Abstract

Aim

Experimental animals, such as non-human primates (NHPs), mice, Zebrafish, and Drosophila, are frequently employed as models to gain insights into human physiology and pathology. In developmental neuroscience and related research fields, information about the similarities of developmental gene expression patterns between animal models and humans is vital to choose what animal models to employ. Here, we aimed to statistically compare the similarities of developmental changes of gene expression patterns in the brains of humans with those of animal models frequently used in the neuroscience field.

Methods

The developmental gene expression datasets that we analyzed consist of the fold-changes and P values of gene expression in the brains of animals of various ages compared with those of the youngest postnatal animals available in the dataset. By employing the running Fisher algorithm in a bioinformatics platform, BaseSpace, we assessed similarities between the developmental changes of gene expression patterns in the human (Homo sapiens) hippocampus with those in the dentate gyrus (DG) of the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta), the DG of the mouse (Mus musculus), the whole brain of Zebrafish (Danio rerio), and the whole brain of Drosophila (D. melanogaster).

Results

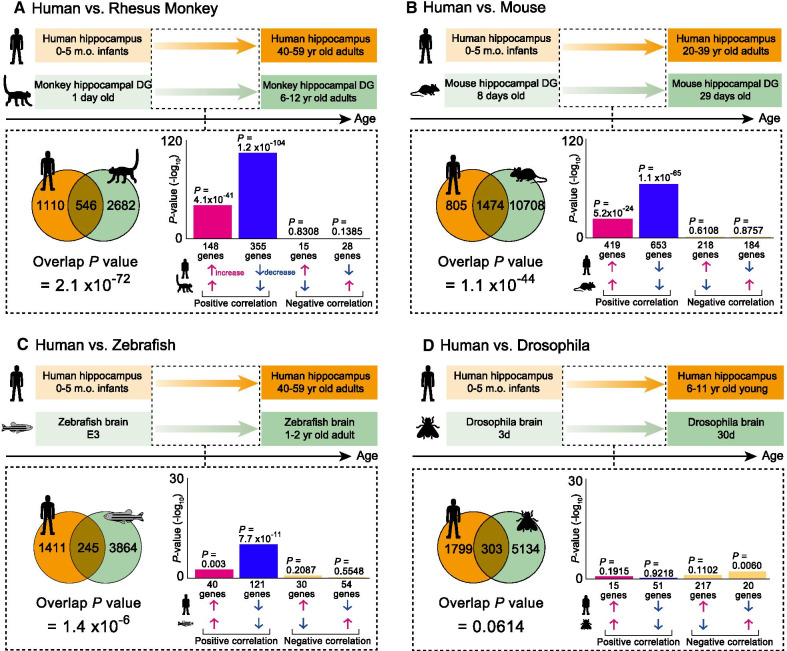

Among all possible comparisons of different ages and animals in developmental changes in gene expression patterns within the datasets, those between rhesus monkeys and mice were highly similar to those of humans with significant overlap P-value as assessed by the running Fisher algorithm. There was the highest degree of gene expression similarity between 40–59-year-old humans and 6–12-year-old rhesus monkeys (overlap P-value = 2.1 × 10− 72). The gene expression similarity between 20–39-year-old humans and 29-day-old mice was also significant (overlap P = 1.1 × 10− 44). Moreover, there was a similarity in developmental changes of gene expression patterns between 1–2-year-old Zebrafish and 40–59-year-old humans (Overlap P-value = 1.4 × 10− 6). The overlap P-value of developmental gene expression patterns between Drosophila and humans failed to reach significance (30 days Drosophila and 6–11-year-old humans; overlap P-value = 0.0614).

Conclusions

These results indicate that the developmental gene expression changes in the brains of the rhesus monkey, mouse, and Zebrafish recapitulate, to a certain degree, those in humans. Our findings support the idea that these animal models are a valid tool for investigating the development of the brain in neurophysiological and neuropsychiatric studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13041-021-00840-4.

