Abstract

This cohort study examines whether the implementation of differentially timed restrictions in a highly interconnected metropolitan area was associated with increased interregional travel.

Introduction

In the fall of 2020, the government of Ontario, Canada, adopted a 5-tier, regional framework of public health measures for the COVID-19 pandemic in its 34 public health regions.1 The goal of nonpharmaceutical interventions was to suppress transmission by reducing contact rates, which can be indirectly assessed using mobility data. Five of the 6 most populous health regions in Ontario are located in the Greater Toronto Area: Toronto (3.0 million), Peel (1.5 million), York (1.2 million), Durham (0.7 million), and Halton (0.6 million). The urban core of Toronto and Peel is a perpetual hotspot for COVID-192 and remains highly interconnected with the peripheral regions of York, Durham, and Halton.

Toronto and Peel were the first regions in Ontario to enter the highest restriction tier (ie, lockdown) during the second wave of COVID-19. On November 23, 2020, Toronto and Peel closed restaurants to in-person dining and limited nonessential businesses, including shopping malls, to curbside pickup. York entered lockdown on December 14, 2020, followed by the rest of the province, including Durham and Halton, on December 26, 2020. In this cohort study, we examine whether the implementation of differentially timed restrictions in a highly interconnected metropolitan area was associated with increased interregional travel, potentially driving further transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

This cohort study received ethical approval from the University of Toronto research ethics board through the Ontario COVID-19 Modeling Consensus Table. Informed consent was waived because data were anonymous, and the study posed minimal risk. This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

We used anonymized mobile device data from Veraset representing 154 089 unique devices (3.4% of the population) to analyze patterns of travel by residents of regions in the urban core (Toronto and Peel) to shopping malls and restaurants in peripheral regions in the week before the November 23 lockdown compared with the week after the lockdown (eFigure in the Supplement). Restaurants and shopping malls are both important settings for transmission risk.3,4 A device’s home region for a given month was identified as where it spent most of its time during that month. The proportion of devices in the data set that visited malls or restaurants was multiplied by the population of the region (2019 estimates)5 to estimate the actual number of visitors. We also measured visits by residents of Toronto and Peel to shopping malls in York relative to a baseline calculated for each day of the week from January 1 to February 5, 2020. Neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics of devices captured in the Veraset sample are contrasted with the general population of Toronto and Peel in the eTable in the Supplement.

One-sided P values were calculated using the bayesian posterior distribution of a structural time series fit to the preintervention daily data. Statistical significance was set at P < .05, and data analysis was performed between January 2021 to June 2021 using the statistical package R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

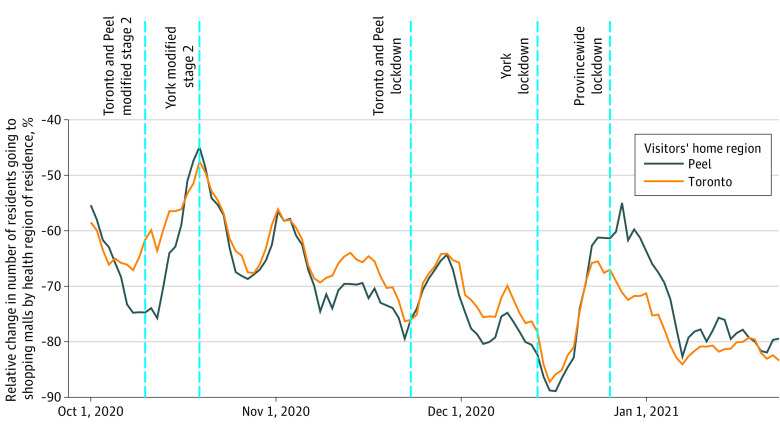

Residents of Toronto and Peel took fewer trips to shopping malls and restaurants in the week following lockdown (shopping malls: Toronto, −15.3% [95% CI, −28.5 to −5.4]; Peel, −18.2% [95% CI, −30.0 to −4.7]; restaurants: Toronto, −16.9% [95% CI, −28.8 to 0.0]; Peel, −20.2% [95% CI, −32.1 to −6.7]) (Table). During the same time, there was a significant increase in trips to shopping malls in peripheral regions by residents of the regions in lockdown (Toronto: +40.7% [95% CI, 27.0 to 56.6]; Peel: +65.5% [95% CI, 54.2 to 81.7]); however, visits to peripheral regions were still well below historical means (Figure). Visits to restaurants in peripheral regions did not decrease (Toronto: +6.3% [95% CI, −8.0 to 23.6]; Peel: +11.8% [95% CI, −6.0 to 20.9]).

