Abstract

Background

Headache is identified as a common post‐COVID sequela experienced by COVID‐19 survivors. The aim of this pooled analysis was to synthesize the prevalence of post‐COVID headache in hospitalized and non‐hospitalized patients recovering from SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Methods

MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases, as well as medRxiv and bioRxiv preprint servers, were searched up to 31 May 2021. Studies or preprints providing data on post‐COVID headache were included. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale. Random effects models were used for meta‐analytical pooled prevalence of post‐COVID headache. Data synthesis was categorized at hospital admission/symptoms' onset, and at 30, 60, 90, and ≥180 days afterwards.

Results

From 9573 studies identified, 28 peer‐reviewed studies and 7 preprints were included. The sample was 28,438 COVID‐19 survivors (12,307 females; mean age: 46.6, SD: 17.45 years). The methodological quality was high in 45% of the studies. The overall prevalence of post‐COVID headache was 47.1% (95% CI 35.8–58.6) at onset or hospital admission, 10.2% (95% CI 5.4–18.5) at 30 days, 16.5% (95% CI 5.6–39.7) at 60 days, 10.6% (95% CI 4.7–22.3) at 90 days, and 8.4% (95% CI 4.6–14.8) at ≥180 days after onset/hospital discharge. Headache as a symptom at the acute phase was more prevalent in non‐hospitalized (57.97%) than in hospitalized (31.11%) patients. Time trend analysis showed a decreased prevalence from the acute symptoms’ onset to all post‐COVID follow‐up periods which was maintained afterwards.

Conclusion

This meta‐analysis found that the prevalence of post‐COVID headache ranged from 8% to 15% during the first 6 months after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Keywords: COVID‐19, headache, meta‐analysis, post‐COVID, prevalence

Headache is a common acute symptom of COVID‐19 and also a common post‐COVID‐19 symptom. The prevalence of post‐COVID headache ranged from 8% to 15% during the first 6 months after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

INTRODUCTION

Headache is a symptom experienced at the acute phase of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection (pooled prevalence 10.1%, 95% CI 8.7–11.5) [1]. A Cochrane review concluded that headache was one of the five most prevalent symptoms during the acute phase and is considered a red flag for COVID‐19 because it has a specificity of 90% (in addition to fever, fatigue, myalgia, and arthralgia) [2]. A recent survey found that the most frequent neurological finding associated with COVID‐19 seen by neurologist is headache (61.9%) [3]. Additionally, headache is a frequent symptom experienced after the acute infection as observed in recent meta‐analyses [4, 5]. However, previous meta‐analyses pooled prevalence rates without considering follow‐up periods and without differentiating between hospitalized and non‐hospitalized patients [4, 5]. No attempt has been made to systematically estimate the prevalence rate of post‐COVID headache. We aimed to explore the time course of headache from infection to different post‐COVID follow‐up periods and differentiating whether patients were hospitalized or not.

METHODS

A systematic review and meta‐analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement was conducted and it was prospectively registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) database (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/WB8H4). Electronic literature searches were conducted for studies published up to 31 May 2021 in the PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases, as well as on medRxiv and bioRxiv preprint servers. The search was conducted using the following terms: “long COVID”, “long hauler”, “post‐COVID symptoms”, “persistent post‐COVID”, AND “headache”. No language restrictions were applied. Title, abstract, and full text of identified items were analyzed, and those providing the prevalence of post‐COVID headache were pooled. Data extraction included authors, country, sample size, setting, and headache prevalence at onset and at post‐COVID follow‐ups. The methodological quality of studies was assessed with the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale [6]. In longitudinal cohort studies or case‐control studies, a maximum of 9 stars can be awarded (high quality ≥7 stars). In cross‐sectional studies, a maximum of 3 stars can be awarded (good quality: 3 stars; fair quality: 2 stars; poor quality: 1 star). Search strategy, data extraction, and methodological quality were conducted by two authors.

A pooled meta‐analysis was performed by calculating the overall proportion using the metaprop function. Overall means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated using the pool.groups function from the dmetar package. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were converted to mean and SD. If necessary, data were estimated from graphs using the GetData Graph Digitizer v.2.26.0.20 software. We used a random effects model because potential heterogeneity was expected (I 2 ≥ 75%). We calculated sample size‐weighted mean scores for each study reporting data with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) in addition to potential meta‐analytical summary effects on the pooled prevalence. Data synthesis was categorized at onset and at 30, 60, 90, and ≥180 days after onset/hospital discharge. To determine the time course of post‐COVID headache (from onset to ≥180 days afterwards), Freeman−Tukey double arcsine transformation was conducted using the escalc function in the metafor package. The rma.mv (meta‐analytic multilevel random effects model with moderators via linear mixed effect models) was used to carry out a multilevel meta‐analysis with three levels to identify time and time*subgroup effects.

