Abstract

Deltamethrin (DLM) is a Type II pyrethroid pesticide widely used in agriculture, homes, public spaces, and medicine. Epidemiological studies report that increased pyrethroid exposure during development is associated with neurobehavioral disorders. This raises concern about the safety of these chemicals for children. Few animal studies have explored the long-term effects of developmental exposure to DLM on the brain. Here we review the CNS effects of pyrethroids, with emphasis on DLM. Current data on behavioral and cognitive effects after developmental exposure are emphasized. Although, the acute mechanisms of action of DLM are known, how these translate to long-term effects is only beginning to be understood. But existing data clearly show there are lasting effects on locomotor activity, acoustic startle, learning and memory, apoptosis, and dopamine in mice and rats after early exposure. The most consistent neurochemical findings are reductions in the dopamine transporter and the dopamine D1 receptor. The data show that DLM is developmentally neurotoxic but more research on its mechanisms of long-term effects is needed.

Keywords: pyrethroids, deltamethrin, permethrin, developmental neurotoxicity, learning and memory

1. Introduction

Deltamethrin (DLM) is a Type II pyrethroid pesticide used worldwide in agricultural, medical, and household applications. As the use of pyrethroids increases, more people, including children, are exposed. There are epidemiological studies reporting associations between childhood pyrethroid exposure and neurodevelopmental disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and developmental delay (DD) (Oulhote and Bouchard, 2013; Shelton et al., 2014; Wagner-Schuman, 2015; Xue et al., 2013). Despite the human evidence, there are few studies on long-term pyrethroid effects in preclinical developmental models to identify potential mechanisms (Aziz et al., 2001; Hossain, 2015; Johri et al., 2006; Pitzer, 2019; Richardson, 2015). While much is known about pyrethroid mechanism of poisoning, little is known about possible mechanisms of long-term effects. Of the many pyrethroids, DLM is one of the most investigated and is the principal focus of this review. But before reviewing the animal data on the developmental neurotoxicity of DLM, we summarize the findings in children to help put the animal data in context.

2. Humans

People are exposed to pyrethroids because of their widespread use in agriculture, households, schools, parks, apartments, and work settings to exterminate insects and prevent insect intrusion. Pyrethroids are also applied to children for head lice and to pets for flea and tick control. Most insect sprays and termiticides contain pyrethroids. Pest management companies report using approximately 1.7 million lbs of pyrethroids (~30,000 lbs of DLM) for household pests and over 1.1 million lbs of pyrethroids for lawn and landscape care (EPA, 2020). People are also exposed to pyrethroid residues in food, particularly on fruits and vegetables. In addition, ~200,000 lbs of pyrethroids (10,000 lbs. of DLM) are used for food handling, ~7,600 lbs of DLM to treat crops, and ~1,600 lbs to treat stored grains. The use of pyrethroids in agriculture is widespread and increasing as older compounds are replaced. During the early 2000s the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began phasing out some organophosphate pesticides due to their toxicity. This resulted in increased use of pyrethroids (Oros and Werner, 2005; Williams et al., 2008). Human exposure to pyrethroids is ubiquitous, including to pregnant women and children (Berkowitz et al., 2003; Heudorf et al., 2004; Schettgen et al., 2002; Whyatt et al., 2002). However, an understanding of the developmental effects of pyrethroids is limited, which makes developing a thorough risk assessment more difficult. In regulating pesticide exposures, the EPA uses animal data, such as data from a developmental neurotoxicity study and applies uncertainty factors of 1, 3, or 10-fold below the no observable adverse effect level or the benchmark dose-low set at 2.5, 5, or 10% below the benchmark dose response. Three uncertainty factors are normally used. One for within species variability, one for cross-species variability, and one for human inter-individual differences. In addition, the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA, 1996) requires an additional 10X uncertainty factor if susceptible subpopulations are identified. The most common reason for this imposed uncertainty factor is when there is evidence of increased prenatal or neonatal susceptibility compared with adults. Here we review evidence that embryos, fetuses, and children are more susceptible to DLM than adults. However, there is insufficient evidence to make similar comparisons for most of the pyrethroids.

Although pesticides are beneficial in controlling agricultural and disease-bearing pests, they pose differential risks to fetuses and children compared with adults. Developing brains are more vulnerable because of the many cellular changes occurring as these processes unfold that can potentially be permanently altered. In addition, children have greater contact with their surroundings than adults. This is from increased contact with environmental surfaces and greater hand-to-mouth behavior than occurs in adults. Children also have less mature blood brain barriers (BBBs) and slower rates of clearance because of immature metabolizing enzymes than adults (Allegaert and van den Anker, 2019; Amaraneni et al., 2017a; Anand, S.S., Kim, K. B., Padilla, S., Muralidhara, S., Kim, H. J., Fisher, J. W., Bruckner, J. V., 2006; Chen et al., 2015; Mortuza et al., 2018). Children also have less body fat to sequester compounds, greater free fractions in circulation because of less plasma protein binding; and ongoing brain development, including proliferation, migration, synaptogenesis, gliogenesis, apoptosis, myelination, and activity-dependent connectivity, processes that are more susceptible to perturbation than in mature brains. This vulnerability begins during organogenesis; extends through the fetal period to birth; and postnatally through childhood, adolescence, and into early adulthood in humans as the brain fully develops. Any of the developmental processes occurring during these stages has the potential to be disrupted by toxic substances (Baloch et al., 2009; Bockhorst et al., 2008; Catalani et al., 2002; Cowan, 1979; Dobbing and Sands, 1979; Gottlieb et al., 1977; Hedner et al., 1986; Jiang and Nardelli, 2016; Miller and Gauthier, 2007; Romijn et al., 1991). Collectively, these factors indicate that prenatal and postnatal brain development are susceptible periods, an idea amply supported by the many studies on the long-term consequences of developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls, lead, manganese, methylmercury, arsenic, organophosphate pesticides, and other environmental agents. Such data lead to the question of how safe are pyrethroids during brain ontogeny?

Epidemiological studies in children use standardized neurodevelopmental and neuropsychological tests in combination with urinary pyrethroid metabolites or other surrogate indices of exposure to compare neurodevelopmental disorders and pyrethroid exposure. A common pyrethroid urinary metabolite is 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA). 3-PBA is the most widely used biomarker of pyrethroids but is less than ideal because it is non-specific since it is also a metabolite of Type I pyrethroids such as permethrin. Somewhat more specific metabolites are cis- and trans-DCCA (3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethylycyclopropane carboxylic acid) for permethrin, cypermethrin, and cyfluthrin (Chrustek, Agnieszka et al., 2018; Meeker et al., 2009). A metabolite specific for DLM is urinary cis-DBCA (cis-3-(2,2-dibromovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropane carboxylic acid) (Barr et al., 2010; Chrustek, A. et al., 2018). Another metabolite of DLM and other Type II pyrethroids, cyfluthrin and α-cypermethrin, is 4-F-3-PBA (4-fluoro-3-phenoxybenzoic acid) (Chrustek, Agnieszka et al., 2018). The 4th National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals compiles data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The most recent tables (1999-2010) reported 3-PBA levels in the population to be higher in more recent years than in 1999, 95th percentile and 95% confidence interval (CDC, 2019):

4.33 μg/L (2.62-6.30 μg/L; N=1998) for 1999-2000

3.54 μg/L (2.69-5.25 μg/L; N=3048) for 2001-2002

6.63 μg/L (4.99-8.24 μg/L; N=2454) for 2007-2008

6.50 μg/L (5.57-8.04 μg/L; N=2723) for 2009-2010

In addition, from the same report, 3-PBA levels in urine are higher in children than in adolescents or adults (2009-2010), ages:

6-11 = 8.51 μg/L (4.12-39.4 μg/L; N=383)

12-19 = 3.92 μg/L (2.55-5.85 μg/L; N=398)

20-59 = 6.95 μg/L (5.57-9.31 μg/L: N=1296)

60+ = 5.93 μg/L (3.21-8.95 μg/L: N=646)

The 3-PBA levels recorded from the NHANES differed across cycles. When observing levels of 3-PBA from 2007-2012, levels were the highest in the 2011-2012 NHANES cycle. Geometric mean of 3-PBA levels (Lehmler et al., 2020) are as follows:

Adults:

0.41 μg/L in 2007-2008

0.41 μg/L in 2009-2010

0.66 μg/L in 2011-2012

Children:

0.40 μg/L in 2007-2008

0.46 μg/L in 2009-2010

0.70 μg/L in 2011-2012

These data indicate that exposure to pyrethroids remains a public health concern. It will be critical to observe these metabolite levels as more recent measures from large scale studies, such as the NHANES, become available. However, the non-specificity of commonly used pyrethroid metabolites limits the interpretation of much of the human epidemiological data. Nevertheless, such data suggest that children chronically exposed to pyrethroids have compromised outcomes.

