Abstract

Background

The manifestations of COVID‐19 as outlined by imaging modalities such as echocardiography, lung ultrasound (LUS), and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging are not fully described.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the current literature and included studies that described cardiovascular manifestations of COVID‐19 using echocardiography, CMR, and pulmonary manifestations using LUS. We queried PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science for relevant articles. Original studies and case series were included.

Results

This review describes the most common abnormalities encountered on echocardiography, LUS, and CMR in patients infected with COVID‐19.

Keywords: cardiac imaging, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, COVID19, echocardiography, ultrasonography

1. INTRODUCTION

The pandemic caused by novel coronavirus infection (COVID‐19) has completely transformed the way of life for both patients and physicians around the globe. Since its inception in December 2019, COVID‐19 has spiraled exponentially with more than 165 million documented cases and over 3.4 million fatalities worldwide as of mid‐May, 2021.1 Given its multifaceted cardiac manifestations and a fatality rate estimated at 10.5% for cardiovascular disease related complications, COVID‐19 has had a disproportionate impact on the diagnosis and management of cardiovascular diseases. Our study aims to provide an overview of current findings and recommendations in cardiovascular imaging in patients with COVID‐19.

2. METHODS

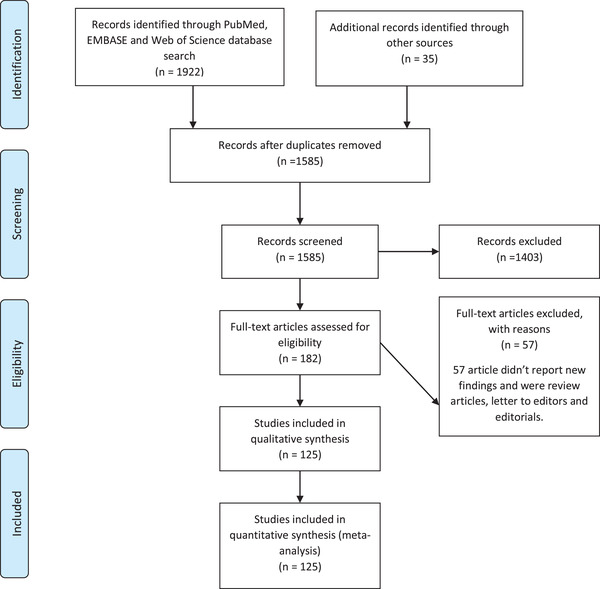

We performed a systematic search of the PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of science databases to identify relevant articles from the inception of the database to October 2, 2020. The search strategy used in each database is elaborated in Table S1. Extracted citations were imported into Mendeley reference manager and screened for relevance. Screening was performed at two levels. At the first level, articles and abstracts were screened for relevance. At the second level, articles identified by title and abstract screening were subjected to full text review. A second manual search was performed to identify articles published after the initial search until publication. The PRISMA flow chart for inclusion of studies is described in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow chart for study inclusion

2.1. Echocardiography in patients with COVID‐19

2.1.1. Indications for echocardiography in COVID‐19 patients

The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) and other clinical societies have established appropriate criteria for the use of echocardiography (ECHO) in patients admitted to the hospital.2 Given the increasing evidence for cardiovascular manifestations of COVID‐19, and the increasing role of bedside focused cardiac ultrasound (FoCUS) in clinical management, performing a focused bedside ECHO among patients with COVID‐19 can prove beneficial, especially in the critically ill.3, 4, 5 Although, performing an ECHO solely based on troponin elevation is not recommended, there is an increasing body of data suggesting that elevated troponin (> 99th percentile on admission) is an important predictor of mortality and length of hospital stay in patients with COVID‐19.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Similarly, NT‐ProBNP has also been found to be elevated among a significant number of patients with COVID‐19 and is an important predictor of mortality.11 One study demonstrated that among patients with COVID‐19, echocardiogram changed the management in 33% of patients who exhibited a variety of symptoms and signs including chest pain, electrocardiogram (EKG) changes, and elevated cardiac biomarkers.12, 13

2.2. Technical considerations of obtaining echocardiogram during COVID‐19 pandemic

2.2.1. Transthoracic and transesophageal ECHO (TTE and TEE) in COVID‐19 patients – Safety constraints for health care personnel

Despite studies demonstrating that health care workers have a significantly higher risk of acquiring COVID‐19 due to increased workplace exposure to patients,14 the data regarding the incidence of COVID‐19 among ECHO sonographers is scarce.

In a recent cross‐sectional study that surveyed sonographers in major academic centers in New York (NY, USA), it was found that there was an infrequent use of plastic ECHO machine covers (9%), barriers between the patient and sonographer (11%), and probe covers (30%) during the procedures. In addition, about a quarter of respondents reported a lack of training in disinfection practices of ultrasound equipment.15 Such findings highlight the need for more stringent adherence to the ASE and American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine's guidelines for protection of patients and ECHO providers to safeguard this vulnerable population.16

2.2.2. Transthoracic echo (TTE) in prone patients with COVID‐19

It was found that raising the patient's left arm and placing a pillow or a folded sheet underneath the mid‐thoracic wall to maintain the left hemithorax slightly elevated to allow a comfortable transducer manipulation, resulted in successful apical four and five chamber views and related measurements.17 Alternatively, the lower thoracic section of the patient's air mattress can be temporarily deflated, taking advantage of the gravitational effect of the heart and its shift towards the chest wall while obtaining an apical four chamber view. These views were adequate to estimate the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), mitral annular plane systolic excursion, mitral valve, and annular doppler velocities, aortic valve doppler velocity, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), and pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP).18

2.2.3. Contrast echocardiography in patients undergoing extra‐corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

Though, the use of ultrasound enhancement agents (UEAs) during TTE have been evaluated in COVID‐19 patients who were spontaneously breathing or on mechanical ventilation,19, 20, 21 their use during TTE in the setting of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for COVID‐19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) can be potentially problematic. UAE can trigger an air bubble alarm, which is integrated in ECMO circuits as a safety measure. This can result in stoppage of the ECMO circuit forward flow or engaging a “Zero‐flow mode” which can result in rapid deterioration of hypoxic patients who are dependent on ECMO flow.22 Bleakley et al. used a protocol that involves the deactivation of air‐bubble alarms before administration of contrast to avoid such potential complication.22

2.2.4. Transesophageal echo (TEE) in COVID‐19: A new outlook

TEE offers multiple advantages, including better imaging windows by virtue of the TEE probe being close to the cardiac chambers and great vessels compared with conventional TTE probes. In addition, TEE is not hampered by other factors such as high positive end‐expiratory pressure (PEEP) ventilation, prone position, body habitus, and emphysematous lungs, that constitute a limiting factor for obtaining good images by TTE.23, 24 Studies demonstrated that superior vena caval (SVC) collapsibility index (which requires TEE) was superior to inferior vena cava (IVC) distensibility index (measured using TTE) in predicting fluid responsiveness.25, 26 Also, TEE can be used to better evaluate the right ventricular (RV) fractional area change (FAC)27 and tricuspid longitudinal annular displacement (TMAD)28, 29 which are surrogates of RV dysfunction.

TTE and TEE can play a role in identifying patients who will benefit from veno‐venous ECMO versus veno‐arterial ECMO. Also, they can be useful tools for assisting in cannulations and troubleshooting the device.30, 31, 32, 33 For instance, embryologic remnants of right heart structures or other congenital abnormalities may affect the safe and appropriate placement of venous cannulas during ECMO initiation. A persistent left SVC leading to a dilated coronary sinus may be accidentally cannulated, leading to compromised oxygenation on ECMO. Similarly, a prominent Chiari network may impede cannula positioning and may increase the risk of subsequent thrombosis. TEE guidance can help in confirming the course of a guidewire during insertion and help in excluding coiling of the guidewire in the right atrium, crossing of the guidewire across the interatrial septum or its entrance in the coronary sinus. It can also ensure that, the return cannula is positioned clear of the interatrial septum and the tricuspid valve, thereby, reducing the risk for re‐cannulation.33, 34, 35, 36, 37 TEE can also help identify the cause for worsening hypoxemia during ECMO, which includes scenarios where the cannula tips are too close to each other, causing recirculation, hypovolemia causing inadequate ECMO flow and thrombus formation in the cannula which may be impeding adequate flow.32

Despite the numerous advantages TEE has over TTE, there is an increased risk of aerosol exposure to healthcare providers during a TEE when compared with a conventional TTE. Adoption of adequate personal protective measures as per current guidelines should lead to a decreased risk of acquiring transmissible diseases while performing TEE.16

2.2.5. Key echocardiographic findings in patients with COVID‐19

Due to the multi‐factorial nature of cardiac involvement in COVID‐19, various studies have demonstrated diverse cardiac manifestations [Table 1].

TABLE 1.

