Abstract

The mental health of law enforcement officers (LEO) is critical to the safety and well-being of the officers and the public they serve. However, LEO face significant on-the-job stressors that undermine mental health, and there is a lot to be learned about when and how LEO seek and enter mental health services. The present study sought to explore variables related to mental health seeking behavior, the role of social engagement and social pressure in the decision to seek mental health services, and the most common pathways into mental health utilized by LEO. A small sample of 86 LEO were recruited from the social media page of a law enforcement nonprofit support organization to take several self-report measures on past mental health service usage and intentions to seek future services, the Inventory of Attitudes Toward Seeking Mental Health Services, the Professional Quality of Life Survey, and a measure of social engagement on mental health topics. Results indicate that while a number of factors are associated with intentions to seek future services, the primary factor in past mental health seeking behavior was secondary traumatic stress. Those who sought mental health services reported higher social engagement and social pressure to seek help. LEO entered mental health services for a variety of reasons and through a variety of provider options, such that no one provider source was preferred. Though the present study was limited by a small sample size, reliance on self-report measures, and occurred during a time of civil unrest that sparked the “defund the police” movement, the results serve as a starting point for understanding the pathways into mental health services for LEO and the roles of secondary trauma and prior mental health service experience.

Keywords: Law enforcement mental health, Social engagement, Social pressure, Secondary traumatic stress, Pathways to mental health

Background

Diagnosing and treating a physical health problem follows a well-accepted convention: identify the problem, seek a diagnosis, and begin treatment. Someone who experiences back pain that interferes with their quality of life is likely to initiate a visit with their general physician, who can then provide guidance on treatment options. The conventions for mental health diagnosis and treatment are less straightforward (Corrigan et al. 2014; Pescosolido et al. 1998). For many people, ambiguity exists at all of the steps, from identifying the signs of mental illness and need for treatment, to knowing how or where to access treatment, to understanding that treatments are available and effective (Henderson et al. 2013). Not only do many individuals often fail to identify their mental health status, but they are often reticent to seek a diagnosis because of mental illness stigma and fear of discrimination. Often, a spouse or close family member identifies the treatment need and pressures their loved one into seeking treatment (Perry and Pescosolido 2015).

For law enforcement officers (LEO), there may be a special need for mental health services given the amount of chronic stress and the risk of experiencing trauma, either directly or indirectly (Liberman et al. 2002). A significant amount of research has focused on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and resulting symptoms, somewhat narrowing the focus on one specific traumatic event as the factor in police stress. Recently, researchers have focused on the concept of repeated primary and secondary traumatic stress in law enforcement. The term police complex spiral trauma (PCST) has been coined to describe the accumulation of long-term stress and trauma associated with police work (Papazoglou 2012). Further, the term cumulative career traumatic stress (CCTS) posits that as a result of continued exposure to traumatic incidents, an officer may suffer from the symptoms of PTSD in varying intensities (Marshall 2006). Both areas of study reaffirm that continued stressors, especially those commonly experienced in law enforcement, have a significant impact on mental health.

The Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale was designed to assess accumulated effects of working in helping professions such as nursing, first responders, law enforcement, and military personnel (Stamm 2010). Factor analysis of the ProQOL revealed three factors that emerged: compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. Compassion satisfaction is the degree to which an individual derives a sense of value or purpose from helping others in their work which provides a psychological buffer to negative outcomes. Burnout refers to a hopelessness or lack of motivation that impairs ability to do the job effectively. Secondary traumatic stress, sometimes called compassion fatigue, refers to the stress of witnessing or helping with the aftermath of traumatic events, such as medical emergencies or investigating domestic violence. These are stressors that produce symptoms similar to primary stressors as would be the case with PTSD, in which intrusive thoughts about the trauma may be disruptive, causing stress, avoidance, or loss of sleep (Stamm 2010).

Self-identification of stressors, in particular secondary trauma stressors, is difficult. Historically, research on police stress focuses on the consequences of stress (e.g., depression, burnout, and anxiety), stigma, organizational subculture, and coping strategies (Padilla 2020; Tucker 2015; Queiros et al. 2020). Very little of the focus has been on prolonged exposure to traumatic events and the subsequent self-identification of negative impacts of individual mental health. If and when this self-identification process occurs, the officer then faces a multitude of choices regarding the next step and what that will be.

