Abstract

Background

Antiepileptic drugs have been used in pain management since the 1960s; some seem to be especially useful for neuropathic pain. Lacosamide is an antiepileptic drug that has recently been investigated for neuropathic pain relief, although it failed to get approval for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy from either the Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency.

Objectives

To evaluate the analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of lacosamide in the management of chronic neuropathic pain or fibromyalgia.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register (2011, Issue 4), CENTRAL (2011, Issue 3), MEDLINE (January 2000 to August 2011) and EMBASE (2000 to August 2011) without language restriction, together with reference lists of retrieved papers and reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomised, double‐blind studies of eight weeks duration or longer, comparing lacosamide with placebo or another active treatment in chronic neuropathic pain or fibromyalgia.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data for efficacy and adverse events and examined issues of study quality, including risk of bias assessments. Where possible, we calculated numbers needed to treat to benefit from dichotomous data for effectiveness, adverse events and study withdrawals.

Main results

We included six studies; five (1863 participants) in painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN) and one (159 participants) in fibromyalgia. All were placebo‐controlled and titrated to a target dose of 200 mg, 400 mg or 600 mg lacosamide daily, given as a divided dose. Study reporting quality was generally good, although the imputation method of last observation carried forward used in analyses of the primary outcomes is known to known to impart major bias where, as here, adverse event withdrawal rates were high. This, together with small numbers of patients and events for most outcomes at most doses meant that most results were of low quality, with moderate quality evidence available for some efficacy outcomes for 400 mg lacosamide.

There were too few data for analysis of the 200 mg dose for painful diabetic neuropathy or any dose for fibromyalgia.

In painful diabetic neuropathy, lacosamide 400 mg provided statistically increased rates of achievement of "moderate" and "substantial" benefit (at least 30% and at least 50% reduction from baseline in patient‐reported pain respectively) and the patient global impression of change outcome of "much or very much improved". In each case the extra proportion benefiting above placebo was about 10%, yielding numbers needed to treat to benefit compared with placebo of 10 to 12. For lacosamide 600 mg there was no consistent benefit over placebo.

There was no significant difference between any dose of lacosamide and placebo for participants experiencing any adverse event or a serious adverse event, but adverse event withdrawals showed a significant dose response. The number needed to treat to harm for adverse event withdrawal was 11 for lacosamide 400 mg and 4 for the 600 mg dose.

Authors' conclusions

Lacosamide has limited efficacy in the treatment of peripheral diabetic neuropathy. Higher doses did not give consistently better efficacy, but were associated with significantly more adverse event withdrawals. Where adverse event withdrawals are high with active treatment compared with placebo and when last observation carried forward imputation is used, as in some of these studies, significant overestimation of treatment efficacy can result. It is likely, therefore, that lacosamide is without any useful benefit in treating neuropathic pain; any positive interpretation of the evidence should be made with caution if at all.

Plain language summary

Lacosamide for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults

Antiepileptic drugs like lacosamide are commonly used for treating neuropathic pain, usually defined as pain due to damage to nerves. This would include postherpetic neuralgia (persistent pain experienced in an area previously affected by shingles), painful diabetic neuropathy, nerve injury pain, phantom limb pain and trigeminal neuralgia; fibromyalgia also responds to some antiepileptic drugs. This type of pain can be severe and long‐lasting, is associated with lack of sleep, fatigue, depression and a reduced quality of life. This review included five studies in painful diabetic neuropathy (1863 participants) and one in fibromyalgia (159 participants). In people with painful diabetic neuropathy, lacosamide had only a modest effect, with a specific effect due to its use in 1 person in 10. This is a minor effect and may be an over‐estimate due to use of the last observation carried forward method for analysis. There was insufficient information in fibromyalgia to draw any conclusions about the effect of lacosamide. There was no significant difference between lacosamide and placebo for participants with any, or a serious, adverse event, but there were significantly more adverse event withdrawals with lacosamide. Regulatory authorities have not licensed lacosamide for treating pain based on evidence presently available.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Lacosamide 400 mg compared with placebo for painful diabetic neuropathy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: painful diabetic neuropathy Settings: community Intervention: oral lacosamide 400 mg daily Comparison: oral placebo | ||||||

| Outcome | Probable outcome with intervention | Probable outcome with comparator | NNTB or NNTH and/or relative effect | No of participants and events | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| "Substantial" benefit At least 50% reduction in pain or equivalent |

350 in 1000 | 250 in 1000 | 10 (5.2 to 120) 1.4 (1.01 to 1.9) |

412 participants 142 events |

Low quality | LOCF imputation makes this likely to be an overestimate |

| "Moderate" benefit At least 30% reduction in pain |

540 in 1000 | 440 in 1000 | 9.8 (5.7 to 36) 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) |

715 participants 359 events |

Low quality | LOCF imputation makes this likely to be an overestimate |

| Proportion below 30/100 mm on VAS | No data | |||||

| Patient global impression much or very much improved | 330 in 1000 | 240 in 1000 | 12 (6.6 to 52) 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) |

715 participants 209 events |

Moderate quality | Low number of events, but not LOCF imputation |

| Quality of life measure | No data | |||||

| Adverse event withdrawals | 180 in 1000 | 91 in 1000 | 11 (7.5 to 22) 2.01 (1.4 to 2.9) |

874 participants 125 events |

Moderate quality | Low number of events |

| Serious adverse events | 66 in 1000 | 63 in 1000 | Not calculated 1.0 (0.7 to 1.6) |

1304 participants 85 events |

Moderate quality | Low number of events |

| Death | There were no deaths with lacosamide 400 mg or placebo | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

NNTB: number needed to treat to benefit; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; VAS: visual analogue scale; LOCF: last observation carried forward.

Background

Description of the condition

Neuropathic pain, unlike nociceptive pain such as gout and other forms of arthritis, is caused by nerve damage, often accompanied by changes in the central nervous system (CNS). The new (2011) definition of neuropathic pain is "pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system" (Jensen 2011). Fibromyalgia is a complex pain syndrome, defined as widespread pain for longer than three months with pain on palpation at 11 or more of 18 specified tender points (Wolfe 1990) and frequently associated with other symptoms such as poor sleep, fatigue and depression. More recently, a definition of fibromyalgia has been proposed based on symptom severity and the presence of widespread pain (Wolfe 2010). The cause or causes of fibromyalgia are not well understood but it has features in common with neuropathic pain, including changes in the CNS (Robinson 2011). Many people with both these conditions are significantly disabled with moderate or severe pain for many years. Conventional analgesics are usually not effective, although opioids may be in some individuals. Others may derive some benefit from a topical lidocaine patch or topical capsaicin. Treatment is more usually by unconventional analgesics such as antidepressants or antiepileptics.

Data for the incidence of neuropathic pain are difficult to obtain, but a systematic review of prevalence and incidence in the Oxford Region of the UK indicates prevalence rates per 100,000 of 34 for postherpetic neuralgia, 400 for diabetic neuropathy and trigeminal neuropathy and 2000 for fibromyalgia (McQuay 2007). Different estimates in the UK indicate incidences per 100,000 person years observation of 40 (95% confidence interval (CI) 39 to 41) for postherpetic neuralgia, 27 (95% CI 26 to 27) for trigeminal neuralgia, 1 (95% CI 1 to 2) for phantom limb pain and 15 (95% CI 15 to 16) for painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN), with rates decreasing in recent years for phantom limb pain and postherpetic neuralgia and increasing for PDN (Hall 2006; Hall 2008). The prevalence of neuropathic pain in Austria was reported as being 3.3% (Gustorff 2008), 6.9% in France (Bouhassira 2008) and in the UK as high as 8% (Torrance 2006).

Neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia are commonly difficult to treat effectively, with only a minority of individuals experiencing a clinically relevant benefit from any one intervention. A multidisciplinary approach is now advocated, with physical or cognitive therapies or both being combined with pharmacological interventions.

Description of the intervention

Lacosamide was developed as an antiepileptic drug and has been licensed in the USA and European Union for treatment of partial onset seizures. Lacosamide is also being investigated for treatment of neuropathic pain, based on experimental data from animal models (Beyreuther 2006) and other basic research and clinical evidence (Beyreuther 2007; Dworkin 2010; Harris 2009), but lacosamide was not approved for the treatment of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy by either the Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency.

Lacosamide was formerly known as erlosamide and it is marketed under the trade name Vimpat®.

How the intervention might work

Lacosamide is described as a functionalized amino acid molecule that selectively enhances the slow inactivation of voltage‐gated sodium channels and interacts with the collapsin‐response mediator protein‐2 (Beydoun 2009; Errington 2008). Voltage‐gated sodium channels play an important role in the excitability of nociceptors. In contrast to lidocaine and carbamazepine, lacosamide does not alter steady‐state fast inactivation, suggesting that it might be more effective than these other drugs at blocking the electrical activity of neurons that are chronically depolarised compared with those at more normal resting potentials (Sheets 2008).