Data from the 1999-2002 NHANES have been used to search for associations between pyrethroid exposures and outcomes in children. A study that used NHANES parental report data that their children have ADHD or from records of prescriptions for ADHD medications, in conjunction with urinary 3-PBA levels showed an association between pyrethroid exposure and ADHD (Richardson et al., 2015). Using a nested case-control analysis for correlations between pyrethroid exposure and ADHD, a modest but significant association between urinary 3-PBA and ADHD prevalence was found. The study was based on 5489 children 6-15 years of age in which 9.2% had ADHD based on parental reports (Bouchard et al., 2010; Braun et al., 2006; Richardson et al., 2015). Of the 5489 ADHD cases, 3-PBA levels were available for 2123 and these concentrations were associated with ADHD with an odds ratio of 2.3 (1.4-3.9) (Richardson et al., 2015). No sex differences in this association were found.

NHANES data were also used in a study by Wagner-Schuman et al. (2015). Based on urinary 3-PBA data and diagnosis of ADHD (Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition or diagnosis by professionals with experience assessing ADHD), an association was found between pyrethroid exposure and ADHD in 687 children (ages 8-15; 2001-2002 NHANES) (Wagner-Schuman, 2015). Boys with urinary 3-PBA levels above background were twice as likely to be diagnosed with ADHD compared with boys with undetectable 3-PBA levels; no such association was found for girls (Wagner-Schuman, 2015). Wagner-Schuman et al. (2015) reported that for every 10-fold increase in metabolite there was a 50% increase in hyperactivity and impulsivity prevalence but no association with inattention. Overall, the data from the NHANES database reported in these studies indicate an increased likelihood of ADHD associated with elevated pyrethroid exposure.

The Childhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment (CHARGE) project is a population based case-control study testing factors associated with ASD (Hertz-Picciotto et al., 2006). Shelton et al. (2014) used data from the CHARGE project, including parental questionnaires about symptoms, exposures, and residential location to search for pesticide associations with ASD. The authors found an association between pesticide application locations, determined from California’s regional pesticide use database, and residential proximity of study participants to where exposed and non-exposed women lived during pregnancy. Using the geographical location, the authors’ determined whether there was an association between proximity to pesticide registrations and a child’s diagnoses with ASD or DD (Shelton et al., 2014). A third of the children lived within 1.5 km of where agricultural pesticides were registered for use, of which pyrethroids were the second most widely used pesticide after organophosphates. Children diagnosed with ASD (N=486; age 36.7 ± 9.7 months) were compared with typically developing children (N= 316; age 36.9 ± 8.9 months) and children with DD (N=168; age 38.3 ± 8.9 months) (Shelton et al., 2014). Children were matched for age, sex, and location. Shelton et al. (2014) found an association between preconception and third trimester pyrethroid and organophosphate exposure and increased prevalence of ASD. They also found an association between third trimester pesticide exposure and DD prevalence (Shelton et al., 2014). The dual association of pyrethroids and organophosphates on ASD prevalence makes it impossible to segregate which pesticide has the larger association beyond the slight trimester relationship, nor could the pyrethroids be separately sorted out. Shelton et al. (2014) did note that the ASD risk was largest after third-trimester exposure for pyrethroid exposure (odds ratio = 2.0; 95% Cl: 1.1, 3.6), but after second trimester it was larger for chlorpyrifos (odds ratio = 3.3; 95% Cl: 1.5, 7.4). The study did not obtain urinary pyrethroid metabolite measurements. Nevertheless, this study, along with those described earlier are consistent in finding that prenatal or postnatal pyrethroid exposure is associated with neurodevelopmental disorders (Richardson, 2015; Shelton et al., 2014; Wagner-Schuman, 2015).

Another dataset used to assess early life pyrethroid exposure and its outcomes was the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS). The CHMS (cycle 1, 2007-2009) used multistage probability sampling and oversampling of selected groups to generate a balanced study sample (Oulhote and Bouchard, 2013). Data were collected from 1,081 children ages 6-11 years. Urine samples were assessed for pyrethroid metabolites. Caregivers completed surveys covering each child’s behavior using the parent version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997), as well as questions about pesticide use. Cis- and trans-DCCA urinary metabolites were associated with higher scores of difficult behavior on the SDQ (Oulhote and Bouchard, 2013). Type I pyrethroids, such as permethrin, and Type II pyrethroids, such as cypermethrin and cyfluthrin, generate DCCA metabolites (Barr et al., 2010), and implicate pyrethroids in long-term effects on behavior. DCCA is not a metabolite of DLM, therefore, this study implicates non-DLM pyrethroids as compromising children’s behavioral development. However, in an unweighted analysis of the data, 3-PBA levels and girls with high scores for conduct problems resulted in a significant association (adjusted odds ratio = 2.2; 95% CI: 1.0, 4.9) but not for boys (adjusted odds ratio = 0.6; 95% CI: 0.3, 1.4) (Oulhote and Bouchard, 2013). 3-PBA is a general metabolite for many pyrethroids, which limits specificity of this result since both Type I and Type II pyrethroids can be monitored by 3-PBA levels (Barr et al., 2010). Levels of cis-DBCA and 4-F-3-PBA, metabolites of DLM and cyfluthrin, respectively, were below the limit of detection in > 50% of the children in this study (Oulhote and Bouchard, 2013), making tests of association impossible to determine.

A study done in Jiaozuo, China in 2010 examined the effects of pyrethroids on children’s growth and development in infancy after prenatal pyrethroid exposure (Xue et al., 2013). The authors enrolled 497 mother-infant pairs and collected urine once during pregnancy (Xue et al., 2013). At one year of age, infants were assessed for physical, neurological, and mental development using the Development Screen Test (DST) (Xue et al., 2013). The DST assesses movement, social adaptation, inferred intelligence, and a mental development index. Levels of pyrethroid metabolites in maternal urine were negatively correlated with intellectual development (Xue et al., 2013). Other factors, such as the mother’s age, education, place of residence, and disease status, also correlated with lower developmental quotients by multiple linear regression analysis (Xue et al., 2013). This study implicates pyrethroids in lowering early intellectual development but follow up data at older ages will be important for interpreting the early life exposure as a predictor of later outcomes.

These studies were reviewed elsewhere (Burns and Pastoor, 2018). These authors note that the epidemiological studies have limitations. Burns and Pastoor highlight that these studies were all cross-sectional, rather than prospective and longitudinal, and all used non-specific urinary metabolites, including only measuring them once. These limitations prevent any conclusions about the effects of pyrethroids on neurodevelopment. However, the inverse association between pyrethroid metabolites and neurological development, while concerning, hint at neuropsychological short-falls in exposed children that should not be ignored. Until there are more human data, animal data are the best source of information about developmental effects. Before reviewing these data, pyrethroid biology is first reviewed.

3. Classification

Pyrethroids are synthetic derivatives of pyrethrin, which comes from chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium). However, pyrethrins are unstable in light, therefore chemists modified their structures to produce more potent and stable insecticides. Pyrethroids are classified by structure, symptoms, and/or ion channel targets.

I. Classification by structure

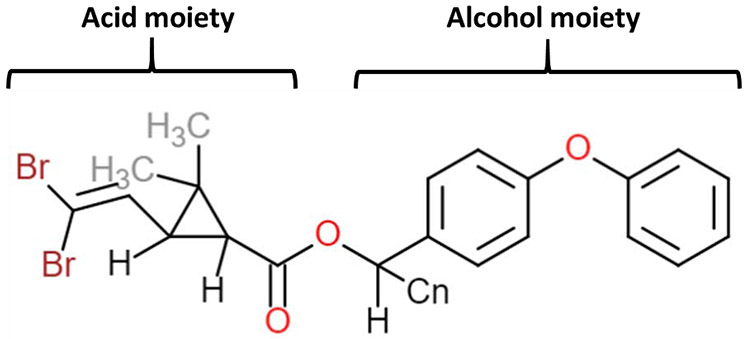

There are two main classes, Type I and Type II. Type I pyrethroids lack a cyano moiety at the alpha-position, whereas Type II pyrethroids contain this group (Gammon et al., 1981; Scott and Matsumura, 1983; Soderlund and Bloomquist, 1989; Soderlund et al., 2002). Pyrethroids share alcohol and acid moieties and a central ester bond (Figure 1). Most pyrethroids are stereoisomers because the acid moiety contains two chiral carbons, and the alcohol group has one chiral carbon. Hence, there can be up to eight stereoisomers for some pyrethroids (Perez-Fernandez et al., 2010) and chirality affects toxicity (Chapman, 1983). In general, cis isomers are more toxic than trans isomers (Rickard and Brodie, 1985). DLM lacks a trans isomer and exists only in a cis configuration (Elliott et al., 1974), suggesting greater toxicity per molecule.

Figure 1:

Chemical structure of the Type II pyrethroid DLM. Pyrethroids contain an alcohol and acid moiety that are connected by an ester bond. Many pyrethroids have various isomeric forms, however, DLM exists only as a cis isomer.

II. Classification by symptoms

At high doses, Type I and II pyrethroids induce different symptoms or syndromes (Kaneko, 2010; Narahashi, 1996; Shafer and Meyer, 2004; Shafer et al., 2005; Soderlund, D. M., 2012; Soderlund et al., 2002). In insects pyrethroids induce uncoordinated movements, convulsions, paralysis, and death (Soderlund and Bloomquist, 1989). In mammals, Type I pyrethroids, such as permethrin, at high doses produce tremors or T syndrome; consisting of fine tremors that become course as dose is increased, along with prostration, and sensitivity to stimuli (Shafer et al., 2005; Soderlund and Bloomquist, 1989). High doses of Type II pyrethroids in mammals produce choreoathetosis and salivation or CS syndrome that includes writhing, salivation, pawing, burrowing, tremors, and clonic seizures (Shafer et al., 2005; Soderlund and Bloomquist, 1989). Pyrethroids with overlapping CS and T symptoms are designated mixed or Type III pyrethroids (Shafer et al., 2005; Soderlund et al., 2002; Verschoyle and Aldridge, 1980).