Echocardiographic findings in COVID 19

| Study | Design | N | COVID‐19 severity | LV parameters (EF/ Mass index/LVOT VIT/ Takotsubo) | RV parameters (TAPSE/FAC/RV/LV ratio/PAP/ IVC parameters) | LV strain | Strain analysisRV global/free wall strain‐ | Other | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Li et al. | Retrospective | 49 | Severe and very severe | LVEF severely reduced in severe COVID‐19 | IVC Max and Min significantly increased in severe COVID‐19. | NA | NA | NA | TAPSE is more impaired in severe ARDS as compared to mild ARDS |

| Sud et al. | Retrospective | 24 patients with significant myocardial injury defined as cardiac toponin more 1 ng/ml | 10/24 were mechanically ventilated |

13/24 patients had LV dysfunction. 11/24 had regional wall motion abnormalities, 4/11 within one single coronary vessel territory |

Isolated RV dysfunction in 4/24 patients | NA | NA |

Patients with LV dysfunction had median troponin of 12 ng/ml IQR, 5.8–27.0 ng/ml. ‐ Troponin was 1.5 ng/ml (IQR, 1.3–3.1 ng/ml in patients with isolate RV dysfunction |

In patients with severe chemical cardiac injury LV dysfunction was observed in almost 50% of patients. |

| Giustino et al. | Multicenter retrospective | 305 | Varying severity | In patients with elevated troponins, regional WMA was more frequently encountered. Apical WMA followed by mid segments were most common. LVEDV, Septal wall thickness, Pw thickness were significantly increased in those with myocardial injury | RV function was significantly more impaired in those with elevated cardiac biomarkers | NA | NA | NA | Patients with COVID‐19 with myocardial injury and WMA have a poorer prognosis than those without WMA |

| Hani M. Mahmoud‐Elsayed et al. | Retrospective study | 35 | Patients with cardiac symptoms | Right ventricle (RV) dilatation (41%) and RV dysfunction (27%). RV impairment was associated with increased D‐dimer and C‐reactive protein levels | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Jain et al. | Retrospective study | 72 | NA |

43 patients had normal LVEF 25 reduced LVEF |

RV size was normal in 50 patients and decreased in the rest. 34 patients had reduced RVEF |

NA | NA | NA | There is a significance correlation LVEF and HS troponin (ρ = −.34, p = .006) and LVEF and NT ProBNP (NT‐proBNP and LVEF (ρ = −.29, P = .056) |

| Bleakly et al. | Retrospective study | 10 patents received ultrasound enhancing agents on VV ECMO | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | A zero‐flow mode can be used to ensure the bubbles from contrast will not shut down the ECMO system and ensure there is no back flow in the circuit |

| Giustiniano at el. | Retrospective study | 107 prone patients with only 8 of them receiving echocardiogram while proned | ICU | When prone, 6/18 did not have change in LVEF | When prone RV diameter reduced in 5/8 patients and increased In 2 PAPs decreased in 6/8 patients and augmented only in 1 | NA | NA | 1/8 patients died, he had increased PAP after proning | NA |

| Argulian et al. | Retrospective study | 33 |

14 (ventilated) 19 (not ventilated) |

10/33 had decreased EF | 13/33 RV enlargement | NA | NA | RV /LV parameters not provided | Ultrasonic agents are safe and increase diagnostic yield of bedside echo |

| Garcia cruz et al. | Retrospective study | 15 | Severe ICU, intubated | 6/15 decreased EF via low MAPSE < 13 mm | Mean TAPSE 17.8 mm, | NA | NA | NA | Transesophageal echo is feasible in patients that are prone positioned in the ICU. |

| Jain et al. | Retrospective study | 72 | NA | 25/72 had low EF < 50% | 29/72 decrease RV systolic function | NA | NA | NA | TTE is a valuable tool in guiding management of COVID‐19 patients. |

| Bursi et al. | Retrospective study | 49 | Mild, mod, severe 11 patients were intubated, 1 was in bilevel positive airway pressure, 17 were in continuous positive airway pressure, 9 were in face mask with high oxygen flow, and 11 were in nasal cannula | LVEF 53 ± 12% | TAPSE 20 ± 4 mm, FAC 41 ± 8%, | LV GLS −15 ± 4% | RV‐GLS −15 ± 5% | NA | Offline 2D echo with speckle tracking can be used in cardiac evaluation of COVID 19 patients. RV strain and TAPSE are associated with higher mortality, RV dysfunction is also a common finding. |

| Bursi F et al. | Prospective study | 49 |

Survivors‐33 Non‐survivors‐16 |

NA | TAPSE, TAPSE/ PASP were significantly reduced in non survivors compared to survivors. No significant difference in RVFAC and PASP | LVGLS was significantly reduced in non survivors compared to survivors | RVGLS and RVFWS were significantly reduced in non‐survivors compared to survivors | NA | Both RVFWS and RVGLS are predictive of death in COVID 19 patients (AUC .77 ± .08 in, p = 0.008, and .79 ± .04, p = 0.004, and this remained significant after controlling for multiple parameters |

| Liu et al. | Prospective study | 43 | ICU | LVSVi and E/E` were significantly reduced in non survivors compared to survivors (p < 0.01 and 0.01 respectively) |

Non‐survivors versus survivors RVDbasal, RVDbasal to apex and PASP were significanly increased (p 0.049, 0.049, and 0.02 respectively) TAPSE, S` were significantly less (p < 0.001 for both) |

NA | NA | the strongest predictor of in‐ICU death was decreased cardiac index [hazard ratio (HR), .67, 95% confidence interval (CI), .45–.98; p = 0.041 |

Pericardial effusion (90.7%), increased left ventricular mass index (60.5%), LV mass was increased in 22 patients, however not different between survivals and non‐ survivals |

| Krishnamoorthi P et al. | Prospective study | 12 | No‐intubation or death versus intubated or died | LVEF and LVGLS was not significantly different between both groups (.71 and .52 respectively) |

RVGLS and RVFWS were significantly higher in patients who did not need intubation or survived (p = 0.007 for both) RVSP was not significantly different between both groups |

NA | NA | NA | LVGLS was reduced in both groups, RVGLS and RVFWS were decreased in patients with poor outcomes. |

| Baycan et al. | Prospective study | 100 | NA | GLS was more in severe group compared to non‐severe and control. LV‐GLS: ‐ 14.5 ± 1.8 versus ‐ 16.7 ± 1.3 versus ‐ 19.4 ± 1.6, respectively [p < 0.001] | RV‐LS: Severe‐ 17.2 ± 2.3 versus non severe ‐ 20.5 ± 3.2 versus Control ‐ 27.3 ± 3.1, respectively [p < 0.001] | Patients in the severe group, LV‐GLS and RV‐LS were decreased compared to patients in the non‐severe and control groups (LV‐GLS: ‐ 14.5 ± 1.8 vs ‐ 16.7 ± 1.3 vs ‐ 19.4 ± 1.6, respectively [p < 0.001]; RV‐LS: ‐ 17.2 ± 2.3 vs ‐ 20.5 ± 3.2 vs ‐ 27.3 ± 3.1, respectively [p < 0.001]) | LV‐GLS and RV‐LS are independent predictors of in‐hospital mortality in patients with COVID‐19. | ||

| D`Alto et al | Prospective | 94 | Severe | No significant difference in any of the LV parameters between patients who survived and those who did not | TAPSE, PASP, TAPSE/PASP ratio, and IVC were significantly different in patients who survived versus those who did not | NA | NA | NA | TAPSE/PASP ratio(RV uncoupling) and PaO2/FiO2 ratio are independent predictors of mortality of patients with severe COVID‐19 |

| Szekely et al. | Prospective study | 100 | Mild, moderate, severe | LV systolic dysfunction n = 10, EF < 50% LV diastolic dysfunction n = 16 | RV dilation/dysfunction, n = 39 | NA | NA | NA | In COVID19, LV systolic function is preserved, but diastolic and RV function are impaired. Elevated troponin and poorer clinical grade are associated with worse RV function. |

| Demerck et al. | Prospective study | 1216 | NA | 19/1216 takotsubo decreased EF 455/1216 | 313/1216 | NA | NA | RV/LV parameters not provided | In this global survey cardiac abnormalities were detected with ECHO in patients with ECHO |

| Li S, Qu YL, et al. | Prospective study | 91 | severe | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

This study is for the utility of lung US in assessing COVID complications, TTE and cardiac findings were not addressed. Lung US scores not assessed. |

| Schott JP et al. | Prospective study | 66, African American, male, obese, with hypertension, and with diabetes | Severe |

EF by simpson method 60+‐12 12 out of 66 had impaired LVEF not specified how low, out of which seven previously known to have low EF. Normal LV dimensions in 85%. |

RV/LV ratio ranged from .9 ± .3. RV function preserved 72% TAPSE 20.9 ± 5.0 S’ 12.8 ± 3.3. RV dilated in 81.7% mostly mild in 45% RV base 3.7 ± .8. PAP and IVC not properly assessed and were mostly within normal. |

NA | NA | Increased left ventricular (LV) wall thickness was present in 46 (69.7%) with similar incidence of elevated troponin and average troponin levels compared to normal wall thickness (66.7% vs 52.4%, p = 0.231; 0.88 ± 1.9 vs 1.36 ± 2.4 ng/ml, p = .772). LV dilation was rare (n = 6, 9.1%), as was newly reduced LV ejection fraction (n = 2, 3.0%). | RV dil ation is common in SARS‐CoV‐2 but does not correlate with elevated D‐dimer levels. Increased LV wall thickness is common, while newly reduced LV ejection fraction is rare, and neither correlates with troponin levels. |

| Kerrilynn C. Hennessey et al. | Prospective study | 135 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | TTE triage /deferring and cancelling non ICU patients did not affect the patient care. |

| Dweck et al. | Prospective study | 1216 | NA |

55/100 – abnormal echo Left ventricular abnormalities were reported in 479 (39%) In those without pre‐existing cardiac disease (n = 901), the echocardiogram was abnormal in 46%, and 13% had severe disease. |

Right ventricular abnormalities ‐ 397 (33%) | NA | NA | new myocardial infarction in 36 (3%), myocarditis in 35 (3%), and takotsubo cardiomyopathy in 19 (2%). Severe cardiac disease (severe ventricular dysfunction or tamponade) was observed in 182 (15%) patients. | Half the patients with COVID 19 had new abnormalities on echocardiogram, it changed management in third of patients |

| Edgar García‐Cruz et al. | Cross sectional study | 14 | Severe | 6/14 had moderately reduced EF (not specified), those patient had low MAPSE (less than 13), no other characteristics entioned for LV other than 4/16 had LVOT variability(no numbers) | The mean TAPSE was 17.8 mm, the RV S wave 11.5 cm/s, and RV basal diameter 36.6 mm. RV/LV ratio was < 1 in all patients | NA | NA | NA | The study aim was to prove that TT echocardiographic images can be obtained to measure multiple parameters during the prone position ventilation |

| Edgar Garcia et al. | Cross sectional study | 82 | Severe, ICU admission | 11/82 EF < 50% |