Table. Estimated Number and Percent Change of Toronto and Peel Residents Visiting Shopping Malls and Restaurants in Other Regions of Ontario, One Week Before and After Lockdown (November 23, 2020)a.

| Region of travel | Shopping malls, No. (95% CI) | Change, % (95% CI) | Restaurants, No. (95% CI) | Change, % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | |||

| Residents of Toronto | ||||||

| Urban core | ||||||

| Toronto | 80 377 (71 220 to 90 715) | 56 198 (48 035 to 65 788) | −30.1 (−41.6 to −19.8) | 59 996 (52 167 to 69 010) | 47 139 (39 762 to 55 944) | −21.4 (−33.7 to −5.1) |

| Peel | 6273 (4098 to 9639) | 5131 (3054 to 8641) | −18.2 (−38.6 to −2.9) | 2437 (1235 to 4831) | 1807 (790 to 4257) | −25.9 (−39.2 to −14.7) |

| Total | 86 650 (75 318 to 100 354) | 61 329 (51 089 to 74 429) | −29.2 (−43.0 to −19.1) | 62 433 (53 402 to 73 841) | 48 946 (40 552 to 60 201) | −21.6 (−34.0 to −7.1) |

| Peripheral regions | ||||||

| York | 12 814 (9473 to 17 345) | 19 283 (14 771 to 25 225) | 50.5 (38.7 to 61.2) | 7742 (5272 to 11 401) | 8544 (5699 to 12 821) | 10.4 (−4.7 to 32.8) |

| Durham | 3776 (2195 to 6548) | 4072 (2303 to 7275) | 7.8 (−11.0 to 28.6) | 1765 (814 to 3907) | 1351 (531 to 3598) | −23.5 (−44.5 to −1.4) |

| Halton | 1736 (841 to 3821) | 2424 (1184 to 5097) | 39.6 (−7.4 to 92.6) | 499 (108 to 2059) | 744 (201 to 2709) | 49.1 (20.4 to 82.4) |

| Total | 18 326 (12 509 to 27 714) | 25 779 (18 258 to 37 597) | 40.7 (27.0 to 56.6) | 10 006 (6194 to 17 367) | 10 639 (6431 to 19 128) | 6.3 (−8.0 to 23.6) |

| Other regions | 1670 (250 to 7941) | 3179 (1025 to 10 597) | 90.4 (64.7 to 119.1) | 2385 (531 to 9795) | 2613 (665 to 10 590) | 9.6 (−16.2 to 33.4) |

| Overall | 106 646 (88 077 to 136 009) | 90 287 (70 372 to 122 623) | −15.3 (−28.5 to −5.4) | 74 824 (60 127 to 101 003) | 62 198 (47 648 to 89 919) | −16.9 (−28.8 to 0.0) |

| Residents of Peel | ||||||

| Urban core | ||||||

| Toronto | 9943 (7251 to 13 670) | 5666 (3618 to 8912) | −43.0 (−64.1 to −26.2) | 6549 (4456 to 9677) | 5296 (3348 to 8442) | −19.1 (−39.6 to 1.2) |

| Peel | 53 324 (46 434 to 61 240) | 37 255 (31 230 to 44 472) | −30.1 (−43.3 to −14.6) | 22 152 (17 877 to 27 460) | 16 101 (12 319 to 21 078) | −27.3 (−39.4 to −10.8) |

| Total | 63 267 (53 685 to 74 910) | 42 921 (34 848 to 53 384) | −32.2 (−42.5 to −20.2) | 28 701 (22 333 to 37 137) | 21 397 (15 667 to 29 520) | −25.4 (−38.9 to −7.2) |

| Peripheral regions | ||||||

| York | 3816 (2297 to 6372) | 6508 (4268 to 9945) | 70.5 (55.5 to 89.1) | 1572 (732 to 3449) | 1599 (728 to 3663) | 1.7 (−15.9 to 24.5) |

