Key Points

Question

Is social isolation associated with poor functional outcomes and 1-year mortality among older adults with critical illness?

Findings

In this nationally representative cohort study including 997 patients, more social isolation was significantly associated with a higher disability burden and increased likelihood of death within 1 year of hospital admission.

Meaning

The study findings suggest that social isolation is a risk factor for poor outcomes among older adults with critical illness.

Abstract

Importance

Disability and mortality are common among older adults with critical illness. Older adults who are socially isolated may be more vulnerable to adverse outcomes for various reasons, including fewer supports to access services needed for optimal recovery; however, whether social isolation is associated with post–intensive care unit (ICU) disability and mortality is not known.

Objectives

To evaluate whether social isolation is associated with disability and with 1-year mortality after critical illness.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This observational cohort study included community-dwelling older adults who participated in the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) from May 2011 through November 2018. Hospitalization data were collected through 2017 and interview data through 2018. Data analysis was conducted from February 2020 through February 2021. The mortality sample included 997 ICU admissions of 1 day or longer, which represented 5 705 675 survey-weighted ICU hospitalizations. Of these, 648 ICU stays, representing 3 821 611 ICU hospitalizations, were eligible for the primary outcome of post-ICU disability.

Exposures

Social isolation from the NHATS survey response in the year most closely preceding ICU admission, which was assessed using a validated measure of social connectedness with partners, families, and friends as well as participation in valued life activities (range 0-6; higher scores indicate more isolation).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the count of disability assessed during the first interview following hospital discharge. The secondary outcome was time to death within 1 year of hospital admission.

Results

A total of 997 participants were in the mortality cohort (511 women [51%]; 45 Hispanic [5%], 682 non-Hispanic White [69%], and 228 non-Hispanic Black individuals [23%]) and 648 in the disability cohort (331 women [51%]; 29 Hispanic [5%], 457 non-Hispanic White [71%], and 134 non-Hispanic Black individuals [21%]). The median (interquartile range [IQR]) age was 81 (75.5-86.0) years (range, 66-102 years), the median (IQR) preadmission disability count was 0 (0-1), and the median (IQR) social isolation score was 3 (2-4). After adjustment for demographic characteristics and illness severity, each 1-point increase in the social isolation score (from 0-6) was associated with a 7% greater disability count (adjusted rate ratio, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01-1.15) and a 14% increase in 1-year mortality risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03-1.25).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, social isolation before an ICU hospitalization was associated with greater disability burden and higher mortality in the year following critical illness. The study findings suggest a need to develop social isolation screening and intervention frameworks for older adults with critical illness.

This cohort study of participants in the National Health and Aging Trends Study examines the association of social isolation with disability burden and mortality for older adults with critical illness.

Introduction

For many community-dwelling older adults, surviving critical illness is associated with a severe and prolonged course of new disability.1 Fewer than half of older intensive care unit (ICU) survivors fully recover their prehospitalization functional ability,2 despite functional independence being considered one of the highest priority goals among older adults who are recovering from serious illness.3 Additionally, nearly 1 in 3 older ICU survivors die within 3 years of discharge, a rate concentrated in the year after discharge and 3 to 5 times higher than that of the general older adult population.4 Identifying older adults most vulnerable to poor outcomes during the ICU hospitalization may facilitate interventions to positively affect the course of recovery.

Social isolation, or an objective lack of social connections, is increasingly recognized as a public health concern for older adults.5 In the US, estimates suggest that more than 1 in 5 older adults lack close social ties, such as meaningful relationships with friends and family.6,7 Among community-dwelling older adults, social isolation is associated with cognitive impairment, disability burden, progression of physical frailty, and elevated mortality rates.8,9,10 For older adults recovering from critical illness, social isolation may have a particularly strong association with poor outcomes. For example, socially isolated older adults may have fewer supports to help access postdischarge services, such as ICU follow-up clinics, and they may also be more susceptible to the negative effects of post-ICU syndrome, which describes the disabling sequelae of emotional, cognitive, and physical impairments that follow critical illness.11 However, to our knowledge, the association between social isolation and recovery from critical illness among older adults has not been studied.