III. Classification by receptor

i. Sodium channels

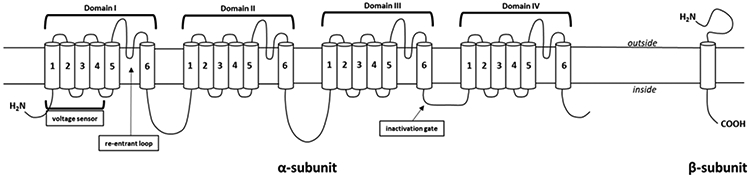

A third classification is by receptor binding or target. The principal binding site of pyrethroids is on the α-subunit of voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSC), which makes up the central pore of the channel as well as contains regions for voltage sensing and ion selectivity (Davies et al., 2007; Du et al., 2009; Field et al., 2017; Narahashi, 2000; Silver et al., 2014; Soderlund and Bloomquist, 1989; Wang and Wang, 2003). VGSCs are composed of an α- (220–260 kDa) and one or more β subunits (30–40 kDa) (Aman et al., 2009; Cestele and Catterall, 2000; Isom et al., 1992; Isom et al., 1995; Morgan et al., 2000; Patino and Isom, 2010; Zhang, Fan et al., 2013). The α-subunit of the VGSC shares homology with other voltage dependent channels (i.e., calcium and potassium channels), however, the β-subunits are homologous to neural cell adhesion molecules (Catterall, 2000a). β-subunits are involved in the kinetics and voltage dependence of VGSC, as well as modulating cell adhesion and migration (Patino and Isom, 2010; Zhang, Fan et al., 2013). A schematic representation of the VGSC α and β subunits is shown in Figure 2. Several studies address VGSC structure and its interactions with pyrethroids, such as DLM (Catterall, 2000b; Catterall et al., 2007; Cestele and Catterall, 2000; King, 2011; King et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011; Zhang, F. et al., 2013).

Figure 2:

VGSC subunit structure. Both the α- and β-subunit representative images are displayed. The α-subunit is made up of 4 transmembrane domains (denoted by domain I-IV), each of which are made up of 6 transmembrane segments (S1-4 make up the voltage sensor; S5-6 form the pore) and a re-entrant loop (between S5 and 6) that is involved in ion selectivity. An intracellular loop connecting domains 3 and 4 functions as the inactivation gate that can plug the channel pore restricting ion flow. The β-subunit is a single transmembrane domain.

DLM binds to the α-subunit of VGSCs, changing the conformation. Pyrethroids have two proposed binding sites on VGSCs. They bind to an intramembrane site with a long, narrow hydrophobic pocket between domain 2 (transmembrane segments (S)4-S5) and domain 1 (S5/domain 3 S6 helices) (site 1), as well as a sequential region between domain 1 (S4) and domain 2 (S6) (site 2) on the α-subunit (Davies et al., 2007; Du et al., 2013; Silver et al., 2014; Wang and Wang, 2003). These sites are symmetrical but differ functionally. Mutations to the second site have less of an effect on receptor function than mutations to the first binding site (Du et al., 2013). The location of pyrethroid interaction with the VGSC was revealed using site-directed mutagenesis, oocyte expression studies (Du et al., 2009; Silver et al., 2014), and corroborated using computational modeling (Du et al., 2013).

When bound to VGSC, pyrethroids affect channel activation, slowing channel opening and closing (Narahashi, 1996; Soderlund, D. M., 2012). This causes VGSCs to shift the membrane to a more depolarized state making it easier to trigger action potentials (Narahashi, 1996). Pyrethroids hold the channels open longer, allowing more sodium to enter. Type II pyrethroids delay channel inactivation longer than Type I pyrethroids. Because of this, Type II pyrethroids at sufficient doses prolong channel opening and result in depolarization block where no action potentials occur (Shafer et al., 2005). Soderlund (2012) has reviewed pyrethroids actions on VGSC, including isoform and species differences.

VGSC subunits have temporal and regional expression patterns during development, which could have implications on pyrethroid exposure. Embryonic VGSC subunits are replaced with adult α- and β-subunits as development proceeds. Details were reviewed by Shafer et al (2005) for pyrethroids, but in brief the α-subunits Nav 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and 1.6 and β-subunits (Navβ1-4) are expressed throughout the CNS. In rodents, expression of Nav1.3 is high during embryogenesis and is gradually replaced by Nav1.2 (Albrieux et al., 2004; Felts et al., 1997). Nav1.2 is expressed in immature nodes of Ranvier of retinal ganglia (postnatal day (P)9-10) and are replaced by Nav1.6 as myelination occurs (~P14) (Boiko et al., 2001). The early expression of Navβ3 is replaced by Navβ1 and Navβ2 after P3 in rats. Navβ1 and Navβ2 increase until they reach adult levels (Shah et al., 2001). These developmental patterns may make VGSCs vulnerable to pyrethroids at different ages. Perturbations to these VGSC developmental shifts may make it more likely that they will result in later functional changes. Genetic or pharmacological exposures can alter VGSC development (Adams et al., 1990; Claes et al., 2001; Escayg et al., 2001; Meisler et al., 2001; Noebels, 2002; Shafer et al., 2005; Wallace et al., 2001). VGSC null mutations produce alterations or loss of channel subunits as do those caused by drugs that inhibit VGSCs during channel transitions to adult subtypes (Hatta et al., 1999; Kearney et al., 2001; Meisler et al., 2001; Ohmori et al., 1999; Planells-Cases et al., 2000; Schilling et al., 1999; Shafer et al., 2005; Vorhees et al., 1995). Disruptions to channel composition and function may contribute to the long-term effects from developmental pyrethroid exposure. For example, mice exposed to DLM during gestation and lactation had decreased VGSC mRNA expression as adults, (Magby and Richardson, 2017). It is not yet clear how changes in VGSC composition from developmental pyrethroid exposure results in long-term effects as no direct connection has been made. Nevertheless, this is an idea worth further investigation, due to the understood direct effect pyrethroids have on the VGSC.

ii. Calcium channels

Pyrethroids also affect calcium channels. Voltage gated calcium channels (VGCCs) belong to the same protein superfamily as VGSCs. VGCC are also signal transducers and control calcium influx (King et al., 2008). There are two types and they differ in voltage dependence: low-voltage VGCCs that are activated by small depolarizations but rapidly inactivated; and high-voltage VGCCs that are activated by large depolarizations but are slowly inactivated (King et al., 2008). VGSCs and VGCCs have similar structures, with analogous α subunits (α1 for the VGCCs), however they differ in their regulatory subunits that control the voltage-gated pore, and four repeat domains with six transmembrane segments (S1-S6) containing a loop between S5 and S6 (King et al., 2008) (Catterall et al., 2005). VGCCs differ from VGSCs in regulatory subunits. The high-voltage VGCCs have 4-5 subunits consisting of one pore-forming α1 subunit, an extracellular α2 subunit, a transmembrane δ subunit, an intracellular β subunit, and sometimes a transmembrane γ subunit (Catterall, 2000b; King et al., 2008). The low-voltage VGCCs have the α1 subunit without additional subunits (Catterall et al., 2005; King et al., 2008; Perez-Reyes, 2003).

Despite the overlapping structural similarities between VGSC and VGCCs, pyrethroids have different effects on these channels (Shafer et al., 2005; Soderlund, D. M., 2012; Soderlund et al., 2002). The effects of pyrethroids on VGCCs was reviewed by Soderlund (2012). Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is a potent VGSC inhibitor and attenuates pyrethroid actions. However, TTX only partially abolishes the effects of pyrethroids on VGSCs, indicating that pyrethroids act through other mechanisms (Shafer et al., 2005; Soderlund, D. M., 2012; Soderlund et al., 2002; Symington et al., 2008; Symington et al., 2007). In synaptosomes, Symington et al. (2007b) showed that a combination of TTX and DLM enhanced calcium uptake and release and was blocked by the N-type calcium channel blocker ω-conotoxin MVIIC. Cao et al. (2011), found no effects of pyrethroids on VGCCs in the presence of TTX in cultured mouse cortical neurons. Moreover, the effects of pyrethroids on VGSCs may have implications for NMDA receptor (NMDA-R) function, since pyrethroids and sodium/calcium exchangers modulate NMDA-R mediated depolarization (Cao et al., 2011; Soderlund, D. M., 2012). In addition, pyrethroids may act through VGCCs and that DLM can modify calcium currents under particular conditions (Shafer and Meyer, 2004; Soderlund, D.M., 2012; Soderlund et al., 2002). VGCCs also change during development, with expression increasing with age (McEnery et al., 1998). Therefore, VGCCs may be affected by developmental pyrethroid exposure. Since VGCCs are important in neurotransmitter release, pyrethroids may affect release thereby changing the level of signaling and ultimately behavior. It is possible that doses of DLM that are sufficient to affect VGCCs may induce permanent changes in channel regulation and affect behavior (Soderlund et al., 2002).

