Summary

Background

Mucormycosis (MM) is a deadly opportunistic fungal infection and a large surge in COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) is occurring in India.

Aim

Our aim was to delineate the clinico-epidemiological profile and identify risk factors of CAM patients presenting to the Emergency Department (ED).

Design

This was a retrospective, single-centre, observational study.

Methods

We included patients who presented with clinical features or diagnosed MM and who were previously treated for COVID-19 in last 3 months of presentation (recent COVID-19) or currently being treated for COVID-19 (active COVID-19). Information regarding clinical features of CAM, possible risk factors, examination findings, diagnostic workup including imaging and treatment details were collected.

Results

Seventy CAM patients (median age: 44.5 years, 60% males) with active (75.7%) or recent COVID-19 (24.3%) who presented to the ED in between 6 May 2021 and 1 June 2021, were included. A median duration of 20 days (interquartile range: 13.5–25) was present between the onset of COVID-19 symptoms and the onset of CAM symptoms. Ninety-three percent patients had at least one risk factor. Most common risk factors were diabetes mellitus (70%) and steroid use for COVID-19 disease (70%). After clinical, microbiological and radiological workup, final diagnosis of rhino-orbital CAM was made in most patients (68.6%). Systemic antifungals were started in the ED and urgent surgical debridement was planned.

Conclusion

COVID-19 infection along with its medical management have increased patient susceptibility to MM.

Introduction

Mucormycosis (MM) are syndromes in humans caused by the mucorale group of fungi. These fungi are ubiquitous and present in any environment including hospitals. Inhalation of fungal spores is harmless in immunocompetent individuals but can cause life-threatening disease in those who are immunocompromised.1 The immune system is weak in those with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, prolonged intake of steroids or immunosuppressant medications, malignancies and other debilitating conditions like chronic liver disease and chronic malnutrition state.2 It is notable that these conditions can also indicate risk of severe COVID-19 infection.3

COVID-19 pandemic left the world reeling over the past year. The second wave has been particularly devastating in India. During the months of April and early May 2021, millions were affected and thousands were seeking hospital care.4 Unprecedented numbers needed oxygen therapy and admission putting tremendous pressure on health infrastructure.5 Overlapping with the rise in COVID-19 cases, there was a surge of rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis in those with active or recent COVID-19. MM has a high mortality even with the best of treatment.6 Thus, we designed a retrospective observational study in our department with an objective to document the clinical features, radiological extent and possible risk factors which might be contributing to this illness in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

This was a retrospective, single-centre, observational study following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines and the recommendations by Kaji et al.7 The study was conducted in the Emergency Department (ED), at a tertiary care teaching institute of India. Between 1 April and 1 June 2021, our ED catered to 1647 COVID-19 confirmed admission requiring patients. We observed a surge in MM cases in the later half, i.e. 6 May 2021 to 1 June 2021. We planned to conduct this study to delineate the clinico-epidemiological profile of MM in active or recent COVID-19 patients. Active COVID-19 cases were defined as patients who were laboratory confirmed for SARS-CoV-2 in the ED (by rapid antigen or nucleic acid amplification test). Recent COVID-19 cases were defined as patients who had suffered from COVID-19 in the past 3 months of presentation, but currently SARS-CoV-2 negative in the ED. The time limit of 3 months was taken according to commonly accepted definition of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome.8 COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) was defined as patients with MM along with acute or recent COVID-19 illness. The ethical approval was obtained from the Institute Ethics Committee before the commencement of the study (IEC—366/04 June 2021). The ED patient data repository was screened for patient files with diagnoses MM, fungal sinusitis and COVID-19. Out of the 2007 patient files screened, we found 99 patients of suspected CAM. We included 70 patients who had confirmed MM with previously treated or concurrent COVID-19. Patients without concurrent or recent COVID-19 infection, brought dead and undiagnosed fungal infections were excluded from this study.