There are many barriers to seeking mental health services in the general public. The World Health Organization identified these barriers as the perception of low need, overall ineffectiveness, negative experiences, or the desire to handle it on your own (Andrade et al. 2014). LEO, however, may be disproportionately impacted by barriers to treatment such as stigma associated with mental illness as a weakness or personal failing (Karaffa and Koch 2016). While many studies have explored intentions and attitudes, it is unclear how those intentions translate into behavior. According to the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA), help-seeking behavior can be broadly divided into two stages (Schwarzer 2008). The first stage is the formation of the intention to seek behavior, based on perceived self-efficacy (e.g., “I can do it”), expected outcomes (e.g., “the situation will be improved if I do it”), and risk perception (e.g., “I may be determined to be unfit for duty if I seek treatment”). The second stage engages a separate set of skills related to planning, execution, maintenance, and self-regulation of behavior. The gap between the transitions from intention to action is not well understood among LEO.

The present study seeks to identify factors that lead to intentions to seek mental health treatment among LEO. These may include attitudes toward mental health treatment, fear of stigma/retaliation, and the impact of social engagement and social coercion. These intentions were compared to measures of actual risk and volitional actions taken to address mental health needs. The goal is to connect attitudes and intentions toward seeking mental health to risk and mental health-seeking behavior to better streamline pathways into treatment for at-risk LEO. We collected information on how, when, and where individuals have sought services in the past to establish patterns of how LEO naturally enter the mental health care system.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from a private nonprofit law enforcement organization called “LEO Only.” LEO Only began as a Facebook page created by a law enforcement officer whose partner had succumbed to suicide. It was originally intended as a place for officers to express shared experiences. In order to gain access to the private Facebook group (https://www.facebook.com/leoonlyorg), the administrators require proof of current or retired law enforcement status via department credentials. LEO Only also has a separate website dedicated to their mission (https://leo-only.org/us/). While proof of current or retired law enforcement status is required for the Facebook site, it should be noted that to register for access to the stand-alone website, proof of law enforcement credentials are not required. The first item on the questionnaire confirmed LEO status with self-reported status, either active, retired, or not law enforcement. A total of 111 adults participated in the study, but a proportion of them did not answer any question past the basic demographic information and were excluded from the data analysis. The remaining 86 participants (50 male and 36 female) ranged from 1 to 37 years of experience in law enforcement (M = 16.9, SD = 9.0).

Procedure

Participants were first asked basic demographic information such as sex, job status (active or retired), gender, agency size (under 100 = small, 100–400 = medium, and over 400 = large), rank, and years in service. They then completed four questionnaires designed to measure attitudes toward mental health, burnout and trauma, social engagement, and health-seeking behavior.

Attitudes Toward Mental Health

Participants completed the Inventory of Attitudes Toward Seeking Mental Health Services (IATSMH), a 24 item questionnaire to assess attitudes toward seeking mental health treatment (Mackenzie et al. 2004). It has previously been validated and used with LEO (e.g., Hyland et al. 2014) and consists of three subscales: psychological openness, help-seeking propensity, and indifference to stigma. Hyland et al. (2014) observed high internal reliability, with all three subscales showing a composite reliability score of at least 0.70. They also confirmed the construct validity by verifying the factor structure within their law enforcement sample and demonstrated high concurrent validity with measures of intentions to engage in counseling.

The psychological openness subscale assesses the degree to which an individual is willing to discuss and explore their psychological problems, such that those who are more open score higher on the scale. An example reverse-scored item from the psychological openness scale is “There are certain problems which should not be discussed outside of one's immediate family.” The help-seeking propensity scale is meant to assess people’s willingness to get professional help, e.g., “If I believed I were having a mental breakdown, my first inclination would be to get professional attention.” The indifference to stigma subscale has questions related to stigma beliefs such as, “Having been mentally ill carries with it a burden of shame.” Many of the stigma questions are reverse scored, such that a higher scale value results in less stigma overall. When added together, the composite score reflects overall willingness to seek mental health services.

Burnout and Trauma

The Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) questionnaire has been used in many studies of law enforcement studies and other helping professions to assess risk for burnout and compassion fatigue, both of which have been associated with negative mental health outcomes. It contains 30 questions and assesses three subscales: compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. The ProQOL has been shown to have high internal reliability and high construct validity (Stamm 2010), though one large study of nurses and palliative care workers raised questions about the convergent validity of the burnout and secondary trauma scales with these populations (Hemsworth et al. 2018). Given its ubiquity, the ProQOL is useful for exploring these constructs despite any imperfections that may exist.

