Abstract

Epigenetic changes during long-term spaceflight are beginning to be studied by NASA’s twin astronauts and other model organisms. Here, we evaluate the epigenetic regulation of gene expression in space-flown C. elegans by comparing wild type and histone deacetylase (hda)-4 mutants. Expression levels of 39 genes were consistently upregulated in all four generations of adult hda-4 mutants grown under microgravity compared with artificial Earth-like gravity (1G). In contrast, in the wild type, microgravity-induced upregulation of these genes occurred a little. Among these genes, 11 contain the domain of unknown function 19 (DUF-19) and are located in a cluster on chromosome V. When compared with the 1G condition, histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) increased under microgravity in the DUF-19 containing genes T20D4.12 to 4.10 locus in wild-type adults. On the other hand, this increase was also observed in the hda-4 mutant, but the level was significantly reduced. The body length of wild-type adults decreased slightly but significantly when grown under microgravity. This decrease was even more pronounced with the hda-4 mutant. In ground-based experiments, one of the T20D4.11 overexpressing strains significantly reduced body length and also caused larval growth retardation and arrest. These results indicate that under microgravity, C. elegans activates histone deacetylase HDA-4 to suppress overregulation of several genes, including the DUF-19 family. In other words, the expression of certain genes, including negative regulators of growth and development, is epigenetically fine-tuned to adapt to the space microgravity.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Chromatin

Introduction

Environmental factors can influence not only genome instability but also epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, leading to altered gene expression, certain diseases, and aging1–5. Microgravity-induced transcriptional alterations have been observed in several spaceflight experiments, suggesting that epigenetic changes might occur in the space environment6–8. However, research on epigenetic regulation of plants and metazoans in the space environment has only just begun to be reported9,10.

Recent multi-omics analyses from more than 50 astronauts and hundreds of spaceflight samples show that mitochondrial dysregulation is a consistent and central hub of the biological effects of spaceflight11. In 2009, our C. elegans RNA Interference Space Experiment (CERISE) was conducted to evaluate RNAi activity and physiological changes during development from L1 larvae to adult under microgravity or 1G conditions12. Both transcriptome and proteome analyses showed that the expression of muscle proteins, cytoskeletal elements, and mitochondrial metabolic enzymes were decreased by microgravity12. Intriguingly, mitochondrial perturbations have been reported to activate epigenetic modifying enzymes such as histone H3K27 histone demethylases JMJD-3.1 and JMHJD-1.2 in C. elegans13. In addition, mammalian obesity and diabetic subjects have been reported to alter DNA methylation levels of several gene promoters, PGC1α and Tfam (the regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis)14,15. One of the intriguing results from the NASA Twin study shows that certain epigenetic changes in DNA methylation of immune and oxidative stress-related pathways occurred during the astronaut’s second 6-month mission10.

DNA methylation at the fifth position of cytosine (5mC) plays an important role as an epigenetic mark in mammals, but it is thought to be at low levels or absent in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans16,17. In contrast, histone modifications are widely conserved in eukaryotes, including yeasts, plants, and metazoans18–22. Histone modifications can be associated with transcriptional activation or repression through chromatin structural dynamics. For instance, acetylation and trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27ac and H3K27me3) regulate transcriptional activation and repression, respectively23,24. The level of the H3K27me3 modification is controlled by cooperation with histone deacetylases (HDACs) and methyltransferases (HMT)25,26. In particular, class IIa HDACs 4 and 5 in rat skeletal muscles are activated by hindlimb suspension, and it leads to decreased expression of myosin heavy chain and increased expression of MuRF-1 and MAFbox E3-ligases, which are involved in rat muscular atrophy27,28.

Here we conducted spaceflight experiments in the International Space Station (ISS): we grew and analyzed four consecutive generations of synchronous culture of wild-type and histone deacetylase (hda)-4 mutant C. elegans. In wild-type C. elegans, HDA-4 is expressed in the body-wall muscles and several neurons, including motor neurons and other somatic nervous systems; it is an ortholog of mammalian HDAC4 and 529–32. In our previous spaceflight experiment, CERISE, the expression of hda-4 in wild type was slightly but significantly increased under microgravity (1.49 times that observed under the artificial 1G)12. However, this CERISE space experiment investigated the effect of microgravity on gene and protein expression only in the first generation, which grows from L1 larvae to adults. It was unclear whether HDA-4 dependent epigenetic changes in response to the microgravity environment would occur not only in the first generation but also across generations. Here, we compared the wild-type and the hda-4 (ok518) mutant transcriptomes over four generations in two test environments under microgravity and artificial 1G conditions. Our results clarified the existence of HDAC-mediated epigenetic regulation in C. elegans that is reproducible in all generations under microgravity conditions.

