Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) and the resulting neurological trauma commonly result in complete or incomplete neurological dysfunction and there are few effective treatments for primary SCI. However, the following secondary SCI, including the changes of microvasculature, inflammatory response and oxidative stress around the injury site, may provide promising therapeutic targets. The advances of nanomaterials hold promise for delivering therapeutics to alleviate secondary SCI and promote functional recovery. In this review, we highlight recent achievements of nanomaterial-based therapy, specifically targeting blood–spinal cord barrier disruption, mitigation of the inflammatory response and lightening of oxidative stress after spinal cord injury.

Keywords: : biomaterials, blood–spinal cord barrier, drug delivery, inflammation, nanotechnology, oxidative stress, secondary injury, spinal cord injury

Spinal cord injury (SCI) and the resulting neurological trauma commonly result in complete or incomplete paralysis, hypoesthesia, autonomic disorder and other sequelae. Although the incidence rate of acute SCI has remained stable in the USA, the annual cases continued to increase as the national population increased [1]. For a patient with cervical trauma, the medical expenses in the first year after the injury were about US$1 million in 2013 [2]. Due to the decline of individual independent living ability, the estimated lifetime economic burden per individual with this condition is more substantial [3,4]. In addition, problematic secondary health conditions related to SCI, such as bladder/bowel control and pain, significantly impact patients’ social participation [5]. Therefore the treatment of SCI is important for patients in terms of both medical and social problems.

Various trauma, including traffic accidents and sports or labor injuries, can destroy the stability and integrity of the spinal anatomical structure, causing traction, extrusion, rotation, contusion and tearing of the spinal cord and direct death of neurons, which is the primary injury of SCI. Because the occurrence of SCI is unpredictable, primary SCI can only be mitigated by minimizing its severity. Current decompression surgery can relieve mechanical pressure and restore the spinal stability, while systemic administration of high-dose methylprednisolone (MP) may mitigate inflammation and parenchymal edema. Even though both these regimens partially preserve neural tissue, other strategies are needed to repair the damaged tissue and promote functional recovery after SCI.

Secondary injury after SCI is the subsequent pathophysiological changes caused by the primary insult, including changes of microvasculature and the inflammatory response around the injury site. These changes are defensive responses to trauma, aiming to limit insult and maintain microenvironmental balance; however, they may also aggravate the damage, enlarge the lesion volume and arrest functional recovery. Compared with the primary injury, secondary injury progressively evolves over days to weeks [6]. It is a complex, multifaceted process and therefore offers a window of opportunity for therapeutic intervention at acute and chronic time points post SCI. Among various potential mechanisms within the secondary injury cascade, we will focus on the strategies for prevention of blood–spinal cord barrier (BSCB) disruption, mitigation of the inflammatory response and alleviation of oxidative stress.

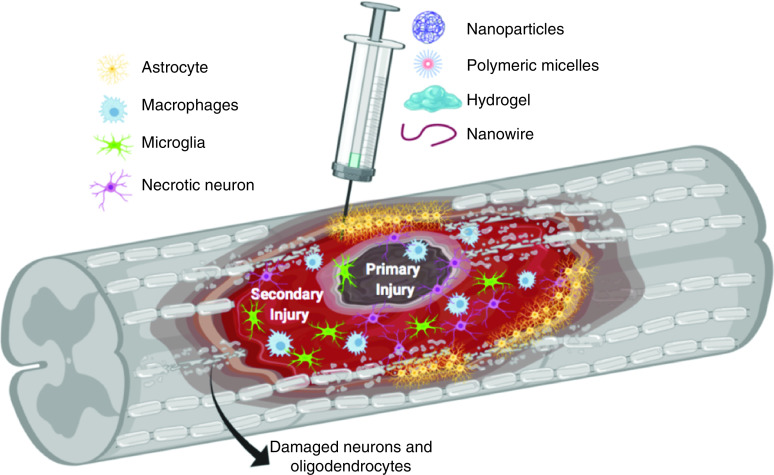

One strategy to mitigate secondary injury progression following SCI and promote neuroprotection, neurorepair and neuroregeneration is to utilize nanomaterial-based delivery systems to deliver single or multiple drugs to treat these complex pathophysiological events. Nanomaterials and their polymeric components are attractive delivery systems for the spinal cord because of their potential to cross the BSCB, delivery efficiency and targeting capability. Furthermore, some components of nanoparticles, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), can themselves slow the progression of secondary damage by several mechanisms [7,8]. In this review we will focus on therapeutic strategies for the prevention of BSCB disruption, mitigation of inflammatory response and alleviation of oxidative stress based on nanomaterial-based therapy targeting the secondary injury (Figure 1). Table 1 shows a summary of the nanomaterial-based therapy discussed in this review. Animal models used to study pathophysiology, mechanism of injury and investigate therapeutic strategies to improve functional recovery in SCI are discussed.

Figure 1. . Spinal cord injury pathology and nanomaterial-based therapies.

Table 1. . Summary of nanomaterial-based therapy for inhibiting secondary injury after spinal cord injury.

| Pathology | Nanomaterials | Therapeutic targets | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSCB disruption | Titanium nanowire | Modulating activity of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase | [9,10] |

| TiO2 nanowire | Reducing free radical and neurotoxic agents | [11] | |

| NBP nanowire | Inhibiting ER stress | [12,13] | |

| Solid lipid nanoparticle | Inhibiting ER stress | [14] | |

| Biodegradable PLGA nanoparticles | Reducing TNF-α/ROS | [15–17] | |

| Neuroinflammation | CMCht/PAMAM dendrimer nanoparticles | Reducing TNF-α/ROS | [18] |

| PLGA nanoemulsion | Reducing TNF-α/ROS | [19] | |

| Albumin nanoparticles | Reducing TNF-α/ROS | [20] | |

| PLGA nanoparticles | Inhibiting CDK-1 | [21] | |

| DS-MH chelate complex | proNGF production in microglia | [22,23] | |

| PgP polymeric micelle nanoparticles | Inhibiting PDE-4 and restoring cAMP levels | [24] | |

| PLGA-IMPs | Reducing M1 macrophage polarization and microglia activation | [25] | |

| PCL nanoparticles | Modulating the resident microglial cells | [26] | |

| MoS2 PEG nanoflowers | Inhibiting the expression of TNF-α, CD86 and iNOS; promoting the expression of Agr1, CD206 and IL-10 | [27] | |

| PMMA nanoparticles | Modulating activated macrophages and microglia | [28] | |

| Lipidoid nanoparticles | Facilitating M1-to-M2 transition | [29] | |

| PEG (MW2000) | PEG-mediated membrane repair | [30] | |

| Oxidative stress | PEG-modified silica nanoparticles | Reducing the formation of ROS and the process of lipid peroxidation of the membrane | [31] |

| PEG-coated nanozyme | Scavenging ROS | [32] | |

| MPEG–PLLA–PTMC copolymer | Modulating cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations | [33] | |

| Iron oxide nanoparticles | Attenuating free radicals | [34] | |

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles | Acrolein trapping | [35] | |

| Chitosan nanoparticles | Acrolein trapping | [36] |

BSCB: Blood–spinal cord barrier; CMCht/PAMAM: Carboxymethylchitosan/polyamidoamine; DS-MH: Dextran sulfate-minocycline hydrochloride; ER: Endoplasmic reticulum; MoS2 PEG: Molybdenum disulfide polyethylene glycol; MPEG-PLLA-PTMC: Monomethyl poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(l-lactide)-poly(trimethylene carbonate); NBP: Nanowired Dl-3-n-butylphthalide; PCL: Poly-ε-caprolactone; PDE-4: Phosphodiesterase 4; PEG: Polyethylene glycol; PgP: PLGA-graft-polyethylenimine; PLGA: Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid); PLGA-IMP: Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-immune-modifying microparticle; PMMA: Poly(methyl methacrylate); ProNGF: Pro-nerve growth factor; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; TiO2: Hydrogen titanate.

