Abstract

Introduction:

Polymorphic gene variants, particularly the genetic determinants of low dopamine function (hypodopaminergia), are known to associate with Substance Use Disorder (SUD) and a predisposition to PTSD. Addiction research and molecular genetic applied technologies supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have revealed the complex functions of brain reward circuitry and its crucial role in addiction and PTSD symptomatology.

Discussion:

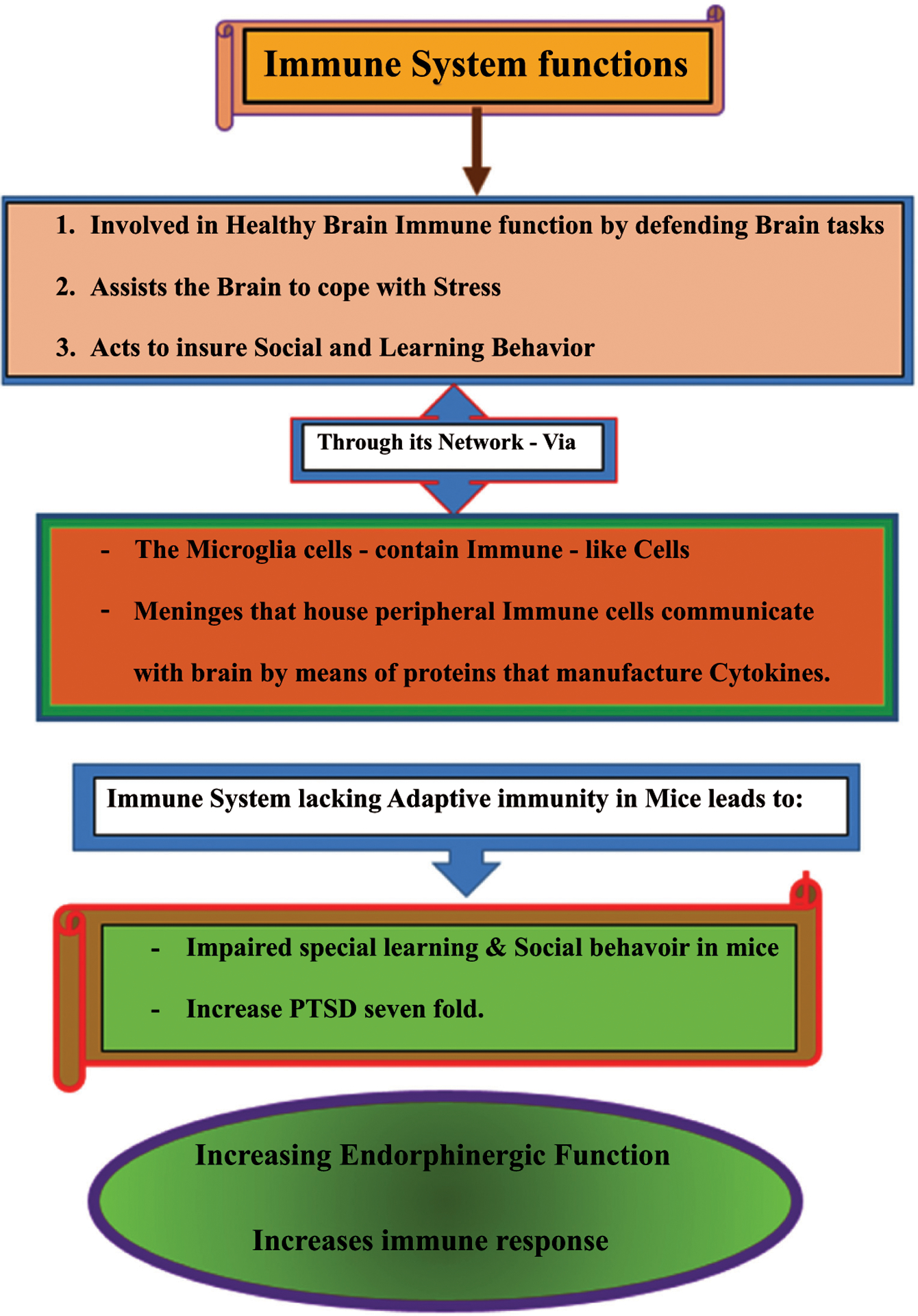

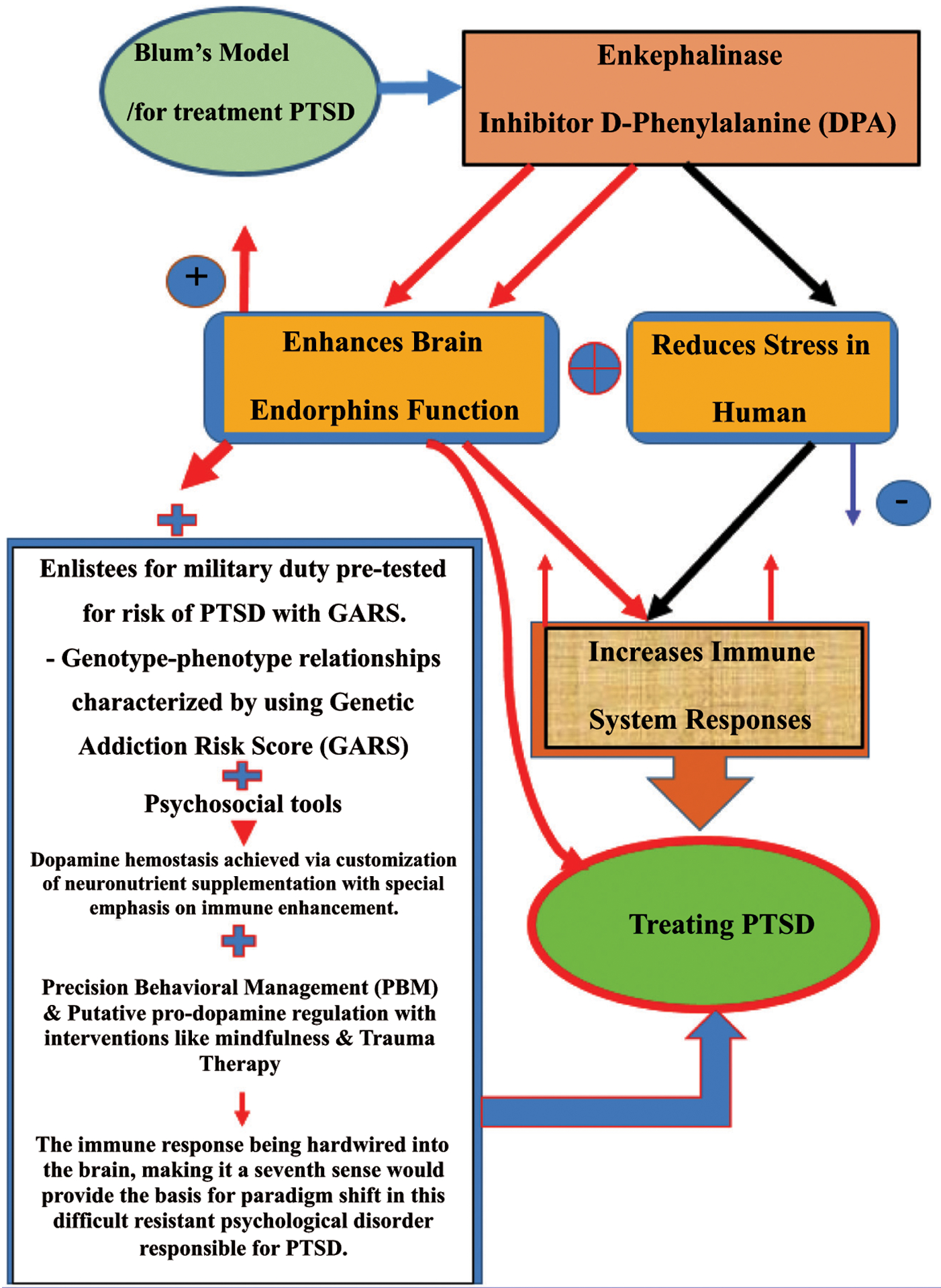

It is noteworthy that Israeli researchers compared mice with a normal immune system with mice lacking adaptive immunity and found that the incidence of PTSD increased several-fold. It is well established that raising endorphinergic function increases immune response significantly. Along these lines, Blum’s work has shown that D-Phenylalanine (DPA), an enkephalinase inhibitor, increases brain endorphins in animal models and reduces stress in humans. Enkephalinase inhibition with DPA treats Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) by restoring endorphin function. The Genetic Addiction Risk Severity (GARS) can characterize relevant phenotypes, genetic risk for stress vulnerability vs. resilience. GARS could be used to pre-test military enlistees for adaptive immunity or as part of PTSD management with customized neuronutrient supplementation upon return from deployment.

Conclusion:

Based on GARS values, with particular emphasis on enhancing immunological function, pro-dopamine regulation may restore dopamine homeostasis. Recognition of the immune system as a “sixth sense” and assisting adaptive immunity with Precision Behavioral Management (PBM), accompanied by other supportive interventions and therapies, may shift the paradigm in treating stress disorders.

Keywords: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Genetic Addiction Risk Severity (GARS™), Pro-dopamine regulation (KB220PAM), hypodopaminergia, immune system, endorphinergic

1. BACKGROUND

The purpose of this review is to help understand the unfortunate fact that in the face of a worldwide viral pandemic, a large part of society has been in a state of extreme stress with insults to the brain reward system and potential induction of PTSD. It has become increasingly clear that PTSD may link to a compromised neuroimmune system. This review profiles some molecular neurobiological phenomena relevant to PTSD in the general population and may have particular importance to armed services.

Three decades of gene-based research identified and characterized the Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS) that includes impulsive, compulsive, and addictive behaviors. This article involves a new evidence-based model for the prevention and treatment of all RDS behavioral types, not just those for which there are known genetic causes. It is crucial to acknowledge that stress is indeed a primary culprit to altering normal brain function. The novel adoption of “Precision Behavioral Management” (PBM) seems imminent. Indeed, more research to pinpoint the most appropriate candidate genes related to addiction-prone risk is necessary, but the development of PBM has already begun. Personalized, precision medicine identifies Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) of candidate reward genes associated with populations with RDS [1].

The environment, manifest by an epigenetic switch that controls gene expression, is thought to contribute about fifty percent to the genetic risk for many psychological disorders. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a good example of environmental stress compounding the genetic risk. Individuals who have PTSD are also known to have hypodopaminergia, which triggers co-morbidity with (SUD) [2]. New research directed towards up-regulation of mesolimbic dopamine, as suggested by the NIDA aims to restore homeostasis [3] and eventually be supported in the scientific community.

The importance of core reward circuitry neurotransmitters in the brain’s prefrontal cortices was not well understood. The idea of addiction as a disease did not hit until the early 1960s. The discrete functions of acetylcholine, serotonin, cannabinoids, GABA, dopamine, and endorphins were unknown. In 1956, the alcoholism concept, introduced by Dr. Jellinek, without much scientific support, was shocking and not generally accepted [4]. However, at that time, most addiction scientists agreed that deficiencies or imbalances in brain chemistry-perhaps, genetic in origin-were at least in part the cause of alcoholism, and alcohol per se was an allergen.