Many antiepileptic drugs typically have efficacy in neuropathic pain, examples being gabapentin (Moore 2011a), pregabalin (Moore 2009b) and carbamazepine (Wiffen 2011a). Others, such as lamotrigine, do not (Wiffen 2011b).

Why it is important to do this review

Lacosamide is relatively new and is not an established pharmacological intervention for chronic neuropathic pain. Earlier Cochrane reviews of antiepileptics for neuropathic pain did not mention it (Wiffen 2005, original review 2000), but a number of clinical trials have now been completed, so it is important to review them and establish whether lacosamide has a place in the treatment of neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. The antiepileptic review has subsequently been split into reviews for individual drugs and some individual reviews have been published, for carbamazepine (Wiffen 2011a), lamotrigine (Wiffen 2011b), gabapentin (Moore 2011a), pregabalin (Moore 2009b) and valproic acid (Gill 2011), while reviews of phenytoin (Birse 2011) and clonazepam (Corrigan 2011) are in development. These separate reviews for individual drugs use more stringent criteria of validity, which include the level of response obtained, the duration of study and method of imputation of missing data (Moore 2010a). Appendix 1 gives details of recent changes to the thinking about chronic pain and evidence.

This Cochrane review will therefore assess evidence in ways that make both statistical and clinical sense, and will use developing criteria for what constitutes reliable evidence in chronic pain (Moore 2010a). Trials included and analysed will need to meet a minimum of reporting quality (blinding, randomisation), validity (duration, dose and timing, diagnosis, outcomes, etc) and size (ideally at least 500 participants in a comparison in which the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) is four or above (Moore 1998)). This does set high standards and marks a departure from how reviews have been done previously.

This review will be one of a series, and will be included in an overview of antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.

Objectives

To assess the analgesic efficacy of lacosamide for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.

To assess the adverse events associated with the clinical use of lacosamide for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with double‐blind assessment of participant outcomes following two weeks of treatment or longer, though the emphasis of the review is on studies of eight weeks or longer. We required full journal publication, with the exception of online clinical trial results summaries of otherwise unpublished clinical trials and abstracts with data for analysis. We did not include short abstracts (usually meeting reports). We excluded studies that were non‐randomised, studies of experimental pain, case reports and clinical observations.

Types of participants

Studies included adult participants aged 18 years and above. Participants could have one or more of a wide range of chronic neuropathic pain conditions including:

PDN;

postherpetic neuralgia;

trigeminal neuralgia;

phantom limb pain;

postoperative or traumatic neuropathic pain;

complex regional pain syndrome;

cancer‐related neuropathy;

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) neuropathy;

spinal cord injury;

and

fibromyalgia.

We would have included studies of participants with more than one type of neuropathic pain and analysed results according to the primary condition.

Types of interventions

Lacosamide in any dose, by any route, administered for the relief of neuropathic pain or fibromyalgia and compared to placebo, no intervention or any other active comparator.

Types of outcome measures

We anticipated that studies would use a variety of outcome measures, with the majority of studies using standard subjective scales (numerical rating scale (NRS) or visual analogue scale (VAS)) for pain intensity or pain relief, or both. We were particularly interested in Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) definitions for moderate and substantial benefit in chronic pain studies (Dworkin 2008). These are defined as at least 30% pain relief over baseline (moderate), at least 50% pain relief over baseline (substantial), much or very much improved on Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) (moderate), and very much improved on PGIC (substantial). These outcomes are different from those set out in the previous review (Saarto 2007), concentrating as they do on dichotomous outcomes where pain responses do not follow a normal (Gaussian) distribution. People with chronic pain desire high levels of pain relief, ideally more than 50%, and with pain not worse than mild (O'Brien 2010).

Primary outcomes

Patient reported pain relief of 30% or greater.

Patient reported pain relief of 50% or greater.

PGIC much or very much improved.

PGIC very much improved.

Secondary outcomes

Any pain‐related outcome indicating some improvement.

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

Participants experiencing any adverse event.

Participants experiencing any serious adverse event.

Withdrawals due to adverse events.

Specific adverse events, particularly somnolence and dizziness.

Ongoing discussion within the Cochrane Collaboration suggests adopting a common core data set for pain reviews and to reflect that, we used a working set of seven outcomes that might form such a core data set. This overlaps to some extent with outcomes already identified:

at least 50% pain reduction;

proportion below 30/100 mm on a VAS (no worse than mild pain);

patient global impression;

functioning;

adverse event withdrawal;

serious adverse events; and

death.

The 'Summary of findings' table includes at least 50% and at least 30% pain intensity reduction, PGIC, adverse event withdrawals, serious adverse events and death.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register (2011, Issue 4), The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2011, Issue 3) , MEDLINE (January 2000 to August 2011) and EMBASE (January 2000 to August 2011). There was no language restriction.

The search strategies are in Appendix 2 (MEDLINE), Appendix 3 (EMBASE) and Appendix 4 (CENTRAL).

Searching other resources

We searched reference lists of retrieved articles and reviews for any additional studies. We also approached UCB, the manufacturer of lacosamide, for information about completed and ongoing studies and examined both clinicaltrials.gov and clinicalstudyresults.org for relevant data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We determined study eligibility by reading each abstract identified by the search. We eliminated studies that clearly did not satisfy inclusion criteria and obtained full copies of the remaining studies. Two review authors read these studies independently and reached agreement by discussion. We did not anonymise studies in any way before assessment.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data using a standard form and agreed any discrepancies before entry into the Cochrane statistical software RevMan 5.1, or any other analysis method. The data extracted included information about the pain condition and number of participants treated, drug and dosing regimen, study design (placebo or active control), study duration and follow‐up, analgesic outcome measures and results, withdrawals and adverse events (participants experiencing any adverse event, or serious adverse event).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We completed a 'Risk of bias' table reporting on sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other risks (Higgins 2008).

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated NNTB as the reciprocal of the absolute risk reduction (McQuay 1997). For unwanted effects, the NNTB becomes the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH), and is calculated in the same manner. We used dichotomous data to calculate risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI using a fixed‐effect model unless we found significant statistical heterogeneity (see below). We use the term 'relative benefit' to refer to the risk of experiencing a beneficial outcome, and 'relative harm' for a harmful outcome. We did not use continuous data because dichotomous outcomes of clinical importance were available and preferred.

Unit of analysis issues

We accepted randomisation to individual patient only. The control treatment arm would be split between active treatment arms in a single study if the active treatment arms were not combined for analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We used intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. The ITT population consisted of participants who were randomised, took the assigned study medication, and provided at least one post‐baseline assessment. Wherever possible, we assigned zero improvement to missing participants. However, most studies in chronic pain report results, including responder results, using last observation carried forward. This has been questioned as being potentially biased (Moore 2010a; O'Connor 2010), with outcomes of withdrawal being important outcomes that make last observation carried forward unreliable (Kim 2011). Last observation carried forward can lead to overestimation of efficacy, particularly in situations where adverse event withdrawal rates differ between active and control groups (Moore 2012). At this time it is unclear what strategy can actually be used to deal with missing data inside studies, but we have examined and clearly reported imputation strategies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We dealt with clinical heterogeneity by combining studies that examine similar conditions. We assessed statistical heterogeneity visually (L'Abbé 1987) and with the use of the I2 statistic. When I2 was greater than 50%, we sought reasons.

Assessment of reporting biases

The aim of this review is to use dichotomous data of known utility (Moore 2009a). The review does not depend on what authors of the original studies chose to report or not. We planned to extract and use continuous data, which probably poorly reflect efficacy and utility, only if dichotomous data were not available and continuous data were useful for illustrative purposes, but we did not need to do this.

We assessed publication bias by examining the number of participants in trials with zero effect (relative risk of 1.0) needed for the point estimate of the NNTB to increase beyond a clinically useful level (Moore 2008). In this case, we specified a clinically useful level as an NNTB of 12.

Data synthesis

We used a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis. We planned to use a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis if there was significant heterogeneity and we considered it appropriate to combine studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analysis for:

dose of lacosamide;

different painful conditions.

Sensitivity analysis

No sensitivity analyses were planned, because the evidence base was known to be too small to allow reliable analysis; in particular, we did not pool results from neuropathic pain of different origins.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Electronic searches identified eight potentially relevant studies; no additional information was available from the manufacturer.

Included studies

We included five studies with 1863 participants in PDN (NCT00350103; Rauck 2007; Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010) and one study with 159 participants (NCT00401830) in fibromyalgia. Studies in PDN had a mean age of 55 to 60 years, and participants were 44% to 53% female. In four studies participants had a diagnosis of diabetes (type 1 or 2), with stable levels of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) below 12% or 10% (Rauck 2007) for the previous three months, and clinical symptoms of peripheral neuropathy for six months to five years. No details were available for diagnosis in the remaining study in PDN (NCT00350103). The study in fibromyalgia had a mean participant age of 50 years, with 93% female. Fibromyalgia was diagnosed according to American College of Rheumatology criteria. Baseline pain was at least moderate (≥ 4/10 on a NRS) in all participants.

