Abstract

Background

Serious illness is often characterised by physical/psychological problems, family support needs, and high healthcare resource use. Hospital‐based specialist palliative care (HSPC) has developed to assist in better meeting the needs of patients and their families and potentially reducing hospital care expenditure. There is a need for clarity on the effectiveness and optimal models of HSPC, given that most people still die in hospital and also to allocate scarce resources judiciously.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of HSPC compared to usual care for adults with advanced illness (hereafter patients) and their unpaid caregivers/families.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, CDSR, DARE and HTA database via the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE; Embase; CINAHL; PsycINFO; CareSearch; National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and two trial registers to August 2019, together with checking of reference lists and relevant systematic reviews, citation searching and contact with experts to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the impact of HSPC on outcomes for patients or their unpaid caregivers/families, or both. HSPC was defined as specialist palliative care delivered by a palliative care team that is based in a hospital providing holistic care, co‐ordination by a multidisciplinary team, and collaboration between HSPC providers and generalists. HSPC was provided to patients while they were admitted as inpatients to acute care hospitals, outpatients or patients receiving care from hospital outreach teams at home. The comparator was usual care, defined as inpatient or outpatient hospital care without specialist palliative care input at the point of entry into the study, community care or hospice care provided outside of the hospital setting.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We assessed risk of bias and extracted data. To account for use of different scales across studies, we calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous data. We used an inverse variance random‐effects model. For binary data, we calculated odds ratio (ORs) with 95% CIs. We assessed the evidence using GRADE and created a 'Summary of findings' table.

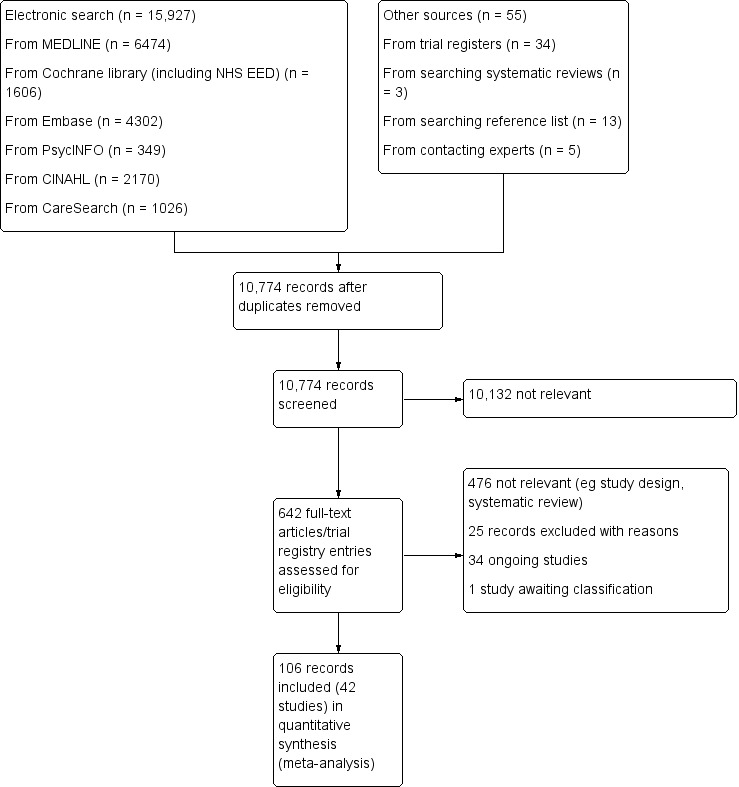

Our primary outcomes were patient health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) and symptom burden (a collection of two or more symptoms). Key secondary outcomes were pain, depression, satisfaction with care, achieving preferred place of death, mortality/survival, unpaid caregiver burden, and cost‐effectiveness. Qualitative data was analysed where available.

Main results

We identified 42 RCTs involving 7779 participants (6678 patients and 1101 caregivers/family members). Twenty‐one studies were with cancer populations, 14 were with non‐cancer populations (of which six were with heart failure patients), and seven with mixed cancer and non‐cancer populations (mixed diagnoses).

HSPC was offered in different ways and included the following models: ward‐based, inpatient consult, outpatient, hospital‐at‐home or hospital outreach, and service provision across multiple settings which included hospital. For our main analyses, we pooled data from studies reporting adjusted endpoint values. Forty studies had a high risk of bias in at least one domain.

Compared with usual care, HSPC improved patient HRQoL with a small effect size of 0.26 SMD over usual care (95% CI 0.15 to 0.37; I2 = 3%, 10 studies, 1344 participants, low‐quality evidence, higher scores indicate better patient HRQoL). HSPC also improved other person‐centred outcomes. It reduced patient symptom burden with a small effect size of ‐0.26 SMD over usual care (95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.12; I2 = 0%, 6 studies, 761 participants, very low‐quality evidence, lower scores indicate lower symptom burden). HSPC improved patient satisfaction with care with a small effect size of 0.36 SMD over usual care (95% CI 0.41 to 0.57; I2 = 0%, 2 studies, 337 participants, low‐quality evidence, higher scores indicate better patient satisfaction with care). Using home death as a proxy measure for achieving patient's preferred place of death, patients were more likely to die at home with HSPC compared to usual care (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.23 to 2.16; I2 = 0%, 7 studies, 861 participants, low‐quality evidence). Data on pain (4 studies, 525 participants) showed no evidence of a difference between HSPC and usual care (SMD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.33 to 0.01; I2 = 0%, very low‐quality evidence). Eight studies (N = 1252 participants) reported on adverse events and very low‐quality evidence did not demonstrate an effect of HSPC on serious harms. Two studies (170 participants) presented data on caregiver burden and both found no evidence of effect of HSPC (very low‐quality evidence). We included 13 economic studies (2103 participants). Overall, the evidence on cost‐effectiveness of HSPC compared to usual care was inconsistent among the four full economic studies. Other studies that used only partial economic analysis and those that presented more limited resource use and cost information also had inconsistent results (very low‐quality evidence).

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence assessed using GRADE was very low to low, downgraded due to a high risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision.

Authors' conclusions

Very low‐ to low‐quality evidence suggests that when compared to usual care, HSPC may offer small benefits for several person‐centred outcomes including patient HRQoL, symptom burden and patient satisfaction with care, while also increasing the chances of patients dying in their preferred place (measured by home death). While we found no evidence that HSPC causes serious harms, the evidence was insufficient to draw strong conclusions. Although these are only small effect sizes, they may be clinically relevant at an advanced stage of disease with limited prognosis, and are person‐centred outcomes important to many patients and families. More well conducted studies are needed to study populations with non‐malignant diseases and mixed diagnoses, ward‐based models of HSPC, 24 hours access (out‐of‐hours care) as part of HSPC, pain, achieving patient preferred place of care, patient satisfaction with care, caregiver outcomes (satisfaction with care, burden, depression, anxiety, grief, quality of life), and cost‐effectiveness of HSPC. In addition, research is needed to provide validated person‐centred outcomes to be used across studies and populations.

Plain language summary

Effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of hospital‐based specialist palliative care (HSPC) for adults with advanced illness and their unpaid caregivers

Review question

How effective is hospital‐based specialist palliative care for adults with a terminal illness and their unpaid caregivers, and is it cost‐effective?

Why is this question important?

Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life of people who have a terminal illness (a disease that cannot be cured and is likely to lead to death). It seeks to help patients, their unpaid caregivers and families manage symptoms that cause distress (for example, pain) and to meet patients’ and unpaid caregivers’ needs for psychological, social and spiritual support. Palliative care is known as an ‘holistic’ approach, because it considers the ‘whole’ person and their support network – not just the illness and its symptoms. It usually involves a team of people that can include physicians, nurses, pharmacists, other allied health professionals, social workers, chaplains or volunteers.

A growing number of hospitals are setting up specialist palliative care services (known as hospital‐based specialist palliative care (HSPC)). HSPC can be provided:

‐ either in the hospital itself – for inpatients or outpatients;

‐ or as 'hospital‐at‐home' – which means that the hospital team visits patients in the community;

‐ or across multiple settings (for example, hospital and home).

To find out whether HSPC benefits patients and their unpaid caregivers, and how cost‐effective it is, we reviewed the evidence from research.

How did we identify and evaluate the evidence?

First, we searched for all relevant studies in the medical literature. We specifically looked for:

‐ randomised controlled studies: these are studies where people are randomly divided into different treatment groups. This type of study provides the most robust evidence about the effects of a treatment;

‐ studies that compared HSPC to either hospital care without specialist palliative care; care received in the community; or hospice care outside hospital.

We compared the results, and summarised the evidence from all the studies. Finally, we assessed how certain the evidence was. We considered factors such as the way studies were conducted, study sizes, and consistency of findings across studies. Based on our assessments, we categorised the evidence as being of very low, low, moderate or high certainty.

What did we find?

We found 42 studies that involved a total of 6678 patients and 1101 caregivers or family members. The patients were suffering from: cancer (21 studies); an advanced illness that was not cancer (14 studies); and a combination of cancer and non‐cancer (mixed) diagnoses (7 studies). Patients in six of the 14 non‐cancer studies had heart failure. Almost half (19) of the studies were set in the USA. Thirteen studies reported information on the costs of HSPC.

The evidence from the studies we found suggests that, when compared to usual care:

‐ HSPC may slightly improve patients’ health‐related quality of life, their overall symptom burden and their satisfaction with care;

‐ HSPC may increase the chances of people dying in their preferred place of death.

It is unclear what the effects of HSPC are on pain, caregivers’ burden, or unwanted events. This is because the evidence we found was not robust (very low‐certainty evidence). Similarly, because the evidence relating to costs was of very low certainty, it is unclear how cost‐effective HSPC is.

What does this mean?

When compared with usual care, HSPC may slightly improve a patient’s quality of life, symptom burden and their satisfaction with care. It may also increase their chances of dying at home. However, future research is likely to change these findings, since they are based on low‐certainty evidence. We need further studies to evaluate the effect of HSPC on other outcomes, such as pain, caregivers’ burden, unwanted events and cost‐effectiveness.

How‐up‐to date is this review?

The evidence in this Cochrane Review is current to August 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Hospital‐based specialist palliative care compared to usual care for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers/families.

| Hospital‐based specialist palliative care compared to usual care for adults with advanced illness and their unpaid caregivers/families | |||||

| Patient or population: adults with advanced illness and their unpaid caregivers/families Setting: hospital and home Intervention: hospital‐based specialist palliative care Comparison: usual care | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk with hospital‐based specialist palliative care | ||||

| Patient health‐related quality of life (HRQoL)i, SD units (higher scores indicate better quality of life) Follow‐up: range two weeks after hospitalisation to 13 months | Mean (SD) ranging from ‐45.4 (26.83) to 131.14 (26.62) | SMD 0.26 SDs higher (0.15 higher to 0.37 higher) | ‐ | 1344 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa |

|

Patient symptom burden assessed with generalised measuresii, SD units (lower scores indicate lower symptom burden) Follow‐up: range two weeks after hospitalisation to 13 months |

Mean (SD) ranging from ‐19.3 (4.2) to 268.59 (201.65) | SMD 0.26 SDs lower (0.41 lower to 0.12 lower) | ‐ | 761 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b |

| Patient satisfaction with careiii, SD units (higher scores indicate better patient satisfaction) Follow‐up: range 3 months to 6 months | Mean (SD) ranging from 6.4 (1.1) to 68.37 (9.03) | SMD 0.36 SDs higher (0.41 higher to 0.57 higher) |

‐ | 337 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa |

|

Achieving patient preferred place of death (measured by number of patients with home death) Follow‐up: range 1 month to 13 months |

462 per 1000 | 583 per 1000 (513 to 649) |

OR 1.63 higher (1.23 higher to 2.16 higher) |

861 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa |

| Painiv, SD units (lower scores indicate less pain) Follow‐up: range 8 weeks to 6 months | Mean (SD) ranging from 2.2 (3.7) to 28.19 (32.81) | SMD 0.16 SDs lower (0.33 lower to 0.01 higher) | ‐ | 525 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b |

| Unpaid caregiver burdenv Follow‐up: 6 months | Only two studies reported adjusted endpoint values but we could not pool them in a meta‐analysis. They both found no between‐group difference between HSPC and usual care | ‐ | 170 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,c | |

| Cost and cost‐effectiveness | Of 13 studies reporting costs of HSPC, nine studies found no difference between HSPC and usual care and two studies favoured HSPC over usual care. The difference in cost was unclear in one study, while another study reported mixed findings with lower cost of hospitalisation in favour of HSPC but no difference in the cost of emergency room visit. Four studies with full economic analysis were inconclusive on the cost‐effectiveness of HSPC. |

‐ | 2103 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk Ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference i. Assessed with the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ‐C30), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy ‐ Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT‐BMT), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy ‐ General Measure (FACT‐G), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Lung scale (FACT‐L), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness therapy for Palliative Care (FACIT‐Pal), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy ‐ Spiritual Well‐being Scale (FACIT‐Sp), McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (McGill QoL questionnaire) and Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHF questionnaire). ii. Assessed with the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) or a modified form of it, severity subscale of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS), symptom impact subscale of the Quality of Life at End of life (QUAL‐E), Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSC ‐ Physical Symptoms Score) and lung cancer subscale of the FACT‐L. iii. Assessed with 16‐item Family Satisfaction with Care ‐ Patient Version (FAMCARE‐P16) and Modified City of Hope Patient Questionnaires ‐ Place of Care Environment Scale (MCOHPQ ‐ Place of Care Environment Scale). iv. Assessed with pain item of EORTC QLQ‐C30 and Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). v. Assessed with Montgomery‐Borgatta Caregiver Burden Scale and Zarit Burden Inventory | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

a We downgraded by 2 levels for very serious study limitations due to a high risk of bias in studies.

b We downgraded by 1 level due to inconsistency between our main meta‐analysis and sensitivity analyses.

c We downgraded by 1 level for imprecision due to the small number of participants.

d We downgraded by 1 level for inconsistency because the results were inconsistent across studies.

Background

The global burden of disease has increased, and this change is placing considerable strain on healthcare systems internationally (Bloom 2016). Most adults develop one or more chronic illnesses with which they may live for many years before they die. For a minority of patients with serious illness, the time following diagnosis is characterised by a stable period of relatively good functional and cognitive performance, followed by a predictable and short period of functional and clinical decline. The time following diagnosis may also be characterised by months to years of physical and psychological symptom distress, progressive functional dependence and frailty, considerable family support needs and high healthcare resource use (Evans 2019; Prince 2015). In addition to increased clinical complexity, the rise of ageing populations has led to considerable healthcare costs globally. This has occurred despite efforts to reduce acute hospital care expenditure in many high‐income countries, including, for example, in the USA (Kashihara 2012), and the UK (Imison 2017; Lafond 2014), by shifting care from the hospital setting to primary care and the community.