Results

Changes in gene expression between wild type and hda-4 mutant under microgravity conditions

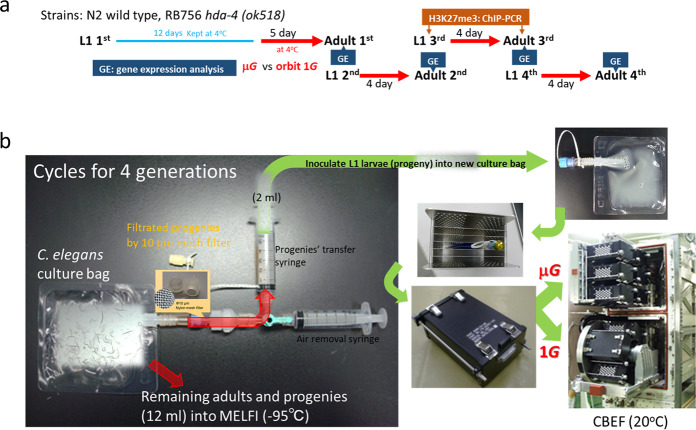

Here, we succeeded in synchronously culturing four consecutive generations of C. elegans in space microgravity by using a filtration system (Fig. 1). A 10-μm mesh filter sufficiently separated the parental adults and their progenies, and only progenies could be transferred to the new culture bag. The last culture bag contained adults (4th generation) and their progenies (5th generation larvae) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram and illustration of the spaceflight experiment to assess microgravity impact on epigenetic regulation in C. elegans.

a Diagram shows the timeline of the spaceflight experiment “EPIGENETICS”. b The start of the experiment was initiated by injecting the L1 larva solution in a syringe into a culture bag and incubating in an upper microgravity box and an artificial 1G centrifuge box of CBEF (Cell Biology Experiment Facility). After culturing for 5 days (1st generation) and 4 days (2nd to 4th generations), 2 ml of L1 larval progenies were aspirated with a syringe while being filtered through a 10 μm mesh filter, and transferred to a new culture bag. The remaining culture bags (adults and L1 progenies mixture) were frozen at −95 °C in MELFI (Minus Eighty degree Celsius Laboratory Freezer).

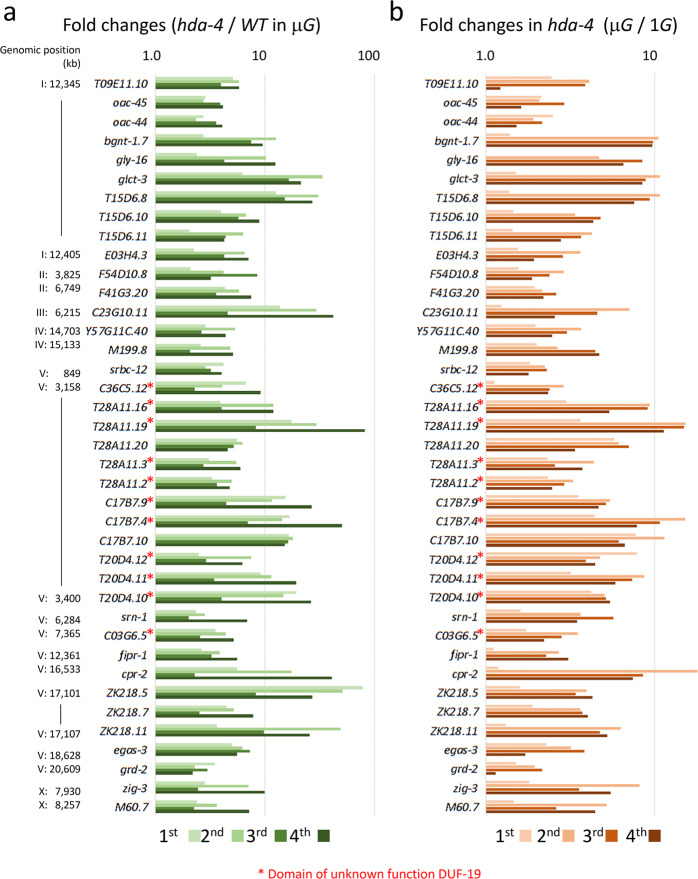

DNA microarray analyses were performed to determine the gene expression profiles of wild-type and hda-4 (ok518) deletion mutant specimens of adult hermaphrodite C. elegans synchronously cultured for four generations under microgravity and artificial 1G conditions (Fig. 1). Under microgravity, 39 genes were consistently upregulated (fold-change >2.5; P < 0.05, Student’s t test) in all four generations of the hda-4 mutant compared with the equivalent generations of wild type (Fig. 2a). In the mutant, these genes were also consistently upregulated in most (>2/4) generations under microgravity compared with artificial 1G (Fig. 2b). These 39 genes were located across all autosomal and sex chromosomes, and some were adjacent cluster genes. This suggests that the expression of these genes was epigenetically suppressed at the adjacent chromosomal level by the action of HDA-4 in response to microgravity. Many of these genes have unknown functions but some share the same domain: e.g., a cluster of 11 genes with the DUF-19 (domain of unknown function 19) on chromosome V (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Changes in gene expression induced in hda-4 (ok518) mutants grown under microgravity conditions.

a DNA microarray analysis was compared through four generations of wild-type and hda-4 mutant strains grown under microgravity in two independent replicate experiments. All 39 genes were significantly upregulated in the hda-4 mutant (>2.5-fold, p < 0.05 using Student’s t test). Statistical analysis was performed between the mean values of the four generations of wild-type and hda-4 mutants. Their chromosome positions and expression levels (fold-change values) were indicated. b Changes in gene expression (fold-change values) of 39 genes in the (a) of hda-4 mutants grown under microgravity and artificial 1G conditions. Asterisk (*) indicated genes containing a domain of unknown function DUF-19.