All studies used a titration period of three to six weeks to achieve the target dose, starting at 100 mg daily and increasing by 100 mg increments, usually at weekly intervals (although one study had a fast titration arm in which the target dose was attained in eight days (NCT00350103)). The maintenance period following titration lasted 4 to 12 weeks, during which the target dose or maximum tolerated dose was maintained. Rauck 2007 was the only study that permitted limited back titration in the maintenance period. Target doses were 200 mg, 400 mg or 600 mg daily, administered in two equally divided doses.

Excluded studies

We excluded one study in post‐herpetic neuralgia, for which no data were published (NCT00681068), and one in PDN, which was a long‐term tolerance test that was not blinded or placebo‐controlled (Shaibani 2009b).

Risk of bias in included studies

Reporting quality was largely good. On the five‐point Oxford Quality Scale addressing randomisation, blinding and withdrawals, three PDN studies scored 5/5, one 4/5 and one 3/5. The fibromyalgia study scored 4/5. Scores above 3/5 indicate that major systematic bias is unlikely. Where one mark was lost, this was for inadequate description of the randomisation process. The study scoring only 3/5 (NCT00350103) was available only as an online results summary that did not provide detail on methods.

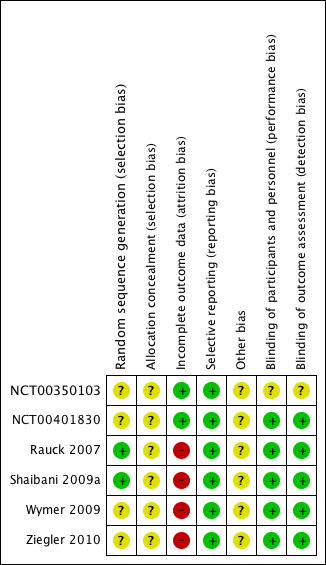

We compiled a 'Risk of bias' table (Characteristics of included studies; Figure 1). The only criterion indicating high risk of bias was that of incomplete outcome data.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

None of the studies adequately described the method used to conceal treatment allocation. In no case was there evidence that it was inadequate.

Blinding

One study (NCT00350103) did not adequately describe the method of blinding in the summary of results that was available to us; we judged it likely to have been adequate.

Incomplete outcome data

Studies used last observation carried forward as the imputation method for the primary outcome of pain relief. Data for PGIC, adverse events and withdrawals did not use imputation.

Selective reporting

All studies reported changes in pain intensity, but in two cases (NCT00350103; NCT00401830) only as group mean changes, which were the prespecified primary analyses, but were not suitable for pooled analysis in this review.

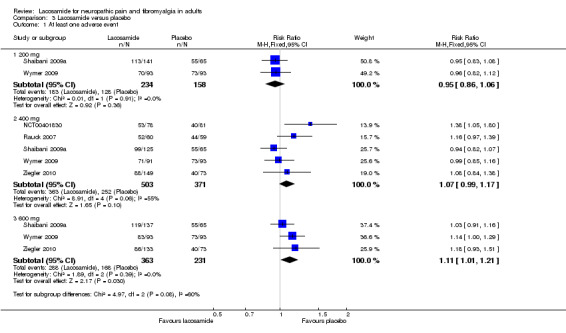

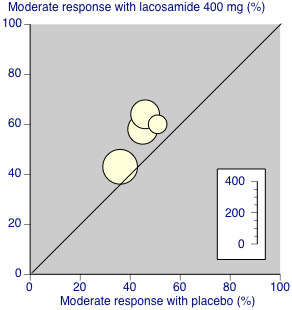

Other potential sources of bias

Four analyses, three combining only two studies (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.3) and one combining five studies (Analysis 3.1), had I2 values greater than 50% (55% to 68%). The most likely explanation for this is the very small number of studies in each analysis. Additionally the two 'outlying' studies in Analysis 3.1.2 were a little smaller and of shorter duration (10 and 12 weeks versus 18 weeks) than the other three studies. A L'Abbé plot showed consistent responses (Figure 2).

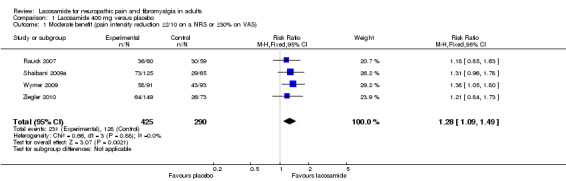

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Lacosamide 400 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Moderate benefit (pain intensity reduction ≥2/10 on a NRS or ≥30% on VAS).

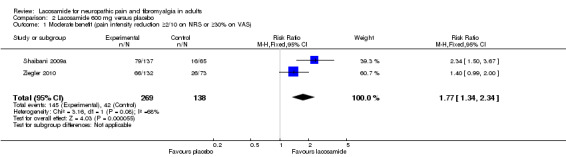

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Lacosamide 600 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Moderate benefit (pain intensity reduction ≥2/10 on NRS or ≥30% on VAS).

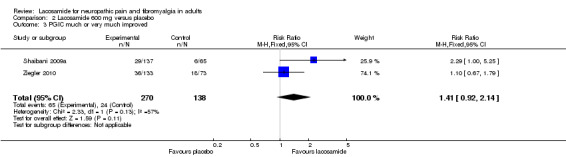

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Lacosamide 600 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 PGIC much or very much improved.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Lacosamide versus placebo, Outcome 1 At least one adverse event.

2.

L'Abbé plot of percentage of participants achieving a moderate response with lacosamide 400 mg daily or placebo. Each circle represents one study, with size of circle proportional to size of study (inset scale).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Results for individual studies are reported in Appendix 5 (efficacy and withdrawals) and Appendix 6 (adverse events)

Efficacy outcomes

Painful diabetic neuropathy

All five studies were of parallel group design, with study durations of 10 to 18 weeks, with stable maintenance phases of 4 (Rauck 2007) or 12 (remaining studies) weeks. Daily doses of lacosamide were from 200 to 600 mg. One study (NCT00350103), available only as a results summary on the Internet, reported only very limited data for group mean changes in pain intensity with lacosamide 400 mg and could not be included in any meta‐analysis for efficacy. The change in pain score from baseline in average daily pain score to the last four weeks of the study for the standard titration group was significantly greater than for placebo (mean difference ‐0.45/10 on a NRS), while for the fast titration group the change was numerically, but not significantly greater.

Outcomes consistent with IMMPACT recommendations for moderate and substantial benefit were reported in two or more of the remaining four studies. The results showed lacosamide at doses of 400 and 600 mg/d to be more effective than placebo. While two studies (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009) included doses of 200 mg/d, only Shaibani reported data suitable for analysis, so no pooled analysis was possible for this dose.

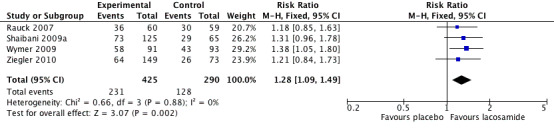

Moderate benefit

Four studies contributed data for pain reduction of ≥ 2/10 on a NRS or ≥ 30% on a VAS with lacosamide 400 mg (Rauck 2007; Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 715 participants, Figure 3).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Lacosamide 400 mg versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Moderate benefit (≥2/10 on NRS or ≥30% on VAS pain intensity reduction).

The proportion of participants with moderate benefit with lacosamide 400 mg was 54% (231/425, range 43% to 64%);

The proportion of participants with moderate benefit with placebo was 44% (128/290, range 36% to 46%);

The relative benefit of lacosamide 400 mg compared with placebo was 1.3 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.5), giving an NNTB of 9.8 (5.7 to 36) for moderate pain relief.

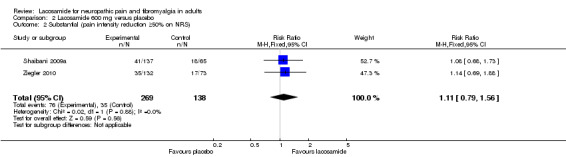

Two studies contributed data for pain reduction of ≥ 2/10 on a NRS or ≥ 30% on a VAS with lacosamide 600 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Ziegler 2010, 407 participants, Analysis 2.1).

The proportion of participants with moderate benefit with lacosamide 600 mg was 54% (145/269, range 50% to 58%);

The proportion of participants with moderate benefit with placebo was 30% (42/138, range 25% to 36%);

The relative benefit of lacosamide 600 mg compared with placebo was 1.8 (95% CI 1.3 to 2.3), giving an NNTB of 4.3 (3.0 to 7.3) for moderate pain relief.

