Abstract

Experimental and hereditary defects in the ubiquitous scaffolding proteins of the spectrin gene family cause an array of neuropathologies. Most recognized are ataxias caused by missense, deletions, or truncations in the SPTBN2 gene that encodes beta III spectrin. Such mutations disrupt the organization of post-synaptic receptors, their active transport through the secretory pathway, and the organization and dynamics of the actin-based neuronal skeleton. Similar mutations in SPTAN1 that encodes alpha II spectrin cause severe and usually lethal neurodevelopmental defects including one form of early infantile epileptic encephalopathy type 5 (West syndrome). Defects in these and other spectrins are implicated in degenerative and psychiatric conditions. In recent published work, we describe in mice a novel variant of alpha II spectrin that results in a progressive ataxia with widespread neurodegenerative change. The action of this variant is distinct, in that rather than disrupting a constitutive ligand-binding function of spectrin, the mutation alters its response to calcium and calmodulin-regulated signaling pathways including its response to calpain activation. As such, it represents a novel spectrinopathy that targets a key regulatory pathway where calcium and tyrosine kinase signals converge. Here we briefly discuss the various roles of spectrin in neuronal processes and calcium activated regulatory inputs that control its participation in neuronal growth, organization, and remodeling. We hypothesize that damage to the neuronal spectrin scaffold may be a common final pathway in many neurodegenerative disorders. Targeting the pathways that regulate spectrin function may thus offer novel avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Membrane-associated periodic skeleton, Calpain, Proteolysis, SPTB, SPTBN1, SPTBN2, SPTAN1, Alzheimer’s, SCA5, Parkinson’s, Neurodegeneration, Proteostasis, RTK signaling, Calcium signaling, HIPPO/YAP signaling