Hyperpermeability of the blood–spinal cord barrier

After a primary insult occurs, the spinal intraparenchymal blood supply, namely spinal microcirculation, will change and cannot be corrected by surgery. Along with the microhemorrhages that occur immediately and ischemia that develops progressively, the permeability of vessels change, leading to interstitial edema of the neural tissue and dysfunction of ascending/descending axonal fibers. In the spinal cord tissue, there is a similar structure to the blood–brain barrier, the BSCB, which can regulate the efflux of components from the endovascular cavity and maintain homeostasis in the neural parenchyma. As shown in Figure 2, the BSCB is composed of glial cells, pericytes, endothelial cells and tight junctions (TJs), which consist of claudins, occludin, zonula occludens and junctional adhesion molecules. Following traumatic injury, the structure of the BSCB is disrupted and its permeability is increased, which results in infiltration of immune cells and inflammatory factors entering the stroma, ultimately causing spinal cord edema and increasing intramedullary pressure [37–39]. A study about the spatial and temporal vascular changes in a rat SCI model showed maximal BSCB disruption at 24 h post injury, with significant disruption observed up to 5 days post injury [40]. Moreover, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI studies demonstrated the BSCB remained compromised at 56 days after SCI and that there was a significant link between the neurobehavioral function and the restoration of BSCB integrity [41].

Figure 2. . Blood–spinal cord barrier disruption after spinal cord injury.

BSCB: Blood–spinal cord barrier.

Several proteases, such as angiopoietins and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) regulate the integrity of BSCB. Ang1 has been verified to regulate permeability in cultured rat spinal cord microvascular endothelial cells [42]. In mouse SCI models, there was a rapid reduction of Ang1 mRNA levels at 6 h post injury. Administration of a miR-711 hairpin inhibitor after SCI significantly rescued Ang1 expression associated with the protection of epicenter blood vessels [43]. In mouse models of contusion SCI, daily intravenous injections of an Ang1 mimetic significantly reduced the amount of luciferase that extravasated into parenchyma (61 ± 13% vs vehicle group [100 ± 17%] at 72 h; p < 0.05), which suggests that Ang1 treatment reduces pathological permeability [44]. Schimke et al. combined Ang1 with nanoscaled diamond particles and implanted them into osseous defects in sheep calvaria, which demonstrated that the combination enhanced vessel growth [45]. In a moderate-compression SCI model, Mmp8 expression significantly increased and administration of an MMP8 inhibitor reduced the amount of Evans blue dye extravasation after SCI, which suggests inhibiting Mmp8 may attenuate SCI-induced BSCB breakdown [46]. Moreover, compared with wild-type SCI mice, BSCB permeability is significantly lower in Mmp8, Mmp9 or Mmp12 knockout SCI mice and this coincides with improvements in the locomotor recovery [38,47,48]. In another study, fluoxetine treatment was shown to significantly prevent BSCB breakdown and improve locomotor function after injury by inhibiting the expression of Mmp2, Mmp9 and Mmp12 [49]. Similarly, Jmjd3 mRNA depletion can simultaneously inhibit Mmp3 and Mmp9 expressions and significantly attenuate BSCB permeability [50]. Together, these data demonstrate that both Ang1 and MMPs are critical mediators of BSCB permeability after SCI.

TJs play a major role in regulating the selective permeability of the endothelium by physiologically controlling the paracellular diffusion of compounds from blood [51]. Different regulatory factors may change the permeability through affecting the expression of TJs [52–54]. In miRNA-125a-5p-overexpressing cells, the expressions of ZO-1, occludin and their mRNA significantly increased, indicating lower permeability compared with the control. By contrast, the expression of the TJ components was significantly reduced in miRNA-125a-5p-inhibited cells, coinciding with higher cell membrane permeability. The study demonstrated that miRNA-125a-5p can reduce the permeability of the BSCB by upregulating the expression of TJs [52]. In a study related to the neuroprotective effects of propofol on SCI, intravenously infused propofol suppressed the decrease in expression of occludin and claudin-5, attenuated the increase in BSCB permeability and decreased histological damage [53]. Moreover, a novel anti-inflammatory and antioxidative chemical, HO-1 fragments lacking 23 amino acids at the C-terminus (HO-1C[INCREMENT]23), was delivered by an adenoviral carrier into an SCI rat model and showed smaller reductions in TJ proteins and capillary permeability as well as better kinematic functional recovery than the control groups [54].

Another strategy to reduce secondary damage after an SCI may be restoring the BSCB integrity and reducing vascular permeability. Topical application of neurotrophins, such as growth hormones, showed that it can reduce the early manifestations of microvascular permeability disturbances and edema formation following trauma [55]. Several other studies have shown that the goal of repairing SCI can be partially achieved by mitigating changes in vascular permeability [56–58].

Some compounds, such as AP-173, AP-713 and AP-364, were delivered TiO2 based nanowires (hydrogen titanate) and evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of nanowired drugs on the breakdown of BSCB and sensory motor function after an SCI [9,10]. The nanowire is a kind of crystalline ceramic biomaterial based on TiO2 (hydrogen titanate). Compared with the normal compound, nanowired AP-713 compound significantly reduced BSCB disruption and attenuated behavioral dysfunction [9]. Because nanowires alone have no therapeutic effect, it is speculated that the nanowire can enhance the compound’s inherent neuroprotective effects. The temporal efficacy of nanowired AP-713 treatment was studied by comparing a delayed topical application (60 min after injury) with rapid administration (5 min after injury) [10]. Interestingly, the delayed application of nanowired AP-713 still had obvious therapeutic effects, whereas delayed administration of normal compound AP713 showed significantly reduced efficacy and beneficial effects compared with delayed or rapid intervention. This suggested that nanowired compounds have prolonged neuroprotective effects in SCI even when applied at a subacute time frame. Although the study did not identify the neuroprotective mechanism of nanowire, the possible reasons could be increased bioavailability and reduced biodegradation.

TiO2-nanowired growth hormone has been shown to induce longer neuroprotection after a focal SCI in rats by immediate intrathecal administration; it could significantly reduce BSCB disruption, edema formation and neuronal injuries after trauma up to 24 h after injury, whereas normal growth hormone given under identical conditions alleviated pathology only when administered after no longer than 8 h [11]. Another series of experiments explored the use of nanowired Dl-3-n-butylphthalide (NBP). When nanowired NBP was immediately applied intravenously or topically after SCI, it significantly enhanced the reduction of the BSCB breakdown and edema formation compared with NBP alone [12,13]. Because all those studies only performed short-term functional studies (no more than 24 h after injury), further studies are needed to investigate more continuous functional improvements to clarify the effectiveness of the nanowire drug-loading system.

Besides the nanowire, the solid lipid nanoparticle drug-delivery system has also been investigated in the context of repairing BSCB [14]. Although carbon monoxide-releasing molecules (CORMs) play a protective role for vessels, they have low solubility and a very short half-life (~1 min) [59]. In response to those limitations, CORM-2 was incorporated into a solid lipid nanoparticle (CORM-2-SLN). In vitro assays showed that CORM-2-SLN constantly and slowly released CO, resulting in a 50-times elongation of CO release half-life compared with that of CORM-2 in solution (50 vs 1 min half-life). In a T10 compression SCI rat model, the efficacy of CORM-2-SLN was significantly better than that of CORM-2 in solution, as demonstrated by protection of endothelial cells, inhibition of apoptosis, prevention of BSCB disruption, reduction of lesion volume and improvement of neurological outcomes. Although the exact mechanism needs to be elucidated, the superior results of CORM-2-SLN may be attributed to the constant and slow CO release by SLN.