23/82 had RV basal diameter > 41 mm 22/82 had TAPSE < 17 mm |

NA | NA | NA | The ORACLE protocol is fast way to evaluate covid‐19 patients. The most frequent ultrasonographic findings were elevated pulmonary artery systolic pressure (69.5%), E/e’ ratio > 14 (29.3%), and right ventricular dilatation (28%) and dysfunction (26.8%) |

| Beyls et al. | Cross sectional study | 54 | Severe, ICU | NA |

Median RV FAC was 43.6% (33.3% to 52.8%), median RV GLS was ‐24.7% (‐22.6% to ‐28.5%) median TMADlat was 23.5 mm (19.0 to 27.9 mm) |

NA | NA | NA | TMAD can be used and is reproducible in assessment of RV function in patients with COVID‐19 related ARDS and prone positioned. |

| Stobe et al. | Cross sectional study | 18 | 14/18 severe, 4/18 mild |

Left‐ventricular mass index (g/m2) 97±19.0 Left‐ventricular ejection fraction (%) 62±6.5 |

NA | NA | Reduced longitudinal strain in more than one basal LV segment 10/14 | Right‐ventricular GLS (%) −26.9±5.8 (for 10 severe, 4 mild) | Study shows myocardial involvement is highly prevalent in patients with COVID‐19. |

| Churchill et al. | Cross sectional study | 125 | 85/125 ICU | 28/125 decreased EF (< 50%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | LV dysfunction is common in patients with elevated troponin |

| Evrard et al. | Case series | 5 patients underwent TEE in prone position | TEE was more useful in determining eccentricity index | NA | NA | NA | NA | TEE may be more useful in prone patient to diagnose acute cor pulmonale and determine eccentricity index | |

| Pacileo et al. | Review article | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Mainly addressing logistics of doing TTE and TEE in COVID pandemic with no mention on TTE findings or relation to severity | NA |

| Teran F, et al. | Expert opinions | Severe | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | The article discusses when TEE is of choice compared to TTE, no Echo parameters not discussed, no patient population mentioned, consensus and advisory for TEE | TEE is of choice in when TTE is inadequate in VV ecmo, cardiac arrest and prone ventilation and also for lung eval, no lung US scores. |

| C. Beyls et al. | Prospective study | 29 | Moderate to severe | NA |

Ten (34%) out of 29 patients had RV dysfunction. ACP was diagnosed in 12 patients (41%). For RV parameters (TAPSE, RV‐S0, and RV‐FAC), no differences were found between the ACP and non‐ACP groups. |

NA | NA | 2D‐STE parameters (RV‐LSF and RVFWLS) were altered markedly in the ACP group compared with the non‐ACP group |

Classic RV function parameters were not altered by ACP in patients with CARDS, contrary to 2D‐STE parameters. RV‐LSF seems to be a valuable parameter to detect early RV systolic dysfunction in CARDS patients with ACP |

| Gonzalez, Filipe et al. | Prospective study | 30 | ICU patients |

Fair relationship between LVEF and LV GLS. The GLS cut‐off value of − 22% identified a LVEF < 50% with a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of 80%. All patients with a GLS > − 17% had a LVEF < 50% |

NA | NA | NA | left ventricular GLS was useful to assess left ventricular systolic function. However, right ventricular GLS was poorly correlated with FAC, TAPSE and S’. | |

| Bhatia, Harpreet S et al. | retrospective cohort study | 67 | Moderate to severe | LV EF was normal in 94% of patients |

GLS was abnormal in 91% of patients, Compared to pre‐COVID‐19 echocardiograms, EF was unchanged, but median GLS was significantly worse |

no significant correlation between GLS and hsTnT levels. NT‐proBNP was also not significantly correlated with GLS (r = .08, p = 0.66, n = 38). |

Patients with COVID‐19 had evidence of subclinical cardiac dysfunction manifested by reduced GLS despite preserved EF | ||

| Krishna, Hema et al. | Retrospective cohort study | 179 | NA | EF < 50% in 29 (16%), RWMA in 26 (15%), global dysfunction in 21 (12%), left ventricular hypertrophy in 36 | RV enlargement in 64 (37%), RV systolic dysfunction in 54 (31%), (RVSP) of 35 mm Hg or greater in 44 (44%), tricuspid regurgitation (TR) of mild‐moderate or greater severity in 49 (27%) |

Left ventricular GLS was performed in 11 patients with events and 18 patients without events and was lower in those with events |

Prior echocardiography was available in 36 (20%) patients and pre‐existing abnormalities were seen in 28 (78%) | bedside Doppler assessment of RVSP may be a useful predictive tool for short‐term risk stratification of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. Caution should be there as pre‐existing abnormalities were common | |

| Shmueli, Hezzy et al. | Retrospective | 60 | NA |

Reduced LVEF (< 50%) 23%. Diastolic Dysfunction 75%. Grade 1:52.5%. Grade 2:17.5%. Grade 3:5.0%. Abnormal LV global longitudinal strain 80%. RWMA + (22%). |

RV systolic function: Normal 47 (81%) Mild: 6 (10.3%) Moderate: 4 (6.9%) Severe: 1 (1.7%) |

abnormal GLS in (80%) of patients. LV‐GLS was significantly reduced in patients with RWMA, compared with those without RWMA. | NA | Subclinical myocardial dysfunction as measured via reduced LV‐GLS is frequent, occurring in 80% of patients hospitalized with COVID‐19, while prevalent LV function parameters such as reduced EF and wall motion abnormalities were less frequent findings | |

| Jain, Renuka et al | Retrospective | 52 | ICU patients |

EF (50%; 64%). 11 had new worsening LV dysfunction. LV function was not associated with morbidity or mortality |

RV enlargement was present in (38%) patients. PAH: 10 (19%). |

Abnormal RV GLS: 28 (78%). |

The most common echocardiographic abnormality is right ventricular dysfunction, which can be assessed more accurately using state‐of‐the‐art echocardiography. | ||

| Li, Yuman et al | Retrospective | 157 | NA |

LV diastolic dysfunction (9.0%), LV systolic dysfunction (5.6%) in CVD patients. CVD patients with high‐sensitivity troponin demonstrated similar systolic or diastolic function compared to normal troponin |

RV dysfunction (30.3%) in CVD patients CVD patients with high troponin showed worsening RV function versus normal troponin |

NA | NA | COVID‐19 patients with CVD had a significantly higher mortality compared to those without |

RV dysfunction is more common than LV dysfunction among COVID‐19 patients with underlying CVD. RV dysfunction is associated with higher mortality. RV function and elevated hs‐TNI level were independent predictors of higher mortality in COVID‐19 patients with CVD. |

| Tudoran, Mariana et al | Retrospective | 125 | Mild to moderate | DD (in 16%). Reduced LV‐SF in 10%. | the prevalence of RVD was only 14.4%. | NA | NA | Alterations of LV‐SF and DD are frequent in post‐acute COVID‐19 infection and are responsible for the persistence of symptoms. | |

| Zhou, Mi et al | Prospective | 97 | Mild cases | impaired left ventricular systolic function with LVEF 44% in 1% only | NA | NA | NA | The most common abnormality was sinus bradycardia | Cardiac abnormality is common amongst COVID‐survivors with mild disease, which is mostly self‐limiting. |

| Norderfeldt, Joakim et al | RETROSPECTIVE | 67 | ICU patients. | NA | 26 patients (39%) displayed a sPAP value of > 35 mm Hg and were designated as having aPH. | NA | NA |

Patients with aPH displayed higher NTproBNP and troponin T plasma levels compared to non‐aPH group. Mortality is higher in the aPH group (46% vs 7%) |

aPH was linked to biomarker‐defined myocardial injury and cardiac failure, as well as an almost sevenfold increase in 21‐d mortality. |

| Günay, Nuran et al. |

Prospective Case‐control |

51 patients 32 healthy |

Moderate to severe | LVEDD and LVESD, IVS and PW, LVEF and LA diameters were similar between the groups |

RVFAC was significantly less in the patient group. Pulmonary artery pressure was significantly higher in the patient group |

RV GLS was less than the control Group. RV free wall strain was significantly less in the patient group. |

subclinical right ventricular dysfunction in the echocardiographic analysis of COVID‐19 patients although there were no risk factors | ||

| Li, Rui et al. | Prospective |

218 patients 23 healthy |

52 critically ill 166 non‐critical |

22% of all patients had reduced LV EF (< 50%). critically ill group had more patients with reduced EF |

83% of all patients had reduced GLS (< −21.0%), critically ill group had more patients with reduced GLS. |

cTnI was elevated in 23 patients (10.8%), including 15 critical cases (28.8%) and eight noncritical cases (4.8%) NT‐proBNP was elevated in 32 patients (15.3%), including 18 critical (34.6%) versus 14 noncritical patients (8.9% |

myocardial dysfunction is common in COVID‐19 patients, particularly those who are critically sick | ||

|

The alteration of GLS was more prominent in the sub‐epicardium than in the sub‐endocardium (p < 0.001) |

|||||||||

| Özer, Savaş et al | prospective | 74 | NA | Left ventricular EF was lower in the group with myocardial injury (58.9 ± 2.1 vs 59.9 ± 1.7, p = 0.032). | NA |

LV‐GLS was found above ‐18 in 28 (37.8%) patients. Sixteen (57.1%) were in the group with the myocardial injury, and 12 (26.1%) were in the group without myocardial injury (p = 0.014) |

