, Gurm HS, Mariani J, Montorfano M, Brilakis ES, Mehran R, Azzalini L. Procedural strategies to reduce the incidence of contrast‐induced acute kidney injury during percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1877–1888. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wohlin C, ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) . Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery; 2014: 1–10. DOI: 10.1145/2601248.2601268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, Ioannidis JPA, Straus S, Thorlund K, Jansen JP, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta‐analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:777–784. DOI: 10.7326/M14-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng H‐Y, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaimani A, Salanti G. Using network meta‐analysis to evaluate the existence of small‐study effects in a network of interventions. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:161–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puhan MA, Schünemann HJ, Murad MH, Li T, Brignardello‐Petersen R, Singh JA, Kessels AG, Guyatt GH. A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g5630. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.g5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brignardello‐Petersen R, Bonner A, Alexander PE, Siemieniuk RA, Furukawa TA, Rochwerg B, Hazlewood GS, Alhazzani W, Mustafa RA, Murad MH, et al. Advances in the GRADE approach to rate the certainty in estimates from a network meta‐analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;93:36–44. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shim SR, Kim S‐J, Lee J, Rücker G. Network meta‐analysis: application and practice using R software. Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019013. DOI: 10.4178/epih.e2019013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaimani A, Higgins JPT, Mavridis D, Spyridonos P, Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta‐analysis in STATA. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76654. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonin FS, Borba HH, Mendes AM, Wiens A, Fernandez‐Llimos F, Pontarolo R. Description of network meta‐analysis geometry: a metrics design study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212650. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rücker G, Schwarzer G. Ranking treatments in frequentist network meta‐analysis works without resampling methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:58. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-015-0060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navarese EP, Khan SU, Kołodziejczak M, Kubica J, Buccheri S, Cannon CP, Gurbel PA, De Servi S, Budaj A, Bartorelli A, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of oral P2Y12 inhibitors in acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2020;142:150–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Gioia G, Sonck J, Ferenc M, Chen S‐L, Colaiori I, Gallinoro E, Mizukami T, Kodeboina M, Nagumo S, Franco D, et al. Clinical outcomes following coronary bifurcation PCI techniques: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis comprising 5,711 patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1432–1444. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stram DO. Meta‐analysis of published data using a linear mixed‐effects model. Biometrics. 1996;52:536–544. DOI: 10.2307/2532893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta‐analyses in R with the metafor Package. J Stat Softw. 2010;1:1–48. Available at: https://www.jstatsoft.org/v036/i03. Accessed May 6, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briguori C, Visconti G, Focaccio A, Airoldi F, Valgimigli M, Sangiorgi GM, Golia B, Ricciardelli B, Condorelli G. Renal insufficiency after contrast media administration trial II (REMEDIAL II): RenalGuard system in high‐risk patients for contrast‐induced acute kidney injury. Circulation. 2011;124:1260–1269. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.030759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marenzi G, Ferrari C, Marana I, Assanelli E, De Metrio M, Teruzzi G, Veglia F, Fabbiocchi F, Montorsi P, Bartorelli AL. Prevention of contrast nephropathy by furosemide with matched hydration: the MYTHOS (Induced Diuresis With Matched Hydration Compared to Standard Hydration for Contrast Induced Nephropathy Prevention) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:90–97. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brar SS, Aharonian V, Mansukhani P, Moore N, Shen AY‐J, Jorgensen M, Dua A, Short L, Kane K. Haemodynamic‐guided fluid administration for the prevention of contrast‐induced acute kidney injury: the POSEIDON randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1814–1823. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Usmiani T, Andreis A, Budano C, Sbarra P, Andriani M, Garrone P, Fanelli AL, Calcagnile C, Bergamasco L, Biancone L, et al. AKIGUARD (Acute Kidney Injury GUARding Device) trial: in‐hospital and one‐year outcomes. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2016;17:530–537. DOI: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian G, Fu Z, Guo J, Cao F, Chen Y. Prevention of contrast‐induced nephropathy by central venous pressure‐guided fluid administration in chronic kidney disease and congestive heart failure patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maioli M, Toso A, Leoncini M, Musilli N, Grippo G, Ronco C, McCullough PA, Bellandi F. Bioimpedance‐guided hydration for the prevention of contrast‐induced kidney injury: the HYDRA study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2880–2889. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marashizadeh A, Sanati HR, Sadeghipour P, Peighambari MM, Moosavi J, Shafe O, Firouzi A, Zahedmehr A, Maadani M, Shakerian F, et al. Left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure‐guided hydration for the prevention of contrast‐induced acute kidney injury in patients with stable ischemic heart disease: the LAKESIDE trial. