Abstract

Background

Social networking platforms offer a wide reach for public health interventions allowing communication with broad audiences using tools that are generally free and straightforward to use and may be combined with other components, such as public health policies. We define interactive social media as activities, practices, or behaviours among communities of people who have gathered online to interactively share information, knowledge, and opinions.

Objectives

We aimed to assess the effectiveness of interactive social media interventions, in which adults are able to communicate directly with each other, on changing health behaviours, body functions, psychological health, well‐being, and adverse effects.

Our secondary objective was to assess the effects of these interventions on the health of populations who experience health inequity as defined by PROGRESS‐Plus. We assessed whether there is evidence about PROGRESS‐Plus populations being included in studies and whether results are analysed across any of these characteristics.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE (including trial registries) and PsycINFO. We used Google, Web of Science, and relevant web sites to identify additional studies and searched reference lists of included studies. We searched for published and unpublished studies from 2001 until June 1, 2020. We did not limit results by language.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled before‐and‐after (CBAs) and interrupted time series studies (ITSs). We included studies in which the intervention website, app, or social media platform described a goal of changing a health behaviour, or included a behaviour change technique. The social media intervention had to be delivered to adults via a commonly‐used social media platform or one that mimicked a commonly‐used platform. We included studies comparing an interactive social media intervention alone or as a component of a multi‐component intervention with either a non‐interactive social media control or an active but less‐interactive social media comparator (e.g. a moderated versus an unmoderated discussion group).

Our main outcomes were health behaviours (e.g. physical activity), body function outcomes (e.g. blood glucose), psychological health outcomes (e.g. depression), well‐being, and adverse events. Our secondary outcomes were process outcomes important for behaviour change and included knowledge, attitudes, intention and motivation, perceived susceptibility, self‐efficacy, and social support.

Data collection and analysis

We used a pre‐tested data extraction form and collected data independently, in duplicate. Because we aimed to assess broad outcomes, we extracted only one outcome per main and secondary outcome categories prioritised by those that were the primary outcome as reported by the study authors, used in a sample size calculation, and patient‐important.

Main results

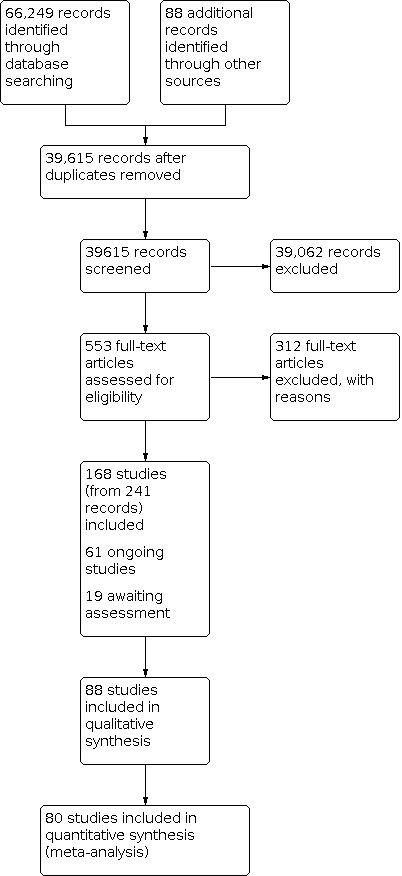

We included 88 studies (871,378 participants), of which 84 were RCTs, three were CBAs and one was an ITS. The majority of the studies were conducted in the USA (54%). In total, 86% were conducted in high‐income countries and the remaining 14% in upper middle‐income countries. The most commonly used social media platform was Facebook (39%) with few studies utilising other platforms such as WeChat, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Google Hangouts. Many studies (48%) used web‐based communities or apps that mimic functions of these well‐known social media platforms.

We compared studies assessing interactive social media interventions with non‐interactive social media interventions, which included paper‐based or in‐person interventions or no intervention. We only reported the RCT results in our 'Summary of findings' table. We found a range of effects on health behaviours, such as breastfeeding, condom use, diet quality, medication adherence, medical screening and testing, physical activity, tobacco use, and vaccination. For example, these interventions may increase physical activity and medical screening tests but there was little to no effect for other health behaviours, such as improved diet or reduced tobacco use (20,139 participants in 54 RCTs). For body function outcomes, interactive social media interventions may result in small but important positive effects, such as a small but important positive effect on weight loss and a small but important reduction in resting heart rate (4521 participants in 30 RCTs). Interactive social media may improve overall well‐being (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.14 to 0.79, moderate effect, low‐certainty evidence) demonstrated by an increase of 3.77 points on a general well‐being scale (from 1.15 to 6.48 points higher) where scores range from 14 to 70 (3792 participants in 16 studies). We found no difference in effect on psychological outcomes (depression and distress) representing a difference of 0.1 points on a standard scale in which scores range from 0 to 63 points (SMD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.12, low‐certainty evidence, 2070 participants in 12 RCTs).

We also compared studies assessing interactive social media interventions with those with an active but less interactive social media control (11 studies). Four RCTs (1523 participants) that reported on physical activity found an improvement demonstrated by an increase of 28 minutes of moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity per week (from 10 to 47 minutes more, SMD 0.35, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.59, small effect, very low‐certainty evidence). Two studies found little to no difference in well‐being for those in the intervention and control groups (SMD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.13, small effect, low‐certainty evidence), demonstrated by a mean change of 0.4 points on a scale with a range of 0 to 100.

Adverse events related to the social media component of the interventions, such as privacy issues, were not reported in any of our included studies.

We were unable to conduct planned subgroup analyses related to health equity as only four studies reported relevant data.

Authors' conclusions

This review combined data for a variety of outcomes and found that social media interventions that aim to increase physical activity may be effective and social media interventions may improve well‐being. While we assessed many other outcomes, there were too few studies to compare or, where there were studies, the evidence was uncertain. None of our included studies reported adverse effects related to the social media component of the intervention. Future studies should assess adverse events related to the interactive social media component and should report on population characteristics to increase our understanding of the potential effect of these interventions on reducing health inequities.

Keywords: Adolescent, Adult, Humans, Young Adult, Behavior Therapy, Behavior Therapy/methods, Bias, Controlled Before-After Studies, Exercise, Fruit, Health Behavior, Health Equity, Heart Rate, Interrupted Time Series Analysis, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Social Media, Social Networking, Treatment Outcome, Vegetables, Weight Loss

Plain language summary

Can programmes on social media help people to improve their health?

Key messages

Programmes on social media (such as Facebook or Twitter) that aim to increase physical activity may help people to become more physically active and may improve people's well‐being.

Future studies are needed to find out if there are any unwanted effects associated with taking part in interactive social media programmes.

What is social media?

Social media are computer‐based technologies that help people to share ideas, thoughts and information by building virtual networks and communities on the Internet; examples include, Facebook, Twitter or WhatsApp. Social media networks are 'interactive': the user communicates directly with a computer, or other device, to share and receive information.

What did we want to find out?

People who use social media can exchange ideas and share updates about their behaviours, such as becoming more active or eating more healthily. We wanted to find out if health programmes using interactive social media could change people's behaviours and improve their health.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that tested the effects of interactive social media programmes on people's health. We were interested in how the programmes might affect people's:

‐ health behaviours (such as smoking, drinking alcohol, breastfeeding, dieting, physical activity; seeking and using health services);

‐ health (such as physical fitness, lung function, asthma episodes);

‐ mental health (such as measures of depression, stress, coping);

‐ well‐being; and

‐ whether people reported any unwanted effects related to interactive social media programmes.

How up to date is this review?