Data collection

A detailed data collection sheet was formulated using Delphi method (Supplementary Appendix). Information were collected from the hospital records with an emphasis on the demographic profile, date of arrival, date of onset of CAM symptoms and COVID-19 symptoms, clinical features of CAM, clinical features of current COVID-19, detailed comorbidities and risk factors of CAM, steroid usage details for COVID-19, COVID-19 treatment received prior to CAM symptoms, arrival vitals, diagnostic evaluations in ED (radiological and microbiological), medical treatment given in ED and final disposition with surgical plan. Details of the recent COVID-19 presentation, severity and its treatment (e.g. steroid use, oxygen supplementation) were retrieved from the available documents.

Statistical analysis

Counts and percentages were used to summarize categorical data. Mean and standard deviation were used to summarize normally distributed data, whereas median, range and interquartile range (IQR) were used to summarize non-normal continuous data. Normality of data was tested by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. As this was a descriptive study, no analytical tests were applied on any subgroups. All the analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Results

Demographic profile

A total of 70 diagnosed CAM were included for the analysis (Table 1). These patients presented to our ED in between 6 May 2021 and 1 June 2021. Fifty-three out of 70 patients (75.7%) were active COVID-19, whereas 17 patients (24.3%) were with recent COVID-19 infection (COVID-19 negative during ED presentation). Among the active COVID-19 cases, 7 patients (10%) presented primarily with CAM symptoms, but incidentally detected to have COVID-19, i.e. they were asymptomatic for COVID-19. The median age of the included patients was 44.5 years, with an IQR of 38–55.5 years, with 60% (n = 42) males. Overall, a lag period was observed between the onset of COVID-19 symptoms and the onset of CAM symptoms, with median duration being 20 days (IQR: 13.5–25).

Table 1.

Demographic profile and risk factors

| Characteristics | Characteristics | Total, n = 70 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Median years (IQR) | 44.5 (38–55.5) |

| Gender | Male | 42 (60) |

| Female | 28 (40) | |

| Duration between COVID-19 onset and mucormycosis onset | Median days (IQR) (n = 63) | 20 (13.5–25) |

| COVID-19 status on arrival | Positive at presentation | 53 (75.7) |

| Post-COVID, negative | 17 (24.3) | |

| Comorbid illness | Diabetes | 49 (70) |

| On oral antidiabetic agents | 33 | |

| On insulin | 9 | |

| Recently diagnosed | 5 | |

| Hypertension | 17 (24.3) | |

| Coronary artery diseases | 4 (5.7) | |

| Organ transplant | 2 (2.9) | |

| Chronic kidney diseases | 6 (8.6) | |

| Long term immunosuppressive therapy | Prior steroid use | 3 (4.3) |

| Any other immunosuppressant | 1 (1.4) | |

| Steroid use in the recent COVID-19 | Received systemic steroids | 49 (70) |

| Route of systemic steroids | Intravenous | 27 (38.6) |

| Oral | 22 (31.4) | |

| Type of steroids | Methylprednisolone | 15 (21.4) |

| Dexamethasone | 14 (20) | |

| Prednisolone | 7 (10) | |

| Hydrocortisone | 1 (1.4) | |

| Budesonide | 13 (18.8) | |

| Duration of steroids used | Median days (IQR) (n = 50) | 7.5 (7–10.5) |

| Complication of steroid use | Hyperglycaemia during steroid use which required in-hospital insulin | 33 |

| Inhalational steroid use | Inhalational | 13 (18.8) |

IQR, interquartile range.

Risk factors for MM in COVID-19 patients

Only 5 out of 70 patients (7.1%) had no comorbidities, immunosuppressant use (including steroids) or recent blood glucose elevation. Majority of patients had underlying diabetes mellitus (n = 49, 70%), of which five patients were recently diagnosed during their COVID-19 illness. Nine patients (12.8%) had concomitant diabetic ketoacidosis. Following diabetes, the second most common comorbidity was hypertension (24.3%). Other comorbidities were present in <10% of population. Table 1 depicts the detailed comorbidities of the included patients.

An important risk factor for CAM was the indiscriminate use of steroids for COVID-19. A total of 49 patients (70%) had received steroids for COVID-19 disease prior to arrival to the ED with CAM symptoms. Eleven patients (15.7%) received both inhalational and systemic steroids. Systemic steroids were prescribed for a median duration of 7.5 days (IQR: 7–10.5) in these patients. Unfortunately, 57% patients receiving steroids (28 out of 49) were of mild COVID-19. Details about the steroid use are presented in Table 1. A notable complication of systemic steroids, i.e. hyperglycaemia requiring insulin therapy, was observed 67.3% of patients receiving systemic steroids (33 out of 49). Twenty-seven patients (38.6%) of this cohort also received antibiotics (azithromycin, doxycycline, amoxycillin, piperacillin-tazobactam) prior to ED arrival with CAM symptoms.