The compassion satisfaction subscale assesses the degree to which people find their job in the helping professions as rewarding or fulfilling and contains items such as “I get satisfaction from being able to help people.” The burnout scale measures the degree to which the individual is overwhelmed and unmotivated by their work, with items such as “I feel overwhelmed because my case load seems endless.” The secondary traumatic stress scale includes items such as “I think that I might have been affected by the traumatic stress of those I help,” which give a picture of how much the individual is troubled by the trauma they experience through their work. These three scales are independent from each other and are not combined to create a composite score.

Social Engagement

Participants were asked about the involvement of others in their mental health decisions in a modified version of the “health matters” name generator task (Perry and Pescosolido 2015). Participants were asked to report on a 3-point Likert type scale how often they discussed their mental health (always, sometimes, never) for the following individuals: partner, mother, father, sibling, child, friend, coworker, neighbor, mental health professional, or other. An option for Not Applicable was available as well. Then, they were asked whether those individuals had recommended that they seek mental health treatment (Yes, No, Not Applicable).

Help-Seeking Behavior

Both past behavior and future intentions to seek mental health services were assessed. Participants were asked questions about whether they had sought treatment in the past, what led to that decision, and which provider they chose. Provider options listed were Employee Assisted Program provider, health care provider or family doctor, psychologist specializing in law enforcement, peer support group, or other. Participants were then asked a parallel set of questions about whether they are considering seeking help in the future, what led to that decision, and what provider pathway they were considering.

Results

Participants were included in a statistical test if they had made responses on the variables to be included in the test. They were excluded if they had missing data on one or more of the variables included in that analysis, but they were included on other analyses. Four main data analyses were carried out to determine which variables were associated with past mental health help-seeking behavior, which ones are related to future mental health help-seeking intentions, which social engagements were most influential, and which pathways into mental health services were preferred.

Pathways to Mental Health

Out of the 86 participants, 35 answered “no” to the question about seeking mental health services in the past, whereas 45 answered “yes,” and 6 failed to answer the question. Of those who answered yes and provided a reason for seeking services, 13 reported seeking mental health services for personal reasons such as marital infidelity or substance abuse. Though they may have mentioned more than one issue, 11 of those 13 specifically mentioned relationship or marriage difficulties. Twenty-two of the 43 that reported seeking mental health services did so because of manifestations of symptoms such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, or panic attacks, often from job-related stress or traumatic events. Five more were required to attend based on a specific on-the-job event such as an officer involved shooting, and only three reported attending on the basis of recommendation by a friend, coworker, or doctor.

Of the 45 who reported past mental health seeking, 13 used a provider with a law enforcement specialty, 8 reported using an employee assistance program, 7 reported starting with a family doctor or health care provider, 3 attended a peer support group, and 14 chose “other,” describing a wide array of pathways, from recommendations by people close to them or by google searches and cold calling.

A total of 78 answered whether they were planning to seek mental health services in the future, but only 24 of them answered “yes.” One failed to provide a reason, 2 of them wanted to attend for personal reasons, 13 related to manifestations of symptoms, one because of a specific on-the-job event, and 7 reported that they wanted to go because of maintenance from previous mental health issues or prevention of future problems. Of the 24 who answered “yes,” 7 planned to see a law enforcement specialist, 3 planned to visit a family doctor, 2 planned to attend peer groups, 2 planned to make use of an EAP, and 8 listed “Other.” The remaining two did not specify their treatment provider.

Past Help-Seeking Behavior

A logistic model was fitted to the data to determine whether the ProQOL subscales (compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress) or the IATSMH subscales (psychological openness, help-seeking propensity, and indifference to stigma) were associated with past mental health seeking behavior. Total years in service, gender, and agency size were also included in the model. The variables in the model significantly explained past behavior, χ2 = 28.62, df = 68, p = 0.001, R2Tjur = 0.31 (Table 1). Of the nine variables in the model, the only significant association with help-seeking behavior was secondary traumatic stress, such that higher secondary traumatic stress was associated with higher help-seeking (p < 0.01, odds ratio = 1.23).

Table 1.

