Abstract

The dioxin receptor is a ligand-activated transcription factor belonging to an emerging class of basic helix-loop-helix/PAS proteins which show interaction with the molecular chaperone hsp90 in their latent states and require heterodimerization with a general cofactor, Arnt, to form active DNA binding complexes. Upon binding of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons typified by dioxin, the dioxin receptor translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to allow interaction with Arnt. Here we have bypassed the nuclear translocation step by creating a cell line which expresses a constitutively nuclear dioxin receptor, which we find remains in a latent form, demonstrating that ligand has functional roles beyond initiating nuclear import of the receptor. Treatment of the nuclear receptor with dioxin induces dimerization with Arnt to form an active transcription factor complex, while in stark contrast, treatment with the hsp90 ligand geldanamycin results in rapid degradation of the receptor. Inhibition of degradation by a proteasome inhibitor allowed geldanamycin to transform the nuclear dioxin receptor to a heterodimer with Arnt (DR-Arnt). Our results indicate that unchaperoned dioxin receptor is extremely labile and is consistent with a concerted nuclear mechanism for receptor activation whereby hsp90 is released from the ligand-bound dioxin receptor concomitant with Arnt dimerization. Strikingly, artificial transformation of the receptor by geldanamycin provided a DR-Arnt complex capable of binding DNA but incapable of stimulating transcription. Limited proteolysis of DR-Arnt heterodimers indicated different conformations for dioxin versus geldanamycin-transformed receptors. Our studies of intracellular dioxin receptor transformation indicate that ligand plays multiple mechanistic roles during receptor activation, being important for nuclear translocation, transformation to an Arnt heterodimer, and maintenance of a structural integrity key for transcriptional activation.

The dioxin receptor is a member of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)/PAS (Period [Per]-aryl hydrocarbon [Ah] receptor nuclear translocator [Arnt]-Single Minded [Sim]) family of transcriptional regulators, a growing subclass of bHLH proteins which harbor a 250- to 300-amino-acid PAS homology region contiguous to the bHLH motif. The PAS domain incorporates two degenerate hydrophobic repeats, termed PAS A and PAS B, and functions as a dimerization interface (21, 34, 69). Postulated roles of the PAS domain include facilitating partner selection during formation of bHLH-PAS heterodimers and conferring target gene specificity of bHLH-PAS heterodimers (49, 75). Many new members of this family have been recently discovered, including the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) (67) and the related HIF-like factor/endothelial PAS (HLF/EPAS1) (13, 65), Drosophila developmental factors such as Trachealess (23, 74) and SIM (60), the mammalian circadian rhythm proteins Clock (32) and PER (62, 64), and various transcription-mediating cofactors exemplified by SRC-1 (29), TIF-2 (66), and the nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR (9). While most of these factors have been demonstrated as critical for survival and/or homeostasis in mice or Drosophila, the molecular mechanisms through which they operate are ill defined. The dioxin receptor (DR; also known as the Ah receptor) and HIF-1α are stress-induced factors which respond to environmental toxins or low oxygen tension, respectively. Both factors form active heterodimers with a central bHLH/PAS partner protein, Arnt (18), which is also an essential heterodimeric cofactor for the function of Sim in Drosophila neurogenesis and Trachealess in Drosophila tubular airway formation (60). Gene targeting has shown lethal phenotypes due to defective vascularization in both HIF-1α (24) and Arnt (33, 37) null mice, illustrating the critical developmental role of the HIF-1α–Arnt heterodimer. Gene targeting of the DR has produced mice with liver development impaired to various degrees (14, 42, 56), with one report of immune system defects (14).

The DR and Arnt are two founding members of the bHLH/PAS family, and as such their dimerization to form an active transcription factor complex has become a paradigm in studying mechanisms of bHLH/PAS protein function. In the latent state the DR resides in the cytosol, bound with a complex of two molecules of the molecular chaperone hsp90 and a 38-kDa protein showing homology to the immunophilins FKBP12 and FKBP52 (5, 35, 41). We have previously mapped the major hsp90 binding region of the DR to encompass the PAS B repeat (70). Interestingly, this hsp90 binding region colocalizes with the ligand binding domain (70), consistent with the observation that hsp90 is essential to chaperone a conformation of the receptor which is competent to bind ligand (10). Association with hsp90 is also thought to function in cytosolic retention of the receptor by masking the N-terminal nuclear localization signal (NLS) (22). Activation of the DR occurs in response to binding dioxins or related polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and involves a multistep process of nuclear translocation, dissociation from the hsp90 complex, and dimerization with Arnt. Formation of the DR-Arnt heterodimer is obligatory for recognition of xenobiotic response element (XRE) enhancer sequences, which lie upstream of several target genes encoding xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes such as cytochrome P4501A1, glutathione S-transferase, and quinone oxidoreductase (for recent reviews, see references 47 and 55). The DR thus performs a critical cellular defense function by binding environmental toxins and consequently mediating induction of an enzyme battery to promote their metabolism and excretion.

Despite many investigations into the process by which the latent DR becomes transformed into an active heterodimer, this mechanism is still poorly understood. Classic models suggested that ligand binding of the receptor led to dissociation of hsp90 in the cytoplasm, allowing dimerization with Arnt, which subsequently translocated the receptor to the nucleus (18). However, immunohistochemistry has recently shown Arnt to be a nuclear protein (20, 48), and a nuclear localization signal has been mapped in the N terminus of Arnt (11), rendering this scenario unlikely. More recent dioxin receptor activation models posit that either the ligand-activated receptor moves to the nucleus free of hsp90, in a manner similar to that proposed for hormone activation and translocation of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (38), or hsp90 remains bound to the receptor throughout the nuclear translocation process. In vitro evidence suggests that Arnt plays a role in dissociating hsp90 from the ligand-bound DR, indicating that the transformation may occur in the nucleus (40). Further in vitro experiments suggest that ligand-independent transformation of the hsp90-bound DR to the heterodimeric form with Arnt is also possible (50), thereby complicating models seeking to elucidate the mechanistic role of ligand in the transformation process.

To investigate the mechanisms which regulate bHLH-PAS factor heterodimerization and explore the role of ligand in DR activation, we are studying the function of mutant and modified bHLH/PAS proteins. Here we have added a heterologous NLS at the C terminus of the DR and generated two stable cell lines which express a constitutively nuclear DR. This nuclear receptor remains in its latent form, requiring addition of exogenous ligand for activation. Analysis of DR signalling in these novel cell lines has provided insights into the multifunctional roles ligand plays during formation of the active DR-Arnt transcription factor complex. In addition to the well-documented initiation of nuclear translocation of the DR, ligand invokes Arnt heterodimerization and maintains a conformation of the DR-Arnt complex competent for initiating transcription. Our data has also produced intracellular evidence that hsp90 release from the DR occurs within the nucleus in a concerted mechanism with Arnt dimerization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of the DR-NLS expression vectors.

An oligonucleotide encoding the nucleoplasmin NLS (30) (boldface) and hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (underlined), KRPAATKKAGQAKKKKRYPYDVPDYA, was inserted in duplicate into an XhoI site generated at the 3′ end of the coding sequence for the murine DR. A hexahistidine tag was also incorporated at the extreme 3′ end of the coding sequence. The C-terminally modified DR was then subcloned into both the pCIN4 expression vector (54), generating plasmid pDR-NLS/CIN4, and the pEF/IRESpuro vector (17), generating plasmid pEF/DR-NLS/IRESpuro.

Cell culture and generation of stable cell lines expressing a constitutively nuclear DR.

Mouse adrenal Y1 cells, mouse hepatoma Hepa1c1c7 cells, and the human embryonic kidney transformed cell line 293T were routinely grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco/BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, streptomycin (100 U/ml), and gentamicin (100 U/ml). Y1 cells (2 × 106) were transfected with 10 μg of either pDR-NLS/CIN4 or pCIN4, using standard electroporation procedures (31). Cells were then seeded into 10-cm-diameter dishes and allowed to recover for 24 h before addition of G418 at an initial concentration of 250 μg/ml. After 2 to 3 weeks of selection, single G418-resistant colonies were expanded in medium containing 1.5 mg of G418 per ml. To generate the 293T/DR-NLS stable cell line, 293T cells were transfected with pEF/DR-NLS/IRESpuro vector via the DOTAP method (Boehringer) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following a 24-h transfection period, cells were seeded into two 10-cm-diameter dishes and allowed to recover for a further 24 h, after which time puromycin (1 μg/ml; Sigma) selection was applied for a 14-day period. Following initial selection, pools of cells were subjected to higher levels of puromycin selection to eventually reach 10 μg/ml.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were seeded onto coverslips and grown for 48 h before being fixed by two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and immersion in methanol for 2 min at room temperature. Cells were rehydrated in PBS for 15 min and then incubated with rat anti-HA monoclonal antibody (MAb) 3F10 (0.2 μg/ml; Boehringer) for 2 h at room temperature. The coverslips were washed three times with PBS and subsequently incubated with a 1/30 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rat MAb (Sigma) for 45 min at room temperature, followed by a wash in PBS before incubation with bisbenzimide stain (Hoechst 33258; 10 μg/ml; Sigma) for 1 min. Following another two washes in PBS, the coverslips were dried, mounted onto slides with glycerol, and sealed. Cells were viewed with a Zeiss microscope.