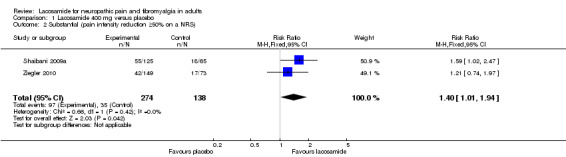

Substantial benefit

Two studies contributed data for pain reduction of ≥ 50% with lacosamide 400 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Ziegler 2010, 412 participants, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Lacosamide 400 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Substantial (pain intensity reduction ≥50% on a NRS).

The proportion of participants with substantial benefit with lacosamide 400 mg was 35% (97/274, range 28% to 44%);

The proportion of participants with substantial benefit with placebo was 25% (35/138, range 23% to 28%);

The relative benefit of lacosamide 400 mg compared with placebo was 1.4 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.9), giving an NNTB of 10 (5.2 to 120) for substantial pain relief.

The same two studies contributed data for pain reduction of ≥ 50% with lacosamide 600 mg (407 participants, Analysis 2.2)

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Lacosamide 600 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Substantial (pain intensity reduction ≥50% on NRS).

The proportion of participants with substantial benefit with lacosamide 600 mg was 28% (76/269, range 27% to 30%);

The proportion of participants with substantial benefit with placebo was 25% (35/138, range 23% to 28%);

The relative benefit of lacosamide 600 mg compared with placebo was 1.1 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.6) for substantial pain relief. The NNTB was not calculated.

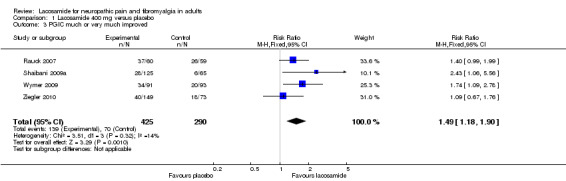

PGIC much or very much improved

PGIC categories of much or very much improved/better (the top two categories on the standard 7‐point scale) are considered to be equivalent to moderate benefit (Dworkin 2008).

Four studies contributed data for PGIC with lacosamide 400 mg (Rauck 2007; Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 715 participants, Analysis 1.3). For Shaibani and Wymer we used only "very much better" because "much better" was reported combined with "mildly better". This will give a conservative result for these two studies.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Lacosamide 400 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 PGIC much or very much improved.

The proportion of participants much or very much improved with lacosamide 400 mg was 33% (139/425, range 22% to 62%);

The proportion of participants much or very much improved with placebo was 24% (70/290, range 9% to 44%);

The relative benefit of lacosamide 400 mg compared with placebo was 1.5 (95% CI 1.2 to 1.9), giving an NNTB of 12 (6.6 to 52) for PGIC.

Two studies contributed data for PGIC much or very much improved with lacosamide 600 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009, 408 participants, Analysis 2.3). Again the category of "very much better" was used for Shaibani.

The proportion of participants much or very much improved with lacosamide 600 mg was 24% (65/270, range 21% to 27%);

The proportion of participants much or very much improved with placebo was 17% (24/138, range 9% to 25%);

The relative benefit of lacosamide 600 mg compared with placebo was 1.4 (95% CI 0.92 to 2.1) for PGIC. The NNTB was not calculated.

Fibromyalgia

The one study was of parallel group design, with a duration of 12 weeks (NCT00401830). It reported group mean (± standard deviation) changes from baseline in average daily pain score to the last two weeks of the study, with lacosamide 400 mg/d (1.8 ± 2.1) being numerically greater than placebo (1.3 ± 1.9). No statistical analysis was reported.

PGIC scores of much or very much improved were reported by 37% (29/78) with lacosamide 400 mg/d compared with 27% (22/81) with placebo.

Other conditions

No data were available for other types of neuropathic pain. We know of one unpublished study (44 participants) in postherpetic neuralgia but have been unable to obtain study results.

| Summary of results A: efficacy with different doses of lacosamide in different pain conditions | ||||||

| Outcome ‐ daily dose | Number of | Percent with outcome | Relative benefit (95% CI) | NNTB (95% CI) | ||

| Studies | Participants | Lacosamide | Placebo | |||

| Moderate benefit ‐ PDN | ||||||

| 400 mg | 4 | 715 | 54 | 44 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 9.8 (5.7 to 36) |

| 600 mg | 2 | 407 | 54 | 30 | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.3) | 4.3 (3.0 to 7.3) |

| Substantial benefit ‐ PDN | ||||||

| 400 mg | 2 | 412 | 35 | 25 | 1.4 (1.01 to 1.9) | 10 (5.2 to 120) |

| 600 mg | 2 | 407 | 28 | 25 | 1.1 (0.79 to 1.6) | Not calculated |

| PGIC much/very much improved ‐ PDN | ||||||

| 400 mg | 4 | 715 | 33 | 24 | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | 12 (6.6 to 52) |

| 600 mg | 2 | 408 | 24 | 17 | 1.4 (0.92 to 2.1) | Not calculated |

| PGIC much/very much improved ‐ fibromyalgia | ||||||

| 400 mg | 1 | 159 | 37 | 27 | Not calculated | Not calculated |

Adverse events

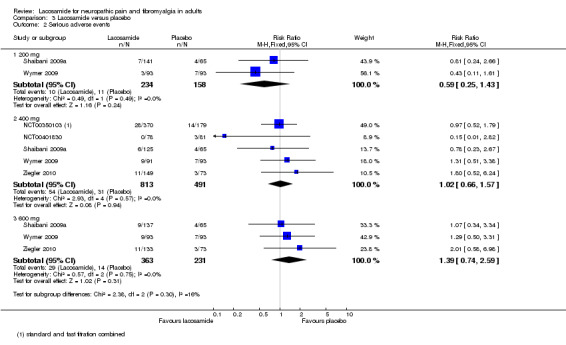

Participants experiencing at least one adverse event

Most adverse events with both lacosamide and placebo were described as mild or moderate in severity.

Two studies contributed data for participants experiencing at least one adverse event with lacosamide 200 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009, 392 participants).

The proportion of participants with at least one adverse event with lacosamide 200 mg was 78% (183/234, range 75% to 80%);

The proportion of participants with at least one adverse event with placebo was 81% (128/158, range 78% to 85%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 200 mg compared with placebo was 0.95 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.06). The NNTH was not calculated.

Five studies contributed data for participants experiencing at least one adverse event with lacosamide 400 mg (NCT00401830; Rauck 2007; Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 874 participants).

The proportion of participants with at least one adverse event with lacosamide 400 mg was 72% (363/503, range 59% to 87%);

The proportion of participants with at least one adverse event with placebo was 68% (252/371, range 49% to 85%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 400 mg compared with placebo was 1.1 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.2). The NNTH was not calculated.

There was no obvious difference between the study in fibromyalgia and those in PDN.

Three studies contributed data for participants experiencing at least one adverse event with lacosamide 600 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 594 participants).

The proportion of participants with at least one adverse event with lacosamide 600 mg was 79% (288/363, range 65% to 89%);

The proportion of participants with at least one adverse event with placebo was 73% (168/231, range 55% to 85%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 600 mg compared with placebo was 1.1 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.2). The NNTH was not calculated.

There was no significant difference between any dose of lacosamide and placebo for occurrence of any adverse events.

Participants experiencing serious adverse events

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Lacosamide versus placebo, Outcome 2 Serious adverse events.

Two studies contributed data for participants experiencing serious adverse events with lacosamide 200 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009, 392 participants).

The proportion of participants experiencing serious adverse events with lacosamide 200 mg was 4.3% (10/234, range 3% to 5%);

The proportion of participants experiencing serious adverse events with placebo was 7.0% (11/158, range 6% to 8%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 200 mg compared with placebo was 0.59 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.4). The NNTH was not calculated.

Five studies contributed data for participants experiencing serious adverse events with lacosamide 400 mg (NCT00350103; NCT00401830; Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 1304 participants).

The proportion of participants experiencing serious adverse events with lacosamide 400 mg was 6.6% (54/813, range 0% to 10%);

The proportion of participants experiencing serious adverse events with placebo was 6.3% (31/491, range 4% to 8%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 400 mg compared with placebo was 1.02 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.6). The NNTH was not calculated.

There was no obvious difference between the study in fibromyalgia and those in PDN.

Three studies contributed data for participants experiencing serious adverse events with lacosamide 600 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 594 participants).

The proportion of participants experiencing serious adverse events with lacosamide 600 mg was 8.0% (29/363, range 7% to 10%);

The proportion of participants experiencing serious adverse events with placebo was 6.1% (14/231, range 4% to 8%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 600 mg compared with placebo was 1.4 (95% CI 0.74 to 2.6). The NNTH was not calculated.