Inflammatory response

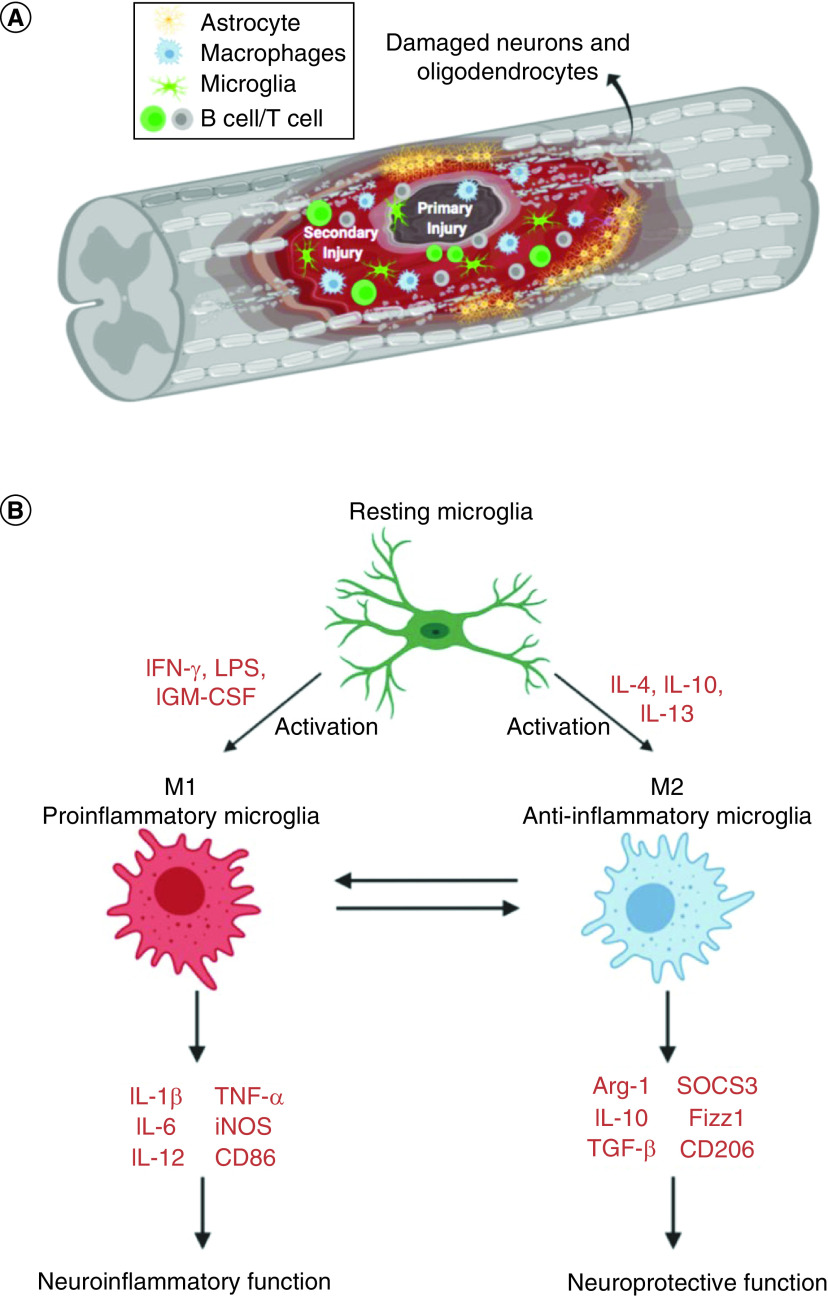

After the spinal cord is injured, not only will the morphological structure change, but also further complex pathophysiological changes will occur due to the response of various cells and the effector molecules they secrete. As shown in Figure 3A, the resting microglia will be activated in the spinal cord as the first responders due to the primary damage. Within minutes of injury, microglial cells can transform into an ameboid morphology and migrate to the injury site [60]. Accompanying increased vascular permeability, blood-derived immune cells such as neutrophils and monocytes will infiltrate the spinal cord parenchyma and exacerbate the inflammatory response. In rats, neutrophils in the parenchyma peaked in number at 24 h after SCI, while in humans neutrophils increased 15-fold in the injured spinal cord tissue 1–3 days following injury [61,62]. In both rats and humans the blood-borne monocyte/macrophages infiltrated the lesion later and were present for weeks to months after the SCI [61,62]. The role of these inflammatory cells is controversial. Several studies have shown that reducing infiltration of neutrophils or inhibiting their function can significantly improve the prognosis of an SCI [63–65]. However, another study has shown that when neutrophils were reduced 6–12 h post injury, dysfunction was aggravated, suggesting that neutrophils are beneficial for repair [66]. Similarly, macrophages also have been shown to elicit diverse functions, which will be discussed in detail later. TNF-α and IL-1β have long been considered as important cytokines potentiating the secondary injury response following an SCI [6,67–70]. However, a recent study of cytokine profile at different periods after contusion injury showed no significant change in concentrations of either TNF-α or IL-1β in the site of SCI, though there were alterations in upstream mediators of both cytokines [71]. Based on the knowledge of inflammation’s involved in spinal cord secondary injury, anti-inflammatory treatment will be the one of the therapeutic options.

Figure 3. . Inflammatory response after spinal cord injury.

Methylprednisolone

The steroidal drug MP is an FDA-approved synthetic glucocorticoid which elicits an anti-inflammatory effect in many pathological conditions. Bracken et al. first reported that systemically administered MP was effective within 8 h following an acute SCI [72]. However, Hugenholtz et al., suggested that there was insufficient evidence to support the use of high-dose MP, based on their systematic analysis of the existing clinical Level I and II evidence pertaining to MP infusion following acute SCI [73]. Although systemic administration of MP is still an option for acute human SCI, the use of high-dose steroids has significantly decreased due to side effects such as pneumonia, gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage, urinary tract infections and elongation of average hospitalization [74,75]. Thus a treatment strategy of local delivery of MP to reduce these systemic side effects is necessary.

Several nanocarrier strategies have been developed to deliver MP locally in a selective and sustained/controlled manner to modulate inflammatory responses. Biodegradable poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles (NP) have been used to deliver MP locally in the injured spinal cord [15]. In a T9–10 rat over-hemisection model, local MP-NP injection significantly reduced the number of ED-1+ macrophages/reactive microglia, decreased lesion volume and improved functional outcomes of the injured SC compared with three other groups (local non-MP nanoparticles administration, local normal MP injection and systemic administration of MP). Most importantly, the encapsulation of MP by PLGA administered near the lesion site contributed to a dramatically lower dose of MP (400 μg/animal) required to produce both cellular and functional improvements, which was approximately 5% of the systemically administered dose (7∼8 mg/animal). Aimed at eliminating side effects resulting from systemically administered MP, other similar MP nano-carriers have recently been developed to elevate plasma concentration and increase bioavailability [16,17].

MP was also delivered by carboxymethylchitosan/polyamidoamine (CMCht/PAMAM) dendrimer nanoparticles intracellularly to microglia, which elicit the first inflammatory response [18]. In an in vitro assay, sustained (14 days) release of MP by the nanoparticles was longer than that of another MP-encapsulating PLGA nanoparticle, which was reported to slowly release MP over 4 days [15]. The intracellular internalization of MP-loaded CMCht/PAMAM dendrimer nanoparticles modulated the metabolic activity of microglia cells in cell culture. At 4 weeks post-hemisection injury, SCI rats treated with MP-loaded nanoparticles recovered a weight-supporting stance of their hind limbs in the open field, whereas SCI rats in the saline-treated, nanoparticle vehicle-treated and MP solution-treated groups were only able to generate slight isolated joint movements, suggesting that recovery of locomotor function was significantly improved with MP-NP treatment. While this study showed promising behavioral recovery, it lacked relevant histological evidence and the related changes of inflammatory cytokines.

One of the advantages of nanomaterial delivery systems can be modification of surface moieties by conjugating to achieve targeted therapy. Given the upregulated expression of the albumin receptor albondin (a 60-kDa glycoprotein) at the SCI site [19], albumin can be the most suitable targeting moiety. Chen et al. evaluated the efficacy of MP delivered by an albumin-conjugated chitosan-stabilized, lecithin-emulsified, multilayered nanoemulsion (albumin-MNE) [76]. In both the beam walk test and the grid walk test, albumin-MNE-treated SCI rats performed significantly better than those treated with non-decorated MNE. In histological analysis, albumin-MNE significantly reduced the Bax-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis at SCI compared with the non-decorated MNE group. The data showed that albumin-MNE treatment improved histopathological conditions and behavior of SCI rats in a more effective manner than treatment with non-decorated MNE.

In the similar nano-drug loading system, both MP and minocycline were delivered together [19]. In the treatment of hemisectioned SCI, coadministration of MP and minocycline in an albumin-conjugated nanoemulsion significantly reduced lesion volume and improved behavioral outcomes when compared with a nonconjugated nanoemulsion. The results suggested that site-specific controlled release of therapeutics is important for the treatment of SCI.