NA | troponin levels were correlated with LV‐GLS values (r = .22, p = 0.045). | Subclinical left ventricular dysfunction was observed in approximately one‐third of the patients at the one‐month follow‐up after COVID‐19 infection. This rate was higher in those who develop myocardial injury during hospitalization |

| Bieber, Stéphanie et al. | Prospective | 32 | NA | LV EF was preserved in both troponin + AND – groups. | systolic dysfunction of the right ventricle was observed more often in patients with myocardial injury group. |

impaired left ventricular (LV (GLS) in patients with myocardial injury. GLS significantly improved in follow up |

RV‐FWS significantly improved from baseline to follow‐up. | Concomitant biventricular dysfunction was common in Trop + group | Myocardial dysfunction partially recovered in hsTNT + patients after 52 days of follow‐up. |

| Zhang, Yanting et al. | Prospective case‐controlled |

128 patients 31 healthy |

Severe to critical | NA |

3D‐RVEF was significantly lower in COVID‐19 patients than in controls. critical patients exhibited significantly higher mitral E/e′, larger RA, RV and worse FAC, 2D‐RVFWLS, and 3D‐RVEF and PAH. |

NA | 2D‐RVFWLS was significantly lower in COVID‐19 patients than in controls | RVFAC, 2D‐RVFWLS, and 3D‐RVEF were associated with mortality | 3D‐RVEF was an independent predictor of mortality in COVID‐19 patients and provided an incremental prognostic value superior to RVFWLS |

| Xie, Yuji et al | Prospective | 132 | NA | NA | Higher PH in severe cases and ARDS. | LV GLS4CH is lower in patient with cardiac injury, ARDS and non‐survivors. | RV FWLS is lower in ptn with cardiac injury, ARDS and non‐survivors. |

LV GLS4CH and RV FWLS are independent and strong predictors of higher mortality in COVID‐19 patients. Forty‐six survivors at 3 months after discharge Had significant improvements in LV GLS4CH, RV FWLS in recovered patients, |

Abbreviations: LVSVi (ml/m2, Left ventricular stroke volume index; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; LVGLS, Left ventricular global longitudinal strain; RVFWS, Right ventricular free wall strain; RVGLS, Right ventricular global longitudinal strain; RVSP, Right ventricular systolic pressure; WMA, Wall motion abnormality; Pw, posterior wall thickness.

2.2.6. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP)

PASP was also found to be significantly elevated in a large number of patients presenting with COVID‐19.4, 38 These findings may partly be attributed to a hypercoagulable state associated with systematic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction of the pulmonary vasculature, leading to pulmonary emboli or microthrombi formation affecting the smaller segmental pulmonary arteries, hypoxemia secondary to infection itself or adverse effects of positive pressure ventilation.4, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 In one study, patients with PASP more than 35 mm Hg had significantly higher cardiac biomarkers and were significantly more likely to die as compared with those with PASP less than 35 mm Hg, (46% vs 7%).43 Also, PASP seems to correlate with the severity of the disease.44

2.2.7. Right ventricular (RV) involvement

RV involvement is seen more commonly with multiple studies demonstrating RV dilatation and a range of systolic dysfunction from mild to severe, including documented instance of an acute cor pulmonale like presentation with more severe RV failure seen in more critically ill patients.38, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49

2.3. Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE)

Although, some studies reported TAPSE to be significantly decreased in critically ill COVID‐19 patients, more profoundly affected in severe ARDS as compared with mild ARDS,47, 50, 51, 52, 53 other studies demonstrated no difference in TAPSE between mild forms and more severe infections.48, 54

2.4. Right ventricular fractional area change

RV fractional area change (FAC) performed inconsistently in predicting outcomes or progression in patients with COVID‐19. RVFAC was not significantly different between patients with severe and non‐severe COVID‐19,44, 46 nor survivors, and non‐survivors.47, 55, 56 However, RVFAC was found to be lower in COVID‐19 patients with myocardial injury when compared with COVID‐19 patients without myocardial injury.57, 58 Also, RVFAC does not seem to be significantly decreased even in COVID‐19 patients with acute cor‐pulmonale as compared with those with no acute cor‐pulmonale.59

2.5. Right ventricular strain patterns in COVID‐19

RV free wall strain (RVFWS) seems to be a sensitive marker for RV function even in the absence of biochemical myocardial injury and is impaired early in mild forms of COVID‐19.55, 58 Additionally, it correlates with disease severity with more severe forms of COVID‐19 exhibiting lower values (less negative).55 Among patients with COVID‐19, the RVFWS is demonstrated to be more impaired in those with positive cardiac biomarkers, d‐DIMER and CRP compared to those with negative cardiac biomarkers, d‐DIMER and CRP.44, 55, 58 Further, it is shown to be a better surrogate of RV function compared with conventional RV indices, in patients with COVID‐19.

2.5.1. Left ventricular (LV) involvement

Studies have reported higher percentage of LV systolic and diastolic dysfunction (DD) among COVID‐19 patients compared with healthy volunteers, especially in those with elevated troponin levels compared with those normal troponin levels.50, 53, 54, 60 LV diastolic dysfunction was observed in 16%, and systolic dysfunction in 10% of COVID‐19 patients.46, 61

3. LV SYSTOLIC DYSFUNCTION

3.1. Wall motion abnormality (WMA)

WMA reporting has been variable among studies with incidence ranging from 14% to 26% among patients with COVID‐19 who underwent ECHO,50, 62 and has shown to correlate with biochemical injury of the myocardium.63, 64 WMA was more frequently observed in the mid and apical segments followed by basal segments.63, 64 EKG changes are common, but do not always exist in patients with WMAs. The most common EKG change was T wave inversion.46, 63 The most commonly adjudicated diagnosis was myocarditis and/or stress cardiomyopathy, followed by NSTEMI.63

3.2. Left ventricular strain pattern in COVID‐19

Impaired left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LVGLS) was observed frequently despite preserved or near preserved ejection fraction, and irrespective of previous cardiovascular disease, among patients with COVID‐19.62, 65 LVGLS was more frequently impaired in COVID‐19 patients with myocardial injury as compared with COVDI‐19 patients without myocardial injury and correlated with inflammatory markers and pulse oximeter, with the latter having the strongest correlation (p < 0.0001).62 LVGLS impairment was more pronounced in sub‐epicardium than sub‐endocardium layers.66 Although, LVGLS is more severely impaired in severe disease, it is impaired even in milder forms of the disease as compared with patients without COVID‐19.55, 66 A reverse Takotsubo pattern with impaired LVGLS predominantly in the basal segments of the LV, similar to that observed in Fabry's or Friedrich's disease, was reported but not duplicated in other reports.67, 68, 69 Impaired global circumferential strain (LVGCS) was also reported to be reduced in all LV layers (transmural) in one report where the authors speculated that this pattern is suggestive of myocarditis triggered by cytokine storm as opposed to direct viral cytotoxic effect.68

3.3. LV Diastolic Dysfunction (DD)

Doppler indicators of DD were frequently reported in COVID‐19 patients. However, their findings were heterogenous among studies. But DD seems to be more common than systolic dysfunction in patients with COVID‐19(16% vs 10%).46, 61

3.4. E/e′ ratio

In patients with COVID‐19, E/e′ which is reflective of LV filling pressures was not found to be elevated in patients with elevated HsT or other cardiac biomarkers.44, 46, 57 Further, E/e′ ratio was not significantly altered in the severe forms of COVID‐19 compared with mild form or between survivors and non survivors.44, 53, 55, 57, 70, 71 Of note, in a study of COVID‐19 patients that included 90% of patients on mechanical ventilation and 50% in prone position showed that E/e′ ratio was significantly higher in non‐survivors, and it was a predictor of mortality on univariate but not on multivariate analysis.52 However, two reports demonstrated that E/e′ ratio may be significantly higher in critically ill patients compared with healthy volunteers and milder forms of the disease.54, 70

3.5. E/A ratio

Among patients with COVID‐19, E/A ratio does not seem to be significantly different between mild and severe disease, or those with and without cardiac injury, nor among survivors and non‐survivors.44, 54, 55, 71

3.6. Mitral annular velocities

In a small study of 32 COVID‐19 patients, both septal and lateral e′ were significantly reduced in patients with myocardial injury as compared with no myocardial injury, however, the E/e′ was not different between both groups.70

3.6.1. Other findings

In addition, there have been multiple studies that have described diverse findings such as pericarditis, moderate to severe pericardial effusion causing cardiac tamponade and acute myocarditis causing global hypokinesia on ECHO in patients with COVID‐19.52, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78

3.6.2. Echocardiographic predictors of mortality in COVID‐19

As mentioned earlier, elevated PASP has found to be associated with a higher in‐hospital mortality.38 Studies have consistently shown RV dysfunction to be a predictor of disease severity. Mortality rate has found to be increased in patients with moderate/severe dilation of the RV as compared with patients with mild/no RV dilation.49 One study reported that RV dilatation correlates with high sensitivity troponins, and d‐Dimer levels.55, 79, 80 Of note, decreased RVGLS and RVFWS have been found to predict mortality independent of respiratory parameters, LV function or markers of multi‐organ failure.47, 79, 81 In addition, oxygen need, higher d‐Dimer and C‐reactive protein (CRP) correlated with lower RVGLS.47, 79, 81 In a study of 49 COVID‐19 patients with the majority on oxygen or non‐invasive ventilation, both RVFWS and RVGLS were significantly decreased in non‐survivors compared with survivors, with both having the highest area under curve (AUC) for predicting mortality as compared with other parameters.47 In another study, where seven patients were discharged and five needed intubation or died, both RVGLS and RVFWS were significantly lower in patients with poor outcomes compared with those with favorable outcomes.82 Also, lower RVFWS was an independent predictor of mortality in 100 COVID‐19 patients with 44 patients classified as severe disease.55 A cut‐off of ‐23% was found to have a sensitivity of 94% for predicting mortality among COVID‐19 patients in one study.79 In another study of 35 patients, those with RVGLS less than ‐20% had significantly higher 30 day mortality.83

