Abstract

Acetylcholine plays a pivotal neuromodulatory role in the brain, influencing neuronal activity and cognitive function. Nicotinic receptors, particularly α7 and α4β2 receptors, modulate firing of dorsolateral prefrontal (dlPFC) excitatory networks that underlie successful working memory function. Minimal work however has been done examining working memory following systemic blockade of nicotinic receptor systems in nonhuman primates, limiting the ability to explore interactions of other neuromodulatory influences with working memory impairment caused by nicotinic antagonism. In this study, we investigated working memory performance after administering three nicotinic antagonists, mecamylamine, methyllycaconitine, and dihydro-β-erythroidine, in rhesus macaques tested in a spatial delayed response task. Surprisingly, we found that no nicotinic antagonist significantly impaired delayed response performance compared to vehicle. In contrast, the muscarinic antagonist scopolamine reliably impaired delayed response performance in all monkeys tested. These findings suggest there are some limitations on using systemic nicotinic antagonists to probe the involvement of nicotinic receptors in aspects of dlPFC-dependent working memory function, necessitating alternative strategies to understand the role of this system in cognitive deficits seen in aging and neurodegenerative disease.

Keywords: nicotinic, prefrontal, working memory, monkey

1. Introduction

As one of the key modulatory neurotransmitters in the brain, acetylcholine shapes synaptic architecture, coordinates global brain-wide dynamics, and modulates network plasticity (for review see Picciotto et al., 2012). The two major subtypes of acetylcholine receptors – the metabotropic muscarinic receptors (mAChRs) and the ionotropic nicotinic receptors (nAChRs) – are expressed by neuronal and nonneuronal cells throughout the brain (Akaike & Izumi, 2018; Albuquerque et al., 2009). Muscarinic receptors consist of five types (M1–M5) and can be further subdivided based on their coupling to Gαq (M2 and M4) or Gαi (M1, M3, and M5). Nicotinic receptors are grouped into two classes with nine α-subunits (α2-α10) and three β-subunits (β2-β4) and can be found as homopentameric or heteropentameric oligomers throughout the nervous system (Akaike & Izumi, 2018; Zoli et al., 2015). Different combinations of these subunits provide a rich diversity of nAChRs in the brain with distinct pharmacological and physiological properties.

nAChRs are highly expressed in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex so it is not surprising that cholinergic signaling through nAChRs is central to memory, attention, and many higher-order cognitive functions (Galvin, Arnsten, et al., 2020; Koukouli & Changeux, 2020). Nicotine alone improves performance in tasks assessing attention and working memory in rodents, nonhuman primates, and humans (Buccafusco et al., 1999; Elrod et al., 1988; B. Hahn et al., 2002; Katner et al., 2004; Levin & Simon, 1998). Two widely studied nAChRs, the homopentameric α7 receptor and the heteropentameric α4β2 receptor, are implicated in prefrontal-mediated cognitive function. Iontophoretic stimulation of either receptor system in monkeys enhances task-related firing of dorsolateral prefrontal (dlPFC) neurons in working memory tasks and blockage of either receptor reduces memory-related firing in dlPFC neurons (Sun et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2013). Systemic administration of α4β2 and α7 agonists improves working memory performance in both delayed response and delayed matching-to-sample tasks in monkeys (Buccafusco & Terry, 2009; Castner et al., 2011).

Although application of nicotinic agonists has frequently been shown to enhance cognitive function, effects of nicotinic antagonism have been a mixed bag. Systemic administration of mecamylamine (MEC), a noncompetitive nAChR antagonist, blocks nicotine-induced memory improvements in rhesus monkeys (Elrod et al., 1988; Levin & Simon, 1998) and, at high doses, impairs spontaneous alternation performance in rats (Newman & Gold, 2016). High doses (1.78 mg/kg) of MEC also impair visuospatial associative learning in rhesus monkeys (Katner et al., 2004). On the other hand, humans tested in a n-back working memory task show no impairment following MEC (Green et al., 2005) and rhesus monkeys are unimpaired in delayed match-to-sample and self-ordered spatial search tasks following MEC injection (Katner et al., 2004). In some studies, monkeys have even shown improvements in delayed match-to-sample or continuous performance tasks after MEC (Liu et al., 2018; Terry et al., 1999). Based on evidence that nicotinic receptor antagonists disrupt working memory-related activity in dlPFC neurons, we tested three nicotinic antagonists - MEC, methyllycaconitine (MLA), and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHbE) - on a spatial delayed response task in rhesus monkeys. MEC is a nonselective nAChR antagonist, whereas MLA is selective for α7 receptors and DHbE is primarily selective for α4β2 receptors (Bacher et al., 2009; Callahan et al., 2013; Chavez-Noriega et al., 1997; Levin & Simon, 1998). Using these three antagonists, we sought to characterize the general contributions of the nAChR system as well as specific contributions of α4β2 and α7 receptors, highly expressed in prefrontal cortex (Galvin et al., 2020; Quik et al., 2000), on working memory function in nonhuman primates. We planned to use this model of working memory impairment to later test whether neuromodulatory strategies could overcome and reverse the effects of nicotinic antagonism.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Subjects

Six rhesus macaques, 2 female (denoted cases B and D) and 4 male (denoted cases A, J, Ro, and Ru), were used in this study. Monkeys were between 5 and 11 years old and weighing 4.2 to 7.9 kg at the time of injections. Monkeys were socially housed indoors in single sex groups. Daily meals, consisting of a ration of monkey chow and a variety of fruits and vegetables, was given within transport cages once testing was completed, except on weekends when they were fed in their home cages. Water was available ad libitum in the home cages. Environmental enrichment, in the form of play objects or small food items, was provided daily in the home cages. All procedures were approved by the Icahn School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conform to NIH guidelines on the use of non-human primates in research.

