Abstract

Autistic girls’ heightened social motivation and associated social coping strategies, such as camouflaging, mean they may be less likely to receive appropriate support in mainstream schools. In this research, a multi-informant approach was used to examine the camouflaging strategies used by autistic girls within specialist resource classes attached to mainstream schools (whereby girls transition between resource classes and mainstream classes). Semi-structured interviews were conducted with eight adolescent girls, their parents (eight mothers) and their educators (six teaching assistants/aides and one senior staff member) about the girls’ camouflaging experiences. Using reflexive thematic analysis, four themes were identified: (1) inconsistencies and contradictions in camouflaging, (2) challenges of relationships and ‘finding a tribe’, (3) learning, inclusion and awareness and (4) consequences of camouflaging. These results highlight the challenges that the girls experienced when attempting to hide their autism and fit within both mainstream classes and specialist resource classes. These challenges had significant impacts on the girls’ relationships and learning, as well as consequences for their mental health. The findings highlight the need for increased awareness of how camouflaging presents across the autism spectrum and suggests that individualised, evidence-based support will be essential for enabling autistic girls to flourish in school.

Lay abstract

There are a range of different types of schools that support children diagnosed with autism, including mainstream schools (where pupils are taught in general classrooms) and specialist schools (where pupils are exclusively taught alongside other children with special educational needs). An intermediary option involves resource bases attached to mainstream schools, which enable children to transition between mainstream and specialist educational settings. Autistic girls use a variety of strategies to negotiate the expectations and demands of school life. One of these strategies is known as camouflaging. This involves ‘hiding’ autism-based behaviours and developing ways to manage social situations, with the aim of fitting in with others. Research has shown that camouflaging can help to meet social expectations and friendships, but it can also result in challenges, including exhaustion and anxiety. In this study, we conducted detailed interviews with eight autistic girls, their parents and their school staff. The results showed that the girls tried to use camouflaging strategies to hide their autism and learning needs, especially within mainstream classrooms. Their camouflaging was often unsuccessful, which affected their relationships and sense of belonging. They also found camouflaging exhausting and distressing, which may (when combined with the demands of the classroom) affect their relationships, learning and mental health. This research provides important implications for supporting autistic girls who attend resource bases. These focus around increasing awareness of camouflaging and ways to support autistic girls, so they are included and able to fully participate and learn within school.

Keywords: autism, camouflaging, education, females, resource bases, special educational needs

Over the last decade, research examining gender differences among autistic people has reported that the needs of autistic girls and women may be under-recognised due to differences in their presentation (Dean et al., 2017; Dworzynski et al., 2012; Hiller et al., 2014). These differences, alongside relative strengths in social communication and motivation, often result in them developing camouflaging strategies to mask their difficulties and blend in with their peers (Dean et al., 2017; Hiller et al., 2014; Hull, Lai, Baron-Cohen et al., 2019; Lai et al., 2015, although see Kaat et al., 2020, for conflicting findings).

Camouflaging can be understood as a discrepancy between seemingly atypical, internalised social/cognitive abilities and seemingly neurotypical, externalised behaviours (Lai et al., 2017). Camouflaging is thought to differ according to gender, with autistic women being more likely to attempt to camouflage their autism and blend in with peers than autistic men (Hull, Lai, Baron-Cohen et al., 2019). Camouflaging has been associated with exhaustion, anxiety and depression (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019; Hull et al., 2017; Lai et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2016). For many autistic people, these aspects are further exacerbated by uncertainty regarding the success of their camouflaging, alongside concerns about the impact of camouflaging upon their identity (Bargiela et al., 2016; Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019; Hull et al., 2017). This may be particularly pertinent in adolescence, as this is recognised as an important time for the development of self (Blakemore, 2018). As such, timely identification and diagnosis of autism may help to foster a positive sense of identity and well-being (Bargiela et al., 2016; Leedham et al., 2020).

Limited research has examined camouflaging during adolescence, despite this being the point at which the complexity and intensity of social demands can become overwhelming (Cook et al., 2017; Kopp & Gillberg, 2011; Tierney et al., 2016). This is often compounded by the transition to mainstream secondary school when children are 11 years of age (Neal & Frederickson, 2016; Tobin et al., 2012). The increased social demands of this larger school environment can present significant challenges for autistic girls (e.g. due to sensory distress, gender expectations and an inability to interpret unspoken rules; Cridland et al., 2014; Tierney et al., 2016). Although social demands are also recognised for autistic girls attending specialist schools (where pupils are exclusively taught alongside other children with special educational needs (SEN); Wild, 2019), there has been much less research examining the impact of these on camouflaging. In one of the few studies addressing this topic, Cook et al. (2017) examined contrasting (specialist and mainstream) school contexts for 11 autistic girls and their parents. Using semi-structured interviews to explore camouflaging, friendships and bullying, they found similarities and differences in friendships and camouflaging according to school provision. Specifically, girls in both mainstream and specialist schools developed friendships with other girls with SEN, which enabled them to feel accepted and reduced the requirement to camouflage. Yet, friendship challenges and isolation were described by the girls in both settings too. Camouflaging strategies were identified by parents of girls in mainstream settings, but less so in specialist settings, perhaps reflecting differences in autism awareness and support, different ‘benchmarks’ of expected behaviours and individual differences.

Resource bases attached to mainstream schools aim to offer the advantages of both specialist and mainstream educational provision. Research examining autism resource bases describe protective features such as a ‘safe’ base, staff with specialised knowledge, individualised support and curriculum flexibility (Bond & Hebron, 2016; Croydon et al., 2019; Hebron & Bond, 2017). This specialist setting may reduce the pressure for autistic pupils to camouflage their needs, enabling them to meet their academic and social potential. Resource bases may also increase peer awareness and understanding, which are important features of social inclusion and a key requirement for reducing camouflaging (Hull et al., 2017).

The aim of the current research was to examine whether autistic girls educated in resource bases attached to mainstream schools used camouflaging strategies. We also aimed to examine the motivations and consequences of using these camouflaging strategies. The nature of camouflaging means that characteristics of autism (and associated needs) are often subtle and hidden within school, with staff expressing surprise at the social and emotional distress that autistic girls experience (Bargiela et al., 2016; Dean et al., 2017). The current study therefore aimed to bring together the experiences of autistic girls, their parents and their educators, enabling a rich and multifaceted picture of the girls’ camouflaging.