In another study, albumin itself was also used as a nanocarrier for MP. Lin et al. developed MP-loaded albumin nanoparticles decorated with NEP1–40, a Nogo receptor antagonist, to target Nogo receptors on the neuronal cell surface. They reported that a single intrathecal injection of NEP1–40-MP-NPs reduced infiltration of immune cells and improved motor function compared with the other control groups (saline, blank NPs, MP or MP-NPs) at 28 days post injury [20].

Other anti-inflammatory drugs

The cell-cycle inhibitor flavopiridol has been shown to improve functional recovery in SCI animal models, although the systemic dose of flavopiridol may cause secretory diarrhea [77]. Flavopiridol-encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles (flavopiridol-NPs) were topically delivered in the lesion site in a rat hemisection SCI model. In the flavopiridol-NP-treated group, cell-cycle activation, glial scarring and expression of inflammatory cytokines were significantly decreased and neuronal survival and regeneration were facilitated compared with the group treated with blank NPs. The cavitation volume in the flavopiridol-NP-treated group was decreased by 90% compared with the blank-NPs-treated group. Meanwhile, the motor function recovery in the flavopiridol-NP-treated group had significantly improved at 6 weeks post injury compared with the blank-NPs treated group [21].

Minocycline hydrochloride (MH) is an antibiotic and anti-inflammatory drug and has been shown to treat secondary injury after traumatic SCI [78–81]. However, the systemic doses used in these studies are too high to be used in human patients due to hepatotoxicity. To avoid the hepatotoxicity induced by systemic high doses of MH, Zhang et al. developed dextran sulfate–MH (DS-MH) chelate complexes using divalent metal ions such as Ca2+ and Mg2+, ranging from 50 to 100 nm, for stable long-term MH release [22]. They further developed the formulation, which can release a high dose of MH for the acute stage and a low dose of MH for the chronic SCI treatment, using agarose hydrogel. The DS-MH complexes were designed to burst-release early followed by later slow release, to achieve high doses of MH at the acute stage for neuroprotection and low doses of MH at the chronic stage targeting chronic inflammation and minimizing the potential toxicity. The DS-MH complexes were embedded in injectable agarose hydrogel so that they remained localized at the injury site after the gel was injected into the intrathecal space. In a unilateral C5-level contusion injury rat model, local delivery of DS-MH complexes at a dose lower than the standard human dose (3 mg/kg) was more effective in reducing secondary injury and promoting locomotor functional recovery than systemic injection of MH alone (90–135 mg/kg) [23].

Rolipram (Rm), a PDE4 inhibitor, can restore decreased levels of intracellular cAMP in the spinal cord tissue after an SCI [82]. Although several studies have suggested that neuroprotection of Rm contributes to its potential of promoting axonal regeneration, in one study Rm-loaded nanoparticles were also demonstrated to significantly mitigate the inflammation [24]. Macks et al. developed a cationic amphiphilic copolymer, PLGA-graft-polyethylenimine (PgP) as a drug and therapeutic nucleic acid carrier; they reported that water solubility of Rm was increased up to ∼6.8-times by dissolving Rm in the hydrophobic core of the PgP micelle. They observed that administering Rm-PgP (10 μg Rm) via intraspinal injection in the spinal cord lesion site restored cAMP levels to sham animal levels, reduced apoptosis and the inflammatory response, and increased neuronal survival in the rat SCI compression injury model [24].

Immunomodulation of microglia/macrophage by nanomaterials

As mentioned above, studies have demonstrated that there are two different macrophage phenotypes in the inflammatory process (Figure 3B). The classically activated macrophage phenotype, M1, is activated by IFN-γ and secretes proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β. A second phenotype, alternatively activated macrophage or M2, is activated by IL-13 or IL-4 and reduces inflammation and promotes tissue repair. Similar to infiltrating monocytes/macrophages post-SCI, activated microglia at SCI lesion sites may also acquire a M1 or M2 polarized phenotype with divergent effects [83]. Although it is traditionally believed that the activated microglia and macrophages are difficult to distinguish from one another, recent nanotechnology can specifically regulate these inflammatory cells [25,26]. Jeong et al. investigated immune-modifying nanoparticles composed of carboxylated PLGA nanoparticles (500 μm) in a mouse SCI model and they demonstrated that carboxylated PLGA immune-modifying nanoparticles can limit infiltration of circulating inflammatory monocytes into the injury site without affecting the resident microglia [25]. In another study, Papa et al. investigated the effect of poly-ε-caprolactone-based nanoparticles loaded with minocycline (PCL-mino-NPs) on the inflammatory response associated to microglial cells in SCI. They demonstrated that the PCL-mino-NPs can be taken up to a large extent in microglia cells but minimally in recruited monocyte-derived macrophages [26].

Although several studies showed that transplantation of prestimulated macrophages into rodent SCI models improved functional recovery [84,85], a Phase II randomized controlled trial did not find a significant difference between an autologous macrophage therapy group and a control group [86]. This failed trial suggests that prestimulated macrophages might change their polarization after being transplanted in vivo so that direct modulation of the macrophage in vivo could be necessary. Several nanomaterials have been applied to deliver drugs into macrophages during in vivo studies [26–28]. The PCL-mino-NPs can efficiently decrease the activation of resident microglial cells, reduce the inflammatory response and improve the locomotor function up to 63 days post injury after acute injection following SCI compared with untreated SCI control mice [26]. Etanercept (ET), an inhibitor for TNF-α, was reported to be loaded in synthesized molybdenum disulfide PEG (MoS2@PEG) nanoflowers to treat SCI. In vitro assay demonstrated that an ET-loaded vehicle obviously inhibited M1 markers (TNF-α, CD86 and iNOS), while promoting the expression of M2 markers (Agr1, CD206 and IL-10). In a mouse SCI model, ET-MoS2@PEG effectively directed macrophages toward M2 polarization, reduced the extent of injured areas and significantly improved locomotor recovery [27]. In another study, poly(methyl methacrylate) nanoparticles were reported to enter specifically into activated microglia/macrophages and release compounds, as demonstrated by TO-PRO-3™ staining in vivo [28]. Being a fluorescent molecule for studying the nanocarrier properties, treatment with TO-PRO-3 does not induce difference from the SCI groups.

Other therapeutic agents can also be delivered in nanomaterials to regulate macrophage polarity. Because the transcription factor IRF5 can upregulate genes associated with M1 macrophages, researchers tried to silence the Irf5 gene in macrophages by intravenous injection of an siRNA-containing lipidoid nanoparticle. The results showed that silencing of Irf5 in a mouse SCI model resulted in both a dramatic M1 decrease and a significant M2 increase in the injury site, accompanied by a significant improvement of locomotor function [29].

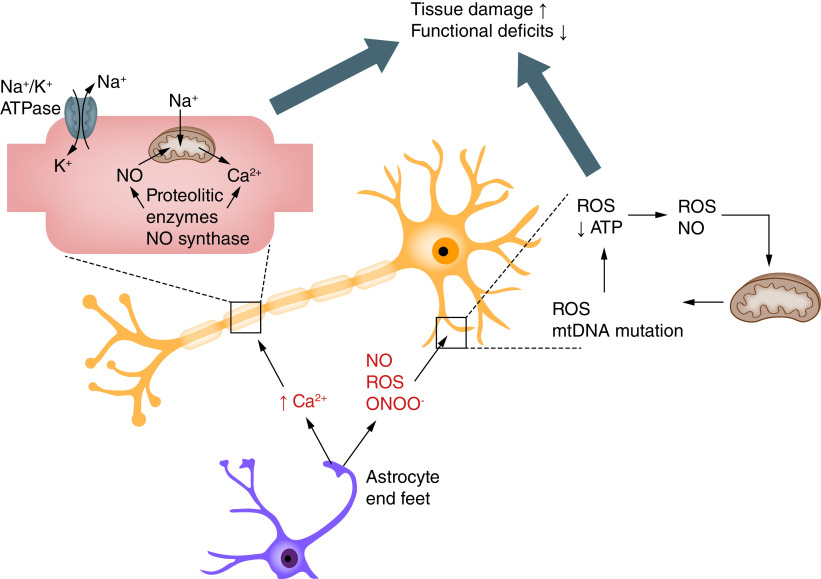

Oxidative stress

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been shown to be crucial for the progression of secondary injury and neuronal cell death. In normal conditions, constitutively produced O2 from mitochondrial metabolism is transformed by endogenous antioxidants such as superoxide dismutases. Physiologically, there is a dynamic balance between reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) generation and scavengers. Following traumatic injury, levels of ROS/RNS are rapidly elevated due to increased production beyond the normal capabilities of antioxidant systems and can further interact with lipids, nucleic acids and proteins to cause changes in the function of cellular components and, ultimately, cellular damage (Figure 4) [87–90].

