Abstract

Background

The long‐term sequalae of COVID‐19 remain poorly characterized. We assessed persistent symptoms in previously hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 and assessed potential risk factors.

Methods

Data were collected from patients discharged from 4 hospitals in Moscow, Russia between 8 April and 10 July 2020. Participants were interviewed via telephone using an ISARIC Long‐term Follow‐up Study questionnaire.

Results

2,649 of 4755 (56%) discharged patients were successfully evaluated, at median 218 (IQR 200, 236) days post‐discharge. COVID‐19 diagnosis was clinical in 1291 and molecular in 1358. Most cases were mild, but 902 (34%) required supplemental oxygen and 68 (2.6%) needed ventilatory support. Median age was 56 years (IQR 46, 66) and 1,353 (51.1%) were women. Persistent symptoms were reported by 1247 (47.1%) participants, with fatigue (21.2%), shortness of breath (14.5%) and forgetfulness (9.1%) the most common symptoms and chronic fatigue (25%) and respiratory (17.2%) the most common symptom categories. Female sex was associated with any persistent symptom category OR 1.83 (95% CI 1.55 to 2.17) with association being strongest for dermatological (3.26, 2.36 to 4.57) symptoms. Asthma and chronic pulmonary disease were not associated with persistent symptoms overall, but asthma was associated with neurological (1.95, 1.25 to 2.98) and mood and behavioural changes (2.02, 1.24 to 3.18), and chronic pulmonary disease was associated with chronic fatigue (1.68, 1.21 to 2.32).

Conclusions

Almost half of adults admitted to hospital due to COVID‐19 reported persistent symptoms 6 to 8 months after discharge. Fatigue and respiratory symptoms were most common, and female sex was associated with persistent symptoms.

Keywords: asthma, COVID‐19, long COVID, PASC, postacute sequelae SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, post‐COVID Condition, post‐COVID Syndrome, risk factors

Word cloud showing persistent symptoms 6–8 months since hospital discharge in people previously hospitalised with COVID‐19.

KEY MESSAGES.

6–8 months after hospital discharge, around a half of patients with Covid‐19 experienced persistent symptoms

Chronic fatigue and respiratory problems were the commonest persistent symptoms, with 11.3% having multisystem involvement

Female sex was associated with higher risk of persistent symptoms

1. INTRODUCTION

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) has placed a significant burden on health services and society worldwide. There have now been well over 100 million coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) cases reported with a mortality rate of around 2.2%globally.1 The acute presentation of COVID‐19 has now been well investigated, with fever, cough, shortness of breath and anosmia among the most commonly reported symptoms.2, 3, 4

It has become evident that a substantial proportion of people experience ongoing symptoms including fatigue and muscle weakness, joint and muscle pain, and breathlessness, months after the acute phase of COVID‐19.5, 6, 7 This phenomenon is now commonly referred to as Long COVID but has also been described as post‐COVID syndrome, Post‐Acute Sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (PASC), the post‐COVID‐19 condition8 or patients have been labelled COVID long‐haulers.9, 10 There is still a paucity of long‐term follow‐up data, which means we have limited knowledge of the full range of symptoms, duration of disease and potential risk factors. Recently published data from China describing long‐term consequences of COVID‐19 show that 76% of previously hospitalized adult patients have at least one symptom 6 months after acute infection.6 In a UK registry study of 47,780 previously hospitalized adults, 29.4% were readmitted and 12.3% died after initial discharge with multi‐organ dysfunction.11

There is an urgent need for accurate long‐term follow‐up of COVID‐19 patients,7 to inform future management plans and address the devastating impacts of this condition on the quality of life (QoL) of people affected. This observational cohort study aimed to investigate the incidence of long‐term consequences in adults previously hospitalized for COVID‐19 and to assess risk factors for Long COVID in Moscow, Russia. We used the standardized follow‐up data collection protocol of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC).

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design, setting and participants

This is a longitudinal cohort study of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 infection admitted to Sechenov University Hospital Network (four tertiary hospitals) in Moscow, Russia. We collected the follow‐up data between 2 December 2020 and 14 January 2021 from patients discharged between 8 April 2020 and July, 2020. We included adult patients (≥18 years of age), with either reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and clinically confirmed infection, when the laboratory testing result is negative, inconclusive or unavailable.

The acute phase data, including comorbidities and disease severity, were extracted from electronic medical records (EMR) and the Local Health Information System (HIS) at the host institution using the modified and translated ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation protocol (CCP).12 Details of the acute phase data collection are described elsewhere.3 The study was approved by the Sechenov University Local Ethics Committee on 22 April 2020 (protocol number 08–20). A protocol amendment enabling serial follow‐up of the cohort was approved on 13 November 2020.

Information about the current condition and persistent symptoms was collected by telephone using the Tier 1 ISARIC Long‐term Follow‐up Study case report form (CRF) developed by the ISARIC Global COVID‐19 follow‐up working group, translated into Russian assessing the patients’ physical and mental health9 (Supplementary material). Additional information was added from the WHO CRF for Post COVID conditions.13 The participants were asked to report on dyspnoea, QoL and difficulties in functioning before the COVID‐19 illness and at the time of the interview. We used the British Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale, the EuroQoL five‐dimension five‐level (EQ‐5D‐5L) questionnaire, the EuroQoL Visual Analogue Scale (EQ‐VAS) asking participants to score their QoL from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health), UNICEF/Washington disability score and World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). The study was registered with EuroQoL as part of the ISARIC collaborative effort (EuroQoL ID 37035).

Data collection and entry were performed by a team of medical students who underwent training in basic data entry into REDCap and telephone interviews. Students have already had extensive data extraction experience gained from the previous research3 and were supervised by senior academic staff members.

The research team members attempted to contact patients three times before declaring them lost to follow up. If available by telephone, the patients were asked to provide their verbal consent to the interview.

2.2. Data management

We used REDCap electronic data capture tools (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA) hosted at Sechenov University and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp) for data collection, storage and management.11, 12 The baseline characteristics, including demographics, symptoms on admission and comorbidities, had been extracted from EMRs and entered into REDCap previously.

2.3. Definitions

The acute disease severity was stratified in accordance with Arnold et al.10 by a three‐category scale based on the degree of required supportive care during hospital stay: mild (no supplementary oxygen or intensive care), moderate (supplementary oxygen during hospitalization) and severe (need for non‐invasive respiratory modalities (NIV), invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and/or admission to intensive care unit (ICU)). A difference of 10 points at EQ‐VAS defined relevant change in the health status.4

All comorbidities were reported by the patients and/or family members at the time of the hospital admission and subsequently double checked during the follow‐up telephone interview.