Method

Participants

Due to the small numbers of girls attending autism resource bases, purposive sampling was used to recruit participants. A total of eight triads (girl/parent/educator) took part in the study across three schools in South-East England. As can be seen in Table 1, the girls were between 12 and 15 years of age (M = 13 years 7 months; SD = 11.17 months), all had received a clinical diagnosis of autism and most had co-occurring diagnoses. Each girl attended a resource base attached to a mainstream secondary school and joined at least one mainstream class each week. Six girls transitioned to the resource base on entry to the school (age 11), whereas two transferred during subsequent years (ages 12–14). Each girl chose a pseudonym to protect their identity.

Table 1.

Girls’ demographics.

| Pseudonym | Age (years, months) | Ethnicity | Age at diagnosis (years) | Co-existing diagnoses | School | School year | Primary school (ages 4–11) | School year started in RB | Percentage of time in resource base and mainstream | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class RB: M | Social RB: M | |||||||||

| Miranda | 12, 1 | White British | 10 | Sensory processing | A | Year 7 | M | Year 7 | 12:88 | 90:10 |

| Summer | 13, 4 | White British | 9 | None | A | Year 8 | M with 1:1 support | Year 7 | 12:88 | 80:20 |

| Helen | 14, 0 | White British | 12 | Anxiety, ADD (pending) | A | Year 9 | M | Year 9 | 12:88 | 100:0 |

| Holly | 12, 11 | White British | 7 | Anxiety | B | Year 8 | RB attached to M | Year 7 | 5:95 | 75:25 |

| Nia | 14, 1 | White British | 10 | None | B | Year 9 | M | Year 7 | 60:40 | 95:5 |

| Alice | 13, 5 | White British | 9 | ADHD | C | Year 8 | M | Year 7 | 95:5 | 20:80 |

| Ivy | 13, 10 | White British | 8 | Dyslexia | C | Year 9 | M | Year 7 | 60:40 | 80:20 |

| Liana | 15, 2 | White European | 7 | Genetic condition | C | Year 10 | M | Year 8 | 80:20 | 100:0 |

ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder ; ADD ICD-11: Attention Deficit Disorder (World Health Organisation, 2018); RB: resource base, M: mainstream, Social: unstructured lunch and break times; Year 7: 11/12 years, Year 8: 12/13 years, Year 9: 13/14 years, Year 10: 14/15 years; Participant Socioeconomic Status were not recorded; School A, B or C corresponds to which school the girls attended.

Measures of cognitive ability (measured using the two-sub-test version of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition, WASI-II; Wechsler, 2011), social communication needs (measured using the Social Communication Questionnaire, SCQ; Rutter et al., 2003) and friendship quality (measured using the Friendship Qualities Scale, FQS; Bukowski et al., 1994) were collected for each of the girls. These data were not collected with the intention to link them to the qualitative data on camouflaging experiences. Rather, due to the heterogeneity of autism, we collected this background data because we felt it was important to characterise the cognitive and behavioural traits of the girls who participated in the study.

As detailed in Table 2, four girls scored within the average range on the WASI-II (90–109), while four girls scored below average (72–77; indicating that they presented with greater learning needs than their peers). The SCQ (Rutter et al., 2003) scores revealed that only three of the girls obtained scores above the suggested cut-off score of 15 (indicative of possible autism), with five girls scoring below this cut off. Given that all the girls had clinical diagnoses of autism and were currently attending a specialist provision with a primary need of autism, none of the girls were excluded from the sample based on this. The girls rated their friendships on the FQS (Bukowski et al., 1994) across five qualities: companionship, conflict, help, security and closeness. Across all scales, the girls received an average score above 3.00, indicating that they rated the quality of their friendships positively.

Table 2.

Girls’ scores on background measures.

| Name | WASI-II score | SCQ score | FQS score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Companion | Reduced conflict | Help | Security | Closeness | Total | |||

| Miranda | 108 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 22.8 |

| Summer | 101 | 8 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 15.1 |

| Helen | 72 | 10 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 19 |

| Holly | 75 | 15 | 4.3 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 15.8 |

| Nia | 92 | 9 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 15.8 |

| Alice | 77 | 14 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 18.6 |

| Ivy | 103 | 16 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 13.4 |

| Liana | 74 | 8 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 13.5 |

| M | 87.75 | 12.50 | 3.04 | 3.04 | 3.43 | 3.33 | 3.93 | 16.75 |

| SD | 14.89 | 4.41 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.01 | 0.54 | 3.19 |

| Range | 72–108 | 8–20 | 1.3–4.3 | 1.3–4.3 | 2.4–4.8 | 2.0–5.0 | 3.2–5.0 | 13.4–22.8 |

WASI-II: Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second edition (Wechsler, 2011); SCQ: Social Communication Questionnaire Lifetime (Rutter et al., 2003) – Higher scores indicate increased social communication difficulties; FQS: Friendship Qualities Scale (Bukowski et al., 1994) – Higher scores indicate increased positive friendship quality.

A parent for each girl was invited to share their experiences and mothers volunteered in all cases. Six of these were between the ages of 40 and 49 years, while two were between the ages of 30 and 39 years. An educator assigned to each girl also participated: Six were teaching assistants/aides who worked closely with the girls in the resource base and mainstream classes, and one was a senior staff member (and autism lead) who had a strong rapport with one of the girls (note: one educator completed two interviews, for two different girls). All educators had been working in their role for at least 1 year. The duration working with the specific pupil ranged from 4 to 36 (M = 18.38, SD = 12.4) months.

Materials

Semi-structured interviews

Interviews with girls incorporated inclusive approaches to support the girls to engage and communicate their experiences (Curtis et al., 2004; Winstone et al., 2014), and consisted of three parts: (1) interests and friendships, (2) camouflaging and (3) school views and experiences. Initially, the girls answered open-ended questions to build rapport and find out about their interests and friendships (e.g. ‘Can you tell me about yourself?’). Next, the girls completed a visual scaling activity, developed from the self-report Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q; Hull, Mandy, Lai et al., 2019). The CAT-Q was originally developed for autistic adults without an intellectual disability. To ensure the items were accessible to the girls’ different developmental and learning profiles, the wording of the questions was simplified, understanding was supported by visual cartoons and repeated items were removed. Responses were rated on a 4-point scale (never, sometimes, often, always). The girls’ responses were used as prompts when exploring their camouflaging (e.g. ‘You scored this card as always, can you tell me more about the times you hide your interests?’). Finally, the girls were asked to describe their ideal school, including other pupils and staff, activities and physical features (e.g. ‘What would you put in your ideal school?’) (see Supplementary Materials for details of the visual scaling activity and interview schedules).

