Abstract

Introduction

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a common disease worldwide, and imposes a substantial burden to the healthcare system. In CHF, limited exercise capacity and affected mental well-being leads to a reduced quality of life (QOL). How to improve the QOL and exercise endurance is critical for patients with CHF. Exercise therapy, such as some traditional Asian exercises (TAEs) including Taichi, Baduanjin and Yoga, plays an important role in the rehabilitation of patients with CHF. TAE is suitable for the rehabilitation of patients with CHF because of its soft movements and can relax the body and mind. Studies have shown that TAE can regulate the overall health status of the body and exercise tolerance, improve QOL and reduce rehospitalisation rate in patients with CHF. However, the difference in efficacy of TAE in patients with CHF is not yet clear. The main purpose of this study is to conduct a network meta-analysis (NMA) of randomised trials to determine the impact of TAE on patients with CHF of different types, different causes and different New York Heart Association (NYHA) heart function classifications and to provide references for different types of patients with CHF to choose appropriate exercise rehabilitation therapy.

Methods and analysis

The literature search will be retrieved from PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang database, Chinese biomedical literature service system (SinoMed) and Chinese Scientific Journals Database (VIP) from the date of their inception until 1 August 2021. All randomised controlled trials that evaluated the effects of three different TAE therapies (Taichi, Baduanjin and Yoga) on patients with CHF will be included. The primary outcomes are peak oxygen uptake (peak VO2), exercise capacity (6-min walking distance) and QOL tested with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire. Secondary outcomes include the levels of N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure. For included articles, two reviewers will independently extract the data, and Cochrane Collaboration’s tool will be used to assess risk of bias. We will perform the Bayesian NMA to pool all treatment effects. The ranking probabilities for the optimal intervention of various treatments (Taichi, Baduanjin or Yoga) will be estimated by the mean ranks and surface under the cumulative ranking curve. Subgroup analysis for different types, different causes and different NYHA heart function classifications of CHF will be performed. We will use the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation system to assess the quality of evidence contributing to each network estimate.

Ethics and dissemination

The results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications. They will provide useful information to inform clinicians on the potential functions of TAE in CHF, and to provide consolidated evidence for clinical practice and further research of TAE.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020179304.

Keywords: rehabilitation medicine, heart failure, complementary medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

As far as we know, this will be the first network meta-analysis (NMA) to compare the various forms of traditional Asian exercise (TAE).

This is the first study to use NMA to evaluate the effectiveness and differences of TAE (Taichi, Baduanjin and Yoga) in patients with chronic heart failure.

Due to well established eligible criteria, rigorous data collection and quality assessment, standardised statistical analysis, subgroup and sensitivity analyses, study strength may be increased and heterogeneity may be reduced.

The drawbacks of this study may potentially reside in the changes in the frequency and duration of treatment, which may be result in methodological heterogeneity.

Background

Chronic heart failure (CHF) refers to a condition that the heart is unable to pump sufficient blood to maintain the body’s needs, and is always caused by various cardiopulmonary diseases.1 CHF is usually associated with high cost and significant morbidity and mortality. Approximately 50% of the individuals diagnosed with heart failure (HF) will die within 5 years and the high cost of HF-related hospitalisation is about US$23 077 per patient in the USA.2 3 In CHF, limited exercise capacity and affected mental well-being leads to a markedly reduced quality of life (QOL).4 But progress on new drugs of CHF has been minimal. How to improve the QOL and exercise endurance is critical for patients with CHF. More and more regions focus on the prevention and treatment of HF by means of exercise and mental regulation so that patients with CHF can have a longer survival time or a higher QOL.5