We included evidence published up to 1 June 2020.

What did we find?

We found 88 studies involving 871,378 adults (aged 18 years and older). Most studies (49) took place in the USA; all studies took place in either high‐income countries or upper middle‐income countries. Facebook was the most commonly used social media platform; others included WeChat, Twitter, WhatsApp and Google Hangouts.

In most studies the effects of interactive social media programmes were compared against non‐interactive programmes, including paper‐based or in‐person programmes, or no programme. Ten studies compared two social media programmes against each another; for these studies we chose the more interactive of the two programmes as the 'interactive social media programme'.

What are the main results of our review?

Compared with non‐interactive programmes, social media programmes:

‐ may improve some health behaviours, such as increasing the number of daily steps taken, or taking part in screening tests, but may show little to no effect on other health behaviours, such as better diet or reducing tobacco use (evidence from 54 studies in 20,139 people).

‐ may cause small improvements in health, such as a small increase in amount of weight lost, and a small reduction in resting heart rate (evidence from 30 studies in 4521 people).

‐ may improve people's well‐being (evidence from 16 studies in 3792 people).

‐ may have little to no effect on people's mental health, such as depression (evidence from 12 studies in 2070 people).

No studies reported any unwanted effects related to using social media.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Overall, our confidence in the evidence is low. Many studies did not report clearly how they were conducted. In most studies, people knew whether they were taking part in an interactive programme, and this may have affected the results of the study. Some of the studies did not report all their results, and there were wide variations in the results of some studies. Further research is likely to increase our confidence in the evidence.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings ‐ Interactive Social Media compared to non‐interactive social media.

| Interactive social media compared with non‐interactive social media for public health | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults Settings: h‐High and high‐middle income countries Intervention: interactive social media Comparison: non‐interactive social media | ||||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effect (95% CI)1 | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Health behaviours | Overall, interactive social media interventions may improve health behaviours slightly. These effects varied according to the purpose of the intervention and ranged from, for example, a large increase in the number of daily steps (1377 more steps, from 708 to 2045 more) to little to no difference in diet quality (e.g. increase of 0.35 servings of fruits and vegetables per week (from 1.25 fewer servings to 1.96 more). | 20,139 (54 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | Health behaviours included: physical activity, diet quality, breastfeeding, calorie intake, condom use, health screening, medication, and vaccination uptake, and tobacco use. Additional details in Table 2 | ||

| Body function | Overall, interactive social media interventions may result in a small improvements in body function outcomes, for example, a small but important effect on weight loss (1.34 more kg (from 0.69 to 2.0 more kg) and a small but important effect on cardiorespiratory heart rate (reduction in resting heart rate by 2.50 beats per minute (from 6.17 beats per minute lower to 1.17 higher). | 4521 (30 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | Body function outcomes included weight, blood glucose, blood pressure, BMI, cardiorespiratory fitness, dyspnoea, influenza‐like illness. Additional details in Table 3 | ||

| Well‐being Outcomes ‐ General well‐being and Quality of life | The mean well‐being score was 8.2 in the control group. | The mean well‐being score in the social media group was 3.77 points higher (from 1.15 higher to 6.48 points higher). | SMD 0.46 (0.14 to 0.79) | 3792 (16 studies RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4 | Interactive social media interventions may improve well‐being scores slightly. Absolute effect calculated using Hutchesson 2018 (Quality of Life, Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, scores range from 14‐70, higher scores indicate greater well‐being). Additional details in Table 4 |

| Psychological outcomes ‐ Distress and Depression | The mean depression score in the control group was 8.8. | The mean score in the social media group was 0.1 points lower (from 1.23 lower to 1.06 higher) | SMD ‐0.01 (‐0.14 to 0.12) | 2070 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4 | Interactive social media interventions may have little to no effect on psychological outcomes. Absolute effect calculated using Wan 2017 (Beck Depression Inventory II, scores range from 0‐63, higher scores indicate greater degree of depression). Additional details in Table 4 |

| Adverse events | No adverse events were reported related to interactive social media. | ‐ | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5 | Adverse events that were reported were not related to the social media components of the intervention, e.g. injuries related to physical activity, and no studies reported on online harassment or privacy concerns. | ||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1. Effect sizes were determined using the rule of thumb for SMDs: 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect and 0.8 a large effect

2. Downgraded by 2 for unclear risks of bias as well as inconsistency.

3. Downgraded by 3 for high risks of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision.

4. Downgraded by 2 for unclear risks of bias and inconsistency.

5. Downgraded by 3 because no studies reported on this outcome.

1. 'Summary of findings' table: health behaviours.

| Any interactive social media intervention compared with non‐interactive social media on health behaviours (RCTs) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults Settings: high and high‐middle income countries Intervention: interactive social media Comparison: non‐interactive social media | ||||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effect (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Physical activity | Adults in the control group had 3770 steps per day | The mean number of steps per day increased by 74 steps for the intervention group (from 32 to 116 more steps) | SMD 0.28 (0.12 to 0.44) | 6250 (29 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | Absolute effect calculated using Wan 2017 |

| Diet quality | Adults in the control group consumed an average of 22.7 servings of fruit and vegetables per week. | The participants in the intervention increased their weekly fruit and vegetable intake by 0.35 servings (from 1.25 fewer servings to 1.96 more servings per week. | SMD 0.11 (‐0.25 to 0.47) | 1240 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | Absolute effect calculated using Bantum 2014 |

| Calorie intake | The mean number of calories was 53.75 lower in the intervention group (from 172.48 lower to 44.97 higher | MD ‐53.75 (‐172.48 to 44.97) | 131 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | ||

| Tobacco use | 12.72% of participants in the control group abstained from smoking. | 12.47% of intervention group participants abstained from smoking (from 9.4 to 16.4%). | RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.74, 1.29) | 2433 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | Absolute effect calculated using Ramo 2015 |

| Condom use | The participants in the control group reporting condom use frequency of 3.28 on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (always). | The intervention group reported condom use frequency 0.34 higher (from 0.51 fewer to 1.17 more). | SMD 0.22 (‐0.33 to 0.76) | 848 (2 RCTs) |

low5 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

Absolute effect calculated using Sun 2017 |

| Health screening, medication, vaccination uptake | The mean uptake was 86.8% for the control group. | The mean uptake in the social media group was 2.08% higher (from 1.32% lower to 5.62% higher). | SMD 0.11 (‐0.07, 0.30) | 3016 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6 | Absolute effect calculated using Horvath 2013 |

| Adverse events | Not assessed | ‐‐ | 0 (0 studies) | ‐‐ | ||

| * The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1. Downgraded by 1 for high heterogeneity (I2 = 84%) and unclear risk of bias.