To address this knowledge gap, we used data from a nationally representative study of Medicare beneficiaries 65 years and older. Our objectives were to evaluate the association between pre-ICU social isolation and disability burden after discharge from an ICU hospitalization as well as the association of social isolation with 1-year mortality. We hypothesized that increasing social isolation would be associated with a higher disability burden and greater 1-year mortality.

Methods

Study Sample

Study data were drawn from the 2011 cohort of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), a nationally representative annual survey of late-life disability trends among Medicare beneficiaries.12 The comprehensive design of this complex survey is described elsewhere.13 Briefly, the NHATS 2011 cohort (n = 8245) represents a random sample of adults 65 years and older that was drawn from Medicare enrollment files in 2010, oversampling for the oldest older adults (age >90 years) and non-Hispanic Black individuals. Each survey collected information on demographic characteristics, disability status, health conditions, social connections, and living situation. These survey data were subsequently linked to Medicare claims data. The NHATS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (NIA; grant U01AG032947) through a cooperative agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The Johns Hopkins University institutional review board approved the NHATS protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent. Use of NHATS data for this analysis was approved by the Yale University institutional review board.

Identification of ICU Admissions

We first identified inpatient hospitalizations that included an ICU stay between May 2011 and December 2017 using critical care revenue center codes from the linked Medicare inpatient claims file, excluding stays in an intermediate or psychiatric ICU. We restricted the sample to ICU admissions of 1 day or longer.

Assessment of Social Isolation

The primary predictor was a validated 6-item composite measure of social isolation drawn from NHATS survey items during the year most closely preceding ICU admission.6 These items correspond to 4 core domains of social connectedness: marriage or live-in partnership, contacts with family and friends, membership in a religious organization, and participation in other community groups.14 Participants were asked during each annual NHATS survey about the presence of a live-in partner or spouse, whether they talked with family or friends about important matters, whether they visited with friends or family, and whether they recently participated in religious services or social activities (eMethods in the Supplement). Participants scored 1 point for each negative response, with higher scores (range, 0-6) indicating greater social isolation.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the count of disabilities in 7 activities of daily living (ADLs) and mobility activities at the NHATS interview following discharge from ICU hospitalization. During each annual interview, participants were asked about a need for help from another person in completing each of 7 tasks: getting cleaned up, using the toilet, dressing, eating, getting around inside, going outside, and getting out of bed. Participants were coded as having a disability if they reported needing help from another person or had not completed the task at all within the last month. Total disability counts (range, 0-7) were summed for the interview preceding ICU admission and the round following ICU discharge. For participants who died during the post-ICU follow-up period, disability data were obtained from standardized proxy interviews about participants during the last month of life.

The secondary outcome was time from hospital admission to death, censored at 365 days. Death dates were obtained from the Medicare enrollment files.

Descriptive Characteristics and Covariates

We selected descriptive characteristics and model covariates from the NHATS data. The covariates included those that prior work2,15,16 or clinical experience pointed to as potential confounders of the association between social isolation and outcomes. Participant age, sex, self-reported race (for descriptive purposes), chronic condition count, preadmission disability count, and rural residence were collected from the NHATS interview immediately preceding hospitalization. Preadmission frailty was assessed using modified Fried criteria developed from NHATS interview responses and physical performance measures,17 with participants classified as having frailty (3 of 5 or more frailty criteria) or not having frailty (2 of 5 or fewer). We identified older adults with probable dementia through an algorithm developed by the NHATS study team.18,19 From Medicare claims, we also extracted information on the use of mechanical ventilation from procedure codes in inpatient claims and total hospital length of stay from the hospitalization record. From Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary Files, we captured whether the patient was eligible for Medicaid as a proxy for socioeconomic disadvantage.