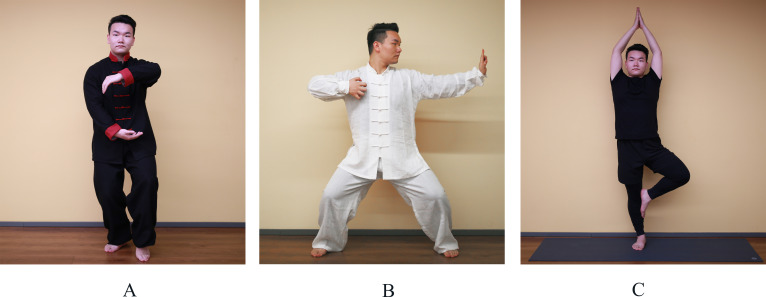

Traditional Asian exercise (TAE, including Taichi, Baduanjin and Yoga) (figure 1), plays an important role in the rehabilitation of patients with CHF and is suitable for the rehabilitation of patients with CHF because of its soft movements and mind relaxation. TAE has been widely used in China for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and gained popularity in Western countries as an alternative form of exercise. Many studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of exercise rehabilitation for CHF, which can reduce mortality and hospitalisation rates in patients with CHF, and improve exercise tolerance and QOL in patients.6–8 Taichi emphasises on guiding the body movement following people’s thoughts. These movements are considered to be low risk interventions and studies have found positive effects of TAE on exercise load and QOL in patients with CHF.9 10 Long-term practice of Taichi can relax the whole body and fully exercise the bones and muscles. Taichi exercise may benefit patients at all stages of HF, by enhancing QOL and exercise capacity and reducing depressive symptoms.11 12 Baduanjin is composed of eight different basic movements, which are soft and slow, smooth and coherent and suitable for patients with HF. Yoga combines body movement, breathing and mind control and proves to improve the QOL in patients with HF and increase exercise capacity (peak oxygen uptake (peak VO2)).9 13 Many published systematic reviews have focused on specific forms of TAE, such as Taichi or Baduanjin.7 10

Figure 1.

Presentation of three traditional Asian exercise (A) Taichi, (B) Baduanjin and (C) Yoga. The pictured individual has agreed to publish his image.

Exercise intensity is closely related to the pumping ability of the heart, endothelial system and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle, which is the cause for influencing peak VO2.14 Taichi and Baduanjin can be classified as a mild-to-moderate form of exercise intensity, while Yoga as moderate form of exercise intensity.15 16 Moreover, participants of Yoga may only perform breathing exercises or meditate at the same time. This is different from Taichi and Baduanjin, which emphasis on the coordination of breathing and exercise. Recently, a large cohort studies showed that a strong and dose-dependent association of physical activity with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) but not with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).17 Further consider the diversity of the aetiology of HFrEF and HFpEF. Therefore, TAE may have different effects on different types, different causes and different New York Heart Association (NYHA) heart function classifications of CHF.

The main purpose of this study is to conduct a network meta-analysis (NMA) of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to determine the effect of TAE on patients with CHF of different types, different causes and different NYHA heart function classifications and to provide references for different types of patients with CHF to choose appropriate exercise rehabilitation therapy.

Methods and analysis

Design

This study will be reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines (online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2021-048891supp001.pdf (95.8KB, pdf)

Study type

All RCTs that evaluated the effects of three different TAE therapies (Taichi, Baduanjin and Yoga) on patients with CHF will be included. For cross-over studies and cluster randomised trials, we will include only the first-phase treatment. Non-RCTs, duplicate reports, pilot studies and studies lacking primary outcome data will be excluded.

Participants

We will include adults (age ≥18 years) with stable CHF (NYHA class I-III) based on WHO’s diagnosis of CHF. HFrEF (left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <40%), HF with mid-range ejection fraction (40%≤LVEF≤49%) and HFpEF (LVEF≥50%) will be included. There are no limitations on the participant’s characteristics (such as sex, comorbidity and treatment course). Patients will be excluded as follows: HF caused by congenital heart disease, unstable structural valvular diseases, dilated cardiomyopathy and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; patients with unstable vital signs: resting heart rate >100 beats/min and blood pressure >180/110 mm Hg or <90/60 mm Hg.

