Abstract

Aim

The Prevention of Arrhythmia Device Infection Trial (PADIT) infection risk score, developed based on a large prospectively collected data set, identified five independent predictors of cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infection. We performed an independent validation of the risk score in a data set extracted from U.S. healthcare claims.

Methods and results

Retrospective identification of index CIED procedures among patients aged ≥18 years with at least one record of a CIED procedure between January 2011 and September 2014 in a U.S health claims database. PADIT risk factors and major CIED infections (with system removal, invasive procedure without system removal, or infection-attributable death) were identified through diagnosis and procedure codes. The data set was randomized by PADIT score into Data Set A (60%) and Data Set B (40%). A frailty model allowing multiple procedures per patient was fit using Data Set A, with PADIT score as the only predictor, excluding patients with prior CIED infection. A data set of 54 042 index procedures among 51 623 patients with 574 infections was extracted. Among patients with no history of prior CIED infection, a 1 unit increase in the PADIT score was associated with a relative 28% increase in infection risk. Prior CIED infection was associated with significant incremental predictive value (HR 5.66, P < 0.0001) after adjusting for PADIT score. A Harrell’s C-statistic for the PADIT score and history of prior CIED infection was 0.76.

Conclusion

The PADIT risk score predicts increased CIED infection risk, identifying higher risk patients that could potentially benefit from targeted interventions to reduce the risk of CIED infection. Prior CIED infection confers incremental predictive value to the PADIT score.

Keywords: Infection, Pacemaker, Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, Risk score

Graphical Abstract

What’s new?

Cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infection is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and cost. Multivariable risk scores, to identify patients at risk of infection after primary or secondary CIED procedures, have been developed—but due to lack of external validation, their use in clinical practice is not commonplace.

We performed an independent validation of the recently developed Prevention of Arrhythmia Device Infection Trial (PADIT) risk score in a data set extracted from US healthcare claims, which included 54 042 index procedures among 51 623 patients with 574 infections.

We report that the relative risk of a major CIED infection increases by 28% for each one unit increase in the PADIT risk score. Inclusion of prior CIED infection history as an additional risk factor increased the predictive value of the score.

The PADIT risk score could potentially be used in clinical practice to identify patients who may benefit from targeted interventions to reduce infection risk during implant, upgrade or revision.

Introduction

Cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) have become prevalent lifesaving and improving technologies, with a growing rate of implantation over the last decade.1 Despite significant advances in surgical technique and use of peri-operative antibiotics, infection remains the most common indication for CIED extraction.2 Device-related infection is not a benign complication; it is associated with significantly increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare cost.3–6

Defining predictors of increased CIED infection risk can aid in the development of patient specific peri-implant strategies to reduce infection. The recent Prevention of Arrhythmia Device Infection Trial (PADIT) study used a large, prospectively collected data set to identify independent predictors of device infection.7,8 The PADIT infection risk score was subsequently developed and is composed of age, procedure type, renal insufficiency, immunocompromised status, and number of previous procedures (Table 1). While these observations are consistent with a meta-analysis of several smaller studies,9 the authors advocated for validation of the risk score in an independent cohort, and consideration of predictors that were missing from the PADIT data set. In this context, we performed an independent validation of the PADIT risk score using a data set extracted from U.S. healthcare claims.

Table 1.

PADIT risk score

| Predictor | PADIT risk score points |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <60 | 2 |

| 60–69 | 1 |

| ≥70 | 0 |

| Procedure typea | |

| Pacemaker | 0 |

| ICD | 2 |

| CRT | 4 |

| Revision/upgrade | 4 |

| Renal insufficiencyb | 1 |

| Immunocompromisedc | 3 |

| Prior procedure(s)d | |

| None | 0 |

| One | 1 |

| Two or more | 3 |

The table shows the points for each of the 5 independent predictors (P: prior procedures; A: age; D: depressed estimated glomerular filtration rate; I: immunocompromised; and T: type of procedure).7,8 The risk score assigns weighted points based on characteristics of the procedure and the patient’s medical history (predictors) and determines the level of risk based on the total number of accumulated points, which categorizes patients into low (0–4), intermediate (5–6), and high (≥7) risk groups.

New pacemaker/ICD/CRT pacemaker or defibrillator or generator change; revision/upgrade includes pocket and/or lead revision and/or system upgrade, that is, with adding new lead(s).

Depressed renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min).

Receiving therapy that suppresses resistance to infection or has a disease that is sufficiently advanced to suppress resistance to infection.

Prior procedure(s) is inclusive of all procedures on the same pocket and including de novo implant.

CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PADIT, Prevention of Arrhythmia Device Infection Trial.