It could be argued that increased staffing costs and the introduction or expansion of novel services in hospitals and the community, such as specialist palliative care, plays a role in this increased expenditure. Hospital‐based palliative care encompasses palliative care interventions that are delivered by specialist palliative care teams based in a hospital to patients with advanced (C‐TAC 2015), life‐limiting (Palliative Care Australia 2005), or life‐threatening illness (NCP 2013), which is likely to compromise their quality of life (WHOQOL Group 1995). The care is provided to the patient while they are admitted as inpatients to acute care hospitals, outpatients or patients receiving care from hospital outreach teams at home. Between 2000 and 2016, the prevalence of specialist palliative care in hospitals with 50 or more beds increased by 178% in USA, from 25% of hospitals in 2000 to 75% in 2016 (CAPC 2018). Furthermore, the growth of specialist palliative care in acute hospitals is likely to continue in the foreseeable future as most older adults (≥ 65 years old) die in hospitals (Broad 2013), most deaths in hospital occur due to terminal illness (Pivodic 2016), and also because deaths in institutional care persist into older stages of life, with one in five centenarians dying in hospital (Evans 2014). In the UK, it has been estimated that by 2040 about 160,000 more people yearly are likely to have palliative care needs, including pain management in chronic illnesses and end‐of‐life care in hospitals, hospices and at home (Etkind 2017). Cost‐effective commissioning of end‐of‐life resources has been highlighted as a priority (PHE 2017). Preliminary evidence shows that palliative care improves clinical outcomes and quality of care (Higginson 2003). Furthermore, palliative care, which includes bereavement care and preparatory grief work, has the potential to help unpaid caregivers access the care they need related to the death of a loved one (Grande 2017).

The numbers of inpatient hospital palliative care teams are increasing (CAPC 2018; Meier 2011). This is occurring in response to unmet palliative care needs of inpatients and their unpaid caregivers (Meier 2011), yet clarity around effective models of care are needed. This Cochrane Review will provide much‐needed clarity regarding the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of hospital‐based specialist palliative care. In the review, five different models of hospital‐based specialist palliative care were specified due to its evolving nature and also to make the findings more relevant to clinical practice. The models of hospital‐based specialist palliative care eligible are ward‐based models, inpatient consulting models, outpatient models, hospital‐at‐home or hospital outreach models (hereafter outreach model) and service provision across multiple settings which included hospital. The review findings will have the potential to aid the future development, funding and implementation of hospital‐based specialist palliative care. This may help transform services, which have mostly developed locally in culturally responsive ways in relation to local needs and populations (Higginson 2003; Kamal 2013). Therefore, the review will help deliver hospital‐based specialist palliative care services in the midst of increased ageing populations that present with complex clinical needs against a backdrop of fiscal constraint and increased healthcare utilisation.

Description of the condition

Population‐based estimates of palliative care have indicated which populations require this service (Murtagh 2014), including those with malignant neoplasms and non‐malignant and other health‐related conditions, specifically: heart disease, including cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, liver disease, respiratory disease, neurodegenerative disease (Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, multi‐system degeneration, progressive supranuclear ophthalmoplegia, Alzheimer's dementia and senility) and HIV/AIDS. Patients with any of these conditions and their unpaid caregivers were considered for inclusion in this review.

Description of the intervention

The intervention of interest is hospital‐based specialist palliative care (HSPC). In this review, hospital‐based specialist palliative care encompasses the following essential components:

care co‐ordinated by a multiprofessional or multidisciplinary team;

collaboration between specialist palliative care providers and generalist providers; and

holistic care (NCP 2013).

HSPC refers to care that is provided with the input of specialist palliative care providers to patients while they are admitted as inpatients to acute care hospitals, outpatients or patients receiving care from hospital outreach teams at home. The models of HSPC eligible for inclusion include ward‐based models, inpatient consulting models, outpatient models, hospital outreach models and service provision across multiple settings which included hospital. Ward‐based models encompassed care provision to patients and their families on a palliative care ward in hospital. Inpatient consulting models encompassed care provision to patients and their families by an inpatient consult team while they are admitted as inpatients to acute hospitals. Outpatient models comprised care provision to hospital outpatients and their families. Hospital‐at‐home or hospital outreach into the community involved care provision by hospital outreach teams in the patient's home as well as service provision across multiple settings including hospital.

The intervention aims to prevent or relieve physical, psychological, social and spiritual problems. It is provided to patients who have a malignant and/or non‐malignant condition who may or may not be at the end of their life (Dixon 2015). Recognising the importance of the informal unpaid caregiver, palliative care also aims to meet the psychological, social and spiritual needs of unpaid caregivers. (Grande 2017).

At the heart of palliative care is the belief that every person is unique, autonomous and that they have the right to continue to live and enjoy quality of life even though they are diagnosed with an advanced, life‐limiting or life‐threatening illness. Specialist palliative care is differentiated from generalist palliative care. Specialists are likely to have received higher specialist training in palliative care work and services focus mainly or exclusively on patients with palliative care needs; whereas for generalists, provision of palliative care is a component of their service provision (Dixon 2015) and they will not have received higher specialist traing in palliative care. Specialist care is mostly provided to patients with advanced, life‐limiting or life‐threatening illness who present with complex needs (NHS England 2016). Complexity, although sometimes difficult to define, involves clinical complexity and its interaction with the confidence or ability of the lead clinical team (generalists) to address the presenting need. Complexity may involve intertwined and multiple factors which may include related age, the serious nature of illness, social or familial backgrounds, and/or the nature of a symptom (e.g. the usualness or intractable nature of the symptom) (Palliative Care Australia 2005; Quill 2013).

Pre‐bereavement interventions are also specialist palliative care interventions administered to prevent or manage bereavement‐related physical, psychological, social and spiritual problems experienced by unpaid caregivers prior to the death of the patient (Aoun 2017; Breen 2014). We included specialist palliative care interventions involving pre‐bereavement interventions either to the unpaid caregiver alone or together with the patient.

How the intervention might work

Although positive outcomes, such as symptom reduction, improved quality of care and care co‐ordination, and reduced hospital costs, can result from hospital‐based specialist palliative care, qualitative methods such as interviews and empirical testing using randomised controlled trials have yet to definitively establish how hospital‐based specialist palliative care might work. Therefore, any descriptions of how hospital‐based specialist palliative care may work are speculative. That acknowledged, hospital‐based specialist palliative care may work with patients by the following:

directly improving symptoms (including physical and psychological symptoms, such as uncertainty and feelings of loss) through specialist interventions and holistic care (Temel 2010);

improving care quality by delivering or facilitating improved care co‐ordination and person‐centred holistic care (Daveson 2014; Pinnock 2011);

reducing futile medical interventions by mitigating against disease‐modifying priorities through optimal communication and shared decision‐making practice (Harris 2013

addressing holistic needs that span multimorbidity (Burge 2012); and

reducing unnecessary hospital costs through significant reduction in pharmaceutical, laboratory and intensive care unit costs (May 2014);

In addition, findings from published a systematic review (Harding 2012), RCTs (Allen 2008; Hudson 2005), and a before‐and‐after study (Lichtenthal 2011), indicated that the intervention may work for unpaid caregivers prior to the death of the patient through the following mechanisms:

emphasising the positive aspects of caregiving by providing relevant information, guidance and instruction. The intervention may also work by providing unpaid caregivers with individual support to see problems differently, draw out their optimism, helping them to plan and by providing them with access to expert information;

improving the unpaid caregiver’s understanding of their experiences and role to result in increased caregiving competencies and knowledge;

aiding their interpretation of their circumstance and normalising their emotional responses to caregiving demands;

enabling their involvement in care planning, where possible;

engaging both patients and unpaid caregivers in a life review within consultations which may work to reduce unpaid caregivers’ stress; and

ensuring timely assessment of needs, adaptive coping and access to needs‐based care through pre‐bereavement work.