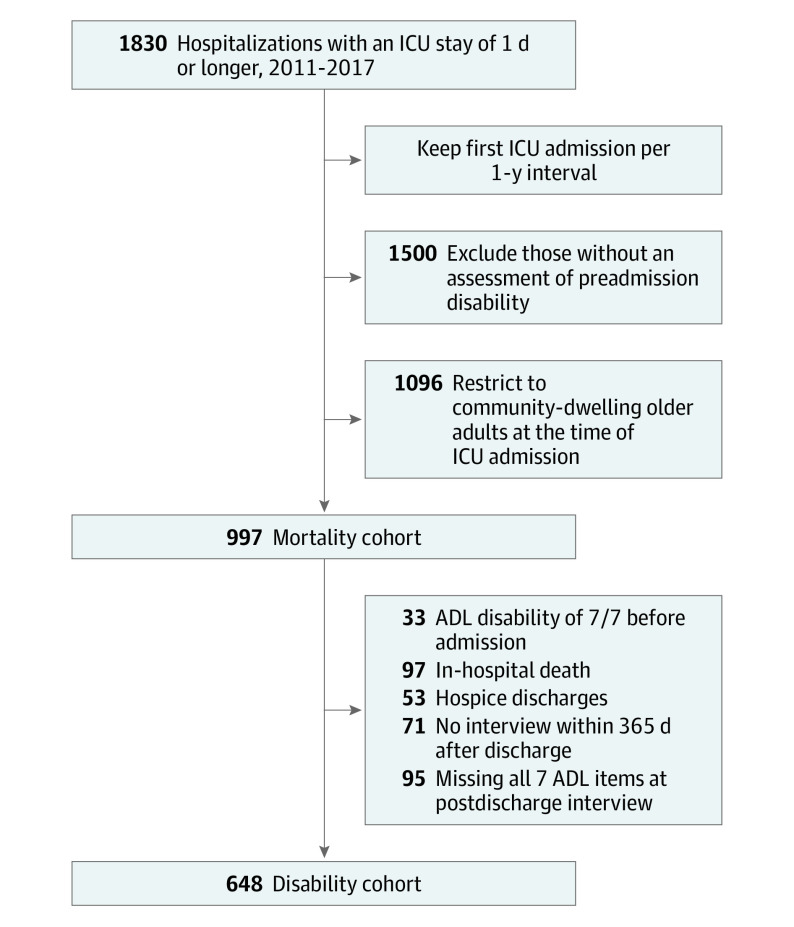

Selection of the Analytic Sample

Selection of the analytic sample is depicted in Figure 1. We identified all patient ICU stays from 2011 through 2017 contributed by the 2011 NHATS cohort. Participants could contribute multiple ICU stays over this period, but for participants who had multiple admissions within the same 12-month period, only the first was retained. We excluded participants with missing data for all 7 ADL and mobility tasks before admission. We then further limited the sample to older adults who were community dwelling at the time of ICU hospitalization. The remaining person-admissions constituted the sample for the secondary outcome of time to death from hospital admission. For the primary outcome of post-ICU disability, we further limited the sample to older adults who survived to hospital discharge and had a disability assessment during an NHATS interview within 365 days, excluding those discharged to hospice. Participants who had a disability in all 7 assessed activities before hospitalization were also excluded, as this population cannot become functionally worse and prior work has shown that patients with maximum disability retain severe disability or die after critical illness.1 We additionally excluded participants with missing data for all 7 functional activities in the posthospitalization interview. The most common reasons for these missing data were patient and proxy refusals (n = 47) or a transition into a nursing home (n = 17).

Figure 1. Assembly of the Analytic Sample From the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) Cohort.