iii. Chloride channels

Soderlund et al. (2002) suggested that the CS syndrome could be a product of pyrethroids acting on voltage-gated chloride channels (VGCLCs) (Soderlund et al., 2002). However, only some pyrethroids inhibit VGCLCs only at high doses of Type I pyrethroids and by a few Type II pyrethroids, including DLM, but not by esfenvalerate or λ-cyhalothrin (Burr and Ray, 2004). Therefore, even among Type II pyrethroids there are important differences in how they affect VGCLCs. For Type II pyrethroids that do not affect VGCLCs, they should not contribute to the CS syndrome, and it appears that DLM is an exception because it elicits a CS syndrome and does affect VGCLCs. The effect of pyrethroids on VGCLCs was reviewed in detail by Soderlund (2012). However, the role of developmental DLM exposure on VGCLCs remains an open question.

iv. Chloride-related channels

The γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor-chloride ionophore is also affected by Type II pyrethroids. Soderlund and Bloomquist (1989) reviewed symptom onset in invertebrate models following pyrethroid exposure, as well as the binding of pyrethroids to sites on the GABA receptor-chloride ionophore. Overall binding of pyrethroids correlated with toxicity (Lawrence and Casida, 1983), without affecting GABA or benzodiazepines binding to the GABA chloride ionophore (Crofton et al., 1987; Lummis et al., 1987), suggesting a different binding site. Morever, the effects of DLM on ligand binding differs in different species. The mammalian GABA receptor-chloride ionophore is affected by pyethroids (Harris and Allan, 1985) but not the homologous receptor in flies (Cohen and Casida, 1986). Moreover, DLM is 1000-fold less potent at inhibiting GABA-dependent chloride uptake than it is at inhibiting VGSCs (Ghiasuddin and Soderlund, 1985), making this observation unlikely to be physiologically relevant.

Pyrethroids also inhibit peripherial-type benzodiazepine receptors (Soderlund and Bloomquist, 1989), a binding site on mitochondria (Papadopoulos, 2004). Pyrethroid interactions with the peripherial benzodiaepine receptors correlate with their proconvulsant effects at doses below those inducing other types of toxicity (Devaud and Murray, 1988; Devaud et al., 1986). The effects of DLM on these receptors during early development remains to be investigated.

In sum, pyrethroids bind to multiple ion channels. They primarily bind to VGSCs, but they have affinity for VGCC, VGCLC, and GABA-ion receptors at increasing doses. The collective effect of pyrethroids on these channels in adult rat and mouse brain are documented (see Shafer et al. (2005) and Soderlund (2012) for details); their effects during development are not yet known. At present there is no clear connection between pyrethroid binding to ion channels and long-term effects on behavior.

4. Neurotransmitters

I. Neurotransmitters: Fast acting

Since it is well understood that pyrethroids act on channels such as VGSC and VGCCs, this effect could lead to alterations in neurotransmission which ultimately can lead to various downstream effects. GABA and glutamate, the main inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters, respectively, are affected by DLM exposure. GABA and glutamate release following pyrethroid exposure in hippocampus of adult male rats was investigated using microdialysis. DLM (10, 20, or 60 mg/kg; i.p.) caused dose-dependent increases in glutamate release and decreases in GABA release (Hossain et al., 2008). The Type II pyrethroid cyhalothrin (10, 20, or 60 mg/kg; i.p.), on the other hand, inhibits glutamate release, while the Type I pyrethroid allethrin at 10 or 20 mg/kg i.p. increased release with opposite effects at higher doses (60 mg/kg) (Hossain et al., 2008). GABA levels are decreased after 10 or 20 mg/kg of allethrin, but increased after 60 mg/kg or after 10, 20, or 60 mg/kg of cyhalothrin (Hossain et al., 2008) showing that GABA and glutamate are differentially affected by different pyrethroids at different doses. Changes in GABA and glutamate from DLM, cyhalothrin, or allethrin are blocked by TTX (1 μM) at moderate doses. However, at high doses (60 mg/kg), such changes are blocked by infusion of the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nimodipine (10 μM) (Hossain et al., 2008), suggesting that DLM acts on VGCCs and VGSCs at high doses, but only on VGSCs at lower doses. Developmental DLM effects on GABA have not been studied (possible long-term DLM effects after developmental exposure on glutamate are discussed below).

II. Neurotransmitters: Cholinergic

Cholinergic neurotransmission was altered following exposure to pyrethroid pesticides. This neurotransmitter class has been examined extensively following pesticide exposure, in part due to many pesticides, such as organophosphates, altering cholinergic neurotransmission. Eriksson and Nordberg (1990) assessed the density of muscarinic and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors with labeled [3H]quinuclidinyl benzilate ([3H]QNB) and [3H]nicotine following DLM exposure in mice. High and low-affinity muscarinic binding was assessed by [3H]QNB/carbachol displacement. Mice exposed to 0.71 mg/kg/day DLM from P10-16 by gavage had increased muscarinic receptor density, increased high-affinity binding sites, and decreased percentage of low-affinity muscarinic receptor binding, as well as increased density of nicotinic receptors in the cerebral cortex 24 h after the last dose, with no effect in the hippocampus (Eriksson and Nordberg, 1990). Additionally, 1.2 mg/kg DLM (P10-16 by gavage), a dose that caused the CS syndrome in mice at these ages, resulted in decreased [3H]QNB binding in the hippocampus and increased [3H]nicotine binding in the cerebral cortex (high vs. low-affinity binding was not distinguished) (Eriksson and Nordberg, 1990). Eriksson and Nordberg (1990) also assessed the effects of developmental bioallethrin exposure (0.72 mg/kg by gavage [bioallethrin is composed of 2 of the 8 stereoisomers of allethrin]), a Type I pyrethroid, on nicotinic and muscarinic receptor binding. Bioallethrin reduced high-affinity and increased low-affinity muscarinic receptor binding. Bioallethrin had no effect on muscarinic or nicotinic binding in the hippocampus or cortex (Eriksson and Nordberg, 1990). Hence, different pyrethroids elicit different effects on cholinergic systems depending on brain region.

III. Neurotransmitters: catecholaminergic

There is mounting evidence implicating catecholamines in the effects of pyrethroids. Embryonic exposure (E6-15) to DLM (0.08 mg/kg by gavage) resulted in increased striatal 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) levels in adult male rats, with no change in dopamine (DA) or homovanillic acid (HVA) levels (Lazarini et al., 2001) and an increased DOPAC/DA ratio. No change in DA or its metabolites were observed in the female offspring as adults. However, Lazarini et al. (2001) used a unspecified commercial formulation of DLM and without control for litter effects. Richardson et al. (2015) exposed mice perinatally to DLM (E0-P22; 3 mg/kg DLM/72 h by gavage) and found that DLM increased DA transporter (DAT) levels in the striatum in both sexes, however the magnitude of the effect was larger in males. Using autoradiography, they found increased DAT levels in the nucleus accumbens but not in neostriatum of males (females were not evaluated using autoradiography). The dopaminergic neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) was used to estimate the in vivo consequences of increased DAT levels. MPTP (1 mg/kg, i.p.) induced DA reductions in control mice and larger reductions in DLM-treated mice (Richardson et al., 2015). In addition, DLM exposure decreased extracellular DA release measured by microdialysis, but there was increased DA D1 receptor (DRD1) levels in the n. accumbens in the males, with no change in neostriatum in either sex (Richardson et al., 2015). The functional consequences of increased DRD1 levels were assessed using the DRD1 antagonist SCH23390 (0.025, 0.05, or 0.1 mg/kg), the DRD2 antagonist eticlopride (0.05, 0.1, or 0.2 mg/kg), the DRD2 autoreceptor antagonist quinpirole (0.03 or 0.06 mg/kg quinpirole), the general DA receptor agonist, apomorphine (0.5 mg/kg), the selective DRD1 agonist SKF82958 (1.0 mg/kg), or the indirect DA agonist methylphenidate (1.0 mg/kg). Hyperactivity in DLM-treated male mice was normalized by SCH23390, eticlopride, quinpirole, and methylphenidate (Richardson et al., 2015). Whereas, when DA was first depleted by 5 mg/kg reserpine pretreatment, apomorphine increased locomotor activity in DLM-treated male mice, but not in female mice, compared with controls (Richardson et al., 2015). SKF82958 increased locomotor activity in control and DLM-treated mice, however the increase in DLM-treated mice was greater than in controls (Richardson et al., 2015). Overall, DA alterations from developmental DLM were long-lasting and may partially explain the long-term hyperactivity.