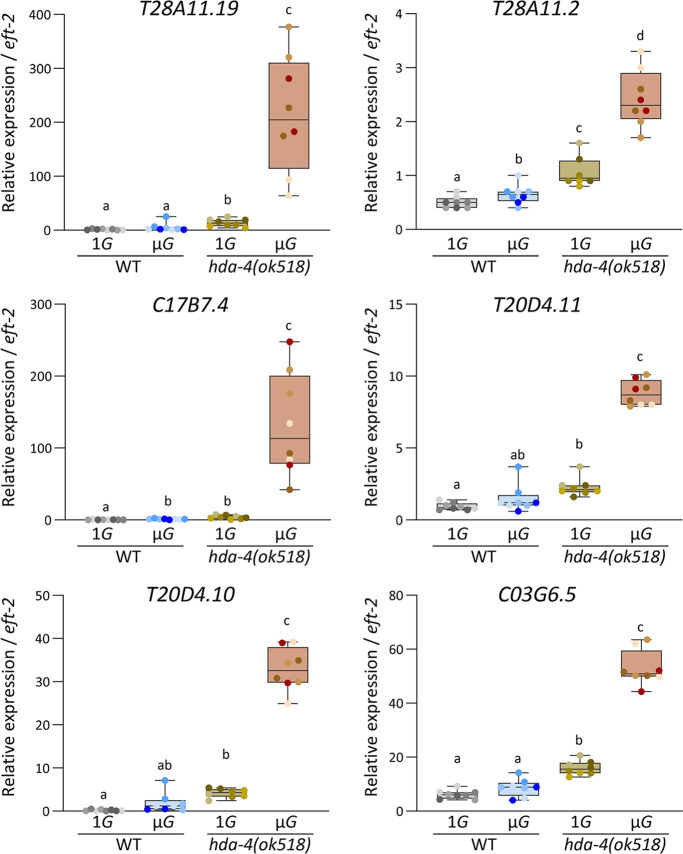

To confirm the expression changes, the transcript levels of 6 of the DUF-19–containing genes, T28A11.19, T28A11.2, C17B7.4, T20D4.11, T20D4.10, and C03G6.5, were examined by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using two independent space experiment samples. Consistent with the microarray data (Fig. 2), all showed significantly higher expression in the hda-4 (ok518) mutant than in the wild type under microgravity, and significantly higher expression in the hda-4 (ok518) mutant under microgravity than in the mutant under artificial 1G (Fig. 3). Intriguingly, under microgravity conditions, some of the genes in wild-type (C17B7.4, T28A11.2) were slightly but significantly upregulated under microgravity compared with artificial 1G (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Changes in gene expression of 6 DUF-19-containing genes, T28A11.19, T28A11.2, C17B7.4, T20D4.11, T20D4.10, and C03G6.5 assessed by quantitative real-time PCR.

Expression levels were analyzed in 8 samples each of wild-type and hda-4 mutants grown in either microgravity or artificial 1G (2 independent lines over four generations). The eft-2 gene was used as the internal standard. Data are shown as box and whiskers to indicate median and range. Statistical analysis was performed in each condition using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test.