Keywords: Gene expression, Development, Human, Rhesus monkey, Mouse, Zebrafish, Drosophila, RNA-seq

The use of animal models is invaluable for elucidating the underlying mechanisms of human physiology and pathology. Depending on many circumstances, such as the ethical requirements, the purpose of experiments, and efficiency of breeding, different species of experimental animals are employed for experiments. Among various types of animal models, non-human primates (NHPs) have the highest degree of genetic identity to humans, given their relatively recent evolutionary divergence from that of human beings [1, 2], and NHPs are employed in cases where primate-specific functions are the subject to study [3, 4], although the strictest ethical consideration is necessary. Mice also have similarities in gene expression patterns with humans [5]. They have advantages in rich genetic resources, their small size, ease of maintenance, and short life cycle, enabling the effective implementation of the diseases of humans [6–9]. Non-mammal animals, such as Zebrafish [10–17], and Drosophila [18–21], are also employed as experimental animals because of their technical advantages in maintenance, spatial requirements, fertility, genetic manipulation, and observation. In developmental neuroscience and the related fields using animal models, information about the developmental changes of the gene expression patterns in the brain of experimental animals and their correlation with human transcriptomics are important. Bakken et al. (2016) carried out a comprehensive transcriptional mapping of brain development in rhesus monkeys and compared the gene expression patterns in the frontal cortex with human’s and rat’s. They estimated the number of overlapping gene expressions in development and suggested that the number of overlapping genes between rhesus monkeys and humans was significantly higher than that between rats and humans using non-parametric statistical tests [22]. Gerstein et al. (2014) compared transcriptome across distant species and discovered that co-expression modules shared across humans, C-elegans, and Drosophila, many of which are enriched in developmental genes [23]. Howe et al. (2013) investigated genomic sequences between humans and Zebrafish and found that approximately 70 % of human genes have at least one obvious zebrafish orthologue [24]. However, quantitative information on the transcriptomic similarity across multiple species of animal models is still limited.

Here, using running Fisher analysis available in BaseSpace correlation engine (Illumina, San Diego, CA), we evaluated the similarity of developmental transcriptomes across different species (Additional file 3). We employed “overlap P-values” calculated from fold changes of gene expression, the P-values of the fold changes of the individual gene expressions, and their ranks [25]. This method allowed us to quantify the similarities in developmental changes of the gene expression pattern of brains between humans [26] and commonly-used animal models, consisting of rhesus monkeys [27], mice [28], Zebrafish [29], and Drosophila [21]. Dataset of the fold-changes and the P-values of gene expression of human that we analyzed consist of those from infants to elderly (6–12 months old, 1–5, 6–11, 12–19, 20–39, 40–59, and over 60 years old) in comparison with 0–5 months old infants. Likewise, those of mice from young to adult stages up to 6 months old (11, 14, 17, 21, 25, 29 days, and 6 months old) in comparison with young mice (8 days old), those of Zebrafish from the young to aged (Embryonic stage E5, E10, 3 months old, 1–2 years old) in comparison with E3, those of Drosophila from the 30 days old and the 60 days old in comparison with the 3 days old, were subjected to the present study.

We first compared the developmental gene expression changes between the human hippocampus [26] and the hippocampal DG of rhesus monkeys [27] available in BaseSpace. Among 21 combinations of the available datasets from different ages of humans and rhesus monkeys (Additional file 2: Table S1), there was the highest degree of gene expression similarity between those of 40–59-year-old humans and 6–12-year-old rhesus monkeys (Fig. 1A, overlap P-value = 2.1 × 10− 72), with 546 genes altered in both humans and rhesus monkeys. 503 genes out of those genes showed the same directional change in expression and, of these genes, 148 genes were upregulated (Fig. 1A, magenta bar; P = 4.1 × 10− 41), and 355 were downregulated (Fig. 1A, blue bar: P = 1.2 × 10− 104). Likewise, we compared similarities of the developmental gene expression changes of the human hippocampus [26] and hippocampal DG of mice that are available from Murano et al. (2019) [28]. Among the 49 combinations of datasets from different ages of humans and mice (Additional file 2: Table S1), the one between those of 20–39-year-old humans and 29-day old mice recorded the highest degree of gene expression overlap (Fig. 1B, overlap P value = 1.1 × 10− 44; 1474 genes altered in both humans and mice). The same directional change in gene expression was observed in 1072 genes, of which 419 genes were upregulated (Fig. 1B, magenta bar; P = 5.2 × 10− 24) and 653 downregulated (Fig. 1B, blue bar; P = 1.1 × 10− 65). Among 56 combinations of the datasets of the human hippocampus [26] and Zebrafish brain [29], 40-59-year-old humans and 1-2-year-old Zebrafish exhibited the highest degree of gene expression overlap (Fig. 1C, overlap P-value = 1.4 × 10− 6; 245 genes altered in both humans and Zebrafish). The same directional change in expression was observed in 161 genes, of which 40 were upregulated (Fig. 1C, magenta bar; P = 0.003) and 121 downregulated (Fig. 1C, blue bar; P = 7.7 × 10− 11). Finally, regarding the 14 combinations between the human hippocampus [26] and Drosophila brain [21] that we assessed, we identified the highest degree of gene expression overlap between those of 6–11-year-old humans and 30 days Drosophila (Fig. 1D, overlap P-value = 0.0614), with 303 genes altered in both humans and Drosophila. The same directional change in expression occurred in 66 genes, of which 15 genes were upregulated (Fig. 1D, magenta bar; P = 0.1915) and 51 downregulated (Fig. 1D, blue bar; P = 0.9218).