Methods

Data and patient selection

A retrospective analysis using Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart Database was performed. This database includes approximately 17–19 million annual covered lives, including both Commercial and Medicare Advantage health plan data.10. According to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the use of de-identified data did not require institutional review board (IRB) approval or a waiver of authorization.11

The study population included patients aged ≥18 years, with at least one record of a CIED procedure between January 2011 and September 2014, with at least 12-months of continuous health plan enrolment prior to their index CIED procedure date.

A CIED index procedure was defined as any of the following: CIED implant, replacement, revision, or upgrade. A patient could have multiple CIED procedures in the claims data set and therefore contribute multiple index dates. Multiple procedures per patient were selected to ensure a representation of all procedures instead of a bias towards earlier or later procedures. The full list of CIED procedure codes for implantable pulse generator (IPG), implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker (CRT-P) and cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator (CRT-D) index procedures can be found in Supplementary Table S1. Patients were excluded if the type of device could not be determined, or if there was a record of a separate major cardiac procedure on the same date (Supplementary Table S2), or the CIED procedure was not conducted in certain places of service (inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, ambulatory surgical centre), or if the follow-up period was <1 day.

Outcomes and measures

To best capture the presence of risk factors prior to the procedure, the baseline period was defined as all health plan data for the patient prior to the index CIED procedure date. Baseline patient characteristics included age, procedure type, renal insufficiency, immunocompromised, prior CIED procedure, and prior CIED infection history. Baseline comorbidities were defined as ≥1 corresponding diagnosis code (ICD-9-CM), in any position on a medical claim (Supplementary Table S3). Immunocompromised status was supplemented with relevant medication information within 30 days prior to index date. The follow-up period began the day after an outpatient index CIED procedure and the day after discharge for an inpatient procedure. The follow-up ended with the first occurrence of any of the following: 12-months after the start date of follow-up, end of insurance coverage, death, new CIED procedure, or date of major CIED infection.

In order to select the most clinically meaningful events, major CIED infection was chosen as the primary outcome in this study. CIED infection was identified when either of the following conditions were met: (a) ≥1 claim with ICD-9-CM code 996.61 (infection due to cardiac device, implant, and graft) in any position on the claim; (b) ≥1 claim with a CIED implant, revision or removal code, in any position, and ≥1 claim with an infection diagnosis code (CIED-specific or bloodstream/non-CIED specific), in any position, on the same date of service. Major CIED infections (infection associated with system removal, invasive procedure without system removal, or death attributable to infection) were identified through diagnosis and procedure codes indicating a CIED infection associated with or without system removal (Supplementary Table S4), or death attributable to infection (Supplementary Table S5).

Index characteristics included age, device type (IPG, ICD, CRT-P, and CRT-D), and procedure type (implant, replacement, upgrade, and revision). History of CIED infection was identified as a suspected risk factor and included in the analysis as a potential predictor, above and beyond the original PADIT risk score factors.

Data sets

We chose to partition the data into two independent data sets so that the first data set could be utilized for modelling of the PADIT score as a predictor of major CIED infection, and so the second data set would be available for independent modelling should revisions to the PADIT score be deemed appropriate. The cohort data set was partitioned into Data Set A (60% of the full data set) and Data Set B (40%) consistent with the prospectively defined analysis plan. Patients were randomly assigned to either group, with randomization stratified by PADIT score and history of CIED infection at time of the patient’s index procedure. If a patient had multiple procedures, then all procedures for that patient were assigned to the same data set.

Frailty model

A frailty model was chosen as a robust model to account for multiple procedures per patient, to validate the known PADIT infection risk score factors, and to allow for potential unknown risk factors. A frailty model was fit in Data Set A, excluding index procedures in which the patient had a history of CIED infection at the time of the procedure since such procedures were excluded in the PADIT study. The model included PADIT risk score at the time of the procedure as the only independent variable, as well as a random frailty effect. A frailty model was also fit including procedures in which the patient had a history of CIED infection, and that model included ‘Prior CIED infection’ as an additional independent variable. The software package S + 8.2 was used with the frailty option utilizing the AIC (Akaike Information Criteria) method.

Annualized rates of cardiac implantable electronic device procedures

Since no changes or transformations were applied to the PADIT risk score following analysis of Data Set A, both Data Set A and Data Set B were pooled to generate annualized rates of CIED procedures resulting in major CIED infection by PADIT risk score and history of CIED infection. If the first procedure per subject during the study period was not a de novo procedure (e.g. replacements, revisions, and upgrades), it could not be determined how many prior procedures (a component of the PADIT risk score) those patients had undergone. Thus, it is possible the PADIT risk score for these procedures was underestimated; as such, the calculation of annualized rates of procedures resulting in major CIED infection was repeated with these procedures removed from the analysis.