For the purpose of this study, we defined “persistent symptoms” (PS) as symptoms present since hospital discharge only.

PS present at the time of follow‐up were categorized into respiratory, gastrointestinal, dermatological, chronic fatigue, neurological, mood and behaviour, sensory (Table S1). Symptom categorization was based on previously published literature14, 15 and international expert group discussions.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for baseline characteristics. Continuous variables were summarized as median (with interquartile range) and categorical variables as frequency (percentage). The chi‐squared test or Fisher's exact test was used for testing differences in proportions between groups. The Wilcoxon rank‐sum test was used for testing the hypotheses about differences in means between the groups.

We performed multivariable logistic regression to investigate associations of demographic characteristics, comorbidities and severity of acute phase COVID‐19 with PS categories presence at the time of the follow‐up interview. To enhance the robustness of the effect estimates, only comorbidities that were present in at least 3% of the cohort were included in the modelling. Primary analysis was performed using the full data set, whereas sensitivity analysis included only a subset of people with RT‐PCR confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (ICD U07.1). We have previously found no significant differences in clinical signs, symptoms, laboratory test results and risk factors for in‐hospital mortality between clinically diagnosed patients and patients with positive RT‐PCR.3 Therefore, primary analysis was performed using the full cohort. Robustness of findings was then investigated via sensitivity analysis which included only a subset with confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. We have not performed any imputation for missing data.

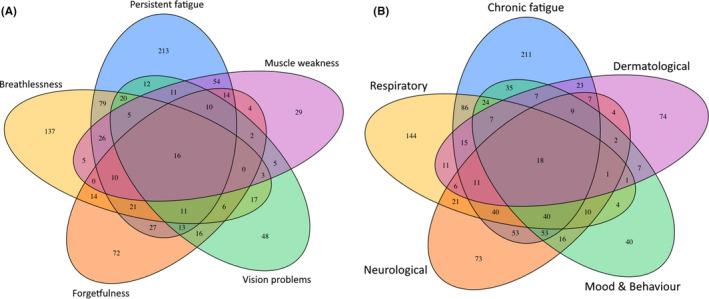

Venn diagrams were used to present the coexistence of the five most common persistent symptoms.

Two‐sided p‐values were reported for all statistical tests, a p‐value below 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.5.1.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Description of study population

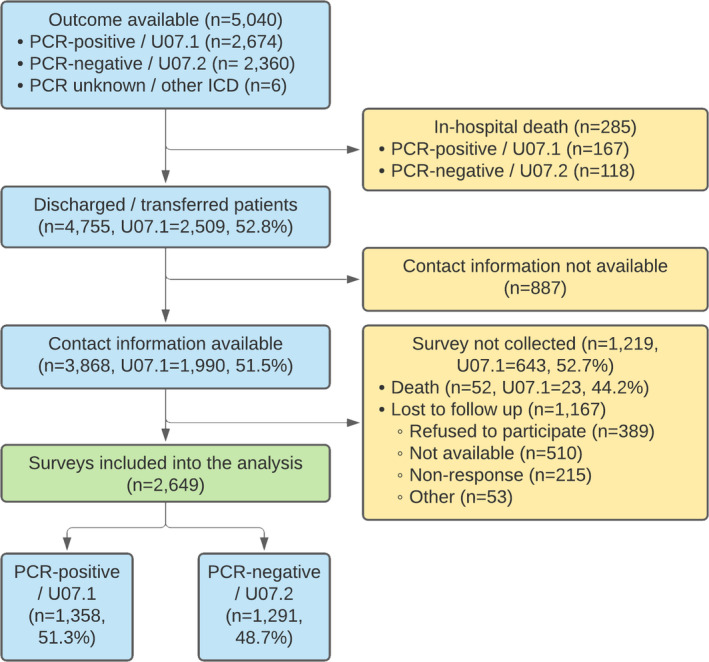

As outlined in Figure 1, out of 5,040 patients hospitalized with suspected COVID‐19 to the hospitals before 10 July 2020, 4,755 were discharged alive or transferred to another facility. Out of 4,019 patients with accurate contact information available, 2,649 were available for follow‐up (response rate 68.5%), 2,649 of whom had no missing baseline data in the electronic database and were included in the analysis. Of the 3,868 patients with contact information available 52 (1.3%) died after the hospital discharge.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of patients with COVID‐19 admitted to Sechenov University Hospital Network between April 8 and July 10, 2020. PCR, polymerase chain reaction

Analysis of the non‐response data was performed and Table S2 summarizes the differences between respondents and non‐respondents. A higher number of severe patients were among non‐respondents (4.2%) when compared with respondents (2.6%), while more individuals with asthma, type 2 diabetes and rheumatologic disorder were among respondents.

Out of 2,649 participants, 1,358 patients (51.3%) had RT‐PCR‐confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, whereas 1291 (48.7%) were clinically diagnosed with COVID‐19. In‐hospital case fatality ratio was 167/2674 (6.2%) in laboratory‐confirmed and 118/2360 (5%) in clinically diagnosed patients (p = .09). The median age was 56 years (IQR, 46–66; range, 18–100 years), and 1,353 (51.1%) were women. Median follow‐up time post‐discharge was 217.5 days (IQR 200.4–235.5, range 18–100). 1,948 participants (77.4%) had a higher education; 1,531, (59.8%) of the participants were working part‐ or full‐time; and 830 (32.4%) were retired (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients admitted to the Sechenov University Hospital Network

| Total | Laboratory‐confirmed RT‐PCR “+” (n = 1358) | Clinically diagnosed RT‐PCR “‐” (n = 1291) | p‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR) | 56 (46–66) | 57 (47–67) | 55 (44–65) | <.001 | |

| Age groups (years) | <50 | 870 (32.8%) | 407 (30%) | 463 (35.9%) | .002 |

| 50–69 | 1294 (48.8%) | 673 (49.6%) | 621 (48.1%) | ||

| 70–79 | 304 (11.5%) | 169 (12.4%) | 135 (10.5%) | ||

| ≥80 | 181 (6.8%) | 109 (8%) | 72 (5.6%) | ||

| Sex | Female | 1353 (51.1%) | 683 (50.3%) | 670 (51.9%) | .43 |

| Time from admission to discharge, days | Median (IQR) | 14.6 (12–17.6) | 15.1 (12.8–18.7) | 13.7 (11.6–16.1) | .49 |

| Time since discharge, days | Median (IQR) | 217.5 (200.4–235.5) | 215.3 (195.5–234.5) | 220.5 (204.4–237.3) | .54 |

