Abstract

Background

This is the second update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2015 and last updated in 2018.

Appendectomy, the surgical removal of the appendix, is performed primarily for acute appendicitis. Patients who undergo appendectomy for complicated appendicitis, defined as gangrenous or perforated appendicitis, are more likely to suffer postoperative complications. The routine use of abdominal drainage to reduce postoperative complications after appendectomy for complicated appendicitis is controversial.

Objectives

To assess the safety and efficacy of abdominal drainage to prevent intraperitoneal abscess after appendectomy (irrespective of open or laparoscopic) for complicated appendicitis; to compare the effects of different types of surgical drains; and to evaluate the optimal time for drain removal.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Web of Science, the World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform, ClinicalTrials.gov, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, and three trials registers on 24 February 2020, together with reference checking, citation searching, and contact with study authors to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared abdominal drainage versus no drainage in people undergoing emergency open or laparoscopic appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. We also included RCTs that compared different types of drains and different schedules for drain removal in people undergoing appendectomy for complicated appendicitis.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Two review authors independently identified the trials for inclusion, collected the data, and assessed the risk of bias. We used the GRADE approach to assess evidence certainty. We included intraperitoneal abscess as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were wound infection, morbidity, mortality, hospital stay, hospital costs, pain, and quality of life.

Main results

Use of drain versus no drain

We included six RCTs (521 participants) comparing abdominal drainage and no drainage in participants undergoing emergency open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. The studies were conducted in North America, Asia, and Africa. The majority of participants had perforated appendicitis with local or general peritonitis. All participants received antibiotic regimens after open appendectomy. None of the trials was assessed as at low risk of bias.

The evidence is very uncertain regarding the effects of abdominal drainage versus no drainage on intraperitoneal abscess at 30 days (risk ratio (RR) 1.23, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.47 to 3.21; 5 RCTs; 453 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) or wound infection at 30 days (RR 2.01, 95% CI 0.88 to 4.56; 5 RCTs; 478 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). There were seven deaths in the drainage group (N = 183) compared to one in the no‐drainage group (N = 180), equating to an increase in the risk of 30‐day mortality from 0.6% to 2.7% (Peto odds ratio 4.88, 95% CI 1.18 to 20.09; 4 RCTs; 363 participants; low‐certainty evidence). Abdominal drainage may increase 30‐day overall complication rate (morbidity; RR 6.67, 95% CI 2.13 to 20.87; 1 RCT; 90 participants; low‐certainty evidence) and hospital stay by 2.17 days (95% CI 1.76 to 2.58; 3 RCTs; 298 participants; low‐certainty evidence) compared to no drainage.

The outcomes hospital costs, pain, and quality of life were not reported in any of the included studies.

There were no RCTs comparing the use of drain versus no drain in participants undergoing emergency laparoscopic appendectomy for complicated appendicitis.

Open drain versus closed drain

There were no RCTs comparing open drain versus closed drain for complicated appendicitis.

Early versus late drain removal

There were no RCTs comparing early versus late drain removal for complicated appendicitis.

Authors' conclusions

The certainty of the currently available evidence is low to very low. The effect of abdominal drainage on the prevention of intraperitoneal abscess or wound infection after open appendectomy is uncertain for patients with complicated appendicitis. The increased rates for overall complication rate and hospital stay for the drainage group compared to the no‐drainage group are based on low‐certainty evidence. Consequently, there is no evidence for any clinical improvement with the use of abdominal drainage in patients undergoing open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. The increased risk of mortality with drainage comes from eight deaths observed in just under 400 recruited participants. Larger studies are needed to more reliably determine the effects of drainage on morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Plain language summary

Drain use after an appendectomy for complicated appendicitis

Review question

Can drainage reduce the chance that an intraperitoneal abscess (a localised collection of pus in the abdomen or pelvis) will occur after an appendectomy (removal of the appendix by laparotomy (small cuts through the abdominal wall) or open appendectomy (removal of the appendix through a large incision in the lower abdomen)) for complicated appendicitis?

Why is this important?

'Appendicitis' refers to inflammation (the reaction of a part of the body to injury or infection, characterised by swelling, heat, and pain) of the appendix. Appendectomy, the surgical removal of the appendix, is performed primarily in individuals who have acute appendicitis. Individuals undergoing an appendectomy for complicated appendicitis, which is defined as gangrenous (soft‐tissue death) or perforated (burst) appendicitis, are more likely to suffer postoperative complications. The routine placement of a surgical drain to prevent intraperitoneal abscess after an appendectomy for complicated appendicitis is controversial and has been questioned.

What was found?

We searched for all relevant studies up to 24 February 2020.

We identified six clinical studies involving a total of 521 participants. All six studies compared drain use versus no drain use in individuals having an emergency open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. The included studies were conducted in North America, Asia, and Africa. The age of the individuals in the trials ranged from 0 years to 82 years. The analyses were unable to show a difference in the number of individuals with intraperitoneal abscess or wound infection between drain use and no drain use. The overall complication rate and death rate were higher in the drainage group than in the no‐drainage group. Hospital stay was longer (about two days) in the drain group than in the no‐drain group. None of the included studies reported on costs, pain, or quality of life. All of the included studies had shortcomings in terms of methodological quality or reporting of outcomes. Overall, the certainty of the current evidence is judged to be low to very low.

What does this mean?

Overall, there is no evidence for any improvement in patient outcomes with the use of abdominal drainage in individuals undergoing open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. The increased risk of complication and hospital stay with drainage is based on low‐certainty studies with small sample sizes. The increased risk of death with drainage comes from eight deaths observed in just under 400 people recruited to the studies. Larger studies are needed to more reliably determine the effects of drainage on complication and death outcomes.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Drainage compared to no drainage after open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis.

| Drainage compared to no drainage after open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis | |||||

| Patient or population: people undergoing emergency open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis Setting: hospital Intervention: drainage Comparison: no drainage | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with no drain use | Risk with drain use | ||||

|

Intraperitoneal abscess Follow‐up: 30 days |

107 per 1000 | 131 per 1000 (50 to 342) | RR 1.23 (0.47 to 3.21) | 453 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c |

|

Wound infection Follow‐up: 30 days |

254 per 1000 | 511 per 1000 (224 to 1000) | RR 2.01 (0.88 to 4.56) | 478 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c |

|

Morbidity Follow‐up: 30 days |

67 per 1000 | 445 per 1000 (142 to 1000) | RR 6.67 (2.13 to 20.87) | 90 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c |

|

Mortality Follow‐up: 30 days month |

6 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (7 to 101) | Peto OR 4.88 (1.18 to 20.09) | 363 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c |

| Hospital stay (days) | The mean hospital stay in the control groups was 4.60 days. | The mean hospital stay in the intervention groups was 2.17 days higher (1.76 days to 2.58 days higher). | MD 2.17days higher (1.76 higher to 2.58 higher) | 298 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Lowa,d |

| Hospital cost | Not reported | ||||

| Pain | Not reported | ||||

| Quality of life | Not reported | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the mean comparison group proportion in the studies. The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; Peto OR: Peto odds ratio; RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderatecertainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Lowcertainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very lowcertainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

aDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias. bDowngraded one level for severe inconsistency (substantial heterogeneity as indicated by the I2 statistic). cDowngraded one level for serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals). dDowngraded one level for serious imprecision (total population size was less than 400).