Educator interviews were developed from literature examining the camouflaging strategies autistic girls use to negotiate their learning and social experiences in school (Cook et al., 2017; Moyse & Porter, 2015). Questions were divided into four sections: (1) girls’ involvement in class-based learning and their camouflaging skills, (2) girls’ relationships and camouflaging, (3) girls’ experiences and camouflaging in different contexts (resource base classes, mainstream classes, home) and (4) positive and negative impacts of camouflaging. Each question was supported by prompts to deepen discussions.

Parent interviews were developed from literature examining camouflaging approaches that autistic girls use to navigate social interaction (Bargiela et al., 2016; Cook et al., 2017; Hull et al., 2017; Moyse & Porter, 2015). Questions were divided into four sections: (1) diagnosis and the impact of autism on their lives, (2) relationships before and since joining the resource base, (3) camouflaging skills, including differences between presentations in different contexts and (4) positive and negative impacts of camouflaging.

Procedure

The study was conducted in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical approval was obtained from the Department of Psychology and Human Development at UCL Institute of Education. All participants (girls, mothers and educators) gave informed written consent (with mothers also providing consent for their daughters to participate). The girls’ data collection materials were piloted with autistic pupils attending a different resource base attached to a mainstream school and their feedback was used to inform and amend the materials. No further community participation was incorporated within the study. Observations of the girls (during resource base classes, mainstream classes and social activities) were completed by one of the authors (J.H.) to build familiarity with each girl and increase understanding of their experiences, but not to generate data for analysis. J.H. then met with each girl individually in the resource base to complete the WASI-II, semi-structured interview and then the FQS. Following this, J.H. interviewed each girl’s educator and then their mother (mothers also completed the SCQ). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, ranging in length from 16 to 42 (M = 31, SD = 10) min for girls, 18 to 44 (M = 30, SD = 10) min for mothers and 17 to 38 (M = 22, SD = 9) min for educators.

Data analysis

The researchers adopted a social constructionist perspective, which was particularly relevant when considering camouflaging: The desire to ‘blend in’ with social expectations is not a stable phenomenon and will be understood differently according to each participant’s experiences and interactions. Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2013, 2019) was used to analyse data on camouflaging experiences, chosen due to being theoretically flexible in approach and its strength in bringing together meaning across the whole data set. The analysis involved recursively proceeding through the stages of (1) data familiarisation, (2) initial code generation, (3) searching for themes, (4) theme review, (5) naming and defining themes and (6) report production. Themes were primarily drawn from inductive (‘bottom-up’) methods, which sought to identify patterns in the collected data without integrating these within pre-existing codes or preconceptions of the researchers. The analyses were led by J.H., in consultation with L.C. and C.C. In terms of positionality, all authors (two of whom are educational psychologists (J.H., C.C.), one an academic researcher (L.C.) view autism from a social model of disability perspective (Oliver, 1986), recognising that autistic young people are disabled by barriers in society that exclude/discriminate them, rather than as a result of within-child ‘impairments’ or ‘deficits’. A hermeneutical approach was used to provide openness and clarity on the researchers’ presuppositions when interpreting the participants’ narratives (Gadamer, 1960/2004). J.H.’s position was also informed by her personal experiences (as a mother of a child diagnosed with autism) and professional experiences (having supported autistic children in school in a range of roles).

J.H. coded the girls’ data first (Steps 1–4), before reviewing this with the other authors. The educators’ and mothers’ data were then analysed using the same process. Saturation was reached within each group, before data were combined across the three groups. Despite the girls, mothers and educators having some differing perspectives around the girls’ ability to camouflage, overlapping themes were found across the whole sample and the analyses were combined. Throughout the process, a note of inconsistencies and tensions was kept and reviewed by the research team, identifying any perspectives or areas which did not align. This resulted in each theme being reviewed and extended, and an additional sub-theme being added to capture parental experiences of diagnosis and early support. The final two steps (5 and 6) were then completed with the entire data set. The decision to combine analysis of multi-informant perspectives in this way has been established within the literature (e.g. Calder et al., 2012).

Results

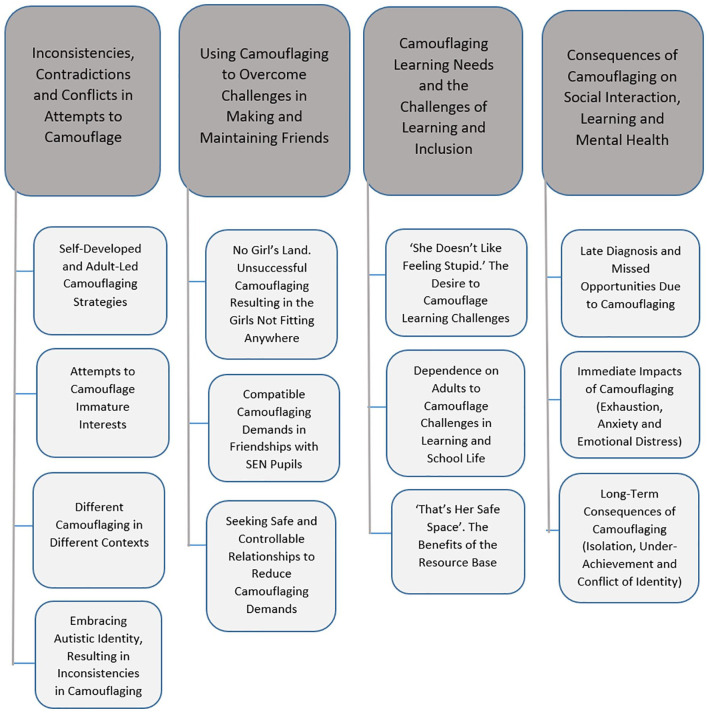

Four themes (incorporating 13 sub-themes) were identified from the qualitative data (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Thematic map.

Theme 1: inconsistencies, contradictions and conflicts in attempts to camouflage

This theme refers to the girls’ attempts to use a range of strategies to camouflage their social difficulties and autistic behaviours in different school contexts, and the inconsistencies, contradictions and conflicts that this revealed.

Sub-theme 1: self-developed and adult-led camouflaging strategies

Most of the girls described self-developed camouflaging strategies aiming to negotiate social interaction and conceal behaviours associated with their autism: ‘I try and hide . . . I might still do it, just make sure people aren’t seeing’ (Ivy). These self-developed strategies were motivated by a desire to avoid bullying or humiliation: ‘I smile and nod, like I know what they’re talking about, but I really don’t . . . I worry they might laugh at me’ (Liana). At times, these strategies involved changing their identity: ‘Sometimes I try to change how I react. I change my entire personality’ (Holly).