RVFAC performed inconsistently in prediction of mortality in COVID‐19 patients. In one study that included COVID‐19 patients with varying severity, RVFAC was reported to be an independent predictor of mortality.71 In another study of 128 COVID‐19 patients with more than 50% of patients considered critical, low RVFAC, RV strain pattern, and 3D RV ejection fraction (EF) were independent predictors of mortality in their respective order with low 3D RVEF having the highest predictive value.70 However, in other studies among COVID‐19 patients RVFAC was not significantly different between survivors compared with non‐survivors.47, 55, 56

Finally, a study by D'Alto et al. demonstrated that right ventricular‐arterial uncoupling expressed as TAPSE/PASP is an independent predictor of mortality in COVID‐19 patients.29 With regards to LV parameters, mortality was found to be increased in patients who had reduced LV longitudinal strain (LS), left ventricular stroke volume index (LVSVi), cardiac index and tissue Doppler S’ (systolic wave) velocity.80 In addition, Giustino et al. demonstrated that the mortality rate in COVID‐19 patients with myocardial injury, defined as elevated cardiac biomarkers, was higher in patients with evidence of WMAs as compared with those without WMAs.64 Moreover, decreased LVGLS was found to be a strong predictor of mortality or poor outcomes.44, 82

3.6.3. Echocardiographic follow up after acute COVID‐19

LV and RV dysfunction, whether it is clinical or subclinical resolves in most patients post resolution of acute COVID‐19.44, 50, 57, 85 In a study by Churchill et al., a follow up ECHO was done in 11 patients after a median of 14 days post‐acute COVID‐19. The resolution of previously noted LV dysfunction and/or WMA was ascertained in 9/11 patients.50 In another study of 132 patients, follow up data at 3 months in 46 patients showed significantly improved RVFWS and LVGLS.44 This was further ascertained in another study that included 32 patients in whom both the LVGLS and RVFWS significantly improved on follow up ECHO, after a mean of 52 days, as compared with values obtained during hospitalization.57

However, a small proportion of patients would still show evidence of clinical and/or sub‐clinical echocardiographic sequalae of cardiac involvement. For instance, in a study of 125 survivors, with moderate pneumonia, who underwent follow up ECHO within 6–10 weeks, RV dilation was reported in 14%, isolated DD in 16% and 8.8% had both LV systolic and diastolic dysfunction, these correlated with elevation of CKMB during initial hospitalization.61 Also, in a study that included 28 patients with elevated troponin (myocardial injury) during hospital stay and 46 patients with no elevated troponin, 37.8% of the whole cohort with 57.1% of the myocardial injury group and 26.1% of the no myocardial injury group had impaired LVGLS defined as less than ‐18% after a mean follow up of 4 weeks, LVEF was preserved in both groups but significantly lower in the group with myocardial injury during hospitalization.86

Among patients with COVID 19, ECHO can be an important tool to diagnose and prognosticate patients regardless of their clinical severity. In patients with elevated inflammatory markers and/or elevated troponins seem to benefit from echocardiography examination after appropriate precautions are implemented. In patients with myocardial injury, RV dysfunction as evidenced by conventional ECHO parameters (such as RVEF, PASP, RV diameter, RVFAC, and TAPSE) is more common than LV systolic dysfunction and is likely the source of troponin. RV FWS is a more sensitive parameters for RV dysfunction, and correlates more consistently with worse outcomes than conventional ECHO parameters.

On the other hand, compared with RV dysfunction, LV dysfunction is less frequent presentation in patients with COVID‐19, in fact DD is relatively frequently compared with systolic dysfucntion. However DD, does not correlate with worse outcomes. LV WMA in the mid, apex, and base are frequently reported due to myocarditis, stress cardiomyopathy or true ischemic events and are more frequently seen in patients with myocardial injury with EKG changes. Moreover, LVGLS is impaired frequently in patients with COVID‐19 irrespective of systolic or diastolic dysfunction and is more affected in patients with severe disease with positive cardiac biomarkers and is an independent predictor of mortality.

Echocardiographic follow up is warranted in patients with newly impaired RV or LV dysfunction and/or WMA. These abnormalities seem to be transient and even subclinical involvement as evidenced by LVGLS and/or RVFWS resolves on follow up echo with no intervention.

4. LUNG ULTRASOUND FINDINGS IN COVID‐19

4.1. Technical considerations and most frequently studied protocol

The most commonly used protocol for performing lung ultrasound (LUS) in the reviewed studies was the 12 zone method. A complete lung examination consisting of 12 imaging regions, six on each side. Each hemi thorax is divided into anterior, lateral, and posterior zones which are separated by the anterior and posterior axillary line. Each zone is further divided into upper and lower halves, resulting in six areas of investigation. This also includes the BLUE “bed‐side lung ultrasound in emergency” protocol for LUS, which acquires images in a similar scanning fashion.87 The most commonly used transducers were convex (Curvilinear) probes, however, phased array and linear transducers were also used.

4.2. LUS findings

The most common LUS findings in screened studies and their relative prevalence were irregular pleural lines (27.9–89% in patients), pleural thickening (6.5–86%), separate “distinct or scattered” B‐lines (16.6–88%), confluent “coalescent” B‐lines with or without “white lung” (12–78.6%), pulmonary consolidations (31.1–77%), sub‐pleural consolidations (8.06–73%), and pleural effusions (3.8–56%)88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96 [Table 2]. Variability in prevalence of LUS findings is likely related to heterogeneity in the severity of the disease, as well as the timing of LUS in the course of the disease. For example, Mafort et al., studied symptomatic healthcare professionals who had a positive RT‐PCR test for COVID‐19. They detected coalescent B‐lines and subpleural consolidations in 36% and 8.06% of patients, respectively. Bilateral involvement was seen in only 50.1% of patients. Of note, they studied patients during their first assessment and those hospitalized or undergoing intensive care were not included.90

TABLE 2.

Lung ultrasound findings in COVID‐19

| Study | Design | N | COVID‐19 severity | B line n/N | Consolidations n/N | Sub‐pleural Lesions n/N | Micro Emboli n/N | Other | Sensitivity compared with other modality | Diagnostic Reference Standard | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y Lichter et al. | Retrospective study | 120 |

75‐ mild 31‐moderate 14‐severe |

NA | 93/120 | 100/120 | NA | Pleural effusion‐ 9 | LUS cutoff of 18 (Sensitivity = 62%, specificity = 74%) | N/A | Base‐line LUS score strongly correlates with the eventual need for invasive mechanical ventilation and is a strong predictor of mortality |

| S Ottaviani et al. | Prospective study | 21 | NA | 19 | 13 | NA | NA | Median B score 6, C score 1. | Correlation coefficient of (r = .935) between LUS and HRCT findings | HRCT (correlation of LUS findings with HRCT) | LUS excellent correlation with lung involvement in HRCT, positive correlation with supplemental oxygen therapy. |

| Rojatti M et al | Retrospective study | 41 | All ICU cases | NA | NA | NA | NA | Mean LUS score = 11. |

LUS and IL‐6 correlation(r = .52) LUS and oxygen correlation R = .3 |

LUS versus PaO2/FiO2 ratio and PaCO2 | LUS positively correlated with IL‐6 and co2 levels, inverse with oxygen levels, and no correlation with respiratory system compliance. |

| Zhao et al | Prospective study | 35 | seven refractory ARDS, 28 non‐refractory ARDS | B line score 4 in refractory, 6.5 in non‐refractory | Mean consolidation score of 1 in refractory versus 0 in non‐refractory | NA | NA | NA | LUS cutoff of 32 points for differentiating refractory disease with specificity of 89.4% and a sensitivity of 57% | N/A | LUS score helpful in differentiating refractory group versus non‐refractory with cut‐off of 32 |

| Bonadia N et al | Prospective | 41 | 16/41 patients in ICU. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | N/A | Patients who died had Lung score of 1.43 and discharged had score of 1, patients requiring ICU admission had median score of 1.36 compared to non‐requiring score of 1. |

| Zieleskiewicz L et al | Retrospective study | 100 | 23/100 | 96/100 | 32/100 | 6/100 | NA | NA | An LUS score > 23 predicted severe SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia diagnosed by chest CT scan with a Sp > 90% and a PPV of 70% | Chest CT | The LUS score was predictive of pneumonia severity as assessed by a chest CT scan and clinical features |

| Shumilov et al | 18 | NA | 17/18 | 14/18 | 16/18 | NA | NA | NA | chest X‐ray |

LUS was especially useful to detect interstitial syndrome compared to CXR in COVID‐19 patients (17/18 vs 11/18; p < 0.02). LUS also detected lung consolidations very effectively (14/18 for LUS vs 7/18 cases for CXR; p < 0.02). |

|

| Gaspardone et al. | Prospective study | 70 |

Group 1: mild (no ventilator support) 27 Group 2: severe (ventilator support) 43 |

LUS score: Anterior areas: mild 21% versus severe 36% (p = 0.21) Posterior areas: mild 48% versus severe 32% (p = 0.21) Other areas no statistically significant difference seen. |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | RT‐PCR | Classified as LUS |

| Youssef et al. | Prospective study | 75 |

PCR + (n = 3) 4% PCR –(n = 72) 96% |

NA | NA | NA | NA | Lung Ultrasound normal in all patients. |

Ultrasound Sensitive in symptomatic patients (no changes seen in pregnant asymptomatic patients) Not useful as a screening tool. |