Background

This is the second update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2015, Cheng 2015, and last updated in 2018 (Li 2018).

Description of the condition

'Appendicitis' refers to inflammation of the appendix. Appendectomy, the surgical removal of the appendix, is performed primarily as an emergency procedure to treat acute appendicitis (Andersen 2005).

Acute appendicitis is the most common cause of acute abdominal pain (Andersen 2005; Jaschinski 2018; Rehman 2011; Wilms 2011). The overall incidence of acute appendicitis varies between 76 and 227 cases per 100,000 population per year in different countries (Andreu‐Ballester 2009; Buckius 2012; Ceresoli 2016; Coward 2016; Ferris 2017; Golz 2020; Lee 2010). The overall lifetime risk for acute appendicitis is approximately 7% to 8% in the USA, but as high as 16% in South Korea (Golz 2020; Lee 2010). It affects all age groups, with the highest incidence in individuals 10 to 20 years of age (Golz 2020; Wilms 2011).

The cause of acute appendicitis is an issue of considerable debate (Andersen 2005; Jaschinski 2018; Rehman 2011; Wilms 2011). Acute appendicitis may be associated with obstruction of the appendix lumen (the inside space of the appendix), which could result in increased intraluminal pressure with transmural tissue necrosis (Andersen 2005; Jaschinski 2018; Rehman 2011; Wilms 2011). Tissue necrosis is followed by bacterial invasion, which leads to inflammation of the appendix (Andersen 2005; Jaschinski 2018; Rehman 2011; Wilms 2011).

Acute appendicitis may be divided into two subgroups: simple appendicitis (e.g. early appendicitis, uncomplicated appendicitis) and complicated appendicitis (e.g. gangrenous appendicitis, perforated appendix without phlegmon or abscess, perforated appendicitis with phlegmon or abscess) (Andersen 2005; Cheng 2017; Simillis 2010). The proportion of complicated appendicitis varies between 15% and 35% in different case series (Boomer 2010; Cheng 2017; Coward 2016; Cueto 2006; Livingston 2007; Oliak 2000).

Description of the intervention

Individuals with complicated appendicitis usually require appendectomy to relieve symptoms and to avoid complications (Santacroce 2019). Appendectomy is one of the most common emergency surgical procedures worldwide (Andersen 2005; Jaschinski 2018; Rehman 2011; Santacroce 2019; Wilms 2011). There are two types of appendectomy: open appendectomy (removal of the appendix by laparotomy) and laparoscopic appendectomy (removal of the appendix by key‐hole surgery) (Cheng 2012a; Cheng 2015; Jaschinski 2018; Santacroce 2019; Yu 2017). Approximately 300,000 appendectomies are performed each year in the USA alone (Hall 2010).

The prognosis of complicated appendicitis is good (Santacroce 2019). The overall mortality rate of complicated appendicitis following appendectomy is less than 1% (Danwang 2020; Santacroce 2019). The most common complication after an appendectomy for complicated appendicitis is surgical site infection (e.g. wound infection, intraperitoneal abscess) (Andersen 2005; Cueto 2006). Patients with complicated appendicitis are more likely to suffer from surgical site infections than those with simple appendicitis (Danwang 2020). Recently published reviews report an approximately 10% incidence of surgical site infection (Danwang 2020; Santacroce 2019). Patients with surgical site infections usually present with a mild fever, abdominal pain, and bowel dysfunction (e.g. diarrhoea, constipation) (Santacroce 2019). Surgical site infections are associated with increased hospital stays and costs (Ban 2017; Berríos‐Torres 2017).

Various methods have been suggested for the prevention of surgical site infections, including antibiotic regimens, delayed wound closure, and the use of laparoscopic appendectomy (Andersen 2005; Danwang 2020; Duttaroy 2009; Jaschinski 2018). One of the most common and convenient interventions might be the application of surgical drains after appendectomy for patients with complicated appendicitis (Petrowsky 2004).

Surgical drains are used to remove blood, pus, and other body fluids from wounds (Durai 2009). There are two primary types of surgical drains: open and closed. An open drain is not air tight (Durai 2009; Gurusamy 2007a; Samraj 2007; Wang 2015). A closed drain consists of a tube that drains into a bag or bottle, the contents of which are air tight (Durai 2009; Gurusamy 2007a; Samraj 2007; Wang 2015).

How the intervention might work

The primary reasons for placing an abdominal drain after an appendectomy are as follows: (i) drainage of established intraperitoneal collection; (ii) prevention of further fluid accumulation; (iii) identification and drainage of faecal fistula (Allemann 2011; Gurusamy 2007a; Jani 2011).

The use of abdominal drainage can avoid the accumulation of intraperitoneal dirty collections, thereby reducing bacterial contamination of the surgical site (Greenall 1978; Jani 2011; Stone 1978; Tander 2003). Abdominal drainage has the theoretic potential to reduce the rate of surgical site infection (Greenall 1978; Jani 2011; Stone 1978; Tander 2003).

However, abdominal drainage may fail to prevent intraperitoneal abscess because a drain may become blocked and thus ineffective within a few hours after appendectomy (Greenall 1978; Haller 1973; Jani 2011; Magarey 1971). Additionally, the drain itself may act as a foreign body that interferes with wound healing and increases the risk of surgical site infection (Jani 2011; Magarey 1971; Murakami 2019; Stone 1978). The use of a drain may also increase the patient's length of hospital stay (Allemann 2011; Jani 2011; Stone 1978; Tander 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

The use of abdominal drainage after open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis is controversial (Narci 2007; Petrowsky 2004; Piper 2011): it may potentially decrease the risk of surgical site infection following open appendectomy, but it is also possible that it may have no therapeutic benefit and may be associated with negative outcomes (Murakami 2019; Mustafa 2016). The last version of this review was published in 2018 (Li 2018). Further randomised controlled trials evaluating the role of abdominal drainage after appendectomy for complicated appendicitis have been published since that review was conducted, and these studies have now been assessed for inclusion and presented in this update.

Objectives

To assess the safety and efficacy of abdominal drainage to prevent intraperitoneal abscess after appendectomy (irrespective of open or laparoscopic) for complicated appendicitis; to compare the effects of different types of surgical drains; and to evaluate the optimal time for drain removal.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (irrespective of sample size, language, or publication status) that compared (1) drain use versus no drain use, (2) open drain versus closed drain, or (3) different schedules for drain removal in participants undergoing appendectomy (irrespective of open or laparoscopic) for complicated appendicitis. We also included quasi‐RCTs (in which the allocation was performed on the basis of a pseudo‐random sequence, e.g. odd/even hospital number or date of birth, alternation), as described in Chapter 24 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Reeves 2021).