Participants included for the primary analysis of disability count and the secondary outcome of 1-year mortality are shown. ADL indicates activity of daily living; ICU, intensive care unit.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the eligible participants were recorded. Then, to minimize risk of bias associated with missing data (which did not exceed 3% for any variable), and based on an assumption of missing at random, multiple imputation was used to produce 5 imputed data sets. Imputations leveraged all predictor variables in the data set for all eligible NHATS participants across the first 8 years of data collection. The descriptive statistics and imputation were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

We initially plotted the mean count of disability with 95% confidence limits by increasing degree of social isolation. We subsequently evaluated the association between social isolation before hospitalization and count of post-ICU disability using a Poisson regression with generalized estimating equations and an exchangeable correlation structure, the latter to account for those contributing multiple ICU admissions. The multivariable model of post-ICU disability count was adjusted for age, sex, probable dementia, frailty, hospital length of stay, use of mechanical ventilation, chronic condition count, prehospitalization disability count, and rural residence. Because NHATS interviews proxies to ascertain the function of decedents during the last month of life, there was no truncation of follow-up data because of death. The adjusted rate ratios (RRs) reported represent the proportional increase in post-ICU disability that was associated with each incremental rise in the social isolation score (from 0-6). We repeated the multivariable modeling in a sensitivity analysis to evaluate potential biases associated with missing data for older ICU survivors who were admitted to nursing homes (n = 17) during the follow-up period. In this sensitivity analysis, outcome data for this subset of survivors were imputed under assumptions of missingness at random.

The unadjusted association between social isolation score and 1-year mortality from date of hospital admission was presented as a Kaplan-Meier test using the log rank statistic. This outcome was subsequently evaluated with a proportional hazards model that adjusted for the same covariates as the primary outcome in which follow-up was censored at 365 days. Compliance with the assumption of proportional hazards was verified with martingale residuals. Results are presented as adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) that represent the proportional increase in hazard of mortality associated with incremental rise in social isolation.

To adjust for the complex survey design, all multivariable models included analytic weights, strata, and clustering parameters that were specific to the 2011 NHATS cohort. The multivariable models were separately fit to each of the imputations, with successive combining of the estimates using Rubin rules as implemented in SAS-callable SUDAAN (release 11.0.3) for the primary outcome of disability count and in SAS for the 1-year mortality outcome. In all cases, statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P < .05. Data analysis was conducted from February 2020 through February 2021.

Results

The primary analysis of disability included 648 ICU hospitalizations contributed by 543 older adults, which represented 3 812 611 survey-weighted ICU hospitalizations from 2011 through 2017 (Table). The median age (interquartile range [IQR]) of the sample participants was 81 (75.5-86.0) years (range, 66-102 years), 331 of 648 (51%) were women, and 134 of 648 (21%) identified as non-Hispanic Black. The median (IQR) of preadmission social isolation scores was 3 (2-4), and most participants in the sample had no disabilities before hospitalization (median count, 0; IQR, 0-1). In the primary analytic sample of ICU survivors, 60 (9%) underwent mechanical ventilation; of those discharged alive to nonhospice settings, 254 (39%) were discharged to facilities and 394 (61%) to the community. Among ICU survivors, 102 (16%) were readmitted to the ICU within 1 year; the proportion of high social isolation scores was similar among those who were readmitted and those who were not readmitted.

Table. Characteristics of ICU Admissions Contributed by Community-Dwelling Medicare Beneficiaries From 2011 to 2017a.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Disability cohort | Mortality cohortb | |

| No. of ICU admissions | 648 | 997 |

| Weighted No. of ICU admissionsc | 3 812 611 | 5 705 675 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 81 (76-86) | 81 (75-86) |

| Women | 331 (51) | 511 (51) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 29 (5) | 45 (5) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 457 (71) | 682 (69) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 134 (21) | 228 (23) |

| Otherd | 21 (3) | 34 (3) |

| Rural residence | 174 (27) | 243 (24) |

| Medicaid dual eligibility | 130 (20) | 214 (21) |

| No. of chronic conditions, median (IQR), 0-9e | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) |

| Pre-ICU disability count, median (IQR), 0-7f | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-2) |

| Probable dementiag | 96 (15) | 193 (19) |

| Frailty | 209 (33) | 361 (37) |

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR), d | 6 (3-9) | 6 (3-10) |

| Mechanical ventilationh | 60 (9) | 159 (16) |

| Social isolation score, median (IQR), 0 to 6i | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

The data in the Table are presented as unweighted values.