Mothers and educators also described these self-developed strategies but noted they were unsophisticated and intermittent, undermined by the girls’ challenges in understanding and generalising aspects of complex social interaction: ‘She is so good at . . . superficial introductions but what she can’t do is develop those friendships further’ (Helen’s parent). They reported how some girls used more complex strategies, like researching people’s interests to underpin conversation, although without understanding that such strategies needed to be dynamic. Alongside self-developed strategies, mothers and educators described facilitating camouflaging through teaching social skills and individual guidance, which the girls reflected on: ‘I try to do eye contacts . . . because I know how to talk to people now’ (Alice). They also reminded the girls not to discuss inappropriate or personal matters. Educators reported attempting to guide the behaviour of all pupils in resource base classes to reduce embarrassment for pupils who were trying to camouflage:

One of the boys . . . he’s making silly noises . . . I’ve had numerous conversations with him . . . about the fact that it makes him look odd . . . when you’ve got somebody . . . who’s trying to blend in with the norm, it doesn’t help. (Summer’s educator)

Sub-theme 2: attempts to camouflage immature interests

The girls spoke of the struggle to camouflage their interests, recognising that their neurotypical peers had progressed: ‘It always seems to lead on to the subject of like boys . . . we’re talking about horses . . . and it leads onto that subject . . . it gets annoying’ (Summer). Mothers and educators described conflict between the girls’ immature interests and their desire to fit in: ‘She loves My Little Pony, but she won’t tell anyone that . . . she’s recognising that’s not necessarily age appropriate . . . but she still likes to play with them at home’ (Holly’s parent). This was exacerbated by their desire to participate in ‘young’ games played by other pupils in the resource base: ‘She becomes conflicted because she wants to join in so she will try to argue reasons that it’s okay . . . with Lego she uses it in the [resource base] because it can be used for therapy’ (Summer’s educator).

Sub-theme 3: different camouflaging in different contexts

Girls, mothers and educators reported that camouflaging varied according to context, with less need to camouflage at home: ‘at home I can be myself’ (Summer). Educators stated that the girls had little need to camouflage in the resource base: ‘In the base she feels very free to be herself . . . she will mask more in mainstream, just to be with her friends’ (Alice’s educator). Although the girls said that they felt more relaxed in the resource base, they reported camouflaging in all school settings: ‘yeah [I camouflage in the resource base] ’cause they still laugh if I, like if I say it wrong’ (Nia).

Sub-theme 4: embracing autistic identity, resulting in inconsistencies in camouflaging

A significant inconsistency was reported between the girls’ desire to fit in and their identity as a diagnosed pupil attending resource base classes. Mothers and educators reported that the girls felt that their diagnosis validated them to embrace certain aspects of their autism: ‘She’s . . . quite proud to be different and . . . tells people information about strengths of autism’ (Summer’s parent). The girls confirmed this and noted that despite their desire to camouflage, they would avoid imitating others: ‘Try to copy what other people wear? No, never in a million years’ (Holly).

Theme 2: using camouflaging to overcome challenges in making and maintaining friends

This theme considers the girls’ use of camouflaging strategies to reduce and conceal their significant challenges in making and maintaining friendships across different classes (in the mainstream or resource base).

Sub-theme 1: no girl’s land—unsuccessful camouflaging resulting in the girls not fitting anywhere

Girls, mothers and educators highlighted the vulnerability of the girls being neither ‘normal’ enough to fit into mainstream classes nor different enough to feel fulfilled by friendships with pupils in resource base classes: ‘She will try to separate herself from [the resource base] and fit with what she thinks is normal’ (Summer’s educator). Despite attempts to blend in, they were unable to maintain the friendships they desired with neurotypical girls: ‘Camouflaging hasn’t helped her to make friends with girls and I think that is her biggest challenge’ (Nia’s parent). Many girls rejected the identity of being the same as other pupils in resource base classes and found the behaviour of these pupils challenging: ‘When it comes to my classmates they’re very, very weird . . . they act weird and they are very loud and annoying . . . My classmates are annoying to my brain’ (Alice). They reported that their ability to camouflage with peers in mainstream classes was undermined by this association: ‘I don’t really like the resource centre students because . . . the students in the [mainstream] class always compare us and I’m so much different to them lot’ (Nia).

Mothers reported that the predominance of boys in resource base classes compromised their daughters’ ability to make friendships with other girls: ‘the lack of female friendships is still a challenge and that’s because she’s the only girl in her class’ (Ivy’s parent). Mothers identified that friendship challenges had increased through adolescence as camouflaging demands became more complex:

We noticed the divergence between friendship at primary . . . to secondary . . . it was like her typically developing peers blossomed . . . And girls’ behaviour becomes very nuanced, doesn’t it? It can be just a look . . . and she can’t read that. (Helen’s parent)

Sub-theme 2: compatible camouflaging demands in friendships with SEN pupils

The girls, mothers and educators spoke of positive mainstream friendships with pupils identified with SEN, which were highly valued: ‘Since she started this school, her friendships are much better . . . She seems to have become part of a group of similar children, they’re in the mainstream, but they seem to be relatively similar’ (Holly’s parent). Mothers and educators attributed the success of these friendships to reduced social interaction demands, resulting in less complexity in camouflaging: ‘Helen is Helen with her peers . . . I think she would be able to look round and probably a number of her friends would be in a similar boat’ (Helen’s parent).

Sub-theme 3: seeking safe and controllable relationships to reduce camouflaging demands

Girls, mothers and educators described how the girls sought simplified social interactions. This enabled them to explore relationships in safe and controllable situations, thus reducing camouflaging demands. Often this involved friendships with peers in different age groups: ‘The only natural thing about Summer’s social behaviour is when she’s with little children, otherwise it’s like she is acting each role’ (Summer’s parent). Desiring older friendships, many girls identified school staff as friends: ‘[in my ideal school] I’d get a Starbucks delivery . . . just for me and Miss, in a room by ourselves and no one’s annoying us’ (Nia). Educators confirmed that many girls desired friendships with the staff: ‘I feel Liana gets on better with adults than she does students’ (Liana’s educator). Some mothers described fantasy friendships as an alternative way for their daughters to explore and control relationships: ‘I do wonder if those (imaginary) friends are because she doesn’t have that many real friends’ (Miranda’s parent).