Types of participants

We included all people (irrespective of age, sex, or race) who underwent emergency open or laparoscopic appendectomy for complicated appendicitis (irrespective of gangrenous appendicitis, perforated appendix without phlegmon or abscess, or perforated appendicitis with phlegmon or abscess), and receiving antibiotic regimens after open appendectomy.

Types of interventions

Use of drain (irrespective of type or material) versus no drain.

Open drain versus closed drain.

Early versus late drain removal (no more than two days versus more than two days).

Types of outcome measures

.

Primary outcomes

Intraperitoneal abscess (e.g. intra‐abdominal abscess, pelvic abscess) (30 days).

Secondary outcomes

Wound infection (30 days).

Morbidity (overall complication rate; graded by the Clavien‐Dindo complications classification system) (30 days).

Mortality (30 days).

Hospital stay (days).

Hospital costs.

Pain (30 days, any validated score; Doleman 2018).

Quality of life (30 days, any validated score).

Morbidity was defined by the review authors and graded according to the Clavien‐Dindo classification of surgical complications (Clavien 2009). Surgical site infection has been defined and classified as superficial incisional, deep incisional, and organ/space surgical site infection by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Anderson 2014; Ban 2017; Berríos‐Torres 2017). We included intraperitoneal abscess (organ/space surgical site infection) as the primary outcome. We used wound infection (either superficial or deep incisional surgical site infection) as defined by the study authors.

Search methods for identification of studies

We designed the search strategy with the help of Sys Johnsen, Information Specialist of the Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group. Searches were conducted irrespective of language, year, or publication status on 24 February 2020.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases with no language or date of publication restrictions:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library) (2020, Issue 2) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1946 to 24 February 2020) (Appendix 2);

Embase (Ovid) (1974 to 24 February 2020) (Appendix 3);

Science Citation Index Expanded (Web of Science) (1900 to 24 February 2020) (Appendix 4);

World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (24 February 2020);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov/) (24 February 2020);

Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM) (1978 to 24 February 2020).

Searching other resources

We also searched the following databases on 24 February 2020:

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com/);

Chinese Clinical Trial Register (www.chictr.org/);

EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/).

We also searched the reference lists and citations of identified studies and meeting abstracts via the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) (www.sages.org/) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index to explore further relevant clinical trials. We planned to communicate with the authors of included RCTs for additional information.

Data collection and analysis

We conducted this systematic review according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021), Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR) (Chandler 2020).

Selection of studies

After completing the searches, we merged the search results using the software package Endnote X7 (reference management software; Endnote X7) and removed any duplicate records. Two review authors (CY, CN) independently scanned the title and abstract of every record identified by the search for potential inclusion in the review. We retrieved the full text for further assessment if the inclusion criteria were unclear from the abstract. We included eligible studies irrespective of whether they reported the measured outcome data. We detected duplicate publications by identifying common authors, centres, details of the interventions, numbers of participants, and baseline data, according to Chapter 4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2021). We intended to correspond with study authors to confirm whether the trial results had been duplicated, if necessary. We excluded papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria and listed the reasons for their exclusion. A third review author (DY) resolved any discrepancies between the two review authors by discussion.

Data extraction and management

We used a standard data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data that had been piloted on at least one study in the review. Two review authors (Li Zhe, Zhao L) extracted the following study characteristics from the included studies.

Methods: study design, total duration of study and run‐in period, number of study centres and location, study setting, withdrawals, date of study.

Participants: number of participants, mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition, diagnostic criteria, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria.

Interventions: intervention, comparison.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported.

Notes: funding for trial, notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

Two review authors (Li Zhe, Zhao L) independently extracted outcome data from the included studies. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by involving a third review author (DY). One review author (Li Zhe) copied across the data from the data collection form into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020). We double‐checked that the data were entered correctly by comparing the study reports with presentation of data in the systematic review.

A second review author (Zhao L) cross‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial reports.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CY, CN) independently assessed risk of bias in the included trials using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We assessed risk of bias for the following domains.

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective reporting bias

Other sources of bias (baseline imbalances)

We judged each domain as at low risk, high risk, or unclear risk of bias according to the criteria used in the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (see Appendix 5) (Higgins 2017). We considered a trial to be at low risk of bias if the trial was assessed as at low risk of bias across all domains. Otherwise, we considered trials at unclear or high risk of bias regarding one or more domains as at high risk of bias overall. Any differences in opinion were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third review author (DY) to reach consensus if necessary.

The results of the 'Risk of bias' assessment are presented in a 'Risk of bias' graph and 'Risk of bias' summary, generated by Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020).

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to the published protocol (Cheng 2012b), and reported any deviations from it in the Differences between protocol and review section of the systematic review.

Measures of treatment effect

We performed the meta‐analyses using the software package Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020). For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio with 95% confidence interval (CI) (Deeks 2021). In the case of rare events (e.g. mortality), we calculated the Peto odds ratio (Deeks 2021). For continuous outcomes, we calculated the mean difference with 95% CI (Deeks 2021). For continuous outcomes with different measurement scales in different randomised clinical trials, we would calculate standardised mean differences with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant. We intended to analyse data using the generic inverse‐variance method in Review Manager 5 for cluster randomised trials (Higgins 2021). We intended to analyse only data from the first period of treatment for cross‐over trials (Higgins 2021). We intended to combine groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison for trials with multiple intervention groups. We did not encounter any cluster‐randomised trials, cross‐over trials, or trials with multiple intervention groups in this update.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the original investigators to request further information in the case of missing data; however, we received no reply and thus used only the available data in the analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We described heterogeneity in the data using the Chi2 test (Deeks 2021). We considered a P value of less than 0.05 to be statistically significant heterogeneity (Deeks 2021). We also used the I2 statistic to measure the quantity of heterogeneity. In case of statistical heterogeneity or clinical heterogeneity (or both), we performed meta‐analysis but interpreted the result cautiously and investigated potential sources of the heterogeneity. We explored clinical heterogeneity by comparing the characteristics of participants, interventions, controls, outcome measures, and study designs in the included studies. We planned to undertake the following approaches for explanation and solution:

check again that the data were correct;

change the effect measure;

perform analysis using the random‐effects model;

perform sensitivity analysis by excluding potentially biased trials;

perform subgroup analysis or meta‐regression;

present all trials and provide a narrative discussion.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to perform and examine a funnel plot to explore possible publication bias (Doleman 2020). However, as the number of included trials was less than 10, we did not produce any funnel plots, as recommended in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2017).

Data synthesis

We performed the meta‐analyses using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2020). For all analyses, we employed the random‐effects model for conservative estimation, except for the Peto odds ratio, which only has a fixed‐effect method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We intended to perform the following subgroup analyses.

Trials at low risk of bias versus trials at high risk of bias.

Laparoscopic appendectomy versus open appendectomy.

Adults versus children.

Gangrenous appendicitis versus perforated appendicitis.

One type of appendix stump closure versus another.

We did not perform any of our planned subgroup analyses as there was an insufficient number of trials included in the review.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed the planned sensitivity analyses, as follows.

Changing statistics amongst risk ratios, risk differences, and odds ratios/Peto odds ratios for dichotomous outcomes.