Transient transfections.

The XRE-thymidine kinase (TK)-luciferase reporter plasmid pXIXI and control TK-luciferase construct (T81) have been described previously (3). pRL-TK (Promega) encodes the luciferase gene from Renilla reniformis and was used as an internal control in transient transfection experiments. Hepa1c1c7, Y1/DR-NLS, and Y1/Neo-Ctrl stable cell lines were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells into wells of a 24-well tray and grown for 24 h. Duplicate wells were transfected with 200 ng of pXIXI firefly luciferase reporter and 50 ng of pRL-TK via the DOTAP transfection method (Boehringer); 12 h following transfection, cells were induced with tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD; 1 nM) or vehicle alone (0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) for 30 h unless otherwise stated. For geldanamycin (Gibco/BRL) and MG132 (Biomol) treatments, cells were incubated with combinations of geldanamycin (1 μg/ml), MG132 (7.5 μM), and TCDD (1 nM) for 16 h. These combinations of chemicals yielded no signs of toxicity to Y1 cells over this period. Cells were assayed for luciferase activity by using a DLR luciferase kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunoblotting.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared as previously described (70). Cytosolic and nuclear extracts for immunoblotting were prepared as follows. Cells were harvested with TNE (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA), washed with PBS, and pelleted. Cells were resuspended in 2.5 pellet volumes of hypotonic buffer plus Nonidet P-40–Ficoll lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.4% Nonidet P-40, 10% Ficoll-400, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 2 μg of apoprotinin per ml, 4 μg of bestatin per ml, 5 μg of leupeptin per ml, 1 μg of pepstatin per ml) and incubated on ice for 5 min. The cells were then centrifuged for 30 min at 14,000 rpm and 4°C. The supernatant was used as the cytosolic fraction. The pellet was resuspended in 1.5 pellet volumes of nuclear extract buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 0.42 M KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, protease inhibitors as specified above), incubated with shaking for 45 min on ice, and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm and 4°C to provide the supernatant nuclear fraction. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay; samples (100 μg) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 7.5% gel) and then transferred to nitrocellulose in a semidry blotter (Hoefer). Proteins were detected with the anti-HA MAb 12CA5 (Boehringer) or anti-DR MAb RPT1 and visualized with SuperSignal chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce).

Immunoprecipitations.

Y1/DR-NLS cells were treated with combinations of TCDD (1 nM), geldanamycin (1 μg/ml), and MG132 (7.5 μM) for 2 h. Nuclear extracts were prepared as described above, and immunoprecipitations using polyclonal antisera directed against the C terminus of Arnt were performed as previously described (59). Immunoprecipitates were boiled in SDS sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE on a 7.5% gel, and then transferred to nitrocellulose. The DR-NLS protein was detected by the anti-HA MAb 12CA5. Immunoprecipitations using the anti-HA MAb 3F10 (Boehringer) were performed as follows. Whole-cell extracts (1 mg) were incubated with 50 μl of a 1:1 slurry of protein G-agarose (Boehringer) for 1 h at 4°C and centrifuged for 1 min at 10,000 rpm. The supernatant was removed and diluted twofold with hypotonic buffer; MAb 3F10 (5 μg) was added and incubated for 3 h with shaking, after which time 100 μl of protein G-agarose was added and the solution was incubated overnight. The immunoprecipitated complexes were washed four times with buffer A (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 120 mM KCl, 2% milk powder, 1 mM PMSF).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

Protein extracts from Hepa1c1c7 and Y1/DR-NLS cells for use in gel shift assays were generated by swelling of pelleted cells in hypotonic buffer followed by one freeze-thaw cycle and centrifugation (30 min, 14,000 rpm, 4°C). The supernatant was kept as the cytosolic fraction, while the nuclear extract was obtained by shaking the pellet in 1 pellet volume of hypotonic buffer containing 0.42 M KCl for 30 min on ice. In vitro transformation reactions in the Hepa1c1c7 cytosolic extracts were performed at room temperature for 2 h with the indicated combinations of TCDD (10 nM), geldanamycin (10 μg/ml), or vehicle alone (0.2% DMSO). Conditions for DNA binding with the 32P-labeled XRE1 sequence from the rat cytochrome P4501A1 promoter and subsequent nondenaturing electrophoresis were as previously described (16).

Nickel affinity purification of DR-NLS.

Whole-cell extracts from 293T and 293TDR/NLS-puro cells were used for purification of the DR-NLS protein by using the hexahistidine tag. Protein (1.5 mg) from untreated whole-cell extracts or extracts from cells cotreated with MG132 alone or with geldanamycin (1 μg/ml for 30 min) were incubated with 5 mM imidazole binding buffer (500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.1% Triton X-100) and 400 μl of 1:1 Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin (Qiagen) for 1 h. The column was washed five times with 1-ml fractions of 5 mM binding buffer, followed by successive washes with 300 μl of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mM imidazole in binding buffer and elution with 300 μl of 150 mM imidazole in binding buffer; 500 μg of bovine serum albumin was added as a carrier protein, and the protein was precipitated with acetone overnight at 4°C. Following centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in SDS sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE as described above, and visualized with an anti-hsp90 MAb (H38220; Transduction Laboratories).

Partial trypsin digestion reactions.

For partial proteolysis of Y1/DR-NLS whole-cell extracts, 100 μg of extract was incubated with 150 ng of trypsin (Boehringer) at 37°C for 20 min. For proteolysis of immunoprecipitated complexes, Y1/DR-NLS cells were treated with the indicated ligand and MG132 as described above, and whole-cell extracts were taken and immunoprecipitated, also as described above except that no PMSF was present in the wash buffer. Immunoprecipitates were collected by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 5 min, resuspended in 30 μl of Tris (10 mM, pH 7.5) containing 25 ng of trypsin, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Inactivation of the trypsin was achieved by boiling in SDS sample buffer for 5 min, after which time the digests were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western analysis using MAb 12CA5.

RESULTS

Generation of a stable cell line expressing a constitutively nuclear DR.

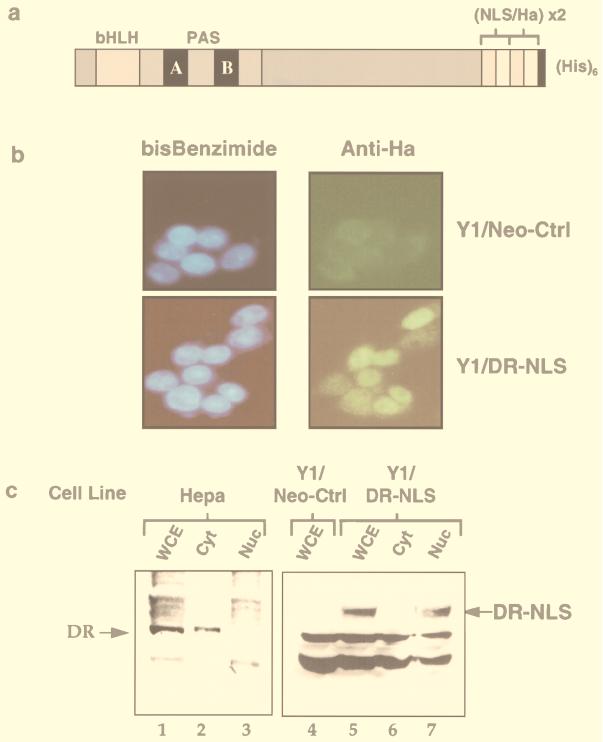

Of the bHLH/PAS factors thus far analyzed for location within the cell, Sim and Trachealess have been reported to be nuclear, while the latent DR and HIF-1α are cytoplasmic. Arnt is generally found in the nucleus but has also been reported as cytoplasmic in some cell types at distinct embryonic stages (1), while a Drosophila homologue, Tango, is mostly cytoplasmic (68). In the case of HIF-1α, a hypoxia-regulated NLS in the C terminus induces nuclear translocation at low oxygen levels (27). In contrast, constitutively nuclear Sim and Trachealess seemingly operate in the absence of any environmental signals. In vitro experiments have shown that Sim, Trachealess, and HIF-1α all form strong heterodimers with Arnt in the absence of exogenous inducers (12, 15, 19, 39, 60, 63). While interaction of the DR with Arnt is strictly ligand dependent in common cell lines, some in vitro studies have observed various degrees of ligand-independent dimerization upon mixing of protein fractions containing the DR and Arnt (38a, 44), suggesting that an extranuclear location of the DR may be important for maintenance of its latent form. One hypothesis regarding the role of ligand in DR activation posits that the sole purpose of ligand may be to invoke transport of the receptor into the nucleus, whereupon transformation of the receptor to an active heterodimer with Arnt could ensue irrespective of the presence of ligand. To investigate the possibility that ligand-independent activation of the DR can be achieved by artificially translocating it to the nucleus, we modified the receptor to include an NLS at its C terminus. The 3′ end of the mouse DR cDNA was extended to contain a duplicate of an oligonucleotide encoding the NLS from nucleoplasmin and the HA recognized by MAbs 12CA5 and 3F10. A hexahistidine tag was also incorporated at the very C terminus (Fig. 1a).