2.2. Apparatus

Testing was performed within a Wisconsin General Testing Apparatus (WGTA). The WGTA is a small enclosed testing area where the experimenter can manually interact with the monkey during testing. Monkeys were trained to move from the home cage enclosure to a metal transport cage, which was wheeled into the WGTA. The experimenter was hidden from the monkey’s view by a one-way mirror, with only the experimenter’s hands visible. A sliding tray with two food wells could be advanced within reach of the monkey, with a pulley-operated opaque black screen that could be lowered to separate the tray from the monkey.

2.3. Behavioral testing

Training on the delayed response task followed (Bachevalier & Mishkin, 1986; Croxson et al., 2011). Monkeys were first shown a small food reward that was placed in one of two food wells on a sliding tray. The left/right location of the reward was chosen across trials based on a pseudorandomly, counterbalanced sequence. Both wells were then covered with flat, gray tiles and a black opaque screen was lowered between the tray and the monkey for a predefined delay period. The screen was subsequently raised, and the test tray was advanced to the monkey, allowing the monkey to displace one of the well covers (Fig. 1). During initial shaping, monkeys were taught to displace the tiles covering the wells and select the reward. Once monkeys readily displaced the tiles, they progressed through three stages of training with 24 trials per session. Once a monkey reached criterion on the third stage of training, experimental training began. In the experimental task depending on training, monkeys completed sessions with either four possible delay intervals (5, 10, 15, or 20 s) and 24 trials per session or five possible delay intervals (5, 10, 15, 20, or 30 s) and 30 trials per session, based on whether monkeys tolerated 30 s delays during testing and whether performance was at ceiling levels in the 24-trial format. The two different session formats were not balanced across drug conditions as some monkeys had already progressed to 30 trials by time of injections. For every antagonist and dose, excluding 0.32 mg/kg and 1.0 mg/kg MEC, at least one monkey tested completed the 24-trial format. The delay and left/right well location pairings were varied pseudorandomly across trials such that each delay occurred six times in each testing session.

Fig 1.

Spatial delayed response task schematic. The monkey views a reward placed in one of two wells. The wells are then covered by opaque plaques and a screen is placed between the monkey for a variable delay. The screen is subsequently raised, and the monkey moves a plaque to make a selection.

Drug injections began once a monkey had achieved stable performance on the task. Monkeys continued with this variable delay design of the delayed response task for approximately seven months during the remainder of the experiment, through vehicle injections and injection of all drug conditions. The number of testing sessions per subject for each drug and dose condition can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of testing sessions for each nicotinic antagonist in each monkey

| Drug (dose, mg/kg) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | MEC (0.32) | MEC (1.0) | MEC (1.8) | MLA (1.0) | DHbE (0.32) | DHbE (0.5) |

| A | --- | --- | --- | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B | 2 | 2 | 1 | --- | --- | --- |

| D | 2 | 3 | 2 | --- | --- | --- |

| J | --- | --- | 3 | 3 | --- | 1 |

| Ro | --- | --- | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Ru | --- | --- | --- | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2.4. Drug Preparation

Drugs were prepared fresh daily, at concentrations so that monkeys received 0.1 ml/kg for injection (e.g., for a 1.0 mg/kg dose of drug, drug solution was prepared at a concentration of 10.0 mg/ml). All drugs were dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline solution. Solutions were filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter and pH was determined before injection.

Mecamylamine (Tocris, Minneapolis, MC) was stored in a desiccator at room temperature and given at 0.32, 1.0, and 1.8 mg/kg, intramuscularly. Methyllycaconitine (Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) was stored at 4°C and given at 1.0 mg/kg, intramuscularly. Dihydro-β-erythroidine (Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) was stored at room temperature and given at 0.32 and 0.5 mg/kg, intramuscularly. Vehicle injections were given at 0.1 ml/kg and consisted of sterile 0.9% saline solution. Cholinergic antagonists were never administered more than twice per week and never on adjacent test days to allow for a washout period. There were vehicle or no-injection test days on other days of the test week. MEC has been administered between 10 and 30 minutes prior to testing (Cunningham et al., 2014; Katner et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2018; Terry et al., 1999). Although published data are scarce on systemic injections of DHbE and MLA, the two have been administered between 20 and 30 minutes prior to testing in monkeys and rodents (Callahan et al., 2013; Cunningham et al., 2012; Moerke et al., 2017; Palandri et al., 2021). We also used the literature on MEC to guide the timing of doses for MLA and DHbE. For our study, MEC was given in the home cage 20 minutes before testing began, MLA was given between 10 and 15 minutes prior to testing, and DHbE was given 15 minutes prior to testing. All three antagonists show good brain penetrance and cross the blood-brain barrier (Andriambeloson et al., 2014; Bacher et al., 2009; Withey et al., 2018). Cases B and D were solely tested with MEC, Cases J and Ro were tested with MEC first, followed by MLA, and then DHbE, and Cases A and Ru were first tested with MLA followed by DHbE. Throughout the study, we did not observe any order effects or obvious effects on behavior on the days following drug injections.