Histone H3K27 trimethylation changes in response to microgravity

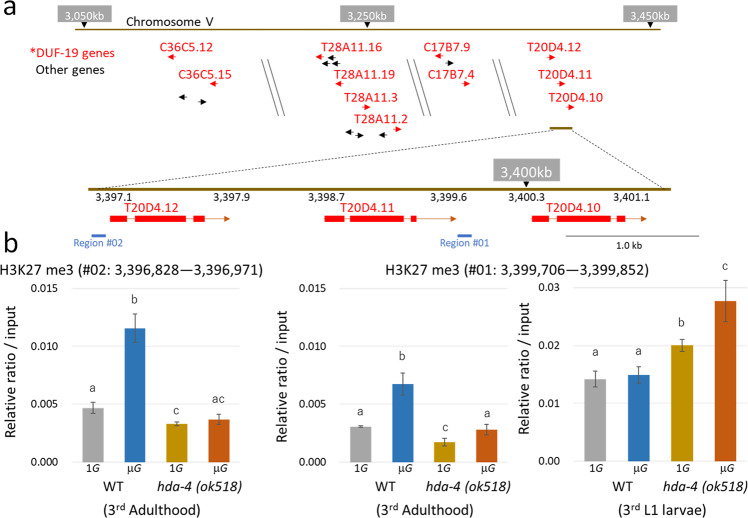

To study changes in H3K27me3 in adult C. elegans grown under microgravity, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)—genomic PCR with anti-H3K27me3 antibody was applied to the intergenic regions of the T20D4.12 to 4.10 gene locus; two regions, #01 and #02, were studied (Fig. 4a). Specimens analyzed were all 3rd-generation L1 larvae or adults. In wild-type adults, H3K27me3 levels in both regions were significantly higher under microgravity than under artificial 1G (Fig. 4b). In the hda-4 mutant, the basal level of H3K27me3 under artificial 1G was lower than that in wild type, and the degree of H3K27me3 induction by microgravity was severely reduced (Fig. 4b). In L1 larvae, H3K27me3 levels in the hda-4 mutant were higher than in the adult stage, and were slightly but significantly higher than in the wild type under both microgravity and artificial 1G (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that the sites examined in the locus of T20D4.12 to 4.10 are highly tri-methylated at the early larval stage and are maintained under silencing conditions. The state of H3K27me3 then changes via epigenetic enzymes such as HDA-4, if the specimen is subjected to microgravity during growth. We also tested epigenome changes in H3K27ac, H3K27me1, and H3K27m2 in the same locus, but all modification levels were lower and could not be further evaluated due to sample quantitative limitations.

Fig. 4. ChIP analysis of H3K27me3 levels at the T40D4.12-4.10 locus.

a H3K27me3 levels were analyzed in the intergenic region of the T40D4.12-4.10 locus on Chromosome V. The red-colored gene is a gene containing the DUF-19 domain. b The graphs show the recovery rates for region #01 and #02, as a relative ratio of DNA after ChIP with the anti-H3K27me3 monoclonal antibody compared to the input DNA in adults wild-type and hda-4 mutant, respectively. Due to the sample limitations, L1 larvae study was limited to analysis of the H3K27me3 status at the region #01. These samples (about 300 worms each) grew as third generation under artificial 1G or microgravity conditions. Biological triplications in each sample condition (n = 3) were analyzed by ChIP-qPCR using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. Error bars indicate S.D.

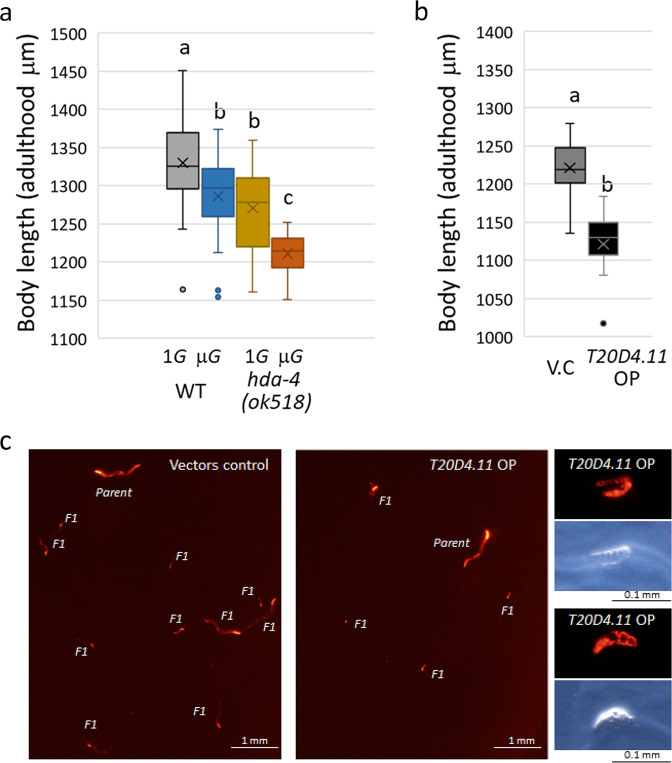

hda-4 mutant displays pronounced growth suppression in spaceflight and overexpression of the T20D4.11 gene

We have previously discovered that the C. elegans body length changes in response to environmental conditions such as fluid dynamics and microgravity12,33. Reproducible in this study, the length of wild-type C. elegans was slightly but significantly (by 3.3%, p = 0.011) reduced in adulthood when they were grown under microgravity compared with artificial 1G (Fig. 5a). This reduction was even more pronounced in the hda-4 (ok518) mutant (by 4.8%, p = 0.00001). In addition, the body thickness of the mutant was significantly reduced (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 5. Changes in body length of space-flown C. elegans.

a We plotted the length of 3rd-generation adults of wild-type and hda-4 mutants grown under artificial 1G or microgravity was indicated (n = 20<, respectively). Data are shown as box and whiskers to indicate median and range. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. b Adult length of transgenic lines of vector control and T20D4.11 driven by the myo-3 promoter grown on NGM E. coli OP-50 agar plate for 4 days (n = 10, P < 0.01 using Student’s t test). Data are shown as box and whiskers to indicate median and range. c Five L1 larvae of vector control and T20D4.11 transgenic lines were cultured on 6 cm NGM E. coli OP-50 agar plates for 7 days. The L1 larva became an adult (Parent) and its progenies (F1) were visualized with injection markers (Prab-3::mCherry, Pmyo-2::mCherry and Pmyo-3::mCherry, Supplementary Fig. 2). Several sizes of F1 progenies were observed on the vector-control line. On the other hand, in the T20D4.11 transgenic line, F1 progenies became smaller, and some dead larvae and embryos were observed (right panels).