Changing statistics between mean difference and standardised mean differences for continuous outcomes.

Excluding RCTs at high risk of bias.

We did not perform the planned sensitivity analysis by excluding non‐English literature because none of the studies were published in languages other than English. We performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis in response to peer‐reviewer for the primary outcome (intraperitoneal abscess) by excluding quasi‐RCTs to determine whether the conclusions were robust to the decisions made during the review process.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We evaluated the certainty of evidence using the GRADE approach for each outcome (Schünemann 2021), including intraperitoneal abscess, wound infection, morbidity, mortality, hospital stay, hospital costs, pain, and quality of life.

We presented the certainty of evidence in a 'Summary of findings' table for the following comparison.

Drainage versus no drainage.

We justified, documented, and incorporated our judgements regarding the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low, or very low) into the reporting of results for each outcome. The certainty of evidence could be downgraded by one level (serious concern) or two levels (very serious concerns) based on the following: risk of bias; inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity, inconsistency of results); indirectness (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes); imprecision (wide CIs, single trials); and publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies ; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

We searched for studies on 24 February 2020.

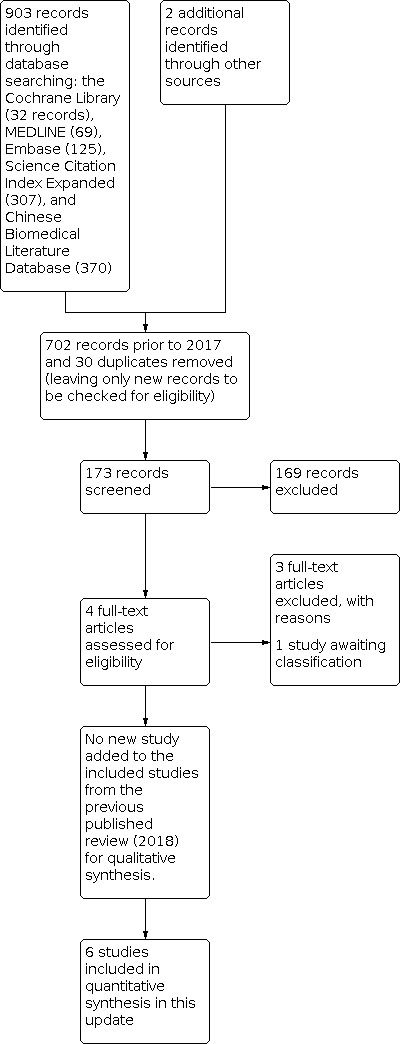

In this updated review, we identified 903 records through the electronic searches of the Cochrane Library (32 records), MEDLINE (Ovid) (69 records), Embase (Ovid) (125 records), Science Citation Index Expanded (Web of Science) (307 records), and Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM) (370 records). We identified two records by scanning reference lists of the identified RCTs (Haller 1973; Johnson 1993). Of the total 905 records, 732 records had already been assessed for the second version of this review (702 records prior to 2018 and 30 duplicates). Of the remaining 173 records, we excluded 169 clearly irrelevant records after reading titles and abstracts. We retrieved the remaining four records in full for further assessment (Abdulhamid 2018; Afzal 2017; Fujishiro 2020; Miranda‐Rosales 2019). We excluded three of these as they were non‐randomised studies (Abdulhamid 2018; Fujishiro 2020; Miranda‐Rosales 2019). We assessed the study by Afzal 2017 as awaiting classification because the data could not be verified.

We identified six trials (521 participants) comparing drainage with no drainage for people undergoing open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis (Dandapat 1992; Haller 1973; Jani 2011; Mustafa 2016; Stone 1978; Tander 2003). The studies randomised 262 participants to the drainage group and 259 participants to the no‐drainage group. With so few participants, all of the analyses were underpowered. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

In the last published version of this review (Li 2018), we included six trials that were published between 1973 and 2016 (Dandapat 1992; Haller 1973; Jani 2011; Mustafa 2016; Stone 1978; Tander 2003). We did not identify any new trials in the current update. All six trials were completed trials and all provided data for the analyses. For details of the trials, see Characteristics of included studies. Four trials were RCTs (Dandapat 1992; Jani 2011; Mustafa 2016; Tander 2003), and two trials were quasi‐RCTs (Haller 1973; Stone 1978). All six trials compared drain use with no drain use for patients undergoing open appendectomy. The studies were conducted in the USA (Haller 1973; Stone 1978), India (Dandapat 1992), Kenya (Jani 2011), Pakistan (Mustafa 2016), and Turkey (Tander 2003). The age of the individuals in the trials varied between 0 years and 82 years. The mean proportion of females varied between 19% and 44%. There was no difference in the characteristics of participants between intervention and control groups in any of the trials. Overall, 32 (6.1%) participants had gangrenous appendicitis; 11 (2.1%) participants had appendiceal abscess; and 478 (91.8%) participants had perforated appendicitis in the trials. All participants received antibiotic regimens after open appendectomy. The outcomes measured were intraperitoneal abscess, wound infection, morbidity, mortality, and hospital stay.

Excluded studies

We excluded one RCT because it focused on extraperitoneal wound drainage (Everson 1977), and one RCT that compared peritoneal lavage with abdominal drainage (Toki 1995). We excluded two RCTs because not all participants received antibiotics (several participants received antibiotic regimens after appendectomy, whilst other participants did not) (Greenall 1978; Magarey 1971). The remaining excluded studies were not RCTs (Abdulhamid 2018; Allemann 2011; Al‐Shahwany 2012; Beek 2015; Ezer 2010; Fujishiro 2020; Johnson 1993; Miranda‐Rosales 2019; Narci 2007; Piper 2011; Song 2015).

Studies awaiting classification

We assessed one study as awaiting classification (Afzal 2017), as the study data could not be verified. In this study 68 participants with perforated appendicitis were randomised to drainage group or no‐drainage groups. Afzal 2017 was performed in Pakistan. The outcomes reported were wound infection and hospital stay.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias of the included studies is shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. None of the included trials was judged to be at low risk of bias.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We assessed random sequence generation as at unclear risk of bias in four trials (Dandapat 1992; Jani 2011; Mustafa 2016; Tander 2003), and high risk of bias in two trials where participants were randomised using pseudo‐random sequences (odd/even hospital number) (Haller 1973; Stone 1978). We assessed allocation concealment as at an unclear risk of bias in all six trials (Dandapat 1992; Haller 1973; Jani 2011; Mustafa 2016; Stone 1978; Tander 2003).

Blinding

We assessed both blinding of participants and personnel and blinding of outcome assessment as at unclear risk of bias in all six trials (Dandapat 1992; Haller 1973; Jani 2011; Mustafa 2016; Stone 1978; Tander 2003).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed all six trials as at low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Dandapat 1992; Haller 1973; Jani 2011; Mustafa 2016; Stone 1978; Tander 2003).

Selective reporting

The trial protocols were not available for any of the included trials. Five trials reported all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified (Dandapat 1992; Haller 1973; Jani 2011; Stone 1978; Tander 2003). One trial was at high risk of selective reporting bias as the study failed to include results for a key outcome (intraperitoneal abscess) that would be expected to have been reported for such a study (Mustafa 2016).