There was no difference between any dose of lacosamide and placebo for occurrence of serious adverse events.

| Summary of results B: adverse events with different doses of lacosamide | ||||||

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

| Outcome ‐ daily dose | Studies | Participants | Lacosamide | Placebo | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNTH (95% CI) |

| Any adverse event | ||||||

| 200 mg | 2 | 392 | 78 | 81 | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.1) | Not calculated |

| 400 mg | 5 | 874 | 72 | 68 | 1.1 (0.99 to 1.2) | Not calculated |

| 600 mg | 3 | 594 | 79 | 73 | 1.1 (1.01 to 1.2) | Not calculated |

| Serious adverse event | ||||||

| 200 mg | 2 | 392 | 4.3 | 7 | 0.59 (0.25 to 1.4) | Not calculated |

| 400 mg | 5 | 1304 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 1.02 (0.66 to 1.6) | Not calculated |

| 600 mg | 3 | 594 | 8 | 6 | 1.4 (0.74 to 2.6) | Not calculated |

Particular adverse events

All but one study (NCT00350103) provided details of individual adverse events in each treatment arm, where they occurred in at least five per cent of participants treated with lacosamide. A large number of different events were reported across the studies, but the majority were reported in only one or two of them. Overall adverse events tended to be numerically more frequent with the high dose, but with event rates generally well below 10%, these studies were not adequately powered to determine statistical significance.

No event was significantly more frequent with lacosamide 200 mg than with placebo. Outcomes for which statistical significance was demonstrated were:

Lacosamide 400 mg: dizziness relative risk 2.7 (95% CI 1.7 to 4.2), NNTH 11 (7.7 to 20) and tremor relative risk 2.0 (95% CI 1.1 to 3.7), NNTH 22 (12 to 160);

Lacosamide 600 mg: nausea relative risk 2.6 (95% CI 1.4 to 4.6), NNTH 11 (7.3 to 25); vomiting relative risk 8.7 (95% CI 1.2 to 65), NNTH 18 (11 to 42); dizziness relative risk 6.1 (95% CI 3.2 to 12), NNTH 4.8 (3.8 to 6.3); tremor relative risk 19 (95% CI 2.6 to 140), NNTH 8.1 (5.9 to 13).

The same studies all reported that there were no changes in laboratory values or on electrocardiography (ECG) that were considered clinically important or would cause concern, although prolongation of PR interval has been reported when lacosamide has been used to treat epilepsy. Tachycardia was reported in 3/60 participants with lacosamide 400 mg in one study (Rauck 2007). Two studies specifically reported no effect on HbA1c levels (Rauck 2007; Shaibani 2009a).

Deaths

One death was reported, with lacosamide 600 mg/d. It was judged unrelated to study medication (Shaibani 2009a).

Withdrawals

All cause withdrawals

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Lacosamide versus placebo, Outcome 3 All‐cause withdrawals.

Two studies contributed data for all cause withdrawals with lacosamide 200 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009, 392 participants).

The proportion of participants withdrawing for any reason with lacosamide 200 mg was 30% (70/234, range 26% to 33%);

The proportion of participants withdrawing for any reason with placebo was 29% (46/158, range 28% to 31%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 200 mg compared with placebo was 0.99 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.4). The NNTH was not calculated.

Five studies contributed data for all cause withdrawals with lacosamide 400 mg (NCT00401830; Rauck 2007; Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 874 participants).

The proportion of participants withdrawing for any reason with lacosamide 400 mg was 34% (172/503, range 23% to 43%);

The proportion of participants withdrawing for any reason with placebo was 28% (103/371, range 19% to 38%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 400 mg compared with placebo was 1.3 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.6), giving an NNTH of 16 (7.9 to 350).

There was no obvious difference between the study in fibromyalgia and those in PDN.

Three studies contributed data for all cause withdrawals with lacosamide 600 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 594 participants).

The proportion of participants withdrawing for any reason with lacosamide 600 mg was 55% (201/363, range 44% to 66%);

The proportion of participants withdrawing for any reason with placebo was 26% (61/231, range 21% to 31%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 600 mg compared with placebo was 2.1 (95% CI 1.7 to 2.7), giving an NNTH of 3.4 (2.7 to 4.7).

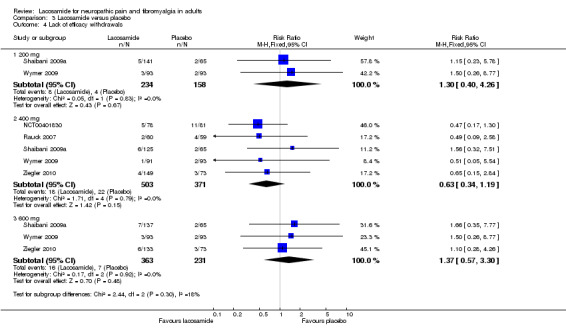

Lack of efficacy withdrawals

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Lacosamide versus placebo, Outcome 4 Lack of efficacy withdrawals.

Two studies contributed data for withdrawals due to lack of efficacy with lacosamide 200 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009, 392 participants).

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to lack of efficacy with lacosamide 200 mg was 3.4% (8/234, range 3% to 4%);

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to lack of efficacy with placebo was 2.5% (4/158, range 2% to 3%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 200 mg compared with placebo was 1.3 (95% CI 0.40 to 4.3). The NNTH was not calculated.

Five studies contributed data for withdrawals due to lack of efficacy with lacosamide 400 mg (NCT00401830; Rauck 2007; Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 874 participants).

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to lack of efficacy with lacosamide 400 mg was 3.6% (18/503, range 1% to 6%);

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to lack of efficacy with placebo was 5.9% (22/371, range 2% to 14%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 400 mg compared with placebo was 0.63 (95% CI 0.34 to 1.2). The NNTH was not calculated.

There was no obvious difference between the study in fibromyalgia and those in PDN.

Three studies contributed data for withdrawals due to lack of efficacy with lacosamide 600 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 594 participants).

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to lack of efficacy with lacosamide 600 mg was 4.4% (16/363, range 3% to 5%);

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to lack of efficacy with placebo was 3.0% (7/231, range 2% to 4%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 600 mg compared with placebo was 1.4 (95% CI 0.57 to 3.3). The NNTH was not calculated.

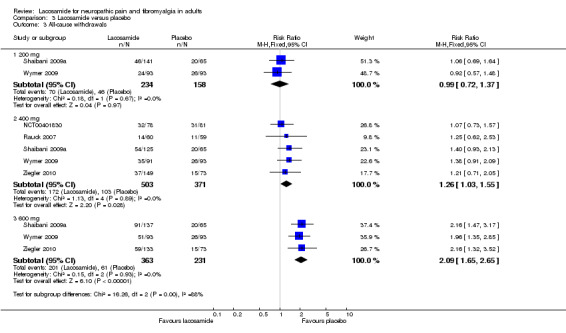

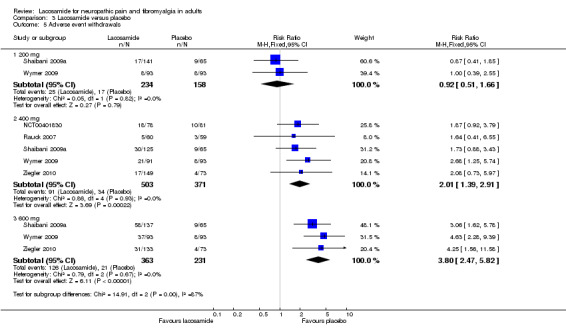

Adverse event withdrawals

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Lacosamide versus placebo, Outcome 5 Adverse event withdrawals.

Two studies contributed data for withdrawals due to adverse events with lacosamide 200 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009, 392 participants).

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to adverse events with lacosamide 200 mg was 11% (25/234, range 9% to 12%);

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to adverse events with placebo was 11% (17/158, range 9% to 41%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 200 mg compared with placebo was 0.92 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.7). The NNTH was not calculated.

Five studies contributed data for withdrawals due to adverse events with lacosamide 400 mg (NCT00401830; Rauck 2007; Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 874 participants).

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to adverse events with lacosamide 400 mg was 18% (91/503, range 8% to 24%);

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to adverse events with placebo was 9.2% (34/371, range 5% to 14%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 400 mg compared with placebo was 2.0 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.9), giving an NNTH of 11 (7.5 to 22).

There was no obvious difference between the study in fibromyalgia and those in PDN.

Three studies contributed data for withdrawals due to adverse events with lacosamide 600 mg (Shaibani 2009a; Wymer 2009; Ziegler 2010, 594 participants).