Doses for the three antagonists were selected based on previous literature. For MEC, the range of 0.32–1.8 mg/kg has been reported to have discriminative stimulus effects (Cunningham et al., 2012, 2014) and doses within that range have been used in previous cognitive studies (Katner et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2018). We did not proceed to higher doses as we reached a dose range where off-target effects were apparent in behavior. For MLA, we used a dose of 1.0 mg/kg as that fell mid-range to previous doses used in rodents (0.03–10 mg/kg in Andriambeloson et al., 2014) and is greater than the highest dose used in a previous study in squirrel monkeys (0.1 mg/kg in Withey et al., 2018). DHbE has been shown to have discriminative effects at 0.067–0.51 mg/kg (Moerke et al., 2017) and so we elected to use 0.32 mg/kg and 0.5 mg/kg for our study. Although higher doses of DHbE have been used before (up to 5.6 mg/kg in Cunningham et al., 2012), these doses may lead to off-target effects or potential death in subjects.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed in RStudio with R 3.5 (R Core Team, 2018) using the lme4, lmerTest, and emmeans packages (Kuznetsova et al., 2017; Lenth, 2019). Data were analyzed with a generalized linear mixed model and binomial distribution, with trial outcome (correct or incorrect) as the outcome variable, Injection (VEH, MEC 0.32 mg/kg, MEC 1.0 mg/kg, MEC 1.8 mg/kg, MLA 1.0 mg/kg, DHbE 0.32 mg/kg, and DHbE 0.5 mg/kg) and Delay (5–30 seconds) as fixed effects, and Case as a random effect to account for repeated sessions across time for each monkey. We calculated estimated marginal means from the fitted model for each drug condition across all tested cases. We analyzed pairwise comparisons and contrasts to determine differences in performance between VEH and each antagonist drug dose as well as differences between the tested doses of each antagonist drug themselves (when appropriate). Due to inter-case variability across monkeys in response to antagonist drugs, a generalized linear model and estimated marginal means for each drug condition were also computed for each Case regardless of the outcome of the overall model. Reported confidence intervals are given on a log odds ratio scale. P-values and confidence intervals were adjusted using the Tukey method for multiple comparisons. Full models, those for each drug condition across all four cases and those for individual cases, were tested for over/underdispersion of residuals using simulation-based tests to measure deviation of residuals and dispersion of residual standard deviations (Hartig, 2019). All evaluations of model residuals returned no significant over/underdispersion (two-sided nonparametric test, p > 0.05).

We calculated difference scores for each monkey for each antagonist and dose condition to identify changes in mean delayed response accuracy between VEH and antagonist drug. For MEC, DHbE, and scopolamine (SCOP), we computed a linear mixed-effect model with difference score as the outcome variable, Injection as a fixed effect, and Case as a random effect. Because only one dose of MLA was tested (and therefore only one level of Injection variable), we performed a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. We recorded the total time to complete each behavioral session to use as a proxy for motivation and test whether administration of the antagonists led to drug-induced sedation during the delayed response task. Data were analyzed in a linear mixed model for each antagonist drug condition (MEC, MLA, and DHbE) and each session type (24 total trials or 30 total trials) across all cases with total session time as the outcome variable, Injection as a fixed effect, and Case as a random effect. After each model was generated, we calculated the estimated marginal means and analyzed the pairwise contrasts to determine any differences in total session time between VEH and each antagonist at their tested doses.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline performance in the delayed response task

Monkeys successfully learned the delayed response task with four subjects (Cases A, J, Ro, and Ru) performing a 30-trial form of the task with delays from 5–30 seconds and two subjects (Cases B and D) performing a 24-trial form of the task with delays from 5–20 seconds. For VEH sessions, mean accuracies were: 5 seconds: 88.6; 10 seconds: 86.0; 15 seconds: 83.3; 20 seconds: 81.5; 30 seconds: 82.3 (Fig. 2, blue lines). Although monkeys showed clear inter-individual variability in working memory performance, there was a reliable delay-dependent decrease in percent correct (X2(4) = 67.95, p < .0001).

Fig 2.

Spatial delayed response performance by delay for vehicle and each drug condition. (A) Performance following mecamylamine injection for each case across all tested delay intervals. (B) Performance after methyllycaconitine injection across delays. (C) Performance after dihydro-β-erythroidine injection across delays. Data are represented as mean performance ± sem. VEH: vehicle, MEC: mecamylamine, MLA: methyllycaconitine, DHbE: dihydro-β-erythroidine.