RESULTS

From an initial 9573 potential articles and preprints, after duplicate screening and excluding papers not related to post‐COVID headache, 55 were initially identified, 20 of which were excluded because they were case reports or review articles (Figure S1). The pooled analysis finally included 28 peer‐reviewed studies and 7 medRxiv preprints (reference list available as AppendixS4). The features of the samples of the included studies are shown in Table S1. Nineteen studies included hospitalized patients, whereas 17 included non‐hospitalized patients (one study included hospitalized/non‐hospitalized patients). The sample comprised 28,438 COVID‐19 survivors (12,307 females; mean age: 46.61, SD: 17.45 years). The prevalence of post‐COVID headache was investigated at different follow‐up timeframes: 30 days (n = 11, 5 hospitalized and 6 non/hospitalized), 60 days (n = 9, 4 hospitalized and 5 non/hospitalized), 90 days (n = 11, 6 hospitalized and 5 non/hospitalized), and ≥180 days (n = 13, 5 hospitalized and 8 non/hospitalized) after hospital discharge or symptoms’ onset, respectively. Table S2 details the assessment of headache among the studies at each time point.

Twenty (57.2%) studies were cross‐sectional, 18 were considered of fair quality (2/3 stars), and two were of poor quality (1/3 stars). Twelve (34.3%) were longitudinal cohort studies with high methodological quality (≥7/9 stars), whereas three were case−control studies, one of poor quality (5/9 stars) and two of high quality (7/9 stars). Table S3 summarizes the star scoring of all the studies included.