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51:1815–1822. DOI: 10.1007/s11255-019-02235-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briguori C, D’Amore C, De Micco F, Signore N, Esposito G, Visconti G, Airoldi F, Signoriello G, Focaccio A. Left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure versus urine flow rate‐guided hydration in preventing contrast‐associated acute kidney injury. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2065–2074. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rihal CS, Textor SC, Grill DE, Berger PB, Ting HH, Best PJ, Singh M, Bell MR, Barsness GW, Mathew V, et al. Incidence and prognostic importance of acute renal failure after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2002;105:2259–2264. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000016043.87291.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCullough PA, Wolyn R, Rocher LL, Levin RN, O’Neill WW. Acute renal failure after coronary intervention: incidence, risk factors, and relationship to mortality. Am J Med. 1997;103:368–375. DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCullough PA, Sandberg KR. Epidemiology of contrast‐induced nephropathy. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4(suppl 5):S3–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azzalini L, Kalra S. Contrast‐induced acute kidney injury‐definitions, epidemiology, and implications. Interv Cardiol Clin. 2020;9:299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azzalini L, Spagnoli V, Ly HQ. Contrast‐induced nephropathy: from pathophysiology to preventive strategies. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:247–255. DOI: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann F‐J, Sousa‐Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, Byrne RA, Collet J‐P, Falk V, Head SJ, ESC Scientific Document Group , et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87–165. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ronco C, Bellomo R, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury. Lancet. 2019;394:1949–1964. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nijssen EC, Rennenberg RJ, Nelemans PJ, Essers BA, Janssen MM, Vermeeren MA, van Ommen V, Wildberger JE. Prophylactic hydration to protect renal function from intravascular iodinated contrast material in patients at high risk of contrast‐induced nephropathy (AMACING): a prospective, randomised, phase 3, controlled, open‐label, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1312–1322. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, Sokos G, Taylor DO, Starling RC, Young JB, Tang WHW. Importance of venous congestion for worsening of renal function in advanced decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:589–596. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ljungman S, Laragh JH, Cody RJ. Role of the kidney in congestive heart failure. Relationship of cardiac index to kidney function. Drugs. 1990;39(suppl 4):10–14. DOI: 10.2165/00003495-199000394-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Firth JD, Raine AE, Ledingham JG. Raised venous pressure: a direct cause of renal sodium retention in oedema? Lancet. 1988;1:1033–1035. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)91851-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winton FR. The influence of venous pressure on the isolated mammalian kidney. J Physiol. 1931;72:49–61. DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.1931.sp002761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunarro JA, Weiner MW. Effects of ethacrynic acid and furosemide on respiration of isolated kidney tubules: the role of ion transport and the source of metabolic energy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;206:198–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solomon R, Werner C, Mann D, D’Elia J, Silva P. Effects of saline, mannitol, and furosemide on acute decreases in renal function induced by radiocontrast agents. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1416–1420. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199411243312104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saugel B, Scheeren TWL, Teboul J‐L. Ultrasound‐guided central venous catheter placement: a structured review and recommendations for clinical practice. Crit Care. 2017;21:225. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-017-1814-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, Heard SO, Lipsett PA, Masur H, Mermel LA, Pearson ML, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) , et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter‐related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e162–e193. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cir257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Navarese EP, Gurbel PA, Andreotti F, Kołodziejczak MM, Palmer SC, Dias S, Buffon A, Kubica J, Kowalewski M, Jadczyk T, et al. Prevention of contrast‐induced acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiovascular procedures‐a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0168726. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cai Q, Jing R, Zhang W, Tang Y, Li X, Liu T. Hydration strategies for preventing contrast‐induced acute kidney injury: a systematic review and bayesian network meta‐analysis. J Interv Cardiol. 2020;2020:7292675. DOI: 10.1155/2020/7292675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Premawardhana D, Sekar B, Ul‐Haq MZ, Sheikh A, Gallagher S, Anderson R, Copt S, Ossei‐Gerning N, Kinnaird T. Routine iso‐osmolar contrast media use and acute kidney injury following percutaneous coronary intervention for ST elevation myocardial infarction. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2019;67:380–391. DOI: 10.23736/S0026-4725.19.04925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Kidney Foundation . K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF III, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, Lasic Z, Iakovou I, Fahy M, Mintz GS, Lansky AJ, Moses JW, Stone GW, et al. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast‐induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1393–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gurm HS, Seth M, Kooiman J, Share D. A novel tool for reliable and accurate prediction of renal complications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2242–2248. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Tables S1–S6

Figures S1–S5