2. Downgraded by 2 for high heterogeneity (I2 = 86%) and imprecision.

3. Downgraded by 1 for unclear risk of bias.

4. Downgraded by 1 because of high risk of bias.

5. Downgraded by 2 because of high risk of bias and imprecision.

6. Downgraded by 1 because of unclear risks of bias.

2. 'Summary of findings' table: body functions.

| Any interactive social media intervention compared with non‐interactive social media on body function | |||||

|

Patient or population: adults Settings: high and high‐middle income countries Intervention: interactive social media Comparison: non‐interactive social media | |||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effect (95% Cl) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Weight (kg) | Participants receiving the social media intervention lost 1.34 more kg (from 0.69 to 2.0 more kg) than those in the control group. | MD ‐1.34 kg (‐2.0 to ‐0.69) | 1963 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| BMI | Participants receiving the social media intervention reduced their BMI by 0.51 kg/m2 compared to the control group (from 0.10 to 0.92 kg/m2) more. | MD ‐0.51 (‐0.92 to ‐0.10) | 323 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Blood glucose | The mean blood glucose level was 1.74 mmol/L lower (from 0.68 to 2.79 mmol/L lower) for the social media group compared to the control group. | MD ‐1.74 mmol/L (‐2.79 to ‐0.68) | 773 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | The cardiorespiratory fitness was 2.50 heart beats per minute lower for the participants in the social media group (from 6.17 beats per minute lower to 1.17 higher) | MD ‐2.5 heart beats per minute (‐6.17 to 1.17) | 89 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | |

| Insomnia | Insomnia scores for the social media group were 0.90 points lower (from 0.56 to 1.24 points lower) than the control group on an insomnia scale assessing how often a person has had trouble falling or staying asleep on 5‐point Likert scale. | MD ‐0.90 (‐1.24 to ‐0.56) | 303 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4 | |

| Dyspnoea | Dyspnea scores were 0.20 points lower for participants in the social media group (from 3.10 points lower to 2.7 points higher) on a scale of 0‐4.. | MD ‐0.20 (‐3.1 to 2.70) | 109 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ verylow5 | |

| Adverse events | Not assessed | ‐‐‐ | 0 (0 studies) | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: Mean Difference; KG: kilogram | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1. Downgraded by 1 for inconsistency and unclear risk of bias.

2. Downgraded by 1 for inconsistency and high risk of bias.

3. Downgraded by 3 for very serious imprecision and inconsistency

4. Downgraded by 2 for small sample size and unclear risks of bias.

5. Downgraded by 2 for high risks of bias and imprecision.

3. 'Summary of findings' table: well‐being and psychological outcomes.

| Any interactive social media intervention compared with non‐interactive social media on well‐being | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults Settings: high and high‐middle income countries Intervention:iInteractive social media Comparison: non‐interactive social media | ||||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effect (95% CI) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Well‐being outcomes ‐ General well‐being and Quality of life | The mean well‐being score was 8.2 in the control group. | The mean well‐being score in the social media group was 3.77 points higher (from 1.15 lower to 6.48 points higher) where 14 points is the minimum possible score and 70 is the maximum. | SMD 0.46 (0.14 to 0.79) | 3792 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | Absolute effect calculated using Hutchesson 2018 |

| Psychological outcomes ‐ Distress and Depression | The mean depression score in the control group was 8.8. | The mean score in the social media group was 0.1 points lower (from 1.23 lower to 1.06 higher) on a scale using cut‐offs for which a score of 0–13 is considered minimal depression, 14–19 is mild, 20–28 is moderate, and 29–63 is severe. | SMD ‐0.01 (‐0.14 to 0.12) | 2070 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | Absolute effect calculated using Wan 2017 |

| Adverse events | Not reported in studies | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SMD: Standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1. Downgraded by 2 for unclear risks of bias and inconsistency.

2. Downgraded by 2 for unclear risks of bias and inconsistency.

Background

Description of the condition

Social networking platforms present an opportunity to reach large numbers of Internet users quickly with health information. For public health authorities, health promotion agencies, non‐governmental organisations, and others, social media offers an especially attractive opportunity to communicate with target audiences. These tools are generally easy and free to use and may allow organisations to reach various populations, providing they have Internet access, including rural and remote populations. These interventions also allow for tailoring to reach those who may usually be considered hard‐to‐reach. Furthermore, social media allows target audiences for health‐related interventions to share information and comments on topics that are of interest to them. In this way, organisations with relevant and informative health‐related campaigns may reach broader audiences through the social networks of users who follow them.

For the purpose of this review, we have defined social media as "activities, practices, and behaviours among communities of people who gather online to share information, knowledge, and opinions using conversational media…that make it possible to create and easily transmit content in the form of words, pictures, videos, and audios" (Safko 2012). We have outlined the types of interactive social media interventions that are eligible for this review in Table 5.

4. Types of interactive social media interventions.

| Social media format | Included | Excluded |

| Blogs and microblogs (e.g. Twitter) | If the intervention includes multi‐way interaction between users (e.g. Twitter that promotes discussion) | Blogs would almost always be excluded since they usually have limited interaction. One‐way messages and posts or direct contact with a healthcare provider. |

| Content communities (e.g. YouTube, Pinterest) | If the intervention includes multi‐way interaction | One‐way messages and posts or direct contact with a healthcare provider |

| Mobile applications (apps) | Apps that allow for communication and interaction with a group of people | Apps that allow a person to track and monitor their progress (e.g. weight loss, blood sugar, etc.) without a social component or apps used to communicate with a healthcare provider |

| Virtual social networks (e.g. Facebook, Odnoklassniki) | If the intervention includes multi‐way interaction | One‐way messages and posts or direct contact with a healthcare provider |

| Web pages and Wikis | If the web site/Wiki allows for multi‐way interaction | One‐way communication (e.g. education) |

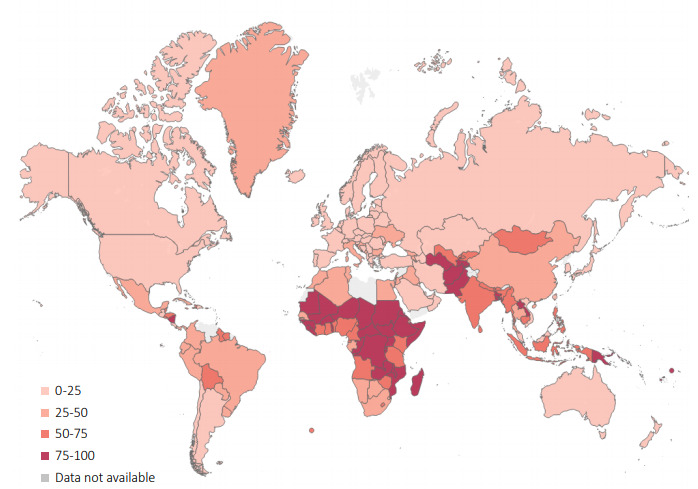

Globally, over 4.5 billion people use the Internet and over 3.8 billion use social media (We Are Social 2020). It is important to note that Internet access and usage vary within and between countries and world regions, as evidenced by the fact that the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) estimates that, as of 2019, total Internet users range from a high of 83% in Europe to a low of 28% in Africa (See Figure 1) (ITU 2019). Additionally, global estimates indicate Internet use among men is higher at 58% compared to only 48% of women (ITU 2019). In countries such as Canada and the USA, income has been shown to be a key source of digital inequality and is not only a significant determinant of Internet access, but also online activity level (Haight 2014). There is a risk that people who experience health inequity may face barriers to the use of social media, such as access, reading literacy and/or electronic health literacy (NCCHPC 2015; Welch 2016). Social media use is lower in low‐ and middle‐income countries. A 2014 survey of 32 emerging and developing nations found that those who read or speak English are more likely to access the Internet and Internet access and smartphone ownership rates were found to be greatest among the well‐educated and 18‐ to 34‐year‐olds (Pew Research Center 2015).

1.

Percentage of the population not using the internet (ITU 2019)

Health inequities are differences in health that are avoidable and unfair (Whitehead 2006). For the purpose of this review, we use the PROGRESS‐Plus framework to consider socially stratifying characteristics that are associated with inequities in health (O'Neill 2014; Welch 2016). Coined by Evans to describe characteristics that may contribute to health inequity, PROGRESS stands for Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender/sex, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, and Social capital (Evans 2003). 'Plus' represents personal characteristics that are associated with discrimination (e.g. age, disability), features of a relationship (e.g. smoking parents, excluded from school), time‐dependant relationships (e.g. leaving the hospital, respite care) and other circumstances that may be related to health inequities (Gough 2012). Social media interventions may inadvertently exacerbate health inequities if those who are most disadvantaged are excluded from participation due to issues such as lack of access or low literacy or electronic health literacy. Reducing health inequities is a major focus of both policy and research organisations from the local to the global level, such as the World Health Organization (WHO).