Signs and symptoms of MM

Details of the signs and symptoms of CAM are presented in Table 2 (Figure 1). Most common symptom reported in CAM was related to the eye and its adnexal tissues. Nearly 80% patients had eye pain, swollen eyes and significant lid oedema on examination. Other ophthalmic symptoms were diminution of vision, proptosis, ptosis and double vision. Sino-nasal symptoms like nasal stuffiness, nasal discharge and epistaxis were present in 38.6%, 25.7% and 18.6% of patients, respectively. On examination of nasal cavity, crusting and ulceration were present in 24.3% patients. Another common symptom was facial pain, which was the presenting complaint in 34.3% patients. Nearly 10% of patients presented with hemiplegia.

Table 2.

Presenting symptoms and clinical examination findings in mucormycosis patients

| Symptoms | Total, n = 70 (%) | Signs | Total, n = 70 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eyes and adnexa | Eye pain | 57 (81.4) | Lid oedema | 52 (74.3) |

| Swollen eyes | 56 (80) | Visual acuity | 29 (41.4) | |

| Diminution of vision | 26 (37.1) | Proptosis | 28 (40) | |

| Protrusion of eyeball | 24 (34.3) | Chemosis | 24 (34.3) | |

| Ptosis | 14 (20) | Ptosis | 22 (31.4) | |

| Double vision | 1 (1.4) | Ophthalmoplegia | 21 (30) | |

| Nasal cavity | Nasal stuffiness | 27 (38.6) | Crusting and ulceration | 17 (24.3) |

| Nasal discharge | 18 (25.7) | Discharge | 7 (10) | |

| Epistaxis | 13 (18.6) | Active epistaxis | 6 (8.8) | |

| Face | Facial pain | 24 (34.3) | Ulceration | 3 (4.3) |

| Headache | 20 (29) | |||

| Facial ulcers | 3 (4.3) | |||

| Neurological problems | One sided weakness | 8 (11.4) | Hemiplegia | 8 (11.4) |

| Altered sensorium | 5 (7) | Facial palsy | 3 (2.9) | |

| Facial deviation | 2 (2.9) | Altered sensorium | 5 (7) | |

| Decreased facial sensation | 2 (2.8) | Decreased facial sensation | 2 (2.8) | |

| Oral cavity | Oral ulcers | 4 (5.7) | Discoloration | 7 (10) |

| Crusting and ulceration | 5 (7.1) |

Figure 1.

(A–E) Signs and symptoms of mucormycosis. (A) Black eschar lesion over face. (B) Periorbital oedema along with facial palsy. (C) Palatine ulcer with white base over right posterior region. (D) Congestion and small ulcer in right nares. (E) Chemosis and proptosis of right eye and restriction of eye movement on lateral gaze (left eye normal movement).