There are more than 80 paralogs of DUF-19–containing genes in the C. elegans genome. Despite comprehensive RNAi experiments involving each of these genes, no knockdown-related phenotype has been observed34. This is because there are many DUF-19 gene families in the genome, so even if each gene function is disrupted, the phenotype may not be obtained. In addition, it may be difficult to observe the knockdown phenotype if the original genetic function adversely affects growth and survival and is usually rarely expressed. Therefore, we investigated the phenomena caused by overproduction of the DUF-19–containing gene T20D4.11 driven by the promoter of the body-wall muscle myosin myo-3 gene (Supplementary Fig. 2). The body length in adults was significantly lower (by 8.2%, p = 0.0001) in one of the T20D4.11 overexpression lines compared with the vector control (Fig. 5b). Therefore, we consider that the reason that the hda-4 mutant is shorter than the wild-type grown at microgravity is probably the higher expression of DUF-19-containing genes such as T20D4.11 (Fig. 3). In addition, the overexpressed adult hermaphrodite reduced brood size, the progenies did not hatch frequently (embryonic or early larval lethality), and many survived showed growth retardation (Fig. 5c). These results suggest that DUF-19-containing genes function as negative regulators of growth and development in response to some stress and environmental conditions.

Discussion

Here we carried out a spaceflight experiment using C. elegans to study whether some of the transcriptional changes caused by microgravity are controlled by epigenetic changes. Comprehensive gene expression analyses using the hda-4 genetic mutant and wild-type revealed that there are 39 genes whose expression in adult C. elegans in response to space microgravity is suppressed by the action of HDA-4.

Polycomb Repression Complex 2 (PRC2), which includes histone lysine methyltransferase (HMT/KMT), induces trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 and recruits HDAC and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) to further inhibit transcription35–37. In addition, HMT/KMT promotes trimethylation after deacetylation of lysine residues of histone by HDAC38. Therefore, HDACs and HMT/KMTs work together to cause epigenetic silencing. Consistent with this, a significant increase in H3K27me3 at the T20D4.12 - T20D4.10 locus under microgravity was observed in wild-type adults compared with artificial 1G, but a little in the hda-4 mutant (Fig. 4). We consider that the induction levels of these genes in microgravity-grown C. elegans are downregulated by HDA-4 to adjust to appropriate expression levels in the space environment. This microgravity-induced epigenetic modification will be reset in the germ cells of the next generation. In C. elegans spermatogenesis, epigenetic modifications occur throughout the genome39, and PRC2 maintains the state of H3K27me3 during embryogenesis40. In the embryo, H3K27me3 is enriched across genes that were silent in the parental germline41. Nine HDACs have been identified in the C. elegans genome, of which HDA-1 is primarily involved in germ cell development and embryogenesis42. HDA-1 is essential, unlike HDA-4, and knockdown-related phenotypes have been observed in embryonic lethal and defects in gonadogenesis34. Therefore, the increase in H3K27me3 at the T20D4.12 to T20D4.10 gene locus in L1 larvae may be due to HDA-1-mediated epigenome modification. In addition, this methylation may occur more strongly in adult germ cells with reduced H3K27me3 levels in the absence of HDA-4. Due to the sample limitations, this study was limited to analysis of the H3K27me3 status of 3rd-generation L1 larvae and adults, but future space experiments with C. elegans will examine more global epigenetic changes in response to microgravity.

Merkwirth et al.13 reported that perturbations in the mitochondrial electron transport chain enhance the expression of the H3K27 histone demethylases JMJD-3.1 and JMHJD-1.2 in C. elegans. This converts the H3K27me3 inactive chromosomes into the H3K27me1 active chromosomes, which transcriptionally induces several effectors of unfolding protein response in the mitochondria. Interestingly, at least 19 genes among the 39 genes identified in this study are reported to be induced by JMJD-3.1 under mitochondrial perturbation13. In particular, the DUF-19-containing genes C03G6.5, C17B7.4, C36C5.12, T20D4.10, T20D.4.11, T20D4.12, T28A11.2, T28A11.16, T28A11.19, and T28A11.20 are more than sevenfold upregulated by JMJD-3.1. Since here we found that overexpression of one of these genes, T20D4.11, negatively affected growth and development, we propose that a series of DUF-19-containing genes may be involved in growth inhibition under mitochondrial stress conditions.