| Durham | 289 (96 to 909) | 40 (2 to 232) | −86.2 (−151.8 to −24.5) | 227 (42 to 997) | 42 (2 to 239) | −81.5 (−155.3 to −29.6) |

| Halton | 5260 (3402 to 8153) | 8948 (6274 to 12 820) | 70.1 (53.5 to 85.1) | 3373 (1972 to 5810) | 4140 (2461 to 7017) | 22.7 (0.0 to 38.3) |

| Total | 9365 (5795 to 15 434) | 15 496 (10 544 to 22 997) | 65.5 (54.2 to 81.7) | 5172 (2746 to 10 256) | 5781 (3191 to 10 919) | 11.8 (−6.0 to 20.9) |

| Other regions | 3257 (956 to 11 516) | 3690 (1105 to 12 823) | 13.3 (−2.4 to 32.8) | 2029 (468 to 8277) | 1461 (343 to 5854) | −28.0 (−49.8 to −3.6) |

| Overall | 75 889 (60 436 to 101 860) | 62 107 (46 497 to 89 204) | −18.2 (−30.0 to −4.7) | 35 902 (25 547 to 55 670) | 28 639 (19 201 to 46 293) | −20.2 (−32.1 to −6.7) |

95% CIs were calculated using the binomial confidence intervals for daily proportion of visitors and are scaled with the population of each region of residence.

Figure. Visits From Toronto and Peel Residents to Shopping Malls in York, Relative to a Baseline Calculated for Each Day of the Week From January 1 to February 5, 2020.

Toronto and Peel entered lockdown on November 23, 2020. York entered lockdown on December 14, 2020. Other regions entered lockdown on December 26, 2020.

Discussion

Lockdowns in the urban core were associated with reduced overall visits to shopping malls and restaurants by residents but were not associated with decreased travel to these businesses in peripheral regions, where restrictions permitted indoor dining and shopping for nonessential businesses. We observed a large increase in visits to shopping malls in the peripheral regions by residents of the urban center in the week following the lockdown. These heterogeneous restrictions may lead to unintended consequences, undermining lockdowns in the urban core and driving residents from zones of higher transmission to zones of lower transmission. While our sample was limited to a fraction of the population, neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics were similar to the general population. Regional nonpharmaceutical intervention frameworks could avoid these consequences by implementing restrictions spanning both the core and periphery of urban areas or using interregional travel restrictions. These concerns are likely generalizable to other major metropolitan areas, which often comprise interconnected but administratively independent regions.6

eFigure. Map of the 5 Regions Comprising the Greater Toronto Area

eTable. Neighborhood Sociodemographic Characteristics by Dissemination Area of Toronto and Peel Residents Included in the Veraset Mobile Device Sample

References

- 1.Ontario Government . COVID-19 Response Framework: Keeping Ontario Safe and Open — Lockdown Measures. Published 2020. Accessed April 13, 2021. https://files.ontario.ca/moh-covid-19-response-framework-keeping-ontario-safe-and-open-en-2020-11-24.pdf

- 2.Berry I, Soucy JR, Tuite A, Fisman D; COVID-19 Canada Open Data Working Group . Open access epidemiologic data and an interactive dashboard to monitor the COVID-19 outbreak in Canada. CMAJ. 2020;192(15):E420. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.75262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher KA, Tenforde MW, Feldstein LR, et al. ; IVY Network Investigators; CDC COVID-19 Response Team . Community and close contact exposures associated with COVID-19 among symptomatic adults ≥18 years in 11 outpatient health care facilities—United States, July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1258-1264. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang S, Pierson E, Koh PW, et al. Mobility network models of COVID-19 explain inequities and inform reopening. Nature. 2021;589(7840):82-87. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2923-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statistics Canada . Estimates of population (2016 Census and administrative data), by age group and sex for July 1st, Canada, provinces, territories, health regions (2018 boundaries) and peer groups. Published 2021. Accessed April 13, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710013401

- 6.Althouse BM, Wallace B, Case B, et al. The unintended consequences of inconsistent pandemic control policies. medRxiv. Preprint posted online October 28, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.08.21.20179473 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Map of the 5 Regions Comprising the Greater Toronto Area

eTable. Neighborhood Sociodemographic Characteristics by Dissemination Area of Toronto and Peel Residents Included in the Veraset Mobile Device Sample