Intervention/control

Studies reporting TAE: Taichi, Baduanjin and Yoga, any form of exercise such as ‘simplified 24 forms’, with or without education or usual care, understood as repeated bouts of exercise over time involving more than 4 weeks at least will be included. For comparisons, both active (eg, aerobic exercise, endurance training (cycling and walking) or non-active (eg, usual care, pharmacological therapy, dietary, exercise counselling, education sessions and psychosocial interventions) controls compared with TAE will be eligible for included. We will also obtain informations from placebo controlled trials.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Peak VO2.

Exercise capacity tested by 6-minute walking distance.

QOL tested with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire.

Secondary outcomes

Levels of N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide.

LVEF.

Systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure.

Search strategy

The literature search will be retrieved from PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang database, Chinese biomedical literature service system (SinoMed) and Chinese Scientific Journals Database (VIP) from the inception to 1 August 2021.

The following search terms will be included in the search strategy: (tai chi OR taiji or taiqi OR tai ji quan OR tai chi chuan OR taichi qigong OR shadowboxing OR baduanjin OR Baduanjin exercise OR eight section brocades OR yoga OR yogic OR asana or pranayama OR dhyana) AND (chronic heart failure OR heart failure with reduced ejection fraction OR heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction OR heart failure with preserved ejection fraction OR cardiac failure OR heart failure OR heart decompensation OR right-sided heart failure OR myocardial failure OR congestive heart failure OR left sided heart failure OR ventricular failure). The search strategy for PubMed is shown in table 1 and online supplemental file 2. Previous reviews, meta-analyses and relevant references cited in the selected studies will be screened. We will conduct a search of the following trial registers for ongoing or unpublished trials: Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, ClinicalTrials.gov, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO-ICTRP). For unpublished or incomplete data, we will contact the original authors to supplement data. The search strategy will be independently conducted by four reviewers (JX, JL, ZZ and KZ), and disagreements will be discussed and solved by consensus or involving a third member of the review team (QL).

Table 1.

Search strategy for the PubMed database

| Number | Search terms |

| 1 | tai chi |

| 2 | taiji |

| 3 | taiqi |

| 4 | tai ji quan |

| 5 | tai chi chuan |

| 6 | taichi qigong |

| 7 | shadowboxing |

| 8 | baduanjin |

| 9 | Baduanjin exercise |

| 10 | eight section brocades |

| 11 | yoga |

| 12 | yogic |

| 13 | asana |

| 14 | pranayama |

| 15 | dhyana |

| 16 | OR 1–15 |

| 17 | chronic heart failure |

| 18 | heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| 19 | heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction |

| 20 | heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| 21 | cardiac failure |

| 22 | heart failure |

| 23 | heart decompensation |

| 24 | right-sided heart failure |

| 25 | myocardial failure |

| 26 | congestive heart failure |

| 27 | left sided heart failure |

| 28 | ventricular failure |

| 29 | OR 17–28 |

| 30 | 16 and 29 |

bmjopen-2021-048891supp002.pdf (23.5KB, pdf)