In the full sample (n = 997), values were imputed for 8 hospitalizations with missing race data, 30 hospitalizations with 1 or more missing frailty criteria, 3 hospitalizations with missing social isolation data, and 2 hospitalizations with missing preadmission disabilities.

Estimates after applying National Health and Aging Trends Study analytic survey weights to the total count of ICU admissions.

Includes those who reported their race/ethnicity as Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, other, do not know, or more than 1 race and ethnicity.

Count of 9 self-reported health conditions at interview round preceding ICU hospitalization. These conditions include heart attack, heart disease, high blood pressure, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, and cancer.

Assessed tasks were getting cleaned up, using the toilet, dressing, eating, getting around inside, going outside, and getting out of bed.

Probable dementia (vs possible or no dementia) was assessed using an algorithm developed by the National Heath and Aging Trends Study team based on cognitive data collected during study interviews.

Mechanical ventilation was defined as any claim for International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) procedure codes 96.7 × or ICD-10 codes 5A1935Z, 5A1945Z, or 5A1955Z in the Medicare inpatient file.

From a validated social isolation score ranging from 0 to 6 drawn from National Health and Aging Trends Study interview questions about social connectedness.

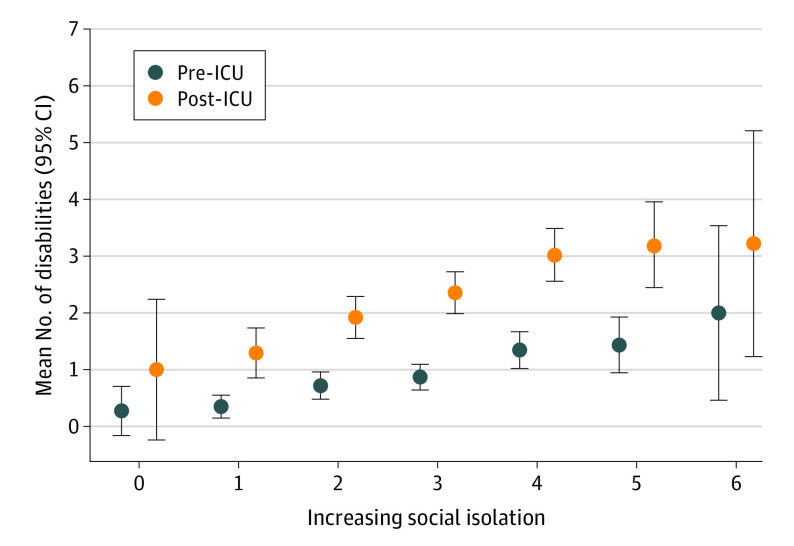

Greater social isolation was associated with a higher mean count of post-ICU disabilities (Figure 2), ranging from an average of 1 disability for the most socially integrated to more than 3 for the most socially isolated. In adjusted models, higher social isolation scores were associated with significantly higher counts of disability after discharge. The count of post-ICU disability was 7% higher with each incremental rise in the social isolation score from 0 to 6 (adjusted RR, 1.07, 95% CI, 1.01-1.15). Compared with the most socially integrated older adults (score, 0 of 6), moderate social isolation among older ICU survivors (score of 3 of 6) was associated with a 23% higher burden of disability, and the most severe social isolation (score of 6 of 6) was associated with a 50% higher disability burden. The sensitivity analysis that included participants who were admitted to nursing homes during the follow-up period yielded similar results (adjusted RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.15).

Figure 2. Unadjusted Count of Disabilities for Older Survivors of Critical Illness Across Levels of Prehospitalization Social Isolation.

The blue markers represent the mean count of disabilities reported during the survey preceding intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and the orange markers represent the count of disabilities reported during the survey following ICU discharge. The error bars represent 95% CIs.