Theme 3: camouflaging learning needs and the challenges of learning and inclusion

This theme examines the girls’ determination to camouflage their learning needs, especially from their mainstream peers, and considers the interaction between the girls’ camouflaging, learning and inclusion across mainstream and resource base classes.

Sub-theme 1: ‘she doesn’t like feeling stupid’—the desire to camouflage learning challenges

The girls described their desire to conceal their challenges with learning, especially in mainstream classes: ‘I always feel like I’m gonna hide under the table . . . ’cause everyone’s looking at me and if I make a wrong mistake everyone will laugh at me’ (Holly). Mothers and educators also emphasised the girls’ desire to hide their learning challenges: ‘She doesn’t want to fail, others to notice her . . . if she gets something wrong, she takes it as a direct hit . . . just doesn’t like feeling stupid, and classes to her, are an arena for feeling stupid’ (Helen’s educator).

Educators identified strategies that the girls tried to use to camouflage their learning difficulties:

The presentation and underlining, it takes such a long time . . . rather than the content . . . I think that’s her coping mechanism, if she doesn’t understand, I don’t think she likes to admit that she struggles. (Holly’s educator)

Girls, mothers and educators reported that pressure upon the girls to camouflage appeared to intensify as demands for academic achievement increased. Often, the girls became trapped in a negative cycle, where the demands of trying to camouflage their learning needs, and the anxiety associated with this, reduced their ability to learn: ‘If I don’t understand a certain topic, I don’t really want to do it because I . . . don’t want to show I don’t understand’ (Helen).

Sub-theme 2: dependence on adults to camouflage challenges in learning and school life

Girls and educators described their dependence on teaching assistants/aides to facilitate their learning and emotional needs. Educators emphasised the importance of a strong relationship with the girls, which facilitated their role as mediators between mainstream class teachers’ expectations and the girls’ needs. This relationship allowed them to see through the girls’ camouflaging and recognise subtle indications that they were becoming anxious and overwhelmed: ‘It is just little signs . . . the tiny movements’ (Helen’s educator). Although the girls described dependence upon their teaching assistants/aides, many of them noted that this conflicted with their attempts to camouflage because they were seated with resource base pupils and staff, which affected their inclusion with mainstream peers: ‘I’m sat away from everyone’ (Nia).

Sub-theme 3: ‘that’s her safe space’—the benefits of the resource base

Educators, mothers and girls agreed that classes in the resource base were calmer and more supportive learning environments than in the mainstream: ‘I mean, that’s her safe space . . . she’s free to either be happy or stressed . . . she can relax and learn’ (Helen’s educator). The girls felt there was more awareness of their needs in resource base classes: ‘Miss understands everyone’s [autism] and all the staff know what they’re doing and they know exactly how to react . . . in the main lessons they, they sort of understand’ (Holly). Mothers and educators reported that the umbrella of support provided within resource base classes extended beyond supporting direct needs associated with autism, and often, the girls’ learning needs and organisation skills were equally prioritised.

Theme 4: consequences of camouflaging on social interaction, learning and mental health

This theme examines the consequences of camouflaging; detailing the reported (immediate and longer term) costs of camouflaging on social interaction, learning and mental health.

Sub-theme 1: late diagnosis and missed opportunities due to camouflaging

Many mothers described the delay to their daughters’ autism diagnoses, which they attributed to camouflaging: ‘She was a problem right from reception class [ages 4–5 years], but it took all that time to get something done. They just didn’t believe it was autism till too late’ (Summer’s parent). Most girls were not diagnosed until the end of primary school [up to age 11 years] and mothers expressed their frustration at the lost educational and social opportunities. This was felt to affect the girls’ happiness and self-esteem and resulted in many girls being on the edge of school refusal: ‘I feel primary school was a real missed opportunity . . . I want her happy . . . and she was sad, a sad little girl for a really long time’ (Helen’s parent).

Sub-theme 2: immediate impacts of camouflaging (exhaustion, anxiety and emotional distress)

Some educators and mothers spoke of the positive effects of camouflaging, such as enabling the girls to avoid bullying and fit into social interactions. However, most consequences described by girls, mothers and educators were negative. Exhaustion was identified as having the most impact. Girls described camouflaging as ‘really tiring’ (Holly). Mothers and educators expressed the cost of this in detail:

When she gets back to base she can . . . let her shields down, she just seems all those sort of things that go with being exhausted. And really on edge, going to find any reason to have a meltdown, which obviously has a huge impact on her learning. (Alice’s educator)

Mothers and educators described the girls’ uncertainty about their success in camouflaging their social and learning challenges, which resulted in frustration, anger and anxiety: ‘She was very tearful, very anxious and nervous . . . lots of tummy aches . . . lots of anxiety because she didn’t fit in’ (Liana’s parent). These immediate impacts were visible mainly in resource base classes following mainstream interaction. Mothers and girls spoke of similar impacts after school, with girls experiencing exhaustion, anger and conflict: ‘At home, I can sometimes be more angry. Like, if I’m angry at school, most of the time I try and hide it’ (Helen).

Sub-theme 3: long-term consequences of camouflaging (isolation, under-achievement and conflict of identity)

Long-term consequences for both social and learning achievements were primarily described by mothers and educators. They noted that despite the girls’ attempts to camouflage, their challenges with social interaction resulted in low self-esteem and isolation: ‘There was a bit of bullying, not hitting or anything, but they deliberately left her out and she was upset by it. I said to go and make new friends but she wasn’t willing to try again’ (Nia’s parent). Mothers and educators expressed concern that the demands of mainstream classes, combined with camouflaging, resulted in the girls underachieving. They attributed this to exhaustion, avoidance of mainstream classes and preoccupation with camouflaging: ‘If she can get out of those mainstream lessons, by saying she doesn’t feel well, she will do . . . it’s quite a hard environment for her to fit into’ (Liana’s parent). Some mothers expressed concern at the consequences of the conflict between camouflaging and the girls’ developing identity:

You’re not being your proper self . . . she’s got a foot in each camp, because she’s not in enough of the autism bubble to not care . . . So she’s different. She recognizes that, can’t do anything about that . . . and I think it must be that conflict which is really hard. (Helen’s parent)

Discussion

Research indicates that autistic women and girls are particularly vulnerable to camouflaging their autistic characteristics (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019; Hull et al., 2017). Increasingly, these camouflaging strategies are being associated with significant negative impacts, including exhaustion and anxiety, alongside missed opportunities for support and intervention in school (Bargiela et al., 2016; Hull et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2016). In this study, multiple perspectives were elicited regarding camouflaging among adolescent autistic girls educated in specialist resource bases attached to mainstream schools. Results demonstrated that within both mainstream and resource base classes, the girls attempted to use camouflaging strategies to hide both learning challenges and their autistic characteristics. Yet, these attempts were often inconsistent and ineffective. Various consequences of camouflaging were identified, including persistent isolation attributed to the girls not belonging to either the mainstream or resource base contexts. Throughout the analyses, the perspectives of different stakeholders were broadly similar; the only slight differences reflect the different contexts that educators and mothers tended to view the girls’ camouflaging behaviour in (i.e. home or school).