Study selection

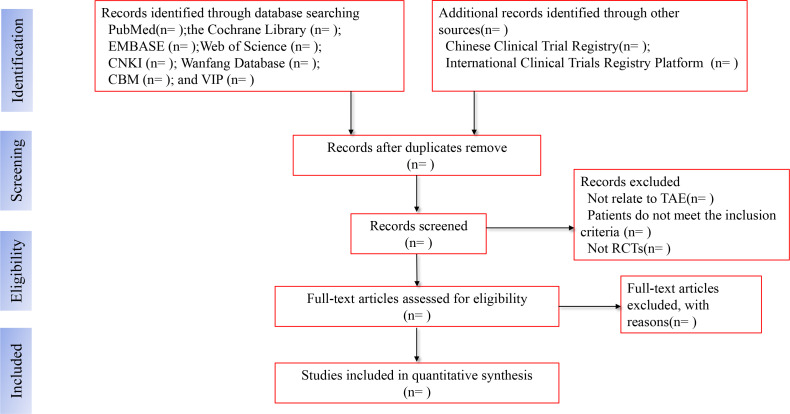

EndNote V.X8 will be used to manage literatures and exclude duplicate records. Three reviewers (RF, TM and XJ) will screen the titles and abstracts of all the retrieved articles and remove those failing to meet the eligible criteria independently. They will then get the full texts for potentially eligible studies to further determine whether they fulfil the same eligible criteria. Any disagreements will be resolved by a third review author (JL) for arbitration. The selection process will be described in a PRISMA flow chart (http://www.prisma-statement.org) (figure 2).18

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the study selection process. RCTs, randomised controlled trials; TAE, traditional Asian exercise.

Data extraction

We will design a data extraction form from a random sample of three studies to ensure consistency and reduce bias and improve validity and reliability during reviewing. Then modify the form based on the problems in the pilot stage. Four review authors (JX, YL, CH and JJ) will independently extract study characteristics and outcome data from the included studies. Two reviewers (YL and ZZ) will recheck that the data are entered correctly into the final data set. Any disagreements will be resolved by discussion with the whole team or by involving a third review author (KZ).

The following items will be extracted:

Study characteristics: lead author, publication year and journal.

Methods: study design, duration of study, details of trial design (ie, randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding).

Participants: sample size, number randomised, number of losing follow-up visits/withdrawing from studies, diagnostic criteria of CHF, mean age, age range, sex, design setting, country, course of treatment and severity of CHF, comorbidities and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Intervention: intervened measures (type of exercise, length, frequency, number of sessions and duration of each session), cointerventions, studies with education components and comparators (both active (eg, aerobic exercise, endurance training (cycling and walking)) or non-active (eg, usual care, pharmacological therapy, dietary, exercise counselling and psychosocial interventions)).

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, time points reported, mean value and mean difference.

Miscellaneous: funding source and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors, register ID.

Dealing with missing data

We will initially contact authors through email or telephone to obtain any missing data. If we are unable to obtain the data, we will analyses the available data and assess the potential impact of missing data on the study results in the discussion section.

Risk of bias assessment

Three reviewers (JL, XJ and JW) will assess risk of bias in the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool.19 We will resolve any disagreements by discussion or another review author. The risk of bias in the following domains will be evaluated: randomisation process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome selection of the reported result and overall risk.

Statistical synthesis of study data

Methods for direct treatment comparisons

We will use DerSimonian-Laird random effects model to perform standard pairwise meta-analysis. Dichotomous outcomes will be calculated as OR and continuous data as standardised mean difference (SMD), both with corresponding 95% CIs. Study heterogeneity will be assessed by Cochran Q test and presented as the I2 statistic. Sensitivity analysis of pairwise meta-analysis will be conducted to validate the robustness of the results.

Methods for indirect and mixed comparisons

A random-effects NMA will be conducted within a Bayesian framework.20 We will use the Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm by applying WinBUGS V.1.4.3. OR, SMD or weighted mean difference will be calculated with 95% CIs. We will obtain a comprehensive ranking of all treatments. The surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) and the mean ranks will be used for the treatment hierarchy. We will describe SUCRA with percentages.

Examination of assumptions in NMA (consistency, transitivity and heterogeneity)

We will use local method, global method and node-splitting methods to evaluate consistency. Local method evaluates inconsistency in each closed loop using a loop-specific approach. Global method compares the difference between consistency and inconsistency models based on a χ2 test using a design-by-treatment approach.21 The node-splitting method will be used to assesses the inconsistency of the model by separating evidence of one particular comparison into direct and indirect evidence. To assess global heterogeneity in the network, we will calculate the I² and generate predictive interval plot.22 Transitivity, a key underlying assumption of NMA, will be evaluated by comparing the distribution of clinical and methodological variables that can act as effect modifiers across treatment comparisons.