Fig. 1.

Similarities in temporal transcriptomics between brains of human and experimental animals: rhesus monkey, mouse, Zebrafish, and Drosophila. A–D The representative combination, which resulted in the lowest overlap P-value among all the data from developmental stages in each animal dataset (also see Additional file 2: Table S1), is indicated. Comparison of gene expression patterns in the human hippocampus of 40–59-year-old adults compared with those of the hippocampal dentate gyrus of 6–12-year-old adult monkeys (A). The Venn diagram indicates that there were 546 common genes whose expression levels significantly changed with aging in both hippocampi of 40–59-year-old adults and hippocampal DG of 6–12-year-old adult monkeys, and the overlap P-value, as assessed by running Fisher analysis, was 2.1 × 10− 72. The right bar graphs indicate that, within the 546 common genes, the expression of 148 genes increased and 355 genes decreased in both humans and monkeys (i.e., positive correlation); expression of 15 genes increased and decreased in humans and monkeys, respectively; and the expression of 28 genes decreased and increased in humans and monkeys, respectively (i.e., negative correlation). The overlap P-values of these different types of correlations are also indicated above the corresponding bar graph. Likewise, gene expression patterns in the human hippocampus of 20–39-year-old adults compared with those of the hippocampal dentate gyrus of 29-day-old mice (B), gene expression patterns in the human hippocampus of 40–59-year-old adults compared with those of the brain of 1-2-year-old adult zebrafish (C), and gene expression patterns in the hippocampus of 6–11-year-old young humans compared with those of the 30-day old Drosophila brain (D), are indicated in the same manner with (A). DG dentate gyrus, E embryonic day, m.o. months old, yr year, d day

We have confirmed that rhesus monkeys, mice, and Zebrafish, which belong to deuterostomes, have developmental changes of gene expression patterns that are significantly similar to those of humans. In contrast, the developmental changes of the gene expression pattern of the brain of Drosophila, which belongs to protostomes, were not significantly correlated with those of humans. In Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), which also belongs to protostomes, the developmental changes of the gene expression pattern of whole-body samples were weakly and negatively correlated with those of human brains (Additional file 1: Fig. S1 and Additional file 2: Table S6) [30]. Overall, the degrees of similarity between animal models and humans shown in this report tended to reflect their evolutionary distance from humans. It should be noted that we have conducted the analyses using publicly available data, of which subjected brain regions and developmental stages are not perfectly matched across the included species. For example, the sampling resolution and period of developmental stages differ across the animals, and the datasets of rhesus monkeys and mice do not contain the data from embryonic stages, while the datasets of humans and Zebrafish do. Also, the developmental transcriptomics data of C. elegans was obtained from whole-body, and so it is hard to directly compare its data with those from the other species evaluated in this study. Despite these limitations, this study indicates that gene expression patterns in rhesus monkeys, mice, and zebrafish match those in humans. These findings thus support the validity of these animal models for studying human brain development and development-related functions and dysfunctions.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Correlation of temporal transcriptomics between brains of humans and whole-bodies of C. elegans.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Matrix table of the overlap P-values of temporal transcriptomics between all the available ages of the brains of human and experimental animals: rhesus monkey, mouse, Zebrafish, and Drosophila. Table S2. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 40–59-year-old humans and in the DG of 6–12-year-old rhesus monkeys (fold change and rank; Fig. 1A). Table S3. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 20–39-year-old humans and in the DG of 629-day-old mice (fold change and rank; Fig. 1B). Table S4. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 40–59-year-old humans and in 1–2-year-old adult zebrafish brain (fold change and rank; Fig. 1C). Table S5. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 6–11-year-old young humans and in 30-day old Drosophila brain (fold change and rank; Fig. 1D). Table S6. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 6–11-year-old young humans and in 4 days old C. elegans (fold change and rank). Table S7. Top-40 of the correlating gene expression.