FIG. 1.

Generation of a stable cell line expressing a nuclear DR. (A) Schematic representation of the C-terminally modified DR containing duplicate sequences of the nucleoplasmin NLS and the HA epitope followed by a hexahistidine tag. (B) The Y1/DR-NLS stable cell line expresses a constitutively nuclear DR. Y1/Neo-Ctrl and Y1/DR-NLS cells were seeded onto coverslips and fixed with methanol. Cells were incubated with the rat MAb 3F10 directed against the HA epitope, followed by incubation with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibody. Nuclei were visualized by bisbenzimide (blue) staining. (C) Immunoblot analysis of the DR in cell extracts. Protein extracts (100 μg) from whole cells (WCE), cytosol (Cyt), and nuclei (Nuc) of nontreated Hepa1c1c7, Y1/Neo-Ctrl, and Y1/DR-NLS cells were separated by SDS-PAGE (7.5% gel), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with MAb RPT1 (specific for the native DR; lanes 1 to 3) or 12CA5 (specific for the HA tag; lanes 4 to 7). Positions of the native and NLS-HA-modified forms of the DR are indicated.

The mouse adrenal Y1 cell line lacks endogenous DR, as determined by immunoblotting and reverse transcription-PCR (data not shown), and was therefore chosen as a background-free model system in which to study the activity of the constitutively nuclear DR. Y1 cells were transfected with an expression vector encoding the NLS-modified DR and the neomycin resistance gene, which were linked by the encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosome entry site. Several clonal lines revealed stable expression of the NLS-HA-modified DR following G418 selection. These lines exhibited similar characteristics in terms of acquired dioxin signalling, and one, hereafter termed Y1/DR-NLS, was selected for further analysis. A G418-resistant control cell line which exhibited stable integration of the blank expression vector, hereafter called Y1/Neo-Ctrl, was also isolated. Immunofluorescence using a MAb directed against the HA epitope demonstrated that the modified DR was constitutively localized to the nucleus in Y1/DR-NLS cells (Fig. 1b). The slight cytosolic staining observed is nonspecific, as Y1/Neo-Ctrl cells exhibited a similar cytosolic staining pattern, while there was no nuclear staining in the Y1/Neo-Ctrl cells (Fig. 1b). In standard DR-expressing cell lines such as the mouse hepatoma Hepa1c1c7, immunohistochemistry has demonstrated the DR to translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus upon treatment with ligands (48). As expected for a cell line containing a constitutively nuclear receptor, the immunofluorescence pattern of the Y1/DR-NLS cells was not altered upon TCDD treatment (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis of whole-cell extracts from Y1/DR-NLS lines confirmed the presence of the modified DR, which was absent from the Y1/Neo-Ctrl cells (Fig. 1c; compare lanes 4 and 5). Consistent with the immunofluorescence observations, cell fractionation of untreated Y1/DR-NLS cells allowed recovery of our modified DR in the nuclear extract, whereas it was absent from the cytosolic extract (Fig. 1c; compare lanes 6 and 7). In total contrast, extracts from untreated Hepa1c1c7 cells showed the native DR to be recovered in the cytosolic but not the nuclear fraction (Fig. 1c; compare lanes 2 and 3). These experiments clearly demonstrate that we have derived a cell line which exhibits stable expression of a constitutively nuclear DR. Western analysis using DR-specific antibodies revealed that the level of the modified receptor in Y1/DR-NLS cells is lower than that of the wild-type receptor in Hepa1c1c7 cells, thus obviating any potential aberrant signalling due to overexpression (data not shown). A second stable cell line, derived from human embryonic kidney 293T cells, was also generated and was termed 293T/DR-NLS. As the Y1/DR-NLS cell line is free of endogenous DR, it provides a unique model system to investigate the role of ligand in the DR activation process. While the following experiments report the full characterization of the Y1/DR-NLS line, similar results have been obtained for the independent 293T/DR-NLS line.

A constitutively nuclear DR is not constitutively active.

The DR is a ubiquitous protein which resides in untreated cells as a latent complex with the molecular chaperone hsp90 and a 38-kDa immunophilin-like protein (5, 35, 41). In close analogy to the GR, the hsp90 complex is thought to have critical roles in maintaining cytoplasmic retention of the DR as well as chaperoning its ligand binding conformation (for reviews, see references 47 and 55). In well-established model systems such as Hepa1c1c7 cells, ligand treatment initiates nuclear translocation of the DR (48), although the mechanics of this process are not well understood. It has been generally proposed that ligand treatment invokes dissociation of hsp90 to allow free receptor to pass into the nucleus. Other bHLH/PAS proteins shown to interact with hsp90 are HIF-1α (15, 19) and Sim (39), although the relevance of hsp90 association with these factors, and any influence of this interaction on their cellular location, is unclear at this time.

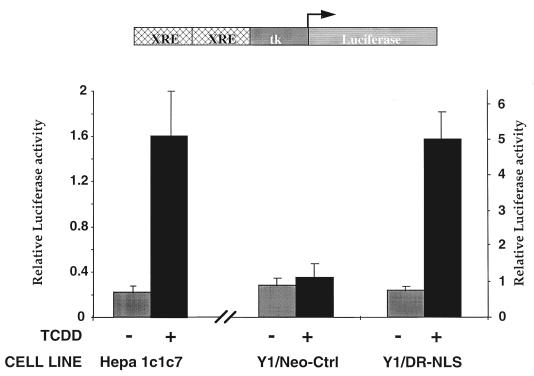

To test whether our constitutively nuclear DR behaves like other nuclear bHLH/PAS proteins and undergoes nonstimulated transformation into an active transcription factor, we assessed reporter gene activity in the Y1/DR-NLS cell line. Transfection of an XRE-driven luciferase reporter gene into Y1/Neo-Ctrl cells gave a low level of background activity which remained unaltered by dioxin treatment (Fig. 2), consistent with Y1 cells being deficient for the DR. Transfection of the XRE reporter gene into untreated Y1/DR-NLS cells gave a level of background activity similar to that for the Y1/Neo-Ctrl cells, indicating that there is little or no active DR-NLS–Arnt complex in nonstimulated cells. Strikingly, ligand treatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells resulted in an approximately 6- to 8-fold increase in XRE reporter gene activity (Fig. 2). A similar ligand induction of reporter gene activity was observed in 293T/DR-NLS cells (data not shown). Ligand activation of the DR-NLS is consistent with what is observed when Hepa1c1c7 cells are transfected with the reporter gene and treated with ligand (Fig. 2). Our results demonstrate that the constitutively nucleus-localized DR remains in a latent form and importantly, as ligand is necessary to activate the constitutively nuclear DR, indicate that the role of ligand in DR activation is more complex than merely initiating the nuclear translocation of a cytosolic receptor.

FIG. 2.

The nuclear DR requires ligand to activate transcription in Y1/DR-NLS cells. Hepa1c1c7, Y1/Neo-Ctrl, and Y1/DR-NLS cells were transiently transfected with an XRE-luciferase reporter gene and the renilla luciferase internal control vector pRL-TK. Cells were treated with dioxin (TCDD, 1 nM; dark bars) or vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO; light bars) for 24 h (Hepa1c1c7) or 30 h (Y1/Neo-Ctrl and Y1/DR-NLS). Luciferase activity was normalized against the internal control and is an average ± standard error of six transfection experiments. The left hand y axis pertains to the Hepa1c1c7 transfections, while the right-hand y axis relates to transfections in the modified Y1 cell lines.

Ligand treatment is needed for the nuclear DR to interact with Arnt.