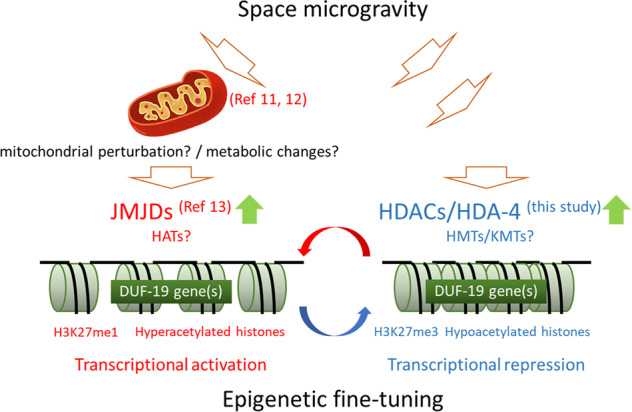

We have previously reported that space-flown C. elegans display reduced levels of mitochondrial enzymes as well as muscular and cytoskeletal proteins12. Therefore, it is speculated that mitochondrial activity is somewhat reduced and epigenetic modification by JMJDs is promoted in all four generations. It leads to upregulation of the expression of several genes, including the genes containing DUF-19. In the wild-type grown under microgravity, histone deacetylase HDA-4 and KMT are assumed to be activated in parallel, and conversely, H3K27me3 epigenetic modification is enhanced and the expression level of these genes is suppressed. Namely, certain genes including DUF-19 family, which are negative regulators of growth and development, are epigenetically fine-tuned via histone modifications to adapt to the microgravity environment (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Schematic illustration of epigenetic control by HDACs in space microgravity.

The expression of certain genes, including negative regulators of growth and development such as the DUF-19 gene(s), is epigenetically fine-tuned to adapt to the space microgravity in C. elegans.

In conclusion, here we clarified that HDAC-mediated epigenetics occurs during the growth of a metazoan species in the space microgravity environment. In the future, we expect that comprehensive tissue-specific epigenome changes associated with various histone modifications will be revealed in relation to the pathophysiological effects of long-term spaceflight.

Materials and methods

Spaceflight experiment

In this study, the N2 Bristol (wild-type) strain and RB756 hda-4 (ok518) deletion mutant were used. To synchronize the growth of the worms, an egg preparation was made in a laboratory at the Kennedy Space Center as described previously28. All L1 larvae (each strain, 9,000 worms) were kept in a 1-ml plastic syringe in M9 buffer containing 5 mg/L cholesterol (M9C) until the initiation of the experiment. The synchronized culture was started by injecting 9000 L1 larvae through a NIPRO-manufactured connection port into a NIPRO culture bag containing a 14 ml suspension of E. coli OP-50 in S-basal medium (OD600 = 5) in the International Space Station (ISS) Japanese Experiment Module KIBO. After culturing at 20 °C for about 4 days in the ISS’s Cell Biology Experiment Facility (CBEF), a 2 ml suspension of the next generation of L1 larvae was filtered through a 10 μm nylon mesh filter (Semitec Corporation, Japan) and inoculated into a new culture bag. The remaining culture bag was frozen at −95 °C in the ISS freezer MELFI. Each culture was repeated 3 times in the same way to produce samples for a total of four generations. Two independent replicate experiments were performed for each strain in microgravity and artificial 1G conditions with centrifuge in the CBEF.

Expression analyses

Approximately 1000 adult worms were collected by thawing the frozen culture samples on ice and washing them three times by natural sedimentation in ice-cold M9 buffer to remove larvae and bacterial food. RNA extraction, microarray analysis, and real-time RT-PCR analysis were performed as described previously28,29. The following primer pairs were used for PCR amplification: T28A11.19 (forward: 5ʹ-CGA GTG AGT TAG AGA GAA GAA GAA TTA GAA-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ-TCT GCT CCA AAT CCA GAA AAA GT-3ʹ), T28A11.2 (forward: 5ʹ-AAA AGA CAA CTG CAT GAA AAA GGA-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ-GCC GAC TCC GAT GAA ATG A-3ʹ), C17B7.4 (forward: 5ʹ-CGA ATT GTG CAA AAA CAT GGT T-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ-GCG AGT CCT CCT CTC CAC AAG-3ʹ), T20D4.11 (forward: 5ʹ-AGA ACT TGT GGA GGA GCC ATGT-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ-AGT CAGC GTC GCA TTG TTT G-3ʹ), T20D4.10 (forward: 5ʹ-CAG TTG CGA CTG GAG CAG AA-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ-GGA CAG ACC CAT GAT GCA AGA-3ʹ), C03G6.5 (forward: 5ʹ-GCATGAAGAAGGAGATTACTGAAACA-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ-ACC GGA AAG ATT GAC AAA TTG C-3ʹ), and eft-2 (forward: 5ʹ-GAC GCT ATC CAC AGA GGA GG-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ-TTC CTG TGA CCT GAG ACT CC-3ʹ). The real-time RT-PCR data were normalized to eft-2, which encodes an actin isoform, as a housekeeping gene. The analyses were performed in technical triplicate for each of the eight culture lines (four generations, two independent replicate experiments).