Major cardiac implantable electronic device infection incidence rates

Generation of incidence rates was performed with one procedure per patient using the pooled data set; however, to mitigate the possible underestimation of the PADIT risk score among some procedures and allow for a more heterogenous distribution of PADIT risk scores represented, the second procedure per patient was used for patients with more than one procedure. The analysis was repeated excluding non-de novo first procedures (refers to the earliest procedure found in the claims data and describes that this was not a de novo procedure, indicating that there is uncertainty about the total number of prior procedures) per patient, as for these procedures the number of prior procedures (a PADIT component) the patient had experienced at the time was not known.

Concordance

To determine a measure of concordance that the PADIT risk score combined with history of CIED infection offers, the full data set was restricted to one procedure per subject. If a subject had more than one procedure, the second procedure was chosen to ensure that the number of prior procedures (one or more than one) was known for accurate calculation of the PADIT risk score. A Cox proportional hazards model was fit, and Harrell’s C-statistic was determined.

Results

Data sets

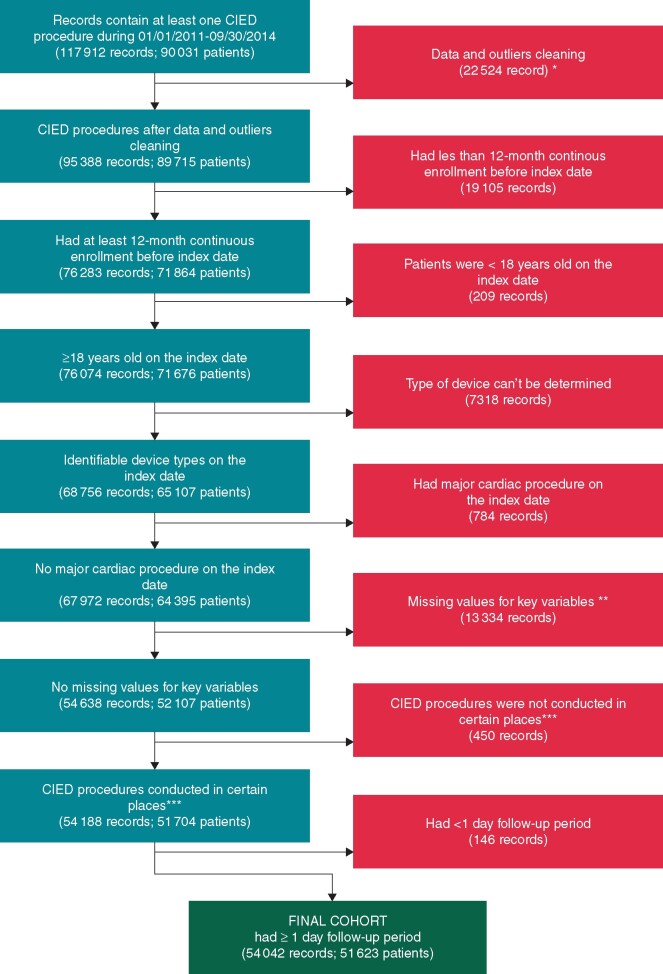

There were 54 042 index CIED procedures among 51 623 patients in the full data set (Figure 1), with 574 total infections. These procedures were randomized at the patient level into Data Set A consisting of 32 464 index procedures among 30 974 patients with 369 infections, and Data Set B consisting of 21 578 index procedures among 20 649 patients with 205 infections. Patients in Data Sets A and B were similar with regards to the individual components of the PADIT risk score and prior CIED infection (Table 2) . Similar to the PADIT study, the most common index procedure was de novo pacemaker implant or generator replacement (51.5% in Data Set A vs. 48.9% in the PADIT study). Approximately 59.2% of procedures were a de novo procedure; however, multiple procedures per patient were incorporated into the modelling.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for initial or replacement CIED procedural group classification. Medical history considered was defined as that occurring within a minimum of 12 months prior to the index CIED procedure. De novo implants or generator replacements of pacemakers, ICDs, or CRT devices were assigned to the Pacemaker, ICD, and CRT categories, respectively, in the determination of the PADIT score. *Data and outliers cleaning process: excluded patients had more than 10 index procedures/dates; excluded records which index procedure is removal only; if records had multiple index procedures dates with same claims ID, they were only considered as one index procedure; for duplicated or overlapped records, they were combined and considered as one index procedure; if patients had multiple index procedures during the same inpatient admission, only the last one was considered, and so on. **If records with missing value for key variables in raw data, for example, place of service variable. ***Place of service in inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or ambulatory surgical centre. CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy device; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator.