Introduction

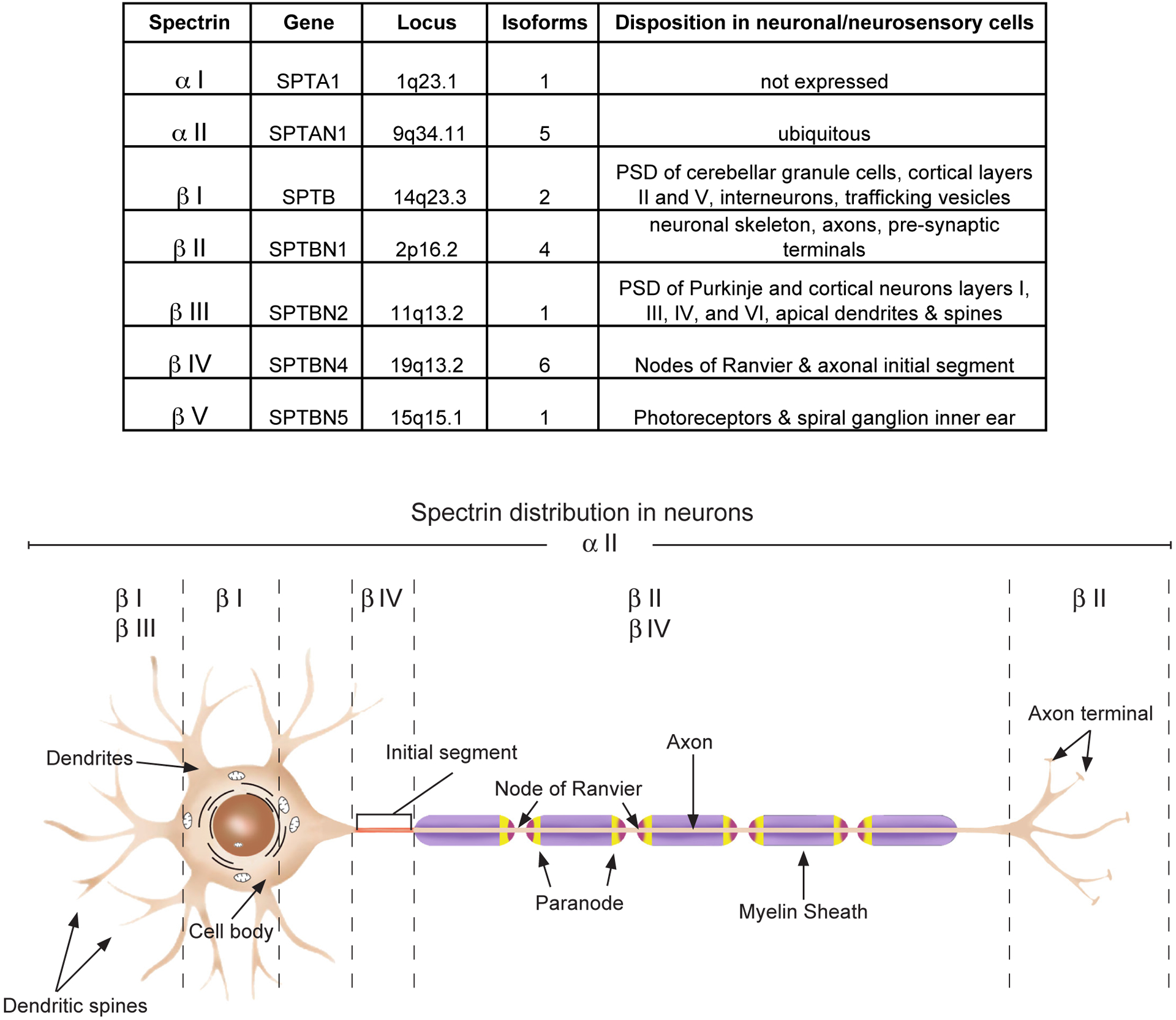

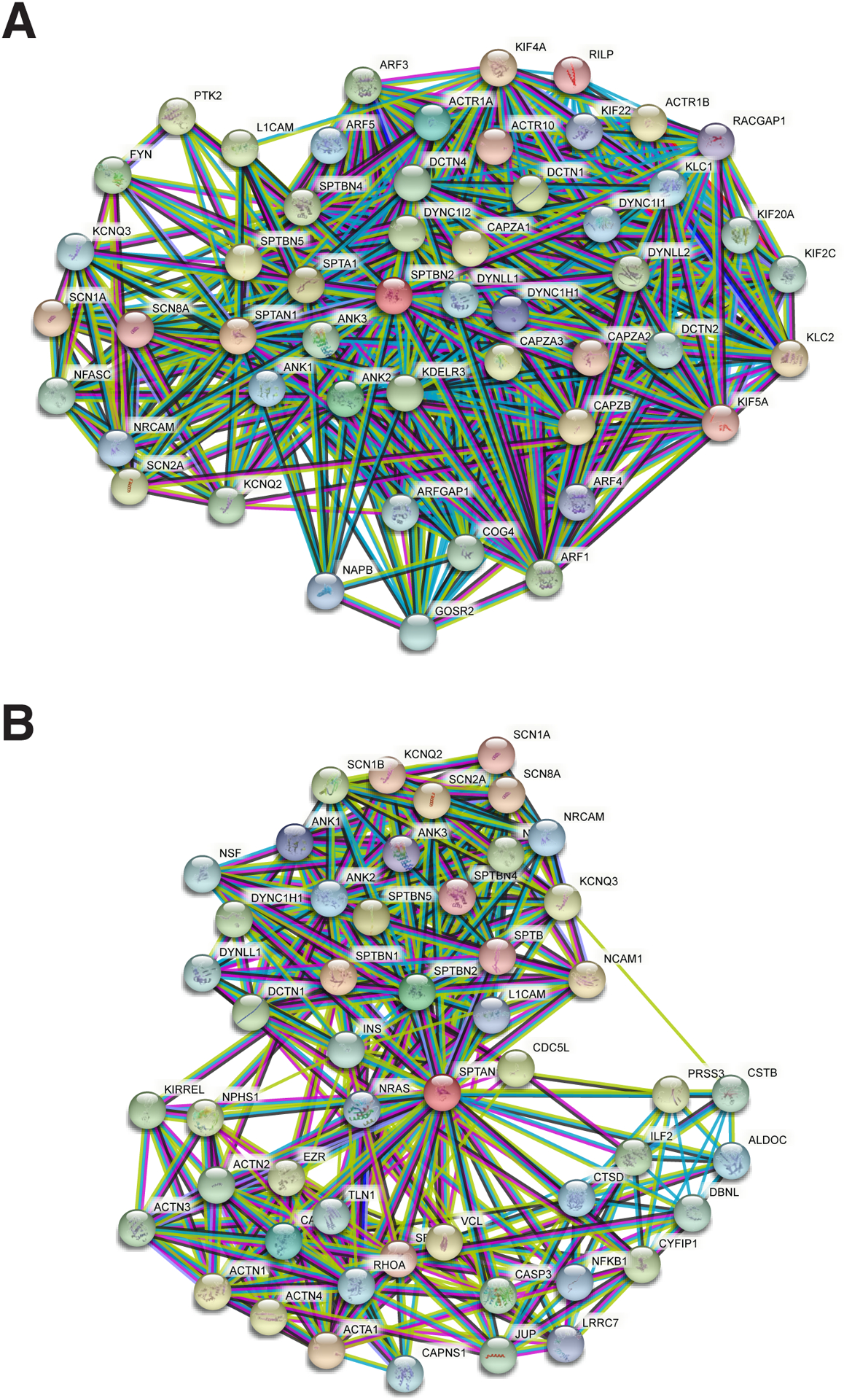

Since its recognition five decades ago as a major component of the erythrocyte’s cortical membrane skeleton, our understanding of spectrin has evolved to include recognition of its ubiquitous presence in probably all animal cells and its role in surprisingly diverse biological functions. This is perhaps most apparent in the nervous system. Seven genes encode the mammalian spectrins (Figure 1). All but one (αI spectrin) are expressed in various neuronal and neurosensory cells. Classically, spectrin is recognized as an actin filament cross-linking protein that also binds directly and through adapter proteins (e.g. ankyrin) to biologic membranes and membrane lipids. In neurons and glia, spectrin forms a caricature of the erythrocyte skeleton, termed the membrane-associated periodic skeleton (MPS) [1]. Beyond its canonical role as an actin binding and membrane-linking protein, the spectrins also serve other roles: i) linkage to motors of intracellular transport, myosin, dynactin and kinesin [2–5]; ii) linkage to the axonal transport of lipid and protein laden vesicles [3,4] iii) stabilization of the Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum [6–9]; iv) trafficking of selected proteins in the secretory and endocytic pathways [8,10–12]; v) upstream regulation of the HIPPO/YAP signaling pathway that guides many aspects of neuronal development and remodeling [13–16]; vi) a multivalent protein-protein interaction scaffold that organizes membrane-associated signaling ensembles [17]; and vii) a target of multiple post-translational modifications that regulate its various functions. The richness of spectrin’s direct and indirect interactions with many biologic pathways can be appreciated in genome wide interaction diagrams of any spectrin; two examples for human βIII spectrin and αII spectrin are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Disposition of the spectrin gene family in neuronal and neurosensory cells and tissues.

Figure 2: Genome-wide Interaction map of spectrin in humans.

(A) Interaction map of βIII spectrin. (B) Interaction map of αII spectrin. The fifty interacting genes with the highest confidence score (>0.9) are represented in each diagram. The edges represent known protein-protein interactions (not necessarily directly bound). Nodes are the respective proteins centered on each spectrin. Edge colors are: purple, experimentally determined; light blue, curated databases; green, gene neighborhood associations. Note the significant interactions of spectrin with cytoskeletal elements, motors of intracellular transport; many ion channels and transporters; components of the Golgi apparatus and the secretory and endocytic pathways; and various receptor tyrosine kinases and adapter proteins. Generated by Strings V11 [78].

Spectrinopathies