Additional file 3. Method for the calculation of overlap P-value by running Fisher analysis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Giovanni Sala for his proof readings and valuable comments on statistics; Satoko Hattori, Tomoyuki Murano, Johannes Dijkstra, and Hisatsugu Koshimizu for general comments on the present report. We also thank Chikako Ozeki, Wakako Hasegawa, Yumiko Mobayashi, Misako Murai, Tamaki Murakami, Miwa Takeuchi, Yoko Kagami, Harumi Mitsuya, and Yoshihiro Takamiya for their technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- NHPs

Non-human primates

- DG

Dentate gyrus

Authors’ contributions

RN performed the analysis of the datasets and wrote the manuscript. HH and TM helped draft the manuscript. TM supervised all aspects of the present study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP25242078, JP16H06462, and JP20H00522; and AMED under Grant Number JP19dm0107101h0004.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available as Additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The publicly available gene expression datasets of human, rhesus monkey, Zebrafish, and Drosophila analyzed in this study were obtained from previous studies conducted elsewhere with the approvals of human or animal study ethics committees, and the human dataset used in this study does not contain any information which identifies a person. The gene expression dataset of the mice was obtained from Murano et al. (2019) [28], which was approved by the Animal Research Committee in Fujita Health University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests with regard to the present article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Disotell TR, Tosi AJ. The monkey’s perspective. Genome Biol. 2007;8(9):226. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belmonte JCI, Callaway EM, Caddick SJ, Churchland P, Feng G, Homanics GE, et al. Brains, genes, and primates. Neuron. 2015;86(3):617–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey J. Monkey-based research on human disease: the implications of genetic differences. Altern Lab Anim. 2014;42(5):287–317. doi: 10.1177/026119291404200504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Chen K, Pan M, Ge W, He Z. Comparison of proteome alterations during aging in the temporal lobe of humans and rhesus macaques. Exp Brain Res. 2020;238(9):1963–76. doi: 10.1007/s00221-020-05855-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takao K, Miyakawa T. Genomic responses in mouse models greatly mimic human inflammatory diseases. PNAS. 2015;112(4):1167–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401965111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakajima R, Hattori S, Funasaka T, Huang FL, Miyakawa T. Decreased nesting behavior, selective increases in locomotor activity in a novel environment, and paradoxically increased open arm exploration in Neurogranin knockout mice. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Gerber DJ, Hall D, Miyakawa T, Demars S, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M, et al. Evidence for association of schizophrenia with genetic variation in the 8p21.3 gene, PPP3CC, encoding the calcineurin gamma subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(15):8993–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432927100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyakawa T, Leiter LM, Gerber DJ, Gainetdinov RR, Sotnikova TD, Zeng H, et al. Conditional calcineurin knockout mice exhibit multiple abnormal behaviors related to schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(15):8987–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432926100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyakawa T, Yared E, Pak JH, Huang FL, Huang KP, Crawley JN. Neurogranin null mutant mice display performance deficits on spatial learning tasks with anxiety related components. Hippocampus. 2001;11(6):763–75. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braubach OR, Wood H-D, Gadbois S, Fine A, Croll RP. Olfactory conditioning in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) Behav Brain Res. 2009;198(1):190–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braubach OR, Fine A, Croll RP. Distribution and functional organization of glomeruli in the olfactory bulbs of zebrafish (Danio rerio) J Comp Neurol. 2012;520(11):2317–39. doi: 10.1002/cne.23075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braubach OR, Miyasaka N, Koide T, Yoshihara Y, Croll RP, Fine A. Experience-dependent versus experience-independent postembryonic development of distinct groups of Zebrafish olfactory glomeruli. J Neurosci. 2013;33(16):6905–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5185-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng R-K, Jesuthasan SJ, Penney TB. Zebrafish forebrain and temporal conditioning. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2020 Dec 10];369(1637). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3895987/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Inomata C, Yuikawa T, Nakayama-Sadakiyo Y, Kobayashi K, Ikeda M, Chiba M, et al. Involvement of an Oct4-related PouV gene, pou5f3/pou2, in neurogenesis in the early neural plate of zebrafish embryos. Dev Biol. 2020;457(1):30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okumura K, Kakinuma H, Amo R, Okamoto H, Yamasu K, Tsuda S. Optical measurement of neuronal activity in the developing cerebellum of zebrafish using voltage-sensitive dye imaging. Neuroreport. 