Virginia Davis, Michael Collins, Gerald Cohen, and others did initial work related to the interface of alcohol and opioid use disorders involving condensation of alcohol, acetaldehyde, and dopamine resulting in the novel substance class known as isoquinolines [5–9]. Blum investigated the neurochemical mechanisms of alcohol and opioids from the 1970s and, in the mid-1990s, developed the concept of Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS) published by The Royal Society of Medicine in 1996 [10]. There have been 1,328 (1/7/21) Reward Deficiency articles listed within PubMed, and The SAGE Encyclopedia of Abnormal and Clinical Psychology included the RDS concept in 2017 [1]. Cross-addictions occur, primarily, in psychiatric illnesses, including PTSD [11]. Cocaine use in PTSD is prevalent and associated with treatment failure, health, and societal consequences. Cocaine use and abuse appear to increase the risk of PTSD symptoms, especially in females [12]. This risk increase is not surprising since significant cocaine abuse leads to hypodopaminergia, which intensifies many PTSD symptoms, including nightmares. Mark Gold’s dopamine depletion hypothesis proposed a vital role for dopamine in the effects of cocaine. Dackis and Gold suggested that chronic Cocaine Use Disorder (CUD) development was due to the acute activation of central dopamine neurons and the euphoric properties of cocaine. Acute overstimulation of dopamine neurons and excessive synaptic metabolism responsible for depleting dopamine may bring about cocaine abstinence dysphoria and cocaine use urges [13], including an inability to cope with stressful events.

These neurochemical disruptions caused by cocaine were identified as “physical” rather than “psychological” addiction [14]. Dopamine depletion due to CUD was treated with dopamine agonist therapy. After a single dose of the potent dopamine D2 agonist, bromocriptine cocaine craving was significantly reduced [15]. Open trials of low dose implied that bromocriptine might be useful in cocaine detoxification and prove to be an effective, non-addictive pharmacological treatment for CUD. Ernest P. Nobel, now deceased, directed a placebo-controlled bromocriptine study to treat subjects with Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) [16]. The best results occurred in the bromocriptine-treated subjects with the DRD2 A1 allele (first associated with severe alcoholism in 1990 by Blum et al. [17]), while the worst result occurred in the placebo-treated A1 subjects [16]. Unfortunately, this potent D2 agonist’s chronic administration induced significant down-regulation of D2 receptors, thereby negating its clinical usefulness [18, 19]. This lead to Blum et al. proposal that milder therapeutic, neuro-nutrient formulations could accomplish D2 receptor agonism to help attenuate stressful events [20].

Blum group favored encouraging dopamine release, using KB220; mild, neuro-nutrient formulations, to stimulate human mRNA expression and D2 receptor proliferation [21] to diminish craving and alleviate stress. Based on this model, research studies showed significant reductions in rodent alcohol craving behavior and craving in genetically bred alcohol-preferring rodents and reduced self-administration of cocaine following gene therapy involving overexpression of DRD2 receptors [22, 23]. Essentially, increasing D2 receptors caused craving for psychoactive substances and even non-drug addictive behaviors to abate.

The chronic promotion of dopaminergic activation by lower potency dopaminergic repletion therapy (KB220Z) has been a clinically effective treatment modality for RDS behaviors, including PTSD, SUD, Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and obesity [24]. Experiments using fMRI in both animals and humans identified resting-state functional connectivity increases and neuronal recruitment, following acute doses of neuro-nutrients therapy, within 15 minutes (animal) to 60 minutes (human), post-administration of KB220Z. Additional dopamine neuronal firing reward processing areas of the brain indicated possible neuroplasticity [25, 26].

2. WHAT HAS NEUROIMAGING REVEALED ABOUT PTSD?

Neuroimaging techniques have identified the Default Mode Network (DMN), which includes the medial temporal regions, lateral parietal cortices, and the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus [27]. In healthy individuals, dopamine is a known substrate of the DMN, most active during rest from cognitive tasks like remembering. The DMN is involved in self-processing at rest, which can be perturbed by stress [28, 29].