| Highest completed educational level | School | 240 (9.5%) | 125 (9.7%) | 115 (9.3%) | .14 |

| University | 1948 (77.4%) | 989 (76.8%) | 959 (78%) | ||

| Not completed formal education or training | 37 (1.5%) | 13 (1%) | 24 (2%) | ||

| Occupation/ Working status | |||||

| Occupation/working status before Covid−19 | Working full‐time | 1473 (57.5%) | 745 (54.9%) | 728 (56.4%) | .65 |

| Working part‐time | 58 (2.3%) | 25 (1.8%) | 33 (2.6%) | ||

| Full time carer (children or others) | 47 (1.8%) | 22 (1.6%) | 25 (1.9%) | ||

| Unemployed | 47 (1.8%) | 23 (1.7%) | 24 (1.9%) | ||

| Unable to work due to chronic illness | 5 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 3 (0.2%) | ||

| Student | 21 (0.8%) | 8 (0.6%) | 13 (1%) | ||

| Retired/ Early retirement due to illness | 871 (34.0%) | 459 (33.8%) | 412 (31.9%) | ||

| Do not want to answer | 155 (6.1%) | 82 (6%) | 73 (5.7%) | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Chronic cardiac disease (not hypertension) | 476 (18.1%) | 273 (20.3%) | 203 (15.8%) | .004 | |

| Hypertension | 1219 (46.2%) | 646 (47.8%) | 573 (44.4%) | .11 | |

| Revascularization of peripheral and/or coronary arteries | 98 (3.7%) | 68 (5.1%) | 30 (2.3%) | <.001 | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease (not asthma) | 193 (7.3%) | 110 (8.2%) | 83 (6.5%) | .11 | |

| Asthma (physician diagnosed) | 121 (4.6%) | 73 (5.4%) | 48 (3.7%) | .05 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 123 (4.7%) | 72 (5.4%) | 51 (4%) | .12 | |

| Obesity (as defined by clinical staff) | 514 (19.6%) | 263 (19.6%) | 251 (19.6%) | 1 | |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 19 (0.7%) | 11 (0.8%) | 8 (0.6%) | .73 | |

| Mild liver disease | 50 (1.9%) | 24 (1.8%) | 26 (2%) | .75 | |

| Asplenia | 8 (0.3%) | 4 (0.3%) | 4 (0.3%) | 1 | |

| Chronic neurological disorder | 121 (4.6%) | 78 (5.8%) | 43 (3.4%) | .004 | |

| Malignant neoplasm | 93 (3.5%) | 62 (4.6%) | 31 (2.4%) | .004 | |

| Chronic haematologic disease | 30 (1.1%) | 21 (1.6%) | 9 (0.7%) | .06 | |

| AIDS / HIV | on ART | 4 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (0.3%) | .12 |

| not on ART | 5 (0.2%) | 3 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 1 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | Type 1 | 13 (0.5%) | 6 (0.4%) | 7 (0.5%) | .93 |

| Type 2 | 369 (14.1%) | 198 (14.7%) | 171 (13.4%) | .34 | |

| Rheumatologic disorder | 96 (3.7%) | 43 (3.2%) | 53 (4.1%) | .24 | |

| Dementia | 25 (1%) | 18 (1.3%) | 7 (0.5%) | .06 | |

| Tuberculosis | 2 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 | |

| Malnutrition | 6 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 4 (0.3%) | .64 | |

| With no comorbidities | 908 (34.3%) | 452 (33.3%) | 456 (35.3%) | <.001 | |

| With 1 comorbidity | 723 (27.3%) | 341 (25.1%) | 382 (29.6%) | ||

| With 2 comorbidities | 512 (19.3%) | 267 (19.7%) | 245 (19%) | ||

| With 3+ comorbidities | 506 (19.1%) | 298 (21.9) | 208 (16.1%) | ||

| COVID−19 severity | |||||

| Mild (not requiring supplementary oxygen or ventilation) | 1679 (63.4%) | 841 (61.9%) | 838 (64.9%) | .26 | |

| Moderate (requiring only supplementary oxygen) | 902 (34%) | 479 (35.3%) | 423 (32.8%) | ||

| Severe (requiring non‐invasive ventilation, or invasive ventilation or intensive care admission) | 68 (2.6%) | 38 (2.8%) | 30 (2.3%) | ||

Data are n (%), n/N (%), or median (IQR). Statistically significant results (p < .05) are highlighted in bold.

The most common pre‐existing comorbidity on admission was hypertension (1,219, 46.2%), followed by obesity (514, 19.6%) and type II diabetes (369, 14.1%). Most of the patients had mild COVID‐19 (1,637, 63.2%), with 902 (34%) classified as moderate and 68 (2.6%) as severe, respectively.

3.2. Symptoms at the time of follow‐up

At the time of the follow‐up interview, 1115 (42.1%) of the participants reported no symptoms, 444 (16.8%) reported one, 313 (11.8%) two and 777 (29.3%) three or more symptoms, with fatigue, shortness of breath, and forgetfulness being the most common. Just under half (1247;47.1%) reported one or more PS. Fatigue 551/2599 (21.2%), breathlessness 378/2614 (14.5%), forgetfulness 237/2597 (9.1%), muscle weakness 199/2592 (7.7%), problems seeing 198/2598 (7.6%), hair loss 183/2580 (7.1%) and problems sleeping 180/2583 (7%) were the most common PS reported at follow‐up. Detailed information on all the symptoms, including duration, is presented in Table S3.

Although many patients had PS since discharge, some participants reported at least one symptom of a differing duration during follow‐up interview; 285 (10.8%) had experienced these symptoms for 3 to 6 months, 179 (6.8%) between 2 and 3 months, 157 (5.9%) between 1 and 2 months, 103 (3.9%) between 2 and 4 weeks and 140 (5.3%) between 1 and 2 weeks, respectively. The duration of the ten common symptoms at the time of the follow‐up is shown in Figure S1.

A degree of overlap was found between the five most common PS, with 79/900 (8.8%) of patients experiencing both persistent fatigue and breathlessness, 54 (6%) persistent fatigue and muscle weakness. A smaller proportion of patients reported a combination of persistent fatigue, breathlessness and muscle weakness ‐ 26/900 (2.9%) with 16 (1.8%) patients having all five (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Venn plot presenting coexistence of (A) five most common persistent symptoms and (B) five most common categories of persistent symptoms at the time of the follow‐up interview

3.3. Persistent symptom categories at the time of follow‐up

With regard to categories of PS, chronic fatigue was found to be the most common 658/2593 (25%) at the time of the follow‐up interview, followed by respiratory 451/2616 (17.2%), neurological 375/2586 (14.5%), mood and behaviour changes 284/2591 (11%) and dermatological 206/2583 (8%) symptoms. A smaller number of patients experienced gastrointestinal 110/2599 (4.2%) and sensory 70/2622 (2.7%) problems since discharge.