Figure 4. . Oxidative stress in injured spinal cord after spinal cord injury.

NO: Nitric oxide; ROS: Reactive oxygen species.

Isaksson et al. evaluated the role of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) on the functional outcome following SCI in knockout mice lacking the iNOS gene (iNOS−/−); they reported that these mice clearly tended to have a better functional outcome than wild-type mice at 14 days post injury [91]. Therefore many researchers have been focused on reducing oxidative stress, ROS/RNS and NO production following SCI by delivering therapeutics using biomaterial-based delivery systems. Luo et al. reported that PEG, a hydrophilic polymer, can restore membrane integrity of an injured spinal cord by resealing the injured membrane after compression injury. They also reported that PEG has been shown to significantly suppress injury-induced ROS elevation and lipid peroxidation levels due to the membrane repair mechanism [30].

In another study, Cho et al. also reported that PEG can rapidly restore membrane integrity, reduce oxidative stress, restore impaired axonal conductivity and mediate functional recovery in rats, guinea pigs and dogs. However, they encountered limitations related to the concentration and the molecular weight of PEG for the application. Therefore they developed PEG-decorated silica nanoparticles (PSiNPs) and evaluated their effect on membrane-sealing ability and neuroprotective effects after spinal cord trauma. They reported that PSiNPs significantly reduced the formation of ROS and the process of lipid peroxidation of the membrane. They also reported that recovered conduction through the cord lesion in the PSiNP-treated group was much better than in the control group [31]. Nukolova et al. tried to deliver SOD1, an efficient ROS scavenger, to the lesion site to mitigate SCI-induced oxidative stress and tissue damage. They developed double-coated nanozymes by coating with anionic block copolymer, PEG-polyglutamic acid after cross-linking the polyion complex of SOD1 to poly-cation PEG-polylysine (single-coat nanozyme). They reported that the double-coated nanozymes retained their enzymatic activity and ability to protect SOD1 under physiological conditions and that a single intravenous injection of double-coated nanozymes (5 kU of SOD1/kg) produced improved locomotor function in a rat moderate SCI model [32].

In other studies, Li et al. developed zonisamide-loaded triblock copolymer nanomicelles. The antiepileptic drug zonisamide (ZNS) was loaded in triblock monomethyl PEG-poly(l-lactide)-poly(trimethylene carbonate) copolymer and ZNS-loaded nanomicelles (ZNS-Ms) were intravenously injected in hemisection SCI rats. The released ZNS from the ZNS-Ms showed significant antioxidative and neuroprotective effects as well as producing improved motor functional recovery compared with animal groups injected with free ZNS or vehicle only [33]. Similarly, iron oxide nanoparticles were shown to scavenge the free radicals after T11 complete transection injury in rats. Histological analysis showed reduced lesion volume of spinal cord tissue and significant functional motor and sensory recovery [34].

In an alternative approach to reducing oxidative stress after SCI, some researchers have also conducted studies to remove acrolein using hydrazine. Acrolein is a highly reactive aldehyde produced after CNS injury and a very potent endogenous toxin. It can be inactivated by the formation of hydralazine adjuncts on the basis of interaction between acrolein and its trapping agent, hydralzine. Cho et al. developed mesoporous silica nanoparticles with encapsulated hydralazine and functionalized with PEG. They reported that these nanoparticles showed neuroprotection to cells damaged by a usually lethal exposure to acrolein by restoring their disrupted cell membrane and improving mitochondrial function associated with oxidative stress in an in vitro acrolein-mediated cell injury model using PC-12 cells [35]. Later, they also developed a hydrazine-loaded chitosan nanoparticle to potentially provide dual benefit by using chitosan as a membrane sealer (similar to PEG) as well as hydrazine to ameliorate the damaging effects of acrolein exposure. They reported that this hydrazine-loaded chitosan nanoparticle reduced damage to membrane integrity, secondary oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in an in vitro acrolein-mediated cell injury model using PC-12 cells [36].

SCI animal models

Both small and large animal models are used to study SCI pathophysiology and investigate therapeutic strategies to improve functional recovery. Several reviews describing and comparing different SCI animal models have recently been published [92–95]. The most suitable choices for experimental SCI are rats and mice due to their size and cost, even though there are differences in anatomical, physiological and behavioral responses to injury between humans and rodents. One important difference between rat and mouse SCI models is that a modest degree of regeneration can occur at the lesion site in the mouse model that is not observed in the rat. Another important difference between the two is that a fluid-filled cystic cavity is formed after SCI in the rat model, which is consistent with human pathophysiology, while no cystic cavity formation occurs in the mouse model. For these reasons, an animal model of SCI should be chosen carefully based on the objectives of the study. Sharif-Alhoseini et al. published a systematic review of animal SCI models, analyzing study objectives, model species, injury site/method and outcome. The two most common study objectives were testing drug and growth factor interventions (36.6%) and investigating pathophysiological changes (30.2%). Rats were the most widely used species (72.4%) and the thoracic region the most common injury site (81%). Injury models included contusion (41%), transection (32.5%) and compression (19.4%) injuries, and the majority of studies (>50%) used both anatomical and behavioral assessment [92]. The authors concluded that the choice of animal model should be based on the study objectives and that contusion/compression models more closely resemble human injury, while transection models allow more unequivocal assessment of anatomical regeneration. Rodent models are cost effective and useful for discovery research and proof of principle, but there is a critical need for a transitional model between rodents and humans.

Large animals such as dogs, cats, pigs and nonhuman primates can be used as preclinical models for SCI. The first documented SCI canine model was described by Allen in 1911 [96] and this model has been used to study pathology [97] and functional outcomes [98,99] after SCI. Cats are commonly used to study locomotion following SCI [100–102]. Pigs have been a popular preclinical model due to their physiological similarity to human [103,104]. Nonhuman primates may be most useful as a preclinical SCI model due to their genetic, anatomical and physiological closeness to humans [105,106]. However, these large animal models have limitations due to size, cost, animal care and ethics, especially with respect to nonhuman primates. Nonetheless, animal models can be very important for understanding injury mechanisms, providing information on anatomical plasticity and pathophysiology of SCI and developing therapies for SCI; selection of the appropriate animal model can be the critical factor for a successful study.

Although encouraging results have been obtained in many preclinical animal studies, several barriers hinder their translation to successful human clinical trials. These include: differences in anatomy, physiology, pathology and function between experimental animal models and humans; limited standardization among SCI injury models and outcome measures; challenges with reproducibility of preclinical results; and the fact that most preclinical studies apply interventions during the acute phase of an SCI, while most human patients are in the chronic phase. Increasing success in progression from preclinical studies to clinical trials will require improved standardization and reproducibility and more widespread adoption of transitional models that bridge the pathophysiological gap between rodents and humans.

Conclusion

Continued damage to nerve cells after the primary injury can result in a secondary SCI. There are many therapeutic strategies to inhibit these secondary injuries, but one of the major hurdles is to deliver therapeutics in the injury site through the blood–brain and blood–spinal cord barriers. Here we summarized the transport of therapeutic targets using nanomaterials as a delivery system to mitigate secondary injury, such as BSCB disruption, inflammatory response and oxidative stress. Although this review may not cover all the nanomaterial-based therapeutic strategies for SCI, the research we have discussed shows the potential of nanomaterial-based delivery systems for more efficient treatment of the complex pathologies after SCI by delivering single or multiple therapeutics.