Logistic regression of past help-seeking behavior

| Estimate | Standard error | β | Odds ratio | z | Wald | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | − 13.01 | 5.00 | 0.96 | > 0.01 | − 2.62 | 6.87 | 0.01* |

| PROQOL | |||||||

| Compassion satisfaction | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.72 | 1.12 | 1.53 | 2.34 | 0.13 |

| Burnout | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.55 | 1.09 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.36 |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.21 | 0.08 | 1.57 | 1.23 | 2.60 | 6.75 | 0.01* |

| IATSMH | |||||||

| Psychological openness | − 0.05 | 0.07 | − 0.27 | 0.95 | − 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.51 |

| Help-seeking propensity | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.60 | 1.11 | 1.36 | 1.86 | 0.17 |

| Indifference to stigma | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 1.04 | 0.71 | 0.51 | 0.48 |

| Total years of service | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 1.05 | 1.29 | 1.67 | 0.20 |

| Gender (male) | − 0.35 | 0.62 | − 0.35 | 0.70 | − 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.57 |

| Agency size (medium) | − 0.05 | 0.77 | − 0.05 | 0.95 | − 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.95 |

| Agency size (large) | − 0.82 | 0.66 | − 0.82 | 0.44 | − 1.25 | 1.55 | 0.21 |

Past mental health seeking level “Yes” coded as class 1

*p < 0.05

Future Intentions of Help-Seeking Behavior

A logistic model was fitted to the data to determine which variables were related to future help-seeking intentions. The variables included were the same as before, but with the addition of past help-seeking behavior as a variable in the model. The model was significantly associated with future help-seeking intentions, χ2 = 61.1, df = 65, p < 0.001, R2Tjur = 0.67 (Table 2). Secondary traumatic stress again showed a significant positive relationship (p = 0.03, odds ratio = 1.32), but this time, several other variables were positively correlated with higher help-seeking intentions as well: compassion satisfaction (p = 0.02, odds ratio = 0.59), indifference to stigma (p = 0.02, odds ratio = 1.41), total years in service (p = 0.03, odds ratio = 0.77), and past mental-health seeking behavior (p < 0.01, odds ratio = 624.25). While higher values on all of these measures were associated with higher help-seeking intentions, notably, the odds ratio for past mental-health seeking was the largest; for individuals who reported past mental health seeking behavior, the odds of intent to seek future services was more than 624 to 1.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of future help-seeking intentions

| Estimate | Standard error | β | Odds ratio | z | Wald | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | − 9.67 | 9.37 | − 7.72 | > 0.01 | − 1.03 | 1.06 | 0.30 |

| ProQOL | |||||||

| Compassion satisfaction | − 0.52 | 0.22 | − 3.41 | 0.59 | − 2.43 | 5.89 | 0.02* |

| Burnout | 0.37 | 0.25 | 2.44 | 1.44 | 1.49 | 2.21 | 0.14 |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.28 | 0.13 | 2.15 | 1.32 | 2.22 | 4.93 | 0.03* |

| IATSMH | |||||||

| Psychological openness | − 0.18 | 0.14 | − 1.04 | 0.83 | − 1.31 | 1.71 | 0.19 |

| Help-seeking propensity | 0.34 | 0.19 | 2.04 | 1.41 | 1.85 | 3.41 | 0.06 |

| Indifference to stigma | 0.34 | 0.15 | 2.54 | 1.41 | 2.37 | 5.61 | 0.02* |

| Total years of service | − 0.26 | 0.12 | − 2.38 | 0.77 | − 2.15 | 4.64 | 0.03* |

| Gender (male) | − 2.14 | 1.48 | − 2.14 | 0.12 | − 1.44 | 2.08 | 0.15 |

| Agency size (medium) | − 1.22 | 1.51 | − 1.22 | 0.30 | − 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.42 |

| Agency size (large) | 2.68 | 1.45 | 2.68 | 14.59 | 1.85 | 3.42 | 0.06 |

| Past mental health seeking | 6.44 | 2.41 | 6.44 | 624.25 | 2.67 | 7.12 | > 0.01* |