Reflecting their diverse roles, spectrin deficiencies or defects lead to diverse neuropathology. Most studied have been the beta spectrins. Disorders in βI spectrin (SPTB) have been linked genetically to autism, learning difficulties, and spinal cord disease [18–20]. Genetic deletion of βII spectrin is embryonic lethal with loss of neural stem cells in the subventricular zone [21,22]; heterozygotes appear neurologically normal, but are prone to develop liver and gastrointestinal cancers putatively due to alterations in TGF-β/SMAD signaling [23]. Spectrin is also linked genetically to late-onset Parkinson’s disease and Lewy-body pathology [24,25] as well as other neurodevelopmental syndromes [26]. βIII spectrinopathies include spinocerebellar ataxia type 5 (SCA5) as found in afflicted decedents of Abraham Lincoln [27] and now recognized in several other pedigrees [28]. Other variants in SPTBN2 show cognitive impairment as well as ataxia (spectrin-associated autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia type 1, SPARCA1) [29,30]. CpG hypomethylation of SPTBN2 links to attention deficits in children [31]. Animal models with genetic deletion of βIII spectrin recapitulate these conditions, with demonstrative disruption of the ER and Golgi architecture and selective mis-localization of postsynaptic proteins and excitatory amino acid transporters [11,32]. Defects in βIV spectrin disrupt axonal organization at the nodes of Ranvier and subsequently neurotransmission, and are associated with congenital myopathies and deafness [25,33]. Finally, spectrin βV is required to link myosin VIIA to trafficking vesicles; failure of this linkage leads to progressive hearing loss and blindness in Usher syndrome Type I [34] along with impairment of innervation of the organ of Corti [35].

Defects in αII spectrin also lead to neurologic pathology. Mice lacking αII spectrin are embryonic lethal due to cardiac and nervous system malformations [36]. Mice without αII spectrin in the peripheral nervous system suffer impaired neuronal excitability and axonal defects [37,38]. Human mutations in αII spectrin (SPTAN1) link to early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE) type 5 (West Syndrome), characterized by refractory seizures, intellectual disability, agenesis of the corpus callosum and hypomyelination [38–41]. Other SPTAN1 neurological disorders include juvenile onset hereditary motor neuropathy and hereditary spastic paraplegia [28,42–46].

In recent published work, we describe a novel variant of the murine Sptan1 gene (αII spectrin) with a substitution of Gln for Arg at codon 1098. In heterozygotes this substitution causes a progressive age-dependent ataxia with widespread neurodegeneration [47]. The action of this variant is distinct from other αII spectrin neuropathologic mutations, in that rather than directly disrupting a constitutive ligand-binding or protein-protein interaction (e.g. heterodimer formation, tetramer formation, or actin binding), the mutation alters spectrin’s susceptibility to calcium and calmodulin activated calpain proteolysis, with secondary consequences for its overall function. Beyond the pathways that modulate calpain activity [48], two factors control spectrin’s susceptibility at the substrate level to activated calpain: the calcium-calmodulin dependent exposure of its Y-G residues at position 1176–1177 [49,50], and whether Y1176 is phosphorylated [51,52]. The R1098Q variant spectrin thus represents a novel spectrinopathy that targets a key regulatory site where calcium and tyrosine kinase signal pathways converge to alter spectrin’s function. Beyond the novelty of the R1098Q mutation, the implications of this pathway for understanding other neurodegenerative disorders are significant.