RT‐PCR |

Pregnant women (median age 34, range, 24–48yrs) (median gestational age 38 weeks, range 25–40wks) Followed for median of 7 days (range 3–9 days) |

| Lu W et al. | Retrospective study | 30 |

Severe : (> 19 points) Moderate (8‐18 points) Mild (1‐7 points) |

27/30 (90%): B‐lines. [15/30: coalescent B‐lines 5/30 : widely spaced B‐lines (> 7 mm) 3/30 diffusely coalescent B‐lines] |

6/30 (20%) pulmonary consolidation | NA | NA |

3/30 (10%) pleural thickening, 1/30 (3.3%) minimal pleural effusion 1/30(3.3%): pneumothorax. |

NA | CT chest |

Distribution: 22/30 (73.3%): multiple distributions, 5/30 (16.7%): Focal distribution. 22/30(73.3%) bilateral involvement 5/30(1.6%) unilateral involvement Majority distribution: Sub‐pleural and peripheral zones, with the lower & dorsal regions. |

| Nouvenne A, et al. | Prospective study | 26 | Stable patients as critically ill patients and requiring ICU were excluded |

Distinct B line 7 (27). Confluent B lines 17 (37). |

Parenchymal consolidation 13 (50) | Sub‐pleural consolidation 17(73). |

Bilateral involve 26(100). LUS 15+_5 |

NA | HRCT | LUS score was significantly correlated with CT visual scoring (r = .65, p < 0.001) and oxygen saturation in room air (r = –.66, p < 0.001). | |

| Yasukawa K, et al. | Retrospective study | 10 | Mild to moderate cases. None required ventilator |

Glass rocket 10(10) Septal rocket 2(10) |

1(10) | 5(10) |

Birolleau Variant 5(10) |

NA | N/A | LUS is more sensitive than CXR in detection of interstitial findings. | |

| Li S et al | Retrospective study | 91 | Severe and critical |

59/91 had scattered B lines 56/91 Confluent B lines |

48/91 |

6/91 pleural thickening 39/91 had pleural effusion |

NA | 20/91 had pneumothorax | Not compared to other tests | N/A | Findings support the use of LUS for monitoring response to therapy in sever and critical COVID‐19 |

| Pare et al | Retrospective cohort study | 43 (27 positive Covid‐19) | Not Specified |

All patients were tested for B lines 24/27 |

10/27 | 21/27 | NA | NA |

Compared to CXR, LUS sensitivity: (88.9%, 95% confidence interval (CI), 71.1‐97.0) CXR sensitivity: (51.9%, 95% CI, 34.0‐69.3; p = 0.013). LUS specificity: 56.3% (95% CI, 33.2–76.9) CXR specificity: 75.0% (95% CI, 50.0–90.3 |

RT‐PCR and CXR |

LUS was statistically significant Higher sensitivity: p = 0.013 Lower Specificity: p = 0.453 LUS considered positive if have B‐lines |

| Mafort et al | Cross‐sectional study | 409 | All symptomatic without mentioning the severity | 297/409 (72.6%) of participants had B‐lines > 2, 148/409 (36.2%) had coalescent B‐lines | 33/409 (8.06%) | NA | NA | NA | Ultrasound has a sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 94%, respectively, for the identification of parenchymal consolidation | RT‐PCR |

The aeration score differed significantly regarding the presence of cough (p = 0.002), fever (p = 0.001), and dyspnea (p < 0.0001). The finding of sub‐pleural consolidations in the LUS showed significant differences between participants with or without dyspnea (p < 0.0001) |

|

B‐lines are the most common ultrasound sign, sub‐pleural consolidations are those that most impact the respiratory condition |

|||||||||||

| Narinx et al. | Retrospective study | 93 | Not specified | Did not detail LUS findings. | Did not detail LUS findings. | Did not detail LUS findings. | Did not detail LUS findings. | NA | Compared with RT‐PCR, POCUS lung demonstrated outstanding sensitivity and NPV (93.3% and 94.1% respectively) while showing poor values for specificity, PPV, and accuracy (21.3%, 19.2%, and 33.3% respectively). | RT‐PCR | NA |

| Smargiassi A et al. | Prospective study | 38 | 19 in hospital and 19 isolated at home. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Chest CT (Plain CT chest, CTPA and HRCT) | NA |

| Alharthy A et al. | Prospective study | 89 | Severe |

Separated B‐lines 67.4% Confluent B‐lines 78.6% |

Consolidations 61.7% Lung parenchymal hepatization pattern (22.4%). A “starry sky” pattern of consolidation (bright infiltrates) 49.4% |

Sub‐pleural consolidations (26.9%) | NA |

Pleural line irregularities in > 6 lung areas 78.6% Pleural effusions 22.4% Small pneumothoraxes 3.37% Pericardial effusions 13.4% DVT 16.8% |

Did not compare to other imaging modalities | RT‐PCR | NA |

| Castelao J et al. | Prospective | 63 | severe ARDS due to active COVID‐19 infection |

B7 pattern in 203 (26.8%). B‐lines ≥7 mm apart B3 pattern in 143 (19%). B‐lines, 3 mm or less apart. |

C pattern in 159 (21%). Anterior alveolar consolidation(s). | NA | NA | A small unilateral pleural effusion was observed in 3 patients (4.8%). | Did not compare to other imaging modalities | RT‐PCR | NA |

| Fonsi GB et al | Prospective study | 63 patients (44 COVID positive) | 46 (73%) patients had moderate and 17 (27%) had severe symptoms. |

≤2 nonconfluent or confluent 20% ≥3 nonconfluent or confluent 80% |

Consolidation 45% | NA | NA |

Air bronchogram 39% Pleural effusion 18% Pericardial effusion 0% Thickened pleural line 86% |

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of LUS for COVID‐19 pneumonia were 68%, 79%, 88%, and 52%, respectively. Whereas for chest CT they were 93%, 90%, 85%, and 95%, respectively. |

RT‐PCR Chest CT |

NA |

| Bar S et al. | Prospective study | 100 adults of whom 31 had a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 RT‐PCR | ARDS n = 9 (29%), Admission to ICU n = 8 (26%), Death n = 6 (19%) |

Upper and lower anterior: Confluent B‐lines n = 3 (10%) Posterolateral: Confluent B‐lines n = 10 (32%) |

Upper and lower anterior N = 17 (54%) Posterolateral: n = 18 (58%) |

NA | NA |

Upper and lower anterior: Thickened pleural line n = 24 (77%) Posterolateral: Thickened pleural line n = 24 (77%) |

NA | RT‐PCR | NA |

| Dargent A et al. | Prospective study | 10 | 10 consecutive patients admitted in our ICU with moderate to severe ARDS | Monitored LUS score over ICU course | Did not compare to other imaging modalities | NA | NA | NA | NA | RT‐PCR | NA |

| Pivetta E et al. | Prospective study | 228 | Variable degree of severity. Ranging from mild disease discharged home, to patient admitted to ICU. | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Higher sensitivity and NPV for an integrated approach combining clinical and Lung Ultrasound findings when compared to a negative initial RT‐PCR result | RT‐PCR | |

| Calvo‐Cebrián A et al. | Prospective study | 61 | Moderate symptoms |

Coalescent B‐lines 54.1% Multiple separated B‐lines 45.9% |

Consolidation 31.1% | Not specified | Not specified |

Irregular pleural line 27.9% Mild pleural effusion 6.6% Location of LUS findings: Bilateral 65.6%. Multifocal unilateral 6.6%. Unifocal 18%. |

There was a significant association between the proposed LUS severity scale and the CXR severity scale: the higher the grade of US involvement, the higher the grade of radiologic involvement. | dichotomous variable that determined whether the hospital referral was “appropriate” | NA |

| Yassa M et al. | Prospective study | 8 | Mild, moderate and Critical. | NA | NA | NA | NA | Chest radiographic findings were negative and were not consistent with the LUS findings, chest CT showed similar findings as and was consistent with the LUS. | RT‐PCR | NA |

Abbreviations: ARDS, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; COVID‐19, Coronavirus‐2019; CTPA, Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram; CXR, Chest X‐Ray; HRCT, High resolution computed tomography; LUS, Lung ultrasound score; NPV, Negative Predictive Value; POCUS, Point of care ultrasound; PPV, Positive Predictive Value; RT‐PCR, Real time Polymerase Chain reaction.

With regards to the distribution of lung involvement reported in LUS, bilateral distribution was noted in 50.1 to 100% of cases. A greater tendency to involve the posterior and lateral regions with less involvement of the anterior region was demonstrated by Smargiassi A et al.97 Using a specific scoring system ranging from 0 to 3 (worst score, 3), they were able to demonstrate a higher prevalence of score 3 in posterior and lateral regions, and a higher prevalence of score 0 in the anterior regions in a population of non‐critically ill patients. A more prominent involvement of the posterior and lower regions was also noted by Castelao J et al. in 95.5% and 73.8% of studied patients, respectively.98 Similar predilection for posterior and lower region involvement was described by Lu W et al, who also noted a subpleural and peripheral pulmonary zones distribution of LUS findings.92 Interestingly, a more prominent involvement of the anterior areas of the lungs was noted in patients with severe disease relative to those with mild disease (36% vs 21% of patients, p .021),99 and clinical deterioration was associated with loss of aeriation in anterior lung segments.100 Higher prevalence of bilateral involvement and anterior areas involvement in severe disease seems to be a recurring finding among the reviewed studies. Alharthy A et al.studied 89 intensive care unit (ICU) patients with confirmed COVID‐19, of which 84.2% were intubated and 15.7% required High Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC). Bilateral and anterior areas involvement was evident in in 78.6% of patients. The findings of confluent B‐lines originating from irregular pleural lines was found in 69.6% of cases and suggested an advanced disease.101