Table 2.

PADIT risk score component distribution in Data Sets A, B, and PADIT study

| PADIT risk score component | PADIT risk score points | Data Set A (N = 32 464) (%) | Data Set B (N = 21 578) (%) | PADIT study (N = 19 559) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 2 | 4228 (13.0) | 2777 (12.9) | 3096 (15.8) |

| 60–69 | 1 | 6271 (19.3) | 4173 (19.3) | 4244 (21.7) |

| ≥70 | 0 | 21 965 (67.6) | 14 628 (67.8) | 12 219 (62.5) |

| Procedure type | ||||

| Pacemaker | 0 | 16 729 (51.5) | 11 127 (51.6) | 48.9 |

| ICD | 2 | 6625 (20.4) | 4455 (20.7) | 21.6 |

| CRT | 4 | 3704 (11.4) | 2491 (11.5) | 16.2 |

| Revision/upgrade | 4 | 5406 (16.7) | 3505 (16.2) | 15.3 |

| Renal insufficiency | 1 | 9043 (27.9) | 6100 (28.3) | 16.7 |

| Immunocompromised | 3 | 2019 (6.2) | 1324 (6.1) | 1.6 |

| Prior procedure(s)a | ||||

| None | 0 | 20 017 (61.7) | 13 349 (61.9) | 9056 (46.3) |

| One | 1 | 11 880 (36.6) | 7866 (36.5) | 7851 (40.1) |

| Two or more | 3 | 567 (1.8) | 363 (1.7) | 2652 (13.6) |

| History of CIED infection | N/A | 368 (1.1) | 217 (1.0) | 0 |

Prior procedure(s) is inclusive of all procedures including de novo implant.

CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PADIT, Prevention of Arrhythmia Device Infection Trial.

Frailty model

Frailty models were fit using Data Set A. The first model excluded index procedures in which the patient had a history of CIED infection. The PADIT risk score was found to be highly significant (P < 0.0001), with an estimated hazard ratio (HR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) of 1.28 (95% CI 1.22, 1.33) (Table 3); thus, the relative risk of a major CIED infection increased by 28% for each one unit increase in PADIT risk score. A second frailty model including procedures in which the patient had a history of CIED infection was fit; the HR and 95% CI for the PADIT risk score was 1.26 (95% CI 1.21–1.32) . While the relative number of procedures with prior CIED infection was small, the corresponding hazard ratio for history of CIED infection was 5.66 (95% CI 4.03–7.93). Both the PADIT risk score and history of CIED infection were highly significant in this second analysis, so after accounting for history of CIED infection, the PADIT risk score still served as a predictor of increased infection risk. The random effects of the frailty estimates did not identify other factors that were predictive beyond the PADIT infection risk score variables and the history of CIED infection.

Table 3.

Model results

| Data set A cohort | Predictors | Estimated HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients with no history of CIED infection | PADIT score | 1.28 (1.22, 1.33) | <0.0001 |

| Frailty effect | N/A | 0.23 | |

| All Patients | PADIT score | 1.26 (1.21, 1.32) | <0.0001 |

| Prior CIED Infection | 5.66 (4.03, 7.93) | <0.0001 | |

| Frailty effect | N/A | 0.15 |

CI, confidence interval; CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; HR, hazard ratio; PADIT, Prevention of Arrhythmia Device Infection Trial.