3.2. Effects of mecamylamine on working memory function

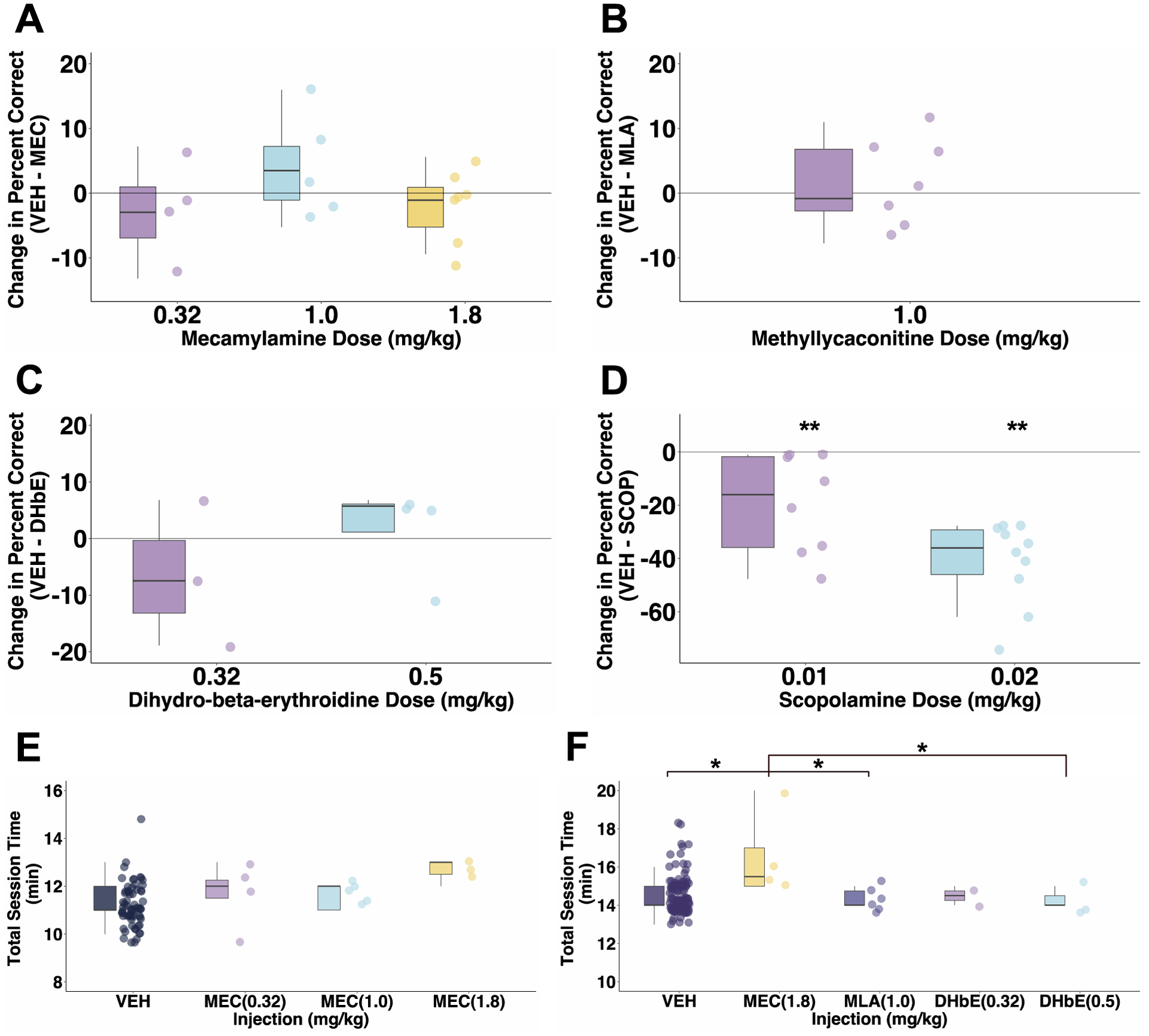

Analysis of the estimated marginal means comparisons from our full model across all four cases (B, D, J, Ro) indicated that monkeys showed no consistent difference in working memory performance following any dose of MEC compared with VEH (Fig 2A; MEC 0.32 mg/kg: p = 0.99, 95% confidence interval of (−0.561, 0.899); MEC 1.0 mg/kg: p = 0.94, (−0.971, 0.461); MEC 1.8 mg/kg: p = 0.99, (−0.531, 0.795)). Pairwise contrasts for each monkey also revealed no effect of MEC on delayed response performance compared to performance after vehicle (p > 0.05 for each monkey and each VEH-MEC comparison). We also calculated a difference score between VEH and MEC percent correct values for each monkey to identify changes in mean accuracy across monkeys between each dose of MEC and VEH (Fig 3A). We found no significant difference in performance after MEC injection (F(2,13) = 1.38, p = 0.28).

Fig 3.

Change in baseline delayed response performance following each drug dose across cases. (A) Change from mean performance under vehicle after administration of mecamylamine across the group of four monkeys. (B) Change from vehicle performance following methyllycaconitine across monkeys. (C) Change from vehicle performance following dihydro-β-erythroidine across monkeys. (D) For comparison, change from vehicle performance following scopolamine in the same group of monkeys as shown in B and C (Wilcoxon signed-rank test; 0.01 mg/kg SCOP: p = .0078, 0.02 mg/kg SCOP: p = .0019). (E) Total task time for sessions with 5–20s delays. (F) Total task times for sessions with 5–30s delays. VEH: vehicle, MEC: mecamylamine, MLA: methyllycaconitine, DHbE: dihydro-β-erythroidine. * p < .05, ** p < .01; p value adjustment: Tukey method.

3.3. Effects of methyllycaconitine on working memory function

Monkeys (A, J, Ro, Ru) showed no significant difference in delayed response performance after MLA compared to that after VEH (Fig 2B; p = 0.99, (−0.941, 0.618)). As with mecamylamine, comparison of contrasts for each monkey showed that MLA did not significantly affect working memory performance in any monkey (p > 0.05). After computing the difference score between VEH and the 1.0 mg/kg dose of MLA, we found no significant change from baseline performance across monkeys (Fig 3B; mu = 0, V = 17, p = 0.68).

3.4. Effects of dihydro-β-erythroidine on working memory function

We found that across cases (A, J, Ro, Ru) there was no significant effect of DHbE on working memory performance (Fig 2C; DHbE 0.32 mg/kg: p = 0.43, (−0.268, 1.352); DHbE 0.5 mg/kg: p = 0.99, (−1.017, 0.787)). Analysis of contrasts for individual monkeys showed that DHbE had no significant effect on delayed response performance (p > 0.05). For Case A, the effect of 0.32 mg/kg DHbE approached significance (p = 0.07) which appears driven by the markedly reduced percent correct at 5 seconds after that dose. Difference scores for both doses of DHbE revealed no significant difference from baseline performance (Fig 3C; F(1, 2.25) = 3.47, p = 0.18). It is interesting that three out of four monkeys actually showed numerical working memory improvements following the higher 0.5 mg/kg DHbE dose, although these did not reach statistical significance.