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to adverse events with lacosamide 600 mg was 35% (126/363, range 23% to 42%);

The proportion of participants withdrawing due to adverse events with placebo was 9.1% (21/231, range 5% to 14%);

The relative risk of lacosamide 600 mg compared with placebo was 3.8 (95% CI 2.5 to 5.8), giving an NNTH of 3.9 (3.2 to 5.1).

| Summary of results C: withdrawals with different doses of lacosamide | |||||||

| Number of | Percent with outcome | ||||||

| Outcome ‐ daily dose | Studies | Participants | Lacosamide | Placebo | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNTH (95% CI) | P for difference |

| All cause | |||||||

| 200 mg | 2 | 392 | 30 | 29 | 0.99 (0.72 to 1.4) | Not calculated | |

| 400 mg | 5 | 874 | 34 | 28 | 1.3 (1.03 to 1.6) | 16 (7.9 to 345) | 200 mg vs 400 mg z = 0.997 P = 0.317 |

| 600 mg | 3 | 594 | 55 | 26 | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.7) | 3.4 (2.7 to 4.7) | 400 mg vs 600 mg z = 4.498 P = < 0.0001 |

| Lack of efficacy | |||||||

| 200 mg | 2 | 392 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 1.3 (0.40 to 4.3) | Not calculated | |

| 400 mg | 5 | 874 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 0.63 (0.34 to 1.2) | Not calculated | |

| 600 mg | 3 | 594 | 4.4 | 3 | 1.4 (0.57 to 3.3) | Not calculated | |

| Adverse event | |||||||

| 200 mg | 2 | 392 | 11 | 11 | 0.92 (0.51 to 1.7) | Not calculated | |

| 400 mg | 5 | 874 | 18 | 9.1 | 2.01 (1.4 to 2.9) | 11 (7.5 to 22) | 200 mg vs 400 mg z = 2.298 P = 0.022 |

| 600 mg | 3 | 594 | 35 | 9.1 | 3.8 (2.5 to 5.8) | 3.9 (3.2 to 5.1) | 400 mg vs 600 mg z = 4.309 P = < 0.0001 |

There was no difference between lacosamide and placebo for lack of efficacy withdrawals, but a clear dose response for adverse event withdrawals, which was responsible for the dose response for all cause withdrawals.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The review included six randomised, double‐blind studies in which just over 2000 participants were titrated to a target dose of lacosamide 200 mg, 400 mg, or 600 mg or placebo and assessed following a stable dose period of 4 to 12 weeks. One study treated participants with fibromyalgia (NCT00401830) and the other five treated PDN. The two conditions were not combined for efficacy analyses.

High quality evidence was absent for any outcome at any dose of lacosamide, and moderate quality evidence for some efficacy outcomes for 400 mg lacosamide (Table 1); all other evidence, including any outcome for 200 mg or 600 mg lacosamide, was deemed to be low quality. The major factors limiting quality of the evidence were those of small numbers of patients and events, and for efficacy the use of imputation methods known to impart major bias where, as here, adverse event withdrawal rates were high. These factors suggest that any positive interpretation of the evidence should be made with caution if at all.

A moderate response (pain reduction of ≥ 2/10 on a NRS or ≥ 30% on a VAS) was experienced by 54% of participants with PDN treated with lacosamide 400 g or 600 mg, while response to placebo was 10% lower (44%) in studies using 400 mg, and 24% lower (30%) in studies using 600 mg. The NNTB for lacosamide 400 mg was about 10, while for 600 mg it was about 4, due to the lower placebo response rate. Use of the alternative measure of moderate response (PGIC much or very much improved) gave lower response rates in all treatment arms; the NNTB for lacosamide 400 mg was 12, but the difference was not significant for lacosamide 600 mg. Response rates for substantial response (pain reduction ≥ 50%) were lower in all treatment arms, as expected for a more difficult outcome. For lacosamide 400 mg the response rates were 35% and for placebo 25%, giving an NNTB of 10; while for lacosamide 600 mg the response rate was only 28%, which was not significantly different from placebo.

The single study in fibromyalgia had a response rate for PGIC much or very much improved that was similar to the response rate in PDN for lacosamide 400 mg.There was no significant difference between lacosamide (37%) and placebo (27%).

Between 70% and 80% of participants in all treatment groups experienced at least one adverse event, irrespective of condition or dose, with no significant difference between lacosamide and placebo. Serious adverse events were reported more frequently with higher doses of lacosamide, but the difference was not significant either between lacosamide and placebo or between doses.

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy also did not differ significantly between lacosamide and placebo, or between doses. However, adverse event withdrawals showed a clear dose response, with no difference from placebo for lacosamide 200 mg, an NNTH of 11 for 400 mg, and an NNTH of 4 for 600 mg. Adverse event withdrawals were primarily responsible for a similar dose response for all cause withdrawals.

We would expect that a higher dose would give better efficacy, but this review found that to be the case for only one outcome ‐ that of moderate benefit, as measured by a pain reduction of ≥ 2/10 on a NRS or ≥ 30% on VAS. Overall it would appear that the drug shows very limited efficacy in PDN, which together with the relative paucity of data (400 participants in comparisons using 600 mg), means that chance could easily tip the balance between being marginally effective and not significantly different from placebo.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review found five studies in PDN, one of which provided no usable efficacy data, and one study in fibromyalgia. Any conclusions are therefore limited to use of lacosamide to treat PDN.

Included studies were not of sufficient duration to determine the effects of long‐term use, but there have been a number of open‐label follow‐up studies. Shaibani 2009a is a two‐year extension of Rauck 2007, which claims continued benefits and safety for up to 2.5 years, although numbers are small and withdrawals due to adverse events continued throughout the study, at about 10% to 36% of remaining participants during successive stages of the trial. NCT00220337 reported no important long‐term safety issues (particularly cardiac and ECG events) and a sustained reduction in Likert pain score. Two other studies completed early in 2011 but have not yet reported results (NCT00546351; NCT00237458).

Quality of the evidence

Individual treatment groups were relatively small in size at around 100 participants (all > 50 and < 200), which potentially makes them susceptible to random chance and small study bias.

Efficacy outcomes were analysed using last observation carried forward as the imputation method for missing data. Where there is an imbalance of withdrawals due to lack of efficacy or adverse events between active and placebo treatment arms, as clearly seen in this review, this may lead to an overestimate of efficacy by about 50% for 400 mg and 250% for the 600 mg dose (Moore 2012).

Other aspects of methodological quality were good, although some studies did not describe full details of, for example, the method used to achieve randomisation or allocation concealment. Given that these studies have all been carried out by pharmaceutical companies in the last 10 years, this is more likely to be an omission of reporting than deficiency of methods.

Potential biases in the review process

We used an extensive search strategy and contacted the manufacturer for information about unpublished or ongoing reviews, but can never be certain that some studies have not been identified. We calculated the number of participants who would need to be in trials with zero effect (relative risk of 1.0) needed for the point estimate of the NNTB to increase beyond a clinically useful level. In this case, we chose a clinically useful level as 12, and calculated that only around 160 participants would have to have been involved in unpublished trials with zero treatment effects for the NNTB to increase above that level (Moore 2008). This is entirely possible and must be considered alongside the results of this review.

The use of last observation carried forward as the imputation method for the primary outcomes of this review may overestimate the efficacy outcome. Where there is an imbalance between comparator groups for withdrawals, particularly due to adverse events, this method of imputation allows participants who were experiencing pain relief but cannot tolerate the drug to contribute to efficacy at the end of the trial, despite stopping the medication. The effect is to inflate the result.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A review of pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pains in 2009 (Jensen 2009) reported that the role of lacosamide was uncertain, with one study (Wymer 2009) suggesting benefit and another (Shaibani 2009a) suggesting none. Two more recent reviews in 2010 (Dworkin 2010; McCleane 2009) again reported mixed findings and marginal benefits. These are entirely consistent with the findings of this review, but we have reported NNTBs and considerably more information on adverse events and withdrawals.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Lacosamide has shown, at best, marginal benefits for treating PDN. Most patients experience adverse events while taking the drug and while the majority of events are of mild or moderate severity and tolerated, 18% to 35% discontinue over the first few months of treatment with 400 mg to 600 mg daily, and with a clear dose response for all cause and adverse event discontinuations. Extension studies (for example, Shaibani 2009b) suggest that adverse event withdrawals continue with longer use, while pain relief is maintained in those who continue to tolerate the drug. Analgesic efficacy has not been adequately demonstrated in any other neuralgia, and lacosamide is not licensed to treat any painful conditions. Given the relatively low response rate for good levels of pain relief and significant numbers of withdrawals due to adverse events, it should (at best) be reserved for individuals who have failed on other treatments for which there is better evidence of efficacy and harm.

Implications for research.

To determine the true efficacy of lacosamide in PDN would require the manufacturer to provide data that enable analysis using baseline observation carried forward, or responder analysis where discontinuation is classified as non‐response. If its use is to be considered in other neuropathic pain conditions, adequately powered RCTs with responder analysis should be carried out and fully reported.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 February 2016 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes |

Notes

A restricted search in February 2016 did not identify any potentially relevant studies likely to change the conclusions. Therefore, this review has now been stabilised following discussion with the authors and editors. The review will be re‐assessed for updating in four years. If appropriate, we will update the review before this date if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Neuromuscular Disease Group editorial team, and thank the peer reviewers for their helpful comments on both the protocol and the full review.