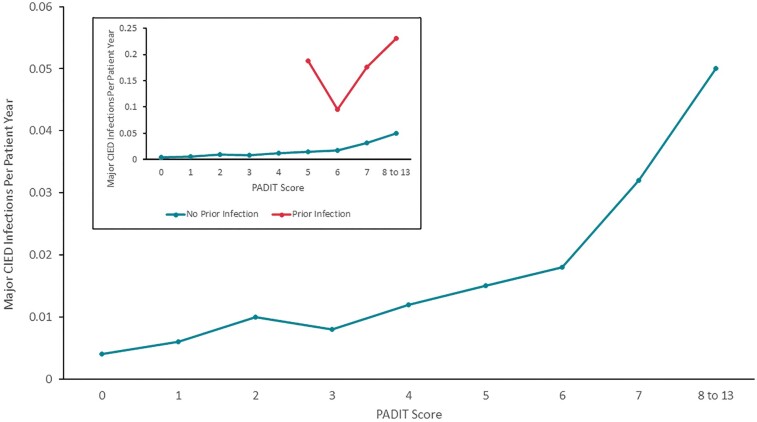

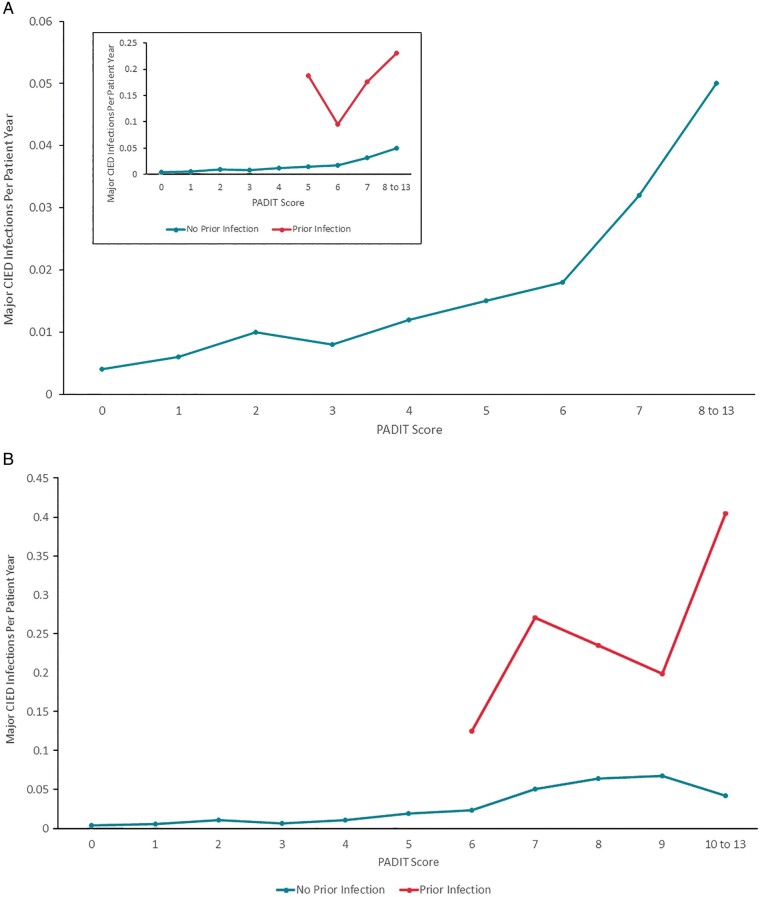

Predictive value of PADIT risk score

Because the number of index procedures in which the patient had a prior CIED infection made up only 1% of the Data Set A procedures, we generated the annualized rate of procedures followed by a major CIED infection (within 12 months) by PADIT risk score, separately for procedures with and without a history of CIED infection (Figure 2A). Only PADIT risk score/groups in which there were at least 20 procedures were plotted, and groups with scores of 10 or more were combined. A positive monotonic relationship between PADIT risk score and annualized rate of index procedures followed by major CIED infection was generally observed among procedures in which the patient did not have a history of CIED infection. For the smaller collection of procedures in which the patient did have a history of CIED infection, the pattern was less consistent, but still trended upward with PADIT risk scores.

Figure 2.

(A) Annualized rate of major CIED infections by PADIT score. Blue line represents a population similar to the original PADIT risk score analysis (no prior CIED infections) and the orange line represents patients with prior CIED infections. The insert depicts the original PADIT risk score analysis scaled up for clarity. Rates unadjusted for patient, as multiple index procedures per patient were included; only one major CIED infection was allowed per index procedure. (B) Annualized Rate of Major CIED Infections by PADIT score excluding non-de novo first procedures. In the inset, the blue line represents a population similar to the original PADIT risk score analysis (no prior CIED infections) and the orange line represents patients with prior CIED infections. The main figure depicts the original PADIT risk score analysis scaled up for clarity. Non-de novo first procedures were excluded as the number of prior procedures was uncertain owing to lack of this component of the patient history; this analysis was restricted to index procedures for which sufficient patient history was available to determine a PADIT score. The sample size with PADIT score 10–13 was combined due to low numbers. CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; PADIT, Prevention of Arrhythmia Device Infection Trial.

This analysis was repeated excluding first procedures per patient in which the procedure was a revision/replacement/upgrade, for while it was certain the patient had at least one prior procedure, it could not be determined if the number of prior procedures was one or at least two. The exclusion of 18 257 index procedures still left 35 785 procedures to evaluate. The earlier trend noted among procedures in which the patient did not have a prior CIED infection remained (Figure 2B).