Body length measurement of space-flown and transgenic adults

The body lengths of wild-type and hda-4 mutant C. elegans that were space-flown, and C. elegans that harbored the T20D4.11 transgene and remained on Earth, were quantified using an Olympus BX51 microscope system with a DP73 digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) as described previously28,29. Observations were performed immediately after thawing the frozen samples for spaceflight and after fixing the transgenic samples with sodium azide. More than 20 worms were randomly selected for each condition of spaceflight samples.

ChIP analysis of H3K27me3 levels

ChIP assays were performed using ~300 adults from the 3rd-generation in each experimental condition, monoclonal antibody against H3K27ac, H3K27me1, H3K27m2, and H3K27me3 (MAB Institute Inc. Japan. Cat. No. MABI0309, MABI0321, MABI0324, and MABI0323), and a ChIP solution kit with anti-mouse IgG magnetic beads and control mouse IgG (MAB Institute Inc. Japan. Cat. No. MABI0822). ChIP-qPCR was performed with optimized PCR primer sets at the T40D4.12 to 4.10 locus: region #01 primer set (forward: 5ʹ-AAC AAT TCC GGC ATC AAC AT-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ-TCT GCC AAC TGT CGT TGT TC-3ʹ) and region #02 primer set (forward: 5ʹ-AAA AAG AGT CAC TTG TAA CAG GAA CA-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ-CAG TCA CTG GTG CGG TGT AA-3ʹ).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc tests in RStudio software and Student’s t test. The minimum p value for significance was 0.05. Similar alphabet(s) in any two groups indicate no significance and different alphabets in any two groups represent significant difference between the two groups.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by KIBO utilization program conducted by the Human Spaceflight Technology Directorate in JAXA, and was also supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, science and Technology, MEXT KAKENHI (15H05937 and 15K21745), and Advanced Research and Development Programs for Medical Innovation, AMED-CREST (16814305). We thank to the astronauts assigned Increment 42 successfully operated this flight experiment. We thank Dr. Motoshi Kamada for supporting the gene analysis.

Author contributions

A.Ht. and A.Hb. designed the research as the principal investigator and the co-investigator of the EPIGENETICS flight experiment, respectively. A.Ht. and T.H. contributed equally to the experimental work, and data analysis. S.Y. supervised the project of the EPIGENETICS. A.Ht. wrote the paper. Ma.T., N.H, Mi.T. R.O., and K.K. contributed to some parts of experiments. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Data availability

The data of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request. All global gene expression data are MIAME (Minimum Information about a Microarray Experiment) compliant and are deposited in the GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) database as the accession number of GSE173985.

Competing interests

A.Ht is an Associate Editor for npj Microgravity. The rest of authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Atsushi Higashitani, Toko Hashizume.

Contributor Information

Atsushi Higashitani, Email: atsushi.higashitani.e7@tohoku.ac.jp.

Akira Higashibata, Email: higashibata.akira@jaxa.jp.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41526-021-00163-7.