Future perspective

Secondary injury cascades after a primary insult are very complex processes and offer a therapeutic window for pharmacological treatments to prevent progressive tissue damage and improve functional outcomes. In this review, we discussed the potential of nanomaterial-based therapeutic strategies for the reduction of secondary injury in preclinical SCI animal models. We expect continued improvement in the functionality of nanomaterial-based delivery systems, improving combinatorial therapies by delivering multiple therapeutics to treat the complex pathologies of SCI.

Executive summary.

Background

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world.

Secondary injury after SCI occurs from hours to months after the primary insult and this delayed nature of secondary injury provides a therapeutic window.

Nanomaterial-based delivery systems are a promising direction for the transport of therapeutic targets to mitigate secondary injury after SCI.

This review discussed nanomaterial-based therapy, specifically targeting blood–spinal cord barrier (BSCB) disruption, mitigation of the inflammatory response and reduction of oxidative stress after SCI.

Hyperpermeability of the blood–spinal cord barrier

SCI results in BSCB damage, which increases microvasculature permeability, allows extravasation of immune cells and increases the inflammatory response around the injury site.

Several strategies using nanowire and solid lipid nanoparticle drug-delivery systems have been investigated for repairing the BSCB and improving neurological outcomes.

Inflammatory response

Reducing neutrophil infiltration or inhibiting microglial activation can significantly improve the prognosis of SCI.

The steroidal anti-inflammatory drug methylprednisolone was approved to treat acute SCI, but concerns over efficacy and side effects following high-dose systemic administration have reduced its use.

Several nanocarrier strategies to locally deliver methylprednisolone and other anti-inflammatory drugs have been developed and were shown to reduce infiltration of immune cells and production of inflammatory cytokines.

Oxidative stress

Mitochondrial dysfunction is crucial for the progression of secondary injury and neuronal cell death, and levels of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species are rapidly elevated after traumatic spinal cord injury.

Nanoparticle delivery systems have been introduced to reduce oxidative stress and tissue damage.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank K Webb in the Bioengineering Department, Clemson University for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions

J Gao reviewed the literature, wrote and edited the manuscript; M Khang reviewed the literature and drew the figures; Z Liao reviewed the manuscript and made the table; M Detloff edited the manuscript; and J Lee conceived the frame and reviewed, edited, finalized and approved the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This research was partly supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Strokes (NINDS) of the NIH under grant number 5R01 NS111037-02. This research was also partly supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the NIH under award number 5P20GM103444-07 and the South Carolina Bioengineering Center of Regeneration and Formation of Tissues (SCBioCRAFT). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Jain NB, Ayers GD, Peterson ENet al. Traumatic spinal cord injury in the United States, 1993–2012. JAMA 313(22), 2236–2243 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. J. Spinal Cord Med. 37(1), 117–118 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahabaleshwarkar R, Khanna R. National hospitalization burden associated with spinal cord injuries in the United States. Spinal Cord 52(2), 139–144 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krueger H, Noonan VK, Trenaman LM, Joshi P, Rivers CS. The economic burden of traumatic spinal cord injury in Canada. Chronic Dis. Inj. Can. 33(3), 113–122 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piatt JA, Nagata S, Zahl M, Li J, Rosenbluth JP. Problematic secondary health conditions among adults with spinal cord injury and its impact on social participation and daily life. J. Spinal Cord Med. 39(6), 693–698 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Inflammation and its role in neuroprotection, axonal regeneration and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 209(2), 378–388 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo J, Borgens R, Shi R. Polyethylene glycol improves function and reduces oxidative stress in synaptosomal preparations following spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 21(8), 994–1007 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baptiste DC, Austin JW, Zhao W, Nahirny A, Sugita S, Fehlings MG. Systemic polyethylene glycol promotes neurological recovery and tissue sparing in rats after cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 68(6), 661–676 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma HS, Ali SF, Dong Wet al. Drug delivery to the spinal cord tagged with nanowire enhances neuroprotective efficacy and functional recovery following trauma to the rat spinal cord. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1122, 197–218 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma HS, Ali SF, Tian ZRet al. Nanowired-drug delivery enhances neuroprotective efficacy of compounds and reduces spinal cord edema formation and improves functional outcome following spinal cord injury in the rat. Acta Neurochir. (106), 343–350 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muresanu DF, Sharma A, Lafuente JVet al. Nanowired delivery of growth hormone attenuates pathophysiology of spinal cord injury and enhances insulin-like growth factor-1 concentration in the plasma and the spinal cord. Mol. Neurobiol. 52(2), 837–845 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This study previously demonstrated that spatial and temporal vascular changes and blood–spinal cord barrier disruption were observed until 5 days post injury in a rat clip compression injury model.

- 12.Zheng B, Zhou Y, Zhang Het al. DL-3-n-butylphthalide prevents the disruption of blood–spinal cord barrier via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress following spinal cord injury. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 13(12), 1520–1531 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahib S, Niu F, Sharma Aet al. Potentiation of spinal cord conduction and neuroprotection following nanodelivery of DL-3-n-butylphthalide in titanium implanted nanomaterial in a focal spinal cord injury induced functional outcome, blood–spinal cord barrier breakdown and edema formation. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 146, 153–188 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi HP, Kumar H, Choi UYet al. CORM-2 solid lipid nanoparticles maintain integrity of blood–spinal cord barrier after spinal cord injury in rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 57(6), 2671–2689 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YT, Caldwell JM, Bellamkonda RV. Nanoparticle-mediated local delivery of methylprednisolone after spinal cord injury. Biomaterials 30(13), 2582–2590 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Demonstrated that local, sustained delivery of methylprednisolone by nanoparticle delivery system can enhance therapeutic effectiveness compared with systemic or local administration of MP, significantly reducing lesion volume and improving behavioral outcomes.

- 16.Qi L, Jiang H, Cui Xet al. Synthesis of methylprednisolone loaded ibuprofen modified dextran based nanoparticles and their application for drug delivery in acute spinal cord injury. Oncotarget 8(59), 99666–99680 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karabey-Akyurek Y, Gurcay AG, Gurcan Oet al. Localized delivery of methylprednisolone sodium succinate with polymeric nanoparticles in experimental injured spinal cord model. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 22(8), 972–981 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerqueira SR, Oliveira JM, Silva NAet al. Microglia response and in vivo therapeutic potential of methylprednisolone-loaded dendrimer nanoparticles in spinal cord injury. Small 9(5), 738–749 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bin S, Zhou N, Pan J, Pan F, Wu XF, Zhou ZH. Nano-carrier mediated co-delivery of methyl prednisolone and minocycline for improved post-traumatic spinal cord injury conditions in rats. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 43(6), 1033–1041 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y, Li C, Li J, Deng Ret al. NEP1-40-modified human serum albumin nanoparticles enhance the therapeutic effect of methylprednisolone against spinal cord injury. J Nanobiotechnology 17(1), 12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren H, Han M, Zhou Jet al. Repair of spinal cord injury by inhibition of astrocyte growth and inflammatory factor synthesis through local delivery of flavopiridol in PLGA nanoparticles. Biomaterials 35(24), 6585–6594 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z, Wang Z, Nong J, Nix CA, Ji HF, Zhong Y. Metal ion-assisted self-assembly of complexes for controlled and sustained release of minocycline for biomedical applications. Biofabrication 7(1), 015006 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z, Nong J, Shultz RBet al. Local delivery of minocycline from metal ion-assisted self-assembled complexes promotes neuroprotection and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Biomaterials 112, 62–71 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macks C, Gwak SJ, Lynn M, Lee JS. Rolipram-loaded polymeric micelle nanoparticle reduces secondary injury after rat compression spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 35(3), 582–592 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrated that a single local injection of rolipram-loaded polymeric micelle, PgP nanoparticles restored cAMP in the SCI lesion site and reduced apoptosis and inflammatory response in a rat compression injury model.