This study was the first to examine whether adolescent autistic girls who attended the intermediate context of a specialist resource base attached to a mainstream school used camouflaging strategies. Adolescence has been established as a stage of social complexity, during which the nuances of social interaction can become overwhelming for autistic girls (Cridland et al., 2014; Gould & Ashton-Smith, 2011; Tierney et al., 2016). These challenges were evident in the current study, in which mothers and educators attributed increased camouflaging behaviours in mainstream classes to increased social expectations. Educators reported that the girls felt little requirement to camouflage in resource base classes, yet most of the girls described using camouflaging strategies across all school contexts. The differences between educators’ perceptions of camouflaging and the girls’ firsthand descriptions may be explained with reference to the double empathy framework (Milton, 2012), which emphasises that differences in perspectives and understanding between autistic and non-autistic individuals may result in a bi-directional breakdown in shared understanding. In line with previous research (Cook et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2016), girls and mothers reported less need to camouflage at home.

Alongside the desire to conceal the social challenges of autism, all girls were motivated to camouflage their learning needs across all school contexts. Several studies have suggested that autistic girls may avoid academic risk-taking to reduce the chance of failure (Ashburner et al., 2010; Gould & Ashton-Smith, 2011) and camouflage their academic uncertainty (Moyse & Porter, 2015). The current study identified a vicious circle, in which the girls’ commitment to concealing their learning challenges resulted in missed learning, teacher unawareness and under-achievement. The recognition that the girls were camouflaging both their autism and learning needs within school, with increased demands in mainstream classes, has important implications for educational professionals supporting autistic girls. These implications include increasing school staff awareness of camouflaging, facilitating a person-centred approach to managing the demands of different school contexts and developing ways to reduce stigma and increase acceptance of difference. Taken together, these initiatives may begin to reduce the requirement for the girls to camouflage (see Supplementary Materials for further details).

An additional key finding from the current study was that the girls used camouflaging strategies inconsistently. Most girls used simple strategies (e.g. appearing busy on their phone), while some girls’ attempts at camouflaging were more complex (e.g. pre-planning scripts). The camouflaging approaches reported in this study broadly reflected those identified in previous literature (Hull et al., 2017, 2019), including assimilation (with the girls being motivated to conceal their behaviour and pretending to understand social norms), masking (with the girls attempting to hide their autistic characteristics) and compensation (with some girls describing more complex strategies such as researching normative social interaction). Despite the girls’ attempts to use this range of camouflaging strategies, mothers and educators noted these were often used ineffectively and inconsistently, without the necessary flexibility or adaptations needed to camouflage effectively within dynamic social contexts. Livingston and Happé (2017) describe the potential of superficial strategies breaking down, particularly when the social environment is challenging.

Inconsistencies were also prevalent in the girls’ interests and their attempts to camouflage these. Although interests followed gender expectations (McFayden et al., 2018), they had not developed at the speed and sophistication of their neurotypical peers. The girls camouflaged their immature interests by revealing different interests in different contexts, but this strategy was undermined by conflicting expectations between mainstream and resource base classes. The discrepancy between gender expectations, interests, and development in adolescent autistic girls has also been described in previous research (Cridland et al., 2014; Tierney et al., 2016), which highlights that increased camouflaging demands, alongside differences in gendered social expectations, undermines autistic girls’ friendships.

Further inconsistencies in the girls’ camouflaging were connected with their autistic identity. Within the resource base, girls felt validated to externalise some ‘acceptable’ autistic characteristics while attempting to camouflage others. In conflict with their desire to blend in, some girls also promoted aspects of their autism identity in mainstream classes. This contrasts with previous research (Cook et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2016) and may be affected by the resource base context, which increased mainstream peers’ awareness of the girls’ autism diagnosis, reducing the purpose of their camouflaging.

Previous research has shown that camouflaging is motivated by internal and external demands (Hull et al., 2017). These motivations were also evident in the current study. In terms of internal factors, all of the girls were motivated to camouflage by their desire for friendship. Despite attempts to modify their behaviour to conform with neurotypical peers, the girls’ educators and mothers described how their friendships were characterised by difficulties and repeated experiences of rejection and isolation. Similar challenges have been described in previous research, which has recognised that autistic girls’ relationships can be affected by friendship insecurity, risk of isolation and challenges managing conflict (Sedgewick et al., 2018, 2019).

The girls’ struggles to identify where they belonged socially were compounded by their determination to remove themselves from peer interactions within resource base classes. These associations reduced the effectiveness of the girls’ attempts to blend in with their mainstream peers and resulted in the girls being socially excluded twice. Specifically, they were separated from their mainstream peers, which reduced their ability to make positive social connections with this group. At the same time, the resource base classes had far more boys, many of whom had significant needs, resulting in the girls having no peer group. The impact of this double exclusion resulted in isolation and an increased desire to camouflage. Some girls resolved this by developing friendships with mainstream pupils identified with SEN, which resulted in compatible social expectations and camouflaging demands. Similar friendship patterns for autistic girls attending mainstream schools suggest that SEN relationships can enable girls to feel accepted, allowing them to reduce camouflaging (Cook et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2016). These findings highlight the important role educational professionals should play in facilitating autistic girls’ sense of belonging and friendships within mainstream classes. Opportunities should be provided to promote mainstream friendships for the girls where desired, through structured and supported interest-led activities with mainstream peers, including those with SEN.

In terms of external factors, mothers and educators provided social skills teaching and encouragement to camouflage. Some educators provided similar guidance to all pupils in resource base classes, irrespective of their desire to blend in. These environmental pressures to camouflage were grounded in the social expectation that autistic people need to adjust their behaviour to facilitate being accepted (Hull et al., 2017). Growing recognition of the need to embrace neurodiversity (rather than trying to encourage autistic people to adhere to neurotypical standards of behaviour) underscores the importance of adjusting the educational environment to enable autistic people to access this successfully, including via peer education. Unfortunately, there continues to be guidance provided by significant adults in school who wish to reduce the negative interactions associated with being viewed as ‘different’ (Bargiela et al., 2016).