2018;29(16):1349–54. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradbury J. Small fish, big science. PLoS Biol. 2004;11(5):e148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asakawa K, Suster ML, Mizusawa K, Nagayoshi S, Kotani T, Urasaki A, et al. Genetic dissection of neural circuits by Tol2 transposon-mediated Gal4 gene and enhancer trapping in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(4):1255–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704963105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue S, Shimoda M, Nishinokubi I, Siomi MC, Okamura M, Nakamura A, et al. A role for the Drosophila fragile X-related gene in circadian output. Curr Biol. 2002;12(15):1331–5. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plantié E, Migocka-Patrzałek M, Daczewska M, Jagla K. Model organisms in the fight against muscular dystrophy: lessons from drosophila and Zebrafish. Molecules. 2015;9(4):6237–53. doi: 10.3390/molecules20046237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chartier A, Benoit B, Simonelig M. A Drosophila model of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy reveals intrinsic toxicity of PABPN1. EMBO J. 2006;25(10):2253–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu N, Landreh M, Cao K, Abe M, Hendriks G-J, Kennerdell JR, et al. The microRNA miR-34 modulates ageing and neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Nature. 2012;482(7386):519–23. doi: 10.1038/nature10810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakken TE, Miller JA, Ding S-L, Sunkin SM, Smith KA, Ng L, et al. Comprehensive transcriptional map of primate brain development. Nature. 2016;535(7612):367–75. doi: 10.1038/nature18637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerstein MB, Rozowsky J, Yan K-K, Wang D, Cheng C, Brown JB, et al. Comparative analysis of the transcriptome across distant species. Nature. 2014;512(7515):445–8. doi: 10.1038/nature13424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howe K, Clark MD, Torroja CF, Torrance J, Berthelot C, Muffato M, et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature. 2013;496(7446):498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupershmidt I, Su QJ, Grewal A, Sundaresh S, Halperin I, Flynn J, et al. Ontology-based meta-analysis of global collections of high-throughput public data. Aziz RK, editor. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9):e13066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang HJ, Kawasawa YI, Cheng F, Zhu Y, Xu X, Li M, et al. Spatio-temporal transcriptome of the human brain. Nature. 2011;478(7370):483–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavenex P, Sugden SG, Davis RR, Gregg JP, Lavenex PB. Developmental regulation of gene expression and astrocytic processes may explain selective hippocampal vulnerability. Hippocampus. 2011;21(2):142–9. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murano T, Hagihara H, Tajinda K, Matsumoto M, Miyakawa T. Transcriptomic immaturity inducible by neural hyperexcitation is shared by multiple neuropsychiatric disorders. Commun Biol. 2019;22(1):32. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0277-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toyama R, Chen X, Jhawar N, Aamar E, Epstein J, Reany N, et al. Transcriptome analysis of the zebrafish pineal gland. Dev Dyn. 2009;238(7):1813–26. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golden TR, Hubbard A, Dando C, Herren MA, Melov S. Age-related behaviors have distinct transcriptional profiles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2008;7(6):850–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Correlation of temporal transcriptomics between brains of humans and whole-bodies of C. elegans.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Matrix table of the overlap P-values of temporal transcriptomics between all the available ages of the brains of human and experimental animals: rhesus monkey, mouse, Zebrafish, and Drosophila. Table S2. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 40–59-year-old humans and in the DG of 6–12-year-old rhesus monkeys (fold change and rank; Fig. 1A). Table S3. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 20–39-year-old humans and in the DG of 629-day-old mice (fold change and rank; Fig. 1B). Table S4. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 40–59-year-old humans and in 1–2-year-old adult zebrafish brain (fold change and rank; Fig. 1C). Table S5. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 6–11-year-old young humans and in 30-day old Drosophila brain (fold change and rank; Fig. 1D). Table S6. Gene expression in the hippocampus of 6–11-year-old young humans and in 4 days old C. elegans (fold change and rank). Table S7. Top-40 of the correlating gene expression.

Additional file 3. Method for the calculation of overlap P-value by running Fisher analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available as Additional files.