PTSD psychopathology involves the amygdala (fear) and hippocampus (memory recall), and physiologically patients with severe PTSD symptoms presented with decreased neuronal tissue in the anterior right hippocampus [30] and the right amygdala (corresponding to the Centro-medial Amygdala) [31]. Akiki et al. followed up their neuroimaging research with a stepwise regression analysis, which indicated that arousal symptoms of PTSD were associated with tissue indentation in the hippocampus, and re-experiencing traumatic events explained amygdala abnormality [31].

Martindale et al. [32] reported that white matter hyperintensities correlated significantly with the blast intensity of the explosion; however, this finding was independent of diagnosis.

Averill et al. [33] discovered reduced cortical thickness in the left temporal regions correlated with combat exposure severity. There was an interaction between combat exposure severity and PTSD diagnosis in the superior temporal/insular region and a stronger negative correlation between combat exposure severity and cortical thickness in the non-PTSD group [31].

Both van Wingen [34] and colleagues and Butler et al. [35] found that some of the physiological changes caused by prolonged stress can be reversed. Van Wingen et al. [34] found that attention deficits were normalized within 18 months and midbrain to prefrontal cortex functional connectivity deficits continued. Butler et al. [35] observed an increase in amygdala volume and an increase in hippocampal volume following six weeks of mental health treatment.

Executive functional deficits due to prolonged stress results from alterations within the mesofrontal circuit involving dopaminergic activation [29]. The neurotransmitter dopamine functions within the mesolimbic ventral tegmental area to relieve stress, enhance wellbeing, and provide motivation [36]. These alterations from combat stress may be partially reversible, and immediate treatment may result in epigenetic mitigation of PTSD symptoms [37].

3. NEURO-IMMUNOLOGICAL FUNCTION, ADAPTATION OF STRESS & SOCIAL BEHAVIOR

The goal is to understand how the immune system provides an enhanced defense against specific pathogens and how homeostatic immune surveillance of all tissues, including the brain, occurs. The Jonathan Kipnis group is the foremost authority on this remarkable new thinking that has profound promise for new therapeutic targets for cognitive and even social brain function [38]. They suggest that initially inflammatory cytokines increase a host-host transmission by exploiting the pro-social effects of interferon-regulated genes. Later the inflammatory cytokines were recycled by the host to form part of an immune defense program. Like a host pathogen’s arms race, this CNS immune surveillance is crucial for recovery from injury and healthy brain function [38].

A series of early investigations have suggested that the beneficial effect of T-cells after traumatic CNS injury is the mediation of autoreactive T-cells specific for brain antigens [39–43]. The immune system, mainly through T-cells, effects CNS function in health and disease. There is evidence that brain immune cells play a vital role in learning and memory. Early work revealed that Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) mice perform poorly in the Morris water maze and other memory and spatial learning tasks [44, 45]. Specifically, reconstituting the T cell compartment rescued learning and memory in SCID mice [45].

Moreover, in support of the specific influence of T cells on learning behavior, it is known that mice lacking B cells display no impairment of learning behavior [46]. It is noteworthy that SCID mice show impaired social behavior as indicated in the three-chamber sociability assay [47], which determines the preference of a test mouse to investigate a novel mouse over a novel object [48]. Notably, while we do not know how long the effect lasts, social behavior deficits were rescued four weeks after repopulation with wild-type lymphocytes.

Along these lines, mice that lack T cells in a model of PTSD also exhibit heightened susceptibility [49], impaired maternal behavior, and exhibit compulsive grooming behaviors [50], representative of reward deficiency. In terms of physiology, it is worth noting that while perivascular macrophages and microglia patrol the brain parenchyma, the meningeal spaces have a diverse immune repertoire dedicated to neuro-immune crosstalk allowing the brain to perform optimally [51–54].

According to most social scientists, social or aggregation behavior is critical not only for survival and evolution but also for the spread of infectious organisms. Thus, coordinated immunity and sickness behavior have evolved to limit the spread of pathogens. Hart [55] argued that sickness behavior is not a maladaptive response to infection but rather a coordinated behavioral plan to promote host survival. More recently, Shakhar and Shakhar attributed altruism and kin selection sickness behavior [56]. Another intriguing argument is that carriers of specific gene polymorphisms may flock together concerning sickness behavior or psychological or psychiatric disorders [57, 58]. In support of this notion, Blum’s group [59] has proposed that political, spiritual, and social behaviors may be tied to inheritable reward gene polymorphisms, as seen in addictions and PTSD. For example, both drinking (alcohol) and obesity seem to cluster in large social networks influenced by friends having the same genotype, such as the DRD2 A1 allele. This clustering effect may have an evolutionary advantage for the heard and general population. While many polymorphic risk alleles load onto the PTSD phenotype, Comings, Muhleman, and Gysin [60] provided the first genetic evidence that the DRD2 A1 allele associates with PTSD. Concerning the immune response, it is well-known that the inflammatory response promoted by TNF-alpha causes many clinical problems associated with autoimmune disorders and psychiatric issues. Indeed, Petrullj et al. [61] clearly showed that increases in systemic inflammation enhance stimulant-induced striatal dopamine elevation linked to higher TNF-alpha plasma levels. The question could augmented-neuroimmunological function be coupled with increased dopamine to attenuate stressful events, including trauma? While this question must await required basic research in animal models and humans, a more straightforward approach is to find ways to enhance the immune response by manipulating specific transduction signaling by targeting the endorphinergic system.

4. ENDORPHINS AND ENHANCEMENT OF IMMUNE FUNCTION AND STRESS

It is well-known that the Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF), synthesized in the hypothalamus, stimulates the release of pituitary peptides derived from the precursor molecule, Proopiomelanocortin (POMC). These peptides not only include Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH), but a variety of Endogenous Opiate Peptides (EOP) from the endorphin family. Chemically, endorphin is a 31 amino acid molecule, with specific fragments such as 5 (Met-enkephalin) and other endorphins. The resting circulating concentration of endorphin lies in the low picomolar range and increases following various forms of stress [62].

B-endorphins binds to opiate receptors through its N-terminal sequence, and N-terminal acetylation blocks this binding. The C-terminal sequence binds to different non-opiate receptors [63]. Importantly, there is evidence that lymphocytes have receptors for these EOP. Moreover, the binding of Met-enkephalin and morphine to T-cells prevented by naloxone, suggesting that T-lymphocytes express opiate receptors [64]. The link between the central nervous system and the immune system may be the surface receptor-like structures for morphine, dextromoramide, and methionine-enkephalin observed on normal human blood T-lymphocytes.

The endogenous opioid peptides have many significant effects on immune function. For a few examples, in vivo, treatment of mice with Met and Leu-enkephalin protects against challenge with L1210 leukemic cells [65]. Also, endorphins modulate proliferative responses to mitogens in vitro [66]. McCain, Lamster, and Bilotta [67] claim that at specific concentrations, endorphins also inhibit the induction of suppression by Concanavalin A (ConA), which functions as a T cell regulator in humans. According to Wybran [68], EOP also enhances Natural Killing (NK) cells, and the enhancement can be reversed by naloxone. Johnson, Smith, Torres & Blalock [69] showed that endorphins block specific antibody production in rodents.

