Keywords: calcium, cancer, diabetes, genetics, metabolism

Abstract

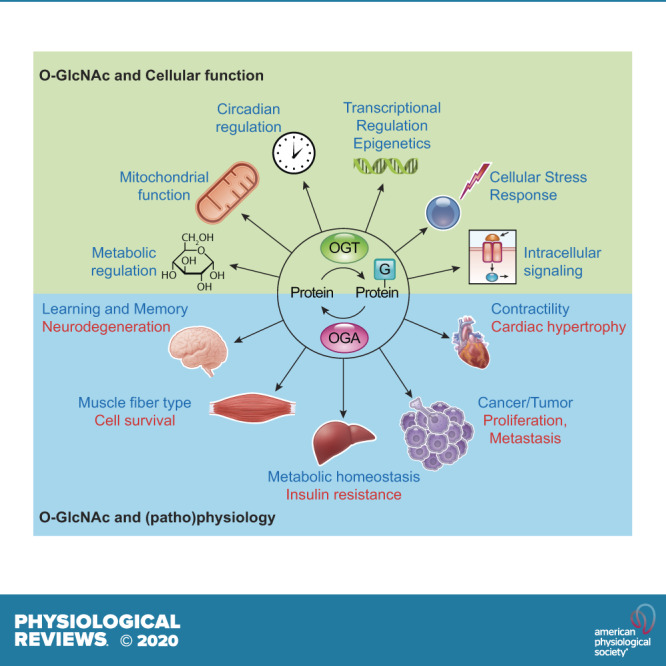

In the mid-1980s, the identification of serine and threonine residues on nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins modified by a N-acetylglucosamine moiety (O-GlcNAc) via an O-linkage overturned the widely held assumption that glycosylation only occurred in the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and secretory pathways. In contrast to traditional glycosylation, the O-GlcNAc modification does not lead to complex, branched glycan structures and is rapidly cycled on and off proteins by O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), respectively. Since its discovery, O-GlcNAcylation has been shown to contribute to numerous cellular functions, including signaling, protein localization and stability, transcription, chromatin remodeling, mitochondrial function, and cell survival. Dysregulation in O-GlcNAc cycling has been implicated in the progression of a wide range of diseases, such as diabetes, diabetic complications, cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases. This review will outline our current understanding of the processes involved in regulating O-GlcNAc turnover, the role of O-GlcNAcylation in regulating cellular physiology, and how dysregulation in O-GlcNAc cycling contributes to pathophysiological processes.

CLINICAL HIGHLIGHTS.

The modification of proteins by sugars is one of the most common posttranslational modifications of proteins. Such modifications were believed to occur only on extracellular and secreted proteins and to consist of large branching structures comprising different sugar molecules. In the mid-1980s, a new modification was identified which consisted of a single N-acetylglucosamine moiety (O-GlcNAc) attached to serine and threonine residues of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. Since its discovery, O-GlcNAc modification of proteins has been shown to affect numerous cellular functions, and changes in O-GlcNAc levels have been implicated in a wide variety of diseases. The goal of this review is to summarize our current knowledge of O-GlcNAc biology and its contribution to normal physiology and disease.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Brief History of O-GlcNAc

The modification of proteins by carbohydrates, otherwise known as protein glycosylation, is the most common posttranslational modification of proteins and occurs in all cells and organisms (1). In the early 1900s, there was considerable speculation that carbohydrates were important parts of the structure of proteins, but the technology was lacking to provide definitive evidence. It was not until the 1960s and 1970s that a better understanding of the structure and function of these complex glycans on proteins started to emerge. Through the mid-1980s, the consensus was that protein glycosylation was restricted to extracellular proteins that originated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, and secretory pathway (1). However, in 1984, Torres and Hart (2) designed a study to characterize terminal N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues on the surface of lymphocytes. Unexpectedly, they demonstrated that the majority of these terminal residues were localized inside the cell, and that rather than part of extended glycan structures, they existed as a single O-linked GlcNAc monosaccharide.

Two years later, Holt and Hart (3) characterized the cellular distribution of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins in rat liver cells, demonstrating that while they were found in nearly every cellular compartment, they were particularly enriched in the cytoplasm and nucleus. In 1987, a monoclonal antibody to rat liver nuclear pore complex (clone RL2), appeared to primarily recognize O-linked O-GlcNAc groups (4). Hanover et al. (5) also reported nuclear pore proteins were modified by O-GlcNAc; however, the functional consequence of this modification was unclear at that time. During the same period, Holt et al. (6) identified both serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) residues as the primary residues modified by O-GlcNAc. The fact that O-GlcNAcylated proteins were especially enriched in the nucleus raised the possibility that the modification could be involved in protein transport into the nucleus; however, the observation that cytoskeletal proteins in erythrocytes, which lack a nucleus, were modified by O-GlcNAc suggested other functions for this modification (7). In 1992, the protein responsible for adding O-GlcNAc to proteins, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) was purified (8), but it was not until 1997 that the gene encoding OGT was identified, revealing a glycosyltransferase that was unrelated to any other previously known glycosyltransferases (9).

In contrast to traditional protein glycosylation, it was quickly established that O-GlcNAc modifications occurred rapidly and reversibly (10), suggesting the existence of an N-acetyl-glucosaminidase(s) responsible for its removal from proteins. Dong et al. (11) purified an O-GlcNAcase that was distinctly different from lysosomal hexosaminidases, in that it was localized in the cytosol and was optimally active at a neutral, rather than acidic, pH. In 2001, O-GlcNAcase was cloned and recognized to be identical to a previously known hexosaminidase C of unknown function, which specifically cleaved O-GlcNAc but not O-linked N-acetylgalactosamine (O-GalNAc) from glycopeptides (12). O-GlcNAcase was subsequently shown to have an identical sequence to a previously identified protein from meningioma patients called meningioma expressed antigen 5 (MGEA5) (13).

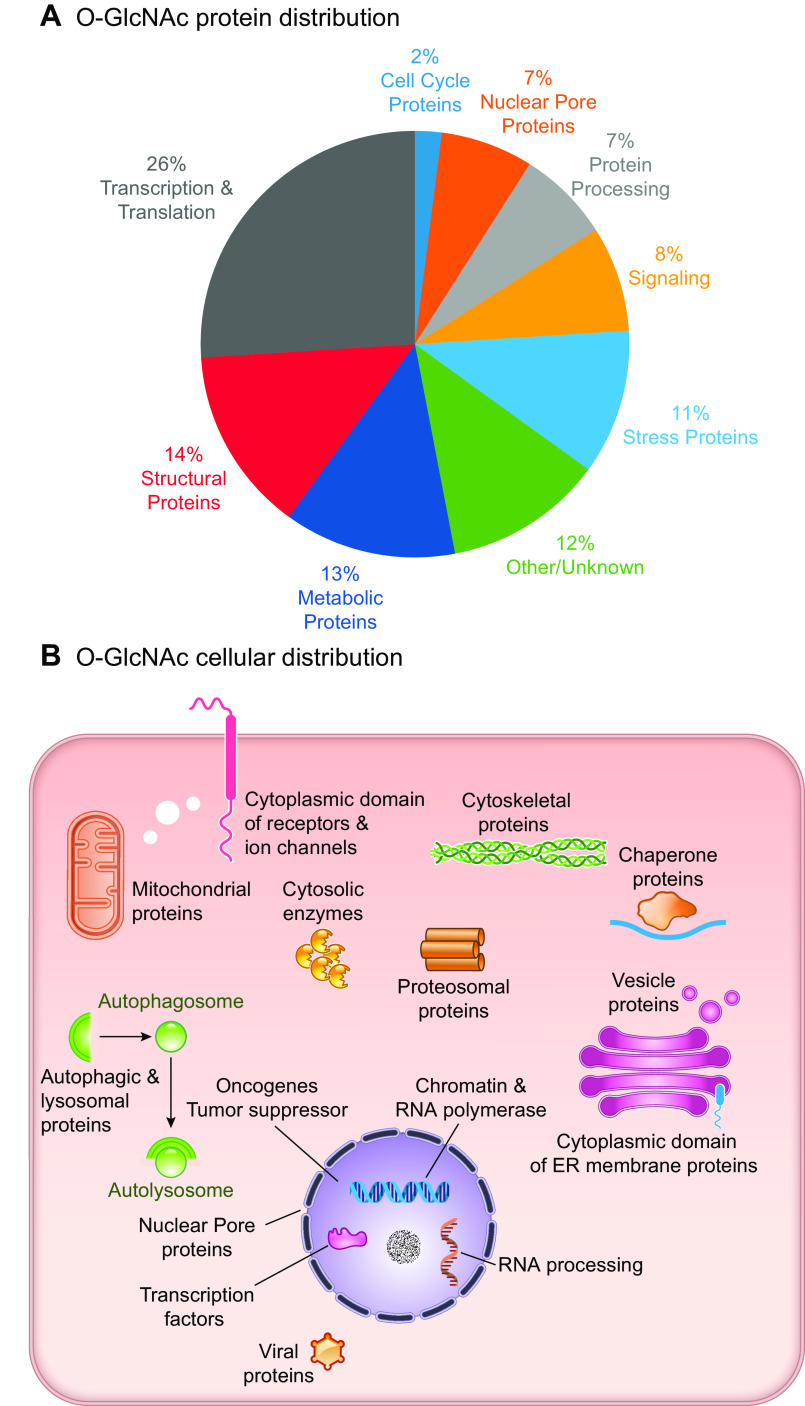

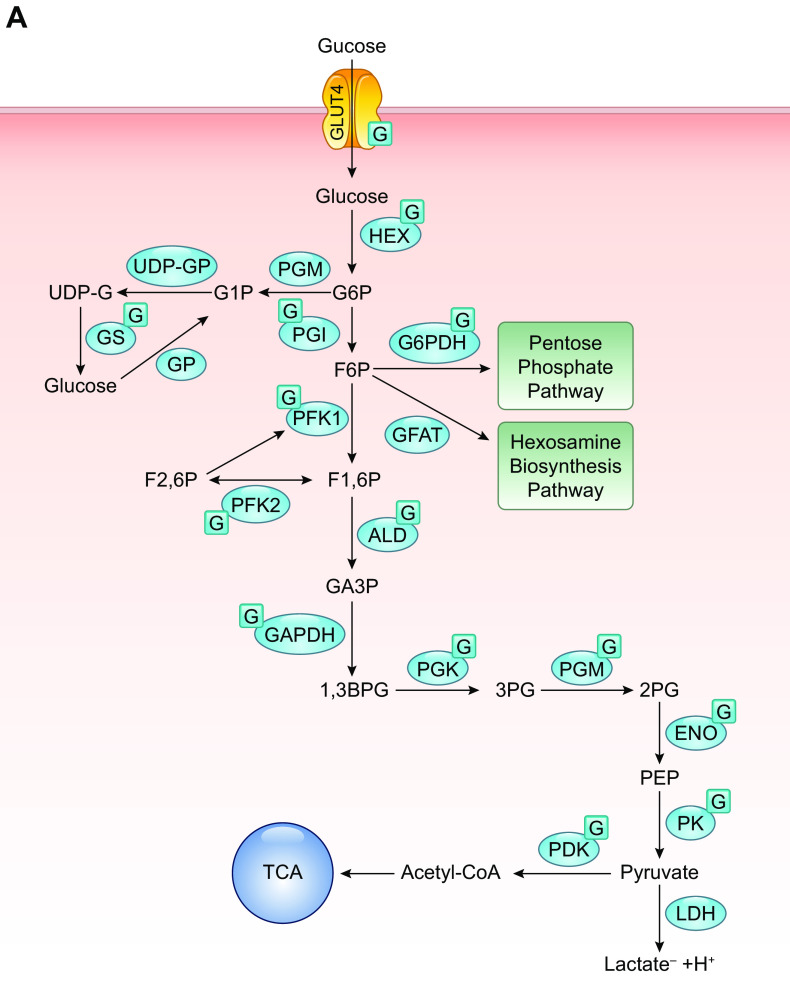

Over the decades since its discovery, O-GlcNAc modified proteins have been identified in all metazoans, some bacteria, protozoa, and viruses, but to date, not in yeast (14). Recent studies have suggested that in yeast, the addition of O-linked mannose (O-Man) on nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins might play a similar role to O-GlcNAc (15). In support for the necessity of O-GlcNAc signaling in mammals, germline deletion of OGT in mice has been shown to be embryonically lethal (16), and deletion of OGA results in perinatal mortality in mice (17). Furthermore, mammalian OGT and OGA are ubiquitously expressed, and proteins of every functional class have been shown to be subject to O-GlcNAcylation (FIGURE 1A) (18). Since its discovery, O-GlcNAcylation has been shown to contribute to numerous cellular functions, including signaling, protein localization and stability, transcription, chromatin remodeling, mitochondrial function, and cell survival (FIGURE 1B) (14). Given its diverse roles, it is not surprising that dysregulation in O-GlcNAcylation has been implicated in a wide range of pathophysiological processes, such as diabetes, diabetic complications, cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases (19–24).

FIGURE 1.