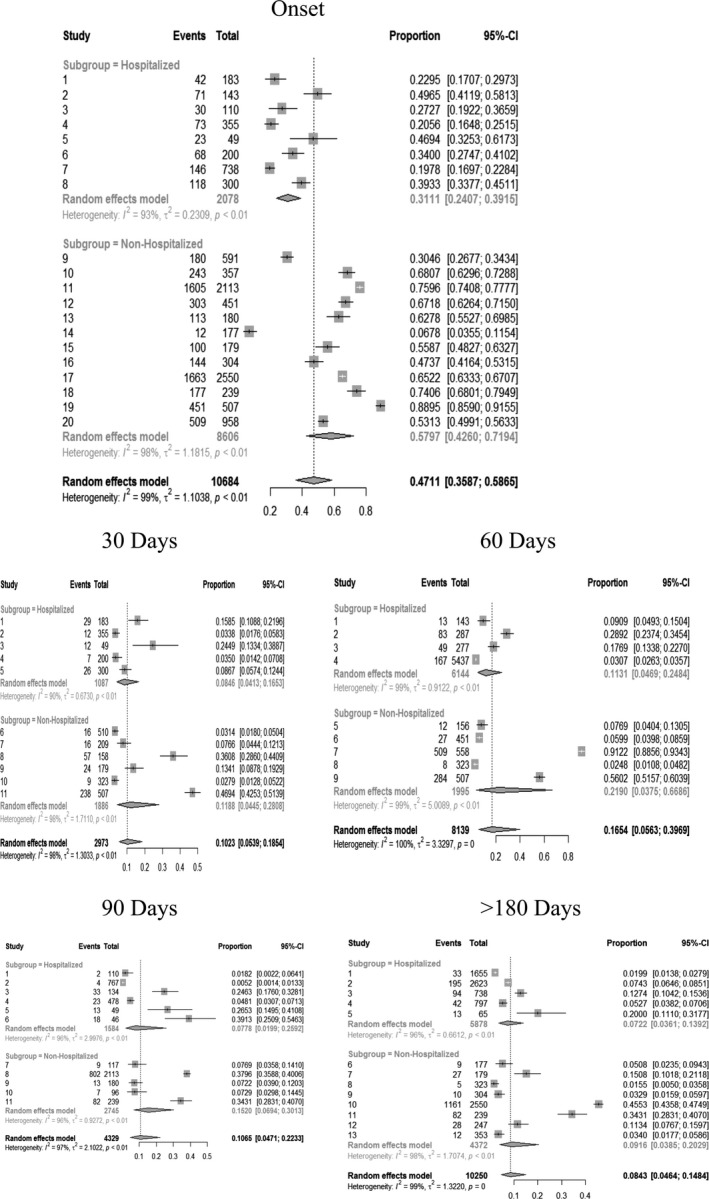

Pooled prevalence data of headache at the acute phase and at each post‐COVID follow‐up period experienced by the total sample, and separately by hospitalization or not, are shown in Figure 1. The overall prevalence of post‐COVID headache was 47.1% (95% CI 35.8–58.6) at symptoms' onset/hospital admission, 10.2% (95% CI 5.4–18.5) at 30 days, 16.5% (95% CI 5.6–39.7) at 60 days, 10.6% (95% CI 4.7–22.3) at 90 days, and 8.4% (95% CI 4.6–14.8) ≥180 days after onset/hospital discharge (Figure 1). All pooled data showed high heterogeneity (I 2 > 90%). No significant differences in the prevalence of post‐COVID headache between hospitalized and non‐hospitalized patients were observed at any follow ‐up period. Headache as a symptom at the acute phase of the disease was more prevalent in non‐hospitalized patients (57.97%) than in hospitalized (31.11%) patients.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of headache as a symptom at onset/hospital admission and as a post‐COVID symptom 30, 60, 90, and ≥180 days after the infection.

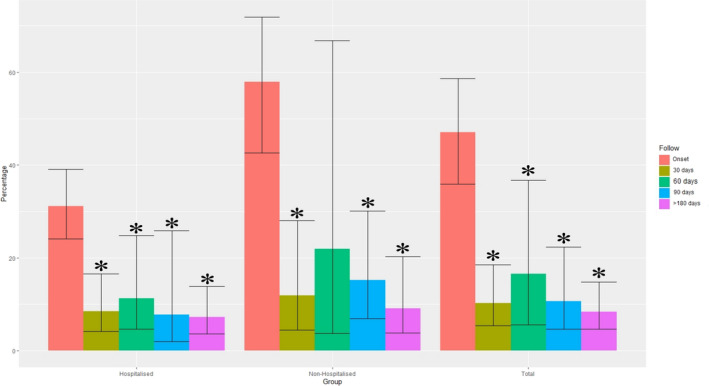

Figure 2 graphs the time course of headache at onset/hospitalization to 30, 60, 90, and ≥180 days. The random effects model revealed a significant effect of time (p < 0.001) showing that the prevalence of headache dropped from the symptoms’ onset to all post‐COVID follow‐up periods and was maintained afterwards. A slight increase 60 days afterwards was observed but did not reach statistical significance. No significant group*time effect was found, showing that this tendency was not related to hospitalization or not.

FIGURE 2.

Time course trend of post‐COVID headache from the onset of the symptoms/hospital admission to 30, 60, 90, and ≥180 days after discharge. *Statistically significant effect (p < 0.001) showing a time trend during the different follow‐up periods.

DISCUSSION

This meta‐analysis represents the first pooled analysis on post‐COVID headache. Lopez‐Leon et al. reported a pooled prevalence of 44% (95% CI 13–78%, n = 2 studies) for post‐COVID headache [4], whereas Iqbal et al. reported a pooled prevalence of 12% (95% CI 0–44%, n = 3 studies) [5]. Both meta‐analyses provided prevalence rates without distinction between hospitalized/non‐hospitalized patients nor considering post‐COVID periods [4, 5].

This meta‐analysis revealed that the overall prevalence of post‐COVID headache decreased after the acute phase and remained stable at different post‐COVID follow‐up periods during the first 6 months (Figure 2). This time course was similar in hospitalized and non‐hospitalized COVID‐19 patients, supporting the premise that headache seems to be a common post‐COVID symptom experienced in severe patients (hospitalized) and also similarly in moderate to mild patients (non‐hospitalized).

Interestingly, the prevalence of headache as an onset symptom at the acute phase was more prevalent in those individuals who were non‐hospitalized. One potential explanation is related to the fact that headache is not considered to be a bothersome symptom compared with other onset COVID‐19‐related symptoms such as dyspnea or fever, which are commonly seen in hospitalized patients. It is possible that headache is underreported by patients at hospital admission. This situation could be explained by the fact that the presence of headache as an onset symptom at hospital admission is associated with better prognosis for hospitalization by COVID‐19 [7]. Because of the high prevalence of headache as an onset symptom in COVID‐19, its characterization could help to highlight COVID‐19‐associated symptoms and to better define the appropriate treatment [8].

The COVID‐related cytokine storm seems to be a common underlying mechanism linking headache and COVID‐19 [9, 10]. Similarly, the overlap between neuropsychological or neuropsychiatric symptoms and headache is also present in the COVID‐19 literature [11]. No study included in the current meta‐analysis has considered this overlapping.