A small number of the PS categories were co‐existent: 174 (6.6%) participants reported PS from three different categories at the time of the follow‐up interview;88 (3.3%) reported four categories, and 37 (1.4%) reported five categories or more. Co‐existence of five most common categories of persistent symptoms at the time of the follow‐up interview is presented in the Figure 2.

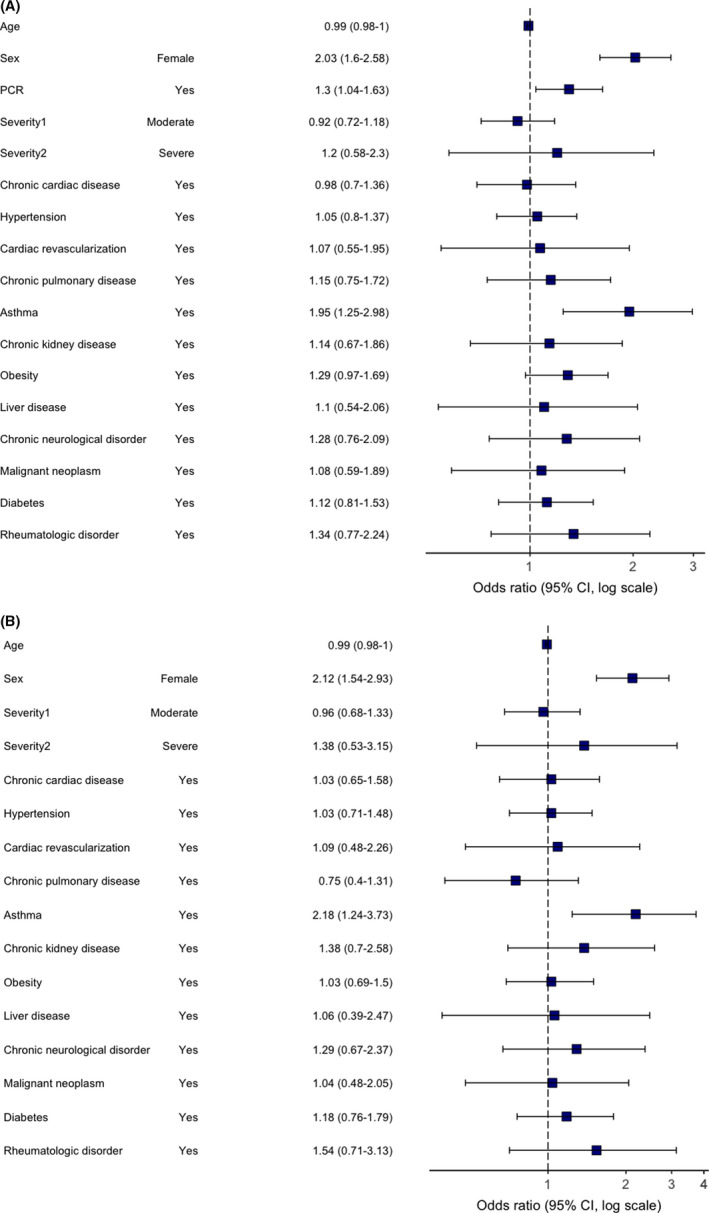

3.4. Risk factors associated with persistent symptom categories

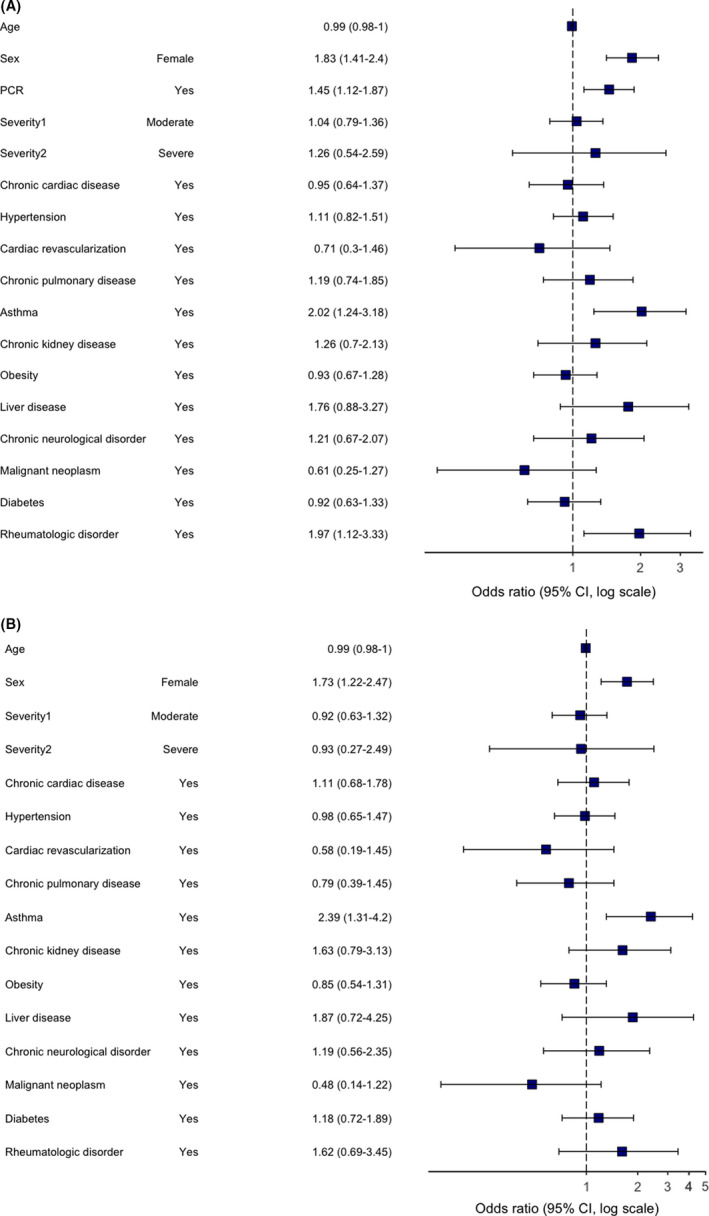

Risk factors for all categories were assessed. In multivariable regression analysis, female sex was a predictor of “any” PS category with an odds ratio of 1.83 (95% confidence interval 1.55 to 2.17), chronic fatigue 1.67 (1.39 to 2.02), neurological (2.03, 1.60 to 2.58), mood and behaviour (1.83, 1.41 to 2.40), dermatological (3.26, 2.36 to 4.57), gastrointestinal (2.50, 1.64 to 3.89), sensory (1.73, 2.06 to 2.89) and respiratory (1.31, 1.06 to 1.62) PS categories, respectively. The effect of female sex remained unchanged in the sensitivity analyses, which included patients with RT‐PCR‐confirmed COVID‐19 only, for all categories except respiratory and sensory. Pre‐existing asthma was not associated with “any” PS category, but was consistently associated with neurological (1.95, 1.25 to 2.98) and mood and behavioural changes (2.02, 1.24 to 3.18) (Figures 3 and 4), with associations remaining significant in the sensitivity analyses. Chronic pulmonary disease was associated with “any” PS category (1.47, 1.08 to 1.99), chronic fatigue (1.68, 1.21 to 2.32) (Figure 5) and gastrointestinal (1.93, 1.02 to 3.43) PS categories development. However, an association with “any” and gastrointestinal symptoms was not confirmed in the sensitivity analysis. Rheumatological disorder was associated with the mood and behavioural PS (1.97, 1.12–3.33), but the effect was not confirmed in the sensitivity analysis. Confirmed RT‐PCR during acute phase was significantly associated with chronic fatigue, neurological, mood and behaviour and gastrointestinal categories, confirming importance of the sensitivity analyses. More details of primary and sensitivity analyses are presented in Table 2, and forest plots are available as supplementary material.