A: O-linked N-acetylglucosamine acylated (O-GlcNAcylated) proteins belong to many different classes of proteins responsible for regulating diverse cellular processes. Some of the largest classes of proteins include those in regulating metabolism, transcription, and translation, as well as structural proteins. B: O-GlcNAcylated proteins are present in numerous cellular compartments, including the nucleus, cytosol, and mitochondria. Cytosolic domains of membrane proteins are also O-GlcNAcylated, as well as proteins involved in autophagy and proteosomal degradation of proteins, chaperone proteins, vesicle proteins, and numerous cytosolic proteins and enzymes. This figure is based, in part, on information presented in Chapter 19, The O-GlcNAc Modification, Essentials in Glycobiology, 3rd ed. (14). ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

1.2. Differences between O-GlcNAc and Traditional Glycosylation

Until the paradigm-changing study by Torres and Hart (2), protein glycosylation was thought to be limited to extracellular and excreted proteins. These proteins are processed via the ER-Golgi pathway, which contains a large number of glycosyltransferases that are responsible for creating N- and O-linked glycan structures. N-glycans are attached to proteins as asparagine residues via an N-glycosidic bond; whereas, O-glycans are attached to Ser or Thr residues. These proteins are subject to processing and maturation by numerous glycosyltransferases, leading to stable elongated and branched structures comprising a number of different monosaccharides. Glycosyltransferases are estimated to account for at least 2% of the human genome (25). The importance of the tight regulation of this process is highlighted by the fact that mutations in genes related to glycosylation are associated with more than 100 human genetic diseases, which are frequently associated with intellectual disabilities, as well as abnormalities in most organ systems (25).

Key distinguishing features of the O-GlcNAc modification are that 1) with few exceptions, it occurs primarily on nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins; 2) it consists of a single monosaccharide; 3) it is dynamic and rapidly reversible; 4) it is catalyzed by a single unique O-GlcNAc transferase, and 5) it is removed by a glycohydrolase that is specific for the removal of O-GlcNAc. It is of note that only very recently have mutations in the OGT gene been linked to human disease, such as intellectual disability (26–29). How mutations of OGT lead to disease and what specific functions are perturbed remain to be determined. In light of the growing recognition of the importance of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins in regulating cellular homeostasis—and that it is likely as abundant a modification as phosphorylation—it may seem surprising that it had not been identified earlier. One reason for this is that proteins modified by O-GlcNAc do not exhibit changes in mobility during gel electrophoresis, because of their low molecular weight and because unlike O-phosphate, it is uncharged. Moreover, despite its abundance, it exhibits low stoichiometry, estimated to be 5–10% of a specific site. In addition, the presence of hexosaminidases can remove O-GlcNAc from proteins unless they are specifically inhibited.

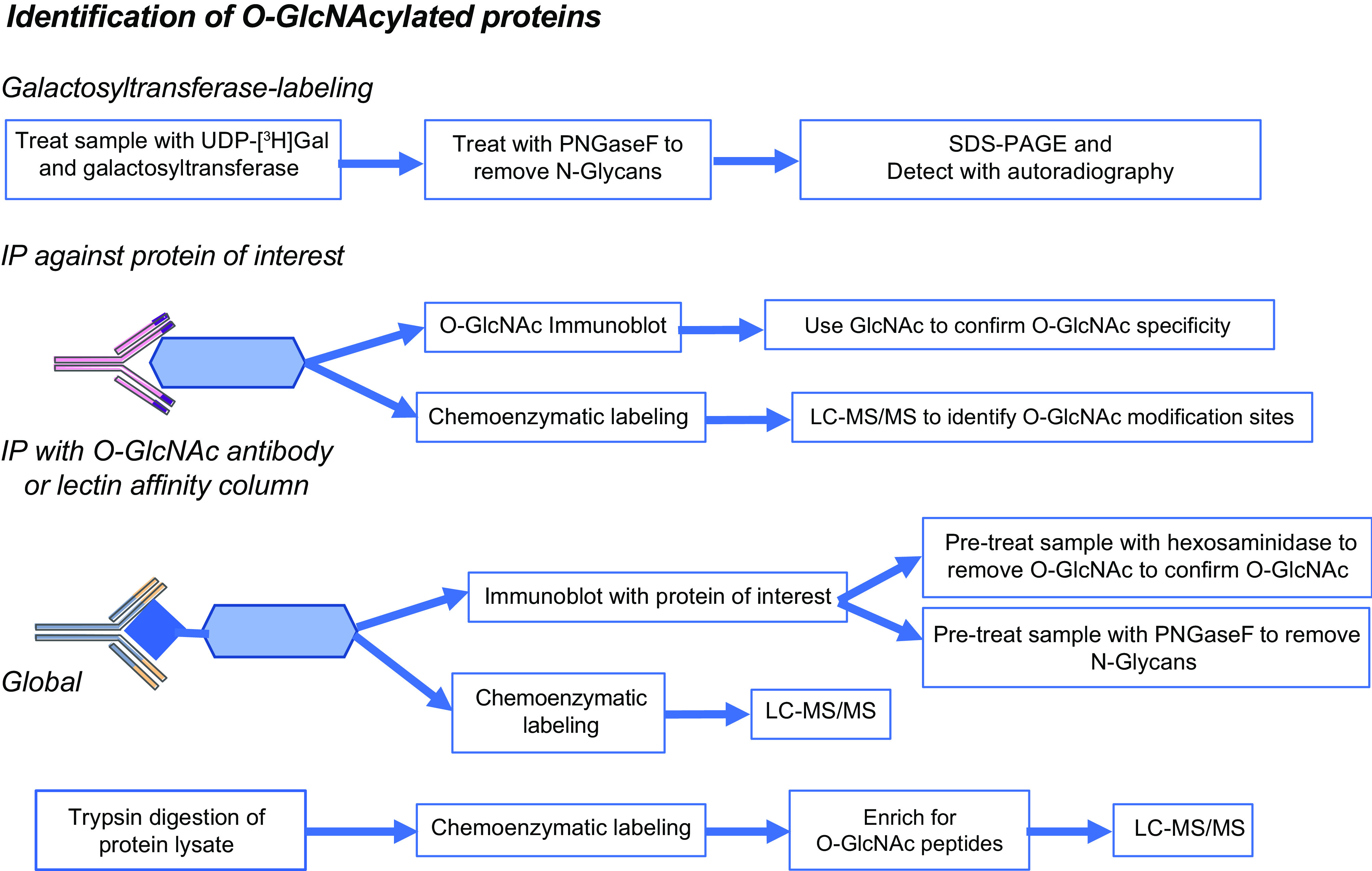

1.3. Identification of O-GlcNAcylated Proteins

The most widely used approach to detect O-GlcNAcylated proteins are pan-specific O-GlcNAc antibodies, the most commonly being RL2 and CTD110.6, but there are also a number of other commercially available O-GlcNAc antibodies as listed in TABLE 1 These can be used to provide a semiquantitative assessment of overall changes in O-GlcNAc levels via immunoblot or distribution of O-GlcNAc via immunohistochemistry in tissues and cells (FIGURE 2). The limitations of these antibodies include the fact that they have epitope specificity, and their selectivity for high- versus low-abundance proteins. Furthermore, a continuing limitation in the study of O-GlcNAcylated proteins is the lack of commercially available site-specific O-GlcNAc antibodies, although several have been developed for specific studies (79–82). Because of the lack of site-specific antibodies to determine whether a protein of interest is an O-GlcNAc target, the simplest approach is to immunoprecipitate the protein of interest followed by an O-GlcNAc immunoblot; however, because of differences in epitope specificities, a negative result with a single antibody does not preclude the possibility that a protein is modified. Moreover, because of the possibility of cross-reactivity with other sugars, if a positive result is obtained, a number of additional control experiments should be considered, such as preincubation with free GlcNAc to outcompete the antibody. Additionally, their cross-reactivity with N-linked modifications varies by detection conditions (83). A number of methodological reviews on different approaches for studying O-GlcNAcylated proteins have been published that provide valuable technical details (44,45, 84,85).

Table 1.

Tools for use in studying O-GlcNAc levels in cells and tissues

| Antibodies* | Characteristics and Limitations | Commercial Availability |

|---|---|---|

| CTD110.6 (IgM) (30) | Monoclonal antibody raised against RNA polymerase II subunit 1C terminal domain. Reportedly less dependent on protein structure than other antibodies, thereby, recognizing more proteins. Relatively low-binding affinity, therefore, biased toward more highly abundant proteins. | Multiple sources |

| HGAC39 (IgG) (31–33) | Monoclonal antibody raised against streptococcal group A carbohydrate (GAC) demonstrated to recognize O-GlcNAcylated proteins. | No |

| HGAC85 (IgG) (33) | Monoclonal antibody raised against streptococcal group A carbohydrate (GAC) demonstrated to recognize O-GlcNAcylated proteins. Not as widely used as CTD110.6 or RL2. Some of the most recent studies have used it in ChIP-chip assays. | Multiple sources |

| MY95 (IgG) (34,35) | Originally generated as an antinuclear pore complex antibody, subsequently shown to recognize O-GlcNAc modification. | No |

| RL2 (IgG) (4) | Because of epitope specificity, having been raised against nuclear pore protein, it recognizes only a subset of O-GlcNAc proteins. Relatively low binding affinity; therefore, it is biased toward more highly abundant proteins. This is the case for all pan-O-GlcNAc antibodies. | Multiple sources |

| 1F5.D6(14) (IgG) (36) | Appears to recognize a wider range of O-GlcNAcylated proteins, including those below 50 kDa that are not usually identified by RL2 or CTD110.6. | Millipore |

| 9D1.E4(10) (IgG) (36) | Appears to recognize a wider range of O-GlcNAcylated proteins, including those below 50 kDa, which are not usually identified by RL2 or CTD110.6. | Millipore |

| 18B10.C7(3) (IgG) (36) | Appears to recognize a wider range of O-GlcNAcylated proteins, including those below 50 kDa, which are not usually identified by RL2 or CTD110.6. | Millipore |

| Other Identification Methods | Characteristics and Limitations | Commercial Availability |

|---|---|---|

| Agrocybe aegerita GlcNAc-specific lectin (AANL) (37) | AANL, also reported as AAL2, is a useful tool for enrichment and identification of O-GlcNAcylated proteins and peptides. | Not known |

| Click-IT O-GlcNAc Enzymatic Labeling System (38–40) | Chemoenzymatic labeling of proteins resulting in O-GlcNAc residues being replaced by azido-modified galactose (GalNAz), followed by chemoselective ligation azide. Resulting proteins can be detected via Western blot using a using a variety of alkyne-modified chemical probes. This approach is not epitope specific, which has advantages over pan-O-GlcNAc antibodies; however, more sample processing steps are required. | Multiple sources |

| Galactosyl transferase/ [3H]-galactose (41) | Results in incorporation of 3H into terminal GlcNAc residues on proteins allowing for detection by autoradiography. Can be very time intensive because of low sensitivity of 3H. | Multiple sources |

| Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) and succinylated WGA (sWGA) (41) | Both WGA and sWGA can be used for immunoblotting. WGA identifies all terminal GlcNAc residues, as well as sialic acid. sWGA reduces affinity for sialic acid. Lack of specific for O-GlcNAc requires careful interpretation. | Multiple sources |

| Enrichment Strategies | Characteristics and Limitations | Commercial Availability |

|---|---|---|

| β-elimination followed by Michael addition of dithiothreitol (BEMAD) (42) | BEMAD relies on the β-elimination of phosphate or O-GlcNAc under basic conditions followed by Michael addition using dithiothreitol or a biotin-thiol probe. | |

| Chemi-enzymatic labeling (43) | Using the same approach described for BEMAD, it replaces O-GlcNAc with GalNAz, combined with a biotin- or streptavidin-cleavable linker can be used to enrich O-GlcNAcylated peptides. A range of linkers have been developed that have different properties. | |

| Immunoprecipitation (36, 44) | The most widely used antibodies, RL2 and CTD110.6, do not perform well for immunopurification. Although not as widely used, the Millipore antibodies listed above have been reported to be effective for IP. | |

| WGA-agarose (45) | Because of the lack of specificity for O-GlcNAc, other glycoproteins will be copurified. This can be minimized by pretreatment to remove the N- and O-linked glycans. | Multiple sources |

| GFAT Inhibitors | Characteristics and Limitations | Commercial Availability |

|---|---|---|

| Azaserine (46) | Glutamine analog used to decrease HBP flux by inhibiting GFAT; however, it lacks specificity as it can inhibit other pathways that utilize glutamine (47). In the absence of any other small molecule GFAT inhibitors, it continues to be widely used, but interpretation of results needs to be cautious. | Multiple sources |

| 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) (46) | Glutamine analog used to decrease HBP flux by inhibiting GFAT; however, it lacks specificity as it can inhibit other pathways that utilize glutamine (48). In the absence of any other small molecule GFAT inhibitors, it continues to be widely used, but interpretation of results needs to be cautious. | Multiple sources |

| OGA Inhibitors | Characteristics and Limitations | Commercial Availability |

|---|---|---|

| α-GlcNAc thiolsulfonate (49) | OGA inhibitor exhibiting selectivity of short OGA compared to long OGA. | No |

| Gluco-nagstatin (50,51) | Based on natural product, nagstatin, which is a potent inhibitor of β-hexosaminidase. Inhibits OGA but is more effective for of β-hexosaminidase. | No |

| GlcNAcstatins (50, 52,53) | Family of OGA inhibitors, with high degree of potency and selectivity. | Abmole Bioscience, Inc. |