IV. Neurotransmitters: Serotonergic

Data on the effects of pyrethroids on serotonin (5-HT) are limited. Serotonin was measured with microdialysis in the striatum of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats after exposure to DLM, cyhalothrin (Type II pyrethroid), or allethrin (Type I pyrethroid) (10, 20 or 60 mg/kg; i.p.) (Hossain, 2013). DLM dose-dependently decreased basal 5-HT release, whereas it was increased with cyhalothrin (Hossain, 2013). Allethrin had dose-dependent effects, with decreased release of 5-HT after 10 mg/kg but increased release after 20 or 60 mg/kg (Hossain, 2013). These changes on 5-HT release were partially dependent on VGSCs since TTX prevented the effects of allethrin, cyhalothrin, and DLM at some doses (10 and 20 mg/kg) (Hossain, 2013). The 5-HT release effect of DLM at 60 mg/kg was blocked when combined with exposure to TTX and nimodipine (an L-type calcium channel antagonist) (Hossain, 2013). Like the effects observed on GABA and glutamate release, 5-HT release following DLM exposure at higher doses depended on VGCCs and VGSCs, with lower doses being dependent only on VGSCs. The effects on 5-HT release after developmental DLM exposure have not been tested.

The acute effects of DLM on 5-HT and its major metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) were evaluated in adult male Wistar rats in another study. DLM (20 mg/kg/day, i.p., for 6 days) reduced 5-HT and 5-HIAA in midbrain and striatum, and 5-HIAA in the frontal cortex and hippocampus (Martinez-Larranaga et al., 2003). Reductions in 5-HT and 5-HIAA were also found after exposure to cyfluthrin (14 mg/kg i.p. for 6 days) or λ-cyhalothrin (8 mg/kg i.p. for 6 days). 5-HT was reduced in all regions examined (frontal cortex, hippocampus, midbrain, and striatum) for these Type II pyrethroids (Martinez-Larranaga et al., 2003). 5-HIAA was also reduced following cyfluthrin (frontal cortex and striatum but not hippocampus or midbrain) and λ-cyhalothrin (frontal cortex, midbrain, and striatum but not hippocampus) (Martinez-Larranaga et al., 2003). These data indicate that 5-HT is affected by Type II pyrethroids but whether this also occurs after developmental exposure is unknown.

The above data implicate neurotransmitters in the effects of pyrethroids, including DLM. The effects on DA markers are the most consistent. It is not clear, however, if this is because DA is the most affected neurotransmitter or because it is the most investigated. Little is known about effects of developmental DLM on neurotransmitters other than DA, therefore, there are major gaps that need to be filled. In addition to neurotransmitters, DLM activates microglia via VGSCs in primary microglia culture (Hossain et al., 2016), indicating that more than ion channels and neurotransmitters are involved.

5. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism

To emphasize the importance of further study of developmental pyrethroid exposure, differences in exposure and elimination of these compounds must be considered. Children are estimated to be exposed to pyrethroids at levels of 3.0 μg/kg/day and adults to 0.6 μg/kg/day (EPA, 2015; Mortuza et al., 2018). Agricultural workers and those in urban areas tend to have higher exposures than those in suburban areas. Poisonous exposures that can occur from accidents or improper handling are too sporadic to be of much help in understanding the neurotoxicity of these compounds (Chen et al., 1991; He et al., 1989; Vinayagam, 2017).

In addition, to neurotoxicity outcomes, additional data are also needed on exposure. Data on absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), along with pharmacokinetics (PK) are relevant (Anadon et al., 1996; Anand, S.S., Bruckner, J. V., Haines, W. T., Muralidhara, S., Fisher, J. W., Padilla, S., 2006), including physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) studies. Understanding how DLM and other pyrethroids are processed in the body can aid in understanding the neurotoxic effects and the differences between adult and developing systems.

I. Physiologically based pharmacokinetics

PBPK studies provide data on age and species differences in dosimetry (Felter et al., 2015). DLM in rats (26 mg/kg by gavage or 1.2 mg/kg I.V. given once) is rapidly absorbed (Anadon et al., 1996) because it is lipophilic. This also means DLM easily enters the CNS and PNS (Anadon et al., 1996). DLM is absorbed in fat in the gut and liver (He et al., 1991; Rehman et al., 2014). Male rats given DLM by gavage (0.4, 2, or 10 mg/kg dissolved in glycerol formal) had rapid but incomplete gastrointestinal absorption, with some entering brain and accumulation in fat, skin, and skeletal muscle (Kim et al., 2008). The BBB restricts passage through the microvasculature (Amaraneni et al., 2017b), however, this is age-dependent. When 1, 10, or 50 μM 14C-DLM are perfused in anesthetized rats, uptake is inversely related to age, such that P15 rats display 2.2-3.7 fold higher uptake of DLM in brain than adults, with P21 rats intermediate (Amaraneni et al., 2017b). This is consistent with the observation that immature rats are more susceptible to the acute toxicity of DLM than adult rats (Cantalamessa, 1993; Sheets et al., 1994). DLM (10 mg/kg) in rats by gavage in glycerol formal at P10, 21, 40, or 90 is lethal at P10 and P21, but not at P40 or P90 Anand, S.S., Kim, K. B., Padilla, S., Muralidhara, S., Kim, H. J., Fisher, J. W., Bruckner, J. V. (2006). The differences in lethality and uptake in relation to age may be due to differences in metabolic enzymes and pharmacodynamics in these two age groups.

DLM in rats is cleared by plasma carboxylesterases (CaEs) and liver cytochrome P450s (CYP450) (Anand et al., 2006). Young and adult rats metabolize DLM efficiently at low doses, e.g., at 2 μM in diluted plasma and in liver microsomes (Anand et al., 2006). In P15, P21, and P90 rats, clearance of 0.1, 0.25, or 0.5 mg/kg DLM by gavage in corn oil, is cleared from plasma within 24 h. Differences in maximum concentrations (Cmax) and 24 h area under the curve (AUC24) are also age-dependent (Anand et al., 2006). Time to eliminate DLM is proportional to dose until enzyme saturation occurs, and this too is age-dependent (Mortuza et al., 2018). At P15, brain, plasma, and liver differences in dosimetry decreased proportionately with dose for Cmax from the highest and middle doses to the lowest dose (Mortuza et al., 2018), but this did not occur at P21 or adult ages. Differences in permeability, CYP450s and CaE activity in younger rats appear to account for this effect.

PBPK models provide data on elimination half-life, Cmax, clearance, and volume of distribution that predict plasma and tissue concentration-time profiles (Jones and Rowland-Yeo, 2013). Mirfazaelian et al. (2006) used a PBPK model for adult male Sprague-Dawley rats using flow-limited and diffusion-limited rate equations. Flow-limited equations account for gastrointestinal, hepatic, brain, and other rapidly perfused tissues, whereas diffusion-limited equations account for slowly perfused tissues, such as blood/plasma and fat. In this way, Mirfazaelian et al. (2006) estimated that 48 h after DLM (2 or 10 mg/kg by gavage) most of the compound is cleared via hepatic biotransformation, with a smaller percentage cleared by plasma CaE catabolism. Concentrations of DLM given by gavage (2 or 10 mg/kg) or by i.v. (1 mg/kg) were determined for blood, plasma, brain, and fat. Adult male rats had much lower DLM levels in brain than young rats (Mirfazaelian et al., 2006), suggesting that immature organisms are more susceptible to the deleterious effects of DLM. Using the same oral route as Mirfazaelian et al. (2006), a subsequent study by Godin and colleagues (2010) extrapolated the data to humans and found threefold greater 48 h AUCs and twofold greater peak DLM concentration will occur in human brain compared to rats at a dose of 1 mg/kg DLM given orally (Godin et al., 2010). Hence, greater brain concentrations are predicted in humans than in rats at equivalent doses.

The Mirfazaelian PBPK model was updated (Tornero-Velez et al., 2010) relative to other models (Amaraneni et al., 2017b; Anand, S.S., Bruckner, J. V., Haines, W. T., Muralidhara, S., Fisher, J. W., Padilla, S., 2006; Scollon et al., 2009). The newer model showed that when P10, 21, 40, and 90 rats were administered DLM at 0.4, 2, or 10 mg/kg DLM by gavage in glycerol formal, younger DLM-treated rats had higher brain concentrations compared with adults and more signs of toxicity (Kim, 2010; Tornero-Velez et al., 2010). Moreover, plasma DLM levels did not reflect brain levels (Kim, 2010). Brain concentrations (brain AUC24) of DLM for P10 rats were 3.8-fold higher than for P90 rats (Tornero-Velez et al., 2010), indicating increased susceptibility of the brain during this early developmental period.

A recent study examined DLM levels in plasma and brain of P15 (0, 1, 2 or 4 mg/kg DLM by gavage) and adult (0, 2, 8, or 25 mg/kg DLM, by gavage) rats 2-8 h following DLM administration (Williams et al., 2019). Regardless of age, dose-dependent increases in DLM were observed in brain and plasma at each dose, however at the 2 mg/kg dose, brain levels were higher at P15 compared with adults. In addition, DLM levels of P15 rats were highest 6 h following 4 mg/kg DLM (~151 ng/g) and remained high for 8 h, whereas adults that were administered a dose > 6 times higher (25 mg/kg DLM) had peak concentrations (~156 ng/g) 2 h after administration that fell by 50% within 4 h. Hence, not only are peak concentrations higher in younger rats they remain higher for longer than in adults. When examining signs of neurotoxicity, adult rats given the 25 mg/kg DLM dose had tremor and salivation for 4 h, whereas P15 rats had tremors after 2 and 4 mg/kg DLM that persisted for 8 h post-treatment. Some mortality was seen in the P15 rats, but not in the adults at these doses (Williams et al., 2019). These enhanced signs of neurotoxicity seen in developing rats follow the age-related concentrations in DLM.