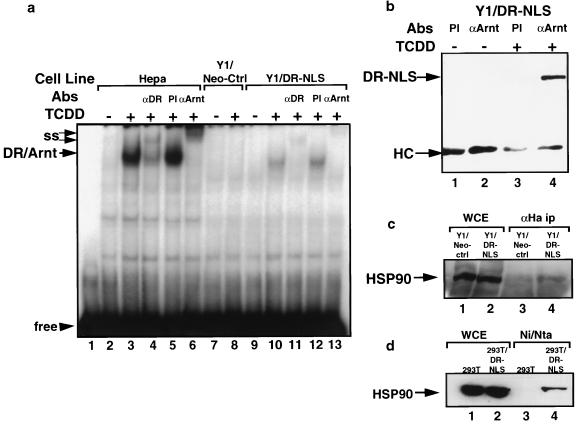

While the native DR is cytoplasmic in untreated cells, immunofluorescence has revealed Arnt to be an exclusively nuclear protein in cultured cell lines (20, 48). As our constitutively nuclear DR was dependent on ligand to become transcriptionally active, we wished to assess whether this nuclear DR was in fact in a heterodimeric form, with Arnt, which lacked transcriptional activity due to the absence of ligand or whether it remained in a latent complex typical of the cytosolic receptor. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were used to determine if the untreated nuclear DR was capable of binding the XRE target DNA sequence. As expected, nuclear extracts from untreated Hepa1c1c7 cells or control Y1 cells did not harbor DNA binding DR-Arnt complexes (Fig. 3a, lanes 2 and 7). Nuclear extracts from ligand-treated Hepa1c1c7 cells showed the established XRE mobility shift which is diagnostic for the DR-Arnt complex (Fig. 3a, lane 3) (47). This XRE-bound complex could be supershifted and partially depleted with antibodies specific for both the DR and Arnt but was unaffected by preimmune serum (Fig. 3a; compare lane 3 with lanes 4 to 6). No TCDD-inducible band was generated from nuclear extracts of ligand-treated Y1/Neo-Ctrl cells, again demonstrating a lack of endogenous DR in the parent cell line (Fig. 3a, lane 8). Nuclear extracts from untreated Y1/DR-NLS cells lacked the characteristic DR-Arnt band in this assay, which appeared in extracts from ligand-treated cells (Fig. 3a; compare lanes 9 and 10). As for the wild-type DR, antibodies specific for both the DR and Arnt could supershift and partially deplete this TCDD-inducible complex, while preimmune serum had no effect (Fig. 3a; compare lane 10 with lanes 11 to 13). These experiments reveal that the DR-NLS protein is not present in a DNA binding form in untreated Y1/DR-NLS cells, indicating that it is unlikely to be in a constitutive heterodimeric complex with Arnt. Lower intensities of the XRE gel shift bands from Y1/DR-NLS extracts reflect the relatively low expression of DR-NLS compared to the wild-type receptor in Hepa1c1c7 cells.

FIG. 3.

The nuclear DR requires ligand to heterodimerize with Arnt and bind DNA. (a) The DR-NLS protein from Y1 cells is in a non-DNA binding form in the absence of ligand. Nuclear extracts (15 μg) from Hepa1c1c7 cells (lanes 2 to 6), Y1/Neo-Ctrl cells (lanes 7 and 8), or Y1/DR-NLS cells (lanes 9 to 13) treated with 1 nM TCDD or vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) for 4 h were incubated with a 32P-labeled XRE probe and separated by nondenaturing PAGE (5.5% gel). Positions of the DR-Arnt band and free XRE probe are indicated. ss, supershifted bands generated by incubation with antibodies (Abs) directed against either the DR (αDR) or Arnt (αARNT). PI, preimmune serum. (b) The nuclear DR requires ligand to heterodimerize with Arnt. Y1/DR-NLS cells were treated with 1 nM TCDD or vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) for 2 h. Nuclear extracts (100 μg) were immunoprecipitated with antiserum raised against Arnt (αArnt) or preimmune serum (PI), separated by SDS-PAGE (7.5% gel), and immunoblotted with anti-HA MAb 12CA5. Positions of the DR-NLS protein and immunoglobulin heavy chain (HC) are indicated. (c and d) The nuclear DR remains bound to hsp90. (c) Whole-cell extracts (WCE) from Y1/Neo-Ctrl or Y1/DR-NLS cells were immunoprecipitated (ip) with rat anti-HA MAb 3F10, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with an antibody specific for hsp90. (d) Whole-cell extracts from 293T or 293T/DR-NLS cells were purified by nickel affinity chromatography and separated by SDS-PAGE before being immunoblotted with an hsp90-specific MAb. The position of hsp90 is indicated with an arrow.

To assess directly whether the nuclear DR interacts with Arnt independently of ligand, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments with antibodies raised against the C terminus of Arnt. Proteins immunoprecipitated from nuclear extracts of Y1/DR-NLS cells were subjected to Western blot analysis by probing with MAb 12CA5, directed against the HA epitope. Anti-Arnt immune serum failed to coprecipitate the DR-NLS from untreated Y1/DR-NLS cells (Fig. 3b, lane 2). However, the immunoprecipitation protocol showed a clear interaction between Arnt and DR-NLS in nuclear extracts from ligand-treated cells (Fig. 3b, lane 4), establishing that generation of the heterodimeric complex between the nuclear DR and Arnt is ligand dependent. Control precipitations with preimmune sera failed to show any background in this assay (Fig. 3b, lanes 1 and 3), confirming the specificity of the anti-Arnt immune serum. To determine if hsp90 was bound to the latent nuclear DR, immunoprecipitation assays using an anti-HA MAb were performed with cell extracts from untreated Y1/Neo-Ctrl and Y1/DR-NLS cells. Western blot analysis using an antibody directed against hsp90 revealed no hsp90 in immunoprecipitates from the Y1/Neo-Ctrl cell line, whereas hsp90 was coimmunoprecipitated with the HA-tagged DR from extracts of Y1/DR-NLS cells (Fig. 3c; compare lanes 3 and 4). As expected, hsp90 levels were identical in the two cell lines (Fig. 3c; compare lanes 1 and 2). In a second analysis, purification of the hexahistidine-tagged DR-NLS from 293T/DR-NLS cells by nickel affinity chromatography showed that hsp90 copurified with the DR-NLS (Fig. 3d, lane 4). An identical purification procedure using protein from control 293T cells established that there was no background hsp90 adsorbed to the nickel affinity resin during this assay (Fig. 3d, lane 3). Our data from these two coprecipitation methods using extracts from two independent cell lines firmly establish that the latent DR-NLS protein is bound to hsp90. Taken together, the results in Fig. 3 show that the constitutively nuclear DR is bound to hsp90 and undergoes a ligand-induced transformation process which is indistinguishable from that which occurs for the latent cytosolic receptor, indicating that nuclear compartmentalization per se does not invoke any part of this transformation.

A ligand for hsp90 can stimulate the nuclear DR to form a heterodimer with Arnt.

The antitumor agent geldanamycin has recently been shown to act as a ligand for hsp90 (61), complexing at the ATP binding site within the N terminus (52). Binding of geldanamycin has been shown to prevent or disrupt interaction of hsp90 with a number of its substrates, including steroid hormone receptors (58), the tyrosine kinase v-Src (73), and c-Raf-1 (57). As a means to further explore the role of ligand in DR activation, we were interested to see whether geldanamycin treatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells could affect transformation of the nuclear DR to the heterodimeric complex with Arnt. Previously it was reported that geldanamycin treatment of Hepa1c1c7 cells produced a loss of the DR, supposedly because a conformational change within the DR-hsp90 complex increased susceptibility of the receptor to degradation (8). We investigated the stability of the nuclear DR upon exposure to geldanamycin by performing Western blot analyses. Following a 2-h geldanamycin treatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells, Western blots of whole-cell extracts revealed that the receptor had almost completely disappeared (Fig. 4a; compare lanes 1 and 2). As we have previously observed that turnover of the native DR can be inhibited by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (54a), we cotreated Y1/DR-NLS cells with geldanamycin and MG132 for 2 h before subjecting whole-cell extracts to Western analysis. The proteasome inhibitor completely inhibited the loss of the DR-NLS protein during geldanamycin treatment (Fig. 4a, lane 3). Intriguingly, when the Y1/DR-NLS cells were cotreated with MG132 and geldanamycin, immunoprecipitation assays with anti-Arnt antibodies demonstrated a clear heterodimerization of the DR-NLS protein with Arnt (Fig. 4b, lane 1). Cotreatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells with dioxin, geldanamycin and MG132 provided levels of DR-NLS–Arnt heterodimer that were similar to levels seen in cells treated with geldanamycin and MG132 or cells treated with dioxin and MG132, indicating that geldanamycin-induced transformation of the DR was similar in efficiency to that of dioxin-induced transformation (Fig. 4b; compare lanes 1, 2, and 9). Treatment of cells with MG132 alone produced negligible amounts of coprecipitated DR-NLS, establishing that MG132 does not intrinsically stimulate receptor transformation (Fig. 4b, lane 7). The ability to generate a heterodimer was dependent on MG132 treatment, as geldanamycin treatment alone produced a minimal interaction between DR-NLS and Arnt (Fig. 4b, lane 3), which is consistent with the DR-NLS protein being degraded upon exposure to geldanamycin. These results imply that geldanamycin has the ability to disrupt DR-hsp90 complexes, resulting in dramatically increased lability of the DR. To investigate if hsp90 is released from the DR upon geldanamycin exposure, we repeated the successful nickel affinity purification of the DR-NLS–hsp90 complex from 293T/DR-NLS cells as shown in Fig. 3d. Following cotreatment of 293T/DR-NLS cells with MG132 and geldanamycin or with DMSO vehicle alone for 30 min, whole-cell extracts were Ni-NTA purified and separated by SDS-PAGE. Combined geldanamycin and MG132 treatments led to a decrease in the level of hsp90 which copurified with the DR-NLS protein (Fig. 4c; compare lanes 3 and 4). Importantly, this treatment had no effect on the amount of DR-NLS protein purified (Fig. 4c; compare lanes 5 and 6), ruling out the possibility that the lower level of hsp90 copurification was a result of lower receptor levels. Furthermore, geldanamycin had no detrimental effect on hsp90 levels present in the cells (Fig. 4c; compare lanes 1 and 2).