| NAG-thiazoline (50, 54) | Inhibitor of OGA with much greater selectivity over other hexosaminidases than PUGNAc. | No |

| NButGT (50, 55,56) | OGA inhibitor based on NAG-thiazoline scaffold. Less potent that NAG-thiazoline but even more selective over other hexosaminidases. | No |

| PUGNAc (57) | Widely used cell permeable OGA inhibitor, but also inhibits hexosaminidase A and B inhibitor. Limited aqueous solubility; usually dissolved in DMSO prior to dilution in aqueous solutions for biological studies. | Multiple sources |

| Streptozotocin (50, 54, 58,59) | A GlcNAc analog initially thought to inhibit OGA. Has major off target effects and more recent studies have reported that it does not inhibit OGA. Not recommended for use. | Multiple sources |

| Thiamet-G (50, 60) | Derivative of NButGT, with greater stability, water soluble, and orally available. | Multiple sources |

| OGT Inhibitors | Characteristics and Limitations | Commercial Availability |

|---|---|---|

| Alloxan (61,62) | A weak OGT inhibitor with numerous off target effects. Requires millimolar concentrations to lower cellular O-GlcNAc levels. Not recommended for use. | Multiple sources |

| Benzyl-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-α-d-galactopyranoside (BADGP)(63,64) | Although BADGP decreases O-GlcNAc levels in millimolar range it lacks specificity for OGT. Inhibits other O-Glycosyltransferases. Not recommended for use. | Sigma |

| L01 (63) | Effective in reducing cellular O-GlcNAc levels in 10–100-µM range. | No |

| OSMI-1 (65–68) | Reduces O-GlcNAc levels in cells at ∼50 µM. Shown to be specific for OGT compared with other glycosyltranserases. | Sigma |

| OSMI-3, OSMI-4 (69) | On the basis of OSMI-1 scaffold, but with greater potency. Reduces cellular O-GlcNAc levels in ∼5-µM range. | ProbeChem |

| ST045849 (TT04) (63, 66, 70–73) | Identified via high throughput screen. Specificity for OGT compared to other glycosyltranserases unclear. | TimTech |

| ST060266 (70, 74) | Identified via high-throughput screen. Specificity for OGT compared to other glycosyltranserases unclear. | TimTech |

| ST078925 (70, 72, 75) | Identified via high-throughput screen. Specificity for OGT compared to other glycosyltranserases unclear. | TimTech |

| UDP-5SGlcNAc; (61, 76) | Effective in vitro inhibitor of OGT but lacks cell permeability. | No |

| 2‐deoxy‐2‐N‐hexanamide‐5‐thio‐d‐glucopyranoside (5SGlcNHex); (77) | Shown to be effective in lowering tissue O-GlcNAc levels following in vivo administration. | No |

| 4-methoxyphenyl 6-acetyl-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1,3-benzoxazole-3-carboxylate (78) | A cell permeable, irreversible inhibitor of OGT. | No |

| 5-thioglucosamine (5SGlcNAc) (76) | The peracetylated form of 5SGlcNAc crosses the cell membrane and converts to UDP-5SGlcNAc, which binds to the active site of OGT. Reduces O-GlcNAc levels in cells in the 10-100-µM range. | No |

AAL2, Agrocybe aegerita GlcNAc-specific lectin; CTD, COOH-terminal domain; GFAT, d-fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine moiety; HBP, hexosamine biosynthesis pathway; IP, immunoprecipitation; NAG, N-acetylglucosamine; O-GlcNAc, O-linked N-acetylglucosamine; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase; RL2, rat liver nuclear pore complex; UDP, uridine diphosphate-azido-modified galactose.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of different approaches for the identification of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine acylated (O-GlcNAcylated) proteins, including galactosyltransferase labeling; immunopurification and chemoenzymatic labeling were combined with LC-MS/MS. Further details are found in TABLE 1. IP, immunoprecipitation; UDP, uridine diphosphate-azido-modified galactose.

Another challenge in the identification and characterization of O-GlcNAcylated proteins is that O-GlcNAc-modified peptides are frequently not detected using traditional collision-induced dissociation mass spectrometry (MS), as O-GlcNAc is very labile and is usually lost during collision-induced fragmentation. The development of electron transfer dissociation (ETD) MS techniques (86,87) significantly enhanced the identification of O-GlcNAc modification sites, since ETD does not usually result in the loss of the O-GlcNAc moiety from the peptide; however, the problems of ion suppression and low stoichiometry remain. To overcome these limitations, it is necessary to enrich the sample for O-GlcNAcylated peptides (88). One approach is to use a traditional immunoprecipitation with a single anti-O-GlcNAc antibody, as described in several studies (36, 89). On the other hand, because of the limitations of epitope specificity, there is a concern that only a subset of O-GlcNAc proteins will be identified. One way to overcome that limitation is to use a combination of antibodies; for example, Lee et al. (90) developed a G5-lectibody resin column that consisted of four different O-GlcNAc antibodies and the lectin wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) (FIGURE 2). Another enrichment approach is chemoenzymatic labeling (38, 44, 91), which involves using uridine diphosphate-azido-modified galactose (UDP-GalNAz) and a mutant galactosyltransferase to tag O-GlcNAc moieties with a reactive azide group. This is followed by the addition of a biotin group attached to a cleavable linker, using a copper-based azide-alkene cycloaddition (84). The resulting modified proteins or peptides can then be affinity purified using an avidin column. A number of different linkers have been described, including a UV-cleavable linker (92,93) and, more recently, a hydrazine-sensitive linker (94). A key advantage of the latter approach is the resulting tag at the O-GlcNAc site allows for more efficient fragmentation. There are several different versions of this technique, and refinements continue to be developed focused on improving the efficiency of the release of proteins/peptides from the avidin column, as well as simplifying the underlying chemistry (43, 95,96).

Compared with most other PTMs, our understanding of how O-GlcNAcylation regulates protein function and cellular physiology remains limited, although our knowledge is rapidly growing. The development of increasingly selective and specific small-molecule inhibitors of OGT and OGA, as summarized in TABLE 1, have helped advance our knowledge of the role of O-GlcNAc in cellular function. These new tools have helped stimulate research in O-GlcNAc biology, as illustrated in FIGURE 3. About 20 years ago, there were less than 20 articles published per year, but this has been steadily increasing, and in 2018, it reached ∼225 (or more than the first 20 years combined). As this becomes a more widely recognized area of biology, it is likely to grow more rapidly, given the increasing appreciation of its importance in regulating key physiological processes combined with its contributions to the development of diverse pathologies. Several thousands of proteins have been identified as O-GlcNAc targets (44), and the number continues to increase, as new techniques are developed. Many new O-GlcNAc sites are identified via high-throughput MS; consequently, the biological function of the modification is often not known. In TABLE 2, we provide a list of some key proteins, divided via cellular location or function, which are validated O-GlcNAc targets in which the specific modification site has been identified. In TABLE 3, the physiological effects of gain or loss of function of OGT and OGA in mammals are summarized.

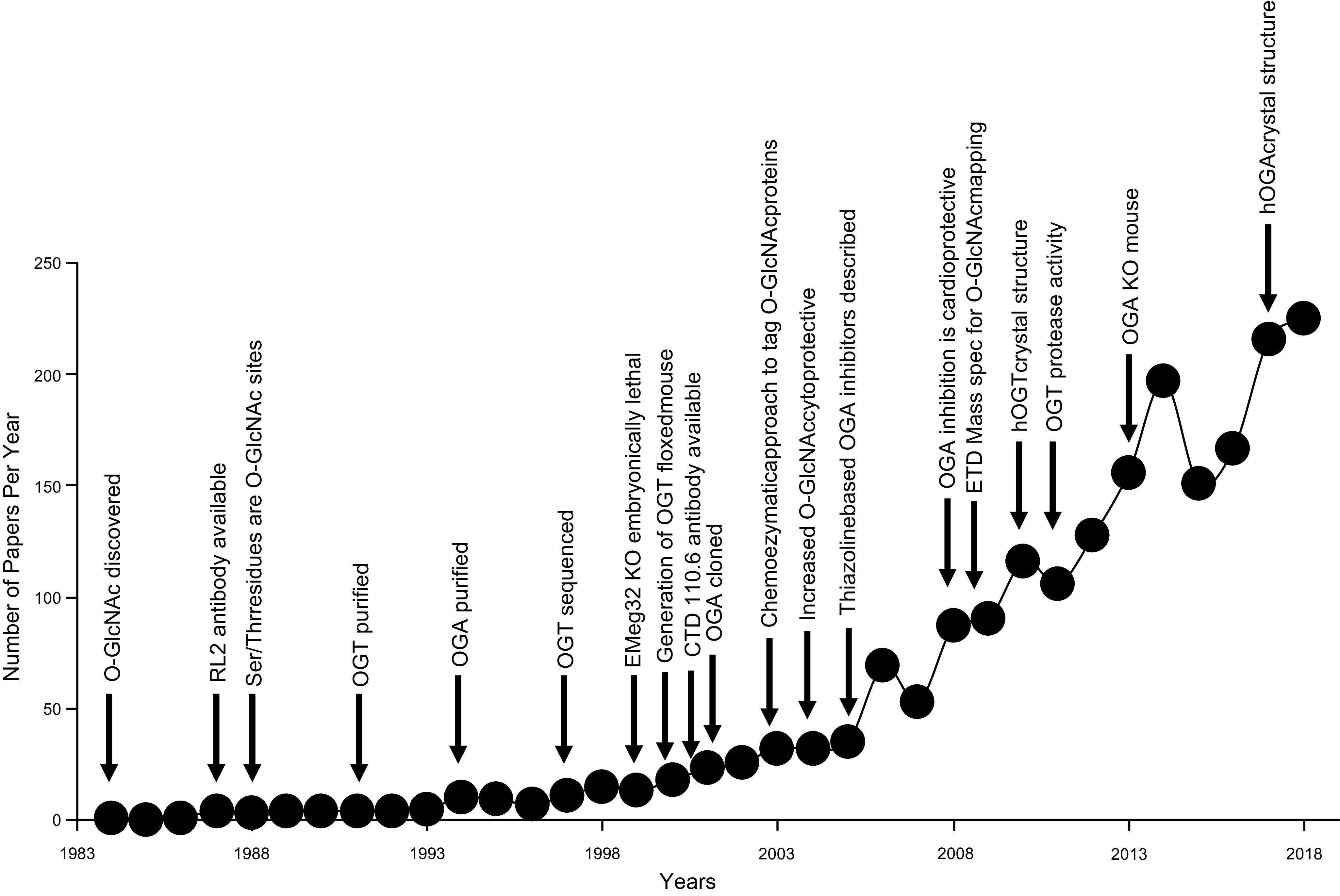

FIGURE 3.

Number of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine acylated (O-GlcNAc) publications by year annotated by key events in O-GlcNAc biology from its initial discovery. Relevant citations are all included in the main text. CTD, COOH-terminal domain; ETD, electron dissociation transfer hOGA, human O-GlcNAcase; hOGT, human O-GlcNAc transferase; KO, knockout; OGA, O-GlcNAcase; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase; RL2, rat liver nuclear pore complex.

Table 2.

List of selected O-GlcNAcylated proteins and their modification sites

| Transcription Factors and Transcriptional Regulators | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Symbol | O-GlcNAc Modification Sites* | Effects on Protein Function | Citations | |

| C/EBPβ | Ser-180, Ser-181 | Regulates both the phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of C/EBPβ. | (97) | |

| cMyc | Thr-58 | Reduces phosphorylation of Ser-62 and Thr-58 and increases protein stability. | (98,99) | |

| CREB | Ser-40 | Represses both basal and activity-dependent transcription. | (100) | |

| ERα | Ser-10, Thr-50, Thr-575 | May regulate protein turnover. | (101,102) | |

| ERβ | Ser-16 | May regulate protein turnover. | (103) | |

| ERRγ | Ser-317, Ser-319 | Enhances receptor activity. | (104) | |

| FOXO1 | Thr-317, Ser-550, Thr-648, Ser-654 | Increases target gene transcription. | (105) | |

| FXR | Ser-62 | Enhances FXR gene expression and protein stability. | (106) | |

| KEAP1 | Ser-104 | O-GlcNAc is required for the efficient ubiquitination and degradation of Nrf2. | (107) | |

| Sp1 | Ser-491, Ser-612, Thr-640, Ser-641, Ser-698, Ser-702 | Inhibits transcriptional activation. | (108,109) | |

| LXRα/β | Ser-49 | Increases transactivation. | (110–112) | |

| Oct4 | Thr-116, Thr-225, Ser-236, Ser-288/889/890, Ser-335, Ser-349, Thr-351, Thr-352, Ser-355, Ser-359 | O-GlcNAc increases transcriptional activity. | (113) | |

| P27 | Ser-2 | Suppresses protein interactions. | (114) | |

| p53 | Ser-139 | Reduces phosphorylation and stabilizes protein. | (115) | |

| Per2 | Ser-566, Ser-580, Ser-653, Ser-662, Ser-668, Ser-671, Thr-734, Thr-965, Ser-983, Thr-1180 | O-GlcNAc increases its suppressor activity. | (116) | |

| PGC-1α | Ser-334, Ser-333 | Enhances stability and upregulated downstream genes. | (117,118) | |

| PPARγ | Thr-54 | Reduces its transcriptional activity. | (119) | |

| SIRT1 | Ser-549 | O-GlcNAcylation increases deacetylase activity, promotes cytoprotection under stress. | (120) | |