Diagnosis of MM in the ED

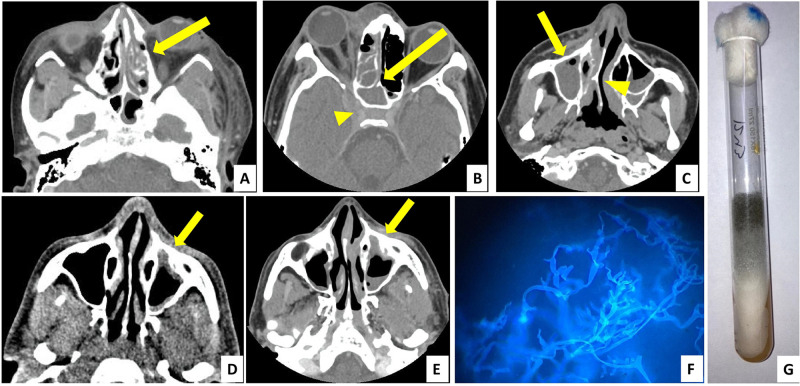

Sixteen out of 70 patients (22.9%) presented to our ED with unstable vital signs and triaged as ‘Red’ category (highest priority) as per institution protocol. Details of the presenting vitals and the point-of-care laboratory values are described in Table 3. The value of C-reactive protein was available for only 10 patients, all of them had values higher than 10 mg/l, indicating severe inflammation due to COVID-19. For definitive diagnosis of CAM, microbiological samples were taken from the active lesions (with or without nasal endoscopy). Potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount with calcofluor stain was positive for aseptate hyphae in 56 patients (80%). For 32 patients, fungal culture was sent, which turned out to be positive in 28 patients (87.5%). Radiological diagnostic modalities included contrast-enhanced computed tomography of brain, orbit and paranasal sinuses in the ED. Most common radiological diagnosis was rhinosinusitis, followed by orbital extension and intracranial invasion. Six patients (8.6%) had cerebral infarct and two patients (2.6%) had intracranial bleed. After clinical, microbiological and radiological workups, final diagnosis was made (Figure 2). Rhino-orbital CAM was the most common variety (n = 48, 68.6%), followed by rhino-orbito-cerebral CAM (n = 17, 24.3%).

Table 3.

Presenting vitals, lab parameters and diagnosis of mucormycosis in the study population

| ED parameters | N (%) or median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| Vitals at presentation | Heart rate (bpm) | 98 (81–110) |

| Respiratory rate (per min) | 20 (18–22) | |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 98 (96–98) | |

| Lab values | Random blood sugar at arrival (mg/dl) | 235 (186–300) |

| Total leucocyte count (1000 s per mm3) | 12.8 (8.8–16.1) | |

| Platelets (lakhs per mm3) | 2.46 (1.68–3.10) | |

| D—dimer | 311 (92–537) | |

| Ferritin | 898 (346–1580) | |

| C-reactive protein | 34 (26–64) | |

| Microbiological diagnosis | KOH-calcofluor positive | 56 (80) |

| Culture positive (out of 32) | 28 out of 32 (87.5) | |

| Radiological diagnosis | Rhinosinusitis | 55 (78.6) |

| Orbital extension | 31 (44.3) | |

| Intracranial extension | 12 (17.1) | |

| Brain infarct | 6 (8.6) | |

| Intracranial bleed | 2 (2.9) | |

| Final diagnosis | Rhino-orbital CAM | 48 (68.6) |

| Rhino-orbito-cerebral CAM | 17 (24.3) | |

| Treatment started in the ED | Liposomal amphotericin—B | 68 (97.1) |

| Posaconazole | 2 (2.9) |

bpm, beats per minute; CAM, COVID-19-associated mucormycosis; ED, Emergency Department; IQR, interquartile range; KOH, potassium hydroxide mount for fungal hyphae detection.

Figure 2.

Diagnosis of mucormycosis—radiology (A–E axial section, contrast-enhanced computed tomography images) and microbiology (F and G). (A) Left ethmoidal sinusitis with bony erosion (yellow arrow). (B) Right ethmoidal and sphenoid sinusitis (yellow arrow) with involvement of orbit and orbital apex, extension into cavernous sinus (yellow arrowhead). (C) Right maxillary sinusitis (yellow arrow) with deviated nasal septum (yellow arrowhead). (D) Left maxillary sinus showing thickened mucoperiosteal lining (yellow arrow). (E) Same patient from (D) showed increase in thickening and involvement of maxillary sinus after 1 week (yellow arrow). (F) Mucorales with aseptate hyphae seen on potassium hydroxide mount with calcofluor white stain. (G) Mucorales growth as greyish white colonies on Sabouraud dextrose agar medium.

Management of MM in the ED

Along with the stabilization of haemodynamic parameters, all the CAM cases were managed with initiation of systemic antifungals as soon as possible. Intravenous liposomal amphotericin—B (LAMB) with an initial dose of 5 mg/kg/day was initiated in majority of the cases (n = 68, 97.1%). For patients with intracranial extension, high dose of LAMB, i.e. 10 mg/kg was initiated at the earliest. Oral posaconazole (300 mg twice a day on Day 1 followed by once daily) was initiated in two cases (2.9%). Control of underlying comorbid illness including insulin therapy for hyperglycaemia was initiated for all. Urgent otorhinolaryngology, ophthalmology and neurosurgery consultations were taken for shared decision on the surgical debridement pathway.