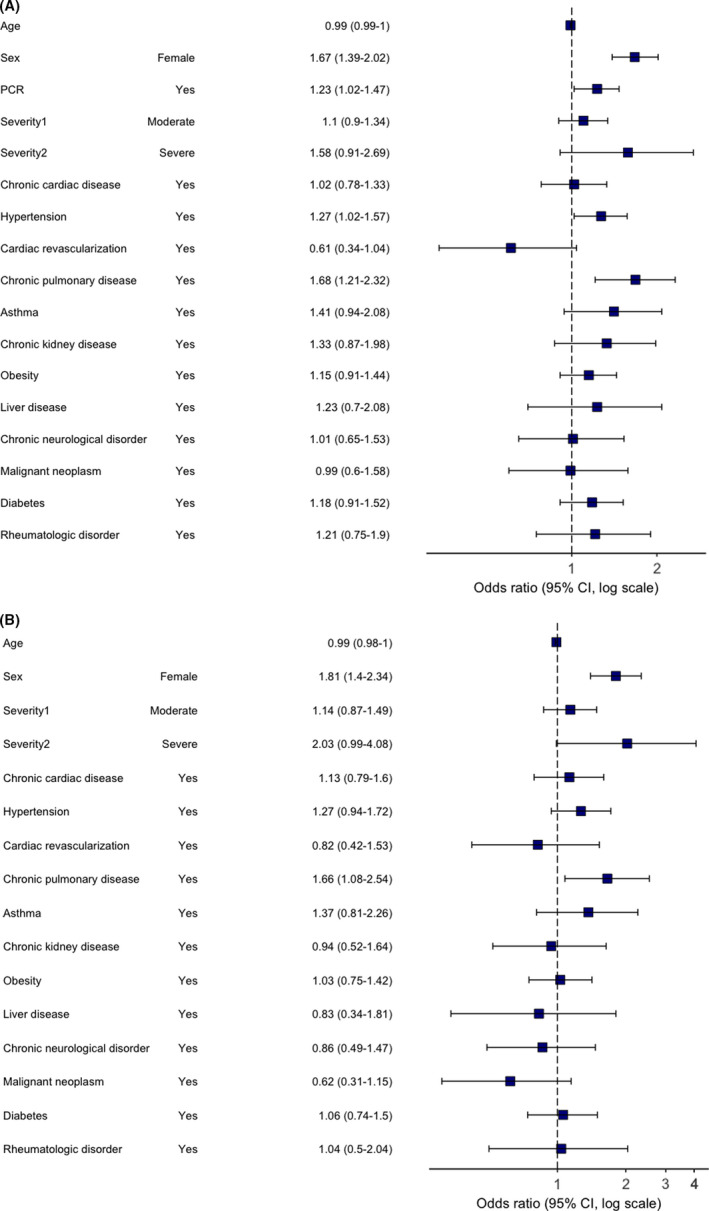

FIGURE 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model. Odds ratios and 95% CIs for “Neurological” category of persistent symptoms at the time of follow‐up. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval. (A) primary analysis (age, sex, comorbidities, severity and RT‐PCR were included as potential risk factors); (B) sensitivity analysis (performed in a subgroup of RT‐PCR positive patients only)

FIGURE 4.

Multivariable logistic regression model. Odds ratios and 95% CIs for “Mood and behaviour” category of persistent symptoms at the time of follow‐up. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval. (A) primary analysis (age, sex, comorbidities, severity and RT‐PCR were included as potential risk factors); (B) sensitivity analysis (performed in a subgroup of RT‐PCR positive patients only)

FIGURE 5.

Multivariable logistic regression model. Odds ratios and 95% CIs for “Chronic fatigue” category of persistent symptoms at the time of follow‐up. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval. (A) primary analysis (age, sex, comorbidities, severity and RT‐PCR were included as potential risk factors); (B) sensitivity analysis (performed in a subgroup of RT‐PCR positive patients only)

TABLE 2.

Risk factors significantly associated with the different categories of persistent symptoms in the primary (age, sex, comorbidities, severity and RT‐PCR were included as potential risk factors) and sensitivity (performed in a subgroup of RT‐PCR positive patients only) multivariable regression analyses

|

Persistent symptom Category (n)† |

Risk factor |

Primary analysis OR (95%CI) |

Sensitivity analysis OR (95%CI) |

Consistently associated factors* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any (n = 994) |