|

Insulin Signaling and Other Metabolic Proteins

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Symbol | O-GlcNAc Modification Sites* | Effects on Protein Function | Citations | |

| Akt1/2 | Ser-126, Ser-129, Thr-305, Thr-308, Thr-312, Ser-473 | Decreases phosphorylation and activity. | (121–126) | |

| CRTC2 | Ser-70, Ser-171 | Increased O-GlcNAc leads to nuclear translocation and promotes gluconeogenesis. | (127) | |

| GAPDH | Thr-227 | Increases nuclear translocation. | (128) | |

| GFAT1 | Ser-243 | AMPK phosphorylation of Ser-243 reduced GFAT activity. | (129,130) | |

| GSK3β | Ser-9, Thr-38, Thr-39, Thr-43 | Decreased activity. | (125, 131–133) | |

| G6PDH | Ser-84 | Increases activity. | (134) | |

| IRS1 | Ser-914, Ser-1009, Ser-1036, Ser-1041 | Attenuates insulin-mediated phosphorylation of IRS1. | (135,136) | |

| PDH (E1) | Ser-13, Ser-15, Ser-134, Ser-232 | Higher O-GlcNAc levels associated with greater activity. | (137,138) | |

| PDH (E2) | Ser-7, Ser-15, Ser-239, Ser-411 | Remains to be determined. | (137–139) | |

| PDK2 | Ser-110 | Remains to be determined. | (138) | |

| PFK1 | Ser-529 | O-GlcNAc levels increased in hypoxia and decreases activity. | (140) | |

| PKM2 | Thr-405, Ser-406 | Reduces activity and increases nuclear translocation. | (141) | |

|

Contractile and Cytoskeletal Proteins

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Symbol | O-GlcNAc Modification Sites* | Effects on Protein Function | Citations | |

| αB-crystallin | Thr-170 | Regulates stress induced translocation. | (142,143) | |

| β-Actin (Skeletal Muscle) | Ser-52, Ser-155, Ser-199, Ser-232, Ser-323, Ser-368 | O-GlcNAcylation of Ser-199 may regulate elongation of actin filaments. | (144–147) | |

| Keratin18 | Ser-29, Ser-30, Ser-48 | Increased O-GlcNAc promotes cell survival by activating Akt. | (148,149) | |

| Myosin heavy chain(Skeletal Muscle) | Ser-1097, Ser-1299, Ser-1708, Ser-1920 | Reduced myosin Ca2+ sensitivity. | (145,146) | |

| Myosin heavy 6 (Cardiac) | Thr-35, Thr-60, Ser-172, Ser-179, Ser-196 Ser-392, Ser-622, Ser-626, Ser-644, Ser-645, Ser-749. Ser-880, Ser-1038, Ser-1148, Ser-1189, Ser-1200, Ser-1308, Ser-1336, Ser-1470, Ser-1597, Thr-1600, Thr-1606, Ser-1638, Thr-1697, Ser-1711, Ser-1777, Ser-1838, Ser-1916 | Reduced myosin Ca2+ sensitivity. | (147, 150) | |

| MYL1 | Ser-45, Thr-93, Thr-164 | Remains to be determined. | (147, 150) | |

| MYL2 | Ser-15 | Remains to be determined. | (147) | |

| Synapsin I | Ser-55, Thr-56, Thr-87, Ser-436, Ser-516, Thr-524, Thr-562, and Ser-576 | Regulation of synaptogenesis.O-GlcNAc of Thr-87 regulates localization of synapsin I. | (151,152) | |

| Tau | Ser-208, Ser-238, Ser-400, Ser-692 | Loss of O-GlcNAc induces hyperphosphorylation. | (153–155) | |

| TnI | Ser-150 | Remains to be determined. | (147) | |

| TnT | Ser-190 | Increased O-GlcNAc reduces Ser208 phosphorylation. | (156) | |

| Tropomyosin α1 | Ser-87, Ser-123, Ser-186, Ser-206 | Remains to be determined. | (150) | |

| Oxidative Phosphorylation and Other Mitochondrial Proteins | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Symbol | O-GlcNAc Modification Sites* | Effects on Protein Function | Citations | |

| ATP5A | Ser-76, Thr-432 | Decreased activity. | (138, 157,158) | |

| ATP5B | Ser-106, Ser-128 | Decreased activity. | (138) | |

| DRP1 | Thr-585, Thr-586 | Associated with increased mitochondrial fragmentation and decreased mitochondrial membrane potential. | (159) | |

| Milton | Ser-447, Ser-829, Ser-830, Ser-938 | Attenuates mitochondrial motility. | (160) | |

| NDUFA9 | Ser-156, Ser-230 | Impaired complex activity. | (138, 161) | |

| Prohibitin | Ser-121 | Decreases phosphorylation. | (138,139, 162) | |

| VDAC1 | Thr-2, Ser-240, Ser-260 | Increased O-GlcNAc attenuates mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. | (138, 163) | |

| VDAC2 | Ser-2 | Increased O-GlcNAc contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. | (139, 164) | |

|

Kinases, Phosphatases, and Other Signaling Molecules

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Symbol | O-GlcNAc Modification Sites* | Effects on Protein Function | Citations | |

| CaMKII | Ser-279, Ser-280 | Activates enzyme.Increases NOX2 ROS production | (165)(166) | |

| CaMKIV | Thr-57, Ser-58, Ser-137, Ser-189, Ser-344, Ser-345, Ser-356 | Activates enzyme. | (167) | |

| CDK5 | Ser-46, Thr-245, Thr-246, and Ser-247 | Decreases activity. | (168) | |

| CK2α | Ser-347 | Attenuates interaction with Pin1 and facilitates proteasomal degradation.Reduces CKII phosphorylation decreasing its stability. May also affect substrate selectivity. | (131, 169,170) | |

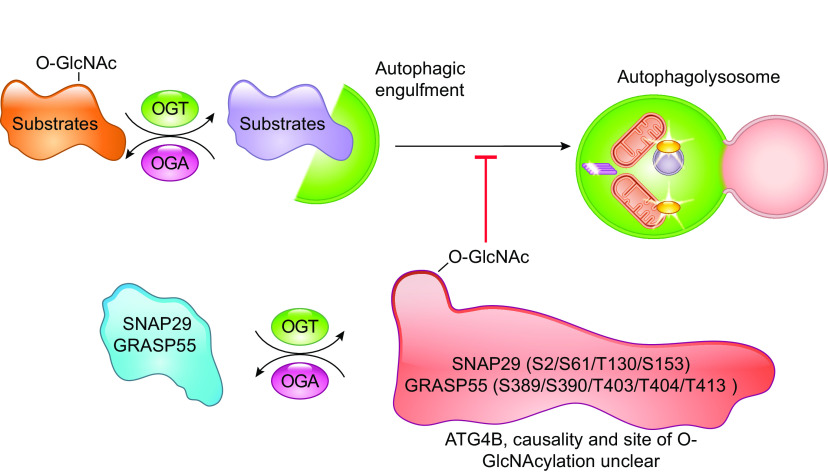

| GRASP55 | Ser-389, Ser-390,Thr-403, Thr-404,Thr-413 | O-GlcNAcylation attenuates autophagy. | (171) | |

| IKKβ | Ser-733 | Increases activity. | (172) | |

| PKC-α, β,δ, ε, θ, ζ | Numerous (see citations for details) | Function not well defined and could be isoform specific. In some cases, likely competes with phosphorylation and decreases enzyme activity. | (173–175) | |

| PTP1B | Ser-104, Ser-201, Ser-386 | Lower O-GlcNAc levels leads to lower phosphatase activity. | (176) | |

| RACK1 | Ser-122 | Promotes stability and interaction with PKCβII. | (177,178) | |

| RIPK3 | Thr-467 | Prevents dimerization and limits inflammation. | (179) | |

| SNAP29 | Ser-2, Ser-61, Thr-130, Ser-153 | O-GlcNAcylation attenuates autophagy. | (180) | |

| ULK1,2 | Thr-613, Thr-635, Thr-726, Thr-754, | O-GlcNAc increases AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of ULK, leading to increased activity. | (92, 181,182) | |

| YAP1 | Ser-109, Thr-241 | Ser-109 O-GlcNAc Disrupts interaction with upstream kinase LATS1. Thr-241 O-GlcNAc increases activity by improving stability. | (183,184) | |

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| Protein Symbol | O-GlcNAc Modification Sites | Effects on Protein Function | Citations | |

| α-synuclein | Thr-64, Thr-72, Thr-75, Thr-81, Ser-87 | Increased O-GlcNAcylation associated with decrease in aggregation; however, this has primarily been identified in in vitro studies. | (185) | |

| β-catenin | Ser-23, Thr-40, Thr-41, Thr-112 | Promotes its recruitment to the plasma membrane and its binding to E-cadherin and regulates stability. | (186,187) | |

| CREB-binding protein | Ser-147, Ser-2360 | Remains to be determined. | (188) | |

| eIF4A | Ser-322, Ser-323 | Regulates formation of translation initiation complex. | (189) | |

| eNOS | Ser-1177 | Impairs activity. | (190) | |

| FNIP1 | Ser-938 | Attenuates phosphorylation and increases proteasomal degradation. | (191) | |

| HCF-1 | Thr-490, Ser-569, Ser-620, Ser-622, Ser-623, Thr-625, Ser-685, Thr-726, Thr-779 Thr-801, Thr-861, Thr-1143, Thr-1273, Thr-1335, Thr-1743, Thr-1238, Thr-1241 | O-GlcNAcylation is a signal for its proteolytic processing | (188, 192) | |

| HSP90 | Ser-434, Ser-452, Ser-461 | Remains to be determined | (193) | |

| PLB | Ser-16 | Inhibits phosphorylation. | (194) | |

| TAB1 | Ser-395 | Required for full activation of TAK1 | (81) | |

| TAB2 | Ser-166, Ser-350, Ser-354, Thr-456 | May control the activity of IL-1 signaling pathway | (95, 188) | |

| TAB3 | Ser-408 | Mediates cell migration via activation of NF-κB, | (195) | |

The proteins included in this table were selected primarily on the basis of their inclusion within the main body of the article. In addition to the citations listed in Table 2, other resources that were used included PhosphoSite Plus, www.phosphosite.org (196), Dias et al. (197), Ma et al. (138,139). CKII, casein kinase II; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; GFAT, l-glutamine: d-fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase; IRS1, insulin receptor substrate 1; LATS1, large tumor suppressor kinase 1; NOX2, NADPH phagocyte oxidase isoform; Nrf2, nuclear factor E2–related factor-2; ROS, reactive oxygen species; O-GlcNAc, O-linked N-acetylglucosamine; TAK1, transforming growth factor-β activated kinase 1; ULK, Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1.

Table 3.

Physiological roles of OGT and OGA in mammals

| Genotype | Phenotype | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Human | ||

| Ogt human mutation L254F or E1974H | Intellectual disability. | (26,27, 29, 198) |

| Rat | ||

| Oga Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat mutation | Diabetes. | (199) |

| Systemic inhibition of OGA by thiamet G in wildtype rat | Impaired novel place recognition. | (200) |

| Mouse | ||

| AgRP-cre::Ogtf/f | Ogt ablation in AgRP neurons. Obese due to lack of browning of white fat. | (201) |

| CaMKII-cre::Ogtf/f | Constitutive Ogt ablation in forebrain neurons. Loss of body and brain weight and significant neurodegeneration almost as early as birth, decreased lifespan. | (202) |

| CaMKII-creER::Ogtf/f | Inducible Ogt ablation in forebrain neurons. Obese due to overeating after acute deletion of Ogt. | (203) |

| γ-F-crystallin-rtTA:: dnOGA | OGA overexpression in the eye. Premature cataracts. | (204) |

| MCK-rtTA::dnOGA | OGA overexpression in the skeletal muscle. Skeletal muscle atrophy. | (205) |

| MMTV-cre::Ogaf/f | Constitutive Oga ablation in mammary gland. Obesity, in females. | (17) |

| MHC-cre::Ogtf/f | Constitutive Ogt ablation in cardiomyocytes. Postnatal lethality, dilated hearts, and signs of heart failure. | (206) |

| Oga -/- | Germline knockout. Perinatal lethality. | (17, 207) |

| Oga +/- | Germline heterozygote. Lean not due to overeating or higher energy expenditure, associated with higher RER. | (207) |

| Ogt -/- | Germline knockout. Embryonic stem cell lethality. | (16, 208) |

| Systemic inhibition of OGA by thiamet G in Aβ and Tau overexpression models | Decrease pathology. | (60, 209) |

AgRP, Agouti-related protein.