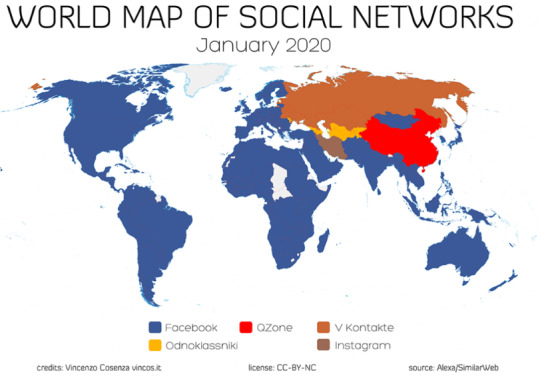

Social networking sites popular at the time of this review, like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, WeChat, WhatsApp, and YouTube, as well as related apps, are designed to promote the sharing of information and opinions. Figure 2 maps the most common social media platforms used in different countries around the world. These social networking sites allow information and opinions to be shared in the form of text, images, and video among friends, family, acquaintances, and associates as well as public figures, businesses, and other organisations with whom users associate by 'following' and 'liking' pages or accounts. Health‐specific social media interventions have utilised the most popular features and platforms of social media to provide support for people who share an interest in a particular health concern, such as survivors of cancer. There is evidence that social media use may create a sense of community among people, giving users a feeling of being supported and accepted (Dyson 2015). As noted by Vitak 2014, numerous researchers have found a positive correlation between social media use and social capital, "a construct that encompasses both actual and potential resources available within a given network". Social media may also be used as part of a wider campaign to change cultural norms and behaviours, such as increasing proper hand washing, as seen by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Handwashing: Clean Hands Save Lives campaign (https://www.cdc.gov/handwashing/heroes.html).

2.

World map of most commonly used social media platforms, 2020

However, with the speed and reach of social media‐based communication come attendant risks that may compromise health, such as the potential for equally rapid diffusion of misinformation or information that is not evidence‐based. For example, the anti‐vaccination Facebook page vactruth.com is 'liked' by almost 125,000 Facebook users and some of its posts are shared hundreds of times, meaning that its content may be seen by many more people than the number of page followers would suggest. Social media may be used to change cultural norms and behaviours in harmful ways, such as the use of social media in campaigns by the alcohol industry in countries such as Australia (Westberg 2016). In addition, the use of social media itself may be associated with adverse outcomes unrelated to the actual intervention or social media platform, such as perceived social isolation, depression and anxiety, and cyberbullying. There are also privacy concerns related to the unsolicited sharing of personal information or images (O'Keeffe 2011; Tromholt 2016; Primack 2017).

Description of the intervention

Health‐related interactive social media interventions for adults use social networking platforms to promote a message that may influence health service uptake, health behaviour change (such as smoking, physical activity, or diet), and health outcomes such as weight loss, depression, or quality of life.

Young 2015 provides an example of a social media‐based intervention aiming to improve a health behaviour among a vulnerable group: uptake of free HIV testing among men who have sex with men. This randomised trial was developed by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles in partnership with a local community clinic in Lima, Peru to test the efficacy of peer mentorship offered through Facebook. Investigators created non‐public intervention and control Facebook groups. The intervention groups included trained peer leaders who attempted to discuss with other members the importance of HIV prevention and testing. In contrast, the control group had no peer leaders, and participants simply received HIV testing information. Thus, intervention groups were subject to more interactive social media than control groups.

Another example of a social media intervention is described by Maher (Maher 2015). A free, 50‐day team‐based Facebook app called Active Team was developed by a team at the University of South Australia. As part of a randomised controlled trial, insufficiently active adult participants were recruited and allocated to either the intervention group or the control group. In the intervention group, participants were given a pedometer and encouraged to take 10,000 steps per day as part of a team of three to eight existing Facebook friends who the app encourages to engage in friendly rivalry and peer encouragement and support. The app includes a calendar for logging daily step counts, a dashboard showing step‐logging feedback on progress, awards, and gifts, and a team tally board so that users can monitor personal progress and their friends' progress. It also includes a team message board where team members can communicate and receive daily tips for increasing physical activity. Control group members were wait‐listed for the app‐based intervention and followed up with the same measurements as the intervention group.

How the intervention might work

For this review, we focused on 'interactive social media' in which the intervention allows for two‐way communication between peers or the public. This interactive functionality of social media offers a tremendous opportunity for increasing the reach of health interventions and enhancing a person's ability to engage in healthful behaviours. In addition to its potential to facilitate interactions between institutional providers and populations, social media allows lay people to create health‐focused groups to communicate with peers (Ali 2015; Myneni 2016). Furthermore, widespread use of mobile phones and other smart devices coupled with access to high‐speed Internet have considerably increased the ubiquitous functionality of social media while undermining limitations related to geographical locations, times, and social and economic status (Uskov 2015). In addition, because of the penetration of social media globally, people have experience using these interfaces that may allow them to take advantage of their functionality for finding, sharing, and using information.

Interactive social media has the potential to uphold health endeavours in various ways. Recent studies have reported the use of social media in strategies aimed at influencing individual health behaviours, informing health research, supporting health advocacy groups, and promoting health services (Brusse 2014; Seltzer 2015; Rhodes 2016; Sinnenberg 2016; Wong 2016). While the use of social media is common for supporting public health activities, very few organisations have reported consistent strategies describing how public health interventions sustained through social media have helped achieve their health equity goals (Thackeray 2012; Osborne 2013; Chauvin 2016; Ndumbe‐Eyoh 2016).