Impaired Spectrin Homeostasis: A Unifying Concept of Neuronal Injury

Inappropriate calcium signaling and activation of calcium activated neutral proteases (calpain) is implicated in a variety of neurologic or degenerative disorders. These include Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease [48,53–55], aging [56,57], and traumatic brain injury [58,59]. The literature is replete with putative calpain targets, and a case can be made that many of these contribute to any given pathology. However, αII spectrin is a major target of calpain attack in all of these conditions, and its cleavage has been widely used as a sensitive measure of neuronal remodeling or neurodegeneration or neurotoxicity. It is an early event in the generation of dark Purkinje cells [60], and calpain-generated breakdown products of spectrin appear in association with amyloid-beta (Aβ deposits and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease patients [61,62]. Spectrin is also a component of the Lewy bodies found in Parkinson’s disease patients, although its state of proteolytic cleavage in the Lewy bodies is undetermined [63]. While the association of spectrin breakdown with disease could simply reflect the end-stage consequences of neuronal injury, we believe this is unlikely based on the global involvement of spectrin in so many cellular processes, and particularly based on our findings with the αII spectrin R1098Q variant [47]. This variant informs us that up-regulation alone of spectrin’s sensitivity to calpain cleavage is sufficient to induce widespread neurodegenerative change and lethal cell injury. It is important to emphasize, this effect is mediated by an enhancement of spectrin’s intrinsic sensitivity to cleavage, not by a global activation of calpain or enhanced Ca++ signaling. While mutations in spectrin remain a rare cause of neurologic disease, processes that perturb intracellular calcium homeostasis and calpain activity are not rare, and accompany many neurodegenerative and other disorders as noted above. It is thus likely that enhanced cellular calpain activity alone, acting on wild-type αII spectrin, will phenocopy the consequences of the R1098Q variant. It will be important in the future to confirm this by determining that a reduction in calpain activity can rescue the R1098Q phenotype. Regardless, the totality of this data suggests that disruption of the spectrin scaffold in neuronal or neurosensory cells may be a common final pathway of neurodegeneration or malfunction.

A Path to Therapy

To the extent that disruption of the neuronal spectrin scaffold is an important factor in the progression of neurologic disease, strategies designed to ameliorate spectrin dysfunction may offer new routes for therapeutic intervention. Inhibition of calpain activity has long been recognized as a potential therapeutic target, and pharmacological calpain inhibitors [64] or over-expression of the natural calpain inhibitor calpastatin [65] prevents or reduces neurodegeneration in murine models. However, recognition that the effects of calpain on the spectrin scaffold can also be regulated at the substrate level opens the door to novel and possibly more specific interventions. One strategy might focus on the phosphorylation of the tyrosine at codon 1176 (Y1176) by a Src family kinase, a post-translational modification that also blocks the calpain cleavage of αII spectrin [51,52]. Designing a therapeutic strategy that either activates such a kinase or inhibits a relevant phosphatase could offer benefit and greater specificity than global calpain suppression. Recently, one study found that Trodusquemine, an inhibitor of tyrosine phosphatase PTB1B that is currently in phase 1–2 clinical trials for obesity, restored synaptic plasticity and improved cognitive function in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease [66,67]. While spectrin was not identified as a target of PTP1B in this study, the enzyme is abundant in brain and any blockage of calpain processing of spectrin by tyrosine phosphorylation at residue 1176 would also impair synaptic plasticity [68,69].

Beyond the action of calpain, the spectrin scaffold as a major organizing and structural hub offers many other putative targets for therapeutic intervention. In Parkinson’s disease models, phosphorylated α-synuclein binds preferentially to spectrin, which removes potentially toxic α-synuclein aggregates [70]. However, the binding of monomeric or oligomeric α-synuclein to spectrin disrupts spectrin-actin dynamics and the membrane-associated periodic skeleton. As seen in most pedigrees with spectrin mutations related to its actin-binding function, disruption of the MPS alone is significantly pathologic. It is interesting to speculate that the end-stage injury in Parkinson’s disease could be related as much to α-synuclein induced damage to the MPS as to the accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates. Since α-synuclein’s affinity for spectrin is enhanced in the Drosophila model by its phosphorylation at serine 129, therapies that limit this phosphorylation might stabilize the MPS and enhance neuronal survival.