Future mental health seeking level “Yes” coded as class 1

*p < 0.05

Influence of Social Engagement

Eighty participants completed the social engagement questions, rating the frequency with which they spoke to 10 people about their mental health issues (Fig. 1). A Friedman’s Test on the 10 people indicated a significant difference between people listed, χ2 (9) = 271.19, p < 0.001, Kendall’s W = 0.29. Pairwise Conover post-hoc tests indicated that partner and friend were considered more likely than all other people, ps < 0.04, followed by coworker who did not differ from partner, friend, or professional but was higher than all other people, ps < 0.01. Professional was next highest, higher than the remaining people listed except mother and sibling, ps < 0.02. Mother, father, sibling, and child did not differ from each other, but all but child were higher than neighbor and other, ps < 0.02. Child, neighbor, and other were rated lowest and did not differ from each other. When past mental health seeking behavior is included as a between subjects variable, there is a small but reliable main effect that those who reported seeking mental health services in the past were more likely to report having talked to people about their mental health issues, F(1,77) = 7.71, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.02. No other effects or interactions are significant.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of discussing mental health issues with various sources of social engagement (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = always). Error bars reflect + / − SEM corrected for within-subjects data (O’Brien and Cousineau 2014)

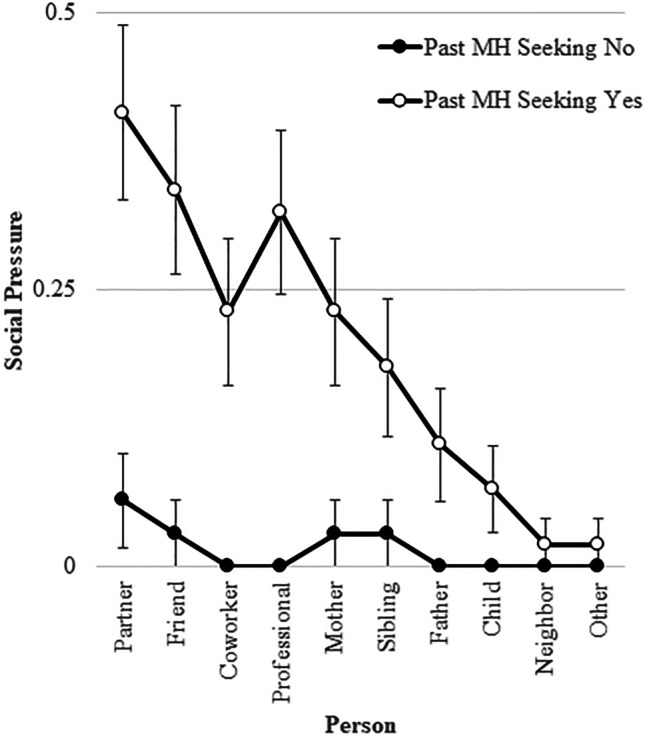

Next, participants rated whether the same 10 people had recommended that they seek mental health treatment (Fig. 2). A Friedman’s test indicated a significant difference between people, indicating that some were more likely than others to suggest treatment, χ2 (9) = 62.34, p < 0.001, Kendall’s W = 0.34. The most likely to recommend treatment were partner and friend, followed by professional, mother, coworker, sibling, father, child, neighbor, and other, respectively. When past mental health seeking behavior was included as a between subjects factor, those who had sought mental health treatment reported significantly higher social pressure to do so, F(1,77) = 25.41, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.08. Furthermore, there was a significant Person X Past health seeking behavior interaction, consistent with the idea that those who were under more social pressure to seek treatment were more likely to engage in mental health seeking behaviors.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of discussing mental health issues with various sources of social engagement (0 = no, 1 = yes). Open circles are individuals who reported past mental health-seeking behavior, whereas closed circles are those who had not sought mental health services in the past. Error bars reflect + / − SEM corrected for within-subjects data (O’Brien and Cousineau 2014)

Discussion

Our study evaluated variables associated with seeking mental health services and pathways into mental health treatment. The use of the IATSMH and ProQOL helped frame the participants’ attitudes toward seeking mental health services and potential need for services. Our research positively aligned with previous research on mental health needs for law enforcement officers in terms of primary and secondary traumatic stress, emotional/physical response from stress, and barriers to seeking mental health care (Acquadro-Maran et al. 2015; and Padyab et al. 2016; Papazoglou and Chopko 2017).