In the following sections, we have provided an overview of our current understanding of the regulation of O-GlcNAcylation, its role in regulating cellular physiology, as well as its potential role in pathophysiology of diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

2. REGULATION OF O-GlcNACYLATION

2.1. Hexosamine Biosynthesis Pathway

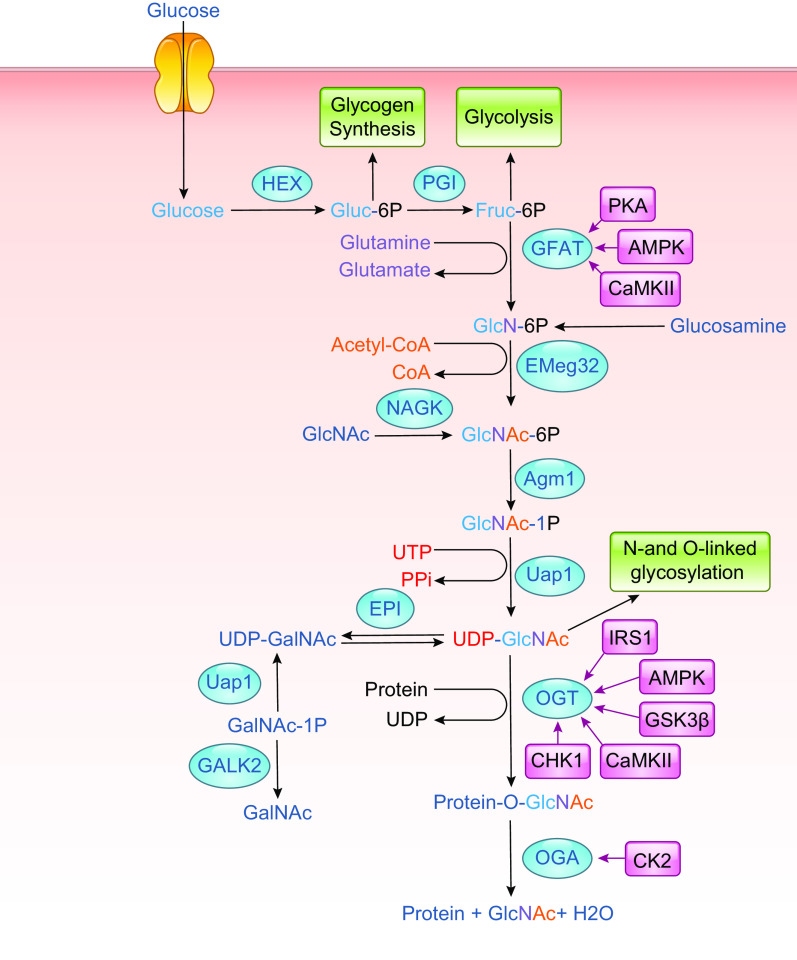

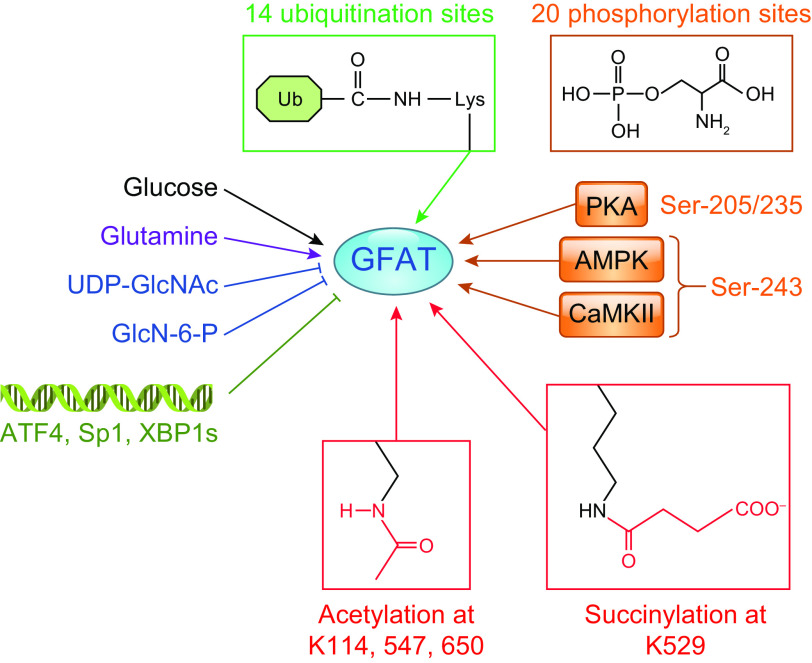

Uridine diphosphate-GlcNAc (UDP-GlcNAc) is the common substrate for all amino sugars involved in the synthesis of glycoproteins and proteoglycans. As the end product of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP), UDP-GlcNAc integrates multiple metabolic pathways and has long been considered an important nutrient signaling pathway partially regulated by substrate availability (FIGURE 4) (210–212). l-glutamine: d-fructose-6-phosphate transaminase (GFPT, EC 2.6.1.16), often referred to as l-glutamine: d-fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT), is the rate limiting enzyme of the HBP, catalyzing the transfer of the amide group from glutamine to fructose 6-phosphate, leading to the synthesis of glucosamine 6-phosphate (213). In mice and humans, there are two different isoforms of GFAT (GFAT1, GFAT2) encoded by two different genes, located on different chromosomes, and each isoform has markedly different tissue distribution (213, 214). In tissue from the central nervous system, GFAT2 expression predominates over GFAT1, whereas, in most other tissues, GFAT1 is more highly expressed (214). A splice variant of GFAT1, known as GFAT1Alt, has been identified, and it appears to be predominantly expressed in skeletal muscle and exhibits a higher Km for fructose-6-phosphate and a lower Ki for UDP-GlcNAc than those for GFAT1 (213, 215). In mammals, GFAT exists as a tetramer, and its activity is highly dependent on the availability of both glutamine and glucose (213). Both glucosamine-6-phosphate and UDP-GlcNAc are potent allosteric inhibitors of mammalian GFAT (FIGURE 5) (214). Up to 20 different phosphorylation sites have been identified in GFAT; however, the responsible kinases and function(s) of the majority of them are unknown. GFAT1 and GFAT2 are regulated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) phosphorylation on Ser-205 and Ser-235, respectively (213, 216,217); both AMPK and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) II phosphorylate GFAT1 at Ser-243 (FIGURE 5) (129, 218). There are contradictory reports on the effects of phosphorylation on GFAT activity, which may be due to isoform-specific differences. In the heart, a number of studies indicate that AMPK phosphorylation of GFAT1 reduces its activity (219); however, it remains to be determined whether this is also the case in other cells and tissues. GFAT is also transcriptionally regulated (FIGURE 5) by specificity protein 1 (Sp1) (220) and activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) (221). Multiple GFAT1 missense mutations leading to loss of activity and reduced O-GlcNAc levels have been linked to neuromuscular transmission defects (222). Despite reports of several putative GFAT inhibitors (213, 223, 224), the regulation of HBP flux via small-molecule inhibitors of GFAT has been limited to the glutamine analogs azaserine and 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON), which are limited because of their lack of specificity (TABLE 1).

FIGURE 4.

Schematic of UDP-GlcNAc and O-GlcNAc synthesis. Glucose enters the cell via the glucose transporter system where it is rapidly phosphorylated by hexokinase (HK) and converted to fructose-6-phosphate by phosphoglucoseisomerase (PGI). Fructose-6-phosphate is subsequently metabolized to glucosamine-6-phosphate by l-Glutamine: d-fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT), which requires glutamine. Glucosamine-6-phosphate is converted to N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate by glucosamine 6-phosphate N-acetyltransferase (Emeg32), utilizing acetyl-CoA. Phosphoacetylglucosamine mutase (Agm1) converts N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate to N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate. The synthesis of uridine-diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) is catalyzed by UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase (Uap1), which consumes uridine triphosphate (UTP). UDP-GlcNAc is the substrate for (O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) leading to the formation of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc)-modified proteins. β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (OGA) catalyzes the removal of O-GlcNAc from the proteins. GlcNAc can reenter the HBP via two salvage pathways: 1) via N-acetylglucosamine kinase (NAGK) to generate N-acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate and 2) involving the conversion by N-acetylgalactosamine kinase (GALK2) of N-acetyl-galactosamine to N-acetylgalactosamine 1-phosphate and UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine, with subsequent conversion by an epimerase to UDP-GlcNAc. Glucosamine, which enters the cell via the glucose transport system and can be phosphorylated by hexokinase (HK) to form glucosamine 6-phosphate thereby bypassing GFAT. The kinases that have been identified as regulating GFAT, OGT, and OGA are indicated; additional details may be found in the text (see FIGURE 6 and TABLE 3). AMPK, AMPK-activated protein kinase; CaMKII, calcium/calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM) dependent protein kinase II; CHK1, checkpoint kinase-1; CK2, casein kinase 2; EPI, epimerase; GalNAc, glucosamine fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase; GFAT, glucosamine fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; GlcNAc-1P, N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3b; HEX, hexokinase; IRS1, insulin receptor substrate-1; PPi, pyrophosphate; UDP-GalNAc, uridine diphosphate N-acetylgalactosamine.

FIGURE 5.

Regulation of glucosamine fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT). GFAT activity is regulated at several levels including substrate availability, feedback inhibition by uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) and glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN-6-P), as well as post-translational modifications by phosphorylation, acetylation, succinylation, and ubiquitination. The only kinases that have been identified as phosphorylating GFAT are PKA, AMPK, and calcium/calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM) dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). Sp1, ATF4, and XBP1s have been shown to regulate GFAT at the transcriptional level. The database phosphosite.org and the citations contained therein were used to identify known posttranslational modification sites of GFAT (196). ATF4, activating transcription factor 4; Lys, lysine; Sp1, specificity protein 1; XBP1s, X-box binding protein 1.

Glucosamine 6-phosphate N-acetyltransferase (GNPNAT, GNA1), known as Emeg32 in mice, uses acetyl-CoA to convert glucosamine 6-phosphate to N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate (225), which is subsequently isomerized by phosphoglucomutase (PGM) to N-acetylglucosamine-l-phosphate. The final step in the HBP is conversion of N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate to UDP-GlcNAc, which is catalyzed by UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase (UAP1), also known as UDP-N-acetylhexosamine pyrophosphorylase (226). In addition to its de novo synthesis, UDP-GlcNAc can also be generated by two salvage pathways (FIGURE 4) (227). In one pathway, GlcNAc is phosphorylated by N-acetylglucosamine kinase to generate N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate. A second pathway involves the conversion of N-acetyl-galactosamine to N-acetylgalactosamine-1-phosphate and UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine, with subsequent conversion by an epimerase to UDP-GlcNAc (FIGURE 4). The relative contribution of the salvage pathways to total UDP-GlcNAc synthesis is not known. That deletion of GNPNAT gene is embryonically lethal (228) suggests that de novo synthesis is likely the predominant pathway. On the other hand, while deletion of EMeg32 substantially decreased UDP-GlcNAc levels, they were not eliminated. Further, the loss of EMeg32 did not lead to major changes in N- and O-glycosylation, whereas, O-GlcNAc levels were markedly suppressed, suggesting that salvage pathways were sufficient to maintain ER- and Golgi-mediated glycosylation, but not O-GlcNAcylation (228). Alternatively, under conditions in which UDP-GlcNAc levels are limiting, N- and O-glycosylation are prioritized over O-GlcNAcylation.

It is frequently stated that 2–5% of glucose entering a cell is metabolized via GFAT and the HBP. The origin of this statement is from a study using cultured adipocytes in which metabolic flux through glycolysis and the HBP was not directly measured, and the fraction of glucose metabolized by the HBP was inferred from other measurements (46). Moreover, energy metabolism, including glycolysis, varies widely from quiescent cells in culture to high-energy demands of the heart and brain. Consequently, the relative flux of glucose via glycolysis and HBP will also vary widely. There are very few studies that have directly measured the flux of glucose via the HBP, relative to other glucose-utilizing pathways, using radio- or stable-isotope techniques, either in cell culture or intact organs. In 2017, Gibb et al. (229), using 13C6-glucose labeling in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes, concluded that glucose is metabolized more by the HBP than the pentose phosphate pathway, suggesting that glucose utilization via the HBP could be considerably greater than previous estimates; however, this was under the low-energy demands of cell culture, as well as being in neonatal cardiomyocytes which would have different energetic demands from those in an adult heart. Olsen et al. (230) have recently developed an LC/MS technique using 13C-labeled substrates to measure the rate of glucose metabolism via the HBP at the same time as glycolytic flux. In the isolated perfused working heart, an HBP flux of ∼2.5 nmol/g protein/min was measured, which represented 0.003–0.006% of the glycolytic flux. This is several orders of magnitude lower than earlier estimates, most likely because of the high metabolic rate of the heart. Moreover, when increasing glucose concentration from 5 to 25 mM, changes in HBP flux relative to glycolysis occurred as a result of changes in glycolytic, not HBP, flux rates. This illustrates the limitation of evaluating HBP flux as a fraction of glycolysis, as well as the assumption that HBP flux will be similar across biological systems with widely varying metabolic demands. While, much remains to be understood about of the regulation of HBP, the implementation of new techniques will enable direct measures of HBP flux in diverse biological systems.

2.2. O-GlcNAc Transferase

O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT; uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine:polypeptide β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase; EC 2.4.1.255) is a soluble glycosyltransferase primarily located in the cytoplasm and nucleus, which is responsible for using UDP-GlcNAc to modify proteins with O-GlcNAc (211, 231–234). OGT is located on the X-chromosome and encodes a multidomain protein containing multiple tetratriopeptide repeats (TPRs) in the NH2-terminal domain and two catalytic domains in the COOH-terminal region (FIGURE 6A) (211, 231–234). OGT is highly conserved, across all metazoans, and with the exception of zebrafish (237, 238), a single gene encodes OGT. Alternative splicing results in three mammalian isoforms of OGT, which differ primarily by the number of TPRs. A form of OGT, epidermal growth factor domain-specific OGT (EOGT), has also been identified in the ER, but it shares little homology with other forms of OGT. In contrast to OGT, it can also elongate O-GlcNAc into complex glycans (239), as reviewed in detail elsewhere (240, 241).