The editorial base of the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group is supported by the MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methodological considerations in chronic pain

There have been several recent changes in how efficacy of conventional and unconventional treatments is assessed in chronic painful conditions. The outcomes are now better defined, particularly with new criteria of what constitutes moderate or substantial benefit (Dworkin 2008); older trials may only report participants with "any improvement". Newer trials tend to be larger, avoiding problems from the random play of chance. Newer trials also tend to be longer, up to 12 weeks, and longer trials provide a more rigorous and valid assessment of efficacy in chronic conditions. New standards have evolved for assessing efficacy in neuropathic pain, and we are now applying stricter criteria for inclusion of trials and assessment of outcomes, and are more aware of problems that may affect our overall assessment. To summarise some of the recent insights that must be considered in this new review:

Pain results tend to have a U‐shaped distribution rather than a bell‐shaped distribution. This is true in acute pain (Moore 2011b; Moore 2011c), back pain (Moore 2010c), arthritis (Moore 2010b), as well as in fibromyalgia (Straube 2010); in all cases average results usually describe the experience of almost no‐one in the trial. Data expressed as averages are potentially misleading, unless they can be proven to be suitable.

As a consequence, we have to depend on dichotomous results (the individual either has or does not have the outcome) usually from pain changes or patient global assessments. The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) group has helped with their definitions of minimal, moderate, and substantial improvement (Dworkin 2008). In arthritis, trials shorter than 12 weeks, and especially those shorter than eight weeks, overestimate the effect of treatment (Moore 2009a); the effect is particularly strong for less effective analgesics, and this may also be relevant in neuropathic‐type pain.

The proportion of patients with at least moderate benefit can be small, even with an effective medicine, falling from 60% with an effective medicine in arthritis, to 30% in fibromyalgia (Moore 2009b; Moore 2010b; Straube 2008; Sultan 2008). A Cochrane review of pregabalin in neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia demonstrated different response rates for different types of chronic pain (higher in diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia and lower in central pain and fibromyalgia) (Moore 2009b). This indicates that different neuropathic pain conditions should be treated separately from one another, and that pooling should not be done unless there are good grounds for doing so.

Finally, presently unpublished individual patient analyses indicate that patients who get good pain relief (moderate or better) have major benefits in many other outcomes, affecting quality of life in a significant way (Moore 2010d).

Appendix 2. MEDLINE OvidSP search strategy

1 randomized controlled trial.pt. 2 controlled clinical trial.pt. 3 randomized.ab. 4 placebo.ab. 5 drug therapy.fs. 6 randomly.ab. 7 trial.ab. 8 groups.ab. 9 or/1‐8 10 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 11 9 not 10 12 (lacosamide or erlosamide or vimpat).mp. 13 exp Pain/ 14 Fibromyalgia/ 15 (pain$ or fibromyalgi$ or neuralgi$ or analgesi$ or discomfort$).mp. 16 or/13‐15 17 11 and 12 and 16 18 remove duplicates from 17

Appendix 3. EMBASE OvidSP search strategy

1 crossover‐procedure/ 2 double‐blind procedure/ 3 randomized controlled trial/ 4 single‐blind procedure/ 5 (random$ or factorial$ or crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$ or placebo$ or (doubl$ adj blind$) or (singl$ adj blind$) or assign$ or allocat$ or volunteer$).tw. 6 or/1‐5 7 exp animals/ 8 exp humans/ 9 7 not (7 and 8) 10 6 not 9 11 limit 10 to embase 12 (lacosamide or erlosamide or vimpat).mp. 13 11 and 12 14 fibromyalgia/ 15 exp neuralgia/ 16 (pain$ or fibromyalgi$ or neuralgi$ or analgesi$ or discomfort$).mp. 17 or/14‐16 18 11 and 12 and 17 19 remove duplicates from 18

Appendix 4. CENTRAL search strategy

lacosamide or erlosamide or vimpat

MeSH descriptor Pain explode all trees

pain* or fibromyalgi* or neuralgi* or analgesi* or discomfort*

(#2 OR #3)

(#1 AND #4)

Appendix 5. Summary of results in individual studies: efficacy and withdrawals

| Study |

Numbers in trial Treatment groups |

Efficacy | All cause withdrawal | Lack of efficacy withdrawal | Adverse event withdrawal |

| NCT00350103 | N = 549 LCM 400 mg StT, n = 181 LCM 400 mg FT, n = 189 Placebo, n = 179 |

No usable data | 108 participants in total (groups not reported) | No data | 58 participants in total (groups not reported) |

| NCT00401830 | N = 159 LCM 400 mg, n = 78 Placebo, n = 81 |

PGIC moderately or much better LCM 400: 29/78 Placebo: 22/81 | LCM 400: 32/78 Placebo: 50/81 |

LCM 400: 5/78 Placebo: 1/81 |

LCM 400: 18/78 Placebo: 10/81 |

| Rauck 2007 | N = 119 LCM 400 mg, n = 60 Placebo, n = 59 |

≥ 2‐point reduction on NRS

LCM 400: 36/60

Placebo: 30/59 PGIC moderately or much better LCM 400: 37/60 Placebo: 26/59 |

LCM 400: 14/60 Placebo: 11/59 |

LCM 400: 2/60 Placebo: 4/59 |

LCM 400: 5/60 Placebo: 3/59 |

| Shaibani 2009 | N = 468 LCM 200 mg, n = 141 LCM 400 mg, n = 125 LCM 600 mg, n = 137 Placebo, n = 65 |

≥ 30% reduction in pain scores from baseline to end

LCM 200: 76/141 LCM 400: 73/125 LCM 600: 79/137 Placebo: 29/65 ≥ 50% reduction in pain scores from baseline to end LCM 200: 38/141 LCM 400: 55/125 LCM 600: 41/137 Placebo: 18/65 PGIC much better LCM 400: 28/125 Placebo: 6/65 |

LCM 200: 46/141 LCM 400: 54/125 LCM 600: 91/137 Placebo: 21/65 |

LCM 200: 5/141 LCM 400: 6/125 LCM 600: 7/137 Placebo: 2/65 |

LCM 200: 17/141 LCM 400: 30/125 LCM 600: 58/137 Placebo: 9/65 |

| Wymer 2009 | N = 370 LCM 200 mg, n = 93 LCM 400 mg, n = 91 LCM 600 mg, n = 93 Placebo, n = 93 |

≥ 30% or ≥ 2‐point reduction on NRS

LCM 400: 58/91

Placebo: 43/93 PGIC much better LCM 400: 34/91 Placebo: 20/93 200 and 600 mg/d full details not given. 200 and 600 mg numerically better than placebo for responder, but not statistically significant. 200 mg inferior to placebo for all secondary outcomes. 600 mg superior to placebo for pain reduction during whole maintenance phase |

LCM 200: 24/93 LCM 400: 35/91 LCM 600: 51/93 Placebo: 26/93 |

LCM 200: 3/93 LCM 400: 1/91 LCM 600: 3/93 Placebo: 2/93 |

LCM 200: 8/93 LCM 400: 21/91 LCM 600: 37/93 Placebo: 8/93 |

| Ziegler 2010 | N = 357 LCM 400 mg StT, n = 73 LCM 400 mg SlT, n = 77 LCM 600 mg, n = 133 Placebo, n = 74 |

≥ 30% or ≥ 2‐point reduction on NRS

LCM 400 StT + SlT: 64/149 LCM 600:66/132 Placebo: 26/74 ≥ 50% reduction on NRS LCM 400 StT + SlT: 42/149 LCM 600: 35/132 Placebo: 17/74 PGIC moderately or much better LCM 400: 40/149 LCM 600: 36/133 Placebo: 18/73 |

LCM 400 StT + SlT: 37/149 LCM 600: 59/132 Placebo: 15/74 |

LCM 400 StT + SlT: 4/149 LCM 600: 6/132 Placebo: 3/74 |

LCM 400 StT + SlT: 17/149 LCM 600: 31/132 Placebo: 4/74 |

| LCM ‐ lacosamide; FT ‐ fast titration; NRS ‐ numerical rating scale; PGIC ‐ patient global impression of change; SlT ‐ slow titration; StT ‐ standard titration | |||||

Appendix 6. Summary of results in individual studies: adverse events

| Study |

Numbers in trial Treatment groups |

Any adverse event | Serious adverse event |

| NCT00350103 | N = 551 LCM 400 mg StT, n = 181 LCM 400 mg FT, n = 189 Placebo, n = 179 |