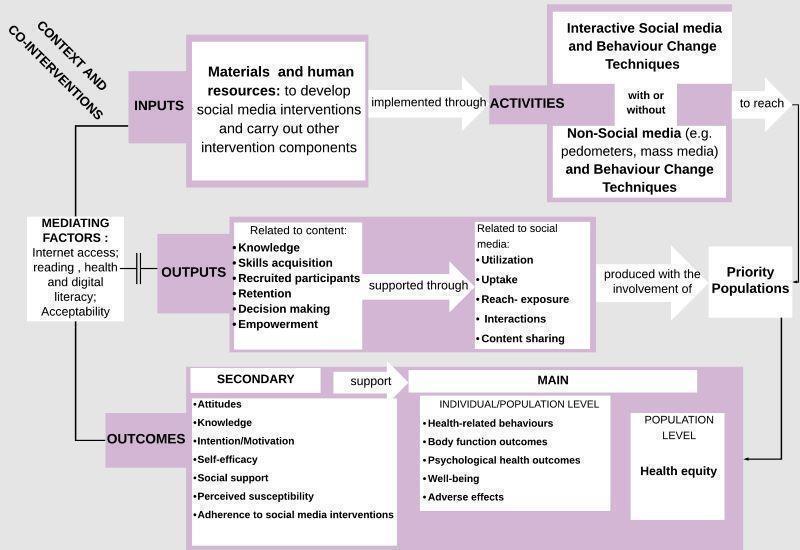

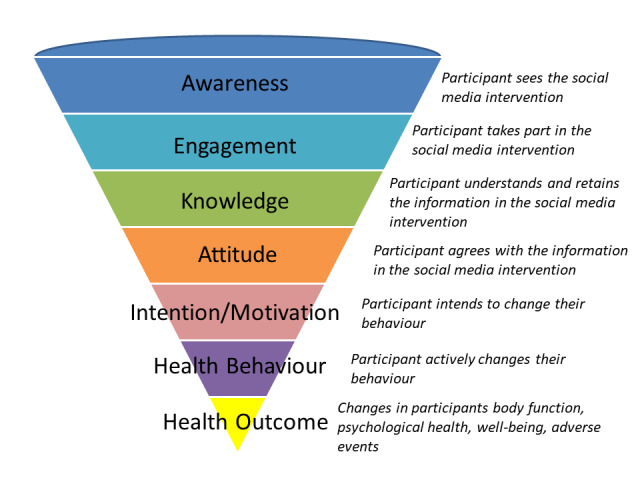

The logic model, developed by our team for this review, displayed in Figure 3 illustrates the components of interactive social media interventions. These include material and human resources and behaviour change techniques (BCTs) implemented through social media and non‐social media interventions as well as the expected intermediate outcomes (e.g. on knowledge, attitudes, self‐efficacy, motivation, emotions) leading to changes in health behaviours and, ultimately, health outcomes including health equity (Edberg 2015; Han 2017; Latkin 2015; Yoon 2014). We have also explored the potential for adverse effects (Rehfuess 2018; Rohwer 2016). We adapted the Funnel of Attrition to describe the mechanism of action of social media interventions on outcomes of interest (see Figure 4) (White 2018).

3.

Logic Model

4.

Funnel of Attrition

One of the reasons for using social media to deliver public health interventions is its capacity to build and reinforce social support for improving health outcomes (Osborne 2013; Vassilev 2014; Rhodes 2016; Rice 2016). Enabling social support through interactive social media has been linked to positive impacts on health outcomes by influencing knowledge, motivation, self‐efficacy (one's perceived ability to perform a behaviour), and other beliefs and cognitions towards health behaviours (Bandura 2000; Rhodes 2016; Rice 2016; Wong 2016). When used as a means for strengthening social networks, interactive social media may help promote public health and health equity by fostering collective efficacy (Greene 2011; Phua 2013; Di Bitonto 2015). Collective efficacy, a construct of social cognitive theory, is defined as "people's shared beliefs in their collective power to produce desired results" (Bandura 2000). Additional to the structure and the goal of the group, achieving group efficacy may be fostered by self‐efficacy, social comparison, or other specific rules governing the overall functioning of the group as one unit (Bandura 2000; MacAlister 2008; Ross 2010; Zhang 2016). Given the difficulty of anticipating the structure of participating communities in interactive social media interventions and the dynamic underpinning the functioning of online groups, collective efficacy was not included in the proposed logic model, however, we planned to collect information on collective efficacy, if it was reported.

Social media is often used in public health as a platform or setting for sharing knowledge, building skills, expanding the reach of public health interventions, fostering empowerment, and facilitating decision‐making among priority populations (Seltzer 2015; Hudnut‐Beumler 2016; Ndumbe‐Eyoh 2016). The logic model (Figure 3) acknowledges that interventions that involve social media are often complex interventions (Craig 2008), involving multiple components including offline intervention components to reinforce the message of the health‐related campaign.

Nevertheless, varied levels of interest in, access to, and acceptance of e‐technologies have been reported as affecting the uptake and effectiveness of interactive social media interventions for public health (Thackeray 2012; Antheunis 2013; Merolli 2013; Uskov 2015). Other studies have highlighted the mediating effect of characteristics such as social position, familiarity with social media, and literacy (reading, health, and digital literacy) in boosting the effect of interactive social media interventions on health outcomes (Korda 2013; Merolli 2013; Osborne 2013; Real 2015; Rice 2016). These elements have relevance for the replication of the interventions studied and should be factored into any description of the effects of interactive social media interventions on health outcomes.

Other concurrent public health initiatives, such as campaigns or community mobilisation, and the context in which interactive social media interventions are implemented may also impact the effectiveness of such interventions towards achieving health equity (Hudnut‐Beumler 2016; Ndumbe‐Eyoh 2016; Rice 2016). Thus, the effects of social media combined with campaigns should be interpreted with caution and their adaptation should be based on a thorough analysis of the needs of priority populations and assets available within the communities of interest.

Adverse and unintended effects from communication campaigns may arise due to stigmatisation and other reasons. For example, stigmatisation may be reported in interventions that use mechanisms such as self‐presentation and social comparison to promote healthy behaviours. Self‐presentation is described as "behavior that attempts to convey some information or image of oneself to other people" and it is often motivated by situational factors (Baumeister 1987). On the other hand, social comparison consists of drawing on others' behaviours to make comparison with one's performance (White 2006). Self‐presentation and social comparison have been reported as beneficial in interventions delivered online aimed at promoting healthy behaviours in the context of HIV prevention and physical activity, respectively (Byron 2013; Zhang 2016). While serving positive functions such as avoiding harms and encouraging healthy behaviours, self‐presentation and social comparison may also generate stigmatisation and embarrassment when strategies like manipulation and exemplification are used (Baumeister 1987; White 2006; Byron 2013). For example, someone may present themselves in such a way that they appear competent, dangerous, or morally virtuous (Baumeister 1987). Other adverse or unintended effects of communication campaigns can include confusion and misunderstanding about health risks and risk prevention and 'boomerang' (the reaction of the audience is the opposite of what was intended) (Cho 2007).

Fear of the consequences of privacy breaches and exposure of one's vulnerability through participating in the intervention may deter some individuals from enrolling. In order to avoid unwanted behaviours and to preserve the reputation of the interventions, organisers may establish consent processes that contain warnings to remove anybody deemed behaving inappropriately from the group. This situation may have the perverse effect of further excluding individuals who may have otherwise benefited from the public health intervention if the latter was not delivered through social media. Based on concerns over data security on social networking platforms and researchers' experience with an HIV education intervention delivered through social media, it has been suggested that health researchers familiarise themselves with current privacy settings available in order to help protect participants, and that they educate participants on how to better safeguard their privacy (Bull 2012). Thus, privacy breaches are one potential adverse effect that may be of special interest for the purpose of health interventions delivered online, especially for sensitive topics like sexual practices.

Lack of understanding of the research process and informed consent on the part of participants may influence participation in social media interventions and may differ for specific population groups (e.g. low literacy), especially in studies where this information was provided to participants online rather than with the direct involvement of research study personnel. For example, in the Harnessing Online Peer Education randomised trial (Young 2015), participants received information about the study and completed informed consent online. Chiu 2016 found that younger HOPE study participants, who generally had less experience with research studies than older participants, were less likely to indicate that they had understood the consent form and study process.

Why it is important to do this review

Although there are other systematic reviews of interactive social media interventions, these reviews have concluded that there is a gap in knowledge on the effects of modern social media (Maher 2014; Merolli 2013), and their narrower scope limited their ability to explore the mechanisms of action and possible effect modifiers across different type of behaviours (Laranjo 2015; Williams 2014). Heffernan 2017 have a forthcoming Cochrane title on whether social media influences attitudes and uptake of vaccines; however, this review will focus solely on vaccination, which has a set of issues that may not be generalisable to other areas of public health. Hamm 2014 reviewed the use and effectiveness of social media in child health. Thus, this review focused on adult social media users.