3.5. Effects of scopolamine on working memory function

We also tested four monkeys in the spatial delayed response task after scopolamine injection to investigate effects of muscarinic antagonism on working memory function. Contrary to our findings following nAChR antagonists, all four monkeys were significantly impaired in the delayed response task after scopolamine injection compared to performance after vehicle (SCOP 0.01 mg/kg: p < .0001, (0.785, 1.52); SCOP 0.02 mg/kg: p < .0001, (1.819, 2.45)). Scopolamine administration also led to a significant change from baseline vehicle performance (Fig 3D; p = 0.017). For all four monkeys, scopolamine was tested after the three nAChR antagonists. We saw scopolamine-induced working memory impairment consistently for each case for each tested session which was particularly striking considering the clear lack of effect at all tested doses of nicotinic antagonists.

3.6. Effects of cholinergic antagonists on total session time

For all behavioral sessions, we recorded the total time to complete the delayed response task and used this as both a proxy for motivation as well as a measure of drug-induced sedation. For those sessions with 24 total trials (i.e. delay intervals ranging from 5–20 seconds), we found no significant difference in total session time between vehicle and any of the drugs or tested doses (Fig 3E; p > 0.05, across all four cases for mecamylamine). For those sessions with 30 trials (delay intervals ranging from 5–30 seconds), monkeys took significantly longer to complete the task following 1.8 mg/kg MEC compared to the total session time after VEH, 1.0 mg/kg MLA, and 0.5 mg/kg DHbE (Fig 3F; p < 0.05 across the four tested cases for each drug). Antagonist drugs did not affect monkeys’ ability to complete the total trials per session on testing days. Although not quantitatively measured, we also found that two of the monkeys (Cases B and D) displayed lack of motivation following 1.8 mg/kg MEC, seen as disinterest in reward and refusal to eat rewards. Despite this impaired motivation in two cases and sedation following 1.8 mg/kg MEC, we did not observe any signs of ganglionic blockade or any other drug-induced effects following the nAChR antagonists.

4. Discussion

Neurophysiological evidence has clearly established that nAChRs play a role in proper working memory function, but there have been conflicting results on the effects of acute or systemic nAChR blockade on cognitive performance. Iontophoretic application of MEC, DHbE, and MLA to delay cells in dlPFC (Sun et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2013) significantly reduces neuronal firing during a working memory task. For MEC, this reduction was apparent in all task epochs, whereas for MLA and DHbE firing reductions were confined to the delay period. However, we found no consistent impairments in the delayed response task following administration of any of the three tested nicotinic antagonists, a surprising finding considering their neurophysiological effects in the context of dlPFC-dependent working memory. For MEC, a largely nonspecific nAChR antagonist, no monkey showed deficits in the delayed response task over the three tested doses (0.32, 1.0, and 1.8 mg/kg). For MLA, a α7 antagonist, monkeys showed no working memory impairment at a 1.0 mg/kg dose. And for DHbE, a α4β2 antagonist, no monkey was impaired in delayed response performance after 0.32 and 0.5 mg/kg injections. Higher doses of DHbE were not tested due to potential for adverse side effects (Cunningham et al., 2012; Withey et al., 2018). Additionally, side effects after the highest dose of MEC (decreased motivation, longer session times) limited our ability to test higher doses. In contrast, scopolamine, a muscarinic antagonist, reliably impaired performance in all monkeys tested.

An important limitation of our study is the relatively low number of test sessions with each dose of each drug. It is a logical possibility that repeated testing, perhaps with a more granular dose range, may have identified individual doses of particular antagonists that reliably affected memory in individual monkeys. We also recognize that only one dose of MLA tested compared to multiple doses of the other antagonists may limit our ability to completely rule out the involvement of α7 nAChRs on delayed response performance. We selected a 1.0 mg/kg dose as it appeared to be in the middle range of doses used in previous work investigating MLA in rodents and nonhuman primates (Andriambeloson et al., 2014; Withey et al., 2018). Despite these limitations, the lack of consistent effects of the nicotinic antagonists compared to scopolamine is striking. This also indicates that the ability to access nicotinic modulation of dlPFC-dependent working memory function via systemic antagonists is very limited compared to the effects of muscarinic antagonists.

Previous research utilizing MEC, MLA, and DHbE to probe the role of nAChRs in cognition has been mixed with either behavioral impairments, improvements, or no effect at all following nAChR blockade. Local intrahippocampal infusion of MEC, MLA, and DHbE in rats impairs working and reference memory, and rats given IP injections of MEC (10 mg/kg) also make more errors in a working memory task compared to those after vehicle (Felix & Levin, 1997; Ohno et al., 1993). In rats, MLA administration leads to greater errors in a spontaneous alternation T-maze task (Andriambeloson et al., 2014) and application of MLA reverses nicotine-induced enhanced performance in the 5-choice serial reaction time task (Hahn et al., 2011). There are pharmacokinetic differences between rodents and primates that prevent direct comparison of doses, but with higher doses of MEC monkeys took longer to complete sessions and were less interested in food rewards, indicating that we had reached a dose range where off-target effects were limiting. It has been reported that higher doses of MEC may also inhibit NMDA receptors (Katner et al., 2004; Young et al., 2001), however in vitro experiments using high micromolar concentrations show only small and transient inhibition (Papke et al., 2001). Another study reported potential NMDA receptor blockade after MEC, however the dose of MEC there was nearly three time higher (5.6 mg/kg in Cunningham et al., 2019) than the highest dose used here. Thus, while effects after MEC may be mediated in some part by NMDA receptor antagonism, considering our range of doses and the lack of behavioral effects following MEC administration, we would argue against potential for NMDA blockade.