There are many other regulated interactions of the spectrin scaffold with its various partners, and more no doubt await discovery. Some examples include complex allosteric interactions that link membrane binding to its self-association properties [71,72], post-translational regulation controlling its interaction with calmodulin-regulated kinases (CaMKII) [73–75], its control of calcium-regulated exocytosis [76], phosphorylation control of its stabilization of specific organelles [6,7], and its interaction with long non-coding RNA’s (lncRNA) responsible for activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons [77]. If indeed as we have postulated that damage to the spectrin scaffold is a crucial final pathway in a broad spectrum of neuronal pathologies, then strategies designed to stabilize this structure may offer truly new approaches to their treatment.

Conclusion

From its humble beginnings as a cytoskeletal protein originally thought to be unique to the red cell, the spectrin scaffold has emerged as a central component of diverse signaling systems and a crucial member of pathways that control cellular organization, size, and function. This is most apparent in the nervous system. Defects in the spectrin scaffold lead to diverse neurodevelopmental and acquired disorders. The recent identification of an unusual αII spectrin defect in a murine model that renders it uniquely hypersensitive to calcium-mediated calpain processing indicates that damage to the spectrin skeleton alone is sufficient to generate a severe ataxic phenotype with widespread neurodegenerative change [47]. Increasing evidence indicates that diverse neurodegenerative and acquired conditions including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, several ataxias, and traumatic brain injury all involve damage to the spectrin scaffold. Thus, an attractive hypothesis is that disruption of the neuronal spectrin scaffold represents a common end-stage event in such disorders. Therapeutic strategies focused on preservation of spectrin’s function may thus offer novel approaches to the treatment of many neurodegenerative conditions.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health PO1-NS35476 (project 4, JSM) and R01-HL28560 (JSM) and by the Raymond Yesner Endowment to Yale University.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Xu K, Zhong G, Zhuang X. Actin, spectrin, and associated proteins form a periodic cytoskeletal structure in axons. Science. 2013. Jan 25; 339(6118):452–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng H, Wang W, Yu J, Zheng Y, Qing Y, Pan D. Spectrin regulates Hippo signaling by modulating cortical actomyosin activity. Elife. 2015. Mar 31; 4:e06567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muresan V, Stankewich MC, Steffen W, Morrow JS, Holzbaur EL, Schnapp BJ. Dynactin-dependent, dynein-driven vesicle transport in the absence of membrane proteins: a role for spectrin and acidic phospholipids. Molecular Cell. 2001. Jan 1; 7(1):173–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holleran EA, Ligon LA, Tokito M, Stankewich MC, Morrow JS, Holzbaur EL. βIII spectrin binds to the Arp1 subunit of dynactin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001. Sep 28; 276(39):36598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeda S, Yamazaki H, Seog DH, Kanai Y, Terada S, Hirokawa N. Kinesin superfamily protein 3 (KIF3) motor transports fodrin-associating vesicles important for neurite building. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2000. Mar 20; 148(6):1255–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddhanta A, Radulescu A, Stankewich MC, Morrow JS, Shields D. Fragmentation of the golgi apparatus: a role for βIII spectrin and synthesis of phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003. Jan 17; 278(3):1957–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godi A, Santone I, Pertile P, Devarajan P, Stabach PR, Morrow JS, et al. ADP ribosylation factor regulates spectrin binding to the Golgi complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998. Jul 21; 95(15):8607–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salcedo-Sicilia L, Granell S, Jovic M, Sicart A, Mato E, Johannes L, et al. βIII spectrin regulates the structural integrity and the secretory protein transport of the Golgi complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013. Jan 25; 288(4):2157–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stankewich MC, William TT, Peters LL, Ch’ng Y, John KM, Stabach PR, et al. A widely expressed βIII spectrin associated with Golgi and cytoplasmic vesicles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998. Nov 24;95(24):14158–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devarajan P, Stabach PR, De Matteis MA, Morrow JS. Na, K-ATPase transport from endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi requires the Golgi spectrin–ankyrin G119 skeleton in Madin Darby canine kidney cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1997. Sep 30; 94(20):10711–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stankewich MC, Gwynn B, Ardito T, Ji L, Kim J, Robledo RF, et al. Targeted deletion of βIII spectrin impairs synaptogenesis and generates ataxic and seizure phenotypes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010. Mar 30; 107(13):6022–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Matteis MA, Morrow JS. Spectrin tethers and mesh in the biosynthetic pathway. Journal of Cell Science. 2000. Jul 1; 113(13):2331–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng H, Yang L, Wen P, Lei H, Blount P, Pan D. Spectrin couples cell shape, cortical tension, and Hippo signaling in retinal epithelial morphogenesis. Journal of Cell Biology. 