All analyses will be performed using R V.3.5.0 (gemtc package, NMA, assessment of global heterogeneity, network meta regression and SUCRA graphs), and Stata V.13.0 (pairwise meta-analysis, estimation of inconsistency, transitivity and local heterogeneity, funnel plot).

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis

To assess whether the results were influenced by study characteristics (effect modifiers), subgroup analysis for primary outcome will be conducted based on age group, treatment duration, years of CHF, sample size, quality of study, comorbidity and sponsorship. Subgroup analysis for different types, different causes and different NYHA heart function classifications of CHF will also be performed. Inconsistent sources will be explored by performing univariate and multivariate meta-regressions, a network meta-regression. We will conduct sensitivity analysis to exclude trials with small sample sizes (ie, arms of less than 10 patients) and remove trails that report the generation of non-random sequences. All of these analyses were performed in Stata V.13.0. If data extraction is insufficient, a qualitative synthesis will be created.

Publication bias

Publication bias will be assessed by performing Egger’s regression test. Additionally, a comparison-adjusted funnel plot will be used to investigate whether results in imprecise trials differ from those in more precise ones.

Quality of evidence

Two reviewers (CH and ZZ) will use the GRADE (The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) framework to assess the certainty of evidence contributing to each network estimate. The study limitations, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness and publication bias will be investigated. Four levels of quality of evidence will be used: high, moderate, low or very low.

Timelines

The study will be conducted from 1 January 2021 to 31 December 2021.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Discussion

CHF is considered to be the end stage of heart disease manifested with reduced exercise ability and poor QOL. Exercise training is widely regarded as a non-drug intervention to improve patient’s exercise tolerance and QOL. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is safe and effective for CHF. Previous studies have shown that Taichi, Baduanjin and Yoga are beneficial for CHF. Taichi improves body functions,23 such as lowering blood pressure in adults with hypertension,24 25 enhancing aerobic endurance,26 27 reducing stress, anxiety and depression and ameliorating QOL.28 29 Baduanjin can reduce the load of the heart, increase the body’s ability to transport and use oxygen in blood circulation,30 31 and thus improving HF. Yoga can improve peak VO2 in patients with CHF, which is considered as another method of exercise training for patients with CHF.9

Therefore, Taichi, Baduanjin and Yoga are effective exercise ways to treat CHF, however, the difference in efficacy of TAE in patients with CHF is not yet clear. We attempt to conduct an NMA of a sufficient number of RCTs to determine the impact of TAE on patients with CHF of different types, different causes and different NYHA heart function classifications and to provide stronger evidence to help patients with CHF choose more appropriate exercise rehabilitation therapy. To our knowledge, this review will be the first to assess the impact of TAE on patients with CHF, and we hope that the results of this study can provide help for the rehabilitation of patients with CHF.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol is in accordance with the PRISMA statement, and has been registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews.

As no individual patient data will be used in this NMA, ethical approval is not required. We aim to publish this NMA in a peer-reviewed journal. The results of this NMA will provide a more comprehensive and more reliable information about the effect of TAE for patients with CHF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge CH and JJ for taking the photo.

Footnotes

JX, ZZ, JL and YL contributed equally.