References

- 1.Turner BM. Epigenetic responses to environmental change and their evolutionary implications. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009;364:3403–3418. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Migliore L, Coppedè F. Environmental-induced oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders and aging. Mutat. Res. 2009;674:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang L, et al. Environmental-stress-induced chromatin regulation and its heritability. J. Carcinog. Mutagen. 2014;5:22058. doi: 10.4172/2157-2518.1000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 2012;150:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubota T. Epigenetic alterations induced by environmental stress associated with metabolic and neurodevelopmental disorders. Environ. Epigenet. 2016;2:dvw017. doi: 10.1093/eep/dvw017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berrios DC, Galazka J, Grigorev K, Gebre S, Costes SV. NASA GeneLab: interfaces for the exploration of space omics data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D1515–D1522. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutter L, et al. A new era for space life science: international standards for space omics processing. Patterns (N. Y). 2020;1:100148. doi: 10.1016/j.patter.2020.100148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis CRG, et al. Comparative transcriptomics identifies neuronal and metabolic adaptations to hypergravity and microgravity in Caenorhabditis elegans. iScience. 2020;23:101734. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou M, Sng NJ, LeFrois CE, Paul AL, Ferl RJ. Epigenomics in an extraterrestrial environment: organ-specific alteration of DNA methylation and gene expression elicited by spaceflight in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genom. 2019;20:205. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5554-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrett-Bakelman FE, et al. The NASA twins study: a multidimensional analysis of a year-long human spaceflight. Science. 2019;364:eaau8650. doi: 10.1126/science.aau8650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Silveira WA, et al. Comprehensive multi-omics analysis reveals mitochondrial stress as a central biological hub for spaceflight impact. Cell. 2020;183:1185–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higashibata A, et al. Microgravity elicits reproducible alterations in cytoskeletal and metabolic gene and protein expression in space-flown Caenorhabditis elegans. NPJ Microgravity. 2016;2:15022. doi: 10.1038/npjmgrav.2015.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merkwirth C, et al. Two conserved histone demethylases regulate mitochondrial stress-induced longevity. Cell. 2016;165:1209–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sookoian S, et al. Epigenetic regulation of insulin resistance in nonal-coholic fatty liver disease: impact of liver methylation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γcoactivator 1α promoter. Hepatology. 2010;52:1992–2000. doi: 10.1002/hep.23927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrès R, et al. Non-CpG methylation of the PGC-1alpha promoter through DNMT3B controls mitochondrial density. Cell Metab. 2009;10:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deshmukh S, Ponnaluri VC, Dai N, Pradhan S, Deobagkar D. Levels of DNA cytosine methylation in the Drosophila genome. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5119. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greer EL, et al. DNA methylation on N6-adenine in C. elegans. Cell. 2015;161:868–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millar CB, Grunstein M. Genome-wide patterns of histone modifications in yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:657–666. doi: 10.1038/nrm1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandey R, et al. Analysis of histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase families of Arabidopsis thaliana suggests functional diversification of chromatin modification among multicellular eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:5036–5055. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips T, Shaw K. Chromatin remodeling in eukaryotes. Nat. Educ. 2008;1:209. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henikoff S, Shilatifard A. Histone modification: cause or cog? Trends Genet. 2011;27:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barski A, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creyghton MP, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheung P, Lau P. Epigenetic regulation by histone methylation and histone variants. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:563–573. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Margueron R, Trojer P, Reinberg D. The key to development: interpreting the histone code? Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 2005;15:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vilchinskaya NA. Rapid decline in MyHC I(β) mRNA expression in rat soleus during hindlimb unloading is associated with AMPK dephosphorylation. J. Physiol. 2017;595:7123–7134. doi: 10.1113/JP275184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mochalova EP, Belova SP, Kostrominova TY, Shenkman BS, Nemirovskaya TL. Differences in the role of HDACs 4 and 5 in the modulation of processes regulating MAFbx and MuRF1 expression during muscle unloading. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:4815. doi: 10.3390/ijms21134815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bates EA, Victor M, Jones AK, Shi Y, Hart AC. Differential contributions of Caenorhabditis elegans histone deacetylases to huntingtin polyglutamine toxicity. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:2830–2838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3344-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Linden AM, Nolan KM, Sengupta P. KIN-29 S. I. K. regulates chemoreceptor gene expression via an MEF2 transcription factor and a class II HDAC. EMBO J. 2007;26:358–370. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenzel D, Palladino F, Jedrusik-Bode M. Epigenetics in C. elegans: facts and challenges. Genesis. 2011;49:647–661. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim W, Underwood RS, Greenwald I, Shaye DD. OrthoList 2: a new comparative genomic analysis of human and Caenorhabditis elegans genes. Genetics. 2018;210:445–461. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harada S, et al. Fluid dynamics alter Caenorhabditis elegans body length via TGF-β/DBL-1 neuromuscular signaling. NPJ Microgravity. 2016;2:16006. doi: 10.1038/npjmgrav.2016.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Worm Base | version: WS280 https://wormbase.org/species/c_elegans#401-10 (2021).

- 35.Bracken AP, Helin K. Polycomb group proteins: navigators of lineage pathways led astray in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:773–784. doi: 10.1038/nrc2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viré E, et al. The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA methylation. Nature. 2006;439:871–874. doi: 10.1038/nature04431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Vlag J, Otte AP. Transcriptional repression mediated by the human polycomb-group protein EED involves histone deacetylation. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:474–478. doi: 10.1038/70602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gordon JAR, Stein JL, Westendorf JJ, van Wijnen AJ. Chromatin modifiers and histone modifications in bone formation, regeneration, and therapeutic intervention for bone-related disease. Bone. 2015;81:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabuchi TM, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans sperm carry a histone-based epigenetic memory of both spermatogenesis and oogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4310. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06236-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaydos LJ, Wang W, Strome S. Gene repression. H3K27me and PRC2 transmit a memory of repression across generations and during development. Science. 2014;345:1515–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.1255023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaydos LJ, Rechtsteiner A, Egelhofer TA, Carroll CR, Strome S. Antagonism between MES-4 and Polycomb repressive complex 2 promotes appropriate gene expression in C. elegans germ cells. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dufourcq P, et al. Functional requirement for histone deacetylase 1 in Caenorhabditis elegans gonadogenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:3024–3034. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.9.3024-3034.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request. All global gene expression data are MIAME (Minimum Information about a Microarray Experiment) compliant and are deposited in the GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) database as the accession number of GSE173985.