In summary, it is noteworthy that stress rapidly increases the secretion of B-endorphin from the pituitary gland [62, 70]. Soldiers who had higher numbers of glucocorticoid receptors (involved in stress response) on their leukocytes were more likely to develop PTSD after experiencing traumatic stress [71]. Since stress and trauma effect the immune response, these changes in the immune response may correlate to changes in circulating endorphins. Smith, Morrill, Meyer & Blalock [72] suggested that lymphocytes can synthesize immunoreactive ACTH and endorphin-like peptides. The importance here is that EOP produced by activated lymphocytes themselves may be highly potent modulators of the final immune effector response. Moreover, the opioid peptide-induced immuno-stimulating effect may involve the dopaminergic system [73, 74]. These endorphinergic effects on the immune system [75] and its potential enhancement of the immune response, especially under stressful conditions, provide the rationale to increase endorphinergic function epigenetically by inhibiting the enzyme enkephalinase [76].

4.1. Raising the Endorphin Function via Enkephalinase Inhibition

The carboxypeptidase enzyme (enkephalinase) cleaves methionine-enkephalin into non-opioid fragments, and as such, the activity of the parent compound finishes. The enkephalinergic neuroendocrine-immune regulatory system is well known as one of the most critical neuroendocrine-immune systems in humans. The neurotransmitter [Met5]-enkephalin released by the neuroendocrine system regulates the developing immune system. An enzyme enkephalinase inhibitor reduces the activity of the enkephalinase class that breaks down the endogenous enkephalin-opioid-peptides. A few examples include racecadotril, bestatin, RB-101, D-phenylalanine, opioid peptides, opiorphin, thiorphin, and spinorphin [77].

In 1987, Blum et al. provided the first report showing that in alcohol-preferring mice, with concomitant genetically compromised innate brain enkephalin deficiencies, raising brain enkephalins using acute and chronic treatment with D-phenylalanine (an enkephalinase inhibitor) significantly attenuate both volitional and forced ethanol intake. Since these agents, through their enkephalinase inhibitory activity, raise brain enkephalin levels, Blum et al. proposed that alteration of endogenous brain opioid peptides can regulate excessive alcohol intake. Understanding that both drug-seeking behavior and PTSD have a common neurochemical and genetic mechanism, and as proposed in this review, neuroimmunological regulation is tantamount to overcoming PTSD symptoms. This novel proposal of raising endorphin function by inhibition of the enkephalinase enzyme seems prudent. Studies have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory activity of D-phenylalanine in the rat paw test [76, 78].

It is noteworthy that Nagarjun et al. [79], as recently as 2017, showed that a chromium complex of D-phenylalanine [complex (Cr (d-phe)3)] demonstrated the protective effect of Cr (d-phe)3 against indomethacin-induced Irritable Bowel Disorder (IBD) in rats. The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of Cr (d-phe)3 might be responsible for this protective effect. This finding is of particular interest since Febo, Blum, Badgaiyan, Perez, Colon-Perez et al. [80] provided resting-state Functional Magnetic Resonance Imagining (rsfMRI) evidence for BOLD activation of the dopaminergic pathways in the brain reward circuitry with a complex KB220Z containing both Cr and D-phenylalanine.

5. UNDERSTANDING GENETICS OF PTSD

As mentioned earlier, the first study to show an association between a reward gene, the A1 allele form of the dopamine D2-receptor gene, and military veterans diagnosed with PTSD was carried out by David Comings from the City of Hope [60]. Carriers of this gene form associated with severe alcoholism by the Noble, Blum group have 30–40 percent less dopamine D2 receptors in the brain [81].

Along these lines, low dopamine-function is associated with increased risk for PTSD [37]. Dopamine is released from neurons 100 times above the resting state to cope with the extreme stress of combat [82–84]. This insult release depletes dopamine, combined with trait hypodopaminergia (fewer dopamine D2 receptors), or chronic repeated insult, can cause PTSD. Post-traumatic stress disorder is hereditary. Compared to non-identical (dizygotic) twins, identical (monozygotic) twins with PTSD, associated with an increased risk of their co-twins having PTSD following combat exposure in Vietnam [85].

Moreover, there is evidence that those with smaller hippocampi (a region of the brain involving memory), perhaps due to genetic differences, are more likely to develop PTSD following traumatic stress [30]. Post-traumatic stress disorder shares many genetic influences with other psychiatric disorders; for example, 60% of the genetic variance of panic and generalized anxiety disorders and substance addictions share greater than 40% genetic similarity [86].

Most importantly, environmental insults like childhood abuse induce epigenetic changes that impact brain chemistry. Instead of being caused by differences within the DNA sequence, epigenetic changes caused by external or environmental factors that switch genes on and off and phenotypic traits; cellular, physiological, and behavioral characteristics that can continue for at least two subsequent generations [87]. These environmentally induced epigenetic changes in DNA chromatin structure can reduce dopamine D2 receptor gene expression and function, leading to PTSD symptoms.

Genetic polymorphisms that regulate gene expression within the serotonergic and dopaminergic pathways are evident in the development of PTSD. The 5-HTTLPR (promoter region of SLC6A4, which encodes the serotonin transporter) is a genetic candidate region responsible for modulating emotional responses to traumatic events. Furthermore, the variation of the 5HTTLPR gene coupled with stressful life events can predict depression and PTSD. The dopaminergic pathway, specifically, the A1 allele coding the type 2 dopaminergic receptor, is associated with severe co-morbidity of PTSD, with many reward deficiency behaviors. For example, the polymorphism of the GABRA2 gene is associated with the occurrence of PTSD. The Val (158)Met polymorphism of the gene coding for catecholamine-o-methyltransferase is associated with the number of traumatic events [2]. Also, other genes include polymorphisms in FKBP5 (a co-chaperone of hsp 90, which binds to the glucocorticoid receptor) predicts risk for PTSD, with a gene-by-environment interaction [88].

Zhang, Wang, Cao, Li, Fang, et al. [89] analyzed the association of the DRD2/ANNK1-COMT genes located at (rs1800497 × rs6269) with PTSD diagnosis (p-interaction = 0.0008055 and p-corrected = 0.0169155). The Chinese earthquake exposed female-cohort (32 cases and 581 controls), p-interaction = 0.01329) results suggested that rs1800497 is related to the dopamine receptor D2 density and rs6269-rs4633-rs4818-rs4680 haplotypes affect the catechol O-methyltransferase level and enzyme activity. These genotypes may be a possible origin of dopamine homeostasis abnormalities in PTSD.

Identification of individuals faced with military combat who carry high-risk alleles for PTSD is a persuasive potential use of the GARS test. One of the polymorphic variants measured in GARS, specifically the DRD2 A1 allele, has been associated with PTSD and comorbid substance use disorder [60]. Of 24 patients in an addiction treatment unit who met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD after exposure to severe combat conditions in Vietnam, 58.3% carried the D2A1 allele. 12.5% of the eight patients without PTSD were carriers of the D2A1 allele (p< 0.04). Subsequently, in a replication study, using 13 PTSD patients, 61.5% carried the D2A1 allele, 11 without PTSD did not carry the allele D2A1 (p< 0.002). For the combined group, 5.3% of those who did not have PTSD compared to 59.5% with PTSD carried the D2A1 (p< 0.0001) [60]. These results suggest that the DRD2 variant in linkage disequilibrium with the D2A1 allele confers an increased risk for PTSD, and the absence of the variant confers relative resistance to PTSD.