2020. Apr 6; 219(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher GC, Elbediwy A, Khanal I, Ribeiro PS, Tapon N, Thompson BJ. The Spectrin cytoskeleton regulates the Hippo signalling pathway. The EMBO Journal. 2015. Apr 1; 34(7):940–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antón IM, Wandosell F. WIP, YAP/TAZ and Actin Connections Orchestrate Development and Transformation in the Central Nervous System. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021. Jun 14; 9:1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahu MR, Mondal AC. The emerging role of Hippo signaling in neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2020. May; 98(5):796–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machnicka B, Czogalla A, Hryniewicz-Jankowska A, Bogusławska DM, Grochowalska R, Heger E, et al. Spectrins: a structural platform for stabilization and activation of membrane channels, receptors and transporters. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes. 2014. Feb 1; 1838(2):620–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griswold AJ, Ma D, Sacharow SJ, Robinson JL, Jaworski JM, Wright HH, et al. A de novo 1.5 Mb microdeletion on chromosome 14q23. 2–23.3 in a patient with autism and spherocytosis. Autism Research. 2011. Jun; 4(3):221–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lybaek H, Øyen N, Fauske L, Houge G. A 2.1 Mb deletion adjacent but distal to a 14q21q23 paracentric inversion in a family with spherocytosis and severe learning difficulties. Clinical Genetics. 2008. Dec; 74(6):553–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCann SR, Jacob HS. Spinal cord disease in hereditary spherocytosis: report of two cases with a hypothesized common mechanism for neurologic and red cell abnormalities. Blood. 1976. Aug 1; 48(2):259–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang Y, Katuri V, Dillner A, Mishra B, Deng CX, Mishra L. Disruption of transforming growth factor-β signaling in ELF β-spectrin-deficient mice. Science. 2003. Jan 24; 299(5606):574–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golestaneh N, Tang Y, Katuri V, Jogunoori W, Mishra L, Mishra B. Cell cycle deregulation and loss of stem cell phenotype in the subventricular zone of TGF-β adaptor elf−/− mouse brain. Brain Research. 2006. Sep 7; 1108(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SS, Shetty K, Katuri V, Kitisin K, Baek HJ, Tang Y, et al. TGF-β signaling pathway inactivation and cell cycle deregulation in the development of gastric cancer: Role of the β-spectrin, ELF. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006. Jun 16; 344(4):1216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peuralinna T, Myllykangas L, Oinas M, Nalls MA, Keage HA, Isoviita VM, et al. Genome-wide association study of neocortical Lewy-related pathology. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 2015. Sep; 2(9):920–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knierim E, Gill E, Seifert F, Morales-Gonzalez S, Unudurthi SD, Hund TJ, et al. A recessive mutation in beta-IV-spectrin (SPTBN4) associates with congenital myopathy, neuropathy, and central deafness. Human Genetics. 2017. Jul; 136(7):903–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cousin MA, Creighton BA, Breau KA, Spillmann RC, Torti E, Dontu S, et al. Pathogenic SPTBN1 variants cause an autosomal dominant neurodevelopmental syndrome. Nature Genetics. 2021. Jul 1:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeda Y, Dick KA, Weatherspoon MR, Gincel D, Armbrust KR, Dalton JC, et al. Spectrin mutations cause spinocerebellar ataxia type 5. Nature Genetics. 2006. Feb; 38(2):184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Syrbe S, Harms FL, Parrini E, Montomoli M, Mütze U, Helbig KL, et al. Delineating SPTAN1 associated phenotypes: from isolated epilepsy to encephalopathy with progressive brain atrophy. Brain. 2017. Sep 1; 140(9):2322–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yıldız Bölükbaşı E, Afzal M, Mumtaz S, Ahmad N, Malik S, Tolun A. Progressive SCAR14 with unclear speech, developmental delay, tremor, and behavioral problems caused by a homozygous deletion of the SPTBN2 pleckstrin homology domain. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2017. Sep; 173(9):2494–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lise S, Clarkson Y, Perkins E, Kwasniewska A, Sadighi Akha E, Parolin Schnekenberg R, et al. Recessive mutations in SPTBN2 implicate β-III spectrin in both cognitive and motor development. PLoS Genetics. 2012. Dec 6; 8(12):e1003074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li SC, Kuo HC, Huang LH, Chou WJ, Lee SY, Chan WC, et al. DNA Methylation in LIME1 and SPTBN2 Genes Is Associated with Attention Deficit in Children. Children. 2021. Feb; 8(2):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perkins EM, Clarkson YL, Sabatier N, Longhurst DM, Millward CP, Jack J, et al. Loss of β-III spectrin leads to Purkinje cell dysfunction recapitulating the behavior and neuropathology of spinocerebellar ataxia type 5 in humans. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010. Apr 7; 30(14):4857–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buelow M, Süßmuth D, Smith LD, Aryani O, Castiglioni C, Stenzel W, et al. Novel bi-allelic variants expand the SPTBN4-related genetic and phenotypic spectrum. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2021. Mar 26:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papal S, Cortese M, Legendre K, Sorusch N, Dragavon J, Sahly I, et al. The giant spectrin βV couples the molecular motors to phototransduction and Usher syndrome type I proteins along their trafficking route. Human Molecular Genetics. 2013. Sep 15; 22(18):3773–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stankewich MC, Bai J-P, Stabach PR, Khan S, Tan WJT, Surguchev A, et al. Outer hair cell function is normal in beta V spectrin knockout mice. BioRxiv. 