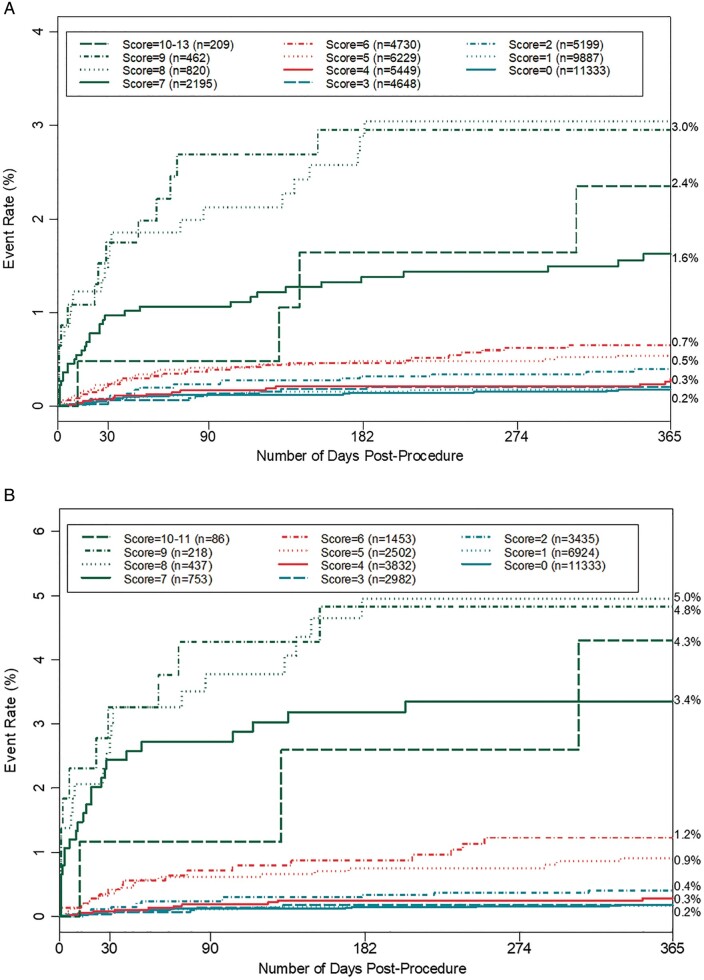

This method was used to further generate incidence rates of index procedures followed by major CIED infections using the full cohort (Figure 3A) and the reduced cohort excluding non-de novo first procedures per patient (Figure 3B), also showing an increased rate of infection incidence with PADIT risk score. In both cases, procedures in which the patient had a prior history of CIED infection were excluded. The incidence rates for higher PADIT risk scores were more elevated in the analysis of the reduced cohort.

Figure 3.

(A) Incidence rates of major CIED infection by PADIT score excluding procedures with history of CIED infection. One index procedure was allowed per patient; for patients with more than one procedure the second procedure was used to mitigate the possible underestimation of the PADIT score due to incomplete patient history. (B) Incidence rates of major CIED infection by PADIT score excluding non-de novo first procedures and procedures in patients with prior CIED Infection. Non-de novo first procedures were excluded as the number of prior procedures was uncertain owing to a lack of full patient history; this analysis was restricted to index procedures for which sufficient patient history was available to determine a PADIT score. CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; PADIT, Prevention of Arrhythmia Device Infection Trial.

Concordance

Because the modelling did not result in altering the PADIT risk score, the full data set (Data Sets A and B) was combined and restricted to one procedure per subject to assess concordance of PADIT score and history of CIED infection using a Cox proportional hazards model. The resulting Harrell’s C-statistic was 0.76.

Discussion

In the current analysis we validated the predictive value of the PADIT risk score using U.S. healthcare claims data, and confirmed that it predicts increased CIED infection risk, identifying higher risk patients who may derive benefit from targeted interventions to reduce infection risk. Our validation confirms that the PADIT risk score identifies an accurate set of strong predictive risk factors for CIED infection. The risk of a major CIED infection increased by 28% for each one unit increase in PADIT risk score in a linear fashion. In this analysis, we also accounted for history of CIED infection, a variable previously not included in the PADIT risk score model. While the PADIT risk score still served as a predictor of increased infection risk, inclusion of prior CIED infection history conferred additional predictive value to the risk score.

CIED infection is a major complication associated with significant morbidity, mortality and costs. Although the health-economic and financial cost of infection is high, we should bear in mind that the greatest impact of infection is borne by the patient, as 3-year mortality is up to 50%.3–5,12 In view of this, infection risk is an important consideration in patient selection for CIED therapy and predictive risk scores are likely to be helpful to physicians and patients in shared decision making about device therapy and peri-operative management. In order to balance the benefit of additional measures with the costs of any proposed interventions, accurate estimation of risk is essential. The PADIT risk score7 is a novel CIED infection risk prediction score that identifies significant predictors of device infection (age, procedure type, renal insufficiency, immunocompromised, and prior CIED procedure), which are largely consistent with observations from a recent meta-analysis9 and Danish device cohort registry study13 evaluating risk factors for CIED infection. A further validation of the predictive utility of the PADIT risk score in an independent data set was determined to be warranted to confer generalizability and validity.