4.2.1. Diagnostic performance of LUS

LUS demonstrated remarkable sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) among reviewed studies, with sensitivity ranging from 68% to 93.3% and a NPV ranging from 52% to 94.1%,92, 94, 96, 102 suggesting the utility of LUS as a screening test to rule out COVID‐19 lung infection. . Pivetta E et al. have even demonstrated higher sensitivity and NPV for an integrated approach combining clinical and LUS findings when compared to a negative initial RT‐PCR result (94.4% vs 80.4% for sensitivity and 95% vs 85.2% for NPV, respectively).103 In this study, an integrated assessment based on clinical features and LUS findings was able to identify 21 false negative RT‐PCR results that tested positive on a subsequent test performed after 72 hours. Data regarding specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and diagnostic accuracy has been conflicting, with some studies demonstrating values as low as 21.3%, 19.2%, and 33.3% for specificity, PPV and diagnostic accuracy, respectively,102 while others demonstrating higher values up to 92.9%, 84.6%, and 93.3% for specificity, PPV and diagnostic accuracy, respectively.92 Lu W et al. demonstrated higher sensitivity and NPV of LUS in patients with moderate disease (77.8% and 88.9%, respectively) with both values reaching 100% in patients with severe disease. Overall, LUS showed a higher efficacy in assessing patients with no and severe lung lesions, with diagnostic accuracy for patients with no, mild, moderate, and severe lung lesions of 93.3%, 76.7%, 76.7%, and 93.3%, respectively.92 Bar S et al. suggested four ultrasound signs that were independently associated with a positive COVID‐19 RT‐PCR; upper sites B lines ≥ 3 [OR 1.52 (1.31‐‐1.79]), lower sites thickened pleura [OR 1.73 (1.49‐‐1.98)], lower sites consolidation [OR 2.39 (2.07‐‐2.69)], and postero‐lateral sites thickened pleura [OR 1.97 (1.72‐‐2.22)],104 suggesting a role for LUS in triaging patients with suspected COVID‐19 lung infection.

4.2.2. Comparison to other imaging modalities

A chest computed tomography (CT) scan is considered as the gold standard for the diagnosis of COVID‐19 pneumonia, having a sensitivity greater than RT‐PCR.105 Zieleskiewicz L et al. demonstrated a significant association between LUS score and chest CT severity. A LUS score > 23 predicted severe SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia (specificity > 90% and a PPV of 70%) and a score < 13 excluded severe SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia (sensitivity > 90% and an NPV of 92%) diagnosed by chest CT scan.106 Similarly, Ottaviani et al. observed 21 non‐ICU patients, noting the extent of affected lung using LUS score for B lines, (wherein each lung is divided into six segments delineated by anterior, posterior axillary lines, parasternal, and paravertebral lines), as well as the presence of ultrasound consolidations had an excellent correlation with the percentage of lung involvement on chest high resolution (HR)CT (r = .935, p < 0.001 and r = .452, p = 0.04, respectively).107 A significant positive correlation of LUS score with CT visual score (r = .65, p < 0.001) was also described in a study by Nouvenne A et al.89 These data suggest a promising role for LUS as an alternative to CT scan for screening patients with suspicion of COVID‐19, as well as assessing the severity of the disease. Shumilov et al. compared LUS findings to chest X ray (CXR) in 18 symptomatic COVID‐19 patients and found LUS was useful in detecting interstitial syndrome compared with CXR (94% “B‐lines” vs 61% “hazy increased opacity”; p < 0.02) as well as detecting lung consolidations effectively (77% for LUS vs 38.8% for CXR; p < 0.02).91 Similar findings were described by Pare JR et al., wherein LUS was more sensitive than CXR (88.9% vs 51.9%, respectively) for the association of pulmonary findings of COVID‐19 (p = 0.013).

4.2.3. Prognostic implications and utility of LUS scoring

Y Lichter et al., found the presence of pleural effusion, pleural thickening, and a high total LUS score at baseline examination were significantly associated with increased mortality. Greater involvement of the anterior segments was a main contributor to the worsening LUS score. The unadjusted hazard ratio of death for patients with LUS score > 18 was 2.65 [1.14–6.3], p = 0.02, suggesting a 2.6‐fold increase in mortality in those patients.100 Extent of lung involvement on LUS was predictive of the need for intensive care unit admission as noted by Bonadia N et al, patients admitted to ICU had a median 93% of areas involved versus 20% of areas involved in patients who did not require ICU admission.108 In a study by Zhao L et al., a LUS score cutoff point of more than 32 was found to predict refractory disease (defined as respiratory failure with a PaO2/FiO2 of ≤100 mm Hg or patients who were treated with ECMO) with a specificity of 89.3% and a sensitivity of 57.1%.109 Description of LUS scores in individual studies is provided in Table S2. Castelao J et al., used a self‐designed scoring system to evaluate severity of lung involvement. The total lung score showed a strong correlation (r = −.765) with the oxygen pressure–to–fraction of inspired oxygen ratio, and the anterior region lung score was significant (OR, 2.159; 95% confidence interval, 1.309–3.561) for the risk of requiring noninvasive respiratory support (NIRS).98 LUS score correlated with IL‐6 concentrations (r = .52, p = 0.001) and arterial pCO2 (r = .30, p = 0.033) and was inversely correlated with oxygenation (r = − .34, p = 0.001) in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID‐19.110

4.2.4. Potential implications for management

Usefulness of point‐of‐care ultrasound in the primary care setting has been evaluated in previous studies,111, 112 and Calvo‐Cebrián A et al. aimed to evaluate its utility in influencing decisions about patients with clinical suspicion of COVID‐19. A self‐designed LUS severity scale and the individual finding of coalescent B‐lines was found to be significantly associated with the main outcome of appropriate hospital referral (p = 0.008; OR, 4.5; 95% CI, 1.42–14.27) and a higher rate of hospital admission (p = 0.02; OR, 4.76; 95% CI, 1.18–19.15).95 Another utility of LUS was demonstrated by Dargent A et al., who monitored the evolution of COVID‐19 pneumonia in 10 patients admitted to the ICU, and observed a lower LUS score in all patients on the day of extubation compared with admission, suggesting an accurate reflection of disease progression.113 Gaspardone et al. observed LUS findings in the post‐acute phase of COVID‐19, noting residual lung alterations on the LUS and a higher LUS score at the time of discharge in patients who had more severe disease during the acute phase compared with patients with milder disease.99

4.2.5. Utility in pregnant women

LUS is a potential alternative to CT scan in pregnant women, given the lack of radiation and option for short interval repeat testing associated with the procedure. Given obstetricians/gynecologists use ultrasound in their routine examinations, the systematic utilization of this practice to expand to LUS evaluation has previously been proposed.114 Usefulness of LUS in assessing lung involvement in pregnant women with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 infection has been explored in several studies.115, 116, 117 The addition of LUS scoring to symptoms and exposure history in pregnant women had significant impact on the prediction of a positive RT‐PCR result, increasing the positive predictive value of the model from 77.1% (95% CI, 67.0–84.8%) to 93.7% (95% CI, 83.7–97.8%).116 In a series of eight pregnant women with a positive COVID‐19 RT‐PCR, who underwent point‐of‐care LUS examinations after routine obstetric ultrasound, Yassa M et al. was able to detect serious lung involvement in seven patients, significantly influencing their management and providing an alternative imaging modality in two patients not willing to undergo a CT chest.117

LUS has many advantages when evaluating patients in the setting of suspected or proven COVID‐19 pneumonia. It is a widely available tool that can be readily used at the bedside to provide a rapid point of care assessment of the lungs, an advantage that is becoming more and more prominent with the rising use of pocket ultrasound devices. Further, cardiac sonographers can be trained to use LUS and be able to provide more clinically relevant information at bed side and with a short learning curve. The available literature suggests remarkable sensitivity and NPV for lung involvement in COVID‐19, when compared with RT‐PCR, proposing LUS as a useful screening tool to rule out COVID‐19 lung infection at the bedside. The use of LUS scoring systems seems to provide robust prognostic data as well, in terms of illness severity, need for ICU admission, and mortality. On the other hand, several limitations exist when using LUS. Although, most of the available studies have used a standard 12‐zone scanning technique for LUS, the data is lacking when it comes to identifying which technique provides the most reliable findings, and consequently, the highest sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy. The lack of a unified or a standardized LUS scoring system presents a challenge and further research is needed to identify the optimum scoring system to be used for prognostic implications. Although, the use of LUS offers several advantages, further research is needed to evaluate if the routine use of LUS in this setting would have an implication on patient outcomes, an area in which we find that the available literature comes in short.