The intervention may therefore also work via a preventive mechanism.

Why it is important to do this review

A previous systematic review by Higginson 2002 showed that hospital‐based palliative care improved clinical outcomes and quality of care and can reduce hospital costs. However, this review was small (nine studies) and only included cancer patients. A recent review in hospital, hospice or community settings by Gaertner 2017 showed that specialist palliative care led to improvement in quality of life with significant benefits for patients with cancer receiving specialist palliative care early. The results for pain and other outcomes were inconclusive. Another review by Haun 2017 showed that early palliative care interventions resulted in improved quality of life and lower symptom intensity compared with the control condition. Survival and levels of depression did not differ significantly between the early palliative care group and control group.

Since the publication of these systematic reviews, there have been at least six newly published RCTs on hospital‐based specialist palliative care and no review on its different models. In addition, the models of palliative care are continuously evolving. Recent UK government (DoH 2008), and commissioning guidance (NCPC 2012), have recommended that there ought to be delivery of a 24/7 palliative care service. However, the End of Life Care Audit 2016 showed that of the 142 acute NHS trusts in England participating, only 37% had specialist palliative care services available out‐of‐hours and this service varied with level of contact (telephone or on‐site visiting) and health professional involved (specialist nurse, junior doctor or consultant) (RCP 2016). The research priorities identified by the James Lind Alliance highlighted the need for research into identifying the core palliative care services needed and the best way of providing palliative care outside of working hours (JLA 2015). This Cochrane Review addresses these priorities. It is important that, following the Liverpool Care Pathway and Neuberger review, we examine the most effective methods and models of hospital‐based specialist palliative care in order to ensure that there is an evidence‐based approach to its delivery (Crown 2013).

A Cochrane Review has provided valuable evidence synthesis on the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of home palliative care services (Gomes 2013). However, there is no such available evidence for specialist palliative care in hospital inpatient, outpatient, outreach and services provided across multiple settings. Furthermore, the numbers of hospital‐based specialist palliative care teams are increasing (CAPC 2018; Meier 2011). This is occurring in response to unmet palliative needs of patients and their unpaid caregivers (Meier 2011), yet clarity regarding the effective components of the intervention is needed. This review may therefore assist with providing much‐needed solutions to problems, and clarity regarding the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of the component parts of hospital‐based specialist palliative care. In essence, the review may address some of the problems encountered by contemporary healthcare systems and services, service‐users, clinicians, policy‐makers, researchers and commissioners.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of hospital‐based specialist palliative care compared to usual care for adults with advanced illness and their unpaid caregivers/families.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Due to the increasing numbers of RCTs in palliative and end‐of‐life care, and also because they are the most robust experimental design, this review only included RCTs (including cluster‐unit randomised trials). We used established approaches to include and analyse RCTs following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

All studies evaluated effectiveness regarding one or more of our primary or secondary outcomes. In the economic component of the review, we included studies conducted alongside (or as part of) the main effectiveness trial and ones that also met the eligibility criteria for the effectiveness component. Full economic evaluation (i.e. cost‐effectiveness analyses, cost‐utility analyses, cost‐benefit analyses); partial economic evaluations (i.e. cost analyses, cost‐description studies, cost‐outcome descriptions); and studies that reported more limited information, such as estimates of resource use or costs associated with service use, were eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

-

Adult (≥ 18 years) patients receiving hospital‐based specialist palliative care:

these patients were diagnosed with advanced, life‐limiting or life‐threatening illness (malignant or non‐malignant), which was likely to compromise their quality of life in some way;

diseases and health‐related conditions included (with the corresponding International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10)) malignant neoplasms (ICD‐10 codes: C00‐C97) and non‐malignant and other health‐related conditions, specifically: heart disease, including cerebrovascular disease (ICD‐10 codes: I00‐I52, I60‐69), renal disease (ICD‐10 codes: N17, N18, N28, I12, I13), liver disease (ICD‐10 codes: K70‐K77), respiratory disease (ICD‐10 codes: J06‐J18, J20‐22, J40‐47, J96), neurodegenerative disease (Huntington’s disease (ICD‐10 code: G10), Parkinson's disease (ICD‐10 code: G20), multiple sclerosis (ICD‐10 code: G35), motor neuron disease (ICD‐10 code: G12.2)), multi‐system degeneration (ICD‐10 code: G90.3), progressive supranuclear ophthalmoplegia (ICD‐10 code: G23.1), Alzheimer’s dementia and senility (ICD‐10 codes: F01, F03, G20, R54), and HIV/AIDS (ICD‐10 codes: B20‐B24)); and

unpaid caregivers, including those who had received a pre‐bereavement intervention from one or more hospital‐based specialist palliative care staff in order to manage or alleviate bereavement‐related problems prior to the death of the inpatient: unpaid caregivers are likely to be family, friends or significant others associated with the patient (Payne 2010a; Payne 2010b).

Types of interventions

Hospital‐based Specialist Palliative Care (herein HSPC) varies between settings and countries. In order to allow for these differences, we included studies that described HSPC as "palliative care, generic palliative care, hospice care (provided in hospital settings) or specialist palliative care". It was delivered by a specialist palliative care team or by a "specialist palliative care", "palliative care" or "hospice outreach (based in hospital settings)" staff member. In order to account for differences in specialist palliative care between countries, and also because of the sometimes limited details provided on the specialist training of palliative care teams, we decided to include studies where training/clinical experience in specialist palliative care was made explicit as well as those that simply stated the involvement of a palliative care team; eligibility was informed by activity of delivering specialist palliative care rather than level of specialist training (Luckett 2014). Higher specialist training in palliative care was also accepted if the authors described the professionals as palliative care experts or specialists (for example, palliative care physician or nurse) or if they had obtained clinical competencies and professional characteristics required for the delivery of specialist palliative care through clinical experience (NCPC 2012). The intervention was provided to adults receiving hospital inpatient, outpatient, outreach or HSPC as part of wider services, and their unpaid caregivers/families.

We included studies of HSPC compared with usual care. Usual care was defined as inpatient or outpatient hospital care without specialist palliative care input (e.g. oncological care) at the point of entry into the study, community care (e.g. primary or specialist care provided in the patient’s place of residence) or hospice care provided outside of the hospital setting. Usual care patients may receive specialist palliative care after entry into the study if requested by the patient, their families or clinicians, however specialist palliative care should not be a routine part of usual care. We extracted descriptive data on what was involved in each intervention.

Similar to a Cochrane Review that examined home palliative care (Gomes 2013), we excluded trials that evaluated hospital palliative care practitioners’ provision of only a biomedical component of palliative care (e.g. oxygen therapy) as this does not encompass the holistic nature of palliative care assessment or treatment.

Types of outcome measures

We developed the primary and secondary outcomes for this review from previous reviews regarding the effectiveness of palliative care and those that we thought to be clinically relevant (Gomes 2013; Gysels 2004; Higginson 2003; Higginson 2010). The outcomes reflect the multicomponent nature of palliative care and the provision of both direct (e.g. face‐to‐face delivery of patient care) and indirect (e.g. concerning practitioners' prescribing rationale) patient care, and care for unpaid caregivers/families while the patient is still alive. We chose to measure health‐related quality of life and symptom burden reported as adjusted endpoint values as our primary outcomes. We selected health‐related quality of life and symptom burden as primary outcomes because the major focus of palliative care is to improve quality of life while providing optimal management of symptoms (Dixon 2015).