Female Sex Chronic pulmonary disease RT‐PCR “+” |

1.83 (1.55–2.17) 1.47 (1.08–1.99) 1.24 (1.06–1.46) |

1.88 (1.49–2.37) 1.32 (0.88–1.99) NA |

Female sex |

| Chronic fatigue (n = 658) |

Female Sex Chronic pulmonary disease Hypertension RT‐PCR “+” |

1.67 (1.39–2.02) 1.68 (1.21–2.32) 1.27 (1.02–1.57) 1.23 (1.02–1.47) |

1.81 (1.40–2.34) 1.66 (2.08–2.54) 1.27 (0.94–1.72) NA |

Female sex Chronic pulmonary disease |

| Respiratory (n = 451) | Female Sex | 1.31 (1.06–1.62) | 1.21 (0.90–1.62) | No |

| Neurological (n = 375) |

Female Sex Asthma RT‐PCR “+” |

2.03 (1.60–2.58) 1.95 (1.25–2.98) 1.30 (1.04–1.63) |

2.21 (1.54–2.93) 2.18 (1.24–3.73) NA |

Female sex Asthma |

| Mood and behaviour (n = 284) |

Female Sex Asthma Rheumatological disorder RT‐PCR “+” |

1.83 (1.41–2.40) 2.02 (1.24–3.18) 1.97 (1.12–3.33) 1.45 (1.12–1.87) |

1.73 (1.22–2.47) 2.39 (1.31–4.20) 1.62 (0.69–3.45) NA |

Female sex Asthma |

| Gastrointestinal (n = 206) |

Female Sex Chronic pulmonary disease RT‐PCR “+” |

2.50 (1.64–3.89) 1.93 (1.02–3.43) 1.56 (1.05–2.33) |

2.78 (1.61–4.96) 1.36 (0.54–2.99) NA |

Female sex |

| Dermatological (n = 110) | Female Sex | 3.26 (2.36–4.57) | 3.08 (1.99–4.88) | Female sex |

| Sensory (n = 70) | Female Sex | 1.73 (2.06–2.89) | 1.54 (0.78–3.07) | No |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; RT‐PCR “+,” real‐time polymerase chain reaction confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

The assessment of robustness is based on the magnitude, direction and/or statistical significance of the estimates.

Number of patients with at least one persistent symptom from this category. Statistically significant associations are presented in bold.

3.5. Dyspnoea scale and health state

Dyspnoea of different severity was reported by 318 (12%) patients during follow‐up with 194 (7.3%) equivalent to grade 3, 93 (3.5%) grade 4 and 31 (1.2%) grade 5 according to MRC Dyspnoea Scale (Table S4).

Participants reported lower scores (poorer health state) on the EuroQol visual analog scale at follow‐up compared with pre‐COVID‐19 onset, median 80 (IQR, 65–90) vs 85 (70–95) (p < .001). Significant worsening of the health state compared with pre‐COVID‐19 was found across all symptom categories, with the highest median difference reported by patients with gastrointestinal (−15), mood and behaviour (−13) and neurological (−10.5) symptoms (p < .001 for all) (Table S5). No statistically significant reduction in health state was found among patients reporting no symptoms. Participants falling into all symptom categories had significantly lower health state than those with no symptoms (p < .001 for all).

4. DISCUSSION

This prospective cohort study with a large sample size and has to our knowledge one of the longest follow‐up duration, assessing the long‐term health and psycho‐social consequences of COVID‐19 in hospitalized adults. The cohort included a similar number of RT‐PCR‐confirmed COVID‐19 and those who were clinically diagnosed with COVID‐19. The clinical features, chest CT, and blood test results did not differ between test confirmed and clinically diagnosed patients. Clinical outcomes were also identical, as discussed elsewhere.3 Patients were admitted to the hospitals during the first wave of the pandemic. At that time, local recommendations allowed for hospitalization of a milder patients than at present. This and much younger age of admitted patients, when compared with other cohorts,2 may explain that most of the patients had mild‐to‐moderate disease at the time of the acute episode. We found that six of ten patients experienced at least one symptom of any duration 6 to 8 months after hospital discharge and almost a half of the patients reported at least one PS, with chronic fatigue and respiratory problems being the most frequent PS categories. One in ten patients reported multisystem impacts with three or more categories of PS symptoms present at follow‐up. PS were experienced by both sexes, with a higher risk amongst women. Pre‐existing chronic pulmonary disease was associated with chronic fatigue, and asthma with a higher risk of neurological symptoms and mood and behaviour problems.

4.1. Persistent symptoms

Other studies of previously hospitalized and non‐hospitalized COVID‐19 patients reported presence of short‐ and long‐term symptoms.16, 17, 18 The majority of patients in our cohort experienced PS from the time of discharge, with a smaller number developing symptoms months following discharge. Persistent fatigue and breathlessness were the most frequent PS in our cohort, which is consistent with recent report from China.6 Forgetfulness and vision problems were also common, while problems sleeping was less common (10.2%) compared to rates reported by follow‐up data from China (26%).6

A novel finding relates to the development of symptoms, that were not present before COVID‐19 infection and/or at the time of discharge, weeks or months since recovery from COVID‐19. To our knowledge, this aspect has not been investigated in previous studies, as most of the cohorts did not collect data on the duration of the symptoms present at follow‐up. Patterns of the symptom development following COVID‐19 should be further investigated in future research.

4.2. Risk factors associated with persistent symptoms

Female sex was significantly associated with an increased risk of PS, regardless of symptom category, reflecting previous findings6 and digital App19 studies. Chronic pulmonary disease was a risk factor for the development of chronic fatigue. An association between chronic pulmonary disease and severe acute COVID‐19 was found in many studies,20 but it has not been previously reported as a risk factor for COVID‐19 sequelae. The presence of chronic pulmonary disease has been previously associated with chronic fatigue syndrome.21 The pandemic also had a significant adverse impact on care and support for patients with chronic pulmonary conditions, including a reduction in face‐to‐face clinic availability, lack of access to pulmonary rehabilitation sessions and hospital care during an exacerbation due to fear of COVID‐19 exposure.22 The causality cannot be determined and we are unable to conclude if lack of follow‐up and involvement in rehabilitation programmes for chronic pulmonary conditions was the cause of ongoing symptoms. Future research should investigate COVID‐19 consequences in this group of patients in greater detail.

Data from the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK suggested that asthma is a risk factor for post‐COVID condition.23 However, it did not separate ongoing respiratory symptoms which may have been due to incitement of the pre‐existing asthma from those in other systems. We found that asthma was associated with an increased risk of PS during follow‐up, specifically neurological and mood and behaviour. Although asthma has not been associated with a higher risk of hospital admission and/or in‐hospital mortality in COVID‐19 patients,24, 25 different results may be found when considering the long‐term consequences of infection. Recent research suggested that COVID‐19 sequelae may be associated with the mast cell activation syndrome26 and the Th‐2 biased immunological response in asthmatic patients may be responsible for an increased risk of long‐term consequences from the infection. This finding may point to immune‐mediated mechanisms but requires confirmation in a larger sample size with a more detailed investigation, including in‐clinic visits.