- 25.Jeong SJ, Cooper JG, Ifergan Iet al. Intravenous immune-modifying nanoparticles as a therapy for spinal cord injury in mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 108, 73–82 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papa S, Caron I, Erba Eet al. Early modulation of pro-inflammatory microglia by minocycline loaded nanoparticles confers long lasting protection after spinal cord injury. Biomaterials 75, 13–24 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun G, Yang S, Cai Het al. Molybdenum disulfide nanoflowers mediated anti-inflammation macrophage modulation for spinal cord injury treatment. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 549, 50–62 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papa S, Ferrari R, De Paola Met al. Polymeric nanoparticle system to target activated microglia/macrophages in spinal cord injury. J. Control. Release 174(1), 15–26 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Liu Y, Xu H, Fu Q. Nanoparticle-delivered IRF5 siRNA facilitates M1 to M2 transition, reduces demyelination and neurofilament loss, and promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. Inflammation 39(5), 1704–1717 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo J, Borgens R, Shi R. Polyethylene glycol immediately repairs neuronal membranes and inhibits free radical production after acute spinal cord injury. J. Neurochem. 83(2), 471–480 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho Y, Shi R, Ivanisevic A, Borgens BR. Functional silica nanoparticle-mediated neuronal membrane sealing following traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 88(7), 1433–1444 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrated that PEG-decorated silica nanoparticles can restore membrane integrity and reduce leakage of lactate dehydrogenase from damaged cells compared with uncoated particles or PEG alone, as well as reducing the formation of reactive oxygen species and the process of lipid peroxidation of the membrane in a guinea pig contusion SCI model.

- 32.Nukolova NV, Aleksashkin AD, Abakumova TOet al. Multilayer polyion complex nanoformulations of superoxide dismutase 1 for acute spinal cord injury. J. Control. Release 270, 226–236 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li JL, Deng JJ, Yuan JXet al. Zonisamide-loaded triblock copolymer nanomicelles as a novel drug delivery system for the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Int. J. Nanomedicine 12, 2443–2456 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pal A, Singh A, Nag TC, Chattopadhyay P, Mathur R, Jain S. Iron oxide nanoparticles and magnetic field exposure promote functional recovery by attenuating free radical-induced damage in rats with spinal cord transection. Int. J. Nanomedicine 8, 2259–2272 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho Y, Shi R, Borgens RB, Ivanisevic A. Functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticle-based drug delivery system to rescue acrolein-mediated cell death. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 3(4), 507–519 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho Y, Shi R, Ben Borgens R. Chitosan nanoparticle-based neuronal membrane sealing and neuroprotection following acrolein-induced cell injury. J. Biol. Eng. 4(1), 2 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Popovich PG, Horner PJ, Mullin BB, Stokes BT. A quantitative spatial analysis of the blood–spinal cord barrier I. Permeability changes after experimental spinal contusion injury. Exp. Neurol. 142(2), 258–275 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noble LJ, Donovan F, Igarashi T, Goussev S, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases limit functional recovery after spinal cord injury by modulation of early vascular events. J. Neurosci. 22(17), 7526–7535 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X, Bin LC, Yang DGet al. Dynamic changes in intramedullary pressure 72 hours after spinal cord injury. Neural Regen. Res. 14(5), 886–895 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Figley SA, Khosravi R, Legasto JM, Tseng YF, Fehlings MG. Characterization of vascular disruption and blood–spinal cord barrier permeability following traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 31(6), 541–552 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This study previously demonstrated that spatial and temporal vascular changes and blood–spinal cord barrier disruption were observed until 5 days post injury in a rat clip compression injury model.

- 41.Cohen DM, Patel CB, Ahobila-Vajjula Pet al. Blood–spinal cord barrier permeability in experimental spinal cord injury: dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. NMR Biomed. 22(3), 332–341 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X, Zhou X, Yuan W. The angiopoietin1-Akt pathway regulates barrier function of the cultured spinal cord microvascular endothelial cells through Eps8. Exp. Cell Res. 328(1), 118–131 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sabirzhanov B, Matyas J, Coll-Miro Met al. Inhibition of microRNA-711 limits angiopoietin-1 and Akt changes, tissue damage, and motor dysfunction after contusive spinal cord injury in mice. Cell Death Dis. 10(11), 839 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han S, Arnold SA, Sithu SDet al. Rescuing vasculature with intravenous angiopoietin-1 and αvβ3 integrin peptide is protective after spinal cord injury. Brain 133(4), 1026–1042 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schimke MM, Stigler R, Wu Xet al. Biofunctionalization of scaffold material with nano-scaled diamond particles physisorbed with angiogenic factors enhances vessel growth after implantation. Nanomedicine 12(3), 823–833 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar H, Jo MJ, Choi Het al. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 inhibition prevents disruption of blood–spinal cord barrier and attenuates inflammation in rat model of spinal cord injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 55(3), 2577–2590 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JY, Choi HY, Ahn HJ, Ju BG, Yune TY. Matrix metalloproteinase-3 promotes early blood–spinal cord barrier disruption and hemorrhage and impairs long-term neurological recovery after spinal cord injury. Am. J. Pathol. 184(11), 2985–3000 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wells JEA, Rice TK, Nuttall RKet al. An adverse role for matrix metalloproteinase 12 after spinal cord injury in mice. J. Neurosci. 23(31), 10107–10115 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JY, Kim HS, Choi HY, Oh TH, Yune TY. Fluoxetine inhibits matrix metalloprotease activation and prevents disruption of blood–spinal cord barrier after spinal cord injury. Brain 135(8), 2375–2389 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee JY, Na WH, Choi HY, Lee KH, Ju BG, Yune TY. Jmjd3 mediates blood–spinal cord barrier disruption after spinal cord injury by regulating MMP-3 and MMP-9 expressions. Neurobiol. Dis. 95, 66–81 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bazzoni G, Dejana E. Endothelial cell-to-cell junctions: molecular organization and role in vascular homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 84(3), 869–901 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang J, Nie Z, Zhao H, Gao K, Cao Y. MiRNA-125a-5p attenuates blood–spinal cord barrier permeability under hypoxia in vitro. Biotechnol. Lett. 42(1), 25–34 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie LJ, Huang JX, Yang Jet al. Propofol protects against blood-spinal cord barrier disruption induced by ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Regen. Res. 12(1), 125–132 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang S, Bi Y, Meng X, Qu L, Cao Y. Adenovirus-delivered GFP-HO-1CΔ23 attenuates blood–spinal cord barrier permeability after rat spinal cord contusion. Neuroreport 29(5), 402–407 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nyberg F, Sharma HS. Repeated topical application of growth hormone attenuates blood–spinal cord barrier permeability and edema formation following spinal cord injury: an experimental study in the rat using Evans blue, I-sodium and lanthanum tracers. Amino Acids 23(1–3), 231–239 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang H, Wu Y, Han Wet al. Hydrogen sulfide ameliorates blood-spinal cord barrier disruption and improves functional recovery by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent autophagy. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 858 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou X, Yang Y, Wu Let al. Brilliant blue G inhibits inflammasome activation and reduces disruption of blood–spinal cord barrier induced by spinal cord injury in rats. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 6359–6366 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park CS, Lee JY, Choi HY, Ju BG, Youn I, Yune TY. Protocatechuic acid improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury by attenuating blood–spinal cord barrier disruption and hemorrhage in rats. Neurochem. Int. 124, 181–192 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Motterlini R, Mann BE, Foresti R. Therapeutic applications of carbon monoxide-releasing molecules. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 14(11), 1305–1318 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.David S, Kroner A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12(7), 388–399 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Discussed that macrophages and microglia are activated following spinal cord injury and that harnessing their anti-inflammatory properties by modulating their polarization states can reduce secondary injury and promote repair.