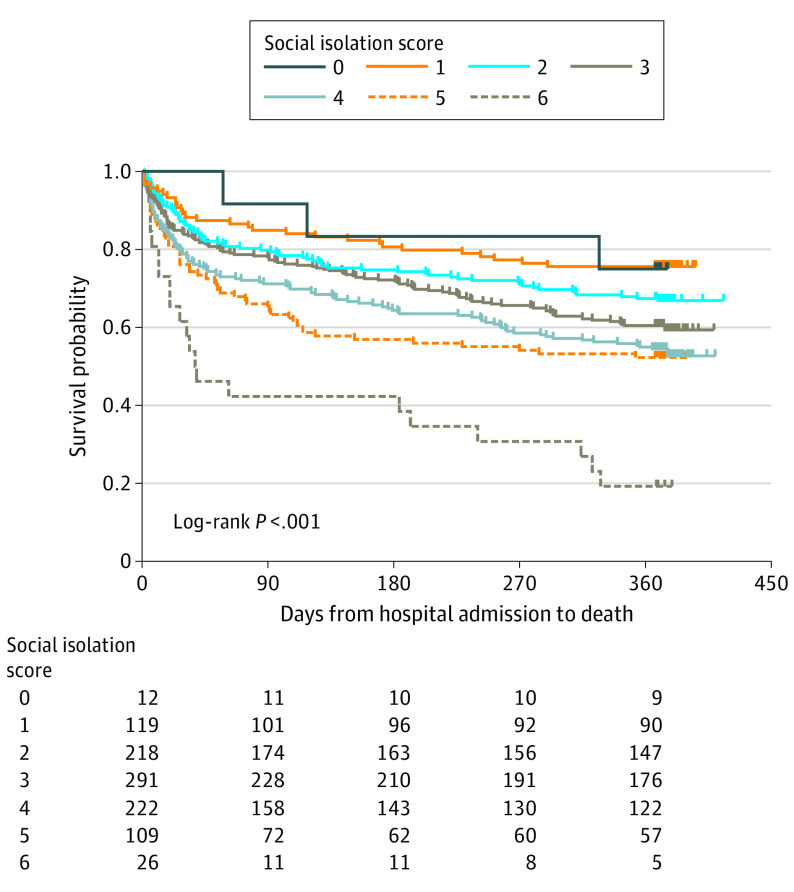

For the time to death outcome, 997 ICU hospitalizations contributed by 834 older adults (representing 5 705 675 survey-weighted admissions) were included in the analytic sample. Increasing social isolation was associated with a significantly higher risk of death within 1 year of hospital admission (Figure 3). In adjusted models, each incremental rise in preadmission social isolation scores (from 0 to 6) was associated with a 14% increase in the hazard of death in the year following hospital admission (aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03-1.25). Compared with the most socially integrated patients (score of 0 of 6), moderate social isolation among older ICU survivors (score of 3 of 6) was associated with a 48% higher hazard of death, while the most severe isolation (score of 6 of 6) was associated with a 119% higher hazard of death.

Figure 3. Mortality Rates Over 1 Year Following Admission for Critical Illness.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for each level of social isolation (0 to 6) are shown, with higher scores indicating greater social isolation.

Discussion

In this nationally representative study of older ICU survivors, we found that greater social isolation was associated with a significant increase in disability burden and risk of mortality in the year after a critical illness. Importantly, the risks associated with social isolation persisted after accounting for geriatric vulnerabilities, illness severity, and socioeconomic disadvantage. These findings suggest that identifying and ameliorating social isolation may play a role in improving outcomes after critical illness.