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed all six trials as at low risk of other bias as no baseline imbalances were observed (Dandapat 1992; Haller 1973; Jani 2011; Mustafa 2016; Stone 1978; Tander 2003).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Use of drain versus no drain

Six studies (521 participants) compared drain use with no drain use for people undergoing open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis (Dandapat 1992; Haller 1973; Jani 2011; Mustafa 2016; Stone 1978; Tander 2003). The studies randomised 262 participants to the drainage group and 259 participants to the no‐drainage group. See: Table 1.

Primary outcome

Intraperitoneal abscess

We identified five trials (453 participants) reporting intraperitoneal abscess. The rate of intraperitoneal abscess was 13.1% in the drainage group and 10.7% in the no‐drainage group. There was no difference in the rate of intraperitoneal abscess (including intra‐abdominal abscess and pelvic abscess) between the groups (risk ratio (RR) 1.23, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.47 to 3.21; P = 0.67; Analysis 1.1). Heterogeneity was statistically significant: I2 = 63%, P = 0.03. It was unclear whether abdominal drainage reduced the rate of intraperitoneal abscess as the certainty of the evidence was downgraded to very low due to risk of bias, serious imprecision, and serious inconsistency.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Drain use versus no drain use, Outcome 1: Intraperitoneal abscess

Secondary outcomes

Wound infection

We identified five trials (478 participants) reporting wound infection. The rate of wound infection was 51.1% in the drainage group and 25.4% in the no‐drainage group. The wound infection rate was higher in the drainage group than in the no‐drainage group (RR 2.01, 95% CI 0.88 to 4.56; P = 0.10; Analysis 1.2). Heterogeneity was statistically significant: I2 = 86%, P < 0.001. It was unclear whether abdominal drainage increased the rate of wound infection as the certainty of the evidence was downgraded to very low due to risk of bias, serious imprecision, and serious inconsistency.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Drain use versus no drain use, Outcome 2: Wound infection

Morbidity

We identified one trial (90 participants) reporting overall complication rate (morbidity). The overall complication rate defined according to the Clavien‐Dindo classification was 44.5% in the drainage group and 6.7% in the no‐drainage group. The overall morbidity may be higher in the drainage group than in the no‐drainage group (RR 6.67, 95% CI 2.13 to 20.87; P = 0.001; Analysis 1.3). We downgraded the certainty of the evidence to low due to risk of bias and serious imprecision.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Drain use versus no drain use, Outcome 3: Morbidity

Mortality

We identified four trials (363 participants) reporting mortality. There were seven deaths in the drainage group (183 participants) compared to one in the no‐drainage group (180 participants). The death rate was 2.7% in the drainage group and 0.6% in the no‐drainage group. Mortality may be higher in the drainage group than in the no‐drainage group (Peto odds ratio 4.88, 95% CI 1.18 to 20.09; P = 0.03; Analysis 1.4). There was no evidence of heterogeneity: I2 = 0%, P = 0.95. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence to low due to risk of bias and serious imprecision.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Drain use versus no drain use, Outcome 4: Mortality

Hospital stay

We identified three trials (298 participants) reporting hospital stay. The mean length of hospital stay was 6.6 days in the drainage group and 4.6 days in the no‐drainage group. Hospital stay may be longer in the drainage group than in the no‐drainage group (mean difference 2.17 days, 95% CI 1.76 to 2.58; P < 0.001; Analysis 1.5). There was no evidence of heterogeneity: I2 = 0%, P = 0.75. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence to low due to risk of bias and serious imprecision.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Drain use versus no drain use, Outcome 5: Hospital stay

Hospital costs

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Pain

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Quality of life

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Open drain versus closed drain

There were no RCTs comparing open drain versus closed drain for complicated appendicitis.

Early versus late drain removal

There were no RCTs comparing early versus late drain removal for complicated appendicitis.

Reporting biases

We did not create funnel plots to assess reporting biases because the number of included trials was less than 10 (Sterne 2017).

Sensitivity analysis

We observed no change in the results by calculating risk differences and odds ratios/Peto odds ratios for dichotomous outcomes, calculating standardised mean differences for continuous outcomes, or excluding RCTs at high risk of bias. We observed no change in the outcome intraperitoneal abscess by excluding two quasi‐RCTs (Haller 1973; Stone 1978).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Six studies with a total of 521 participants contributed data to the primary outcome of this review. For the comparison of abdominal drainage versus no drainage in participants undergoing emergency open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis, we are uncertain whether abdominal drainage reduces the incidence of intraperitoneal abscess or wound infection. Furthermore, low‐certainty trials showed that abdominal drainage increased overall morbidity and length of hospital stay. There were seven deaths in the drainage group compared to one in the no‐drainage group. Low‐certainty evidence showed that abdominal drainage may increase the risk of death.

The primary reason for the placement of a drain after appendectomy is to prevent intraperitoneal abscess (e.g. intra‐abdominal abscess, pelvic abscess). We found that the routine use of abdominal drainage after complicated appendectomy did not reduce the incidence of intraperitoneal abscess; the possible reasons for this are as follows. First, this review included six trials with only 262 participants undergoing abdominal drainage, and therefore may not have had the statistical power to detect any clinically meaningful difference between abdominal drainage and no drainage for the prevention of intraperitoneal abscess, even if such a difference was present. In addition, where differences were detected, confidence in these results is low, as the small numbers mean they could be spurious results, and the impact of a bias can be exacerbated in underpowered analyses. It is thus unclear whether routine abdominal drainage has any effect on the prevention of intraperitoneal abscess in individuals undergoing open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All of the included trials involved participants undergoing emergency open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis (e.g. gangrenous appendicitis and perforated appendicitis). The majority (91.8%) of participants had perforated appendicitis with local or general peritonitis. The results of this review are thus applicable to individuals undergoing emergency open appendectomy for perforated appendicitis.

Quality of the evidence

None of the included trials was at low risk of bias. The trials included within each comparison were too few to assess inconsistency and publication bias. Direct comparisons of different types of drain were not available; only the comparison for each type of drain with no drain was evaluated. In theory, these trials could allow indirect comparisons of the effect of different types of drain; however, small sample sizes and methodological flaws of the trials precluded such indirect comparison. The CIs for the majority of outcomes were wide, indicating that the estimates of effect obtained are imprecise. Overall, we considered the certainty of the evidence to be low to very low (Table 1).