Much of the previous research has focused primarily on intentions to seek mental health services, especially with attention to the disconnect between self-identification of a need for mental health services and actual treatment-seeking behavior. Our findings indicated that while many of the commonly studied variables predict intentions to seek mental health services, the most important variable associated with actual mental health seeking among variables we measured is secondary traumatic stress. Our results can be viewed as promising in that they suggest that people are able to identify when they are experiencing trauma and may be especially in need, as is the case with PCST, CCTS, or PTSD. On the other hand, our results may suggest that individuals fail to seek mental health services until they are already experiencing substantial stress which may have been mitigated with earlier treatment. Based on these results, organizations should be especially mindful of signs of secondary traumatic stress and should target interventions toward identifying and supporting affected individuals. Signs of secondary traumatic stress vary per officer but are often recognized as being similar to PTSD symptoms that are experienced by primary trauma victims (Newell and Gordon 2010). This is further complicated by the frequency of traumatic calls and individual department training; both of which can impact the way in which an officer is affected. It is important to note that since the signs of secondary traumatic stress can be subjective, it is important that administrators work in conjunction with clinicians associated with the employee assistance program to identify department specific defining features. Administrative tracking and personal tracking tools could easily be implemented based on calls for service and incident response.

Consistent with previous studies, social engagement and social pressure to seek help was an important predictor of actual help-seeking behavior. Those participants who reported having sought mental health services in the past also reported that they discussed their problems with people close to them more often and were more often encouraged by those people to seek treatment. Unlike previous studies in which the spouse, mother, or other close family were likely to be the person with whom mental health issues are discussed (Perry and Pescosolido 2015), in this case, the preference was to discuss issues with the spouse, but also coworkers and friends rather than family members. It is likely that this reflects a tendency for LEO to have friends and coworkers who also have law enforcement experience and can relate to the unique job pressures. Together, the social engagement data reported here suggest that law enforcement agencies may be able to improve mental health seeking behavior through encouraging a culture of mutual support among coworkers. This is often encouraged via the use of peer support groups in which police officers provide a broad spectrum of psychological support for fellow officers including confidential and non-judgmental active listening, comradery in shared experiences, stress management strategies, and an avenue for professional mental health services (Fisher et al. 2020; Milliard 2020). The ideology and importance of law enforcement peer support groups has garnered attention by the International Association of Chiefs of Police resulting in ratified peer support guidelines that are accessible for all law enforcement agencies (IACP 2021). Although it is unknown how available these types of support groups are, it would seem prima facie that peer groups would be more common among larger agencies.

Surprisingly, some commonly cited factors such as fear of stigma, burnout, psychological openness, compassion satisfaction, and help-seeking propensity were not associated with help-seeking behavior. While some of these factors were related to future intentions to seek mental health services, only secondary traumatic stress was related to actual help-seeking. When assessing intentions to seek future services, all other variables were dwarfed by the strength of the relationship with past mental health seeking experience. This suggests that, while factors like stigma may be important, they are not the deciding factors in initiation of mental health seeking behavior; future interventions may be better served by encouraging exploratory experiences with mental health services. While it may be that only those with the strongest need seek treatment, these data may also indicate that positive experiences with mental health services may help clients understand the potential benefits of services, or familiarity may help overcome fear of the unknown and remove mental barriers to treatment. If this is the case, prior exposure to mental health services may promote future utilization of services.

While the focus of the present study was on work-related stress and trauma, it is notable that many of the participants reported personal issues such as trouble with marital or other family relationships as motivation for seeking treatment. There are many questions that could be explored on this topic, but perhaps the most important thing to consider is that work stress and secondary trauma do not occur in a vacuum; the occupational stressors are likely to have an impact on mental health globally which can strain personal relationships or vice versa. While this is an area that needs exploration, there is some literature that supports the interaction of personal and occupational stressors among first responders. For example, Smith et al. (2018) established a relationship between work stress, burnout, and work-family conflict in firefighters. Based on the link between social pressure and past mental health seeking behavior in the present study, it could be speculated that social pressure increases when mental health starts affecting personal relationships rather than work stress directly. It is possible that the path from work stress to mental health seeking is mediated by struggles with personal relationships; this is a hypothesis that is ripe for exploration.