There are several Cochrane and non‐Cochrane systematic reviews on the effects of mass media interventions on topics as diverse as alcohol consumption, smoking prevention and cessation, HIV testing, mental health stigma, uptake of health services, and preventing non‐communicable diseases (Bala 2017; Carson‐Chahhoud 2017; Clement 2013; Grilli 2002; Mosdøl 2017; Siegfried 2014; Vidanapathirana 2005). Our review differs from these because we focused on interactive social media interventions that allow exchange of ideas, not mass media.

A number of reviews have examined equity impacts of health interventions, including those relating to physical activity (Humphreys 2013), prevention, management, or reduction of obesity (Bambra 2015), under‐nutrition (Kristjansson 2015), and healthy eating (McGill 2015). However, the effects of interactive social media interventions on disadvantaged populations have not been assessed in previous reviews. On one hand, interactive social media interventions have the potential to reach geographically dispersed populations, whereas on the other, there may be barriers such as the digital divide, language, literacy, acceptability, and risk of intervention‐generated inequities. Thus, it is important to assess the effects of interactive social media interventions on the health of disadvantaged populations.

Objectives

The main objective of this review was to assess the effects of interactive social media interventions aiming to change health behaviour for adults on health behaviours, physical and psychological health outcomes, and any reported adverse effects.

The secondary objectives were:

to assess the effects of interactive social media interventions that aim to change health behaviour across population subgroups (defined using PROGRESS‐Plus) to assess effects on health equity;

to explore heterogeneity of effects to identify other reasons for differences in effects.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Some types of social media, such as peer‐initiated social media, are not conducive to randomisation. Therefore, we limited this review to Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care recommended study designs (EPOC 2017a), as follows.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs): these studies consist of randomly assigning participants to receive one of the interventions studied. Participants may be assigned to interventions individually or by group (cluster‐RCTs). The interventions are usually described as treatment group (individuals who receive the intervention) and control group (individuals who do not receive the intervention).

Controlled before‐and‐after (CBA): these studies consist of measuring outcomes before and after the implementation of an intervention in both the treatment group and control group. Study investigators are not involved in the assignment of participants to either treatment or control group. Allocation is usually determined by other factors outside the control of the investigators. To be eligible, CBAs needed to have at least two intervention and two control sites.

Interrupted time series (ITS): these studies consist of measuring outcomes at multiple time points before and after an intervention ('the interruption') with the intent to capture whether the trends persist or there is a change in the outcomes measured after the intervention. When outcomes are assessed at regular intervals in the same participants, the ITS is called a repeated measures study (RMS). To be eligible, ITSs needed to have at least three data points before and three data points after the intervention.

RCTs with stepped‐wedge designs (treatments begun at different times for different groups of participants) were also eligible, however none were identified. We excluded all other study types.

Types of participants

A previous systematic review examined the use and effectiveness of social media in child health (Hamm 2014), therefore we only included members of the general population aged 18 years and older. We included studies with mixed populations (e.g. youth aged 15 to 24), if we were able to obtain disaggregated data for participants aged 18 years and older, or if the study reported that the population is mostly over 18 years of age (i.e. 70% or more of the population is 18 years of age or older). We included people from the general population, as well as participants with an identified health condition.

Given that we are also interested in the effect of social media interventions on health equity, we included studies that focused on or presented disaggregated data across 'PROGRESS‐Plus' characteristics.

Types of interventions

We used the Safko definition of social media: "activities, practices, and behaviours among communities of people who gather online to share information, knowledge, and opinions using conversational media…that make it possible to create and easily transmit content in the form of words, pictures, videos, and audios" (Safko 2012).

To be included in our review, the social media intervention must have allowed for interaction including two‐way communication between the user and peers. We excluded interventions that only offered one‐way communication as well as those that only offered one‐to‐one communication. We restricted inclusion to studies that focused on changing one or more behaviours. We assessed this using the following criteria:

the study purpose is focused on changing one or more behaviours (e.g. exercise, tobacco use); or

the web site/app or platform of the intervention tool described a goal of changing behaviour; or

the components of the intervention included a behaviour change technique that could be described using the Behaviour Change Technique taxonomy (Michie 2013; Presseau 2015).

We only included interactive social media interventions using commonly used social media tools (e.g. Facebook, Twitter) or those mimicking their interface (e.g. Quitnet) and related applications (apps). We excluded web‐based chat rooms designed by researchers or others since these are no longer used; they do not have a user interface like these other commonly used tools, and they have been synthesised in our overview (Welch 2016). Furthermore, because these web‐based chat rooms are not familiar to users, they require a learning curve and an extra effort to engage with them that is not required by tools such as Facebook or Twitter, with which users have familiarity and are likely already using. Examples of the types of interactive social media interventions to be included in this review are summarised in Table 5 (adapted from Welch 2016). We included peer‐initiated interventions as well as interventions initiated by organisations such as public health organisations or private organisations (e.g. Weight Watchers). We excluded studies assessing e‐health or telemedicine interventions that use technology to deliver health care. We also excluded studies that assess mobile health (e.g. apps that track clinical information with communication between an individual and their healthcare provider) and content that is transmitted unidirectionally (e.g. text message reminder interventions in which the recipient is unable to reply, podcasts in which health information is provided with no opportunity for two‐way communication) or which only allows for comments without sharing functionality, such as blogs. We excluded studies that assess online interventions that are based on exchange between a single care provider and a single participant such as online cognitive behavioural therapy, as they are covered within other reviews as telemedicine or e‐health interventions. Advertisements on social media (e.g. on Facebook) were ineligible if they did not have sharing functionality. We also excluded studies of virtual gaming interventions as we considered these to have a different mechanism of action.

We excluded studies of 'beta' interfaces that are aimed at assessing usability and improving the interface. These studies have limited applicability to understanding how social media can be used to influence health.

We included studies comparing interactive social media interventions with any comparison. We classified these as non‐interactive social media control, which included no intervention, usual care, or a non‐interactive social media‐based intervention. These would include, for example, paper‐ or in person‐based interventions or those delivered one‐on‐one via social networking platforms but without providing an opportunity for interaction amongst participants. We grouped these comparators together because we are interested in the effect of the interaction aspect of the social media interventions and are less interested in differences in effectiveness compared to 'no intervention' or 'in‐person' or paper‐based interventions. We also included active social media comparators if one arm received a more interactive social media intervention. Active comparators included those such as an unmoderated Facebook group compared to a moderated Facebook group. For these interventions, we considered the less interactive intervention to be the control.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Our main outcomes were health behaviours, impairments of body function, psychological health, well‐being, mortality, and adverse effects (e.g. stigmatisation, exclusion, or harmful health behaviours). We expected the different outcome measures to be different across studies and therefore we did not pre‐specify the outcome measures within each of our outcome domains. We included only those assessed using measurement tools which had been used previously and we extracted data from the longest follow‐up reported.

Health behaviours included alcohol consumption, breastfeeding, dietary changes, physical activity, medication adherence, illicit drug use, sexual behaviours, smoking, and seeking and using health services.

Body functions as defined by the WHO ICF (WHO 2002) such as body mass index (BMI), physical fitness, lung function, or asthma episodes.

Psychological health included measures of depression, stress, coping, and other measures.

Well‐being included measures of quality of life.

Adverse effects included any reported adverse outcomes or unintended consequences associated with interactive social media interventions, such as online harassment and privacy concerns related to discussing or otherwise revealing health issues or health status online, and ethical issues pertaining to participants' privacy.

Table 6 provides a description of the main outcomes as well as the types of outcomes and measures used for each.