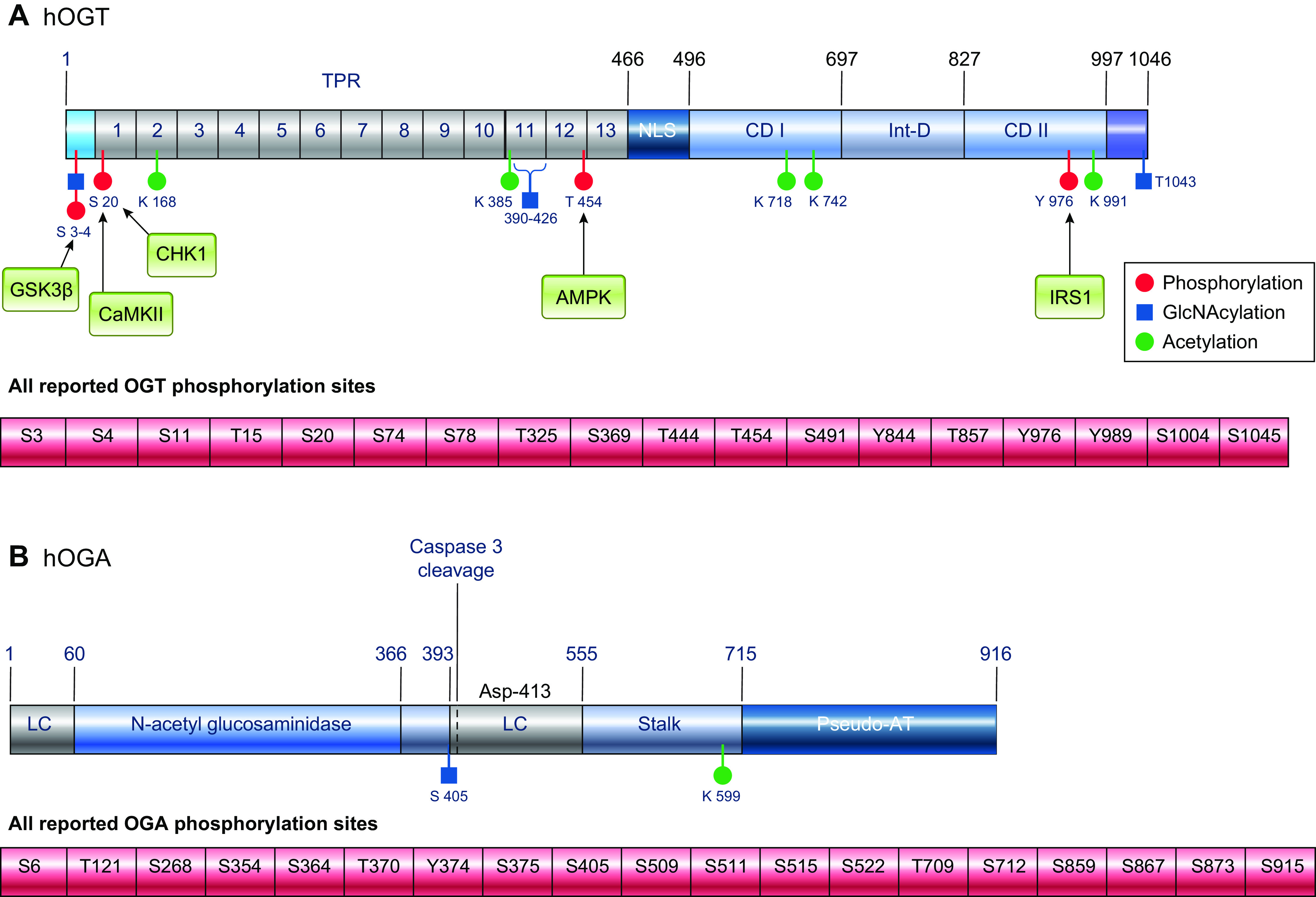

FIGURE 6.

Structure and posttranslational modifications of human OGT (A) and OGA (B). Phosphorylation sites with identified kinases are shown as red circles, and all known phosphorylation sites are listed below the figures. O-GlcNAc sites are shown as blue squares, and acetylation sites are shown as green circles. AT, acetyl transferase; CaMKII, calcium/calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM) dependent protein kinase II; CD, catalytic domain; CHK1, checkpoint kinase-1; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; hOGT, human O-GlcNAc transferase; hOGA, huma O-GlcNAcase; Int-D, intervening domain; IRS1, insulin receptor substrate-1; LC, low complexity region; NLS, nuclear localization sequence; TPR, tetratricopeptide repeats. The databases https://www.phosphosite.org and http://www.phosphonet.ca/, and the citations contained therein were used to for known phosphorylation sites and acetylation modification sites(196). Citations for sites where kinases have been identified are included in the text; additional resources include Lundby, et al. (235), Levine and Walker (232) and Roth et al. (236). Other PTMs not shown include ubiquitination and sumoylation.

The full length or nucleocytoplasmic OGT (ncOGT; 110 kDa) and short OGT (sOGT; 78 kDa) have up to 13.5 and 4 TPRs, respectively; the precise number of TPRs is species specific (232). The mitochondrial OGT (mOGT; 90 kDa) has a mitochondrial targeting sequence at the NH2 terminus of the protein and 9 TPRs. All three OGT isoforms have the same two catalytic domains, as well as a putative phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3)-binding domain (242); however, studies of the crystal structure of human OGT-UDP-peptide complex were unable to confirm the presence of the PIP3 domain (90). OGT is a member of the GT-B glycosyltransferase superfamily, and it is the only glycosyl transferase to have a ∼120 amino acid sequence in the middle of the catalytic domain, known as the intervening domain (Int-D) (232, 234, 243). The function of this region of the protein remains unclear, although it contains a large number of basic residues, suggesting contacts with negatively charged partners, which may affect cellular localization or protein-protein interactions (232, 243).

The catalytic domain of OGT represents less than half of the total molecular weight of the protein with the remainder of the protein primarily consisting of the TPRs (234). TPRs comprise 34 amino acid motifs clustered in repeats that form α-helical superspirals and have been proposed to play a key role in determining OGT interactions with target substrate proteins (234, 244). The importance of the TPR domain in regulating OGT substrate selectivity was demonstrated by the observation that modification of only two aspartate residues in the TPR substantially changed OGT substrate preference (245). Although most OGT substrates require the presence of the TPR domains for O-GlcNAcylation to occur, some proteins only interact with the catalytic region (131, 232, 234). OGT exists as a homodimer (243, 244, 246), and the TPR regions are also required for dimerization; however, in vitro disruption of this interaction did not change OGT activity (247). The function of OGT dimerization is unclear; however, it could serve to stabilize interactions with specific substrates. For example, mutations in the TPR 6–7 region prevent OGT dimerization, as well as reduce O-GlcNAc levels of nuclear pore glycoprotein p62 (Nup62) (244).

A definitive consensus sequence for O-GlcNAcylation has not been identified; consequently, although our knowledge of OGT structure and its molecular interactions with substrates has improved, our knowledge of the regulation of OGT function and the mechanisms underlying its substrate specificity remains limited (231). Reports demonstrating that interactions between UDP-GlcNAc and the peptide play a role in orientation of the peptide relative to the active site suggest that the active site contributes to substrate selection (248). Moreover, preference by OGT for Ser/Thr residues that have prolines and branched-chain amino acids in close proximity, resulting in an extended peptide orientation, also suggests that the active site imposes some degree of sequence constraint and, thus, substrate selection (249). However, perhaps the most widely accepted view is that OGT substrate selection is largely determined by binding to the TPR domains. This is supported by the fact that the TPR domains are essential for O-GlcNAcylation of most proteins, as well as the fact that specific substrates interact with specific TPR regions. For example, in brain tissue, ataxin-10 (Atx-10) binds to TPRs 6–8 (246), whereas mSIN3A, ten-eleven translocation (TET) 2/3, and trafficking kinesin protein 1 (TRAK1) all require TPRs 1–6 (232). Moreover, mutations of just two aspartate residues in the TPR domain changed OGT activity as well as target specificity (245). Structural studies have revealed a hinge region around TPRs 12–13, which could influence the access of protein substrates to the active site of OGT (232, 234). There is also evidence that under some conditions, sOGT can act as a negative regulator of ncOGT (233, 246). The importance of the TPR domain is reflected in the observations that missense mutations in this region result in decreased OGT function and neurodevelopmental abnormalities (29, 250).

OGT activity and substrate recognition can also be regulated by phosphorylation of OGT on Ser, Thr, and tyrosine (Tyr) residues (233). Almost 20 different phosphorylation sites have been reported on OGT, many identified by large-scale proteomic studies (FIGURE 6A). Although the function of many of these sites remains unknown, as do the kinase(s) responsible for their phosphorylation, a few have been characterized. For example, insulin increases Tyr phosphorylation of OGT via activation of the insulin receptor (IR), resulting in increased OGT activity (251). Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β phosphorylates OGT on Ser-3/4, leading to increased OGT activity (116), and AMPK phosphorylates Thr-444, resulting in changes in subcellular localization and substrate binding targets (252). In addition, OGT is phosphorylated on Ser-20 by checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1), leading to stabilization of OGT, which is required for cytokinesis (253). Ser-20 on OGT is also a target for CaMKII, which increases its activity (181). O-GlcNAcylation of Ser-389, located in the TPR domain regulates OGT nuclear localization (254). Serines 3 and 4 on OGT are also sites of O-GlcNAcylation (116); however, the function of this modification remains to be determined. Recent work that has focused on some of these phosphorylation sites has identified that in sOGT, mutation of either Thr-12 or Ser-56 to an alanine significantly altered substrate binding by over 500 proteins (255). OGT is also acetylated on multiple residues (FIGURE 6A) (235). While the effects of this modification are not known, the fact that two of the sites occur within one of the catalytic domains suggests they could regulate OGT activity in some manner.

Targeting of specific proteins by OGT can also occur via its interaction with adaptor or scaffold proteins, which recruit substrates on OGT. For example, in the liver during fasting host cell factor 1 (HCF1) targets OGT to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), where increased O-GlcNAcylation increases PGC-1α stability and upregulates gluconeogenic genes (118). Other such interactions include p38 MAPK, which recruits OGT to neurofilament-heavy polypeptide (NFH) (256), REV-ERBα, which prevents OGT degradation (65), and OGA, which increases interactions between OGT and pyruvate kinase isoform M2 (PKM2) (257). The potential for an OGT-OGA interaction raises the possibility of an “O-GlcNAczyme” complex, which would be consistent with rapid and reversible changes in O-GlcNAcylation (258). Insulin treatment results in translocation of OGT from the nucleus to the cytosol and plasma membrane, and changes in nutrient availability also lead to redistribution of OGT between the nucleus and cytosol (242, 251). The three OGT isoforms also exhibit differences in their subcellular localization, and along with differences in the TPR regions between the isoforms, different proteome subsets can result; however, this has only been demonstrated with in vitro studies (169).

In addition to its role as a glycosyl transferase, OGT also exhibits protease activity, although, to date, only one proteolytic substrate, the transcriptional coregulator HCF1, has been identified (259, 260). To fully function as a coregulator HCF1 is required to undergo proteolytic cleavage; however, the mechanism by which this occurred remained elusive until 2011 when two reports demonstrated that OGT played a key role in this process (259, 260). These studies demonstrated that both UDP-GlcNAc and OGT were required for HCF1 proteolysis, consistent with the notion that O-glycosylation of HCF1 was necessary. It was initially thought that OGT had a specific protease active site; however, subsequent studies demonstrated that the COOH-terminal of HCF1 binds to the TPR domain of OGT, and the cleavage region in the glycosyltransferase active site was similar to that for regular glycosylation substrates (261). Moreover, these studies also showed that UDP-5SGlcNAc, which binds to the OGT-active site in the same manner as UDP-GlcNAc, but is resistant to glycosyltransferase, inhibited HCF1 proteolysis. The role of OGT mediated cleavage of HCF1 remains unclear; however, it could represent a link between cellular metabolism and the regulation of cell cycle, which is supported by reports that the OGT/HCF1 complex itself is an important regulator of glucose metabolism (118).