6. CAN WE PREVENT OR TREAT PTSD?

Galatzer-Levy et al. [87] used Latent Growth Mixture Modeling (LGMM) supervised Machine Learning (ML) to identify individuals by clustering them into symptom progression trajectories. The trajectories and graphic algorithms examined causal paths to data from a large (n = 153) longitudinal study of the neuroendocrine response to a traumatic event, from ER endocrine markers and PTSD status at ten days, one month, five months later. Saliva and blood samples each morning of follow-up assessment included lymphocytes glucocorticoid-receptor density, saliva cortisol plasma cortisol, Norepinephrine (NE), and Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH). They found that reduced neuroendocrine response in the ER was dependent on a report of early childhood trauma exposure; this was consistent with evidence that early life abuse produces a blunted cortisol response to trauma in animal models. The authors suggest that this predictive of abnormal stress responses and implicates to genomic and molecular mechanisms for further investigation, and those abnormal cortisol responses to trauma associate with multiple genetic, epigenetic, and proteomic elements, including FKBP5 among many others, and maybe manageable therapeutic targets in the context of traumatic emergencies including military personnel deployed to war zones.

Certainty, early identification of PTSD risk will have preventative benefits if adopted by the Department of Defense (DOD). With that stated, early access to trauma and cognitive behavioral therapy has been modestly beneficial in treating PTSD [90]. Also, Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) suggested as a means of preventing PTSD is “an integrated, multi-component continuum of psychological interventions to be provided in the context of acute adversity, trauma, and disaster on an, as needed, basis to appropriate recipient populations [91].” Critical Incident Stress Management is either a technique or a treatment for acute stress disorder, PTSD, post-traumatic depression, bereavement, or grief [91]. The World Health Organization (WHO) explicitly recommends against treatment with benzodiazepines and antidepressants in trauma victims. Some evidence supports the use of hydrocortisone for its anti-inflammatory effect in preventing PTSD symptoms in adults, which dovetails with the proposal herein to use endorphins for their anti-inflammatory effects to combat the development of PTSD. There is scant evidence to support other drugs, like propranolol, escitalopram, temazepam, or gabapentin. Indeed, gabapentin stimulates the neurotransmitter GABA and reduces dopamine effects should not be used to treat PTSD, especially in the long-term [92].

In response to these recommendations and therapeutic evidence, this proposal uses a pro-dopamine regulator (KB220Z). Thomas McLaughlin and others have published studies that showed that chronic administration of a nutraceutical, KB220Z, eliminated terrifying, lucid nightmares in at least 83% of patients with PTSD and comorbid ADHD [93, 94]. The voluntary withdrawal of the pro-dopamine regulator resulted in the reinstatement of the terrifying, non-pleasant nature of the dreams signifying that the reduction or elimination of terrifying nightmares depended on KB220Z. Most of the patients reported gradual, and then complete, amelioration of their long-term, terrifying nightmares (lucid dreams) while taking KB220Z [95]. Remarkably, we show that in at least four cases, the amelioration of nightmares persisted for up to 12 months after a self-initiated withdrawal of the use of KB220Z [93]. Increased connectivity volume and recruitment of more dopamine neurons and neuronal dopamine firing in the brain reward site in rodents suggests the induction of epigenetic changes (neuroplastic adaptation). These adaptations may be involved in the cessation of human lucid dreaming and nightmares [95].

7. ETHICAL ISSUES IN GENOMIC TESTING IN MILITARY

There have been several articles related to the ethics of performing genomic or genetic testing in the military. There are controversies and different schools of thought related to this interesting topic. One important article in 2014 by Mehlman and Li suggested that utilizing genomic or genetic testing of soldiers before military entry may have heuristic value in terms of PTSD vulnerability and peripheral issues, including traumatic bone fracture and blood loss [96]. There are currently discussions in military circles about the idea that genetic testing may result in better performance. Indeed, the addition of genetic testing may augment current selection procedures used to identify particular roles or positions within military services. However, there are crucial issues that must be addressed before genetic testing in this vital cohort. These include the following: a) one’s genes may determine 50% of any phenotype; when it relates to strength, the capacity to develop muscle or retain body fat, intelligence, or memory recall-these are functions of the environment (epigenetic) as much as they are of genetics; b) in terms of performance, a genetic test may not provide data to help select appropriate skills required in the military; c); there may also be both economic and ethical issues to overcome; d) the push for $100 genomic test while seems to be cost-effective may impose a burden in terms of interpretation of any military-related trait. Finally, while these caveats represent ethical and economic issues, the authors of this article believe that a simple GARS test to understand the vulnerability of soldiers faced with extremely stressful conditions and the potential induction of PTSD may be informative as one way to reduce harm [97–100].

CONCLUSION

Thus, neuroimmunological function enhancement through enkephalinase inhibition using the mechanism of action of KB220 variants, especially as customized through recently introduced Precision Behavioral Management (PBM), is recommended [96]. In order to assist us in identifying potential military candidates who would be less well suited for combat than those without high-risk alleles, the suggestion is that, before combat, soldiers with a background of childhood violence within the family would benefit from being tested for high-risk genetic variants. Also, using safe methods to treat individuals at high risk prophylactically and those already exposed to combat and known to have PTSD. This proposed process would also greatly benefit individuals returning from deployment to help diminish triggering traumatic experiences and foster societal reassimilation. Based on the fact that the immune system plays a critical role in regulating social behavior as discussed above, the proposal of enhancing neuroimmunological function by raising endorphin activity via enkephalinase inhibitors such as D-phenylalanine as utilized in PMB seems prudent (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Healthy immune system function increases endorphinergic activity, which treats PTSD.

Finally, following a GARS test to identify gene polymorphisms (variations) known to increase the risk for substance use disorder in individuals with PTSD, due to hypodopaminergic reward circuitry function, administration of precision, pro-dopamine regulators, like KB220, might be a reasonable way to provoke epigenetic reward gene expression (mRNA) to overcome this deficiency (Fig. 2) [56, 101–105].

Fig. (2).

Maps PTSD, stress, endorphins, immune system, GARS, KB220 variants, and precision behavioral management.

In Fig. (2), neurochemical measurement showed that the enkephalinase inhibitor D-Phenylalanine (DPA) not only increased brain endorphins but also reduced stress in humans. Considering these and other facts, it seems prudent that one way to treat PTSD is to enhance endorphin function by utilizing enkephalinase inhibitors like DPA. Moreover, using the (GARS) test, the relevant genotype-phenotype relationships can be characterized and Psychosocial tools. GARS could be used to pre-test military enlistees for adaptive immunity or as part of PTSD management. Based on the GARS test values, customized supplementation of neuro-nutrients may achieve dopamine homeostasis, emphasizing the enhancement of immunological function. “Precision Behavioral Management” (PBM) and putative pro-dopamine regulation should be accompanied by interventions like mindfulness and trauma therapy and all types of psychological and behavioral modalities. The suggestion that the immune response requires reconsideration in this severe resistant disorder responsible for PTSD induced unwanted deaths seems prudent.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The basis of an NIH grant awarded to Drs Kenneth Blum and Marjorie C. Gondré-Lewis, [R41 MD012318/MD/NIMHD NIH HHS/United States] is research directed toward improving substance use disorders, especially in under-served populations. The National Institutes of Health partially fund Dr. Thanos, the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism, AA11034, and Research Foundation of New York, RIAQ094. We thank Danielle Kradin for formatting the reference list and expert edits by Margaret A Madigan. Rajendra D. Badgaiyan is supported by the National Institutes of Health grants 1R01NS073884 and 1R21MH073624; Panayotis Thanos is the recipient of R01HD70888-01A1. While this article is not a meta-analysis or highly referenced review, it does portray the authors’ proposal to assist the people living with PTSD during the COVID 19 pandemic.

FUNDING

This study is funded by The National Institutes of Health, grant numbers: 1R21MH073624, 1R01NS073884, RIAQ094, AA11034, R41 MD012318/MD/NIMHD NIH HHS/United States, R01HD70888-01A1.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Kenneth Blum is the Editor-in-Chief of Current Psychopharmacology (CPSP).