No usable data | LCM 400: 28/370 Placebo: 14/179 |

| NCT00401830 | N = 159 LCM 400 mg, n = 78 Placebo, n = 81 |

LCM 400: 53/78 Placebo: 40/81 |

LCM 400: 0/78 Placebo: 3/81 |

| Rauck 2007 | N = 119 LCM 400 mg, n = 60 Placebo, n = 59 |

LCM 400: 52/60 Placebo: 44/59 |

No data |

| Shaibani 2009 | N = 468 LCM 200 mg, n = 141 LCM 400 mg, n = 125 LCM 600 mg, n = 137 Placebo, n = 65 |

LCM 200: 113/141 LCM 400: 99/125 LCM 600: 119/137 Placebo: 55/65 |

LCM 200: 7/141 LCM 400: 6/125 LCM 600: 9/137 Placebo: 4/65 |

| Wymer 2009 | N = 370 LCM 200 mg, n = 93 LCM 400 mg, n = 91 LCM 600 mg, n = 93 Placebo, n = 93 |

LCM 200: 70/93 LCM 400: 71/91 LCM 600: 83/93 Placebo: 73/93 |

LCM 200: 3/93 LCM 400: 9/91 LCM 600: 9/93 Placebo: 7/93 |

| Ziegler 2010 | N = 357 LCM 400 mg StT, n = 73 LCM 400 mg SlT, n = 77 LCM 600 mg, n = 133 Placebo, n = 73 |

LCM 400: 88/149 LCM 600: 86/133 Placebo: 40/73 |

LCM 400: 11/149 LCM 600: 11/133 Placebo: 3/73 |

| LCM ‐ lacosamide; FT ‐ fast titration; SlT ‐ slow titration; StT ‐ standard titration | |||

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Lacosamide 400 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Moderate benefit (pain intensity reduction ≥2/10 on a NRS or ≥30% on VAS) | 4 | 715 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [1.09, 1.49] |

| 2 Substantial (pain intensity reduction ≥50% on a NRS) | 2 | 412 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [1.01, 1.94] |

| 3 PGIC much or very much improved | 4 | 715 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.49 [1.18, 1.90] |

Comparison 2. Lacosamide 600 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Moderate benefit (pain intensity reduction ≥2/10 on NRS or ≥30% on VAS) | 2 | 407 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.77 [1.34, 2.34] |

| 2 Substantial (pain intensity reduction ≥50% on NRS) | 2 | 407 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.79, 1.56] |

| 3 PGIC much or very much improved | 2 | 408 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.92, 2.14] |

Comparison 3. Lacosamide versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 At least one adverse event | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 200 mg | 2 | 392 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.86, 1.06] |

| 1.2 400 mg | 5 | 874 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.99, 1.17] |

| 1.3 600 mg | 3 | 594 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [1.01, 1.21] |

| 2 Serious adverse events | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 200 mg | 2 | 392 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.25, 1.43] |

| 2.2 400 mg | 5 | 1304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.66, 1.57] |

| 2.3 600 mg | 3 | 594 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.74, 2.59] |

| 3 All‐cause withdrawals | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 200 mg | 2 | 392 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.72, 1.37] |

| 3.2 400 mg | 5 | 874 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [1.03, 1.55] |

| 3.3 600 mg | 3 | 594 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.09 [1.65, 2.65] |

| 4 Lack of efficacy withdrawals | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 200 mg | 2 | 392 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.40, 4.26] |

| 4.2 400 mg | 5 | 874 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.34, 1.19] |

| 4.3 600 mg | 3 | 594 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.57, 3.30] |

| 5 Adverse event withdrawals | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 200 mg | 2 | 392 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.51, 1.66] |

| 5.2 400 mg | 5 | 874 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [1.39, 2.91] |

| 5.3 600 mg | 3 | 594 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.80 [2.47, 5.82] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

NCT00350103.

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel group Standard titration ‐ 400 mg/d attained at day 22; fast titration ‐ 400 mg/d attained at day 8 Maximum study duration 18 weeks, with 12‐week maintenance phase |

|

| Participants | Diabetic neuropathic pain ‐ no further details of diagnosis. Age 57 ± 10 years, 51% female. Baseline pain not reported N = 549 |

|

| Interventions | Lacosamide 400 mg standard titration, n = 181 Lacosamide 400 mg fast titration, n = 189 Placebo, n = 179 |

|

| Outcomes | Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 1, W = 1. Total = 3/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Imputation using last observation carried forward for efficacy data, but not used. ITT for adverse events and withdrawals |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Expected outcomes were reported in some way, although not necessarily as our preferred outcome |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Group sizes 50 to 200 |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

NCT00401830.

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel, no enrichment. LOCF imputation 12‐week treatment period: 4‐week titration from 100 mg/d to 400 mg/d, increasing by 100 mg/d at weekly intervals; 8‐week maintenance |

|

| Participants | Fibromyalgia (ACR criteria), duration not given. Age 18 to 65 years (mean 50 years), 93% female. Baseline pain ≥ 5/10 on a NRS N = 159 |

|

| Interventions | Lacosamide 400 mg/d, n = 78 Placebo, n = 81 Medication given as 2 equally‐divided doses |

|

| Outcomes | Change in pain score (11‐point NRS) PGIC (7‐point scale) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Imputation using last observation carried forward for efficacy data, but not used. ITT for PGIC, adverse events and withdrawals |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Expected outcomes were reported in some way, although not necessarily as our preferred outcome |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Group sizes 50 to 200 |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "matching placebo tablet" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patient reported and patient blinded |

Rauck 2007.

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel, no enrichment. LOCF imputation and completer analyses 10‐week treatment period: 4‐week run‐in phase; randomisation; 100 mg/d for 3 weeks; titration over next 3 weeks to maximum tolerated dose or 400 mg/d; 4 weeks of maintenance; 1‐week taper |

|

| Participants | PDN of 1 to 5 years duration. Age ≥ 18 years (mean 55 years), 53% female, > 90% white. Baseline pain intensity ≥ 4/10, mean baseline pain score 6.6/10 on a NRS N = 119 |

|

| Interventions | Lacosamide 400 mg/d, n = 60 Placebo, n = 59 Rescue analgesic: paracetamol ≤ 2 g/d |

|

| Outcomes | Change in pain score (≥ 2‐point reduction on NRS = responder) PGIC (7‐point scale) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "computer‐generated randomization schedule" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Imputation using last observation carried forward for efficacy data. ITT for PGIC, adverse events and withdrawals |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in Methods were reported in some way, although not necessarily as our preferred outcome |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Group sizes 50 to 200 |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "identical‐in‐appearance" medication packs |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patient reported and patient blinded |

Shaibani 2009a.

| Methods | Multi‐centre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel, no enrichment. LOCF imputation for last 4 weeks 18‐week treatment period: 2‐week run‐in; randomisation; 6‐week titration (100 mg/d for first week, then increasing by 100 mg/d per week to target); 12‐week maintenance |

|

| Participants | PDN of 6 months to 5 years duration. Age ≥ 18 years (mean 60 years), 44% female, 80% white, baseline pain intensity ≥ 4/10 on a NRS (54% scored 6 to 10) N = 468 |

|

| Interventions | Lacosamide 200 mg, n = 141 Lacosamide 400 mg, n = 125 Lacosamide 600 mg, n = 137 Placebo, n = 65 Mediaction given as two equally‐divided doses Rescue analgesic: paracetamol ≤ 2 g/d |

|

| Outcomes | Change in pain score (≥ 2‐point reduction on NRS = responder) PGIC (7‐point scale) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "computer‐generated list" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Imputation using last observation carried forward for last 4 weeks of efficacy data, ITT for PGIC, adverse events and withdrawals |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in Methods were reported in some way, although not necessarily as our preferred outcome |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Group sizes 50 to 200 |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "tablets were identical in appearance and packaging" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patient reported and patient blinded |

Wymer 2009.

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel, no enrichment. LOCF imputation 18‐week treatment period: 2‐week run‐in; randomisation; 6‐week titration (100 mg/d for first week, then increasing by 100 mg/d per week to target); 12‐ week maintenance |

|

| Participants | PDN of 6 months to 5 years duration. Age ≥ 18 years (mean 58 years), 45% female, 81% white. Baseline pain intensity ≥ 4/10 on a NRS (62% scored 6 to 10) N = 370 |

|

| Interventions | Lacosamide 200 mg, n = 93 Lacosamide 400 mg, n = 91 Lacosamide 600 mg, n = 93 Placebo, n = 93 Mediaction given as two equally‐divided doses Rescue analgesic: paracetamol ≤ 2 g/d |

|

| Outcomes | Change in pain score (≥ 2‐point or ≥ 30% reduction on NRS = responder) PGIC (7‐point scale) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "computer‐generated list" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Imputation using last observation carried forward for efficacy data, ITT for PGIC, adverse events and withdrawals |