Potential biases in the review process

There were several potential biases of note present in the review process. First, we included only six trials with a total of 521 participants in the review, thus there is a lack of data on this topic to date. Second, due to the small number of included trials, we were unable to create funnel plots to assess potential publication bias. Third, we did not perform any of our planned subgroup analyses to assess heterogeneity given the small number of trials included for each outcome. Additionally, patient selection processes and blinding were unclear for most studies. We contacted the original investigators to request further information but did not receive any replies. Moreover, an important source of bias in the included studies was the use of antibiotic regimens (Andersen 2005). For example, the type and length of antibiotic therapy were important confounding factors for various outcomes (e.g. intraperitoneal abscess, wound infection) (Andersen 2005). However, the type and length of antibiotic therapy varied a great deal in different trials. It was difficult to perform subgroup analyses to assess the heterogeneity. Finally, the imputation of the standard deviation for hospital stay from the range may also have introduced bias into the review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There is increasing evidence in Cochrane Reviews that routine abdominal drainage after various abdominal operations is not essential (Gurusamy 2007a; Gurusamy 2007b; Gurusamy 2013; Rolph 2004; Wang 2015; Zhang 2018). The routine use of surgical drains has been questioned in other areas, including thyroid, gynaecological, and orthopaedic surgeries (Charoenkwan 2017; Gates 2013; Parker 2007; Samraj 2007).

The systematic review by Petrowsky and colleagues, Petrowsky 2004, included five trials comparing drain use with no drain use in patients undergoing appendectomy for complicated appendicitis (Dandapat 1992; Greenall 1978; Haller 1973; Magarey 1971; Stone 1978). Two of these five trials, in which antibiotic regimens were used in a non‐random manner (some participants received antibiotic regimens after appendectomy, whereas other participants did not), were not included in this review (Greenall 1978; Magarey 1971). Petrowsky and colleagues concluded that abdominal drainage did not reduce postoperative complications and appeared to be harmful with respect to the development of faecal fistula (Petrowsky 2004). Consequently, these authors recommended that abdominal drainage should be avoided at any stage of appendicitis (Petrowsky 2004). Our review has not reached any definitive conclusions, in part because the number of participants included is low for detecting a benefit on intraperitoneal abscess. A sample size of 2570 would be required to detect an absolute reduction in the intraperitoneal abscess rate of 2% (from 10% to 8%) at 80% power and an alpha‐error set at 0.05.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The effect of abdominal drainage for the prevention of intraperitoneal abscess after open appendectomy is uncertain for individuals with complicated appendicitis due to the very low certainty of evidence. The effect on wound infection after open appendectomy is also uncertain for individuals with complicated appendicitis. The increased overall complication rate and hospital stay for the drainage group compared to no‐drainage group was based on low‐certainty evidence. The excess mortality in the drainage group was observed from eight deaths in total across the studies. There is no evidence for any clinical improvement with the use of abdominal drainage in individuals undergoing open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis.

Implications for research.

There is an urgent need for high‐certainty trials. More studies are needed to assess drain versus no drain use in laparoscopic appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. Investigators should employ adequate methods of randomisation, allocation concealment, and blinding of outcome assessors to reduce the risk of bias. Studies with larger sample sizes will help ensure that there is adequate power to detect effects on morbidity outcomes and provide further information on mortality. Future trials should specify a set of criteria for antibiotics use and define all of the patient‐important outcomes (e.g. pain, quality of life) more accurately and report them in accordance with validated criteria.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 February 2020 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Searches updated 24 February 2020. No new randomised controlled trials identified and included in analyses. Conclusions remain unchanged. |

| 24 February 2020 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 24 February 2020. No new randomised controlled trials identified and included in analyses. Review updated accordingly, with one study awaiting classification. Author byline changed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 10, 2012 Review first published: Issue 2, 2015

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 July 2017 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 30 June 2017, and review updated accordingly with one new randomised controlled trial included. Author byline changed. This updated review furthermore included Trial Sequential Analysis (TSA) for the primary outcome, aiming to reduce the risk of random error in the setting of repetitive testing of accumulating data, thereby improving the reliability of conclusions. |

| 30 July 2017 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Searches updated 30 June 2017. One new randomised controlled trial with 68 participants identified and included in the analyses. Conclusions remain unchanged. |

| 11 December 2014 | Amended | The authors changed the title in the review stage. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Cochrane Colorectal Cancer editorial office, Dr Kristoffer Andresen and Ms Malene agnete A Højland, who assisted in the development of the updated review, and Dr Sys Johnsen and Dr Sara Hallum, who developed the search strategy. We would also like to thank editors and peer referees (Brett Doleman, Kenneth Thorsen) for their valuable comments on this updated review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for CENTRAL (2020, Issue 2)

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Appendectomy] explode all trees

#2 MeSH descriptor: [Appendicitis] explode all trees

#3 appendectom* or appendic*:ti,ab,kw

#4 (#1 or #2 or #3)

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Drainage] explode all trees

#6 MeSH descriptor: [Suction] explode all trees

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Negative‐Pressure Wound Therapy] explode all trees

#8 ((negative pressure or negative‐pressure) near/3 (dressing* or therap*)):ti,ab,kw

#9 ((vacuum‐assisted or vacuum assisted) near/3 closure*):ti,ab,kw

#10 (drain* or suction*):ti,ab,kw

#11 (#5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10)

#12 (#4 and #11)

Appendix 2. Search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) (1946 to 24 February 2020)

1. exp Appendectomy/

2. exp Appendicitis/

3. (appendectom* or appendic*).mp.

4. 1 or 2 or 3

5. exp Drainage/

6. exp Negative‐Pressure Wound Therapy/

7. exp Suction/

8. ((negative pressure or negative‐pressure) adj3 (dressing* or therap*)).mp.

9. ((vacuum‐assisted or vacuum assisted) adj closure*).mp.

10. (drain* or suction*).mp.

11. 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10

12. 4 and 11

13. randomized controlled trial.pt.

14. controlled clinical trial.pt.

15. randomized.ab.

16. placebo.ab.

17. clinical trials as topic.sh.

18. randomly.ab.

19. trial.ti.

20. 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19

21. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

22. 20 not 21

23. 12 and 22

Appendix 3. Search strategy for Embase (Ovid) (1974 to 24 February 2020)

1. exp appendectomy/

2. exp acute appendicitis/

3. exp appendicitis/

4. (appendectom* or appendic*).mp.

5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

6. exp drain/

7. exp abscess drainage/

8. exp abdominal drainage/

9. exp wound drainage/

10. exp surgical drainage/

11. exp vacuum assisted closure/

12. exp suction/

13. ((negative pressure or negative‐pressure) adj3 (dressing* or therap*)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword]

14. ((vacuum‐assisted or vacuum assisted) adj closure*).mp.

15. (drain* or suction*).mp.

16. 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15

17. 5 and 16

18. CROSSOVER PROCEDURE.sh.

19. DOUBLE‐BLIND PROCEDURE.sh.

20. SINGLE‐BLIND PROCEDURE.sh.

21. (crossover* or cross over*).ti,ab.

22. placebo*.ti,ab.

23. (doubl* adj blind*).ti,ab.

24. allocat*.ti,ab.

25. trial.ti.

26. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.sh.

27. random*.ti,ab.

28. 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27

29. (exp animal/ or exp invertebrate/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans or man or men or wom?n).ti.)