Several reports in the literature have examined risk factors for CIED infection, however, the majority of these have relatively small sample sizes and low-infection rates9 prompting the need for studies with more representative sample sizes.14 The sample size and infection rates in the PADIT trial provide adequate power for such analyses to identify a smaller but more predictive set of risk factors. Heterogeneity among studies that previously attempted to identify predictors of infection resulted in a large discordant list of potential risk factors; however, a recent meta-analysis by Polyzos et al., synthesized these findings to identify a smaller set of risk factors that proved valid given a higher quality standard of evidence.9 Consistent with the meta-analysis by Polyzos et al., procedure type, renal insufficiency, immuno-compromised, and previous procedures were identified as significant predictors of infection in the PADIT study. Interestingly, additional patient-specific variables associated with infection that were identified in the meta-analysis were not identified in the PADIT risk score, such as diabetes, which may have been assumed to be a risk factor based on clinically plausible mechanisms and not based on direct evidence of infection causality.

In this analysis, index CIED procedures identified in the claims data set were stratified by PADIT risk score into two data sets. Data Set A was found to be concordant with the PADIT risk score and these modelling analyses indicated that predictive capability of the PADIT risk score was highly significant, as was history of CIED infection. The Frailty model showed that a one unit increase in the PADIT risk score predicts higher infection risk (28%) in the claims data set. Prior CIED infection was associated with a dramatic increase in overall infection rate (Figure 2A), with strong additional predictive value after adjusting for PADIT risk score. Thus, we recommend accounting for history of CIED infection as an independent variable supplementary to the PADIT risk score.

Because the number of index procedures in which the patient had a prior CIED infection made up only 1% of the Data Set A procedures, we generated the annualized rate of procedures followed by a major CIED infection (within 12 months) by PADIT risk score, separately for procedures with and without a history of CIED infection. A positive monotonic relationship between PADIT risk score and annualized rate of index procedures followed by major CIED infection was observed among procedures where the patient did not have a history of CIED infection.

Device infection risk estimates can be useful for understanding the benefit of conventional antibiotic therapy vs. prophylactic infection prevention strategies aimed at reducing the risk of CIED infection. Preventive measures were recently described in a consensus document.15 However, accurate estimation of risk is central to ensuring that enhanced infection prevention measures are directed towards the right patients. Recently, the World-wide Randomized Antibiotic Envelope Infection Prevention Trial (WRAP-IT)16 found a 40% relative risk reduction in major CIED infection with the use of the absorbable antibacterial envelope (TYRXTM, Medtronic, Mounds View, MI, USA). This effect was driven by a significant 61% reduction in pocket infections. The previously described consensus document provided a ‘green heart’ recommendation for the antibiotic envelope in high-risk situations.15 It is reasonable to consider using the PADIT risk score to identify procedures of high risk in which the envelope should be considered. Incorporation of the PADIT risk score with the inclusion of prior CIED infection in study inclusion criteria of future device infection prevention trials can also provide estimates of event rates and sample sizes needed to detect a difference in relative risk reduction between control and experimental study arms.

Limitations

The PADIT risk score was based on a large prospective data set subject to inclusion/exclusion criteria, and this validation effort was based on a retrospective analysis of claims data so there may have been differences in the population studied. However, since these results are consistent with the PADIT results, this may represent a corroboration of clinical trial results in real-world data. In addition, the purpose of claims databases is primarily for billing rather than clinical determinations, it is possible that the coding may be incorrect or not fully representative of clinical circumstances. However, the use of claims data sets for research purposes is a well-established practice in the literature,17 and the overall concordance of these results with the PADIT findings suggests that the data are generally appropriate for the purposes of this analysis. Although healthcare claims data sets are widely used to address specific research questions, we acknowledge that international classification of disease diagnosis codes could be augmented by linkage with electronic health records and laboratory databases to provide more granular detail concerning continuous clinical parameters, which may be subject to high variability (i.e. estimated glomerular filtration rate). The study follow-up period was limited to 12 months and is not representative of long-term infection risk, however, this length of follow-up is consistent with recent clinical trials.7,16 It is possible that there are additional predictors of infection, for example specific procedural characteristics that are important and were not included in this analysis. Finally, the definition of major CIED infection in this study was derived from the primary endpoint of the WRAP-IT trial and may have differed from previous definitions of CIED infection; however, CIED infections are highly consequential and easily identifiable thus robust across minor variations in definition.