- 61.Carlson SL, Parrish ME, Springer JE, Doty K, Dossett L. Acute inflammatory response in spinal cord following impact injury. Exp. Neurol. 151(1), 77–88 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fleming JC, Norenberg MD, Ramsay DAet al. The cellular inflammatory response in human spinal cords after injury. Brain 129(12), 3249–3269 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taoka Y, Okajima K, Murakami K, Johno M, Naruo M. Role of neutrophil elastase in compression-induced spinal cord injury in rats. Brain Res. 799(2), 264–269 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pellegatta F, Lu Y, Radaelli Aet al. Drug-induced in vitro inhibition of neutrophil–endothelial cell adhesion. Br. J. Pharmacol. 118(3), 471–476 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gok B, Okutan O, Beskonakli E, Palaoglu S, Erdamar H, Sargon MF. Effect of immunomodulation with human interferon-β on early functional recovery from experimental spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976). 32(8), 873–880 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stirling DP, Liu S, Kubes P, Yong VW. Depletion of Ly6G/Gr-1 leukocytes after spinal cord injury in mice alters wound healing and worsens neurological outcome. J. Neurosci. 29(3), 753–764 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang CX, Olschowka JA, Wrathall JR. Increase of interleukin-lβ mRNA and protein in the spinal cord following experimental traumatic injury in the rat. Brain Res. 759(2), 190–196 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McTigue DM, Tani M, Krivacic Ket al. Selective chemokine mRNA accumulation in the rat spinal cord after contusion injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 53(3), 368–376 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hermann GE, Rogers RC, Bresnahan JC, Beattie MS. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces cFOS and strongly potentiates glutamate-mediated cell death in the rat spinal cord. Neurobiol. Dis. 8(4), 590–599 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Detloff MR, Fisher LC, McGaughy V, Longbrake EE, Popovich PG, Basso DM. Remote activation of microglia and pro-inflammatory cytokines predict the onset and severity of below-level neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury in rats. Exp. Neurol. 212(2), 337–347 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mukhamedshina YO, Akhmetzyanova ER, Martynova EV, Khaiboullina SF, Galieva LR, Rizvanov AA. Systemic and local cytokine profile following spinal cord injury in rats: a multiplex analysis. Front. Neurol. 8, 581 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WFet al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N. Engl. J. Med. 322(20), 1405–1411 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Clinical study for the efficacy and safety of methylprednisolone in patients with acute SCI. Reported that patients treated with methylprednisolone in the dose used in this study improve neurological recovery when the drug was given in the first 8 h post injury.

- 73.Hugenholtz H, Cass DE, Dvorak MFet al. High-dose methylprednisolone for acute closed spinal cord injury – only a treatment option. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 29(3), 227–235 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schroeder GD, Kwon BK, Eck JC, Savage JW, Hsu WK, Patel AA. Survey of cervical spine research society members on the use of high-dose steroids for acute spinal cord injuries. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976). 39(12), 971–977 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Choi SH, Sung ho C, Heo DR, Jeong SY, Kang CN. Incidence of acute spinal cord injury and associated complications of methylprednisolone therapy: a national population-based study in South Korea. Spinal Cord 58(2), 232–237 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen XG, Hua F, Wang SG, Tang HH. Albumin-conjugated lipid-based multilayered nanoemulsion improves drug specificity and anti-inflammatory potential at the spinal cord injury gsite after intravenous administration. AAPS PharmSciTech. 19(2), 590–598 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rudek MA, Bauer KS, Lush RMet al. Clinical pharmacology of flavopiridol following a 72-hour continuous infusion. Ann. Pharmacother. 37(10), 1369–1374 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Festoff BW, Ameenuddin S, Arnold PM, Wong A, Santacruz KS, Citron BA. Minocycline neuroprotects, reduces microgliosis, and inhibits caspase protease expression early after spinal cord injury. J. Neurochem. 97(5), 1314–1326 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee SM, Yune TY, Kim SJet al. Minocycline reduces cell death and improves functional recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma 20(10), 1017–1027 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stirling DP, Khodarahmi K, Liu Jet al. Minocycline treatment reduces delayed oligodendrocyte death, attenuates axonal dieback, and improves functional outcome after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 24(9), 2182–2190 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yune TY, Lee JY, Jung GYet al. Minocycline alleviates death of oligodendrocytes by inhibiting pro-nerve growth factor production in microglia after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 27(29), 7751–7761 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pearse DD, Pereira FC, Marcillo AEet al. cAMP and Schwann cells promote axonal growth and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 10(6), 610–616 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrated that rolipram can inhibit cAMP hydrolysis by PDE4 and promote significant supraspinal and proprioceptive axon sparing and myelination when combined with Schwann cell grafts in a rat contusion SCI model.

- 83.Miron VE, Boyd A, Zhao J-Wet al. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 21(3), 226–240 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rapalino O, Lazarov-Spiegler O, Agranov Eet al. Implantation of stimulated homologous macrophages results in partial recovery of paraplegic rats. Nat. Med. 4(7), 814–821 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bomstein Y, Marder JB, Vitner Ket al. Features of skin-coincubated macrophages that promote recovery from spinal cord injury. J. Neuroimmunol. 142(1–2), 10–16 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lammertse DP, Jones LAT, Charlifue SBet al. Autologous incubated macrophage therapy in acute, complete spinal cord injury: results of the Phase 2 randomized controlled multicenter trial. Spinal Cord 50(9), 661–671 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu D, Sybert TE, Qian H, Liu J. Superoxide production after spinal injury detected by microperfusion of cytochrome c. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 25(3), 298–304 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Time course study of superoxide production in injured spinal cord using a novel microcannula perfusion technique; demonstrated that superoxide level in the extracellular space increased to approximately twice the basal level and remained elevated for over 10 h post injury.

- 88.Bao F, Liu D. Hydroxyl radicals generated in the rat spinal cord at the level produced by impact injury induce cell death by necrosis and apoptosis: protection by a metalloporphyrin. Neuroscience 126(2), 285–295 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Qian H, Liu D. The time course of malondialdehyde production following impact injury to rat spinal cord as measured by microdialysis and high pressure liquid chromatography. Neurochem. Res. 22(10), 1231–1236 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xiong Y, Rabchevsky AG, Hall ED. Role of peroxynitrite in secondary oxidative damage after spinal cord injury. J. Neurochem. 100(3), 639–649 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Isaksson J, Farooque M, Olsson Y. Improved functional outcome after spinal cord injury in iNOS-deficient mice. Spinal Cord 43(3), 167–170 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sharif-Alhoseini M, Khormali M, Rezaei Met al. Animal models of spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 55(8), 714–721 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Systematic review of SCI animal models analyzing study objectives, model species, injury site/method and outcome assessments.

- 93.Nardone R, Florea C, Höller Yet al. Rodent, large animal and non-human primate models of spinal cord injury. Zoology 123, 101–114 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Geissler SA, Schmidt CE, Schallert T. Rodent models and behavioral outcomes of cervical spinal cord injury. J. Spine (Suppl. 4), 001 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Steward O, Willenberg R. Rodent spinal cord injury models for studies of axon regeneration. Exp. Neurol. 287, 374–383 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Allen AR. Surgery of experimental lesion of spinal cord equivalent to crush injury of fracture dislocation of spinal column: a preliminary report. J. Am. Med. Assoc. LVII(11), 878–880 (1911). [Google Scholar]

- 97.Spitzbarth I, Moore SA, Stein VMet al. Current insights into the pathology of canine intervertebral disc extrusion-induced spinal cord injury. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 595796 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Olby N, Mb V, Levine Jet al. Long-term functional outcome of dogs with severe injuries of the thoracolumbar. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 222(6), 762–769 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Olby NJ, De Risio L, Muñana KRet al. Development of a functional scoring system in dogs with acute spinal cord injuries. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62(10), 1624–1628 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rossignol S, Frigon A. Recovery of locomotion after spinal cord injury: some facts and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34, 413–440 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rossignol S, Bouyer L, Langlet Cet al. Determinants of locomotor recovery after spinal injury in the cat. Prog. Brain Res. 143, 163–172 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Alizadeh A, Dyck SM, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S. Traumatic spinal cord injury: an overview of pathophysiology, models and acute injury mechanisms. Front. Neurol. 10, 282 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee JHT, Jones CF, Okon EBet al. A novel porcine model of traumatic thoracic spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 30(3), 142–159 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kuluz J, Samdani A, Benglis Det al. Pediatric spinal cord injury in infant piglets: description of a new large animal model and review of the literature. J. Spinal Cord Med. 33(1), 43–57 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rosenzweig ES, Courtine G, Jindrich DLet al. Extensive spontaneous plasticity of corticospinal projections after primate spinal cord injury. Nat. Neurosci. 13(12), 1505–1512 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Slotkin JR, Pritchard CD, Luque Bet al. Biodegradable scaffolds promote tissue remodeling and functional improvement in non-human primates with acute spinal cord injury. Biomaterials 123, 63–76 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]