30. 28 not 29

31. 17 and 30

Appendix 4. Search strategy for Science Citation Index Expanded (1900 to 24 February 2020)

#1 Topic=(appendectom* OR appendic*)

#2 Topic=(drain* OR suction* OR negative pressure wound therap* OR negative‐pressure wound therap* OR vacuum‐assisted closure OR vacuum assisted closure*)

#3 Topic=(random* OR control* OR RCT* OR placebo OR trial* OR group*)

#4 (#1 AND #2 AND #3)

Appendix 5. Criteria for judging risk of bias in the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence | |

| Criteria for a judgement of 'low risk' of bias | The investigators described a random component in the sequence generation process such as:

*Minimisation may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random. |

| Criteria for a judgement of 'high risk' of bias | The investigators described a non‐random component in the sequence generation process. Usually, the description would involve some systematic, non‐random approach, such as:

Other non‐random approaches occur much less frequently than the systematic approaches mentioned above and tend to be obvious. They usually involve judgement or some method of non‐random categorisation of participants, such as:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'unclear risk' of bias | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit a judgement of 'low risk' or 'high risk' |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment | |

| Criteria for a judgement of 'low risk' of bias | Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not have foreseen assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'high risk' of bias | Participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly have foreseen assignments and thus introduced selection bias, such as allocation based on:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'unclear risk' of bias | Insufficient information to permit judgement of 'low risk' or 'high risk'. This is usually the case if the method of concealment was not described or not described in sufficient detail to permit a definitive judgement, such as if the use of assignment envelopes was described, but it remained unclear whether envelopes were sequentially numbered, opaque, and sealed. |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study | |

| Criteria for a judgement of 'low risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'high risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'unclear risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors | |

| Criteria for a judgement of 'low risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'high risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'unclear risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature, or handling of incomplete outcome data | |

| Criteria for a judgement of 'low risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'high risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'unclear risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting | |

| Criteria for a judgement of 'low risk' of bias | Any of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'high risk' of bias | Any one of the following:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'unclear risk' of bias | Insufficient information to permit judgement of 'low risk' or 'high risk'. It is likely that the majority of studies will fall into this category. |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table | |

| Criteria for a judgement of 'low risk' of bias | Study appeared to be free of other sources of bias. |

| Criteria for a judgement of 'high risk' of bias | There was one or more important risk of bias, such as the study:

|

| Criteria for a judgement of 'unclear risk' of bias | There may be a risk of bias, but there was either:

|

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Drain use versus no drain use.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Intraperitoneal abscess | 5 | 453 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.47, 3.21] |

| 1.2 Wound infection | 5 | 478 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.01 [0.88, 4.56] |

| 1.3 Morbidity | 1 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 6.67 [2.13, 20.87] |

| 1.4 Mortality | 4 | 363 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.88 [1.18, 20.09] |

| 1.5 Hospital stay | 3 | 298 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.17 [1.76, 2.58] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Dandapat 1992.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Country: India Study dates: not reported Number randomised: 86 Postrandomisation dropout: 0 (0%) Children: 16 (19%) Adults: 70 (81%) Females: 16 (19%) Normal appendix: 0 (0%) Simple appendicitis: 0 (0%) Gangrenous appendicitis: 0 (0%) Perforated appendicitis: 86 (100%) Appendiceal phlegmon or abscess: 0 (0%) Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants with complicated appendicitis (n = 86) were randomly assigned to 2 groups. Group 1: drainage (n = 40) Group 2: no drainage (n = 46) | |

| Outcomes | The outcomes reported were wound infection, intraperitoneal abscess, duration of postoperative fever, postoperative complications, mortality, and hospital stay. | |

| Notes | The drainage tube (corrugated rubber drain) was placed down into the right iliac fossa. Funding source: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: there were no postrandomisation dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: the study protocol was not available, but it was clear that the published reports included all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: the study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Haller 1973.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Quasi‐randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Country: USA Study dates: 1965 to 1971 Number randomised: 43 Postrandomisation dropout: 0 (0%) Children (0 to 14 years): 43 (100%) Adults: 0 (0%) Females: 10 (23%) Normal appendix: 0 (0%) Simple appendicitis: 0 (0%) Gangrenous appendicitis: 0 (0%) Perforated appendicitis: 43 (100%) Appendiceal phlegmon or abscess: 0 (0%) Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants with complicated appendicitis (n = 43) were randomly assigned to 2 groups. Group 1: drainage (n = 24) Group 2: no drainage (n = 19) | |

| Outcomes | The outcomes reported were intraperitoneal abscess, postoperative complications, mortality, and hospital stay. | |

| Notes | The drainage tube (Penrose drain) was placed through the wound down into the right iliac fossa and pelvis. Funding source: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: "Transperitoneal drainage was used in children with even hospital numbers and no drainage or wound drainage alone was used in children with odd hospital numbers" Comment: the allocation was performed on the basis of a pseudo‐random sequence (odd/even hospital number) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: there were no postrandomisation dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: the study protocol was not available, but it was clear that the published reports included all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: the study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Jani 2011.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Country: Kenya Study dates: not reported Number randomised: 90 Postrandomisation dropout: 0 (0%) Age (13 to 26): 44 (49%) Age (27 to 54): 46 (51%) Females: 40 (44%) Normal appendix: 0 Simple appendicitis: 0 Gangrenous appendicitis: 0 (0%) Perforated appendicitis: 79 (87.8%) Appendiceal phlegmon or abscess: 11 (12.2%) Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants with complicated appendicitis (n = 90) were randomly assigned to 2 groups. Group 1: drainage (n = 45) Group 2: no drainage (n = 45) | |

| Outcomes | The outcomes reported were wound infection, intraperitoneal abscess, morbidity, postoperative complications, hospital stay, and duration of antibiotic use. | |

| Notes | The drainage tube (PVC suction catheter) was placed through a separate incision down into the right iliac fossa. Funding source: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: there were no postrandomisation dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: the study protocol was not available, but it was clear that the published reports included all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: the study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Mustafa 2016.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Country: Pakistan Study dates: March 2015 to April 2016 Number randomised: 68 Postrandomisation dropout: 0 (0%) Age (18 to 25): 31 (46%) Age (26 to 33): 26 (38%) Age (34 to 39): 11 (16%) Females: 32 (47%) Normal appendix: 0 Simple appendicitis: 0 Gangrenous appendicitis: 0 (0%) Perforated appendicitis: 68 (100%) Appendiceal phlegmon or abscess: 0 (0%) Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants with complicated appendicitis (n = 68) were randomly assigned to 2 groups. Group 1: drainage (n = 34) Group 2: no drainage (n = 34) | |

| Outcomes | The outcomes reported were wound infection and hospital stay. | |

| Notes | Funding source: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "These patients were randomly allocated into 2 treatment groups using lottery method" Comment: no information provided about the method of random sequence generation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: there were no postrandomisation dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: the study report failed to include results for a key outcome (intraperitoneal abscess) that would be expected to have been reported for such a study |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: the study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Stone 1978.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Quasi‐randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Country: USA Study dates: September 1975 to November 1977 Number randomised: 283 Postrandomisation dropout: 0 (0%) Children: not mentioned Adults: not mentioned Females: 124 (44%) Normal appendix: 0 (0%) Simple appendicitis: 66 (23%) Suppurative appendicitis: 123 (44%) Gangrenous appendicitis: 32 (11%) Perforated appendicitis: 62 (22%) Appendiceal phlegmon or abscess: 0 (0%) Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants with complicated appendicitis (n = 94) were randomly assigned to 2 groups. Group 1: drainage (n = 49) Group 2: no drainage (n = 45) | |