4.3. Health state

Patients with all categories of PS reported significantly lower health state when compared with symptom‐free patients. They also considered the health state to be lower than before the COVID‐19 episode. This is consistent with previous reports from different countries.5, 6, 27 This finding points to the multi‐factorial adverse effects of COVID‐19 and to the need for wide ranging and longer term support.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study is the use of pre‐positioned data collection method using ISARIC Core CRF for acute phase data and ISARIC Long‐term Follow‐up Study CRF. Another strength is the large sample size, and this cohort has the lonest follow‐up assessment of hospitalized adults to date. Stratification to determine whether the symptoms were persistent following COVID‐19 was another novel aspect of the study. At the same time, this cohort study has some limitations. First, the study population only included patients within Moscow, although regional clustering is common to all major cohort studies published during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Second, acute data were collected from the electronic medical records with no access to additional information that could be potentially retrieved from the medical notes. The diagnoses of chronic pulmonary disease and asthma were reported by the patients/carers at the time of the hospital admission and subsequently verified during follow‐up telephone interview. Third, almost half of the patients in our cohort did not have RT‐PCR confirmed COVID‐19 infection, and however, our previous work3 showed that clinical features of COVID‐19 and in‐hospital mortality were the same in COVID‐19 clinically diagnosed and laboratory‐confirmed cases. We also performed sensitivity analyses using data from the laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 patients only to ensure consistency and robustness of the findings. Fifth, some patients may have developed additional comorbidities or complications since the hospital discharge, which were not appropriately captured and could potentially affect the QoL and symptom prevalence and persistence. There is also a risk of recall bias in reporting quality of life and dyspnoea preceding COVID‐19. A third of potentially eligible participants were not enrolled, which is also a limitation, although most characteristics of those successfully interviewed were similar to those who were potentially eligible but not interviewed.

The study used to generate this data within the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol initiative is a prospective pandemic preparedness protocol which is agnostic to disease and has a pragmatic design to allow recruitment during pandemic conditions. The reality of conducting research in outbreak conditions do not allow for appropriate co‐enrolment of a control group, which is not practical. One of the issues which has not been addressed so far in clinical research is what control group of individuals admitted to hospital during this period when hospitals were overwhelmed with COVID‐19 cases could provide a valid control group. The design of this study allows only to describe the feature of COVID‐19 survivors and cannot involve a control group. COVID‐19 is not just a respiratory tract infection so there is no one‐fit‐all control group.

5. CONCLUSION

At 6‐ to 8‐month follow‐up, many patients had experienced symptoms from the time of hospital discharge, with chronic fatigue and respiratory problems being the most common sequelae. Most patients reported symptoms at 6–8 months commencing from the time of discharge, although a subgroup reported symptoms limited to a few weeks and/or months after the acute phase. One in ten individuals had multisystem involvement at the time of the follow‐up. Female sex was the main risk factor for most of the long‐lasting symptom categories development, while chronic pulmonary disease was associated with a higher risk of chronic fatigue development and asthma with the neurological and mood and behaviour changes. Future studies should focus on patients with multisystem involvement and longer follow‐up of a large sample will allow for a better understanding of COVID‐19 sequelae and help with the phenotype recognition. Investigation of immunological aspects of the association between asthma and several long‐COVID outcomes may identify mechanisms and therapeutic targets for therapy to mitigate adverse consequences.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

J. Genuneit reports working as a project manager of unrestricted research grants on the composition of breast milk to the Ulm University and Leipzig University. M.G. Semple reports grants from DHSC National Institute of Health Research UK, grants from Medical Research Council UK, grants from Health Protection Research Unit in Emerging & Zoonotic Infections, University of Liverpool outside the submitted work; he also reports a minority ownership at Integrum Scientific LLC, Greensboro, NC, USA outside the submitted work. T. Vos reports personal fees for work on Global Burden of Disease Study from Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no relevant conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

DM, DB, PBo, ES, AS, AG and OB conceptualized the project, formulated research goals and aims. DM, DB, OB, NN, PBu, PC, CA, JG, ADG, AG, TMD, SWH, LM, GC, PH, LS, JTS, MGS, JOW, TV and PO were responsible for the study design and methodology and participated in overall project design discussions. OB and SWH implemented the computer code and supporting algorithms and tested of existing code components. DM and OB tested hypotheses and discussed sensitivity analyses. OB performed statistical analysis. The StopCOVID Research Team, NN, PBu, MA, AG, AS, SA and VK conducted a research and investigation process, specifically performed data extraction, telephone interviews and data collection. VF, AAS, PT, VSS, VVR, DM, DB, PT, PG and SA provided study materials, access to patient data, laboratory data and computing resources. NN, PBu, PBo, ES and OB managed activities to annotate metadata and maintain research data for initial use and later reuse. OB, PBo, ES, AS and AG prepared visualization and worked on the data presentation. DM, DB and PG were responsible for the oversight and leadership for the research activity planning and execution. DM, DB, PBo, ES, AS, AG and OB provided management and coordination for the research activity planning and execution. VF, AAS, PT, VSS, VVR, DM, DB and PG were responsible for the acquisition of the financial support for the project leading to this publication. DM, PBu, NN, OB, JOW, PC and CA wrote original draft. All the authors critically reviewed and commented on the manuscript draft at both, pre‐ and post‐submission stages.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank RFBR, grant 20‐04‐60063 for supporting the work. We would also like to thank UK Embassy in Moscow for providing a grant a grant INT 2021/RSM C 19 01 supporting our project. We are very grateful to the Sechenov University Hospital Network clinical staff and to the patients, carers and families for their kindness and understanding during these difficult times of COVID‐19 pandemic. We would like to express our very great appreciation to ISARIC Global COVID‐19 follow‐up working group for the survey development. We would like to thank Mr Maksim Kholopov for providing technical support in data collection and database administration. We are very thankful to Eat & Talk, Luch, Black Market, FLIP and Academia for providing us the work space in time of need. We are grateful to Ms Asmik Avagyan, Ms Daria Belykh, Ms Ekaterina Belyakova, Ms Anna Berbenyuk, Mr Dmitry Eliseev, Ms Mariia Grosheva, Ms Nelli Khusainova, Ms Maria Kislova, Ms Valeria Klishina, Ms Karina Kovygina, Ms Natalia Kogut, Ms Yana Kohanovskaya, Ms Anastasia Kuznetsova, Ms Elza Lidzhieva, Ms Nadezhda Markina, Mr Georgiy Novoselov, Ms Anna Pushkareva, Ms Olga Romanova, Ms Maria Shoshorina, Ms Jasmin Sibkhan, Ms Olga Spasskaya, Ms Anna Surkova, Ms Nailya Urmantaeva, Ms Ekaterina Varlamova, Ms Margarita Yegiyan, Ms Margarita Zaikina, Ms Anastasia Zorina, Ms Elena Zuikova, Prof Natalia V. Chichkova, Dr Anna V. Buchneva and Prof Natalya Serova for assistance in data extraction, document translation and help during the project. Finally, we would like to extend our gratitude to the Global ISARIC team and ISARIC Co‐ordinating Centre for their continuous support, expertise and for the development of the outbreak ready standardized protocols for the data collection.