Primary outcomes

Patient health‐related quality of life, measured using validated assessment scales which may be generic and disease/condition‐specific health‐related quality of life measures; and

Patient symptom burden, specifically, a collection of two or more symptoms which could be physical (e.g. pain), psychological (e.g. anxiety, depression), social or spiritual domains, either patient or proxy‐reported through validated generalised assessment scales.

Secondary outcomes

Patient satisfaction with care through validated assessment scales;

Caregiver/family satisfaction with care through validated assessment scales;

Achieving patient's preferred place of care;

Achieving patient's preferred place of death;

Patient mortality/survival;

Pain measured using validated assessment scales;

Patient anxiety and depression measured using validated assessment scales;

Breathlessness measured using validated assessment scales;

Adverse events in participants and unpaid caregivers;

Unpaid caregiver symptom control, specifically physical, psychological (e.g. anxiety and depression), social or spiritual domains, reported through validated assessment scales and burden, including emotional strain, burden, distress, mastery or positive aspects of caregiving through validated assessment scales;

Unpaid caregiver pre‐ and post‐bereavement outcomes, reported using validated outcome scales of multidimensional caregiving experiences (strain, distress, positive appraisals, and family well‐being), caregiver prolonged grief, multidimensional grief responses (despair, panic behaviour, blame and anger, detachment, disorganisation and personal growth), quality of life.

Resource use: institutional care services use (e.g. emergency department (ED) or accident and emergency (A&E), intensive care unit use, inpatient stay, care in nursing homes (or skilled nursing homes) etc.), outpatient clinic services use (e.g. palliative care visits in outpatient settings, consultation with experts in outpatient settings), community care services use (e.g. contact with general practitioners, district nurses, home care, hospice care at home etc.), unpaid caregiver's care, and medications and other resources;

Costs and cost‐effectiveness: costs were calculated based on resource use and unit costs of services, while cost‐effectiveness was measured using e.g. incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios of costs and condition‐specific outcome measures or quality‐adjusted life years (QALYS) or an equivalent.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified studies through electronic searches, handsearching, electronic citation tracking, personal contact and searching of grey literature. We did not place restrictions on language; we assessed non‐English papers with the assistance of a native speaker.

Electronic searches

We identified studies by searching the databases listed below, using a combination of key terms and MeSH terms:

-

Cochrane Library:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); Issue 8 of 12, 2019

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR); Issue 8 of 12, 2019

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Issue 2 of 4, 2015;

Health Technology Assessment (HTA), Issue 4 of 4, 2016;

National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Issue 2 of 4, 2015;

MEDLINE & MEDLINE‐in‐Process (OVID), 1947 to 27 August 2019;

Embase (OVID), 1974 to 27 August 2019;

CINAHL (EBSCO),1982 to 28 August 2019;

PsycINFO (OVID), 1806 to 28 August 2019;

CareSearch, Australian Government's Department of Health and Ageing (http://www.caresearch.com.au/) (from inception to 12 September 2019).

We could not carry out more recent searches in DARE, HTA and NHS EED because they are no longer updated. We also could not carry out a search of the health economic database EURONHEED as it is no longer available. We refined our search strategies with the assistance of the Information Specialist of the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group. Please see Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy in OVID and Appendix 2, Appendix 3, Appendix 4, Appendix 5 and Appendix 6 for all other search strategies.

Searching other resources

We searched clinicaltrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) for ongoing trials on 12 September 2019 (search term: palliative).

Handsearching

We screened the reference lists of all included studies, and three relevant systematic reviews (Haun 2017; Gaertner 2017; Gomes 2013), for additional studies.

Electronic citation tracking

We used the "Citation tacking" option in MEDLINE for lateral searching on the included studies, as recommended for palliative care reviews (Payne 2010a).

Personal contact

We contacted 15 experts in the field for unpublished and ongoing trials. We also contacted study authors for additional information where necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

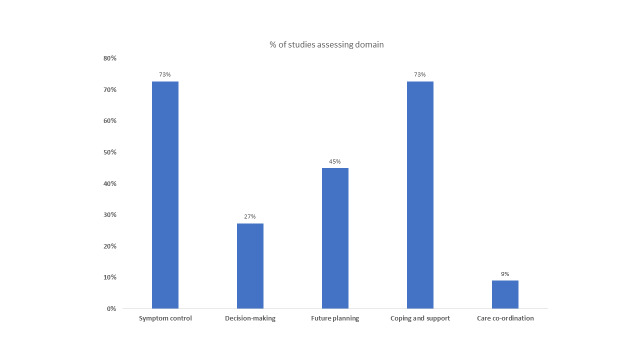

Two review authors (AO and SB) independently screened all titles and abstracts identified in our electronic searches. If, after reading the abstract, doubt persisted regarding the eligibility of the study, we retrieved the full‐text articles for further assessment and again the two reviewers independently assessed these full‐text articles. We resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus. We reported our study selection process using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Liberati 2009) in Figure 1, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two reviewers (AO and SB) independently extracted data from all included studies using a piloted data extraction form (Appendix 7), that we further developed for economic evaluation based on the format and guidelines used to produce structured abstracts of economic evaluations for inclusion in the NHS EED. We entered data into Review Manager (RevMan) (RevMan 2014). We resolved any disagreements by discussion and consensus. Given that the review included some studies by the review authors, we did not involve these authors in the assessment of or extraction of data from their studies. The data extraction form has been used previously for a review on the effectiveness of home palliative care (Gomes 2013). We adapted the form for this review regarding HSPC.

We collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We collected characteristics of the included studies in sufficient detail to populate a 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers (AO and SB)independently assessed risk of bias for each included study, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Chapter 12, Schunemann 2011), with any disagreements resolved by discussion. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study using the 'Risk of bias' tool for randomised controlled studies in RevMan (RevMan 2014).

We assessed the following for each included study:

-

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). We assessed the method used to generate the allocation sequence as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator); or

unclear risk of bias (method used to generate sequence not clearly stated);

we excluded studies that used a non‐random process (e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number).

-

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). The method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment determines whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes); or

unclear risk of bias (method not clearly stated);

we excluded studies that did not conceal allocation.

-

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias) (subjective). We assessed the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received for subjective outcomes (e.g. quality of life, pain, breathlessness). We grouped all subjective outcomes as being at high risk of bias if blinding was unsuccessful. When the study did not include subjective outcomes, we left this domain blank. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken);

unclear risk of bias (insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’);

high risk of bias (no blinding or incomplete blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding).

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias) (objective). We assessed the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received for objective outcomes (e.g. mortality, length of stay in hospital, number of readmissions). When the study did not include objective outcomes, we left this domain blank. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (objective outcomes are unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding and we treated these outcomes as a 'low risk of bias' even if blinding was unsuccessful or not carried out);

unclear risk of bias (insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’); or

we did not rate a high risk of bias for an objective outcome.

-

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias) (subjective). We assessed the methods used to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received for subjective outcomes. We grouped all subjective outcomes as being at high risk of bias if blinding was unsuccessful. When the study did not include subjective outcomes, we left this domain blank. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken);

unclear risk of bias (insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’); or

high risk of bias (no blinding of outcome assessment; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding).