FIG. 4.

The hsp90 binding agent geldanamycin (GA) can induce formation of DR-Arnt heterodimers. (a) GA treatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells stimulates DR degradation which can be inhibited by the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Whole-cell extracts from Y1/DR-NLS cells treated with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO; lane 1), GA (1 μg/ml; lane 2), or GA (1 μg/ml) plus MG132 (7.5 μM) (lane 3) for 2 h were analyzed for the presence of the DR-NLS protein by immunoblotting with anti-HA MAb 12CA5. The position of the DR-NLS protein is indicated, the two lower bands representing background proteins detected by 12CA5. (b) GA can induce a DR-Arnt heterodimer in the Y1/DR-NLS cell line. Y1/DR-NLS cells were treated with the indicated combinations of GA (1 μg/ml), TCDD (1 nM), and MG132 (7.5 μM) for 2 h. Nuclear extracts of treated cells were immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal antibody (Ab) raised against Arnt (A) or preimmune serum (PI), separated by SDS-PAGE (7.5% gel), and immunoblotted with the anti-HA MAb 12CA5. Locations of the DR-NLS protein and immunoglobulin heavy chain (HC) are indicated. (c) GA destabilizes DR-NLS–hsp90 complexes. Whole-cell extracts from 293T/DR-NLS cells treated for 30 min with DMSO (0.1%) or GA (1 μg/ml) in the presence of MG132 (7.5 μM) were purified by using Ni-NTA resin prior to immunoblotting with an hsp90 MAb. Ten percent of the eluted protein was run on a separate gel and immunoblotted with the anti-DR MAb RPT1 (lanes 5 and 6). Lanes 1 and 2 contain aliquots of the extracts prior to purification. The positions of hsp90 and DR-NLS are indicated.

The geldanamycin-induced DR-Arnt heterodimer is not transcriptionally active.

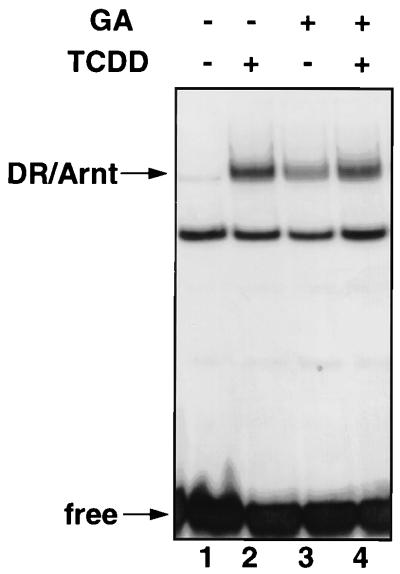

To ascertain that the geldanamycin-induced DR-Arnt heterodimer seen in MG132-treated Y1/DR-NLS cells is not an isolated phenomenon, we investigated the ability of geldanamycin to transform the native DR in vitro. Hypotonic cytosolic extracts of Hepa1c1c7 cells typically contain both the latent DR and Arnt, the presence of the latter being due to leakage from the nucleus during the hypotonic fractionation procedure. Dioxin treatment of Hepa1c1c7 cytosol is a well-established method to transform the receptor into a heterodimeric complex with Arnt (47), as detected by electrophoretic mobility shift assay with an XRE probe (Fig. 5; compare lanes 1 and 2). Treatment of Hepa1c1c7 cytosolic extracts with geldanamycin resulted in transformation of the DR with an efficiency only slightly lower than that seen with dioxin (Fig. 5; compare lanes 2 and 3). Cotreatment with dioxin and geldanamycin gave a level of transformation similar to that of dioxin alone (Fig. 5; lane 4). Importantly, the results in Fig. 5 show that an artificial transformation of the DR, using a ligand which binds hsp90 rather than the receptor, can produce a heterodimer with Arnt which maintains its ability to bind the XRE cognate DNA sequence.

FIG. 5.

Geldanamycin-induced DR-Arnt heterodimers are capable of binding DNA. Cytosolic extracts (15 μg) from Hepa1c1c7 cells were treated with DMSO vehicle (lane 1), TCDD (10 nM, lane 2), geldanamycin (GA; 10 μg/ml; lane 3), or a combination of TCDD (10 nM) and GA (10 μg/ml) (lane 4) for 2 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with a 32P-labeled XRE probe prior to separation by nondenaturing PAGE (5.5% gel). Positions of the DR-Arnt band and free probe are indicated.

As the geldanamycin-induced DR-Arnt heterodimer maintains its DNA binding ability, we sought to ascertain whether this complex was functional as a transcription activator. Y1/DR-NLS cells were transfected with the XRE-luciferase reporter gene and treated with geldanamycin in the presence or absence of MG132. Geldanamycin alone failed to activate the reporter gene (Fig. 6), as was expected considering the rapid proteolysis of the receptor observed upon geldanamycin treatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells. Upon cotreatment with geldanamycin and MG132, conditions which result in DR-NLS stabilization and DR-NLS–Arnt heterodimer formation, the reporter gene remains totally inactive. Surprisingly, the artificially induced heterodimer does not function as a transcription factor. In total contrast, cotreatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells with dioxin and MG132 provided an increase in reporter gene activity 5- to 6-fold over that seen with dioxin treatment alone and 20- to 30-fold over activity in nontreated cells (Fig. 6). These experiments establish that MG132 treatment does not interfere with the transcription activating potency of the DR-NLS–Arnt heterodimer but in fact enhances it, presumably due to increased receptor stability. The inability of the Y1/DR-NLS cells cotreated with geldanamycin and MG132 to show reporter gene activity therefore cannot be due to a nonspecific detrimental effect of MG132. Cotreatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells with TCDD and geldanamycin gave a marginally lower response than treatment with TCDD alone, while cotreatment with TCDD, geldanamycin, and MG132 provided reporter gene activity midway between that found for TCDD-treated and TCDD-MG132-cotreated cells (Fig. 6). These last results are consistent with geldanamycin competing with TCDD for transformation of the nuclear DR, in which case a mixture of active and inactive DR-NLS–Arnt heterodimers would be formed.

FIG. 6.

The DR-Arnt complex induced by geldanamycin does not activate transcription. Y1/DR-NLS cells were cotransfected with the XRE-luciferase reporter gene and the renilla luciferase internal control vector pRL-TK. Cells were then treated with the indicated combinations of DMSO vehicle alone, TCDD (1 nM; dark bars), geldanamycin (GA; 1 μg/ml; light bars), and MG132 (7.5 μM) for 16 h. Luciferase activity was normalized against the internal control and is an average ± standard error of four transfection experiments.

Intriguingly, artificial activation of the latent DR-NLS to the DR-NLS–Arnt heterodimer results in a nonfunctional transcription factor complex. These results imply that for the ligand-bound DR, the ligand may play a structural role in creating a receptor competent for communication with the basal transcription machinery or transcription-mediating cofactors. Treatment with geldanamycin allows an unnatural release of the DR from the molecular chaperone hsp90 (Fig. 4c), which presumably results in an aberration of receptor structure and renders it unable to activate transcription. Consistent with this model, studies of DR activity in yeast have shown that in strains where hsp90 levels can be reduced to approximately 5% of endogenous levels, the receptor signalling pathway ceases to function (6, 72).

DR-Arnt heterodimers induced by dioxin differ structurally from heterodimers induced by geldanamycin.

Following the observation that DR-NLS–Arnt heterodimers induced by geldanamycin are transcriptionally inactive, we next investigated whether this might be due to conformational differences between the two heterodimeric forms. To gain evidence for differences in conformation between dioxin- and geldanamycin-transformed receptors, we performed limited proteolytic digestion assays. Following treatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells with either TCDD or geldanamycin for a 2-h period in the presence of MG132, cell extracts were obtained and subjected to short incubations with trypsin. Western blotting with anti-HA MAb 12CA5 revealed proteolytic fragments in the digests from geldanamycin-treated cells which were not observed in digested extracts from TCDD-treated cells (Fig. 7a; compare lanes 3 and 4). No corresponding fragments could be detected in digested extracts from the Y1/Neo-Ctrl cell line treated with either TCDD or geldanamycin (Fig. 7a, lanes 1 and 2), indicating that these fragments are derived from the DR-NLS protein. To confirm that unique bands could be produced by proteolysis when the DR was complexed with Arnt, Y1/DR-NLS cells were treated with either geldanamycin or TCDD in the presence of MG132, and protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Arnt antibodies before being subjected to trypsin digestion and Western analysis. As observed for partially digested whole-cell extracts, geldanamycin-specific DR-NLS proteolytic fragments were observed upon digestion of the Arnt coimmunoprecipitates (Fig. 7b). An estimation of the fragment sizes generated from whole-cell extracts and immunoprecipitated complexes suggests that the geldanamycin-transformed DR is being primarily cleaved in a region approximately 40 to 60 kDa from the carboxy terminus, which would locate the cleavage region within the ligand binding domain. This observation is consistent with the notion that a destructuring of the ligand binding domain occurs upon geldanamycin-induced release of hsp90.