2.3. O-GlcNAcase

O-GlcNAcase (OGA, EC 3.2.1.169) is a hexosaminidase that was first characterized in 1994 by Dong and Hart (11) following purification from rat spleen; it has also been referred to as NCOAT, nuclear cytoplasmic O-GlcNAcase and acetyltransferase (262), GCA (263), MEA5, and MGEA5 (264). Dong and Hart (11) demonstrated that it was distinct from lysosomal hexosaminidases by virtue of its subcellular localization to the cytosol and nucleus, its neutral pH optimum, and its selectivity for GlcNAc over GalNAc. Subsequent sequence identification and cloning demonstrated that OGA was identical to a previously identified protein, MGEA5, found in meningioma patients (264). The human OGA gene is located on chromosome 10 and encodes a protein with an NH2-terminal glycosyl hydrolase domain and a COOH-terminal domain that demonstrates sequence homology to histone acetyl transferase (AT) proteins (FIGURE 6B). The glycosyl hydrolase domain has two low-complexity or disordered regions [i.e., repeats of single amino acids or short amino acid motifs (265)], on either side. The larger low-complexity region is followed by the stalk domain, which connects to the COOH-terminal domain (231, 266). Between the catalytic domain and the COOH-terminal region is a noncanonical caspase cleavage site (267). It has been reported that OGA exhibited AT activity (199, 268); however, this has not been replicated by others (269). Recent structural studies found that human OGA (hOGA) lacks the residues necessary for binding to acetyl-CoA and described this region as a “catalytically incompetent pseudo-AT domain” (270). Alternative splicing results in the generation of a short OGA (sOGA), which lacks the pseudo-AT region and has a different 15-amino acid COOH-terminal region (271). sOGA has lower hexosaminidase activity than hOGA in vitro (56, 272) and appears primarily localized to the surface of lipid droplets (273), although its specific function remains to be elucidated.

For many years, full-length hOGA proved resistant to crystallization, consequently, most of the initial structural and mechanistic information were derived from bacterial homologs of OGA (274). In 2017, three independent studies reported the crystal structure of hOGA using different, catalytically functional, truncated versions of the protein (236, 275, 276). A key and unexpected finding in all three studies was that hOGA formed an obligate homodimer in which the stalk domain of one monomer is positioned over the catalytic site of the other monomer (266). One consequence of this arrangement is the creation of a substrate binding site, comprising conserved hydrophobic residues, which supports the notion that the dimer is the active form of OGA. Further structural analysis suggests OGA may preferentially remove O-GlcNAc from certain sites, suggesting that OGA may be an equal partner with OGT in regulating O-GlcNAc turnover (277). Moreover, it has also been reported that a number of specific residues on OGA contribute to its interactions with different peptide substrates, which has implications for differential regulation of O-GlcNAcylation on different proteins (278,279). While the active site of OGA is now better characterized than ever before, other regions, including the low-complexity region and the pseudo-AT domain remain poorly understood (266).

Similar to OGT, OGA is also subject to both phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation. At least 20 different Ser, Thr, and Tyr phosphorylation sites have been mapped by MS in both the glycosyl hydrolase and pseudo-HAT domains (FIGURE 6B); however, the effects of these modifications on OGA activity have not been determined. Interestingly, the Ser-405 O-GlcNAcylation site on OGA, is in the central low-complexity region, which is also the region where OGA interacts with OGT (266). Thus, O-GlcNAcylation of this residue plays a role in the regulation of the interaction between OGT and OGA. OGA is also acetylated in the stalk domain at Lys-599 (235).

2.4. Maintenance of O-GlcNAc Homeostasis

Changes in cellular O-GlcNAc levels occur in response to a diverse array of physiological and pathological stimuli, and dysregulation of O-GlcNAc homeostasis has been linked to a wide array of diseases, as discussed in detail later. Deletion of the OGT gene is embryonically lethal (208), and in cell culture, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) die around 4–5 days after OGT is knocked out (280). Although OGA knockout mice survive to birth, the majority die before weaning (17). Chronic increases in O-GlcNAc levels induced by overexpression of a dominant negative OGA (dnOGA) in a tissue-specific manner results in apoptosis in skeletal muscle (205) and altered metabolism in the heart (281). Therefore, it is evident that maintenance of O-GlcNAc homeostasis is essential for the normal physiological function of cells and tissues. This has led to the concept that there is an optimal range of O-GlcNAcylation that supports normal physiological processes and that outside that range, either too high or too low, cellular dysfunction results. Consequently, it has been proposed that to keep within this optimal range, OGT and OGA work together to form a “buffering” system that can respond to moderate changes in O-GlcNAcylation (257).

The prevailing wisdom for many years was that the primary mechanism regulating cellular O-GlcNAc levels was nutrient availability, so that under conditions of nutrient excess, such as hyperglycemia, O-GlcNAc levels increased, and if glucose levels dropped O-GlcNAc levels would decrease. This concept is consistent with the fact that glucosamine, which bypasses GFAT, leads to uncontrolled synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc and increased O-GlcNAc levels (24, 271, 282, 283). This also enables glucosamine to be used pharmacologically to increase UDP-GlcNAc synthesis and O-GlcNAc levels. Acute changes in glucose availability either by increasing exogenous glucose or via insulin-stimulated increases in glucose uptake can have little or no effect on cellular O-GlcNAc levels (284). This is also consistent with the report that a five-fold increase in glucose had no effect on HBP flux in the isolated perfused heart (230). However, such responses likely vary greatly, depending on cell type and duration of treatments (285). In addition, OGT activity is very sensitive to UDP-GlcNAc concentrations, exhibiting multiple apparent Km values for UDP-GlcNAc under varying UDP-GlcNAc concentrations (247). Consequently, changes in UDP-GlcNAc concentrations can directly influence global as well as regional OGT activities and O-GlcNAc levels.

However, while nutrient availability as a regulatory mechanism is a valuable concept, it does not address the mechanisms that underlie widely differing rates of changes in O-GlcNAcylation that occur in response to different stimuli. For example, depolarization of neuroblastoma cells dramatically increased OGT activity, reaching a peak within 1 min, leading to increased O-GlcNAc levels (286), and stimulation of human neutrophils leads to an approximately five fold increase in O-GlcNAc within 30 s, returning to normal levels over the next 5–10 min (287). On the other hand, stress, such as ischemia (288) or heat shock occur over periods of minutes to hours, induced increases in O-GlcNAc levels (289). Conversely, in certain disease states, such as cancer (21, 290), diabetes (283, 290), or cardiac hypertrophy (291,292), O-GlcNAc levels are chronically elevated, and the mechanisms that lead to this resetting of steady-state O-GlcNAc levels outside of the normal range remains poorly understood (293). As discussed above, GFAT, OGT, and OGA are all modified by phosphorylation, indicating that these posttranslational modifications may contribute to the dynamic regulation of O-GlcNAcylation.

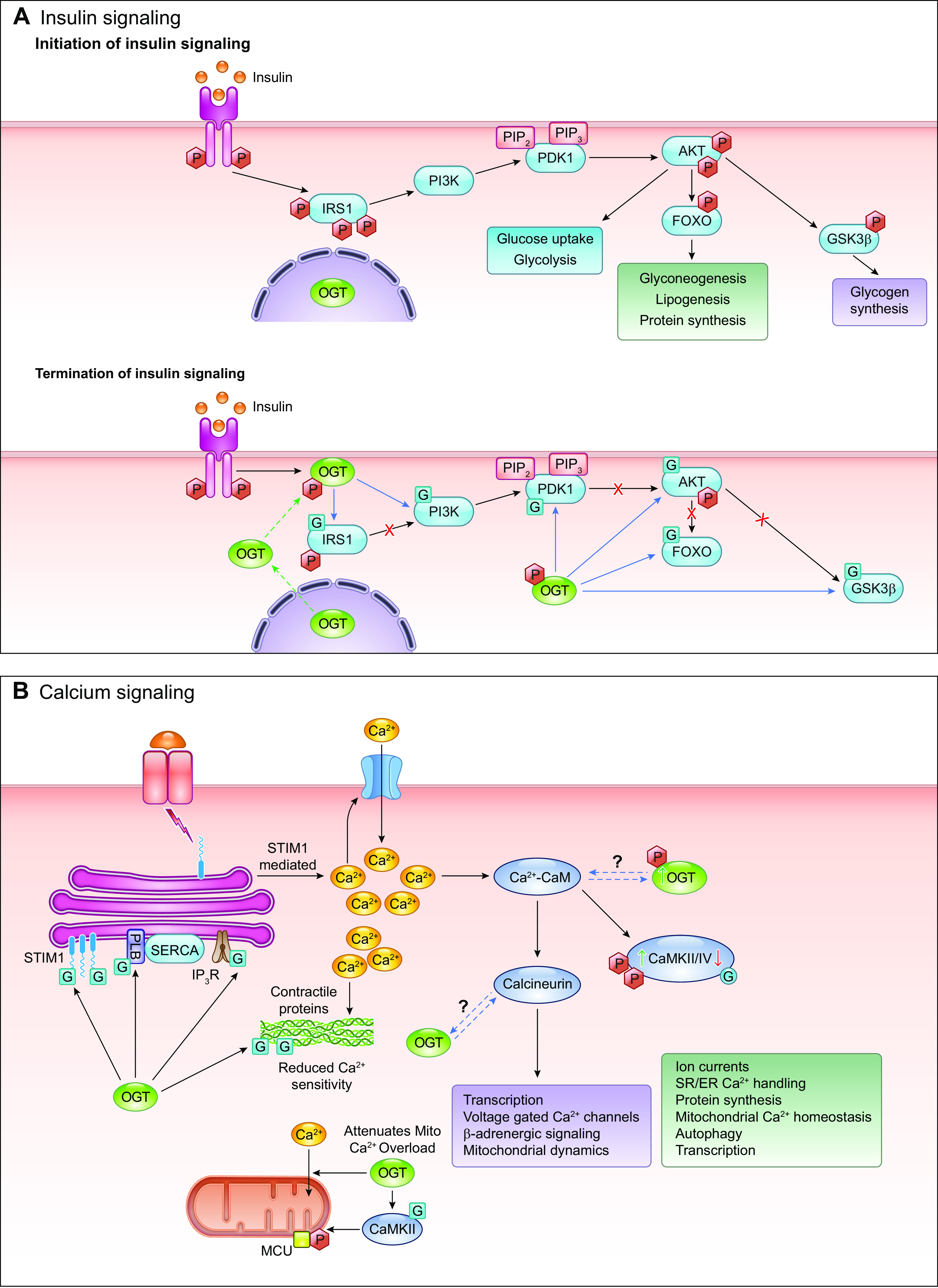

Given that HBP flux and O-GlcNAc levels are modulated, in part, by nutrient availability, it is perhaps not surprising that O-GlcNAc levels can also be regulated by nutrient-regulating hormones. Insulin is probably the most studied of these, and it has been shown that insulin treatment recruits OGT from the nucleus to the plasma membrane, where it is phosphorylated by the IR (242, 251, 294). This phosphorylation increases OGT activity and leads to O-GlcNAcylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS1) and AKT, resulting in attenuation of insulin signaling. Treatment of HepG2 cells with the adipokine leptin resulted in an approximately twofold increase in overall O-GlcNAc levels within 15 min with parallel increases in GFAT protein levels (295). However, the mechanism by which leptin stimulated GFAT expression and O-GlcNAc levels was not identified. Ghrelin, a hormone that is released in response to fasting, increases O-GlcNAc levels in hypothalamic appetite-stimulating agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons, leading to their increased firing rate (201). In the liver, glucagon, which increases in response to fasting, increased OGT phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc levels in a CaMKII-dependent manner (181).

In addition to nutrient-dependent hormones, G protein-coupled receptor agonists have also been shown to increase cellular O-GlcNAc levels. For example, activation of the endothelin (ET)A receptor with ET-1 resulted in a time-dependent increase in O-GlcNAc levels in vascular cells, and the subsequent downstream signaling by ET-1 was dependent on the increase in O-GlcNAc levels (296, 297). Phenylephrine (PE), primarily an α-receptor agonist, also increased O-GlcNAc levels in cardiomyocytes, and the increase in O-GlcNAc was required for subsequent activation of PE-mediated signaling pathways (298, 299). One explanation for PE-dependent increases in O-GlcNAc levels was an increase in GFAT expression (298, 299). Another study suggested that the increase was mediated by the Ca2+ dependent CaMKII/calcineurin pathway (298).