1.

Sechenov Stop COVID Research Team (Group authors)

Elina Abdeeva,1 Nikol Alekseeva,1 Elena Antsiferova,1 Elena Artigas,1 Anastasiia Bairashevskaia,1 Anna Belkina,1 Vadim Bezrukov,1 Semyon Bordyugov,1 Maria Bratukhina,1 Jessica Chen,2 Salima Deunezhewa,1 Khalisa Elifkhanova,1 Anastasia Ezhova,1 Yulia Filippova,1 Aleksandra Frolova,1 Julia Ganieva,1 Anastasia Gorina,1 Yulia Kalan,1 Bogdan Kirillov,1 Mariia Korgunova,1 Alexandra Krupina,1 Anna Kuznetsova,1 Ekaterina Listovskaia,1 Margarita Mikheeva,1 Aigun Mursalova,1 Marina Ogandzhanova,1 Callum Parr,2 Mikhail Rumyantsev,1 Denis Smirnov,1 Nataliya Shishkina,1 Yasmin El‐Taravi,1 Maria Varaksina,1 Maria Vodianova,1 Anna Zezyulina1

1Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia

2Inflammation, Repair and Development Section, National Heart and Lung Institute, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, UK

Munblit D, Bobkova P, Spiridonova E, et al. Incidence and risk factors for persistent symptoms in adults previously hospitalized for COVID‐19. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:1107–1120. 10.1111/cea.13997

Daniel Munblit, Polina Bobkova, Ekaterina Spiridonova, Anastasia Shikhaleva, Aysylu Gamirova, and Oleg Blyuss contributed equally to the paper.

Sechenov Stop COVID Research Team (Group authors) are present in Appendix.

Contributor Information

Daniel Munblit, Email: daniel.munblit08@imperial.ac.uk.

Sechenov StopCOVID Research Team:

Elina Abdeeva, Nikol Alekseeva, Elena Antsiferova, Elena Artigas, Anastasiia Bairashevskaia, Anna Belkina, Vadim Bezrukov, Semyon Bordyugov, Maria Bratukhina, Jessica Chen, Salima Deunezhewa, Khalisa Elifkhanova, Anastasia Ezhova, Yulia Filippova, Aleksandra Frolova, Julia Ganieva, Anastasia Gorina, Yulia Kalan, Bogdan Kirillov, Mariia Korgunova, Alexandra Krupina, Anna Kuznetsova, Ekaterina Listovskaia, Margarita Mikheeva, Aigun Mursalova, Marina Ogandzhanova, Callum Parr, Mikhail Rumyantsev, Denis Smirnov, Nataliya Shishkina, Yasmin El‐Taravi, Maria Varaksina, Maria Vodianova, and Anna Zezyulina

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DM, upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web‐based dashboard to track COVID‐19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533‐534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid‐19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munblit D, Nekliudov NA, Bugaeva P, et al. StopCOVID cohort: an observational study of 3,480 patients admitted to the Sechenov University hospital network in Moscow city for suspected COVID‐19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;73(1):1‐11. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pritchard MG. COVID‐19 symptoms at hospital admission vary with age and sex: ISARIC multinational study. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2010.2026.20219519. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carfi A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Gemelli against C‐P‐ACSG. persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID‐19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603‐605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6‐month consequences of COVID‐19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397(10270):220‐232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michelen M, Manoharan L, Elkheir N, et al. Characterising long‐term covid‐19: a rapid living systematic review. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2012.2008.20246025. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wise J. Long covid: WHO calls on countries to offer patients more rehabilitation. BMJ. 2021;372:n405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meeting the challenge of long COVID. Nat Med. 2020;26(12):1803. 10.1038/s41591-020-01177-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The L. Facing up to long COVID. The Lancet. 2020;396(10266):1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayoubkhani D, Khunti K, Nafilyan V, et al. Post‐covid syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with covid‐19: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;372:n693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Consortium . ISARaeI. COVID‐19 core case report form acute respiratory infection clinical characterisation data tool. 2020; https://isaric.org/wp‐content/uploads/2020/10/ISARIC_WHO_nCoV_CORE_CRF_25.08.2020.pdf. Accessed 6‐th of February, 2021.

- 13.The World Health Organization. Global COVID‐19 Clinical Platform Case Report Form (CRF) for Post COVID condition (Post. COVID‐19 CRF). 2021; https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global‐covid‐19‐clinical‐platform‐case‐report‐form‐(crf)‐for‐post‐covid‐conditions‐(post‐covid‐19‐crf‐). Accessed 10‐th of February, 2021.

- 14.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an International cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2012.2024.20248802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A'Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post‐acute covid‐19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370:m3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al‐Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High‐dimensional characterization of post‐acute sequelae of COVID‐19. Nature. 2021;594(7862):259‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Augustin M, Schommers P, Stecher M, et al. Post‐COVID syndrome in non‐hospitalised patients with COVID‐19: a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;6:100122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simani L, Ramezani M, Darazam IA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of chronic fatigue syndrome and post‐traumatic stress disorder after the outbreak of the COVID‐19. J Neurovirol. 2021;27(1):154‐159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):626‐631. 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Q, Meng M, Kumar R, et al. The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of COVID‐19: A systemic review and meta‐analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):1915‐1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baghai‐Ravary R, Quint JK, Goldring JJ, Hurst JR, Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. Determinants and impact of fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2009;103(2):216‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung JM, Niikura M, Yang CWT, Sin DD. COVID‐19 and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2):2002108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of Long‐COVID: analysis of COVID cases and their symptoms collected by the Covid Symptoms Study App. medRxiv. 2010:2020.2010.2019.20214494. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avdeev S, Moiseev S, Brovko M, et al. Low prevalence of bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive lung disease among intensive care unit patients with COVID‐19. Allergy. 2020;75(10):2703‐2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferastraoaru D, Hudes G, Jerschow E, et al. Eosinophilia in asthma patients is protective against severe COVID‐19 illness. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(3):1152‐1162.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afrin LB, Weinstock LB, Molderings GJ. Covid‐19 hyperinflammation and post‐Covid‐19 illness may be rooted in mast cell activation syndrome. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:327‐332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Milne A, et al. Patient outcomes after hospitalisation with COVID‐19 and implications for follow‐up: results from a prospective UK cohort. Thorax. 2020;76(4):399‐401. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DM, upon reasonable request.