4.2.6. MRI findings in COVID

Nine studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria.118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126 One study included patients in the acute stage and remaining five studies included patients post recovery.120 Three studies had control groups comparators.118, 122, 123 Patients underwent MRI because of biochemical evidence of myocardial injury as evidenced by elevated high sensitivity troponin118, 120 or because of cardiac symptoms120, 121 while other studies performed screening MRI to identify high risk athletes in competitive sports who tested positive for COVID‐19 regardless of symptoms.119, 122, 124, 125, 126 Of note, in one study, none of the patients had elevated cardiac troponins.119 The study characteristics are fully described in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Cardiac magnetic resonance findings in COVID‐19

| Study, year | Study design | Number of study participants | MRI device | Covid severity | LV | RV | LGE(n) | AHA segments (segment number (n)) | ECV (extracellular volume)%) | T1 mapping | T2 Mapping | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. (2021) | Prospective | 47 Consecutive patients who tested positive for COVID‐19 and discharged were recruited versus 31 healthy controls | 3T CMR scanner (Ingenia CX, Philips Healthcare, Best, Te Netherlands). |

72.7% had moderate disease and 27.3% moderate and critical disease, all patients were hospitalized. Of note all but one patients had normal EKGs |

Only CMR derived 3 D global circumferential strain (GCS) was significantly different between LGE+ve and Controls and LGE ‐ve | RV peak 3D Global longitudinal strain was significantly reduced in LGE +ve as compared to controls and LGE ‐ve | 13 | Most were located inferior and infero‐lateral segments at base and mid‐ segments. | NA | T1 mapping was not significantly different between LGE+ve and LGE ‐ve (p > 0.05) | NA | LGE was most commonly in infero and infero lateral and was subqpicardial. walls and it is irrespective of EKG changes in moderate to severe COVID‐19 after recovery, serum troponin was significantly elevated in LGE +ve patients during hospital stay |

| Clark et al. (2020) | Retrospective | 22 | 1.5 Tesla Siemens Avanto Fit (Siemens Healthcare Sector, Erlangen, Germany) | Asymptomatic (5), Mild (17) | Covid‐19 postive athletes versus Healthy controls versus Tactical athletic controls: LVEF (%, IQR)* 60% [59,63] versus 60 [57, 64] versus 61 [57, 64] p = 0.8, LVEDV (ml) 180 [153,208] versus 166 [143, 211] versus 188 [157, 207] p = 0.83, LVEDVi (ml/m2) 94 [89, 102] versus 95 [79, 100] versus 84 [73, 98] p = 0.02. LV mass (g) 115 [101,151] versus 76 [63, 96] (p < 0.001) versus 140 [120, 155] p = 0.11 . | Covid‐19 postive athletes versus Healthy controls versus Tactical athletic controls: RVEF (%) 52 [IQR: 50, 54] versus 57 [IQR: 55, 60] (p < 0.001) versus 56 [IQR: 51, 59] p = 0.01, RVEDVi (ml/m2) 105 [IQR: 97, 114] versus 95 [IQR: 80, 106] versus 88 [IQR: 76, 106] p = 0.01, RVESVi (ml/m2) 50 [IQR: 46, 55] versus 40 [IQR: 33, 45] (p < 0.001) versus 43 [IQR: 31, 51] p < 0.01 | 2 | Myocardial (2), Pericardial (1), Any (2) | Covid‐19 positive athletes versus healthy controls versus tactial athletic controls (% ± SD) Mid septum 25.3 ± 2.6 versus 24 ± 3 versus 22.5 ± 2.6 p < 0.001, Covid‐19 positive athletes (%) Basal septum 24 (22.7,25.9), Basal lateral 21.6 (20.6,23.8),mid lateral 23.3 (21.4,25). Covid‐19 positive athletes with myocardial pathology versus Covid‐19 positive athletes without myocardial | T1 Covid‐19 positive athletes versus Healthy controls versus Tactical athletic controls (ms)* Basal septum 995(969,1006) versus 986 (971, 999) versus 990 (964, 1024) p = 0.89, Basal lateral 971(951,984) versus 958 (945, 983) versus 975 (962, 1011) p = 0.17, Mid septum 982(973,997) versus 978 (963, 998) versus 989 (963, 1008) p = 0.22, mid lateral 980 (947,988) | T2 Covid‐19 positive athletes versus Healthy controls: Basal septum 44.3(42.3,46.1) versus 42.4 (41.5, 43.3) p = 0.009, Basal lateral 45.4 (43.2,46.6) versus 44.0 (43.0, 44.6) p = 0.034, Mid septum 46.4(45.2,48.2) versus 44.6 (43.2, 45.4) p = 0.004, mid lateral 47.0 (45.2,48.2) versus 44.0 (42.6, 45.4) p = 0.003. T2 Covid‐19 positive athletes | Cardiac inflammation or fibrosis following Covid‐19 infection can be missed by EKG or strain echo alone and CMR may have a role in diagnosing cardiac pathology post Covid‐19 infection |

| pathology (%) 24.3 (22.5, 26) versus 24.0 (22.9, 25.8) p = 0.95. | versus 965 (946, 975) versus 968 (944, 1000) p = 0.93 . T1 in those with Covid‐19 and myocardial pathology versus without myocardial pathology basal septum 997 (988,1007) versus 995 (968,1005) (p = 0.65), T1 Covid‐19 positive athletes with myocardial pathology versus Covid‐19 positive athletes without myocardial pathology (ms): Basal Septum 997 (988, 1007) versus 995 (968, 1005) p = 0.65, | with myocardial pathology versus Covid‐19 positive athletes without myocardial pathology (ms): Basal Septum 44.3 (44,44.6) versus 44.3 (42.3,46.7) p = 0.95 | ||||||||||

| Esposito et al. (2020) | Retrospective | 10 | 1.5‐T in nine patients and 3‐T in one patient | NA | EF > 55%(5), EF 40–55%(3), EF < 40% (2) | NA | 3 | A few thin and shadowed subepicardial striae of LGE were detectable in the lateral wall, accounting for 1%, 3%, and 3% of LV mass respectively | Calculated for wot patients: 30, 36 | Increased myocardial‐to‐skeletal muscle intensity ratio on STIR images increased native‐T1 mapping (at 1.5‐T: median 1,156 ms [IQR: 1,123 to 1,198 ms]; normal value < 1,045 ms; at 3‐T: 1,378 ms; | T2 mapping (ms)*: 62 [IQR: 59 to 67] (normal value < 50), T2‐ratio*: 2.3 [IQR: 2.2 to 2.4] (normal value < 1.9) | This study found that CMR may be more reliable than LGE in detecting myocardial injury in their patient cohort. |

| normal value < 1,240 ms) and increased T2 mapping (median 62 ms [IQR: 59 to 67 ms]; normal value < 50 ms) | ||||||||||||

| Huang et al. (2020) | Restrospective | 26 | 3‐T MR scanner (Skyra, Siemens, Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) | Moderate (22), Severe (4) | LVEF Patients with positive conventional CMR findings versus negative conventional CMR findings versus Controls (%) 60.7 ± 6.4 versus 64.3 ± 5.8 versus 63.0 ± 8.9 (p = 0.4) | RVEF Patients with positive conventional CMR findings versus negative conventional CMR findings versus Controls (%) 36.5 ± 6.1 versus 41.1 ± 8.6 versus 46.1 ± 12.0 (p = 0.01) | 8 | 2(2), 3(1), 4(3), 5(1), 8(1), 9(1), 10(3), 11(2), fS12(1) | ECV in patients with positive conventional CMR findings versus patients without positive findings versus controls (%) 28.2 [IQR: 24.8 to 36.2] versusversus 24.8 [IQR: 23.1 to 25.4] versusversus 23.7 [IQR: 22.2 to 25.2] p = 0.002 | Global T1: patients with positive conventional CMR findings versus patients without positive findings versus controls (ms, IQR) 1,271 [1,243 to 1,298] versusversus 1,237 [1,216 to 1,262] versusversus 1,224 [1,217 to 1,245], p = 0.002. | Global T2: patients with positive conventional CMR findings versus patients without positive findings versus controls (ms) 42.7 ± 3.1 versusversus 38.1 ± 2.4 versus 39.1 ± 3.1, p < 0.001 | In this cohort of patients who complained of cardiac symptoms after recovering from Covid‐19 infection, 58% had positive CMR findings indicative of cardiac edema, fibrosis, or impaired ventricular function. Those with positive conventional CMR findings were noted to have decreased right ventricular function. |

| Puntmann et al. (2020) | Prospective observational | 100 | 3‐T scanners (Magnetom Skyra; Siemens Healthineers) | Recovered at home (n = 67) asymptomatic (n = 18), minor‐moderate symptoms (n = 49), severe/requiring hospitalization (33), | LVEF (%) Covid 57, Control 60, RF matched control 62 (p < 0.001). LVEDV Index (ml/m2) Covid 86, Control 80, RF matched control 76 (p < 0.001). LV mass index (g/m2) Covid 48, Control 51, RF matched control | RVEF (%): Covid 54, Control 60, RF matched control 59 (p < 0.001) | 74 | Covid versus Controls versus RF matched controls: Myocardial (32 vs 0 vs 9, p < 0.001), Non‐ischemic (20 vs 0 vs 4, | NA | Native T1: Covid versus Controls versus RF matched controls (1125 vs 1082 vs 1111, p < 0.001)*, Abnormal Native T1: Covid versus Controls versus RF matched controls (%) (73 vs 12 vs 58, p < 0.001), | Native T2: Covid versus Controls versus RF matched controls (38.2 vs 35.7 vs 36.4, p < 0.001), Abnormal Native T2: Covid versus Controls versus RF matched controls (%) (60 vs 12 vs 26, p < 0.001), | CMR shows cardiac involvement in a significant number of patients regardless of pre‐existing medical conditions. |

| Mechanical ventilation (2), non‐invasive ventilation (17) | 53 (p = 0.005) | p < 0.001), Epicardial (22 vs 0 vs 8, p < 0.001) | Significantly abnormal native T1: Covid versus Controls vs RF matched controls (%) (40 vs 0 vs 12, p < 0.001) | Significantly abnormal native T2: Covid versus Controls versus RF matched controls (%) (60 vs 12 vs 26, p < 0.001), Significantly abnormal native T2: Covid versus Controls versus RF matched controls (%) (22 versus 0 , p < 0.001) | ||||||||

| Rajpal et al. (2020) | Restrospective | 26 | 1.5‐T scanner (Magnetom Sola; Siemens Healthineers) | Recovered at home none needed hospitalizations | LVEF 57.730% (avg) | RVEF 56.884% (avg) | 12 | 2(1), 3(4), 5(1), 6(1), 8(5), 9(8), 12(3) | 24.7 (avg) | T1‐978.8 (normal range < 999 ms) | T2‐52.4 (normal range < 53 ms) (Average AHA segments 8.4) | CMR allowed observation of myocarditis and previous myocardial injury associated with Covid‐19 infection. |

| Starekova et al. (2021) |