| Outcomes | The outcomes reported were wound infection, intraperitoneal abscess, postoperative complications, and mortality. | |

| Notes | The drainage tube (Penrose drain) was placed through a separate incision down into the right iliac fossa. Funding source: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: "A Penrose drain was inserted through a separate stab wound if the final digit of the patient's hospital number was an odd figure. An even final digit dictated exclusion of any form of peritoneal drainage" Comment: the allocation was performed on the basis of a pseudo‐random sequence (odd/even hospital number) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: there were no postrandomisation dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: the study protocol was not available, but it was clear that the published reports included all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: the study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Tander 2003.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Country: Turkey Study dates: not reported Number randomised: 140 Postrandomisation dropout: 0 (0%) Children (0 to 11 years): 140 (100%) Adults: 0 (0%) Females: 38 (27%) Normal appendix: 0 (0%) Simple appendicitis: 0 (0%) Gangrenous appendicitis: 0 (0%) Perforated appendicitis: 140 (100%) Appendiceal phlegmon or abscess: 0 (0%) Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants with complicated appendicitis (n = 140) were randomly assigned to 2 groups. Group 1: drainage (n = 70) Group 2: no drainage (n = 70) | |

| Outcomes | The outcomes reported were wound infection, intraperitoneal abscess, postoperative complications, mortality, hospital stay, and duration before oral intake. | |

| Notes | 2 drainage tubes (Penrose drains) were placed through the wound down into the right iliac fossa and pelvis, respectively. Funding source: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: there were no postrandomisation dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: the study protocol was not available, but it was clear that the published reports included all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: the study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abdulhamid 2018 | A non‐randomised study |

| Allemann 2011 | A non‐randomised study |

| Al‐Shahwany 2012 | A non‐randomised study |

| Beek 2015 | A non‐randomised study |

| Everson 1977 | Randomised controlled trial evaluating extraperitoneal wound drainage (wound drainage versus no wound drainage) |

| Ezer 2010 | A non‐randomised study |

| Fujishiro 2020 | A non‐randomised study |

| Greenall 1978 | The study was excluded because not all participants received antibiotics. |

| Johnson 1993 | A non‐randomised study |

| Magarey 1971 | The study was excluded because not all participants received antibiotics. |

| Miranda‐Rosales 2019 | A non‐randomised study |

| Narci 2007 | A non‐randomised study |

| Piper 2011 | A non‐randomised study |

| Song 2015 | A non‐randomised study |

| Toki 1995 | Randomised controlled trial evaluating peritoneal lavage versus abdominal drainage |

Characteristics of studies awaiting classification [ordered by study ID]

Afzal 2017.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Country: Pakistan Study dates: November 2014 to May 2015 Number randomised: 68 Postrandomisation dropout: 0 (0%) Mean age: 26 Children: not mentioned Adults: not mentioned Females: 32 (47%) Normal appendix: 0 Simple appendicitis: 0 Gangrenous appendicitis: 0 (0%) Perforated appendicitis: 68 (100%) Appendiceal phlegmon or abscess: 0 (0%) Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

| Interventions | Participants with complicated appendicitis (n = 68) were randomly assigned to 2 groups. Group 1: drainage (n = 34) Group 2: no drainage (n = 34) |

| Outcomes | The outcomes reported were wound infection and hospital stay. |

| Notes | The data could not be verified. |

Differences between protocol and review

We changed the title of the review to reflect the primary outcome.

We changed wound infection from a primary outcome to a secondary outcome.

We included two quasi‐randomised controlled trials, and performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding these two trials according to the suggestions of the editors and peer‐reviewers.

We added that all participants received similar antibiotic regimens after open appendectomy in both drainage and no‐drainage groups; studies that included participants who did not receive prophylactic antibiotics were excluded, because the use of antibiotic regimens after appendectomy was found to have a positive effect on clinically relevant outcomes by another Cochrane Review (Andersen 2005).

We changed the time frame for reporting intraperitoneal abscess and wound infection from 14 days to 30 days because we considered 30 days as the ideal time frame for measurement in the review stage.

We did not create funnel plots to assess potential publication bias due to the small number of included trials.

We did not perform any of our planned subgroup analyses to assess heterogeneity because of the small number of trials included for each outcome.

We contacted the original investigators to request further information but did not receive any replies.

Contributions of authors

Li Zhuyin: drafted the updated review and carried out the analysis.

Li Zhe: extracted data from the trials and entered data into Review Manager 5.

Zhao L: extracted data from the trials and entered data into Review Manager 5.

Cheng Y: drafted the protocol, assessed trials for inclusion in the review, and assessed the risk of bias of the trials.

Cheng N: assessed trials for inclusion in the review and assessed the risk of bias of the trials.

Deng Y: revised the final review and secured funding for the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Zhengzhou University, China

Provided funding for the review.

-

Chongqing Medical University, China

This review was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81701950), Medical Research Projects of Chongqing (Grant No. 2018MSXM132), and the Kuanren Talents Program of the second affiliated hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Grant No. KY2019Y002).

External sources

-

none, China

none

Declarations of interest

Li Zhuyin: None known

Li Zhe: None known

Zhao L: None known

Cheng Y: None known

Cheng N: None known

Deng Y: None known

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Dandapat 1992 {published data only}

- Dandapat MC, Panda C. A perforated appendix: should we drain? Journal of the Indian Medical Association 1992;90(6):147-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Haller 1973 {published data only}

- Haller JA Jr, Shaker IJ, Donahoo JS, Schnaufer L, White JJ. Peritoneal drainage versus non-drainage for generalized peritonitis from ruptured appendicitis in children: a prospective study. Annals of Surgery 1973;177(5):595-600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jani 2011 {published data only}

- Jani PG, Nyaga PN. Peritoneal drains in perforated appendicitis without peritonitis: a prospective randomized controlled study. East and Central African Journal of Surgery 2011;16(2):62-71. [Google Scholar]

Mustafa 2016 {published data only}

- Mustafa MIT, Chaudhry SM, Mustafa RIT. Comparison of early outcome between patients of open appendectomy with and without drain for perforated appendicitis. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences 2016;10(3):890-3. [Google Scholar]

Stone 1978 {published data only}

- Stone HH, Hooper CA, Millikan WJ Jr. Abdominal drainage following appendectomy and cholecystectomy. Annals of Surgery 1978;187(6):606-12. [DOI: 10.1097/00000658-197806000-00004] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tander 2003 {published data only}

- Tander B, Pektas O, Bulut M. The utility of peritoneal drains in children with uncomplicated perforated appendicitis. Pediatric Surgery International 2003;19(7):548-50. [DOI: 10.1007/s00383-003-1029-y] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]