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias) (objective). We assessed the methods used to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received for objective outcomes. Objective outcomes are unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding and we rated these outcomes as a 'low risk of bias' even when blinding was unsuccessful or not carried out. When the study did not include objective outcomes, we left this domain blank. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken);

unclear risk of bias (insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’); or

we did not rate a high risk of bias for an objective outcome.

-

Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias). We assessed whether primary and secondary outcome measures were prespecified and whether these were consistent with those reported. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (protocol is available and all of the study’s prespecified primary and secondary outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the prespecified way);

unclear risk of bias (insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’, including, when the protocol is not available); or

high risk of bias (protocol is available and some prespecified outcomes were not reported; one or more primary outcomes were reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not prespecified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified).

-

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data). We assessed the methods used to deal with incomplete data as:

low risk (< 10% of participants did not complete the study or used ‘baseline observation‐carried‐forward’ analysis);

unclear risk of bias (used 'last‐observation‐carried‐forward' analysis or when the number of dropouts was not reported); or

high risk of bias (used 'completer' analysis).

-

Other bias (other sources of bias). We also assessed whether groups were balanced at baseline and whether differences at baseline were controlled for. We assessed the studies as:

low risk of bias (e.g. if there were no baseline differences or if observed differences were controlled for);

unclear risk of bias (e.g. if there were baseline differences and it was unclear if the differences were significant and also if they were controlled for); or

high risk of bias (e.g. if there were differences that were not controlled for).

-

Size of study (checking for possible biases confounded by small size). We assessed studies as being at:

low risk of bias (≥ 200 participants per treatment arm);

unclear risk of bias (50 to 199 participants per treatment arm; 50 to 199 participants in one treatment arm and ≥ 200 participants in another treatment arm; < 50 participants in one treatment arm and 50 to 199 participants in another treatment arm); or

high risk of bias (< 50 participants per treatment arm).

Quality assessment in studies with a cost/cost‐effectiveness component

We classified health economics studies per the design of the health economic study (e.g. full economic evaluation, partial economic evaluation) and the design of the study generating the effectiveness data of the health economic study (e.g. a single study design, a synthesis of several studies). For full economic evaluations, we assessed the risk of bias in results of the single effectiveness study on which the full economic evaluation study was based and methodological quality of the full economic evaluation study. We used as checklists the BMJ Checklist for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions (Drummond 1996), and the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations (Evers 2005).

For assessment of the quality of relevant economic modelling studies, we planned to use tools such as the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement (Husereau 2013), and the Quality Appraisal Checklist for Economic Evaluations (NICE 2012), supplemented by the Philips Checklist (Philips 2004). We could not apply these planned methods in this review as we did not identify any relevant economic modelling studies for inclusion; we plan to use these tools for future updates of the review, where appropriate.

Measures of treatment effect

If appropriate, we undertook meta‐analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes using RevMan (RevMan 2014). Given that eligible studies were conducted with different populations, countries and years, and that they included different models of HSPC, we had to incorporate the assumption of heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis of our outcomes. We used the inverse variance random‐effects model for meta‐analysis. This method summarises effect sizes from studies by calculating the weighted mean of the effect sizes using the inverse variance of the individual studies as weights (Lee 2016).

We combined data from the RCTs for the primary outcomes (patient health‐related quality of life and patient symptom burden) and expressed the pooled effect as standardised mean difference (SMD) for HSPC compared to usual care; values greater than 0 indicated better patient health‐related quality of life with HSPC, and less than 0 indicated worse health‐related quality of life. By contrast, for symptom burden, values greater than 0 indicated higher symptom burden and less than 0 reduced symptom burden.

We used a P value of 0.05 as the cut‐off value to determine statistical significance and we presented data as effect size with 95% CIs. We did not combine change values with endpoint values in our meta‐analysis because we pooled the data using SMD (Deeks 2011). Furthermore, we pooled adjusted endpoint values presented for patient health‐related quality of life and patient symptom burden as our main analyses because adjusted endpoint values control for differences and provide the most precise and least biased estimates of treatment effects (Deeks 2011). Where possible, we conducted similar meta‐analyses for the other outcomes with the exception of achieving preferred place of death (measured as home deaths) where we expressed the pooled effect as an odds ratio (OR) for HSPC compared to usual care; values greater than 1 indicated increased odds of achieving preferred place of death with HSPC, and less than 1 indicated decreased odds. Even though we used ORs to detect treatment effect, we also presented findings as risk ratios (RRs) (or relative risk) in order to aid the use and interpretation of the findings by end users. We used the Mantel‐Haenszel (M‐H) method in the meta‐analysis for achieving preferred place of death.

In order to combine different instruments in which an increase in score indicates improvement or an increase in score is worse in the same meta‐analysis, we multiplied the mean values from one set of studies by ‐1 to ensure that all the scales were in the same direction.

In order to interpret subgroup differences in our subgroup analyses, we considered the test for subgroup differences and also checked for confidence interval overlap. Where P values were < 0.05 in the test for subgroup differences, we considered this to be evidence of a subgroup effect. However, we were cautious in the interpretation of our subgroup analyses where there were a small number of studies and participants.

We considered that a SMD of 0.2 to < 0.5 constituted a small effect, 0.5 to < 0.8 a moderate effect and ≥ 0.8 constituted a large effect (Cohen 1988).

Economic data

We presented characteristics of the included health economics studies, such as year of study; details of interventions and comparators; study design; data sources; jurisdiction and setting; analytic perspective and time horizon, in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We summarised characteristics and results of included economic evaluations using additional tables, supplemented by a narrative summary that compared and evaluated methods used and principal results between studies. Where possible, we presented point estimates of measures of items of resource use and cost with associated measures of uncertainty for both the intervention and its comparators, as well as point estimates of incremental costs and cost‐effectiveness, again with associated measures of uncertainty. We converted costs to Great British Pounds (GBP) (2018) based on Purchasing Power Parities (PPP) and gross domestic product (GDP) deflators.

Unit of analysis issues

We addressed issues in the analysis of studies with particular characteristics, for example cluster‐randomised trials, in our meta‐analysis. We highlighted whether cluster‐randomised trials presented their intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) and if they made adjustment for clustering. Where studies adjusted for clustering, we used the data they presented in the meta‐analysis. However, where the authors did not present their ICC or adjust for clustering, we contacted the authors for an estimate of the ICC. Where authors did not respond, we estimated an ICC from a previous Cochrane review (Shepperd 2011) and used it to adjust for clustering in order to allow for inclusion of the study in our meta‐analysis. We carried out sensitivity analysis to test the estimate we used for clustering. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions suggests that decisions that may be somewhat unclear should be tested using sensitivity analysis (Higgins 2011a).

Dealing with missing data

When sample sizes and mean (SD) were missing, we did not carry out imputations or estimate the missing values for meta‐analysis. Rather, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a), we contacted study authors to request additional data. Where studies had missing intervention data (such as number of staff involved and skills and so on), we assessed the potential impact of these missing data on the findings of the review in the 'Discussion' section of the review. We sought clarity from study authors regarding study population, analysis and interventions, where required.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined and assessed heterogeneity through the following three measures:

inspecting the studies to examine for plausible areas of heterogeneity based on clinical factors that may influence findings of our meta‐analysis;

inspecting the forest plots;

using the I² statistics to examine the extent and impact of heterogeneity between included studies (Higgins 2011a).