A PBPK model was also used for in vitro to in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) for age-related differences after DLM (Song et al., 2019). Liver microsomes, cytosol, and plasma from immature and adult rats were scaled to model the in vivo time course of plasma and brain concentrations following oral doses of 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 5 mg/kg of DLM (Song et al., 2019). Age-dependent tissue levels were simulated for humans (i.e., brain Cmax) and showed that compartment partitioning and permeability were critical. The model recapitulated developmental changes in clearance as well as BBB maturity effects. The IVIVE-based PBPK model demonstrated an inverse relationship between age and brain DLM uptake, as also found in in situ models (Amaraneni et al., 2017b). The Song et al. (2019) model showed how brain concentrations were affected by body weight, cardiac output, blood volume, hematocrit, blood flow, absorption, metabolism, and age.

II. Metabolism

CaEs, CYP450s, and glutathione-S-transferase (GST) all contribute to DLM metabolism (Lu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2017). The principal route of DLM metabolism are ester cleavage and oxidation at the 4’ position (Anand, S.S., Bruckner, J. V., Haines, W. T., Muralidhara, S., Fisher, J. W., Padilla, S., 2006; Soderlund and Casida, 1977). Pyrethroids containing the cyano group are less sensitive to oxidation and hydrolysis than non-cyano pyrethroids (Soderlund and Casida, 1977). As noted, studies show trans isomers are readily hydrolyzed by esterases compared with cis isomers (Soderlund and Casida, 1977). DLM is only in the cis isoform (Elliott et al., 1974) and therefore is metabolized more slowly, hence DLM has a longer half-life compared with Type I pyrethroids (Anadon et al., 1996).

CaEs are widely distributed (He et al., 1991; Rehman et al., 2014) and hydrolyze DLM to produce alcohol and acid metabolites (Satoh and Hosokawa, 2006). Hydrolysis creates carboxylic acid ester, amide, and thiol-ester groups (Lu et al., 2019; Rehman et al., 2014; Soderlund and Casida, 1977) that are conjugated and excreted in urine. DLM is also a CaE inhibitor, hence it slows its own hydrolysis (Imai and Ohura, 2010; Lei et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Yoon et al., 2004).

CYP450 enzymes also contribute to DLM metabolism (Lu et al., 2019). CYP450s catalyze aromatic hydroxylation of DLM that is then conjugated for excretion (Lu et al., 2019; Rehman et al., 2014; Soderlund and Casida, 1977). CYP450s exhibit regional differences in brain as well, a little appreciated factor (Yadav, Sanjay et al., 2006). Rat hippocampus have higher levels of Cyp1a1 mRNA expression (Yadav, S. et al., 2006). Also, hippocampus and hypothalamus have higher levels of Cyp2b1 expression than other regions (Yadav, Sanjay et al., 2006). The medulla-pons, cerebellum, and frontal cortex have higher Cyp1a2 and Cyp2b2 mRNA expression than in other regions (Yadav, Sanjay et al., 2006). Both the hippocampus and hypothalamus have longer elimination half-lives of DLM and its metabolite, 4’-OH-DLM, than other regions (Anadon et al., 1996). The higher Cyp1a1 and Cyp2b1 expression in hippocampus and hypothalamus may contribute to the metabolites 2’, 4’ or 5’-OH-DLM found in these regions (Anadon et al., 1996; Yadav, Sanjay et al., 2006). The metabolic capacity of CaEs for DLM is lower than for CYP450s in liver and plasma (Anand et al., 2006), but a key question is how regional brain differences in CYP450 enzymes contribute to how DLM metabolism affects these regions, and as of now there are no data on this subject.

GST in another metabolic enzyme that contributes in the elimination of pyrethroids (Hemingway and Ranson, 2000) by conjugating electrophilic compounds with the thiol group of reduced glutathione allowing for the reduction of antioxidants (Berdikova Bohne et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2017). The nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-pathway is also involved; DLM is metabolized in rat liver microsomes via a NADPH-dependent mechanism and in human liver microsomes via a NADPH-independent processes (Godin et al., 2006). The implications of this difference have received little attention.

DLM appears to be metabolized by similar enzymes in humans and rats (Rehman et al., 2014), but there are quantitative differences in the rate of metabolism across species and over the course of development. Humans have low serum CaE levels, whereas rodents have high levels (Crow et al., 2007; Li et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2018). The lower levels in humans result in slower DLM clearance. In addition, the expression of CaE in humans is age dependent, with adults expressing higher levels than children or fetuses (Satoh and Hosokawa, 2006). Microsomes are 4 times more active in adults than in children and 10 times more active than in fetuses (Satoh and Hosokawa, 2006). These differences result in an increased exposure to pyrethroids during development.

For DLM, the parent compound is thought to be the major neurotoxin (Rickard and Brodie, 1985). There are multiple metabolites that can be formed from DLM (Cole et al., 1982). The main metabolites are 2’,4’, and 5’-OH-DLM (Lu et al., 2019; Romero et al., 2012). In SH-SY5Y cells, 2’-OH DLM (0-1000 μM) and 4’-OH-DLM (0-1000 μM) were more toxic than DLM (10-1000 μM) (Lu et al., 2019; Romero et al., 2012), which appears contradictory to the parent compound being the proximate neurotoxin. However, the metabolite comparisons are from cell culture and may not apply in vivo. If metabolites contribute to DLM neurotoxicity, it might help explain differences in DLM toxicity as a function of metabolite levels (Lu et al., 2019). For example, other metabolites of DLM include trans-methyl and ester cleavage groups that form 3-PBA and 4’ and 2’-OH-PBA (Lu et al., 2019). These metabolites are toxic at high doses, but not at concentrations seen in vivo (Henault-Ethier, 2016). Therefore, the relevance of these observations is unclear and in addition, these data are in adults, and similar data in developing animals are not available.

III. Cytotoxicity

Mechanisms of DLM neurotoxicity have primarily been studied in adult rodents or cell culture, with emphasis on apoptosis and oxidative stress. DLM increases apoptosis in cell culture (Enan, E. et al., 1996; Hossain, 2011; Wu et al., 2003) and in vivo (El-Gohary et al., 1999; Hossain, 2019; Wu and Liu, 2000a). Since apoptosis is normal during brain development the question becomes whether DLM induces excess cell death sufficient to explain or contribute to its long-term neurotoxicity.

Oxidative stress is also proposed as a mechanism of DLM-induced neurotoxicity. Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant enzymes that leads to lipid peroxidation in cells, mitochondria, and nuclear membranes and results in protein degradation or DNA damage (Kumar et al., 2015). DLM-treated male mice (5.6 and 18 mg/kg) exhibit lipid peroxidation and decreased antioxidant enzyme activity in liver and kidney (Rehman et al., 2006). Even relatively low doses of DLM (1.28 mg/kg and 3 mg/kg) increase lipid peroxidation, induce thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (marker of lipid peroxidation), and decrease levels of GST and antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase) in plasma and lymphoid organs in adult rats (Aydin, 2011; Yousef et al., 2006). PC12 cells exposed to DLM (10 μM/L) exhibit increased nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) expression and activity (Li et al., 2007). Nrf2 regulates antioxidant protein levels. These data suggest that DLM-induced oxidative stress is likely to be a contributing factor to DLM-induced neurotoxicity, however how this differs during developmental DLM exposure has yet to be explored.

DLM-induced calcium changes may also play a role in long-term neurotoxicity. Calcium acts as an intracellular signal controlling many functions including neurotransmission (Shafer and Meyer, 2004; Shafer et al., 2005). Transient or oscillating increases in calcium influx will alter cellular activity; sustained calcium elevation leads to apoptosis (Kumar et al., 2015). DLM (5-60 μM), increases phospholipase C (PLC) in glioblastoma cells and increases calcium mobilization that results in reduced rates of calcium/calmodulin dependent protein dephosphorylation in thymocytes (50 μM in vitro; 25 mg/kg in vivo), predisposing the cells to apoptosis (Enan, Essam et al., 1996). PLC generates inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG), both of which increase intracellular calcium and calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase and increase second messengers that promote DNA fragmentation and cell death. Although the effects of PLC and its downstream signaling effects have not been tested in a developmental DLM model to date.