Dr. Blum has percent ownership in Geneus Health, LLC. Drs. Blum and Raymond Brewer are officers of Geneus Health, LLC. Drs. Baron, Thanos, Elman, Modestino, McLaughlin, Badgaiyan are members of the Scientific Advisory Board of Geneus Health, LLC. B. William Downs is President of Victory Nutrition International, LLC., a company promoting GARS and Pro-Dopamine regulators licensed from Geneus Health, LLC. Victory Nutrition International, LLC, employs Dr. Bagchi.

REFERENCES

- [1].Blum K Reward deficiency syndrome.The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology. University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine: USA: Sage Publications Inc. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bowirrat A, Chen TJ, Blum K, et al. Neuro-psychopharmacogenetics and neurological antecedents of posttraumatic stress disorder: unlocking the mysteries of resilience and vulnerability. Curr Neuropharmacol 2010; 8(4): 335–58. 10.2174/157015910793358123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Elman I, Borsook D. Common brain mechanisms of chronic pain and addiction. Neuron 2016; 89(1): 11–36. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jellinek E The disease concept of alcoholism. Italy: New Heaven: College and University Press. 1960. 10.1037/14090-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Davis VE, Walsh MJ. Alcohol addiction and tetrahydropapaveroline. Science 1970; 169(3950): 1105–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hamilton MG, Blum K, Hirst M. Identification of an isoquinoline alkaloid after chronic exposure to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1978; 2(2): 133–7. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1978.tb04713.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Collins MA, Kahn AJ. Attraction to ethanol solutions in mice: induction by a tetrahydroisoquinoline derivative of L-DOPA. Subst Alcohol Actions Misuse 1982; 3(5): 299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cohen G, Collins M. Alkaloids from catecholamines in adrenal tissue: possible role in alcoholism. Science 1970; 167(3926): 1749–51. 10.1126/science.167.3926.1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Blum K, Hamilton MG, Hirst M, Wallace JE. Putative role of isoquinoline alkaloids in alcoholism: a link to opiates. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1978; 2(2): 113–20. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1978.tb04710.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Blum K, Sheridan PJ, Wood RC, et al. The D2 dopamine receptor gene as a determinant of reward deficiency syndrome. J R Soc Med 1996; 89(7): 396–400. 10.1177/014107689608900711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Brady KT, Killeen TK, Brewerton T, Lucerini S. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(Suppl. 7): 22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Saunders EC, Lambert-Harris C, McGovern MP, Meier A, Xie H. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among addiction treatment patients with cocaine use disorders. J Psychoactive Drugs 2015; 47(1): 42–50. 10.1080/02791072.2014.977501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dackis CA, Gold MS. Bromocriptine as treatment of cocaine abuse. Lancet 1985; 1(8438): 1151–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92448-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Noble EP, Blum K, Khalsa ME, et al. Allelic association of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 1993; 33(3): 271–85. 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90113-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dackis CA, Gold MS, Sweeney DR, Byron JP Jr, Climko R. Single-dose bromocriptine reverses cocaine craving. Psychiatry Res 1987; 20(4): 261–4. 10.1016/0165-1781(87)90086-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lawford BR, Young RM, Rowell JA, et al. Bromocriptine in the treatment of alcoholics with the D2 dopamine receptor A1 allele. Nat Med 1995; 1(4): 337–41. 10.1038/nm0495-337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Blum K, Noble EP, Sheridan PJ, et al. Allelic association of human dopamine D2 receptor gene in alcoholism. JAMA 1990; 263(15): 2055–60. 10.1001/jama.1990.03440150063027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bogomolova EV, Rauschenbach IY, Adonyeva NV, Alekseev AA, Faddeeva NV, Gruntenko NE. Dopamine down-regulates activity of alkaline phosphatase in Drosophila: the role of D2-like receptors. J Insect Physiol 2010; 56(9): 1155–9. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rouillard C, Bédard PJ, Falardeau P, Dipaolo T. Behavioral and biochemical evidence for a different effect of repeated administration of L-dopa and bromocriptine on denervated versus non-denervated striatal dopamine receptors. Neuropharmacology 1987; 26(11): 1601–6. 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Blum K, Chen AL, Chen TJ, et al. Activation instead of blocking mesolimbic dopaminergic reward circuitry is a preferred modality in the long term treatment of reward deficiency syndrome (RDS): a commentary. Theor Biol Med Model 2008; 5: 24. 10.1186/1742-4682-5-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Blum K, Oscar-Berman M, Stuller E, et al. Neurogenetics and nutrigenomics of neuro-nutrient therapy for reward deficiency syndrome (rds): clinical ramifications as a function of molecular neurobiological mechanisms. J Addict Res Ther 2012; 3(5): 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Thanos PK, Rivera SN, Weaver K, et al. Dopamine D2R DNA transfer in dopamine D2 receptor-deficient mice: effects on ethanol drinking. Life Sci 2005; 77(2): 130–9. 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Thanos PK, Michaelides M, Umegaki H, Volkow ND. D2R DNA transfer into the nucleus accumbens attenuates cocaine self-administration in rats. Synapse 2008; 62(7): 481–6. 10.1002/syn.20523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Blum K, Febo M, Badgaiyan RD. Fifty years in the development of a glutaminergic-dopaminergic optimization complex (KB220) to balance brain reward circuitry in reward deficiency syndrome: a pictorial. Austin Addict Sci 2016;1(2):1006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Febo M, Blum K, Badgaiyan RD, et al. Enhanced functional connectivity and volume between cognitive and reward centers of naïve rodent brain produced by pro-dopaminergic agent KB220Z. PLoS One. 2017April26;12(4):e0174774. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Blum K, Liu Y, Wang W, et al. rsfMRI effects of KB220Z™ on neural pathways in reward circuitry of abstinent genotyped heroin addicts. Postgrad Med 2015; 127(2): 232–41. 10.1080/00325481.2015.994879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Philip NS, Carpenter SL, Sweet LH. Developing neuroimaging phenotypes of the default mode network in PTSD: integrating the resting state, working memory, and structural connectivity. J Vis Exp 2014July1;(89):51651. 10.3791/51651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].O’Doherty DCM, Tickell A, Ryder W, et al. Frontal and subcortical grey matter reductions in PTSD. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 2017; 266: 1–9. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].O’Doherty DC, Chitty KM, Saddiqui S, Bennett MR, Lagopoulos J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging measurement of structural volumes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res 2015; 232(1): 1–33. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Logue MW, van Rooij SJH, Dennis EL, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: a multisite ENIGMA-PGC study: subcortical volumetry results from posttraumatic stress disorder consortia. Biol Psychiatry 2018; 83(3): 244–53. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Akiki TJ, Averill CL, Wrocklage KM, et al. The Association of PTSD Symptom Severity with Localized Hippocampus and Amygdala Abnormalities. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 2017; 1: 1. 10.1177/2470547017724069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Martindale SL, Rowland JA, Shura RD, Taber KH. Longitudinal changes in neuroimaging and neuropsychiatric status of post-deployment veterans: a CENC pilot study. Brain Inj 2018; 32(10): 1208–16. 10.1080/02699052.2018.1492741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Averill LA, Abdallah CG, Pietrzak RH, et al. Combat exposure severity is associated with reduced cortical thickness in combat veterans: a preliminary report. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 2017; 1: 1. 10.1177/2470547017724714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].van Wingen GA, Geuze E, Caan MW, et al. Persistent and reversible consequences of combat stress on the mesofrontal circuit and cognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109(38): 15508–13. 10.1073/pnas.1206330109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Butler O, Willmund G, Gleich T, Gallinat J, Kühn S, Zimmermann P. Hippocampal gray matter increases following multimodal psychological treatment for combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Brain Behav 2018; 8(5): e00956. 