Assessment of reporting biases

In order to detect and manage reporting bias, we took the following steps to attend to:

multiple (publication) bias by contacting study authors to ascertain whether duplication had occurred;

location bias by searching relevant national and international trial registries for all relevant studies (e.g. CENTRAL);

language bias by including studies published in languages other than English; and

outcomes reporting (including non‐publication of economic evaluation outlined in the protocol) through comparing the findings in eligible studies with published protocols, where available. Where published protocols were unavailable, we asked study authors to supply them.

In addition, where there were more than 10 included studies in our meta‐analysis, we used funnel plots and visually inspected them for asymmetry/symmetry as a means of exploring whether there was evidence that study size (precision) was associated with effect size. Where possible, we also conducted relevant tests for asymmetry influenced by data type (e.g. continuous or dichotomous), to assist with examining publication bias and to overcome any reliance on visual inspection (Lau 2006). When we observed asymmetry, we considered publication bias as one (of several) plausible explanations (Sterne 2001).

Data synthesis

Where eligible studies were not sufficiently homogenous to permit meta‐analysis, we extracted quantitative data (means, standard deviations, frequencies and proportions, test coefficients, 95% CIs and effects sizes, where available) and we employed techniques used in narrative synthesis to analyse the data, including:

tabulation, which involved inserting the main elements of extracted data into a table format;

textual descriptions, which involved collating a summary description of each included study (part of Characteristics of included studies);

clustering of group textual descriptions according to attributes; and

vote counting to determine how often certain attributes were reported (Rodgers 2009).

Where possible, we included qualitative data from nested or embedded qualitative studies where qualitative data were used as part of the trial to explore stakeholder views and experiences of the intervention. We analysed these through narrative synthesis methods.

Quality of the evidence

Two review authors independently rated the quality of the outcomes. We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to rank the quality of the evidence using the GRADEprofiler Guideline Development Tool software (GRADEpro GDT 2015) and the guidelines provided in the CochraneHandbook (Chapter 12, Higgins 2011a).

The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome (Chapter 12, Higgins 2011a). The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence:

high: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning a quality level to a body of evidence (Chapter 12, Higgins 2011a):

high: randomised trials; or double‐upgraded observational studies;

moderate: downgraded randomised trials; or upgraded observational studies;

low: double‐downgraded randomised trials; or observational studies;

very low: triple‐downgraded randomised trials; or downgraded observational studies; or case series/case reports.

Factors that may decrease the quality level of a body of evidence are:

limitations in the design and implementation of available studies suggesting high likelihood of bias;

indirectness of evidence (indirect population, intervention,control, outcomes);

unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results (including problems with subgroup analyses);

imprecision of results (wide CIs);

high probability of publication bias.

Factors that may increase the quality level of a body of evidence are:

large magnitude of effect;

all plausible confounding would reduce a demonstrated effect or suggest a spurious effect when results show no effect;

dose‐response gradient.

We downgraded the quality of the evidence by one (−1) or two (−2) if we identified:

serious (−1) or very serious (−2) limitation to study quality;

important inconsistency (−1);

some (−1) or major (−2) uncertainty about directness;

imprecise or sparse data (−1);

high probability of reporting bias (−1).

'Summary of findings' table

We included a 'Summary of findings' table to present the main findings in a transparent and simple tabular format. The table summarised the comparison of HSPC versus usual care (which could be inpatient or outpatient hospital care without specialist palliative care input (e.g. oncological care) at the point of entry to the study, community care (e.g. primary or specialist care provided in the patient’s place of residence), and hospice care provided outside of the hospital setting). The table included key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the outcomes patient health‐related quality of life, patient symptom burden, patient satisfaction with care, achieving patient preferred place of death (measured by number of patients with home death), pain, unpaid caregiver burden, and cost/cost‐effectiveness.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As part of our primary objective, we identified the effective components and determined the comparative effectiveness of HSPC for adults with advanced illness and their unpaid caregivers/families. We compared the resources and costs associated with these services and determined their cost‐effectiveness; compared effectiveness by disease type (e.g. malignant and non‐malignant groups), and country; and we examined other sources of heterogeneity and the applicability of meta‐analysis.

Where possible, we performed subgroup analysis using the following components known to influence the effectiveness of specialist palliative care:

disease type, including malignant, non‐malignant and mixed malignant and non‐malignant disease (mixed diagnoses);

frailty associated with advanced age;

HSPC team composition (e.g. physician‐led, nurse‐led versus multidisciplinary team‐led palliative care services and organisation (e.g. 24‐hour access (out‐of‐hours) versus temporally restricted access)) and taxonomy of the components;

models of HSPC (ward‐based model, inpatient consult model, outpatient model, outreach model and service provision across multiple settings);

early palliative care versus late palliative care to assess the effectiveness of hospital‐based palliative care applied early in the course of a life‐threatening disease from palliative care delivered mainly with high symptom burden or in the terminal phase of illness. To be classified as early palliative care, early palliative care intent had to be stated explicitly or reflected in the sample composition, i.e. most participants had to be enrolled shortly after diagnosis of advanced disease (Haun 2017). Anything besides this, we classified as late palliative care; and

country of origin.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analyses to explore a number of our methodological decisions.

We conducted sensitivity analysis to assess our decision to use an estimate of intracluster‐correlation coefficient (ICC) we had obtained from a previous Cochrane review (Shepperd 2011) to adjust for clustering in one of the cluster‐RCTs (McCorkle 2015). The authors did not respond to our request for the ICC from their study.

Given that combining endpoint scores and change scores is not recommended when using standardised mean differences (SMDs) and also that Cochrane does not recommend pooling adjusted and unadjusted estimates together (Deeks 2011), we pooled studies presenting adjusted endpoint scores as our main meta‐analysis while we carried out sensitivity analyses with studies reporting unadjusted endpoint scores, adjusted change scores and unadjusted change scores.

Results

Description of studies

Also see the Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

We identified 15,927 records from our electronic searches and an additional 55 records from other sources. After removing duplicates, two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of 10,774 records, excluded 10,132 records and selected 642 for full‐text reading. We classed 476 records as not relevant (e.g. systematic reviews, study design).

We included 42 studies reported in 106 records (91 full papers and 15 abstracts), ranging from one to ten records per study (see Included studies). Of the remaining records, we excluded 25 with reasons (see Excluded studies); 34 are ongoing studies, and one study is awaiting classification (Aljohani 2015) (see Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram).

Included studies

Design

All the studies we included were RCTs, comprising one cluster‐RCT (McCorkle 2015), one cluster‐randomised crossover trial (Ma 2019) and eight fast‐track RCTs (Bajwah 2015; Bakitas 2015; Edmonds 2010; Farquhar 2014; Farquhar 2016; Higginson 2009; Higginson 2014; McWhinney 1994). The remaining 32 RCTs had a parallel design.