Discussion

We conducted a single-centre, retrospective study of 70 patients with CAM who presented to the ED in the setting of acute or recent COVID-19. To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the largest ED-based case series on deadly combinations of MM and COVID-19. As the number of CAM cases were increasing in India during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic, we have tried to delineate the clinico-epidemiological profile of these patients.

Majority of the patients in our study were middle-aged (age: 38–55 years), of which nearly two-thirds were male. This demographic profile was similar to the population of 82 MM patients studied by Chander et al.,9 of which two-third were male and aged between the ages 31–60 years. It has been hypothesized that the effect of oestrogen might be protective in systemic fungal infection, which could have led to lower incidence in females.10

Many experts believe that the combination of high dose steroids and uncontrolled diabetes has led to this epidemic of MM in COVID-19 patients.11–13 In pre-COVID era, Prakash and Chakrabarti14 found diabetes mellitus as a predisposing factor in 17–88% cases globally and in India it was a risk factor in over 50% cases. In the setting of COVID-19, case series by Sharma et al.15 described diabetes as a risk factor in 90% cases of which 52% had uncontrolled disease. A systematic review of 101 cases of MM in COVID-19 by Singh et al.12 noted that more than 80% cases had either pre-existing or new onset hyperglycaemia as a risk factor. Our study has reflected their findings in that 70% of included patients were diabetic.

Prolonged use of corticosteroids increasing risk of MM has been reported in patients.16 Ribes et al.17 described that acute or chronic use of steroids in such patients predisposed them to fungal infection. Steroid use during the pandemic has been supported by the Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy trial, only in those receiving supplemental oxygen therapy and has been endorsed by major international guidelines.18 Subsequently the WHO guidelines recommended against the use of it in non-oxygen requiring patients.19 In India, there were many reports suggesting indiscriminate use of steroids even in mild COVID-19 patients.20 The underlying reasons included non-evidence-based clinical practice, availability of over the counter steroids, shortage of hospital beds, social media, homemade tutorials from unverified sources and inadequate monitoring of the patients taking steroids.21 The improper use of corticosteroids has been identified as an independent risk factor for CAM by the MucoCovi network. In their retrospective analysis of 287 Indian CAM patients during the first wave, they found 32% with COVID-19 as the only underlying disease among which 78% had received steroid therapy.11 Our study had 62 patients who received steroid therapy, 49 patients were on systemic steroids as part of COVID-19 management. Among this group, 57% had non-hypoxic disease and steroids were not indicated as per guidelines. Other comorbid conditions identified include hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, organ transplant recipients and immunosuppression.

Airway epithelial damage and immune dysfunctions are known complications of COVID-19, which may provide an opportunity for fungus to invade lung tissues.22,23 Additional risk factors were hypothesized for a resource-limited developing nation that deserve attention. In this pandemic, acute shortage of oxygen and hospital beds24 led to unhygienic delivery of oxygen including use of industrial oxygen, prolonged use of humidifiers without cleaning and unmonitored use of oxygen delivery devices like nasal cannula (may lead to micro-injuries). This might have added fuel to this fire of CAM surge.25 Some experts believed that wearing face masks over a long time without washing them26 and multivitamins supplementation including zinc and iron might have some role in CAM pathogenesis, though extensive research is needed in this aspect.27 Micro-trauma due to multiple swab tests for diagnosis of COVID-19, steam inhalation and burn injuries may have had a role in this substantial rise of CAM.28