These results should be considered in tandem with our study’s strengths and weaknesses. The rigorous methodology applied, the methodological quality assessment, and the inclusion of 28 peer‐reviewed studies and 7 medRxiv preprints differentiating between hospitalized and non‐hospitalized patients and analyzing headache prevalence from COVID‐19 onset to different post‐COVID periods could be considered strengths. However, several shortcomings are also present. First, the small number of studies in some comparisons and the high heterogeneity in the pooled data limit the generalization of the results. Further, 55% studies were of fair methodological quality. Third, headache was self‐reported by patients themselves in all the studies, without being diagnosed by a neurologist. This should be taken into account since headache should be diagnosed and treated by an experienced neurologist. This identified shortcoming is relevant since characterization of COVID‐19‐associated headache represents an important topic for neurologists. Similarly, no study provided prevalence data stratified by gender. This will be important for future studies due to the higher prevalence of headaches in female patients and the presence of gender differences in COVID‐19 [12]. Similarly, 60% of the studies were cross‐sectional; therefore, more longitudinal studies investigating the time course of headache as an associated COVID‐19 symptom are needed. Finally, identifying risk factors associated with post‐COVID headache will be crucial for future research.

CONCLUSIONS

This meta‐analysis found that the prevalence of post‐COVID headache ranged from 8% to 15% during the first 6 months after the acute infection but with a prevalence around 50% during hospitalization. The time course of post‐COVID headache seems to be stable during the first 180 days, but longitudinal studies are needed. Identification of risk factors associated with post‐COVID headache will ensure immediate action and counselling of this patient population.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest is declared by any of the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Cesar Fernández‐de‐las‐Peñas: Conceptualization (lead); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Resources (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Marcos Navarro‐Santana: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (lead); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Software (lead); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Victor Gómez‐Mayordomo: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (lead). Maria L. Cuadrado: Conceptualization (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Supervision (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). David García‐Azorín: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (lead); Supervision (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (lead); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Lars Arendt‐Nielsen: Conceptualization (equal); Funding acquisition (lead); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Resources (equal); Supervision (lead); Validation (lead); Visualization (lead); Writing‐review & editing (lead). Gustavo Plaza‐Manzano: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Resources (equal); Supervision (lead); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal).

Supporting information

Fig S1

Tab S1‐S3

Appendix S4

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Center for Neuroplasticity and Pain (CNAP) is supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF121).

Fernández‐de‐las‐Peñas C, Navarro‐Santana M, Gómez‐Mayordomo V, et al. Headache as an acute and post‐COVID‐19 symptom in COVID‐19 survivors: A meta‐analysis of the current literature. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:3820–3825. 10.1111/ene.15040

Funding information

The project is supported by a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (0067235). The sponsor had no role in the design, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, draft, review, or approval of the manuscript or its content. The authors were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, and the sponsor did not participate in this decision.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published text and supplementary material. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Islam MA, Alam SS, Kundu S, Hossan T, Kamal M, Cavestro C. Prevalence of headache in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 14,275 patients. Front Neurol. 2020;11:562634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Struyf T, Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, et al. Signs and symptoms to determine if a patient presenting in primary care or hospital outpatient settings has COVID‐19 disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7:CD013665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moro E, Priori A, Beghi E, et al. The international European Academy of Neurology survey on neurological symptoms in patients with COVID‐19 infection. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1727‐1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lopez‐Leon S, Wegman‐Ostrosky T, Perelman C, et al. More than 50 long‐term effects of COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. medRxiv. 2021:2021.01.27.21250617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iqbal FM, Lam K, Sounderajah V, Clarke JM, Ashrafian H, Darzi A. Characteristics and predictors of acute and chronic post‐COVID syndrome: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;36:100899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wells GA, Tugwell P, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta‐analyses. Accessed June 15, 2021. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp; 2015.

- 7. Gonzalez‐Martinez A, Fanjul V, Ramos C, et al. Headache during SARS‐CoV‐2 infection as an early symptom associated with a more benign course of disease: a case‐control study. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:3426‐3436. 10.1111/ene.14718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Trigo López JT, García‐Azorín D, Planchuelo‐Gómez Á, García‐Iglesias C, Dueñas‐Gutiérrez C, Guerrero AL. Phenotypic characterization of acute headache attributed to SARS‐CoV‐2: an ICHD‐3 validation study on 106 hospitalized patients. Cephalalgia. 2020;40:1432‐1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Afrin LB, Weinstock LB, Molderings GJ. Covid‐19 hyperinflammation and post‐Covid‐19 illness may be rooted in mast cell activation syndrome. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:327‐332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conti P, D'Ovidio C, Conti C, et al. Progression in migraine: role of mast cells and pro‐inflammatory and anti‐inflammatory cytokines. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;844:87‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rogers JP, Watson CJ, Badenoch J, et al. Neurology and neuropsychiatry of COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the early literature reveals frequent CNS manifestations and key emerging narratives. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92:932‐941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grisold W, Moro E, Teresa Ferretti M, et al. Gender issues during the times of COVID‐19 pandemic. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:e73‐e77. 10.1111/ene.14815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Tab S1‐S3

Appendix S4

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published text and supplementary material. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.