Conclusion

In the largest external validation of a CIED risk score, the PADIT risk score predicts increased CIED infection risk, identifying higher risk patients that can benefit from targeted interventions to reduce the risk of CIED infection. Prior CIED infection brings additional predictive value to the PADIT score.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Elizabeth L. Eby for assistance with planning and design of the analysis.

Conflict of interest: F.Z.A. reports grants from Medtronic, outside the submitted work and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Servier and Vifor; C. B.-L., H.B., C.C. report personal fees from Medtronic, outside the submitted work; C.E. reports grants and personal fees from Medtronic and Boston Scientific, grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Abbott, and Atricure, outside the submitted work; A.G. reports personal fees from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Berlin-Chemie, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Biotronik, Sanofi, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Omeicos, and grants from Josef-Freitag Stiftung and aDeutsche Herzstiftung e. V., outside the submitted work; A.J.S. reports grants and personal fees from Medtronic, and personal fees from Boston Scientific and Abbot (St. Jude), outside the submitted work; C.J.L. reports grants and personal fees from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbot (St. Jude), and Philips Medical, outside the submitted work; J.B.J. reports personal fees from Medtronic, Biotronik, and Merit Medical, outside the submitted work; F.P. reports grants from Medtronic, outside the submitted work; K.G.T. reports personal fees from Medtronic, AliveCor, and Boston Scientific, outside the submitted work; R.H., L.S, Y.X., S.S., and D.L. report personal fees from Medtronic, outside the submitted work; Dr Krahn reports personal fees from Medtronic, outside the submitted work.

Data availability

Data will be made available for review.

References

- 1.Greenspon AJ, Patel JD, Lau E, Ochoa JA, Frisch DR, Ho RT. et al. 16-year trends in the infection burden for pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in the United States 1993 to 2008. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1001–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bongiorni MG, Kennergren C, Butter C, Deharo JC, Kutarski A, Rinaldi CA, et al. The European Lead Extraction ConTRolled (ELECTRa) study: a European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) Registry of Transvenous Lead Extraction Outcomes. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2995–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sohail MR, Henrikson CA, Braid-Forbes MJ, Forbes KF, Lerner DJ.. Mortality and cost associated with cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1821–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed FZ, Fullwood C, Zaman M, Qamruddin A, Cunnington C, Mamas MA. et al. Cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infections are expensive and associated with prolonged hospitalisation: UK Retrospective Observational Study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0206611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Essebag V, Verma A, Healey JS, Krahn AD, Kalfon E, Coutu B. et al. Clinically significant pocket hematoma increases long-term risk of device infection: bruise control infection study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1300–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eby EL, Bengtson LGS, Johnson MP, Burton ML, Hinnenthal J.. Economic impact of cardiac implantable electronic device infections: cost analysis at one year in a large United States health insurer. J Med Econ 2020;23:698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birnie DH, Wang J, Alings M, Philippon F, Parkash R, Manlucu J. et al. Risk factors for infections involving cardiac implanted electronic devices. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2845–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krahn AD, Longtin Y, Philippon F, Birnie DH, Manlucu J, Angaran P. et al. Prevention of Arrhythmia Device Infection Trial: the PADIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:3098–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polyzos KA, Konstantelias AA, Falagas ME.. Risk factors for cardiac implantable electronic device infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2015;17:767–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Optum’s de-identifed Clinformatics® Data Mart Database (2007-2018).

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance Regarding Methods for De-identification of Protected Health Information in Accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/special-topics/de-identification/index.html. (17 Mar 2020, date last accessed).

- 12.Sohail MR, Henrikson CA, Jo Braid-Forbes M, Forbes KF, Lerner DJ.. Increased long-term mortality in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2015;38:231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen T, Jorgensen OD, Nielsen JC, Thogersen AM, Philbert BT, Johansen JB.. Incidence of device-related infection in 97 750 patients: clinical data from the complete Danish device-cohort (1982-2018). Eur Heart J 2019;40:1862–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baddour LM, Epstein AE, Erickson CC, Knight BP, Levison ME, Lockhart PB, et al. Update on cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections and their management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;121:458–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blomström-Lundqvist C, Traykov V, Erba P A, Burri H, Nielsen J C, Bongiorni M Get al. . European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus document on how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections—endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Europace2020;22:515–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarakji KG, Mittal S, Kennergren C, Corey R, Poole JE, Schloss E. et al. Antibacterial envelope to prevent cardiac implantable device infection. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burton B, Jesilow P.. How healthcare studies use claims data. TOHSP J 2011;4:26–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available for review.