Patterns of MM in patients can differ based on their risk factors, e.g. sinus involvement is common among diabetics. It is noteworthy that in the ED setting, early features of MM may be missed if not evaluated with a high level of suspicion. The presentation may be overlapping with common sinusitis. Presence of associated facial erythema, perinasal swelling, nasal ulcers or eschar should serve as early pointers.29 Palatal necrosis is a hallmark sign which may be seen in 38% patients.30 The red flag signs to look for are cranial nerve palsy, diplopia, periorbital swelling, proptosis, orbital apex syndrome, sinus pain and palatine ulcer.31 Cutaneous involvement was reported in half the patients with no underlying disease.10 In the background of COVID-19, Satish et al.13 reported that 48% patients in their case series had rhino-orbital disease followed by rhino-orbito-cerebral form. Our study too had most common features related to rhino-orbital CAM (69%) followed by rhino-orbito-cerebral CAM (24%). Mishra et al.32 in their case series of rhino-orbito-cerebral MM in COVID-19 reported sinusitis in 100% subjects. MM with Central Nervous System involvement may present with signs and symptoms of acute ischaemic stroke to ED.33 Careful elicitation of prior history of symptoms of MM and meticulous ophthalmic examination to identify co-existing signs with secondary stroke (due to internal carotid artery involvement) becomes crucial to prevent treading the wrong treatment pathway in ED. Microbiological diagnosis was confirmed by KOH-calcofluor mount showing aseptate hyphae and extent was assessed with contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans as per guidelines.34 All patients in our study were started on systemic antifungals and majority received LAMB. Our study showed an overall 14-day mortality of 23%, whereas in the systematic review of 101 CAM patients, the overall mortality was 30.7% (although time-specific mortality was not available).12

Identifying potential risk factors of CAM, its varied presentation, appropriate triaging in ED, assessment of vision, pupil, ocular motility and sinus tenderness as a part of routine physical evaluation in ED are needed in the current situation.23 The overall prognosis of MM is poor and the outcome may drastically change based on the initial treatment trajectory. Sending appropriate investigations, early administration of systemic antifungals, avoiding unnecessary antibiotics and systemic steroids, and prompting for early multidisciplinary surgical debridement including performing lateral canthotomy in ED are the learning points for an emergency physician.35 It is also imperative for the ED physician to exercise caution during the management of acute COVID-19. This includes strict control of hyperglycaemia, titration of oxygen therapy only as per patient need and proper cleaning and maintenance of oxygen delivery devices within hospital settings.

Limitations

One of the limitations of our study is that it was conducted in a single centre. As a result of insufficient data, we were unable to demonstrate whether oxygen from non-healthcare sources and multivitamin supplementation were risk factors for CAM. Patient data up to recovery was not included in our study and this limits our understanding of whether COVID-19 has an impact on MM resolution.

Conclusion

The surge in MM after the peak of the second wave of COVID-19 in India highlights several issues in the healthcare system. Novel illness and the limited evidence in COVID-19 treatment fuelled the crisis. Uncontrolled diabetes and unchecked steroid use were major risk factors for the development of CAM. Many patients in our study had received steroids for mild COVID-19 though not recommended. Other factors like unhygienic oxygen therapy, indiscriminate antibiotic use and COVID-19 itself may have contributed to the CAM crisis. A large-scale multi-centric prospective study would help gain useful data on this deadly disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr Ajith Antony for his support with the radiological images.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at QJMED online.

Conflict of interest. No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Farmakiotis D, Kontoyiannis DP.. Mucormycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2016; 30:143–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNulty JS.Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: predisposing factors. Laryngoscope 1982; 92(10 Pt1):1140–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Underlying Medical Conditions Associated with High Risk for Severe COVID-19: Information for Healthcare Providers. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html (2 July 2021, date last accessed).