Together, these internal and external factors may lead to negative consequences. Girls, mothers and educators described the immense exhaustion that they felt followed camouflaging. This was usually revealed in resource base classes, after the girls left mainstream classes and on arrival home. Alongside exhaustion, the girls were reported to be highly anxious within school. This was compounded by uncertainty regarding the success of their camouflaging and concern that their attempts may fail. Mothers expressed their worries about the impact of camouflaging on their daughter’s identity. They detailed the conflict that the girls faced by not camouflaging successfully enough to build a ‘mainstream’ identity, alongside not fitting within the stereotypical expectations of autism. The impact of this conflict has been described in previous research, which describes a range of mental health difficulties attributed to the pressures of negotiating this tension (Crane et al., 2019).

The negative consequences reportedly associated with camouflaging were present irrespective of the sophistication and success of the girls’ camouflaging. At times, the girls’ attempts to camouflage were misinterpreted, which meant that they missed out on appropriate and targeted support. This was particularly evident in mainstream classes, where the combination of the girls’ attempts to camouflage their social and learning needs, alongside the exhaustion and anxiety associated with this, was felt to have long-term impacts on learning. These challenges were compounded by the girls reporting that their mainstream teachers appeared unaware of their struggles. Similar concerns regarding professional awareness are evident in existing literature (Bargiela et al., 2016; Hull et al., 2017), contributing to late diagnosis and insufficient support. These are fuelled by contradictions to the established stereotypes of autism, alongside gendered expectations of behaviour (Bargiela et al., 2016; Hull et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2016). The impact of camouflaging on the girls’ learning, social interaction and mental health emphasises the need for educational professionals to explore camouflaging demands and develop adjustments to learning and social expectations to facilitate recovery, alongside carefully planned support (see Supplementary Materials for further details).

It is important to note the limitations of the current study. First, in line with similar qualitative research (Cook et al., 2017; Sproston et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2016), this study included a relatively small sample. This allowed for in-depth exploration of the girls’ camouflaging but, given the heterogeneity of autism, generalisability should be considered. Second, to increase homogeneity, this study focused exclusively on adolescent autistic girls. However, the inclusion of autistic boys as well as neurotypical children would have enabled greater clarity regarding whether the experiences reported were specific to autistic girls. Third, there are challenges inherent with eliciting the perspectives of autistic children, particularly where the methodology depends on social communication (Beresford et al., 2004). The inclusive methods used in this study did, however, go some way to addressing this. Finally, the nature of camouflaging brings uncertainty regarding whether the girls were camouflaging during their interviews and, if so, the impact this had. Triangulating the girls’ responses with those of their mothers and educators provided some useful insight into this.

In conclusion, this study highlights how autistic girls’ camouflaging may differ across different school contexts, but inconsistently. This often meant that they did not experience the benefits of successful camouflaging but did experience the associated costs. There is limited insight into how camouflaging strategies develop, especially for autistic children who attend specialist educational provisions. Further research should examine this, for both autistic boys and girls, enabling earlier identification and appropriate support prior to the challenging transition into adolescence. This research also has implications for intervention. Camouflaging is underpinned by the interaction between the autistic person’s presentation and the demands of the environment. Previous research aiming to reduce this conflict has primarily focused on the autistic individual changing their behaviour to fit in (Mandy, 2019; Wong et al., 2015), yet this comes with significant consequences. Future research should examine how to develop a culture within schools (and wider society) that celebrates diversity and explicitly promotes acceptance of difference. This will reduce the requirement for autistic girls to camouflage and the negative consequences associated with this. An important aspect of this will involve developing professional awareness to identify and support autistic girls’ needs, even when these are camouflaged.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-aut-10.1177_13623613211012819 for “Camouflaging” by adolescent autistic girls who attend both mainstream and specialist resource classes: Perspectives of girls, their mothers and their educators by Joanne Halsall, Chris Clarke and Laura Crane in Autism

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-aut-10.1177_13623613211012819 for “Camouflaging” by adolescent autistic girls who attend both mainstream and specialist resource classes: Perspectives of girls, their mothers and their educators by Joanne Halsall, Chris Clarke and Laura Crane in Autism

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-aut-10.1177_13623613211012819 for “Camouflaging” by adolescent autistic girls who attend both mainstream and specialist resource classes: Perspectives of girls, their mothers and their educators by Joanne Halsall, Chris Clarke and Laura Crane in Autism

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Joanne Halsall  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2875-1781

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2875-1781

Laura Crane  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4161-3490

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4161-3490

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Ashburner J., Ziviani J., Rodger S. (2010). Surviving in the mainstream: Capacity of children with autism spectrum disorders to perform academically and regulate their emotions and behaviour at school. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(1), 18–27. 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bargiela S., Steward R., Mandy W. (2016). The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. 10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beresford B., Tozer R., Rabiee P., Sloper P. (2004). Developing an approach to involving children with autistic spectrum disorder in a social care research project. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32, 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore S. (2018). Inventing ourselves: The secret life of the teenage brain. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Bond C., Hebron J. (2016). Developing mainstream resource provision for pupils with autism spectrum disorder: Staff perceptions and satisfaction. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31(2), 250–263. 10.1080/08856257.2016.1141543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski W., Hoza B., Boivin M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11(3), 471–484. 10.1177/0265407594113011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cage E., Troxell-Whitman Z. (2019). Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 1899–1911. 10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder L., Hill V., Pellicano E. (2012). ‘Sometimes I want to play by myself’: Understanding what friendship means to children with autism in mainstream primary schools. Autism, 17(3), 296–316. 10.1177/1362361312467866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A., Ogden J., Winstone N. (2017). Friendship motivations, challenges and the role of masking for girls with autism in contrasting school settings. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(3), 302–315. 10.1080/08856257.2017.1312797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L., Adams F., Harper G., Welch J., Pellicano E. (2019). ‘Something needs to change’: Mental health experiences of young autistic adults in England. Autism, 23(2), 477–493. 10.1177/1362361318757048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cridland E., Jones S., Caputi P., Magee C. (2014). Being a girl in a boys’ world: Investigating the experiences of girls with autism spectrum disorders during adolescence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(6), 1261–1274. 10.1007/s10803-013-1985-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croydon A., Remington A., Kenny L., Pellicano E. (2019). ‘This is what we’ve always wanted’: Perspectives on young autistic people’s transition from special school to mainstream satellite classes. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 4, 1–16. 10.1177/239694151988647533912683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis K., Roberts H., Copperman J., Downie A., Liabo K. (2004). ‘How come I don’t get asked no questions?’ Researching ‘hard to reach’ children and teenagers. Child & Family Social Work, 9(2), 167–175. 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2004.00304.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M., Harwood R., Kasari C. (2017). The art of camouflage: Gender differences in the social behaviours of girls and boys with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(6), 678–689. 10.1177/1362361316671845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworzynski A., Ronald A., Bolton P., Happé F. (2012). How different are girls and boys above and below the diagnostic threshold for autism spectrum disorders? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(8), 788–797. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer H. (2004). Truth and method (Weinsheimer J., Marshall D. G. Trans.). Continuum. (Original work published 1960) [Google Scholar]