FIG. 7.

The DR-Arnt complex induced by geldanamycin differs in conformation from heterodimers induced by dioxin. (A) Whole-cell extracts (100 μg) from Y1/Neo-Ctrl or Y1/DR-NLS cells treated for 2 h with TCDD (1 nM) or geldanamycin (GA; 1 μg/ml) in the presence of 7.5 μM MG132 were incubated with 150 ng of trypsin (20 min, 37°C), separated by SDS-PAGE (10% gel), and immunoblotted with anti-HA MAb 12CA5. (B) Whole-cell extracts from Y1/DR-NLS cells treated as for panel A were immunoprecipitated (ip) with anti-Arnt antibodies and digested with 25 ng of trypsin (15 min, 25°C) while bound to protein A-Sepharose. Proteolytic fragments were separated by SDS-PAGE (12.5% gel) and detected by immunoblotting with anti-HA MAb 12CA5. Geldanamycin-specific bands are indicated with small arrows.

DISCUSSION

Signal-regulated bHLH/PAS proteins.

Members of the bHLH/PAS transcription factor family have been broadly classified into two categories (12, 19, 39). Group I factors, which include the DR, HIF-1α, HLF/EPAS1, Sim, and Trachealess, have the general properties of interacting with hsp90 and being able to heterodimerize with Arnt but lack the ability to homodimerize. In contrast, the group 2 factors Arnt, Arnt2, and Per all show promiscuous heterodimerizing as well as homodimerizing activities but do not interact with hsp90. It is evident that some of the bHLH/PAS proteins respond to specific signalling pathways, and it has been postulated that the PAS domain is a general sensing domain for oxygen, redox, or light reception in a diverse array of organisms including mammals, insects, plants, fungi, and bacteria (76). Within the mammalian bHLH/PAS factors, the DR and HIF-1α have been demonstrated to respond to specific but quite distinct intracellular stress signals. For the DR, the well-established binding of xenobiotics functions to initiate a multistep activation pathway, while low oxygen tension induces a rapid increase in protein levels of HIF-1α. In addition, several analyses of HIF-1α chimeric proteins indicate that important but unknown signalling pathways operate to increase the intrinsic activity of HIF-1α in low-oxygen environments (26, 28, 53). As both HIF-1a and the DR bind hsp90 prior to forming active heterodimeric complexes with Arnt, we are currently exploring whether close mechanistic similarities exist between the activation pathways for these signal-regulated bHLH/PAS factors. The PAS domain is inhibitory for nuclear translocation of the unliganded DR (22), consistent with hsp90 being an agent of cytoplasmic retention. Upon ligand binding, it has been proposed that hsp90 is released from the DR to stimulate activity of a bipartite NLS in the N terminus of the receptor (22). In this manner, the nuclear translocation mechanism of the dioxin receptor is strongly reminiscent of models proposed for nuclear translocation of the GR. In the case of the GR, hsp90 also interacts with the ligand binding domain, and upon ligand binding the receptor translocates to the nucleus and forms a homodimer with DNA binding activity (46). While hsp90 is critical for keeping both the GR and DR in their latent forms, it has not previously been determined whether these receptors shed hsp90 before or after entering the nucleus. As with the DR, small immunophilin molecules are found associated with the GR-hsp90 complex and are postulated to have a role in nuclear targeting of the GR (51). One scenario suggests that the complete GR-hsp90 complex may pass through to the nucleus. It has been shown that such a complex is not restricted from passing through the nuclear pore in a study where the nucleoplasmin NLS was attached to hsp90 to allow cotranslocation of NLS mutant glucocorticoid and progesterone receptors (30).

Our results show that constitutive nuclear localization of the DR can be achieved by placing exogenous NLSs at the extreme C terminus. The natural bipartite NLS of the DR is in the N terminus, incorporating basic residues within the bHLH region (22). Interestingly, the N-terminal bHLH region is a secondary, weaker site for hsp90 interaction (2), suggesting that the NLS may be sterically masked in the unliganded state. We find that in untreated cells, our DR-NLS protein translocates to the nucleus with hsp90 attached (Fig. 3c and d), avoiding cytoplasmic retention due to the freely available NLS at the C terminus. Once in the nucleus, the DR-NLS protein remains in a latent state, needing the presence of ligand to initiate heterodimerization with Arnt (Fig. 3b).

Treatment with geldanamycin, a ligand for hsp90 that is known to disrupt hsp90 interactions with a number of substrates, renders the constitutively nuclear receptor extremely susceptible to degradation. This phenomenon has also been seen during studies of other hsp90 binding factors such as steroid hormone receptors, Src, and Raf (8). In the case of steroid hormone receptors, geldanamycin has been proposed to prevent association of hsp90 with the receptors rather than dissociate existing receptor-hsp90 complexes (58). Contrary to this, we present evidence that geldanamycin has the ability to influence preexisting DR-hsp90 complexes, as geldanamycin was able to both disrupt the ability of hsp90 to copurify with the DR-NLS protein (Fig. 4c) and generate an in vitro DNA binding DR-Arnt complex from Hepa cytosol (Fig. 5). We have yet to conclusively determine whether geldanamycin acts by completely dissociating preexisting DR-hsp90 complexes or instead by inducing conformational changes in the DR-hsp90 complex and thus rendering the DR competent for heterodimerization with Arnt.

The extreme lability of the DR upon geldanamycin treatment of Y1/DR-NLS cells indicates that it is highly improbable that an inadequately chaperoned form of receptor can exist within the cell. Therefore, how does ligand treatment process the native DR, which is cytoplasmic and hsp90 bound, into the nuclear heterodimeric complex with Arnt? Upon ligand binding of the native cytosolic receptor, we envisage a conformational change taking place within the DR to release hsp90 from its weak interaction with the bHLH region, exposing the NLS. In this scenario, the native DR would translocate to the nucleus bound with both ligand and hsp90 and upon entry into the nucleus would interact with Arnt via the exposed N-terminal bHLH region. Following this initial interaction, we envisage a concerted mechanism whereby the DR and Arnt PAS domains form a strong association concomitant with full hsp90 release from the DR PAS B region (Fig. 8), thus avoiding any presence of nonpartnered, labile DR. Importantly, this mechanism is consistent with recent in vitro studies of DR activation. Ligand treatment of Arnt-free cytosolic extracts, or in vitro translation mixtures containing the hsp90-DR complex, was shown to be highly inefficient at disrupting hsp90-DR complexes. Addition of Arnt in conjunction with ligand resulted in release of hsp90 as shown by the loss of coprecipitated DR with anti-hsp90 antibodies (39). Taken together, these data indicate that within cells, a nuclear mechanism involving concerted exchange of hsp90 for Arnt is a key step in the DR activation process.

FIG. 8.

Model for ligand-induced transformation of the cytosolic DR to the nuclear DR-Arnt heterodimer. Ligand binding stimulates release of hsp90 from the N terminus, exposing the NLS to promote nuclear import of the PAS B-bound hsp90-DR complex. Once in the nucleus, interaction of the free bHLH domain with Arnt initiates concomitant release of hsp90 and formation of the mature DR-Arnt heterodimer. See text for details.

The role of ligand in DR activation.

Our results demonstrate that a constitutively nuclear DR remains in its latent state, needing stimulation with ligand to form an active heterodimer with Arnt. Importantly, this observation reveals that interaction with ligand has functions beyond merely initiating nuclear translocation of the DR. This is emphasized by the fact that ligands for either hsp90 or the DR can induce DR-Arnt heterodimers capable of recognizing the cognate XRE sequence, although only the dioxin-stimulated heterodimer can activate transcription. As cotreatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 is necessary to obtain a stable receptor from geldanamycin-treated Y1/DR-NLS cells, it is possible that the receptor is modified by ubiquitination, resulting in its lack of activity. However, MG132 cotreatment with dioxin results in an increase of reporter gene activity compared to treatment of dioxin alone in the Y1/DR-NLS cells, arguing against this mechanism. Another possible explanation for the lack of transcriptional activity of the geldanamycin-transformed receptor is that the receptor needs a defined structure of the ligand binding domain, normally produced by interaction with ligand, to be transcriptionally active. In the case of steroid hormone receptors, ligand plays a critical role in defining the structure of transcriptionally active receptors. For example, crystal structures show that binding of estradiol to the estrogen receptor positions the AF-2 transactivation domain correctly for induction of transcription, while antiestrogens produce a conformation which misplaces this domain (4). Interestingly, both estrogens and antiestrogens can derepress the inhibitory function of the estrogen receptor ligand binding domain when it is attached to heterologous proteins such as the FLP recombinase (43), indicating that derepression and activation can be distinct mechanistic processes and illustrating that ligands can play multifunctional roles in transformation of nuclear receptors to active transcription factors.