- 4.Ranjan R, Sharma A, Verma MK.. Characterization of the second wave of COVID-19 in India. medRxiv 2021; 1:1–10, doi: 10.1101/2021.04.17.21255665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancet E.India’s COVID-19 emergency. Lancet 2021; 397:1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Sambatakou H, Toskas A, Vaiopoulos G, Giannopoulou M, et al. Mucormycosis: ten-year experience at a tertiary-care center in Greece. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2003; 22:753–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaji AH, Schriger D, Green S.. Looking through the retrospectoscope: reducing bias in emergency medicine chart review studies. Ann Emerg Med 2014; 64:292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 2021; 27:601–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chander J, Kaur M, Singla N, Punia RPS, Singhal SK, Attri AK, et al. Mucormycosis: battle with the deadly enemy over a five-year period in India. J Fungi 2018; 4:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:634–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel A, Agarwal R, Rudramurthy SM, Shevkani M, Xess I, Sharma R, et al. Multicenter epidemiologic study of coronavirus disease-associated mucormycosis, India. Emerg Infect Dis 2021; 27:1–22, doi: 10.3201/eid2709.210934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh AK, Singh R, Joshi SR, Misra A.. Mucormycosis in COVID-19: a systematic review of cases reported worldwide and in India. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2021; 15:102146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satish D, Joy D, Ross A, Balasubramanya. Mucormycosis coinfection associated with global COVID-19: a case series from India. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021; 7:815–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prakash H, Chakrabarti A.. Global epidemiology of mucormycosis. J Fungi 2019; 5:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma S, Grover M, Bhargava S, Samdani S, Kataria T.. Post coronavirus disease mucormycosis: a deadly addition to the pandemic spectrum. J Laryngol Otol 2021; 135:442–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torack RM.Fungus infections associated with antibiotic and steroid therapy. Am J Med 1957; 22:872–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribes JA, Vanover-sams CL, Baker DJ.. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000; 13:236–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH, Lavergne V, Baden L, Cheng VC.. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Infect Dis Soc Am 2021; 0–152. Version 4.3.0. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment (2 July 2021, date last accessed). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. Corticosteroids for COVID-19—Living Guidance. 2020. www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Corticosteroids-2020.1 (2 July 2021, date last accessed).

- 20.Ray A, Goel A, Wig N.. Corticosteroids for treating mild COVID-19: opening the floodgates of therapeutic misadventure. QJM 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhaumik S, John O, Jha V.. Comment low-value medical care in the pandemic—is this what the doctor ordered? Lancet Glob Heal [Internet] 2021; 1:10–1, doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00252-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson GR, Cornely OA, Pappas PG, Patterson TF, Hoenigl M, Jenks JD, et al. Invasive aspergillosis as an under-recognized superinfection in COVID-19. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:4–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Revannavar SM, Supriya PS, Samaga L, Vineeth VK.. COVID-19 triggering mucormycosis in a susceptible patient: a new phenomenon in the developing world? BMJ Case Rep 2021; 14:e241663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhuyan A.Experts criticise India’ s complacency over COVID-19. Lancet 2021; 397:1611–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tandon A.Black Fungus: Experts Flag Role of Industrial Oxygen. Tribune News Service [Internet]. 2021. www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/black-fungus-experts-flag-role-of-industrial-oxygen-256498 (2 July 2021, date last accessed).

- 26.PTI. Experts Divided Over Unhygienic Masks Being Contributing Factor for Black Fungus. The Indian Express [Internet]. 2021. www.indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/experts-divided-over-unhygienic-masks-being-contributing-factor-for-black-fungus-mucormycosis-covid-patients-7323450/ (2 July 2021, date last accessed).

- 27.Gokulshankar S, Mohanty BK.. COVID-19 and black fungus. Asian J Med Heal Sci 2021; 4:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brewster CT, Choong J, Thomas C, Wilson D, Moiemen N.. Steam inhalation and paediatric burns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020; 395:1690–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long B, Koyfman A.. Mucormycosis: what emergency physicians need to know? Am J Emerg Med 2015; 33:1823–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferguson BJ.Mucormycosis of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2000; 33:349–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corzo-León DE, Chora-Hernández LD, Rodríguez-Zulueta AP, Walsh TJ.. Diabetes mellitus as the major risk factor for mucormycosis in Mexico: epidemiology, and identification diagnosis, and outcomes. Med Mycol 2018; 56:29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mishra N, Mutya VSS, Thomas A, Rai G, Reddy B, M AA, et al. A case series of invasive mucormycosis in patients with COVID-19 infection. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021; 7:867–70. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagendra V, Thakkar KD, Hrishi AP, Prathapadas U.. A rare case of rhinocerebral mucormycosis presenting as Garcin syndrome and acute ischemic stroke. Indian J Crit Care Med 2020; 24:1137–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cornely OA, Alastruey-izquierdo A, Arenz D, Chen SCA, Dannaoui E, Hochhegger B, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:e405–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Werthman-Ehrenreich A.Mucormycosis with orbital compartment syndrome in a patient with COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med 2021; 42:264.e5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.