Another mechanism by which DLM may induce calcium-dependent apoptosis is through activation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway. The ER is a reservoir for calcium, however, excess release within the lumen of the ER can trigger death cascades (Verkhratsky, 2005). DLM activates the ER stress pathway in cell culture (Hossain and Richardson, 2011) and in vivo in mice (Hossain et al., 2015). SK-N-AS cells treated with DLM have increased levels of the transcription factors C/EBP homologous protein/growth arrest and DNA damage 153 (CHOP/GADD153) (Hossain and Richardson, 2011), both of which are ER stress pathway pro-apoptotic factors (Hu et al., 2018; Oslowski and Urano, 2011). CHOP/GADD153 levels are also increased in mice treated with DLM (3 mg/kg every 3 days for 60 days), as are levels of binding immunoglobulin protein/78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (BiP/GRP78) (Hossain et al., 2015). BiP/GRP78 is an ER chaperone that regulates ER stress signaling via protein kinase R (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK), that at normal levels restores ER stress pathway balance following stress (Wang et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2005). However, when ER stress is prolonged, BiP/GRP78 activates PERK which phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 1 (eIF2α), that in turn inhibits the actions of eIF2α by blocking mRNA translation and protein synthesis, thereby exacerbating ER stress mechanisms (Wang et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2005). Thus, BiP/GRP78 is a regulator that reduces ER stress, except when ER stress is high enough to cause BiP/GRP78 to dissociate from the ER stress pathway allowing activation of cell death cascades (Oslowski and Urano, 2011). In addition, when eIF2α has sustained phosphorylation it can lead to CHOP activation through the suppression of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), an anti-apoptotic protein (Kim, 2008; Xu et al., 2005). Hence, eIF2α is a key regulator of the ER stress response. Increased activation of ER stress activates caspases and DNA fragmentation in cell culture assays (Hossain and Richardson, 2011) and in vivo (Hossain, 2019; Hossain et al., 2015) of DLM exposure; and these effects are blocked by the calcium chelator BAPTA-AM (5 μM), by blocking VGSCs with TTX (1 μM), or by salubrinal an eIF2α inhibitor (Hossain, 2019; Hossain and Richardson, 2011).

Another mechanism of DLM-induced neurotoxicity is through the tumor suppressor protein p53, which is also involved in apoptosis (Hughes et al., 1996; Xiang et al., 1998). DLM increases p53 and Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax; which is regulated by p53) in rat brain (Wu and Liu, 2000a) and in cortical neurons (Wu et al., 2003). These data, along with those above, point to apoptosis as a mechanism of DLM-induced neurotoxicity. However, an understanding of many of these pathways following developmental DLM exposure have yet to be fully explored.

In summary, PBPK models provide information on the ADME of DLM and how these differ as a function of age, especially in relation to brain and cytotoxicity data, suggesting mechanisms of neurotoxicity. Younger animals are more vulnerable to the effects of pyrethroids compared with adults because DLM levels are higher in plasma and brain at younger ages. The limited metabolic capabilities and immature BBB are factors for why CNS levels are higher in young animals, as are limited metabolic capacity at early ages. The vulnerability of younger animals to the effects of pyrethroids highlight the importance of studying the cytotoxicity of DLM during development to determine age-dependent mechanisms.

6. Effects of DLM on brain and behavior

I. Adult effects

The EPA estimates human exposures of pyrethroids at 3.0 μg/kg/day in children and 0.6 μg/kg/day in adults (EPA, 2015). 10 μg/kg/day is the reference dose for DLM for acute dietary exposure (Bennett et al., 2020). These are lower than used in animal studies that find behavioral and cognitive deficits, however, rats metabolize and clear DLM much faster than humans, therefore, administered dose comparisons are not meaningful. Brain concentrations would be ideal but cannot be obtained in people, therefore, direct dose comparisons are not possible.

Studies of pyrethroid behavioral toxicity to 2008 were reviewed previously (Wolansky and Harrill, 2008). The authors noted that adult rodent pyrethroid exposure results in many functional effects that include: altered locomotor activity at doses that do not produce overt neurotoxicity, impaired rotorod performance (DLM and α-cypermethrin), reduced schedule-controlled operant responding (allethrin, permethrin, cis-permethrin, DLM, cypermethrin, and fenvalerate), decreased grip strength (pyrethrum, bifenthrin, S-bioallethrin, permethrin, β-cyfluthrin, cypermethrin, and DLM), and altered startle reflexes, specifically, increased acoustic startle (Type I pyrethroids) or decreased acoustic startle amplitude (Type II pyrethroids) (Wolansky and Harrill, 2008) see also (De Souza Spinosa et al., 1999). Data on cognitive effects are more limited. Adult mice treated with 3 mg/kg DLM (every 3 days for 60 days with testing beginning 3 days following the last dose) had increased latency to find a submerged platform in a Morris water maze (MWM) (Hossain et al., 2015).

II. Developmental effects

Neurobehavioral toxicity data in developing animals is also limited and finding commonalities across studies is challenging because studies vary in design, dependent variables, exposure periods, doses, species, strain within species, routes of exposure, frequency of exposure, vehicles the compounds are dissolved in, sample sizes, and even how the data were analyzed. Here we review the relevant available data.

Locomotor activity is a behavioral measure extensively studied following developmental DLM exposure. NMRI mice were administered 0.7 mg/kg DLM by gavage (dissolved 20% fat emulsion of egg lectin, peanut oil, and water) from P10-16 and did not have changes in locomotor activity when assessed on P17, however when tested as adults (~4 months of age) the mice had increased activity compared with controls (Eriksson and Fredriksson, 1991). Mouse dams were administered 3 mg/kg/72 h DLM (dissolved in corn oil mixed with peanut butter and voluntarily ingested) from E0 to P22, and at 6-week old offspring had increased locomotor activity (Richardson et al., 2015). This effect occurred in males across three days but only at test intervals longer than 30 min with no differences during the first 30 min of testing and no differences in females (Richardson et al., 2015). The increased activity in male DLM-treated mice was normalized by treatment with methylphenidate (1 mg/kg) (Richardson et al., 2015), suggesting to the authors that the change in activity induced by DLM was ADHD-like, due to the use of methylphenidate as a treatment for ADHD as well as its influence of the biochemistry of the disorder. When mice were exposed perinatally to DLM and tested for locomotor activity between 6 to 12 weeks of age, activity decreased with age, but DLM-treated males were more active than control males (Richardson et al., 2015). However, when rats were exposed to DLM only during gestation, locomotor activity was decreased rather than increased in adulthood. Male rats exposed to DLM (0.08 mg/kg, gavage) from E6-15 were less active than vehicle controls at 60 days of age with no change in females (Lazarini et al., 2001). Johri et al. (2006) found reduced activity in male rat offspring exposed prenatally to DLM from E5-21 (oral doses of 0.25, 0.5, or 1.0 mg/kg DLM). The reduction in activity was dose-dependent at 3 weeks of age, but less pronounced when tested at 6 and 9 weeks of age (females were not tested). The effect of DLM on activity, therefore, appears to depend on exposure age, dose, and age at assessment. These rats studies used commercial DLM formulations that contain other ingredients. Additionally, Lazarini et al. (2001) do not report their vehicle formulation and Johri et al. (2006) did not report the use of the vehicle given to controls, adding some uncertainty to the interpretation of these data. There also are limited data on developmental exposure of rats to commercial fenvalerate (Moniz et al., 1999; Moniz et al., 2005).

Richardson et al. (2015), who observed hyperactivity in mice exposed to 3 mg/kg/72 h of DLM prenatally and postnatally, also tested impulsivity and attention using a fixed ratio (FR) wait operant paradigm. Mice received food reinforcement after 25 lever presses. If mice pressed during the wait interval, the wait time was reset, and they had to press the lever an additional 25 times for reinforcement. Male (but not female) DLM-treated mice had reduced wait times and increased FR resets compared with controls, suggesting impulsivity and alterations in attention from developmental DLM exposure.

As in adults, pyrethroids affect the startle response after developmental exposure. In adults, Type I pyrethroids increase and Type II pyrethroids decrease acoustic startle behavior (Crofton and Reiter, 1988; Williams et al., 2018, 2019). Consistent with this, acoustic startle was decreased in P15 rats given DLM (1, 2, or 4 mg/kg dissolved in corn oil and administered by gavage) for 8 h following dosing (Williams et al., 2019). By contrast, this effect lasted only 4 h in adult rats given even larger doses (Williams et al., 2019). The Type I pyrethroid permethrin (60, 90, or 120 mg/kg given by gavage dissolved in corn oil at a dosing volume of 5 mL/kg) induced increased acoustic startle in P15 rats with a delayed onset, becoming significant 6 h following 60 mg/kg permethrin (Williams et al., 2018). By contrast, at 120 mg/kg, startle was decreased 4, 6, and 8 h after dosing, and at 90 mg/kg there was no effect on startle (Williams et al., 2018). Hence, permethrin has a biphasic effect on acoustic startle in P15 rats perhaps through competing physiological processes resulting in facilitated startle at 60 mg/kg but suppression of the faciliatory effect at the higher dose of 90 mg/kg resulting in no effect, and a dominant suppressive effect at 120 mg/kg. In adult rats, the acoustic startle response is only increased by permethrin. Across studies, the effects of pyrethroids on acoustic startle clearly depend on the pyrethroid, age, dose, and time since dosing. Whether these effects on startle occur with other pyrethroids should be determined in future studies.