5. Specific outcome measures for each outcome category.

| Main outcome categories | Outcome type | Outcome measures |

| 1. Health behaviours | Breastfeeding | Exclusive breastfeeding |

| Dietary behaviour | Diet quality; calorie intake; infant feeding style | |

| Physical activity | Steps per day; total weekly moderate‐vigorous activity; MET min per week; calories expended; attendance at physical activity sessions | |

| Medication adherence | Medication adherence | |

| Health screening | HIV testing; colorectal cancer screening | |

| Vaccination | Vaccination uptake | |

| Safe food handling | Safe food handling | |

| Sexual behaviours | Condom use | |

| Tobacco use | Smoking cessation; smoking rate | |

| 2. Body functions | Body mass index (BMI) | BMI |

| Weight | Weight; infant weight gain; weight control practices | |

| Blood glucose | HbA1c (Mmol/L) | |

| Fat mass | Fat mass | |

| Physical health status | Physical health status score | |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | Heart beats/minute | |

| Flu‐like illness | Flu‐like illness | |

| Dyspnoea | Dyspnoea score | |

| Insomnia | Insomnia | |

| 3. Psychological health | Depression | Depression score |

| Distress | Distress score | |

| Self‐worth | Self‐worth score | |

| 4. Well‐being | Quality of life | Quality of life score |

| General well being | Well‐being score |

BMI: body mass index; MET: metabolic equivalent

1. Outcome categories were prespecified and the outcome measures include what was reported in our studies.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included process outcomes related to the main outcomes of interest and included: attitudes, intention and motivation, knowledge, perceived susceptibility, self‐efficacy, and social support. We also included measures of adherence, as reported by the study authors. We classified adherence as 'good' when the study authors reported 70% or more of participants engaged with or adhering to the social media intervention.

To assess potential impact on health equity, we collected data on population‐specific effects across PROGRESS‐Plus characteristics, when available.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We adapted a search strategy developed by an information specialist (TR), who also worked on the search strategy for our overview (Welch 2016), and used this to search the following electronic databases: CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and PSYCINFO (all via OVID) and CINAHL via Ebsco). See Appendix 1 for all search strategies.

We searched for studies published between 2001 up to the end of 1 June 2020, because most of the commonly used social media platforms were developed in 2001 or later (e.g. Facebook, Twitter), and our previous overview showed no earlier studies using these commonly used social media applications (Welch 2016).

We did not include a language limit on the searches. Our team is able to collect data from studies in English, Spanish, Catalan, and French. If required, we would have sought help using Cochrane Task Exchange for studies in other languages.

Searching other resources

We searched for unpublished studies or reports using a focused search within Google and Web of Science, as well as searching websites of public health governmental and non‐governmental organisations, including the Public Health Agency of Canada, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Asian Development Bank, and the Inter‐American Development Bank up to the end of May 2020. We also searched clinical trials registries (ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)) for relevant studies. Finally, we searched the reference lists of our included studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies meeting our pre‐specified inclusion criteria. We screened the full text of studies identified as potentially relevant independently, in duplicate. We discussed and resolved disagreements by consensus or with a third member of the research team when necessary.

Data extraction and management

Two independent review authors extracted data on the population (including PROGRESS‐Plus characteristics, where applicable), study design, intervention, comparison, outcomes, context/setting, and implementation such as adherence and exposure to the social media‐based interventions and delivery of the intervention. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third member of the team.

Due to the magnitude of outcomes reported in our included studies, we implemented data extraction criteria to prioritise outcomes. Review authors extracted all reported adverse effects and one outcome per the remaining categories of impairment of body function, psychological health, well‐being, and health behaviours. For health behaviours, review authors prioritised outcomes that matched the stated purpose of the intervention. When more than one outcome was stated as the primary behaviour (e.g. physical activity and nutrition), both outcomes were extracted.

The outcome extraction criteria included: 1) use of a validated measurement tool, 2) author‐reported primary outcomes, 3) used in a sample size calculation, and 4) patient‐important outcome. We applied the same criteria to our secondary outcomes of knowledge, attitudes, motivation and self‐efficacy, and other theory‐based constructs related to behaviour change. If an outcome was measured using a validated scale, only the global score was extracted, if a global score was not provided, we extracted all subscales for that outcome. Outcomes were considered to be patient‐important if they affect a person’s daily functioning (e.g. mortality, disability, pain) rather than biomarkers (HbA1c, haemoglobin, etc.) (Boers 2014; WHO 2002). However, biomarkers were extracted when considered relevant to the intervention’s objective (e.g. diabetes management).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of Bias' tool for randomised trials, to collect details on how the study was designed and we judged the studies as low, unclear, or high risk of bias for each domain using the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Additionally, we included the domains of the EPOC 'Risk of bias' tool (EPOC 2017b), which also assesses whether baseline outcome measurements and baseline characteristics are similar and whether there was protection against contamination. We felt that these additional domains were required to ensure that the groups included in our study had similar social media knowledge and use which would affect their use of the interactive social media interventions, as well as similar behaviours at baseline, such as physical activity, since this is important for comparing behaviour changes. For controlled before‐after studies (CBAs) and interrupted time series studies (ITSs), we used the modified EPOC 'Risk of bias' tool (EPOC 2017b). Most of our outcomes were self‐reported and therefore we applied the same 'Risk of bias' ratings for all outcomes as we judged the risks to be similar.

For ITS studies, we used the Cochrane Handbook chapter on assessing bias in non‐randomised studies which includes additional domains: bias due to confounding, bias in selection of participants into the study, bias in classification of interventions, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing data, bias in measurement of the outcome, and bias in selection of the reported result (Sterne 2020).

Measures of treatment effect

We expected considerable heterogeneity in methods of measurement (e.g. self‐reported, computer‐collected) as well as measurement tools. In consultation with our clinical and statistical experts, we assessed whether it was appropriate to combine these different outcomes, based on conceptual similarity, using standardised mean differences (SMDs), as described in the analysis section below.

We expected that the mechanism of intervention would be similar for these different types of outcomes (see Figure 4), and, although we expected considerable heterogeneity in methods of measurement and in measurement tools, we planned to focus on broad outcome categories (e.g. health behaviours) with less emphasis on the specific outcome types (e.g. physical activity, tobacco use). However, when pooled, there was significant heterogeneity for our main outcomes and the effects could not be described in a meaningful way. In consultation with our knowledge users, we decided to present the results of the broad outcomes narratively, in Table 1 and present disaggregated data outcome type to ensure that the data are useful for those who may need to use these results. We have classified the broad outcomes as our 'main outcome categories' (e.g. health behaviours). These have been further described by 'outcome type' (e.g. breastfeeding, health screening, physical activity), and, when there were more than 10 studies reporting on an outcome type, we conducted an additional post hoc subgroup analysis by the specific outcome measure (e.g. steps per day, total weekly moderate‐vigorous activity). We have described these classifications in Table 6.

When a study included more than one measurement of our outcome classification above, we sought to assess which outcome was considered primary in the trial, based on whether it was named as a primary outcome, used in a sample size calculation or reported more prominently in the abstract or results. We recognised that this may not be possible since some studies have multiple measures of the same concept (e.g. we have identified over 15 measures of exercise behaviour modification such as frequency, intensity, and type of activity, and some studies reported three or more measures). Therefore, we documented how these decisions were made and reported on the additional outcomes available in the study in our Characteristics of included studies table.

As with the main outcomes, we expected heterogeneity in how our secondary outcomes were measured. We only included validated measures of these concepts. We classified all outcomes according to these categories, then conducted subgroup analyses according to the health behaviour each secondary outcome was related to (e.g. physical activity‐related self‐efficacy).