There are some important limitations to the present study to consider. The variables measured in this study were chosen based upon their utility in previous literature on other populations, but they are not the only variables that could influence attitudes toward mental health seeking behavior. For this reason, it is important to recognize that the best variable in our model is in reference only to the other variables in the model, and there may be other variables that could improve the model. For example, measures of stressful life events (e.g., Holmes and Rahe 1967) or a direct measure of PTSD symptoms (e.g., Weathers et al. 1993) are likely to also be predictive of mental health seeking behavior and might be targets for future exploration. It is also notable that routine stressors such as mismanagement, discrimination, or other workplace issues have been shown to be associated with PTSD symptom severity and overall mental health (e.g., Maguen et al. 2009; Marmar et al. 2006; Wagner et al. 2020) but were not measured here. Finally, our data were limited to self-report measures of behavior which may be subject to personal biases, and intentions to seek mental health may not always translate into actual mental health seeking behavior. Longitudinal studies that added measures of future mental health seeking behavior would complement this work. Indeed, our data highlight how previous studies may have been subject to this problem, given that many more variables were associated with intentions to seek mental health services than were associated with past mental health seeking behavior. Despite its limitations, this study is a starting point for exploring how LEO find their way into mental health services.

The authors acknowledge that the sample size of this study was significantly impacted due to the international SARS-COV-2 pandemic, the nationally publicized incidents of police officer use of force, and the events surrounding the “defund the police” movement. This study spanned the time period during which these events unfolded. While participant response to this study was overwhelmingly positive initially, the convergence of these three significant events likely impeded participants’ desire to discuss mental health needs and pathways to seeking treatment. Of the 86 participants, 50 responded to monthly invitations for participation in July of 2020, 13 in August, and 5 in September. In October, the frequency of calls was increased, yielding 15 more participants, but by November, only 3 participants responded. Some LEO responded to the later calls with skepticism about the researcher’s agenda and questions about who the data was for and how it would be used. Ironically, for many officers, these three events are likely to result in secondary stressors making the results of this study even more relevant.

If and when an officer identifies that they are in need of mental health services, there is still a barrier when attempting to locate the best services for their individual needs. An Internet search of mental health providers is overwhelming, especially when in immediate need of services. It is our recommendation that law enforcement agencies provide their employees with a variety of information rather than having a primary focus on EAP’s. Ensuring that additional avenues to seek mental health services are available, such as peer groups and police psychologists, will provide the best support for law enforcement personnel who tend to take myriad pathways into mental health treatment. This study does not assess the availability of EAPs and other services or initiatives available to our sample as that moves beyond the scope of our initial research questions. Future studies might explore this further to determine whether the results reported here reflect a preference to utilize resources outside of EAP initiatives or whether it is more likely due to unavailability of EAPs. This is an important issue to address considering it leaves only two options: either there are not enough EAPs suited to serve the needs of LEO or LEO are uncomfortable using EAP resources. Similar issues arise related to the availability and quality of support groups, which obfuscates whether support group initiatives would be fully utilized if they were to be made widely available.

Supporting the mental health needs of law enforcement officers is critical to increasing the safety of both officers and the public they serve. The findings of the present study add to the growing literature on how to best accomplish this goal by showing that secondary traumatic stress, social engagement and pressures, and past experience with services were critical factors in mental health seeking behaviors. Furthermore, officers were inclined to seek support through myriad pathways into mental health services. No matter the pathway to services, by supporting law enforcement officer needs, we can improve the well-being of both law enforcement and the greater community.

Author Contribution

Both authors contributed equally to this work.

Availability of Data and Material

Anonymized numerical data will be made available upon request. Due to the sensitive nature of open-ended questions, they cannot be made available.

Code Availability

Files used for data analysis in JASP will be made available upon request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The protocol was approved by the Chaminade University of Honolulu Institutional Review Board.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Consent for Publication

All participants consented to publication of anonymized data prior to data collection.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alan M. Daniel, Email: alan.daniel@tamusa.edu

Kelly S. Treece, Email: kelly.treece@chaminade.edu

References

- Acquardo-Maran D, Varetto A, Zedda M, Ieraci V. Occupational stress, anxiety and coping strategies in police officers. Occup Med. 2015;65:466–473. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade L, Alonso J, Mneimneh Z, Wells JE, Al-Hamzawi A, Borges G, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, de Graff R, Florescu S, Gureje O, Hinkov HR, Hu C, Huang Y, Hwang I, Jin R, Karam EG, Kovess-Masfley V, Levinson D, Matschinger H, O’Neill S, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Sampson NA, Sasu C, Stein D, Takeshima T, Viana MC, Xavier M, Kessler RC. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol Med. 2014;44(6):1303–1317. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P, Druss B, Perlick D. The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2014;15(2):37–70. doi: 10.1177/1529100614531398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E, Miller S, Evans M, Luu S, Tang P, Valovcin D, Castellano C. COVID-19, stress, trauma, and peer support - observations from the field. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(3):503–505. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsworth D, Baregheh A, Aoun S, Kazanjian A. A critical enquiry into the psychometric properties of the professional quality of life scale (ProQol-5) instrument. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;39:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):777–780. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland P, Boduszek D, Dhingra K, Shevlin M. A test of the inventory of attitudes towards seeking mental health services. Br J Guid Counc. 2014;43(4):37–41. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2014.963510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Chiefs of Police. (2021) Peer support guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.theiacp.org/resources/peer-support-guidelines