2021. Aug 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stankewich MC, Cianci CD, Stabach PR, Ji L, Nath A, Morrow JS. Cell organization, growth, and neural and cardiac development require αII-spectrin. Journal of Cell Science. 2011. Dec 1; 124(23):3956–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang CY, Zhang C, Zollinger DR, Leterrier C, Rasband MN. An αII spectrin-based cytoskeleton protects large-diameter myelinated axons from degeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 2017. Nov 22; 37(47):11323–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Ji T, Nelson AD, Glanowska K, Murphy GG, Jenkins PM, et al. Critical roles of αII spectrin in brain development and epileptic encephalopathy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2018. Feb 1; 128(2):760–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saitsu H, Tohyama J, Kumada T, Egawa K, Hamada K, Okada I, et al. Dominant-negative mutations in α-II spectrin cause West syndrome with severe cerebral hypomyelination, spastic quadriplegia, and developmental delay. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2010. Jun 11; 86(6):881–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Writzl K, Primec ZR, Stražišar BG, Osredkar D, Pečarič-Meglič N, Kranjc BS, et al. Early onset West syndrome with severe hypomyelination and coloboma-like optic discs in a girl with SPTAN1 mutation. Epilepsia. 2012. Jun; 53(6):e106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rapaccini V, Esposito S, Strinati F, Allegretti M, Manfroi E, Miconi F, et al. A Child with a c. 6923_6928dup (p. Arg2308_Met2309dup) SPTAN1 mutation associated with a severe early infantile epileptic encephalopathy. International journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018. Jul; 19(7):1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tohyama J, Nakashima M, Nabatame S, Miyata R, Rener-Primec Z, Kato M, et al. SPTAN1 encephalopathy: distinct phenotypes and genotypes. Journal of Human Genetics. 2015. Apr; 60(4):167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamdan FF, Saitsu H, Nishiyama K, Gauthier J, Dobrzeniecka S, Spiegelman D, et al. Identification of a novel in-frame de novo mutation in SPTAN1 in intellectual disability and pontocerebellar atrophy. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2012. Jul; 20(7):796–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beijer D, Deconinck T, De Bleecker JL, Dotti MT, Malandrini A, Urtizberea JA, et al. Nonsense mutations in alpha-II spectrin in three families with juvenile onset hereditary motor neuropathy. Brain. 2019. Sep 1;142(9):2605–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gartner V, Markello TC, Macnamara E, De Biase A, Thurm A, Joseph L, et al. Novel variants in SPTAN1 without epilepsy: an expansion of the phenotype. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2018. Dec; 176(12):2768–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leveille E, Estiar MA, Krohn L, Spiegelman D, Dionne-Laporte A, Dupré N, et al. SPTAN1 variants as a potential cause for autosomal recessive hereditary spastic paraplegia. Journal of Human Genetics. 2019. Nov; 64(11):1145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miazek A, Zalas M, Skrzymowska J, Bogin BA, Grzymajło K, Goszczynski TM, et al. Age-dependent ataxia and neurodegeneration caused by an αII spectrin mutation with impaired regulation of its calpain sensitivity. Scientific Reports. 2021. Mar 31; 11(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahaman YA, Huang F, Kessete Afewerky H, Maibouge TM, Ghose B, Wang X. Involvement of calpain in the neuropathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Medicinal Research Reviews.2019. Mar; 39(2):608–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris AS, Croall DE, Morrow JS. Calmodulin regulates fodrin susceptibility to cleavage by calciumdependent protease I. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989. Oct 15; 264(29):17401–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris AS, Morrow JS. Calmodulin and calciumdependent protease I coordinately regulate the interaction of fodrin with actin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1990. Apr 1; 87(8):3009–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nedrelow JH, Cianci CD, Morrow JS. C-Src binds αII Spectrin’s Src homology 3 (SH3) domain and blocks calpain susceptibility by phosphorylating Tyr1176. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003. Feb 28; 278(9):7735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicolas G, Fournier CM, Galand C, Malbert-Colas L, Bournier O, Kroviarski Y, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates alpha II spectrin cleavage by calpain. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002. May 15; 22(10):3527–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmad F, Das D, Kommaddi RP, Diwakar L, Gowaikar R, Rupanagudi KV, et al. Isoform-specific hyperactivation of calpain-2 occurs presymptomatically at the synapse in Alzheimer’s disease mice and correlates with memory deficits in human subjects. Scientific Reports. 2018. Sep 3; 8(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muruzheva ZM, Traktirov DS, Zubov AS, Pestereva NS, Tikhomirova MS, Karpenko MN. Calpain activity in plasma of patients with essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Neurological Research. 2021. Apr 3; 43(4):314–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamashima T Reconsider Alzheimer’s disease by the ‘calpain–cathepsin hypothesis’—A perspective review. Progress in Neurobiology. 