Interestingly, MEC has also been shown to have no effect (Katner et al., 2004) or even beneficial effects at low doses (Liu et al., 2018; Terry et al., 1999) on cognition. We did not observe obvious order effects of injections as Cases A and Ru had no previous nAChR antagonist prior to MLA while Cases J and Ro had previously been tested with 1.8 mg/kg MEC. Additionally, despite different session formats with 24 or 30 total trials, we found no significant effect of any nAChR antagonist on working memory performance (Figure 2). Although we were unable to balance session formats across doses here, we plan on balancing across doses in future pharmacological studies.

As all our injections were systemic, we are unable to identify the exact locus of scopolamine effects. Microiontophoresis of scopolamine in dlPFC significantly suppresses neuronal activity during a rule-based working memory task (Major et al., 2015) and selective blockade of M1 receptors in dlPFC reduces firing during a delay period (Galvin, Yang, et al., 2020). Given these neurophysiological results as well as the prominent expression of M1 and M2 receptors in PFC (Vijayraghavan & Everling, 2021), we speculate that the scopolamine-induced impairments seen in our study may be due to receptor blockade in frontal cortex. However, scopolamine may also be acting at muscarinic sites in other areas that play key roles in working memory function such as the mediodorsal thalamus and lateral intraparietal area (Bueno-Junior et al., 2012; Davidson & Marrocco, 2000; Mackey et al., 2016; Parnaudeau et al., 2013). It is also unclear whether the tested cholinergic drugs acted primarily at postsynaptic receptors. Indeed, while much focus on cholinergic pharmacological studies is on postsynaptic receptors, both nAChR and mAChR classes are found as presynaptic autoreceptors modulating acetylcholine release (Sarter & Parikh, 2005).

Studies investigating the connections between cognition and acetylcholine remain pivotal as cognitive impairments seen in normal aging and in those with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and schizophrenia have been attributed to abnormalities in central cholinergic signaling, particularly in the nAChR system (Bartus et al., 1982; Buccafusco & Terry, 2009; Court et al., 2000; Picciotto & Zoli, 2002; Schneider et al., 1999). Deficits specifically in the α4β2 and α7 receptor systems correlate with cognitive decline and amyloid-beta deposition in Alzheimer’s disease (Nakaizumi et al., 2018; Okada et al., 2013; Sabri et al., 2018). Cholinomimetic agents and drugs targeting nAChRs have been popular treatment targets for neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders (Newhouse et al., 1997; Sacco et al., 2004; Terry Jr & Callahan, 2019). Unfortunately, results have so far been disappointing with drugs showing limited cognitive benefits or multiple adverse effects (Friedman, 2004; Hoskin et al., 2019; Tregellas & Wylie, 2019). Because our findings here show how nAChR and mAChR systems may differentially regulate working memory in the delayed response task, they may add to understanding how drugs modulating acetylcholine can be developed in the future to ameliorate those cognitive deficits associated with cholinergic dysfunction.

Highlights.

Cholinergic neuromodulation is key for working memory functions of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in nonhuman primates.

Several nicotinic antagonists, administered systemically, did not produce reliable spatial working memory impairments in rhesus monkeys.

In contrast, low doses of the muscarinic antagonist scopolamine reliably impaired working memory.