Our findings complement an extensive body of work demonstrating that socially isolated community-dwelling older adults are more likely to report lower health-related quality of life and are at greater risk of disability, dementia, and mortality.5,10,20 While the data used in our work do not permit us to examine the mechanisms that may be driving the association between social isolation and poor outcomes after critical illness, it is plausible that social isolation complicates recovery in 3 distinct ways. First, the biological impairments associated with social isolation (eg, negative changes in neuroendocrine function and an increase in systemic inflammation biomarkers)5 may increase vulnerability to disability and mortality. Second, socially isolated older adults may be more likely to experience challenges accessing important health care services (eg, primary care, rehabilitation) after a critical illness, so disabling impairments, such as muscle weakness, may be more likely to be left unaddressed. Our prior work has found that living alone, one component of social isolation, is associated with lower rehabilitation use among older ICU survivors.21 Third, those with few social connections may have trouble navigating the complicated process of acquiring important supports, such as durable medical equipment. Unmet needs for assistance with ADLs (eg, need for a shower chair) have been identified as a concern among ICU survivors22; this concern is likely amplified in the absence of close friends or family members who can assist with advocacy for or installation of needed equipment.

Addressing social isolation has increased in urgency, considering recent research that suggests that between 21% and 24% of community-dwelling older adults in the US are socially isolated.6,7 Concerns about social isolation among older adults have intensified during the recent COVID-19 pandemic.23 Infection control and risk-mitigation strategies, such as shelter-in-place orders, were well-meaning but inevitably increased social isolation.24 Yet, there is a paucity of intervention frameworks to guide identification and treatment of socially isolated older adults.

A recent report by the National Academy of Medicine concluded that hospital stays constitute an ideal opportunity to identify social isolation and initiate referrals that merge individual and community-level interventions.5 Indeed, hospitalization may represent the only opportunity to identify the most socially isolated older adults. Nevertheless, screening for social isolation is not a common practice during hospitalization; although caregiver supports are often documented, social interconnectedness is rarely assessed. This study suggests that social isolation should be routinely assessed during hospital admissions; prior work has suggested that it is feasible to include social isolation measures in electronic medical records.25

If social isolation is identified during an ICU stay, how best to address this vulnerability is an open question. However, there are promising intervention frameworks that could be adapted. First, there is growing interest in developing peer support models for ICU survivors. These models, designed to offer emotional and social supports for older adults,26 may have an ancillary benefit of increasing social connectedness. Such groups often occur in outpatient settings, and it is not yet clear whether participation is feasible for older ICU survivors who have deficits in mobility and ADL function. However, emerging virtual formats may allow greater participation among those who have difficulty attending clinic-based groups.27 Second, at least one large medical center has begun offering weekly phone calls to isolated older adults by community volunteers, and another has developed a “Geriatric Buddy” program to facilitate social engagement.25 Interventions that encourage meaningful human interactions are unlikely to cause harm and should be considered for socially isolated older adults after an ICU stay. Third, transportation interventions, such as assisting older ICU survivors with completing applications for door-to-door public transit options, may help support attendance at follow-up medical appointments and provide an avenue through which to facilitate social connections. Future research should evaluate whether these interventions improve outcomes among older ICU survivors.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, social isolation was assessed during a 1-year period before ICU admission and could have changed before the index admission. Second, we excluded a few participants with maximal disability (ie, those who had disability in all 7 functional activities) during the pre-ICU NHATS survey from the primary analysis of post-ICU disability because it was not possible for them to become functionally worse, so our disability results may not be generalizable to older adults who have maximum disability at baseline. However, this group was eligible for and included in the mortality analysis. Third, some older adults died during the postdischarge follow-up, and their functional limitations during the last month of life were reported by proxies, which may introduce recall bias. However, the NHATS methods draw from prior studies that have shown concordance between proxy reports of basic ADL function and patient reports.28,29

Conclusions

The results of this cohort study suggest that social isolation was common among older survivors of critical illness and was associated with a higher burden of disability and an increased risk of death in the year following ICU admission. These findings suggest an urgent need to develop in-hospital screening tools and intervention frameworks to support socially isolated older adults who are recovering from critical illness.

eMethods. Additional Details on Social Isolation Scale Items and Scoring

eReferences.