We and others have previously shown that the C-terminal transactivation domain of the DR functions autonomously when attached to a heterologous DNA binding domain such as that of GAL4 or the GR zinc finger (25, 36, 71). Therefore, the presence of ligand is not essential to the intrinsic activity of the DR transactivation domain. However, when portions of the ligand binding domain were included in these chimeras, they repressed activity of the transactivation domain. As the ligand binding domain coincides with the primary hsp90 binding region, hsp90 is a logical candidate for the agent of repression, and these chimeras were therefore analyzed in a yeast system where hsp90 levels were dramatically lowered. The chimeras were also repressed in the low-hsp90 environment, revealing that the unchaperoned ligand binding domain maintained its repressive activity (72). Moreover, it has recently been found that a deletion mutant of the DR which lacks the ligand binding control region can activate transcription in the absence of any inducer (40a). Thus, the ligand binding domain functions as a potent repression domain which can be counteracted by interaction with ligand.

What is the function of ligand during conversion of the DR to the Arnt heterodimeric complex? We favor a mechanism where ligand is important to maintain the structural integrity of the PAS B ligand binding/hsp90 binding region. The geldanamycin-induced DR-Arnt heterodimer provides a nonfunctional complex due to the ability of the unchaperoned ligand binding domain to disrupt the transactivation function of the DR-Arnt C-terminal complex in a similar fashion to that previously observed during our analysis of GR-DR chimeric proteins in low-hsp90 yeast (72). It is notable that in the nuclear receptor superfamily, examples of retinoid X receptor heterodimers exist where ligand binding to one subunit can influence the structure and function of a transactivation domain in the other subunit (45). Our data are consistent with a role for DR ligands in providing a derepressed structure to the PAS B region during transformation to the Arnt heterodimer. This hypothesis is also consistent with the PAS B region forming the core ligand and hsp90 binding domain of the DR (70), as well as being a key region for interaction with Arnt (72). It has recently been proposed that intracellular DR ligands also exist (7), which may help structure this region during potential endogenous activation mechanisms. It will now be important to assess whether the PAS B domains of other bHLH/PAS proteins, such as HIF-1a, form key sites for hsp90 and Arnt interaction and whether chaperoning of these regions is critical during formation of their transcription-activating heterodimers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Chris Bradfield (University of Wisconsin) for the mouse DR cDNA, Yoshiaki Fujii-Kuriyama (Tohoku University) for Arnt antiserum, Gary Perdew (Pennsylvania State University) for the RPT1 DR and anti-hsp90 MAb 3B6, Anna Berghard (Umeå, Sweden) for the pX1X1 reporter plasmid, Steven Rees (Glaxo Wellcome) for pCIN4, and Steve Hobbs (IRC, London, England) for pEF/IRES-p. We thank Lorenz Poellinger and Jacqueline McGuire (Karolinska Institute) for helpful discussions and communication of results prior to publication.

This work was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott B D, Probst M R. Developmental expression of two members of a new class of transcription factors. II. Expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator in the C57BL/6N mouse embryo. Dev Dyn. 1995;204:144–155. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002040205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonsson C, Whitelaw M L, McGuire J, Gustafsson J A, Poellinger L. Distinct roles of the molecular chaperone hsp90 in modulating dioxin receptor function via the basic helix-loop-helix and PAS domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:756–765. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berghard A, Gradin K, Pongratz I, Whitelaw M, Poellinger L. Cross-coupling of signal transduction pathways: the dioxin receptor mediates induction of cytochrome P-450IA1 expression via a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:677–689. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brzozowski A M, Pike A C, Dauter Z, Hubbard R E, Bonn T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene G L, Gustafsson J A, Carlquist M. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carver L A, Bradfield C A. Ligand-dependent interaction of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor with a novel immunophilin homolog in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11452–11456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carver L A, Jackiw V, Bradfield C A. The 90-kDa heat shock protein is essential for Ah receptor signalling in a yeast expression system. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30109–30112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang C Y, Puga A. Constitutive activation of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:525–535. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H S, Singh S S, Perdew G H. The Ah receptor is a sensitive target of geldanamycin-induced protein turnover. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;348:190–198. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H W, Lin R J, Schiltz R L, Chakravarti D, Nash A, Nagy L, Privalsky M L, Nakatani Y, Evans R M. Nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric activation complex with p/caf and cbp/p300. Cell. 1997;90:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coumailleau P, Poellinger L, Gustafsson J A, Whitelaw M L. Definition of a minimal domain of the dioxin receptor that is associated with Hsp90 and maintains wild type ligand binding affinity and specificity. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25291–25300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eguchi H, Ikuta T, Tachibana T, Yoneda Y, Kawajiri K. A nuclear localization signal of human aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator/hypoxia-inducible factor 1β is a novel bipartite type recognized by the two components of nuclear pore-targeting complex. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17640–17647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ema M, Morita M, Ikawa S, Tanaka M, Matsuda Y, Gotoh O, Saijoh Y, Fujii H, Hamada H, Kikuchi Y, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Two new members of the murine Sim gene family are transcriptional repressors and show different expression patterns during mouse embryogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5865–5875. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ema M, Taya S, Yokotani N, Sogawa K, Matsuda Y, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. A novel bHLH-PAS factor with close sequence similarity to hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha regulates the VEGF expression and is potentially involved in lung and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4273–4278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Salguero P, Pineau T, Hilbert D M, McPhail T, Lee S S, Kimura S, Nebert D W, Rudikoff S, Ward J M, Gonzalez F J. Immune system impairment and hepatic fibrosis in mice lacking the dioxin-binding Ah receptor. Science. 1995;268:722–726. doi: 10.1126/science.7732381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gradin K, McGuire J, Wenger R H, Kvietikova I, Whitelaw M L, Toftgard R, Tora L, Gassmann M, Poellinger L. Functional interference between hypoxia and dioxin signal transduction pathways: competition for recruitment of the Arnt transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5221–5231. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hapgood J, Cuthill S, Denis M, Poellinger L, Gustafsson J A. Specific protein-DNA interactions at a xenobiotic-responsive element: copurification of dioxin receptor and DNA-binding activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:60–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hobbs S, Jitrapakdee S, Wallace J C. Development of a bicistronic vector driven by the human polypeptide chain elongation factor 1 alpha promoter for creation of stable mammalian cell lines that express very high levels of recombinant proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:368–372. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman E C, Reyes H, Chu F F, Sander F, Conley L H, Brooks B A, Hankinson O. Cloning of a factor required for activity of the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Science. 1991;252:954–958. doi: 10.1126/science.1852076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogenesch J B, Chan W K, Jackiw V H, Brown R C, Gu Y Z, Pray-Grant M, Perdew G H, Bradfield C A. Characterization of a subset of the basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS superfamily that interacts with components of the dioxin signalling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8581–8593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hord N G, Perdew G H. Physicochemical and immunocytochemical analysis of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator: characterization of two monoclonal antibodies to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:618–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Z J, Edery I, Rosbash M. PAS is a dimerization domain common to Drosophila period and several transcription factors. Nature. 1993;364:259–262. doi: 10.1038/364259a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikuta T, Eguchi H, Tachibana T, Yoneda Y, Kawajiri K. Nuclear localization and export signals of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2895–2904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaac D D, Andrew D J. Tubulogenesis in Drosophila: a requirement for the trachealess gene product. Genes Dev. 1996;10:103–117. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyer N V, Kotch L E, Agani F, Leung S W, Laughner E, Wenger R H, Gassmann M, Gearhart J D, Lawler A M, Yu A Y, Semenza G L. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev. 1998;12:149–162. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain S, Dolwick K M, Schmidt J V, Bradfield C A. Potent transactivation domains of the Ah receptor and the Ah receptor nuclear translocator map to their carboxyl termini. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31518–31524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang B H, Zheng J Z, Leung S W, Roe R, Semenza G L. Transactivation and inhibitory domains of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Modulation of transcriptional activity by oxygen tension. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19253–19260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kallio P J, Okamoto K, O’Brien S, Carrero P, Makino Y, Tanaka H, Poellinger L. Signal transduction in hypoxic cells: inducible nuclear translocation and recruitment of the CBP/p300 coactivator by the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha. EMBO J. 1998;17:6573–6586. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kallio P J, Pongratz I, Gradin K, McGuire J, Poellinger L. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha: posttranscriptional regulation and conformational change by recruitment of the Arnt transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5667–5672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamei Y, Xu L, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Kurokawa R, Gloss B, Lin S C, Heyman R A, Rose D W, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell. 1996;85:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang K I, Devin J, Cadepond F, Jibard N, Guiochon-Mantel A, Baulieu E E, Catelli M G. In vivo functional protein-protein interaction: nuclear targeted hsp90 shifts cytoplasmic steroid receptor mutants into the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:340–344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerry D M, Dwivedi P P, Hahn C N, Morris H A, Omdahl J L, May B K. Transcriptional synergism between vitamin D-responsive elements in the rat 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase (CYP24) promoter. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29715–29721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King D P, Zhao Y, Sangoram A M, Wilsbacher L D, Tanaka M, Antoch M P, Steeves T D, Vitaterna M H, Kornhauser J M, Lowrey P L, Turek F W, Takahashi J S. Positional cloning of the mouse circadian clock gene. Cell. 1997;89:641–653. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozak K R, Abbott B, Hankinson O. ARNT-deficient mice and placental differentiation. Dev Biol. 1997;191:297–305. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindebro M C, Poellinger L, Whitelaw M L. Protein-protein interaction via PAS domains: role of the PAS domain in positive and negative regulation of the bHLH/PAS dioxin receptor-Arnt transcription factor complex. EMBO J. 1995;14:3528–3539. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma Q, Whitlock J., Jr A novel cytoplasmic protein that interacts with the Ah receptor, contains tetratricopeptide repeat motifs, and augments the transcriptional response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8878–8884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma Q, et al. Transcriptional activation by the mouse Ah receptor. Interplay between multiple stimulatory and inhibitory functions. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12697–12703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maltepe E, Schmidt J V, Baunoch D, Bradfield C A, Simon M C. Abnormal angiogenesis and responses to glucose and oxygen deprivation in mice lacking the protein ARNT. Nature. 1997;386:403–407. doi: 10.1038/386403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McEwan I J, Wright A P, Gustafsson J A. Mechanism of gene expression by the glucocorticoid receptor: role of protein-protein interactions. Bioessays. 1997;19:153–160. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38a.McGuire, J. Personal communication.