- Gould J., Ashton-Smith J. (2011). Missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis? Girls and women on the autism spectrum. Good Autism Practice, 12(1), 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hebron J., Bond C. (2017). Developing mainstream resource provision for pupils with autism spectrum disorder: Parent and pupil perceptions. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(4), 556–571. 10.1080/08856257.2017.1297569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller R., Young R., Weber N. (2014). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder based on DSM-5 criteria: Evidence from clinician and teacher reporting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1381–1393. 10.1007/s10802-014-9881-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull L., Lai M.-C., Baron-Cohen S., Allison C., Smith P., Petrides K., Mandy W. (2019). Gender differences in self-reported camouflaging in autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism, 24(2), 352–363. 10.1177/1362361319864804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull L., Mandy W., Lai M.-C., Baron-Cohen S., Allison C., Smith P., Petrides K. (2019). Development and validation of the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(3), 819–833. 10.1007/s10803-018-3792-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull L., Petrides K., Allison C., Smith P., Baron-Cohen S., Lai M.-C., Mandy W. (2017). ‘Putting on my best normal’: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2519–2534. 10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaat A., Shui A., Ghods S., Farmer C., Esler A., Thurm A., Georgiades S., Kanne S., Lord C., Kim Y., Bishop S. (2020). Sex differences in scores on standardized measures of autism symptoms: A multisite integrative data analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(1), 97–106. 10.1111/jcpp.13242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp S., Gillberg C. (2011). The Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ)–Revised extended version (ASSQ-REV): An instrument for better capturing the autism phenotype in girls? A preliminary study involving 191 clinical cases and community controls. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(6), 2875–2888. 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.-C., Lombardo M., Auyeung B., Chakrabarti B., Baron-Cohen S. (2015). Sex/gender differences and autism: Setting the scene for future research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 11–24. 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.-C., Lombardo M., Ruigrok A., Chakrabarti B., Auyeung B., Szatmari P., Happé F., Baron-Cohen S.& MRC AIMS Consortium. (2017). Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism, 21(6), 690–702. 10.1177/1362361316671012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leedham A., Thompson A., Smith R., Freeth M. (2020). ‘I was exhausted trying to figure it out’: The experiences of females receiving an autism diagnosis in middle to late adulthood. Autism, 24(1), 135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston L., Happé F. (2017). Conceptualising compensation in neurodevelopmental disorders: Reflections from autism spectrum disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 729–742. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandy W. (2019). Social camouflaging in autism: Is it time to lose the mask? Autism, 23(8), 1879–1881. 10.1177/1362361319878559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFayden T., Albright J., Muskett A., Scarpa A. (2018). The sex discrepancy in an ASD diagnosis: An in depth look at restricted interests and repetitive behaviours. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 1693–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton D. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem’. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. 10.1080/09687599.2012.710008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moyse R., Porter J. (2015). The experience of the hidden curriculum for autistic girls at mainstream primary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(2), 187–201. 10.1080/08856257.2014.986915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neal S., Frederickson N. (2016). ASD transition to mainstream secondary: A positive experience? Educational Psychology in Practice, 32(4), 355–373. 10.1080/02667363.2016.1193478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M. (1986). Social policy and disability: Some theoretical issues. Disability, Handicap & Society, 1(1), 5–17. 10.1080/02674648666780021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M., Le Couteur A., Lord C. (2003). Autism diagnostic interview–Revised. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgewick F., Hill V., Pellicano E. (2018). Parent perspectives on autistic girls’ friendships and futures. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments 3, 1–12. 10.1177/2396941518794497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgewick F., Hill V., Pellicano E. (2019). ‘It’s different for girls’: Gender differences in the friendships and conflict of autistic and neurotypical adolescents. Autism, 23(5), 1119–1132. 10.1177/1362361318794930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sproston K., Sedgewick F., Crane L. (2017). Autistic girls and school exclusion: Perspectives of students and their parents. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 2, 1–14. 10.1177/2396941517706172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney S., Burns J., Kilbey E. (2016). Looking behind the mask: Social coping strategies of girls on the autistic spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 73–83. 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin H., Staunton S., Mandy W., Skuse D., Hellriegel J., Baykaner O., Anderson S., Murin M. (2012). A qualitative examination of parental experience of the transition to mainstream secondary school for children with autism spectrum disorder. Educational & Child Psychology, 29(1), 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (2011). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition (WASI-II). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Wild S. (2019). The specialist secondary experience. In Hebron J., Bond C. (Eds.), Education and girls on the autism spectrum (pp. 137–155). Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Winstone N., Huntington C., Goldsack L., Kyrou E., Millward L. (2014). Eliciting rich dialogue through the use of activity-oriented interviews: Exploring self-identity in autistic young people. Childhood, 21(2), 190–206. 10.1177/0907568213491771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C., Odom S., Hume K., Cox A., Fettig A., Kucharczyk S., Schultz T. (2015). Evidence based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 1951–1966. 10.1007/s10803-014-2351-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th revision). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-aut-10.1177_13623613211012819 for “Camouflaging” by adolescent autistic girls who attend both mainstream and specialist resource classes: Perspectives of girls, their mothers and their educators by Joanne Halsall, Chris Clarke and Laura Crane in Autism

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-aut-10.1177_13623613211012819 for “Camouflaging” by adolescent autistic girls who attend both mainstream and specialist resource classes: Perspectives of girls, their mothers and their educators by Joanne Halsall, Chris Clarke and Laura Crane in Autism

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-aut-10.1177_13623613211012819 for “Camouflaging” by adolescent autistic girls who attend both mainstream and specialist resource classes: Perspectives of girls, their mothers and their educators by Joanne Halsall, Chris Clarke and Laura Crane in Autism