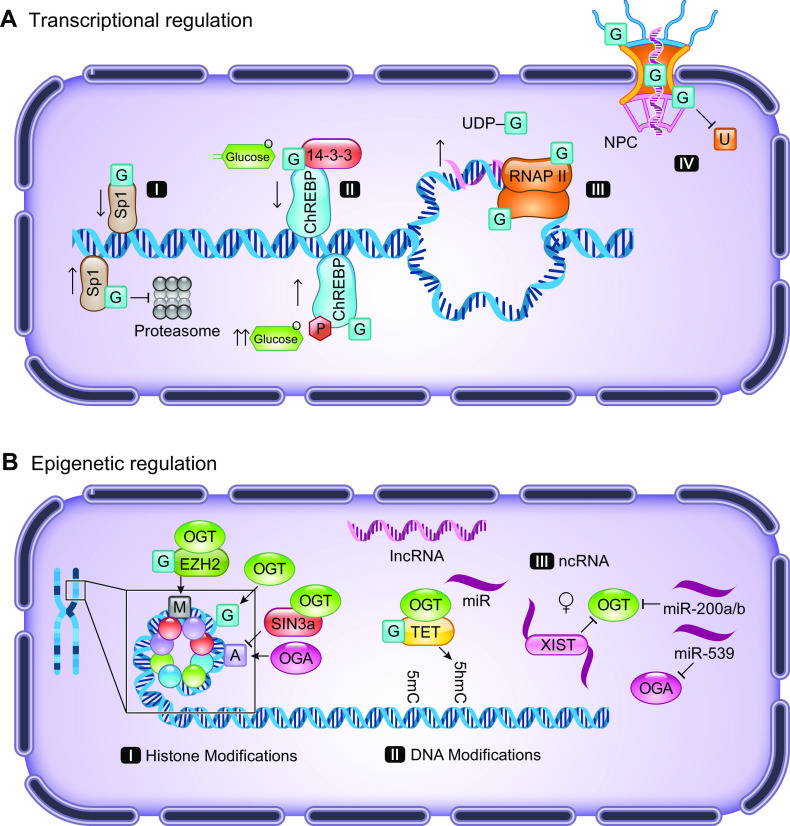

The transcriptional regulation of OGT and OGA has been understudied; however, there are a number of reports indicating that they regulate each other and that O-GlcNAcylation itself might contribute to their transcriptional regulation (257), further discussed in Sect. IIIA and IIIB. For example, in OGT knockout MEFs the time course of loss of OGT was paralleled by a decrease in OGA (280). Increasing O-GlcNAc levels via OGA inhibition demonstrated that OGA transcription was O-GlcNAc dependent (300). Other studies have reported that low O-GlcNAc levels contribute to increased OGT transcription (68). The strongest evidence to date of mutual regulation of OGT and OGA was by Qian et al. (301), who reported that overexpression of OGA resulted in increased OGT transcription, whereas knockdown OGA with siRNA significantly decreased OGT levels. Using promoter luciferase reporters for both OGT and OGA, they clearly demonstrated reciprocal transcriptional regulation (301). They also showed that OGA cooperated with p300m, a histone acetyltransferase and the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β (C/EBP-β) to promote OGT transcription (301). E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1), which contributes to the activation of many genes, was found to be a repressor of both OGT and OGA (302). It has been shown that E2F1 activity itself might be regulated by O-GlcNAcylation, illustrating another mechanism by which O-GlcNAc can regulate the transcription of OGT and OGA (303). The OGT promoter contains a TATA box, which likely facilitates OGT transcription, whereas the OGA transcription is not dependent on a TATA box (302). In macrophages, Cullin 3 (CUL3), an E3 ubiquitin ligase, has been reported to downregulate OGT expression in a nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2)-dependent manner (304).

Another potential mechanism for maintaining O-GlcNAc homeostasis is alternative splicing of both OGT and OGA, resulting in intron retention, which is regulated by changes in O-GlcNAc levels (68, 305). Consequently, when O-GlcNAc levels are high, nuclear retention of OGT due to intron retention increases, whereas low-O-GlcNAc levels decrease this process; thereby, decreasing or increasing OGT protein, respectively (68, 305). Conversely, low O-GlcNAc levels increase nuclear retention of OGA (305). It is noteworthy that these changes occur relatively rapidly and, as such, represent a potentially important mechanism in O-GlcNAc-mediated regulation of O-GlcNAc homeostasis (305). A number of microRNAs (miRs), including miR-101, 200a/b, 423-5p, 501-3p, 539, and 619-3p, have also been shown to regulate O-GlcNAc levels by targeting OGT (306–309) or OGA (310). Consequently, although our knowledge of the transcriptional regulation of OGT and OGA is improving, the physiological role of these pathways remains to be determined.

One of the more puzzling aspects of O-GlcNAc homeostasis is that glucose deprivation leads to a marked increase in overall cellular O-GlcNAc levels. This was first reported in HepG2 cells where it was observed that 12 h following the removal of glucose, there was approximately eight-fold increase in O-GlcNAc levels, which was accompanied by a ∼40% decrease in UDP-GlcNAc levels, suggesting that increased HBP flux was not contributing to the elevated O-GlcNAcylation (311). A later study came to a similar conclusion, as the addition of 50–100 µM glucosamine blocked the O-GlcNAc increase, resulting from glucose deprivation (312). Contrary to this finding was a report that glycogen degradation triggered by glucose deprivation provided the substrate for O-GlcNAcylation (313). Moreover, ATF4, a regulator of the unfolded protein response (UPR), increased GFAT1 expression in response to glucose deprivation, and ATF4 inhibition or knockdown prevented the increase in O-GlcNAc and GFAT1 (221). They also suggested that ATF4, along with another UPR-related protein X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), mediated the steady-state levels of GFAT1 (221). This is consistent with an earlier report demonstrating that stress-induced increases in O-GlcNAc were mediated via XBP1 increases in GFAT1 protein levels (314). Glucose deprivation increased mRNA levels of both OGT and OGA; however, this was not associated with an increase in the levels of either protein (312). Interestingly, extracellular Ca2+ was required for this increase in O-GlcNAc levels, and inhibition of CaMKII blunted the response to glucose deprivation (312).

Historically, nutrient availability was considered to be the primary regulator of cellular O-GlcNAc homeostasis; however, it is increasingly evident that it is only one of many factors. Our knowledge of transcriptional regulation is growing, but it remains limited, and the role of phosphorylation in regulating GFAT and OGT activity is improving; however, the role of phosphorylation in regulating OGA activity is underexplored. Several lines of evidence suggest that Ca2+-mediated activation of CaMKII contributes to O-GlcNAc homeostasis, which would be consistent with rapid agonist-induced increases in O-GlcNAc being independent of nutrient availability or transcriptional regulation of GFAT1, OGT, and OGA.

2.5. Cross Talk Between O-GlcNAcylation and Phosphorylation

As the dynamic nature of O-GlcNAcylation was recognized, there was speculation that it might play a regulatory role in protein function. Once it was recognized that O-GlcNAc modified Ser and Thr residues, which are also potential sites of phosphorylation, there was increasing consideration about possible interactions between O-GlcNAc and phosphorylation on proteins (211, 293). One concept that gained early popularity was the possibility of reciprocity between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation. In other words, that a specific residue on a protein could be modified by either O-GlcNAc or phosphorylation became more widely known as the “Ying-Yang” hypothesis (315). There are, indeed, several proteins that support this concept, such as cMyc (Thr-58) (98), estrogen receptor (ER)-β (Ser-16), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (Ser-1177) (190). Alternatively, modification of adjacent sites can negatively interact with each other, for example, histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) is O-GlcNAcylated at Ser-642, and this blocks CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of Ser-632 (316). Consequently, it is becoming increasingly clear that the cross talk between O-GlcNAc and phosphorylation is much more complex than first thought (FIGURE 7). A high-throughput proteomic analysis estimated that in only 8% of O-GlcNAcylated proteins was the same residue modified by phosphorylation (182). Some proteins are modified by both O-GlcNAc and phosphate, but not at the same sites; for example, increases in phosphorylation of Thr-200 of CaMKIV decreases overall O-GlcNAcylation at several sites, including Ser-189, and conversely, prevention of Thr-200 phosphorylation increased CaMKIV O-GlcNAcylation (167). In myosin light chain 1, the O-GlcNAc-modified sites are Thr-93 and Thr-164, whereas the phosphorylation sites are at Thr-69 and Ser-200 (147).

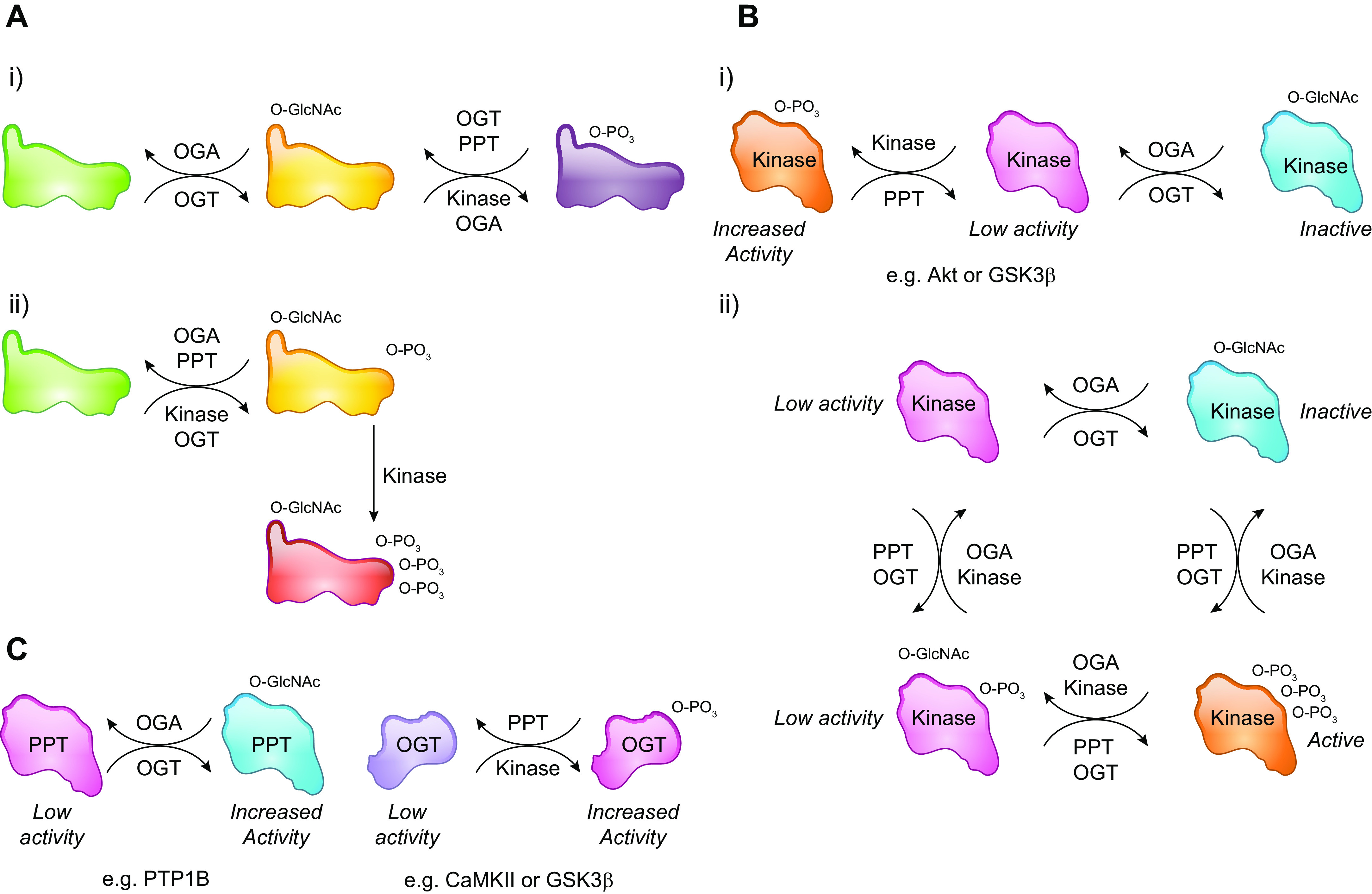

FIGURE 7.

Extensive crosstalk between phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation. A, i: example of phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation of the same or adjacent sites that prevent simultaneous modifications. and A, ii: modification by both phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation, as well as O-GlcNAcylation enhancing phosphorylation via for example increased binding to adaptor proteins. B, i: example of a kinase that is activated when phosphorylated and inactivated by O-GlcNAcylation. B, ii: a kinase that can be modified by both O-GlcNAc and phosphorylation involving complex interactions between OGT/OGA and kinases/phosphatases. C: O-GlcNAcylation also regulates phosphorylation via modification of phosphatases, and OGT activity is directly regulated by kinase phosphorylation. GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; OGA, O-GlcNAcase; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase; PPT, protein phosphatase.

The intricate relationship between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation was demonstrated by a study in which GSK3β was inhibited and O-GlcNAcylation levels of specific proteins were quantified. Of the 45 O-GlcNAcylated proteins identified, 10 exhibited an increase in O-GlcNAcylation, whereas 19 showed a decrease (317). In another study in which O-GlcNAc levels were increased by inhibition of OGA, increased phosphorylation was observed on 148 sites and lower phosphorylation was observed at 280 sites (318). A comparison between wild-type and OGT-null cells identified 232 phosphosites that were upregulated and 133 phosphosites that were downregulated 36 h after OGT deletion (319). Interestingly O-GlcNAc modifications have been reported to occur in clusters (182), a phenomenon that is also observed with phosphorylation (320). Therefore, it is evident that the cross talk between these two posttranslational modifications is complex, and it is currently not possible to predict a priori how they will interact on individual proteins. However, specific motifs have been identified, which when phosphorylated, strongly inhibit O-GlcNAcylation and vice versa; whereas, sites that are phosphorylated by proline-directed kinases do not appear to be subject to O-GlcNAcylation (321).

Recent studies have demonstrated that OGT and OGA form complexes with both kinases and phosphatases (322–324) demonstrating that changes in O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation could be occurring simultaneously on a target protein (FIGURE 7A). There is also a growing list of kinases that have been shown to be O-GlcNAcylated and that this modification directly affects their function (see TABLE 2 and FIGURE 7B). An analysis of glycoproteomic data sets reported that more than 100 kinases contain identified O-GlcNAcylation sites, emphasizing the importance of O-GlcNAc in regulating kinase function (325). A study of synaptic proteins found that kinases were more frequently a target for O-GlcNAcylation than other proteins; however, the specific modification sites were frequently outside the catalytic domain of the kinases in question (182). Thus, protein O-GlcNAcylation can alter phosphorylation either via direct modification of phosphorylated proteins, but also by regulation of kinases that are responsible for phosphorylation. Although there is less known about O-GlcNAcylation of phosphatases, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) has been shown to be O-GlcNAcylated at Ser-104, Ser-201, and Ser-386, resulting in increased enzymatic activity (176).