Investigation of the behavioral neuropharmacology of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors may require local drug infusions into prefrontal cortex or other approaches than systemic administration of antagonists.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R21NS096936 (MGB) and T32AG049688 (NAU). MGB would like to commemorate his friend and colleague, David Bucci. Given the volume of null effects generated by our collaborative experiments in graduate school, a report of negative effects of cholinergic antagonists in a spatial memory task seems particularly fitting for this special issue of Neurobiology of Learning and Memory.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akaike A, & Izumi Y (2018). Overview. In Akaike A, Shimohama S, & Misu Y (Eds.), Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Signaling in Neuroprotection (pp. 1–15). Springer; Singapore. 10.1007/978-981-10-8488-1_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque EX, Pereira EFR, Alkondon M, & Rogers SW (2009). Mammalian Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: From Structure to Function. Physiological Reviews, 89(1), 73–120. 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriambeloson E, Huyard B, Poiraud E, & Wagner S (2014). Methyllycaconitine-and scopolamine-induced cognitive dysfunction: Differential reversal effect by cognition-enhancing drugs. Pharmacology Research & Perspectives, 2(4), e00048. 10.1002/prp2.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher I, Wu B, Shytle DR, & George TP (2009). Mecamylamine – a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist with potential for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 10(16), 2709–2721. 10.1517/14656560903329102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachevalier J, & Mishkin M (1986). Visual recognition impairment follows ventromedial but not dorsolateral prefrontal lesions in monkeys. Behavioural Brain Research, 20(3), 249–261. 10.1016/0166-4328(86)90225-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartus RT, Dean R 3rd, Beer B, & Lippa AS (1982). The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science, 217(4558), 408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccafusco JJ, Jackson WJ, Jonnala RR, & Terry AVJ (1999). Differential improvement in memory-related task performance with nicotine by aged male and female rhesus monkeys. Behavioural Pharmacology, 10(6), 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccafusco Jerry J., & Terry AV (2009). A reversible model of the cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia in monkeys: Potential therapeutic effects of two nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists. Biochemical Pharmacology, 78(7), 852–862. 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.06.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Junior LS, Lopes-Aguiar C, Ruggiero RN, Romcy-Pereira RN, & Leite JP (2012). Muscarinic and Nicotinic Modulation of Thalamo-Prefrontal Cortex Synaptic Pasticity In Vivo. PLOS ONE, 7(10). 10.1371/journal.pone.0047484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan PM, Hutchings EJ, Kille NJ, Chapman JM, & Terry AV (2013). Positive allosteric modulator of alpha 7 nicotinic-acetylcholine receptors, PNU-120596 augments the effects of donepezil on learning and memory in aged rodents and non-human primates. Neuropharmacology, 67, 201–212. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castner SA, Smagin GN, Piser TM, Wang Y, Smith JS, Christian EP, Mrzljak L, & Williams GV (2011). Immediate and Sustained Improvements in Working Memory After Selective Stimulation of α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Biological Psychiatry, 69(1), 12–18. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Noriega LE, Crona JH, Washburn MS, Urrutia A, Elliott KJ, & Johnson EC (1997). Pharmacological Characterization of Recombinant Human Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors hα2β2, hα2β4, hα3β2, hα3β4, hα4β2, hα4β4 and hα7 Expressed in Xenopus Oocytes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 280(1), 346–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court JA, Piggott MA, Lloyd S, Cookson N, Ballard CG, McKeith IG, Perry RH, & Perry EK (2000). Nicotine binding in human striatum: Elevation in schizophrenia and reductions in dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease and in relation to neuroleptic medication. Neuroscience, 98(1), 79–87. 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00071-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxson PL, Kyriazis DA, & Baxter MG (2011). Cholinergic modulation of a specific memory function of prefrontal cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 14(12), 1510–1512. 10.1038/nn.2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CS, Javors MA, & McMahon LR (2012). Pharmacologic Characterization of a Nicotine-Discriminative Stimulus in Rhesus Monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 341(3), 840–849. 10.1124/jpet.112.193078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CS, Moerke MJ, & McMahon LR (2014). The discriminative stimulus effects of mecamylamine in nicotine-treated and untreated rhesus monkeys: Behavioural Pharmacology, 25(4), 296–305. 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MC, & Marrocco RT (2000). Local Infusion of Scopolamine Into Intraparietal Cortex Slows Covert Orienting in Rhesus Monkeys. Journal of Neurophysiology, 83(3), 1536–1549. 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod K, Buccafusco JJ, & Jackson WJ (1988). Nicotine enhances delayed matching-to-sample performance by primates. Life Sciences, 43(3), 277–287. 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90318-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix R, & Levin ED (1997). Nicotinic antagonist administration into the ventral hippocampus and spatial working memory in rats. Neuroscience, 81(4), 1009–1017. 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00224-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JI (2004). Cholinergic targets for cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia: Focus on cholinesterase inhibitors and muscarinic agonists. Psychopharmacology, 174(1), 45–53. 10.1007/s00213-004-1794-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin VC, Arnsten AFT, & Wang M (2020). Involvement of Nicotinic Receptors in Working Memory Function. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg. 10.1007/7854_2020_142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin VC, Yang ST, Paspalas CD, Yang Y, Jin LE, Datta D, Morozov YM, Lightbourne TC, Lowet AS, Rakic P, Arnsten AFT, & Wang M (2020). Muscarinic M1 Receptors Modulate Working Memory Performance and Activity via KCNQ Potassium Channels in the Primate Prefrontal Cortex. Neuron. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A, Ellis K, Ellis J, Bartholomeusz C, Ilic S, Croft R, Luanphan K, & Nathan P (2005). Muscarinic and nicotinic receptor modulation of object and spatial -back working memory in humans. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 81(3), 575–584. 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn B, Shoaib M, & Stolerman I (2002). Nicotine-induced enhancement of attention in the five-choice serial reaction time task: The influence of task demands. Psychopharmacology, 162(2), 129–137. 10.1007/s00213-002-1005-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn Britta, Shoaib M, & Stolerman IP (2011). Selective nicotinic receptor antagonists: Effects on attention and nicotine-induced attentional enhancement. Psychopharmacology, 217(1), 75. 10.1007/s00213-011-2258-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig F (2019). DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level / Mixed) Regression Models (R package version 0.2.6) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org

- Hoskin JL, Al-Hasan Y, & Sabbagh MN (2019). Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonists for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Dementia: An Update. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21(3), 370–376. 10.1093/ntr/nty116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katner SN, Davis SA, Kirsten AJ, & Taffe MA (2004). Effects of nicotine and mecamylamine on cognition in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology, 175(2), 225–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukouli F, & Changeux J-P (2020). Do Nicotinic Receptors Modulate High-Order Cognitive Processing? Trends in Neurosciences, 0(0). 10.1016/j.tins.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff P, & Christensen R (2017). lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. 10.18637/jss.v082.i13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R (2019). emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (R package version 1.3.4) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