- 39.McGuire J, Coumailleau P, Whitelaw M L, Gustafsson J A, Poellinger L. The basic helix-loop-helix/PAS factor Sim is associated with hsp90. Implications for regulation by interaction with partner factors. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31353–31357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGuire J, Whitelaw M L, Pongratz I, Gustafsson J A, Poellinger L. A cellular factor stimulates ligand-dependent release of hsp90 from the basic helix-loop-helix dioxin receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2438–2446. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40a.McGuire, J., et al. Unpublished data.

- 41.Meyer B K, Pray-Grant M G, Vanden Heuvel J P, Perdew G H. Hepatitis B virus X-associated protein 2 is a subunit of the unliganded aryl hydrocarbon receptor core complex and exhibits transcriptional enhancer activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:978–988. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mimura J, Yamashita K, Nakamura K, Morita M, Takagi T N, Nakao K, Ema M, Sogawa K, Yasuda M, Katsuki M, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Loss of teratogenic response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice lacking the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Genes Cells. 1997;2:645–654. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1490345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nichols M, Rientjes J M, Stewart A F. Different positioning of the ligand-binding domain helix 12 and the F domain of the estrogen receptor accounts for functional differences between agonists and antagonists. EMBO J. 1998;17:765–773. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Numayama-Tsuruta K, Kobayashi A, Sogawa K, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. A point mutation responsible for defective function of the aryl-hydrocarbon-receptor nuclear translocator in mutant Hepa-1c1c7 cells. Eur J Biochem. 1997;246:486–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peet D J, Janowski B A, Mangelsdorf D J. The LXRs: a new class of oxysterol receptors. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:571–575. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Picard D, Yamamoto K R. Two signals mediate hormone-dependent nuclear localization of the glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO J. 1987;6:3333–3340. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poellinger L. Mechanisms of signal transduction by the basic helix-loop-helix dioxin receptor. In: Baeuerle P A, editor. Inducible gene expression. Vol. 1. Boston, Mass: Birkhauser; 1995. pp. 177–205. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pollenz R S, Sattler C A, Poland A. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator protein show distinct subcellular localizations in Hepa 1c1c7 cells by immunofluorescence microscopy. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:428–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pongratz I, Antonsson C, Whitelaw M L, Poellinger L. Role of the PAS domain in regulation of dimerization and DNA binding specificity of the dioxin receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4079–4088. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pongratz I, Mason G G, Poellinger L. Dual roles of the 90-kDa heat shock protein hsp90 in modulating functional activities of the dioxin receptor. Evidence that the dioxin receptor functionally belongs to a subclass of nuclear receptors which require hsp90 both for ligand binding activity and repression of intrinsic DNA binding activity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13728–13734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pratt W B, Toft D O. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocrine Rev. 1997;18:306–360. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prodromou C, Roe S M, O’Brien R, Ladbury J E, Piper P W, Pearl L H. Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell. 1997;90:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pugh C W, O’Rourke J F, Nagao M, Gleadle J M, Ratcliffe P J. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1; definition of regulatory domains within the alpha subunit. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11205–11214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rees S, Coote J, Stables J, Goodson S, Harris S, Lee M G. Bicistronic vector for the creation of stable mammalian cell lines that predisposes all antibiotic-resistant cells to express recombinant protein. BioTechniques. 1996;20:102–104. doi: 10.2144/96201st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54a.Roberts, B. J., and M. L. Whitelaw. Unpublished data.

- 55.Schmidt J V, Bradfield C A. Ah receptor signalling pathways. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:55–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmidt J V, Su G H, Reddy J K, Simon M C, Bradfield C A. Characterization of a murine Ahr null allele: involvement of the Ah receptor in hepatic growth and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6731–6736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schulte T W, Blagosklonny M V, Ingui C, Neckers L. Disruption of the Raf-1-Hsp90 molecular complex results in destabilization of Raf-1 and loss of Raf-1-Ras association. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24585–24588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Segnitz B, Gehring U. The function of steroid hormone receptors is inhibited by the hsp90-specific compound geldanamycin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18694–18701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sogawa K, Nakano R, Kobayashi A, Kikuchi Y, Ohe N, Matsushita N, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Possible function of Ah receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt) homodimer in transcriptional regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1936–1940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sonnenfeld M, Ward M, Nystrom G, Mosher J, Stahl S, Crews S. The Drosophila tango gene encodes a bHLH-PAS protein that is orthologous to mammalian Arnt and controls CNS midline and tracheal development. Development. 1997;124:4571–4582. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stebbins C E, Russo A A, Schneider C, Rosen N, Hartl F U, Pavletich N P. Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent. Cell. 1997;89:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun Z S, Albrecht U, Zhuchenko O, Bailey J, Eichele G, Lee C C. RIGUI, a putative mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila period gene. Cell. 1997;90:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swanson H I, Chan W K, Bradfield C A. DNA binding specificities and pairing rules of the Ah receptor, ARNT, and SIM proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26292–26302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tei H, Okamura H, Shigeyoshi Y, Fukuhara C, Ozawa R, Hirose M, Sakaki Y. Circadian oscillation of a mammalian homologue of the Drosophila period gene. Nature. 1997;389:512–516. doi: 10.1038/39086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tian H, McKnight S L, Russell D W. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:72–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Voegel J J, Heine M J, Zechel C, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. TIF2, a 160 kDa transcriptional mediator for the ligand-dependent activation function AF-2 of nuclear receptors. EMBO J. 1996;15:3667–3675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang G L, Jiang B H, Rue E A, Semenza G L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ward M P, Mosher J T, Crews S T. Regulation of bHLH-PAS protein subcellular localization during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1998;125:1599–1608. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weiss C, Kolluri S K, Kiefer F, Gottlicher M. Complementation of Ah receptor deficiency in hepatoma cells: negative feedback regulation and cell cycle control by the Ah receptor. Exp Cell Res. 1996;226:154–163. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whitelaw M L, Gottlicher M, Gustafsson J A, Poellinger L. Definition of a novel ligand binding domain of a nuclear bHLH receptor: co-localization of ligand and hsp90 binding activities within the regulable inactivation domain of the dioxin receptor. EMBO J. 1993;12:4169–4179. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whitelaw M L, Gustafsson J A, Poellinger L. Identification of transactivation and repression functions of the dioxin receptor and its basic helix-loop-helix/PAS partner factor Arnt: inducible versus constitutive modes of regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8343–8355. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whitelaw M L, McGuire J, Picard D, Gustafsson J A, Poellinger L. Heat shock protein hsp90 regulates dioxin receptor function in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4437–4441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whitesell L, Mimnaugh E G, De Costa B, Myers C E, Neckers L M. Inhibition of heat shock protein HSP90-pp60v-src heteroprotein complex formation by benzoquinone ansamycins: essential role for stress proteins in oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8324–8328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]