10.1002/brb3.956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Blum K, Gardner E, Oscar-Berman M, Gold M. “Liking” and “wanting” linked to Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS): hypothesizing differential responsivity in brain reward circuitry. Curr Pharm Des 2012; 18(1): 113–8. 10.2174/138161212798919110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Blum K, Giordano J, Oscar-Berman M, Bowirrat A, Simpatico T, Barh D. Diagnosis and healing in veterans suspected of suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (ptsd) using reward gene testing and reward circuitry natural dopaminergic activation. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther 2012; ; 3(3): 1000116. 10.4172/2157-7412.1000116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Filiano AJ, Gadani SP, Kipnis J. How and why do T cells and their derived cytokines affect the injured and healthy brain? Nat Rev Neurosci 2017; 18(6): 375–84. 10.1038/nrn.2017.39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Moalem G, Leibowitz-Amit R, Yoles E, Mor F, Cohen IR, Schwartz M. Autoimmune T cells protect neurons from secondary degeneration after central nervous system axotomy. Nat Med 1999; 5(1): 49–55. 10.1038/4734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kipnis J, Yoles E, Porat Z, et al. T cell immunity to copolymer 1 confers neuroprotection on the damaged optic nerve: possible therapy for optic neuropathies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97(13): 7446–51. 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kipnis J, Yoles E, Schori H, Hauben E, Shaked I, Schwartz M. Neuronal survival after CNS insult is determined by a genetically encoded autoimmune response. J Neurosci 2001; 21(13): 4564–71. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04564.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hauben E, Butovsky O, Nevo U, et al. Passive or active immunization with myelin basic protein promotes recovery from spinal cord contusion. J Neurosci 2000; 20(17): 6421–30. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06421.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yoles E, Hauben E, Palgi O, et al. Protective autoimmunity is a physiological response to CNS trauma. J Neurosci 2001; 21(11): 3740–8. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03740.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kipnis J, Cohen H, Cardon M, Ziv Y, Schwartz M. T cell deficiency leads to cognitive dysfunction: implications for therapeutic vaccination for schizophrenia and other psychiatric conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101(21): 8180–5. 10.1073/pnas.0402268101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Brynskikh A, Warren T, Zhu J, Kipnis J. Adaptive immunity affects learning behavior in mice. Brain Behav Immun 2008; 22(6): 861–9. 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Radjavi A, Smirnov I, Kipnis J. Brain antigen-reactive CD4+ T cells are sufficient to support learning behavior in mice with limited T cell repertoire. Brain Behav Immun 2014; 35: 58–63. 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Filiano AJ, Xu Y, Tustison NJ, et al. Unexpected role of interferon-γ in regulating neuronal connectivity and social behaviour. Nature 2016; 535(7612): 425–9. 10.1038/nature18626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Perez A, et al. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic-like behavior in mice. Genes Brain Behav 2004; 3(5): 287–302. 10.1111/j.1601-1848.2004.00076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cohen H, Ziv Y, Cardon M, et al. Maladaptation to mental stress mitigated by the adaptive immune system via depletion of naturally occurring regulatory CD4+CD25+ cells. J Neurobiol 2006; 66(6): 552–63. 10.1002/neu.20249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Rattazzi L, Piras G, Ono M, Deacon R, Pariante CM, D’Acquisto F. CD4⁺ but not CD8⁺ T cells revert the impaired emotional behavior of immuno-compromised RAG-1-deficient mice. Transl Psychiatry 2013; 3(7): e280. 10.1038/tp.2013.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Norris GT, Kipnis J. Immune cells and CNS physiology: microglia and beyond. J Exp Med 2019; 216(1): 60–70. 10.1084/jem.20180199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Louveau A, Herz J, Alme MN, et al. CNS lymphatic drainage and neuroinflammation are regulated by meningeal lymphatic vasculature. Nat Neurosci 2018; 21(10): 1380–91. 10.1038/s41593-018-0227-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Louveau A, Filiano AJ, Kipnis J. Meningeal whole mount preparation and characterization of neural cells by flow cytometry. Curr Protoc Immunol 2018; 121(1): e50. 10.1002/cpim.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Mrdjen D, Pavlovic A, Hartmann FJ, et al. High-dimensional single-cell mapping of central nervous system immune cells reveals distinct myeloid subsets in health, aging, and disease. Immunity 2018; 48(2): 380–395.e6. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hart BL. Biological basis of the behavior of sick animals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1988; 12(2): 123–37. 10.1016/S0149-7634(88)80004-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Starkman BG, Sakharkar AJ, Pandey SC. Epigenetics-beyond the genome in alcoholism. Alcohol Res 2012; 34(3): 293–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bos N, Lefèvre T, Jensen AB, d’Ettorre P. Sick ants become unsociable. J Evol Biol 2012; 25(2): 342–51. 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02425.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kazlauskas N, Klappenbach M, Depino AM, Locatelli FF. Sickness behavior in honey bees. Front Physiol 2016; 7: 261. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Blum K, Oscar-Berman M, Bowirrat A, et al. Neuropsychiatric genetics of happiness, friendships, and politics: hypothesizing homophily (“birds of a feather flock together”) as a function of reward gene polymorphisms. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther 2012; 3(112): 1000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Comings DE, Muhleman D, Gysin R. Dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) gene and susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder: a study and replication. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40(5): 368–72. 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00519-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Petrulli JR, Kalish B, Nabulsi NB, Huang Y, Hannestad J, Morris ED. Systemic inflammation enhances stimulant-induced striatal dopamine elevation. Transl Psychiatry 2017; 7(3): e1076. 10.1038/tp.2017.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Rossier J, French ED, Rivier C, Ling N, Guillemin R, Bloom FE. Foot-shock induced stress increases beta-endorphin levels in blood but not brain. Nature 1977; 270(5638): 618–20. 10.1038/270618a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Akil H, Young E, Watson SJ, Coy DH. Opiate binding properties of naturally occurring N- and C-terminus modified beta-endorphins. Peptides 1981; 2(3): 289–92. 10.1016/S0196-9781(81)80121-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Wybran J, Appelboom T, Famaey JP, Govaerts A. Suggestive evidence for receptors for morphine and methionine-enkephalin on normal human blood T lymphocytes. J Immunol 1979; 1233 : 1068–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Plotnikoff NP, Miller GC. Enkephalins as immunomodulators. Int J Immunopharmacol 1983; 5(5): 437–41. 10.1016/0192-0561(83)90020-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Gilman SC, Schwartz JM, Milner RJ, Bloom FE, Feldman JD. beta-Endorphin enhances lymphocyte proliferative responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1982; 79(13): 4226–30. 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].McCain HW, Lamster IB, Bilotta J. Modulation of human T-cell suppressor activity by beta endorphin and glycyl-L-glutamine. Int J Immunopharmacol 1986; 8(4): 443–6. 10.1016/0192-0561(86)90130-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Enkephalins Wybran J. and endorphins as modifiers of the immune system: present and future. Fed Proc 1985; 44(1 Pt 1): 92–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Johnson HM, Smith EM, Torres BA, Blalock JE. Regulation of the in vitro antibody response by neuroendocrine hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1982; 79(13): 4171–4. 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Smith R, Grossman A, Gaillard R, et al. Studies on circulating met-enkephalin and beta-endorphin: normal subjects and patients with renal and adrenal disease. Clin Endocrinol 1981; 15(3): 291–300. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1981.tb00668.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Vaswani KK, Richard CW III, Tejwani GA. Cold swim stress-induced changes in the levels of opioid peptides in the rat CNS and peripheral tissues. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1988; 29(1): 163–8. 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90290-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Smith EM, Morrill AC, Meyer WJ III, Blalock JE. Corticotropin releasing factor induction of leukocyte-derived immunoreactive ACTH and endorphins. Nature 1986; 321(6073): 881–2. 10.1038/321881a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Cheĭdo MA, Gevorgian MM. [Role of dopamine D1- and D2-receptors in the delta1-opioidergic immunostimulation]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk 2012; (5): 55–7. 10.15690/vramn.v67i5.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Cheĭdo MA, Idova GV. [Effect of opioid peptides on immunomodulation]. Ross Fiziol Zh Im I M Sechenova 1998; 84(4): 385–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Williamson SA, Knight RA, Lightman SL, Hobbs JR. Effects of beta endorphin on specific immune responses in man. Immunology 1988; 65(1): 47–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Ehrenpreis S D-phenylalanine and other enkephalinase inhibitors as pharmacological agents: implications for some important therapeutic application. Subst Alcohol Actions Misuse 1982; 3(4): 231–9. 10.3727/036012982816952099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Thanawala V, Kadam VJ, Ghosh R. Enkephalinase inhibitors: potential agents for the management of pain. Curr Drug Targets 2008; 9(10): 887–94. 10.2174/138945008785909356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Ehrenpreis S D-phenylalanine and other enkephalinase inhibitors as pharmacological agents: implications for some important therapeutic application. Acupunct Electrother Res 1982; 7(2–3): 157–72. 10.3727/036012982816952099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Nagarjun S, Dhadde SB, Veerapur VP, Thippeswamy BS, Chandakavathe BN. Ameliorative effect of chromium-d-phenylalanine complex on indomethacin-induced inflammatory bowel disease in rats. Biomed Pharmacother 2017; 89: 1061–6. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Febo M, Blum K, Badgaiyan RD, et al. Enhanced functional connectivity and volume between cognitive and reward centers of naïve rodent brain produced by pro-dopaminergic agent KB220Z. PLoS One 2017; 12(4): e0174774. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Noble EP, Blum K, Ritchie T, Montgomery A, Sheridan PJ. Allelic association of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with receptor-binding characteristics in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48(7): 648–54. 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310066012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Payer D, Williams B, Mansouri E, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and dopamine release in healthy individuals. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017; 76: 192–6. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Cabib S, Puglisi-Allegra S. The mesoaccumbens dopamine in coping with stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2012; 36(1): 79–89. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Pan WH, Yang SY, Lin SK. Neurochemical interaction between dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex. Synapse 2004; 53(1): 44–52. 10.1002/syn.20034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Roy-Byrne P, Arguelles L, Vitek ME, et al. Persistence and change of PTSD symptomatology-a longitudinal co-twin control analysis of the Vietnam Era Twin Registry. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004; 39(9): 681–5. 10.1007/s00127-004-0810-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Cabana-Domínguez J, Shivalikanjli A, Fernàndez-Castillo N, Cormand B. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of cocaine dependence: Shared genetics with comorbid conditions. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2019; 94: 109667. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Szutorisz H, DiNieri JA, Sweet E, et al. Parental THC exposure leads to compulsive heroin-seeking and altered striatal synaptic plasticity in the subsequent generation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014; 39(6): 1315–23. 10.1038/npp.2013.352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Auxéméry Y [Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a consequence of the interaction between an individual genetic susceptibility, a traumatogenic event and a social context]. Encephale 2012; 38(5): 373–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Zhang K, Wang L, Cao C, et al. A DRD2/ANNK1-COMT interaction, consisting of functional variants, confers risk of post-traumatic stress disorder in traumatized chinese. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: 170. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Brown LA, Gallagher T, Petersen J, Benhamou K, Foa EB, Asnaani A. Does CBT for anxiety-related disorders alter suicidal ideation? Findings from a naturalistic sample. J Anxiety Disord 2018; 59: 10–6. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Wildlife USF. FWS Critical Incident Stress Management Handbook. United States: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [92].Smith BH, Higgins C, Baldacchino A, Kidd B, Bannister J. Substance misuse of gabapentin. J Royal College Gen Prac 2012; 62(601): 406–7. 10.3399/bjgp12X653516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].McLaughlin T, Blum K, Oscar-Berman M, et al. Putative dopamine agonist (KB220Z) attenuates lucid nightmares in PTSD patients: role of enhanced brain reward functional connectivity and homeostasis redeeming joy. J Behav Addict 2015; 4(2): 106–15. 10.1556/2006.4.2015.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].McLaughlin T, Blum K, Oscar-Berman M, et al. Using the Neuroadaptagen KB200z™ to ameliorate terrifying, lucid nightmares in RDS patients: the role of enhanced, brain-reward, functional connectivity and dopaminergic homeostasis. J Reward Defic Syndr 2015; 1(1): 24–35. 10.17756/jrds.2015-006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].McLaughlin T, Febo M, Badgaiyan RD, et al. KB220Z™ a pro-dopamine regulator associated with the protracted, alleviation of terrifying lucid dreams. can we infer neuroplasticity-induced changes in the reward circuit? J Reward Defic Syndr Addict Sci 2016; 2(1): 3–13. 10.17756/jrdsas.2016-022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Maxwell J, Ethical, legal, social, and policy issues in the use of genomic technology by the US military. J Biosci 2014; 1(3): 244–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Evans NG, Moreno JD. Yesterday’s war; tomorrow’s technology: peer commentary on ‘Ethical, legal, social and policy issues in the use of genomic technologies by the US military’. J Law Biosci 2014; 2(1): 79–84. 10.1093/jlb/lsu030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Savulescu J Science wars-How much risk should soldiers be exposed to in military experimentation? J Law Biosci 2015; 2(1): 99–104. 10.1093/jlb/lsv006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Baumann TK. Proxy consent and a national DNA databank: an unethical and discriminatory combination. Iowa Law Rev 2001; 86(2): 667–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Pereira S, Hsu RL, Islam R, et al. MilSeq Project. Airmen and health-care providers’ attitudes toward the use of genomic sequencing in the US Air Force: findings from the MilSeq Project. Genet Med 2020; 22(12): 2003–10. 10.1038/s41436-020-0928-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Blum K, Gondré-Lewis MC, Baron D, et al. Introducing precision addiction management of reward deficiency syndrome, the construct that underpins all addictive behaviors. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: 548. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Thanos PK, Hamilton J, O’Rourke JR, et al. Dopamine D2 gene expression interacts with environmental enrichment to impact lifespan and behavior. Oncotarget 2016; 7(15): 19111–23. 10.18632/oncotarget.8088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Blum K, Chen TJ, Morse S, et al. Overcoming qEEG abnormalities and reward gene deficits during protracted abstinence in male psychostimulant and polydrug abusers utilizing putative dopamine D2 agonist therapy: part 2. Postgrad Med 2010; 122(6): 214–26. 10.3810/pgm.2010.11.2237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Kjaer TW, Bertelsen C, Piccini P, Brooks D, Alving J, Lou HC. Increased dopamine tone during meditation-induced change of consciousness. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 2002; 13(2): 255–9. 10.1016/S0926-6410(01)00106-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Borsook D, Linnman C, Faria V, Strassman AM, Becerra L, Elman I. Reward deficiency and anti-reward in pain chronification. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016; 68: 282–97. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]