- Levin ED, & Simon BB (1998). Nicotinic acetylcholine involvement in cognitive function in animals. Psychopharmacology, 138(3), 217–230. 10.1007/s002130050667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Crawford J, Callahan PM, Terry AV, Constantinidis C, & Blake DT (2018). Intermittent stimulation in the nucleus basalis of meynert improves sustained attention in rhesus monkeys. Neuropharmacology, 137, 202–210. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey WE, Devinsky O, Doyle WK, Golfinos JG, & Curtis CE (2016). Human parietal cortex lesions impact the precision of spatial working memory. Journal of Neurophysiology, 116(3), 1049–1054. 10.1152/jn.00380.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major AJ, Vijayraghavan S, & Everling S (2015). Muscarinic Attenuation of Mnemonic Rule Representation in Macaque Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex during a Pro- and Anti-Saccade Task. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(49), 16064–16076. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2454-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerke MJ, Zhu AZX, Tyndale RF, Javors MA, & McMahon LR (2017). The discriminative stimulus effects of i.v. nicotine in rhesus monkeys: Pharmacokinetics and apparent pA2 analysis with dihydro-β-erythroidine. Neuropharmacology, 116, 9–17. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaizumi K, Ouchi Y, Terada T, Yoshikawa E, Kakimoto A, Isobe T, Bunai T, Yokokura M, Suzuki K, & Magata Y (2018). In vivo Depiction of α7 Nicotinic Receptor Loss for Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 61(4), 1355–1365. 10.3233/JAD-170591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse PA, Potter A, & Levin ED (1997). Nicotinic System Involvement in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Drugs & Aging, 11(3), 206–228. 10.2165/00002512-199711030-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman LA, & Gold PE (2016). Attenuation in rats of impairments of memory by scopolamine, a muscarinic receptor antagonist, by mecamylamine, a nicotinic receptor antagonist. Psychopharmacology, 233(5), 925–932. 10.1007/s00213-015-4174-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno M, Yamamoto T, & Watanabe S (1993). Blockade of hippocampal nicotinic receptors impairs working memory but not reference memory in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 45(1), 89–93. 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90091-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada H, Ouchi Y, Ogawa M, Futatsubashi M, Saito Y, Yoshikawa E, Terada T, Oboshi Y, Tsukada H, Ueki T, Watanabe M, Yamashita T, & Magata Y (2013). Alterations in α4β2 nicotinic receptors in cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s aetiopathology. Brain, 136(10), 3004–3017. 10.1093/brain/awt195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palandri J, Smith SL, Heal DJ, Wonnacott S, & Bailey CP (2021). Contrasting effects of the α7 nicotinic receptor antagonist methyllycaconitine in different rat models of heroin reinstatement. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 0269881121991570. 10.1177/0269881121991570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Sanberg PR, & Shytle RD (2001). Analysis of Mecamylamine Stereoisomers on Human Nicotinic Receptor Subtypes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 297(2), 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnaudeau S, O’Neill P-K, Bolkan SS, Ward RD, Abbas AI, Roth BL, Balsam PD, Gordon JA, & Kellendonk C (2013). Inhibition of Mediodorsal Thalamus Disrupts Thalamofrontal Connectivity and Cognition. Neuron, 77(6), 1151–1162. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Higley MJ, & Mineur YS (2012). Acetylcholine as a Neuromodulator: Cholinergic Signaling Shapes Nervous System Function and Behavior. Neuron, 76(1), 116–129. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, & Zoli M (2002). Nicotinic receptors in aging and dementia. Journal of Neurobiology, 53(4), 641–655. 10.1002/neu.10102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Polonskaya Y, Gillespie A, Jakowec M, Lloyd GK, & Langston JW (2000). Localization of nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in monkey brain by in situ hybridization. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 425(1), 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Sabri O, Meyer PM, Gräf S, Hesse S, Wilke S, Becker G-A, Rullmann M, Patt M, Luthardt J, Wagenknecht G, Hoepping A, Smits R, Franke A, Sattler B, Tiepolt S, Fischer S, Deuther-Conrad W, Hegerl U, Barthel H, … Brust P (2018). Cognitive correlates of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mild Alzheimer’s dementia. Brain, 141(6), 1840–1854. 10.1093/brain/awy099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco KA, Bannon KL, & George TP (2004). Nicotinic receptor mechanisms and cognition in normal states and neuropsychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 18(4), 457–474. 10.1177/026988110401800403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, & Parikh V (2005). Choline transporters, cholinergic transmission and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6(1), 48–56. 10.1038/nrn1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JS, Tinker JP, Velson MV, Menzaghi F, & Lloyd GK (1999). Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonist SIB-1508Y Improves Cognitive Functioning in Chronic Low-Dose MPTP-Treated Monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 290(2), 731–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Yang Y, Galvin VC, Yang S, Arnsten AF, & Wang M (2017). Nicotinic α4β2 Cholinergic Receptor Influences on Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortical Neuronal Firing during a Working Memory Task. The Journal of Neuroscience, 37(21), 5366–5377. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0364-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry Alvin V Jr, & Callahan PM (2019). Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Ligands, Cognitive Function, and Preclinical Approaches to Drug Discovery. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21(3), 383–394. 10.1093/ntr/nty166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry AV, Buccafusco JJ, & Prendergast MA (1999). Dose-specific improvements in memory-related task performance by rats and aged monkeys administered the nicotinic-cholinergic antagonist mecamylamine. Drug Development Research, 47, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Tregellas JR, & Wylie KP (2019). Alpha7 Nicotinic Receptors as Therapeutic Targets in Schizophrenia. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21(3), 349–356. 10.1093/ntr/nty034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayraghavan S, & Everling S (2021). Neuromodulation of Persistent Activity and Working Memory Circuitry in Primate Prefrontal Cortex by Muscarinic Receptors. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 15. 10.3389/fncir.2021.648624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withey SL, Doyle MR, Bergman J, & Desai RI (2018). Involvement of Nicotinic Receptor Subtypes in the Behavioral Effects of Nicotinic Drugs in Squirrel Monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 366(2), 397–409. 10.1124/jpet.118.248070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Paspalas CD, Jin LE, Picciotto MR, Arnsten AFT, & Wang M (2013). Nicotinic 7 receptors enhance NMDA cognitive circuits in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(29), 12078–12083. 10.1073/pnas.1307849110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JM, Douglas Shytle R, Sanberg PR, & George TP (2001). Mecamylamine: New therapeutic uses and toxicity/risk profile. Clinical Therapeutics, 23(4), 532–565. 10.1016/S0149-2918(01)80059-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Pistillo F, & Gotti C (2015). Diversity of native nicotinic receptor subtypes in mammalian brain. Neuropharmacology, 96, 302–311. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]