Developmental DLM exposure also has cognitive effects. In Richardson et al.’s (2015) study, male mice exposed to DLM (3 mg/kg/72 h from E0-P22), had deficits in working memory reflected by decreased spontaneous alternation in a Y-maze. In another study, shock motivated Y-maze visual discrimination learning in rats exposed to 1 mg/kg DLM from E14-20 was impaired in the offspring (Aziz et al., 2001). These rats were first habituated to a Y-maze for 2-3 min, then given 40 trials with foot-shock induced escape to an illuminated safe arm. The following day the safe arm was switched to a different arm in a reversal learning test. DLM-treated offspring at 6 and 12 weeks of age displayed decreased reversal learning but no differences on acquisition (Aziz et al., 2001). Hence, the above data provide some evidence that developmental DLM exposure causes multiple long-term neurobehavioral changes. Specific alterations that were reported following developmental DLM exposure, both behavioral and biochemical, are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Developmental DLM Findings

| Organism/ exposure age/ dose/vehicle |

Developmental DLM Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Mice (NMRI); P10-16; 0.71 or 1.2 mg/kg – gavage; 20% fat emulsion (egg lectin/ peanut oil/water) |

Receptor density: 0.71 mg/kg - ↑ mACh receptor density; ↑ high-affinity binding sites; ↓ percent low-affinity mACh-R binding; ↑ density nACH-R – in cortex 24h after dose, but not hippocampus 1.2 mg/kg - ↓ mACh-R binding in hippocampus; ↑ nACh-R binding in cerebral cortex |

Eriksson & Nordberg, 1990 |

| Mice (NMRI); P10-16; 0.7 mg/kg – gavage; 20% fat emulsion (egg lectin/ peanut oil/water) | Locomotor activity: No change at P17; ↑ activity at ~ 4 mo. of age) | Eriksson & Fredriksson, 1991 |

| Rat (Wistar); E14-20; 1 mg/kg – gavage; corn oil | Y-maze shock avoidance: ↓ reversal learning (6 & 12 weeks of age in offspring) | Aziz et al., 2001 |

| Rat (Wistar); E6-15; 0.08 mg/kg (commercial formulation) – gavage; vehicle formulation not disclosed |

Locomotor activity: Males less active than controls (P60), no change in females Monoamine: ↑ striatal DOPAC (adult males), no change in DA or HVA; ↑ DOPAC/DA ratio |

Lazarini et al., 2001 |

| Rat (Wistar); E5-21; 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 mg/kg (commercial formulation) – gavage; No vehicle control treatment | Locomotor activity: Dose-dependent ↓ at P21 (male); less effect at 6 & 9 weeks of age; females not tested | Johri et al., 2006 |

| Mice (C57BL/6J); E0-P22; 3 mg/kg/72h – oral; voluntary ingestion; corn oil mixed with peanut butter |

Locomotor activity: ↑ activity (P42 offspring), females (unaffected), males normalized by methylphenidate (1 mg/kg), SCH23390 (0.025, 0.05, 0.1 mg/kg), or eticlopride (0.05, 0.1, 0.2 mg/kg); ↑ activity with apormorphine (0.5 mg/kg; when DA is depleted first by reserpine) males but not females; SKF82958 (1.0 mg/kg) ↑ activity; FR wait operant: ↓ wait times; ↑ FR resets (males only) Y maze: ↓ spontaneous alternation DA: ↑ DAT (n. accumbens); MPTP (1 mg/kg) ↓ DA; ↓ extracellular DA release (microdialysis, n. accumbens); ↑ DRD1 (male n. accumbens) |

Richardson et al., 2015 |

| Rat (Sprague-Dawley); P15; 1, 2, 4 mg/kg – gavage; corn oil | Startle: ↓ (up to 8 h following dose) | Williams et al., 2019 |

Neurotoxicity for developmental DLM on behavior and neurotransmitters. Abbreviations: ↑, increase; ↓, decrease; ASR, acoustic startle response; DA, dopamine; DLM, deltamethrin; DRD1, dopamine receptor D1; DAT, dopamine transporter; DOPAC, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; E, embryonic day; FR, fixed ratio; HVA, homovanillic acid; MPTP, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; P, postnatal day.

III. A Different Developmental Model

We developed a neonatal exposure model with Sprague Dawley rats treated from P3-20 and examined the long-term effects of DLM at doses of 0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/kg dissolved in 5 mL/kg corn oil administered by gavage (Pitzer et al., 2019) to determine if other cognitive and behavioral effects are caused by developmental DLM.

Rats were used because of their greater cognitive ability relative to mice. DLM or corn oil (CO) treated rats were assessed for allocentric hippocampal dependent learning and memory, egocentric striatal dependent learning and memory, conditioned freezing, acoustic and tactile startle, locomotor activity with or without drug challenge, and anxiety-like behavior. Deficits in allocentric reversal learning and memory were observed in the Morris water maze (MWM) (Pitzer et al., 2019) but not during acquisition as Aziz et al. (2001) found in a Y-maze. Thus, DLM-treated rats learned the first phase of the MWM at the same rate as controls, but when the platform was moved to the opposite quadrant (reversal) or moved a second time to an adjacent quadrant (shift) DLM rats had less efficient paths to the goal and increased average heading errors (Pitzer et al., 2019). As the task became harder, only males had deficits, as seen in the shift phase. These findings implicate impairment of cognitive flexibility while sparing basic spatial navigation. By inference, the deficits after the platform was moved suggest impairments in remapping of distal cues (Vorhees and Williams, 2006). Shift trials are a unique procedure used in this lab. We have seen other examples where effects appear on one or two phases but not all three. The precise reason for such patterns is not known, but each phase places different cognitive demands on the spatial abilities of the rats and reveals effects that would not be observed had only acquisition been tested. The deficits on MWM shift trials may be another reflection of flexibility impairment like the reversal deficit, or it may reflect an increase in retroactive interference since during the shift phase, rats must extinguish two previously learned responses, rather than one as during reversal. However, this explanation cannot account for the sex difference that only appeared on the shift trials. Whatever neural circuits mediate shift learning must be impaired in males but spared in females. While the neurophysiological basis of the shift effect is not known, clearly the task demands on the shift phase are unique and unmask effects not otherwise in evidence. This cross-phase unmasking occurs despite that as rats move from one phase to the next their efficiency steadily improves even as the task becomes more difficult given the decreasing size of the goal. It appears that the requirement to extinguish previous responses and acquire new responses places increased demands on the hippocampal-entorhinal processes that DLM exposure compromised. The unmasking effect of shift testing dissociates the learning-to-learn aspects of increasing task proficiency across phases while revealing treatment effects not otherwise known.

Overall it is clear that the hippocampus is critical for spatial learning and flexibility for stimulus-guided behavior (Eichenbaum and Cohen, 2004), yet there are circuitry differences between brain regions that may account for differences between acquisition, reversal, and shift, and require further investigation. However, there may be species related differences as well, with the data in mice yielding a different result for DLM exposure. Hossain et al. (2015) found deficits in MWM acquisition in adult C57BL/6 mice treated with DLM (0 or 3 mg/kg by gavage dissolved in corn oil every 3 days for 60 days). It would be interesting to see what these mice would show during reversal learning. In addition, it is important to note Hossain et al. (2015) observed MWM acquisition deficits in mice exposed to DLM in adulthood. Thus age-dependent or species differences in the exposure models could account for these differences as well.

The hippocampus and its importance in spatial learning has been extensively studied, including how various disruptions to this region can alter different aspects of spatial learning such as cognitive flexibility. Hippocampus-dependent place learning, but not response learning, is required for spatial flexibility, as shown from data conducted in a water-cross maze (Kleinknecht et al., 2012). In the experiment, an intact hippocampus was necessary for learning spatial relationships because mice treated with ibotenic acid to lesion the hippocampus could not learn the water-cross maze (Kleinknecht et al., 2012). Moreover, fornix lesions in rats leads to impaired cognitive flexibility when distal cues or starting positions in a MWM are altered, even as acquisition is spared (Eichenbaum et al., 1990) similar to what we saw after developmental DLM. Morris et al. (1990) showed that hippocampal, subiculum, and combined hippocampal/subiculum lesions result in impaired place navigation in the MWM, but the lesioned groups gradually caught up to controls when given extra trials. Lesioned rats in that study also had impaired spatial matching to place, which involves changing the location of the escape platform daily. On this task, overtraining did not overcome deficits in spatial learning (Morris et al., 1990). Subiculum lesioned rats have milder deficits in a matching to place water maze, with larger deficits after hippocampus or hippocampus/subiculum lesions (Morris et al., 1990). Additionally, Morris et al. (1990) over-trained rats in the MWM, then lesioned them, and retested the rats later. Under these conditions overtraining did not result in catchup effects. The findings show the essential role of the hippocampus in place learning and cognitive flexibility. However, the more unusual finding of spared acquistion and impaired reversal and shift in the MWM, requires further study.

In addition to MWM reversal and shift deficits, the DLM-treated rats had alterations in conditioned freezing (Pitzer et al., 2019). Conditioned freezing assesses two mnemonic processes, one hippocampally dependent (contextual memory) and one amygdala-dependent (cued memory) (Curzon et al., 2009). We found that DLM-treated males had increased freezing during conditioned training and impaired 24 h contextual memory but spared amygdala-related cued memory (Pitzer et al., 2019). Contextual freezing and MWM spatial flexibility rely on the hippocampus and surrounding structures; hence, the two findings appear consistent.

Spatial learning and memory involve place cells in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Ainge et al., 2007). Rats with hippocampal damage induced by ibotenic acid infused into the dentate gyrus and CA regions and tested in a double-ended Y-maze for position discrimination and alternation, had increased errors when the side reinforced with food was reversed, but not during acquisition (Ainge et al., 2007). Ainge et al. (2007) also found that place fields in the hippocampus encoded both current and projected locations as the task was learned. However, the learned anticipatory information was disrupted when the platform was moved, implying that memory extinction of the previous platform position was impaired after developmental DLM.