- Karaffa K, Koch J. Stigma, pluralistic ignorance, and attitudes towards seeking mental health services among police officers. Crim Justice Behav. 2016;43(6):759–777. doi: 10.1177/0093854815613103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman A, Best S, Metzler T, Fagan J (2002) Routine occupational stress and psychological distress in police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 25(2):421–441. 10.1108/13639510210429446

- Mackenzie CS, Knox VJ, Gekoski WL, Macaulay HL. An adaptation and extension of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34:2410–2435. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb01984.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Metzler TJ, McCaslin SE, Inslicht SS, Henn-Haase C, Neylan TC, Marmar CR. Routine work environment stress and PTSD symptoms in police officers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(10):754. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b975f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmar CR, McCaslin SE, Metzler TJ, Best S, Weiss DS, Fagan J, Neylan T (2006) Predictors of posttraumatic stress in police and other first responders. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1071. 10.1196/annals.1364.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marshall E. Cumulative career traumatic stress (CCTS): a pilot study of traumatic stress in law enforcement. J Police Crim Psychol. 2006;21:62–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02849503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millad B (2020) Utilization and impact of peer-support programs on police officers’ mental health. Front Psychol 11. 10.13389/psyg.2020.01686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Newell J, MacNeil G. Professional burnout, vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue: a review of theoretical terms, risk factors, and preventive methods for clinicians and researchers. Best Pract Ment Health. 2010;6(2):57–68. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien F, Cousineau D (2014) Representing error bars in within-subject designs in typical software packages. Quant Methods Psychol 10(1):56–67.

- Padilla KE. Sources and severity of stress in a Southwestern police department. Occup Med. 2020;70(2):131–134. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazoglou K. Conceptualizing police complex spiral trauma and its applications in the police field. Traumatology. 2012;9(3):196–209. doi: 10.1177/1534765612466151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papazoglou K, Chopko B (2017) The role of moral suffering (moral distress and moral injury) in police compassion fatigue and PTSD: an unexplored topic. Front Psychol 8. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Payab M, Backteman-Erlanson S, Brulin C (2016) Burnout, coping, stress of conscience and psychosocial work environment among patrolling police officers. J Crim Psychol 231, 229–237.

- Perry B, Pescosolido B. Social network activation: the role of health discussion partners in recovery from mental illness. Soc Sci Med. 2015;125:116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido B, Gardner C, Lubell K. How people get into mental health services: stories of choice, coercion and “muddling through” from “first-timers”. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(2):275–286. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiros C, Passes F, Bartolo A, Marques A, Silvas C, Pereira de A (2020) Burnout and stress measurement in police officers: literature review and a study with the operational police stress questionnaire Front Psychol 11. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer R (2008) Modeling health behavior change: how to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology: Int Rev 57(1):1–29

- Smith TD, Hughes K, DeJoy DM, Dyal MA. Assessment of relationships between work stress, work-family conflict, burnout and firefighter safety behavior outcomes. Saf Sci. 2018;103:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2017.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stamm BH. The concise ProQOL manual. 2. ID: Pocatello; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J. Police officer willingness to use stress intervention services: the role of perceived organizational support (POS), confidentiality and stigma. Int J Emerg Ment Health and Human Resilience. 2015;17(1):304–315. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner SL, White N, Fyfe T, Matthews LR, Randall C, Regehr C, Fleischmann MH. Systematic review of posttraumatic stress disorder in police officers following routine work-related critical incident exposure. Am J Ind Med. 2020;63(7):600–615. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM (1993) The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. In Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX (Vol. 462).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized numerical data will be made available upon request. Due to the sensitive nature of open-ended questions, they cannot be made available.

Files used for data analysis in JASP will be made available upon request.