Contributors: QL, KZ, JX, ZZ, JL and YL conceived and designed the study. JX and ZZ drafted this protocol. JL, YL, LT and ZZ revised it. JW, RF, TM, CH, ZZ, JJ and XJ developed the search strategies and conducted data collection. All authors have read this manuscript and approved the publication of this protocol. JX, ZZ, JL and YL contributed equally to this work and should be considered joint first authors. Both QL and KZ are corresponding authors.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China. (No. 81903993 and No. 81973622).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:891–975. 10.1002/ejhf.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;131:e29–322. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang G, Zhang Z, Ayala C, et al. Costs of heart failure-related hospitalizations in patients aged 18 to 64 years. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:769–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleg JL, Cooper LS, Borlaug BA, et al. Exercise training as therapy for heart failure: current status and future directions. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:209–20. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.001420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal M, Bozkurt B, Panjrath G, et al. Lifestyle Modifications for Preventing and Treating Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2391–405. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor-Piliae R, Finley BA. Benefits of tai chi exercise among adults with chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020;35:423–34. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X, Marrone G, Olson TP, et al. Intensity level and cardiorespiratory responses to Baduanjin exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2020 10.1002/ehf2.12959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pullen PR, Nagamia SH, Mehta PK, et al. Effects of yoga on inflammation and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 2008;14:407–13. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomes-Neto M, Rodrigues ES, Silva WM, et al. Effects of yoga in patients with chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis. Arq Bras Cardiol 2014;103:433–9. 10.5935/abc.20140149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Savarese G, Cai Y, et al. Tai chi and Qigong practices for chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020;2020:1–15. 10.1155/2020/2034625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeh GY, Wood MJ, Lorell BH, et al. Effects of tai chi mind-body movement therapy on functional status and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med 2004;117:541–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huston P, McFarlane B. Health benefits of tai chi: what is the evidence? Can Fam Physician 2016;62:881–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hägglund E, Hagerman I, Dencker K, et al. Effects of yoga versus hydrotherapy training on health-related quality of life and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2017;16:381–9. 10.1177/1474515117690297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wisløff U, Støylen A, Loennechen JP, et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation 2007;115:3086–94. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and Met values. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1575–81. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun X-G. Rehabilitation practice patterns for patients with heart failure: the Asian perspective. Heart Fail Clin 2015;11:95–104. 10.1016/j.hfc.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandey A, LaMonte M, Klein L, et al. Relationship between physical activity, body mass index, and risk of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1129–42. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;350:g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, eds. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews ofInterventions. 2nd edn. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2019: 205–28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salanti G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:80–97. 10.1002/jrsm.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Jackson D, Barrett JK, et al. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: concepts and models for multi-arm studies. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:98–110. 10.1002/jrsm.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaimani A, Salanti G. Visualizing assumptions and results in network meta-analysis: the network graphs package. Stata J 2015;15:905–50. 10.1177/1536867X1501500402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wayne PM, Berkowitz DL, Litrownik DE, et al. What do we really know about the safety of tai chi?: a systematic review of adverse event reports in randomized trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:2470–83. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan AWK, Chair SY, Lee DTF, et al. Tai chi exercise is more effective than brisk walking in reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors among adults with hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;88:44–52. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun J, Buys N. Community-based mind-body meditative tai chi program and its effects on improvement of blood pressure, weight, renal function, serum lipoprotein, and quality of life in Chinese adults with hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:1076–81. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng G, Li S, Huang M, et al. The effect of tai chi training on cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117360. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu W, Liu X, Wang L, et al. Effects of tai chi on exercise capacity and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:1253–63. 10.2147/COPD.S70862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu T, Chan AW, Liu YH, et al. Effects of tai Chi-based cardiac rehabilitation on aerobic endurance, psychosocial well-being, and cardiovascular risk reduction among patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2018;17:368–83. 10.1177/1474515117749592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C, Bannuru R, Ramel J, et al. Tai chi on psychological well-being: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2010;10:23. 10.1186/1472-6882-10-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen M-G, Liang X, Kong L, et al. Effect of Baduanjin sequential therapy on the quality of life and cardiac function in patients with AMI after PCI: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020;2020:8171549. 10.1155/2020/8171549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The influence of baduanjin on cardiopulmonary function during cardiac rehabilitation for CHD patients. Med & Pharm J Chin PLA 2017;29:24–7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-048891supp001.pdf (95.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-048891supp002.pdf (23.5KB, pdf)