References

- 1.Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Gill TM. Functional trajectories among older persons before and after critical illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):523-529. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Gill TM. Factors associated with functional recovery among older intensive care unit survivors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(3):299-307. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1256OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1061-1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wunsch H, Guerra C, Barnato AE, Angus DC, Li G, Linde-Zwirble WT. Three-year outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries who survive intensive care. JAMA. 2010;303(9):849-856. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academies of Sciences . Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. National Academies Press; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pohl JS, Cochrane BB, Schepp KG, Woods NF. Measuring social isolation in the national health and aging trends study. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2017;10(6):277-287. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20171002-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cudjoe TKM, Roth DL, Szanton SL, Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Thorpe RJ Jr. The epidemiology of social isolation: National health and aging trends study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(1):107-113. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward M, May P, Normand C, Kenny RA, Nolan A; Findings from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing . Mortality risk associated with combinations of loneliness and social isolation. Age Ageing. 2021;50(4):1329-1335. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies K, Maharani A, Chandola T, Todd C, Pendleton N. The longitudinal relationship between loneliness, social isolation, and frailty in older adults in England: a prospective analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(2):e70-e77. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30038-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shankar A, McMunn A, Demakakos P, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Social isolation and loneliness: prospective associations with functional status in older adults. Health Psychol. 2017;36(2):179-187. doi: 10.1037/hea0000437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502-509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health & Aging Trends Study . NHATS public use data: rounds 1 to 8. Accessed July 2, 2021. http://www.nhats.org.

- 13.Kasper JD, Freedman VA. Findings from the 1st round of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS): introduction to a special issue. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(suppl 1):S1-S7. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(2):186-204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Gill TM. The association of frailty with post-ICU disability, nursing home admission, and mortality: a longitudinal study. Chest. 2018;153(6):1378-1386. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrante LE, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Pisani MA, Gill TM. Pre–intensive care unit cognitive status, subsequent disability, and new nursing home admission among critically ill older adults. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(5):622-629. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201709-702OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandeen-Roche K, Seplaki CL, Huang J, et al. Frailty in older adults: a nationally representative profile in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1427-1434. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amjad H, Roth DL, Sheehan OC, Lyketsos CG, Wolff JL, Samus QM. Underdiagnosis of dementia: an observational study of patterns in diagnosis and awareness in US older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1131-1138. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4377-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Classification of persons by dementia status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study: technical paper 5. Accessed February 28, 2021. http://www.nhats.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/Dementia%20Classification%20with%20Programming%20Statements.zip.

- 20.Coyle CE, Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. 2012;24(8):1346-1363. doi: 10.1177/0898264312460275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falvey JR, Murphy TE, Gill TM, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Ferrante LE. Home health rehabilitation utilization among Medicare beneficiaries following critical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(7):1512-1519. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Major ME, van Nes F, Ramaekers S, Engelbert RHH, van der Schaaf M. Survivors of critical illness and their relatives: a qualitative study on hospital discharge experience. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(11):1405-1413. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201902-156OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e256. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotwal AA, Holt-Lunstad J, Newmark RL, et al. Social isolation and loneliness among San Francisco Bay Area older adults during the COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(1):20-29. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Escalante E, Golden RL, Mason DJ. Social isolation and loneliness: imperatives for health care in a post-COVID world. JAMA. 2021;325(6):520-521. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McPeake J, Hirshberg EL, Christie LM, et al. Models of peer support to remediate post-intensive care syndrome: a report developed by the Society of Critical Care Medicine Thrive International Peer Support Collaborative. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):e21-e27. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lassen-Greene CL, Nordness M, Kiehl A, Jones A, Jackson JC, Boncyk CS. Peer support group for intensive care unit survivors: perceptions on supportive recovery in the era of social distancing. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(1):177-182. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-799RL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long K, Sudha S, Mutran EJ. Elder-proxy agreement concerning the functional status and medical history of the older person: the impact of caregiver burden and depressive symptomatology. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(9):1103-1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06648.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM, Hebel JR. Patient-proxy response comparability on measures of patient health and functional status. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1065-1074. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90076-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Additional Details on Social Isolation Scale Items and Scoring

eReferences.