Sample sizes

Sample sizes in included studies ranged from 30 to 621 participants. The length of recruitment in included studies varied between 10 months and 50 months. In total, we included data from studies involving 7779 participants (6678 adults with advanced illness and 1101 unpaid caregivers/family members). Thirty‐three studies had power calculations (details in 'Characteristics of included studies'). Nine studies were powered on quality of life only (Bekelman 2018; El‐Jawahri 2016; Franciosi 2019; Groenvold 2017; Rogers 2017; Tattersall 2014; Temel 2010; Temel 2017; Vanbutsele 2018). Ma 2019 was powered on proportion of patients transitioning to do‐not‐resuscitate and do‐not‐intubate (DNR/DNI). In addition to quality of life, Bakitas 2015 also performed calculations on depression, Solari 2018 on symptom burden, O'Riordan 2019 on pain, while Bakitas 2009 and Sidebottom 2015 included depression and symptom burden. Farquhar 2014 and Farquhar 2016 were powered on distress due to breathlessness, Brannstrom 2014 on symptom burden, Brumley 2007 on cost, Carson 2016 on depression and anxiety, Grudzen 2016 on time to palliative care, Janssens 2019 on hospital admission, Rodin 2019 on traumatic stress symptoms, Bajwah 2015, Edmonds 2010 and Higginson 2009 on the Palliative care Outcome Scale (POS), Lowther 2015 on the African Palliative care Outcome Scale (APOS), Higginson 2014 on Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRDQ) mastery domain, Hopp 2016 and Ozcelik 2014 on palliative outcomes and palliative care service respectively, McWhinney 1994 on pain and nausea and Woo 2019 on pain and depression.

Eight studies were well‐powered at recruitment and also at the primary point of analyses (Carson 2016; Edmonds 2010; Farquhar 2016; Higginson 2014; Ma 2019; Ozcelik 2014; Solari 2018; Temel 2017). Fourteen studies were underpowered at recruitment stage (i.e. participants enrolled) by three participants (Brumley 2007; Groenvold 2017; Hopp 2016), four (Grudzen 2016), eight (Rodin 2019), 19 (Nottelmann 2018), 25 (O'Riordan 2019), 30 (Tattersall 2014), 50 (Rogers 2017), 74 (McWhinney 1994), 78 (Bakitas 2009), 111 (Janssens 2019), 153 (Bakitas 2015) and 268 (Sidebottom 2015). In one of the underpowered studies (Rogers 2017), the data and safety monitoring board in consultation with the sponsoring agency recommended a sample size reduction due to enrollment rates, a mortality rate that was lower than predicted and observed outcomes differences at the intermediate time point. Reasons provided for underpowered studies included slower than anticipated accrual, resource constraints, early deaths, problems with recruitment and low compliance rate for completion of questionnaires. The remaining 11 studies included the numbers that they had planned to recruit but dropped below the required numbers by the first time point of analyses (i.e. following baseline assessment and after receiving the intervention or control). These studies were underpowered by two participants (Brannstrom 2014), three participants (El‐Jawahri 2016), five participants each (Bajwah 2015; Higginson 2009), six participants each (Lowther 2015; Farquhar 2014), 13 participants (Temel 2010), 22 participants (Vanbutsele 2018), 29 participants (Franciosi 2019), 60 participants (Woo 2019) and 70 participants (Bekelman 2018). Nine studies did not report any power calculation (Ahronheim 2000; Cheung 2010; Gade 2008; Jingfen 2017; Kane 1984; Mendoza‐Galindo 2018 (abstract only); McCaffrey 2013; McCorkle 2015; Wallen 2012) (see Figure 2 for a graphical representation of the power of included studies at recruitment and follow‐up). Overall, 14 studies examined post‐intervention assessments in more than 100 participants.

2.

A figure describing the power of included studies at recruitment and follow‐up

Setting

Nineteen studies were carried out in USA. Six studies took place in the UK (Bajwah 2015; Edmonds 2010; Farquhar 2014; Farquhar 2016; Higginson 2009; Higginson 2014), and three studies occurred in Australia (Cheung 2010; McCaffrey 2013; Tattersall 2014). One study was conducted in Sweden (Brannstrom 2014), two in Denmark (Groenvold 2017; Nottelmann 2018), one in Switzerland (Janssens 2019), one in Belgium (Vanbutsele 2018), two in Italy (Franciosi 2019; Solari 2018), and one in Turkey (Ozcelik 2014). McWhinney 1994 and Rodin 2019 were carried out in Canada, while Woo 2019 was undertaken in South Korea. Lowther 2015 took place in Kenya and Jingfen 2017 was conducted in China. Mendoza‐Galindo 2018 (abstract only) was carried out in Mexico.

Thirty studies recruited from hospital settings. Three of these studies recruited from intensive care units (ICU) (Carson 2016; Cheung 2010; Ma 2019). Of these 30 studies, Ahronheim 2000 recruited patients with advanced dementia from Mount Sinai Hospital, Bajwah 2015 recruited from a specialist interstitial lung disease centre, Janssens 2019 from patients followed by Geneva University Hospitals on long‐term oxygen therapy (LTOT) and/or home non‐invasive ventilation (NIV) as well as those hospitalised for acute exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Oulmonary Disease (COPD) in the general internal medicine and geriatric wards, Lowther 2015 from outpatient HIV clinics in a community hospital, McCorkle 2015 from disease‐specific multidisciplinary clinics at a cancer hospital, O'Riordan 2019 from new inpatient admissions to the medicine and cardiology services, Solari 2018 from three Italian multiple sclerosis centres and Franciosi 2019 from outpatient and inpatient settings at five Italian cancer centres. Seven studies recruited from oncology centres or clinics (Groenvold 2017; Rodin 2019; Tattersall 2014; Temel 2010; Temel 2017; Vanbutsele 2018; Woo 2019). Bakitas 2009 and Bakitas 2015 recruited from oncology clinics of a cancer centre and affiliated outreach clinics and the Veterans Affairs Medical Centre (VAMC).

Eleven studies recruited from primary care and/or secondary care. For example, Gade 2008 recruited from community medical services and inpatient units, while McWhinney 1994 recruited through family physicians and home care nurses. Brumley 2007 received referrals from discharge planners, primary care physicians and other specialty physicians, whereas Rogers 2017 enrolled both hospitalised patients and recently discharged patients who were at high risk of rehospitalisation. Higginson 2009 received referrals from local health and social care professionals. Edmonds 2010 received referrals from health and social care professionals and, in a few instances, through voluntary organisations and self‐referral.

Mendoza‐Galindo 2018 (abstract only) did not present the setting where recruitment took place..

Participants

Twenty‐one studies were carried out with patients who had severe/advanced cancer or their unpaid caregivers/family members or both (Bakitas 2009; Bakitas 2015; El‐Jawahri 2016; Farquhar 2014; Franciosi 2019; Groenvold 2017; Grudzen 2016; Jingfen 2017; Kane 1984; McCorkle 2015; McWhinney 1994; Mendoza‐Galindo 2018 (abstract only); Nottelmann 2018; Ozcelik 2014; Rodin 2019; Tattersall 2014; Temel 2010; Temel 2017; Vanbutsele 2018; Wallen 2012; Woo 2019). A range of cancers were included in these studies comprising solid and non‐solid tumour cancers. Seven studies involved both cancer and non‐cancer populations (mixed populations) (Brumley 2007; Carson 2016; Cheung 2010; Gade 2008; Higginson 2014; Ma 2019; McCaffrey 2013), while the remaining 14 studies had only non‐cancer populations. The non‐cancer populations were those with interstitial lung disease (Bajwah 2015), heart failure (Bekelman 2018; Brannstrom 2014; Hopp 2016; O'Riordan 2019; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015), HIV (Lowther 2015), dementia (Ahronheim 2000), multiple sclerosis (Edmonds 2010; Higginson 2009; Solari 2018), COPD (Janssens 2019) and a combination of COPD (83%) and other non‐malignant diseases (Farquhar 2016). Two studies were with rural populations (Bakitas 2009; Bakitas 2015), while Hopp 2016 was with a predominantly African‐American population (92%). Thirty‐five studies were conducted or first published from 2010 onwards, with 89% taking place within the last six years (see Characteristics of included studies for details).