2013. Jun 1; 105:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zaidi A Plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases: Targets of oxidative stress in brain aging and neurodegeneration. World Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010. Sep 26; 1(9):271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hajieva P, Kuhlmann C, Luhmann HJ, Behl C. Impaired calcium homeostasis in aged hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 2009. Feb 20; 451(2):119–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gan ZS, Stein SC, Swanson R, Guan S, Garcia L, Mehta D, et al. Blood biomarkers for traumatic brain injury: a quantitative assessment of diagnostic and prognostic accuracy. Frontiers in Neurology. 2019. Apr 26; 10:446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, Liu Y, Lopez D, Lee M, Dayal S, Hurtado A, et al. Protection against TBI-induced neuronal death with post-treatment with a selective calpain-2 inhibitor in mice. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2018. Jan 1; 35(1):105–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mansouri B, Henne WM, Oomman SK, Bliss R, Attridge J, Finckbone V, et al. Involvement of calpain in AMPA-induced toxicity to rat cerebellar Purkinje neurons. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2007. Feb 28; 557(2–3):106–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sihag RK, Cataldo AM. Brain β-spectrin is a component of senile plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain research. 1996. Dec 16; 743(1–2):249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Czogalla A, Sikorski AF. Spectrin and calpain: a ‘target’and a ‘sniper’in the pathology of neuronal cells. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences CMLS. 2005. Sep; 62(17):1913–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leverenz JB, Umar I, Wang Q, Montine TJ, McMillan PJ, Tsuang DW, et al. Proteomic identification of novel proteins in cortical lewy bodies. Brain Pathology. 2007. Apr;17(2):139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hassen GW, Kesner L, Stracher A, Shulman A, Rockenstein E, Mante M, et al. Effects of novel calpain inhibitors in transgenic animal model of Parkinson’s disease/dementia with Lewy bodies. Scientific Reports. 2018. Dec 27; 8(1):1–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rao MV, McBrayer MK, Campbell J, Kumar A, Hashim A, Sershen H, et al. Specific calpain inhibition by calpastatin prevents tauopathy and neurodegeneration and restores normal lifespan in tau P301L mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2014. Jul 9; 34(28):9222–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ricke KM, Cruz SA, Qin Z, Farrokhi K, Sharmin F, Zhang L, et al. Neuronal protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B hastens amyloid β-associated Alzheimer’s disease in mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2020. Feb 12; 40(7):1581–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang L, Qin Z, Sharmin F, Lin W, Ricke KM, Zasloff M, et al. Tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B impairs presynaptic NMDA receptor-mediated plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2021. May 24:105402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lynch G, Baudry M. Brain spectrin, calpain and long-term changes in synaptic efficacy. Brain Research Bulletin. 1987. Jun 1; 18(6):809–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glantz SB, Cianci CD, Iyer R, Pradhan D, Wang KK, Morrow JS. Sequential degradation of αII and βII spectrin by calpain in glutamate or maitotoxin-stimulated cells. Biochemistry. 2007. Jan 16; 46(2):502–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ordonez DG, Lee MK, Feany MB. α-synuclein induces mitochondrial dysfunction through spectrin and the actin cytoskeleton. Neuron. 2018. Jan 3; 97(1):108–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giorgi M, Cianci CD, Gallagher PG, Morrow JS. Spectrin oligomerization is cooperatively coupled to membrane assembly: a linkage targeted by many hereditary hemolytic anemias?. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2001. Jun 1; 70(3):215–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cianci CD, Giorgi M, Morrow JS. Phosphorylation of ankyrin down-regulates its cooperative interaction with spectrin and protein 3. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1988. Jul; 37(3):301–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kline CF, Wright PJ, Koval OM, Zmuda EJ, Johnson BL, Anderson ME, et al. βIV-Spectrin and CaMKII facilitate Kir6. 2 regulation in pancreatic beta cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013. Oct 22;110(43):17576–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hund TJ, Koval OM, Li J, Wright PJ, Qian L, Snyder JS, et al. A β IV-spectrin/CaMKII signaling complex is essential for membrane excitability in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010. Oct 1; 120(10):3508–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nassal DM, Patel NJ, Unudurthi SD, Shaheen R, Yu J, Mohler PJ, et al. Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II–dependent regulation of βIV-spectrin modulates cardiac fibroblast gene expression, proliferation, and contractility. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2021. Jun 18:100893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Houy S, Nicolas G, Momboisse F, Malacombe M, Bader MF, Vitale N, et al. αII-spectrin controls calcium-regulated exocytosis in neuroendocrine chromaffin cells through neuronal Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome protein interaction. IUBMB life. 2020. Apr;72(4):544–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grinman E, Nakahata Y, Avchalumov Y, Espadas I, Swarnkar S, Yasuda R, et al. Activity-regulated synaptic targeting of lncRNA ADEPTR mediates structural plasticity by localizing Sptn1 and AnkB in dendrites. Science Advances. 2021. Apr 1;7(16):eabf0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019. Jan 8; 47(D1):D607–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]