We analysed continuous outcomes as mean differences (MDs) in change from baseline, where possible. For some analyses we used standardised mean differences (SMDs) when different scales assessing the same outcome were used (e.g. well‐being). If baseline and end of study data were available, we calculated the change from baseline and associated standard deviation, using the methods in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020a). We analysed dichotomous outcomes, such as tobacco use, as risk ratios (RRs).

Unit of analysis issues

We analysed studies at the level of allocation. For cluster‐randomised trials where groups of people were allocated to interventions, we assessed these studies for unit of analysis errors. We detected unit of analysis issues for two of the seven cluster trials (Cheung 2015, Young 2013). For these studies, we identified an intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) from a similar trial and used it to inflate the standard deviation using the variance inflation factor for each intervention arm, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. For dichotomous outcomes, we used the methods in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to adjust the numerator and denominator for unit of analysis errors.

Dealing with missing data

We documented how the included studies handled missing data from participants in our data extraction form. We did not impute values for missing participants. If standard deviations were not reported, we calculated them using other methods such as the confidence interval and exact P values using the formulae in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, when possible (Higgins 2020a). For studies that met the eligibility criteria but did not report sufficient information for meta‐analyses, we contacted authors (e.g. to request standard deviations or numbers of participants, if not provided). We received additional data from two study authors (Duncan 2014, Greene 2013). If we did not receive a reply or the authors stated that the data could not be provided, we summarised the results narratively.

For dichotomous and continuous outcomes, we analysed using intention‐to‐treat, therefore we used the full number of randomised individuals as the denominator.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity with the I2 statistic and visual inspection of the forest plots. We explored heterogeneity using pre‐planned subgroup and sensitivity analyses, as described below.

Assessment of reporting biases

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots based on outcomes for each comparator with more than 10 studies. We were able to construct funnel plots for three of our main outcomes.

Data synthesis

As stated above, our initial aim was to group all outcomes according to the five domains described above: health behaviours, well‐being, body function, psychological outcomes, and adverse events. However, based on consultations with our advisory group, we have analysed the outcome types separately, grouped as appropriate, and in consultation with our content experts.

We used Review Manager software (RevMan 2020) to conduct meta‐analyses using random‐effects models. We assessed individually‐randomised trials and cluster‐randomised trials in the same analyses, taking into account unit of analysis issues as above, and we assessed CBA and ITS studies separately.

We conducted separate comparisons based on the type of control group. We classified control groups as non‐interactive social media control when the control was no intervention or a non‐interactive social media control, and we classified those which included an interactive social media comparator in the control arm as having 'active social media controls'. For these studies, we considered the most intense intervention (e.g. social media plus other components) to be the 'intervention' (e.g. compared to social media alone).

Finally, for studies in which the same social media intervention was provided in both arms, we considered the control to be non‐interactive social media (e.g. a Facebook group addressing the health condition of interest compared to a different Facebook group on another topic). In these studies, the outcomes of interest were related to the content for the intervention arm, and participants needed to be active on the social media platform of interest to be eligible. Therefore, the content provided in the control group would be similar to what the participants would be exposed to through their usual social media use so classifying the control groups as non‐interactive social media is appropriate.

We analysed continuous outcomes as standardised mean differences (SMDs), using change from baseline as the measure of effect. For our main outcomes, we re‐expressed these SMDs as mean differences (MDs) in natural units using the most representative study and the most commonly reported outcome for that category. We analysed dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RRs) , using the intention‐to‐treat analyses. We calculated the absolute % change as the difference in change divided by the baseline of the intervention group of the most representative study and have included this information in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

We recorded decisions about the classification of outcomes, methods of measurement and selection from amongst multiple measures of the same concept as described above and have reported these in the Characteristics of included studies table.

For studies with multiple arms, we selected the intervention arm considered to have the highest intensity of social media interaction (e.g. most frequent interaction or most frequent reminders). When more than one arm included a social media component, we combined these groups using the methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Similarly, for the control arm, we selected the arm that had the least exposure to an intervention (e.g. we selected 'usual care' over information provided via website). For interventions in which there were multiple intervention arms, we assessed those which included a social media component versus the arm designated by the authors as the 'control'.

We planned, but did not have enough data, to construct harvest plots to assess the presence of gradients in effects across sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other PROGRESS‐Plus characteristics for each outcome (Ogilvie 2008).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As above, for outcomes reported by 10 or more studies, we assessed heterogeneity to decide whether statistical meta‐analysis is appropriate. For meta‐analyses, we assessed heterogeneity using visual inspection of forest plots and the I2 statistic for heterogeneity.

We conducted the following planned subgroup analyses.

Type of population (general population, at‐risk, or with a health condition) since having a health condition may provide additional incentive for behaviour change (classified in Table 7).

Presence of co‐interventions such as campaigns that may magnify the impact of interactive social media interventions if combined.

6. Population subgroups.

| Population subgroup | Examples |

| Targeted at general population (universal) | Adults, college students, African American women, employees of a company, pregnant women |

| Targeted at those with a health condition or at‐risk of a health condition | Cancer patients/survivors, Type 2 diabetes, asthma, COPD/bronchitis/emphysema, HIV, trauma patients, rehabilitation patients, smokers, overweight/obese adults, men who have sex with men, low income mothers |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

We used the test for subgroup interaction in Review Manager 5.3 to perform these analyses.

We planned but were unable to conduct the following subgroup analyses.

Specific equity characteristics (sex/gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and age are considered the most important for this question). Our included studies did not provide enough information to conduct subgroup analyses based on equity but we have summarised the available information from studies which were aimed at a potentially disadvantaged group.

Behaviour change techniques (BCTs) used (i.e. we planned to assess each BCT used in at least two studies as a potential mediator of the effect). We did not assess effectiveness of BCTs and instead described which BCTs were used. We present the major results of that analysis here but have published the complete results in a separate paper to allow more detail (Simeon 2020).

Participants (e.g. smokers, under‐users). We did not have enough information for subgroup analyses for specific participant characteristics but have reported subgroup analyses on the populations of the studies in general.

Intensity of interactive social media intervention (e.g. high versus low frequency of interaction, or automatic reminder messages versus no reminders). We were unable to conduct subgroup analyses for intensity because this type of information could not be combined across studies. We have instead provided data for the adherence to the intervention, as reported by the study authors.

Through consultation with our knowledge users, we also presented disaggregated data by outcome type, such as different health behaviours (e.g. physical activity, calorie intake, tobacco use) and have disaggregated these further when there were more than 10 studies assessing these using the same outcome measure (e.g. daily step counts, weekly minutes of moderate‐vigorous physical activity) (see Table 6 for description).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analysis across risk of bias (i.e. allocation concealment and blinding of participants) by including only those assessed as low risk of bias. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis according to engagement with and adherence to the interactive social media intervention, defined as 70% or greater adherence as reported by the study authors.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We present the evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for our main outcomes for the comparison of interactive social media to non‐interactive social media control in a Table 1. We assessed the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome presented in our 'Summary of findings' tables using the GRADE methodology (Guyatt 2011). We presented our level of certainty as high, moderate, low, or very low. GRADE assessments were completed independently, in duplicate and disagreements were resolved with a third review author. We downgraded studies for imprecision when there was substantial heterogeneity and when the confidence intervals were wide. We downgraded due to risk of bias when the overall risks of bias of the studies were determined to be high or unclear based on whether any of the 'Risk of bias' domains were high (assessed as high overall) or unclear (Higgins 2020b). We would have downgraded for indirectness but did not judge there to be any differences between our studies. We assessed publication bias using funnel plots for outcomes with data from 10 or more studies.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search